GECO: A Real-Time Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller for Advanced IoT Home System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Development of GECO, a markerless gesture controller for IoT smart homes integrating MediaPipe-based hand tracking with local device control.

- Design of a two-level interaction model in which the right hand enables on-screen navigation and the left hand controls device states and analog adjustments.

- Implementation of continuous gesture-based modulation, such as light dimming using thumb–index angles, enabling more natural device interaction.

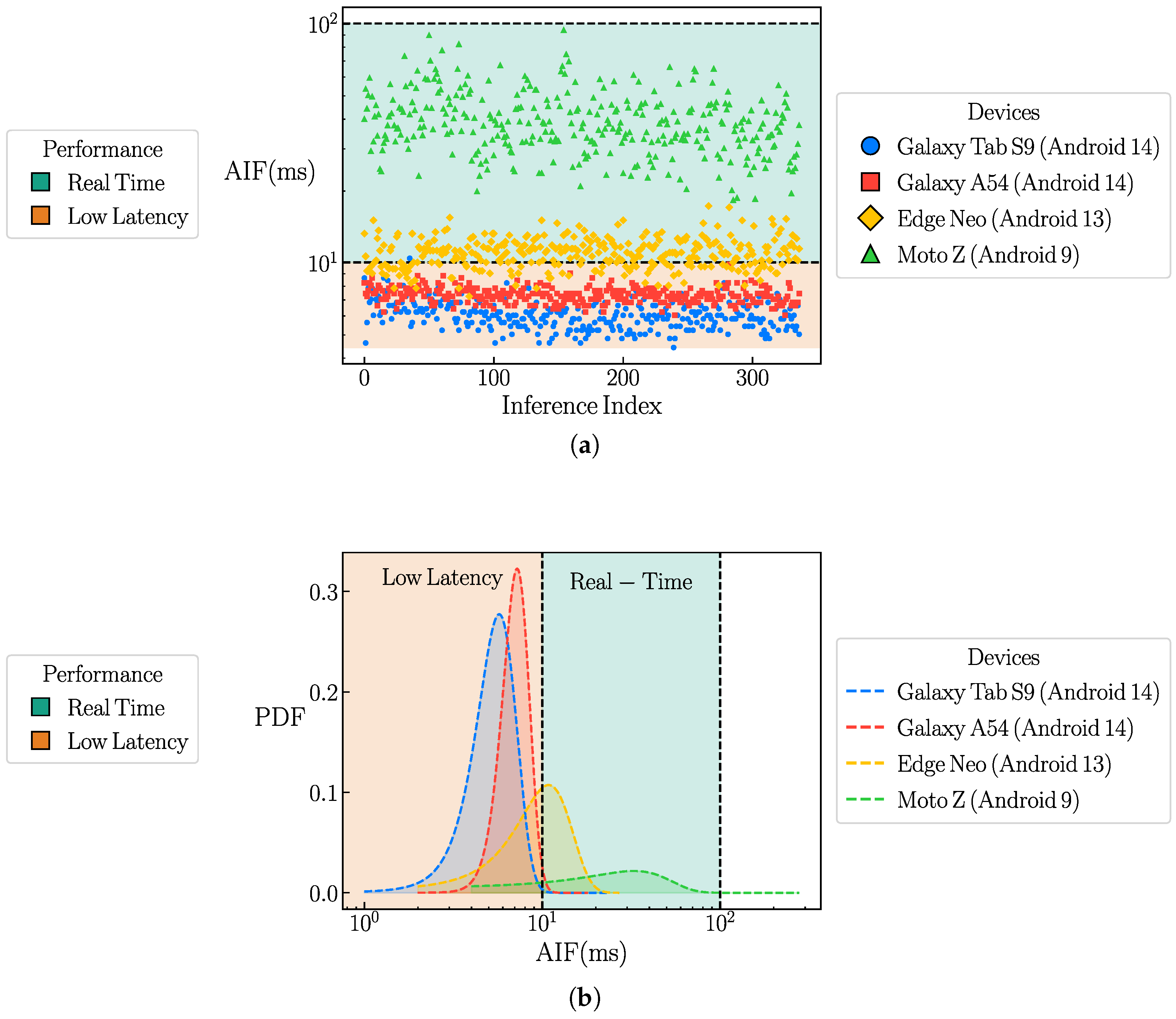

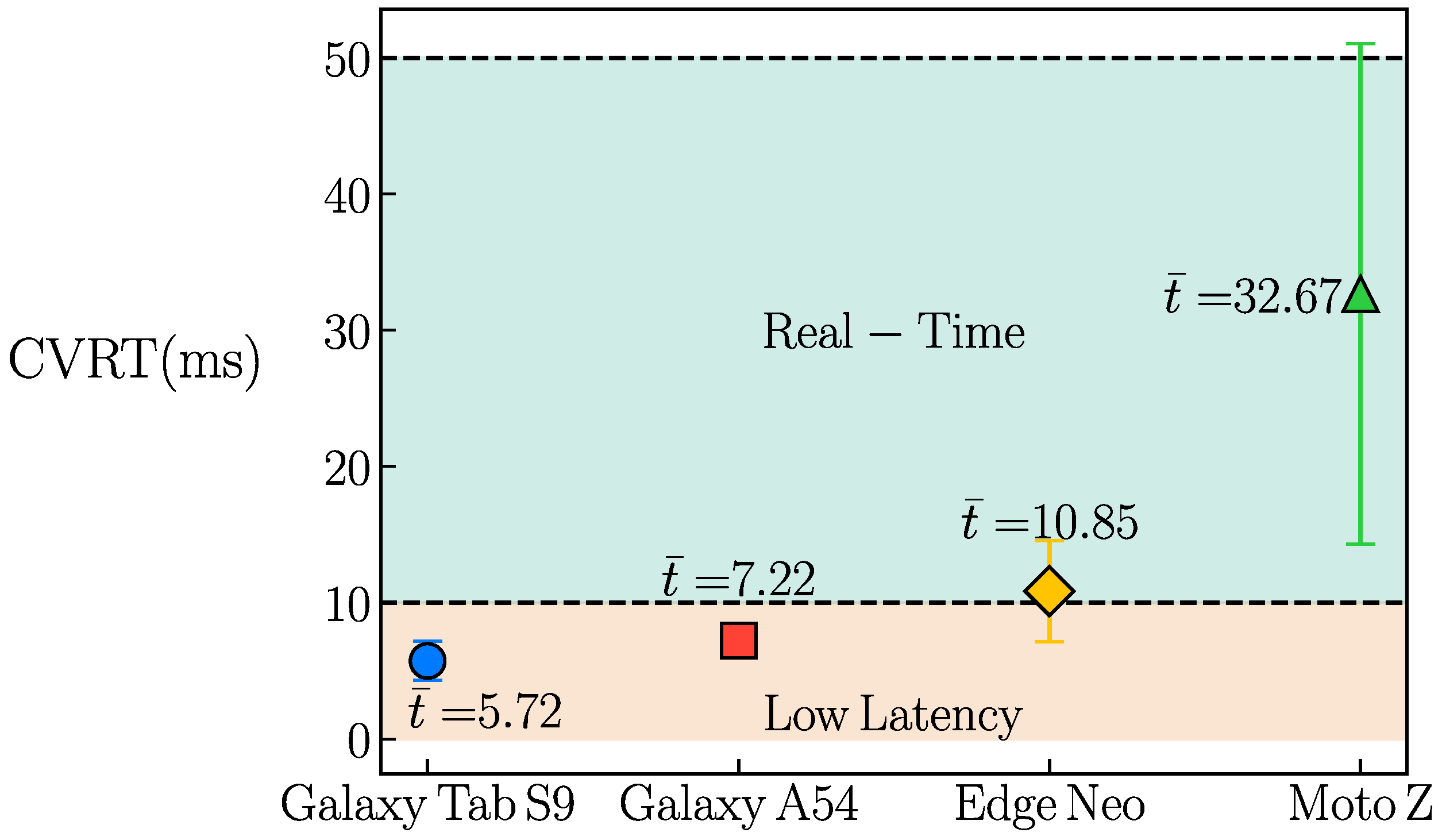

- Performance validation across multiple devices demonstrating real-time responsiveness and consistent user experience, supported by quantitative latency analysis (<50 ms) and empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) modeling.

2. Related Works

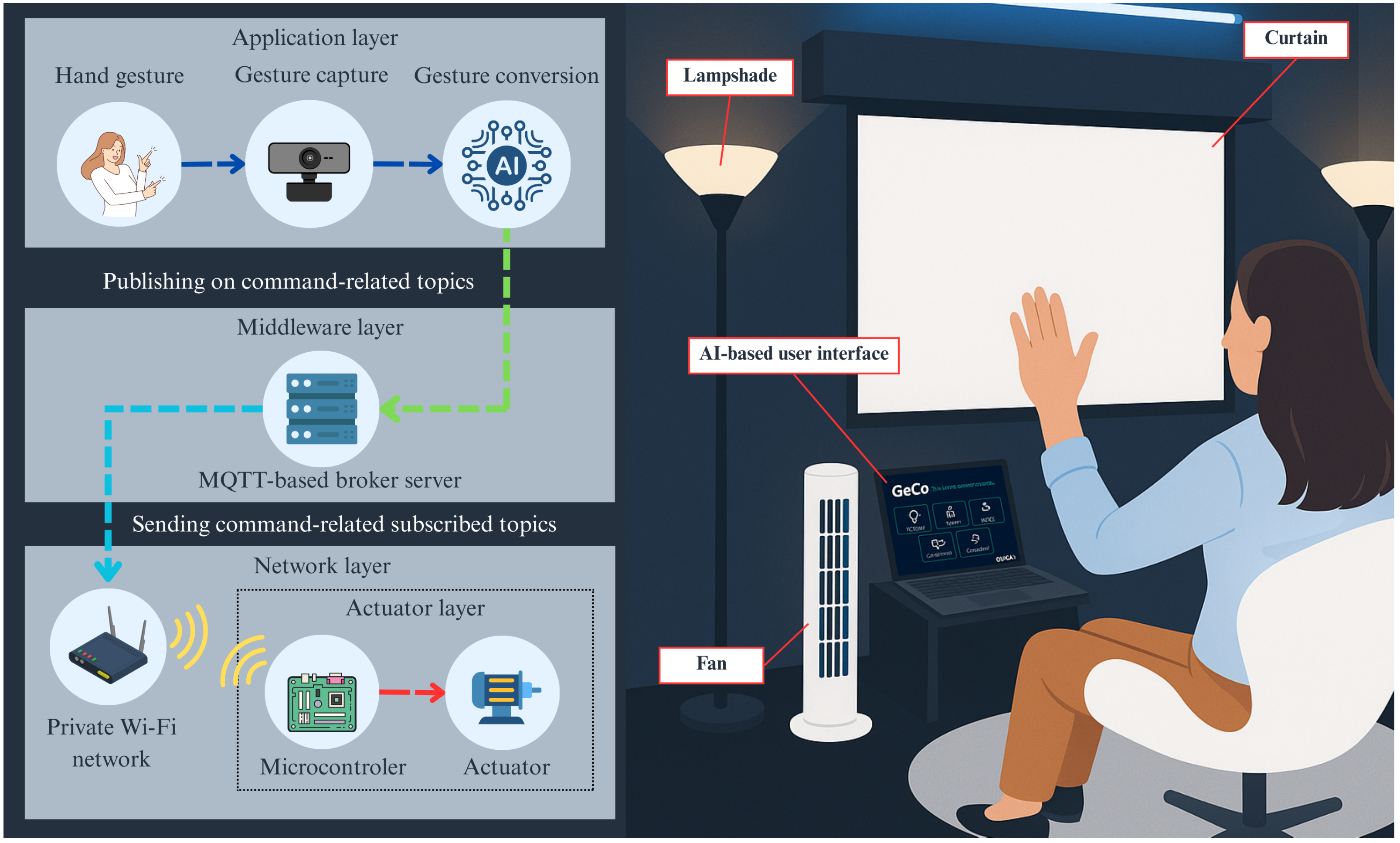

3. Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller IoT Platform

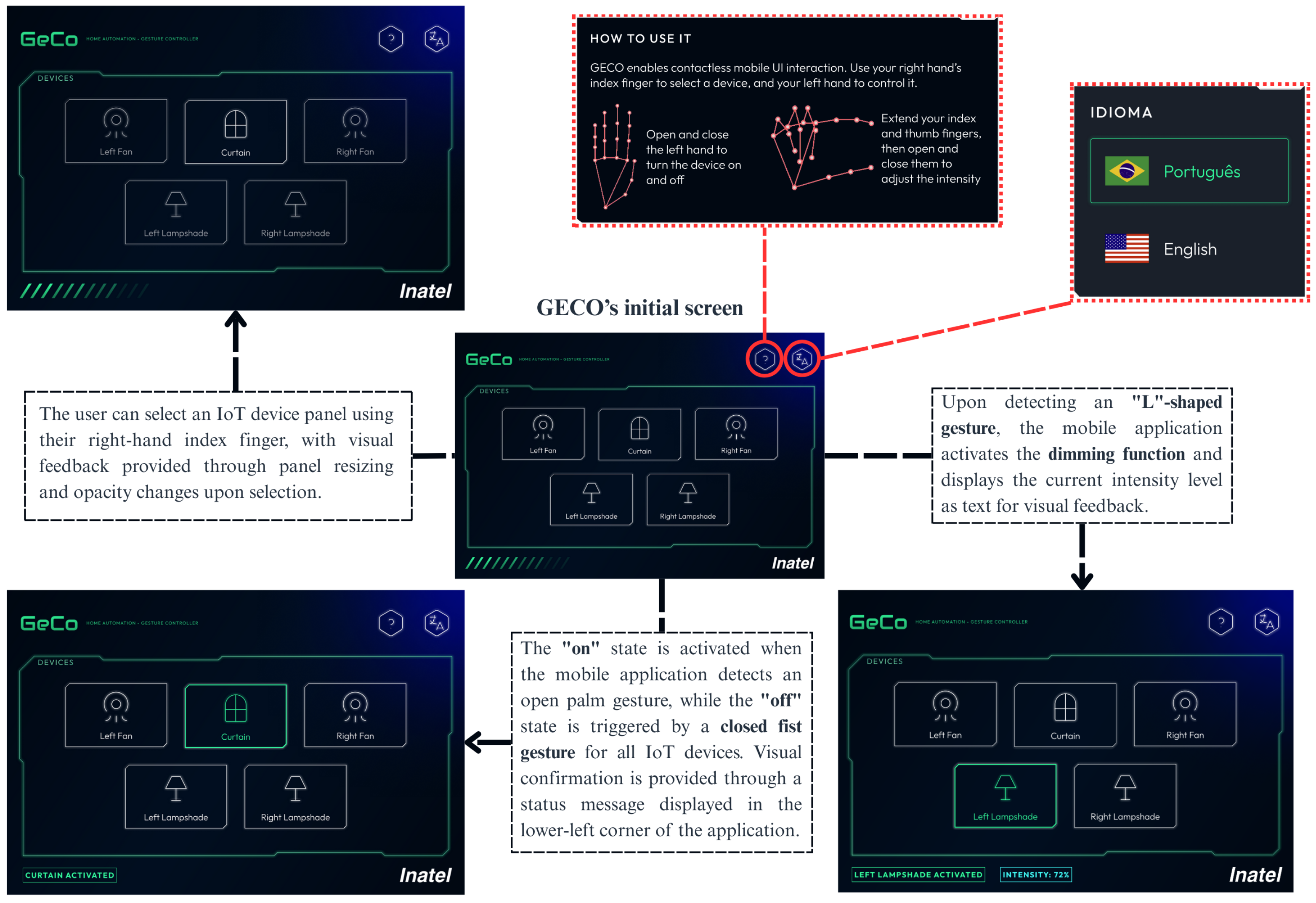

4. Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller Implementation

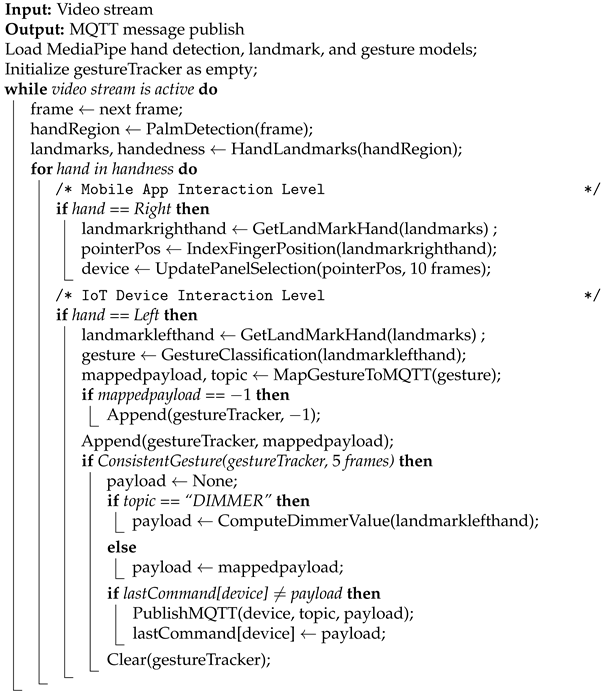

| Algorithm 1: Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller. |

|

5. Technical and User Experience Discussion

5.1. Technical Evaluation

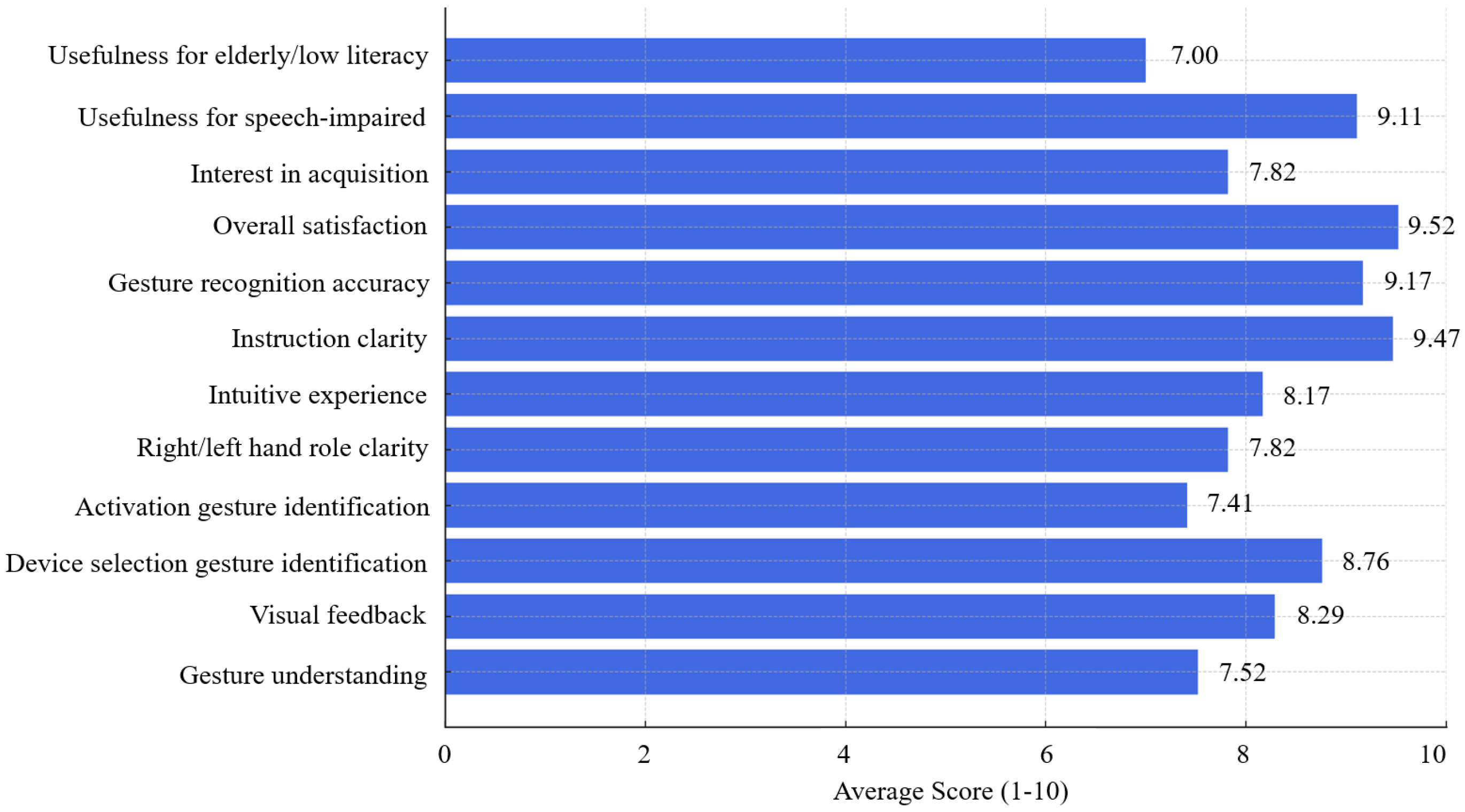

5.2. User Experience Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AAL | Ambient Assisted Living |

| AIF | Average Inference Time |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ASL | American Sign Language |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CVRT | Computer Vision Response Time |

| DC | Direct Current |

| ECDF | Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function |

| FrFT | Fractional Fourier Transform |

| GECO | Gesture-Controlled Environment Controller |

| H-bridge | Half Bridge |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ITU-T | International Telecommunication Union—Telecommunication Standardization Sector |

| LPWAN | Low-Power Wide-Area Network |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| NLU | Natural Language Understanding |

| Probability Density Function | |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RVM | Relevance Vector Machine |

| SDK | Software Development Kit |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| UWB | Ultra-Wideband |

| UI/UX | User Interface/User Experience |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless Fidelity |

| 5G | Fifth Generation |

References

- Al-Fuqaha, A.; Guizani, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Aledhari, M.; Ayyash, M. Internet of Things: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. 2015, 17, 2347–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J.G.A.; da Conceição, A.A.; Ambrósio, L.P.; Fernandes, F.; Ramborger, E.H.T.; Aquino, G.P.; Boas, E.C.V. Smart Lab: An IoT-centric Approach for Indoor Environment Automation. J. Commun. Inf. Syst. 2024, 39, 82. [Google Scholar]

- da Conceic’ão, A.A.; Ambrosio, L.P.; Leme, T.R.; Rosa, A.C.; Ramborger, F.F.; Aquino, G.P.; Boas, E.C.V. Internet of things environment automation: A smart lab practical approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Information Technology and Education (ICIT&E), Malang, Indonesia, 22 January 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chettri, L.; Bera, R. A comprehensive survey on Internet of Things (IoT) toward 5G wireless systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoukar, A.; Raza, S.; Poole, A.; Güneş, M.; Dezfouli, B. Low-power wireless for the internet of things: Standards and applications. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 67893–67926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H.S.; Huang, H.; Viswanathan, H. Wide-area wireless communication challenges for the Internet of Things. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liang, P.; Fu, L.; Cui, G.; Huang, F.; Teng, F.; Bangash, Y.A. Using 5G in smart cities: A systematic mapping study. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2022, 14, 200065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, P.; Nesi, P.; Pantaleo, G. IoT-enabled smart cities: A review of concepts, frameworks and key technologies. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, A.H.; Jiao, P.; Buttlar, W.G.; Lajnef, N. Internet of Things-Enabled Smart Cities: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends. Measurement 2018, 129, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, S.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Siano, P.; Loia, V.; Tommasetti, A.; Catalão, J.P. A review of smart cities based on the internet of things concept. Energies 2017, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Y.; Ahmad, F.; Yaqoob, I.; Adnane, A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, S. Internet-of-things-based smart cities: Recent advances and challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Cooper, D.; David, B. A literature survey on smart cities. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2015, 58, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracias, J.S.; Parnell, G.S.; Specking, E.; Pohl, E.A.; Buchanan, R. Smart cities—A structured literature review. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1719–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Dhunny, Z.A. On big data, artificial intelligence and smart cities. Cities 2019, 89, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.U.; Yaqoob, I.; Tran, N.H.; Kazmi, S.A.; Dang, T.N.; Hong, C.S. Edge-computing-enabled smart cities: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 10200–10232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, S.S.; Sofi, S.A. IoT-Fog architectures in smart city applications: A survey. China Commun. 2021, 18, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, M.H.F.; Teixeira, E.H.; Cruz., M.R.; Aquino, G.P.; Vilas Boas, E.C. Vehicle and Plate Detection for Intelligent Transport Systems: Performance Evaluation of Models YOLOv5 and YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computing (ICOCO), Langkawi, Malaysia, 9–12 October 2023; pp. 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, Y. IoT Home Automation—Smart homes and Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Academic Exchange Conference on Science and Technology Innovation (IAECST), Guangzhou, China, 10–12 December 2021; pp. 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusaed, A.; Yitmen, I.; Almssad, A. Enhancing smart home design with AI models: A case study of living spaces implementation review. Energies 2023, 16, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T. Review on the application of artificial intelligence in smart homes. Smart Cities 2019, 2, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhalik, W.A. AI-Driven Smart Homes: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 2023, 8, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. Integration of Cross-Computer Science and Architectural Design for the Elderly: AI for Smart Home. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Inventive Communication and Computational Technologies, Coimbatore, India, 14–15 June 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 863–873. [Google Scholar]

- Azzedine, D.E. AI-Powered Conversational Home Assistant for Elderly Care. Master’s Thesis, University of guelma, Guelma, Algeria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Periša, M.; Teskera, P.; Cvitić, I.; Grgurević, I. Empowering People with Disabilities in Smart Homes Using Predictive Informing. Sensors 2025, 25, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Sánchez, O.B.; López-Neri, E.; Cedillo-Elias, E.J.; Aceves-Martínez, E.; Larios, V.M. Validation of IoT Infrastructure for the Construction of Smart Cities Solutions on Living Lab Platform. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negreiros, I.; Francisco, A.C.C.; Fengler, F.H.; Faria, G.; Pinto, L.G.P.; Tolotto, M.; Rogoschewski, R.B.; Romano, R.R.; Netto, R.S. Smart Campus® as a Living Lab on Sustainability Indicators Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 28 September–1 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadar, M. Smart Learning Environment for the Development of Smart City Applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 8th International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), Sofia, Bulgaria, 4–6 September 2016; pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, N.J.; Kanza, S.; Cruickshank, D.; Brocklesby, W.S.; Frey, J.G. Talk2Lab: The Smart Lab of the Future. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 8631–8640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, C.S.; Purushothaman, R.; Anusha, K.; Sakthi, S. Smart Gesture Controlled Systems Using IoT. In AI-Based Digital Health Communication for Securing Assistive Systems; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Agoes, A.S.; Indriani. Applying hand gesture recognition for user guide application using MediaPipe. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Seminar of Science and Applied Technology (ISSAT 2021), Online, 12 October 2021; Atlantis Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Altayeb, M. Hand gestures replicating robot arm based on mediapipe. Indones J. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2023, 11, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, W.; Santos, L.; Melo, G.; Oliveira, A.; Nascimento, P.; Carvalho, G.; Neves, T.; Martins, A.; Araújo, Í. A Framework for Real-Time Gestural Recognition and Augmented Reality for Industrial Applications. Sensors 2024, 24, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.R.; Ali, M.L.; Sadi, M.S. Developing a real-time hand-gesture recognition technique for wheelchair control. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Ngo, B.V.; Nguyen, T.N. Vision-Based Hand Gesture Recognition Using a YOLOv8n Model for the Navigation of a Smart Wheelchair. Electronics 2025, 14, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandolikar, N.; Bondarde, A.; Bodade, N.; Bornar, V.; Borkar, D.; Borbande, S.; Borkar, P. Hand Gesture Controlled Wheelchair. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Quantum Computation-Based Sensor Application (ICAIQSA), Chennai, India, 8–9 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Zhao, Y. Advanced Gesture Recognition Method Based on Fractional Fourier Transform and Relevance Vector Machine for Smart Home Appliances. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2025, 36, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanwar, A.; Alzantot, M.; Ho, B.J.; Martin, P.; Srivastava, M. Selecon: Scalable iot device selection and control using hand gestures. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 18–21 April 2017; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotou, C.; Faliagka, E.; Antonopoulos, C.P.; Voros, N. Multidisciplinary ML Techniques on Gesture Recognition for People with Disabilities in a Smart Home Environment. AI 2025, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameliasari, M.; Putrada, A.G.; Pahlevi, R.R. An evaluation of svm in hand gesture detection using imu-based smartwatches for smart lighting control. J. Infotel 2021, 13, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdullah, B.I.; Ansar, H.; Mudawi, N.A.; Alazeb, A.; Alshahrani, A.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Jalal, A. Smart home automation-based hand gesture recognition using feature fusion and recurrent neural network. Sensors 2023, 23, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, B.; Mushtaq, B.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ahmed, A. IoT-based Smart Home Automation Using Gesture Control and Machine Learning for Individuals with Auditory Challenges. ICCK Trans. Internet Things 2024, 2, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.Y.; Lin, Y.N.; Wang, S.K.; Shen, V.R.; Tung, Y.C.; Shen, F.H.; Huang, C.H. Smart control of home appliances using hand gesture recognition in an IoT-enabled system. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 2176607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, D.L.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, T.S. Hand gesture recognition and interface via a depth imaging sensor for smart home appliances. Energy Procedia 2014, 62, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemuda, F.; Lin, F.J. Gesture-based control in a smart home environment. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), Exeter, UK, 21–23 June 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 784–791. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Dong, E.; Xu, M.; Lv, H.; Wu, F. Commodity Wi-Fi-Based Wireless Sensing Advancements over the Past Five Years. Sensors 2024, 24, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Zhao, P.; Yan, H.; Sun, X.; Dong, M. Target-Oriented WiFi Sensing for Respiratory Healthcare: From Indiscriminate Perception to In-Area Sensing. IEEE Netw. 2025, 39, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirimtat, A.; Krejcar, O.; Kertesz, A.; Tasgetiren, M.F. Future Trends and Current State of Smart City Concepts: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 86448–86467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Riaz, S.; Abid, A.; Abid, K.; Naeem, M.A. A Survey on the Role of IoT in Agriculture for the Implementation of Smart Farming. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156237–156271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollschlaeger, M.; Sauter, T.; Jasperneite, J. The Future of Industrial Communication: Automation Networks in the Era of the Internet of Things and Industry 4.0. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2017, 11, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bazarevsky, V.; Vakunov, A.; Tkachenka, A.; Sung, G.; Chang, C.L.; Grundmann, M. Mediapipe hands: On-device real-time hand tracking. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10214. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, T.; Joo, H.; Matthews, I.; Sheikh, Y. Hand Keypoint Detection in Single Images using Multiview Bootstrapping. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.07809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Lu, P.; Zhang, L.; Ma, N.; Han, R.; Lyu, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, K. RTMPose: Real-Time Multi-Person Pose Estimation based on MMPose. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.07399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Xu, H.; Cai, W.; Mo, Y.; Wei, L. A human pose estimation network based on YOLOv8 framework with efficient multi-scale receptive field and expanded feature pyramid network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarevsky, V.; Kartynnik, Y.; Vakunov, A.; Raveendran, K.; Grundmann, M. Blazeface: Sub-millisecond neural face detection on mobile gpus. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.05047. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Model Card Hand Tracking (Lite/Full) with Fairness Oct 2021. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/mediapipe-assets/Model%20Card%20Hand%20Tracking%20(Lite_Full)%20with%20Fairness%20Oct%202021.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Google. Model Card Gesture Classification with Fairness 2022. 2022. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/mediapipe-assets/gesture_recognizer/model_card_hand_gesture_classification_with_faireness_2022.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Google. Hand Land Mark Medipipe. 2022. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/edge/mediapipe/solutions/vision/hand_landmarker (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aspect | Previous Works | GECO Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Gesture Sensing | IMU-based wearable sensors [37,39] or specialized cameras/gloves [16,40]. | Fully markerless vision-based sensing using standard mobile cameras and MediaPipe, no specialized hardware required. |

| Device Control Architecture | Device selection mainly, partial actuation [37]. External servers are often involved. | Full end-to-end IoT device control using private MQTT-based network, from gesture to actuation. |

| Gesture Recognition Technique | SVM [39], RVM [36], or CNNs with large datasets [18,41]. | Lightweight MediaPipe hand landmark detection with real-time classification, no heavy retraining or large datasets required. |

| User Interaction Model | Single-hand gesture systems for both selection and command [15,18]. | Two-hand, two-phase interaction (right hand for navigation, left hand for commands), improving usability and reducing errors. |

| Inclusivity Focus | Works focused on specific disabilities (e.g., deaf users [41], elderly users [20]). | Designed for a broad range of users, including the elderly, nonverbal, and non-technical users, promoting intuitive and accessible interaction. |

| Intensity/Analog Control | Most systems provide binary (on/off) commands [37,39,42]. | Introduced continuous control (e.g., light dimming) using thumb-index angle computation for analog intensity settings. |

| Privacy and Local Processing | Often cloud-reliant solutions with external processing [21,42]. | Fully private local processing: local Wi-Fi and MQTT network without external data transmission, enhancing security and privacy, and reducing latency. |

| Device Model | Android Version |

|---|---|

| Galaxy Tab S9 | Android 14.0 |

| Galaxy A54 | Android 14.0 |

| Edge Neo | Android 13.0 |

| Moto Z | Android 9.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lopes, M.C.; Silva, P.A.; Marenco, L.; Vilas Boas, E.C.; Carvalho, J.G.A.d.; Ferreira, C.A.; Carvalho, A.L.O.; Guimarães, C.V.R.; Aquino, G.P.; P. de Figueiredo, F.A. GECO: A Real-Time Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller for Advanced IoT Home System. Sensors 2026, 26, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010061

Lopes MC, Silva PA, Marenco L, Vilas Boas EC, Carvalho JGAd, Ferreira CA, Carvalho ALO, Guimarães CVR, Aquino GP, P. de Figueiredo FA. GECO: A Real-Time Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller for Advanced IoT Home System. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Murilo C., Paula A. Silva, Ludwing Marenco, Evandro C. Vilas Boas, João G. A. de Carvalho, Cristiane A. Ferreira, André L. O. Carvalho, Cristiani V. R. Guimarães, Guilherme P. Aquino, and Felipe A. P. de Figueiredo. 2026. "GECO: A Real-Time Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller for Advanced IoT Home System" Sensors 26, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010061

APA StyleLopes, M. C., Silva, P. A., Marenco, L., Vilas Boas, E. C., Carvalho, J. G. A. d., Ferreira, C. A., Carvalho, A. L. O., Guimarães, C. V. R., Aquino, G. P., & P. de Figueiredo, F. A. (2026). GECO: A Real-Time Computer Vision-Assisted Gesture Controller for Advanced IoT Home System. Sensors, 26(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010061