Assessment and Measurement of the Side-Effects of an Evidence-Based Intervention with an Advanced Smart Cricket Ball Exemplified by a Case Report on Correcting Illegal Bowling Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To evaluate a cricket coaching process holistically using an advanced smart cricket ball, drawing on standard performance parameters provided by the device, specifically focusing on physical and skill parameters, centre of pressure position, type of spin-bowling delivery, and detection of throwing motion.

- (2)

- To detect the “side-effects” of an intervention, i.e., how the intervention influences other movement patterns and performance parameters that were not directly targeted by the intervention, specifically whether side-effects can be detected at all, how can they be measured and quantified, and which parameters are affected in the first place, by comparing performance parameters before and after the intervention.

- (3)

- To assess the suitability of the smart cricket ball for documenting coaching interventions based on its performance data (including target parameters and side effects), irrespective of the intervention’s success.

- (4)

- To apply a coaching process to bowlers with suspected illegal actions, with a particular focus on identifying and analysing the side effects of the intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Advanced Smart Cricket Ball

2.2. Participants

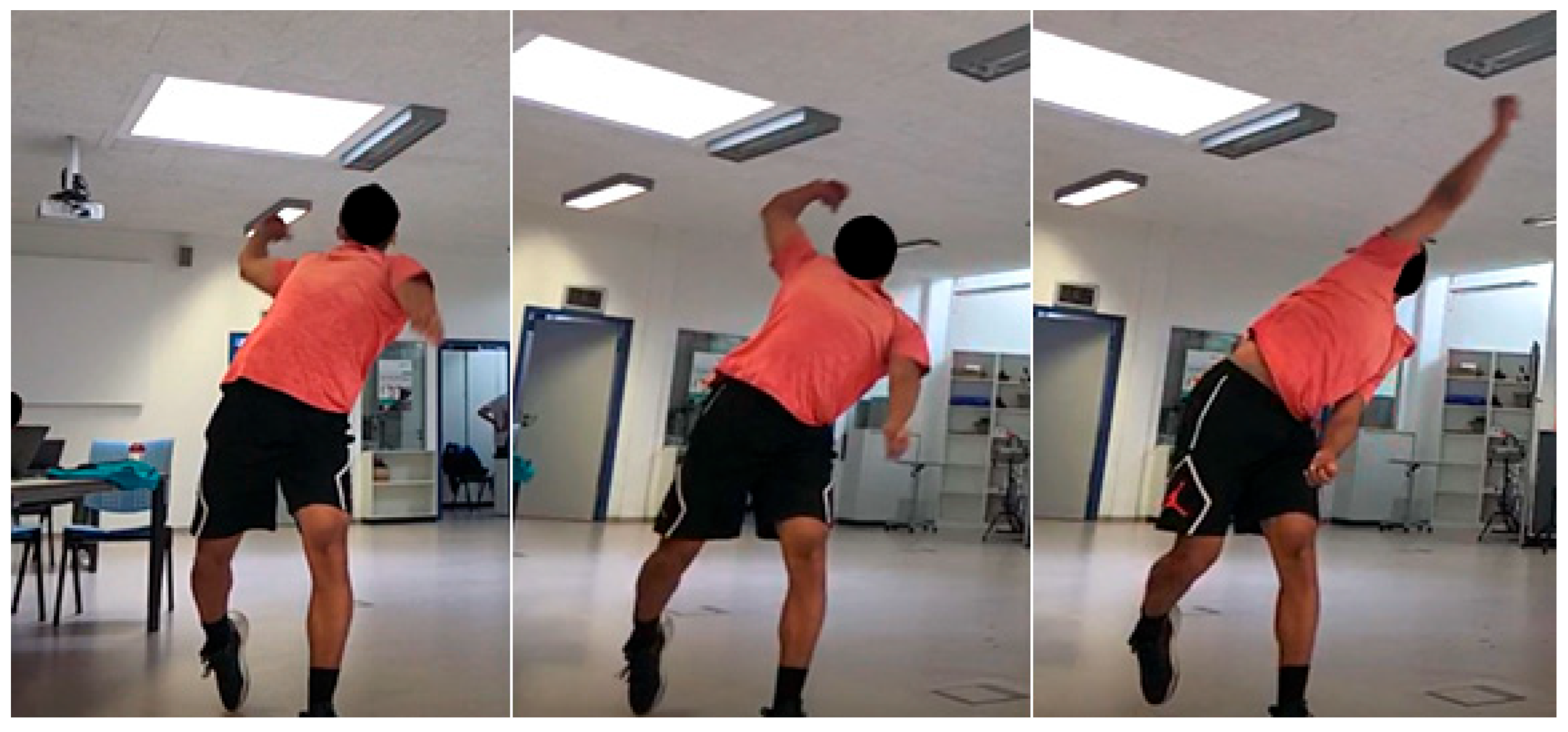

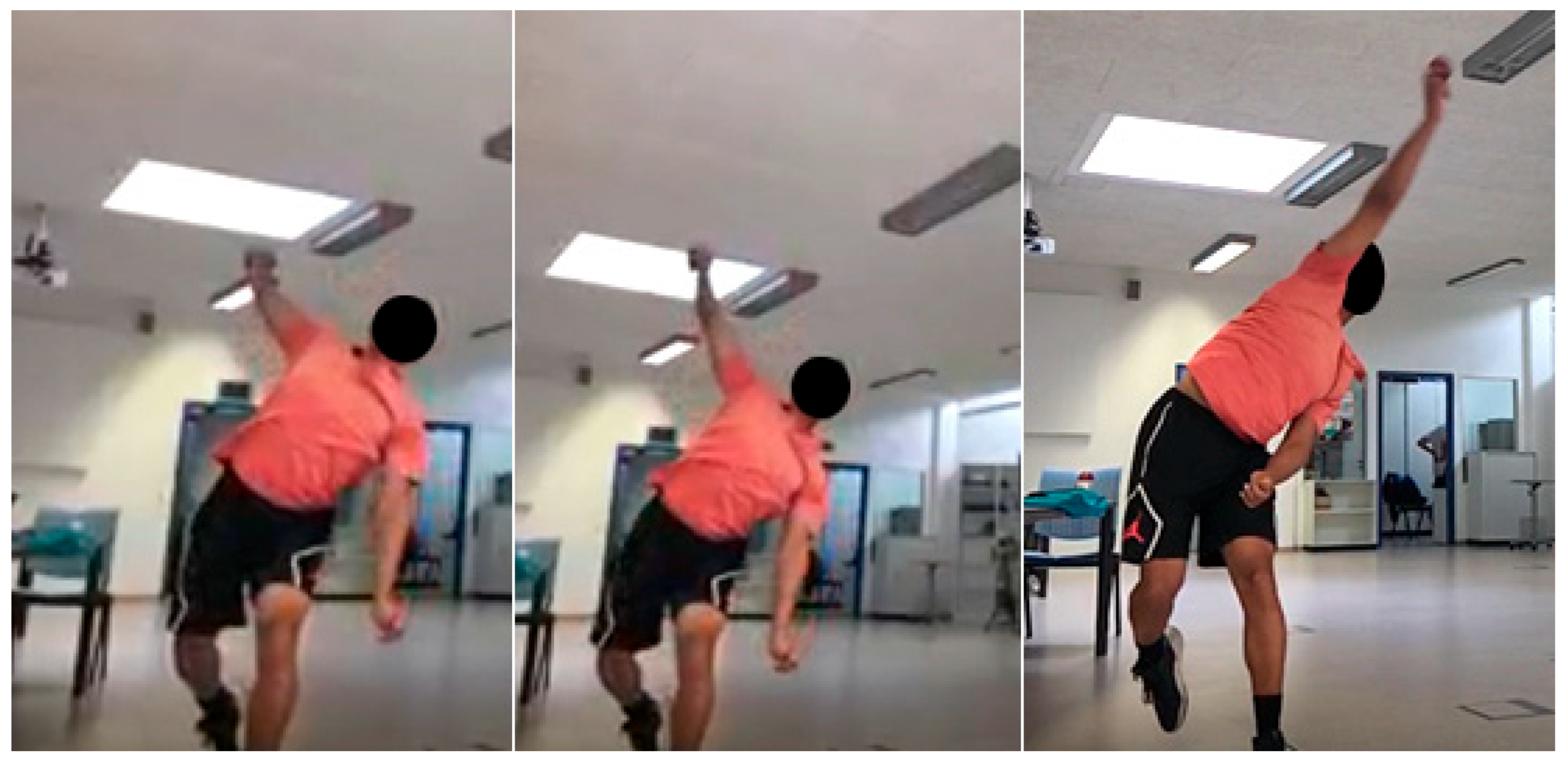

2.3. Qualitative Legality Assessment

- Excessive elbow extension during arm-acceleration—evaluation of straightening of the elbow from horizontal arm position to ball release.

- Jerky or whipping motion at release—appearance of abrupt changes in arm velocity or acceleration.

- Excessive shoulder external rotation (ER)—observation of shoulder rotation exceeding the typical anatomical range for bowlers at the horizontal arm position.

- Scapular-thoracic motion ± lumbar extension—assessment of upper back and shoulder blade movements, including compensatory lumbar extension.

- Visible elbow flexion at maximal shoulder ER—inspection of elbow bending at peak shoulder external rotation.

- Early shoulder abduction—premature lateral movement of the upper arm due to the unsupported “falling-away” of the action.

- Bowling arm above vertical at release—observation of arm position relative to vertical at the moment of release.

- Release point significantly ahead of front foot—evaluation of ball release relative to front foot position.

- Minimal trunk flexion at release or head well ahead of the front foot at release—assessment of forward bending of the torso and the relative head position.

- Minimal “V-angle” (trunk–front thigh)—inspection of the angular relationship between torso and lead thigh.

- Front-on alignment at back foot contact—evaluation of the orientation of the torso and shoulders when the back foot contact.

- Excessive lateral bending ± shoulder rotation—observation of side bending or rotation beyond normal range.

- Open stride angle ± open foot position—assessment of lead foot orientation and stride width.

- Stride length < 1.2 × shoulder width (short)—assessment of step length noticeably short, in an unathletic position.

2.4. Bowling Trials

2.5. Intervention Trials

2.6. Data Analysis

- (a)

- Ten performance parameters (5 physical and 5 skill) were calculated for each ball played before and after the intervention, using the smart ball software [27] (Smart Cricket Ball Analysis, version 21, proprietary software of F. K. Fuss and B. Doljin).

- (b)

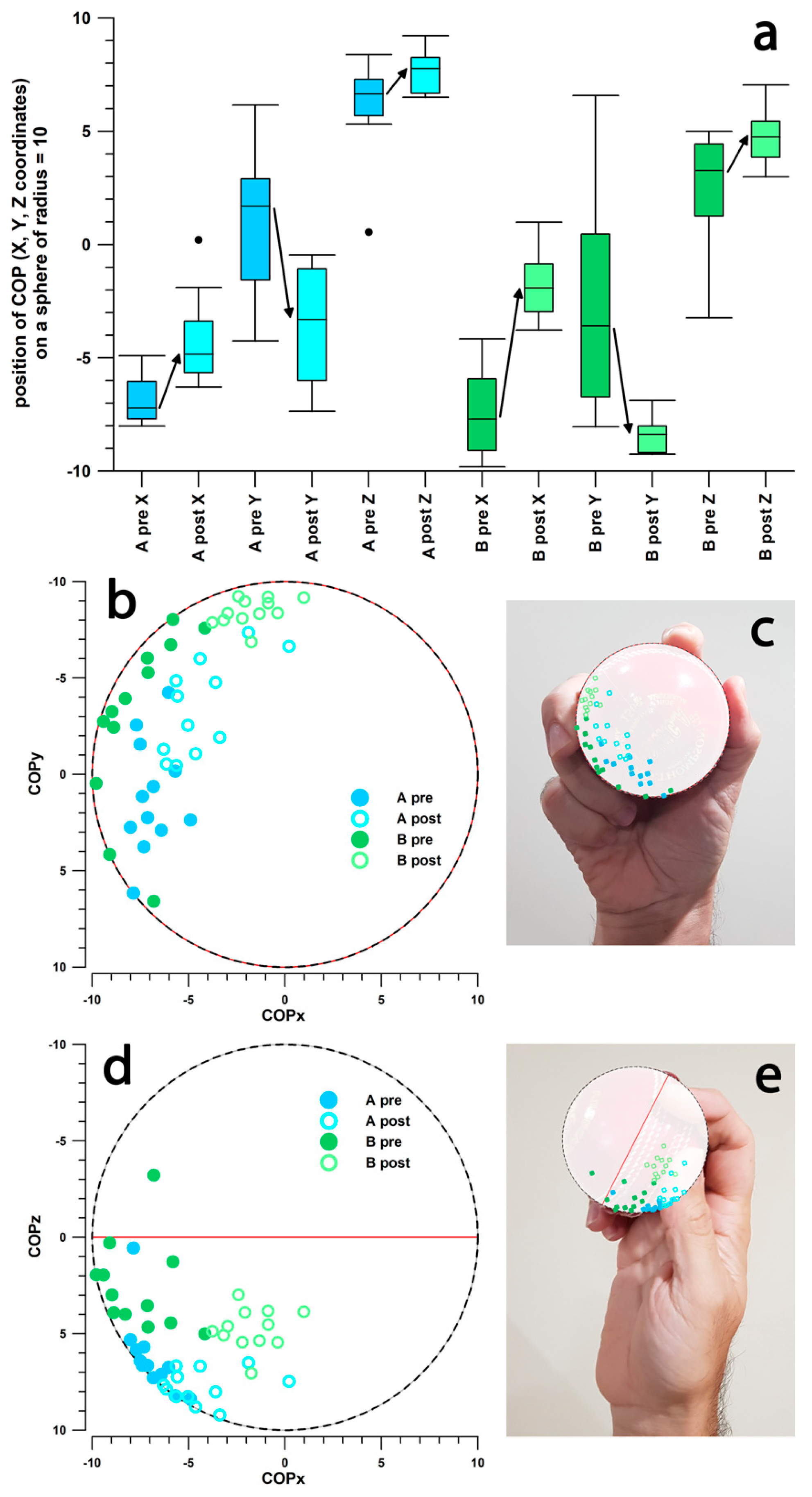

- The centre of pressure, which represents the point of torque application, was calculated according to the protocol of Fuss et al. [51]. For comparison purposes, the bowling hand was aligned with the ball’s coordinate system (BCS), the index finger was placed on the x-axis (seam plane = xy-plane), and the z-axis (pole of the ball) pointed into the palm of the right hand.

- (c)

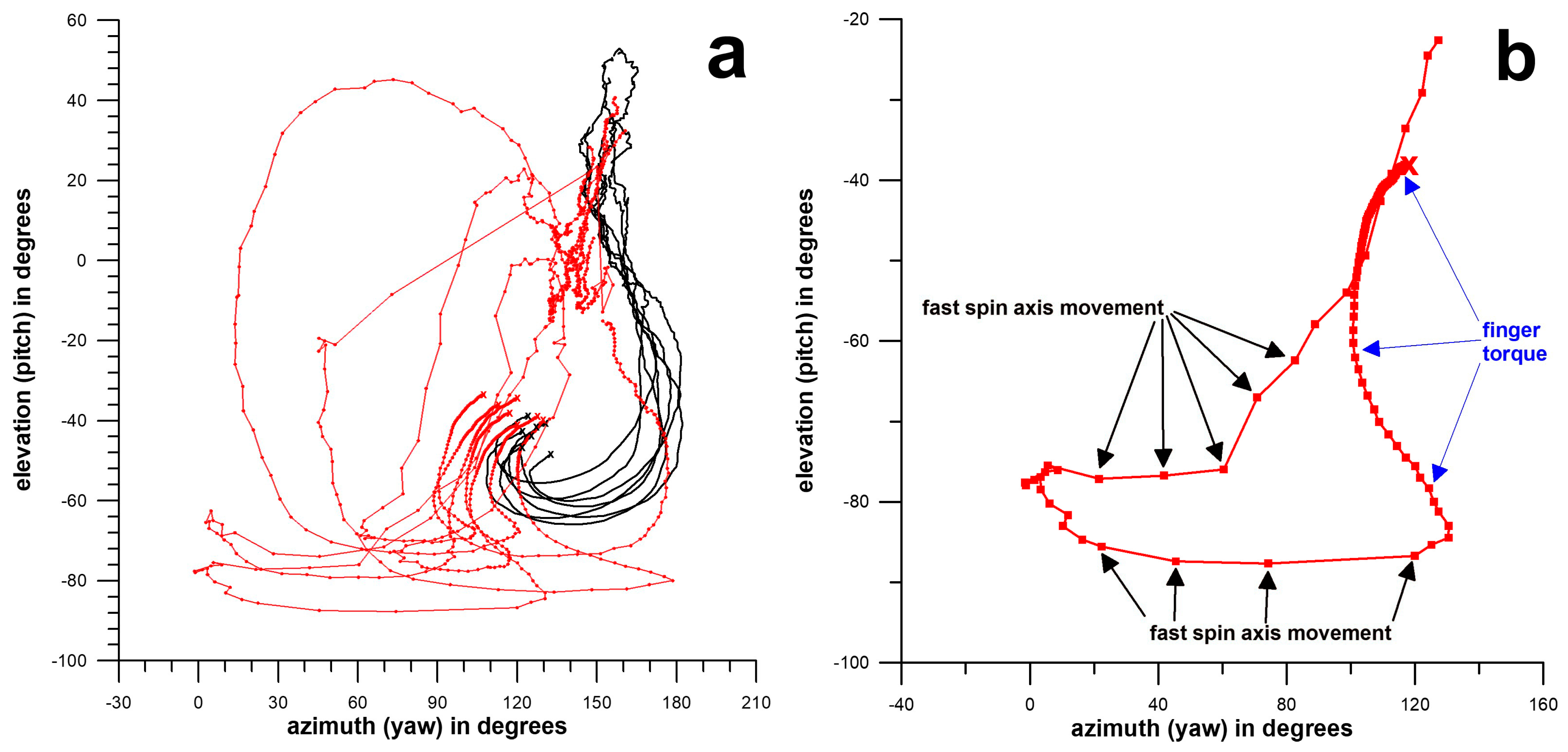

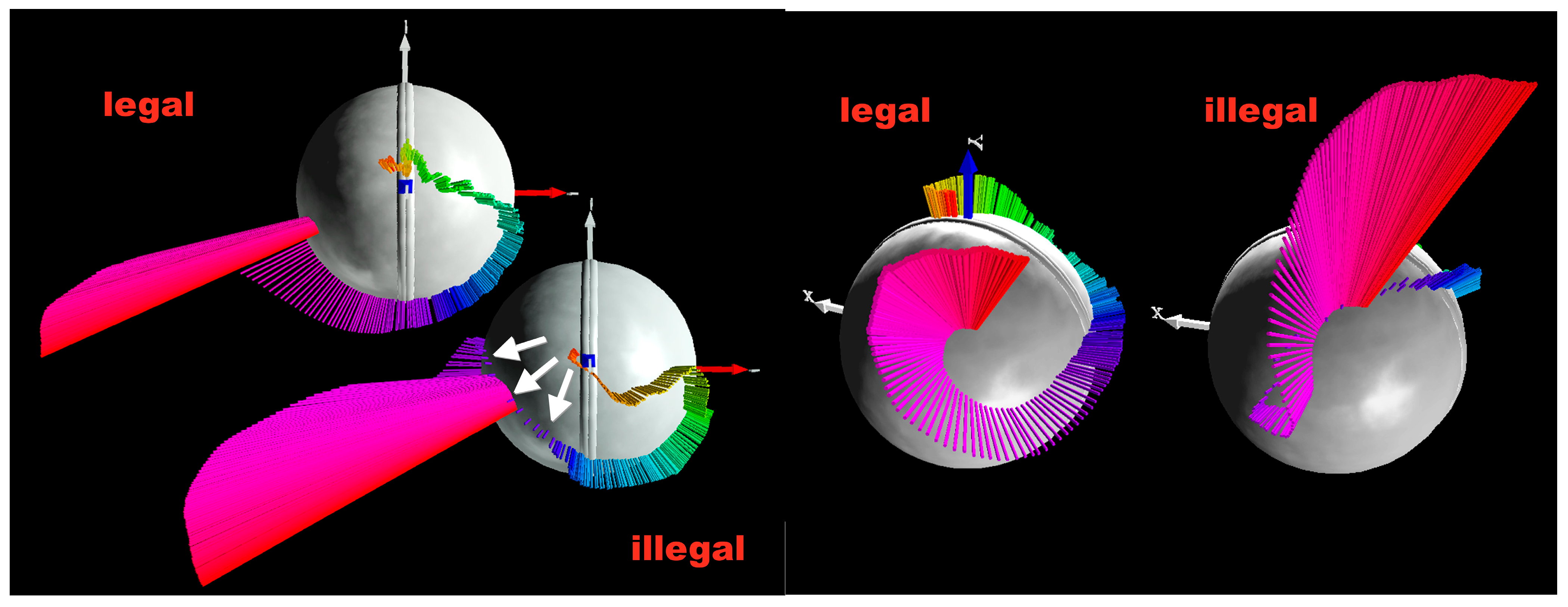

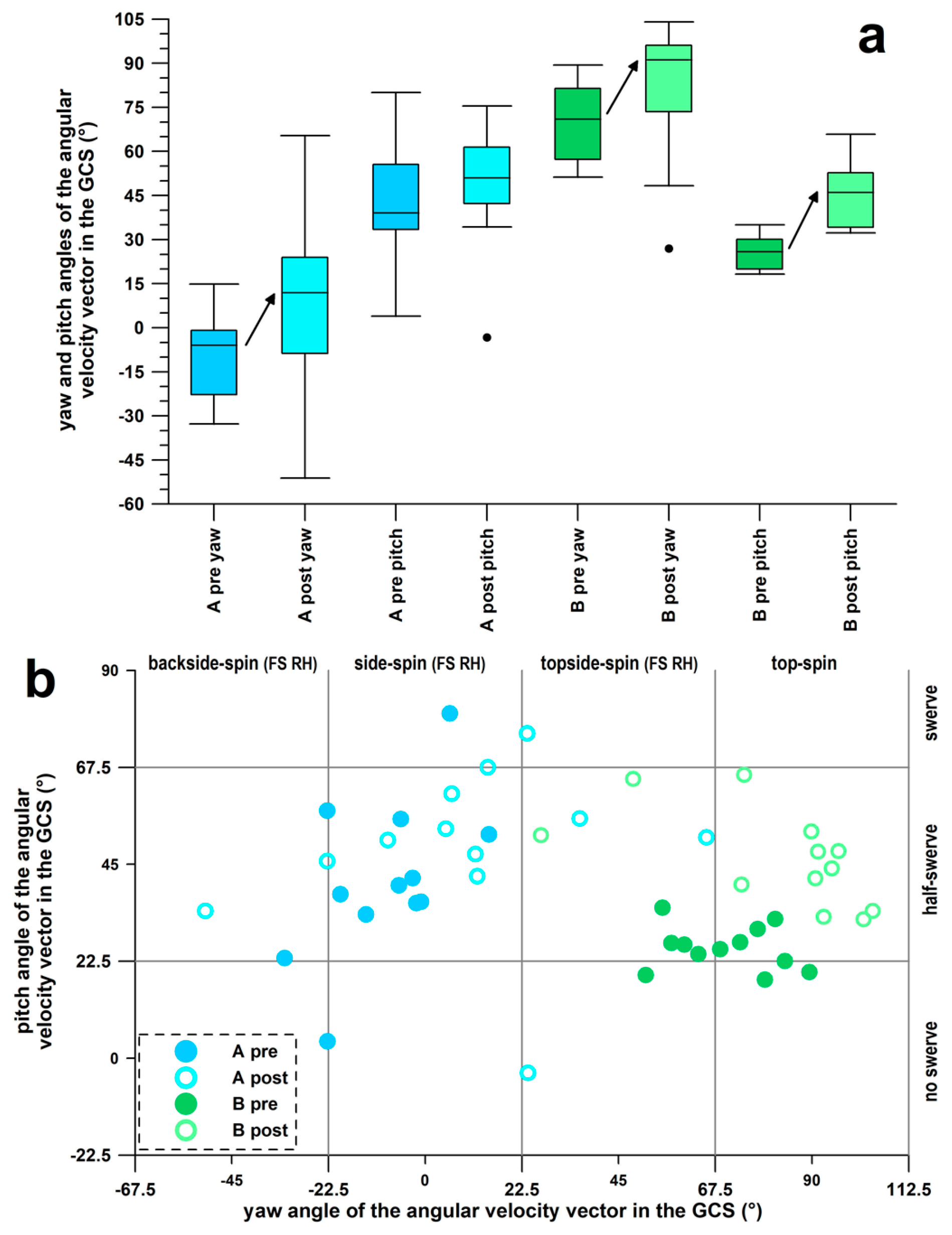

- The delivery type was identified by the smart ball after aligning the BCS with the global coordinate system (GCS; x—forward, direction of the ball’s flight; y—to the left; z—up) [29]. To achieve this alignment, the BCS was continuously rotated about the instantaneous angular velocity ω-vector by the angle φ, i.e., by the magnitude of the instantaneous ω/f, where f is the data sampling frequency (815 Hz). After each completed rotation step, the rotated BCS was rotated back into its original and initial position along with the instantaneous ω-vector [29]. Because the participants were right-handed off-spinners, the yaw (azimuth) and pitch (elevation) angles of the ω-vector in the GCS were both expected to be at 0° ± 22.5°, if the off-spin was a perfect side-spin.

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Legality Assessment of the Bowlers

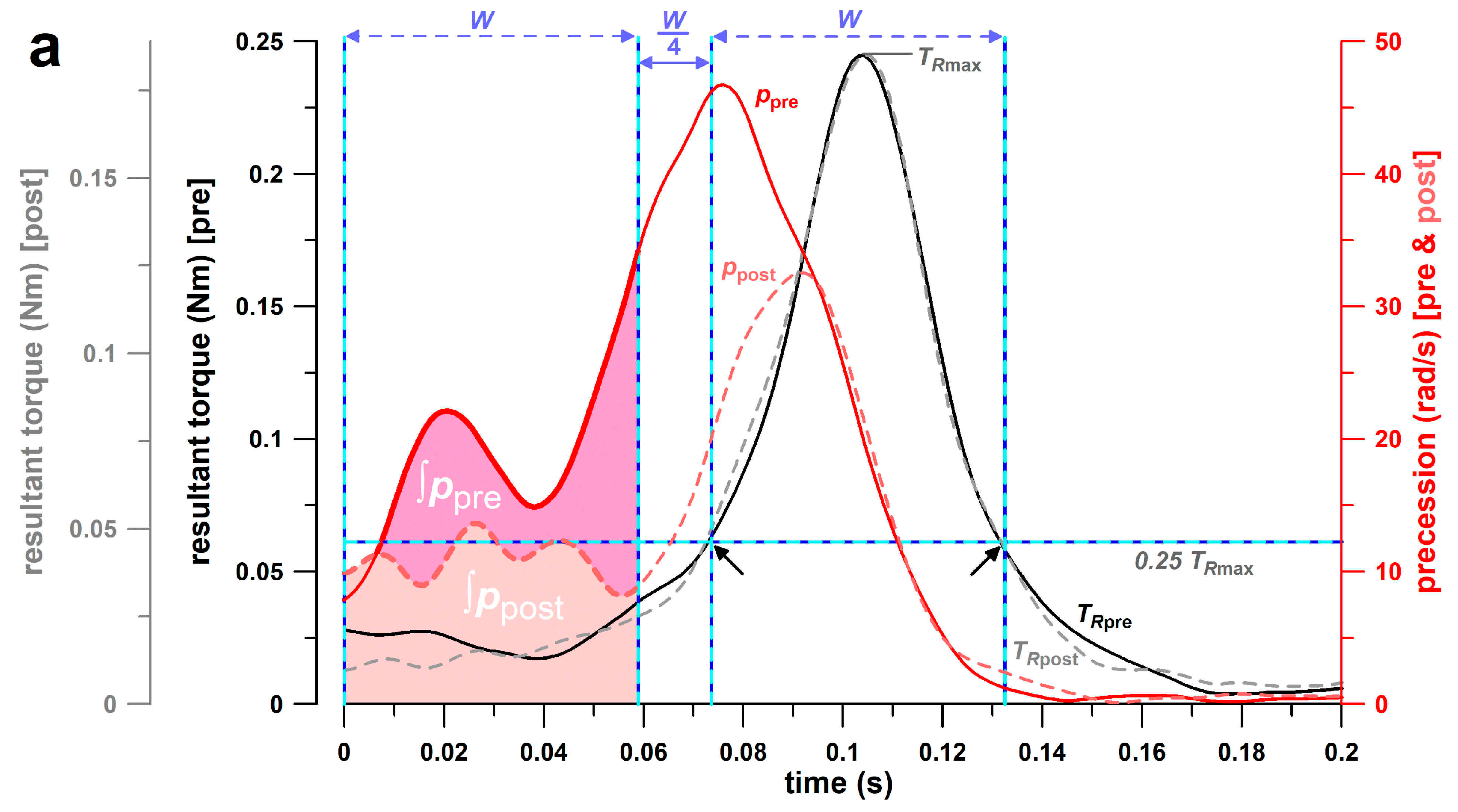

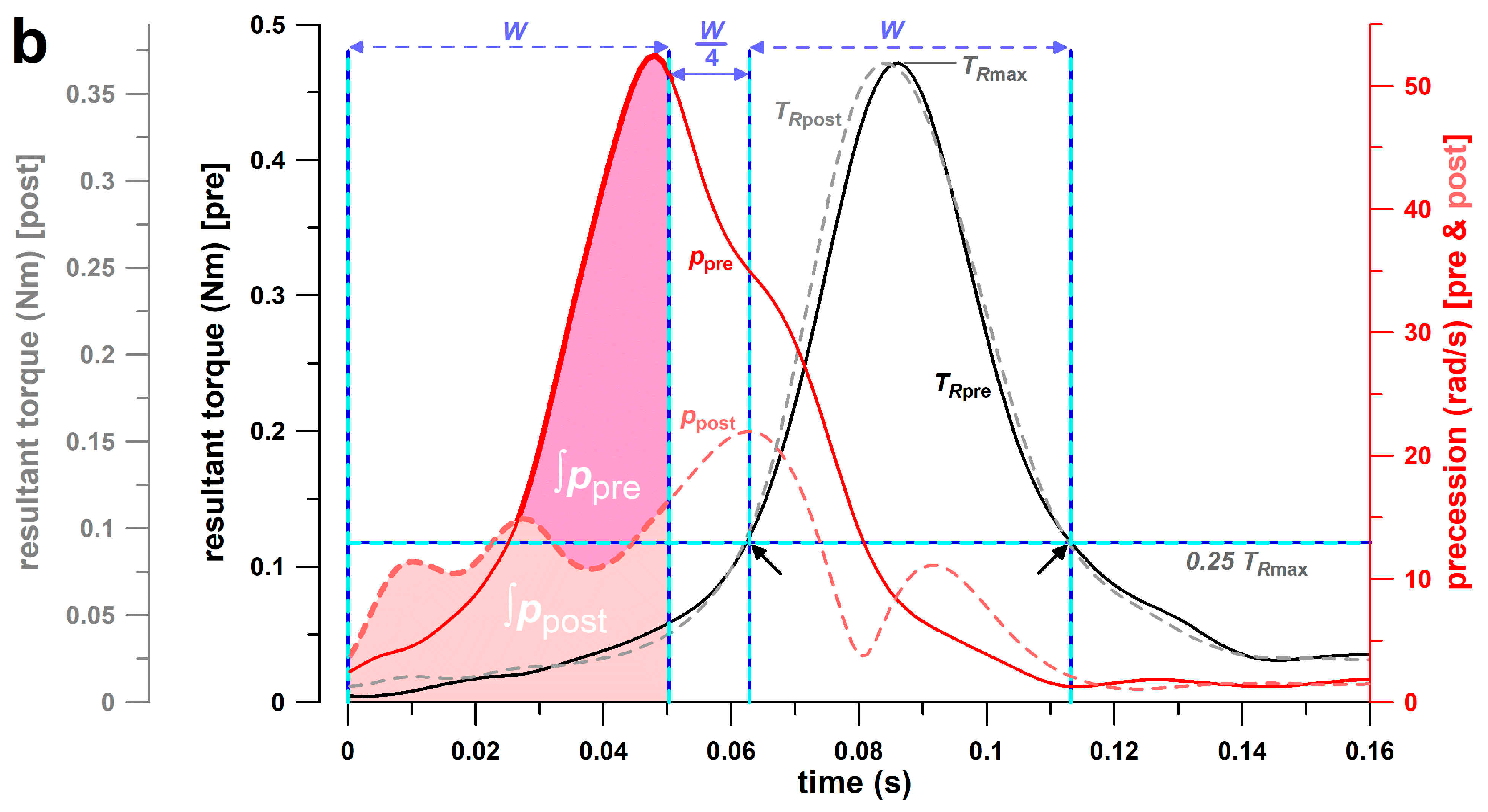

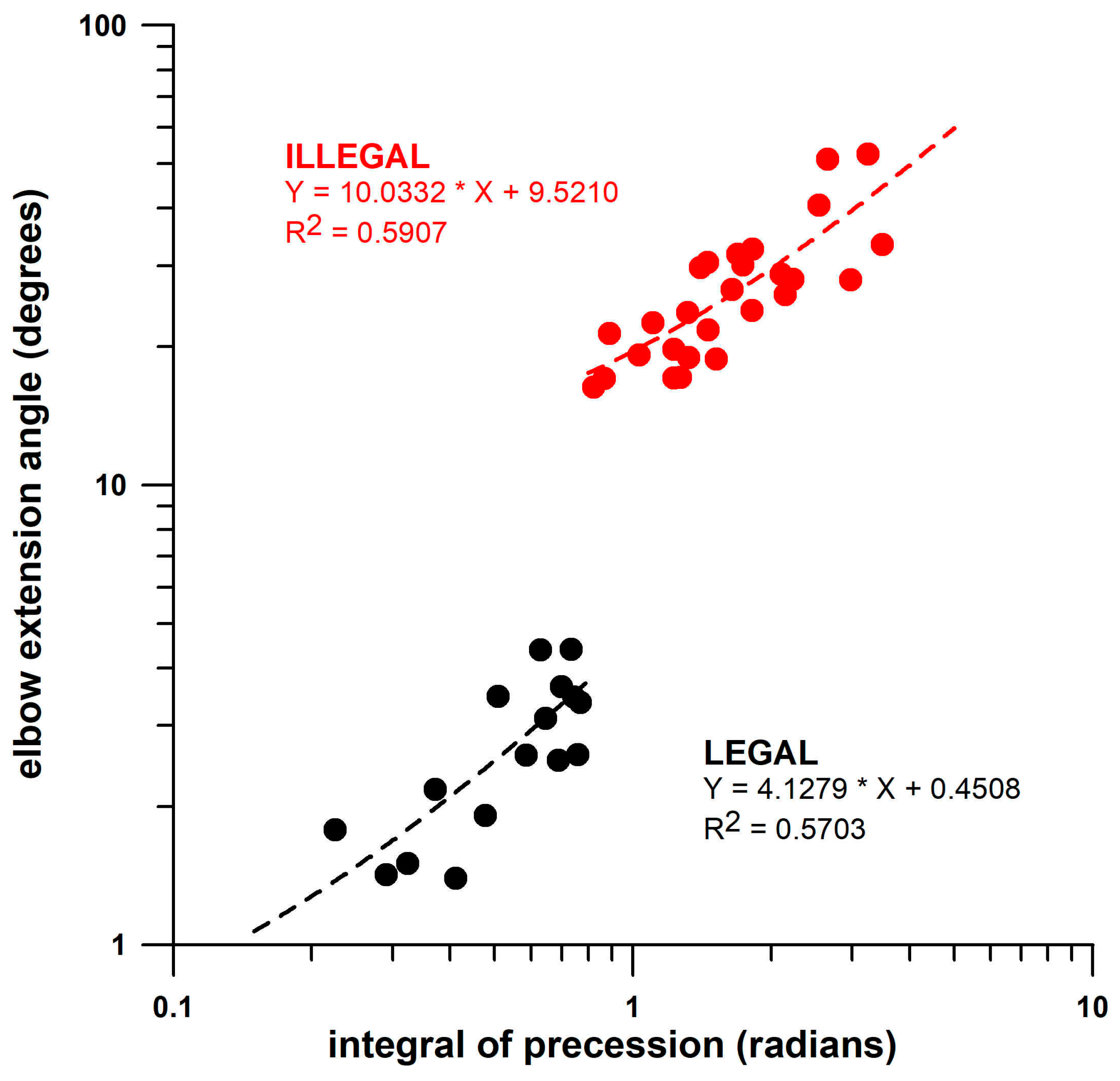

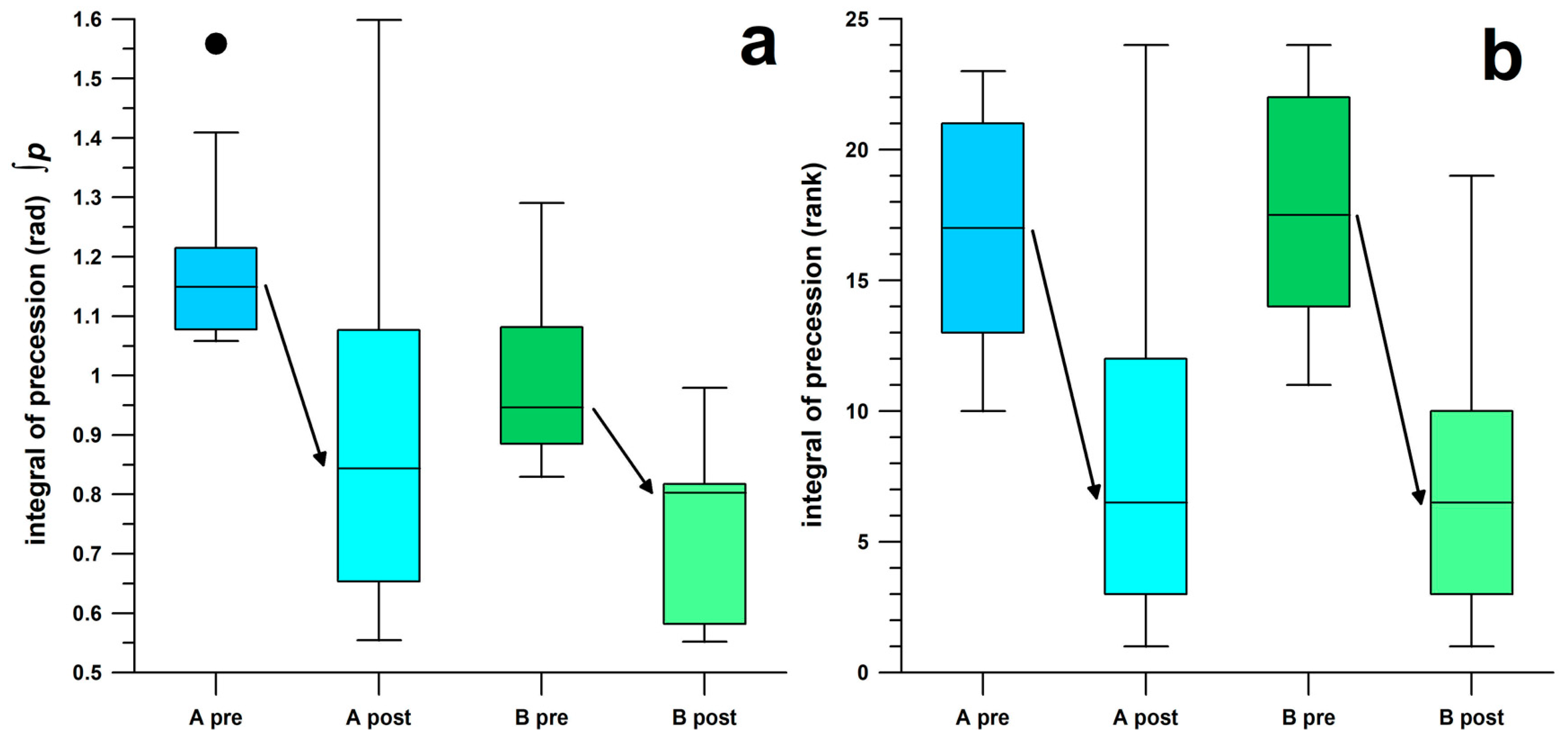

3.2. Integral of the Precession

3.3. Physical and Skill Performance Parameters

3.4. Position of the Centre of Pressure

3.5. Type of Delivery

4. Discussion

- Initial Visual Assessment: Conduct video-based analysis from multiple angles, focusing on the 14 key biomechanical parameters relevant to legality.

- Baseline Smart Ball Testing: Require the bowler to deliver one over (six balls) to establish pre-intervention performance and legality data.

- Intervention and Feedback: Run a technical remediation session (30 min minimum), providing explicit feedback to reduce elbow extension and enhance coordinated forearm supination and wrist flexion.

- Post-Intervention Assessment: Repeat the smart-ball deliveries to evaluate changes in precession and other relevant metrics.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Periodically reassess to ensure retention of the corrected action and long-term legality.

- (1)

- The main limitation of this study is sample size (only two participants), which restricts the statistical power of the analyses and limits the generalisability of the findings. As such, the results should be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, the clear directional changes in elbow extension and smart-ball parameters provide encouraging evidence for the feasibility of the intervention. As focus was on the side effects of the intervention, irrespective of the outcome of the intervention itself, we compared the data of each parameter before and after the intervention with the MWU-test to detect any significant differences for each bowler individually. The focus of this study was not to compare different bowlers based on side effects which we did not know in the first place. If the number of side-effects were scarce and inconsistent between bowlers, a larger sample were justified to present the case of side-effects. Larger trials are needed to confirm these effects and determine whether the observed improvements can be reproduced in a broader population of spin bowlers. Notably, changes were detected not only in the primary target variable (∫p), but also in secondary measures, including the position of the centre of pressure (COP), the yaw angle of the angular velocity vector in the global coordinate system (GCS), and two skill-related parameters: precession and normalised precession. In addition, even with small subject numbers, the smart ball offers a means of validating a coach’s claims that a prescribed technical intervention has indeed led to tangible changes, rather than relying solely on self-report.

- (2)

- Furthermore, since the intervention trials were conducted outdoors, direct measurement of elbow flexion angles was not feasible. Instead, changes in elbow motion were inferred from the smart cricket ball data, as rapid elbow extension during delivery influences the magnitude of the precession integral (∫p). To complement these indirect measurements, each delivery was recorded on a smartphone during and after the intervention. The recordings were reviewed immediately after each delivery by an experienced bowler and cricket coach (REDF). Bowling legality was subsequently evaluated using a newly developed qualitative assessment tool comprising 14 parameters (Table 1 and Table 2).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oslear, D. Wisden’s The Laws of Cricket; Random House Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinands, R.E.; Kersting, U.G. An evaluation of biomechanical measures of bowling action legality in cricket. Sports Biomech. 2007, 6, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K.J.; Alderson, J.A.; Elliott, B.C.; Mills, P.M. The influence of elbow joint kinematics on wrist speed in cricket fast bowling. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 1622–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.N.; Ferdinands, R. The effect of a flexed elbow on bowling speed in cricket. Sports Biomech. 2003, 2, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.N.; Elliott, B.C. Long-axis rotation: The missing link in proximal-to-distal segmental sequencing. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Cricket Council (ICC). ICC Regulations for the Review of Bowlers Reported with Suspected Illegal Bowling Action; International Cricket Council (ICC): Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2018; Available online: https://images.icc-cricket.com/image/upload/prd/ogrrdz3olvinuhtdia2d.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- International Cricket Council (ICC). Illegal Bowling Actions; International Cricket Council (ICC): Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2024; Available online: https://www.icc-cricket.com/about/cricket/rules-and-regulations/illegal-bowling-actions (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Portus, M.R.; Rosemond, C.D.; Rath, D.A. Cricket: Fast bowling arm actions and the illegal delivery law in men’s high performance cricket matches. Sports Biomech. 2006, 5, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felton, P.J.; King, M.A. The effect of elbow hyperextension on ball speed in cricket fast bowling. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aginsky, K.D.; Noakes, T.D. Why it is difficult to detect an illegally bowled cricket delivery with either the naked eye or usual two-dimensional video analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, D.G.; Alderson, J.; Elliott, B.C. An upper limb kinematic model for the examination of cricket bowling: A case study of Mutiah Muralitharan. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.A.; Yeadon, M.R. Quantifying elbow extension and elbow hyperextension in cricket bowling: A case study of Jenny Gunn. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratford, W.; Elliott, B.; Portus, M.; Brown, N.; Alderson, J. Illegal bowling actions contribute to performance in cricket finger-spin bowlers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratford, W.; Alderson, J.; Elliott, B. Illegal bowling actions laws, do they really matter? In Proceedings of the 36th Conference of the International Society of Biomechanics in Sports, Auckland, New Zealand, 10–14 September 2018. ISBS Proceedings Archive 36, article 92. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.A.; Chaaban, C.R.; Padua, D.A. Validation of OpenCap: A low-cost markerless motion capture system for lower-extremity kinematics during return-to-sport tasks. J. Biomech. 2024, 171, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixted, A.; Portus, M.; James, D. Virtual & inertial sensors to detect illegal cricket bowling. Proc. Eng. 2010, 2, 3453–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixted, A.; James, D.; Busch, A.; Portus, M. Wearable sensors for the monitoring of bowling action in cricket. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 12, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixted, A.; Spratford, W.; Davis, M.; Portus, M.; James, D. Wearable sensors for on field near real time detection of illegal bowling actions. In Proceedings of the Conference of Science, Medicine and Coaching in Cricket 2010, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 1–3 June 2010; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Wixted, A.; James, D.; Portus, M. Inertial sensor orientation for cricket bowling monitoring. IEEE Sens. 2011, 2011, 1835–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wixted, A.; Portus, M.; Spratford, W.; James, D. Detection of throwing in cricket using wearable sensors. Sports Technol. 2011, 4, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, S.; Imtiaz, S.; Glazier, P.; Farooq, F.; Jamal, A.; Iqbal, W.; Lee, S. A method for cricket bowling action classification analysis using a system of inertial sensors. In Computational Science and Its Applications; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Murgante, B., Carlini, S.M.M., Torre, C.M., Nguyen, H.-Q., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7971, pp. 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Qaisar, S.; Qamar, A.M. Classification and legality analysis of bowling action in the game of cricket. Data Min. Knowl. Disc. 2017, 31, 1706–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Asawal, M.; Khan, M.J.; Cheema, H.M. A wearable wireless sensor for real time validation of bowling action in cricket. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 12th International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN), Cambridge, MA, USA, 9–12 June 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goonetilleke, R.S. Legality of bowling actions in cricket. Ergonomics 1999, 42, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, F.K.; Smith, R.M.; Subic, A. Determination of spin rate and axes with an instrumented cricket ball. Proc. Eng. 2012, 34, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doljin, B.; Fuss, F.K. Development of a smart cricket ball for advanced performance analysis of bowling. Proc. Techn. 2015, 20, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, F.K.; Doljin, B.; Ferdinands, R.E.D. Mobile computing with a smart cricket ball: Discovery of novel performance parameters and their practical application to performance analysis, advanced profiling, talent identification and training interventions of spin bowlers. Sensors 2021, 21, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, F.K.; Ferdinands, R.E.D.; Beach, A.; Doljin, B. Detection of illegal bowling actions with a smart cricket ball. In Proceedings of the 5th World Congress of Science & Medicine in Cricket, Sydney, Australia, 24–26 March 2015; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Fuss, F.K.; Doljin, B.; Ferdinands, R.E.D. Identification of Spin Bowling Deliveries with a Smart Cricket Ball. Sensors 2024, 24, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S.; Yamako, G.; Totoribe, K.; Sekimoto, T.; Kadowaki, Y.; Tsuruta, K.; Chosa, E. Shadow pitching deviates ball release position: Kinematic analysis in high school baseball pitchers. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maker, R.; Taliep, M.S. The effects of a four weeks combined resistance training programme on cricket bowling velocity. S. Afr. J. Sports Med. 2021, 33, v33i1a9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.B.; Pasquale, M.R.; Laudner, K.G.; Sell, T.C.; Bradley, J.P.; Lephart, S.M. On-the-Field Resistance-Tubing Exercises for Throwers: An Electromyographic Analysis. J. Athl. Train. 2005, 40, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, A.; Petrica, J. Knowledge in motion: A comprehensive review of evidence-based human kinetics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, K.; Takagi, T.; Kubota, H.; Maruyama, T. Multi-body dynamic coupling mechanism for generating throwing arm velocity during baseball pitching. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2017, 54, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirashima, M.; Yamane, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Ohtsuki, T. Kinetic chain of overarm throwing in terms of joint rotations revealed by induced acceleration analysis. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2874–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, A.J.; Ferdinands, R.E.; Sinclair, P.J. The relationship between segmental kinematics and ball spin in Type-2 cricket spin bowling. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, K.; Urabe, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Yokoe, K.; Koshida, S.; Kawamura, M.; Ida, K. The role of shoulder maximum external rotation during throwing for elbow injury prevention in baseball players. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2008, 7, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Crotin, R.L.; Slowik, J.S.; Brewer, G.; Cain, E.L.; Fleisig, G.S. Determinants of biomechanical efficiency in collegiate and professional baseball pitchers. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 3374–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, S.; Yanai, T.; Sakurai, S. Configuration of the shoulder complex during the arm-cocking phase in baseball pitching. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 2445–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritch, J.; Parekh, A.; Labbe, A.; Courseault, J.; Savoie, F.; Longo, U.G.; De Salvatore, S.; Candela, V.; Di Naro, C.; Casciaro, C.; et al. Biomechanics of the Throwing Shoulder. In Orthopaedic Biomechanics in Sports Medicine; Koh, J., Zaffagnini, S., Kuroda, R., Longo, U.G., Amirouche, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Lee, M.; Solomito, M.J.; Merrill, C.; Nissen, C. Lumbar Hyperextension in Baseball Pitching: A Potential Cause of Spondylolysis. J. Appl. Biomech. 2018, 34, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, S.; Yu, B.; Blackburn, J.T.; Padua, D.A.; Li, L.; Myers, J.B. Effect of excessive contralateral trunk tilt on pitching biomechanics and performance in high school baseball pitchers. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 41, 2430–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinands, R.E.D.; Singh, U. Investigating the biomechanical validity of the V-spine angle technique in cricket fast bowling. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 18, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.A.; Worthington, P.J.; Ranson, C.A. Does maximising ball speed in cricket fast bowling necessitate higher ground reaction forces? J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.B.; Aruin, A.S.; Latash, M.L. Velocity-dependent activation of postural muscles in a simple two-joint synergy. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1995, 14, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ackland, D.C.; Pandy, M.G. Shoulder muscle function depends on elbow joint position: An illustration of dynamic coupling in the upper limb. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 1859–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, Y.; Yuine, H.; Kazuki, O.; Tung, W.-L.; Ishii, T. Measurement of wrist flexion and extension torques in different forearm positions. BioMed. Eng. Online 2015, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringer, C.R.; Mansouri, M.; Fisher, L.E.; Collinger, J.L.; Munin, M.C.; Boninger, M.L.; Gaunt, R.A. The effect of wrist posture on extrinsic finger muscle activity during single joint movements. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuss, F.K.; Doljin, B.; Ferdinands, R.E.D. The biomechanics of converting torque into spin rate in spin bowlers analysed with a smart cricket ball. Ind. J. Orthop. 2023, 57, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, P.J.; King, M.A.; Ranson, C.A. Relationships between fast bowling technique and ball release speed in cricket. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, F.K.; Doljin, B.; Ferdinands, R.E.D. Calculation of the Point of Application (Centre of Pressure) of Force and Torque Imparted on a Spherical Object from Gyroscope Sensor Data, Using Sports Balls as Practical Examples. Sensors 2024, 24, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felton, P.J.; Yeadon, M.R.; King, M.A. Optimising the front foot contact phase of the cricket fast bowling action. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 2054–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K.J.; Wells, D.J.; Foster, D.H.; Alderson, J.A. Proximal cueing to reduce elbow extension levels in suspect spin bowlers: A case study. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2018, 13, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.C.; Koshland, G.F. General coordination of shoulder, elbow and wrist dynamics during multi-joint arm movements. Exp. Brain Res. 2002, 142, 63–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, B. Accentuating muscular development through active insufficiency and passive tension. Strength Cond. J. 2002, 24, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, R.; Fleisig, G.; Barrentine, S.; Andrews, J.; Moorman, C. Baseball: Kinematic and Kinetic comparisons between American and Korean professional baseball pitchers. Sports Biomech. 2002, 1, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, F.E. Muscle coordination of movement: A perspective. J. Biomech. 1993, 26, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K.; Kaneoka, K.; Matsunaga, N.; Ikumi, A.; Yamazaki, M.; Yoshii, Y. Effects of forearm rotation on wrist flexor and extensor muscle activities. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, D.A.; Forman, G.N.; Avila-Mireles, E.J.; Mugnosso, M.; Zenzeri, J.; Murphy, B.; Holmes, M.W. Characterizing forearm muscle activity in young adults during dynamic wrist flexion–extension movement using a wrist robot. J. Biomech. 2020, 108, 109908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leech, K.A.; Roemmich, R.T.; Gordon, J.; Reisman, D.S.; Cherry-Allen, K.M. Updates in Motor Learning: Implications for Physical Therapist Practice and Education. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzab250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpeshkar, V.; Mann, D.L.; Spratford, W.; Abernethy, B. The influence of ball-swing on the timing and coordination of a natural interceptive task. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2017, 54, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, F.K.; Doljin, B.; Ferdinands, R.E.D. Effect on Bowling Performance Parameters When Intentionally Increasing the Spin Rate, Analysed with a Smart Cricket Ball. Proceedings 2018, 2, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.J. The use of surface electromyography in biomechanics. J. Appl. Biomech. 1997, 13, 135–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kookaburra. Smart Ball FAQs. 2024. Available online: https://www.kookaburrasport.com.au/cricket/team-kookaburra/innovation/ (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Kumar, A.; Espinosa, H.G.; Worsey, M.; Thiel, D.V. Spin rate measurements in cricket bowling using magnetometers. Proceedings 2020, 49, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assessment Item | Wt | Pre A | Pre A Wt | Pre B | Pre B Wt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive elbow extension during arm-acceleration | 3 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 9 |

| Jerky or whipping motion at release | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Excessive shoulder external rotation | 2 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 |

| Scapular-thoracic motion ± lumbar extension | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Visible elbow flexion at maximal shoulder ER | 3 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| Early shoulder abduction | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Bowling arm above vertical at release | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Release point significantly ahead of front foot | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Minimal trunk flexion at release | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Minimal “V-angle” (trunk–front thigh) | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Front-on alignment at back foot contact | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Excessive lateral bending ± shoulder rotation | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Open stride angle ± open foot position | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Stride length < 1.2 × shoulder width (short) | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Total Score (sum) | 76 | 53 |

| Assessment Item | Wt | Post-A | Post-A Wt | Post-B | Post-B Wt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive elbow extension during arm-acceleration | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Jerky or whipping motion at release | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Excessive shoulder external rotation | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Scapular-thoracic motion ± lumbar extension | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Visible elbow flexion at maximal shoulder ER | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Early shoulder abduction | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bowling arm above vertical at release | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Release point significantly ahead of front foot | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Minimal trunk flexion at release | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Minimal “V-angle” (trunk–front thigh) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Front-on alignment at back foot contact | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Excessive lateral bending ± shoulder rotation | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Open stride angle ± open foot position | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Stride length < 1.2 × shoulder width | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total Score (sum) | 20 | 11 |

| ∫p (rad) | Δt = W (s) | ∫p (rad) | Δt = W (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant A | Participant B | |||

| med-pre | 1.150 | 0.061 | 0.946 | 0.050 |

| med-post | 0.844 | 0.059 | 0.803 | 0.050 |

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.285 | <0.001 | 0.582 |

| r | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.14 |

| effect | large | medium | large | small |

| trend | ↑ | ⊥ | ↑ | ⊥ |

| ωmax (rad/s) | pmax (rad/s) | pn_max (°) | TR_max (Nm) | Ts_max (Nm) | Tp_max (Nm) | αmax (rad/s2) | Pmax (W) | η (%) | α/ω (s−1) | ω/TR_max | Ts_max/Tp_max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| participant A | ||||||||||||

| med-pre | 127.7 | 47.9 | 100.3 | 0.223 | 0.204 | 0.092 | 2629 | 15.6 | 65.4 | 21.6 | 87.9 | 2.15 |

| med-post | 114.3 | 35.6 | 75.7 | 0.198 | 0.184 | 0.098 | 2365 | 12.7 | 65.5 | 20.6 | 88.2 | 1.80 |

| p-value | 0.040 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.054 | 0.047 | 0.285 | 0.047 | 0.060 | 0.795 | 0.069 | 0.435 | 0.004 |

| r | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.69 |

| effect | large | large | large | large | large | medium | large | large | very small | large | small | large |

| trend | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ⊥ | ↓ | ⊥ | ↓ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ↓(↑) |

| participant B | ||||||||||||

| med-pre | 191.2 | 48.8 | 131.3 | 0.378 | 0.374 | 0.080 | 4813 | 39.2 | 75.9 | 25.1 | 80.4 | 4.75 |

| med-post | 195.0 | 23.1 | 73.5 | 0.362 | 0.359 | 0.102 | 4617 | 38.4 | 77.5 | 23.4 | 86.6 | 3.65 |

| p-val | 0.542 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.215 | 0.112 | 0.624 | 0.099 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.215 |

| r | 0.15 | 1 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.31 |

| effect | small | large | large | large | large | medium | large | small | large | large | large | medium |

| trend | ⊥ | ↑ | ↑ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ⊥ | ↑ | ↑ | ⊥ |

| COPx (r = 10) | COPy (r = 10) | COPz (r = 10) | COPx (r = 10) | COPy (r = 10) | COPz (r = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant A | Participant B | |||||

| med-pre | −7.22 | 1.70 | 6.64 | −7.71 | −3.60 | 3.27 |

| med-post | −4.84 | −3.30 | 7.76 | −1.91 | −8.37 | 4.74 |

| p-val | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.016 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| r | 0.86 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.63 |

| effect | large | large | large | large | large | large |

| Yaw Angle (°) | Pitch Angle (°) | Yaw Angle (°) | Pitch Angle (°) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant A | Participant B | |||

| med-pre | −5.93 | 39.09 | 70.94 | 25.88 |

| med-post | 11.91 | 50.97 | 91.08 | 46.03 |

| p-val | 0.035 | 0.194 | 0.030 | <0.001 |

| r | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.94 |

| effect | large | medium | large | large |

| type of delivery | finger-spin side-spin | half-swerve | finger-spin top-spin | half-swerve |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ferdinands, R.E.D.; Doljin, B.; Fuss, F.K. Assessment and Measurement of the Side-Effects of an Evidence-Based Intervention with an Advanced Smart Cricket Ball Exemplified by a Case Report on Correcting Illegal Bowling Action. Sensors 2026, 26, 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010299

Ferdinands RED, Doljin B, Fuss FK. Assessment and Measurement of the Side-Effects of an Evidence-Based Intervention with an Advanced Smart Cricket Ball Exemplified by a Case Report on Correcting Illegal Bowling Action. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):299. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010299

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerdinands, René E. D., Batdelger Doljin, and Franz Konstantin Fuss. 2026. "Assessment and Measurement of the Side-Effects of an Evidence-Based Intervention with an Advanced Smart Cricket Ball Exemplified by a Case Report on Correcting Illegal Bowling Action" Sensors 26, no. 1: 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010299

APA StyleFerdinands, R. E. D., Doljin, B., & Fuss, F. K. (2026). Assessment and Measurement of the Side-Effects of an Evidence-Based Intervention with an Advanced Smart Cricket Ball Exemplified by a Case Report on Correcting Illegal Bowling Action. Sensors, 26(1), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010299