Simultaneous Down-Regulation of Intracellular hTERT and GPX4 mRNA Using MnO2-Nanosheet Probes to Induce Cancer Cell Death

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of MnO2-NSs

2.3. Preparation of MnO2-NS-Based Probes

2.4. Determination of Fluorescence Quenching and Recovery

2.5. Cell Culture

2.6. In Situ Imaging of MnO2-NS Probes in A549, HeLa, HepG2, and Caco-2 Cells

2.7. Cell Viability Assay

2.8. qRT-PCR Analysis of hTERT mRNA and GPX4 mRNA Expression

2.9. Quantification of Intracellular hTERT, GPX4, and Se-GPX Activity

2.10. Analysis of Intracellular GSH Levels

2.11. Analysis of Intracellular ROS Levels

2.12. Measurements of Intracellular LPO Levels

2.13. Statistical Analysis

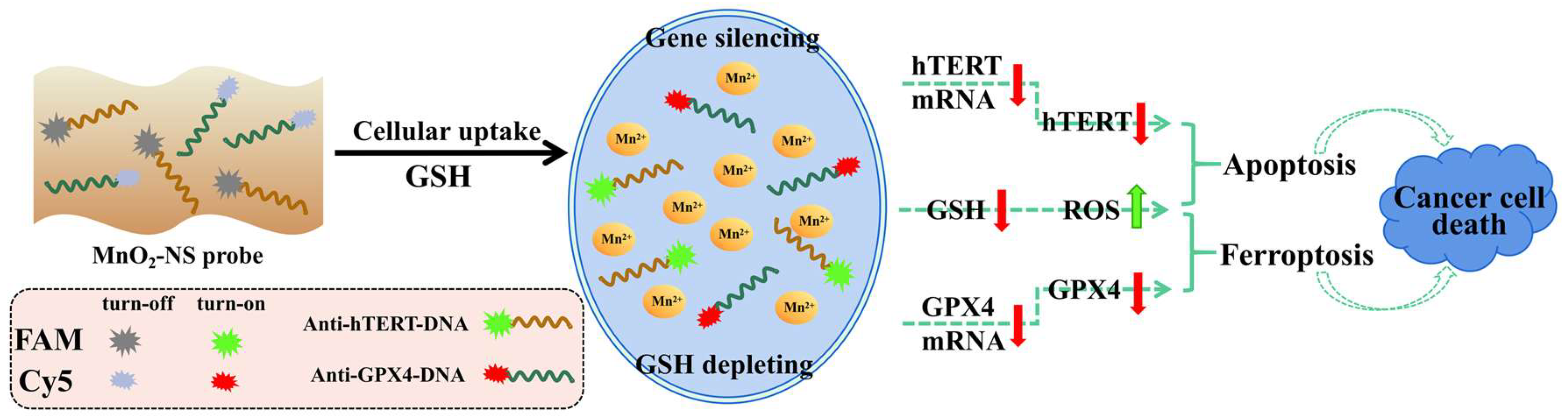

3. Results and Discussion

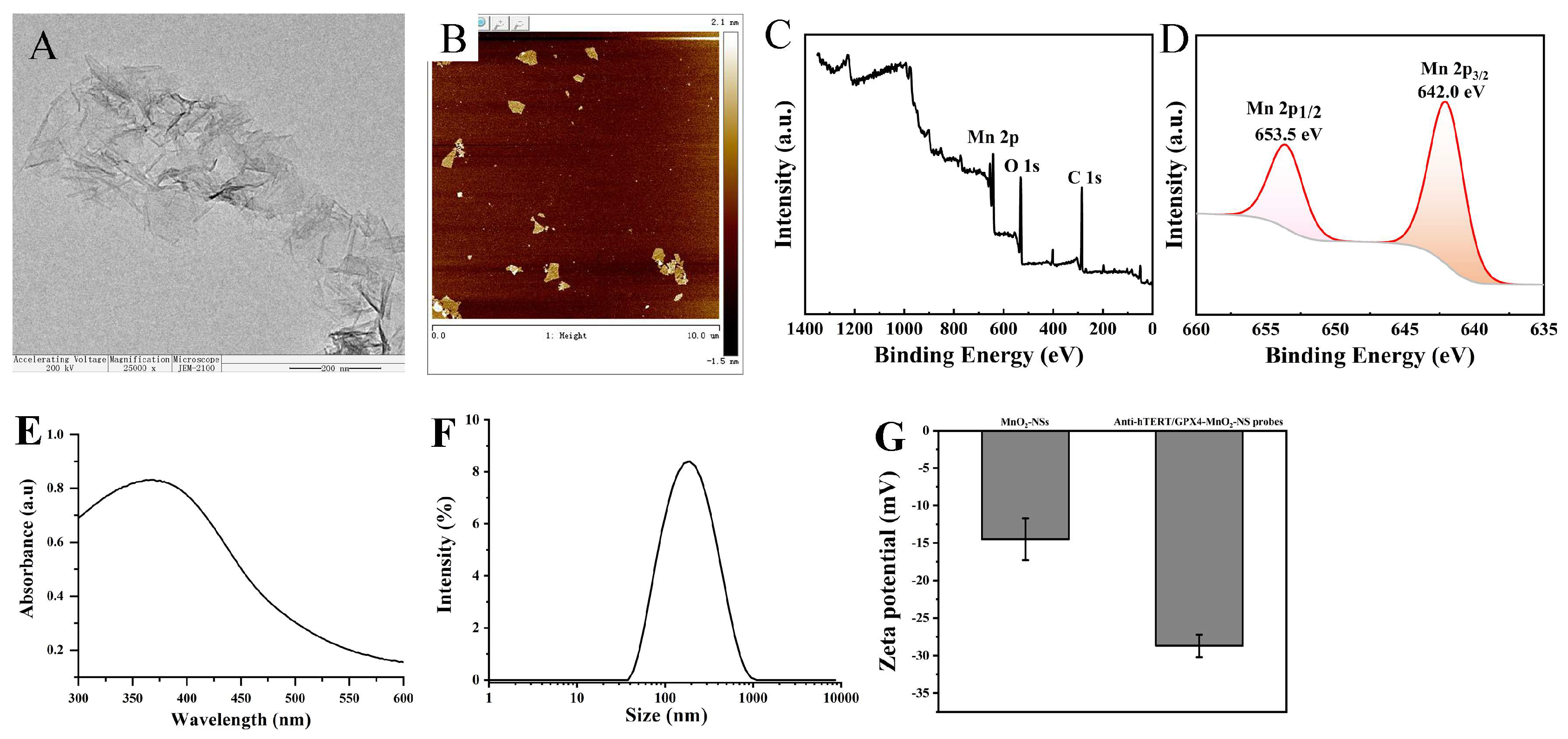

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of MnO2-NSs and Anti-hTERT/GPX4-DNA-MnO2-NS Probes

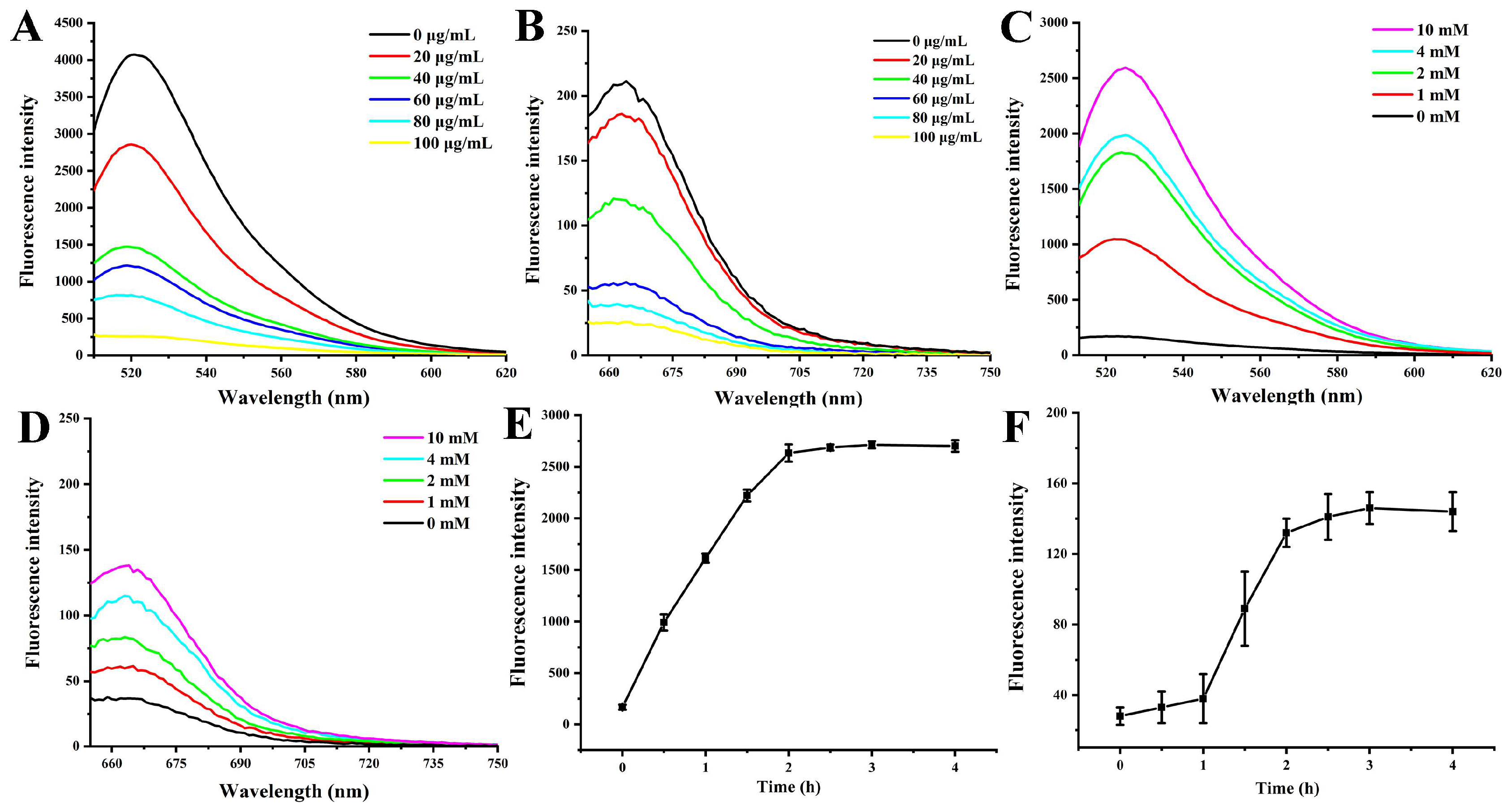

3.2. Fluorescence Quenching and Recovery

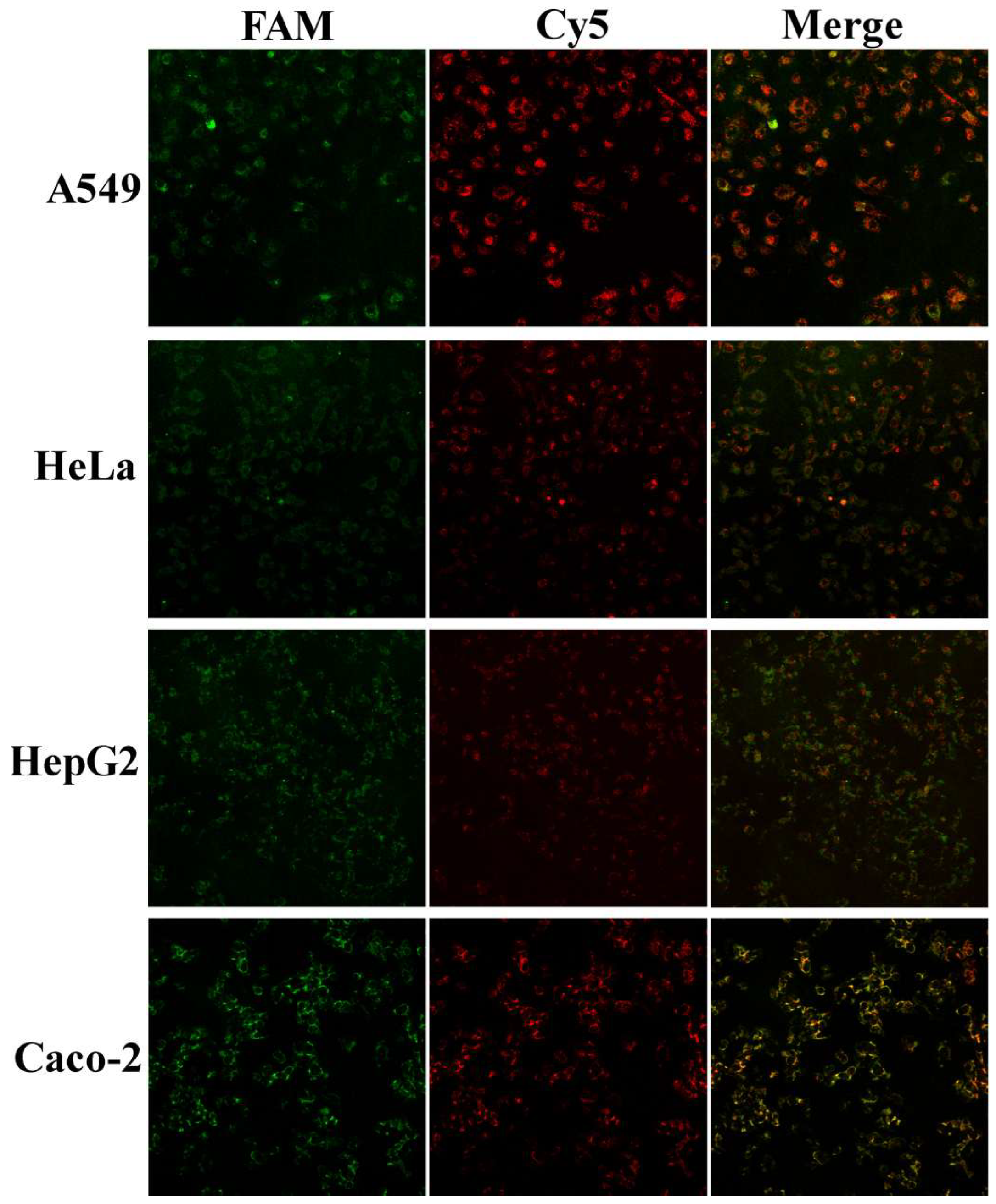

3.3. In Situ Imaging of Cell Uptake of Anti-hTERT/GPX4-MnO2-NS Probes

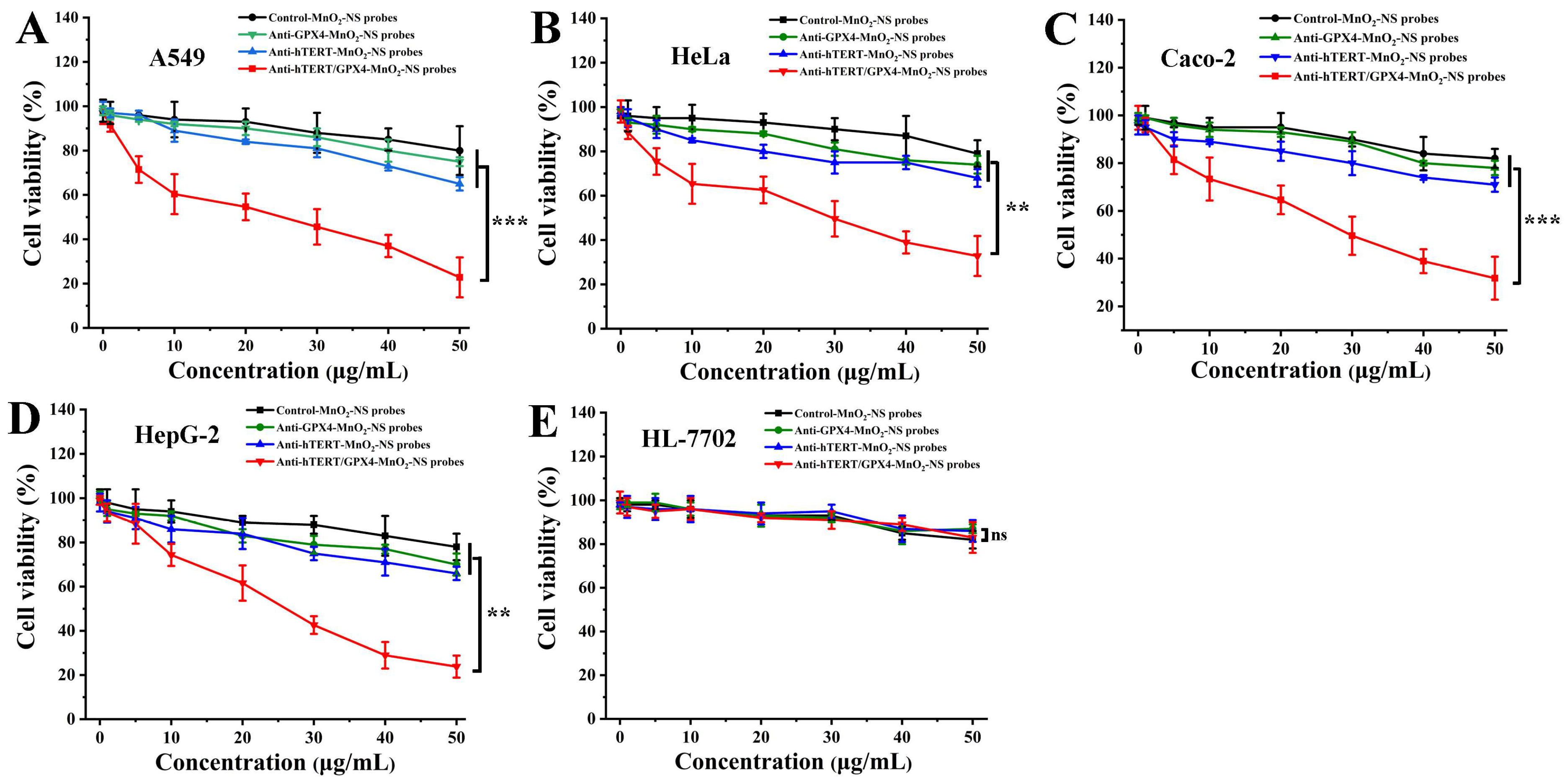

3.4. In Vitro Anticancer Assay

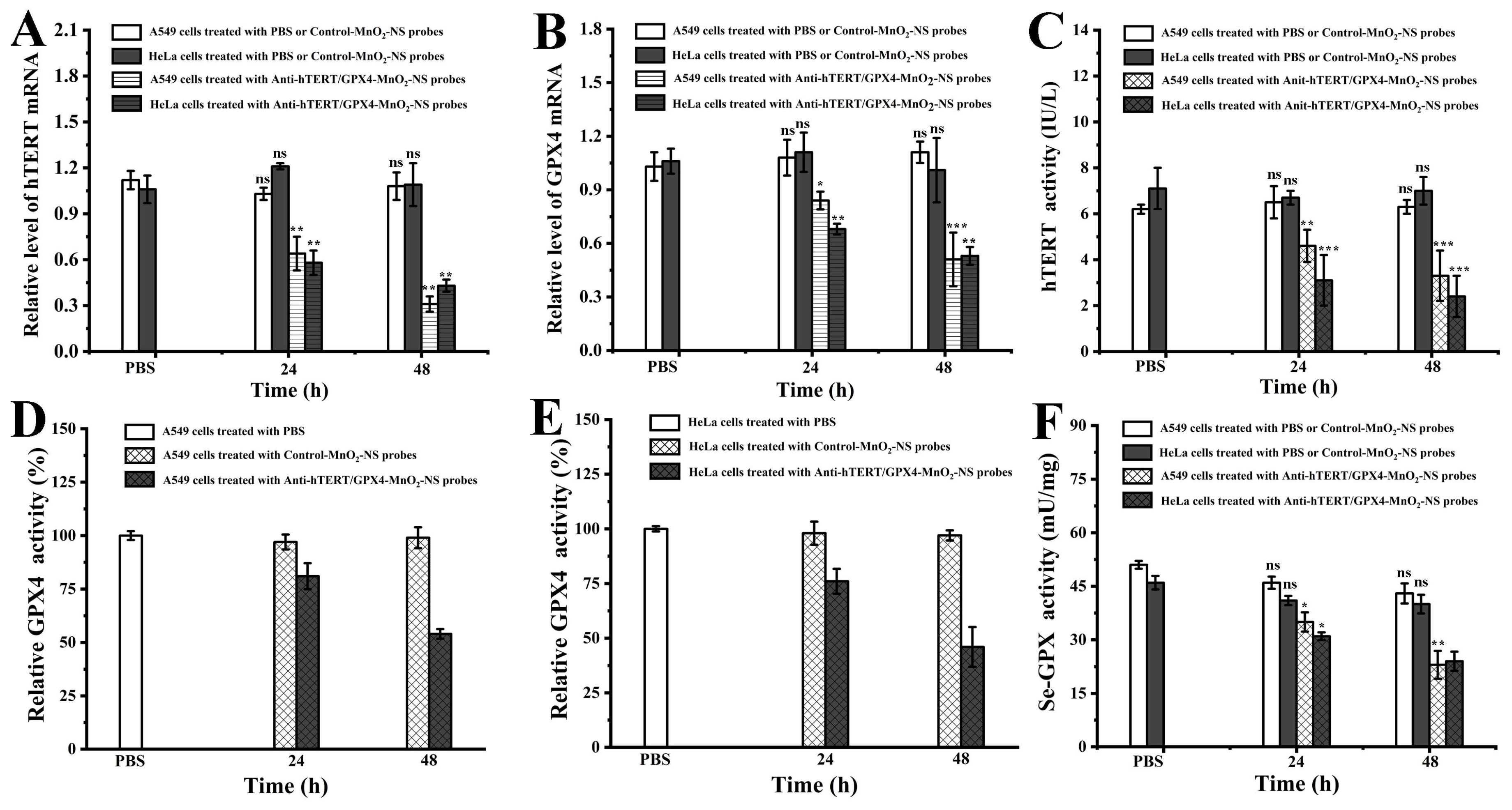

3.5. Analysis of Relative mRNA Levels and Protein Expression of hTERT and GPX4 in Cells

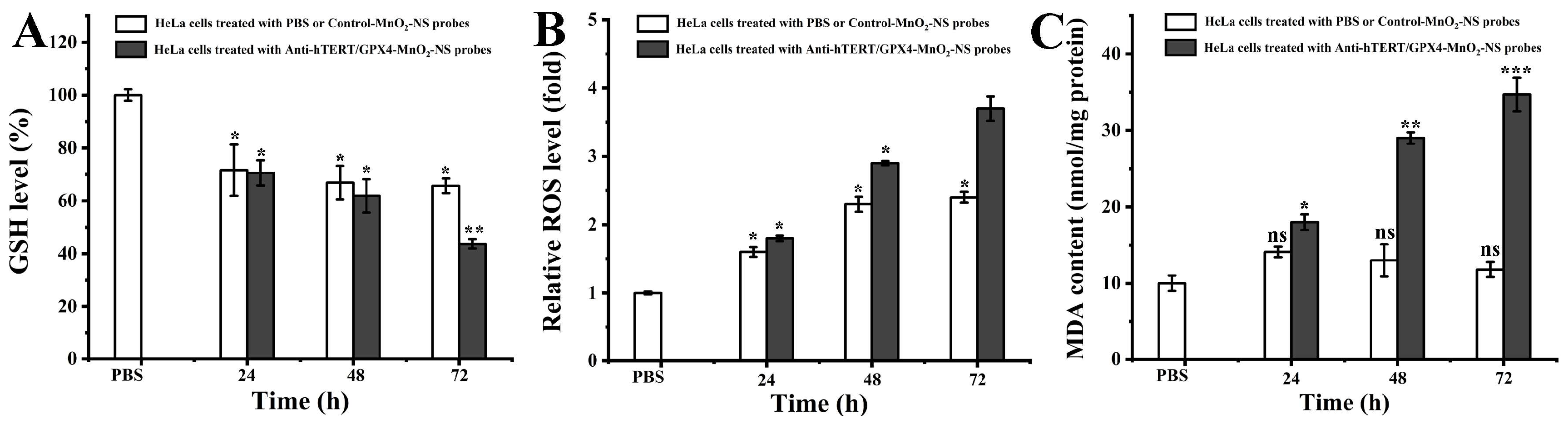

3.6. Analysis of Intracellular GSH Level, ROS Level, and MDA Content

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Ni, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y. Combinational Gene Therapy toward Cancer with Nanoplatform: Strategies and Principles. ACS Mater. Au 2023, 3, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, W.; Zeng, Y.; Zheng, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chan, K.; She, M.; Lu, Y.; Cao, C.; Wong, W. Targeting hTERT Promoter G-Quadruplex DNA Structures with Small-Molecule Ligand to Downregulate hTERT Expression for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 13363–13382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Wu, F.; Dai, J.; Xia, F.; Lou, X. Targeting Proteins in Nucleus through Dual-Regulatory Pathways Acting in Cytoplasm. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 5811–5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhan, C.; Xie, X.; Yao, Z.; Wu, C.; Ping, Y.; Shen, J. Combination Therapy to Overcome Ferroptosis Resistance by Biomimetic Self-assembly Nano-prodrug. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xie, A.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, X. A Potent and Selective Anti-glutathione Peroxidase 4 Nanobody as a Ferroptosis Inducer. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 19420–19431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, J.; Deng, K.; Zhou, W.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Wu, M.; Huang, S. GPX4 Inhibition Synergistically Boosts Mitochondria Targeting Nanoartemisinin-induced Apoptosis/Ferroptosis Combination Cancer Therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 5831–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, S.; Xie, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Gong, M.; Zhang, D. Activatable Plasmonic Versatile Nanoplatform for Glutathione-Depletion Augmented Ferroptosis and NIR-II Photothermal Synergistic Therapy. ACS Mater. Lett. 2024, 6, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Hong, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Yue, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Li, C. Visualizing the Down-regulation of hTERT mRNA Expression Using Gold-nanoflare Probes and Verifying the Correlation with Cancer Cell Apoptosis. Analyst 2019, 144, 2994–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Sui, Y.; Yue, Q.; Yan, S.; Li, C.; Hong, M. Monitoring and Regulating Intracellular GPX4 mRNA Using Gold Nanoflare Probes and Enhancing Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Dong, C.; Shi, S. An Overview of Recent Advancements on Manganese-Based Nanostructures and Their Application for ROS-Mediated Tumor Therapy. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 2415–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Yang, K.; Li, J.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, R. Self-Propelled Asymmetrical Nanomotor for Self-Reported Gas Therapy. Small 2021, 17, 2102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.; Yue, J.; Zheng, P.; Ma, P.; Lin, J. Manganese Oxide Nanomaterials Boost Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 7117–7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cheng, G.; Chen, N.; Ding, Z.; Dai, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X. MnO2-Mediated cGAS-STING Signaling and Photothermal Effect Amplify Chemodynamic Therapy Induced by Fe-Based Nanoparticle in Tumor Therapy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 2986–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Yang, Q.; Song, Q.; Hong, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Cheng, S. Multi-pathway Inducing Ferroptosis by MnO2-based Nanodrugs for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 6486–6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, C.; Lin, Q.; Gao, X.; Cao, T.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, C. Intracellular miRNA Imaging Based on a Self-Powered and Self-Feedback Entropy-Driven Catalyst–DNAzyme Circuit. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 39866–39872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Kageyama, H.; Saito, G.; Ishigaki, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Kawamata, J. Room-temperature synthesis of manganese oxide monosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 15938–15943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Yuan, R.; Xiang, Y. Biodegradable MnO2 Nanosheet-Mediated Signal Amplification in Living Cells Enables Sensitive Detection of Down-Regulated Intracellular MicroRNA. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 5717–5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Hayat, U.; Rasheed, T.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Redox-responsive Nanocarriers as Tumor-targeted Drug Delivery Systems. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 157, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.K.; Rao, M.J.; Putta, C.L.; Ray, S.; Rengan, A.K. Telomerase: A Nexus Between Cancer Nanotherapy and Circadian Rhythm. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 2259–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yao, X.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Li, M.; Luo, Z. Ferroptosis Nanomedicine: Clinical Challenges and Opportunities for Modulating Tumor Metabolic and Immunological Landscape. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15328–15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Wang, L.Y.; Li, S.J.; Tong, T.; Wang, L.; Huang, C.S.; Xu, Q.C.; Huang, X.T.; Li, J.H.; Wu, J.; et al. Histone Methyltransferase G9a Inhibitor-loaded Redox-responsive Nanoparticles for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Therapy. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 15767–15774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Liao, K.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, T.; Quan, G.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Application of Glutathione Depletion in Cancer Therapy: Enhanced ROS-based Therapy, Ferroptosis, and Chemotherapy. Biomaterials 2021, 277, 121110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Yang, K.; Sun, S. MnO2-Based Nanosystems for Cancer Therapy. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 7065–7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Tripathy, S.; Patra, C.R. Manganese-based Advanced Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: Future Opportunity and Challenges. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 16405–16426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folini, M.; Brambilla, C.; Villa, R.; Gandellini, P.; Vignati, S.; Paduano, F.; Daidone, M.G.; Zaffaroni, N. Antisense Oligonucleotide-mediated Inhibition of hTERT, but not hTERC, Induces Rapid Cell Growth Decline and Apoptosis in the Absence of Telomere Shortening in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckburg, A.; Dein, J.; Berei, J.; Puri, Z.S.N. Oligonucleotides and microRNAs Targeting Telomerase Subunits in Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Names | Sequences |

|---|---|

| Anti-hTERT-DNA | 5′-TCC ATG TTC ACA ATC GGC C-FAM-3′ |

| Anti-GPX4-DNA | 5′-GAT ACG CTG AGT GTG GTT T-Cy5-3′ |

| Control-DNA | 5′-CCA GAT CAA GAT CCA TTG A-3′ |

| hTERT-F-primer | 5′-CGG AAG AGT GTC TGG AGC AA-3′ |

| hTERT-R-primer | 5′-CAC GAC GTA GTC CAT GTT CA-3′ |

| GPX4-F-primer | 5′-AGA GAT CAA AGA GTT CGC CGC-3′ |

| GPX4-R-primer | 5′-TCT TCA TCC ACT TCC ACA GCG-3′ |

| GAPDH-F-primer | 5′-CTC AGA CAC CAT GGG GAA GGT GA-3′ |

| GAPDH-R-primer | 5′-ATG ATC TTG AGG CTG TTG TCA TA-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miao, Y.; Zhou, T.; Ji, Q.; Hong, M. Simultaneous Down-Regulation of Intracellular hTERT and GPX4 mRNA Using MnO2-Nanosheet Probes to Induce Cancer Cell Death. Sensors 2026, 26, 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030836

Miao Y, Zhou T, Ji Q, Hong M. Simultaneous Down-Regulation of Intracellular hTERT and GPX4 mRNA Using MnO2-Nanosheet Probes to Induce Cancer Cell Death. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):836. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030836

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Yixin, Tao Zhou, Qinghong Ji, and Min Hong. 2026. "Simultaneous Down-Regulation of Intracellular hTERT and GPX4 mRNA Using MnO2-Nanosheet Probes to Induce Cancer Cell Death" Sensors 26, no. 3: 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030836

APA StyleMiao, Y., Zhou, T., Ji, Q., & Hong, M. (2026). Simultaneous Down-Regulation of Intracellular hTERT and GPX4 mRNA Using MnO2-Nanosheet Probes to Induce Cancer Cell Death. Sensors, 26(3), 836. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26030836