Performance Analysis of Explainable Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for IoT Networks: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contributions

- (i)

- To comprehensively analyze the performance trade-offs associated with integrating different XAI techniques into deep learning-based IDSs for IoT networks by evaluating the impact of these techniques on key performance indicators.

- (ii)

- To identify and compare the performance characteristics of various explainable deep learning architectures applied to IDSs in IoT by evaluating the detection accuracy and resource efficiency of these models.

- (iii)

- To examine the effectiveness and reliability of XAI techniques after deployment by reporting on the evaluation methods utilized for XAI techniques within the IoT security context.

- (iv)

- To develop two conceptual frameworks: the XAI evaluation framework and the Unified Explainable IDS Evaluation Framework (UXIEF). The former is aimed at standardizing evaluation categories for XAI while the latter visually models the fundamental tensions between detection performance, resource efficiency, and explanation quality in IoT IDSs.

- (v)

- To identify critical limitations and challenges hindering the widespread adoption of explainable deep learning-based IDSs in IoT deployment by synthesizing evidence from the literature on such factors.

2. Related Works

2.1. Reviews on IDSs for IoT

2.2. Surveys on Explainable AI for Security

2.3. Studies on Explainable DL-Based IDSs

2.4. Summary of Related Work and Research Gaps

3. Overview of Relevant Concepts

3.1. Deep Learning Models for IDSs

3.1.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

3.1.2. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

3.1.3. Autoencoder

3.1.4. Transformers

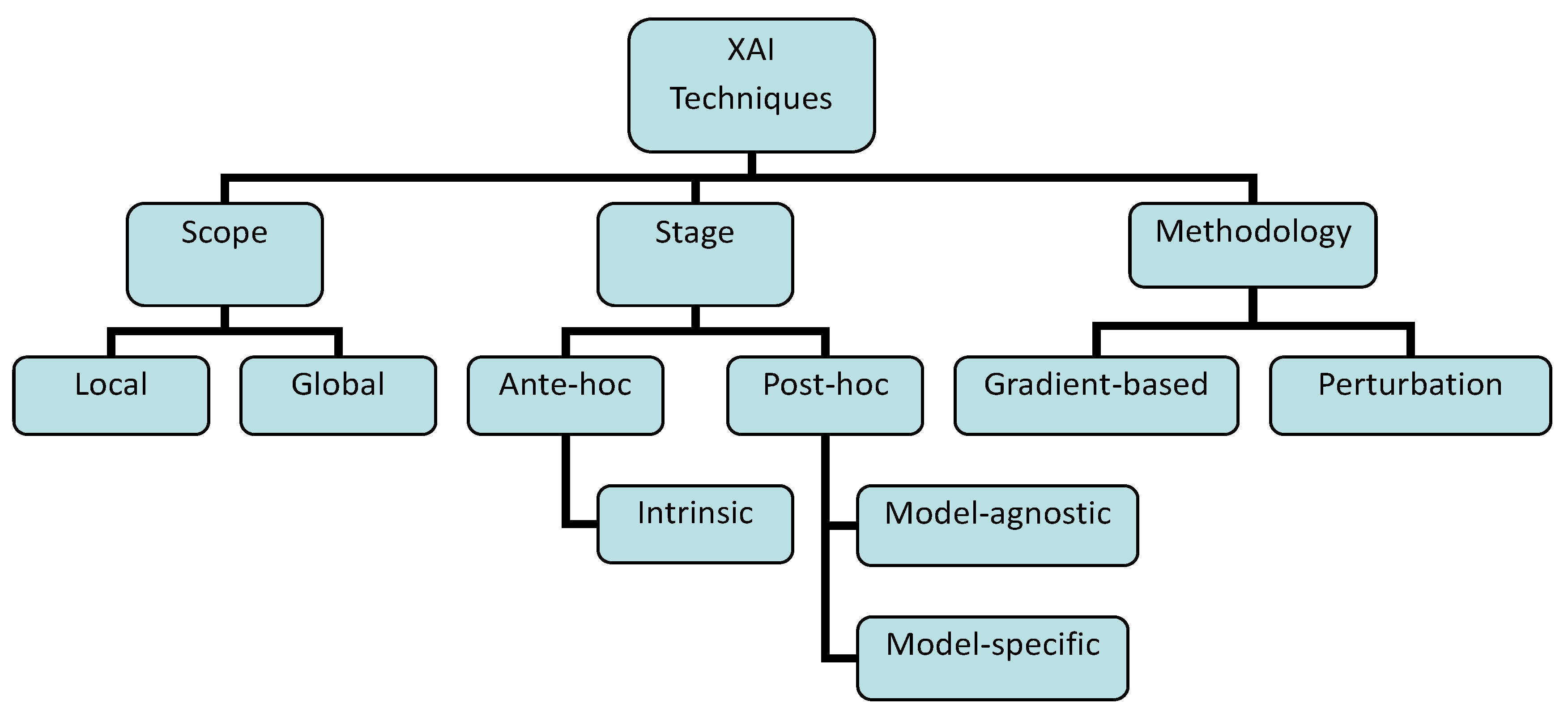

3.2. Explainability Frameworks and XAI Techniques

3.2.1. Local vs. Global XAI Techniques

3.2.2. Ante-Hoc vs. Post-Hoc XAI Techniques

- Model-Agnostic vs. Model-Specific XAI Techniques

3.2.3. Gradient-Based vs. Perturbation-Based Techniques

3.3. Performance Analysis Metrics

3.3.1. Detection Accuracy Metrics

3.3.2. Computational Overhead Metrics

3.3.3. Explainability Quality Metrics

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Questions

4.2. Search Strategy

4.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

4.4. Quality Assessment and Critical Appraisal

4.4.1. Quality Assessment Instrument

4.4.2. Quality Assessment Implementation and Results

4.5. Data Synthesis

5. Results

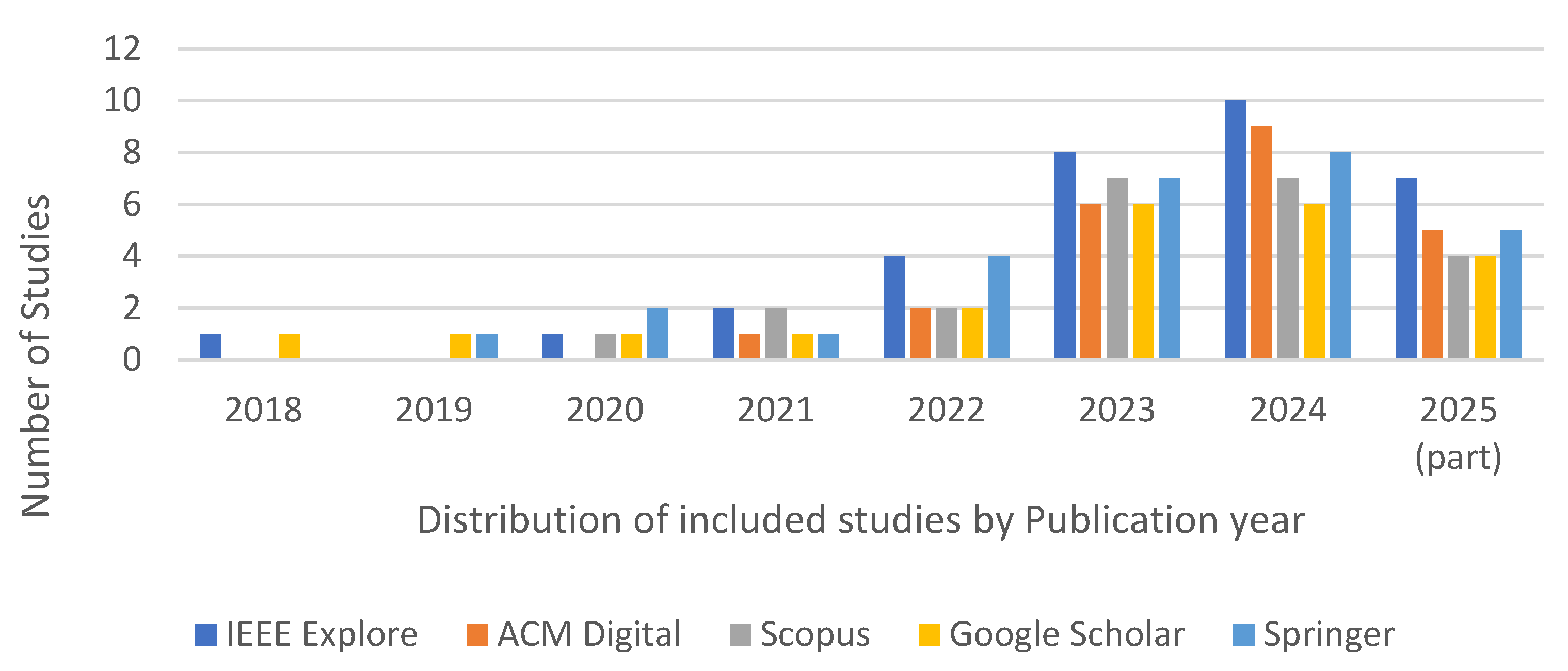

5.1. Overview of Included Studies

| IoT Application Domains | Dataset Used | Year | Ref. Count | # of Features | Total Records | Source Ref. | Key Characteristics & Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial IoT | WUSTL-IIoT-2021 | 2021 | 3 | 41 | 1,194,464 | [99] | Specifically designed for IIoT, includes PLC data and a wide variety of attacks (e.g., DDoS, Reconnaissance, Spoofing). |

| X-IIoTID | 2021 | 1 | 67 | 820,834 | [100] | A recent benchmark dataset for IIoT with both network traffic and device-level logs from various IoT devices. | |

| Vehicular IoT/Intelligent Transportation | Car-Hacking (CAN Intrusion) | 2017 | 2 | 11 | 4,613,909 | [101] | Focuses on in-vehicle networks; contains raw CAN bus traffic with injection attacks (e.g., DoS, Fuzzy, Spoofing). |

| VeReMi | 2018 | 1 | 13 | 3,194,808 | [102] | A dataset for misbehavior detection in Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication, simulating false information attacks. | |

| Cybersecurity | CICIDS2017/2018 | 2017/2018 | 12 | 80 | 2,830,743 | [103] | Not IoT-specific but widely used as a baseline. Contains benign and modern attack traffic, useful for comparison. |

| TON-IoT | 2020 | 11 | 83 | 22.3 M | [104] | Comprehensive data from a smart home/office network, including Windows and Linux system logs alongside IoT sensor data. | |

| NSL-KDD | 2009 | 27 | 43 | 148,517 | [105] | An improved version of the KDD’99 dataset that can still be used for historical comparison. | |

| UNSW-NB15 | 2015 | 24 | 49 | 2,540,044 | [106] | A popular alternative to CICIDS, featuring a mix of modern synthetic activities and attacks | |

| BoT-IoT | 2019 | 12 | 46 | 73,360,900 | [107] | Blends legitimate IoT traffic with DDoS, DoS, Recon, and Theft attacks. | |

| IoMT/Healthcare | CICIoMT | 2024 | 2 | 45 | 8,234,515 | [108] | A modern dataset with network traffic from real medical devices (insulin pumps, pacemaker simulators). |

| N-BaloT | 2018 | 6 | 115 | 849,234 | [109] | Focuses on botnet attacks (Mirai, Bashlite) captured from 9 real IoT devices. Excellent for device-specific botnet detection. | |

| Smart cities IoT | CIC IoT 2022 | 2022 | 9 | 45 | 47 M | [110] | A new dataset from the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity, designed to address gaps in previous IoT datasets. |

| CIC-BoT-IoT | 2022 | 5 | 80 | 3,668,045 | [111] | A newer dataset designed to address gaps in previous IoT datasets. | |

| CICIoT2024 | 2024 | 2 | 84 | 5 M | [108] | A newer dataset from the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity, with network traffic extracted using different extraction approaches. | |

| General/Mixed IoT Environment | IoT-23 | 2020 | 6 | 19 | 325 M | [112] | 20 malware and 3 benign captures from IoT devices. Valued for its real malware traffic and variety of devices. |

| Custom-generated datasets | NA | 6 | NA | NA | [Author-generated] | NA |

5.2. RQ1: XAI Technique Trade-Offs

5.2.1. Findings

5.2.2. Insights and Implications

5.3. DL Model Comparison

5.3.1. Findings

5.3.2. Insights and Implications

5.4. XAI Evaluation Framework

5.4.1. Findings

5.4.2. Insights and Implications

5.5. Bottlenecks and Mitigations

5.5.1. Findings: Identified Bottlenecks

- Computational Overhead of Post hoc XAI Techniques

- 2.

- Lack of comprehensive computational efficiency reporting

- 3.

- Inadequate IoT-domain-specific datasets for intrusion detection studies

5.5.2. Insights: Mitigations Strategies

- 1.

- To manage high computational demands, researchers should use model-specific explainability methods. Techniques like Grad-CAM for CNNs leverage internal gradients and activation maps to produce efficient explanations without requiring input perturbation or numerous model queries [30]. Additionally, XAI computation should be offloaded from constrained IoT devices to more capable platforms, such as local edge gateways, fog nodes, or local server clusters, ensuring that real-time intrusion detection remains unaffected by the explanation process.

- 2.

- To reduce resource costs of post hoc explanations, the focus should shift to architectures that are intrinsically interpretable, like attention-based models where attention weights serve as explanations [128] or that use knowledge distillation. In this approach, a complex, high-accuracy “teacher” DL model trains a smaller, faster, and more memory-efficient “student” model. The student model, which is easier to interpret, can then be deployed at the resource-constrained edge, effectively reducing inference time and overhead for generating reliable explanations [129].

- 3.

- To tackle the issue of inadequate computational reporting, the research community should first establish and adopt a minimum reporting standard for efficiency metrics. This standard should require the inclusion of inference latency, energy consumption, and memory usage. By doing so, it will create a baseline for comparability and help validate the model’s practical feasibility for constrained IoT edge environments.

- 4.

- To address the inadequacy of IoT-domain-specific datasets, a collaborative effort is needed to create and maintain large-scale, publicly available benchmark datasets derived from real-world IoT environments. This involves building heterogeneous testbeds with a variety of devices, including sensors, cameras, and smart appliances, while also recording comprehensive network traffic that encompasses a wide range of modern, IoT-specific attacks (e.g., MQTT exploits, CoAP DDoS). It is essential that these datasets accurately reflect a variety of normal behaviors to minimize false positives.

5.6. Unified Explainable IDS Evaluation Framework (UXIEF)

UXIEF Application

6. Future Research Directions

- Holistic Co-Design of detection, efficiency, and explainability

- 2.

- Development of Resource-Efficient and Intrinsically Interpretable Architectures

- 3.

- Robust and Realistic IoT-domain-specific benchmark dataset

- 4.

- Integration of Rigorous and Standard XAI Evaluation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walling, S.; Lodh, S. An Extensive Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques on Network Intrusion Detection for IoT. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2025, 36, e70064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selem, M.; Jemili, F.; Korbaa, O. Deep learning for intrusion detection in IoT networks. Peer Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, S.; Gao, T.; Javeed, D.; Saeed, M.S.; Adil, M. Trust my IDS: An explainable AI integrated deep learning-based transparent threat detection system for industrial networks. Comput. Secur. 2025, 149, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.I.; Tsado, Y.; Ogunjinmi, A.A.; Sanchez-Velazquez, E.; Peng, Y.; Rawat, D.B. Multi-stage deep learning for intrusion detection in industrial internet of things. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 60532–60555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H.; Khan, A.I.; Abushark, Y.B.; Alsolami, F. Internet of things (IoT) security intelligence: A comprehensive overview, machine learning solutions and research directions. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023, 28, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshenko, N.; Bou-Harb, E.; Crichigno, J.; Kaddoum, G.; Ghani, N. Demystifying IoT security: An exhaustive survey on IoT vulnerabilities and a first empirical look on Internet-scale IoT exploitations. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2702–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou El Houda, Z.; Brik, B.; Senouci, S.M. A novel IoT-based explainable deep learning framework for intrusion detection systems. IEEE Internet Things Mag. 2022, 5, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Koroniotis, N.; Keshk, M.; Zomaya, A.Y.; Tari, Z. Explainable intrusion detection for cyber defences in the internet of things: Opportunities and solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1775–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, P.; Newe, T.; Dhirani, L.L.; O’Connell, E.; O’Shea, D.; Lee, B.; Rao, M. A study of network intrusion detection systems using artificial intelligence/machine learning. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulganiyu, O.H.; Ait Tchakoucht, T.; Saheed, Y.K. A systematic literature review for network intrusion detection system (IDS). Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 1125–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabouni, N.; Mosbah, M.; Zemmari, A.; Sauvignac, C.; Faruki, P. Network intrusion detection for IoT security based on learning techniques. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2671–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Orr, R.J.; Cox, A.; Ashokkumar, P.; Rizvi, M.R. Identifying the attack surface for IoT network. Internet Things 2020, 9, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Sivaraman, V. IoT network security: Requirements, threats, and countermeasures. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.09339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, M.; Roy, K.; Kelly, J.; Olusola, O. Anomaly-based intrusion detection system for IoT application. Discov. Internet Things 2023, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukabayeva, T.; Benkhelifa, E.; Satybaldina, D.; Rehman, A.U. Advancing IoT Security: A Review of Intrusion Detection Systems Challenges and Emerging Solutions. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Software Defined Systems (SDS), Gran Canaria, Spain, 9–11 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, N.; Pandya, S. Internet of things applications, security challenges, attacks, intrusion detection, and future visions: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59353–59377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijalkovic, J.; Spognardi, A. Reducing the false negative rate in deep learning-based network intrusion detection systems. Algorithms 2022, 15, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Daud, A.; Khan, K.; Muhammad, S.; Haq, R. Exploring the frontiers of deep learning and natural language processing: A comprehensive overview of key challenges and emerging trends. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2023, 4, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Luo, R.; Liu, X.; Qiu, J.; Liu, J. Distributed DDPG-based resource allocation for age of information minimization in mobile wireless-powered Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 29102–29115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.; Jabraeil Jamali, M.A. Internet of Things intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive review and future directions. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 3753–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Syed, N.F.; Fu, X.; Baig, Z.; Robles-Kelly, A. Towards a deep learning-driven intrusion detection approach for Internet of Things. Comput. Netw. 2021, 186, 107784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Song, H.; Lv, Z. Deep learning in security of internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 22133–22146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.H.; Azzam, S.M.; Emam, O.E.; Abohany, A.A. Advancing cybersecurity: A comprehensive review of AI-driven detection techniques. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Sharma, L.; Lal, C.; Roy, S. Explainable artificial intelligence for intrusion detection in IoT networks: A deep learning-based approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunseyi, T.B.; Thiyagarajan, G. An Explainable LSTM-Based Intrusion Detection System Optimized by Firefly Algorithm for IoT Networks. Sensors 2025, 25, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotis, F.; Taxiarxchis, K.; Georgios, K.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.A. Intrusion detection in critical infrastructures: A literature review. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, A.; McCoy, J.; Rawat, D.B.; Sadler, B.M.; Amant, R.S. Recent advances in trustworthy explainable artificial intelligence: Status, challenges, and perspectives. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, 852–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ŞAHiN, E.; Arslan, N.N.; Özdemir, D. Unlocking the black box: An in-depth review on interpretability, explainability, and reliability in deep learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 859–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Eschenbach, W.J. Transparency and the black box problem: Why we do not trust AI. Philos. Technol. 2021, 34, 1607–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting black-box models: A review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Ables, J.; Anderson, W.; Mittal, S.; Rahimi, S.; Banicescu, I.; Seale, M. Explainable intrusion detection systems (x-ids): A survey of current methods, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 112392–112415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshk, M.; Koroniotis, N.; Pham, N.; Moustafa, N.; Turnbull, B.; Zomaya, A.Y. An explainable deep learning-enabled intrusion detection framework in IoT networks. Inf. Sci. 2023, 639, 119000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, S.A.; Foh, C.H.; Shojafar, M.; Carrez, F.; Moessner, K. Network Intrusion Detection: An IoT and Non IoT-Related Survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 147167–147191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Murah, M.Z.; Hasan, M.K.; Aman, A.H.M.; Fang, J.; Hu, X.; Khan, A.U.R. A survey of deep learning technologies for intrusion detection in Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 4745–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Kashif, M.; Jhaveri, R.H.; Raut, R.; Saba, T.; Bahaj, S.A. Deep learning for intrusion detection and security of Internet of things (IoT): Current analysis, challenges, and possible solutions. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 4016073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asharf, J.; Moustafa, N.; Khurshid, H.; Debie, E.; Haider, W.; Wahab, A. A review of intrusion detection systems using machine and deep learning in internet of things: Challenges, solutions and future directions. Electronics 2020, 9, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon Femi, P.; Ashwini, K.; Kala, A.; Rajalakshmi, V. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Cybersecurity. Wirel. Commun. Cybersecur. 2023, 103, 149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, D.; Wang, H.X.; Li, Y.F.; Nguyen, T.N. Explainable artificial intelligence: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 3503–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoub, G.; Bentahar, J.; Wahab, O.A.; Mizouni, R.; Song, A.; Cohen, R.; Otrok, H.; Mourad, A. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence for cybersecurity. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2023, 20, 5115–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmet, F.; Tanuwidjaja, H.C.; Ayoubi, S.; Gimenez, P.F.; Han, Y.; Jmila, H.; Blanc, G.; Takahashi, T.; Zhang, Z. Explainable artificial intelligence for cybersecurity: A literature survey. Ann. Telecommun. 2022, 77, 789–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Al Hamadi, H.; Damiani, E.; Yeun, C.Y.; Taher, F. Explainable artificial intelligence applications in cyber security: State-of-the-art in research. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 93104–93139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, G.; Jhaveri, R.H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Pandya, S.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Yenduri, G.; Yenduri, G.; Hall, J.G.; Alazab, M.; Gadekallu, T.R. XAI for cybersecurity: State of the art, challenges, open issues and future directions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.03585. [Google Scholar]

- Mohale, V.Z.; Obagbuwa, I.C. A systematic review on the integration of explainable artificial intelligence in intrusion detection systems to enhancing transparency and interpretability in cybersecurity. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1526221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samed, A.L.; Sagiroglu, S. Explainable artificial intelligence models in intrusion detection systems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, C.; Rios, T.N. Explainable artificial intelligence and cybersecurity: A systematic literature review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.01259. [Google Scholar]

- Ramya, P.; Babu, S.V.; Venkatesan, G. Advancing cybersecurity with explainable artificial intelligence: A review of the latest research. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th international Conference on Inventive Research in Computing Applications (ICIRCA), Coimbatore, India, 3–5 August 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1351–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlicki, M.; Pawlicka, A.; Kozik, R.; Choraś, M. Advanced insights through systematic analysis: Mapping future research directions and opportunities for xAI in deep learning and artificial intelligence used in cybersecurity. Neurocomputing 2024, 590, 127759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, J. Convolutional neural network (CNN): The architecture and applications. Appl. J. Phys. Sci. 2022, 4, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, X. CNN-based hidden-layer topological structure design and optimization methods for image classification. Neural Process. Lett. 2022, 54, 2831–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, L.; Ling, T.C.; Liew, C.S.; Aryanfar, A. A survey of CNN-based network intrusion detection. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, O.; Salam, S.; Dahir, H. The AI Revolution in Networking, Cybersecurity, and Emerging Technologies; Pearson: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. Robust learning-enabled intelligence for the internet of things: A survey from the perspectives of noisy data and adversarial examples. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 9568–9579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldweesh, A.; Derhab, A.; Emam, A.Z. Deep learning approaches for anomaly-based intrusion detection systems: A survey, taxonomy, and open issues. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 189, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Van Merriënboer, B.; Gulcehre, C.; Bahdanau, D.; Bougares, F.; Schwenk, H.; Bengio, Y. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. Exploring the development and application of LSTM variants. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 53, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, S. Introduction to Sequence Learning Models: RNN, LSTM, GRU; Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2021; p. 37988518. [Google Scholar]

- Shiri, F.M.; Perumal, T.; Mustapha, N.; Mohamed, R. A comprehensive overview and comparative analysis on deep learning models: CNN, RNN, LSTM, GRU. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.17473. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, I.; Mahmoud, Q.H. Design and development of RNN anomaly detection model for IoT networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 62722–62750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilichev, D.; Turimov, D.; Kim, W. Next–generation intrusion detection for iot evcs: Integrating cnn, lstm, and gru models. Mathematics 2024, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G. Deep autoencoder neural networks: A comprehensive review and new perspectives. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 3981–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Pei, Y.; Li, J. A comprehensive survey on design and application of autoencoder in deep learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 138, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Hyun, S.; Cheong, Y.G. Analysis of autoencoders for network intrusion detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrayes, F.S.; Zakariah, M.; Amin, S.U.; Khan, Z.I.; Helal, M. Intrusion detection in IoT systems using denoising autoencoder. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 122401–122425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Sun, Z. RTIDS: A robust transformer-based approach for intrusion detection system. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64375–64387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özer, Ç.; Orman, Z. Transformers Architecture Oriented Intrusion Detection Systems: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Engineering, Technology and Applications, Catania, Italy, 24–25 May 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Manocchio, L.D.; Layeghy, S.; Lo, W.W.; Kulatilleke, G.K.; Sarhan, M.; Portmann, M. Flow transformer: A transformer framework for flow-based network intrusion detection systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaluk, B.; Hamdan, M.; Ghaleb, M.; Gismalla, M.S.; da Silva, F.S.C.; Batista, D.M. Towards a Transformer-Based Pre-trained Model for IoT Traffic Classification. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2024–2024 IEEE Network Operations and Management Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6–10 May 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kheddar, H. Transformers and large language models for efficient intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.07583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R.; Dave, D.; Naik, H.; Singhal, S.; Omer, R.; Patel, P.; Qian, B.; Wen, Z.; Shah, T.; Morgan, G.; et al. Explainable AI (XAI): Core ideas, techniques, and solutions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersha, M.; Lam, K.; Wood, J.; AlShami, A.; Kalita, J. Explainable artificial intelligence: A survey of needs, techniques, applications, and future direction. Neurocomputing 2024, 599, 128111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Mehta, M.A. An overview of explainable AI methods, forms and frameworks. Explain. AI Found. Methodol. Appl. 2022, 232, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, S.; Zarei, N.; Ragan, E.D. A multidisciplinary survey and framework for design and evaluation of explainable AI systems. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. (TiiS) 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should i trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Retzlaff, C.O.; Angerschmid, A.; Saranti, A.; Schneeberger, D.; Roettger, R.; Mueller, H.; Holzinger, A. Post-hoc vs ante-hoc explanations: xAI design guidelines for data scientists. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2024, 86, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Ahmed, M.U.; Barua, S.; Begum, S. A systematic review of explainable artificial intelligence in terms of different application domains and tasks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilone, G.; Longo, L. Explainable artificial intelligence: A systematic review. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.V.; Pereira, E.M.; Cardoso, J.S. Machine learning interpretability: A survey on methods and metrics. Electronics 2019, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Rad, P. Opportunities and challenges in explainable artificial intelligence (xai): A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, I.E.; Dera, D.; Rasool, G.; Ramachandran, R.P.; Bouaynaya, N.C. Robust explainability: A tutorial on gradient-based attribution methods for deep neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2022, 39, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; PMLR: Westminster, UK, 2017; pp. 3319–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Itti, L.; Koch, C.; Niebur, E. A model of saliency-based visual attention for rapid scene analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 20, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; Pham, Q.V.; Ruby, R.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z. Explainable AI over the Internet of Things (IoT): Overview, state-of-the-art and future directions. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2022, 3, 2106–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovs, M.; Kadikis, R.; Ozols, K. Perturbation-based methods for explaining deep neural networks: A survey. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 150, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kök, I.; Okay, F.Y.; Muyanlı, Ö.; Özdemir, S. Explainable artificial intelligence (xai) for internet of things: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 14764–14779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.V.; Vogel-Heuser, B. A Taxonomy of Metrics and Tests to Evaluate and Validate Properties of Industrial Intrusion Detection Systems. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (ICETE), Prague, Czech Republic, 26–28 July 2019; pp. 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kadam, V.; Verma, R. Evaluating Effectiveness: A Critical Review of Performance Metrics in Intrusion Detection System. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2025, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunseyi, T.B.; Avoussoukpo, C.B.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X. An Effective Network Intrusion Detection Systems on Diverse IoT Traffic Datasets: A Hybrid Feature Selection and Extraction Method. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2026, 28, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, J.; Azad, M.A.; Amad, R.; Salah, K.; Alazab, M.; Iqbal, R. A review of performance, energy and privacy of intrusion detection systems for IoT. Electronics 2020, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfström, H.; Hammar, K.; Johansson, U. A meta survey of quality evaluation criteria in explanation methods. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering, Leuven, Belgium, 6–10 June 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Gandomi, A.H.; Chen, F.; Holzinger, A. Evaluating the quality of machine learning explanations: A survey on methods and metrics. Electronics 2021, 10, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovrano, F.; Vitali, F. An objective metric for explainable AI: How and why to estimate the degree of explainability. Knowl. Based Syst. 2023, 278, 110866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoverde-Molina, M.; Luján-Mora, S. Cybersecurity in smart agriculture: A systematic literature review. Comput. Secur. 2024, 150, 104284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyaperumal, P.; Karuppiah, T.; Perumal, R.; Thirumalaisamy, M.; Balusamy, B.; Benedetto, F. Enhancing cybersecurity in Agriculture 4.0: A high-performance hybrid deep learning-based framework for DDoS attack detection. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 126, 110431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldini, A.; Ardito, L.; Bianco, G.M.; Valsesia, M. Lich: Enhancing IoT Supply Chain Security Through Automated Firmware Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2025 21st International Conference on Distributed Computing in Smart Systems and the Internet of Things (DCOSS-IoT), Lucca, Italy, 9–11 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 747–754. [Google Scholar]

- Zolanvari, M.; Teixeira, M.A.; Gupta, L.; Khan, K.M.; Jain, R. WUSTL-IIOT-2021 Dataset for IIoT Cybersecurity Research; Washington University in St. Louis: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/iiot2/index.html (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Al-Hawawreh, M.; Sitnikova, E.; Aboutorab, N. X-IIoTID: A connectivity-agnostic and device-agnostic intrusion data set for industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 3962–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Song, H.M.; Kim, H.K. GIDS: GAN based intrusion detection system for in-vehicle network. In Proceedings of the 2018 16th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Belfast, Ireland, 28–30 August 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Heijden, R.W.; Lukaseder, T.; Kargl, F. Veremi: A dataset for comparable evaluation of misbehavior detection in vanets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Privacy in Communication Systems, Singapore, 8–10 August 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 318–337. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, R. CICIDS2017; IEEE Dataport: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, A.; Moustafa, N.; Tari, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Anwar, A. TON_IoT telemetry dataset: A new generation dataset of IoT and IIoT for data-driven intrusion detection systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 165130–165150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavallaee, M.; Bagheri, E.; Lu, W.; Ghorbani, A.A. A detailed analysis of the KDD CUP 99 data set. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence for Security and Defense Applications, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 8–10 July 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In Proceedings of the 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), Canberra, Australia, 10–12 November 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Koroniotis, N.; Moustafa, N.; Sitnikova, E.; Turnbull, B. Towards the development of realistic botnet dataset in the internet of things for network forensic analytics: Bot-iot dataset. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 100, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, S.; Neto, E.C.P.; Ferreira, R.; Molokwu, R.C.; Sadeghi, S.; Ghorbani, A. Ciciomt2024: Attack Vectors in Healthcare Devices-a Multi-Protocol Dataset for Assessing Iomt Device Security; UNB: Fredericton, NB, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-baiot—Network-based detection of iot botnet attacks using deep autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Dadkhah, S.; Ferreira, R.; Zohourian, A.; Lu, R.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoT2023: A real-time dataset and benchmark for large-scale attacks in IoT environment. Sensors 2023, 23, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, M.; Layeghy, S.; Portmann, M. Evaluating standard feature sets towards increased generalisability and explainability of ML-based network intrusion detection. Big Data Res. 2020, 30, 100359. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, S.; Parmisano, A.; Erquiaga, M.J. IoT-23: A Labeled Dataset with Malicious and Benign IoT Network Traffic. Version 1.0.0. Zenodo. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4743746 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Angelov, P.P.; Soares, E.A.; Jiang, R.; Arnold, N.I.; Atkinson, P.M. Explainable artificial intelligence: An analytical review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2021, 11, e1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Rathour, A.; Sharma, A.; Chhabra, G.S. Bridging Explainability and Security: An XAI-Enhanced Hybrid Deep Learning Framework for IoT Device Identification and Attack Detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 127368–127390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, V.; Tanwar, S.; Choudhury, T. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Intrusion Detection System in the Internet of Things Environment. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI), Sakhir, Bahrain, 25–26 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 682–689. [Google Scholar]

- Siganos, M.; Radoglou-Grammatikis, P.; Kotsiuba, I.; Markakis, E.; Moscholios, I.; Goudos, S.; Sarigiannidis, P. Explainable ai-based intrusion detection in the internet of things. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Benevento, Italy, 29 August–1 September 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhwani, S.; Navare, A.; Mohan, A.; Muthalagu, R.; Pawar, P.M. IoT-based intrusion detection system using explainable multi-class deep learning approaches. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 123, 110256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Latif, S.; Khan, I.U.; Alshehri, M.S.; Khan, M.S.; Alasbali, N.; Jiang, W. An interpretable deep learning framework for intrusion detection in industrial Internet of Things. Internet Things 2025, 33, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.Y.B.; Sarkar, P.; Goswami, B.; Patil, P.R.; Al-Said, K.; Al Said, N. A Framework for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Explainability Methods in Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Pervasive Computational Technologies (ICPCT), Greater Noida, India, 8–9 February 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 426–430. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidouche, M.; Popko, E.; Ouni, B. Enhancing iot security via automatic network traffic analysis: The transition from machine learning to deep learning. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on the Internet of Things, Nagoya, Japan, 7–10 November 2023; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.; Al-Wadi, A. Enhancing IoMT network security using ensemble learning-based intrusion detection systems. J. Eng. Res. 2024, 4, 3166–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaoud, A.; Kalita, J. Optimized detection of cyber-attacks on IoT networks via hybrid deep learning models. Ad Hoc Netw. 2025, 170, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Tempini, N.; Lin, H.; Yin, H. An energy-efficient and trustworthy unsupervised anomaly detection framework (EATU) for IIoT. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2022, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, P.; Sahu, D.; Prakash, S.; Yang, T.; Rathore, R.S.; Pandey, V.K. A high- performance hybrid LSTM CNN secure architecture for IoT environments using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haija, Q.A.; Droos, A. A comprehensive survey on deep learning-based intrusion detection systems in Internet of Things (IoT). Expert Syst. 2025, 42, e13726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, M.A.; Razak, S.; Siraj, M.M.; Nafea, I.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Saeed, F.; Nasser, M. Anomaly-based intrusion detection systems in iot using deep learning: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.I.; Galindo, M.; Xie, H.; Wong, L.K.; Shuai, H.H.; Li, Y.H.; Cheng, W.H. Lightweight deep learning for resource-constrained environments: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, V.; Frej, J.; Käser, T. The future of human-centric eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is not post-hoc explanations. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2025, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M. Efficient Deep Learning Models for Edge IOT Devices-A Review. Authorea Preprints. 2024. Available online: https://www.techrxiv.org/doi/full/10.36227/techrxiv.172254372.21002541/v1 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Kalakoti, R.; Bahsi, H.; Nõmm, S. Improving iot security with explainable ai: Quantitative evaluation of explainability for iot botnet detection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 18237–18254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Schrum, M.; Hedlund-Botti, E.; Gopalan, N.; Gombolay, M. Explainable artificial intelligence: Evaluating the objective and subjective impacts of xai on human-agent interaction. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Ruffo, V.G.; Lent, D.M.B.; Komarchesqui, M.; Schiavon, V.F.; de Assis, M.V.O.; Carvalho, L.F.; Proença, M.L., Jr. Anomaly and intrusion detection using deep learning for software-defined networks: A survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 256, 124982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref | Domain | Threat/Detection | Contributions | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [33] | IoT | NID |

| Lack of focus on performance and resource efficiency in resource-constrained IoT network |

| [20] | IoT | IDS |

| Lack of focus on performance and resource efficiency in resource-constrained IoT network |

| [34] | IoT | IDS |

| Lack of focus on performance and resource efficiency in resource-constrained IoT network |

| [35] | IoT | IDS |

| Lack of focus on performance and resource efficiency in resource-constrained IoT network |

| [36] | IoT | IDS |

| Lack of focus on performance and resource efficiency in resource-constrained IoT network |

| [39] | XAI | NIDS |

| No focus on performance analysis of efficiency in of XAI techniques |

| [40] | XAI | Malware, IPS |

| Lacks any form of evaluation criteria for XAI implementation |

| [41] | XAI | IDS, malware and spam filtering |

| Lack of focus on unique IoT environments |

| [42] | XAI | Cyber threats |

| Fails to explore the operational effectiveness of XAI when deployed in IoT |

| [43] | XAI | IDS |

| No focus on performance analysis of efficiency of XAI techniques |

| [44] | XAI | IDS |

| No focus on performance analysis of efficiency of XAI techniques |

| [45] | XAI | Cyber threats |

| No focus on performance analysis of efficiency of XAI techniques |

| [46] | XAI | Malware, IDS, botnet detection |

| No focus on performance analysis of efficiency of XAI techniques |

| [47] | XAI | Cyber threats |

| Lack of focus on unique IoT environments |

| Metrics | Formula | Explanation | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN) | Measures the proportion of overall correctness | Commonly used, but can be misleading in imbalanced datasets |

| Precision | TP/(TP + FP) | Measures the proportion of correctly identified positive cases among all positive predictions | Minimizes false alarms, which is important for security operations |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP/(TP + FN) | Measures the proportion of correctly identified positive cases among all actual positive cases | Minimizes missed attacks, which is critical for security |

| F1-Score | 2 × (Precision × Recall)/(Precision + Recall) | Measures the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both | Used for balancing between false alarms and missed detections |

| Specificity | TN/(TN + FP) | Measures the proportion of correctly identified negative cases among all actual negative cases | Minimizes misclassifying normal traffic as malicious |

| Metrics | Explanation | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Latency/Inference Time | The time taken for the IDS to process a single network packet or flow and provide a detection | It is crucial for real-time threat detection and response in an IoT network |

| Throughput | This is the number of packets or flows processed per unit of time | This indicates the system’s capacity to handle a high volume of IoT traffic |

| Memory Usage | The amount of memory required by the DL model during operation | It is a direct constraint for low-memory IoT devices and embedded systems. |

| Energy Consumption | This is the power drawn by the IDS components (CPU, memory) during operation | It is crucial for battery-powered IoT devices and for sustainable large-scale deployments. |

| Metrics | Explanation | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Faithfulness/Fidelity | It shows how accurately the explanation reflects the actual reasoning process of the black-box model | It is essential for trust and avoiding misleading explanations |

| Comprehensibility/Understandability | It is concerned with how easy it is for a human (e.g., a security analyst) to grasp the explanation. Whether the explanation is presented in an intuitive way | It directly impacts the usability and actionability of the NIDS |

| Actionability/Utility | It shows how the explanation provides insights that enable a security professional to take effective action | It is concerned with the ultimate goal of XAI in security, i.e., to empower humans in decision-making |

| Stability/Consistency | It shows whether similar inputs yield similar explanations or if minor changes in input drastically alter the explanation | It confirms that unstable explanations are confusing and untrustworthy |

| Specificity/Granularity | It shows how detailed and precise the explanation is. Whether it points to specific features or general patterns | It confirms that more specific explanations are often more actionable |

| RQ Areas | RQs | Sub-Questions |

|---|---|---|

| RQ 1 (XAI Technique Trade-offs) | How do XAI techniques impact the detection accuracy and computational efficiency of DL-based IDSs in IoT networks? | How do XAI techniques impact the detection accuracy of DL-based IDSs for IoT networks? |

| How do XAI techniques impact the computational efficiency of DL-based IDSs for IoT networks? | ||

| RQ 2 (Model Comparison) | Which explainable DL architectures achieve the best detection performance and resource efficiency for high-dimensional IoT traffic? | What explainable DL architectures achieve the best detection performance for high-dimensional IoT traffic? |

| Which explainable DL architectures achieve the best resource efficiency for high-dimensional IoT traffic? | ||

| RQ 3 (XAI evaluation) | How are post hoc XAI techniques (e.g., SHAP, LIME) evaluated for their effectiveness and reliability in explaining DL-based IDS decisions within IoT security contexts? | |

| RQ 4 (Bottleneck and mitigation) | What are the bottlenecks limiting the deployment of explainable DL-based IDSs in large-scale IoT networks, and how can they be mitigated? | What are the bottlenecks limiting the deployment of XDL-based IDSs in large-scale IoT networks? |

| What are some of the mitigations to these bottlenecks? |

| Database | Search String with Field Restrictions | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| IEEE Xplore | (“Document Title”: “explainable AI” OR “Document Title”: XAI OR “Document Title”: “interpretable AI” OR “Abstract”: “explainable AI” OR “Abstract”: XAI) AND (“Document Title”: “intrusion detection” OR “Abstract”: “intrusion detection” OR “Document Title”: IDS OR “Abstract”: IDS) AND (“Document Title”: “internet of things” OR “Document Title”: IoT OR “Abstract”: “internet of things” OR “Abstract”: IoT) AND (“Abstract”: performance OR “Abstract”: evaluation OR “Abstract”: metrics) | Field-specific search in title and abstract |

| ACM Digital Library | [[Title: “explainable AI”] OR [Title: XAI] OR [Abstract: “explainable AI”]] AND [[Title: “intrusion detection”] OR [Abstract: “intrusion detection”]] AND [[Title: “IoT”] OR [Title: “internet of things”] OR [Abstract: IoT]] AND [[Abstract: performance] OR [Abstract: evaluation]] | Advanced search with field specifications |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“explainable AI” OR XAI OR “interpretable AI” OR SHAP OR LIME) AND (“network intrusion detection system” OR “intrusion detection system” OR NIDS OR IDS OR “anomaly detection”) AND (“internet of things” OR “industrial internet of things” OR IoT OR IIoT OR “IoT networks”) AND (performance OR evaluation OR metrics OR robustness OR “computational overhead” OR latency OR energy OR memory)) | Advanced search with field specifications |

| Google Scholar | allintitle: (“explainable AI” OR XAI OR “interpretable AI”) AND (“intrusion detection” OR IDS) AND (IoT OR “internet of things”) AND (performance OR evaluation) | Limited to first 2800–3000 results; allintitle restricts to title field |

| Springer | (title: (“explainable AI” OR XAI OR “interpretable AI”) OR abstract: (“explainable AI” OR XAI)) AND (title: (“intrusion detection” OR IDS) OR abstract: (“intrusion detection”)) AND (title: (IoT OR “internet of things”) OR abstract: (IoT OR “internet of things”)) AND abstract: (performance OR evaluation OR metrics) | SpringerLink advanced search with field operators |

| Notation | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Inclusion |

|

| Exclusion |

|

| Dimension | Criterion | Evaluation Questions | Scoring Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methodological Rigor | QA1: Clear Research Objectives | Are the study objectives clearly defined and aligned with explainable IDS development or evaluation? | 2 = Explicit research questions or hypotheses stated; 1 = Objectives implied but not formally stated; 0 = Objectives unclear or absent |

| QA2: Appropriate Methodology | Is the DL architecture and XAI technique appropriately selected and justified for the stated IoT security problem? | 2 = Clear justification with comparison to alternatives; 1 = Selection stated but not justified; 0 = No rationale provided | |

| Reporting Quality | QA3: Experimental Design | Are experimental procedures (data preprocessing, train-test split, cross-validation, hyperparameters) clearly documented? | 2 = Fully reproducible design with all details; 1 = Some details provided but gaps exist; 0 = Insufficient documentation for replication |

| QA4: Performance Metrics Reporting | Are detection performance metrics comprehensively reported (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, with actual values)? | 2 = ≥4 metrics with numerical values; 1 = 2–3 metrics reported; 0 = ≤1 metric or only qualitative claims | |

| Relevance | QA5: Alignment with Research Questions | Does the study directly address at least one of our research questions (XAI trade-offs, model comparison, XAI evaluation, or deployment challenges)? | 2 = Directly addresses ≥2 RQs with empirical evidence; 1 = Addresses 1 RQ with limited evidence; 0 = Tangential or no clear alignment |

| Validity | QA6: XAI Implementation Rigor | Is the XAI technique implemented and validated (not just mentioned), with explanation outputs presented? | 2 = Full implementation with validation and example outputs; 1 = Implementation without validation; 0 = Only mentioned conceptually |

| Architecture Category | DL Models | Accuracy (%) Range | Precision (%) Range | Recall (%) Range | F1-Score (%) Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightweight CNN | 1D/2D/3D-CNN | 77.5–99.9 | 78.7–99.8 | 73.4–99 | 76–98.8 |

| Sequential Architectures | RNN, LSTM, GRU | 87–99.9 | 83–100 | 84–100 | 88–99.9 |

| Feedforward architectures | DNN, MLP | 83.1–99.2 | 70–99.3 | 84.9–100 | 88.8–99.2 |

| Dimensionality reduction | Autoencoders | 95.4–100 | 94.8–100 | 97.2–99.9 | 96–100 |

| Transformer/attention-based | Vanilla Transformer, ViT | 95.1–99.9 | 95–99.9 | 95–99.9 | 95–99.9 |

| Hybrid architecture | CNN + LSTM, CNN + BiLSTM CNN + GRU, DNN + LSTM | 92.5–99.9 | 92–100 | 91.0–100 | 90.7–99.9 |

| Ref | Architecture Category | Specific DL Models | Processing Unit | Latency (s) Avg | Throughput (s) Avg | Energy Consumption (Joules) | Memory (MB) Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [117] | Lightweight CNN | 2D CNN | CPU | 5.9 | - | - | - |

| [114] | 2D CNN | GPU | 0.0389 | - | - | - | |

| [25] | Sequential Architectures | LSTM | GPU | 0.0085 | - | - | 146.88 |

| [115] | LSTM | CPU | 218 | - | - | - | |

| [118] | GRU | GPU | 16.15 | - | - | - | |

| [119] | LSTM | GPU | 0.469 | - | - | - | |

| [116] | Feedforward architectures | DNN | CPU | 15 | - | - | - |

| [120] | DNN | GPU | 2.9 | - | - | - | |

| [121] | MLP | CPU | 12.42 | - | - | - | |

| [122] | Dimensionality reduction | Autoencoder | CPU | 38 | - | - | - |

| [123] | Autoencoder | GPU | 30 | - | 70 | 9.1 | |

| [124] | Hybrid Architecture | LSTM + CNN | CPU/GPU | 8.4/2.1 | - | - | - |

| Category | Evaluation Types | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| A | No Explicit evaluation | The included study provides no metric, user study, claim, or criteria to confirm if the explanation is correct or useful (i.e., no evaluation). |

| B | Qualitative/plausibility check | The author visually inspects the explanation and makes a claim such as “features X and Y were the most important features”. |

| C | Quantitative/fidelity metrics | The study uses metrics such as faithfulness/accuracy, stability, actionability, etc., to measure the technical quality of the explanation. |

| D | Human-based | The explanation is evaluated by humans, such as a network analyst or cybersecurity professional, in a controlled environment. |

| E | Application-based | The explanation is tested in a real-world task, such as using the explanation to guide a mitigation action. |

| Evaluation Category | Option (Y/N) | No of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| A | Yes | 7 |

| No | 122 | |

| B | Yes | 122 |

| No | 7 | |

| C | Yes | 5 |

| No | 124 | |

| D | Yes | - |

| No | 129 | |

| E | Yes | - |

| No | 129 |

| Dimension 1: Detection Performance | ||

| Sub-Category | Definition & Criterion | Implications |

| High | Performance metric scores > 95% on public and recent IoT dataset | Demonstrates state-of-the-art security effectiveness |

| Medium | Performance metric scores between 85% and 95% on standard datasets | Acceptably suitable for non-critical systems |

| Low | Performance metric scores < 85% or evaluated on custom, non-replicable datasets | Indicates potential real-world unsuitability |

| Dimension 2: Computational Efficiency | ||

| Sub-Category | Definition & Criterion | Implications |

| High efficiency: Edge-Ready | Model inference latency is optimized for real-time processing (e.g., <100 ms per sample) and/or minimal memory footprint (e.g., <10 MB) suitable for basic IoT sensors | Ideal for real-time, on-device deployment where real-time response and battery longevity are critical. |

| Medium efficiency: Fog/Gateway Capable | Model demonstrates moderate resource requirements or moderate memory footprint (within 10–100 MB). | Suitable for IoT gateways or fog nodes that aggregate traffic from multiple devices but may struggle with high-velocity streams. |

| Low efficiency: Offline/Cloud-dependent | Model requires significant computational resources (High GPU/CPU usage, >100 MB memory) or efficiency metrics are entirely omitted. | Restricted to offline analysis with little to no consideration for deployment. Generally impractical for resource-constrained IoT edge devices. |

| Dimension 3: Explainability Quality | ||

| Sub-Category | Definition & Criterion | Implications |

| High: Proven & Actionable | Rigorously tested for accuracy and usefulness with both metrics and human or application evaluation. | High trustworthiness with objectively verified and demonstrably useful for human tasks. |

| Medium: Unverified | Uses standard XAI methods, but only checked for basic plausibility, not real-world value. | Provides a baseline for interpretability but offers no real-world utility. |

| Low: Missing or Unreliable | No explanations, or they are purely descriptive with no proof of being correct or helpful. | Offering no actionable guidance for security analyst. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ogunseyi, T.B.; Thiyagarajan, G.; He, H.; Bist, V.; Du, Z. Performance Analysis of Explainable Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for IoT Networks: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2026, 26, 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020363

Ogunseyi TB, Thiyagarajan G, He H, Bist V, Du Z. Performance Analysis of Explainable Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for IoT Networks: A Systematic Review. Sensors. 2026; 26(2):363. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020363

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgunseyi, Taiwo Blessing, Gogulakrishan Thiyagarajan, Honggang He, Vinay Bist, and Zhengcong Du. 2026. "Performance Analysis of Explainable Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for IoT Networks: A Systematic Review" Sensors 26, no. 2: 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020363

APA StyleOgunseyi, T. B., Thiyagarajan, G., He, H., Bist, V., & Du, Z. (2026). Performance Analysis of Explainable Deep Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems for IoT Networks: A Systematic Review. Sensors, 26(2), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26020363