Unsupervised Neural Beamforming for Uplink MU-SIMO in 3GPP-Compliant Wireless Channels †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

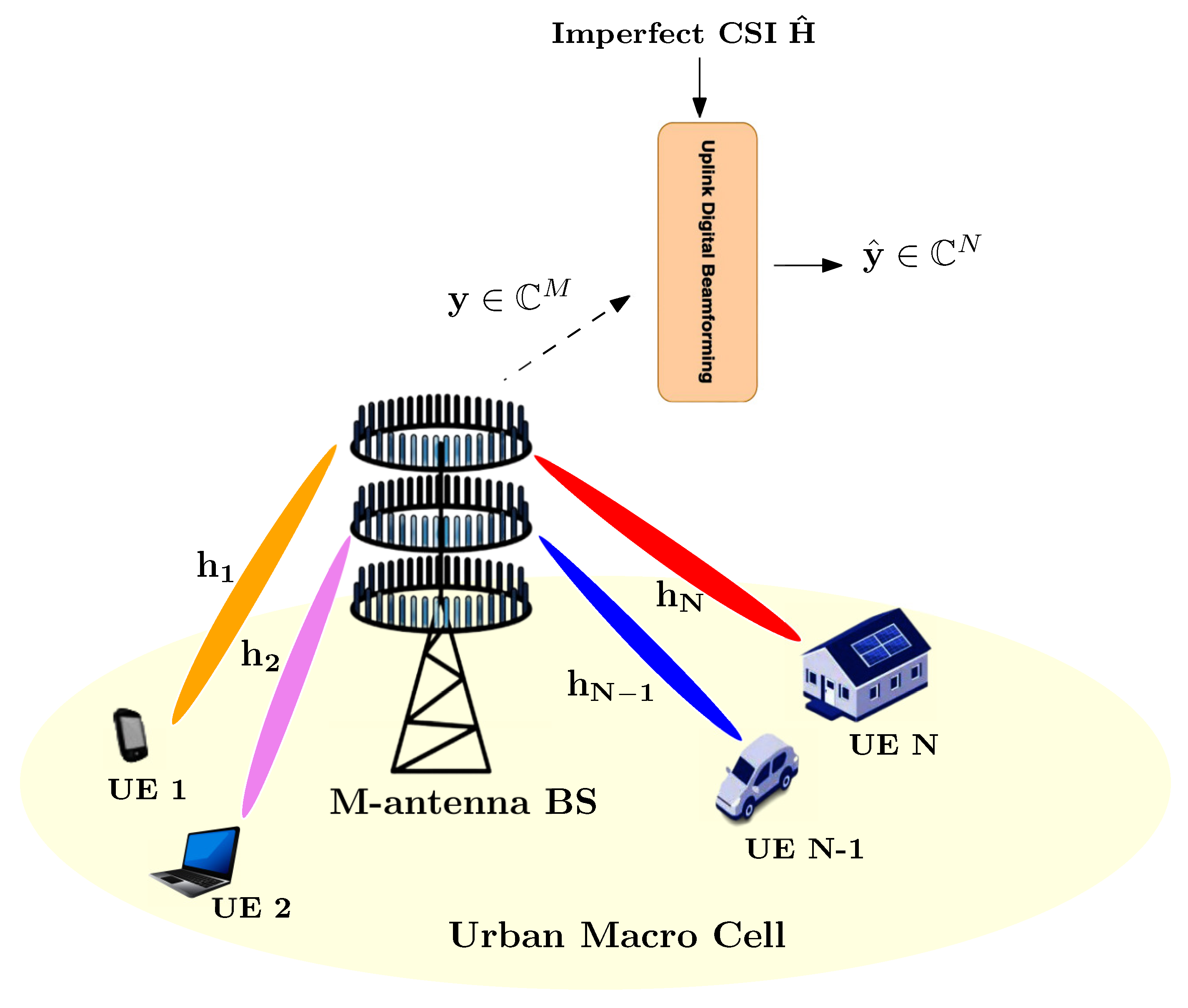

2.1. Uplink Multi-User SIMO (MU-SIMO) Setup

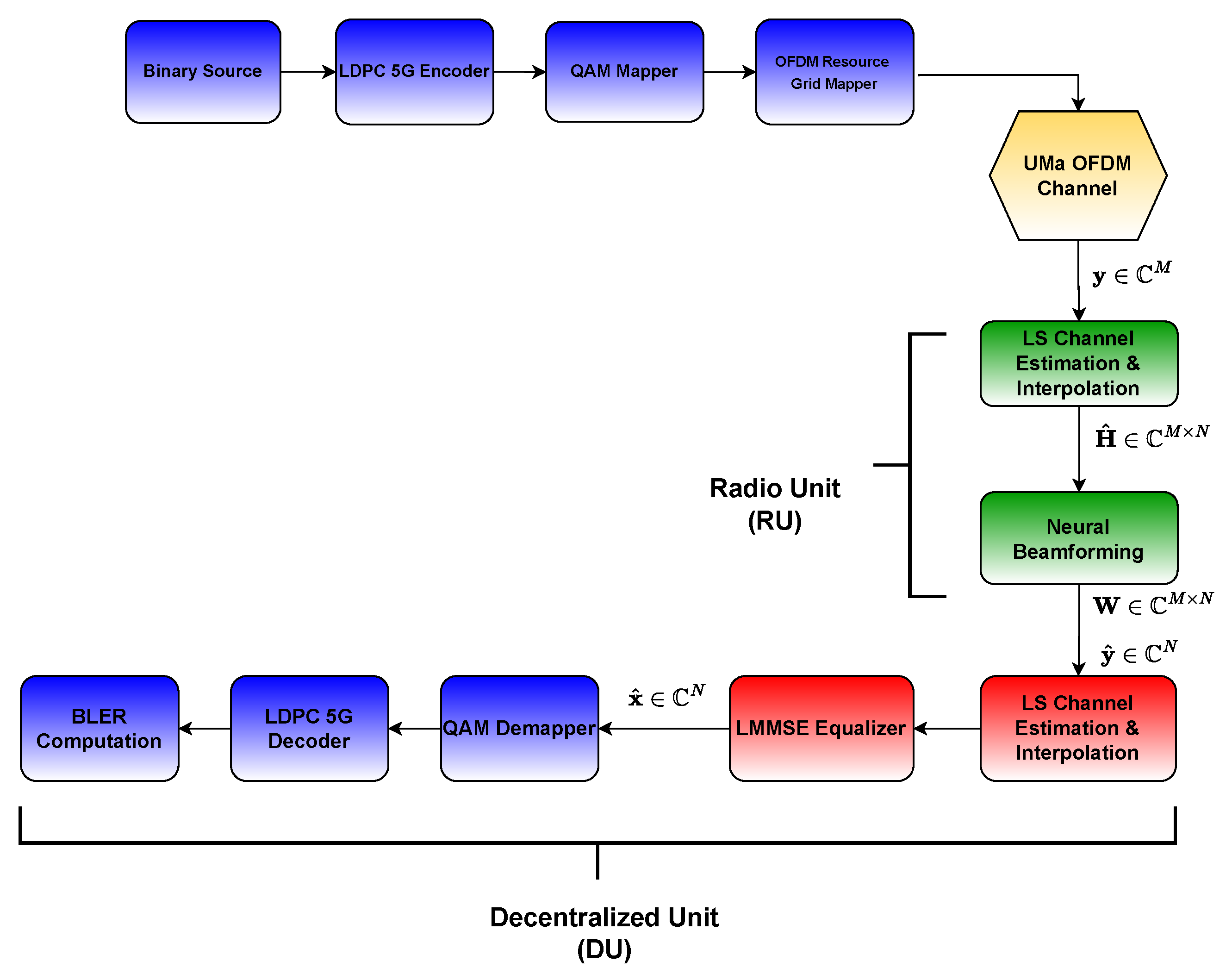

2.2. Uplink Performance Improvement in O-RAN

2.3. Beamforming Design for Sum-Rate Maximization

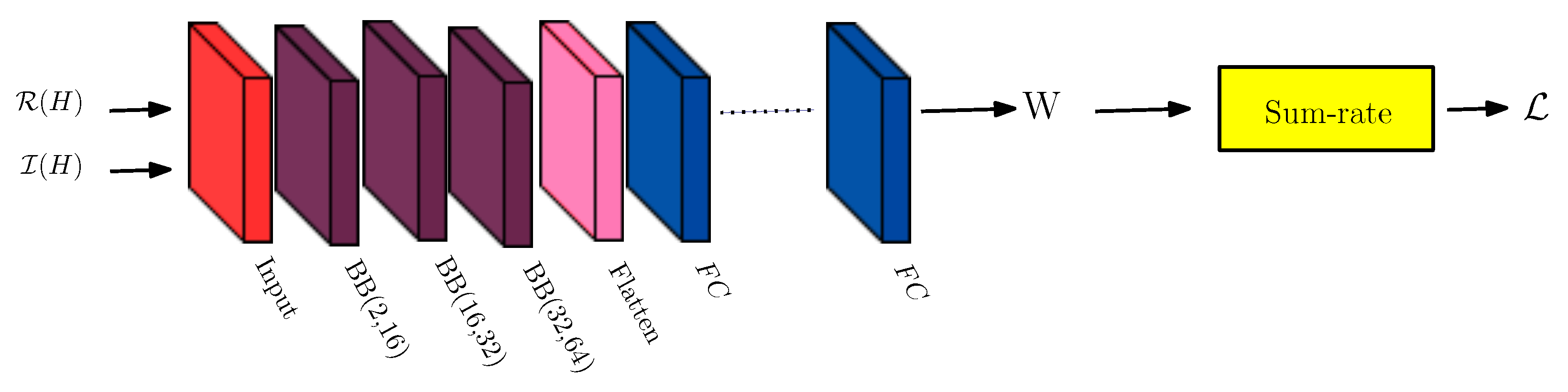

3. Proposed Deep Neural Networks

- The simple NNBF architecture is intended for scenarios with perfect or near-perfect CSI. It assumes a tapped delay line (TDL) channel model and is well-suited for settings with stationary UEs and negligible Doppler shift. This architecture utilizes accurate channel information to learn beamforming weights in a computationally efficient way using a lightweight structure.

- The transformer-based NNBF architecture targets more realistic and challenging scenarios involving imperfect CSI and is assessed using the UMa channel model. It is especially appropriate for challenging deployment environments, including those with high user mobility and significant Doppler spread. By incorporating attention mechanisms, the architecture captures long-range dependencies across OFDM symbols and subcarriers, enabling robust beamforming performance in complex and dynamic environments.

3.1. Simple NNBF Architecture

3.2. Transformer-Based NNBF Architecture

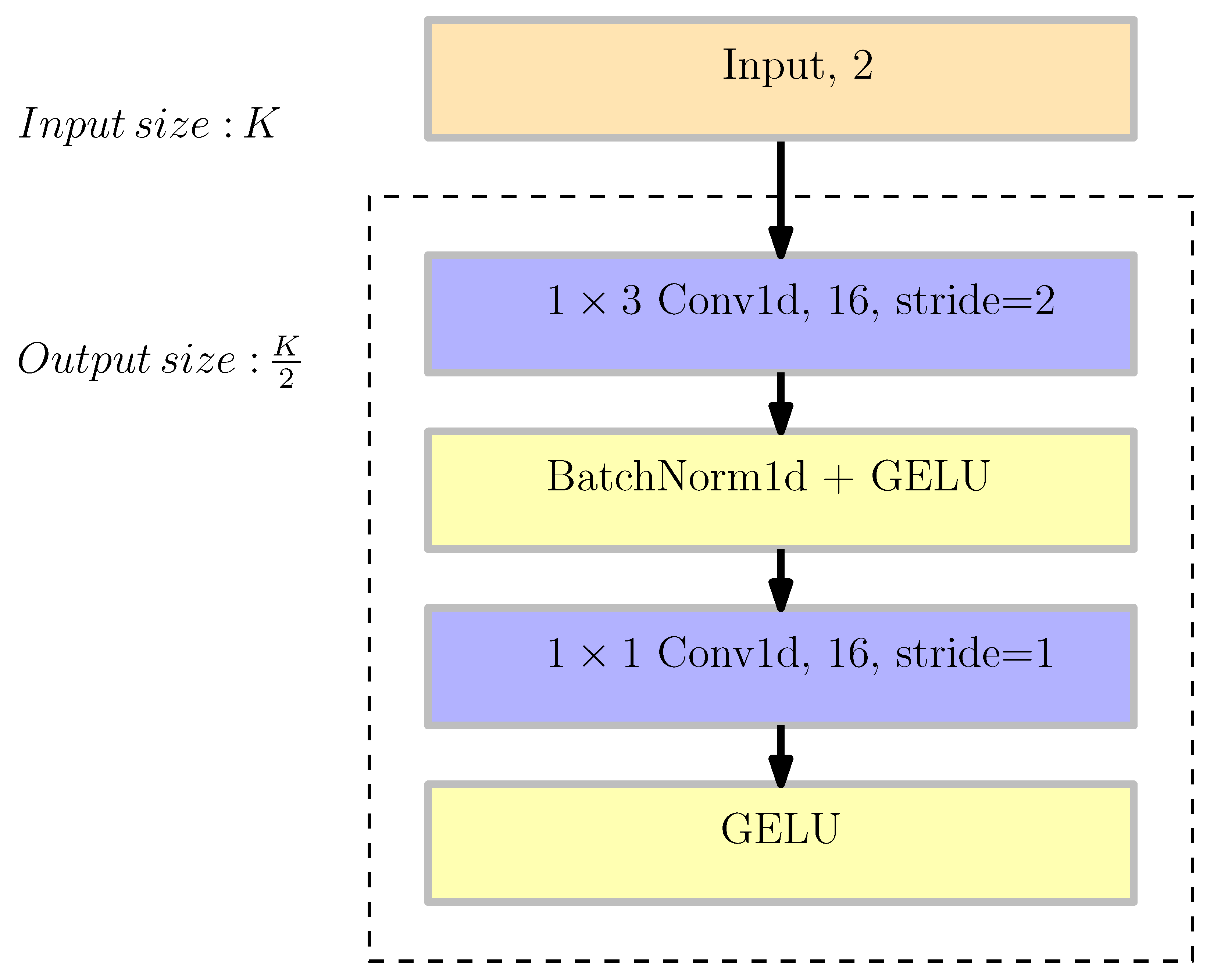

3.2.1. ConvolutionalResidual Network

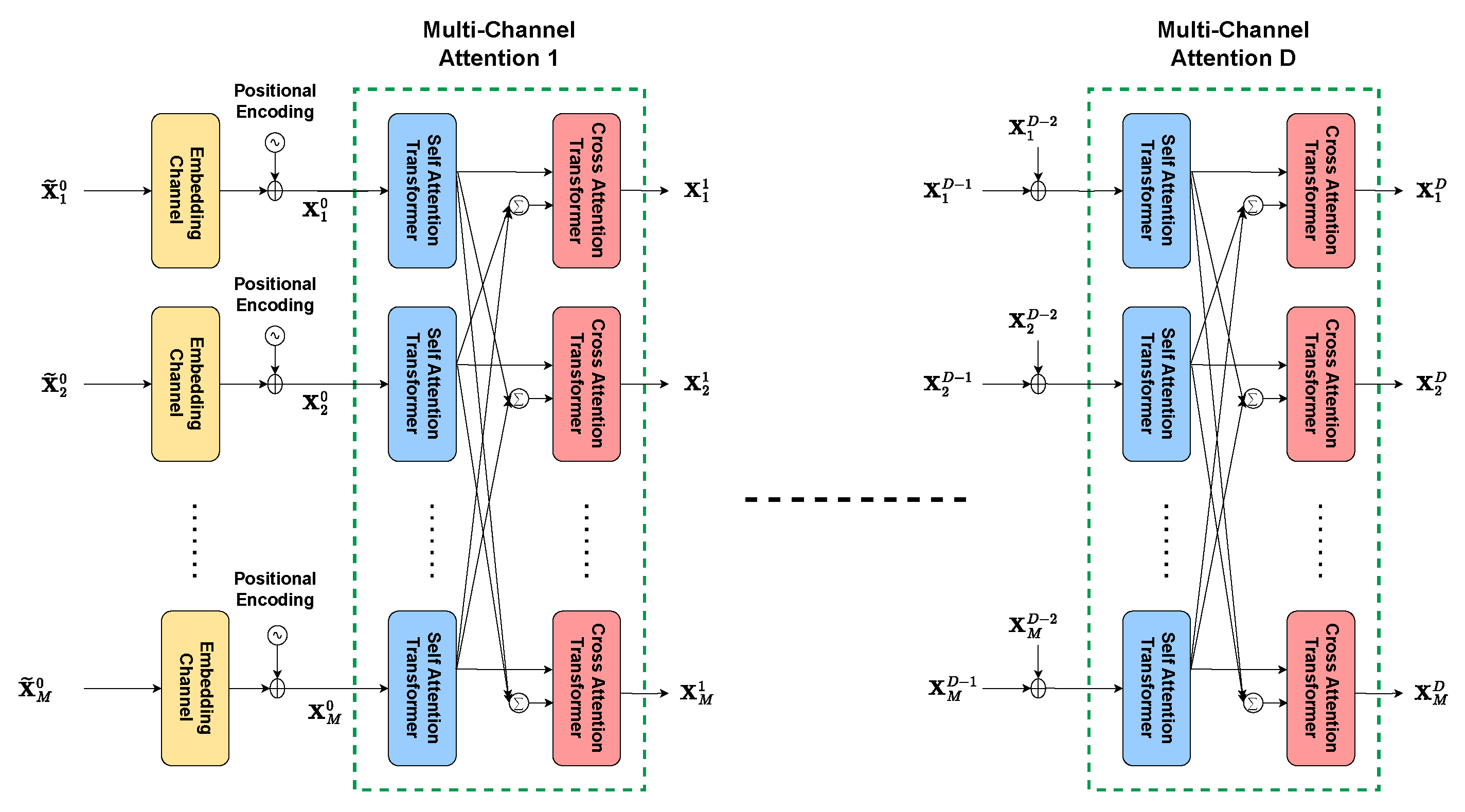

3.2.2. Stacked Multi-Channel Attention

3.3. Training Procedure

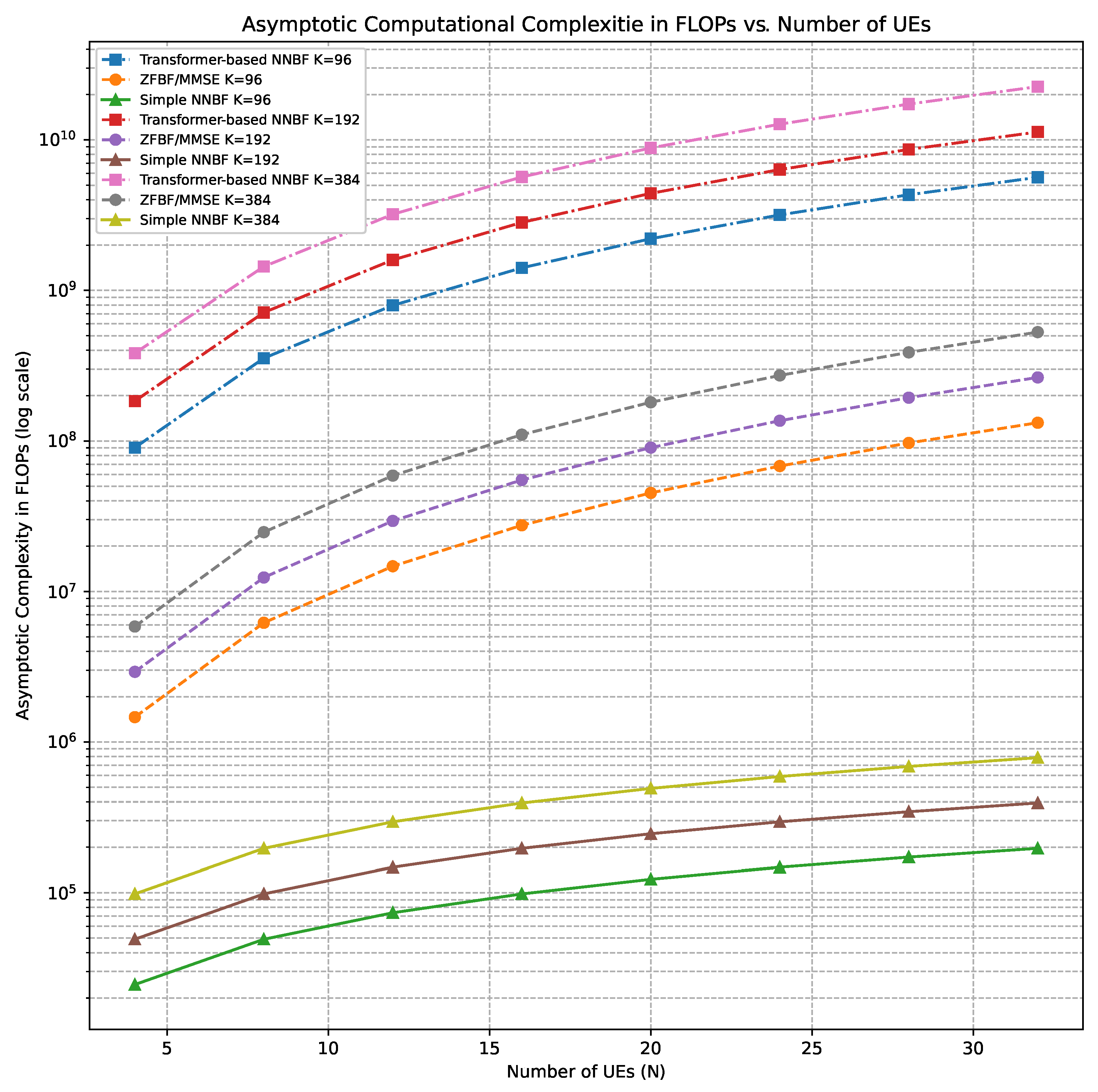

4. Complexity Analysis

4.1. Preliminaries

4.1.1. Standard Convolution

4.1.2. Grouped Convolutions

4.1.3. Batch Normalization and GELU Activation

4.2. Baseline Techniques

- Computation of the matrix , which requires ;

- Matrix inversion of the resulting matrix, with complexity ;

- Multiplying the result of step 2 by , again contributing to .

4.3. Simple NNBF

4.4. Transformer-Based NNBF

4.4.1. Convolutional Residual Network

4.4.2. Stacked Multi-Channel Attention Module

Positional Encoding

Embedding Layer

Self Attention Transformer

Cross Attention Transformer

Multi-Channel Attention

4.5. Summary of Complexity Analysis

- The pointwise convolution in the convolutional residual network, which incurs a complexity of , resulting from quadratic scaling with the number of antennas;

- The scaled dot-product attention and the subsequent multiplication of attention scores with values introduce a complexity of , indicating quadratic growth in the OFDM grid size.

5. Experiments

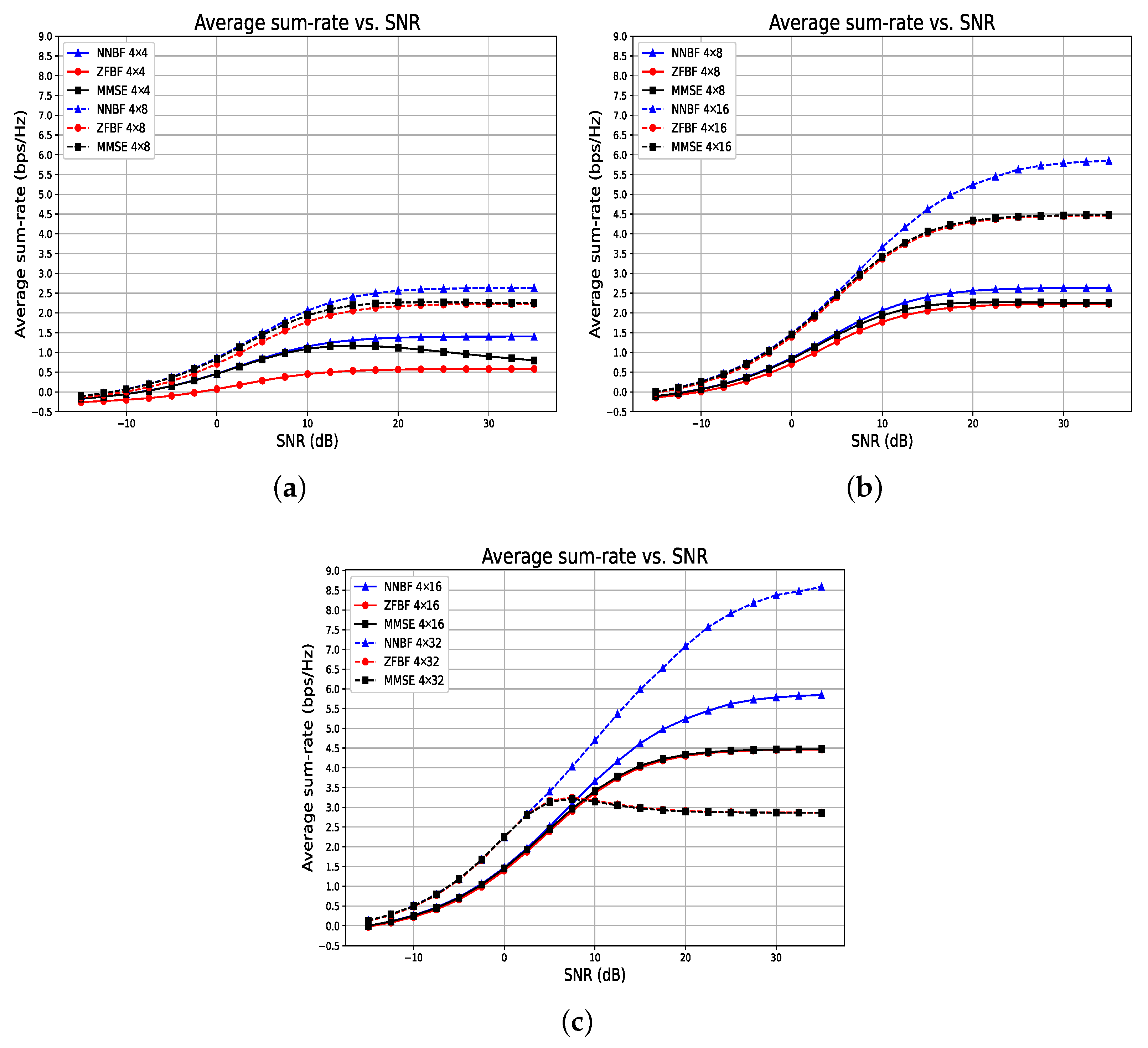

5.1. Experiments with Simple NNBF Architecture

5.1.1. System and Dataset Specifications

5.1.2. Model and Training Details

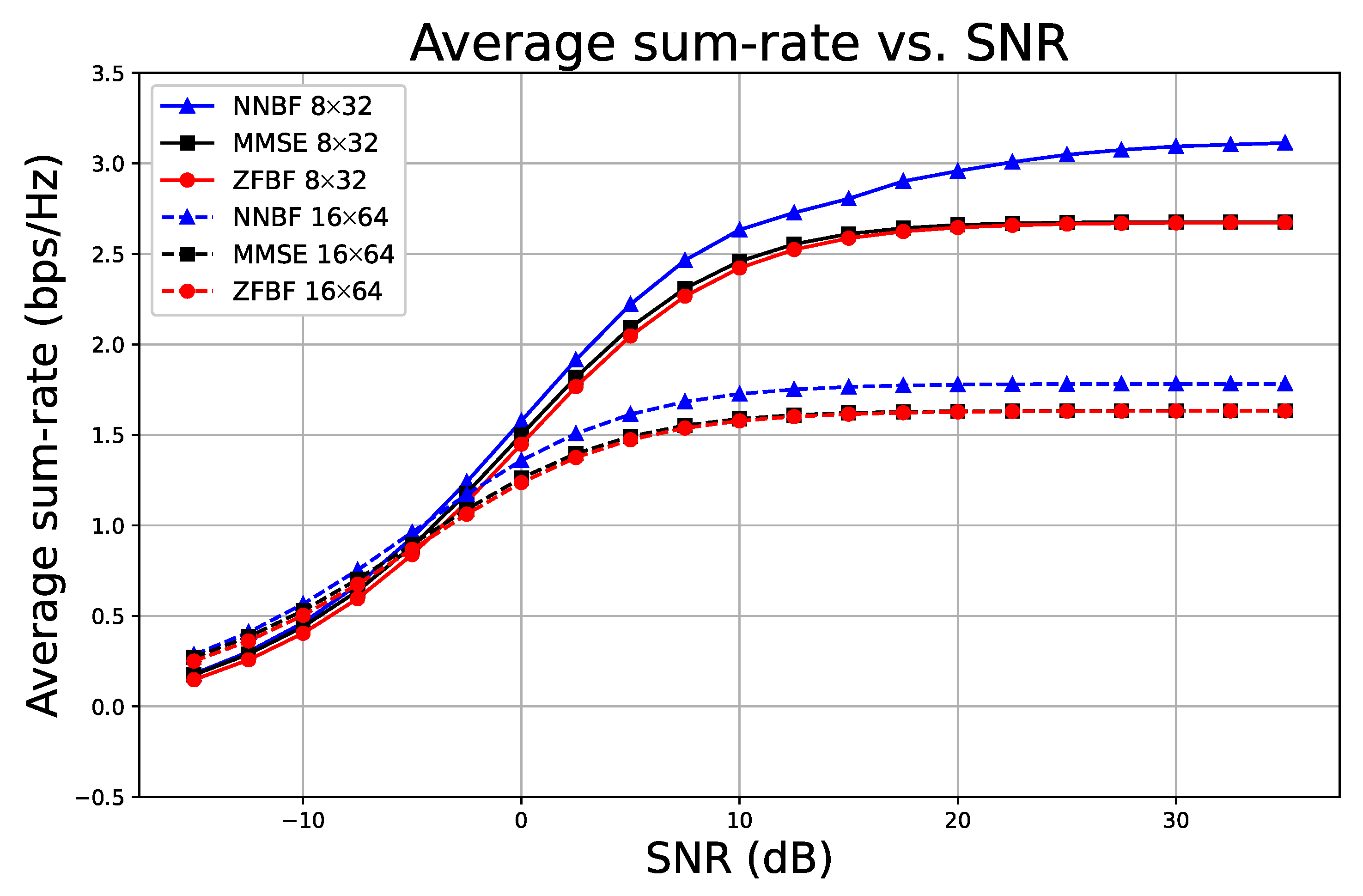

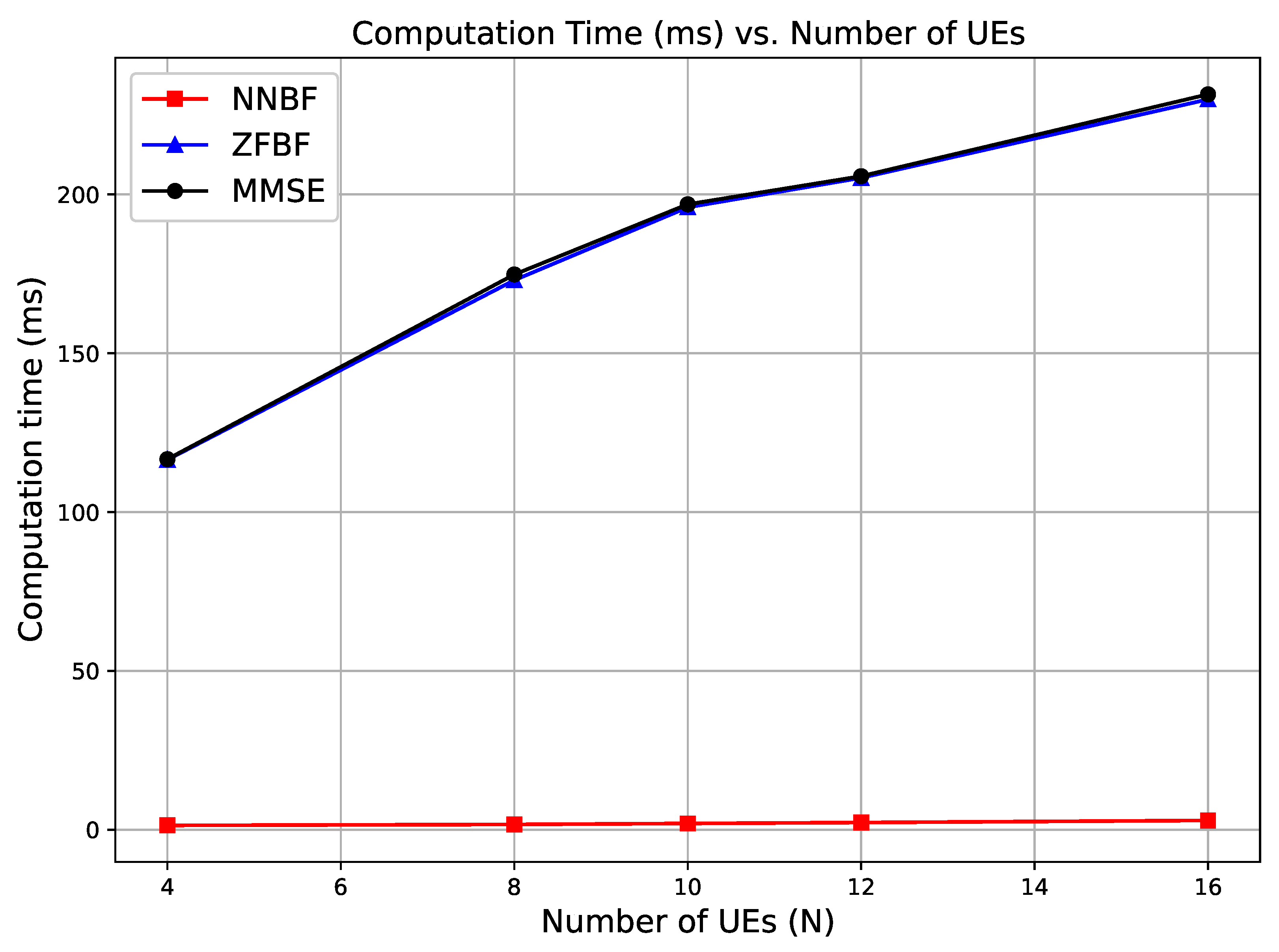

5.1.3. Results and Analysis for Simple NNBF

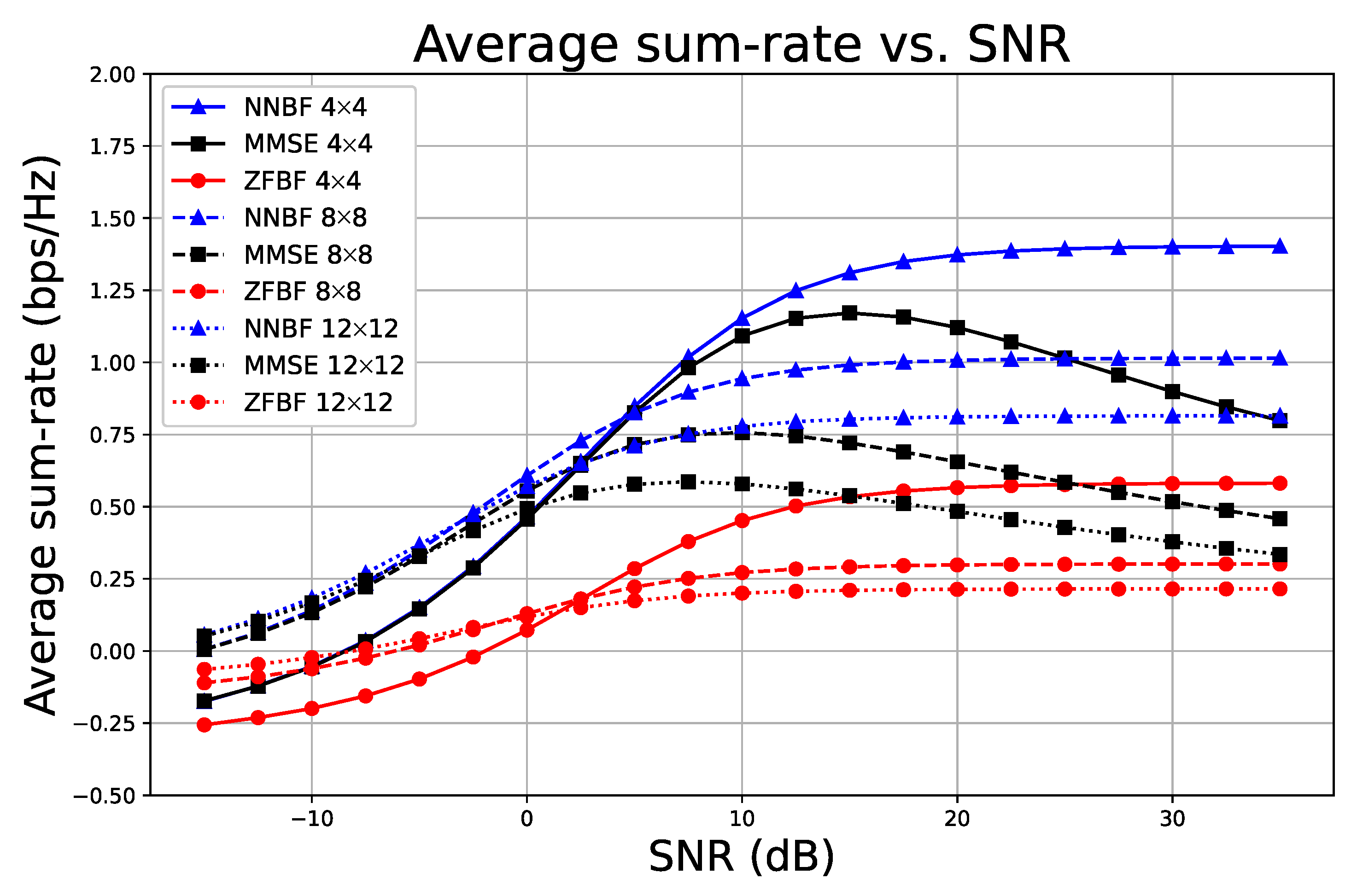

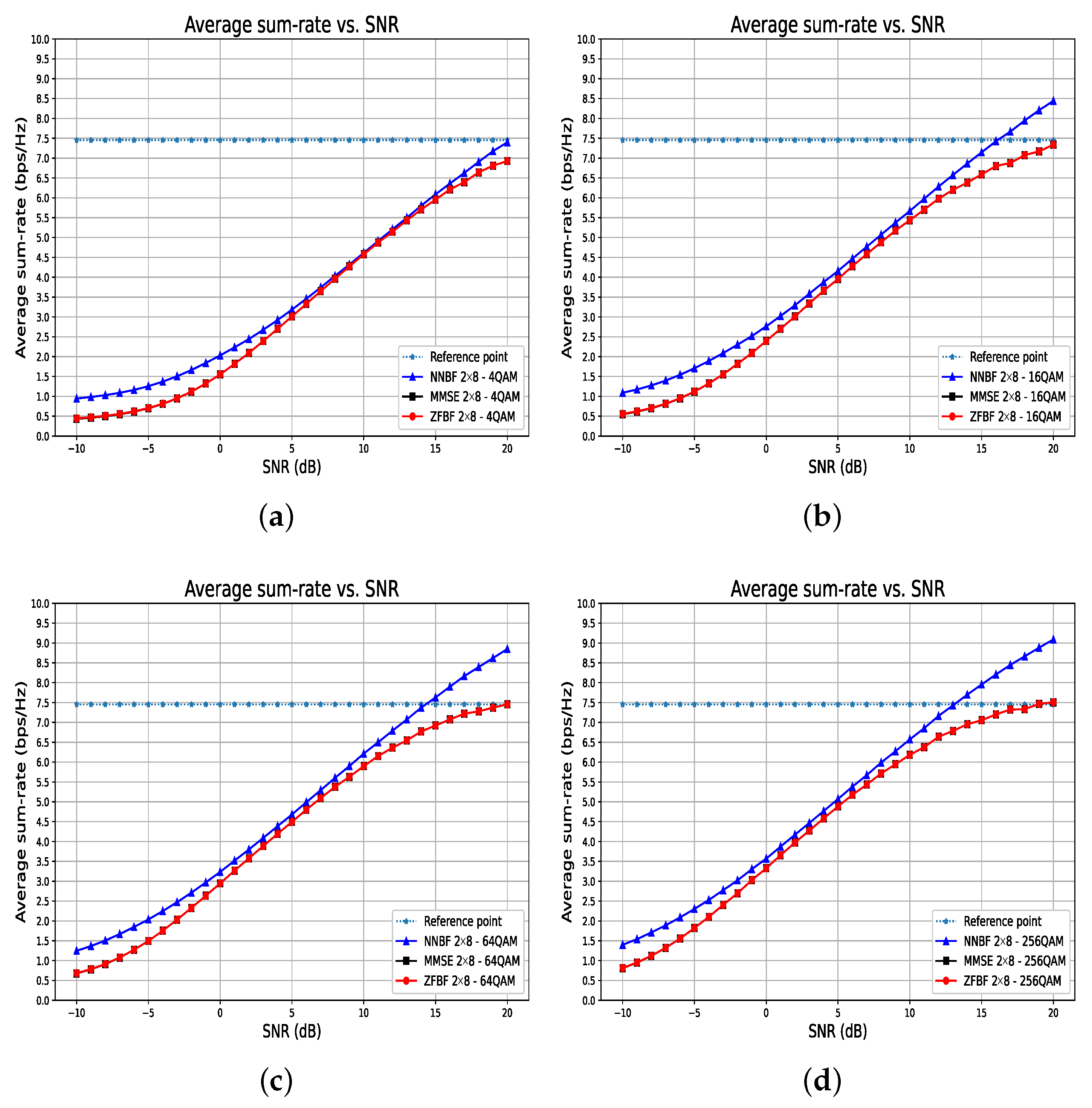

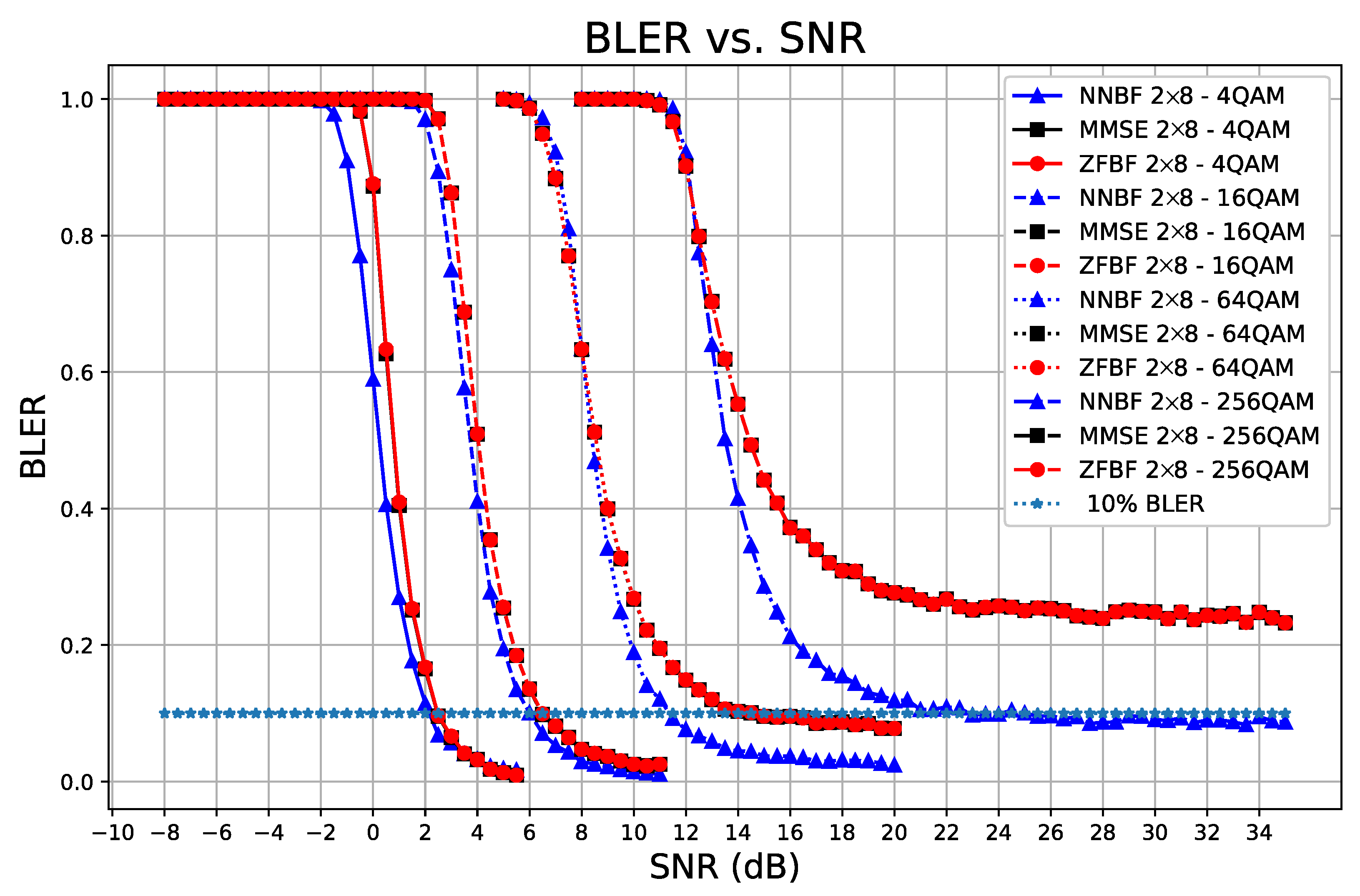

5.2. Experiments with Transformer-Based NNBF Architecture

5.2.1. System and Training Specifications

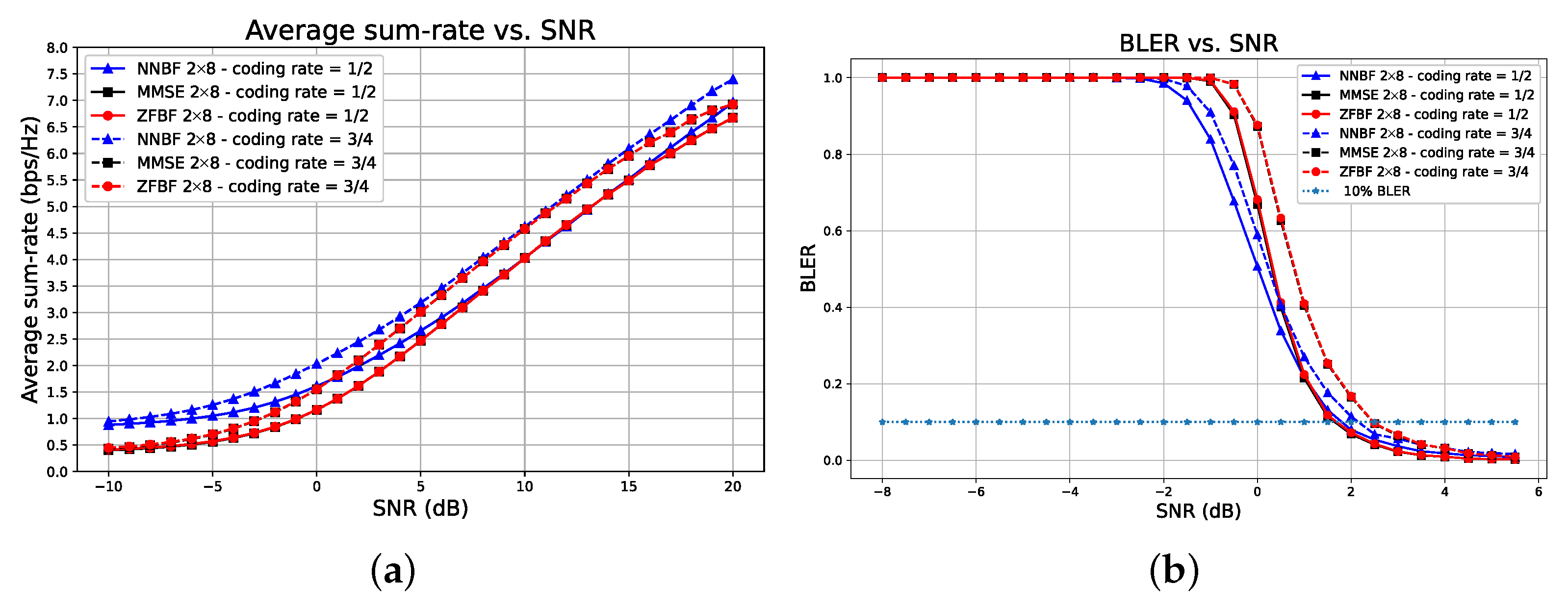

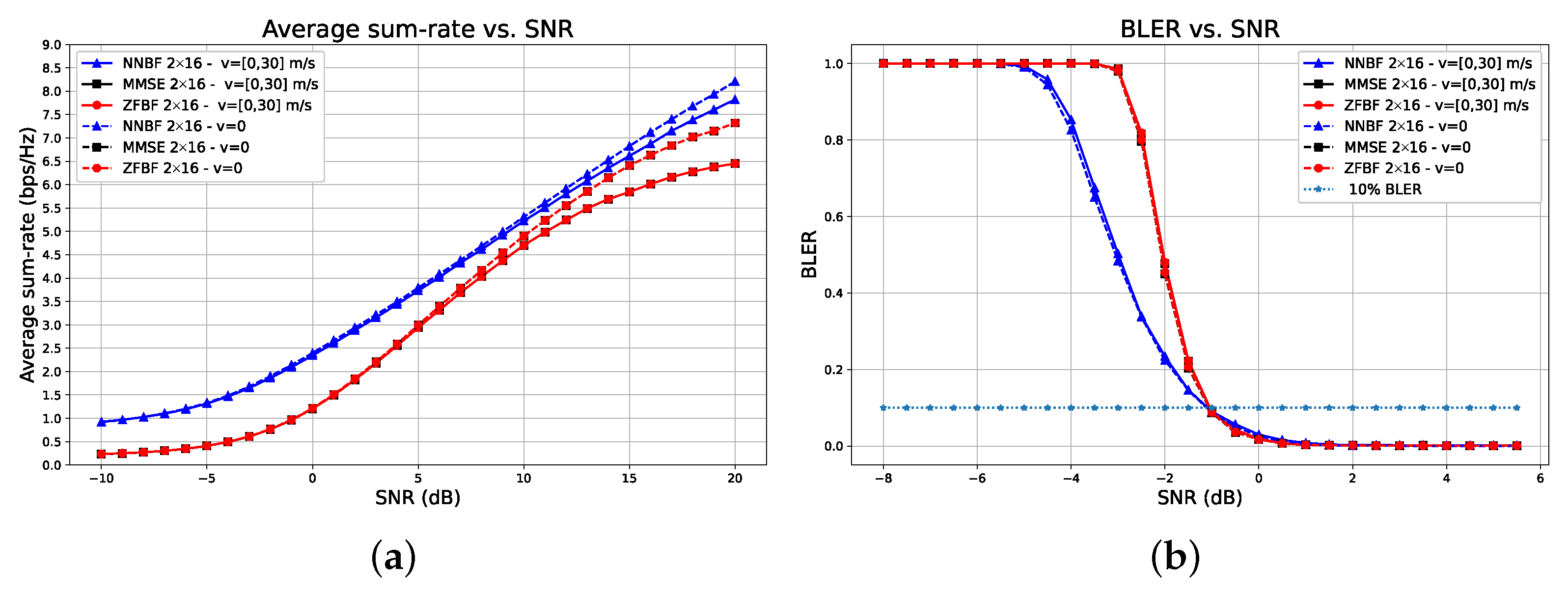

5.2.2. Results and Analysis for Transformer-Based NNBF

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Björnson, E.; Hoydis, J.; Sanguinetti, L. Massive MIMO networks: Spectral, energy, and hardware efficiency. Found. Trends Signal Process. 2017, 11, 154–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Q.; Swindlehurst, A.; Haardt, M. Zero-forcing methods for downlink spatial multiplexing in multiuser MIMO channels. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2004, 52, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnson, E.; Bengtsson, M.; Ottersten, B. Optimal Multiuser Transmit Beamforming: A Difficult Problem with a Simple Solution Structure [Lecture Notes]. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2014, 31, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire, G.; Shamai, S. On the achievable throughput of a multiantenna Gaussian broadcast channel. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2003, 49, 1691–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Gupta, A.; Mishra, H.; Budhiraja, R. Low-Complexity ZF/MMSE MIMO-OTFS Receivers for High-Speed Vehicular Communication. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2022, 3, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeesi, O.; Gokceoglu, A.; Zou, Y.; Björnson, E.; Valkama, M. Performance Analysis of Multi-User Massive MIMO Downlink Under Channel Non-Reciprocity and Imperfect CSI. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2018, 66, 2456–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiessl, S.; Gross, J.; Skoglund, M.; Caire, G. Delay Performance of the Multiuser MISO Downlink Under Imperfect CSI and Finite-Length Coding. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2019, 37, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.; Shin, O. Performance Analysis of ZF Receivers with Imperfect CSI for Uplink Massive MIMO Systems. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.03150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Razaviyayn, M.; Luo, Z.; He, C. An iteratively weighted MMSE approach to distributed sum-utility maximization for a MIMO interfering broadcast channel. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2011, 59, 4331–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.; Agarwal, R.; de Carvalho, E.; Cioffi, J. Weighted sum-rate maximization using weighted MMSE for MIMO-BC beamforming design. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2008, 7, 4792–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erpek, T.; O’Shea, T.J.; Sagduyu, Y.E.; Shi, Y.; Clancy, T.C. Deep Learning for Wireless Communications. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.06068. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, C.; Hecker, J.; Stuntebeck, E.; O’Shea, T. Applications of Machine Learning to Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2007, 14, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.; Hoydis, J. An Introduction to Deep Learning for the Physical Layer. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2017, 3, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Peng, M.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Mao, S. Application of Machine Learning in Wireless Networks: Key Techniques and Open Issues. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 3072–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbir, A.M. A deep learning framework for hybrid beamforming without instantaneous CSI feedback. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 11743–11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Shi, Q.; Hong, M.; Fu, X.; Sidiropoulos, N.D. Learning to Optimize: Training Deep Neural Networks for Interference Management. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2018, 66, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, J.; Korpi, D.; Honkala, M. DeepTx: Deep Learning Beamforming with Channel Prediction. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 1855–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zheng, G.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Petropulu, A. A Deep Learning Framework for Optimization of MISO Downlink Beamforming. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2020, 68, 1866–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnson, E.; Jorswieck, E. Optimal Resource Allocation in Coordinated Multi-Cell Systems. Found. Trends Commun. Inf. Theory 2013, 9, 113–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Krikidis, I.; Wong, K. Deep Learning Based Predictive Beamforming Design. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 8122–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xia, W.; Xiong, J.; Yang, J.; Zheng, G.; Zhu, X. Unsupervised Learning-Based Fast Beamforming Design for Downlink MIMO. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 7599–7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, J.R.; Roux, J.L.; Weninger, F. Deep Unfolding: Model-Based Inspiration of Novel Deep Architectures. arXiv 2014, arXiv:21409.2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, K.; LeCun, Y. Learning Fast Approximations of Sparse Coding. In Proceedings of the ICML, Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, N.; Diskin, T.; Wiesel, A. Deep MIMO Detection. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.01151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahapoglu, C.; O’Shea, T.J.; Roy, T.; Ulukus, S. Deep Learning Based Uplink Multi-User SIMO Beamforming Design. In Proceedings of the ICMLCN, Stockholm, Sweden, 5–8 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vahapoglu, C.; O’Shea, T.J.; Liu, W.; Roy, T.; Ulukus, S. Transformer-Driven Neural Beamforming with Imperfect CSI in Urban Macro Wireless Channels. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications, Istanbul, Turkey, 1–4 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- 3GPP. Study on Channel Model for Frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz; Technical Report TR 38.901, 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP); Version 17.0.0; 3GPP: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Network decoupling: From regular to depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the BMVC, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 3–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Pietro, G.D.; Coronato, A. Application of reinforcement learning and deep learning in multiple-input and multiple-output MIMO systems. Sensors 2021, 22, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, D.; Thompson, J. Attention Based Neural Networks for Wireless Channel Estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE VTC, Helsinki, Finland, 19–22 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, L.; Jin, S.; Chen, W.; Poor, H.V. Decision Transformers for Wireless Communications: A New Paradigm of Resource Management. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2025, 32, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dong, P. Mixed Attention Transformer Enhanced Channel Estimation for Extremely Large-Scale MIMO Systems. In Proceedings of the WCSP, Hefei, China, 24–26 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Cheng, N.; Sun, R.; Wang, X.; Lu, N.; Xu, W. SigT: An Efficient End-to-End MIMO-OFDM Receiver Framework Based on Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09712. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Lv, J.; Zhou, T. A Transformer-Based Channel Estimation Method for OTFS Systems. Entropy 2023, 25, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP. Study on New Radio Access Technology: Radio Access Architecture and Interfaces; Technical Report TR 38.801; v14.0.0; 3GPP: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O-RAN Fronthaul Control, User and Synchronization Plane Specification; Technical Report ORAN.WG4.CUS.0-v07.02; O-RAN WG4 CUS Specification v7.02; O-RAN Alliance: Alfter, Germany, 2023.

- Hendrycks, D.; Gimpel, K. Gaussian Error Linear Units (GELUs). arXiv 2017, arXiv:1606.08415. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICLR, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.; Radfar, M.; Mouchtaris, A.; King, B.; Kunzmann, S. End-to-End Multi-Channel Transformer for Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICASSP, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hoydis, J.; Cammerer, S.; Ait Aoudia, F.; Vem, A.; Binder, N.; Marcus, G.; Keller, A. Sionna: An Open-Source Library for Next-Generation Physical Layer Research. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.11854. [Google Scholar]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A Next-generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the KDD, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Function | Cat-A | Cat-B | ULPI-A | ULPI-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Prefix Removal | O-RU | O-RU | O-RU | O-RU |

| FFT | O-RU | O-RU | O-RU | O-RU |

| Channel Estimation | O-DU | O-RU | O-DU | O-RU |

| Uplink Beamforming | O-DU | O-RU | O-DU | O-RU |

| Equalization | O-DU | O-DU (optional) | O-DU | Optional (O-RU or O-DU) |

| Compression | Optional | Optional | Enhanced | Enhanced |

| Output to O-DU | Antenna-domain IQ | Beamformed UE streams | Compressed IQ | Beamformed or demodulated UE streams |

| RU Complexity | Low | High | Medium | Very High |

| Fronthaul Bandwidth | High | Reduced | Lower | Minimal |

| Latency Requirement | Strict | Relaxed | Relaxed | Most Relaxed |

| Technique | Complexity |

|---|---|

| ZFBF | |

| MMSE | |

| Transformer-based NNBF | |

| Simple NNBF |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Channel delay profile | TDL-A |

| Number of resource blocks (RBs) | 4 (48 subcarriers) |

| Delay spread | 30 ns |

| Maximum Doppler shift | 10 Hz |

| Subcarrier spacing | 30 kHz |

| Transmission time interval (TTI) | 500 s |

| SNR | [−15, 35] dB |

| Modulation scheme | QPSK |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of resource blocks (RBs) | 4 (48 subcarriers) |

| Maximum Doppler shift | 260 Hz |

| Maximum UE velocity v | 30 m/s |

| Carrier frequency | 2.6 GHz |

| Subcarrier spacing | 30 kHz |

| Transmission time interval (TTI) | 500 s |

| Coding rate | , |

| Modulation scheme | 4QAM, 16QAM, 64QAM, 256QAM |

| Training SNR | [−10, 20] dB |

| Learning rate | |

| 0.5 | |

| k | 13 |

| Minimum training SNR ranges | [15, 20], [10, 15], [5, 10], [0, 5], [−10, 0] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vahapoglu, C.; O’Shea, T.J.; Liu, W.; Roy, T.; Ulukus, S. Unsupervised Neural Beamforming for Uplink MU-SIMO in 3GPP-Compliant Wireless Channels. Sensors 2026, 26, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020366

Vahapoglu C, O’Shea TJ, Liu W, Roy T, Ulukus S. Unsupervised Neural Beamforming for Uplink MU-SIMO in 3GPP-Compliant Wireless Channels. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020366

Chicago/Turabian StyleVahapoglu, Cemil, Timothy J. O’Shea, Wan Liu, Tamoghna Roy, and Sennur Ulukus. 2026. "Unsupervised Neural Beamforming for Uplink MU-SIMO in 3GPP-Compliant Wireless Channels" Sensors 26, no. 2: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020366

APA StyleVahapoglu, C., O’Shea, T. J., Liu, W., Roy, T., & Ulukus, S. (2026). Unsupervised Neural Beamforming for Uplink MU-SIMO in 3GPP-Compliant Wireless Channels. Sensors, 26(2), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020366