Testing the Reliability of a Procedure Using Shear-Wave Elastography for Measuring Longus Colli Muscle Stiffness

Highlights

- Standardized SWE delivers reproducible LC stiffness in neck pain.

- Inter- and intra-examiner reliability was good to excellent.

- Averaging two measurements improved ICCs and decreased SEM and MDC.

- Further studies can follow this protocol to characterize LC stiffness.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Examiners

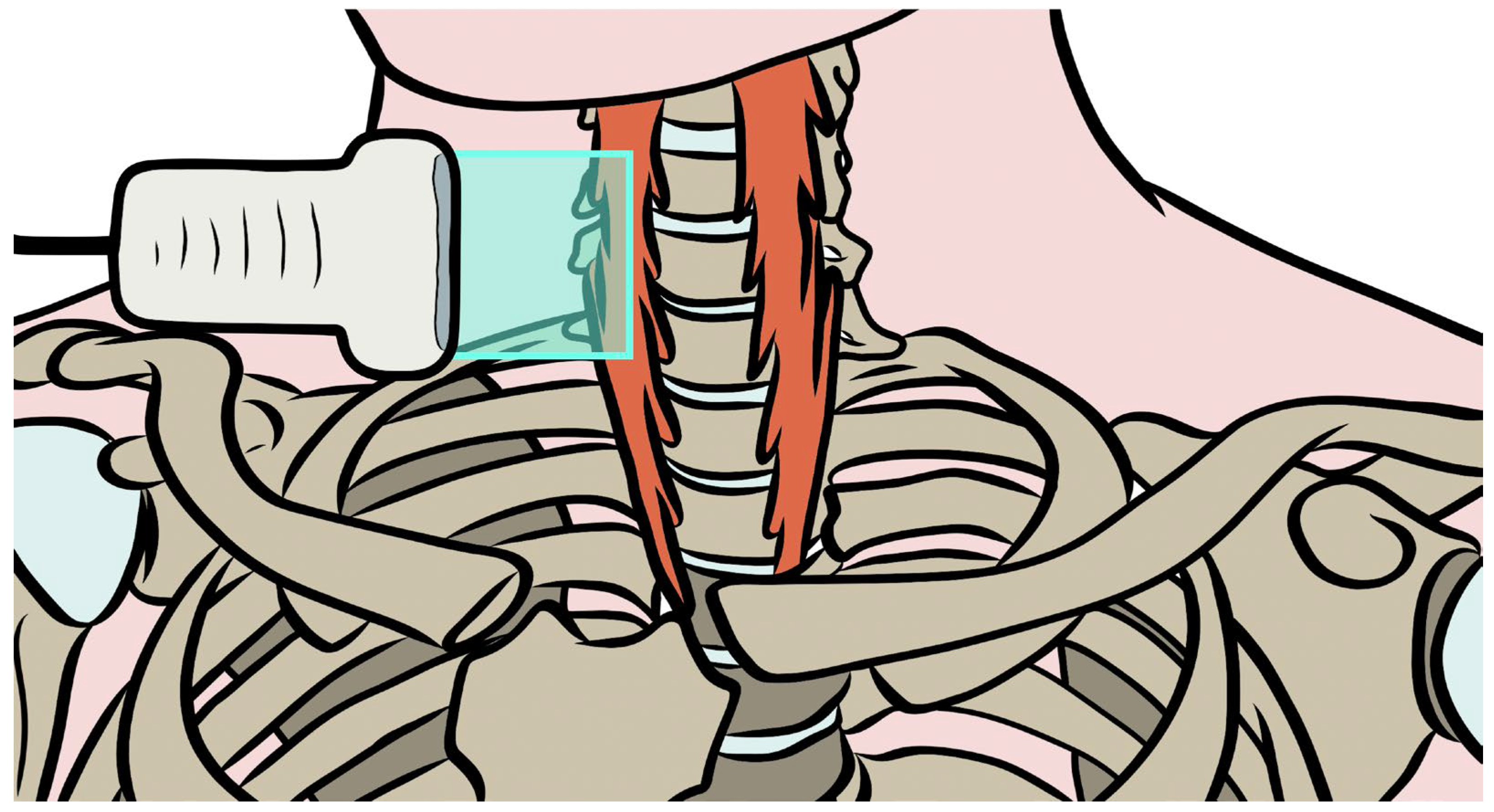

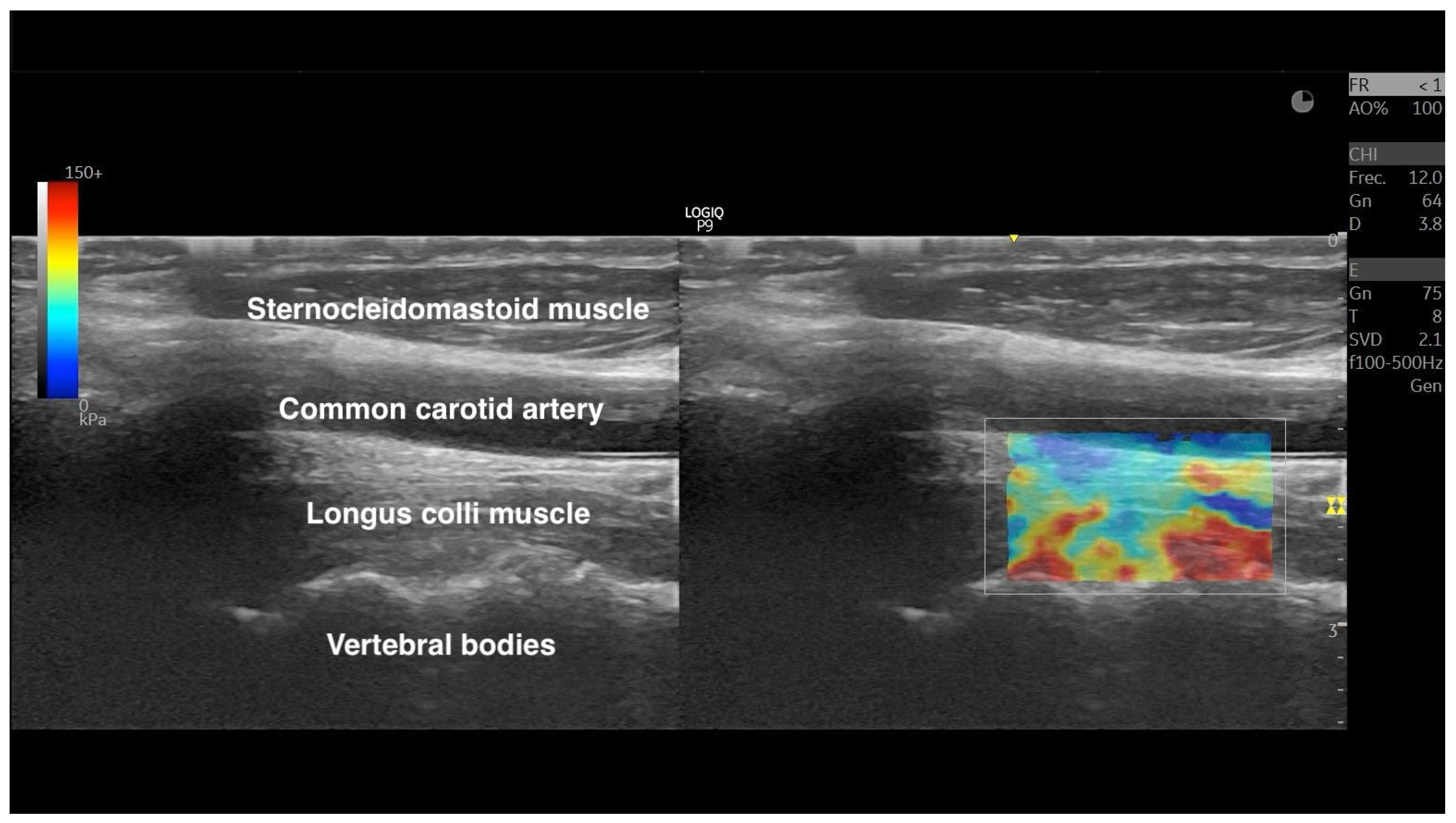

2.4. Shear-Wave Elastography Exam

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakkum, B.W.; Cramer, G.D. Muscles That Influence the Spine. In Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and ANS; Mosby: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2014; pp. 98–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Moon, S.H.; Kim, T.H.; Oh, J.K.; Kim, H.J.; Park, K.T.; Daniel Riew, K. Surgical Anatomy of the Longus Colli Muscle and Uncinate Process in the Cervical Spine. Yonsei Med. J. 2016, 57, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Woodley, S.J.; Cornwall, J. Fibre Type Composition of Female Longus Capitis and Longus Colli Muscles. Anat. Sci. Int. 2016, 91, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.; Albert, M.; Nicholson, H. Do Longus Capitis and Colli Really Stabilise the Cervical Spine? A Study of Their Fascicular Anatomy and Peak Force Capabilities. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2017, 32, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jull, G.; Kristjansson, E.; Dall’Alba, P. Impairment in the Cervical Flexors: A Comparison of Whiplash and Insidious Onset Neck Pain Patients. Man. Ther. 2004, 9, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jull, G.A.; O’Leary, S.P.; Falla, D.L. Clinical Assessment of the Deep Cervical Flexor Muscles: The Craniocervical Flexion Test. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2008, 31, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-M.; Pan, F.-M.; Yong, Z.-Y.; Ba, Z.-Y.; Wang, S.-J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, W.-D.; Wu, D.-S. Does the Longus Colli Have an Effect on Cervical Vertigo?: A Retrospective Study of 116 Patients. Medicine 2017, 96, e6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, J.Á.D.B.; de la Flor, Á.G.; Balmaseda, D.D.; Vera, D.M.; Sierra, A.S.; de Sevilla, G.G.P. Pain Sensitization and Atrophy of Deep Cervical Muscles in Patients with Chronic Tension-Type Headache. Rev. Assoc. Medica Bras. (1992) 2023, 69, e20230841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, D.; Moura Filho, A.G.; Costa Neto, J.J.S.; Siqueira, G.R.; de Oliveira, D.A. Analysis of Dimensions, Activation and Median Frequency of Cervical Flexor Muscles in Young Women with Migraine or Tension-Type Headache. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2015, 19, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnie, B.; Dirks, R.; Schouten, M.; Parlevliet, T.; Cambier, D.; Danneels, L. Functional Reorganization of Cervical Flexor Activity Because of Induced Muscle Pain Evaluated by Muscle Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Man. Ther. 2011, 16, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falla, D.; O’Leary, S.; Farina, D.; Jull, G. The Change in Deep Cervical Flexor Activity after Training Is Associated with the Degree of Pain Reduction in Patients with Chronic Neck Pain. Clin. J. Pain. 2012, 28, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falla, D.; Rainoldi, A.; Merletti, R.; Jull, G. Myoelectric Manifestations of Sternocleidomastoid and Anterior Scalene Muscle Fatigue in Chronic Neck Pain Patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukturan, B.; Guclu-Gunduz, A.; Buyukturan, O.; Dadali, Y.; Bilgin, S.; Kurt, E.E. Cervical Stability Training with and without Core Stability Training for Patients with Cervical Disc Herniation: A Randomized, Single-Blind Study. Eur. J. Pain 2017, 21, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanshir, K.; Ghafouri-Rouzbehani, P.; Zohrehvand, A.; Naeimi, A.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Nikbakht, H.-A.; Mousavi-Khatir, S.R.; Valera-Calero, J.A. Cervical Multifidus and Longus Colli Ultrasound Differences among Patients with Cervical Disc Bulging, Protrusion and Extrusion and Asymptomatic Controls: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siag, K.; Mazzawi, S.; Paker, M.; Biener, R.; Ghanayim, R.; Lumelsky, D. Acute Longus Colli Tendinitis and Otolaryngology. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Xiang, H.; Wu, X.; Chen, B.; Guo, Z. The Influence of Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion Surgery on Cervical Muscles and the Correlation between Related Muscle Changes and Surgical Efficacy. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri Arimi, S.; Ghamkhar, L.; Kahlaee, A.H. The Relevance of Proprioception to Chronic Neck Pain: A Correlational Analysis of Flexor Muscle Size and Endurance, Clinical Neck Pain Characteristics, and Proprioception. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 2077–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiringakis, G.; Dimitriadis, Z.; Triantafylloy, E.; McLean, S. Motor Control Training of Deep Neck Flexors with Pressure Biofeedback Improves Pain and Disability in Patients with Neck Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2020, 50, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarotto, A.; Clijsen, R.; Fernandez-De-Las-Penas, C.; Barbero, M. Prevalence of Myofascial Trigger Points in Spinal Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.C.; Belgrave, A.; Naden, A.; Fang, H.; Matthews, P.; Parshottam, S. The Prevalence of Myofascial Trigger Points in Neck and Shoulder-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review of the Literature. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, J.P.; Jaiswal, K.S.; Kumbhare, D. Myofascial Pain Syndrome: An Update on Clinical Characteristics, Etiopathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Muscle Nerve 2025, 71, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Dommerholt, J. International Consensus on Diagnostic Criteria and Clinical Considerations of Myofascial Trigger Points: A Delphi Study. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintner, J.L.; Bove, G.M.; Cohen, M.L. A Critical Evaluation of the Trigger Point Phenomenon. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenhaver, S.L.; Hebert, J.J.; Kawchuk, G.N.; Childs, J.D.; Teyhen, D.S.; Croy, T.; Fritz, J.M. Criterion Validity of Manual Assessment of Spinal Stiffness. Man. Ther. 2014, 19, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seffinger, M.A.; Najm, W.I.; Mishra, S.I.; Adams, A.; Dickerson, V.M.; Murphy, L.S.; Reinsch, S. Reliability of Spinal Palpation for Diagnosis of Back and Neck Pain: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Spine 2004, 29, E413–E425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monclús-Díez, G.; Díaz-Arribas, M.J.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Kosson, D.; Kołacz, M.; Kobylarz, M.D.; Sánchez-Jorge, S.; Valera-Calero, J.A. Prevalence of Myofascial Trigger Points in Patients with Radiating and Non-Radiating Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, A.V.; Yavuz, U.Ş.; Petzke, F.; Nordez, A.; Falla, D. Neck Muscle Stiffness Measured With Shear Wave Elastography in Women With Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cè, M.; D’Amico, N.C.; Danesini, G.M.; Foschini, C.; Oliva, G.; Martinenghi, C.; Cellina, M.; D’Amico, N.C.; Danesini, G.M.; Foschini, C.; et al. Ultrasound Elastography: Basic Principles and Examples of Clinical Applications with Artificial Intelligence—A Review. BioMedInformatics 2023, 3, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Grover, S.B. Physical Principles of Elastography: A Primer for Radiologists. Indographics 2022, 01, 027–040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, R.M.S.; Liau, J.; Kaffas, A.E.; Chammas, M.C.; Willmann, J.K. Ultrasound Elastography: Review of Techniques and Clinical Applications. Theranostics 2017, 7, 1303–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, A.; Grajo, J.R.; Dhyani, M.; Anthony, B.W.; Samir, A.E. Principles of Ultrasound Elastography. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valera-Calero, J.A.; Varol, U.; López-Redondo, M.; Díaz-Arribas, M.J.; Navarro-Santana, M.J.; Plaza-Manzano, G. Association among Clinical Severity Indicators, Psychological Health Status and Elastic Properties of Neck Muscles in Patients with Chronic Mechanical Neck Pain. Eur. Spine J. 2025, 13, 1238–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottner, J.; Audigé, L.; Brorson, S.; Donner, A.; Gajewski, B.J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Roberts, C.; Shoukri, M.; Streiner, D.L. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) Were Proposed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltychev, M.; Pylkäs, K.; Karklins, A.; Juhola, J. Psychometric Properties of Neck Disability Index—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 5415–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Haugen, D.F.; Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.W.; Loge, J.H.; Fainsinger, R.; Aass, N.; Kaasa, S. Studies Comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for Assessment of Pain Intensity in Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S.D.; Eliasziw, M.; Donner, A. Sample Size and Optimal Designs for Reliability Studies. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanshir, K.; Rezasoltani, A.; Mohseni-Bandpei, M.A.; Amiri, M.; Ortega-Santiago, R.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C. Ultrasound Assessment of Bilateral Longus Colli Muscles in Subjects with Chronic Bilateral Neck Pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 90, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øverås, C.K.; Myhrvold, B.L.; Røsok, G.; Magnesen, E. Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging for Thickness Measurement of Four Principal Muscles of the Cervical Spine—A Reliability and Agreement Study. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2017, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fávero, L.P.; Belfiore, P. Hypotheses Tests. In Data Science for Business and Decision Making; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 199–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taljanovic, M.S.; Gimber, L.H.; Becker, G.W.; Latt, L.D.; Klauser, A.S.; Melville, D.M.; Gao, L.; Witte, R.S. Shear-Wave Elastography: Basic Physics and Musculoskeletal Applications. Radiographics 2017, 37, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, B.-L.; Ha, S.-M.; Jeon, I.-C.; Hong, K.-H. Reliability of Ultrasonography Measurement for the Longus Colli According to Inward Probe Pressure. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 3579–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Schilaty, N.D.; Krause, D.A.; Crowley, E.M.; Hewett, T.E. Sex Differences in Ultrasound-Based Muscle Size and Mechanical Properties of the Cervical-Flexor and -Extensor Muscles. J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni, F.; Rahmani, N.; Mohseni Bandpei, M.A.; Abdollahi, I. Reliability of Ultrasonography to Measure Cervical Multifidus, Semispinalis Cervicis and Longus Colli Muscles Dimensions in Patients with Unilateral Cervical Disc Herniation: An Observational Cross-Sectional Test-Retest Study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2024, 37, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanpied, P.R.; Gross, A.R.; Elliott, J.M.; Devaney, L.L.; Clewley, D.; Walton, D.M.; Sparks, C.; Robertson, E.K. Neck Pain: Revision 2017. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017, 47, A1–A83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Males (n = 6) | Females (n = 13) | Gender Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | 55.7 ± 6.5 | 48.8 ± 8.1 | 6.8 (−1.2; 14.8) p = 0.090 |

| Weight, kg | 72.2 ± 10.8 | 63.7 ± 7.2 | 8.5 (−0.3; 17.3) p = 0.058 |

| Height, m | 1.65 ± 0.07 | 1.64 ± 0.06 | 0.01 (−0.05; 0.07) p = 0.771 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 ± 3.6 | 23.8 ± 4.1 | 2.6 (−1.51; 6.72) p = 0.199 |

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Pain duration, months | 16.3 ± 10.1 | 30.0 ± 11.7 | 13.6 (−1.9; 25.4) p = 0.025 |

| Neck Disability Index, 0–100 | 29.3 ± 12.8 | 36.4 ± 10.8 | 7.1 (−4.9; 19.0) p = 0.229 |

| Numeric Pain Rating Scale, 0–10 | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 7.0 ± 0.91 | 0.8 (−0.3; 1.9) p = 0.137 |

| Gender | Side | Shear-Wave Speed (m/s) | Shear Modulus (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive shear-wave elastography scores * | |||

| Males | Mean | 5.97 ± 0.93 | 108.3 ± 30.3 |

| Left (n = 6) | 5.83 ± 1.04 | 102.3 ± 34.2 | |

| Right (n = 6) | 6.10 ± 0.88 | 114.4 ± 27.7 | |

| Females | Mean | 6.24 ± 0.68 | 115.8 ± 24.7 |

| Left (n = 13) | 6.16 ± 0.79 | 113.7 ± 28.4 | |

| Right (n = 13) | 6.31 ± 0.57 | 117 9 ± 21.2 | |

| Differences | |||

| Gender | F | 0.986 | 0.624 |

| p Value | 0.328 | 0.435 | |

| 0.028 | 0.018 | ||

| Side | F | 0.637 | 0.743 |

| p Value | 0.430 | 0.395 | |

| 0.018 | 0.021 | ||

| Gender × Side | F | 0.176 | 0.051 |

| p Value | 0.677 | 0.823 | |

| 0.005 | 0.001 | ||

| Reliability Estimates | Shear-Wave Speed (m/s) | Shear Modulus (kPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novice Examiner (n = 38 Images) | Experienced Examiner (n = 38 Images) | Novice Examiner (n = 38 Images) | Experienced Examiner (n = 38 Images) | |

| Single Measurements | ||||

| Mean | 6.24 ± 0.88 | 6.06 ± 0.86 | 117.2 ± 29.0 | 109.7 ± 30.0 |

| Difference | 0.15 (−0.24; 0.55) p = 0.442 | 6.4 (−7.1; 19.8) p = 0.349 | ||

| Absolute Error | 0.39 ± 0.58 | 12.5 ± 18.7 | ||

| ICC3,2, 0–1 | 0.818 (0.649; 0.905) | 0.849 (0.710; 0.922) | ||

| SEM | 0.37 | 11.5 | ||

| MDC | 1.03 | 31.8 | ||

| Mean Average of 2 Measurements | ||||

| Mean | 6.24 ± 0.80 | 6.07 ± 0.83 | 116.9 ± 26.6 | 109.9 ± 29.1 |

| Difference | 0.17 (−0.20; 0.54) p = 0.362 | 7.0 (−5.8; 19.7) p = 0.280 | ||

| Absolute Error | 0.32 ± 0.49 | 10.8 ± 16.0 | ||

| ICC3,2, 0–1 | 0.866 (0.742; 0.930) | 0.883 (0.775; 0.939) | ||

| SEM | 0.30 | 9.5 | ||

| MDC | 0.83 | 26.4 | ||

| Reliability Estimates | Novice Examiner | Experienced Examiner | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shear-Wave Speed (m/s) | Shear Modulus (kPa) | Shear-Wave Speed (m/s) | Shear Modulus (kPa) | |||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | |

| Mean | 6.24 ± 0.88 | 6.23 ± 0.78 | 117.2 ± 29.0 | 116.6 ± 27.1 | 6.06 ± 0.86 | 6.07 ± 0.82 | 109.7 ± 30.0 | 110.2 ± 29.0 |

| Difference | 0.00 (−0.4; 0.4) p = 0.987 | 0.7 (−12.1; 13.5) p = 0.919 | 0.01 (−0.36; 0.40) p = 0.928 | 0.4 (−13.0; 13.9) p = 0.951 | ||||

| Absolute Error | 0.28 ± 0.40 | 10.0 ± 14.4 | 0.20 ± 0.16 | 7.5 ± 5.8 | ||||

| ICC3,1, 0–1 | 0.906 (0.819; 0.951) | 0.891 (0.790; 0.943) | 0.974 (0.950; 0.987) | 0.973 (0.949; 0.986) | ||||

| SEM | 0.26 | 9.3 | 0.14 | 4.8 | ||||

| MDC | 0.71 | 25.7 | 0.38 | 13.4 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Izquierdo-García, J.; Valera-Calero, J.A.; Navarro-Santana, M.J.; López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I.; Rabanal-Rodríguez, G.; Sanz-Ayán, M.P.; Castillo-Martín, J.I.; Plaza-Manzano, G. Testing the Reliability of a Procedure Using Shear-Wave Elastography for Measuring Longus Colli Muscle Stiffness. Sensors 2026, 26, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010065

Izquierdo-García J, Valera-Calero JA, Navarro-Santana MJ, López-de-Uralde-Villanueva I, Rabanal-Rodríguez G, Sanz-Ayán MP, Castillo-Martín JI, Plaza-Manzano G. Testing the Reliability of a Procedure Using Shear-Wave Elastography for Measuring Longus Colli Muscle Stiffness. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzquierdo-García, Juan, Juan Antonio Valera-Calero, Marcos José Navarro-Santana, Ibai López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, Gabriel Rabanal-Rodríguez, María Paz Sanz-Ayán, Juan Ignacio Castillo-Martín, and Gustavo Plaza-Manzano. 2026. "Testing the Reliability of a Procedure Using Shear-Wave Elastography for Measuring Longus Colli Muscle Stiffness" Sensors 26, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010065

APA StyleIzquierdo-García, J., Valera-Calero, J. A., Navarro-Santana, M. J., López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I., Rabanal-Rodríguez, G., Sanz-Ayán, M. P., Castillo-Martín, J. I., & Plaza-Manzano, G. (2026). Testing the Reliability of a Procedure Using Shear-Wave Elastography for Measuring Longus Colli Muscle Stiffness. Sensors, 26(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010065