Optical Fiber pH and Dissolved Oxygen Sensors for Bioreactor Monitoring: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Traditional Monitoring Methods and Their Limitations

2.1. History and Application of Traditional Monitoring Methods

2.2. Limitations of Traditional Monitoring Methods

2.2.1. Environmental Interference

2.2.2. Regular Calibration Requirement

2.2.3. Adaptability Concerns

3. Overview of Optical Fiber Sensor Technology

3.1. Basic Principles of Optical Fiber Sensors

3.2. Advantages of Optical Fiber Sensors

3.2.1. High Sensitivity

3.2.2. Remote Sensing Capability

3.2.3. Miniaturization and Flexibility

4. Application of Optical Fiber pH Sensors in Bioreactors

4.1. Significance of pH in Bioprocessing Processes

4.2. Working Principle of Optical Fiber pH Sensors

4.2.1. Indicator-Based Absorption and Fluorescence Sensors

4.2.2. Hydrogel-Based Swelling and Refractive-Index Sensors

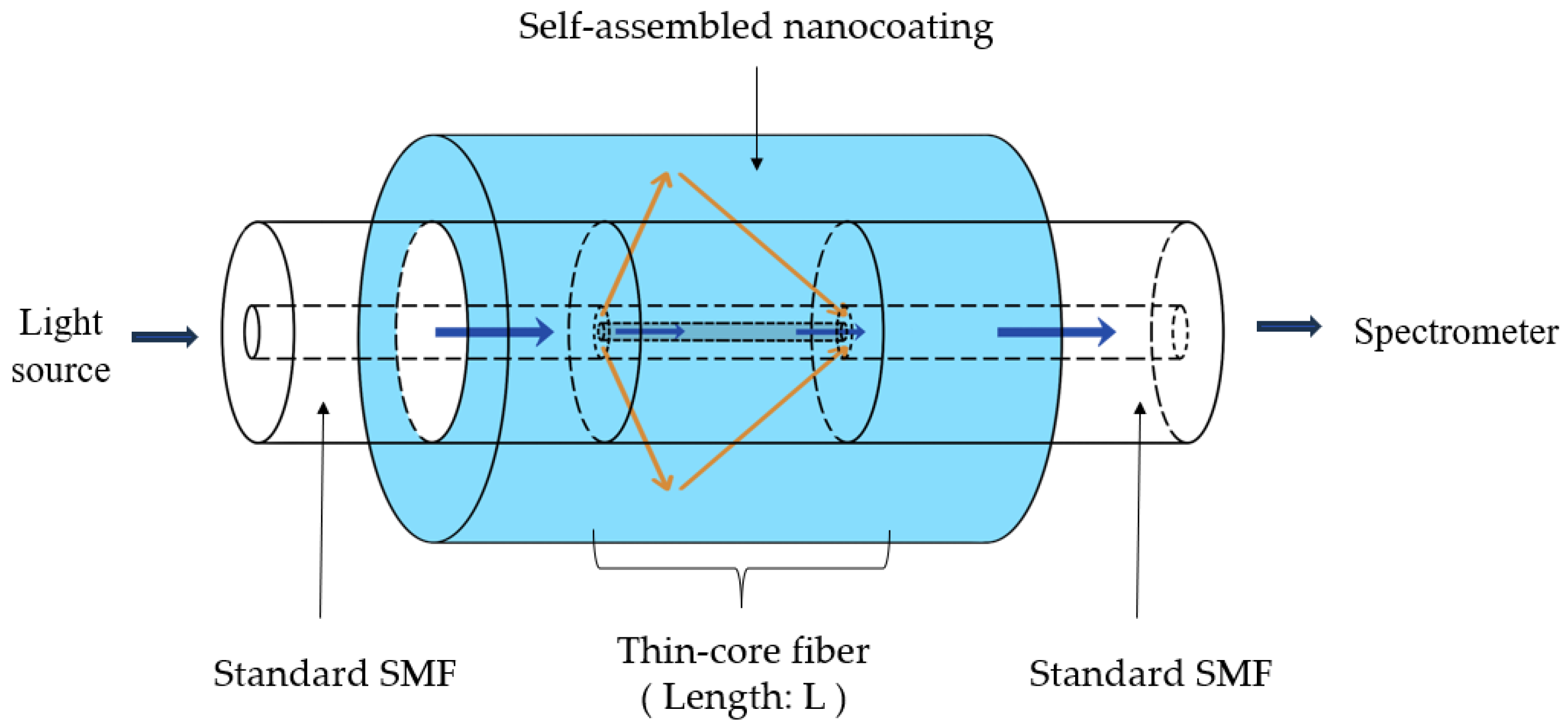

4.2.3. Interferometric and Grating-Based Fiber Sensors

4.3. Advantages of Optical Fiber pH Sensors

4.3.1. Non-Invasive Measurement

4.3.2. No Contamination Risk

4.3.3. Rapid Response Time

4.3.4. Reduced Maintenance

4.3.5. Adaptability to High-Density Cultivation

4.3.6. Flexible Deployment

4.4. Typical Application Cases of Optical Fiber pH Sensors

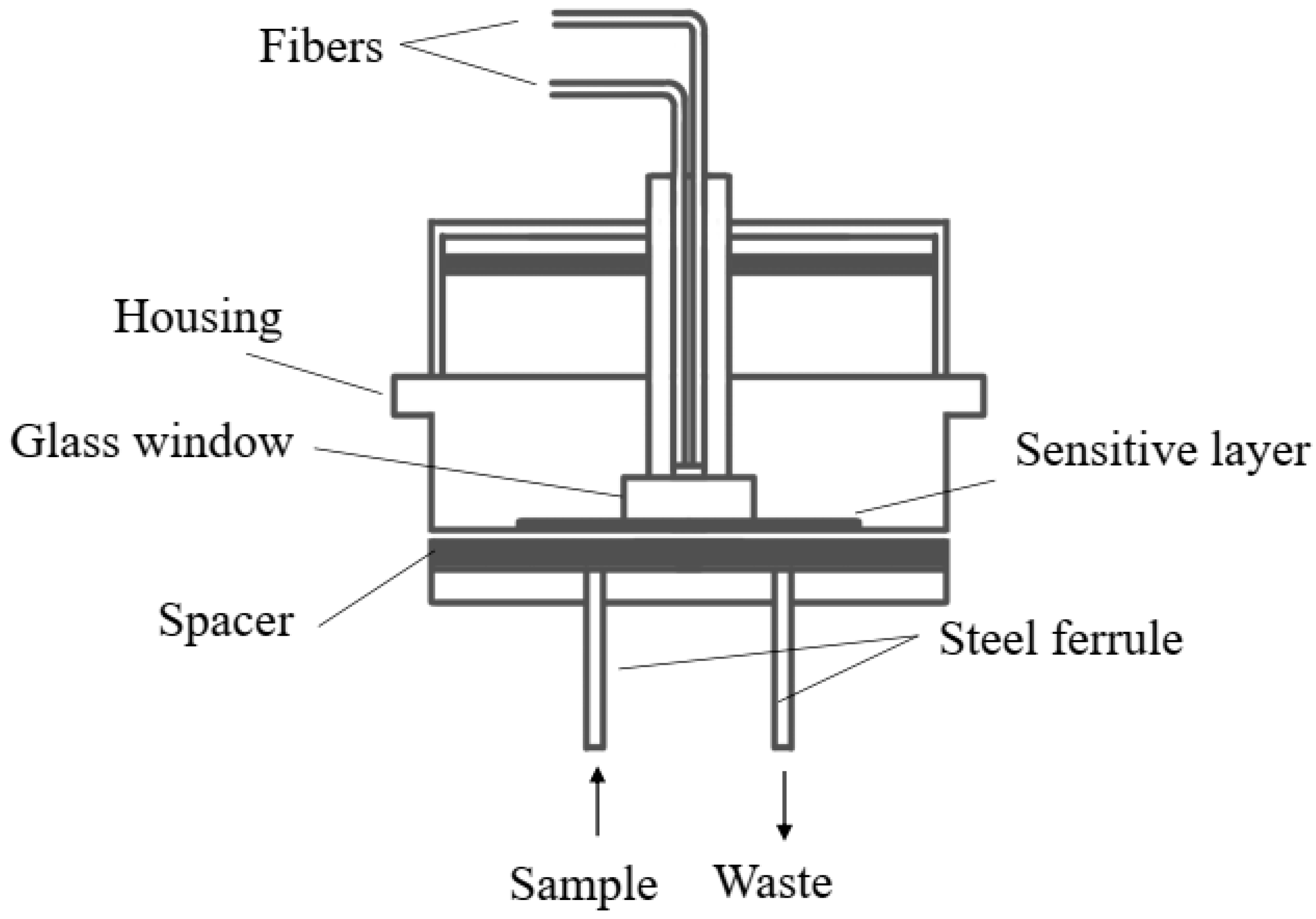

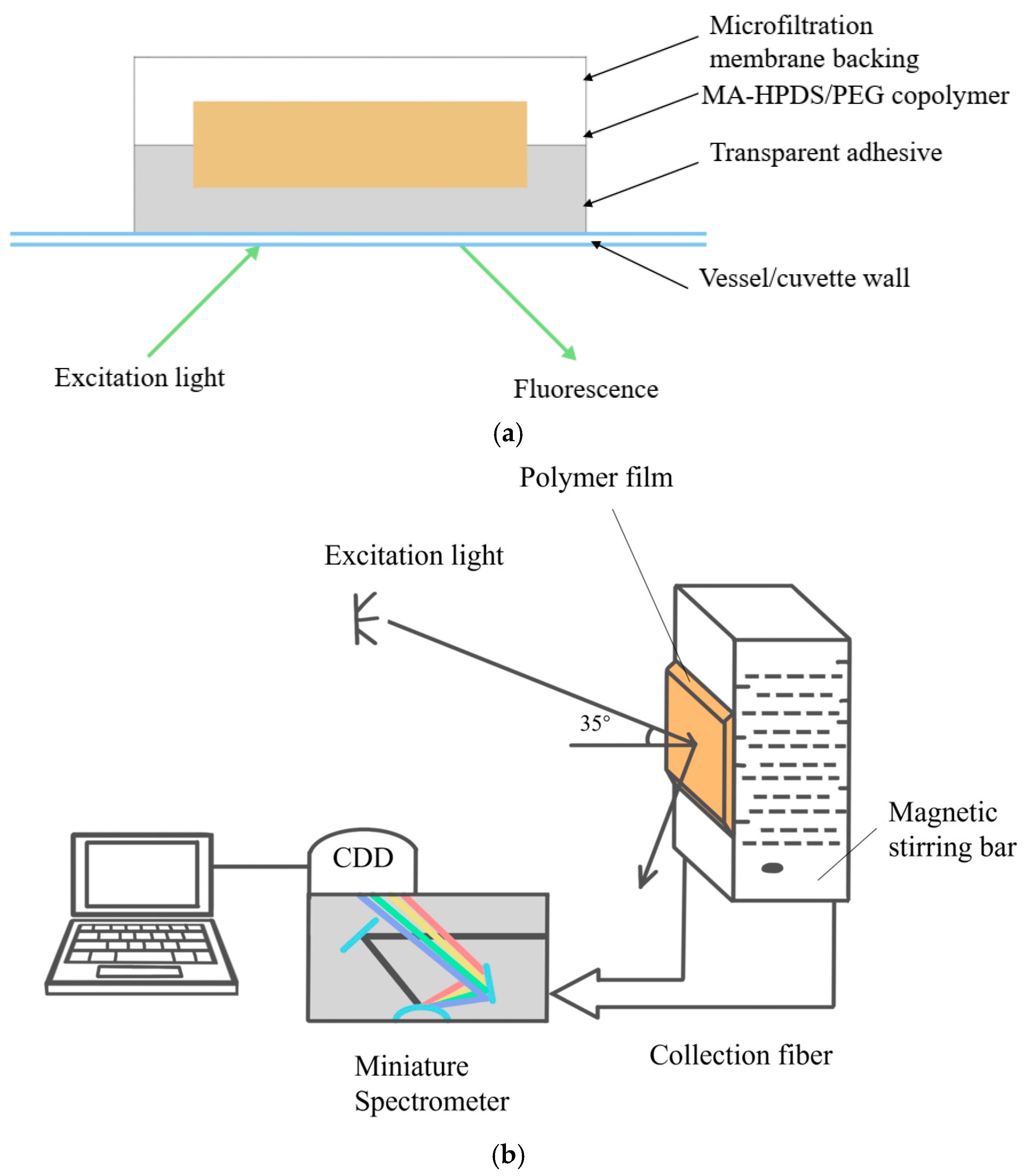

4.4.1. Indicator-Based Fiber pH Sensors in Bioreactors and Shake Flasks

4.4.2. Interferometric and Grating-Based Fiber pH Sensors

4.4.3. Hydrogel-Based Fiber pH Sensors

4.4.4. Comparative Assessment and Design Considerations

5. Application of Optical Fiber DO Sensors in Bioreactors

5.1. Significance of DO in Bioprocessing Processes

5.2. Working Principles of Optical Fiber Dissolved Oxygen Sensors

5.2.1. Oxygen-Dependent Luminescence Quenching

5.2.2. Immobilization Matrices and Fiber Integration

5.3. Advantages of Optical Fiber DO Sensors

5.3.1. Real-Time, Continuous Monitoring

5.3.2. Progress in the Miniaturization and Integration of Sensing Technologies

5.3.3. High Sensitivity and Swift Response

5.3.4. Strong Contamination Resistance and Suitability for Complex Media

5.4. Typical Application Cases of Optical Fiber DO Sensors

6. Other Optical Fiber Sensor Applications in Bioreactors

6.1. Temperature Sensors

6.2. Pressure Sensors

6.3. Biomass Concentration Sensors

6.4. Monitoring Other Parameters

7. Challenges and Future Prospects

7.1. Key Challenges

7.1.1. Sensor Robustness and Coating Stability in Real Bioprocess Media

7.1.2. Calibration, Cross-Sensitivities, and Standardization

7.1.3. Mechanical Integration with Stainless-Steel and Single-Use Bioreactors

7.1.4. Data Volume, Signal Processing, and Control Integration

7.1.5. Cost, Complexity, and Required Expertise

7.1.6. Regulatory and Validation Barriers

7.2. Future Prospects and Research Directions

7.2.1. Multi-Parameter and Distributed Sensing Architectures

7.2.2. Advanced Functional Materials and Packaging Strategies

7.2.3. Integration with PAT, Soft Sensors, and AI-Driven Control

7.2.4. Standardization, Benchmarking, and Regulatory Engagement

7.2.5. Application Expansion Across Scales and Modalities

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samaras, J.J.; Micheletti, M.; Ding, W. Transformation of biopharmaceutical manufacturing through single-use technologies: Current state, remaining challenges, and future development. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2022, 13, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jossen, V.; Eibl, R.; Eibl, D. Single-Use Bioreactors—An Overview. In Single-Use Technology in Biopharmaceutical Manufacture; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dürauer, A.; Jungbauer, A.; Scharl, T. Monitoring product quantity, purity, and potency of biopharmaceuticals in real-time by predictive chemometrics and soft sensors. Authorea Prepr. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.A.; Gottschalk, U. Single-use disposable technologies for biopharmaceutical manufacturing. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, N.; Richards, J. Current status and future trends for disposable technology in the biopharmaceutical industry. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, I.; Busse, C.; Kopatz, J.; Neumann, H.; Beutel, S.; Scheper, T. Polysialic acid production using Escherichia coli K1 in a disposable bag reactor. Eng. Life Sci. 2017, 17, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasalathanthri, D.P.; Rehmann, M.S.; Song, Y.; Gu, Y.; Mi, L.; Shao, C.; Chemmalil, L.; Lee, J.; Ghose, S.; Borys, M.C.; et al. Technology outlook for real-time quality attribute and process parameter monitoring in biopharmaceutical development—A review. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 3182–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.C.P.; Cabral, T.D.; Mendes, B.F.; Silva, V.A.; Tambourgi, E.B.; Fujiwara, E. Technical and economic viability analysis of optical fiber sensors for monitoring industrial bioreactors. Eng. Proc. 2020, 2, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Rösner, L.S.; Walter, F.; Ude, C.; John, G.T.; Beutel, S. Sensors and techniques for online determination of cell viability in bioprocess monitoring. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arain, S.; John, G.T.; Krause, C.; Gerlach, J.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Klimant, I. Characterization of microtiter plates with integrated optical sensors for oxygen and pH, and their applications to enzyme activity screening, respirometry, and toxicological assays. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 113, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.A.; Ge, X.; Kostov, Y.; Brorson, K.A.; Moreira, A.R.; Rao, G. Comparisons of optical pH and dissolved oxygen sensors with traditional electrochemical probes during mammalian cell culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 97, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, H.; Luna, M.F.; von Stosch, M.; Cruz Bournazou, M.N.; Polotti, G.; Morbidelli, M.; Butté, A.; Sokolov, M. Bioprocessing in the digital age: The role of process models. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 16, 2000013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Bozal-Palabiyik, B.; Unal, D.N.; Erkmen, C.; Siddiq, M.; Shah, A.; Uslu, B. Molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) combined with nanomaterials as electrochemical sensing applications for environmental pollutants. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 36, e00176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, D. Optical Oxygen Sensing Based on Ruthenium and Porphyrin Complexes. Doctoral dissertation, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel, S.; Henkel, S. In situ sensor techniques in modern bioprocess monitoring. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 1493–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesen, N.; Eibl, R. Single-use bag systems for storage, transportation, freezing, and thawing. In Single-Use Technology in Biopharmaceutical Manufacture; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, A.S.; Saxena, N.; Jesubalan, N.G. Digitization in bioprocessing: The role of soft sensors in monitoring and control of downstream processing for production of biotherapeutic products. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2022, 12, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocarro-Ruiz, B.; Fernández-Gavela, A.; Herranz, S.; Lechuga, L.M. Nanophotonic label-free biosensors for environmental monitoring. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 46, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Durairaj, S.; Prins, S.; Chen, A. Nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors and biosensors for the detection of pharmaceutical compounds. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 176, 112836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, A.A.; Malhotra, B.D. Current progress in organic-inorganic hetero-nano-interfaces based electrochemical biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 462, 214518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, C.; Biechele, P.; de Vries, I.; Reardon, K.F.; Solle, D.; Scheper, T. Sensors for disposable bioreactors. Eng. Life Sci. 2017, 17, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara, P.; Farrell, A.; Bones, J.; Twomey, K. Staying alive! Sensors used for monitoring cell health in bioreactors. Talanta 2018, 176, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Cao, Z.; Gao, H.; Yu, D.; Qiao, X. Optical fiber ultrasonic sensor based on partial filling PDMS in hollow-core fiber. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 167, 109648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, J.K.; Mo, H.; Zhou, X.; Han, Y. Fiber optic sensing technology and vision sensing technology for structural health monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wu, R.; Zhou, J.; Biondi, A.; Cao, L.; Wang, X. Fiber lateral pressure sensor based on Vernier-effect improved Fabry-Perot interferometer. Sensors 2022, 22, 7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.M.; Guo, X.; Wu, R.; Cao, L.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Q.; Yu, T.; Goplan, B.; Hanna, T.; Ivey, J.; et al. Smart textile embedded with distributed fiber optic sensors for railway bridge long-term monitoring. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2023, 80, 103382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Biondi, A.; Cao, L.; Gandhi, H.; Abedin, S.; Cui, G.; Yu, T.; Wang, X. Composite bridge girders structure health monitoring based on the distributed fiber sensing textile. Sensors 2023, 23, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Guo, X.; Du, C.; Lou, X.; Cao, C.; Wang, X. A fiber optic acoustic pyrometer for temperature monitoring in an exhaust pipe of a boiler. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2019, 31, 1707–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, I.; Hosoe, S.; Hikima, Y.; Watari, M.; Ohshima, M. In-line monitoring of the physical blowing agent concentration by transmission near-infrared spectroscopy with high-pressure resistance fiber optic probes for foam injection molding processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 12365–12374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovera, A.; Tancau, A.; Boetti, N.; Dalla Vedova, M.D.L.; Maggiore, P.; Janner, D. Fiber optic sensors for harsh and high radiation environments in aerospace applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Guo, X.; Du, C.; Cao, C.; Wang, X. A fiber optic ultrasonic sensing system for high temperature monitoring using optically generated ultrasonic waves. Sensors 2019, 19, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wu, N.; Tian, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Barringhaus, K.; Wang, X. Miniature Fabry-Perot fiber optic sensor for intravascular blood temperature measurements. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 1810–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wu, N.; Tian, Y.; Niezrecki, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Rapid miniature fiber optic pressure sensors for blast wave measurements. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2013, 51, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulber, R.; Frerichs, J.G.; Beutel, S. Optical sensor systems for bioprocess monitoring. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 376, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, J.T.; Flores, N.; Bolívar, F.; Lara, A.R.; Ramírez, O.T. Physiological effects of pH gradients on Escherichia coli during plasmid DNA production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, R.; Serresi, M.; Luin, S.; Beltram, F. Green fluorescent protein based pH indicators for in vivo use: A review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 393, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, M.; Veeramuthu, L.; Liang, F.C.; Chen, W.C.; Cho, C.J.; Chen, C.W.; Chen, J.Y.; Yan, Y.; Chang, S.H.; Kuo, C.C. Evolution of electrospun nanofibers fluorescent and colorimetric sensors for environmental toxicants, pH, temperature, and cancer cells—A review with insights on applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 397, 125431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, J.R.; Remington, S.J. Development of a family of redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein indicators for use in relatively oxidizing subcellular environments. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 8678–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fang, C. Uncovering the hidden excited state toward fluorescence of an intracellular pH indicator. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6698–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, R.; Lee, K.; Lye, G.J. Development of a miniature bioreactor model to study the impact of pH and DOT fluctuations on CHO cell culture performance as a tool to understanding heterogeneity effects at large-scale. Biotechnol. Prog. 2022, 38, e3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, D. Protein deamidation in biopharmaceutical manufacture: Understanding, control and impact. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, M.; Salih, A.E.; Muñoz, M.G.; Alam, F.; AlQattan, B.; Antonysamy, D.S.; Zaki, M.F.; Yetisen, A.K.; Park, S.; Wilkinson, T.D.; et al. Optical fiber sensors: Working principle, applications, and limitations. Adv. Photonics Res. 2022, 3, 2100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, T.; Saccomandi, P.; Li, B.; Wang, F.; Cheng, T. SPR fiber optic sensor for simultaneous temperature and humidity measurement using AuNPs. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv), Milano, Italy, 29–31 May 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, J.; Belz, M.; Klein, K.-F.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V. Fast response time fiber optical pH and oxygen sensors. In Proceedings of the SPIE Photonics Europe, Strasbourg, France, 29 March–2 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, B.M.; Sun, K.; Zeimpekis, I.; Skylaris, C.K.; Green, N.G. Field-effect sensors—From pH sensing to biosensing: Sensitivity enhancement using streptavidin-biotin as a model system. Analyst 2017, 142, 4173–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, A.; Pisania, A.; Abdelgadir, E.; Milling, J.; Marvell, T.; Steininger, B. Scale-up and comparison studies evaluating disposable bioreactors and probes. BioPharm. Int. 2009, 22, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mandenius, C.F. Design of monitoring and sensor systems for bioprocesses by biomechatronic methodology. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2012, 35, 1925–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluma, A.; Höpfner, T.; Prediger, A.; Glindkamp, A.; Beutel, S.; Scheper, T. Process analytical sensors and image-based techniques for single-use bioreactors. Eng. Life Sci. 2011, 11, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermis, H.R.; Kostov, Y.; Harms, P.; Rao, G. Dual excitation ratiometric fluorescent pH sensor for noninvasive bioprocess monitoring: Development and application. Biotechnol. Prog. 2002, 18, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermis, H.R.; Kostov, Y.; Rao, G. Rapid method for the preparation of a robust optical pH sensor. Analyst 2003, 128, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidgans, B.M.; Krause, C.; Klimant, I.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Fluorescent pH sensors with negligible sensitivity to ionic strength. Analyst 2004, 129, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, C.; Varonier, J.; Jossen, V.; Eibl, R.; Eibl, D. Novel probes for pH and dissolved oxygen measurements in cultivations from millilitre to benchtop scale. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9069–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsom, S.; Budwong, A.; Wongsa, C.; Sangngam, P.; Baipaywad, P.; Manaspon, C.; Auephanwiriyakul, S.; Theera-Umpon, N.; Paengnakorn, P. Automatic programmable bioreactor with pH monitoring system for tissue engineering application. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Lu, X.; Tian, H.; Zhu, W. A long wavelength fluorescent hydrophilic copolymer based on naphthalenediimide as pH sensor with broad linear response range. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 2524–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, N.H.; Schmidt, M.; Krause, C.; Weuster-Botz, D. Evaluation of fluorimetric pH sensors for bioprocess monitoring at low pH. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaegh, S.A.M.; De Ferrari, F.; Zhang, Y.S.; Nabavinia, M.; Mohammad, N.B.; Ryan, J.; Pourmand, A.; Laukaitis, E.; Sadeghian, R.B.; Nadhman, A.; et al. A microfluidic optical platform for real-time monitoring of pH and oxygen in microfluidic bioreactors and organ-on-chip devices. Biomicrofluidics 2016, 10, 044111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, J.; Oeggl, R.; Janzen, N.H.; Abad, S.; Reinisch, D. Process adapted calibration improves fluorometric pH sensor precision in sophisticated fermentation processes. Eng. Life Sci. 2020, 20, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glindkamp, A.; Riechers, D.; Rehbock, C.; Hitzmann, B.; Scheper, T.; Reardon, K.F. Sensors in disposable bioreactors—Status and trends. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2010, 115, 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- Holobar, A.; Weigl, B.H.; Trettnak, W.; Beneš, R.; Lehmann, H.; Rodriguez, N.V.; Wollschlager, A.; O’Leary, P.; Raspor, P.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Experimental results on an optical pH measurement system for bioreactors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1993, 11, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, J.I.; Baganz, F. Miniature bioreactors: Current practices and future opportunities. Microb. Cell Fact. 2006, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimant, I.; Huber, C.; Liebsch, G.; Neurauter, G.; Stangelmayer, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S. New Trends in Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 214–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, E.Y.; Pappas, D.; Jeevarajan, A.S.; Anderson, M.M. Evaluation of the Paratrend multi-analyte sensor for potential utilization in long-duration automated cell culture monitoring. Biomed. Microdevices 2004, 6, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, G.; Guenther, M.; Sorber, J.; Suchaneck, G.; Arndt, K.F.; Richter, A. Chemical and pH sensors based on the swelling behavior of hydrogels. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 111–112, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Yin, M.; Zhang, A.; Qian, J.; He, S. Low-cost high performance fiber-optic pH sensor based on thin-core fiber modal interferometer. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 22296–22302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Han, S.G.; Lee, W. Inverse opal pH sensors with various protic monomers copolymerized with polyhydroxyethylmethacrylate hydrogel. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 762, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, J.L. Long Period Grating-Based pH Sensors for Corrosion Monitoring. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Corres, J.M.; Villar, I.D.; Matias, I.R.; Arregui, F.J. Fiberoptic pH-sensors in long period fiber gratings using electrostatic self-assembly. Opt. Lett. 2007, 32, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.; Paschew, G.; Klatt, S.; Liening, J.; Arndt, K.F. Review on hydrogel-based pH sensors and microsensors. Sensors 2008, 8, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, A.K.; Singh, V.K. A wide range and highly sensitive optical fiber pH sensor using polyacrylamide hydrogel. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2017, 39, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, C.; Kolle, C.; McEvoy, A.K.; Dowling, D.L.; Cafolla, A.A.; Cullen, S.J.; MacCraith, B.D. Phase fluorometric dissolved oxygen sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 74, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, Y. Lock-in based phase fluorometric dissolved oxygen sensor interface with 4 kHz-160 kHz tunable excitation frequency and frequency error calibration. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 73573–73582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusterer, A.; Krause, C.; Kaufmann, K.; Arnold, M.; Weuster-Botz, D. Fully automated single-use stirred-tank bioreactors for parallel microbial cultivations. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2008, 31, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambot, S.B.; Holavanahali, R.; Lakowicz, J.R.; Carter, G.M.; Rao, G. Phase fluorometric sterilizable optical oxygen sensor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1994, 43, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, M.A.; Brorson, K.A.; Moreira, A.R.; Rao, G. Comparisons of optically monitored small-scale stirred tank vessels to optically controlled disposable bag bioreactors. Microb. Cell Fact. 2009, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.G.; Jeevarajan, A.S.; Anderson, M.M. Long-term continuous monitoring of dissolved oxygen in cell culture medium for perfused bioreactors using optical oxygen sensors. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 86, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, T. Qualitative Comparison of Optical and Electrochemical Sensors for Measuring Dissolved Oxygen in Bioreactors. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Q.; Jia, D.; Liu, T. Ratiometric optical fiber dissolved oxygen sensor based on fluorescence quenching principle. Sensors 2022, 22, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, V.; Blaikie, R.J.; David, T. In-situ optical oxygen sensing for bio-artificial liver bioreactors. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Singapore, 3–6 December 2008; pp. 778–781. [Google Scholar]

- Naciri, M.; Kuystermans, D.; Al-Rubeai, M. Monitoring pH and dissolved oxygen in mammalian cell culture using optical sensors. Cytotechnology 2008, 57, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simler, J.; Kittredge, A.; Cunningham, M.; Mumira, J.; Rings, J.; Thiel, K.; Berudgo, C.; Chalmers, J.J.; Hahn, J.; Rapiejko, P.J. Mobius SensorReady Technology: A Novel Approach to Monitoring Single-Use Bioreactors; Technical Report; Merck Millipore: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kostov, Y.; Van Houten, K.A.; Harms, P.; Pilato, R.S.; Rao, G. Unique oxygen analyzer combining a dual emission probe and a low-cost solid-state ratiometric fluorometer. Appl. Spectrosc. 2000, 54, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, L.; Kostov, Y.; Harms, P.; Rao, G. Noninvasive measurement of dissolved oxygen in shake flasks. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2002, 80, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Rao, G. A study of oxygen transfer in shake flasks using a non-invasive oxygen sensor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003, 84, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillanders, R.N.; Tedford, M.C.; Crilly, P.J.; Bailey, R.T. Thin film dissolved oxygen sensor based on platinum octaethylporphyrin encapsulated in an elastic fluorinated polymer. Anal. Chim. Acta 2004, 502, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillanders, R.N.; Tedford, M.C.; Crilly, P.J.; Bailey, R.T. A composite thin film optical sensor for dissolved oxygen in contaminated aqueous environments. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 545, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, A.K.; McDonagh, C.M.; MacCraith, B.D. Dissolved oxygen sensor based on fluorescence quenching of oxygen-sensitive ruthenium complexes immobilized in sol-gel-derived porous silica coatings. Analyst 1996, 121, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, Z.M.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Wang, X.R.; Wong, K.Y. Characterization of ormosil film for dissolved oxygen-sensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 124, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.Y.; Tehan, E.C.; Tang, Y.; Bright, F.V. Stable sensors with tunable sensitivities based on class II xerogels. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.L.; Xiao, D.; Choi, M.M.F. Dissolved oxygen sensor based on fluorescence quenching of oxygen-sensitive ruthenium complex immobilized on silica-Ni-P composite coating. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 117, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-S.; Chuang, C.-Y. Ratiometric optical fiber dissolved oxygen sensor based on metalloporphyrin and CdSe quantum dots embedded in sol–gel matrix. J. Lumin. 2015, 167, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.M.; Dhawangale, A.; Chandra, S.; Shekhawat, L.K.; Rathore, A.S.; Mukherji, S. Polymer-coated fiber optic sensor as a process analytical tool for biopharmaceutical impurity detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 5120–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, N.S.; Bellini, R.; Bassani, I.; Vizzarro, A.; Azim, A.; Coti, C.; Barbieri, D.; Scapolo, M.; Viberti, D.; Verga, F.; et al. Innovative high pressure/high temperature, multi-sensing bioreactors system for microbial risk assessment in underground hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannazadeh, F. Model Predictive Control for Dissolved Oxygen and Temperature to Study Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Production in Bioreactor. Ph.D. Thesis, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, P.; Marques, M.P.C.; Szita, N.; Mayr, T. Integration and application of optical chemical sensors in microbioreactors. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 2693–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Lim, H.R.; Kim, Y.S.; Hoang, T.T.T.; Choi, J.; Jeong, G.J.; Kim, H.; Herbert, R.; Soltis, I.; et al. Large-scale smart bioreactor with fully integrated wireless multivariate sensors and electronics for long-term in situ monitoring of stem cell culture. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, T.; Burggraeve, A.; Fonteyne, M.; Saerens, L.; Remon, J.P.; Vervaet, C. Near infrared and Raman spectroscopy for the in-process monitoring of pharmaceutical production processes. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 417, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, A.; Wolfbeis, O.S.; Borisov, S.M. Optical sensing and imaging of pH values: Spectroscopies, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12357–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, C.; Deshpande, R.; Estes, S.; Francissen, K.; Joly, J.; Lubiniecki, A.; Munro, T.; Russell, R.; Wang, T.; Anderson, K. Industry view on the relative importance of “clonality” of biopharmaceutical-producing cell lines. Biologicals 2016, 44, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozawa, D.; Cho, S.Y.; Gong, X.; Nguyen, F.T.; Jin, X.; Lee, M.A.; Lee, H.; Zeng, A.; Xue, G.; Schacherl, J.; et al. A fiber optic interface coupled to nanosensors: Applications to protein aggregation and organic molecule quantification. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 8343–8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Fan, S.; Xing, W.; Liu, C. Microfluidic cell culture system studies and computational fluid dynamics. Math. Comput. Model. 2010, 52, 2036–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.G.; Park, K.M.; Jeong, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Baek, J.E.; Lee, H.W.; Jung, J.K.; Chung, B.H. Carbon nanotube-assisted enhancement of surface plasmon resonance signal. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 408, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, R. Recent optical sensing technologies for the detection of various biomolecules: Review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, H.; Kalita, P.; Gupta, S.; Sai, V.V.R. Plasmonic biosensors for bacterial endotoxin detection on biomimetic C-18 supported fiber optic probes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 129, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.D.; Verma, R.K. Surface plasmon resonance-based fiber optic sensors: Principle, probe designs, and some applications. J. Sens. 2009, 2009, 979761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.A.; Lipatnikov, K.A.; Nureev, I.I.; Morozov, O.G.; Sakhabutdinov, A.J. Fiber-optic sensors for complex monitoring of traction motors. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1327, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, A. Advanced Electronic and Optoelectronic Sensors, Applications, Modelling and Industry 5.0 Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Wang, J.; Kaushik, B.K.; Cheng, Z.; Kumar, R.; Wei, Z.; Li, X. Review of recent progress on silicon nitride-based photonic integrated circuits. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 195436–195450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lv, Z.; Batool, S.; Li, M.Z.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S.T. Biocompatible material-based flexible biosensors: From materials design to wearable/implantable devices and integrated sensing systems. Small 2023, 19, 2204559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rader, R.A.; Langer, E.S. Upstream single-use bioprocessing systems: Future market trends and growth assessment. Bioprocess Int. 2012, 10, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sud, D.; Mehta, G.; Mehta, K.; Linderman, J.; Takayama, S.; Mycek, M.-A. Optical imaging in microfluidic bioreactors enables oxygen monitoring for continuous cell culture. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006, 11, 050504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.S.; Lo, Y.L. Optical fiber dissolved oxygen sensor based on Pt(II) complex and core-shell silica nanoparticles incorporated with sol-gel matrix. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 161, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.S.; Chuang, C.Y. Optical fiber sensor for dual sensing of dissolved oxygen and Cu2+ ions based on PdTFPP/CdSe embedded in sol-gel matrix. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 209, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Hang, H.; Mohsin, A.; Chu, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, S. Application of 8-parallel micro-bioreactor system with non-invasive optical pH and DO biosensor in high-throughput screening of L-lactic acid producing strain. Bioresour. Bioprocess 2019, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, T.V.; Szita, N. Oxygen transfer characteristics of miniaturized bioreactor systems. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranirokh, M.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Francis, P.S.; Kanwar, J.R. Microfluidic devices for cell cultivation and proliferation. Biomicrofluidics 2013, 7, 051502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallocha, T.; Popp, O. Off-gas-based soft sensor for real-time monitoring of biomass and metabolism in Chinese hamster ovary cell continuous processes in single-use bioreactors. Processes 2021, 9, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Growth Characteristics | Typical Doubling Time | Cultivation Duration | Operational pH Range | Typical DO Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Microorganisms

|

| Minutes | Days | 2–12 | 20–60% |

Plant cells

|

| Days to weeks | Weeks to months | 5–6 | |

Mammalian cells

|

| Hours to days | Days to weeks | 6.8–7.4 | |

Insect cells

| Days | 6.1–6.5 | |||

Stem cells

|

| 6.8–7.4 | 0.7–20% |

| Monitoring Category | Typical Principles/Tools | Measurement Mode | Main Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Use/Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inline electrochemical probes | Glass pH electrodes; polarographic or galvanic DO probes mounted in the bioreactor headplate or side ports | Continuous, inline | Real-time signal for feedback control; mature technology; directly integrated with standard bioreactor controllers | Susceptible to drift, fouling, and environmental interference; single-point measurement; requires regular calibration and maintenance | Laboratory and industrial stirred-tank and airlift bioreactors from bench to production scale |

| Off-line and at-line analytical instruments | Benchtop pH meters; blood-gas analyzers; biochemical analyzers measuring pH, DO, and related variables | Discrete, sampling-based | High analytical accuracy under controlled conditions; can measure additional parameters; independent verification of inline probes. | Time delay between sampling and result; additional handling and contamination risk; labor-intensive and difficult to automate fully | Process development laboratories and GMP environments for method validation and quality control |

| Single-use and miniaturized electrochemical probes | Pre-mounted pH and DO sensors in disposable bioreactor bags; miniature probes integrated into small-scale or high-throughput systems | Continuous or quasi-continuous, inline or in situ | Compatible with disposable systems and parallel small-scale reactors; low working volume; easier deployment in high-throughput studies | Limited lifetime and sterilization options; calibration and standardization can be challenging; sensor performance may vary between batches | Single-use bioreactors, microbioreactors, and scale-down models for process development |

| Sensing Mechanism | Typical Fiber Structure/Configuration | Encoded Optical Quantity | Main Advantages | Typical Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity-based | Straight or tapered fiber; side-polished fiber; dye- or indicator-coated fiber tip or segment | Transmitted, reflected, or fluorescence intensity | Simple design and readout; low-cost hardware; easy integration and miniaturization | Sensitive to source and coupling fluctuations; bending and loss variations can affect the signal |

| Wavelength-encoded | Fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs); long-period fiber gratings (LPFGs); Fabry–Pérot cavities; multimode interferometers; plasmonic structures | Resonance or fringe wavelength | High resolution; robust against power drift; suitable for multiplexing and multi-parameter measurement | Requires a spectrometer or wavelength-resolved interrogation; more complex alignment and signal processing. |

| Phase-based | Mach–Zehnder, Michelson, or Sagnac interferometers; dual-core or multicore fibers | Phase shift or fringe position | Very high sensitivity to small refractive index or path-length changes; compatible with dynamic measurements | Interrogation and stabilization can be complex, sensitive to environmental perturbations (vibration, temperature) |

| Polarization-based | Polarization-maintaining fibers; birefringent fiber structures; fiber loop mirrors | Polarization state, birefringence, or beat length | Good sensitivity to stress, temperature, and anisotropic changes; useful for vector quantities | Requires polarization control and analysis; prone to random polarization fluctuations in non-PM fibers |

| Year | Authors | Sensing Mechanism Used | Important Results | Key Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Holobar et al. | Optical | Non-invasive pH measurement system. | pH range: 6–10. Accuracy: ±0.1. | [59] |

| 2002 | Kermis et al. | Dual Excitation Ratiometric Fluorescent | Non-invasive bioprocess monitoring. | pH range: 6–9. Accuracy: ±0.05. | [49] |

| 2003 | Kermis et al. | Optical | Rapid method development for robust pH sensors. | pH range: 6–9. | [50] |

| 2004 | Weidgans et al. | Fluorescent | pH sensors with minimized sensitivity to ionic strength variations. | pH range: 4.5–8. | [51] |

| 2011 | Shen et al. | Long-wavelength Fluorescent Hydrophilic Copolymer | Broad linear response range, enhancing pH monitoring accuracy. | pH range: 4.6–8. | [54] |

| 2016 | Janzen et al. | Fluorescent | Suitable for monitoring at low pH in challenging fermentation processes. | pH range: 3.9–7.2. | [55] |

| 2016 | Mousavi Shaegh et al. | Microfluidic Optical | Real-time monitoring for microfluidic bioreactors and organ-on-chip devices. | Measure continuously for up to 3 days. | [56] |

| 2016 | Demuth et al. | Novel optical Probes | Challenges and solutions for pH sensing across scales. | N/A | [52] |

| 2020 | Newton et al. | Fluorescent | Process-adapted calibration method for improved accuracy in complex fermentation. | pH range: 6–8. Accuracy: ±0.1. | [57] |

| 2022 | Udomsom et al. | Automatic optical Programmable | Real-time pH monitoring for tissue engineering applications. | pH range: 6.5–8. | [53] |

| Dye Family | Representative Immobilization Matrices | Typical Response Characteristics | Sensitivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (PtOEP, PtTFPP) | Fluorinated co-polymers; TEOS/C8TEOS; core–shell silica nanoparticles | Fast to moderate, depending on the matrix; nanoparticle systems facilitate improved O2 diffusion | I0/I ≈ 1.8 to >100 (0–40 mg/L) | [84,85] |

| Ru (Ph2phen)32+ | Fluoropolymer coatings; TEOS/MTEOS sol–gel matrices | Generally rapid response; suitable for low-to-mid oxygen levels | I0/I ≈ 3–6.6 (0–40 ppm) | [86,87] |

| Ru (dpp)32+ | TMOS/DiMe-DMOS; TMOS/C8TMOS; TEOS/MTEOS | Moderate switching kinetics (≈20–100 s depending on O2/N2 transition) | I0/I ≈ 1.3–16 (0–100% O2) | [88,91] |

| (Ru(bpy)32+) | Silica–Ni–P composites; TMOS/DiMe-DMOS sol–gels | Slower response (≈66–300 s) | I0/I ≈ 2.6–7.3 (0–20 × 10−6 M) | [89,90] |

| Year | Authors | Sensing Mechanism Used | Important Results | Key Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Kostov, Yordan, et al. | Dual emission probe and solid-state ratiometric fluorometer | Unique oxygen analyzer development | DO range: 0–90%. | [81] |

| 2002 | Tolosa, Leah, et al. | Noninvasive optical | Introduced a method for noninvasive DO measurement in shake flasks | DO range: 0–60%. | [82] |

| 2003 | Gupta, Atul, and Govind Rao | Noninvasive optical | Study on oxygen transfer in shake flasks | DO range: 0–60%. | [83] |

| 2004 | Gillanders et al. | PtOEP (fluorinated co-polymer) | Enabled efficient oxygen monitoring in continuous cell culture | DO range: 0–100%. Response time: 10 s. | [84] |

| 2005 | Gillanders et al. | Fluorescence quenching of Ru(II) complex immobilized in blended fluoropolymer film | Developed an optical fiber sensor | DO range: 0–30 mg/L. Sensitivity: 0.1 mg/L. | [85] |

| 2006 | Tao et al. | Class II xerogel-based optical O2 sensors (tunable sensitivity) | Evaluated the oxygen transfer performance of miniature bioreactor platforms | DO range: 0–100%. | [88] |

| 2015 | Chu et al. | PdTFPP/CdSe embedded in sol–gel | Optical fiber sensor development for dual sensing | DO range: 0–40 mg/L. | [90] |

| 2022 | Zhao et al. | Ratiometric optical fiber DO sensor (Ru(dpp)32+ + QDs) | Reported a ratiometric optical fiber DO sensor with linear Stern–Volmer behavior. | DO range: 0–18.25 mg/L. | [77] |

| 2024 | Lee et al. | Integrated multivariate sensor array in large-scale bioreactor | Large-scale smart bioreactor enabling multi-spatial sensing (pH, glucose, DO, temperature) for long-term culture monitoring. | DO range: 0–115 mg/L. Measure continuously for up to 30 days. | [94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cui, G.; Wu, R.; Cao, L.; Abedin, S.; Goel, K.; Yoon, S.; Wang, X. Optical Fiber pH and Dissolved Oxygen Sensors for Bioreactor Monitoring: A Review. Sensors 2026, 26, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010010

Cui G, Wu R, Cao L, Abedin S, Goel K, Yoon S, Wang X. Optical Fiber pH and Dissolved Oxygen Sensors for Bioreactor Monitoring: A Review. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Guoqiang, Rui Wu, Lidan Cao, Sabrina Abedin, Kanika Goel, Seongkyu Yoon, and Xingwei Wang. 2026. "Optical Fiber pH and Dissolved Oxygen Sensors for Bioreactor Monitoring: A Review" Sensors 26, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010010

APA StyleCui, G., Wu, R., Cao, L., Abedin, S., Goel, K., Yoon, S., & Wang, X. (2026). Optical Fiber pH and Dissolved Oxygen Sensors for Bioreactor Monitoring: A Review. Sensors, 26(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010010