Attention-Enhanced CNN-LSTM with Spatial Downscaling for Day-Ahead Photovoltaic Power Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

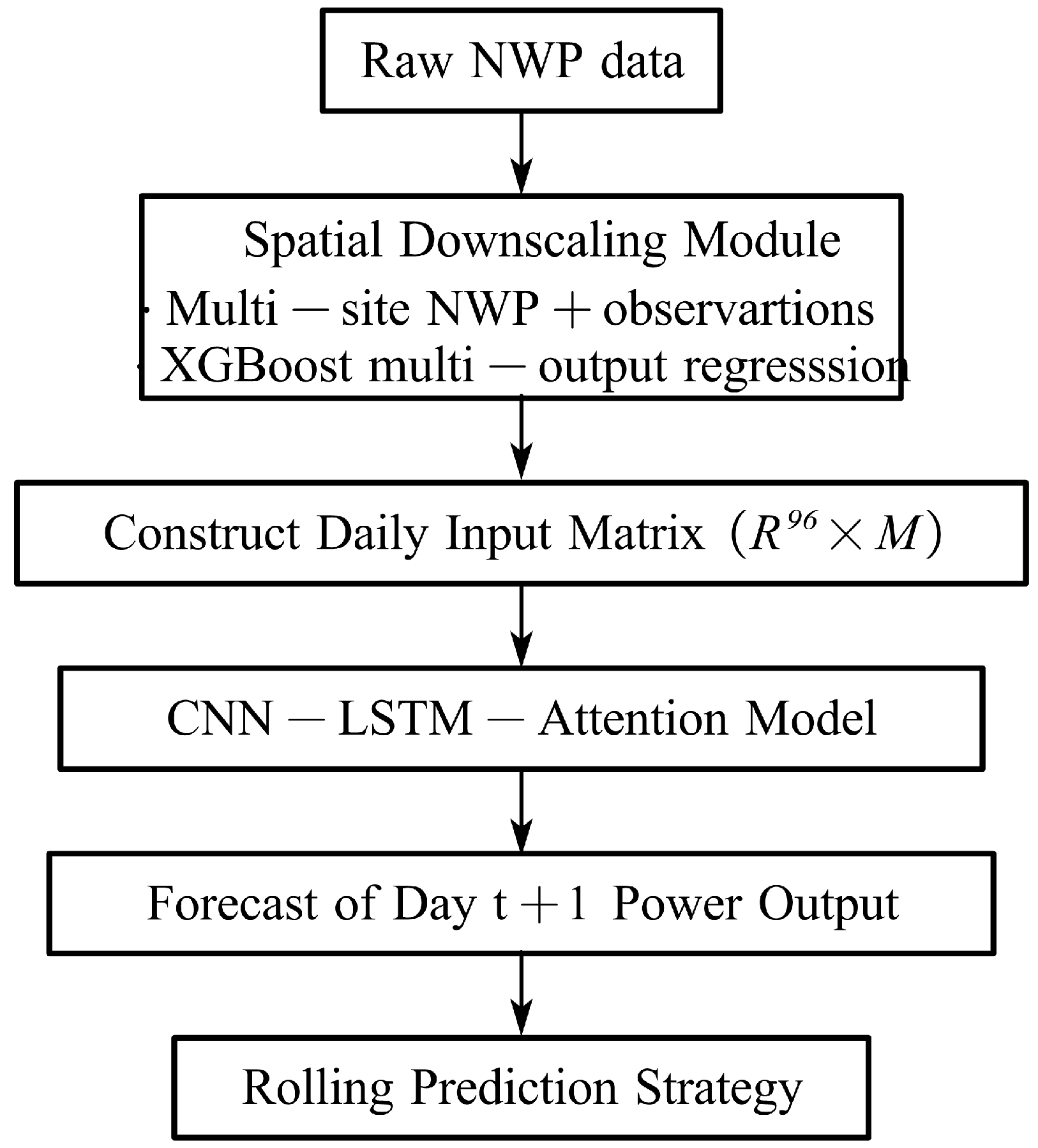

- A leakage-free, modular two-stage pipeline is established to decouple (i) spatial representativeness correction of coarse-resolution NWP fields and (ii) temporal dependency learning for day-ahead PV power forecasting, while coupling them through a clear interface in which the downscaled site-level meteorological variables serve as the exclusive exogenous inputs to the forecaster. A strict cross-station transfer protocol is adopted such that the target station contributes no measurement pairs during downscaling training, improving practical applicability under limited target-site supervision.

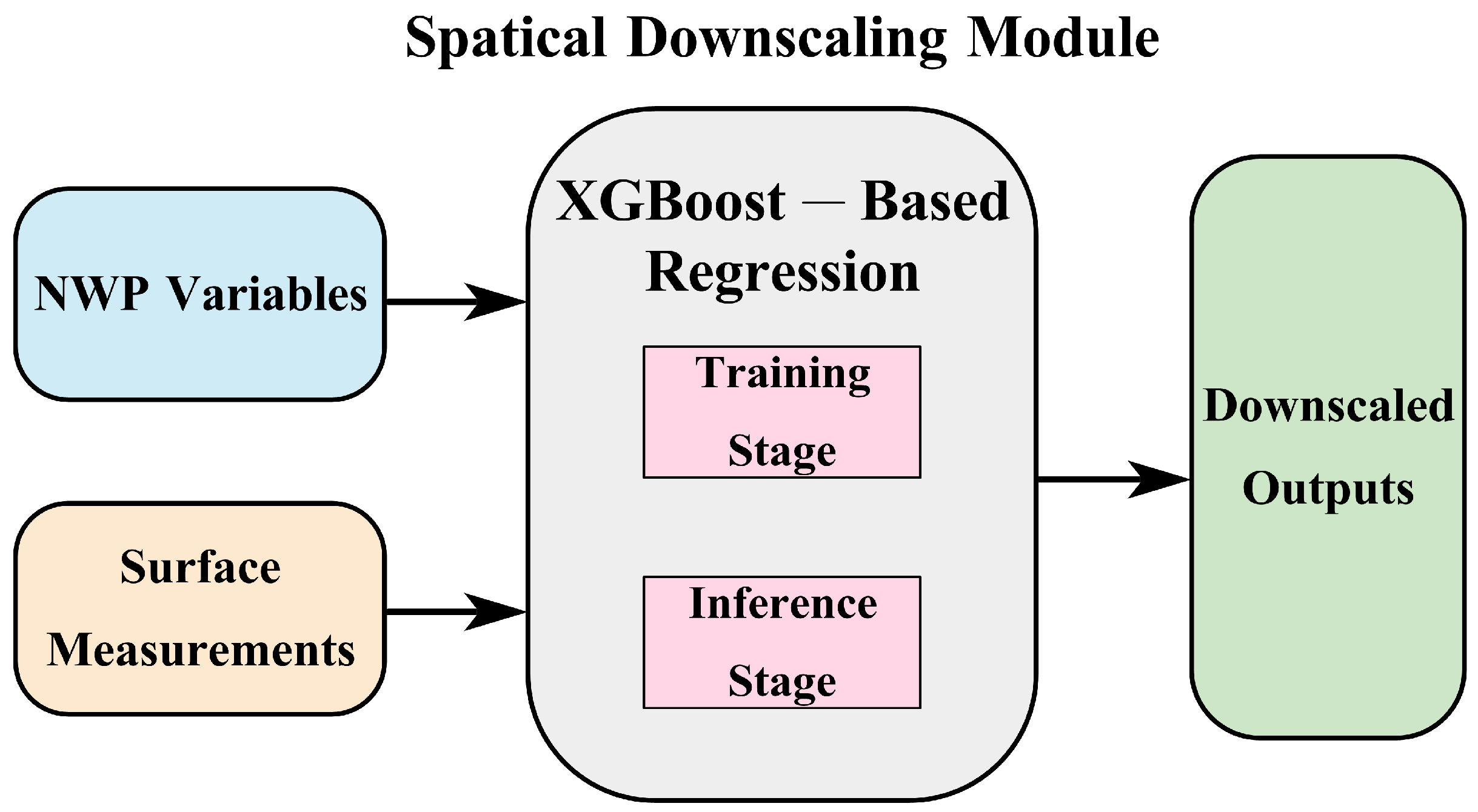

- A multi-site, multi-output spatial downscaling module is constructed using XGBoost to learn a nonlinear mapping from location/time encodings and heterogeneous NWP predictors to site-level meteorological vectors, trained only with measurement-based pairs from surrounding stations. This design enables plant-specific, high-resolution meteorological features to be generated from coarse NWP inputs, thereby reducing NWP-induced spatial bias at the target plant.

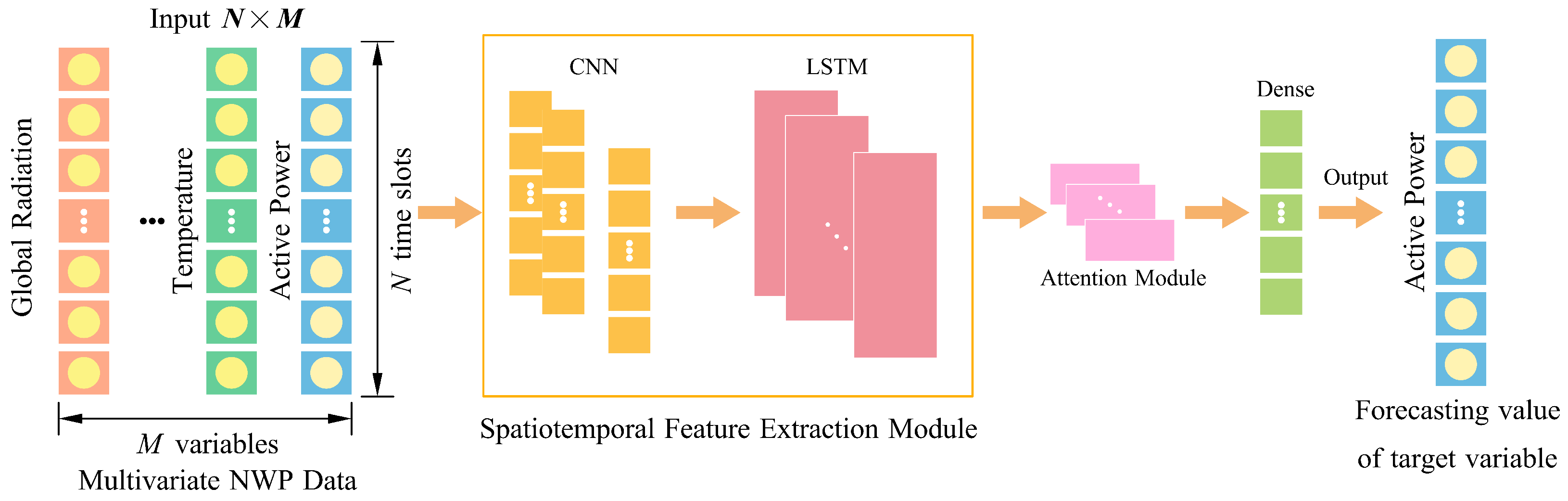

- An attention-enhanced CNN–LSTM forecasting model is developed to jointly capture short-term local patterns and long-term temporal dependencies, and to adaptively fuse multi-source meteorological predictors (irradiance, temperature, humidity, wind, etc.) with historical PV power. Comprehensive experiments on a multi-station PV dataset across representative months and across input/model configurations validate consistent accuracy improvements over baseline architectures in terms of RMSE, MAE, and correlation.

2. Modeling and Analysis of Photovoltaic Power Output

2.1. Theoretical Model of PV Power Output

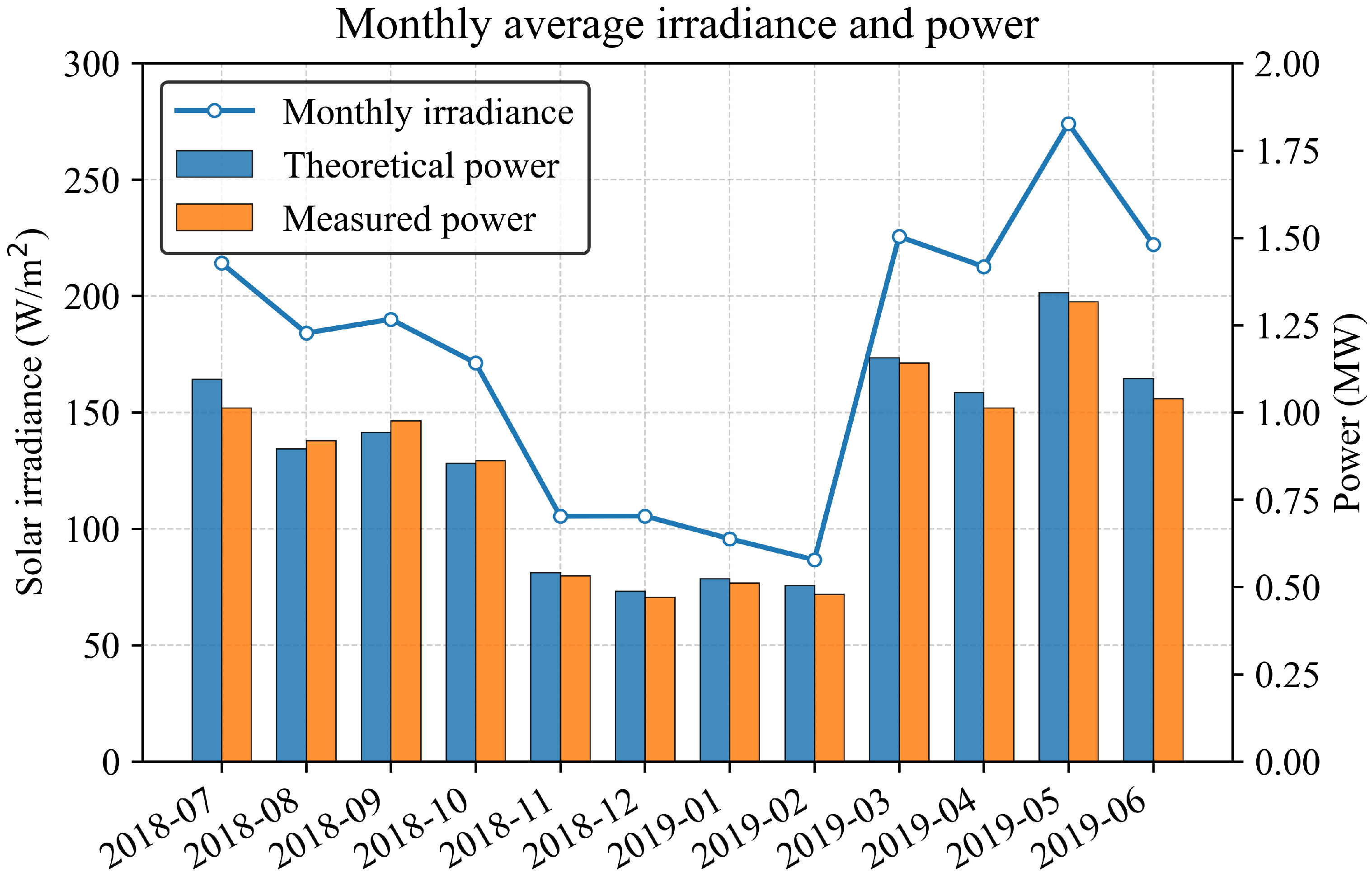

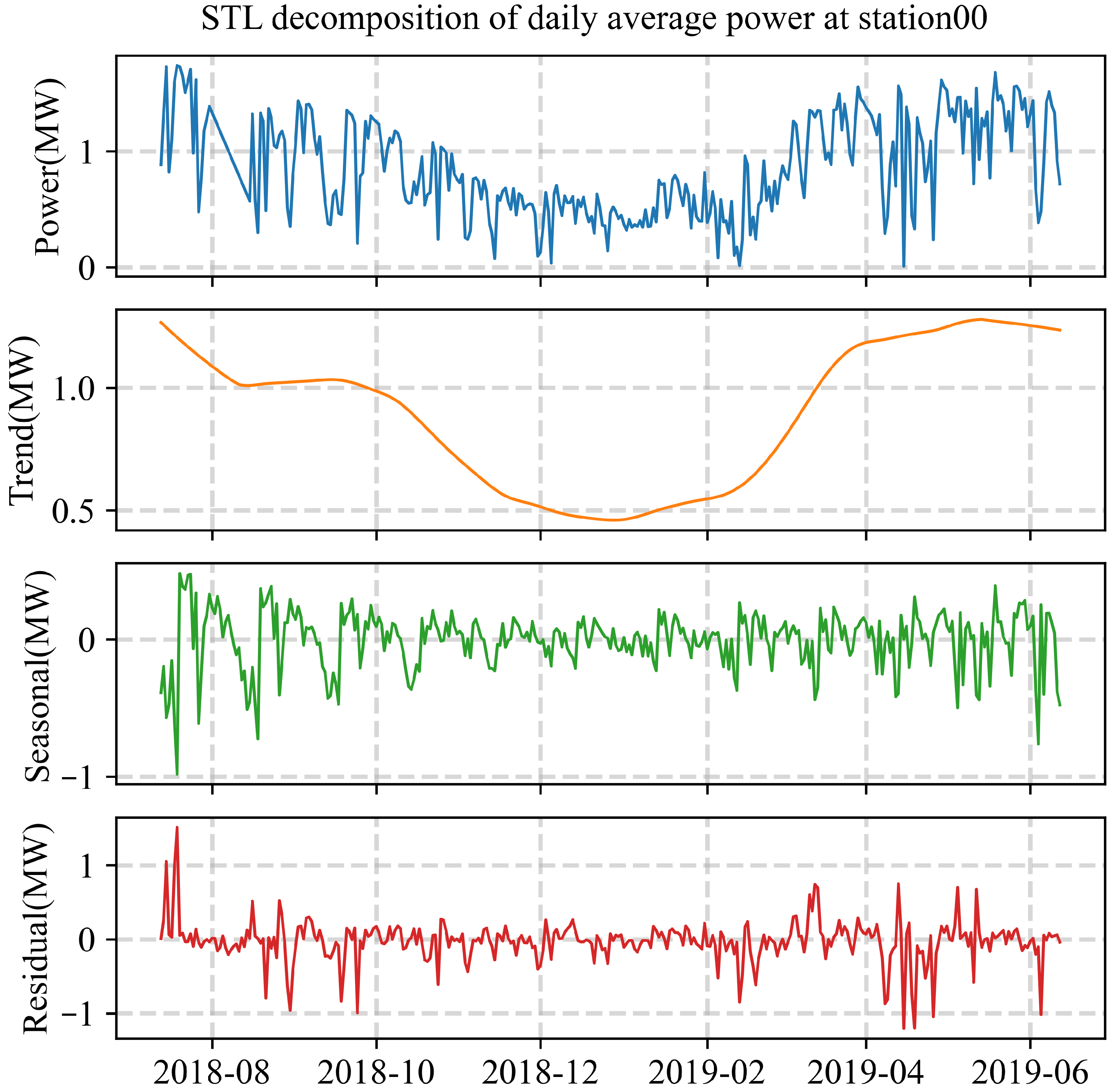

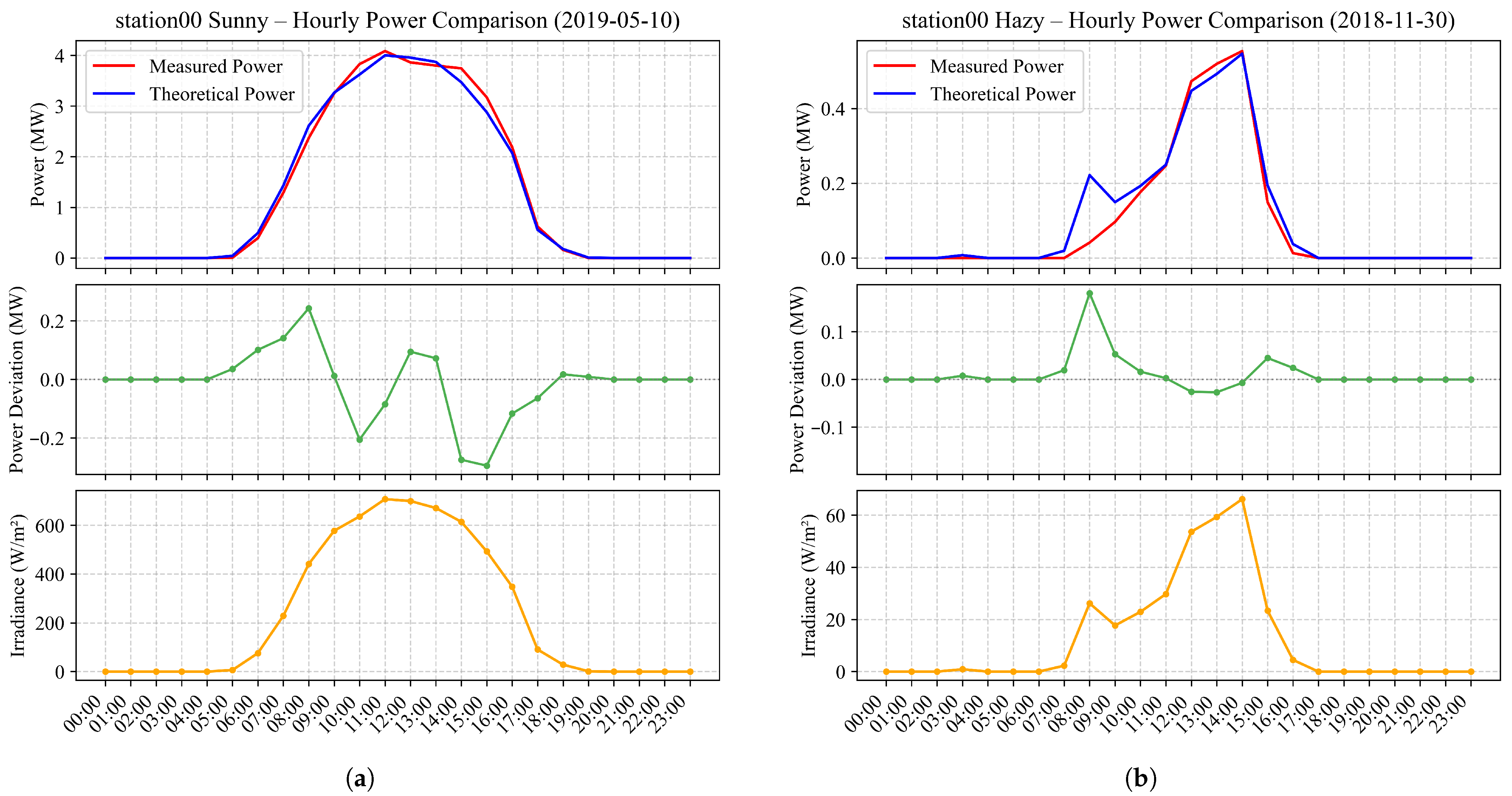

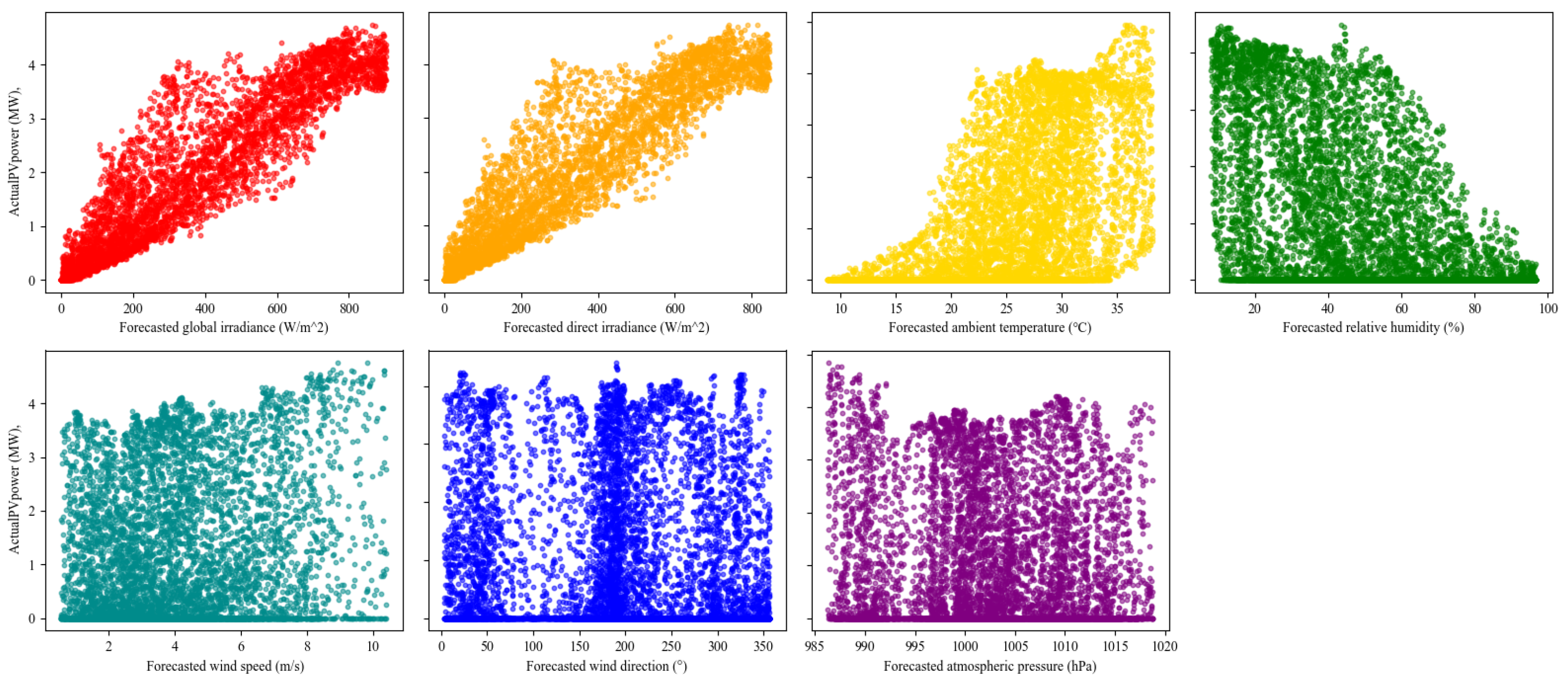

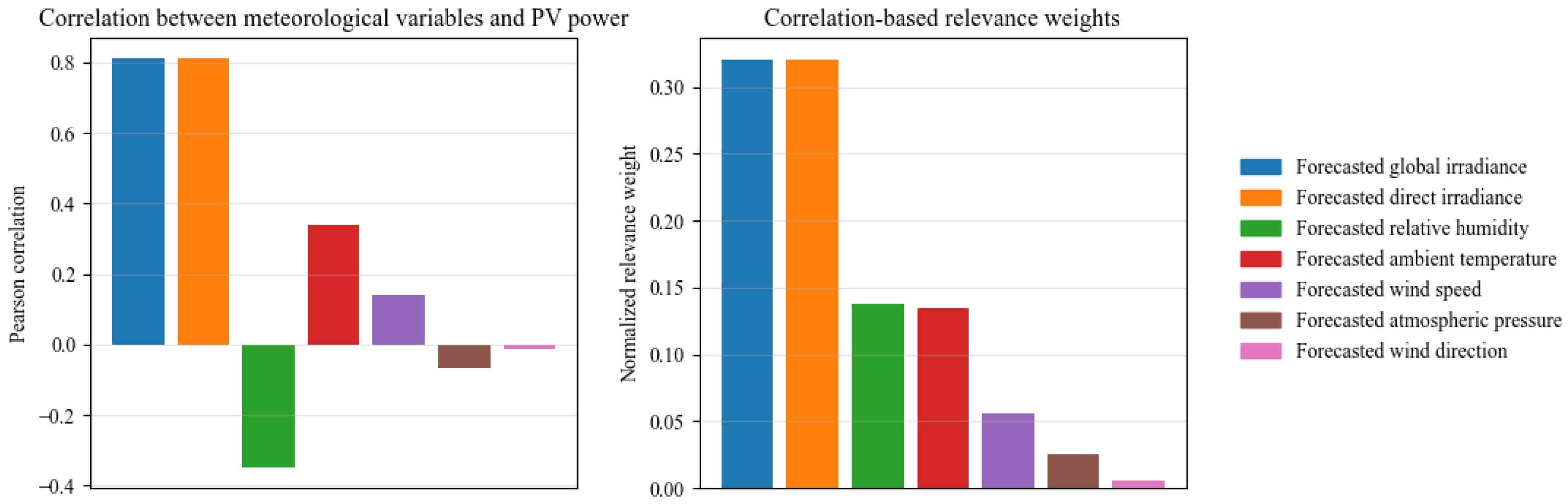

2.2. Photovoltaic Power Generation Characteristics

3. Structure of the Attention-Enhanced Multivariate CNN–LSTM Model with Spatial Downscaling

3.1. Attention-Enhanced CNN–LSTM Architecture

- (1)

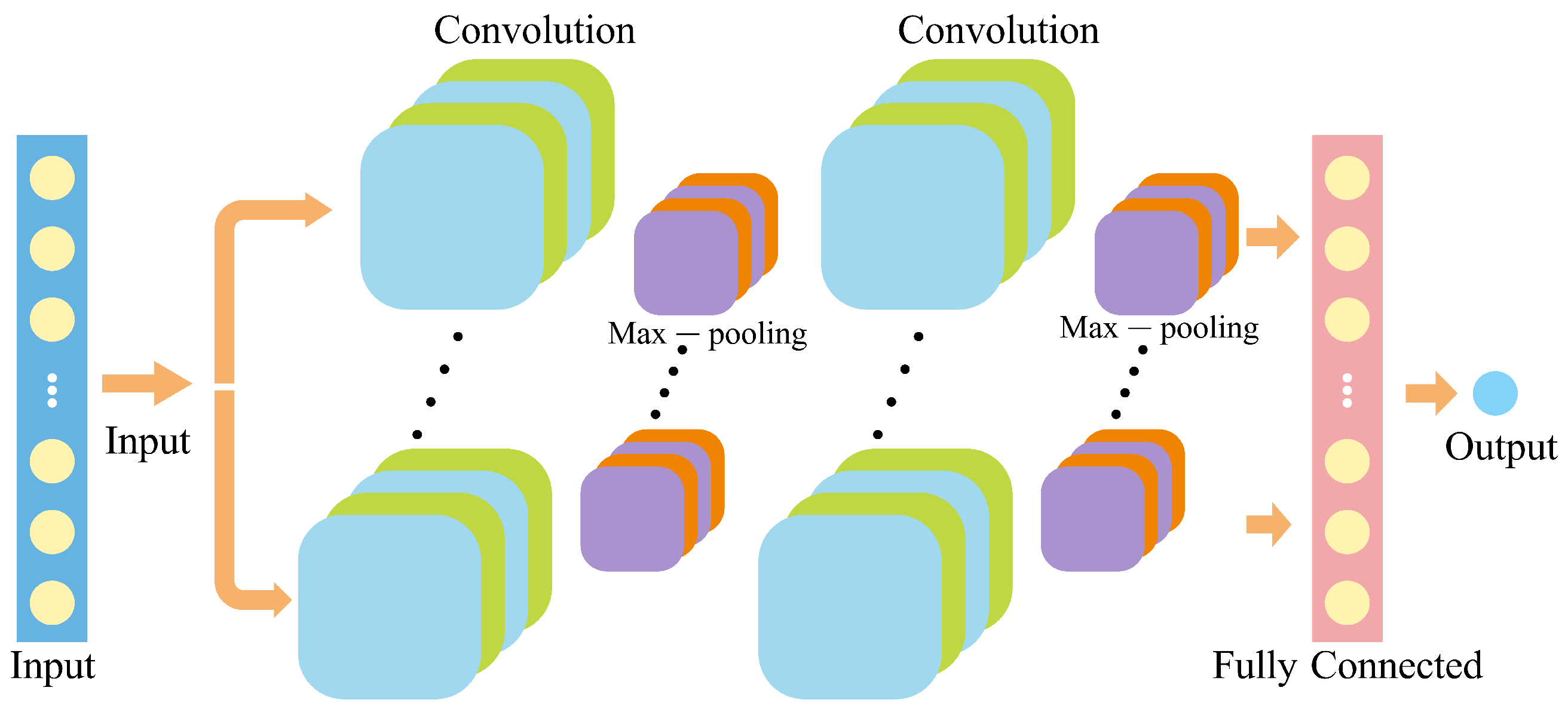

- Convolutional neural networks (CNN)

- (2)

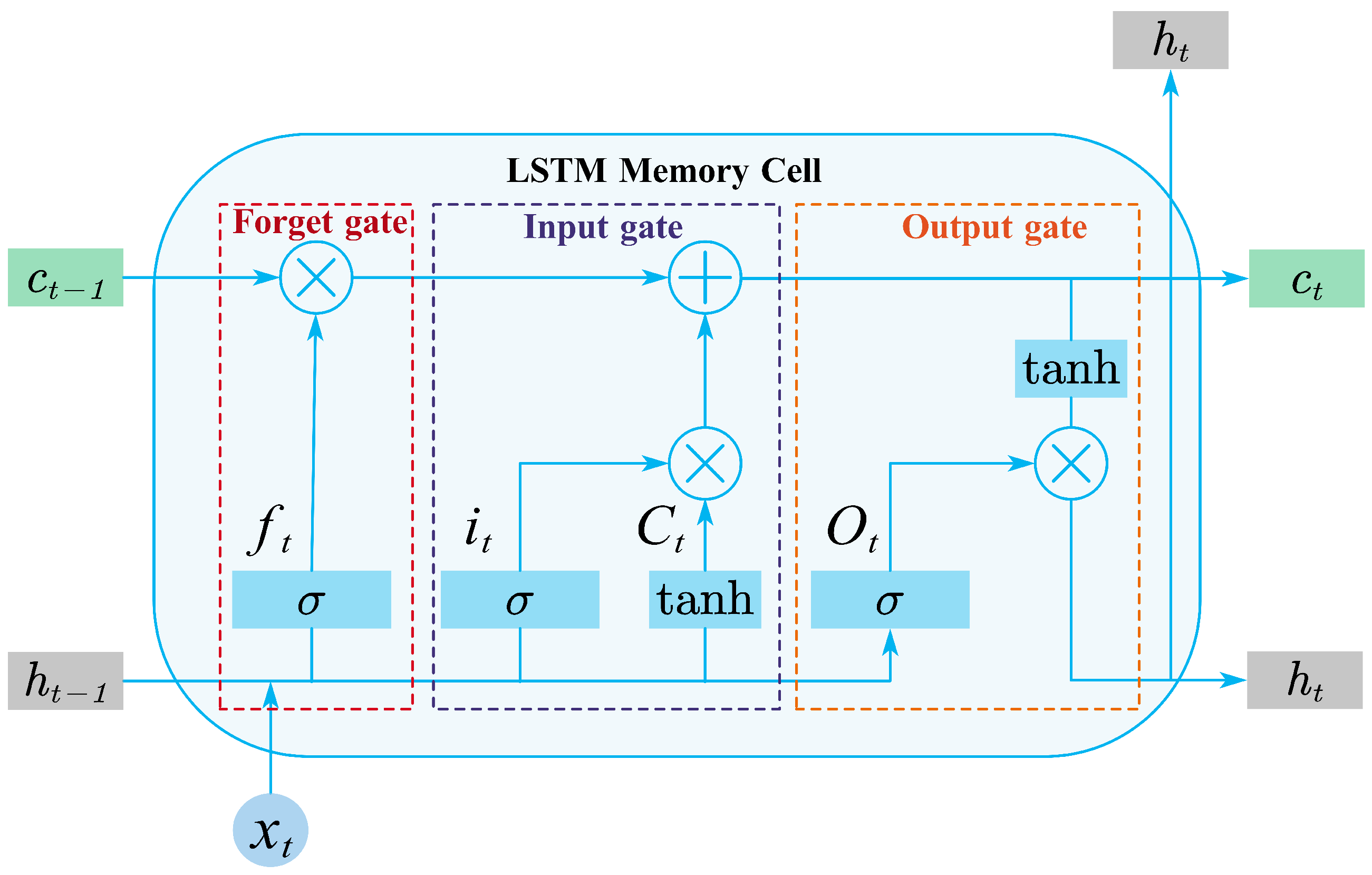

- Long short-term memory networks (LSTM)

- (3)

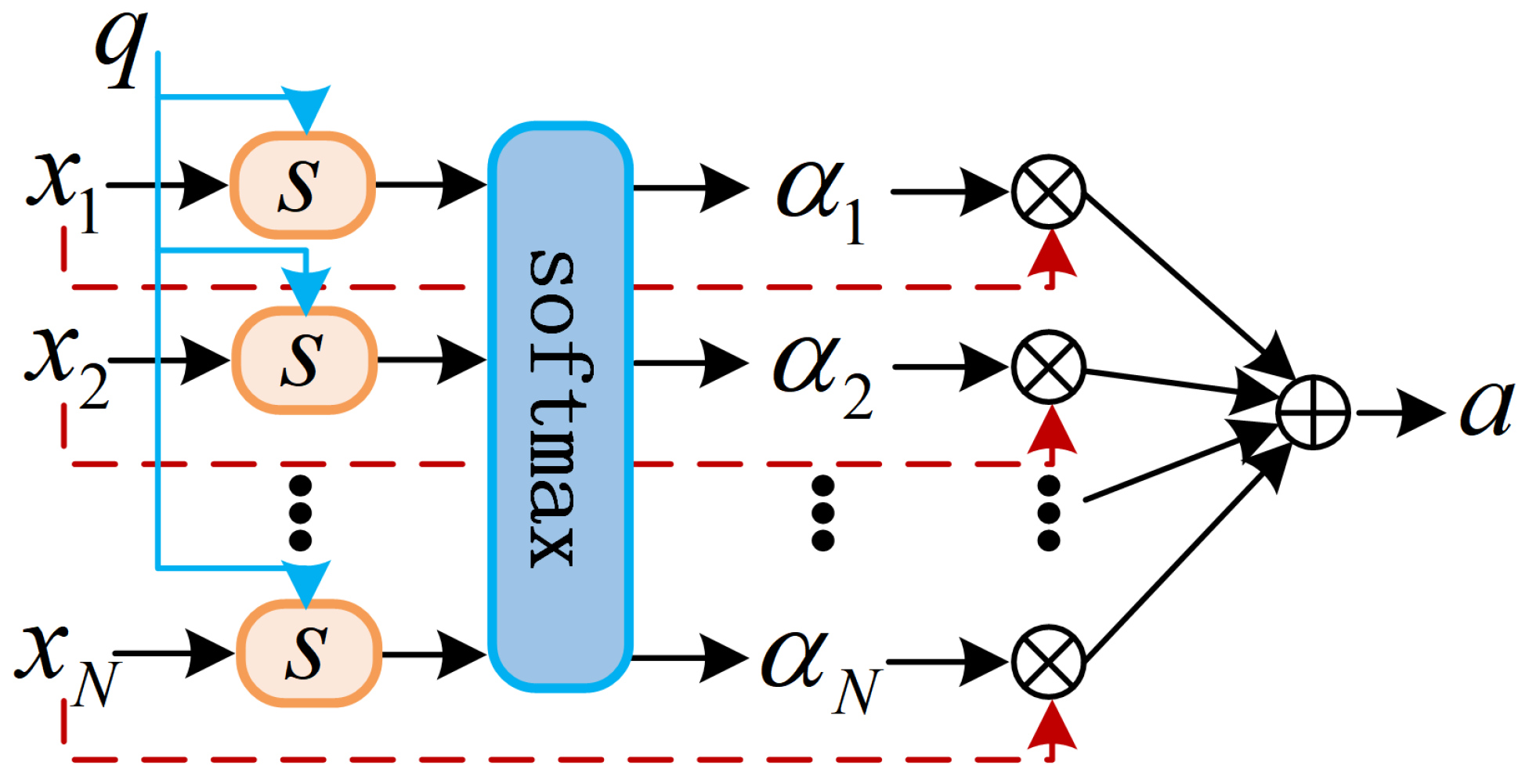

- Attention mechanism

3.2. Multivariate Input Fusion

3.3. Spatial Downscaling Module

3.4. Day-Ahead Forecasting Modeling Framework

4. Case Study

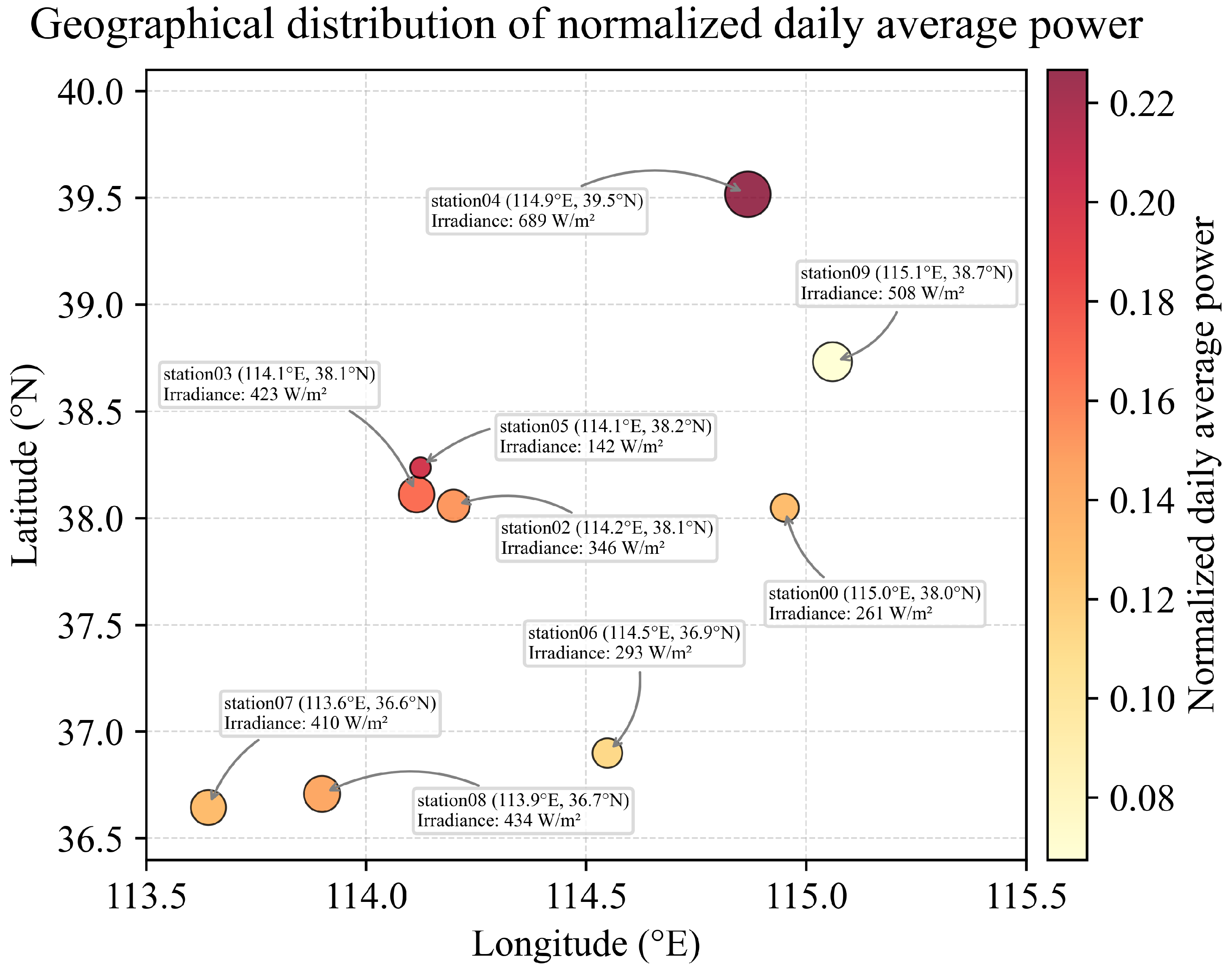

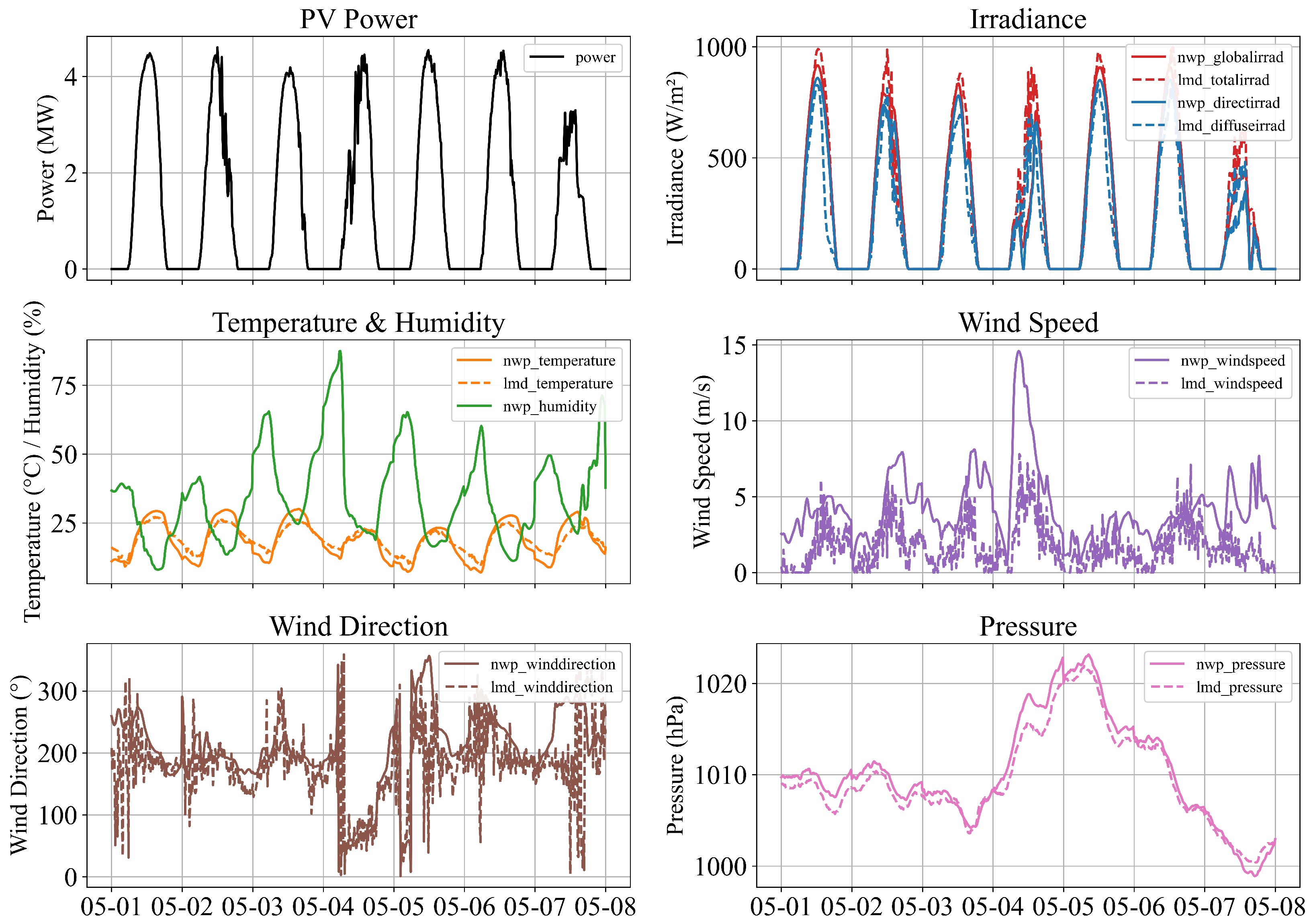

4.1. Experimental Data

4.2. Performance Indices

- (1)

- Root mean square error (RMSE)

- (2)

- Mean absolute error (MAE)

- (3)

- Pearson correlation coefficient (r)

- (4)

- Accuracy (CR)

4.3. Experimental Design

- (1)

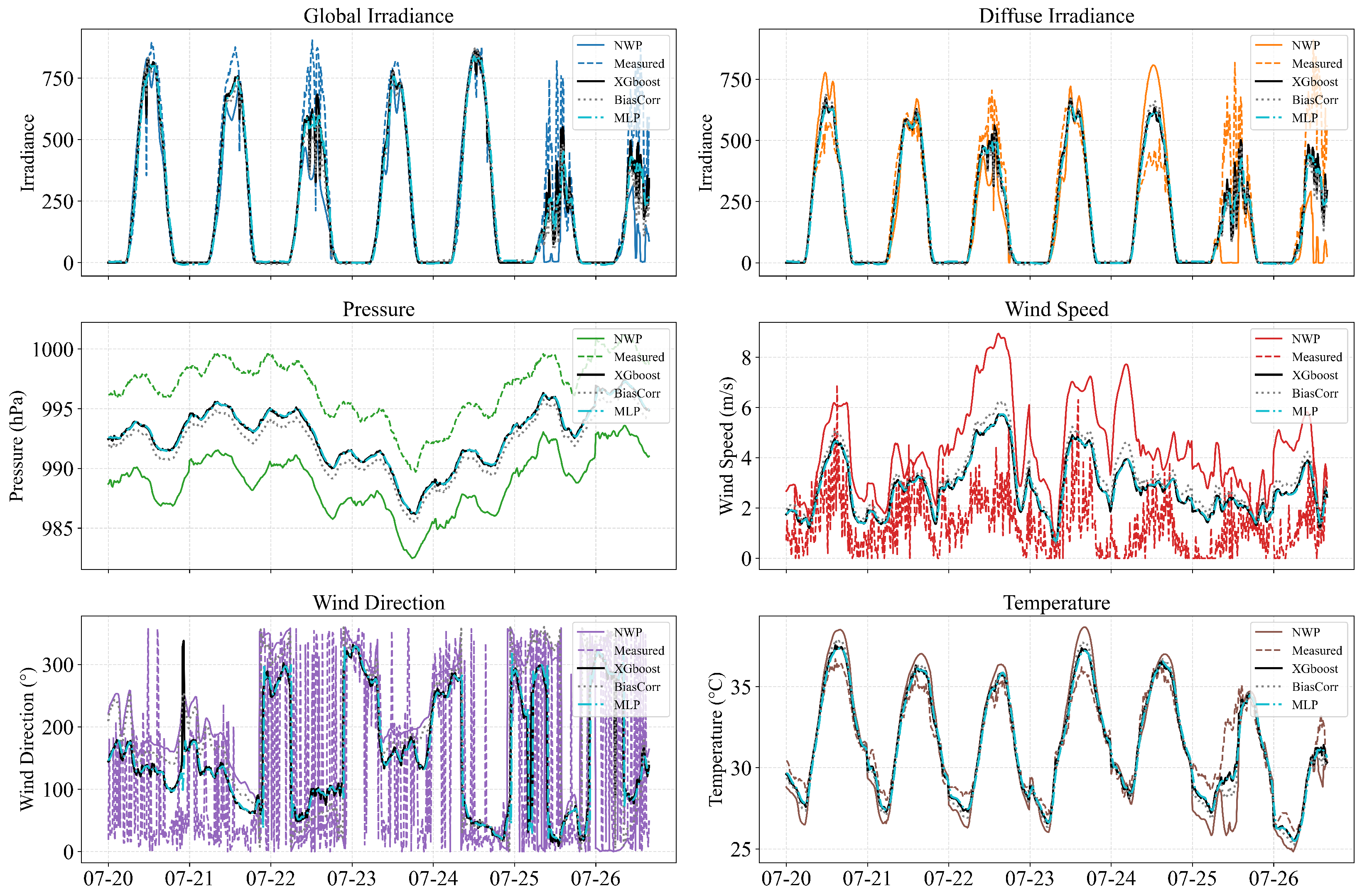

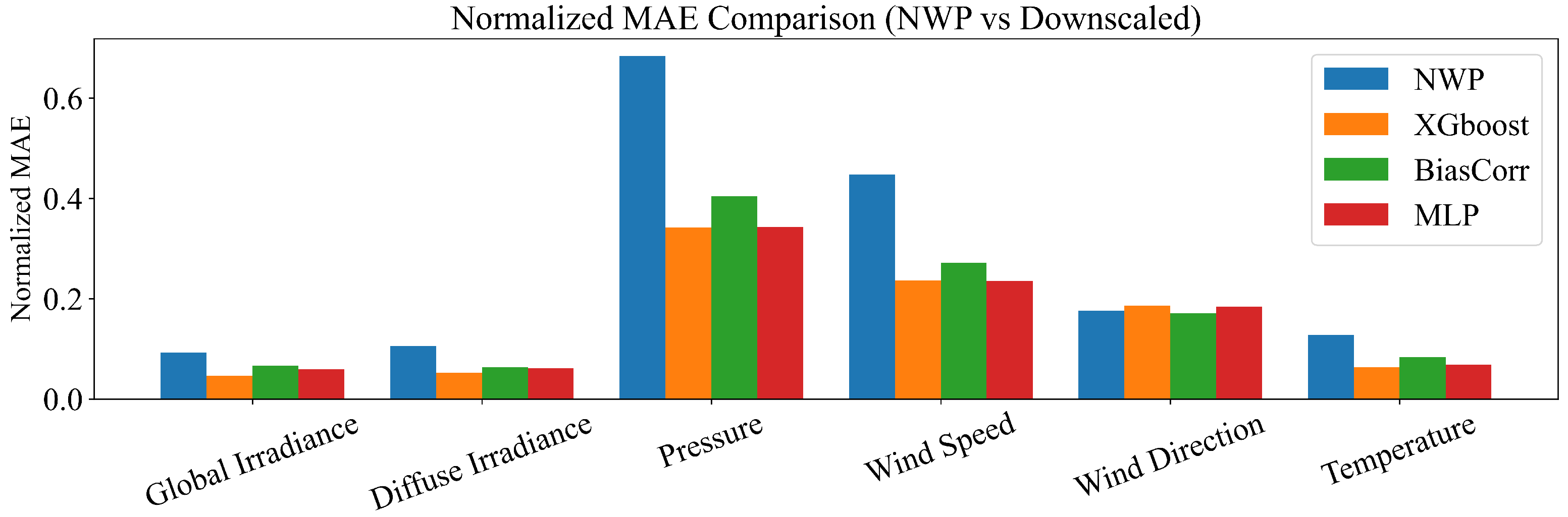

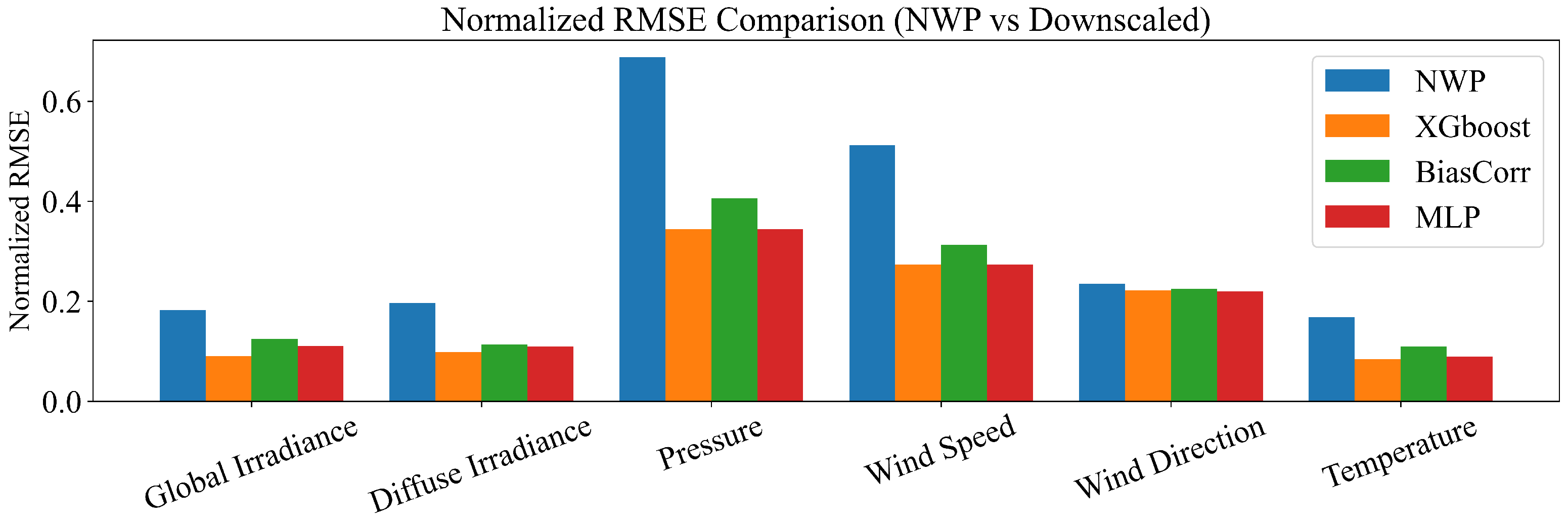

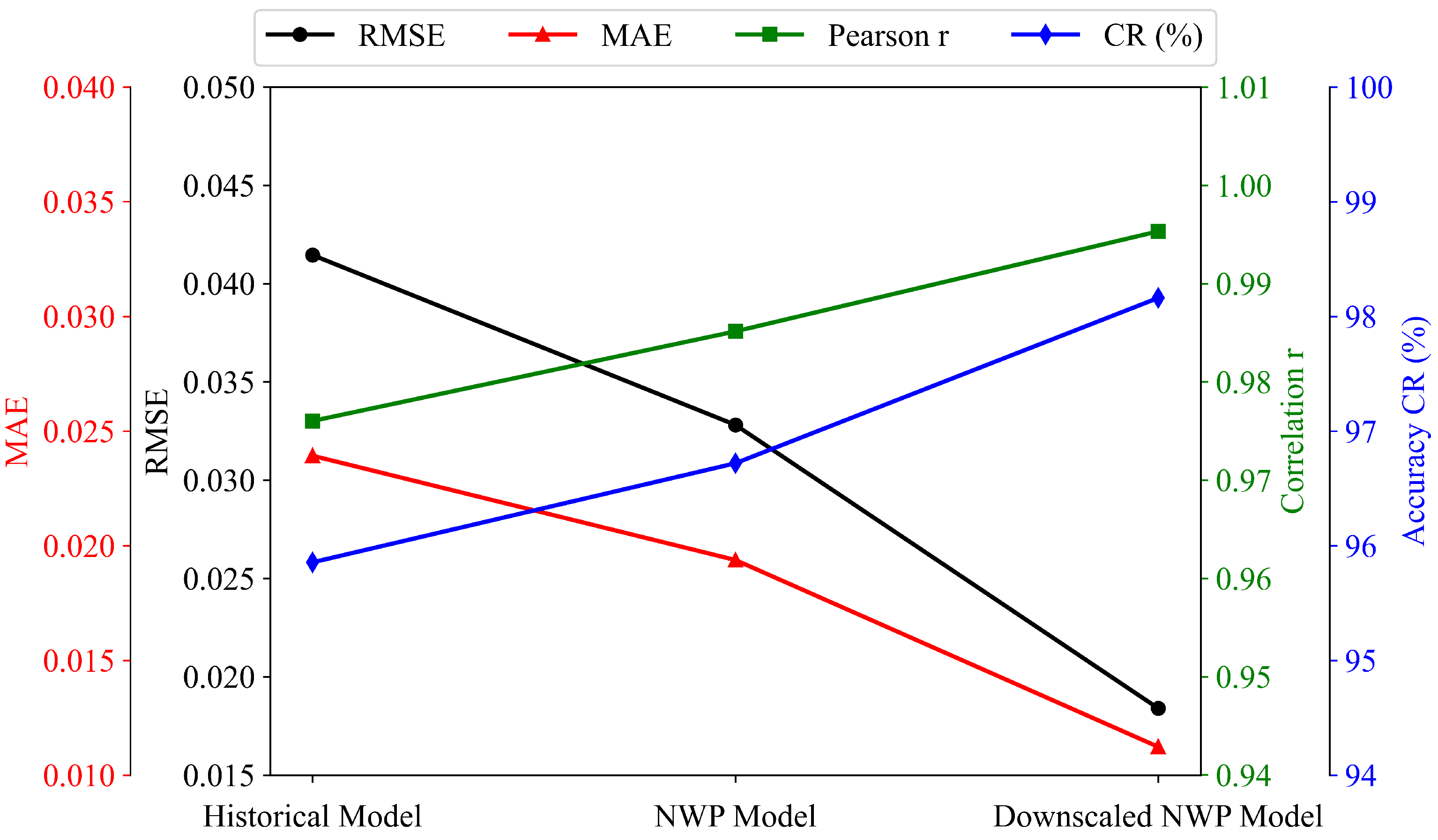

- Comparison of NWP errors before and after spatial downscaling

- (2)

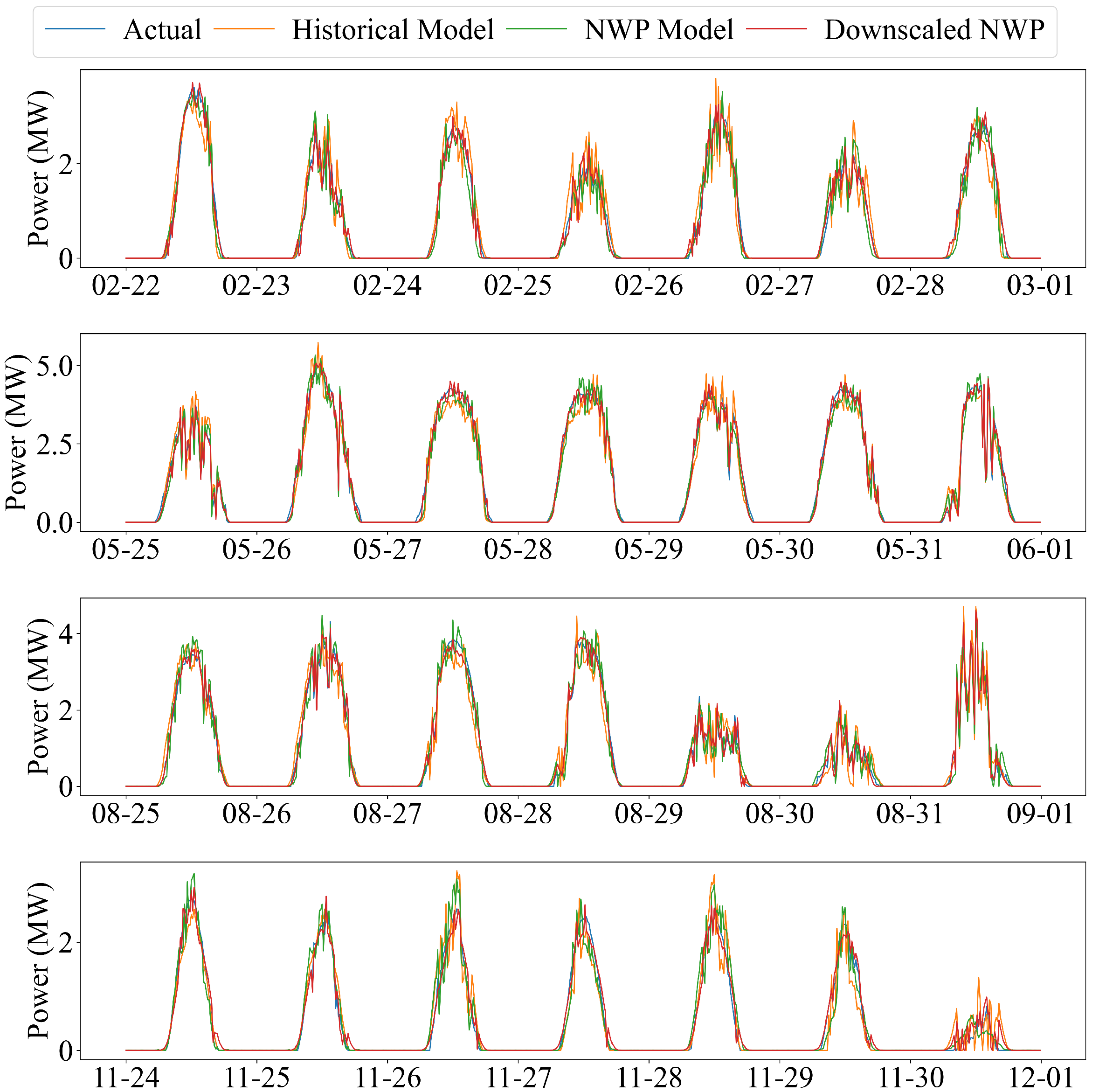

- Comparison of forecasting modes with different input features

- Historical power only: A univariate baseline model that uses only past PV power measurements.

- Historical power + original NWP: A multivariate forecasting model that incorporates raw NWP variables.

- Historical power + downscaled NWP: A forecasting model that uses high-resolution meteorological inputs generated by the spatial downscaling module.

- (3)

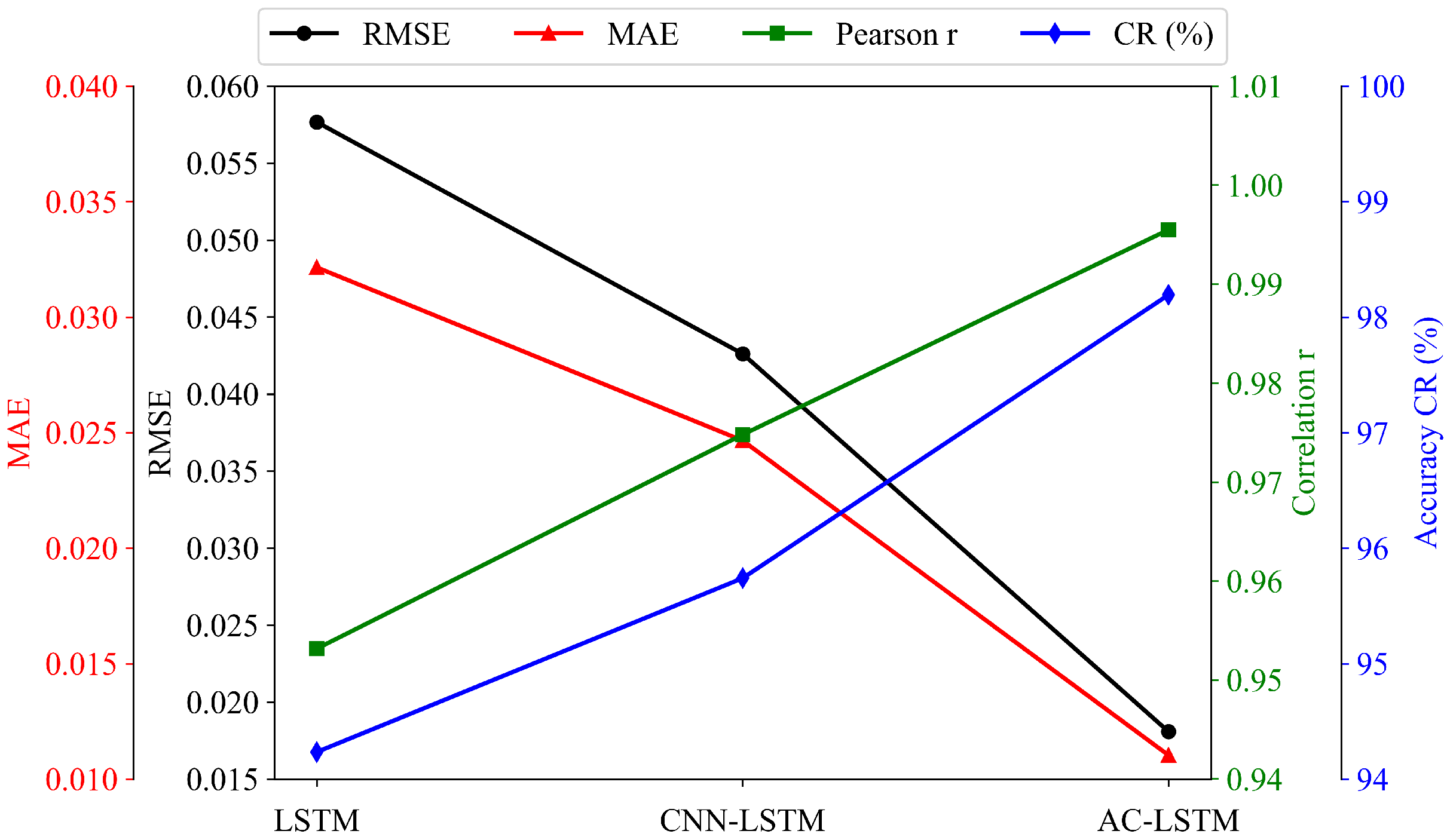

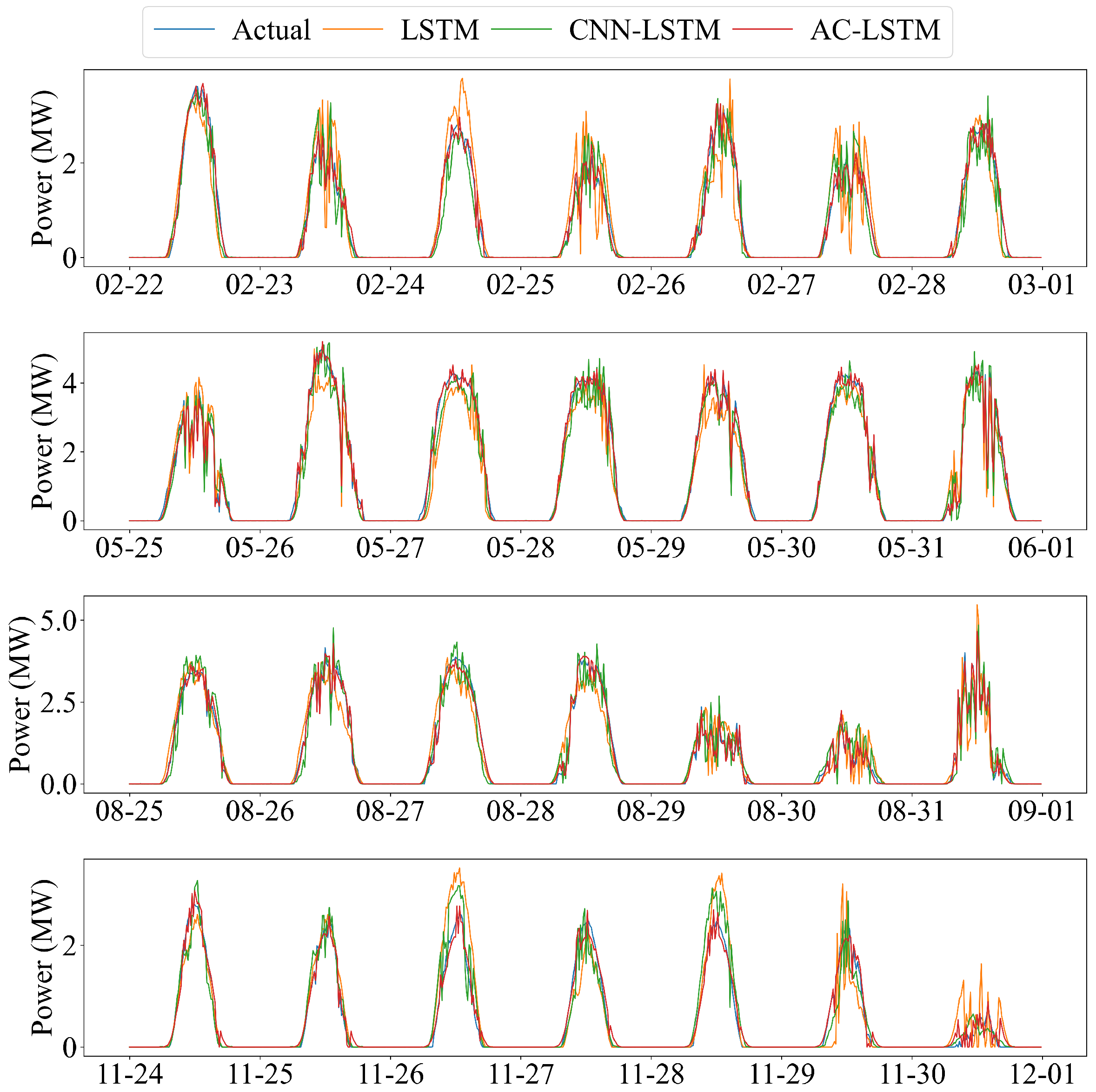

- Comparison of forecasting model architectures

- LSTM;

- CNN–LSTM;

- CNN–LSTM–Attention (proposed).

- (4)

- Unified evaluation protocol

5. Result Analysis

5.1. Effectiveness of Spatial Downscaling

5.2. Comparison of Forecasting Modes with Different Input Features

5.3. Comparison of Forecasting Model Architectures

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, D. A review of solar forecasting, its dependence on atmospheric sciences and implications for grid integration: Towards carbon neutrality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Pinson, P.; Wang, Y.; Weron, R.; Yang, D.; Zareipour, H. Energy forecasting: A review and outlook. IEEE Open Access J. Power Energy 2020, 7, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagukguk, R.A.; Ramadhan, R.A.A.; Lee, H.-J. A review on deep learning models for forecasting time series data of solar irradiance and photovoltaic power. Energies 2020, 13, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T.; Guo, Y.F.; Yang, D.Z.; Zhang, Z.L.; Kleissl, J.; van der Meer, D.; Yang, G.M.; Hong, T.; Liu, B.; Huang, N.T.; et al. Economics of physics-based solar forecasting in power system day-ahead scheduling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawn, R.; Browell, J. A review of very short-term wind and solar power forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovics, D.; Mayer, M.J. Comparison of machine learning methods for photovoltaic power forecasting based on numerical weather prediction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeunović, J.; Schubnel, B.; Alet, P.-J.; Carrillo, R.E. Spatio-temporal graph neural networks for multi-site PV power forecasting. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Gróf, G. Extensive comparison of physical models for photovoltaic power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2021, 283, 116239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahidi, S.; Madhiarasan, M.; Al-Ghussain, L.; Abubaker, A.M.; Ahmad, A.D.; Alrbai, M.; Aghaei, M.; Alahmer, H.; Alahmer, A.; Baraldi, P.; et al. Forecasting solar photovoltaic power production: A comprehensive review and innovative data-driven modeling framework. Energies 2024, 17, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Singh, R. PV power forecasting based on data-driven models: A review. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 1733–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheanetu, K.J. Solar photovoltaic power forecasting: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellit, A.; Pavan, A.M.; Lughi, V. Deep learning neural networks for short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, X. Combining transfer learning and constrained long short-term memory for power generation forecasting of newly-constructed photovoltaic plants. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 1062–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmas, E.; Spiliotis, E.; Stamatopoulos, E.; Marinakis, V.; Doukas, H. Short-term photovoltaic power forecasting using meta-learning and numerical weather prediction independent long short-term memory models. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 118997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wei, J.; Sun, G.; Muyeen, S.M.; Lin, S.; Li, F. A short-term probabilistic photovoltaic power prediction method based on feature selection and improved LSTM neural network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agga, A.; Abbou, A.; Labbadi, M.; El Houm, Y.; Ali, I.H.O. CNN-LSTM: An efficient hybrid deep learning architecture for predicting short-term photovoltaic power production. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 208, 107908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. A hybrid convolutional–long short-term memory–attention framework for short-term photovoltaic power forecasting, incorporating data from neighboring stations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, S.; Chu, Y.; Li, M.; Ding, Y.; Cui, R.; Zhao, X. Self-attention mechanism to enhance the generalizability of data-driven time-series prediction: A case study of intra-hour power forecasting of urban distributed photovoltaic systems. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 124007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Hussain, T.; Baik, S.W. Dual stream network with attention mechanism for photovoltaic power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2023, 338, 120916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Niu, D.; Wang, K.; Du, R.; Yu, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, F. Short-term photovoltaic power point-interval forecasting based on double-layer decomposition and WOA-BiLSTM-Attention and considering weather classification. Energy 2023, 275, 127348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Zhao, J.; Tao, Y.; Qi, Q.; Tian, Y. Operational day-ahead photovoltaic power forecasting based on transformer variant. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Jiao, X.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; Yao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Ding, S. A novel multi-step ahead solar power prediction scheme by deep learning on transformer structure. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, G.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, G.; Tang, J. CGAformer: Multi-scale feature transformer with MLP architecture for short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. Energy 2024, 312, 133495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeunović, J.; Schubnel, B.; Alet, P.-J.; Carrillo, R.E.; Frossard, P. Interpretable temporal-spatial graph attention network for multi-site PV power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2022, 327, 120127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, S.; Zheng, J. DEST-GNN: A double-explored spatio-temporal graph neural network for multi-site intra-hour PV power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yang, D.; Galanis, G.; Androulakis, E. Solar forecasting with hourly updated numerical weather prediction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhmi, O.; Tahrani, B.H.; Anani, N. A review of solar forecasting techniques and the role of artificial intelligence. Solar 2024, 4, 99–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J. Benefits of physical and machine learning hybridization for photovoltaic power forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharides, S.; Makrides, G.; Livera, A.; Theristis, M.; Kaimakis, P.; Georghiou, G.E. Day-ahead photovoltaic power production forecasting methodology based on machine learning and statistical post-processing. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 115023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagli, G.M.; Yang, D.; Srinivasan, D. Ensemble solar forecasting and post-processing using dropout neural network and information from neighboring satellite pixels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 155, 111909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; van der Meer, J. Post-processing in solar forecasting: Ten overarching thinking tools. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buster, G.; Rossol, M.; Maclaurin, G.; Xie, Y.; Sengupta, M. A physical downscaling algorithm for the generation of high-resolution spatiotemporal solar irradiance data. Sol. Energy 2021, 216, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, S.T.; Dinku, T.; Akurugu, B.A. Spatiotemporal downscaling model for solar irradiance forecasting using neighborhood component feature selection and neural networks. Energies 2025, 18, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, L.; Dong, M.; Li, J.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, W. Deep learning downscaled high-resolution daily near-surface meteorology over East Asia. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; Li, L.; Bian, D.; Bian, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S. Photovoltaic power prediction based on multi-scale photovoltaic power fluctuation characteristics and multi-channel LSTM prediction models. Renew. Energy 2025, 246, 122866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Yang, D.; Szintai, B. Comparing global and regional downscaled NWP models for irradiance and photovoltaic power forecasting: ECMWF versus AROME. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Canhoto, P.; Salgado, R. Development and assessment of artificial neural network models for direct normal solar irradiance forecasting using operational numerical weather prediction data. Energy AI 2024, 15, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiani, A.; Ishizaki, N.N.; Watanabe, T.; Tamaki, Y.; Cordero, R.R.; Feron, S.; Irie, H. Spatially generalizable bias correction of satellite solar radiation for regional climate assessment—A case study in Japan. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 145, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Yang, D. Optimal place to apply post-processing in the deterministic photovoltaic power forecasting workflow. Appl. Energy 2024, 371, 123681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Yang, D. Pairing ensemble numerical weather prediction with ensemble physical model chain for probabilistic photovoltaic power forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 175, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, S.; Chu, Y.; Li, M.; Ding, Y.; Cui, R.; Zhao, X. Deep learning models for photovoltaic power forecasting: A review. Energies 2024, 17, 3973. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, S.; Xi, X.; Su, D.; Han, Z.; Wang, D. Spatio-temporal photovoltaic power prediction with Fourier graph neural network. Electronics 2024, 13, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraftabzadeh, S.M.; Colombo, C.G.; Longo, M.; Foiadelli, F. A day-ahead photovoltaic power prediction via transfer learning and deep neural networks. Forecasting 2023, 5, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascencio-Vásquez, J.; Bevc, J.; Reba, K.; Brecl, K.; Jankovec, M.; Topič, M. Advanced PV performance modelling based on different levels of irradiance data accuracy. Energies 2020, 13, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Peng, J.; Luo, Y.; Shen, Z.; Yang, H. Comparison of different simplistic prediction models for forecasting PV power output: Assessment with experimental measurements. Energy 2021, 224, 120162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharkan, H.; Habib, S.; Islam, M. Solar power prediction using dual stream CNN-LSTM architecture. Sensors 2023, 23, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, Q.; Tai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Liu, W. Time series forecasting for hourly photovoltaic power using conditional generative adversarial network and Bi-LSTM. Energy 2022, 246, 123403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Qian, Z.; Pei, Y. Day-ahead hourly photovoltaic power forecasting using attention-based CNN–LSTM neural network embedded with multiple relevant and target variables prediction pattern. Energy 2021, 232, 120996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Bell, M. Enabling Smart Grid Resilience with Deep Learning-Based Battery Health Prediction in EV Fleets. Batteries 2025, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.; Behera, H.S. A study on leading machine learning techniques for high order fuzzy time series forecasting. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 87, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannitsem, S.; Bremnes, J.B.; Demaeyer, J.; Evans, G.R.; Flowerdew, J.; Hemri, S.; Lerch, S.; Roberts, N.; Theis, S.E.; Atencia, A.; et al. Statistical postprocessing for weather forecasts: Review, challenges, and avenues in a big data world. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, E681–E699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böök, H.; Lindfors, A.V. Site-specific adjustment of a NWP-based photovoltaic production forecast. Sol. Energy 2020, 211, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.A.; Ahmed, A.N.; Chow, M.F.; Huang, Y.F.; El-Shafie, A. Extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model to predict the groundwater levels in Selangor, Malaysia. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, P.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Chi, X.; Shi, M. PVOD v1.0: A Photovoltaic Power Output Dataset (V4). Science Data Bank. 2021. Available online: https://cstr.cn/31253.11.sciencedb.01094 (accessed on 12 January 2026).

| Category | Variables | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| NWP predictors | nwp_globalirrad | Forecasted global irradiance | W/ |

| nwp_directirrad | Forecasted direct irradiance | W/ | |

| nwp_temperature | Forecasted ambient temperature | ∘C | |

| nwp_humidity | Forecasted relative humidity | % | |

| nwp_windspeed | Forecasted wind speed | m/s | |

| nwp_winddirection | Forecasted wind direction | ∘ | |

| nwp_pressure | Forecasted atmospheric pressure | hPa | |

| On-site observations | lmd_totalirrad | Measured total irradiance | W/ |

| lmd_diffuseirrad | Measured diffuse irradiance | W/ | |

| lmd_temperature | Measured ambient temperature | ∘C | |

| lmd_pressure | Measured atmospheric pressure | hPa | |

| lmd_winddirection | Measured wind direction | ∘ | |

| lmd_windspeed | Measured wind speed | m/s | |

| Historical PV output | power | Actual PV power, used as an autoregressive input | MW |

| Method | RMSE | MAE | Pearson r | CR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical power | 0.0414 | 0.0239 | 0.976 | 95.8 |

| Raw NWP | 0.0328 | 0.0194 | 0.985 | 96.7 |

| Downscaled NWP | 0.0184 | 0.0112 | 0.995 | 98.1 |

| Method | RMSE | MAE | Pearson r | CR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 0.0577 | 0.0321 | 0.953 | 94.2 |

| CNN-LSTM | 0.0426 | 0.0247 | 0.974 | 95.7 |

| AC-LSTM | 0.0181 | 0.0111 | 0.995 | 98.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, F.; Tang, X.; Xiao, M. Attention-Enhanced CNN-LSTM with Spatial Downscaling for Day-Ahead Photovoltaic Power Forecasting. Sensors 2026, 26, 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020593

Peng F, Tang X, Xiao M. Attention-Enhanced CNN-LSTM with Spatial Downscaling for Day-Ahead Photovoltaic Power Forecasting. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):593. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020593

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Feiyu, Xiafei Tang, and Maner Xiao. 2026. "Attention-Enhanced CNN-LSTM with Spatial Downscaling for Day-Ahead Photovoltaic Power Forecasting" Sensors 26, no. 2: 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020593

APA StylePeng, F., Tang, X., & Xiao, M. (2026). Attention-Enhanced CNN-LSTM with Spatial Downscaling for Day-Ahead Photovoltaic Power Forecasting. Sensors, 26(2), 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020593