Real-Time Stream Data Anonymization via Dynamic Reconfiguration with l-Diversity-Enhanced SUHDSA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Taxonomy and Scope

2.2. PPDP Under Classical Models: Grouping and Delay Objectives

2.3. Diversity-Aware Protection and the Open Gap

3. Proposed Data Anonymization Method

3.1. Setting, Notation, and System Constraints

3.2. l-Diversity-Enhanced Dynamic Reconfiguration (Monitor–Trigger–Repair)

| Algorithm 1 l-diversity–enhanced dynamic reconfiguration (streaming SUHDSA) |

| Input: DS; k; l; β; distance d(·,·) λ = 0.7 // weight between ΔIL and ΔRT (0–1) c = 3 // number of QID-nearest neighbors inspected γ = 3 // merge growth cap: |G ∪ H| ≤ γ·k AdaptiveLControllerEnabled ∈ {true, false} // default: false // (optional) controller parameters when enabled: α ∈ (0, 1] // Exponential Moving Average (EMA) smoothing for H_t HysteresisBand ∈ [0, 1], DwellWindows ∈ Output: anonymized stream A 1 Buf ← ∅ 2 while DS not empty do 3 t ← ReadNextTuple(DS); Buf ← Buf ∪ {t} 4 if |Buf| ≥ β or time budget (β) elapsed then 5 ρ ← 0 // reconfiguration counter for this window (swaps + merges); 6 // reset per window and logged to quantify repair overhead vs. latency/throughput 7 G_list ← GroupByQID(Buf, k, d) // provisional groups, |G| ≥ k 8 // (optional) entropy-driven adaptive lt controller (see Appendix B) 9 if AdaptiveLControllerEnabled then 10 lt_global ← AdaptiveLController(Buf, l_min, l_max, α, HysteresisBand, 11 DwellWindows, Ĥ_{t−1}) 12 else 13 lt_global ← l 14 end if 15 for each G in G_list do 16 // decide lt, for this step (global or per-group policy) 17 lt ← (AdaptiveLControllerEnabled ? lt_global:l) 18 if D(G) = |uniq(G.S)| < lt then 19 mark G with priority τ(G) = lt, − D(G) 20 end if 21 end for 22 // Process marked groups by descending τ(G), then by age, β-deadline, |G| 23 for each marked G in DescendBy(τ(G), age(G), time_to_β(G), |G|) do 24 Cands ← TopCNearestByQID(G, G_list, c = 3) 25 H ← SelectFeasibleNeighbor(Cands, k, lt) 26 // choose action by minimizing λΔIL + (1 − λ)ΔRT (Equation (1)) 27 if SwapImprovesAndFeasible(G, H, k, lt, λ) then 28 (G, H) ← SwapMinimalTuples(G, H) 29 // minimal swap to restore D(·) ≥ lt 30 ρ ← ρ + 1 // log: reconfiguration += 1 (used for Section 4.3 sensitivity analysis) 31 else if MergeFeasible(G, H, k, lt, γ = 3) then 32 G ← MergeGroups(G, H) // enforce |G ∪ H| ≤ γ·k 33 ρ ← ρ + 1 // log: reconfiguration += 1 (used for Section 4.3 sensitivity analysis) 34 end if 35 end for 36 for each G in G_list do 37 G.QID ← MicroAggregate(G.QID) 38 // numeric: mean/median; categorical: mode/taxonomy 39 end for 40 Output(A, G_list) // emit anonymized groups for this window 41 LogWindowMetrics(ρ, p50/p95/p99 latency, throughput) 42 Buf ← ∅ 43 end if 44 end while 45 // Flush at stream end: if DS is empty but Buf is non-empty, 46 // finalize remaining records by forming feasible groups (|G| ≥ k, D(G) ≥ l or lt) 47 // or defer to the next window per β policy. |

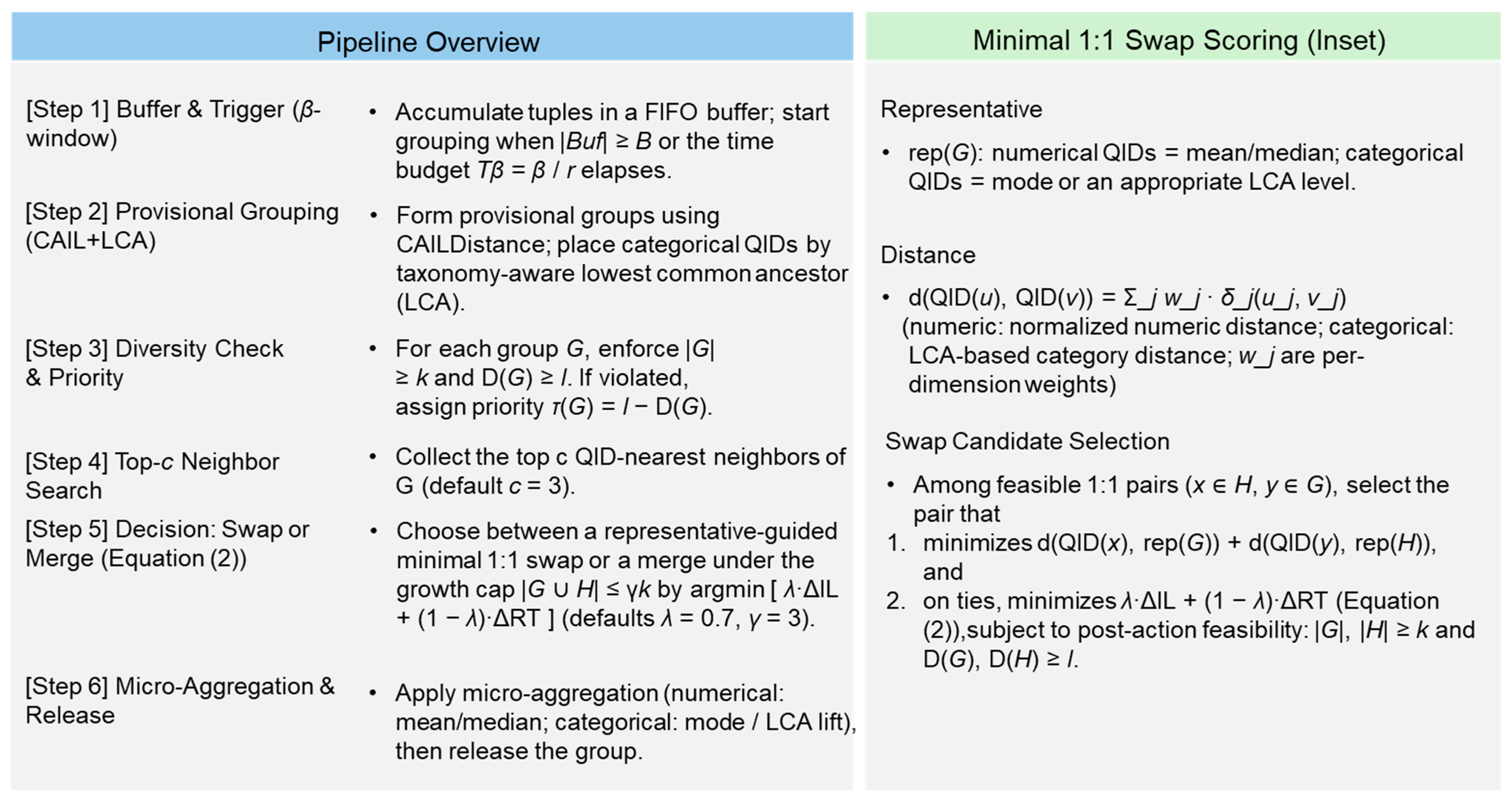

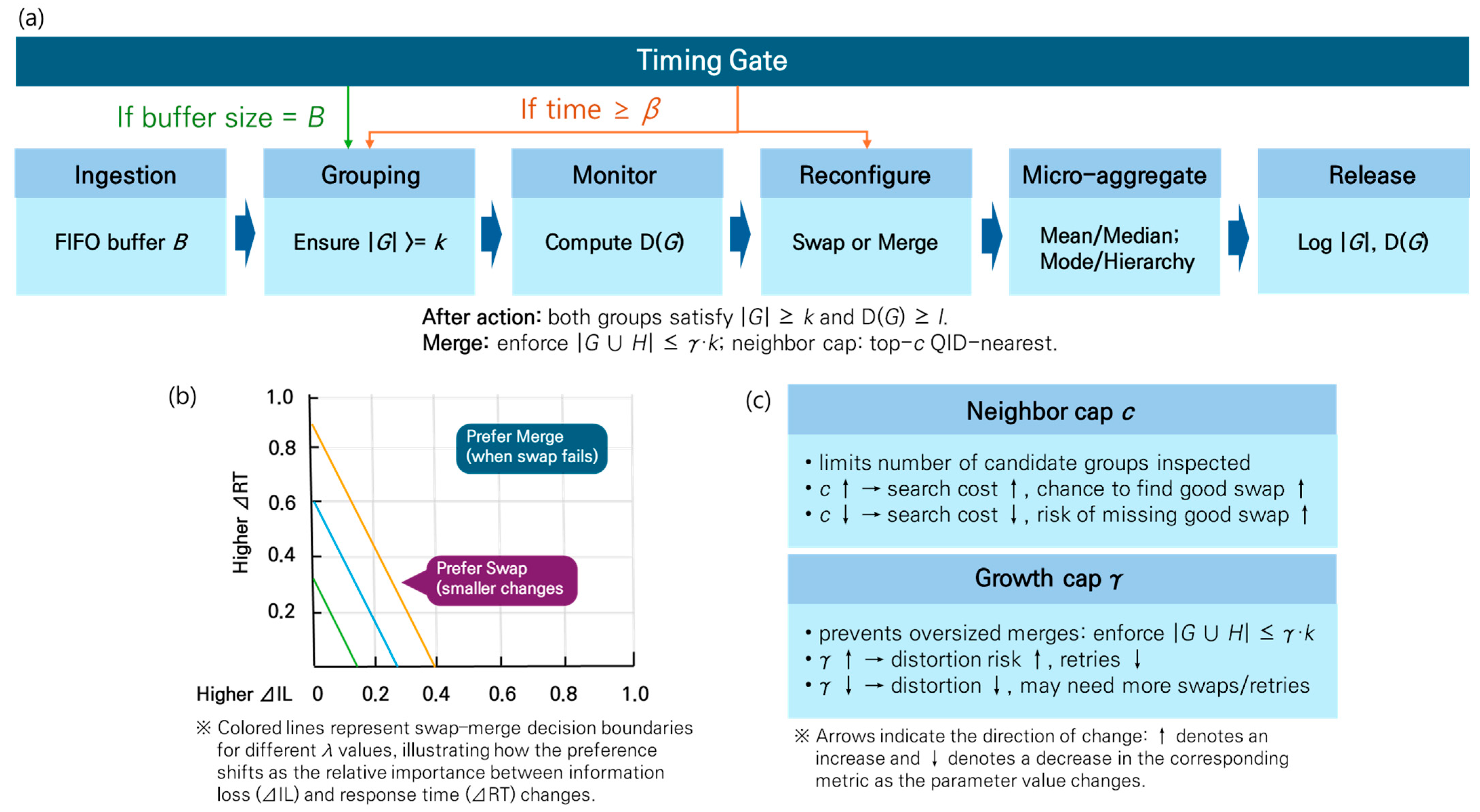

3.3. End-to-End Pipeline, Decision Logic, and Guarantees

- End-to-end flow: Figure 2a (timing gates)

- Swap/merge choice: Figure 2b (decision boundary)

- Search breadth and distortion control: Figure 2c (effects of and )

- Parameter effects

- Privacy, consistency, and auditability (guarantees).

4. Experiments, Complexity, and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup and Protocol

4.2. Complexity

4.3. Results and Interpretation

4.4. Threat Model and Attack Protocol

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations, Threats to Validity, and Mitigation Strategies

- Dataset and generality: Our results are based on the UCI Adult. (Mitigation: use the synthetic-workload blueprint at the end of Section 4.1/Section 4.3—Zipf/exponential/mixture skew, bursts, drift, missingness—to emulate domain characteristics and strengthen external validity with multiple real datasets such as sensor/biomedical telemetry.)

- High dimensionality (m): Higher-dimensional QIDs increase the grouping/microaggregation cost and p95/p99 latency. (Mitigation: apply the Section 5.2 mitigation blueprint—dimensionality reduction (PCA/AE), categorical uplevel/feature hashing, distributed partitioning (generalized QID keys, locality-sensitive hashing (LSH)/blocking), approximate nearest neighbor (ANN)-based search acceleration, and batched reconfiguration/early stopping) to suppress p99 tails and keep p95 ≤ Tβ.)

- Heavy skew/adversarial distributions: A surge in violators (ν) can push reconfiguration toward conservative bounds. (Mitigation: increase β within SLOs; adjust λ downward or γ upward to cut retries; introduce SA-aware seeding.)

- Heuristic choices: Distance metrics and the λ-weighted rule are reasonable but not unique. (Mitigation: evaluate learned or taxonomy-aware metrics; ablate λ, c, and γ for robustness.)

- Single-node implementation: The measurements reflect an optimized single-machine Python code path. (Mitigation: prototype distributed execution in Flink/Spark; colocation of QID-similar partitions.) We do not report end-to-end measurements from a live Kafka/Flink cluster deployment in this paper.

5.4. Future Work Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Runtime Sensitivity Protocol

Appendix A.1. Objective and Scope

Appendix A.2. Metrics and Notations

- : reconfiguration frequency.

- Latencies: p50, p95, p99 (ms)—measured ingress → sink; processing-only or with synthetic per-record delay .

- Throughput: events/s.

- Controller: (optional; default OFF), using EMA/hysteresis/dwell as in Section 3.2.

Appendix A.3. Experimental Design

- Dataset/engine: Same as in Section 4 (pipeline, hardware/software).

- Factors (factorial example):

- ■

- input skew

- ■

- (cardinality);

- ■

- (nearest neighbors);

- ■

- (opt.) Synthetic delay ms/record.

- Repetitions/Length: 5 repetitions per condition; 30 s windows (or N windows).

- ON/OFF comparison: Run with the controller OFF and ON under the same design.

Appendix A.4. Instrumentation

- logging: reset per window; increment by 1 on each swap/merge (see Algorithm 1 lines 32/35).

- Latency/Throughput: aggregate p50/p95/p99 and throughput per window.

- Metadata: factors (skew, , , ), seeds, and failed/dropped windows.

Appendix A.5. Preprocessing

- Validity rules: exclude failed/dropped windows by predefined criteria (record reasons).

- Aggregation: report median/IQR or 95% CIs per condition.

- Normalization (opt.): express p95 relative to ( = Throughput) for comparability.

Appendix A.6. Analysis

- Correlations

- Spearman (monotonic) and Pearson (linear) correlations between and p95/p99/throughput ().

- Piecewise regression

- Fit by segments to estimate the slope (repeat for p99 and throughput).

- Robustness: bootstrap (≥1000 resamples) CIs for ; Huber/quantile regression checks.

- ON/OFF comparison

- is compared across OFF vs. ON, and the slope-reduction ratio is reported.

- Do the same for p99 (tail sensitivity).

- Reporting rule

- Interpret as a methodological comparison (no numeric results in this paper).

Appendix A.7. Reporting Checklist

- Per-condition summary: ρ, p50/p95/p99, throughput (median [IQR] or 95% CI).

- Correlation summary: Spearman/Pearson correlations and significance.

- Piecewise sensitivity summary: piecewise slopes b with 95% CIs (OFF/ON; p95/p99/throughput).

- Optional visual diagnostics: scatter plots of ρ vs. p95 and ρ vs. p99 with fitted lines (OFF/ON overlaid).

- Note: This appendix provides reproducibility-oriented reporting guidance; no actual result tables/figures are included.

Appendix A.8. Reproducibility (Recommended)

- Environment: OS/runtime/library versions; CPU/GPU/memory.

- Seeds: random seeds.

- Config: all factor settings (skew, , , ); controller parameters (, hysteresis band, dwell).

Appendix B. Entropy-Driven Adaptive Controller (Pseudocode)

| Algorithm A1: AdaptiveLtController(Buf_t, l_min, l_max, α, HysteresisBand, DwellWindows, Hhat_prev, e_prev, lt_prev, last_change_t, |S|) |

| 1 H_t ← Entropy(Buf_t.S) // as defined above 2 Hhat_t ← α·H_t + (1−α)·Hhat_prev 3 e_t ← clip(Hhat_t / log(|S|), 0, 1) 4 lt_cand ← floor(l_min + (l_max − l_min)·e_t) 5 // floor: enforce integer lt (diversity level is discrete) 6 // or (1−e_t), keep consistent with Algorithm 1 7 lt_cand ← clip(lt_cand, l_min, l_max) 8 // clip: bound lt within [l_min, l_max] to avoid overly strict/loose targets 9 if (t − last_change_t) < DwellWindows then 10 lt ← lt_prev 11 else if |e_t − e_prev| < HysteresisBand then 12 lt ← lt_prev 13 else 14 lt ← lt_cand; last_change_t ← t 15 end if 16 return (lt, Hhat_t, e_t, last_change_t) |

References

- Sweeney, L. k-Anonymity: A Model for Protecting Privacy. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl. Based Syst. 2002, 10, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machanavajjhala, A.; Kifer, D.; Gehrke, J.; Venkitasubramaniam, M. l-Diversity: Privacy Beyond k-Anonymity. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2007, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, T.; Venkatasubramanian, S. t-Closeness: Privacy Beyond k-Anonymity and l-Diversity. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Istanbul, Turkey, 15–20 April 2007; pp. 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.; Kim, S. SUHDSA: Secure, Useful, and High-Performance Data Stream Anonymization. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 9336–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). De-Identification of Personal Information; NIST Interagency/Internal Report (IR) 8053; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015.

- NIST SP 800-226; Guidelines for Evaluating Differential Privacy Guarantees. National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024.

- Gadotti, A.; Rocher, L.; Houssiau, F.; Cretu, A.; Montjoye, Y. Anonymization: The Imperfect Science of Using Data While Preserving Privacy. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finley, T.; Holohan, N.; O’Reilly, C.; Sim, N.; Zhivotovskiy, N. Slowly Scaling Per-Record Differential Privacy. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.18118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadani, S.P. A Survey of Differential Privacy for Spatiotemporal Datasets. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.15868v1. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2407.15868v1 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Feng, S.; Mohammady, M.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Qin, Z.; Hong, Y. DPI: Ensuring Strict Differential Privacy for Infinite Data Streaming. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.04738v2. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2312.04738v2 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Erlingsson, U.; Pihur, V.; Korolova, A. RAPPOR: Randomized aggregatable privacy-preserving ordinal response. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’14), Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 3–7 November 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Kulkarni, J.; Yekhanin, S. Collecting Telemetry Data Privately. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 3571–3580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Blocki, J.; Li, N.; Jha, S. Locally Differentially Private Protocols for Frequency Estimation. In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security ’17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–18 August 2017; USENIX Association: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017; pp. 729–745. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Xiao, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Hui, S.C.; Shin, H.; Shin, J.; Yu, G. Collecting and Analyzing Multidimensional Data with Local Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 35th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Macao, China, 8–11 April 2019; IEEE: Macao, China, 2019; pp. 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomichev, M.; Luthra, M.; Benndorf, M.; Agnihotri, P. No One Size (PPM) Fits All: Towards Privacy in Stream Processing Systems. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Distributed Event-Based Systems (DEBS’23), Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 27–30 June 2023; pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tao, J.; Zou, D. Privacy-Preserving Data Aggregation in IoTs: A Randomize-then-Shuffle Paradigm. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 97th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Spring), Florence, Italy, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamikara, M.A.P.; Bertok, P.; Liu, D.; Camtepe, S.; Khalil, I. An Efficient and Scalable Privacy-Preserving Algorithm for Big Data and Data Streams. Comput. Secur. 2019, 87, 101570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jafar, S.A. The Capacity of Private Information Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2017, 63, 4075–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Han, Y.; Pei, J.; Jiang, B.; Tao, Y.; Jia, Y. Continuous Privacy Preserving Publishing of Data Streams. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Extending Database Technology (EDBT’09), Saint Petersburg, Russia,24–26 March 2009; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Y. KIDS: K-Anonymization Data Stream Based on Sliding Window. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Future Computer and Communication (ICFCC 2010), Wuhan, China, 21–24 May 2010; IEEE: Beijing, China, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C.; McSherry, F.; Nissim, K.; Smith, A. Calibrating Noise to Sensitivity in Private Data Analysis. In Proceedings of the Third Theory of Cryptography Conference (TCC’06), New York, NY, USA, 4–7 March 2006; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 265–284. Available online: https://people.csail.mit.edu/asmith/PS/sensitivity-tcc-final.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Cunha, M.; Mendes, R.; Vilela, J.P. A Survey of Privacy-Preserving Mechanisms for Heterogeneous Data Types. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 41, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Ai, C.; Li, Y. Privacy Protection on Sliding Window of Data Streams. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing (CollaborateCom 2007), White Plains, NY, USA, 12 November 2007; IEEE: Orlando, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ooi, B.C.; Wang, W. Anonymizing Streaming Data for Privacy Protection. In Proceedings of the IEEE 24th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE 2008), Cancún, México, 7–12 April 2008; IEEE: Cancun, Mexico, 2008; pp. 1367–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopaoglu, U.; Abul, O. A Utility Based Approach for Data Stream Anonymization. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2020, 54, 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Carminati, B.; Ferrari, E.; Tan, K.L. CASTLE: Continuously Anonymizing Data Streams. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2011, 8, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakerzadeh, H.; Osborn, S.L. FAANST: Fast Anonymizing Algorithm for Numerical Streaming Data. In DPM 2010 and SETOP 2010: Data Privacy Management and Autonomous Spontaneous Security, Athens, Greece, 23 September 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, Q. Fast Clustering-Based Anonymization Approaches with Time Constraints for Data Streams. Knowl. Based Syst. 2013, 46, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Sung, M.K.; Chung, Y.D. A Framework to Preserve the Privacy of Electronic Health Data Streams. J. Biomed. Inform. 2014, 50, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekli, J.; Al Bouna, B.; Issa, Y.B.; Kamradt, M.; Haraty, R. (k, l)-Clustering for Transactional Data Streams Anonymization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security Practice and Experience (ISPEC 2018), Tokyo, Japan, 25–27 September 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 544–556. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhameed, S.A.; Moussa, S.M.; Khalifa, M.E. Restricted Sensitive Attributes-Based Sequential Anonymization (RSA-SA) Approach for Privacy-Preserving Data Stream Publishing. Knowl. Based Syst. 2019, 164, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakpere, A.B.; Kayem, A.V.D.M. Adaptive Buffer Resizing for Efficient Anonymization of Streaming Data with Minimal Information Loss. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP), Angers, France, 9–11 February 2015; IEEE: Porto, Portugal, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Otgonbayar, A.; Pervez, Z.; Dahal, K.; Eager, S. K-VARP: K-Anonymity for Varied Data Streams via Partitioning. Inf. Sci. 2018, 467, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otgonbayar, A.; Pervez, Z.; Dahal, K. Toward Anonymizing IoT Data Streams via Partitioning. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 13th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc Sensor Systems (MASS), Brasília, Brazil, 10–13 October 2016; pp. 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavkin, M.; Last, M. Preserving Differential Privacy and Utility of Non-Stationary Data Streams. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Singapore, 17–20 November 2018; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Soria-Comas, J.; Mulero-Vellido, R. Steered Microaggregation as a Unified Primitive to Anonymize Data Sets and Data Streams. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 14, 3298–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.; Vassio, L.; Trevisan, M.; Leonardi, E.; Mellia, M. Practical Anonymization for Data Streams: Z-Anonymity and Relation with k-Anonymity. Perform. Eval. 2023, 159, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favale, T.; Trevisan, M.; Drago, I.; Mellia, M. α-MON: Traffic Anonymizer for Passive Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 18, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, A.R.S.; Ghaffarian, H.A. New Fast Framework for Anonymizing IoT Stream Data. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Internet of Things and Applications (IoT’21), Isfahan, Iran, 19–20 May 2021; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groneberg, P.; Nuñez von Voigt, S.; Janke, T.; Loechel, L.; Wolf, K.; Grünewald, E.; Pallas, F. k_s-Anonymization for Streaming Data in Apache Flink. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES 2025); Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Ghent, Belgium, 11–14 August 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groneberg, P.; Germanus, R. Analyzing Continuous k_s-Anonymization for Smart Meter Data. In Proceedings of the Computer Security—ESORICS 2023 International Workshops, The Hague, The Netherlands, 25–29 September 2023; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14398, pp. 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsinejad, H.; Ghasem-Aghaee, N.; Karaminezhad, M.; Nezamabadi, H. Representing a Model for the Anonymization of Big Data Stream Using In-Memory Processing. Ann. Data Sci. 2025, 12, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flávio, N.; Rafael, S.; Juliana, S.; Michel, B.; Vinicius, G. Data Privacy in the Internet of Things Based on Anonymization: A Review. J. Comput. Secur. 2023, 31, 261–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, A.; Mukunda, K.; Chakravarthy, S. Privacy and Anonymity for Multilayer Networks: A Reflection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Ninth International Conference on Big Data Computing, Service and Applications (BigDataService), Athens, Greece, 17–20 July 2023; pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Viñas, J.; Fernandez, I.O.; Martínez, E.S. Hexanonymity: A Scalable Geo-Positioned Data Clustering Algorithm for Anonymisation Purposes. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), Delft, The Netherlands, 3–7 July 2023; pp. 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, B.; Rolla, V.; Santos, R. INCOGNITUS: A Toolbox for Automated Clinical Notes Anonymization. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2–4 May 2023; pp. 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 20889; Privacy Enhancing Data De-Identification Terminology and Classification of Techniques. ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- UCI. Machine Learning Repository. Adult Dataset. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/2/adult (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Lee, J.; Kim, S. Implementation and Performance Measurement of the SUHDSA (Secure, Useful, and High-performance Data-Stream Anonymization) + Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN 2024), Kailua-Kona, HI, USA, 29–31 July 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Configuration/Description | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset | UCI ADULT (Census Income) [48], 32,561 tuples, 14 attributes | Categorical examples: Education, Occupation, Native Country |

| QID | Education, Occupation, Native country | Fixed across all runs |

| SA | Income; l = 2: binary (≤50 K/>50 K); l = 3: 3 brackets (≤30, (30,60], >60); l = 5: 5 brackets (≤20, (20,40], (40,60], (60,80], >80); multibracket values are synthetically assigned; QIDs unchanged | Used to isolate the effect of l |

| Implementation/Environment | Python (common code base), Windows 11, i9-12900KS 3.40 GHz, RAM 64 GB | Same environment family as ICCCN’24 [49] |

| Window/Buffer | FIFO buffer, β: maximum allowed delay (maximum number of tuples held simultaneously) | β ∈ {10, 50, 100} |

| Parameter Grid | k ∈ {3, 10, 50}, β ∈ {10, 50, 100}, l ∈ {2, 3, 5} | |

| Delay Threshold δ Rule | Adaptive δ adjustment based on UBDSA joint minimization of average delay and IL | Applied equally to SUHDSA [4] and proposed method |

| UBDSA [25] (our reimplementation) | k-anonymity, CAIL distance, no l-diversity | δ adaptive adjustment |

| SUHDSA [4] (our reimplementation) | k-anonymity, CAIL-based fast aggregation/optimization, no l-diversity | δ adaptive adjustment (same as UBDSA) |

| Proposed Method (this work) | k-anonymity and l-diversity verification, dynamic reconfiguration (merge/swap), CAIL retained | δ adaptive adjustment (same) |

| Condition | Algorithm | Runtime (s), Mean ± SD | 95% CI (Mean) | Runtime, Min–Max | ΔRuntime (Proposed–SUHDSA), Mean | p-Value † (Corr.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 3, β = 100 | Proposed Algorithm (A) | 12.30 ± 2.10 | [9.70, 14.90] | 9.22–15.54 | +6.25 | 0.125 |

| SUHDSA (B) | 6.05 ± 1.10 | [4.69, 7.41] | 4.37–7.67 | - | - | |

| UBDSA | 33.70 ± 0.30 | [33.33, 34.07] | 33.24–34.15 | - | - | |

| k = 50, β = 100 | Proposed Algorithm (A) | 10.05 ± 1.10 | [8.69, 11.41] | 8.43–11.92 | +4.10 | 0.250 |

| SUHDSA (B) | 5.95 ± 1.05 | [4.65, 7.25] | 4.49–7.45 | - | - | |

| UBDSA | 32.80 ± 0.15 | [32.61, 32.99] | 32.64–32.95 | - | - |

| Condition | Algorithm | IL, Mean ± SD | 95% CI (Mean) | IL, Min–Max | ΔIL (Proposed–SUHDSA), Mean | p-Value † (Corr.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k = 3, β = 10 | Proposed Algorithm (A) | 0.62 ± 0.04 | [0.57, 0.67] | 0.54–0.70 | +0.13 | 0.125 |

| SUHDSA (B) | 0.49 ± 0.08 | [0.39, 0.59] | 0.36–0.61 | - | - | |

| UBDSA | 0.98 ± 0.00 | [0.98, 0.98] | 0.98–0.98 | - | - | |

| k = 10, β = 10 | Proposed Algorithm (A) | 0.64 ± 0.06 | [0.57, 0.71] | 0.55–0.75 | +0.06 | 0.250 |

| SUHDSA (B) | 0.58 ± 0.11 | [0.44, 0.72] | 0.36–0.72 | - | - | |

| UBDSA | 0.98 ± 0.00 | [0.98, 0.98] | 0.98–0.98 | - | - |

| Algorithm | LSR (%) | H(SA|G) Mean (Bits) | H(SA|G) Min (Bits) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (3, 10, 2) | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 96 | 0.78 | 0.32 |

| SUHDSA (k-only) | 61 | 0.55 | 0.00 | |

| UBDSA (k-only) | 48 | 0.49 | 0.00 | |

| (10, 10, 2) | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 99 | 0.85 | 0.42 |

| SUHDSA (k-only) | 75 | 0.62 | 0.00 | |

| UBDSA (k-only) | 58 | 0.52 | 0.00 | |

| (3, 100, 2) | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 98 | 0.84 | 0.38 |

| SUHDSA (k-only) | 70 | 0.60 | 0.00 | |

| UBDSA (k-only) | 55 | 0.52 | 0.00 | |

| (50, 100, 2) | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 100 | 0.90 | 0.55 |

| SUHDSA (k-only) | 88 | 0.72 | 0.00 | |

| UBDSA (k-only) | 70 | 0.60 | 0.00 |

| Block | l | Algorithm | Runtime (s), Avg | IL (0–1), Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselines | – | SUHDSA (k-only) | 6.17 | 0.46 |

| – | UBDSA (k-only) | 33.14 | 0.99 | |

| Proposed (l sweep) | 2 | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 7.92 | 0.48 |

| 3 | 8.41 | 0.52 | ||

| 5 | 9.16 | 0.64 |

| Block | l | Algorithm | Runtime (s), Avg | IL (0–1), Avg | LSR (%) | H(SA|G) Mean (Bits) | H(SA|G) Min (Bits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselines | – | SUHDSA (k-only) | 6.17 | 0.46 | 12 | 0.95 | 0.20 |

| 2 | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 8.30 | 0.50 | 92 | 0.82 | 0.45 | |

| Proposed (l sweep) | 3 | Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 8.95 | 0.55 | 80 | 1.30 | 0.88 |

| 5 | 9.90 | 0.69 | 62 | 1.75 | 1.05 |

| Mode | Throughput (Events/s) | p50 (ms) | p95 (ms) | p99 (ms) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing-only ( ms) | 20,000 | 18 | 35 | 60 | Ingress → sink (including grouping/reconfiguration; excludes physical network) |

| +Synthetic network ( ms) | 19,000 | 20 | 38 | 65 | Ingress → sink including +2 ms/record |

| +Synthetic network ( ms) | 17,500 | 25 | 45 | 75 | Ingress → sink including +5 ms/record |

| Scenario | Method | Runtime (s) | IL (0–1) | LSR (%) | Entropy H(SA|G) Mean (Bits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skew (SA majority ratio ≈ 0.85) | SUHDSA (k-only) | 6.25 ± 0.18 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 12 ± 4 | 0.28 ± 0.06 |

| Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 8.35 ± 0.26 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 92 ± 3 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | |

| Bursts (arrival spike ×5) | SUHDSA (k-only) | 6.40 ± 0.20 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 55 ± 7 | 0.50 ± 0.06 |

| Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 8.70 ± 0.32 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 95 ± 2 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | |

| Drift (strong, gradual drift) | SUHDSA (k-only) | 6.35 ± 0.19 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 45 ± 8 | 0.46 ± 0.07 |

| Proposed (k + l, reconfig) | 8.55 ± 0.30 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 94 ± 2 | 0.83 ± 0.05 |

| Scenario | Method | Throughput (Events/s) | p50 (ms) | p95 (ms) | p99 (ms) | ρ (Reconfigs/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skew (≈0.85) | SUHDSA | 20,400 ± 700 | 18 ± 1 | 36 ± 2 | 65 ± 5 | 0.00 |

| Proposed | 18,100 ± 800 | 20 ± 1 | 46 ± 3 | 95 ± 8 | 1.40 ± 0.20 | |

| Bursts (×5) | SUHDSA | 19,200 ± 900 | 19 ± 1 | 44 ± 4 | 85 ± 10 | 0.00 |

| Proposed | 16,200 ± 1000 | 23 ± 2 | 62 ± 6 | 140 ± 15 | 1.85 ± 0.25 | |

| Drift (strong) | SUHDSA | 19,600 ± 800 | 19 ± 1 | 42 ± 3 | 78 ± 9 | 0.00 |

| Proposed | 17,100 ± 900 | 22 ± 2 | 54 ± 5 | 112 ± 12 | 1.30 ± 0.20 |

| Factor | Setting | Runtime (s) Mean ± SD | IL Mean ± SD | LSR Mean ± SD | Entropy Mean ± SD | ΔRuntime (Setting–Default) | p † (RT) | ΔIL (Setting–Default) | p † (IL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | Default | 8.40 ± 0.30 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 99 ± 1 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.00 | – | 0.000 | – |

| 0.3 | 7.90 ± 0.25 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 98 ± 1 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | −0.50 | 0.250 | +0.040 | 0.250 | |

| 0.5 | 8.10 ± 0.28 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 98 ± 1 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | −0.30 | 0.500 | +0.020 | 0.500 | |

| 0.9 | 8.85 ± 0.35 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 99 ± 1 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | +0.45 | 0.250 | −0.020 | 0.250 | |

| c | 1 | 8.05 ± 0.27 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 97 ± 2 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | −0.35 | 0.500 | +0.030 | 0.500 |

| 5 | 9.10 ± 0.40 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 99 ± 1 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | +0.70 | 0.125 | −0.010 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | 8.95 ± 0.35 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 99 ± 1 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | +0.55 | 0.250 | −0.020 | 0.250 | |

| 4 | 8.10 ± 0.30 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 98 ± 1 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | −0.30 | 0.500 | +0.030 | 0.500 |

| Runtime (s) Mean ± SD | IL Mean ± SD | LSR Mean ± SD | Entropy Mean ± SD | p95 (ms) Mean ± SD | p99 (ms) Mean ± SD | Throughput Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p † (p99) | ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFF | 8.40 ± 0.30 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 99 ± 1 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 55 ± 5 | 120 ± 12 | 17,200 ± 900 | 1.45 ± 0.20 | – | – |

| ON | 8.25 ± 0.28 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 98 ± 1 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 50 ± 4 | 105 ± 10 | 17,800 ± 950 | 1.10 ± 0.18 | 0.250 | 0.250 |

| (k, l) | Re-ID@1 (%) | Re-ID@5 (%) | Attribute Disclosure (%) | (1/k) Reference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (10, 2) | 7.9 | 25.0 | 38.0 | 10.0 |

| (20, 3) | 5.0 | 18.0 | 24.0 | 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Kim, S. Real-Time Stream Data Anonymization via Dynamic Reconfiguration with l-Diversity-Enhanced SUHDSA. Sensors 2026, 26, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010095

Lee J, Kim S. Real-Time Stream Data Anonymization via Dynamic Reconfiguration with l-Diversity-Enhanced SUHDSA. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010095

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jiyeon, and Soonseok Kim. 2026. "Real-Time Stream Data Anonymization via Dynamic Reconfiguration with l-Diversity-Enhanced SUHDSA" Sensors 26, no. 1: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010095

APA StyleLee, J., & Kim, S. (2026). Real-Time Stream Data Anonymization via Dynamic Reconfiguration with l-Diversity-Enhanced SUHDSA. Sensors, 26(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010095