Bioacoustic signals convey critical information about behavior, health, and interactions of living organisms with the environment [

1]. With recent advancements in AI, these signals have become increasingly important in applications such as ecological monitoring, medicine, and agriculture [

2]. A key challenge is the scarcity of event-specific sounds, where the acoustic signatures are essential for identifying and distinguishing particular biological events [

3]. Bioacoustic signals are comprised of unique characteristics, including temporal, spectral, and structural properties, which help to extract meaningful insights for real-world applications. There are various categories of bioacoustics; however, this study focuses explicitly on Bee Bioacoustics due to its vital significance in sustainable pollination, ecosystem health, and agricultural productivity.

Bee bioacoustics is particularly interesting because it helps to improve sustainable pollination, and that is fundamental for ensuring global food security [

2]. Recent studies have shown that bee bioacoustics can support efficient hive and behavioural management by detecting changes in sound patterns associated with stress, swarming, or queenlessness [

3]. Distinct acoustic signatures have been observed for key colony events such as queen presence, queen absence, and swarming, each carrying important implications for colony stability and productivity. For example, queen-less hives represent characteristic shifts in acoustic patterns that can be detected well before visual inspection, while swarming events generate specific pre-swarm signals that serve as early indicators for imminent colony reproduction and potential hive division [

4]. This represents bee bioacoustics as an active area of research, attracting attention across agriculture, AI, and environmental monitoring domains. This research focuses specifically on bee bioacoustics as a case study, due to its critical ecological and agricultural importance. However, analyzing bee Bioacoustic signals comes with unique technical challenges.

With recent advancements in AI and ML technologies, Bioacoustic signals are now being effectively analyzed and applied across a wide range of domains such as apiculture, wildlife conservation, medical diagnosis, and more [

2]. Developing robust machine learning models for bioacoustics analysis requires large volumes of clean, representative data, which is extremely challenging to obtain. Collecting sufficient high-quality bioacoustics signals is difficult due to contamination from environmental noise such as wind or water sounds, the labor-intensive nature of data collection, and the high associated costs [

5,

6,

7]. This scarcity of quality data presents a significant bottleneck for both research and practical deployment of bioacoustics systems. A key challenge is the scarcity of event-specific sounds, where the acoustic signature is essential for identifying and distinguishing particular biological events. These challenges are equally evident in Bee Bioacoustics, where data quality and sufficient data availability are critical factors for advancing research and applications in this field [

7].

1.1. Related Work and Comparison with Existing Methods

Synthetic bioacoustic data generation has gained increasing attention due to the critical challenges associated with collecting large, high-quality real-world recordings, particularly for ecologically sensitive species such as honeybees. Traditional data generation techniques such as rule-based [

8], random sampling [

8], statistical [

8] and parametric methods [

8] are often use explicit assumption about data distributions to generate synthetic data. They are most suited for simple and structured data with low variability. However, they are insufficient for modeling the complex spectral and temporal patterns inherent in bioacoustic signals.

As a result, machine learning–based generative models have emerged as a promising alternative [

3]. Compared to standard or traditional synthetic data generation approaches, ML-based approaches demonstrate great potential in capturing complex patterns and relationships in both structured and unstructured data [

8]. While conventional data generation approaches are limited to simple and structured data types, ML-based approaches have an enhanced ability to learn underlying distribution and complex relationships directly from real-world data to model them more accurately [

9]. Rather than relying solely on handcrafted rules or predefined statistical models, ML-based generative models can capture intricate interdependencies that standard techniques often overlook [

10]. Due to this capability, ML-based synthetic data generation approaches have made remarkable progress across multiple domains such as computer vision, speech generation, natural language processing, healthcare, finance, bioacoustics, and many others, where data diversity is crucial [

11]. Among ML models, Large Language Models (LLMs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Autoregressive models, and Diffusion models have been explored for audio and time-series synthesis.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are designed to model sequential token dependencies and semantic representations while learning contextual dependencies of text data [

12]. This design allows the model to capture semantic patterns with logical reasoning within a sequence and that makes it more effective for generating coherent and contextually accurate human-like text [

13]. LLMs can create artificial but useful data to enhance or replace small real-world datasets [

12]. Based on the research, the effectiveness of synthetic data generated by LLMs is negatively impacted by subjectivity, such as emotions and personal perspectives, and biases in training data [

14]. Although LLMs are highly effective in text generation, they are less suitable for handling unstructured or complex data such as images, audio, or bioacoustic data.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) consist of two feed-forward neural networks named the encoder and the decoder, which work together to learn the underlying distribution of the input data [

15]. The probabilistic modeling of latent variables allows the VAE to capture variability and uncertainty in the data, which enables the generation of diverse synthetic samples. VAEs are widely used in synthetic tabular data generation [

16] and image synthesis, although their performance is generally less effective [

17]. Despite the usages, one of the main drawbacks of VAEs is their high computational cost and longer processing time [

18]. VAEs are less effective in modeling complex data distributions and lack the ability to handle high-dimensional datasets such as images and audio effectively [

15]. Their usage in the bioacoustics domain is limited, which could be due to their difficulty in preserving fine details of audio data.

Autoregressive Models (ARMs) are made to produce data sequentially by predicting elements based on the previously generated elements through learned conditional dependencies of the input [

19]. This iterative process enables capturing sequential patterns in the input sequence effectively. ARMs have been successfully applied to generating sequential data such as time-series data, tabular data, audio sequences, images, and videos [

19]. Despite the benefits, ARMs have several limitations, including computational expense for long sequences, decreased output quality due to early prediction errors, and less realistic output compared to GAN-based models [

19]. These limitations make ARMs less suitable for high-fidelity audio generation, such as bioacoustics signals.

Diffusion Models (DMs) are based on iterative denoising diffusion processes, where the model gradually transforms structured data into noise and then reconstructs it back to realistic samples by reversing the noise process [

19]. This process helps to avoid issues such as mode collapse and generate quality outputs [

19]. Diffusion models have achieved remarkable success in generating high-dimensional, structured data, particularly in image synthesis, video generation, tabular data generation, and 3D modeling [

19,

20,

21]. While diffusion models have proven highly successful in visual and structured data domains, their usage for bioacoustic signal generation is impractical [

19].

However, these approaches present notable limitations in the bioacoustics domain. Consequently, these models are less practical for realistic bee bioacoustic signal synthesis. Hence we explored Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for synthetic data generation.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are the most powerful and widely used machine learning models for synthetic data generation, and they have become popular for generating both static and unstructured data, such as image data, tabular data, voice data, time-series data, financial-related data, and some bioacoustic signals. There are many improved versions of GANs, such as Conditional GAN (cGAN), Tabular GAN (TGAN), Conditional Tabular GAN (CTGAN) [

22], Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN), Multivariate Time series GAN (MTS-GAN), and many others that have been developed to enhance their performance for different applications [

8,

23]. High quality and flexibility are key advantages of GANs. They can produce realistic and reliable data while effectively modeling complex and high-dimensional data distributions such as images and audio [

8]. This breakthrough development of GANs has positively impacted various sectors such as entertainment, finance, healthcare, and research [

24]. For example, in healthcare, high-quality synthetic images help improve disease diagnosis, and in entertainment, synthetic music and sound generation improve content creation with advanced visual effects. Though there has been wide success in static data, such as image synthesis using GANs, there are only a few applications in audio data generation. In the bioacoustics domain, certain variants of GANs have been used for bee data classification, augmentation, and noise reduction [

25]. Their ability to model complex characteristics of bioacoustic signals have made them particularly suitable for data augmentation tasks [

25]. GANs can produce high-quality outputs and achieve good performance with high accuracy. However, GANs also present with several limitations, such as, training instability, mode collapse (limited diversity in data), longer training times with increased computational complexity and difficulty capturing temporal dependencies [

23].

Despite some limitations, the literature on synthetic data generation shows that GANs are more popular and powerful than other ML-based approaches. Given that this research focuses on bee bioacoustics, further exploration has been conducted on specific GAN variations, such as WaveGAN [

26], SpecGAN [

27], and StyleGAN [

28], which are specialized in audio and bioacoustic signal generation. WaveGAN is an extension of DCGAN designed for unsupervised generation of 1D raw audio waveforms [

27]. It is one of the earliest GAN-based approaches for audio synthesis. By directly modeling temporal audio signals, WaveGAN achieves stable training and produces high-quality, realistic audio at high speed, with successful applications in marine bioacoustics, bird sounds, and creative multimedia. However, it struggles to preserve dynamic behavior over time and is limited to short output durations. In contrast, spectrogram-based GAN models (SpecGAN and StyleGAN) represent audio as 2D time–frequency images and they provide more stable training and effective learning of spectral structures, particularly for music, speech, and whale vocalization synthesis [

28]. Despite these advantages, such models are computationally expensive, fail to capture fine-grained long-term temporal dependencies, and suffer information loss during spectrogram-to-waveform reconstruction.

To address temporal modeling limitations in standard GANs and their variations, hybrid approaches combining GANs with probabilistic sequential models have been explored. Markov Chain Generative Adversarial Networks (MCGANs) integrate the adversarial learning capability of GANs with the probabilistic transition modeling of Markov Chains. Such models have demonstrated improved stability and temporal consistency in domains including physics, multivariate time-series synthesis, agriculture, and medical diagnostics. The Markov property [

29] enables effective modeling of sequential dependencies by conditioning each generated state on the previous one, thereby preserving dynamic behavior that standard GANs often fail to capture.

1.2. Problem Formulation and Summary of Contribution

The fundamental problem addressed in this study spans multiple domains–bioacoustics, signal processing, probabilistic modeling, and machine learning. Bee colonies display event-specific acoustic patterns that reflect internal hive states such as the queen bee’s presence or absence. These acoustic patterns are temporally structured and impacted by environmental and behavioural dynamics, hence it is challenging to model them using conventional deterministic approaches.

From a signal processing standpoint, bee bioacoustic signals can be modeled as time-domain signals with event-dependent spectral and temporal features within a limited frequency range. However, there are issues with data scarcity and class imbalance that impede robust statistical learning because real-world recordings are frequently scarce, tainted by noise, and unevenly distributed across events.

From a machine learning perspective, the task can be formulated as learning an underlying probability distribution that governs event-specific bee acoustic signals, such that new samples drawn from this distribution preserve both global spectral properties and local temporal dynamics. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), particularly WaveGAN, provide a data-driven mechanism for learning high-dimensional waveform distributions directly from raw audio and synthesize them. However, standard GAN-based approaches do not support to preserve temporal dependency constraints that are critical for biological signal realism.

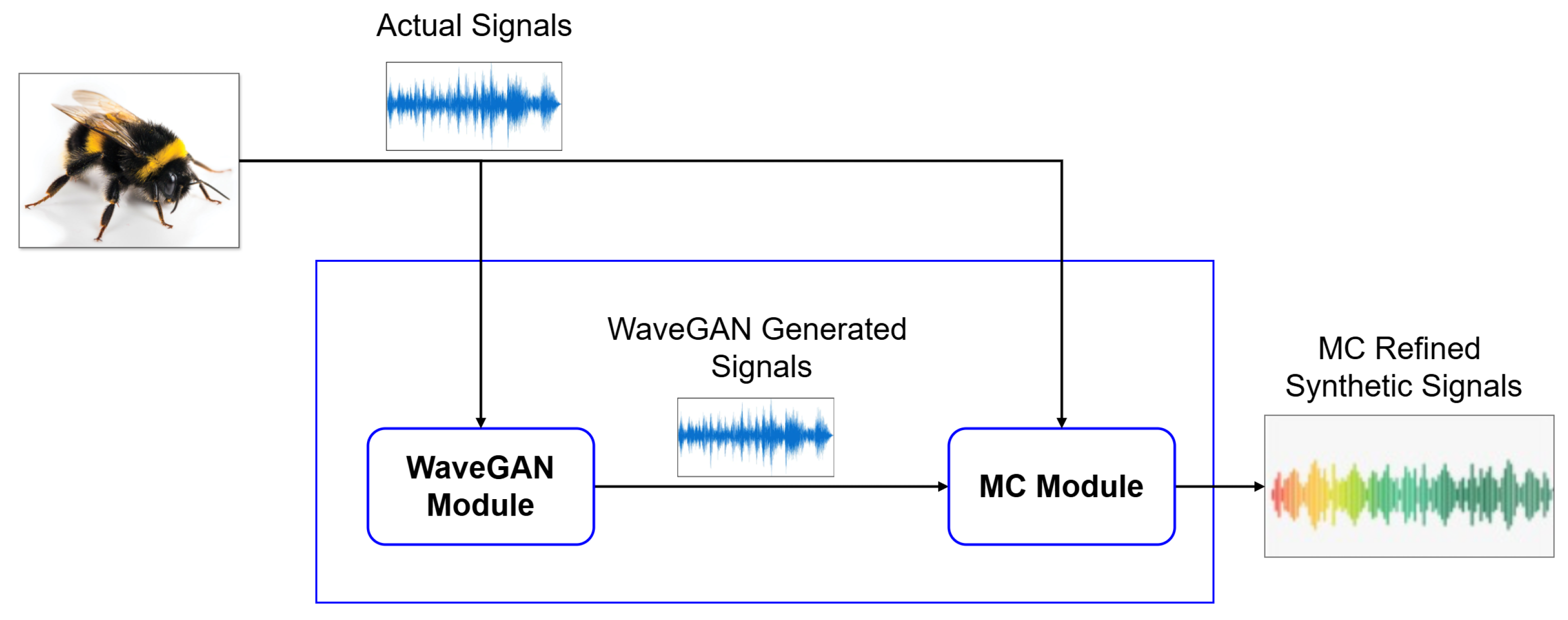

To address the limitations of existing synthetic data generation methods in bee bioacoustics, this study explores the integration of Markov Chains (MC) as a refinement stage based on Markov Chain theory. The refinement process formulates synthetic signal generation as a stochastic transition process, where each generated signal evolves toward the target real-data distribution through probabilistic acceptance governed by the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm. This MC process helps us to synthesize event-specific Bioacoustic signals generated by a specialized GAN variant, WaveGAN. MC is a well-established mathematical framework widely used in predictive modeling [

30]. It has also been successfully integrated with GANs to better handle high-dimensional data and produce more realistic and reliable outputs [

29,

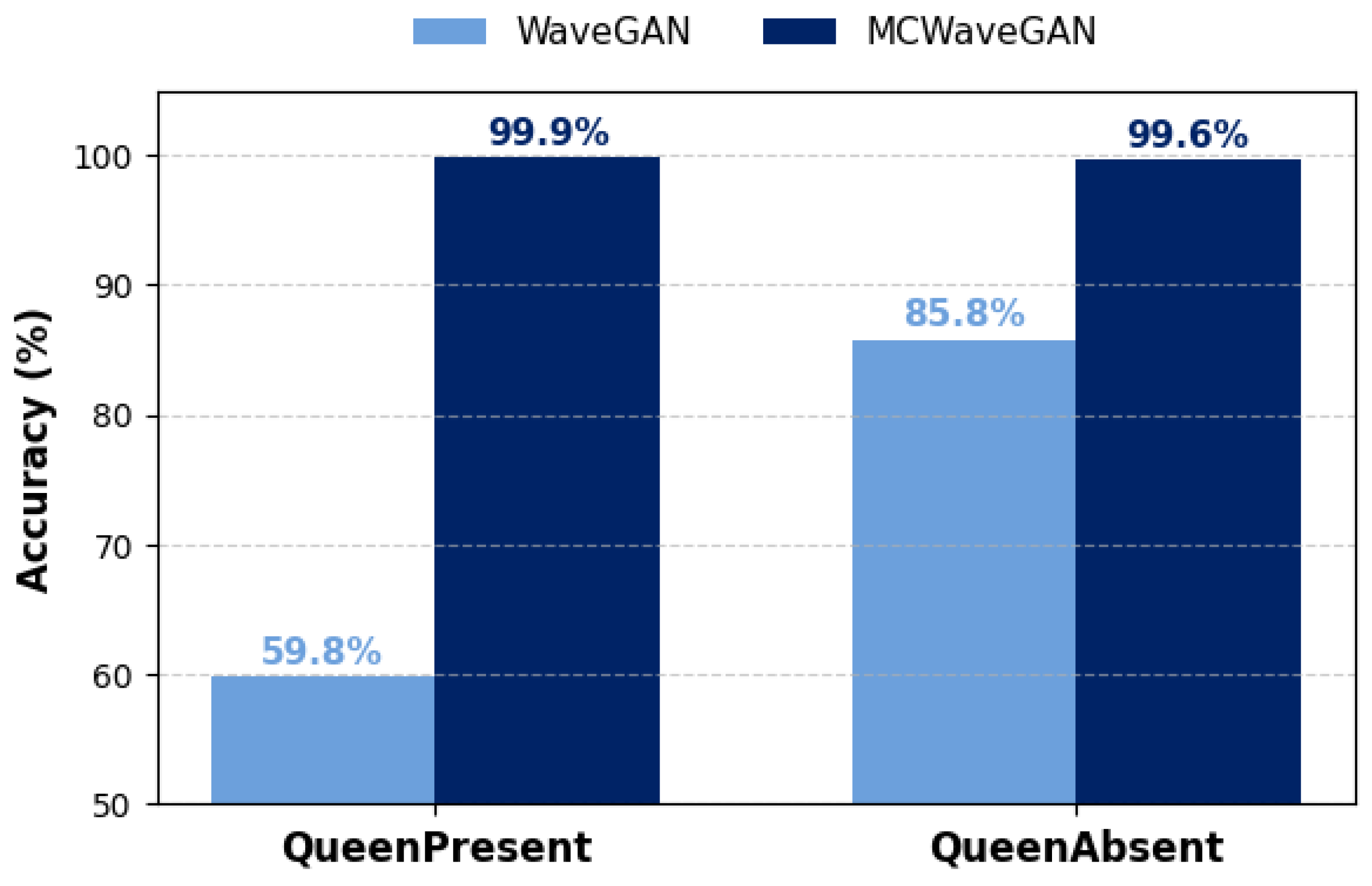

31]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the integration of MC with the WaveGAN approach remains underexplored in the context of Bee Bioacoustic signal generation. In this work, we aim to bridge this gap by addressing the challenges posed by limited high-quality datasets in real-world bee bioacoustics intelligence applications. Overall, considering the motivation outlined above, this study proposes a novel hybrid framework, termed MCWaveGAN, which extends the conventional WaveGAN architecture by introducing a Markov Chain-based refinement stage implemented via the Metropolis–Hastings algorithm to generate synthetic bee bioacoustic signals. Through this approach, this research focuses on addressing one of the main challenges of Bee Bioacoustics research and applications; the lack of quality and sufficient real-world data by generating synthetic signals. Unlike prior GAN-based audio synthesis approaches, the proposed method explicitly enforces temporal coherence and spectral consistency by probabilistically refining generated signals toward the distribution of real bee bioacoustic features. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to apply Markov Chain refinement to WaveGAN for event-specific bee bioacoustic signal generation, enabling significantly improved realism and downstream classification performance.

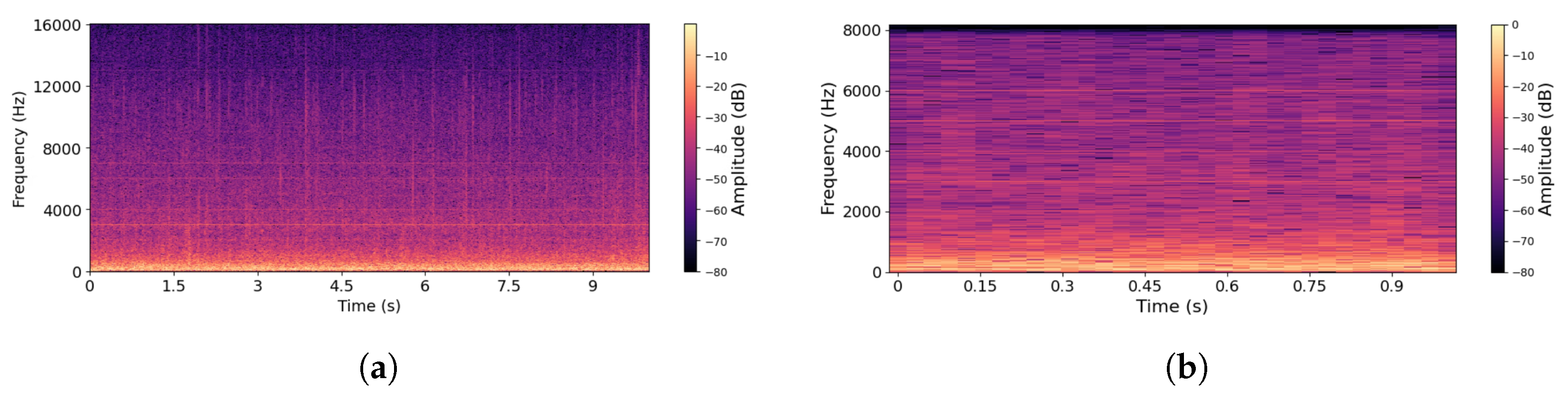

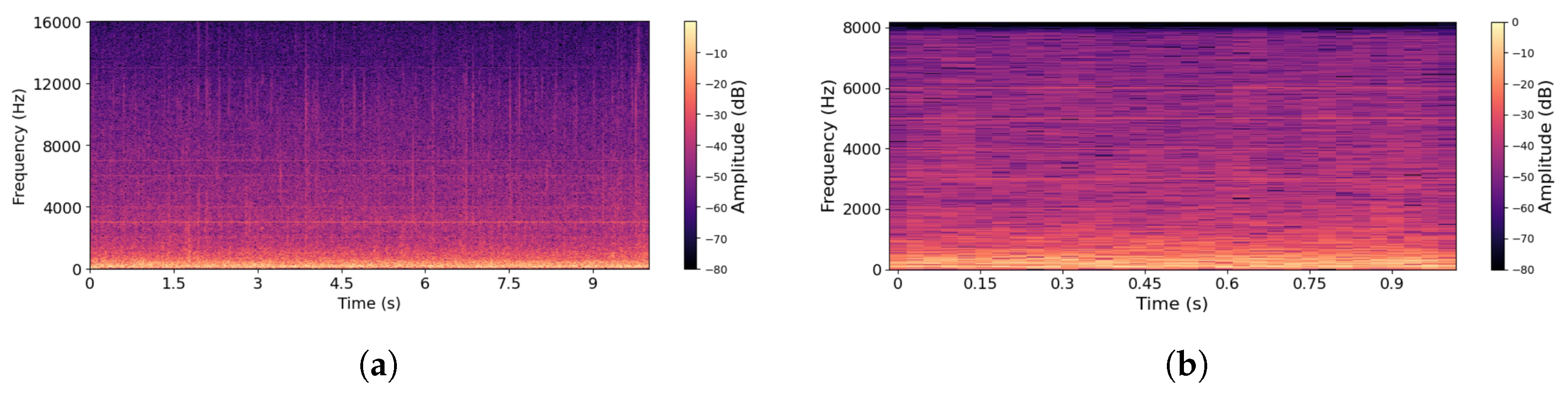

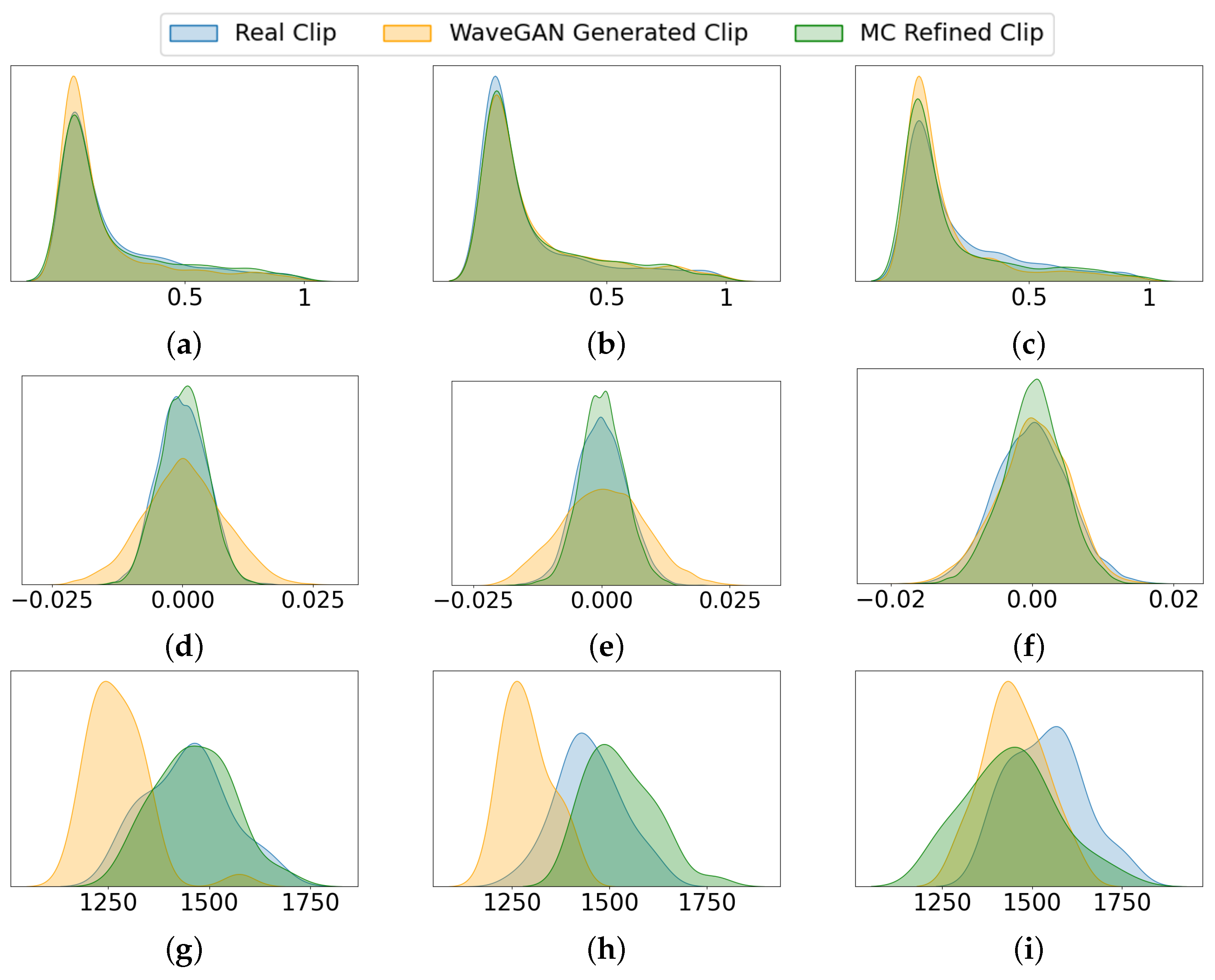

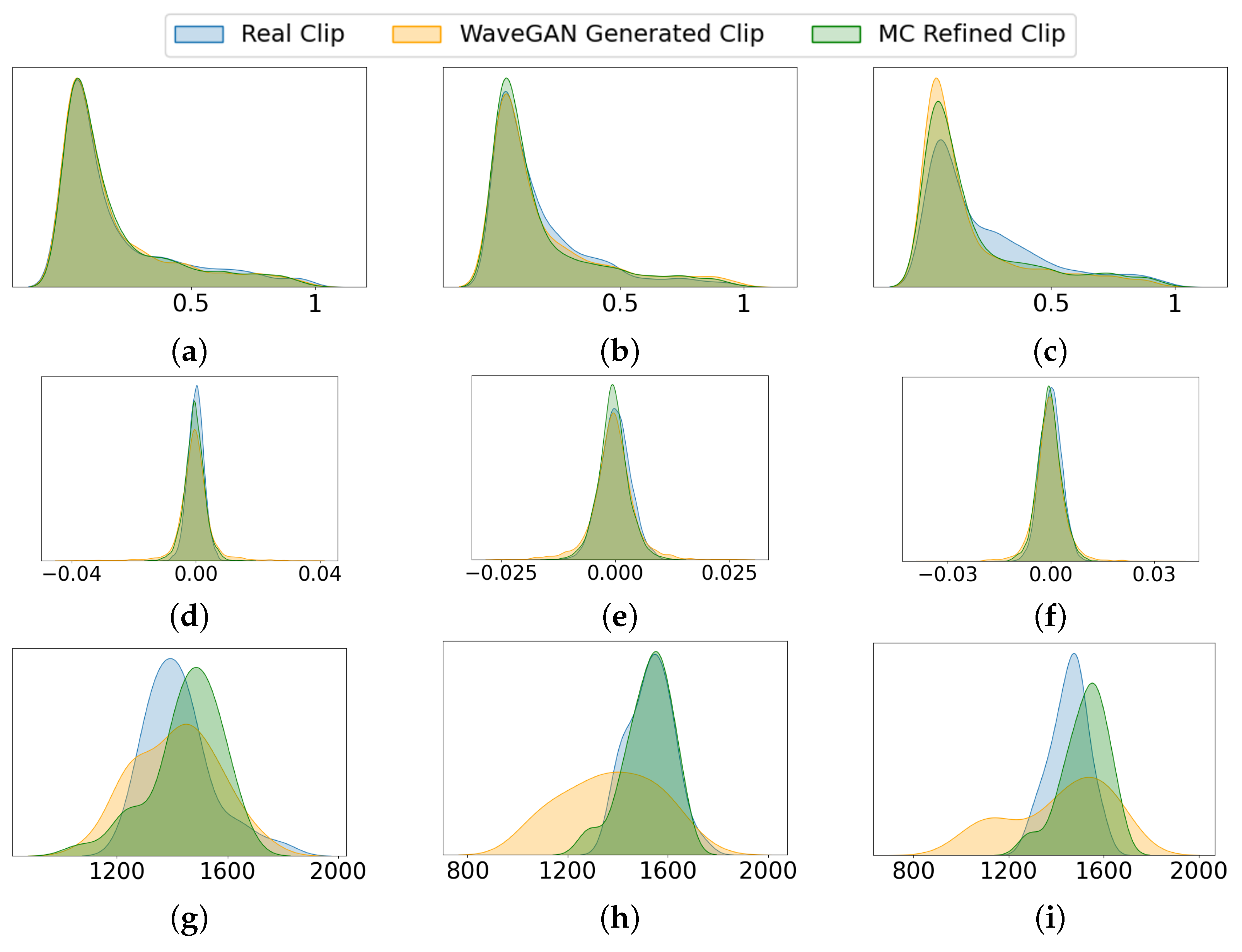

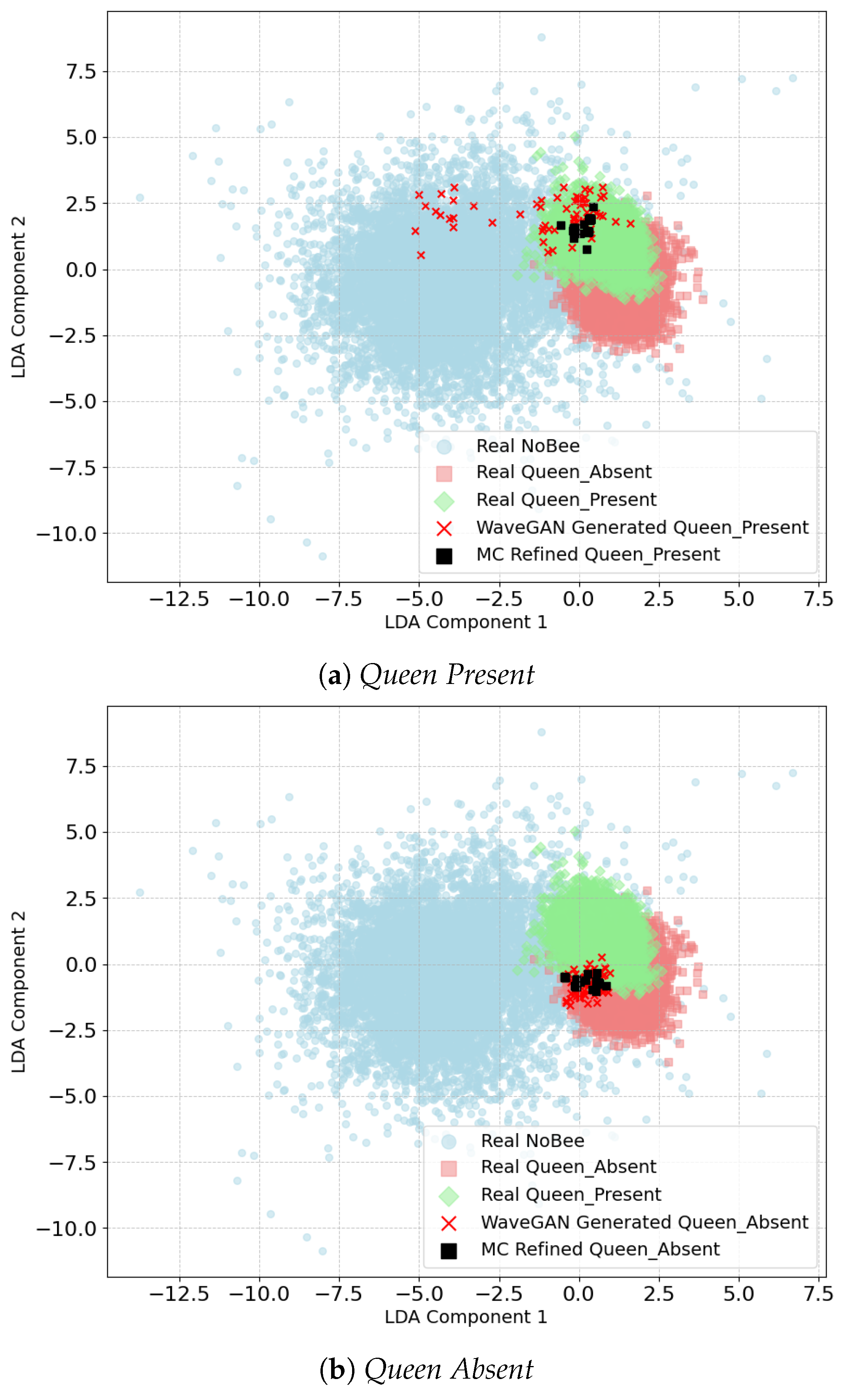

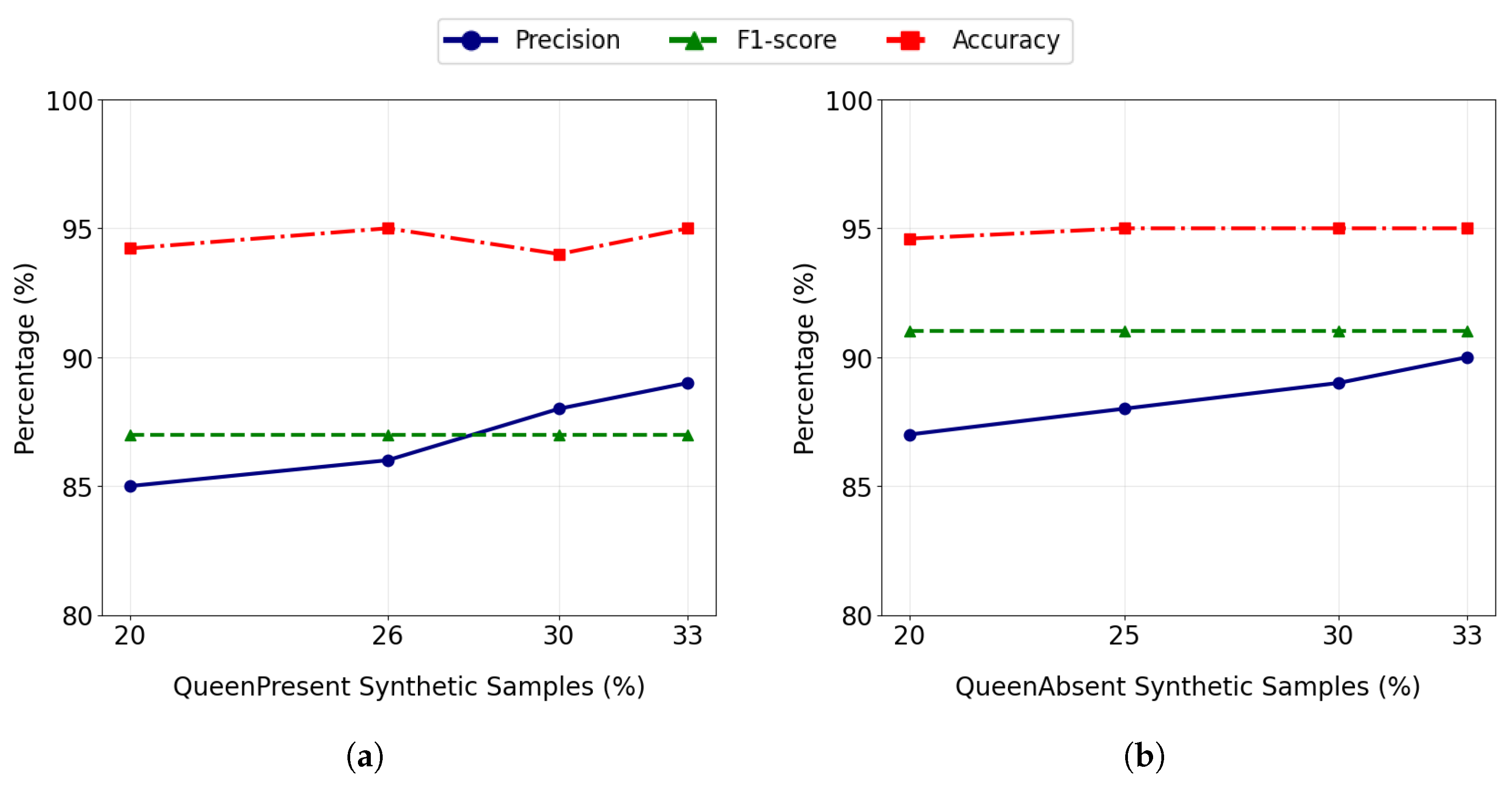

In this research, we design and develop a robust generative framework for synthetic bee bioacoustic signal generation by integrating WaveGAN with a Markov Chain–based refinement process. The proposed model aims to synthesize realistic, event-specific bee acoustic signals by effectively capturing both spectral characteristics and temporal dynamics inherent in real hive recordings. Using the developed framework, a synthetic bee bioacoustic signal dataset is produced and systematically evaluated to assess its realism and utility. The validation is conducted through quantitative measures, including classification performance using real test data, as well as qualitative analyses. These qualitative evaluations focus on spectral and statistical similarity between the generated synthetic signals and real bee sounds, ensuring that the synthesized data closely reflects the acoustic properties of natural bee bioacoustic events.