Calibration Method for Large-Aperture Antenna Surface Measurement Based on Spatial Ranging Correction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Error Analysis and Modeling

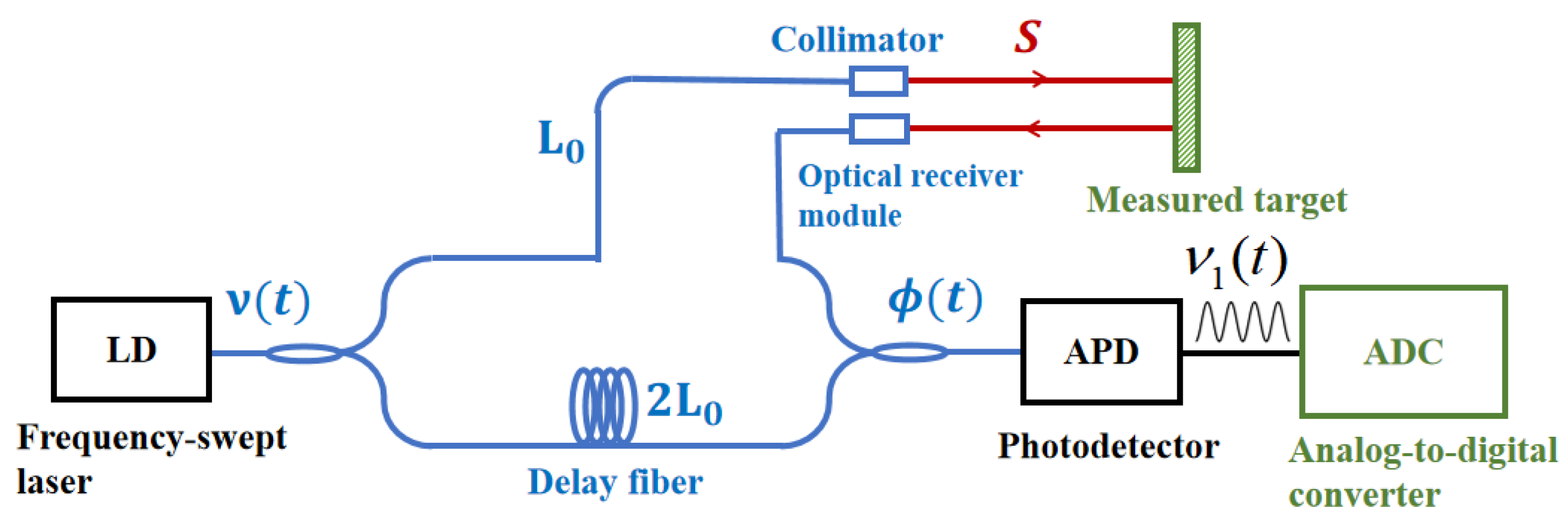

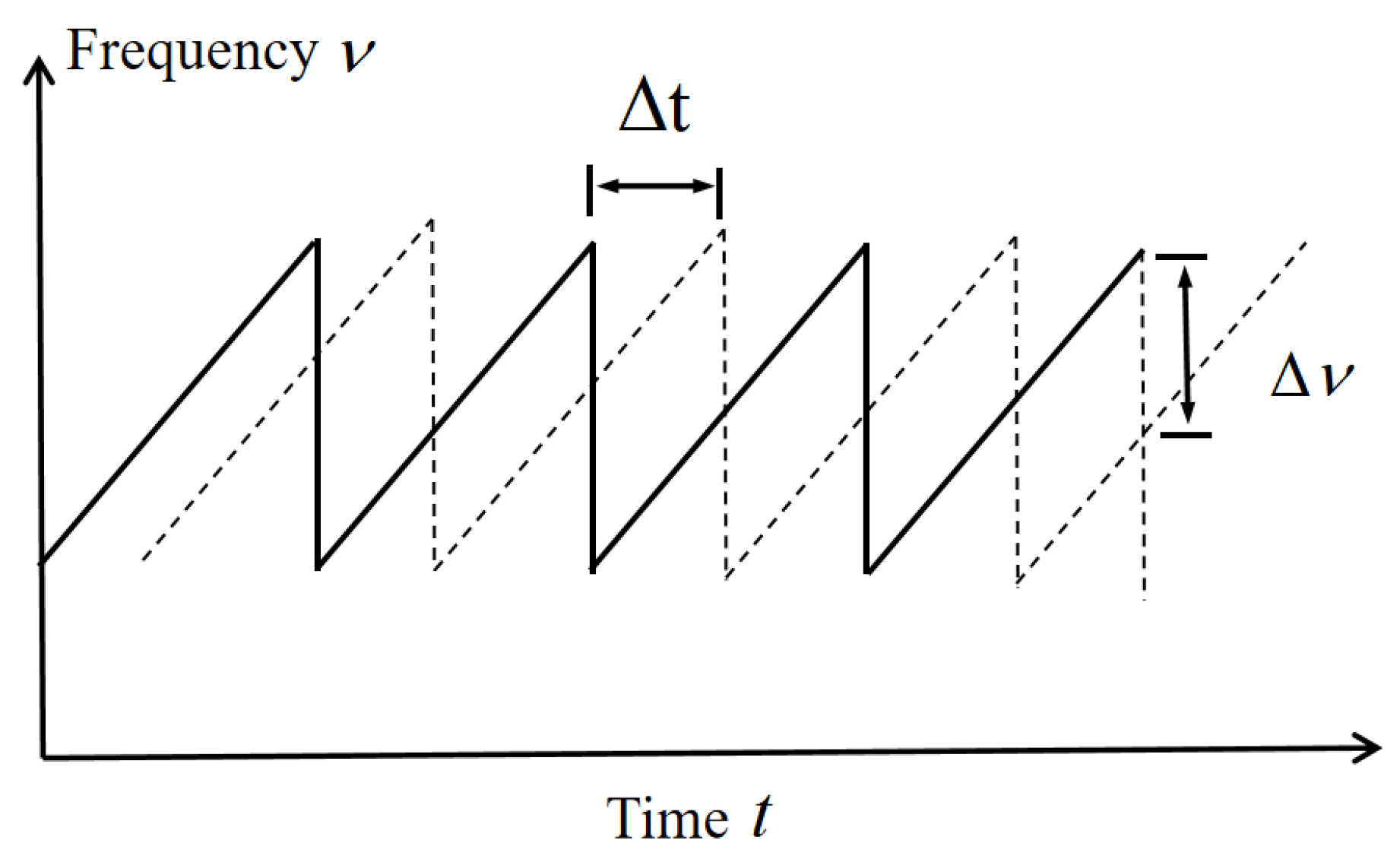

2.1.1. FMCW System Principle

2.1.2. System Error Analysis

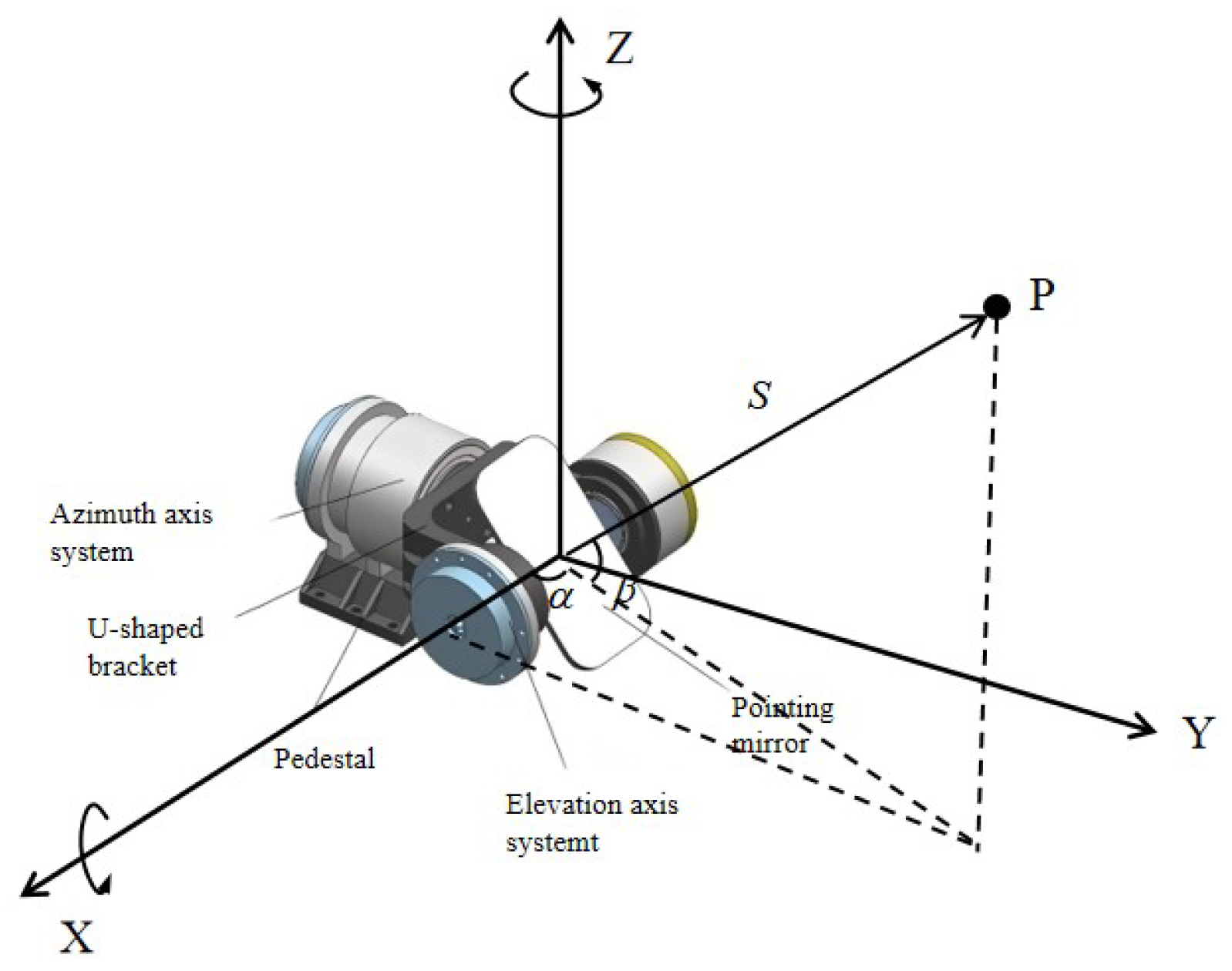

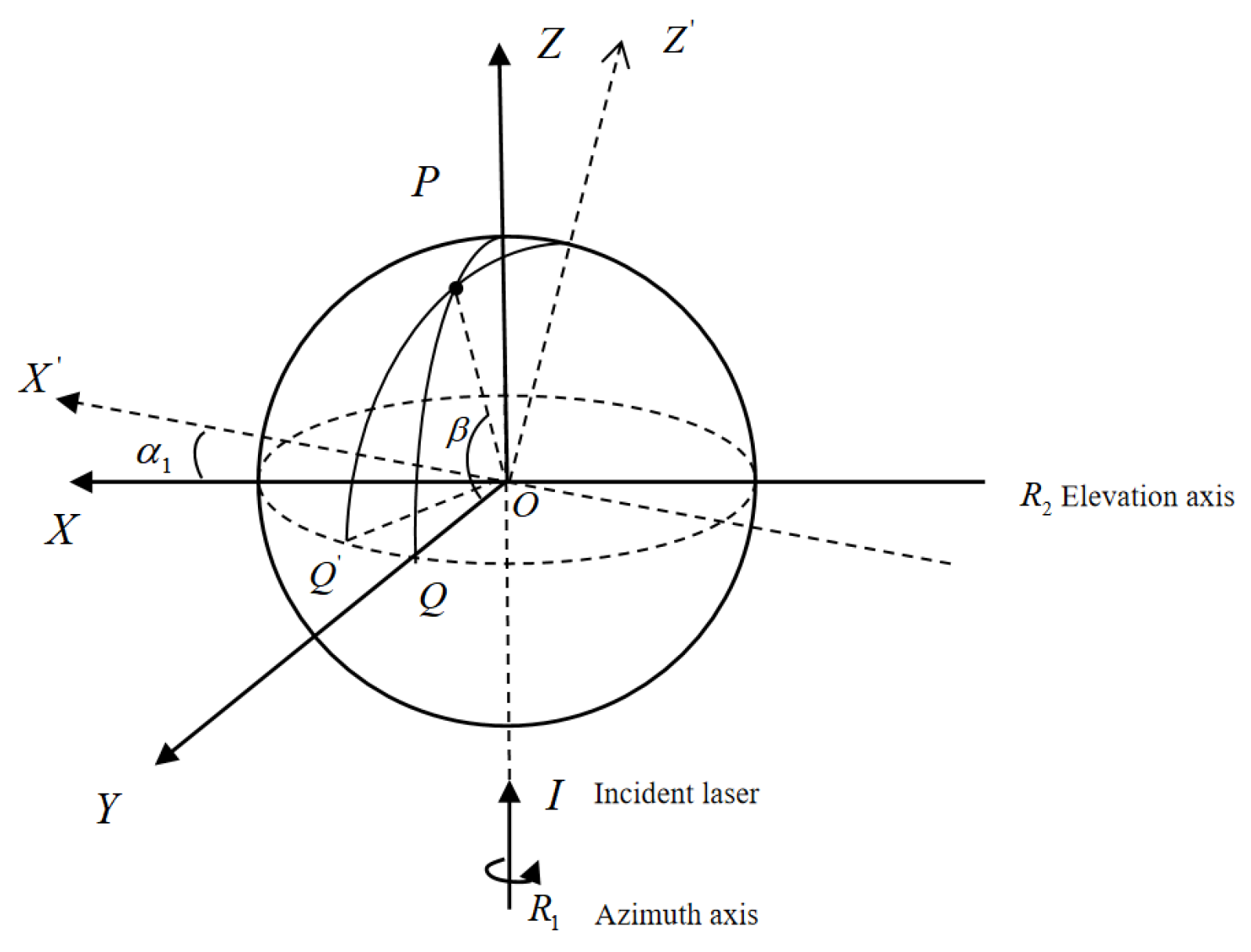

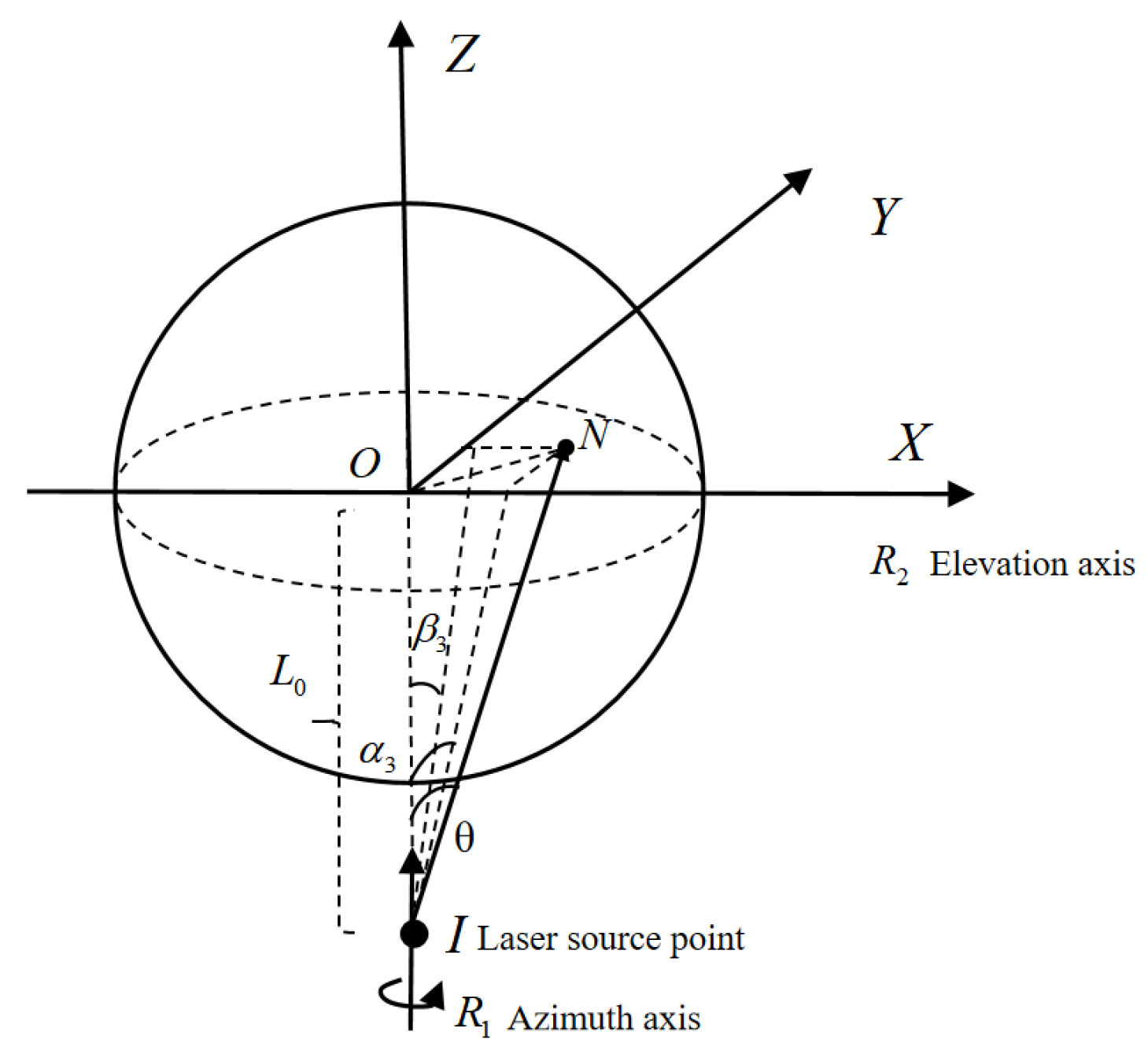

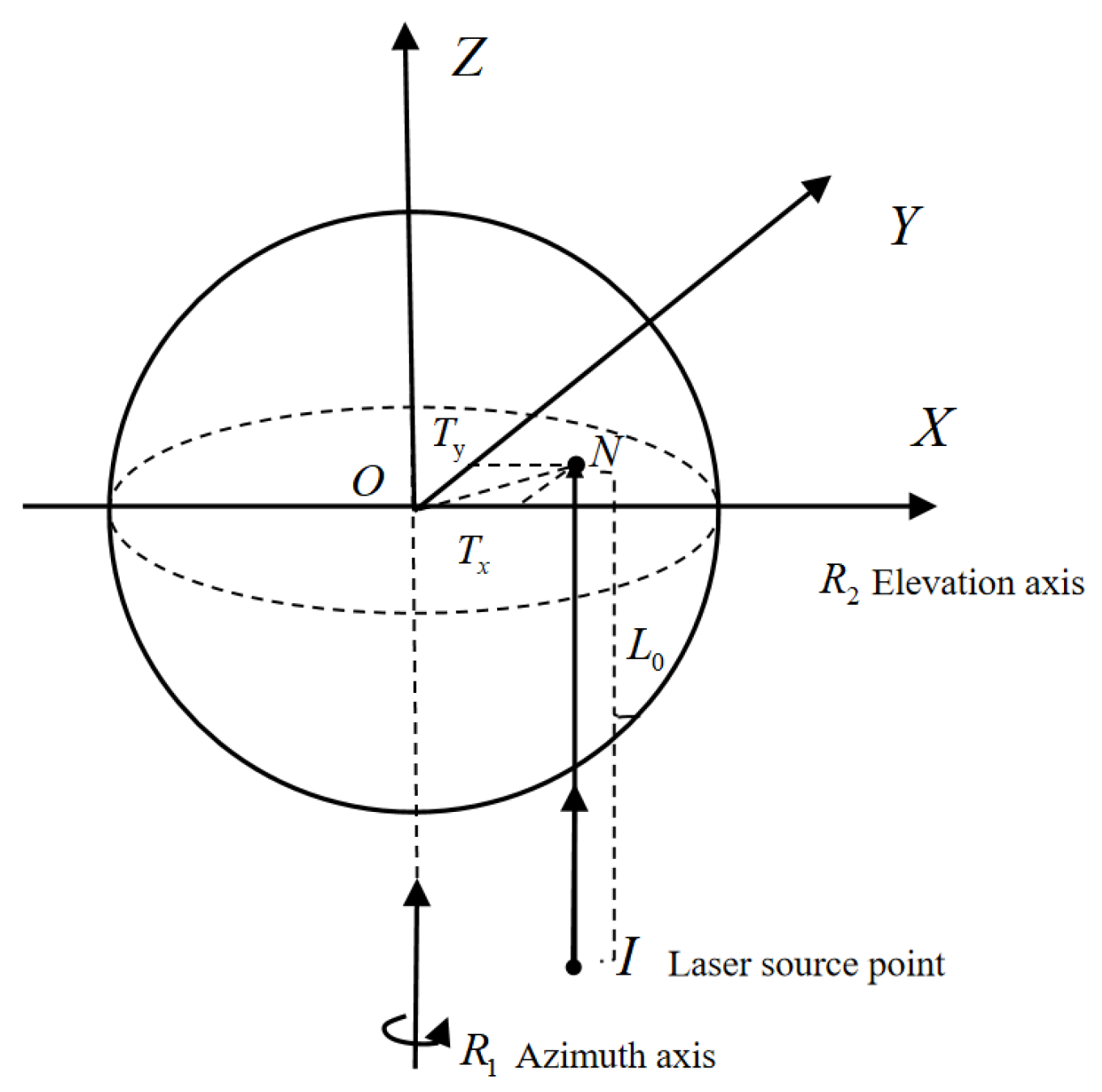

Rotation Axis Deviation

Scanning Mirror Deviation

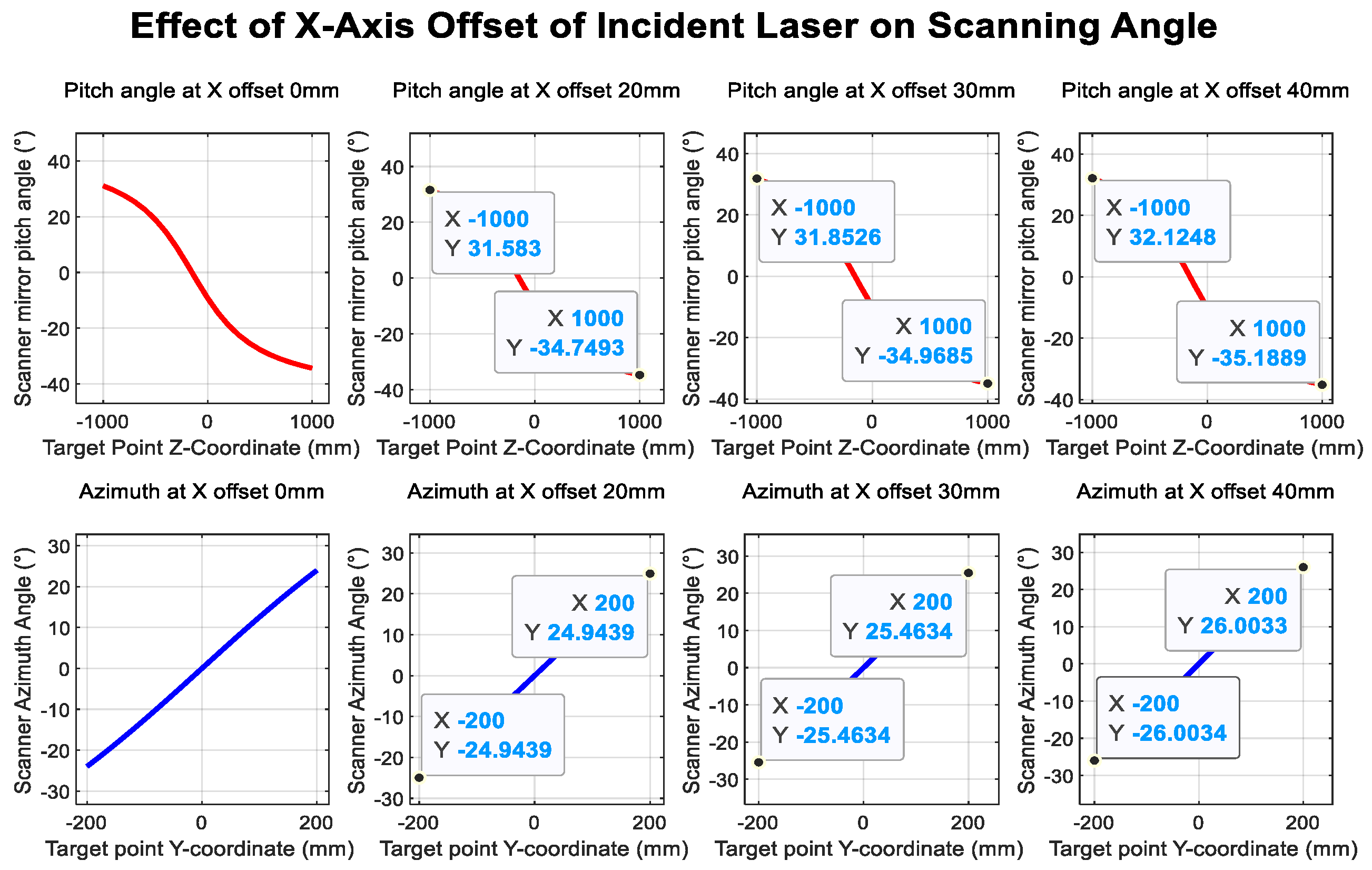

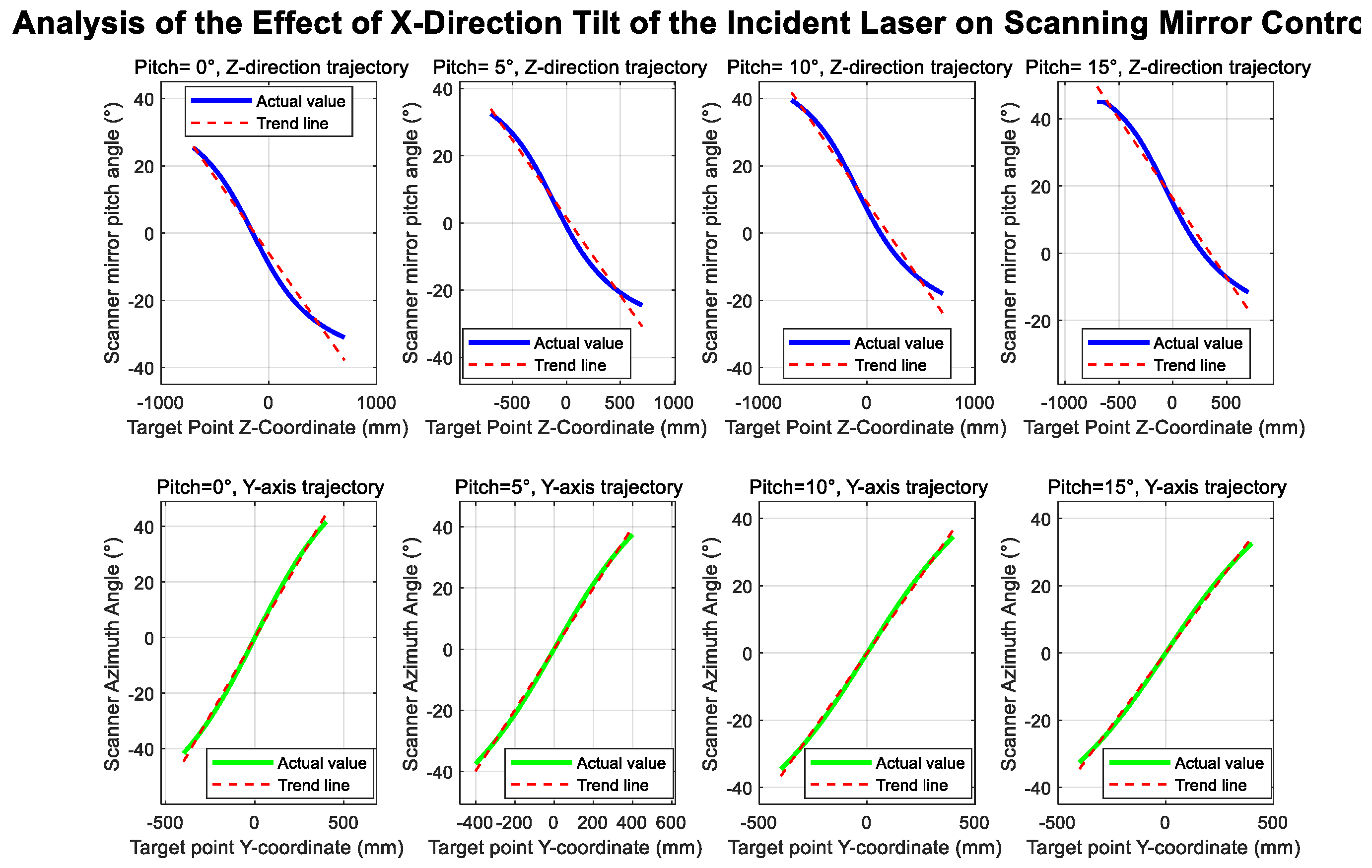

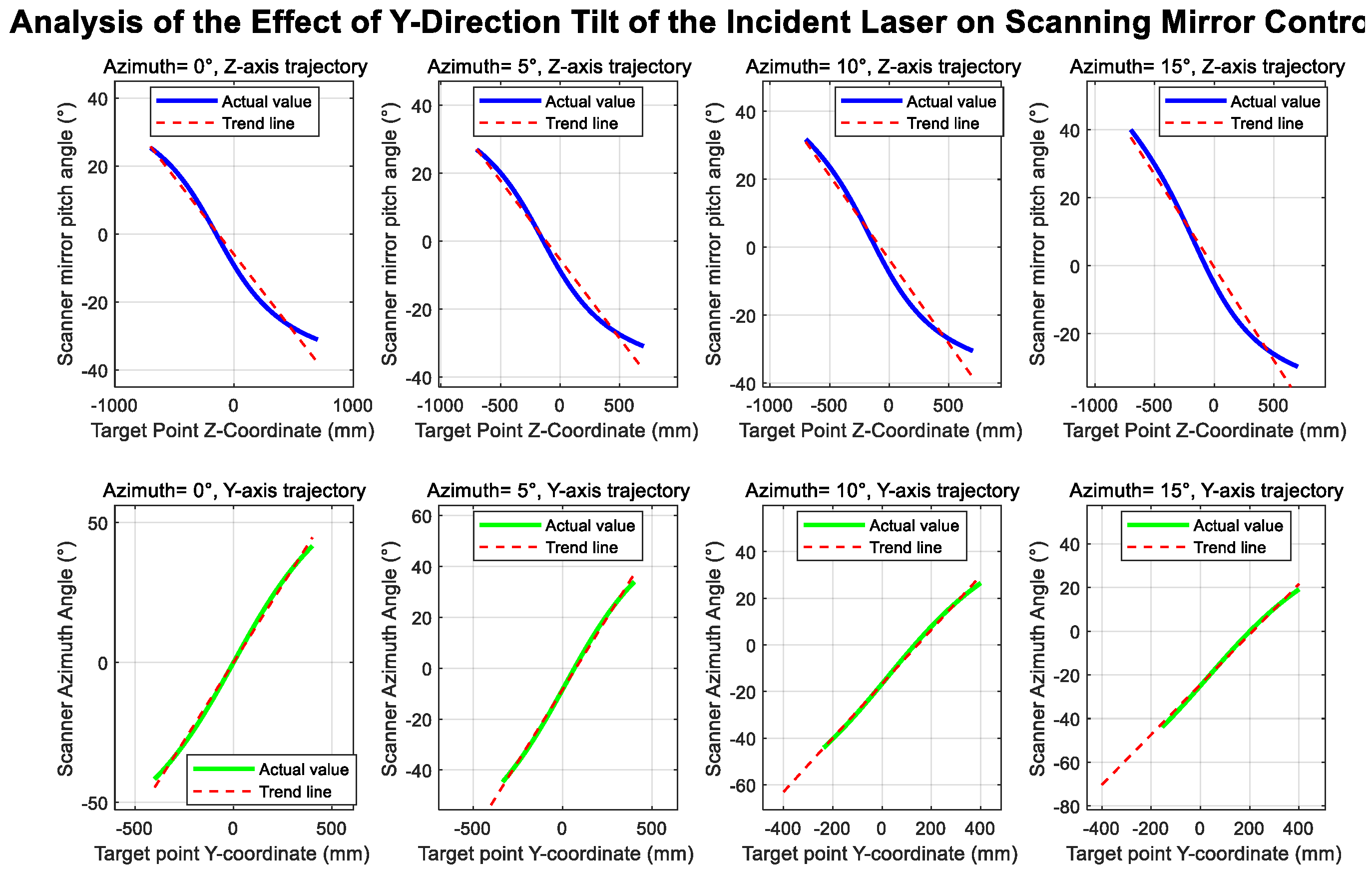

Incident Laser Deviation

Angle Measurement Module Deviation

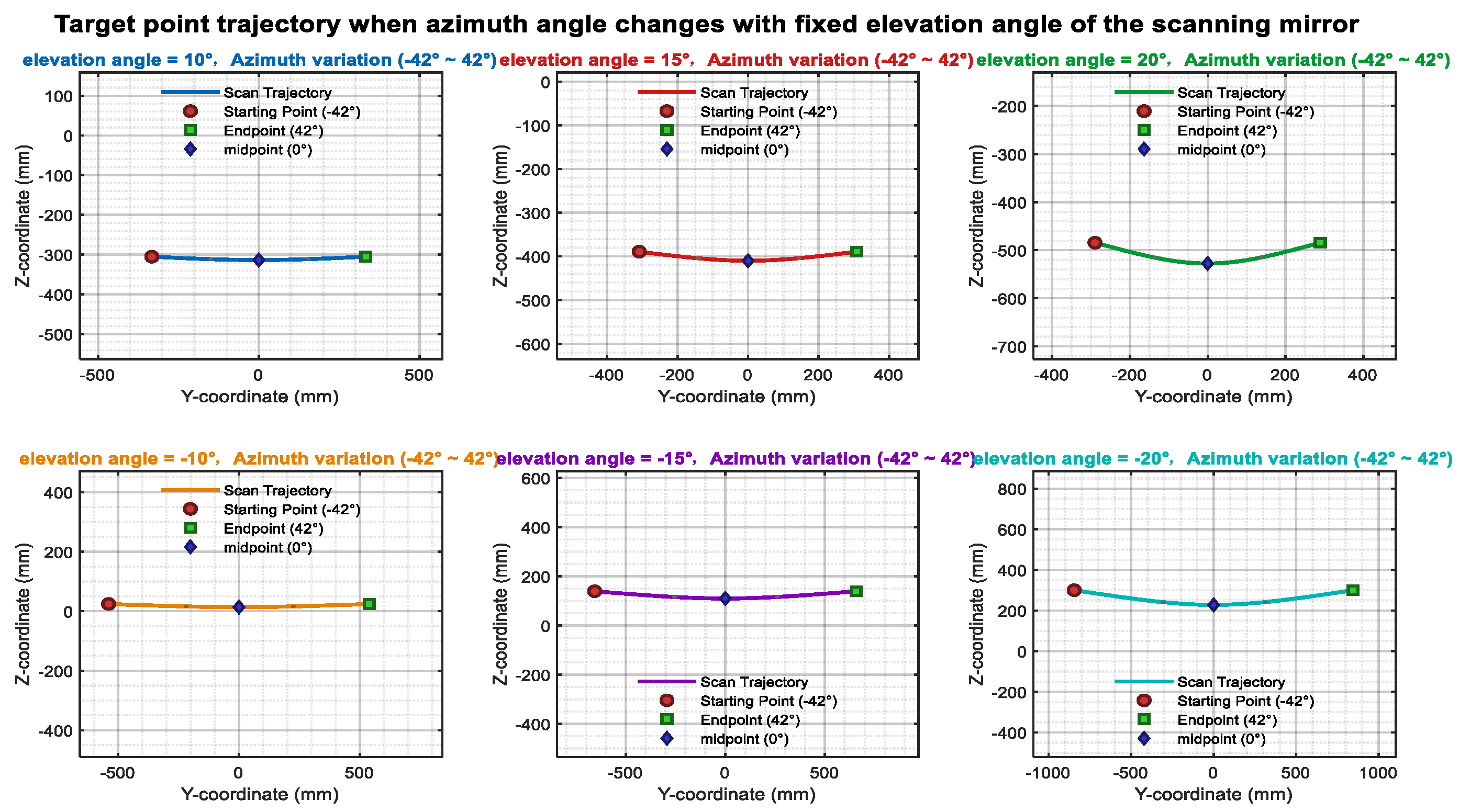

2.1.3. Simulation Model

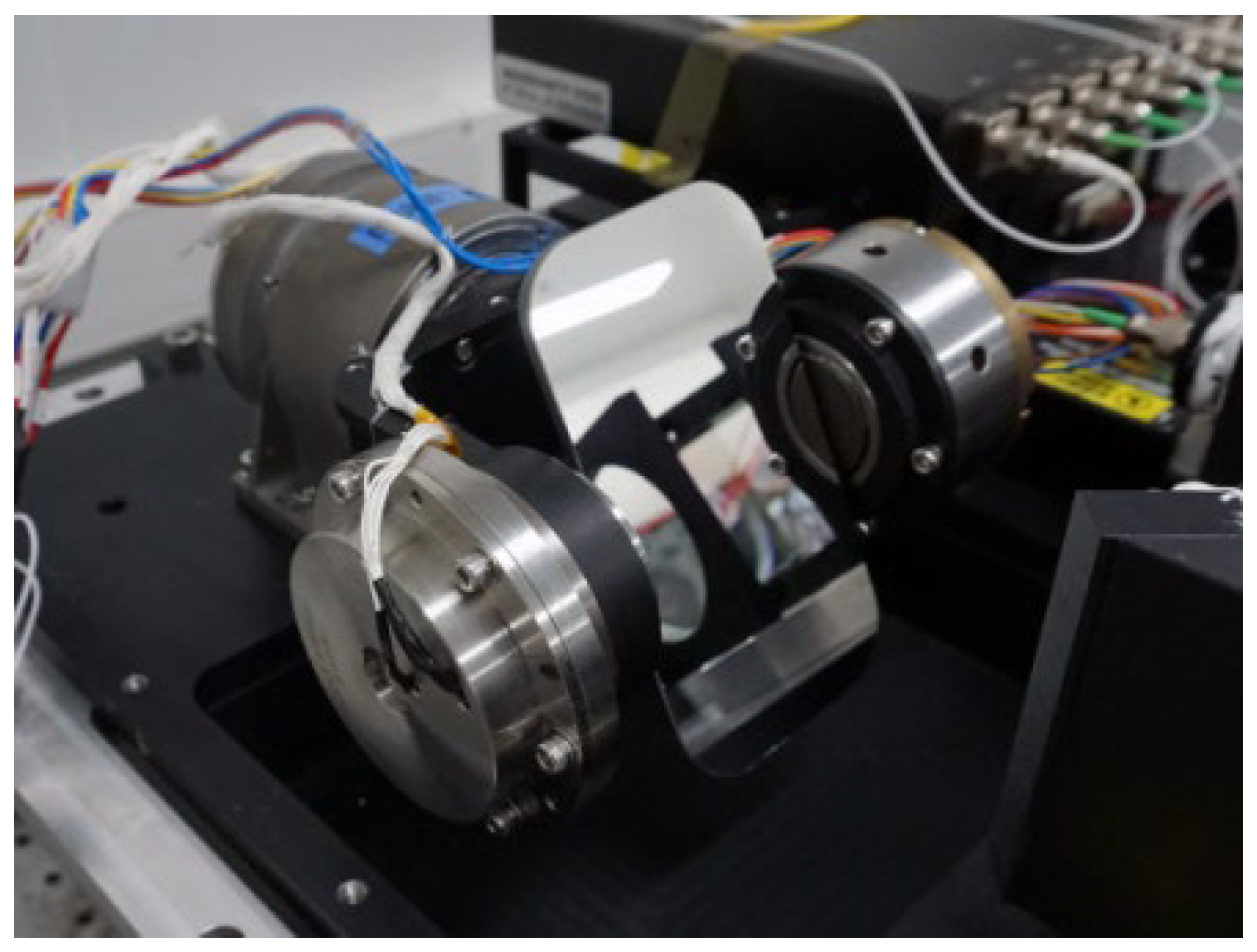

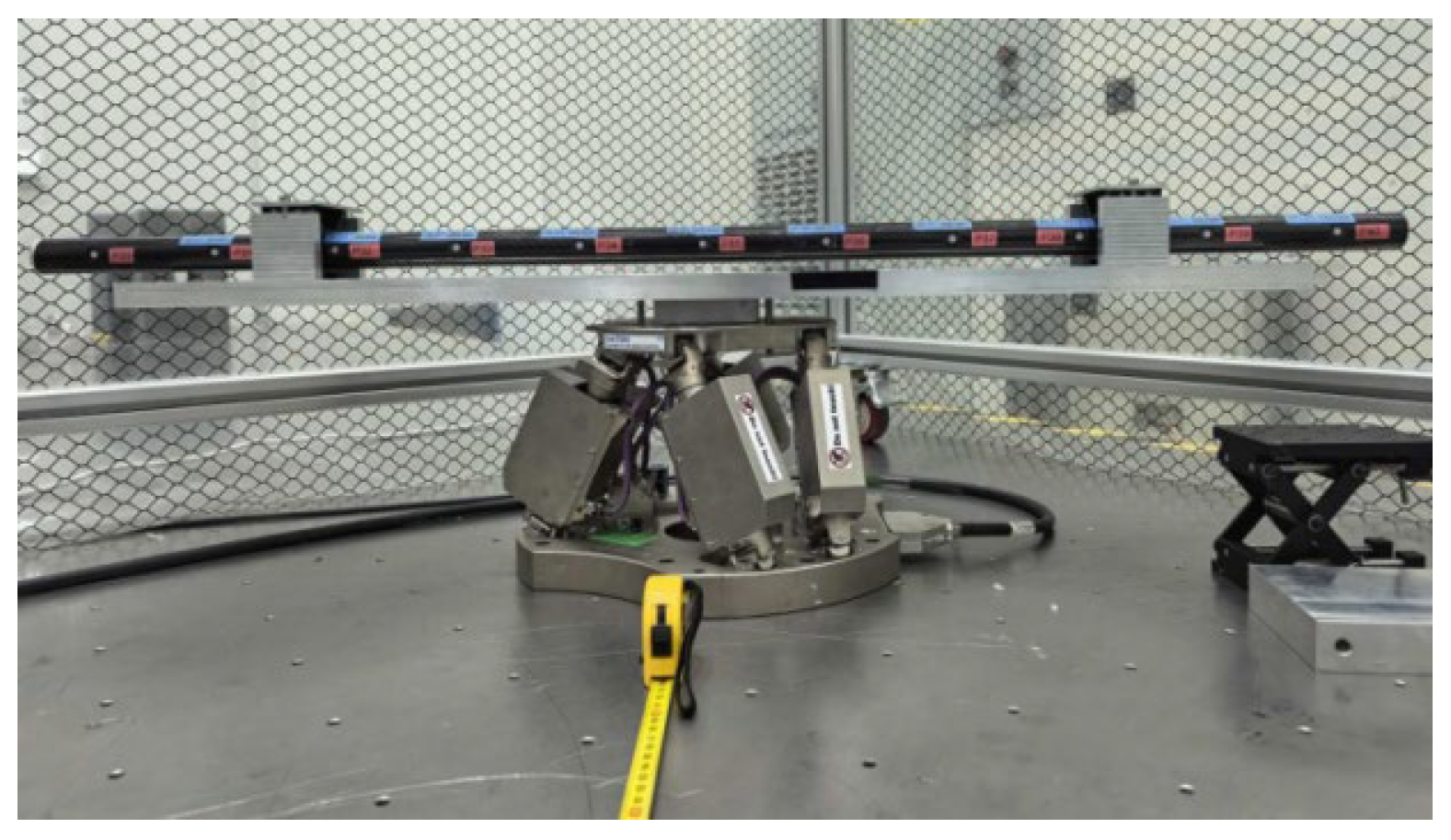

2.2. Experimental Design and Implementation

2.2.1. Selection of Calibration Method

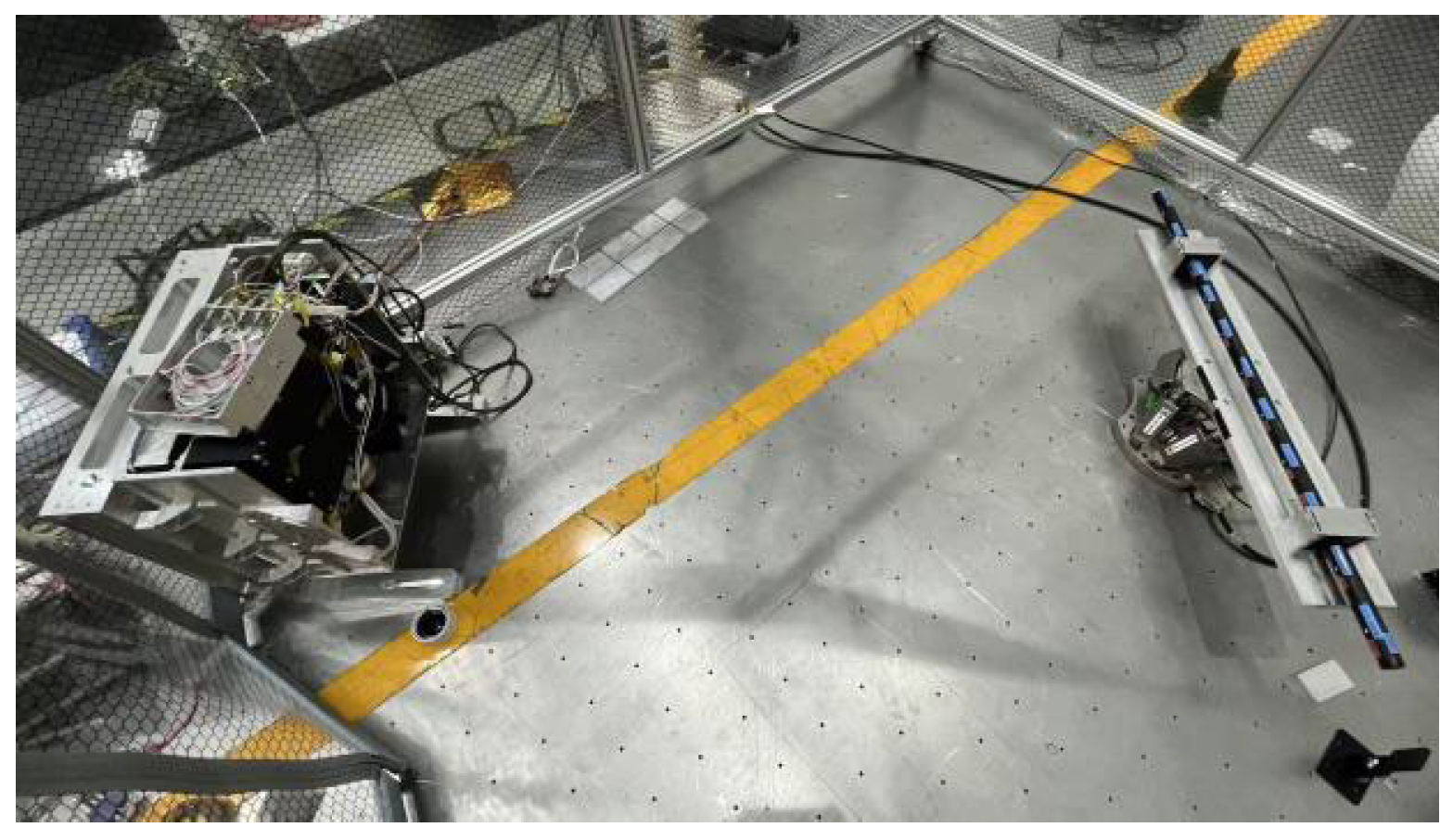

2.2.2. Experimental Design and Data Acquisition

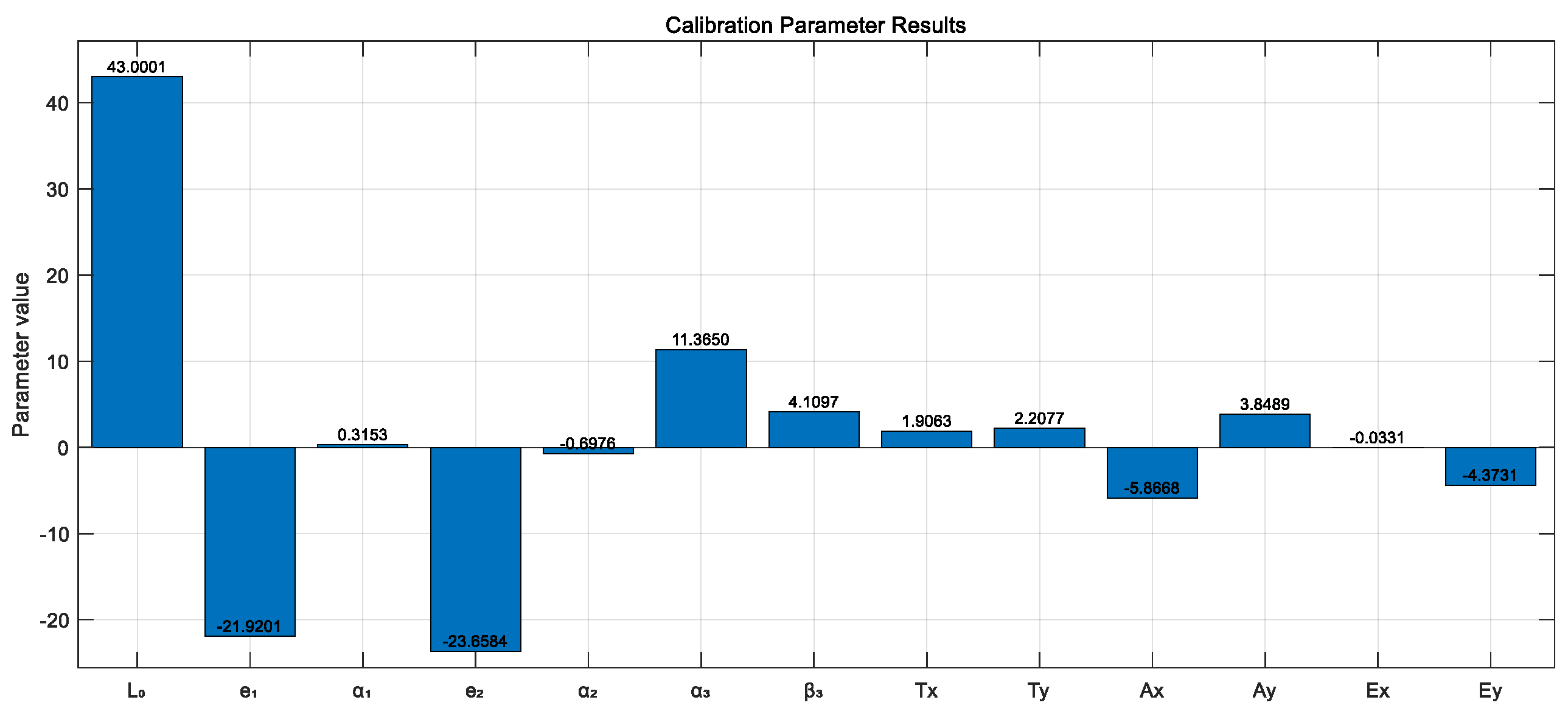

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, T.Y.; Zhang, F.M.; Wu, H.Z.; Qu, X.H.; Li, J.S.; Shi, Y.Q. Absolute distance ranging by means of chirped pulse interferometry. Acta Phys. Sin. 2016, 65, 020601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Pollinger, F.; Meiners-Hagen, K.; Krystek, M.; Tan, J.; Bosse, H. Absolute distance measurement by dual-comb interferometry with multi-channel digital lock-in phase detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2015, 26, 084001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xue, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, G.; Han, C. Calibration Method of Frequency Scanning Interferometry Laser Ranging System. Acta Opt. Sin. 2024, 44, 1412001. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Chen, X.; Xue, L.; Chen, G.; Han, C. Design of Frequency Scanning Interferometry Laser Ranging System. Acta Opt. Sin. 2024, 44, 1800011. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, N.K.; Zhang, F.M.; Qu, X.H. Ranging technology for frequency modulated continuous wave laser based on phase difference frequency measurement. Chin. J. Lasers 2018, 45, 1104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Long, M.; Ding, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, H.; He, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, Z. Research Progress of Long-Distance and High-Precision Frequency-Modulated Continuous Wave Laser Measurement Technology. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2025, 62, 0100003. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Su, B.; Zhang, B.; Jin, F. Multi-interference optical circuit ranging system based on FMCW laser radar. J. Appl. Opt. 2025, 46, 739–749. [Google Scholar]

- Luming, S.; Fumin, Z.; Dong, S.; Hongyi, L.; Xiaohua, H.; Miao, Y.; Qian, Z. Research progress of absolute distance measurement methods based on tunable laser frequency sweeping interference. Infrared Laser Eng. 2022, 51, 20210406-1–20210406-15. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K.; Hocken, R.; Haynes, L. Robot performance measurements using automatic laser tracking techniques, Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 1985, 2, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, S.; Loser, R. Alignment and field check procedures for the leica laser tracker LTD 500. In Proceedings of the Boeing Large Scale Optical Metrology Seminar, Denver, CO, USA, 18–19 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Muralikrishnan, B.; Ferrucci, M.; Sawyer, D.; Gerner, G.; Lee, V.; Blackburn, C.; Phillips, S.; Petrov, P.; Yakovlev, Y.; Astrelin, A.; et al. Volumetric performance evaluation of a laser scanner based on geometric error model. Precis. Eng. 2015, 40, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.; Forbes, A.; Lewis, A.; Sun, W.; Veal, D.; Nasr, K. Laser tracker error determination using a network measurement. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 045103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, J.; Majarena, A.C.; Acero, R.; Santolaria, J.; Aguilar, J.J. Performance evaluation of laser tracker kinematic models and parameter identification. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2015, 77, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icasio-Hernández, O.; Bellelli, D.A.; Vieira, L.H.B.; Cano, D.; Muralikrishnan, B. Validation of the network method for evaluating uncertainty and improvement of geometry error parameters of a laser tracker. Precis. Eng. 2021, 72, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishnan, B.; Wang, L.; Rachakonda, P.; Sawyer, D. Terrestrial laser scanner geometric error model parameter correlations in the two-face, length-consistency, and network methods of self-calibration. Precis. Eng. 2018, 52, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Zhu, J.G.; Zhou, W.H. Error calibration and correction of mirror tilt in laser trackers. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2015, 23, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Shi, Z.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y. Error Analysis and Accuracy Assurance of Two-Dimensional Rotatory Axes for Laser Tracing Measurement System. Chin. J. Lasers 2018, 45, 0504001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Lao, D.; Dong, D.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, W. Calibration method for initial position of miss distance in femtosecond laser tracker. Infrared Laser Eng. 2017, 46, 117001. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.J.; Lao, D.; Gao, S. Calibration for coaxiality of optical axis and vertical rotary shaft in femtosecond laser tracker. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2016, 24, 2651–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lou, Z.; Tian, Y. Error analysis and compensation of 3D laser ball bar. Instrum. Tech. Sens. 2020, 3, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Bao, C.; Tan, J. Model establishment and error correction of FMCW lidar. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2023, 31, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Dong, D.; Li, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Wang, J.; Huo, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, W. High-precision attitude measurement with active aiming composite sensing for laser tracker. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2025, 33, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, D.; Zhou, W.; Ji, R.; Pan, Y.; Wang, G.; Cui, C. Calibration and correction of geometric errors in laser tracker. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2024, 32, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, W.J.; Gao, L.M.; Yang, Y.Q. Calibration and compensation of angular error in laser tracker. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2015, 36, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, H.; Dai, C. Eccentric measuring approach of circular grating by diffracted light nterference. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 35, 128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S.; Wu, T.; Qu, H. Evaluation Method for Error Calibration of Laser Tracking Measurement Systems. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2025, 62, 0712002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.J.; Ma, Z.J. Multi parameter error model and calibration of laser tracker. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2020, 41, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

| Sensitivity Coefficient | Expression | Sensitivity Coefficient | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Point | Coordinate the Position of the Target Point | Relative Distance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | −0.09767 | ||

| P2 | 99.9630 | P1–P2 | 99.8653 |

| P3 | 199.8654 | P1–P3 | 199.7677 |

| P4 | 299.9220 | P1–P4 | 299.8243 |

| P5 | 399.9737 | P1–P5 | 399.8760 |

| P6 | 499.9390 | P1–P6 | 499.8413 |

| P7 | 599.9704 | P1–P7 | 599.8727 |

| P8 | 699.9670 | P1–P8 | 699.8693 |

| P9 | 799.8787 | P1–P9 | 799.7810 |

| P10 | 899.9317 | P1–P10 | 900.0294 |

| P11 | 999.9080 | P1–P11 | 1000.0057 |

| Reference Point | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | −353.916031 | 581.241957 | 71.409689 |

| P2 | −231.911256 | 587.59416 | 96.382430 |

| P3 | −86.816273 | 595.648706 | 123.231456 |

| P4 | −332.861423 | 605.76438 | −50.24143 |

| P5 | −209.335451 | 612.572108 | −26.971376 |

| P6 | −60.291253 | 620.684316 | 1.054062 |

| P7 | −307.520477 | 633.676523 | −188.740015 |

| P8 | −187.762014 | 637.220701 | −149.484321 |

| P9 | −35.811263 | 649.246139 | −141.064106 |

| Y = 0 mm | Spatial Angle in the Camera Coordinate System | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Point | Measurement Distance | Scene Coordinate X | Scene Coordinate Y | Elevation Angle | Azimuth Angle |

| P30 | 4580.353 | 767.833 | 470.599 | −2.0601 | −12.63440 |

| P31 | 4560.628 | 765.231 | 471.359 | −10.14666 | |

| P32 | 4544.97 | 762.435 | 470.378 | −7.63283 | |

| P33 | 4533.98 | 761.02 | 469.57 | −5.08672 | |

| P34 | 4527.334 | 760.08 | 470.373 | −2.52343 | |

| P35 | 4525.243 | 760.733 | 470.83 | 0.05562 | |

| P36 | 4527.384 | 761.214 | 470.51 | 2.63125 | |

| P37 | 4534.091 | 762.954 | 471.161 | 5.18285 | |

| P38 | 4545.554 | 764.821 | 470.335 | 7.72484 | |

| P39 | 4561.233 | 767.33 | 470.593 | 10.25859 | |

| P40 | 4581.218 | 769.243 | 470.725 | 12.73534 | |

| Target Point | Measurement Distance L | Azimuth Angle α | Elevation Angle β |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 2533.63 | 29.7844 | −5.7791 |

| P2 | 2545.32 | 26.9852 | −5.6406 |

| P3 | 2566.53 | 23.7046 | −5.4157 |

| P4 | 2523.47 | 29.8798 | −2.5026 |

| P5 | 2535.14 | 27.0434 | −2.4116 |

| P6 | 2557.12 | 23.6612 | −2.3090 |

| P7 | 2519.77 | 29.8569 | 1.2605 |

| P8 | 2531.31 | 27.0474 | 0.8111 |

| P9 | 2553.34 | 23.6665 | 1.2925 |

| Source of Error | Contribution to σS4 (mm) | Contribution to σα4 (″) | Contribution to σβ4 (″) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1500 | - | - | |

| 0.2000 | - | - | |

| 0.0083 | 6.3 | - | |

| 0.0243 | 144.6 | - | |

| - | 907.0 | - | |

| - | - | 300 | |

| - | 8.3 | - | |

| - | - | 8.3 | |

| - | 1015 | - | |

| - | 246 | - | |

| - | - | 7.2 | |

| - | - | 62.8 | |

| Total | 0.2510 | 1391 | 307 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Zou, Y.; Han, C.; Chen, X.; Xue, L.; Wang, F. Calibration Method for Large-Aperture Antenna Surface Measurement Based on Spatial Ranging Correction. Sensors 2026, 26, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010312

Chen X, Zou Y, Han C, Chen X, Xue L, Wang F. Calibration Method for Large-Aperture Antenna Surface Measurement Based on Spatial Ranging Correction. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010312

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xuesong, Yaopu Zou, Changpei Han, Xiaosa Chen, Linyang Xue, and Fei Wang. 2026. "Calibration Method for Large-Aperture Antenna Surface Measurement Based on Spatial Ranging Correction" Sensors 26, no. 1: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010312

APA StyleChen, X., Zou, Y., Han, C., Chen, X., Xue, L., & Wang, F. (2026). Calibration Method for Large-Aperture Antenna Surface Measurement Based on Spatial Ranging Correction. Sensors, 26(1), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010312