Validation of Inertial Sensor-Based Step Detection Algorithms for Edge Device Deployment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

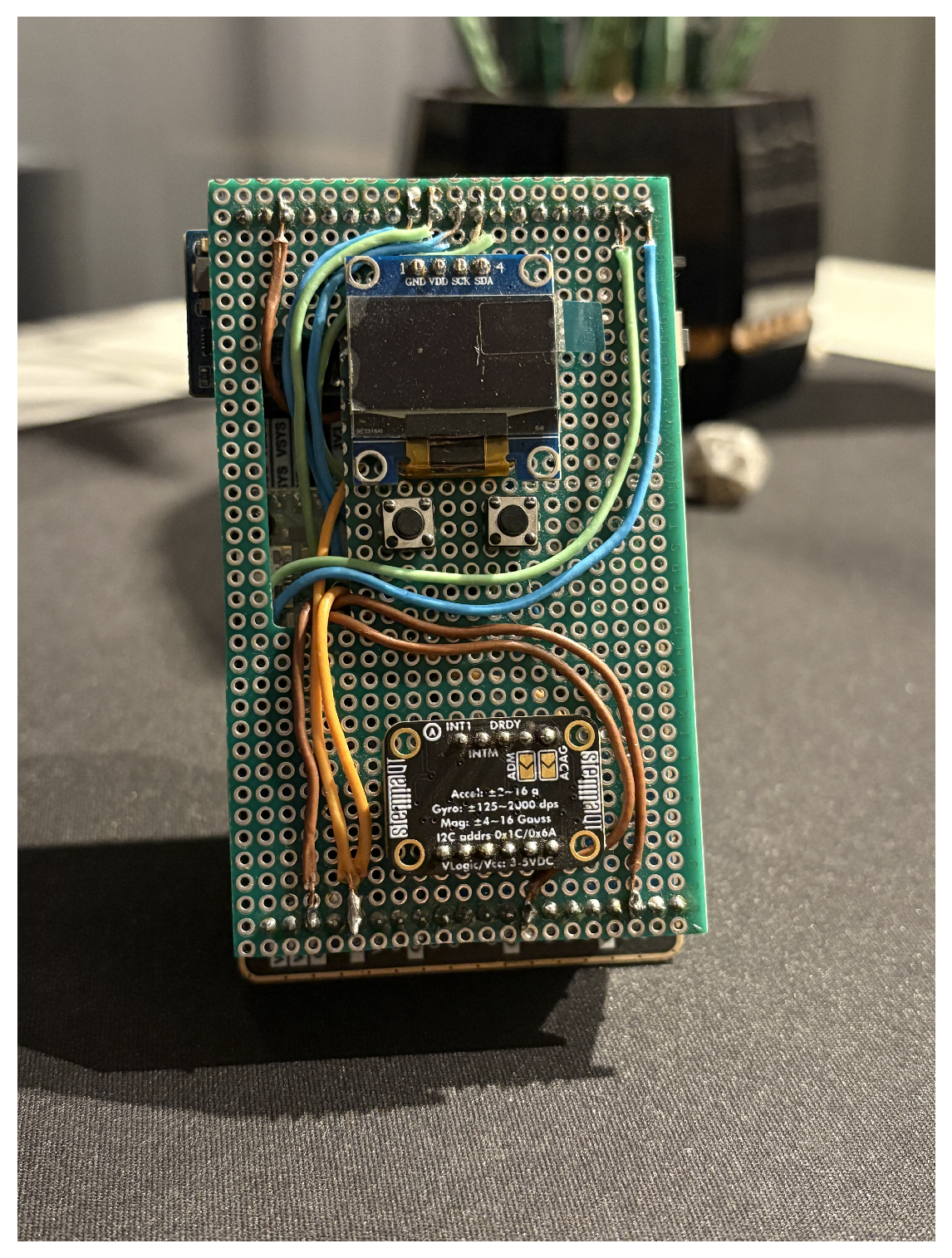

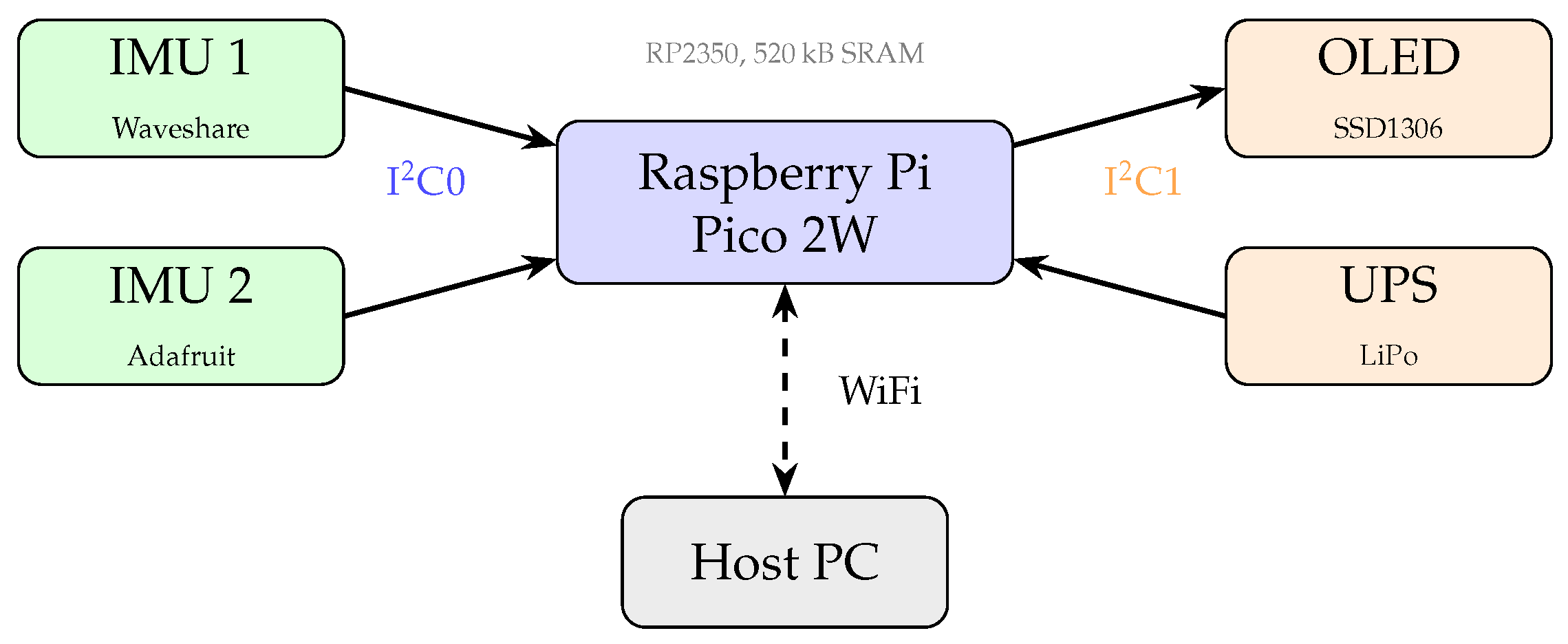

2.1. Hardware Platform

- Waveshare Pico-10DOF-IMU incorporating the InvenSense MPU-9250 nine-axis motion tracking device. This sensor provides a 3-axis accelerometer with a selectable full-scale range up to ±16 g, a 3-axis gyroscope with range up to ±2000°/s, and a 3-axis magnetometer.

- Adafruit ST 9-DoF Combo featuring the STMicroelectronics LSM6DSOX inertial module (accelerometer ±16 g, gyroscope ±2000°/s) combined with the LIS3MDL magnetometer. The LSM6DSOX includes an embedded machine learning core, though this feature was not utilized to ensure fair comparison.

2.2. Implemented Algorithms

2.2.1. Peak Detection

2.2.2. Zero-Crossing

2.2.3. Spectral Analysis

2.2.4. Adaptive Threshold

2.2.5. SHOE (Step Heading Offset Estimator)

2.2.6. Algorithm Parameters

2.3. Signal Preprocessing

- Acceleration magnitude computation: The three-axis acceleration vector is converted to a scalar magnitude (Euclidean norm), providing orientation-independent measurement.

- Gravity compensation: The median acceleration value is subtracted from the signal to isolate dynamic acceleration components. The median is preferred over the mean, as it is more robust to transient high-amplitude events.

- Low-pass filtering: A Savitzky–Golay filter removes high-frequency noise while preserving the temporal characteristics of gait events. This filter was chosen over conventional low-pass filters due to its superior preservation of peak amplitudes and locations.

2.4. Experimental Protocol

2.4.1. Test Scenarios

- Timed Up and Go (TUG): A standardized clinical test involving rising from a chair, walking 3 m, turning around a marker, and returning to a seated position. This test incorporates multiple activity transitions (sitting–standing–walking–turning–walking–sitting) and is widely used for assessing mobility in elderly and neurological populations [4]. Each trial lasted approximately 10–15 s.

- Natural walking: Level walking at self-selected comfortable pace (approximately ) along a 10 m corridor with turns at each end, repeated for 60 s. This represents the most common daily activity and serves as a baseline performance reference.

- Fast walking: Increased pace (approximately ), testing algorithm performance at higher cadences. This scenario evaluates whether algorithms can adapt to shorter inter-step intervals.

- Jogging: Light running (approximately ) with fundamentally different gait dynamics characterized by the absence of the double support phase and increased vertical acceleration amplitudes. This scenario tests algorithm robustness to gait pattern changes.

- Stairs ascending: Climbing 28 wooden steps (rise: 18 cm, tread: 25 cm) at a natural pace. Stair climbing produces distinct acceleration patterns with asymmetric profiles compared to level walking.

- Stairs descending: Descending 28 steps with typically higher impact amplitudes due to gravitational assistance. This scenario is particularly relevant for fall risk assessment applications.

- Stairs combined: Sequential ascending and descending with direction change at the bottom, testing algorithm behavior during transitions between climbing modes.

2.4.2. Sensor Mounting Locations

- Front trouser pocket (thigh): Representing smartphone placement, the most convenient but potentially variable location due to loose coupling with body movement.

- Ankle of dominant leg: Traditional location for research-grade gait analysis providing direct measurement of the leg movement.

- Wrist of dominant hand: Standard smartwatch location, subject to arm swing artifacts unrelated to stepping.

- Upper arm: Alternative wearable location potentially offering more stable signals than wrist due to reduced degrees of freedom.

2.4.3. Data Collection

2.5. Validation with FRAILPOL Repository

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

- Precision (P): —proportion of detected steps that were correct, penalizing false positives.

- Recall (R): —proportion of actual steps that were detected, penalizing missed steps.

- F1-score: —harmonic mean, providing balanced assessment of precision and recall.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Algorithm Performance

3.2. Impact of Test Scenario

3.3. Impact of Sensor Mounting Location

3.4. Detailed Scenario–Location Analysis

3.5. Sensor Comparison

3.6. Preliminary Application to Clinical TUG Data

3.6.1. Algorithm-Specific Failure Modes

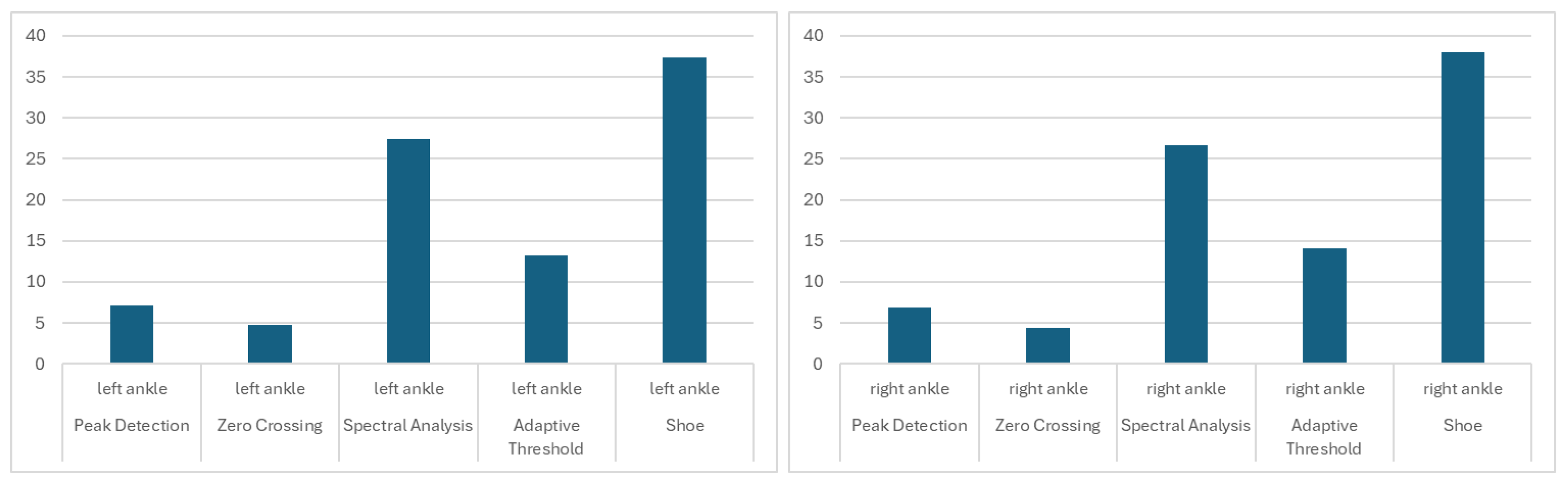

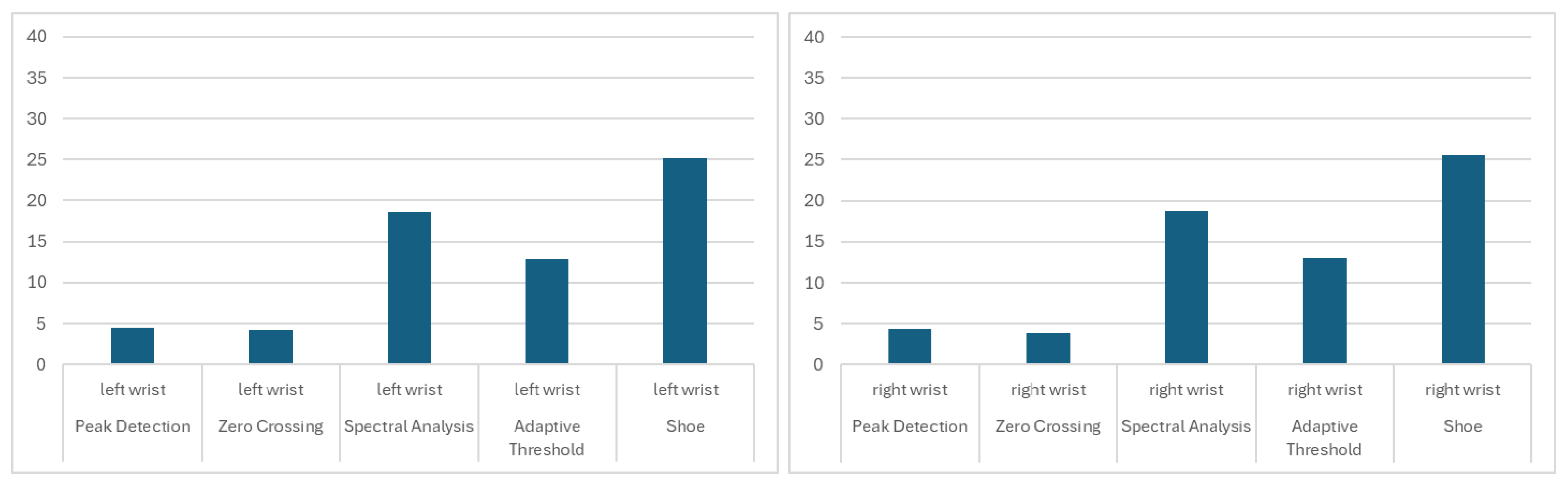

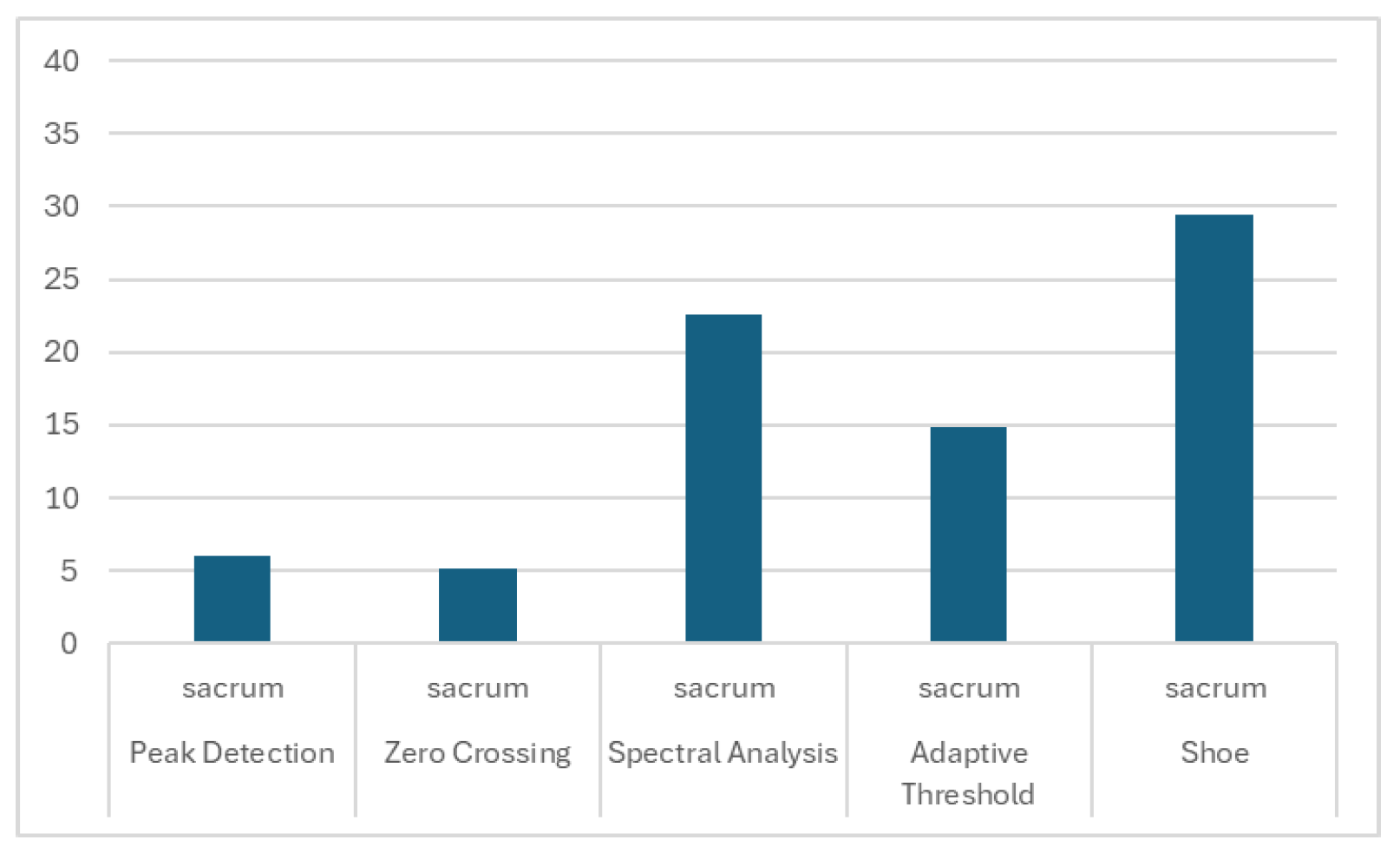

3.6.2. Bilateral Sensor Consistency

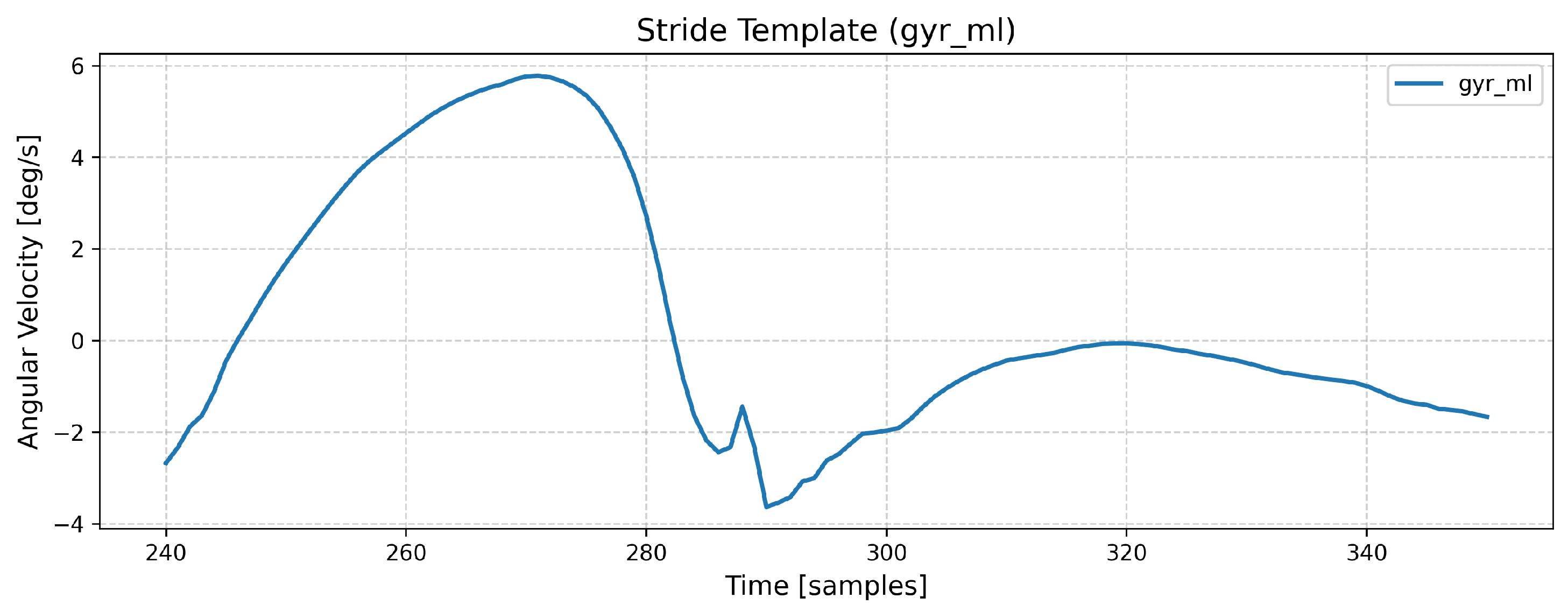

3.6.3. Comparison to Step Detection Utilizing Event Detection Based on Stride Segmentation

3.6.4. Implications for Clinical Deployment

- Strong recommendation: Zero-Crossing, which obtains results that are acceptable and close to those based on an advanced step analysis method requiring specific assembly and accurate calibration of coordinate systems.

- Recommended: Peak Detection and Adaptive Threshold algorithms, which do not assume continuous walking.

- Not recommended: SHOE (designed for foot-mounted navigation sensors) and Spectral Analysis (assumes stationary gait frequency) without additional activity segmentation preprocessing.

4. Discussion

4.1. Algorithm Selection Guidelines

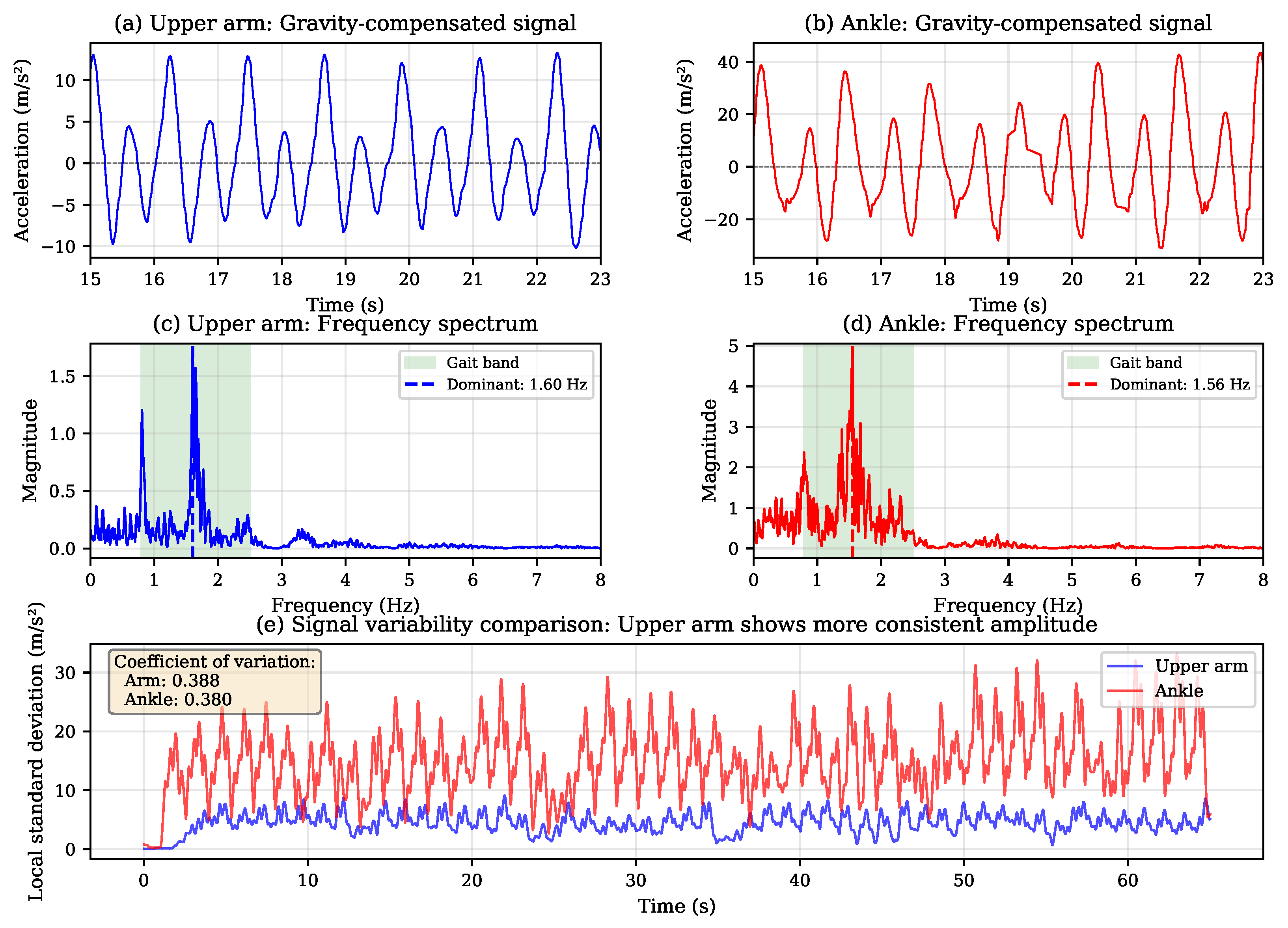

4.2. Mounting Location Considerations

- Signal regularity: The arm exhibits pendulum-like motion during walking with consistent frequency matching the step cadence. Unlike the leg, which experiences complex acceleration patterns during stance and swing phases, arm motion approximates a simple harmonic oscillator.

- Reduced impact artifacts: Ankle sensors experience high-amplitude impacts at heel strike that can saturate sensors or introduce ringing artifacts. The arm, being mechanically isolated from ground contact, produces cleaner signals.

- Bilateral coupling: Both arms move in coordinated opposition with the legs, effectively averaging left and right step signals rather than detecting only one leg’s motion.

4.3. Clinical Test Challenges

- Sit-to-stand transitions: Large vertical accelerations during rising mimic step signatures.

- Turning: Rotational motion produces complex acceleration patterns unlike straight walking.

- Variable cadence: Initial acceleration and final deceleration phases produce irregular step timing.

4.4. Implications for Edge Computing

Empirical Validation on Raspberry Pi Pico 2W

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

- Single participant: All controlled experiments involved one healthy adult, limiting generalization to diverse populations (varying height, weight, age, gait pathologies). Gait dynamics vary substantially across demographic groups—elderly individuals typically exhibit reduced stride length and cadence, while pathological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease produce a characteristic shuffling gait with reduced arm swing amplitude. The algorithms validated here may require parameter re-tuning for such populations. However, the complementary analysis of 668 clinical TUG recordings from the FRAILPOL repository (Section 3.6) partially addresses this limitation by demonstrating algorithm behavior across diverse clinical populations, including elderly patients with varying mobility impairments. The finding that event-based algorithms (Peak Detection, Zero-Crossing) maintained 86–94% plausible detection rates on clinical data suggests reasonable generalization potential, though definitive validation with ground truth annotations remains necessary. Future studies should include broader participant cohorts with stratification by demographic and clinical characteristics.

- Controlled environment: Testing occurred in a home environment on level floors and standard stairs. Real-world conditions (uneven terrain, crowds, variable surfaces, outdoor environments) may introduce additional challenges.

- Manual annotation: Ground truth establishment incurred human reaction delays (≈100–200 ms). While the ±0.3 s tolerance window mitigated timing errors, systematic bias in annotation may affect absolute metrics. Video-based annotation or force plate validation would provide a more accurate reference.

- Fixed parameters: Universal algorithm parameters were prioritized over scenario-specific optimization. Adaptive parameter tuning or machine learning-based approaches may achieve higher accuracy at the cost of increased complexity.

- Clinical data without ground truth: The TUG dataset analysis was limited to plausibility assessment due to the absence of reference step counts. Future clinical validation should incorporate video-based annotation or instrumented walkways for definitive accuracy evaluation.

5. Conclusions

- Peak Detection provides robust general-purpose performance (F1 = 0.82 ± 0.12), with computational efficiency suitable for edge devices (2–3 ms execution time). Its adaptive threshold mechanism enables deployment without manual calibration, similar to commercial implementations in the Bosch BMA421 accelerometer.

- Spectral Analysis excels for stair navigation (F1 = 0.86–0.92), making it particularly valuable for home-based activity monitoring of elderly populations, where stair climbing indicates functional capacity. The 8 s analysis window requires approximately 10 kB RAM, feasible on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2W (520 kB SRAM available).

- Upper arm mounting unexpectedly outperformed ankle placement (F1 = 0.84 ± 0.04 vs. 0.80 ± 0.07), suggesting reconsideration of optimal sensor locations for wearable device design. The regular, pendulum-like arm motion during walking may produce more algorithm-friendly signals than complex leg dynamics.

- Clinical transition scenarios (TUG) remain challenging (mean F1 = 0.68 ± 0.10), indicating the need for algorithms capable of handling activity transitions. This limitation has direct implications for clinical mobility assessment applications.

- Algorithm–location matching matters: Zero-Crossing performed best at the wrist (F1 = 0.84 ± 0.06) despite an overall lower ranking, suggesting that customized algorithm selection based on device form factor can substantially improve accuracy.

- Edge deployment is feasible: Memory requirements (1.5–10 kB, depending on the algorithm) and execution times (<5 ms) are compatible with commercial embedded implementations using 2–4 s analysis windows at 50–100 Hz sampling rates.

- Clinical generalization requires algorithm awareness: Application to 668 clinical TUG recordings revealed that algorithms assuming a continuous gait (Spectral Analysis, SHOE) fails dramatically on variable-activity data, while event-based methods (Zero-Crossing, Peak Detection) maintain 86–94% plausible detection rates, even without ground truth validation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| HAR | Human Activity Recognition |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go |

| PDR | Pedestrian Dead Reckoning |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SHOE | Step Heading Offset Estimator |

| ZUPT | Zero Velocity Update |

| HS | Heel Strike |

| TO | Toe-Off |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

References

- Godfrey, A.; Del Din, S.; Barry, G.; Mathers, J.C.; Rochester, L. Instrumenting Gait with an Accelerometer: A System and Algorithm Examination. Med. Eng. Phys. 2015, 37, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W.; Han, Y. SmartPDR: Smartphone-Based Pedestrian Dead Reckoning for Indoor Localization. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 2906–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, M.W. Gait Analysis: An Introduction, 5th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.H.; Elshehabi, M.; Haertner, L.; Del Din, S.; Srulijes, K.; Heger, T.; Synofzik, M.; Hobert, M.A.; Faber, G.S.; Hansen, C.; et al. Validation of a Step Detection Algorithm during Straight Walking and Turning in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Older Adults Using an Inertial Measurement Unit at the Lower Back. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feehan, L.M.; Geldman, J.; Sayre, E.C.; Park, C.; Ezzat, A.M.; Yoo, J.Y.; Hamilton, C.B.; Li, L.C. Accuracy of Fitbit Devices: Systematic Review and Narrative Syntheses of Quantitative Data. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Dhall, A.; Liebig, A.; Stacey, B.; Shaban, H.; McDuff, D.; Yang, X.; Liu, X. Accuracy of Step Count from Wearable Devices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermeeren, S.; Steendam, H. Deep-Learning-Based Step Detection and Step Length Estimation With a Handheld IMU. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 24205–24221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijnders, R.; Warmerdam, E.; Hansen, C.; Schmidt, G.; Maetzler, W. A Deep Learning Approach for Gait Event Detection from a Single Shank-Worn IMU: Validation in Healthy and Neurological Cohorts. Sensors 2022, 22, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, R.C.; Lanningham-Foster, L.M.; Manohar, C.; McCrady, S.K.; Nysse, L.J.; Kaufman, K.R.; Padilla, D.J.; Levine, J.A. Precision and Accuracy of an Ankle-Worn Accelerometer-Based Pedometer in Step Counting and Energy Expenditure. Prev. Med. 2005, 41, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straczkiewicz, M.; Huang, E.J.; Onnela, J.P. A “One-Size-Fits-Most” Walking Recognition Method for Smartphones, Smartwatches, and Wearable Accelerometers. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warden, P.; Situnayake, D. TinyML: Machine Learning with TensorFlow Lite on Arduino and Ultra-Low-Power Microcontrollers; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Küderle, A.; Ullrich, M.; Roth, N.; Ollenschläger, M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Moradi, H.; Richer, R.; Seifer, A.K.; Zürl, M.; Sîmpetru, R.C.; et al. Gaitmap—An Open Ecosystem for IMU-Based Human Gait Analysis and Algorithm Benchmarking. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2024, 5, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczęsna, A.; Błaszczyszyn, M.; Amjad, A. Database for Prevalence and Determinants of Frailty and Pre-Frailty in Elderly People with Quantifying Functional Mobility; Figshare: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspberry Pi Ltd. Pico 2W Datasheet: A Microcontroller by Raspberry Pi. Datasheet, 2024. Available online: https://pip.raspberrypi.com/documents/RP-008304-DS-1-pico-2-w-datasheet.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Oudre, L.; Barrois-Müller, R.; Moreau, T.; Truong, C.; Vienne-Jumeau, A.; Ricard, D.; Vayatis, N.; Vidal, P.P. Template-Based Step Detection with Inertial Measurement Units. Sensors 2018, 18, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferri, C.P.; Jacob, K. Dementia in low-income and middle-income countries: Different realities mandate tailored solutions. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiakiri, A.; Plakias, S.; Giarmatzis, G.; Tsakni, G.; Christidi, F.; Karakitsiou, G.; Georgousopoulou, V.; Manomenidis, G.; Tsiptsios, D.; Vadikolias, K.; et al. Wearable Sensor Technologies and Gait Analysis for Early Detection of Dementia: Trends and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 7669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amjad, A.; Qaiser, S.; Błaszczyszyn, M.; Szczęsna, A. The evolution of frailty assessment using inertial measurement sensor-based gait parameter measurements: A detailed analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 14, e1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Analog Devices. Pedometer Design—3-Axis Digital Accelerometer, AN-1057 Application Note. Application Note AN-1057, 2018. Available online: https://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/application-notes/AN-1057.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Cui, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Smartphone-Based Unconstrained Step Detection Fusing a Variable Sliding Window and an Adaptive Threshold. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Song, Q.; Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z. An Adaptive Zero Velocity Detection Algorithm Based on Multi-Sensor Fusion for a Pedestrian Navigation System. Sensors 2018, 18, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Park, C.G. A Zero-Velocity Detection Algorithm Robust to Various Gait Types for Pedestrian Inertial Navigation. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 22, 4916–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, J.; Oberndorfer, C.; Kugler, P.; Schuldhaus, D.; Winkler, J.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B. Subsequence dynamic time warping as a method for robust step segmentation using gyroscope signals of daily life activities. In Proceedings of the 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Osaka, Japan, 3–7 July 2013; pp. 6744–6747. [Google Scholar]

- Rampp, A.; Barth, J.; Schülein, S.; Gaßmann, K.G.; Klucken, J.; Eskofier, B.M. Inertial sensor-based stride parameter calculation from gait sequences in geriatric patients. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 62, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, J.; Felix, P.; Costa, L.; Moreno, J.C.; Santos, C.P. Gait event detection in controlled and real-life situations: Repeated measures from healthy subjects. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondin, A.; Nordström, M.; Olsson, C.M.; Salvi, D. Open Source Step Counter Algorithm for Wearable Devices. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Internet of Things (IoT ’20 Companion), Malmö, Sweden, 6–9 October 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch Sensortec. BMA421 Intelligent, Triaxial Acceleration Sensor—Datasheet. Datasheet BST-BMA421-FL000, 2020. Available online: https://files.pine64.org/doc/datasheet/pinetime/BST-BMA421-FL000.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Analog Devices. Step Counting Using the ADXL367, AN-2554 Application Note. Application Note AN-2554, 2023. Available online: https://www.analog.com/en/resources/app-notes/an-2554.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

| Algorithm | Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Detection | Window size | 0.6 s | Smoothing window for Savitzky–Golay filter |

| Threshold | 0.5 | Adaptive threshold multiplier (×rolling SD) | |

| Min. step interval | 0.35 s | Minimum time between detected steps | |

| Zero-Crossing | Window size | 0.5 s | Signal smoothing window |

| Min. step interval | 0.4 s | Refractory period after detection | |

| Hysteresis band | 0.3 m/s2 | Threshold band to prevent oscillation | |

| Spectral Analysis | Window size | 8.0 s | STFT analysis window length |

| Overlap | 0.8 | Window overlap ratio (80%) | |

| Freq. range | [0.8, 2.0] Hz | Valid gait frequency band | |

| Adaptive Threshold | Window size | 0.8 s | Local amplitude calculation window |

| Sensitivity | 0.5 | Threshold sensitivity (× mean amplitude) | |

| Min. step interval | 0.4 s | Minimum inter-step timing | |

| SHOE | Window size | 0.3 s | Stance phase detection window |

| Threshold | 9.0 | Combined signal threshold | |

| Min. step interval | 0.35 s | Minimum step spacing |

| Metric | Peak Det. | Zero Cross. | Spectral | Adaptive | SHOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean F1-score | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.75 |

| Standard deviation | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Range (min–max) | 0.51–0.98 | 0.33–0.96 | 0.61–0.97 | 0.50–0.95 | 0.50–0.93 |

| Execution time (ms) | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 4.2 |

| Scenario | Peak Det. | Zero Cross. | Spectral | Adaptive | SHOE | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUG | 0.79 ± 0.13 | 0.56 ± 0.17 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.15 | 0.64 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.10 |

| Natural walking | 0.81 ± 0.15 | 0.77 ± 0.18 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.04 |

| Fast walking | 0.87 ± 0.12 | 0.89 ± 0.10 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 0.82 ± 0.11 | 0.86 ± 0.05 | 0.87 ± 0.03 |

| Jogging | 0.84 ± 0.11 | 0.84 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.12 | 0.75 ± 0.08 |

| Stairs ascending | 0.76 ± 0.16 | 0.79 ± 0.11 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.19 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.78 ± 0.07 |

| Stairs descending | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.04 |

| Stairs combined | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.04 |

| Location | Peak Det. | Zero Cross. | Spectral | Adaptive | SHOE | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankle | 0.87 ± 0.10 | 0.71 ± 0.19 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 0.87 ± 0.10 | 0.76 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.07 |

| Upper arm | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 0.82 ± 0.16 | 0.89 ± 0.10 | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.04 |

| Wrist | 0.67 ± 0.13 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 0.74 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.09 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.73 ± 0.08 |

| Thigh pocket | 0.89 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 0.82 ± 0.12 | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 0.81 ± 0.06 |

| Location | Scenario | Peak Det. | Zero Cross. | Spectral | Adaptive | SHOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thigh | TUG | 0.84 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.68 |

| Thigh | Natural walking | 0.91 | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.78 |

| Thigh | Fast walking | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| Thigh | Jogging | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.54 |

| Thigh | Stairs ascending | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.67 |

| Thigh | Stairs descending | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.78 |

| Thigh | Stairs combined | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Wrist | TUG | 0.61 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| Wrist | Natural walking | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.79 |

| Wrist | Fast walking | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.93 |

| Wrist | Jogging | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| Wrist | Stairs ascending | 0.51 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.50 | 0.69 |

| Wrist | Stairs descending | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.59 | 0.71 |

| Wrist | Stairs combined | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.86 |

| Upper arm | TUG | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.79 | 0.65 |

| Upper arm | Natural walking | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| Upper arm | Fast walking | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| Upper arm | Jogging | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| Upper arm | Stairs ascending | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.78 |

| Upper arm | Stairs descending | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.76 |

| Upper arm | Stairs combined | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| Ankle | TUG | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.72 |

| Ankle | Natural walking | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.80 |

| Ankle | Fast walking | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.79 |

| Ankle | Jogging | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.66 |

| Ankle | Stairs ascending | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.75 |

| Ankle | Stairs descending | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.81 |

| Ankle | Stairs combined | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.76 |

| Algorithm | Median | P10 | P90 | P99 | % Plausible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Crossing | 11 | 6 | 17 | 26 | 93.7 |

| Adaptive Threshold | 13 | 8 | 21 | 182 | 88.8 |

| Peak Detection | 13 | 7 | 21 | 41 | 86.5 |

| Spectral Analysis | 18 | 10 | 51 | 177 | 60.5 |

| SHOE | 12 | 1 | 56 | 246 | 41.5 |

| Algorithm | Buffer Size | RAM Est. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Detection | 0.6 s (60 samples) | ∼2 kB | Streaming capable, minimal buffering |

| Zero-Crossing | 0.5 s (50 samples) | ∼1.5 kB | Streaming capable, hysteresis state only |

| Spectral Analysis | 8.0 s (800 samples) | ∼10 kB | Requires FFT buffer + Hanning window |

| Adaptive Threshold | 0.8 s (80 samples) | ∼3 kB | Local amplitude history required |

| SHOE | 0.3 s (30 samples) | ∼2 kB | Dual-sensor (accel + gyro) buffers |

| Algorithm | Upper Arm | Ankle | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1-Score | Time (ms) | F1-Score | Time (ms) | |

| Peak Detection | 0.818 | 535 | 0.632 | 436 |

| Zero-Crossing | 0.800 | 450 | 0.667 | 393 |

| Spectral Analysis | 0.788 | 22 | 0.788 | 17 |

| Adaptive Threshold | 1.000 | 638 | 0.769 | 497 |

| SHOE | 0.571 | 644 | 0.880 | 557 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kisiel, M.; Amjad, A.; Szczęsna, A. Validation of Inertial Sensor-Based Step Detection Algorithms for Edge Device Deployment. Sensors 2026, 26, 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030876

Kisiel M, Amjad A, Szczęsna A. Validation of Inertial Sensor-Based Step Detection Algorithms for Edge Device Deployment. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):876. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030876

Chicago/Turabian StyleKisiel, Maksymilian, Arslan Amjad, and Agnieszka Szczęsna. 2026. "Validation of Inertial Sensor-Based Step Detection Algorithms for Edge Device Deployment" Sensors 26, no. 3: 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030876

APA StyleKisiel, M., Amjad, A., & Szczęsna, A. (2026). Validation of Inertial Sensor-Based Step Detection Algorithms for Edge Device Deployment. Sensors, 26(3), 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030876