Multi-Level Perception Systems in Fusion of Lifeforms: Classification, Challenges and Future Conceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

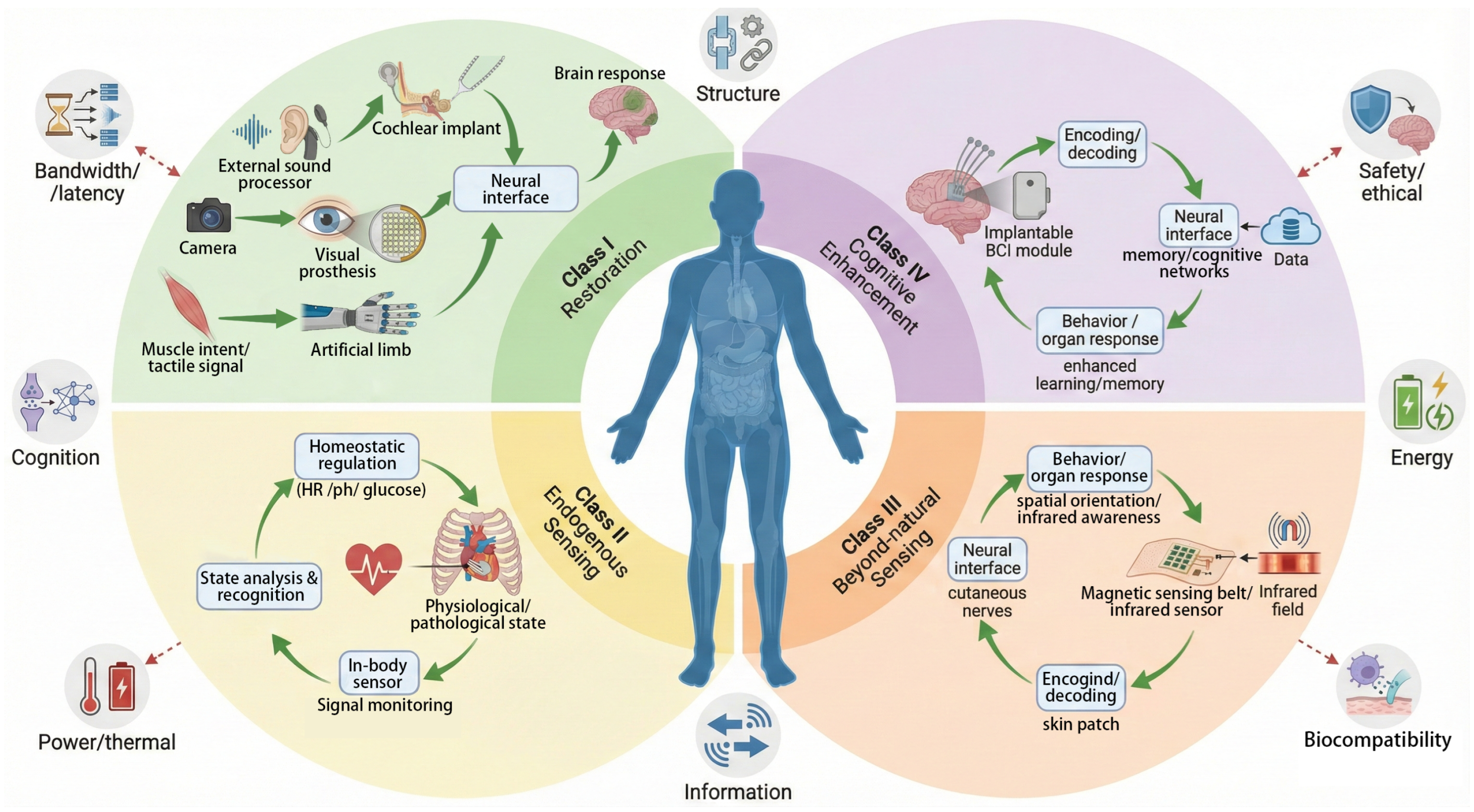

2. Definition and System Characteristics of Fusion of Lifeforms

Determining the Primary Functional Intent

3. Functional Classification of Sensing Systems and Current Technologies

3.1. Sensory Restoration and Neural Fusion

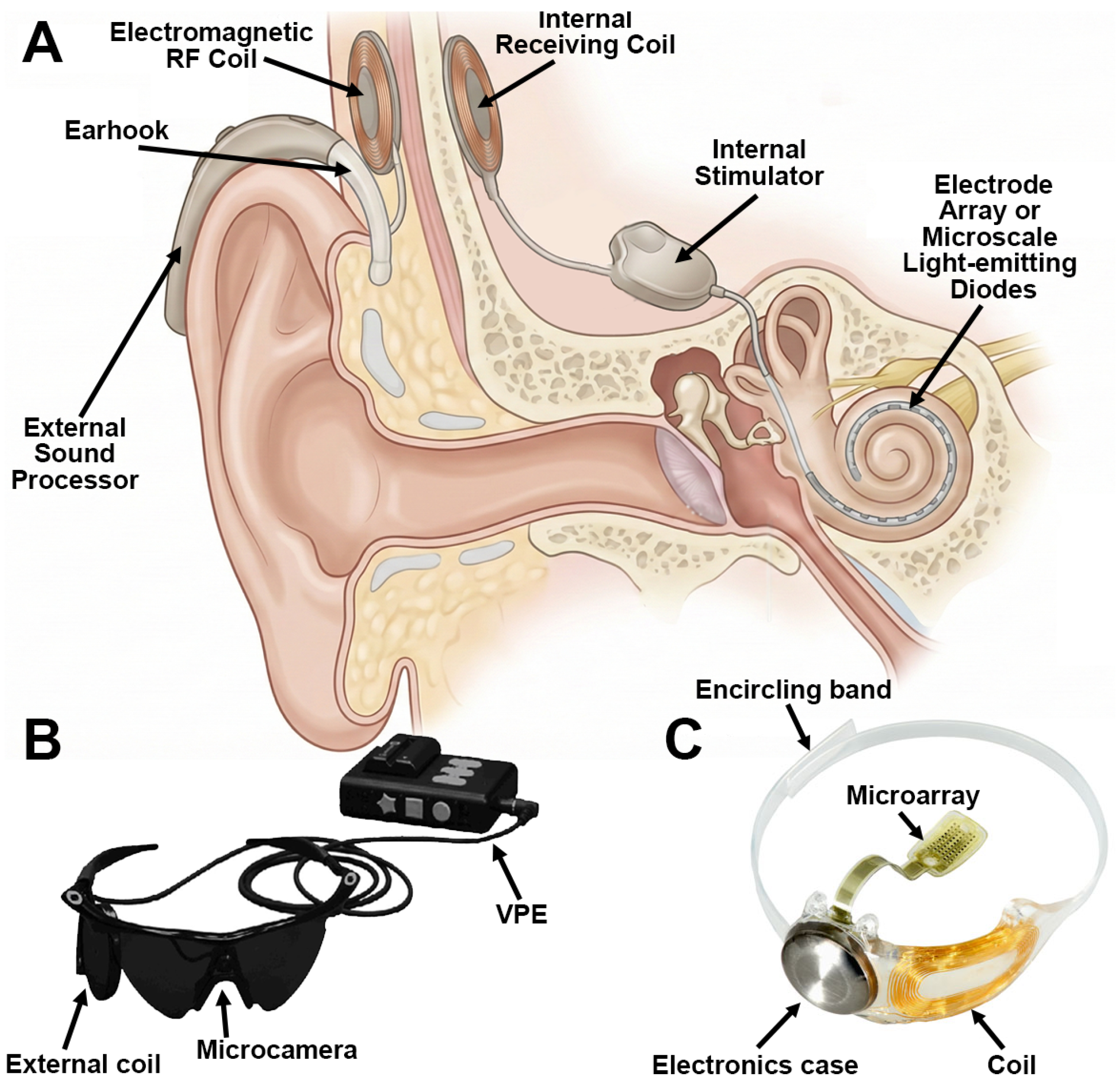

3.1.1. Auditory Restoration

3.1.2. Visual Restoration

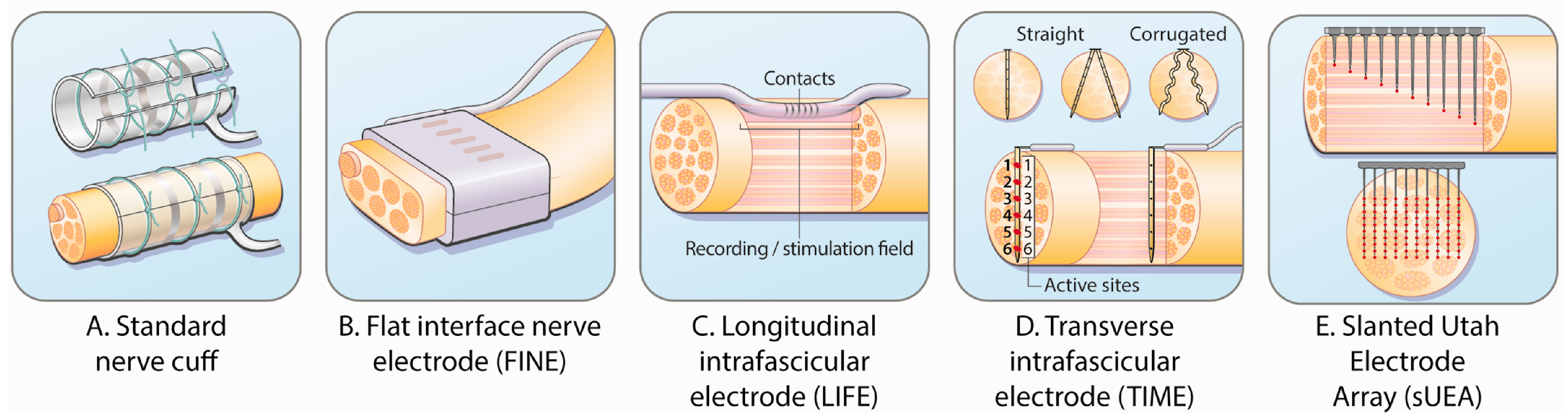

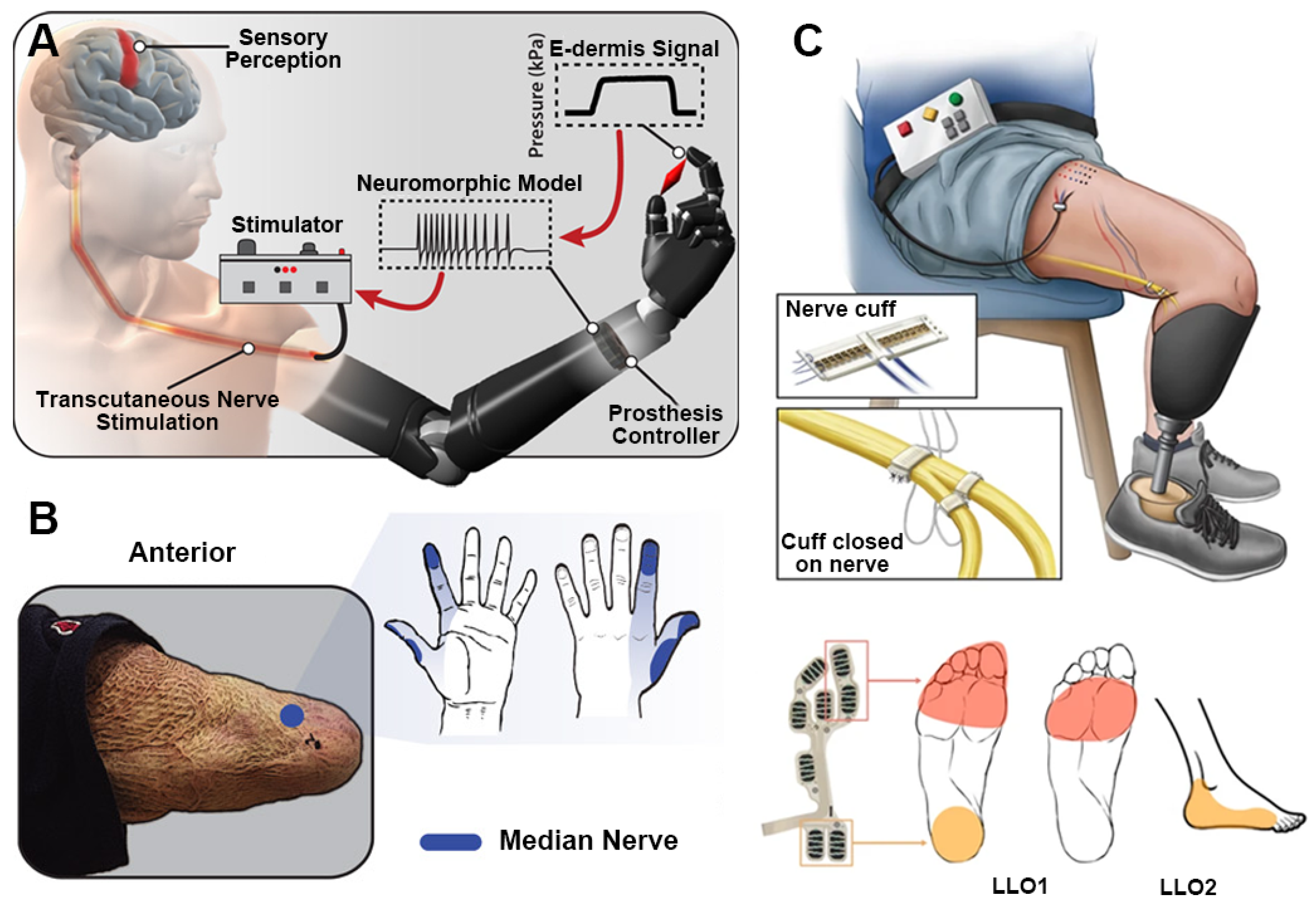

3.1.3. Tactile Restoration

3.1.4. Olfactory and Speech Restoration

3.1.5. Neuroprostheses and Perception–Action Closed Loops

3.1.6. Neural Coupling and Cognitive Interaction Interfaces

3.2. Endogenous Sensing and Physiological Closed-Loop Control

3.2.1. Vital Sign Sensing and Real-Time Regulation

3.2.2. Metabolic Process Sensing and Chemical Homeostasis

3.2.3. Neural Signal Decoding and Interaction Interfaces

3.2.4. Multimodal Sensing and System Integration

3.3. Suprasensory Augmentation and Channel Mapping

3.4. Cognitive Enhancement and Intelligent Integration

3.4.1. Cognitive Enhancement and Symbiotic Regulation

3.4.2. Memory Enhancement and Precision Intervention

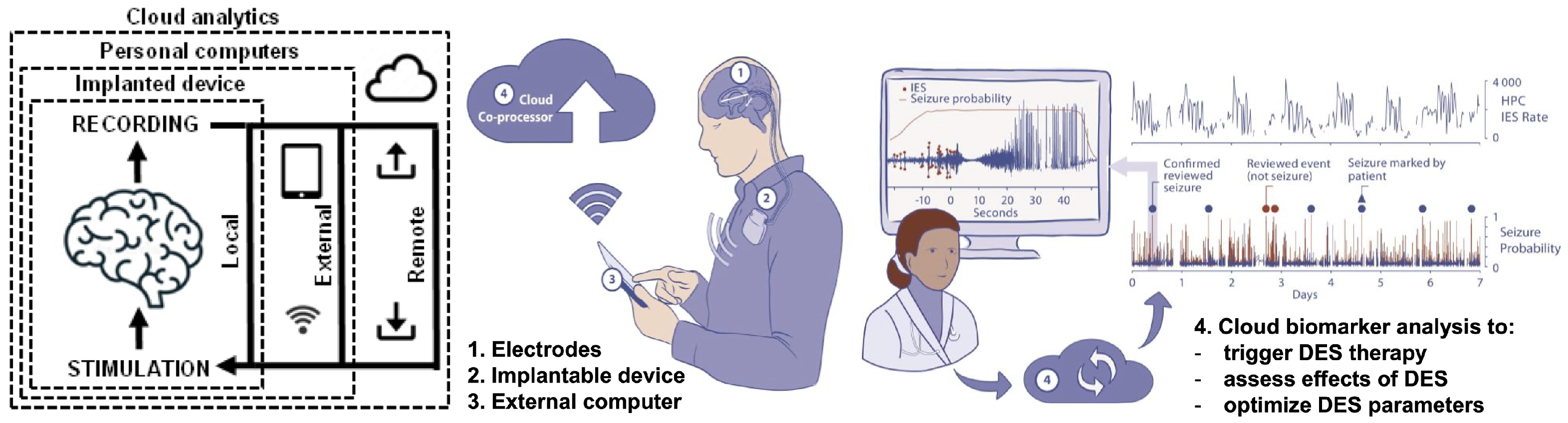

3.4.3. Cloud Intelligence and Cognitive Extension

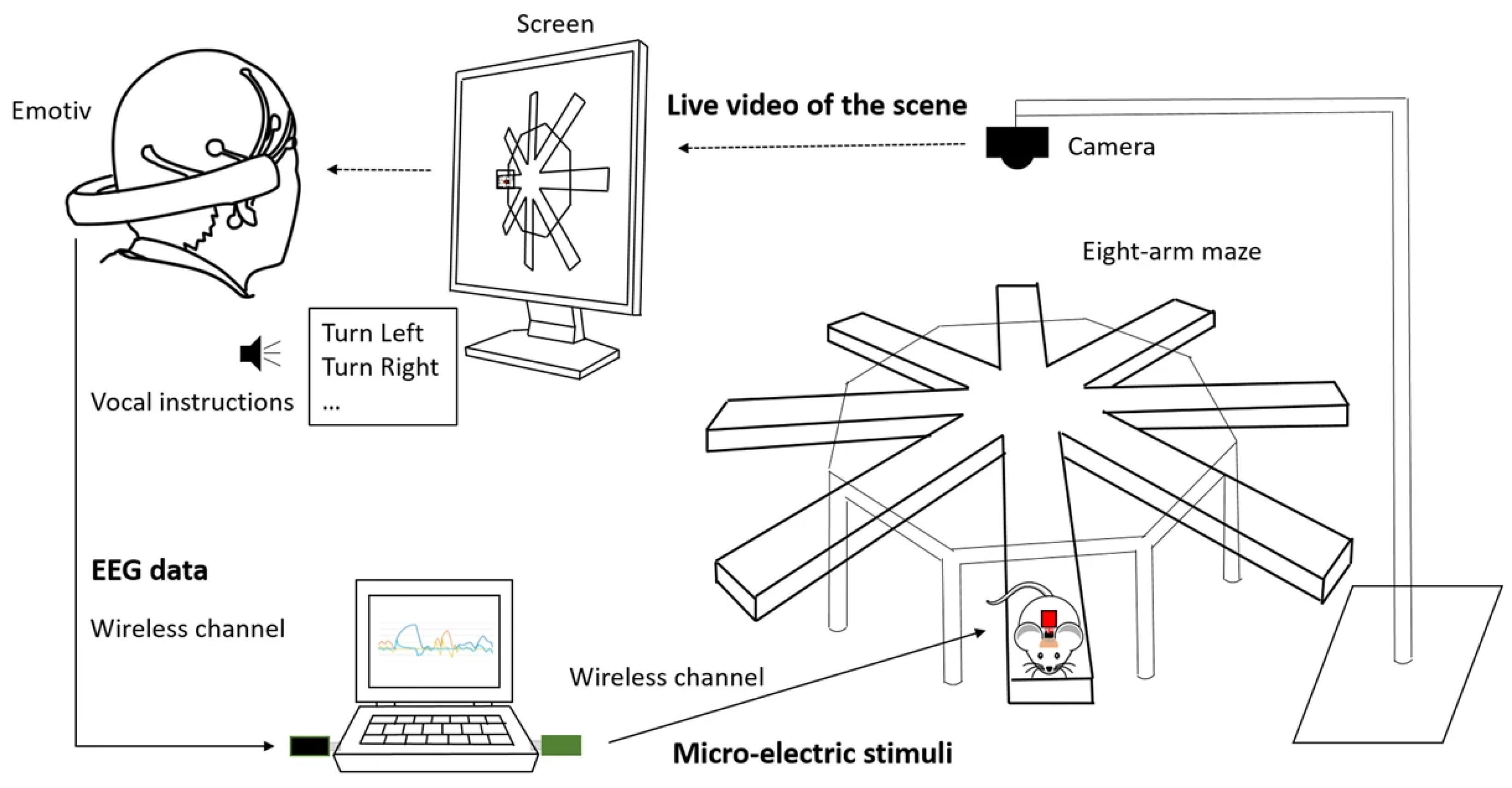

3.4.4. Inter-Brain Collaboration and Collective Intelligence

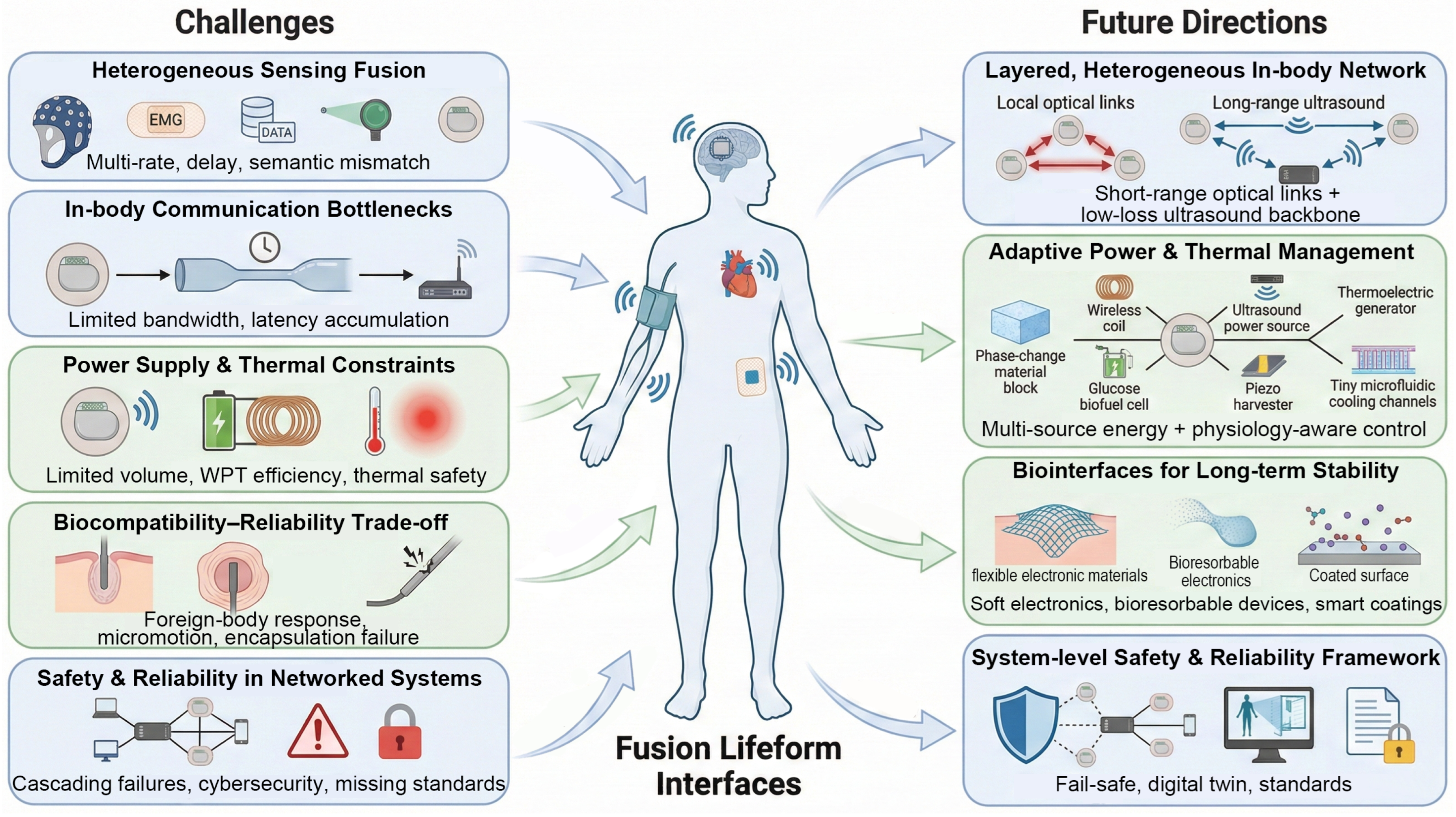

4. Interface Integration, System-Level Challenges, and Future Directions

4.1. Technical Challenges and Bottlenecks

4.1.1. Challenge 1: Complexity of Multi-Source Heterogeneous Sensing Fusion

4.1.2. Challenge 2: Bandwidth and Latency Limits of In-Body Information Transfer

4.1.3. Challenge 3: System-Level Power Supply and Thermal Management

4.1.4. Challenge 4: Tension Between Biocompatibility and Long-Term Reliability

4.1.5. Challenge 5: Safety and Reliability in Complex Fusion Systems

4.2. Future Directions

4.2.1. Building Layered, Heterogeneous In-Body Intelligent Communication Networks

4.2.2. Sustainable and Adaptive Power and Thermal-Management Strategies

4.2.3. Innovative Biointerfaces and Long-Lived Encapsulation Materials

4.2.4. Frameworks for System-Level Safety and Reliability

5. Safety and Ethical Considerations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGI | Artificial General Intelligence |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| B2BI | Brain-to-Brain Interfaces |

| BBIs | Brain-to-Brain Interfaces |

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interfaces |

| CBIs | Computer–Brain Interfaces |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| DBS | Deep Brain Stimulation |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| eBCIs | Enhanced Brain–Computer Interfaces |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| e-nose | Electronic Nose |

| FNIRs | Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| FUS | Focused Ultrasound |

| ICMS | Intracortical Microstimulation |

| iBCIs | Implantable Brain–Computer Interfaces |

| iEEG | Intracranial Electroencephalography |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Units |

| IoB | Internet of Bodies |

| MIMO | Multi-Input–Multi-Output |

| NSTENG | Nano-Structured Triboelectric Nanogenerator |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| SEPS | Subendocardial Pressure Sensors |

| SSVEP | Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials |

| TENGs | Triboelectric Nanogenerators |

| TENS | Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation |

| TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| WIBSNs | Wearable–Implantable Body Sensor Networks |

References

- Huang, H.H.; Hargrove, L.J.; Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Sensinger, J.W. Integrating Upper-Limb Prostheses with the Human Body: Technology Advances, Readiness, and Roles in Human–Prosthesis Interaction. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 26, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alam, F.; Ashfaq Ahmed, M.; Jalal, A.H.; Siddiquee, I.; Adury, R.Z.; Hossain, G.M.M.; Pala, N. Recent Progress and Challenges of Implantable Biodegradable Biosensors. Micromachines 2024, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapeaux, A.B.; Constandinou, T.G. Implantable brain machine interfaces: First-in-human studies, technology challenges and trends. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 72, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semertzidis, N.; Zambetta, F.; Mueller, F.F. Brain-Computer Integration: A Framework for the Design of Brain-Computer Interfaces from an Integrations Perspective. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2023, 30, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, G. Brain–computer symbiosis. J. Neural Eng. 2008, 5, P1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Vardalakis, N.; Wagner, F.B. Neuroprosthetics: From sensorimotor to cognitive disorders. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, F.; O’Regan, J.K. Sensory augmentation: Integration of an auditory compass signal into human perception of space. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhai, L.; Fang, Y.; Huang, J. Neuralite: Enabling wireless high-resolution brain-computer interfaces. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, ACM MobiCom ’24, Washington, DC, USA, 18–22 November 2024; pp. 984–999. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.N.; Ge, S.; Yang, N.N.; Xu, J.J.; Han, H.B.; Xu, S.Y. Artificial vision-aid systems: Current status and future trend. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 48, 1316–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh, Z.; Brooks, P.J.; Barzilay, O.; Fine, N.; Glogauer, M. Macrophages, foreign body giant cells and their response to implantable biomaterials. Materials 2015, 8, 5671–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, M.R.; Wong, V.W.; Nelson, E.R.; Longaker, M.T.; Gurtner, G.C. The foreign body response: At the interface of surgery and bioengineering. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.M.; Khan, S.; Khalifa, O.O. Wireless transfer of power to low power implanted biomedical devices: Coil design considerations. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference Proceedings, Graz, Austria, 13–16 May 2012; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, M.; Biswas, D.; Le, T.; Hyde, J.; Mahbub, I.; Chang, L.; Hao, Y. Design of a flexible receiver module for implantable wireless power transfer (WPT) applications. In Proceedings of the 2019 United States National Committee of URSI National Radio Science Meeting (USNC-URSI NRSM), Boulder, CO, USA, 9–12 January 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Nirenberg, S.; Pandarinath, C. Retinal prosthetic strategy with the capacity to restore normal vision. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15012–15017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabot, G.A.; Dammann, J.F.; Berg, J.A.; Tenore, F.V.; Boback, J.L.; Vogelstein, R.J.; Bensmaia, S.J. Restoring the sense of touch with a prosthetic hand through a brain interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18279–18284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kral, A.; Sharma, A. Developmental neuroplasticity after cochlear implantation. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caravaca-Rodriguez, D.; Gaytan, S.P.; Suaning, G.J.; Barriga-Rivera, A. Implications of Neural Plasticity in Retinal Prosthesis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Orsborn, A.L.; Moorman, H.G.; Overduin, S.A.; Shanechi, M.M.; Dimitrov, D.F.; Carmena, J.M. Closed-Loop Decoder Adaptation Shapes Neural Plasticity for Skillful Neuroprosthetic Control. Neuron 2014, 82, 1380–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.W. Optimizing Cochlear Implant Speech Performance. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. 2003, 112, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Uluşan, H.; Yüksel, M.B.; Topçu, Ö.; Yiğit, H.A.; Yılmaz, A.M.; Doğan, M.; Gülhan Yasar, N.; Kuyumcu, İ.; Batu, A.; Göksu, N.; et al. A full-custom fully implantable cochlear implant system validated in vivo with an animal model. Commun. Eng. 2024, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjigin, A.; Kokkinakis, K.; Bharadwaj, H.M.; Stohl, J.S. Deep learning restores speech intelligibility in multi-talker interference for cochlear implant users. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, L.; Dorn, J.D.; Humayun, M.S.; Dagnelie, G.; Handa, J.; Barale, P.O.; Sahel, J.A.; Stanga, P.E.; Hafezi, F.; Safran, A.B.; et al. Five-Year Safety and Performance Results from the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis System Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2248–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorach, H.; Goetz, G.; Smith, R.; Lei, X.; Mandel, Y.; Kamins, T.; Mathieson, K.; Huie, P.; Harris, J.; Sher, A.; et al. Photovoltaic restoration of sight with high visual acuity. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, F.R.; Kunz, E.M.; Fan, C.; Avansino, D.T.; Wilson, G.H.; Choi, E.Y.; Kamdar, F.; Glasser, M.F.; Hochberg, L.R.; Druckmann, S.; et al. A high-performance speech neuroprosthesis. Nature 2023, 620, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, L.E.; Dragomir, A.; Betthauser, J.L.; Hunt, C.L.; Nguyen, H.H.; Kaliki, R.R.; Thakor, N.V. Prosthesis with neuromorphic multilayered e-dermis perceives touch and pain. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaat3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.A.; Kluger, D.T.; Davis, T.S.; Wendelken, S.M.; Okorokova, E.V.; He, Q.; Duncan, C.C.; Hutchinson, D.T.; Thumser, Z.C.; Beckler, D.T.; et al. Biomimetic sensory feedback through peripheral nerve stimulation improves dexterous use of a bionic hand. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaax2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, E.H.; Puram, S.V.; See, R.B.; Tripp, A.G.; Nair, D.G. Induction of smell through transethmoid electrical stimulation of the olfactory bulb. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Shi, B.; Li, N.; Jiang, D.; Xie, F.; Qu, D.; Zou, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Transcatheter Self-Powered Ultrasensitive Endocardial Pressure Sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhuo, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Liu, L.; et al. Eco-friendly in-situ gap generation of no-spacer triboelectric nanogenerator for monitoring cardiovascular activities. Nano Energy 2021, 90, 106580. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, C.; Luo, D.; Chao, S.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J. Promoting maturation and contractile function of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes by self-powered implantable triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2022, 103, 107798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Kang, L.; Li, J.; Long, Y.; Wei, H.; Ferreira, C.A.; Jeffery, J.J.; Lin, Y.; Cai, W.; Wang, X. Effective weight control via an implanted self-powered vagus nerve stimulation device. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab Hassani, F.; Mogan, R.P.; Gammad, G.G.L.; Wang, H.; Yen, S.C.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C. Toward Self-Control Systems for Neurogenic Underactive Bladder: A Triboelectric Nanogenerator Sensor Integrated with a Bistable Micro-Actuator. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3487–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Shi, R.; Liu, Z.; Ouyang, H.; Yu, M.; Zhao, C.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Self-powered implantable electrical stimulator for osteoblasts’ proliferation and differentiation. Nano Energy 2019, 59, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, R.; Ghorbani, H.; Li, W.; Minasyan, A.; Huang, Y.; Lin, S.; Shao, M. Artificial intelligence-enabled innovations in cochlear implant technology: Advancing auditory prosthetics for hearing restoration. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2025, 10, e10752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menia, N.K.; Venkatesh, P. Retinal prosthesis: A comprehensive review. Expert Rev. Ophthalmol. 2025, 20, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, V.P. (Ed.) Artificial Vision: A Clinical Guide, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. xvii+232. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Lei, T.; Xu, J.; Qin, J. Principles, applications, and challenges of E-skin: A mini-review. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 521, 166936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, F.; Yang, Q.; Tang, X.; Shang, S.; Hu, S.; Zhou, G.; Zhuang, L. Bionic sensing and BCI technologies for olfactory improvement and reconstruction. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, I.; Choudhury, B.B.; Sahoo, B.; Sahoo, S.K. A comprehensive review on advances in sensor technologies for prosthetic palms. Spectr. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2025, 3, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghani Dogahe, M.; Mahan, M.A.; Zhang, M.; Bashiri Aliabadi, S.; Rouhafza, A.; Karimzadhagh, S.; Feizkhah, A.; Monsef, A.; Habibi Roudkenar, M. Advancing prosthetic hand capabilities through biomimicry and neural interfaces. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2025, 39, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlyon, R.P.; Goehring, T. Cochlear implant research and development in the twenty-first century: A critical update. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2021, 22, 481–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, J.P.; Hansen, M.R. On the horizon: Cochlear implant technology. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 48, 1097–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.G. Celebrating the one millionth cochlear implant. JASA Express Lett. 2022, 2, 077201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, S.; Kamenov, K.; Cieza, A. The world report on hearing, 2021. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 242–242A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.F.; Al Rashaed, S.; Alhamad, T.A.; Al Kahtani, E.; Al-Dhibi, H.A.; Mura, M.; Nowilaty, S.; Al-Zahrani, Y.A.; Kozak, I.; Al-Sulaiman, S.; et al. Argus II retinal prosthesis for retinitis pigmentosa in the Middle East: The 2015 Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology Gradle Lecture. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2021, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlbauer, D.M.; Dillier, N. A hundred ways to encode sound signals for cochlear implants. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 27, 335–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-García, M.; Prieto-Sánchez-de Puerta, L.; Domínguez-Durán, E.; Sánchez-Gómez, S. Auditory prognosis of patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss in relation to the presence of acute vestibular syndrome: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ear Hear. 2025, 46, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Loizou, P.C. A new sound coding strategy for suppressing noise in cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2008, 124, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, H.J. Music perception with cochlear implants: A review. Trends Amplif. 2004, 8, 49–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.M. The multi-channel cochlear implant: Multi-disciplinary development of electrical stimulation of the cochlea and the resulting clinical benefit. Hear. Res. 2015, 322, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucis, P.A.; Berger-Vachon, C.; Hermann, R.; Millioz, F.; Truy, E.; Gallego, S. Hearing in noise: The importance of coding strategies—Normal-hearing subjects and cochlear implant users. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechner, A.; Dyballa, K.H.; Hehrmann, P.; Fredelake, S.; Lenarz, T. Advanced Beamformers for Cochlear Implant Users: Acute Measurement of Speech Perception in Challenging Listening Conditions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, M.; Hocke, T.; Böhnke, B.; Mauger, S.J. ForwardFocus with cochlear implant recipients in spatially separated and fluctuating competing signals—Introduction of a reference metric. Int. J. Audiol. 2019, 58, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehring, T.; Bolner, F.; Monaghan, J.J.M.; van Dijk, B.; Zarowski, A.; Bleeck, S. Speech enhancement based on neural networks improves speech intelligibility in noise for cochlear implant users. Hear. Res. 2017, 344, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajecki, T.; Zhang, Y.; Nogueira, W. A Deep Denoising Sound Coding Strategy for Cochlear Implants. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 70, 2700–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.H.; Tsao, Y.; Lu, X.; Chen, F.; Su, Y.T.; Chen, K.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, L.C.; Li, P.H.; Lee, C.H. Deep learning-based noise reduction approach to improve speech intelligibility for cochlear implant recipients. Ear Hear. 2018, 39, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, N.R.; Appelbaum, E.N.; Fullmer, T.; Sandulache, V.C.; Sweeney, A.D. A hurricane, temporal bone paraganglioma, cholesteatoma, Bezold’s abscess, and necrotizing fasciitis. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, e149–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieratschker, M.; Yildiz, E.; Schnoell, J.; Hirtler, L.; Schlingensiepen, R.; Honeder, C.; Arnoldner, C. Intratympanic substance distribution after injection of liquid and thermosensitive drug carriers: An endoscopic study. Otol. Neurotol. 2022, 43, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, H.; Kashio, A.; Yamasoba, T. Prediction of cochlear implant fitting by machine learning techniques. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtaş Yılmaz, B. Prediction of auditory performance in cochlear implants using machine learning methods: A systematic review. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieibavani, E.; Goudey, B.; Kiral, I.; Zhong, P.; Jimeno-Yepes, A.; Swan, A.; Gambhir, M.; Buechner, A.; Kludt, E.; Eikelboom, R.H.; et al. Predictive models for cochlear implant outcomes: Performance, generalizability, and the impact of cohort size. Trends Hear. 2021, 25, 23312165211066174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, R.G.; Henslee, A.; Nelson, R.F.; Hansen, M.R. Robotic assistance during cochlear implantation: The rationale for consistent, controlled speed of electrode array insertion. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1335994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B.; Irving, R.; Begg, P.; Du, X. Robotic systems for cochlear implant surgeries: A review of robotic design and clinical outcomes. Electronics 2025, 14, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.A.; Dunn, C.C.; Scheperle, R.A.; Oleson, J.; Claussen, A.D.; Gantz, B.J.; Hansen, M.R. Robotic-assisted electrode array insertion improves rates of hearing preservation. Laryngoscope 2025, 135, 4364–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.H.L.; da Cruz, L. The Argus® II retinal prosthesis system. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 50, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stingl, K.; Bartz-Schmidt, K.U.; Besch, D.; Braun, A.; Bruckmann, A.; Gekeler, F.; Greppmaier, U.; Hipp, S.; Hörtdörfer, G.; Kernstock, C.; et al. Artificial vision with wirelessly powered subretinal electronic implant alpha-IMS. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20130077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, X.; Li, L.; Wu, K.; Zhou, C.; Cao, P.; Ren, Q. C-Sight visual prostheses for the blind. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2008, 27, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouratian, N.; Yoshor, D.; Niketeghad, S.; Dornm, J.; Greenberg, R. Early feasibility study of a neurostimulator to create artificial vision. Neurosurgery 2019, 66, 310–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Gong, C.; Sun, Y.; Qian, X.; Rajendran Nair, D.S.; Li, R.; Zeng, Y.; Ji, J.; Zhang, J.; Kang, H.; et al. Noninvasive imaging-guided ultrasonic neurostimulation with arbitrary 2D patterns and its application for high-quality vision restoration. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4481. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, I.V.; Fan, V.H.; Wiemer, M.W.; Lemoff, B.E.; Sood, K.S.; Mussa, M.J.; Yu, C.Q. In vivo stability of electronic intraocular lens implant for corneal blindness. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.Y.; Gong, S.; Rosenblatt, M.I.; Palanker, D.; Al-Qahtani, A.; Sun, M.G.; Zhou, Q.; Kanu, L.; Chau, F.; Yu, C.Q. Feasibility of intraocular projection for treatment of intractable corneal opacity. Cornea 2019, 38, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, S. The mechanism of human color vision and potential implanted devices for artificial color vision. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1408087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, S.; Borenstein, J.; Koren, Y. The NavBelt-a computerized travel aid for the blind based on mobile robotics technology. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1998, 45, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Dakopoulos, D.; Bourbakis, N.G. Wearable obstacle avoidance electronic travel aids for blind: A survey. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2010, 40, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhao, M.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J.; et al. Multimodal navigation and virtual companion system: A wearable device assisting blind people in independent travel. Sensors 2025, 25, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Lin, Y.N.; Lai, S.N.; Xu, J.J.; He, Y.L.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xu, S.Y. A virtual vision navigation system for the blind using wearable touch-vision devices. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 49, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia, E.; Clark, J.P.; Bianchi, M.; Catalano, M.G.; Bicchi, A.; O’Malley, M.K. Skin stretch haptic feedback to convey closure information in anthropomorphic, under-actuated upper limb soft prostheses. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2019, 12, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyahara, Y.; Kato, R. Development of thin vibration sheets using a shape memory alloy actuator for the tactile feedback of myoelectric prosthetic hands. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Mexico, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 6255–6258. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowska, V.R.; McConnell, A.; Vijayakumar, S.; Stokes, A.; Roche, A.D. A haptic sleeve as a method of mechanotactile feedback restoration for myoelectric hand prosthesis users. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 806479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Li, T.; Bruschini, C.; Enz, C.; Justiz, J.; Antfolk, C.; Koch, V.M. Multi-modal sensory feedback system for upper limb amputees. In Proceedings of the 2017 New Generation of CAS (NGCAS), Genova, Italy, 6–9 September 2017; pp. 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Antfolk, C.; D’Alonzo, M.; Controzzi, M.; Lundborg, G.; Rosen, B.; Sebelius, F.; Cipriani, C. Artificial redirection of sensation from prosthetic fingers to the phantom hand map on transradial amputees: Vibrotactile versus mechanotactile sensory feedback. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2013, 21, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naples, G.; Mortimer, J.; Scheiner, A.; Sweeney, J. A spiral nerve cuff electrode for peripheral nerve stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1988, 35, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, W.M.; Norman, S.E.; Bellamkonda, R.V. Implanted neural interfaces: Biochallenges and engineered solutions. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttaz, E.; Goding, J.; Vallejo-Giraldo, C.; Aregueta-Robles, U.; Lovell, N.; Ghezzi, D.; Green, R.A. Conductive elastomer composites for fully polymeric, flexible bioelectronics. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 1372–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, G.; Xu, Z.; Tang, D.; Chen, T. Recent progress in bionic skin based on conductive polymer gels. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Solomon, S.A.; Gao, W. Artificial intelligence-powered electronic skin. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, A.D.; Bailey, Z.K.; Gonzalez, M.; Vu, P.P.; Chestek, C.A.; Gates, D.H.; Kemp, S.W.P.; Cederna, P.S.; Ortiz-Catalan, M.; Aszmann, O.C. Upper limb prostheses: Bridging the sensory gap. J. Hand Surg. Eur. 2023, 48, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Wu, H. Electronic noses: From gas-sensitive components and practical applications to data processing. Sensors 2024, 24, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickland, E. A Bionic Nose to Smell the Roses Again: Covid Survivors Drive Demand for a Neuroprosthetic Nose. IEEE Spectr. 2022, 59, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, N.S.; Wairagkar, M.; Iacobacci, C.; Hou, X.; Singer-Clark, T.; Willett, F.R.; Kunz, E.M.; Fan, C.; Vahdati Nia, M.; Deo, D.R.; et al. An accurate and rapidly calibrating speech neuroprosthesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angrick, M.; Luo, S.; Rabbani, Q.; Candrea, D.N.; Shah, S.; Milsap, G.W.; Anderson, W.S.; Gordon, C.R.; Rosenblatt, K.R.; Clawson, L.; et al. Online speech synthesis using a chronically implanted brain–computer interface in an individual with ALS. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.B.; Littlejohn, K.T.; Liu, J.R.; Moses, D.A.; Chang, E.F. The speech neuroprosthesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2024, 25, 473–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhilal, S.; Marchesotti, S.; Thirion, B.; Soudrie, B.; Giraud, A.L.; Mandonnet, E. Implantable neural speech decoders: Recent advances, future challenges. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdikenov, B.; Zholtayev, D.; Suleimenov, K.; Assan, N.; Ozhikenov, K.; Ozhikenova, A.; Nadirov, N.; Kapsalyamov, A. Emerging frontiers in robotic upper-limb prostheses: Mechanisms, materials, tactile sensors and machine learning-based EMG control: A comprehensive review. Sensors 2025, 25, 3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzi, N.; Malandri, L.; Mercorio, F.; Pedrocchi, A. XAI for myo-controlled prosthesis: Explaining EMG data for hand gesture classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 240, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, Y.A.; Asogbon, M.G.; Samuel, O.W.; Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Nsugbe, E.; Chen, S.; Li, G. High-density surface EMG signal quality enhancement via optimized filtering technique for amputees’ motion intent characterization towards intuitive prostheses control. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 74, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, S.; Boukadoum, M.; Campeau-Lecours, A.; Gosselin, B. Intuitive real-time control strategy for high-density myoelectric hand prosthesis using deep and transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Ko, H. Fingertip skin–inspired microstructured ferroelectric skins discriminate static/dynamic pressure and temperature stimuli. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, E.; Sperduti, M.; Cordella, F.; Luigi Tagliamonte, N.; Zollo, L. Performance assessment of thermal sensors for hand prostheses. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 27559–27569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Heo, J.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Eom, J.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, I.; Park, H.H.; Mo, H.S.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. A behavior-learned cross-reactive sensor matrix for intelligent skin perception. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2000969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, K.A.; Shin, A.Y.; Kaufman, K.R. Interfaces with the peripheral nervous system for the control of a neuroprosthetic limb: A review. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čvančara, P.; Valle, G.; Müller, M.; Bartels, I.; Guiho, T.; Hiairrassary, A.; Petrini, F.; Raspopovic, S.; Strauss, I.; Granata, G.; et al. Bringing sensation to prosthetic hands—Chronic assessment of implanted thin-film electrodes in humans. npj Flex. Electron. 2023, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkhkar, H.; Christie, B.P.; Triolo, R.J. Sensory neuroprosthesis improves postural stability during Sensory Organization Test in lower-limb amputees. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M.; Creveling, S.; Sullivan, L.M.; Gabert, L.; Lenzi, T. A unified controller for natural ambulation on stairs and level ground with a powered robotic knee prosthesis. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; pp. 2146–2151. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, G.R.; Hood, S.; Lenzi, T. Stand-up, squat, lunge, and walk with a robotic knee and ankle prosthesis under shared neural control. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2021, 2, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarini, A.; Fantozzi, M.; Papapicco, V.; Fagioli, I.; Lanotte, F.; Baldoni, A.; Dell’Agnello, F.; Ferrara, P.; Ciapetti, T.; Molino Lova, R.; et al. A low-power ankle-foot prosthesis for push-off enhancement. Wearable Technol. 2023, 4, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, M.K.; Rouse, E.J. The VSPA foot: A quasi-passive ankle-foot prosthesis with continuously variable stiffness. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 2375–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, T.; Cempini, M.; Newkirk, J.; Hargrove, L.J.; Kuiken, T.A. A lightweight robotic ankle prosthesis with non-backdrivable cam-based transmission. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR), London, UK, 17–20 July 2017; pp. 1142–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Best, T.K.; Welker, C.G.; Rouse, E.J.; Gregg, R.D. Data-driven variable impedance control of a powered knee–ankle prosthesis for adaptive speed and incline walking. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 2151–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, J.; Hood, S.; Gunnel, A.; Lenzi, T. Powered knee and ankle prosthesis with indirect volitional swing control enables level-ground walking and crossing over obstacles. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eaba6635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQahtani, N.J.; Al-Naib, I.; Althobaiti, M. Recent progress on smart lower prosthetic limbs: A comprehensive review on using EEG and fNIRS devices in rehabilitation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1454262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQahtani, N.J.; Al-Naib, I.; Ateeq, I.S.; Althobaiti, M. Hybrid functional near-infrared spectroscopy system and electromyography for prosthetic knee control. Biosensors 2024, 14, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Halawani, R.; Qassem, M.; Kyriacou, P.A. Monte Carlo simulation of the effect of melanin concentration on light–tissue interactions in reflectance pulse oximetry. Sensors 2025, 25, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, H.P.; Bensmaia, S.J. Biomimetic approaches to bionic touch through a peripheral nerve interface. Neuropsychologia 2015, 79, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, F.M.; Valle, G.; Bumbasirevic, M.; Barberi, F.; Bortolotti, D.; Cvancara, P.; Hiairrassary, A.; Mijovic, P.; Sverrisson, A.Ö.; Pedrocchi, A.; et al. Enhancing functional abilities and cognitive integration of the lower limb prosthesis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerratt, A.P.; Michaud, H.O.; Lacour, S.P. Elastomeric electronic skin for prosthetic tactile sensation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 2287–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varaganti, P.; Seo, S. Recent advances in biomimetics for the development of bio-inspired prosthetic limbs. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouri, K.I. Neuralink’s brain-computer interfaces and the reshaping of religious-psychological experience. Conatus-J. Philos. 2025, 10, 9–56. [Google Scholar]

- Neuralink. A Year of Telepathy. 2025. Available online: https://neuralink.com/updates/a-year-of-telepathy/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Feasibility Study of the Neuralink N1 Implant in People with Quadriplegia. 2025. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06429735 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Jiang, L.; Stocco, A.; Losey, D.M.; Abernethy, J.A.; Prat, C.S.; Rao, R.P.N. BrainNet: A multi-person brain-to-brain interface for direct collaboration between brains. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, B.; Lee, C.; Chung, Y.A.; Kim, L.; Yoo, S.S. Non-invasive transmission of sensorimotor information in humans using an EEG/focused ultrasound brain-to-brain interface. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Truong, N.D.; Nikpour, A.; Kavehei, O. A miniaturized and low-energy subcutaneous optical telemetry module for neurotechnology. J. Neural Eng. 2023, 20, 036017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteensel, M.J.; Pels, E.G.; Bleichner, M.G.; Branco, M.P.; Denison, T.; Freudenburg, Z.V.; Gosselaar, P.; Leinders, S.; Ottens, T.H.; Van Den Boom, M.A.; et al. Fully implanted brain–computer interface in a locked-in patient with ALS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2060–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, U.; Xia, B.; Silvoni, S.; Cohen, L.G.; Birbaumer, N. Brain–computer interface–based communication in the completely locked-in state. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e1002593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, U.; Vlachos, I.; Zimmermann, J.B.; Espinosa, A.; Tonin, A.; Jaramillo-Gonzalez, A.; Khalili-Ardali, M.; Topka, H.; Lehmberg, J.; Friehs, G.M.; et al. Spelling interface using intracortical signals in a completely locked-in patient enabled via auditory neurofeedback training. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, W.; Ma, W.; Deng, Y.; Song, W. Self-Powered Hybrid Motion and Health Sensing System Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Small 2024, 20, 2402452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, M.; Paghi, A.; Mariani, S.; Golinelli, G.; Debrassi, A.; Egri, G.; Leo, G.; Vandini, E.; Vilella, A.; Dähne, L.; et al. Bioresorbable Nanostructured Chemical Sensor for Monitoring of pH Level In Vivo. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2202062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.J.; Kim, S.H. Toward long-term implantable glucose biosensors for clinical use. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirwal, G.K.; Wu, K.Y.; Ramnawaz, T.P.; Xu, Y.; Carbonneau, M.; Nguyen, B.H.; Tran, S.D. Chapter Ten—Implantable biosensors: Advancements and applications. In Biosensing the Future: Wearable, Ingestible and Implantable Technologies for Health and Wellness Monitoring Part B; Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; Volume 216, pp. 279–312. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Gou, G.y.; Fang, Z.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Cheng, J.; Han, M.; Ma, T.; Liu, C.; et al. Recent Advancements in Physiological, Biochemical, and Multimodal Sensors Based on Flexible Substrates: Strategies, Technologies, and Integrations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 21721–21745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Lin, B.S.; Tsai, C.H.; Yang, C.T.; Lin, B.S. Design of Wearable Breathing Sound Monitoring System for Real-Time Wheeze Detection. Sensors 2017, 17, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Chou, E.F.; Le, J.; Wong, S.; Chu, M.; Khine, M. Soft wearable pressure sensors for beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassanos, P.; Rosa, B.G.; Keshavarz, M.; Yang, G.Z. From wearables to implantables—Clinical drive and technical challenges. In Wearable Sensors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 29–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, X.L.; Li, Z.H.; Zhu, Z.G.; Qian, S.H.; Flewitt, A.J. Current and emerging technology for continuous glucose monitoring. Sensors 2017, 17, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Yerraguntla, K.R.; Jenne, M.P.; Gadi, A.; Sepoori, A.; Gunda, A.; Gudivada, M.S. Advancements in continuous glucose monitoring: A revolution in diabetes management. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Aktar, M.N.; Preda, V.; Nasiri, N. Advances in electrochemical sensors for real-time glucose monitoring. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Z.; Xia, Y.; Dong, H.; Shen, Y.; Feng, Z.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yin, B.; Ji, Z.; Xu, Q.; et al. Microfluidic Wearable Electrochemical Sensor Based on MOF-Derived Hexagonal Rod-Shaped Porous Carbon for Sweat Metabolite and Electrolyte Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 16676–16685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Tao, M.; Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W. Microelectrode-based electrochemical sensing technology for in vivo detection of dopamine: Recent developments and future prospects. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2022, 52, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.C.; Guo, Z.J.; Xi, Y.; Wang, M.H.; Ji, B.W.; Tian, H.C.; Kang, X.Y.; Liu, J.Q. Implantable Brain Computer Interface Devices Based on Mems Technology. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 34th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Munich, Germany, 24–28 January 2021; pp. 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, J.; Lim, H.K.; Kim, N.H.; Park, J.K.; Kang, E.S.; Kim, Y.T.; Heo, C.; Lee, O.S.; Kim, S.G.; Yun, W.S.; et al. Supramolecular peptide hydrogel-based soft neural interface augments brain signals through a three-dimensional electrical network. Acs Nano 2020, 14, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinoldi, C.; Ziai, Y.; Zargarian, S.S.; Nakielski, P.; Zembrzycki, K.; Haghighat Bayan, M.A.; Zakrzewska, A.B.; Fiorelli, R.; Lanzi, M.; Kostrzewska-Ksiezyk, A.; et al. In vivo chronic brain cortex signal recording based on a soft conductive hydrogel biointerface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 15, 6283–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Innovative Applications of Nanotechnology in Neuroscience and Brain-computer Interfaces. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2025, 126, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Yang, J.; Wei, X.; Sun, L.; Tao, T.H.; Zhou, Z. A MEMS-based miniaturized wireless fully-implantable brain-computer interface system. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 38th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 19–23 January 2025; pp. 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, P.M.; Venniyoor, A. Neuralink and brain–computer interface—Exciting times for artificial intelligence. South Asian J. Cancer 2024, 13, 063–065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Bonhage, A. Brain stimulation as a neuromodulatory epilepsy therapy. Seizure 2017, 44, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.T.; Morrell, M.J. The RNS system: Responsive cortical stimulation for the treatment of refractory partial epilepsy. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2014, 11, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Gong, B.; Sheng, H.; Song, Z.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Y. The best indices of anaesthesia depth monitored by electroencephalogram in different age groups. Int. J. Neurosci. 2024, 136, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalbaf, A.; Saffar, M.; Sleigh, J.W.; Shalbaf, R. Monitoring the depth of anesthesia using a new adaptive neurofuzzy system. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2017, 22, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formaggio, E.; Tonellato, M.; Antonini, A.; Castiglia, L.; Gallo, L.; Manganotti, P.; Masiero, S.; Del Felice, A. Oscillatory EEG-TMS reactivity in Parkinson disease. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2023, 40, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoš, M.; Bočková, M.; Goldemundová, S.; Baláž, M.; Chrastina, J.; Rektor, I. The effect of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease reflected in EEG microstates. npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, A.; Poongodi, T.; Yadav, M.; Balusamy, B. Internet of things in healthcare wearable and implantable body sensor network (WIBSNs). In Soft Computing in Wireless Sensor Networks; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 193–224. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Yoon, H.; Zahed, M.A.; Park, C.; Kim, D.; Park, J.Y. Multifunctional hybrid skin patch for wearable smart healthcare applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 196, 113685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ahadian, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Cao, T.; Lin, W.; Wu, D.; de Barros, N.R.; Zare, M.R.; et al. Smart contact lenses for biosensing applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gao, W. Physiological state assessment and prediction based on multi-sensor fusion in body area network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 65, 102340. [Google Scholar]

- Kärcher, S.M.; Fenzlaff, S.; Hartmann, D.; Nagel, S.K.; König, P. Sensory augmentation for the blind. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, E.E.; Carra, R.; Nicolelis, M.A.L. Perceiving invisible light through a somatosensory cortical prosthesis. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, R.; Kartha, A.; Barry, M.P.; Bradley, C.; Gibson, P.; Caspi, A.; Roy, A.; Dagnelie, G. Glow in the dark: Using a heat-sensitive camera for blind individuals with prosthetic vision. Vis. Res. 2021, 184, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Teng, S.; Gaub, B.M.; Rodgers, C.C.; Li, C.; DeWeese, M.R.; Harper, N.S. A device for human ultrasonic echolocation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 62, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, V.; Spagnolo, V.; Galván, C.M.; Nieto, N.; Spies, R.D.; Milone, D.H. Towards subject-centered co-adaptive brain–computer interfaces based on backward optimal transport. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 046006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, E.; Mitterwallner, M.; Radjenovic, S.; Grigoryeva, D.; Weber, A.; Stögmann, E.; Domitner, A.; Zettl, A.; Osou, S.; Beisteiner, R. Ultrasound neuromodulation with transcranial pulse stimulation in Alzheimer disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2459170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzyat, Y.; Wanda, P.A.; Levy, D.F.; Kadel, A.; Aka, A.; Pedisich, I.; Sperling, M.R.; Sharan, A.D.; Lega, B.C.; Burks, A.; et al. Closed-loop stimulation of temporal cortex rescues functional networks and improves memory. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deadwyler, S.A.; Hampson, R.E.; Song, D.; Opris, I.; Gerhardt, G.A.; Marmarelis, V.Z.; Berger, T.W. A cognitive prosthesis for memory facilitation by closed-loop functional ensemble stimulation of hippocampal neurons in primate brain. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 287, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragel, J.E.; Lurie, S.M.; Issa, N.P.; Haider, H.A.; Wu, S.; Tao, J.X.; Warnke, P.C.; Schuele, S.; Rosenow, J.M.; Zelano, C.; et al. Closed–loop control of theta oscillations enhances human hippocampal network connectivity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, S.U.; Schumann, F.; Keyser, J.; Goeke, C.; Krause, C.; Wache, S.; Lytochkin, A.; Ebert, M.; Brunsch, V.; Wahn, B.; et al. Learning new sensorimotor contingencies: Effects of long-term use of sensory augmentation on the brain and conscious perception. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, K.; König, S.; Schwandt, J.; König, P. The experience of new sensorimotor contingencies by sensory augmentation. Conscious. Cogn. 2014, 28, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lv, B.; Wu, J. Review on infrared imaging technology. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasundera, S.A.B.N.; Peiris, M.P.W.S.S.; Rathnayake, R.G.G.A.; Aluthge, A.D.K.H.; Geethanjana, H.K.A. Investigating the Efficacy of Brain-Computer Interfaces in Enhancing Cognitive Abilities for Direct Brain-to-Machine Communication. Int. J. Adv. ICT Emerg. Reg. (ICTer) 2025, 18, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangwan, N.S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Ram, V.; Singh, V.; Alghamdi, B.S.; Abuzenadah, A.M.; Singh, M.F. Brain augmentation and neuroscience technologies: Current applications, challenges, ethics and future prospects. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1000495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.; Lee, J.; Beak, C.J.; Biswas, S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H. Flexible Neuromorphic Electronics for Wearable Near-Sensor and In-Sensor Computing Systems. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2416073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzyat, Y.; Kragel, J.E.; Burke, J.F.; Levy, D.F.; Lyalenko, A.; Wanda, P.; O’Sullivan, L.; Hurley, K.B.; Busygin, S.; Pedisich, I.; et al. Direct brain stimulation modulates encoding states and memory performance in humans. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Harway, M.; Marmarelis, V.Z.; Hampson, R.E.; Deadwyler, S.A.; Berger, T.W. Extraction and restoration of hippocampal spatial memories with non-linear dynamical modeling. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucewicz, M.T.; Worrell, G.A.; Axmacher, N. Direct electrical brain stimulation of human memory: Lessons learnt and future perspectives. Brain 2023, 146, 2214–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsetaki, M.E. Brain-computer interfaces for memory enhancement: Scientometric analysis and future directions. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2026, 112, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Kumar, J.; Sheoran, P. Integration of cloud computing in BCI: A review. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 87, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.; Cicirelli, F.; D’Amore, F.; Gentile, A.F.; Guerrieri, A.; Vinci, A. Using brain-computer interface in cognitive buildings: A real-time case study. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference on Human-Machine Systems (ICHMS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 26–28 May 2025; pp. 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Sladky, V.; Nejedly, P.; Mivalt, F.; Brinkmann, B.H.; Kim, I.; St. Louis, E.K.; Gregg, N.M.; Lundstrom, B.N.; Crowe, C.M.; Attia, T.P.; et al. Distributed brain co-processor for tracking spikes, seizures and behaviour during electrical brain stimulation. Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.R.; Angelica, A.; Chakravarthy, K.; Svidinenko, Y.; Boehm, F.J.; Opris, I.; Lebedev, M.A.; Swan, M.; Garan, S.A.; Rosenfeld, J.V.; et al. Human brain/cloud interface. In Advances in Clinical Immunology, Medical Microbiology, COVID-19, and Big Data; Jenny Stanford Publishing: Singapore, 2021; pp. 485–538. [Google Scholar]

- Vakilipour, P.; Fekrvand, S. Brain-to-brain interface technology: A brief history, current state, and future goals. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2024, 84, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, C.; Ginhoux, R.; Riera, A.; Nguyen, T.L.; Chauvat, H.; Berg, M.; Amengual, J.L.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Ruffini, G. Conscious brain-to-brain communication in humans using non-invasive technologies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.S.; Kim, H.; Filandrianos, E.; Taghados, S.J.; Park, S. Non-invasive brain-to-brain interface (BBI): Establishing functional links between two brains. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60410. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Yuan, S.; Huang, L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Z.; Xu, K.; Pan, G. Human mind control of rat cyborg’s continuous locomotion with wireless brain-to-brain interface. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wang, R.; Luo, M. An optical brain-to-brain interface supports rapid information transmission for precise locomotion control. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 875–885. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, S.V.; Tirkey, R.; Singh, V. Real-time streaming in distributed and cooperative sensing networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kamand, India, 24–28 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Yin, H.; Zou, K.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, Y. One-dimensional implantable sensors for accurately monitoring physiological and biochemical signals. Research 2024, 7, 0507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, X.; Lennartz, M.R.; Loegering, D.J.; Stenken, J.A. Long-term calibration considerations during subcutaneous microdialysis sampling in mobile rats. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4530–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.K.; Downs, A.M.; Ortega, G.; Kurnik, M.; Plaxco, K.W. Elucidating the mechanisms underlying the signal drift of electrochemical aptamer-based sensors in whole blood. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 3340–3347. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Nie, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, S.; Xiang, Z.; Lin, X.; Lu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, P.; et al. Millimeter-scale magnetic implants paired with a fully integrated wearable device for wireless biophysical and biochemical sensing. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadm9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrolainen, M.; Rigsby, P.; Eddy, S.; Vadgama, P. Bio-/haemocompatibility: Implications and outcomes for sensors? Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1995, 39, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.L.; Guterstam, A.; Cronin, J.; Olson, J.D.; Ehrsson, H.H.; Ojemann, J.G. Ownership of an artificial limb induced by electrical brain stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losey, D.M.; Stocco, A.; Abernethy, J.A.; Rao, R.P.N. Navigating a 2D virtual world using direct brain stimulation. Front. Robot. AI 2016, 3, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.W.; Shin, H.B.; Lee, S.W. Brain-guided self-paced curriculum learning for adaptive human-machine interfaces. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 4693–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, T.H. Recent progress in bio-integrated intelligent sensing system. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2022, 4, 2100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khorin, P.A.; Khonina, S.N. Biochips on the move: Emerging trends in wearable and implantable lab-on-chip health monitors. Electronics 2025, 14, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Tao, R.; Xiong, N.; Pan, X. CS-PLM: Compressive sensing data gathering algorithm based on packet loss matching in sensor networks. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 5131949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.; Mamidanna, P.; Nielsen, J.J.; Chiariotti, F.; Stefanović, Č.; Došen, S.; Popovski, P. Closed-loop manual control with tactile or visual feedback under wireless link impairments. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2025, 18, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Flores, H.; Hui, P. Towards collaborative multi-device computing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops), Athens, Greece, 19–23 March 2018; pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Marblestone, A.H.; Zamft, B.M.; Maguire, Y.G.; Shapiro, M.G.; Cybulski, T.R.; Glaser, J.I.; Amodei, D.; Stranges, P.B.; Kalhor, R.; Dalrymple, D.A.; et al. Physical principles for scalable neural recording. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, P.D. Thermal considerations for the design of an implanted cortical brain–machine interface (BMI). In Indwelling Neural Implants: Strategies for Contending with the In Vivo Environment; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Seese, T.M.; Harasaki, H.; Saidel, G.M.; Davies, C.R. Characterization of tissue morphology, angiogenesis, and temperature in the adaptive response of muscle tissue to chronic heating. Lab. Investig. 1998, 78, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, A.R.; Chow, E.Y.; Abdel-Latief, O.; Irazoqui, P.P. Low-power, high data rate transceiver system for implantable prostheses. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2010, 2010, 563903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Besnoff, J.S.; Reynolds, M.S. Modulated backscatter for ultra-low power uplinks from wearable and implantable devices. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Workshop on Medical Communication Systems, 2012, MedCOMM ’12, Helsinki, Finland, 13–17 August 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mutashar, S.; Hannan, M.A.; Samad, S.A.; Hussain, A. Analysis and optimization of spiral circular inductive coupling link for bio-implanted applications on air and within human tissue. Sensors 2014, 14, 11522–11541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, E.; Casados, C.; Truong, B.D.; Roundy, S. Optimal transmit coil design for wirelessly powered biomedical implants considering magnetic field safety constraints. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2021, 63, 1735–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silchenko, A.N.; Tass, P.A. Mathematical modeling of chemotaxis and glial scarring around implanted electrodes. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 023009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, E.J.; Mastinu, E.; Ortiz-Catalan, M. Cross-channel impedance measurement for monitoring implanted electrodes. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 4880–4883. [Google Scholar]

- González-González, M.A.; Conde, S.V.; Latorre, R.; Thébault, S.C.; Pratelli, M.; Spitzer, N.C.; Verkhratsky, A.; Tremblay, M.È.; Akcora, C.G.; Hernández-Reynoso, A.G.; et al. Bioelectronic medicine: A multidisciplinary roadmap from biophysics to precision therapies. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1321872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikov, V.S.; Tresco, P.A.; Reichert, W.M. Response of brain tissue to chronically implanted neural electrodes. J. Neurosci. Methods 2005, 148, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Valle, J.; Rodríguez-Meana, B.; Navarro, X. Neural electrodes for long-term tissue interfaces. In Somatosensory Feedback for Neuroprosthetics; Güçlü, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Chapter 16; pp. 509–536. [Google Scholar]

- Sohal, H.S.; Clowry, G.J.; Jackson, A.; O’Neill, A.; Baker, S.N. Mechanical flexibility reduces the foreign body response to long-term implanted microelectrodes in rabbit cortex. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoestenberghe, A.; Donaldson, N. Corrosion of silicon integrated circuits and lifetime predictions in implantable electronic devices. J. Neural Eng. 2013, 10, 031002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhou, D.D. Technology advances and challenges in hermetic packaging for implantable medical devices. In Implantable Neural Prostheses 2: Techniques and Engineering Approaches; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 27–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cogan, S.F. Neural stimulation and recording electrodes. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 10, 275–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takmakov, P.; Ruda, K.; Phillips, K.S.; Isayeva, I.S.; Krauthamer, V.; Welle, C.G. Rapid evaluation of the durability of cortical neural implants using accelerated aging with reactive oxygen species. J. Neural Eng. 2015, 12, 026003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, P.; Mahajan, A.; Himes, A.; Lowell, M.; Budde, R.; Vijayaraman, P. Mechanisms of damage related to ICD and pacemaker lead interaction. Heart Rhythm O2 2023, 4, 820–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.M.; Hong, G.; Viveros, R.D.; Zhou, T.; Lieber, C.M. Highly scalable multichannel mesh electronics for stable chronic brain electrophysiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10046–E10055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hassler, C.; Boretius, T.; Stieglitz, T. Polymers for neural implants. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2011, 49, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Y.; Saito, I.; Hoshino, T.; Suzuki, T.; Mabuchi, K. Preliminary study of multichannel flexible neural probes coated with hybrid biodegradable polymer. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, New York City, NY, USA, 30 August–3 September 2006; pp. 660–663. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.S.; Koo, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, G.; Avila, R.; Ying, H.; Reeder, J.; Hambitzer, L.; Im, K.; Kim, J.; et al. Biodegradable polyanhydrides as encapsulation layers for transient electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, A.N.; Robles, U.A.; Huynh, M.; Nayagam, B.A.; Green, R.A.; Poole-Warren, L.A.; Fallon, J.B.; Shepherd, R.K. Electrochemical and biological performance of chronically stimulated conductive hydrogel electrodes. J. Neural Eng. 2020, 17, 026018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi Farzaneh, M.; Nair, S.; Nasseri, M.A.; Knoll, A. Reducing communication-related complexity in heterogeneous networked medical systems considering non-functional requirements. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology, PyeongChang, Republic of Korea, 16–19 February 2014; pp. 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Raghunathan, A.; Jha, N.K. Trustworthiness of medical devices and body area networks. Proc. IEEE 2014, 102, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, P. Neural interfaces for implantable medical devices: Circuit design considerations for sensing, stimulation, and safety. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Mag. 2016, 8, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez, L.D.; Shekhtman, L.; La Rocca, C.E.; Zhang, X.; Buldyrev, S.V.; Trunfio, P.A.; Braunstein, L.A.; Havlin, S. Cascading failures in complex networks. J. Complex Netw. 2020, 8, cnaa013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bequette, B.W. Fault detection and safety in closed-loop artificial pancreas systems. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2014, 8, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle Francis J., I.; Huyett, L.M.; Lee, J.B.; Zisser, H.C.; Dassau, E. Closed-loop artificial pancreas systems: Engineering the algorithms. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Bequette, B.W.; Cameron, F.; Baysal, N.; Howsmon, D.P.; Buckingham, B.A.; Maahs, D.M.; Levy, C.J. Algorithms for a single hormone closed-loop artificial pancreas: Challenges pertinent to chemical process operations and control. Processes 2016, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevlakis, S.E.; Boulogeorgos, A.A.A.; Sofotasios, P.C.; Muhaidat, S.; Karagiannidis, G.K. Optical wireless cochlear implants. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Koolivand, Y.; Sodagar, A.M. Pulse-based, multi-beam optical link for data telemetry to implantable biomedical microsystems. In Proceedings of the 2022 20th IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference (NEWCAS), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 19–22 June 2022; pp. 529–532. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Halder, S.; Bykov, A.; Popov, A.; Meglinski, I.V.; Katz, M. In-body communications exploiting light: A proof-of-concept study using ex vivo tissue samples. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 190378–190389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, L.; Carter, R.E.; Rynes, M.L.; Dominguez, J.; Chen, G.; Naik, A.; Hu, J.; Sagar, M.A.K.; Haltom, L.; Mossazghi, N.; et al. Cortex-wide neural interfacing via transparent polymer skulls. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.; Ouellette, B.; Ramirez, T.K.; Cahoon, A.; Cabasco, H.; Browning, Y.; Lakunina, A.; Lynch, G.F.; McBride, E.G.; Belski, H.; et al. SHIELD: Skull-shaped hemispheric implants enabling large-scale electrophysiology datasets in the mouse brain. Neuron 2024, 112, 2869–2885.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Xia, Z.; Fu, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Cui, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A hybrid titanium-softmaterial, high-strength, transparent cranial window for transcranial injection and neuroimaging. Biosensors 2022, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, R.; Schmidt, C.C.; Emptage, N.J.; Booth, M.J. Focusing light in biological tissue through a multimode optical fiber: Refractive index matching. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 2386–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, I.; Cicchi, R.; Silvestri, L.; Vanzi, F.; Pavone, F.S. In-vivo and ex-vivo optical clearing methods for biological tissues: Review. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 5251–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, B.; Neasham, J.; Degenaar, P. What ultrasound can and cannot do in implantable medical device communications. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 16, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, M.; Kiani, M. Design and optimization of ultrasonic wireless power transmission links for millimeter-sized biomedical implants. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2017, 11, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.; Oelze, M.; Podkowa, A. Mbps experimental acoustic through-tissue communications: MEAT-COMMS. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 17th International Workshop on Signal Processing Advances in Wireless Communications (SPAWC), Edinburgh, UK, 3–6 July 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- van Neer, P.L.M.J.; Peters, L.C.J.M.; Verbeek, R.G.F.A.; Peeters, B.; de Haas, G.; Hörchens, L.; Fillinger, L.; Schrama, T.; Merks-Swolfs, E.J.W.; Gijsbertse, K.; et al. Flexible large-area ultrasound arrays for medical applications made using embossed polymer structures. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Miller, R.J.; Singer, A.C.; Oelze, M.L. High data rate communications in vivo using ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 68, 3308–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Fu, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, X.; Jiao, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. A flexible, stretchable system for simultaneous acoustic energy transfer and communication. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Dalrymple, A.N.; Yu, Z.; Balakrishnan, G.; Bettinger, C.J.; Weber, D.J.; Yang, K.; Robinson, J.T. Miniature battery-free bioelectronics. Science 2023, 382, eabn4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebda, A.; Cosnier, S.; Alcaraz, J.P.; Holzinger, M.; Le Goff, A.; Gondran, C.; Boucher, F.; Giroud, F.; Gorgy, K.; Lamraoui, H.; et al. Single glucose biofuel cells implanted in rats power electronic devices. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yi, Z.; Ma, Y.; Xie, F.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Dong, X.; Liu, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Direct powering a real cardiac pacemaker by natural energy of a heartbeat. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 2822–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.; Park, H.m.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, B.; Myoung, H.S.; Kim, T.Y.; Yoon, H.J.; Kwak, S.S.; Kim, J.; Hwang, T.H.; et al. Self-rechargeable cardiac pacemaker system with triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; O’Donovan, S.; Xiao, X.; Wan, X.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J.; Chen, J. Implantable triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered cardiovascular healthcare. Small 2023, 19, 2207600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, D.; Aili, A.; Zhang, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, J.; Geng, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. High-performance wearable thermoelectric generator with self-healing, recycling, and Lego-like reconfiguring capabilities. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe0586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, J. Fluidic phase-change materials with continuous latent heat from theoretically tunable ternary metals for efficient thermal management. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2200223119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.; Ahn, J.; Lee, J.; Ko, S.H. Functional materials and innovative strategies for wearable thermal management applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, J.T.; Xie, Z.; Yang, Q.; Seo, M.H.; Yan, Y.; Deng, Y.; Jinkins, K.R.; Krishnan, S.R.; Liu, C.; McKay, S.; et al. Soft, bioresorbable coolers for reversible conduction block of peripheral nerves. Science 2022, 377, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, D.F.; Goldring, A.B.; Yamayoshi, I.; Tsourkas, P.; Recanzone, G.H.; Tiriac, A.; Pan, T.; Simon, S.I.; Krubitzer, L. Fabrication of an inexpensive, implantable cooling device for reversible brain deactivation in animals ranging from rodents to primates. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 107, 3543–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.N.; Clément, J.P.; Alameri, A.; Ng, A.; Kennedy, T.E.; Juncker, D. Mechanically matched silicone brain implants reduce brain foreign body response. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2021, 6, 2000909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.K.; Park, D.J.; Skousen, J.L.; Hess-Dunning, A.E.; Tyler, D.J.; Rowan, S.J.; Weder, C.; Capadona, J.R. Mechanically-compliant intracortical implants reduce the neuroinflammatory response. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 056014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; He, T. Silver-nanowire-based elastic conductors: Preparation processes and substrate adhesion. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Bu, F.; Wang, Y.; Chee, P.S.; Liu, X.; Guan, C. Stretchable liquid metal based biomedical devices. npj Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Nirmale, V.S.; Reddy, V.S.; Koutsos, V.; Ramakrishna, S.; Radacsi, N. Enhancing the Performance of Wearable Flexible Sensors via Electrospinning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 39747–39771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Hong, G.; Fu, T.M.; Yang, X.; Schuhmann, T.G.; Viveros, R.D.; Lieber, C.M. Syringe-injectable mesh electronics integrate seamlessly with minimal chronic immune response in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5894–5899. [Google Scholar]

- Place, E.S.; George, J.H.; Williams, C.K.; Stevens, M.M. Synthetic polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Song, J.; Peng, Y. New insights and perspectives into biodegradable metals in cardiovascular stents: A mini review. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, A.; Ghezzi, D. Transient electronics: New opportunities for implantable neurotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 72, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Murphy, R.K.J.; Hwang, S.W.; Lee, S.M.; Harburg, D.V.; Krueger, N.A.; Shin, J.; Gamble, P.; Cheng, H.; Yu, S.; et al. Bioresorbable silicon electronic sensors for the brain. Nature 2016, 530, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Liu, Z.; Bai, W.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Xue, Y.; Kandela, I.; Pezhouh, M.; MacEwan, M.R.; Huang, Y.; et al. Bioresorbable optical sensor systems for monitoring of intracranial pressure and temperature. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Yin, R.T.; Pfenniger, A.; Koo, J.; Avila, R.; Benjamin Lee, K.; Chen, S.W.; Lee, G.; Li, G.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Fully implantable and bioresorbable cardiac pacemakers without leads or batteries. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekki, Y.M.; Luijten, G.; Hagert, E.; Belkhair, S.; Varghese, C.; Qadir, J.; Solaiman, B.; Bilal, M.; Dhanda, J.; Egger, J.; et al. Digital twins for the era of personalized surgery. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopsen, T.; Gerrits, W.; van Osta, N.; van Loon, T.; Wouters, P.; Prinzen, F.W.; Vernooy, K.; Delhaas, T.; Teske, A.J.; Meine, M.; et al. Virtual pacing of a patient’s digital twin to predict left ventricular reverse remodelling after cardiac resynchronization therapy. EP Eur. 2024, 26, euae009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, L. The Ethics of Brain–Computer Interfaces. 2019. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02214-2 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Gordon, E.C.; Seth, A.K. Ethical considerations for the use of brain–computer interfaces for cognitive enhancement. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Chen, H. Does brain-computer interface-based mind reading threaten mental privacy? ethical reflections from interviews with Chinese experts. BMC Med Ethics 2025, 26, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref (Year) | Class/Function | Interface and Site | Key Outputs/Outcomes | Main Limitation/Bottleneck | Key Sensor Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] (2024) | I/Auditory restoration | Fully Implantable CI | In vivo guinea pig validation: frequency-selective stimulation; eABR evoked for ∼45–100 dB SPL | Weak off-resonance/band-edge sensitivity; packaging needed; power–range trade-off | 8-ch MEMS; ∼300 mVpp@100 dB; <600 W |

| [21] (2024) | I/Auditory restoration | Noise reduction technology of CI | Significant improvement in multi-talker speech-in-noise perception | High computational cost; not yet fully implantable in real time | 20% intelligibility (+5 dB SNR); 22 channels; high stability; low-latency RNN |

| [22] (2016) | I/Visual restoration | Epiretinal electrode array (retina) | Stable perception of light and spatial location over 5 years | Extremely low spatial resolution; reliance on external camera | 60 electrodes ( 20/1260 acuity); chronic 5+ years; wireless inductive low mW. |

| [23] (2015) | I/Visual restoration | Subretinal photodiode array (retina) | Higher visual acuity than epiretinal systems in preclinical studies | Limited field of view; requires external IR projector | 70 m pixels; preclinical acute; photovoltaic IR low power. |

| [24] (2023) | I/Speech restoration | Intracortical microelectrodes (motor cortex) | Real-time speech synthesis up to ∼62 words/min in paralyzed patients | Invasive interface; limited vocabulary size and long-term stability | 62 wpm speech; 23.8% WER; 80 ms latency; 128 electrodes |

| [25] (2018) | I/Tactile restoration | E-skin sensors with peripheral nerve interface | Restored pain sensations and enabled discrimination of object curvature and sharpness via the prosthesis | Single-subject demonstration; coarse and non-natural sensations | 0–300 kPa range; graded touch-pain; 3 taxels/fingertip; multilayer higher epidermal sensitivity |

| [26] (2019) | I/Tactile restoration | Peripheral nerve electrodes (upper limb) | Biomimetic sensory feedback via nerve stimulation improved dexterous bionic hand control and embodiment | Study limited to a single participant | Contact force/torque sensors: 0–25.6 N range, 0.1 N/bit, 30 Hz. |

| [27] (2025) | I/Olfactory restoration | Olfactory bulb interface | Induced smell perception via olfactory bulb electrical stimulation | Small sample (n = 5); subjective reports without objective confirmation | Induced smell (3/5 subjects); 1–20 mA, 3.17 Hz; subjective perception; small-sample. |

| [28] (2019) | II/Cardiac sensing | Implantable TENG pressure sensor (ventricle) | Self-powered ultrasensitive sensor enables real-time endocardial pressure monitoring | Limited to animal testing; durability and chronic stability unclear | Self-powered; 1.195 mV/mmHg sensitivity; R2 = 0.997; 0–350 mmHg; 108 cycles |

| [29] (2021) | II/Cardiac sensing | Gapless TENG sensor (myocardium) | No-spacer TENG enables precise cardiac monitoring | Preclinical testing in animal model | Self-powered; 3.67 V Voc, 51.7 nA Isc, 99.7% HR, -cycle stable |

| [30] (2022) | II/Cardiac regulation | TENG-based stimulation interface (myocardium) | Self-triggered pacing improves cardiac function in animal models | Insufficient output energy for large-scale or human application | Self-powered TENG; 0.4–20 V, 20–80 V/cm EF, 100–400 µm depth |

| [31] (2018) | II/Metabolic regulation | TENG sensor with vagus nerve interface | Closed-loop appetite suppression and weight reduction in rats | Unknown long-term biocompatibility; invasive implantation | Battery-free; 0.05–0.12 V pulses, 12-week stable, 40 µW |

| [32] (2018) | II/Urinary control | TENG sensor with SMA actuator (bladder wall) | Autonomous on-demand bladder voiding in underactive models | Early feasibility stage; limited lifespan of actuatorsq | Output 35.6–114 mV for 0–6.86 N; saturates 0.67 mL |

| [33] (2019) | II/Orthopedic therapy | TENG electrodes at fracture site | Enhanced osteogenesis and bone healing in osteoporotic rats | Low stimulation power; preclinical validation only | TENG 100 V, 1.6 A; EF 150 V/cm, 250 m |

| Ref (Year) | Class/Function | Interface and Site | Key Outputs/Outcomes | Main Limitation/Bottleneck | Key Sensor Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [156] (2012) | III/Geomagnetic sense | Vibrotactile belt (waist skin) | Users developed a “sense of north”; improved navigation/orientation tasks | Requires long training; limited information bandwidth (direction only) | Pointing error 41 → 23°, 163 → 84°; walk deviation 10° |

| [157] (2013) | III/Infrared sense | Intracortical microstimulation (S1 cortex, rat) | Rats learned to detect IR signals; new IR perception coexisted with normal touch | Invasive animal implant; simple stimulus representation (single-pixel IR) | IR prosthesis: ICMS 0–400 Hz, 93% correct, 1.3 s |

| [158] (2021) | III/Infrared sense | Retinal prosthesis input fusion (Argus II) | Improved night navigation and human detection for prosthetic vision users | Additional external hardware; low-resolution thermal overlay | Thermal camera: 60 electrodes; FOV ( 22° diagonal); 200 m diameter |

| [159] (2015) | III/Echolocation | Head-mounted ultrasonic sensor + stereo audio | Users learned to judge object distance/direction via sound after training | Training-dependent; limited spatial resolution and throughput vs. natural vision | 25–50 kHz bandwidth; 160° microphone field of view; echoes to 5 m; 75–86% correct |

| [160] (2025) | IV/BCI skill learning | EEG headset (scalp) | Improved motor-imagery BCI accuracy via co-adaptive neurofeedback training | non-invasive signals limit resolution; gains can be task-specific | 62 electrodes; 512–1000 Hz sampling; 0.5–40 Hz bandwidth. |

| [161] (2025) | IV/Cognitive therapy | Transcranial ultrasound (head) | Reported cognitive-score improvements and increased brain network activity vs. sham | Mechanism unclear; small cohort and transient effects | flux; 5 Hz frequency; 3 s duration1. |

| [162] (2018) | IV/Memory enhancement | Cortical electrodes (temporal lobe) | Improved word recall with adaptive, timed stimulation in epilepsy patients | Invasive; variable benefit across individuals and tasks | 3–180 Hz bandwidth; 0.61 AUC; OR 1.18 (recall) |

| [163] (2017) | IV/Memory enhancement | Depth electrodes (hippocampus, primate) | Improved memory-task performance using closed-loop hippocampal pattern stimulation | Highly invasive; demonstrated only in animal models with external computing | 10–50 A current; 1.0 ms pulses; ≤ 20 Hz frequency; 70–75% accuracy. |

| [164] (2025) | IV/Memory enhancement | Depth electrodes (hippocampus, human) | Enhanced hippocampal network connectivity associated with memory-related function | Invasive; cognitive benefits not yet fully quantified | 30 kHz sampling; 5–10 mm spacing; 0.1–1 kHz bandwidth; 500 Hz rate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; You, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, S. Multi-Level Perception Systems in Fusion of Lifeforms: Classification, Challenges and Future Conceptions. Sensors 2026, 26, 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020576

Zhang B, You X, Liu Y, Xu J, Xu S. Multi-Level Perception Systems in Fusion of Lifeforms: Classification, Challenges and Future Conceptions. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020576

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Bingao, Xinyan You, Yiding Liu, Jingjing Xu, and Shengyong Xu. 2026. "Multi-Level Perception Systems in Fusion of Lifeforms: Classification, Challenges and Future Conceptions" Sensors 26, no. 2: 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020576

APA StyleZhang, B., You, X., Liu, Y., Xu, J., & Xu, S. (2026). Multi-Level Perception Systems in Fusion of Lifeforms: Classification, Challenges and Future Conceptions. Sensors, 26(2), 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020576