Feature Augmentation-Based Adaptive Neural Network Control for Quadrotors

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

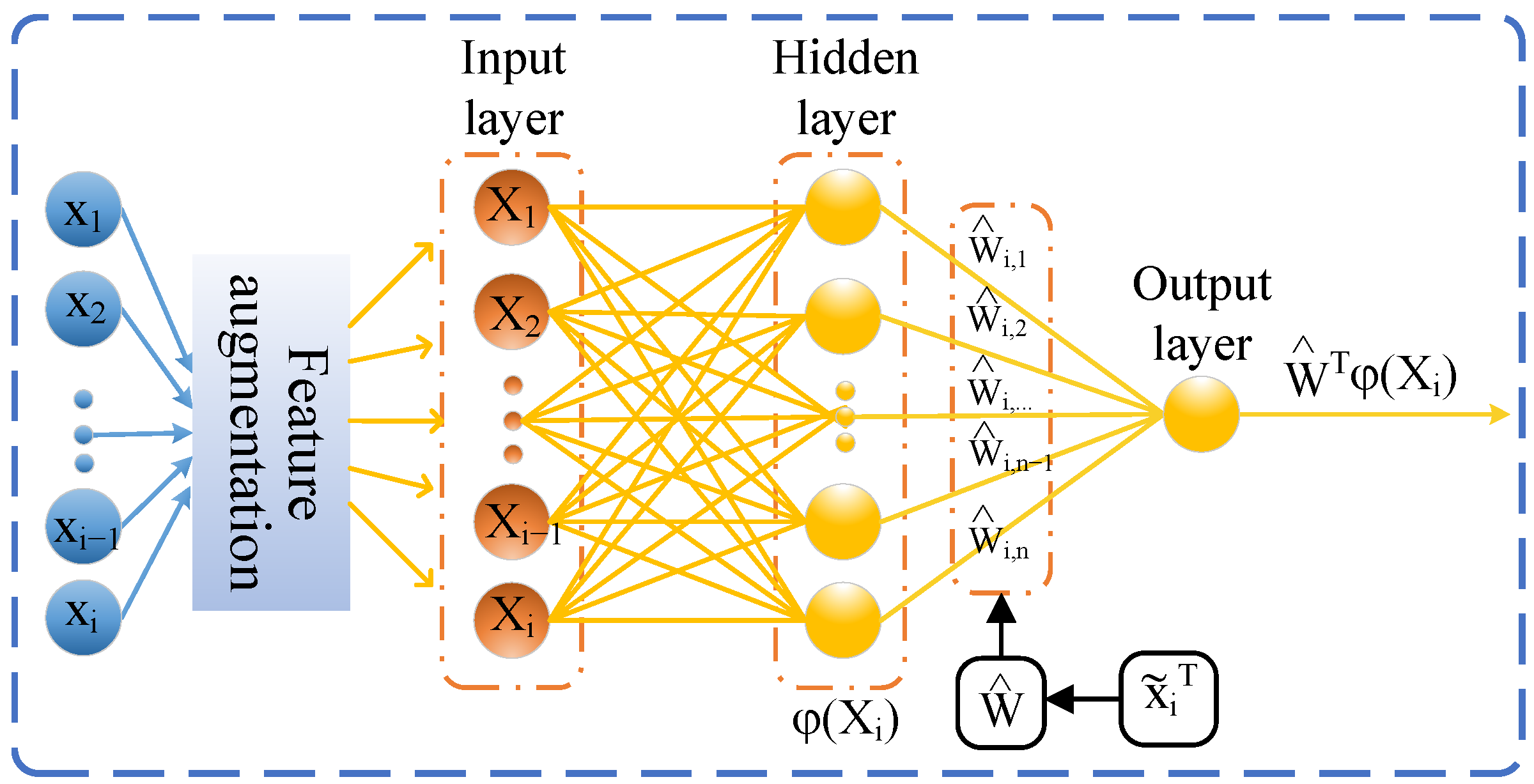

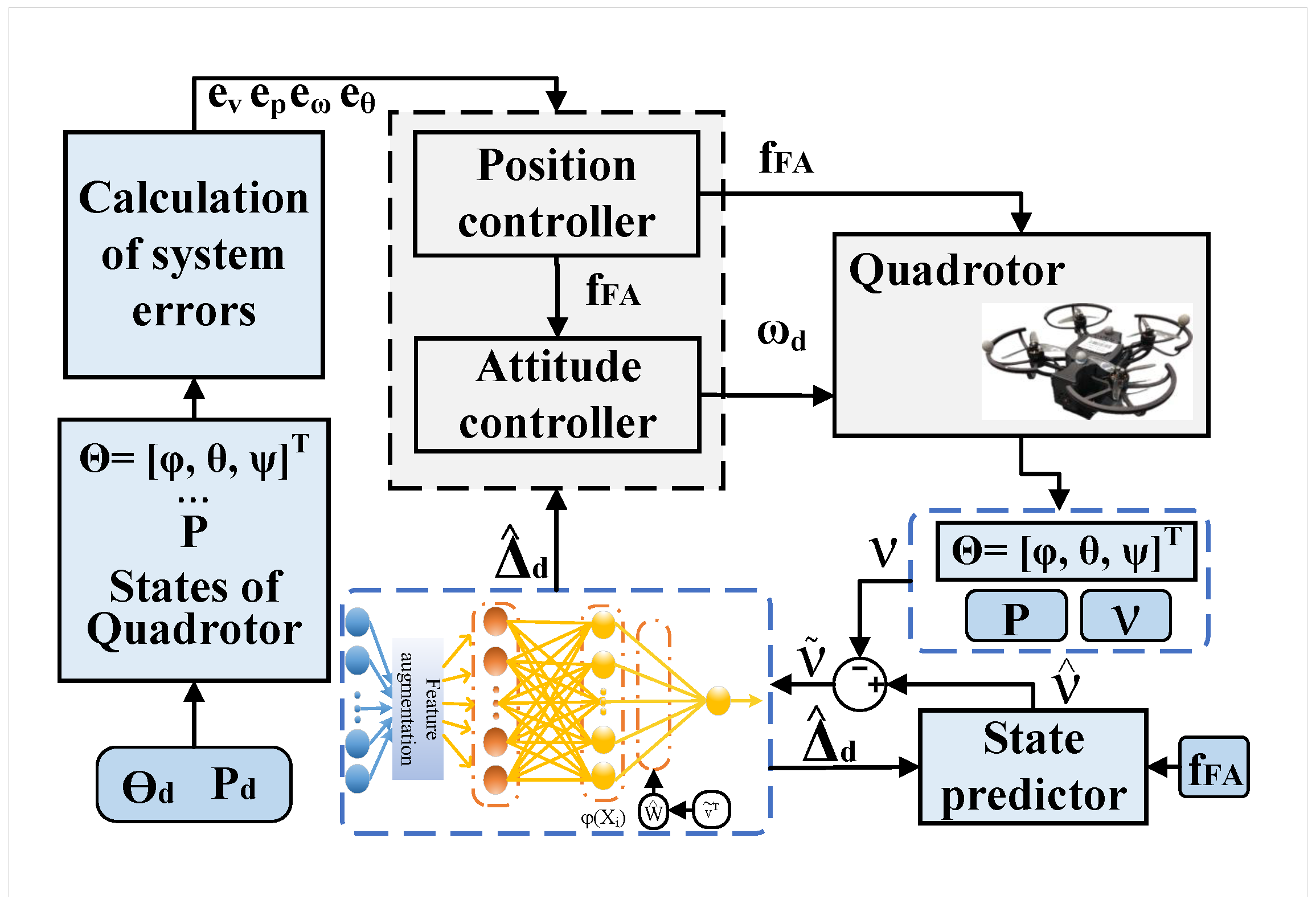

- Unlike the NN-based control techniques proposed in [3,4,9,14,16,23], as shown in Figure 1, our approach enhances characterization of the NNs inputs. By adding the FA layer to the NN structure, we improve the learning accuracy of NNs to approximate and compensate for unknown internal and external disturbance terms in quadrotors.

- 2.

- Compared with the existing literature [3,4,9,16,19,23], in addition to adding the FA layer, we design an SP to improve the NNs’ approximation speed to the unknown disturbance terms. This predictor estimates the NN inputs and updates the networks’ weights based on the estimation errors, rather than directly using the state errors.

- 3.

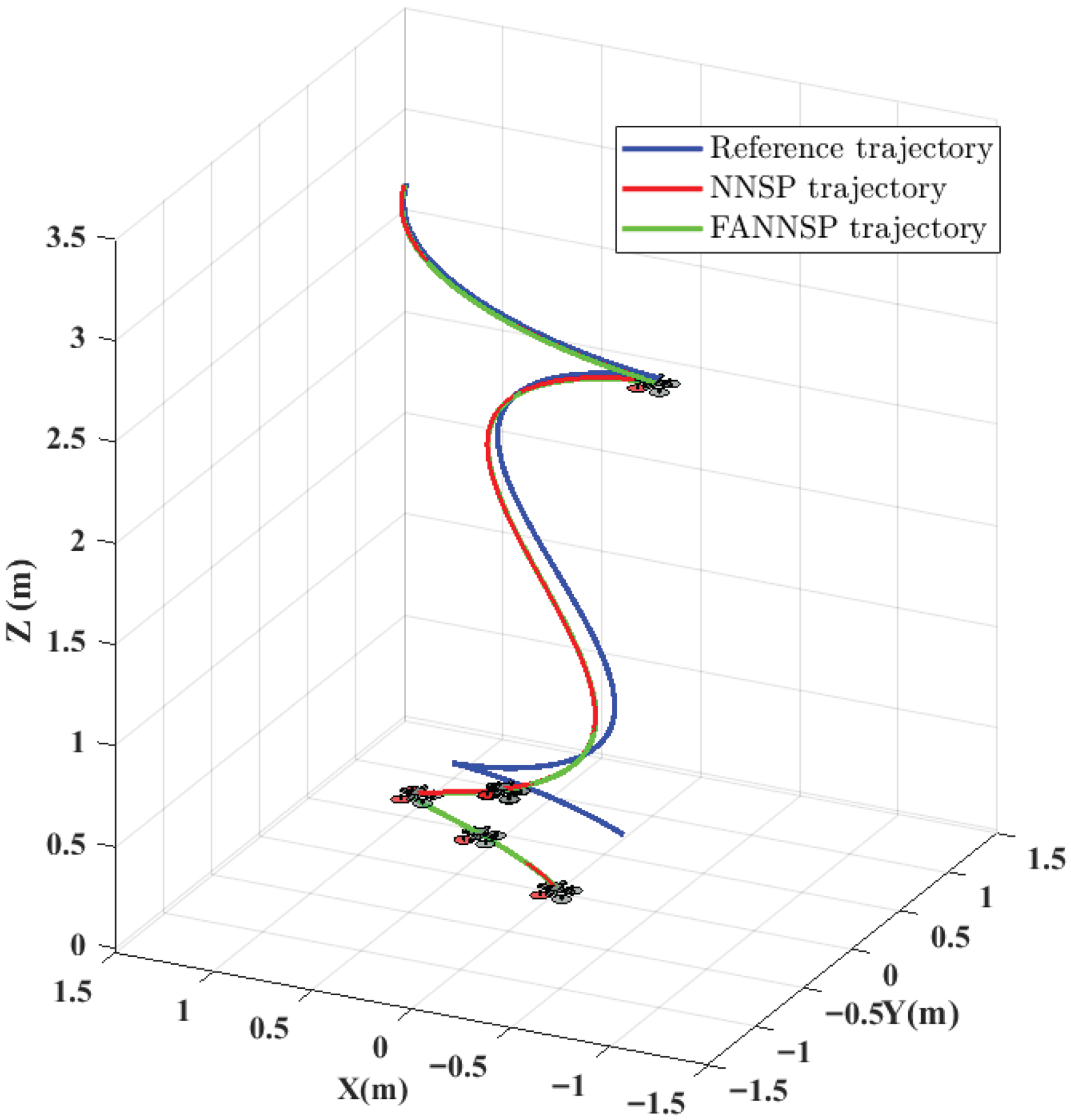

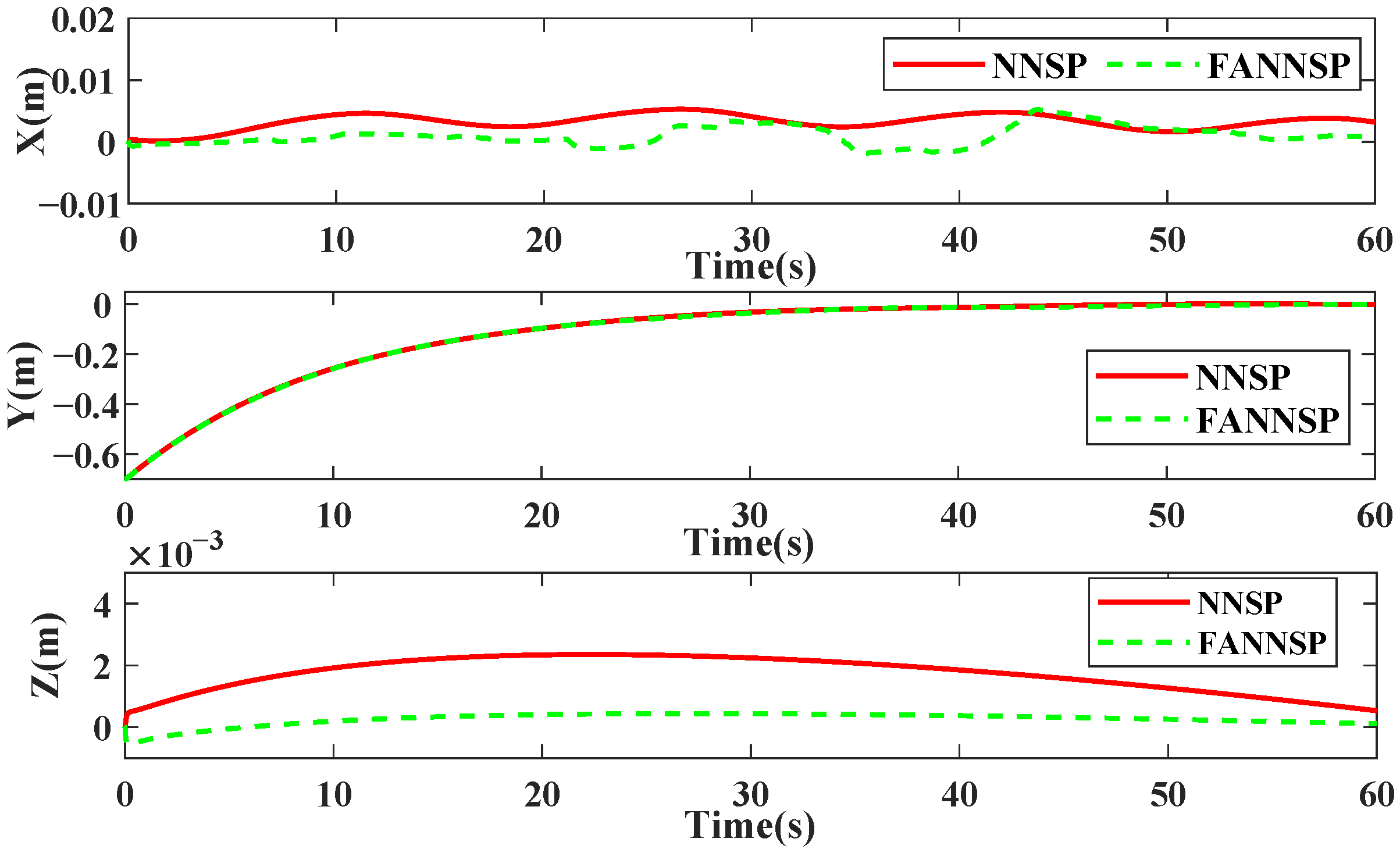

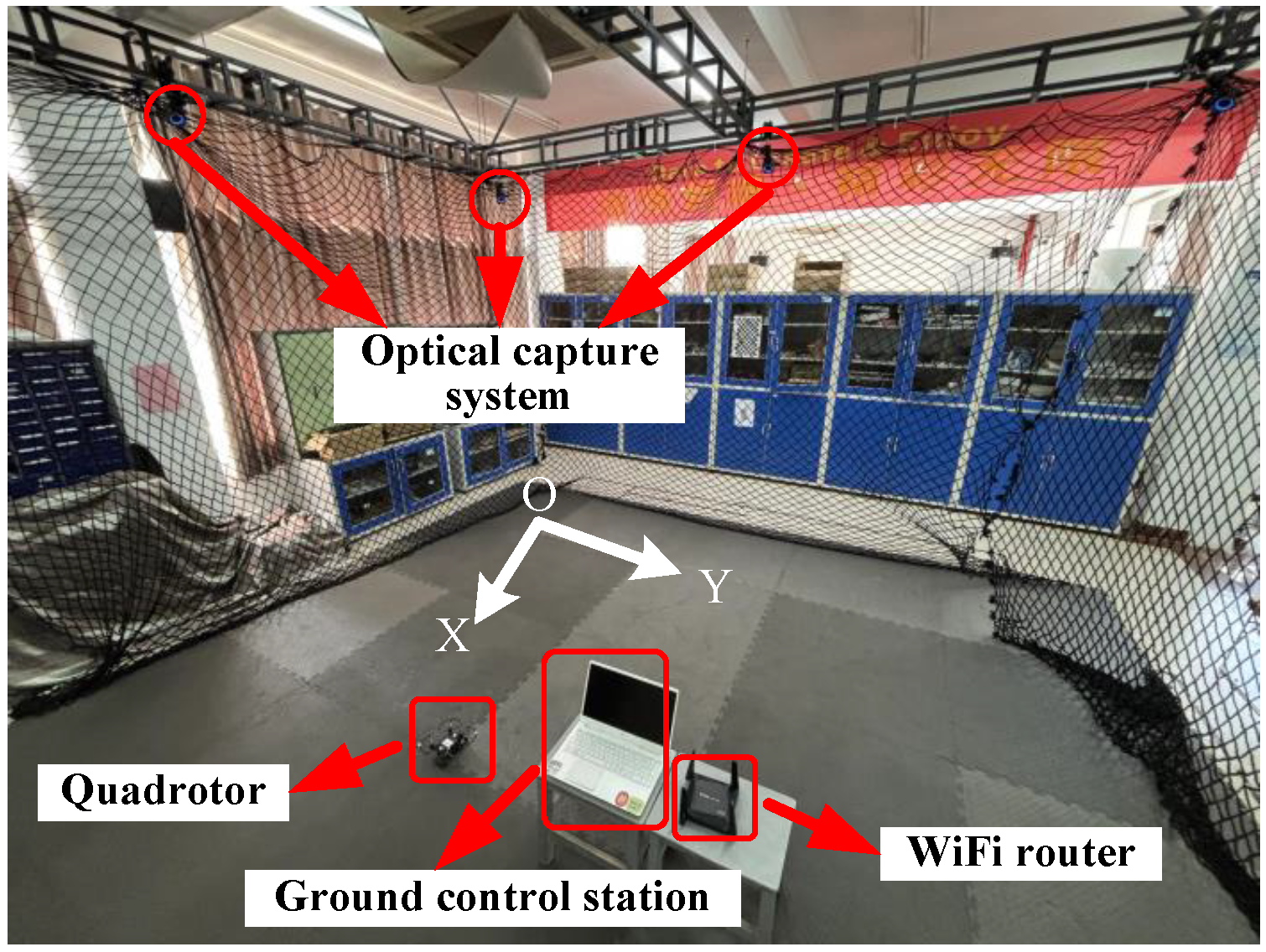

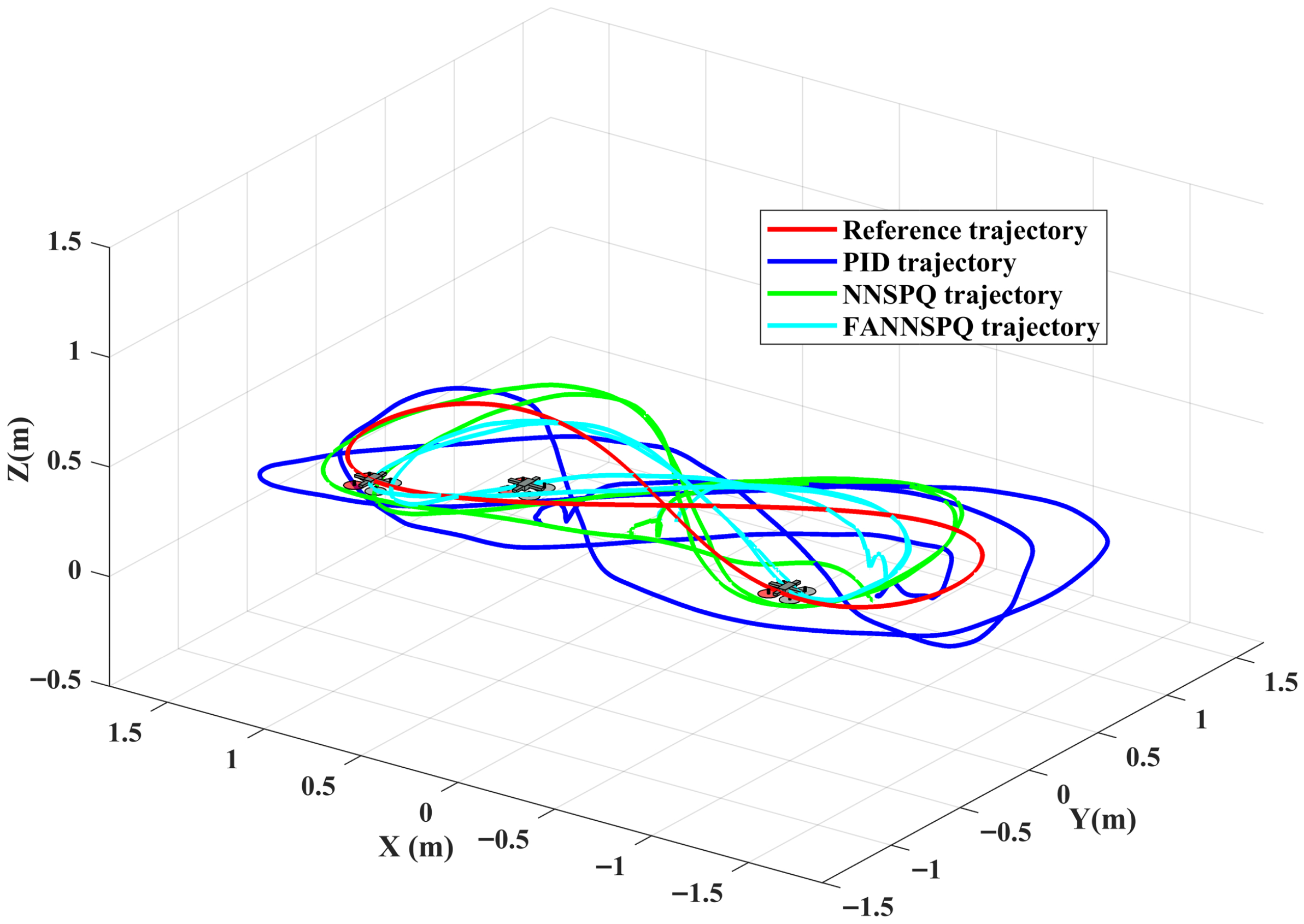

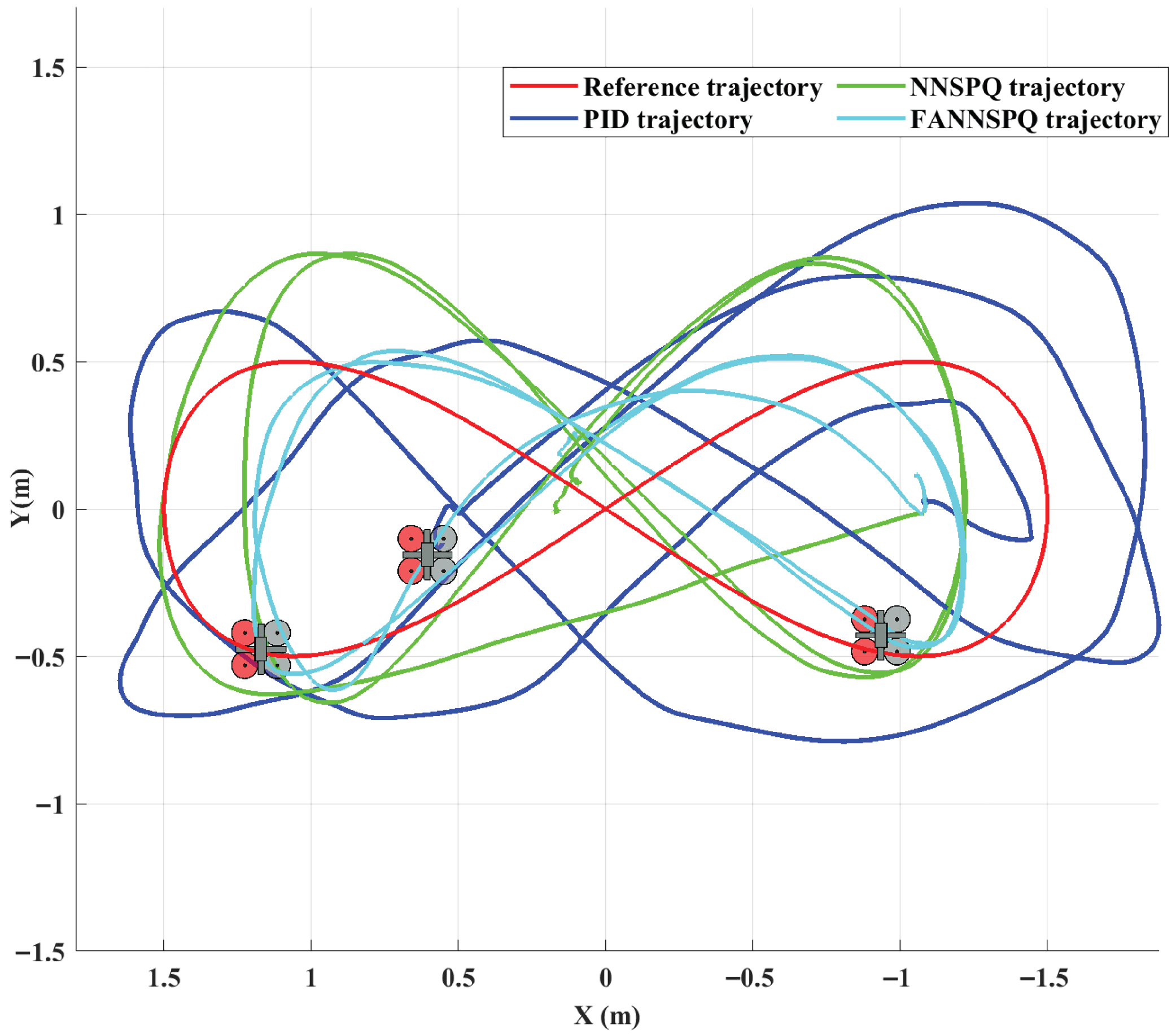

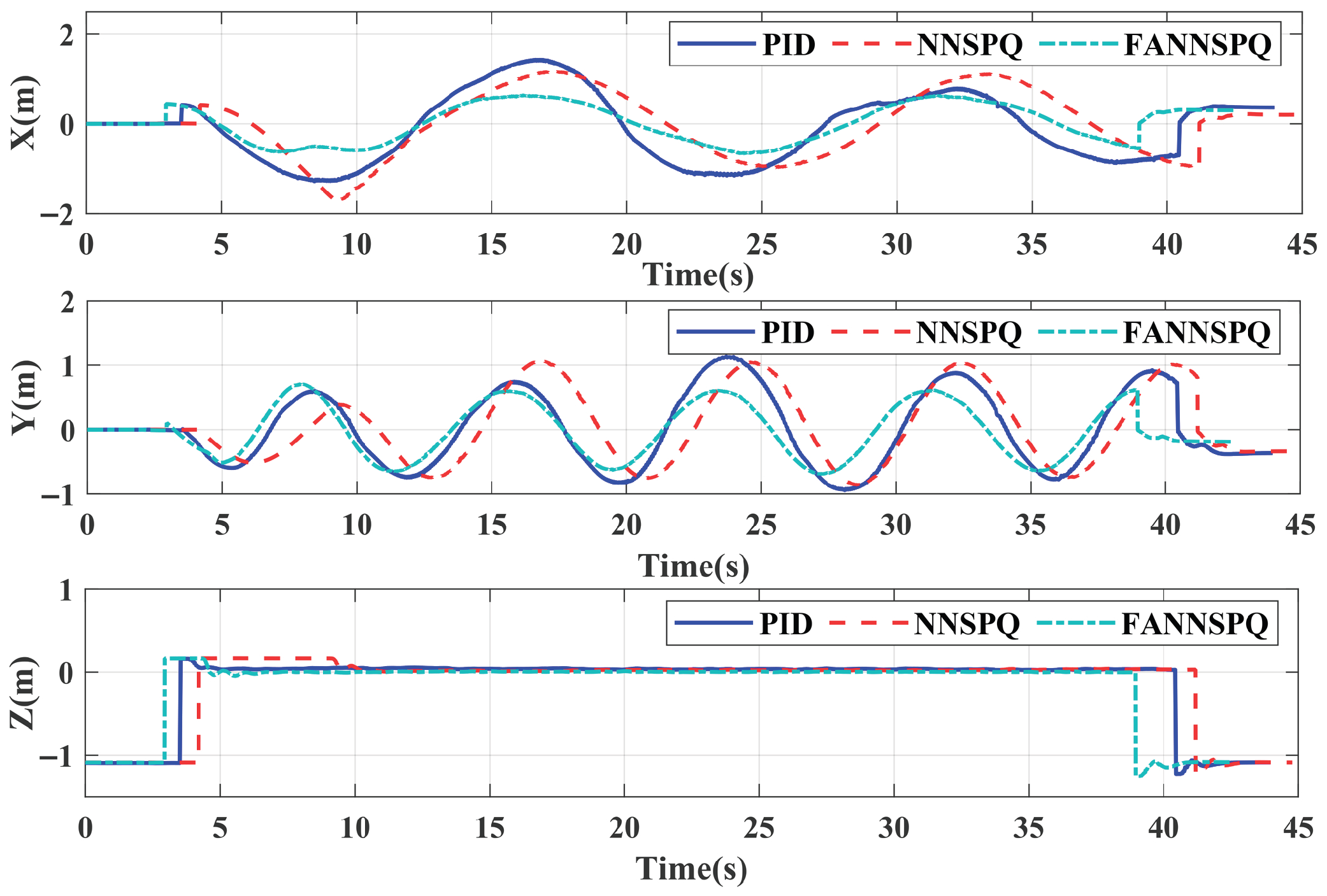

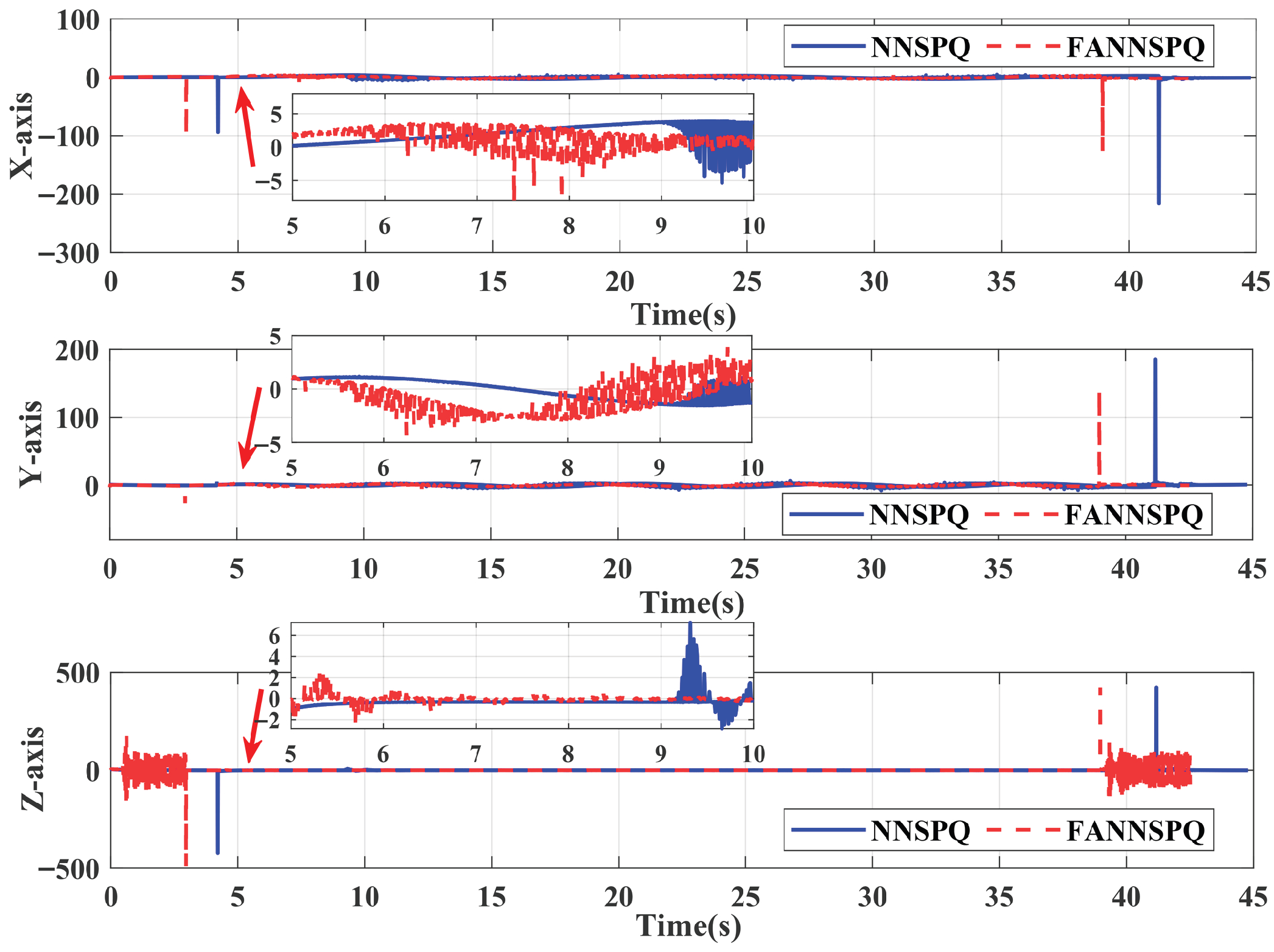

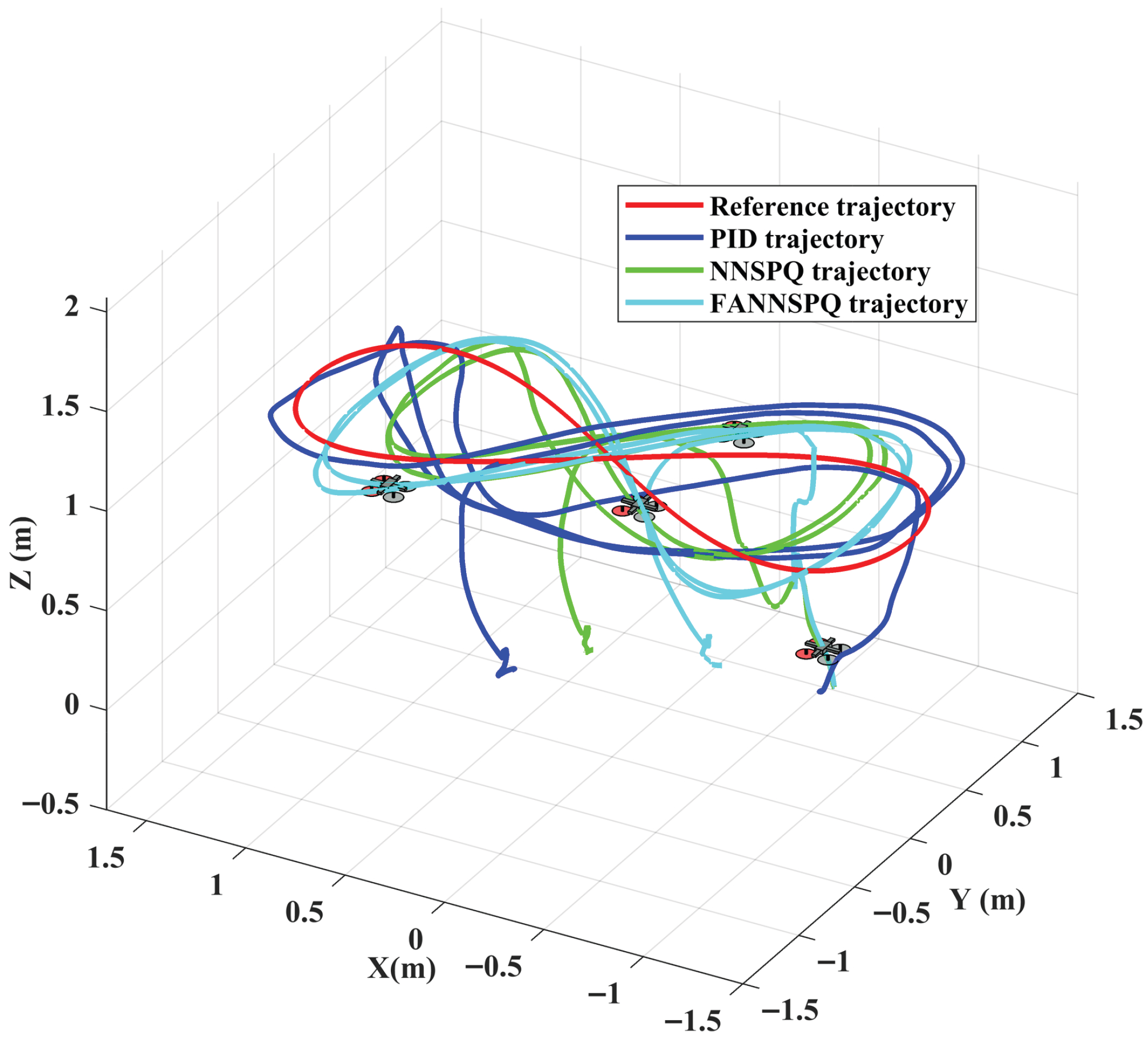

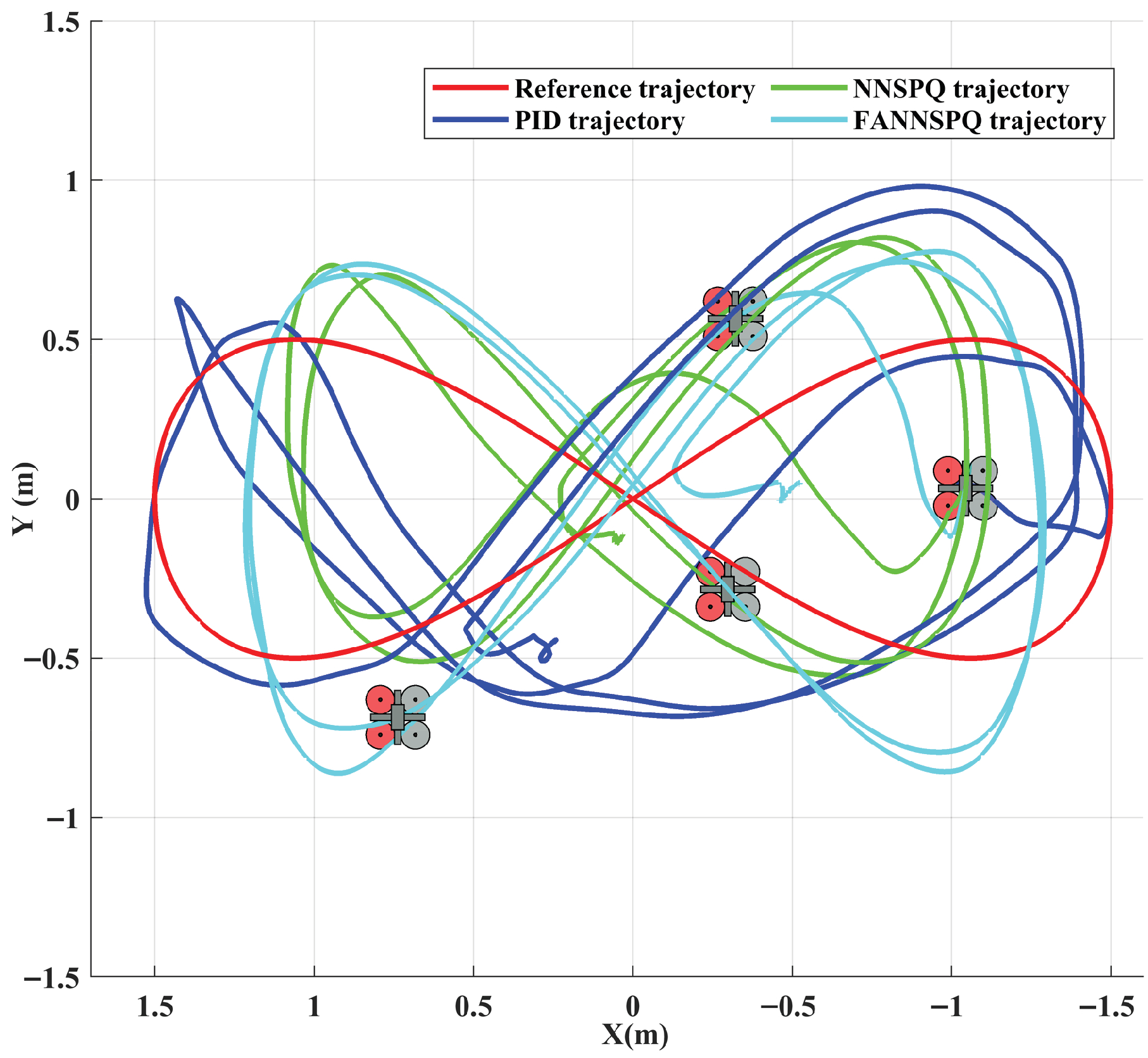

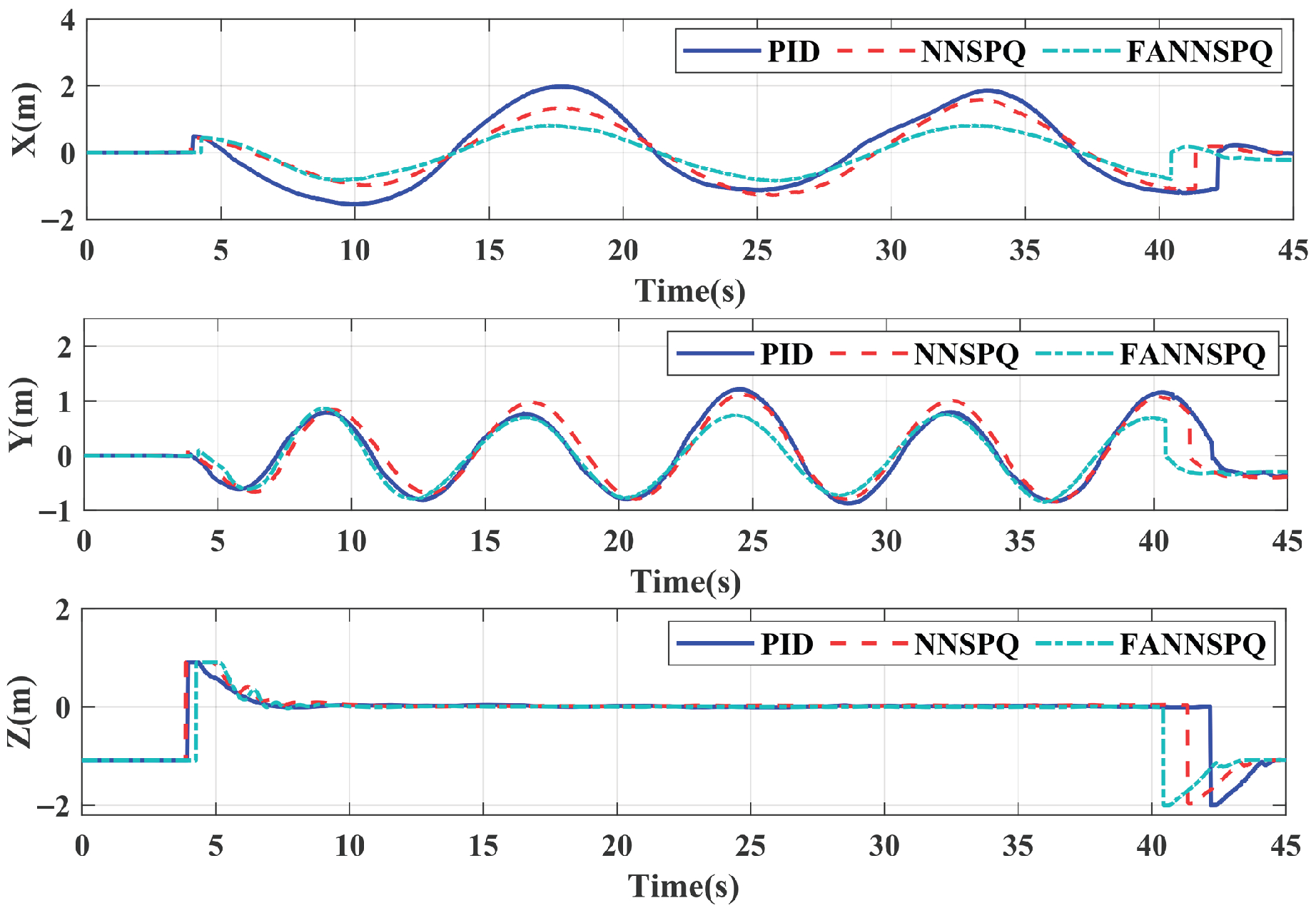

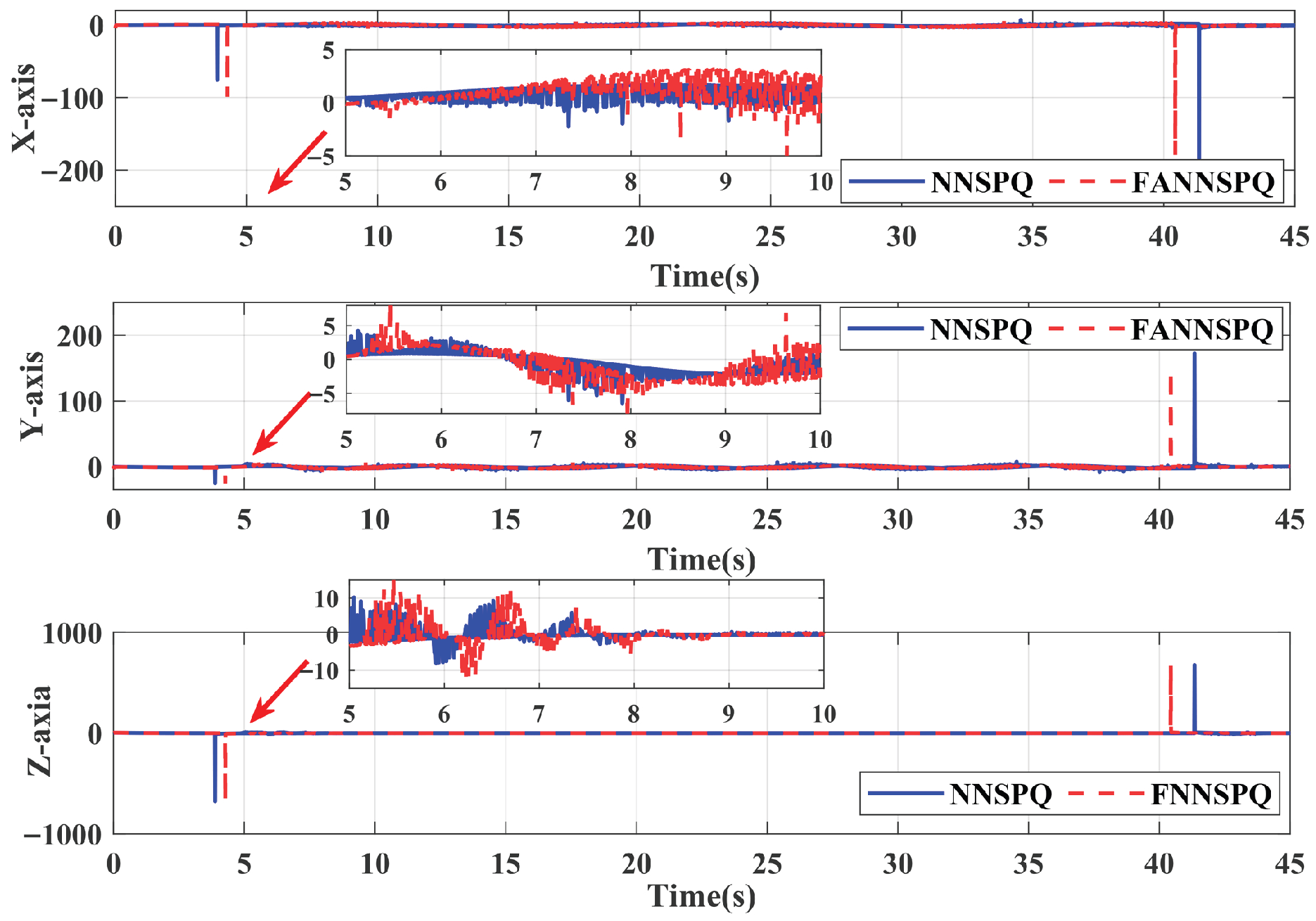

- Unlike previous studies such as [5,7], which validated NNs control only through simulations, our work includes both MATLAB/Simulink and real quadrotor experiments. We compared our ANN controller, based on the FA with SP against traditional PID and RBF NNs with SP controllers. The simulation and experiment results verify the effectiveness of our controller, which ensures the input-to-state stability (ISS) of the quadrotor system using the Lyapunov theory.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Notations

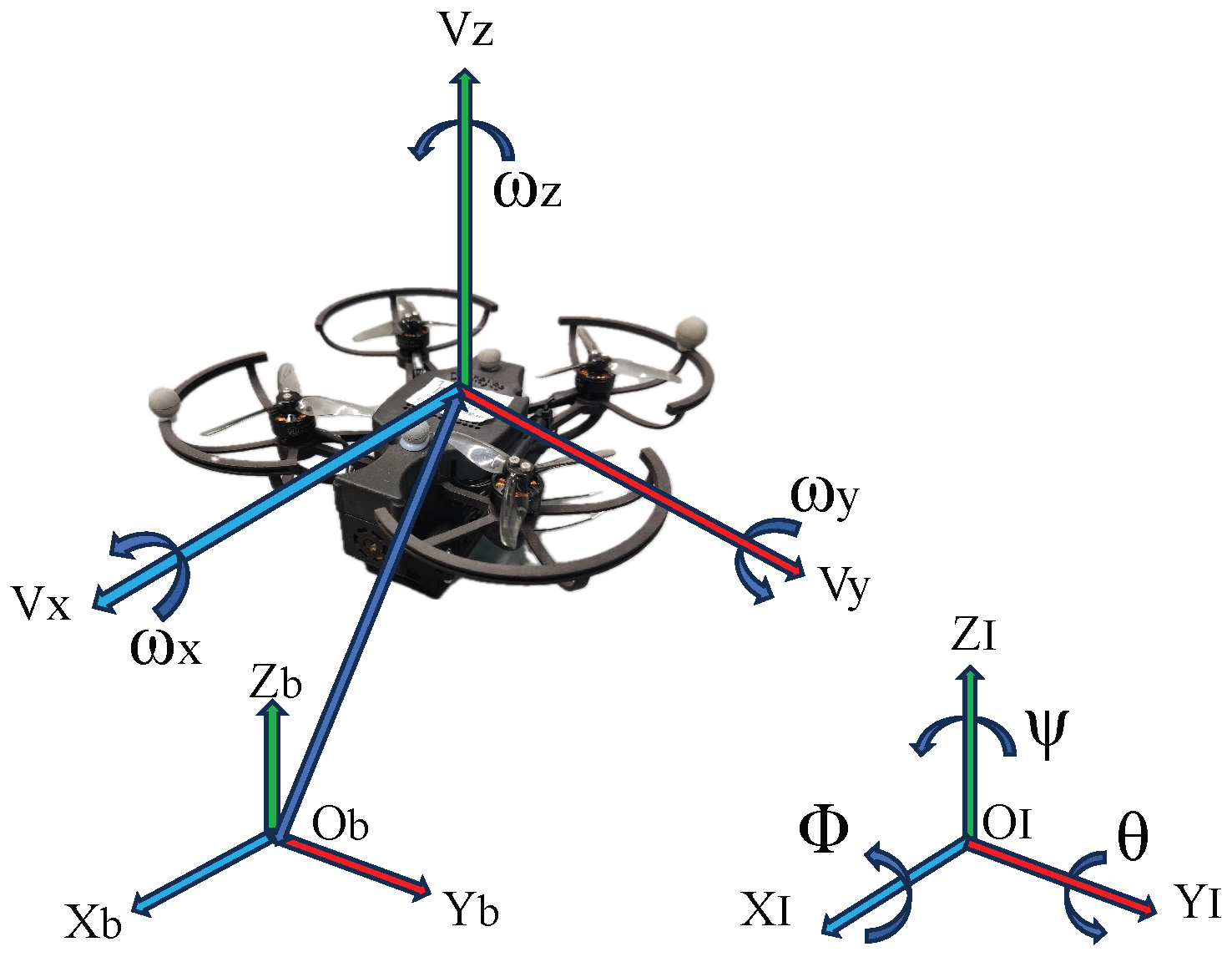

2.2. Quadrotor Model

2.3. NNs Based on FA Formulation

2.4. Control Objective

- 1.

- With the control laws designed in this paper, validated through simulation and experiments, the quadrotor can quickly track the desired trajectory .

- 2.

- We design ANN based on FA with an SP to estimate and compensate for unknown internal and external disturbance terms quickly and efficiently, compared to traditional RBF NNs.

- 3.

- The system errors converge to a small bounded area, and the closed system is proven to be ISS.

3. Controller Design

3.1. Position Sub-Controller

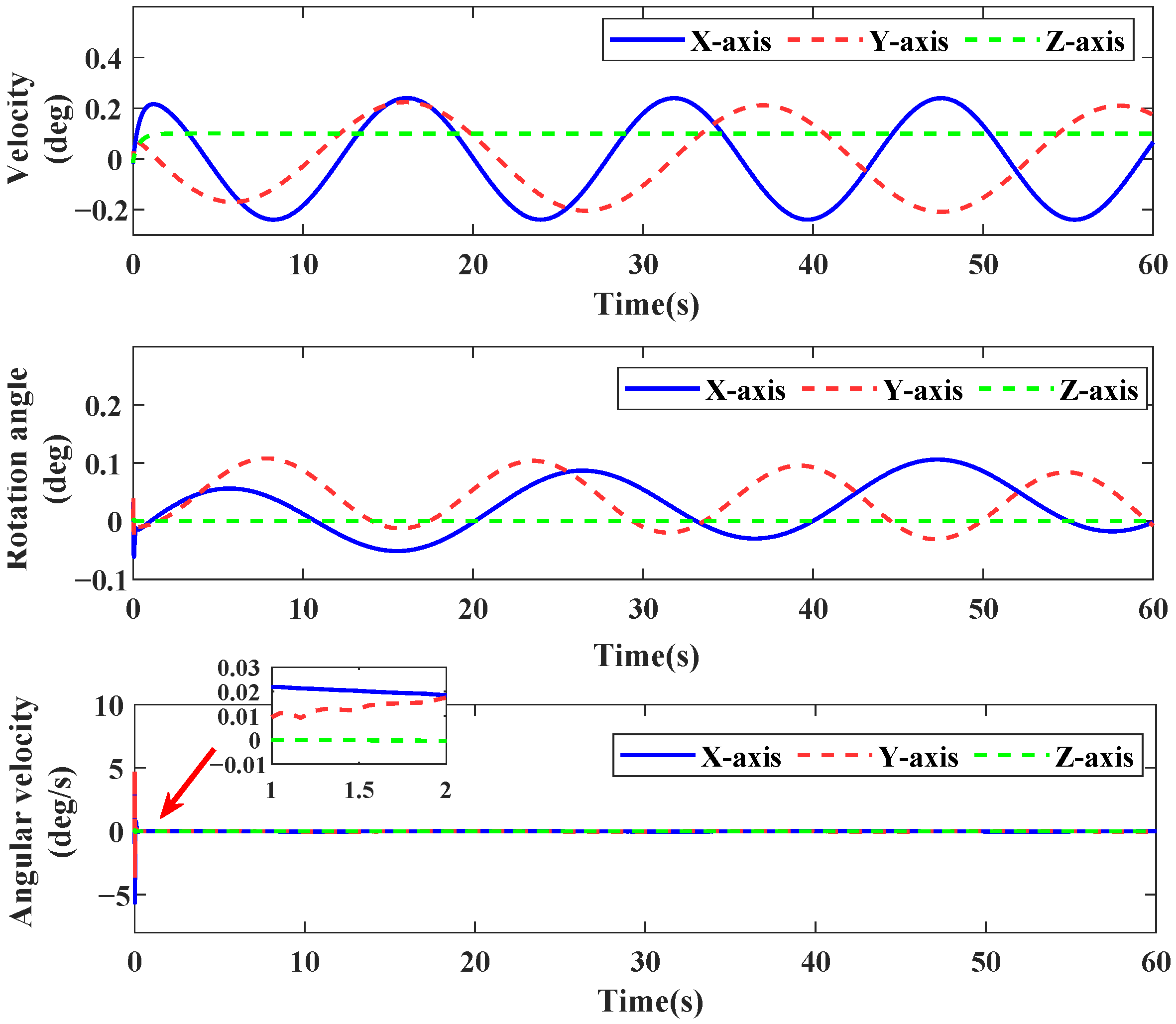

3.2. Attitude Sub-Controller

4. Stability Analysis

- (a) The Initial States without External Disturbances: Without external disturbances, the decay of the system states can be described by the function. We define the functions as , where represents the decay rate of the function. Assuming that there is no disturbance input, i.e., and , then:

- (b) Persistent Disturbances: In the presence of perturbing inputs, the following equation can be derived from (29):

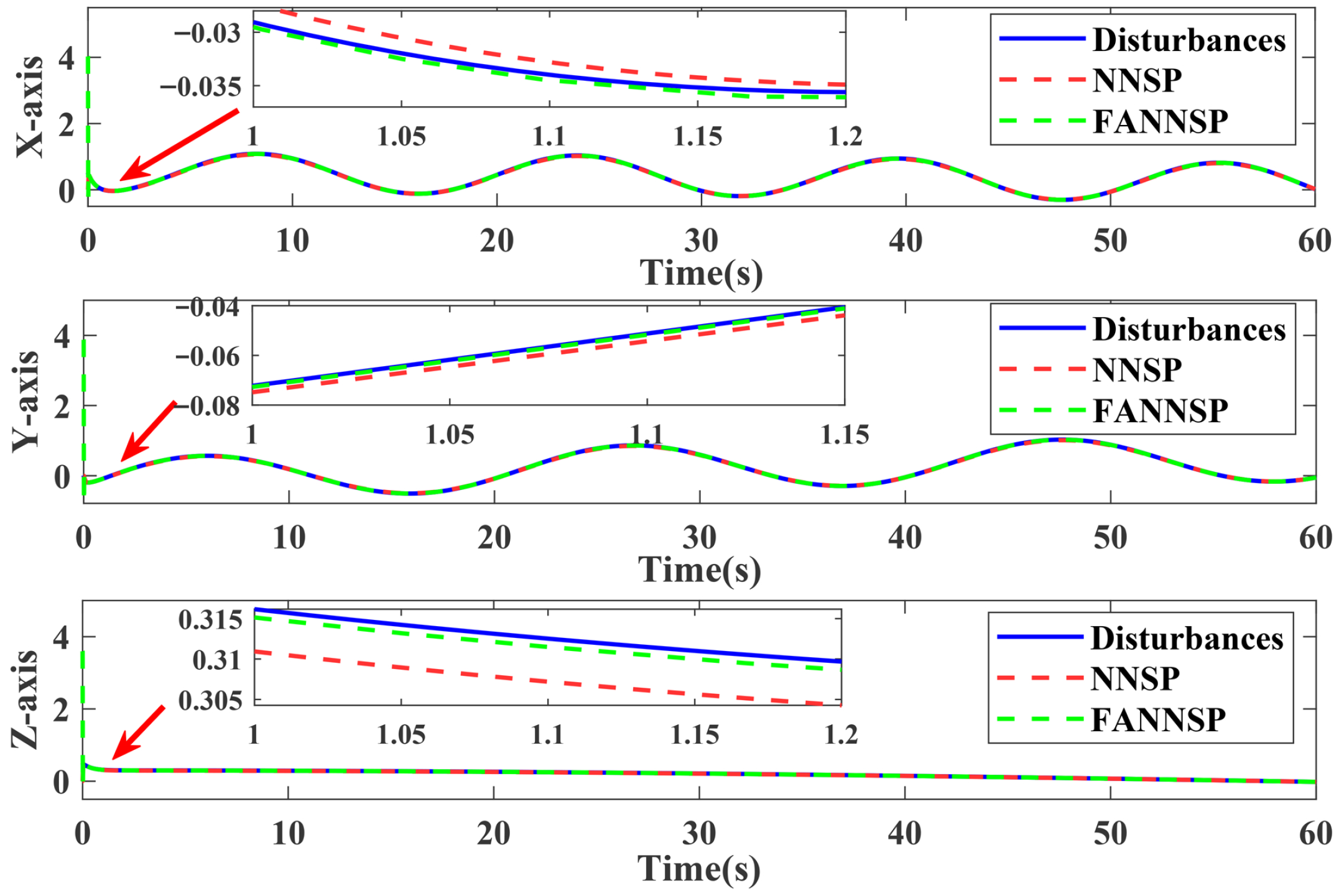

5. Simulation Examples

6. Experimental Results

6.1. Case 1

6.2. Case 2

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kan, X.; Thomas, J.; Teng, H.; Tanner, H.G.; Kumar, V.; Karydis, K. Analysis of Ground Effect for Small-Scale UAVs in Forward Flight. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 3860–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofano-Soldado, A.; Gonzalez-Morgado, A.; Heredia, G.; Ollero, A. Assessment and Modeling of the Aerodynamic Ground Effect of a Fully-Actuated Hexarotor with Tilted Propellers. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Reis, J.; Silvestre, C. Quadrotor Neural Network Adaptive Control: Design and Experimental Validation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2574–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ge, S.S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Adaptive Neural Control of MIMO Nonlinear Systems with a Block-Triangular Pure-Feedback Control Structure. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2014, 25, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Gong, W.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, B.; Ran, D. Appointed Fixed Time Observer-Based Sliding Mode Control for a Quadrotor UAV Under External Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Wang, R.; Jiao, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, J. Observer-Based Adaptive Fuzzy Finite-Time Attitude Control for Quadrotor UAVs. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 8637–8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P. Full control of a quadrotor using parameter-scheduled backstepping method: Implementation and experimental tests. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 89, 1259–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, W.; Qi, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Control of quadrotor robot via optimized nonlinear type-2 fuzzy fractional PID with fractional filter: Theory and experiment. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 151, 109286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Pourpanah, F.; Hao, Q. Design, implementation, and evaluation of a neural-network-based quadcopter UAV system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 2076–2085. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, T.; Zheng, L.; Luo, Y. A quadratic programming based neural dynamic controller and its application to UAVs for time-varying tasks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 6415–6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gao, H.; Wang, K.; Zhou, C.; Zong, Q.; Hua, C. Disturbance Observer-Based Finite-Time Control Design for a Quadrotor UAV with External Disturbance. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Xie, W.; Zhang, W.; Silvestre, C. Robust Saturated Formation Tracking Control of Multiple Quadrotors with Switching Communication Topologies. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 3744–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, Z. Robust Adaptive Control for a Quadrotor UAV with Uncertain Aerodynamic Parameters. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 8313–8326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, W.; Wu, E.Q.; Zhang, W. Tunnel Prescribed Performance Control for Distributed Path Maneuvering of Multi-UAV Swarms via Distributed Neural Predictor. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 3830–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, J. Predictor-Based Neural Dynamic Surface Control for Uncertain Nonlinear Systems in Strict-Feedback Form. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 28, 2156–2167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yogi, S.C.; Tripathi, V.K.; Behera, L. Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control Using Fully Connected Recurrent Neural Network for Position and Attitude Control of Quadrotor. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 5595–5609. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, G.; Hao, W.; Feng, W.; Gao, K. Optimized backstepping tracking control using reinforcement learning for quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2021, 52, 5004–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H. Transition control of a tail-sitter unmanned aerial vehicle with L1 neural network adaptive control. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Chen, X.; Su, C.Y. Discrete-time adaptive neural tracking control and its experiments for quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle systems. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mech. 2021, 28, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Li, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Tang, S. Nonlinear adaptive tracking control for a small-scale unmanned helicopter using a learning algorithm with the least parameters. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 89, 1289–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Lu, J.G.; Zhang, W. Constrained Safe Cooperative Maneuvering of Autonomous Surface Vehicles: A Control Barrier Function Approach. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2024, 55, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ji, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Transient-Reinforced Tunnel Coordinated Control of Underactuated Marine Surface Vehicles with Actuator Faults. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Liu, K.; Liu, M.; Chen, G.; Huang, T. Adaptive Neural Network-Quantized Tracking Control of Uncertain Unmanned Surface Vehicles with Output Constraints. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 3293–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Cabecinhas, D.; Cunha, R.; Silvestre, C. Adaptive Backstepping Control of a Quadcopter with Uncertain Vehicle Mass, Moment of Inertia, and Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, G.; Xie, W.; Zhang, W.; Silvestre, C. Cooperative Path Following Control of a Team of Quadrotor-Slung-Load Systems Under Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 4169–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoori, A.O.; Motai, Y. Multicolumn RBF Network. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 766–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Ma, L.; Fan, X.; Luo, Z. Learning Hadamard-Product-Propagation for Image Dehazing and Beyond. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J. Dendrite Net: A White-Box Module for Classification, Regression, and System Identification. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 13774–13787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; Liu, B.; Guo, H.; Tang, R.; Zhou, F.; Zafeiriou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z. AutoHash: Learning Higher-Order Feature Interactions for Deep CTR Prediction. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 2653–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Symbols and Values |

|---|---|

| = diag; | |

| Error | = diag; |

| Coefficients | = diag; |

| = diag. | |

| Quadrotor | (kg); |

| Parameters | . |

| FANNSP | = diag; |

| Parameters | = 10,000; . |

| The Unknown | |

| Disturbance | |

| Terms | . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, B.; Huang, M. Feature Augmentation-Based Adaptive Neural Network Control for Quadrotors. Sensors 2026, 26, 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031078

Song B, Huang M. Feature Augmentation-Based Adaptive Neural Network Control for Quadrotors. Sensors. 2026; 26(3):1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031078

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Bang, and Mengxing Huang. 2026. "Feature Augmentation-Based Adaptive Neural Network Control for Quadrotors" Sensors 26, no. 3: 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031078

APA StyleSong, B., & Huang, M. (2026). Feature Augmentation-Based Adaptive Neural Network Control for Quadrotors. Sensors, 26(3), 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26031078