4.1. Evolution Characteristics of Typical Time-Domain Signals of Cement Paste

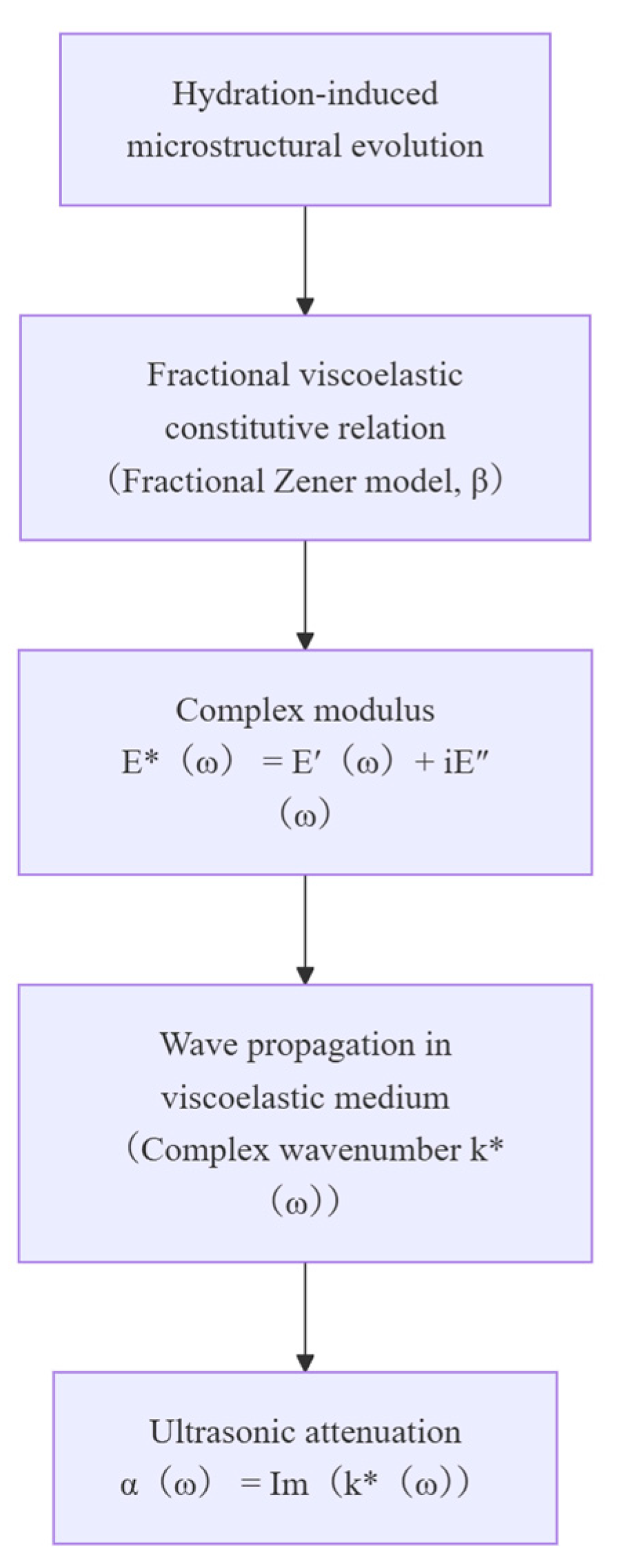

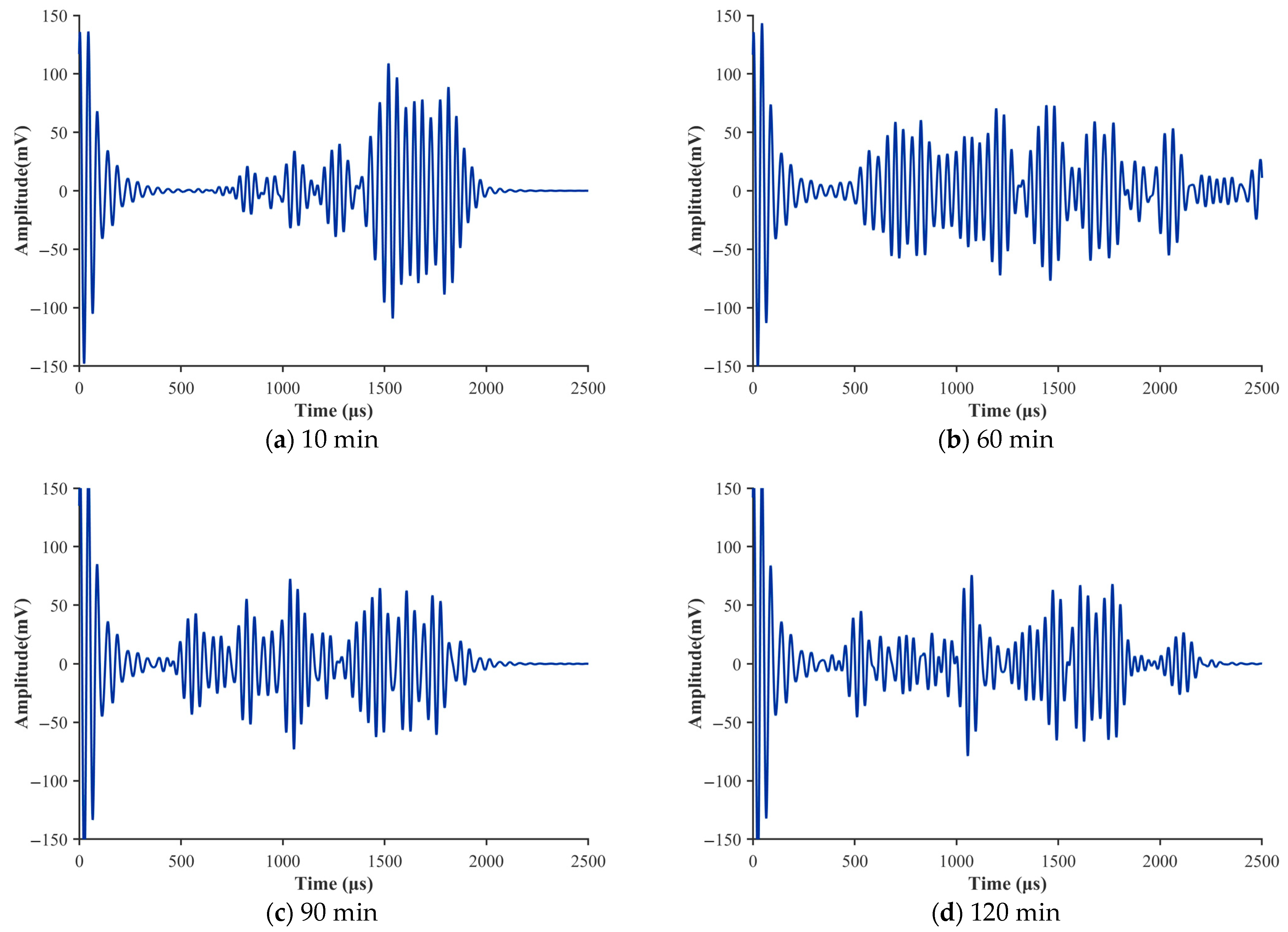

As shown in

Figure 6, taking the ultrasonic signal of cement paste with a water–cement ratio of 0.40 as an example, the time-domain responses at four key moments—10 min, 60 min, 90 min, and 120 min—were comparatively analyzed. At 10 min (a), the signal exhibits characteristics typical of a viscous-fluid-dominated state. The overall amplitude remains relatively high, but the envelope decays extremely rapidly, with oscillations vanishing within a very short duration and the waveform appearing irregular. This indicates that, during the early stage of setting, the dispersed cement particles are separated by free water, and the pronounced viscous dissipation causes ultrasonic energy to be quickly attenuated during propagation. At this moment, the material possesses very low structural strength, and its mechanical behavior closely resembles that of a Newtonian fluid. In terms of the fractional Zener model, this corresponds to a fractional order

approaching zero, meaning that the constitutive response is dominated by viscous behavior.

As hydration progresses to 60 min (b) and 90 min (c), the time-domain signals exhibit clear transitional characteristics. Compared with the 10 min response, the most notable change is the increased persistence of oscillations. Beyond 500 μs, multiple cycles of regular, continuous high-frequency oscillations become visible. Although the peak amplitude decreases, the envelope attenuation rate is substantially reduced.

This transformation signifies fundamental microstructural evolution within the paste: hydration products (C–S–H gels) form progressively and interconnect to establish an initial three-dimensional flocculated network. This network enhances the continuity of the medium and strengthens its elastic response. Consequently, the ultrasonic energy-loss mechanism shifts from purely viscous dissipation toward viscoelastic damping, with elastic wave-propagation characteristics becoming increasingly pronounced.

In terms of fractional-order theory, this evolution is reflected by the gradual increase in the fractional order toward 1, indicating that the material’s “memory” and elastic contribution are continuously strengthened, and the constitutive behavior transitions from a fractional derivative toward an integer-order form.

By 120 min (d), the time-domain signal has evolved to exhibit propagation characteristics dominated by an elastic solid. The signal amplitude stabilizes at a relatively low level, and the waveform displays highly regular, continuous high-frequency oscillations, with only minimal attenuation throughout the entire observation window. This indicates that a dense and rigid spatial network structure has formed within the paste, where particles are interconnected through strong bonding forces.

In such a medium, ultrasonic energy loss arises primarily from elastic scattering caused by microstructural inhomogeneities (e.g., unhydrated particles, microvoids) rather than viscous friction. This stage corresponds to a further increase in the fractional order in the fractional model, reflecting the strengthening of elastic behavior and the near-solid-like mechanical response of the material.

4.2. Verification of the Fractional Model and Analysis of Attenuation Characteristics

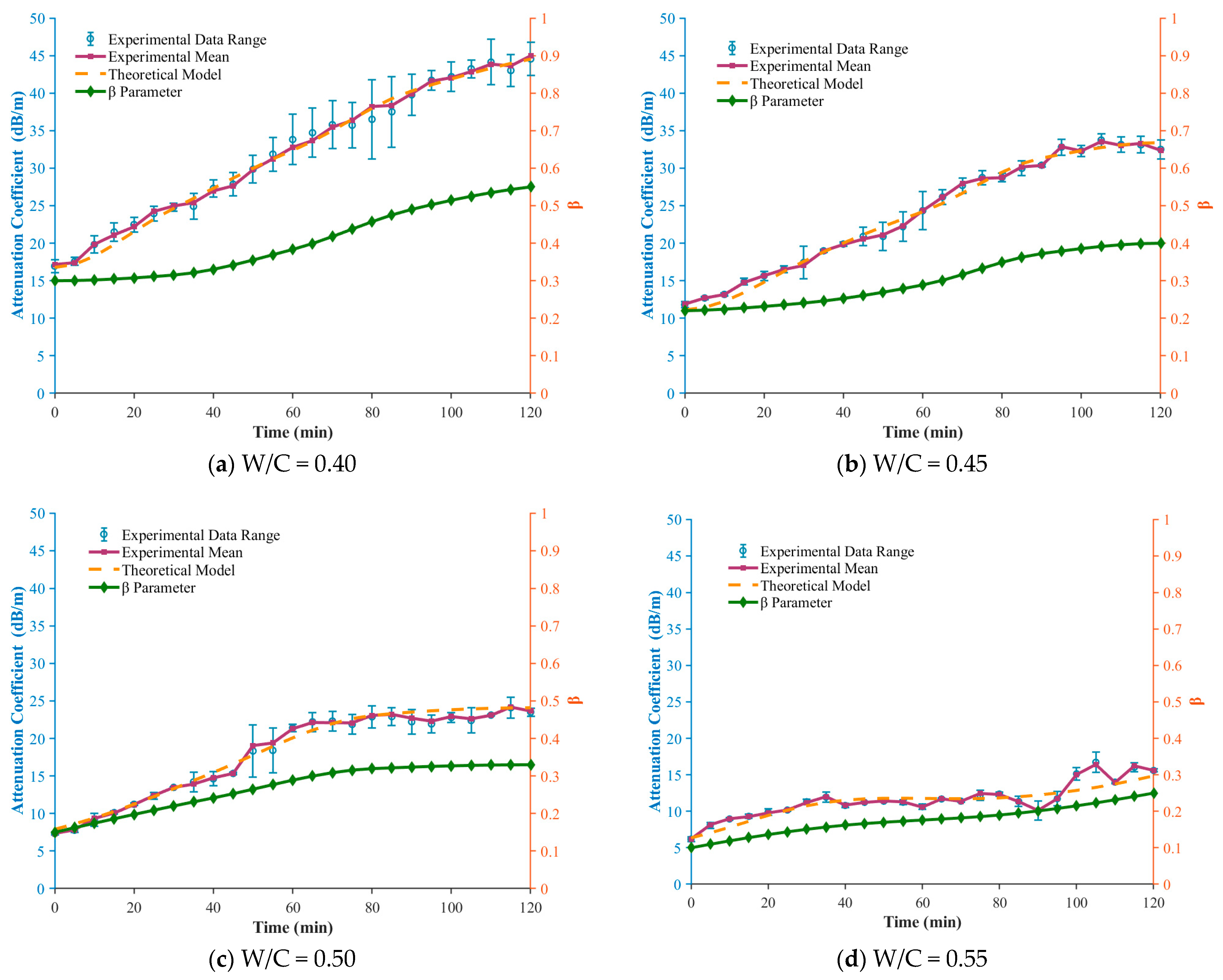

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed fractional Zener model in describing ultrasonic attenuation during the setting of cement paste, this section systematically compares experimental measurements with model predictions for water–cement ratios (W/C) of 0.40, 0.45, 0.50, and 0.55.

Figure 7 illustrate the evolution of the attenuation coefficient

over time (0–120 min) for each water–cement ratio. Each figure presents the experimental mean value, the fluctuation range of the measurements, the theoretical prediction curve, and the corresponding evolution of the fractional order

, which serves as a key parameter in the model.

As shown in the figures, for all water–cement ratios, the experimentally measured attenuation coefficients (blue circles) exhibit a variation trend that is highly consistent with the theoretical predictions based on the fractional model (Equation (22), red squares). Both curves increase monotonically with setting time, which corroborates the earlier time-domain signal analysis: as hydration products accumulate and the flocculated network develops, the dominant attenuation mechanism transitions from early-stage viscous dissipation to later-stage elastic scattering, resulting in a continuous increase in the macroscopic attenuation coefficient .

To quantitatively assess the prediction accuracy of the model, the relative error (RE) between the theoretical predictions and the experimental mean values was calculated over the entire setting process. The results show that the model performs well across all water–cement ratios, although the prediction accuracy varies:

W/C = 0.40 (a): The average relative error is 1.85%, with the maximum error (~7.96%) occurring at the early stage. This indicates that for denser pastes with lower water–cement ratios, the fractional model can capture the attenuation characteristics with very high precision.

W/C = 0.45 (b): The average relative error is 3.33%. The strong agreement between the predicted curve and the experimental mean further confirms the robustness of the model.

W/C = 0.50 (c): The average relative error is 3.35%. Although the fluctuation range of the experimental data (grey region) is larger—suggesting slightly poorer microstructural uniformity at this water–cement ratio—the model still effectively tracks the overall trend.

W/C = 0.55 (d): The average relative error is 7.11%, the highest among all groups. This suggests that at higher water–cement ratios, the greater amount of free water leads to more complex rheological behavior, introducing certain limitations to the model’s predictive capability.

As the key parameter of the proposed model, the fractional order provides a unique perspective on the microstructural evolution of cement paste. The temporal variation curves (green dash–dot lines) in all four figures exhibit a consistent trend: starts from a relatively low value (0.1–0.3) in the early stage of setting and increases approximately linearly as hydration progresses, reaching the range of 0.33–0.55 at 120 min.

At the beginning of setting, represents an ideal viscous-fluid response. In the experiments, the initial values are greater than zero but far below one, indicating that although the fresh paste is dominated by viscous behavior, it already exhibits a certain degree of “memory” behavior—distinct from Newtonian fluids—which reflects the presence of an initial flocculated microstructure.

The monotonic increase of directly captures the continuous formation and strengthening of the internal three-dimensional network. As hydration products such as C–S–H gel progressively interweave and interconnect, the solid-like (elastic) nature of the material increases, while the fluid-like (viscous) contribution diminishes. The inherent long-memory effect of fractional derivatives naturally describes this history-dependent microstructural reconstruction process.

Ultimately, the trend corresponds to the ideal Hookean elastic solid. Since does not reach 1 by the end of the 120 min observation window, this indicates that hydration remains incomplete and the microstructure is still evolving, with the material exhibiting characteristics of a typical viscoelastic solid.

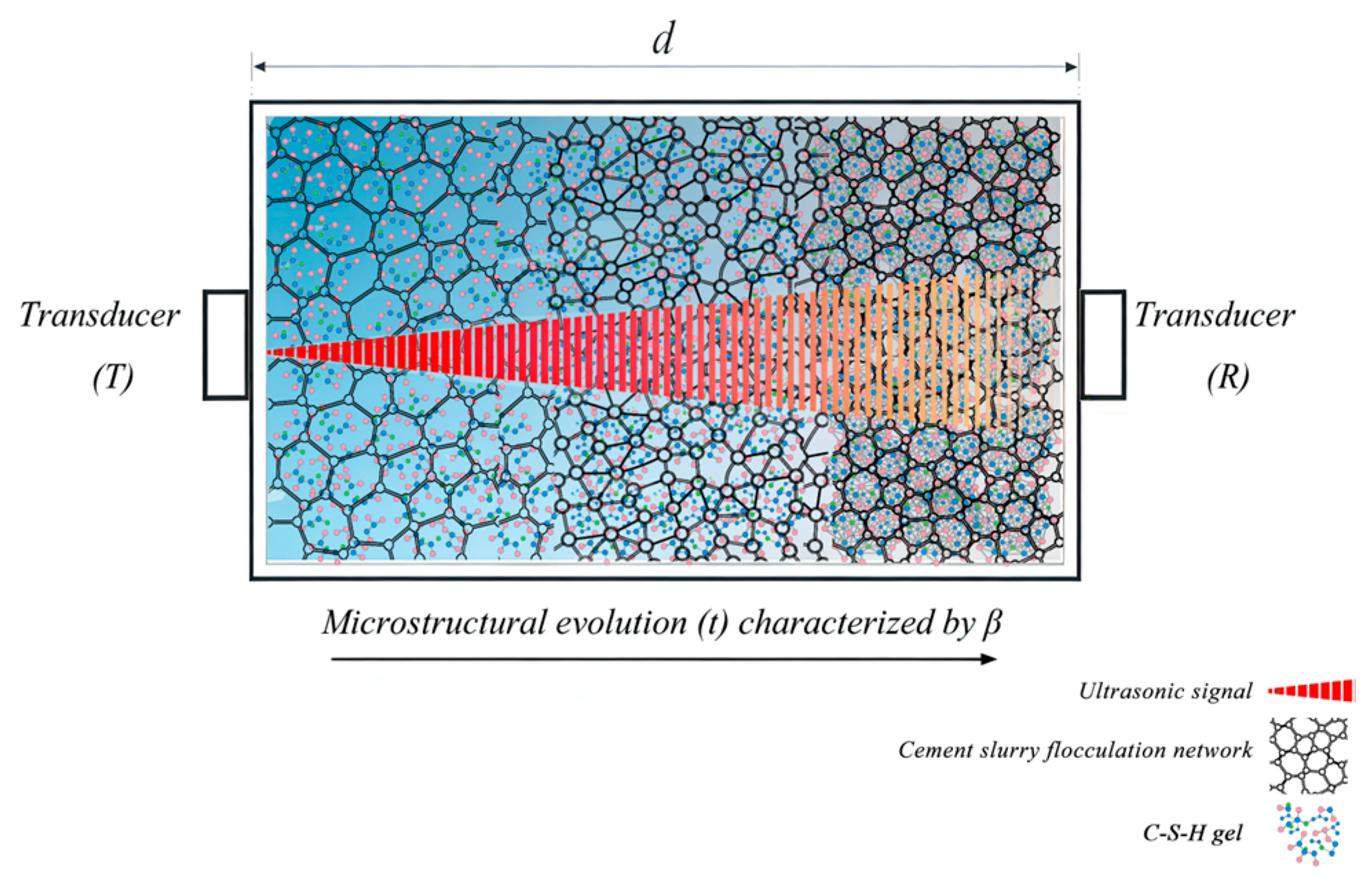

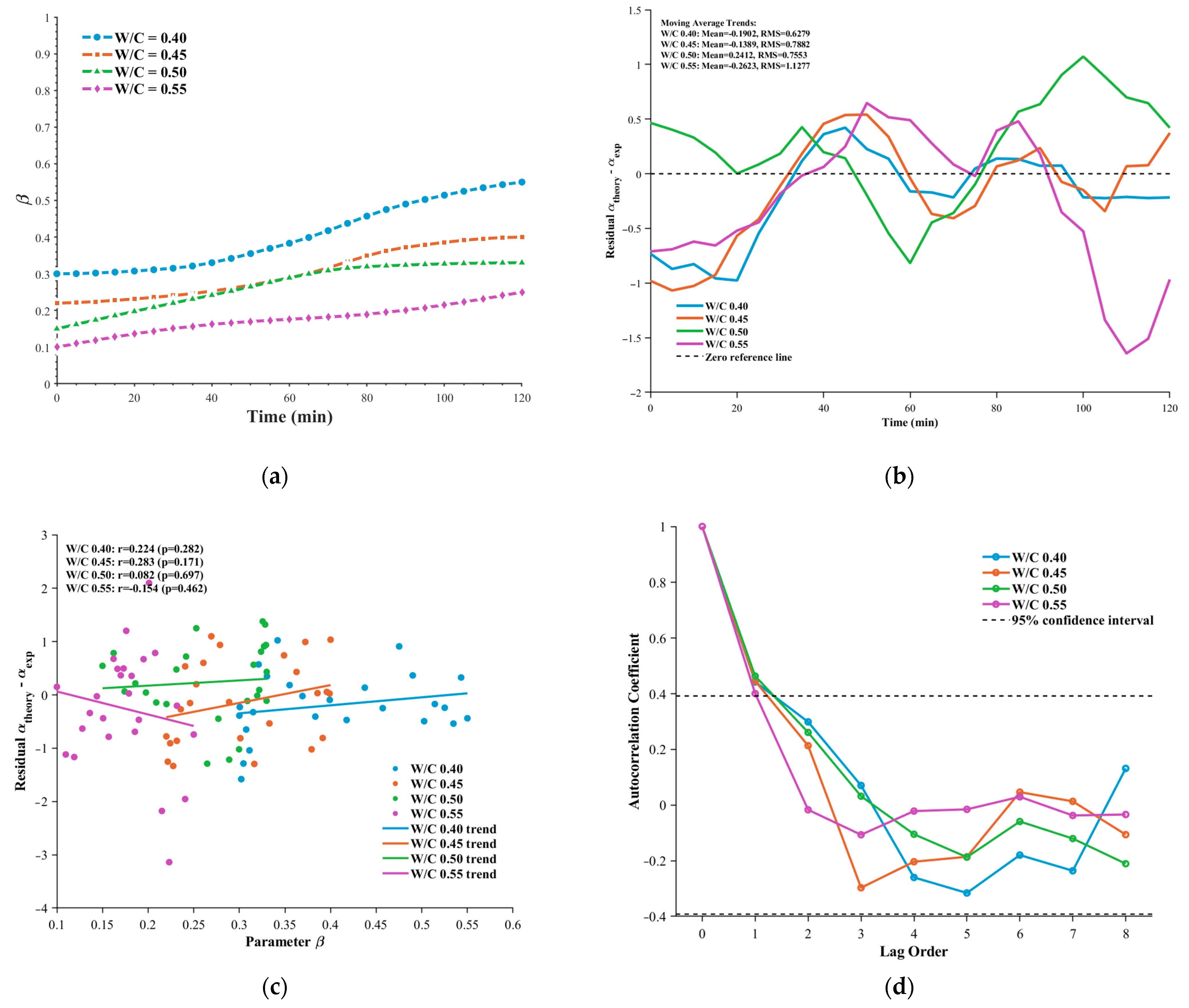

As shown in

Figure 8a, for the same setting time, a higher water–cement ratio corresponds to a lower value of

. For example, at 120 min,

for W/C = 0.40, whereas

for W/C = 0.55. This quantitative relationship indicates that increasing the water–cement ratio dilutes the concentration of cement particles and slows down the formation rate of the flocculated network. Consequently, the paste exhibits stronger macroscopic fluidity (i.e., lower elasticity), which is fully consistent with traditional rheological understanding.

Figure 8b presents the temporal evolution of the residuals (

) between the model predictions and the experimental measurements. For all water–cement ratios, the mean residuals remain very close to zero (ranging from −0.26 to 0.24), indicating that the model predictions are essentially unbiased. In addition, the residual sequences fluctuate randomly around zero throughout the entire setting period, with no observable systematic trends, and the fluctuation magnitude is limited (root-mean-square error RMS between 0.63 and 1.13). These characteristics collectively demonstrate that the fractional model achieves high predictive accuracy for the attenuation coefficients of cement pastes across different water–cement ratios.

To further examine whether the model exhibits systematic bias,

Figure 8c analyzes the relationship between the model residuals and the intrinsic parameter

. The scatter plots show that the residuals are randomly distributed around the zero line, and the trend lines for all water–cement ratios are nearly horizontal. Correlation analysis indicates that the absolute values of the correlation coefficients (r) are all below 0.3, and the corresponding (

p)-values are much greater than the 0.05 significance threshold. This confirms that no statistically significant correlation exists between the residuals and the value of

. In other words, the prediction deviations of the model are random across different structural states (represented by different

values), rather than arising from any structural deficiency of the model itself.

Finally, autocorrelation analysis of the residual sequences (

Figure 8d) shows that, for all cases, the autocorrelation coefficients decay and stabilize within the 95% confidence interval after lag 2. This indicates that the residuals exhibit no significant autocorrelation beyond the second lag and therefore satisfy the key characteristics of white noise. This result confirms that the fractional model has successfully captured the essential temporal dependencies in the evolution of the attenuation coefficient, with no important systematic time information left unmodeled.

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 indicate that the evolution of the fractional parameter

is generally monotonic but not strictly linear over time. Instead,

exhibits stage-dependent trends that correspond well to the classical hydration process. During the dormant period,

increases slowly, reflecting a predominantly viscous response of the fresh cement paste. In the acceleration stage, a more pronounced increase in

is observed, associated with rapid formation of hydration products and the development of a load-bearing microstructure. As hydration progresses toward rigidity and early hardening, the growth rate of

gradually decreases, indicating a transition toward a more elastic-dominated viscoelastic state.

For mixtures with higher water–cement ratios, the prediction error of ultrasonic attenuation becomes more pronounced. This behavior can be attributed to increased variability associated with a higher free-water content, which enhances scattering, local heterogeneity, and transient coupling effects during early hydration. In such systems, the ultrasonic attenuation is more sensitive to small fluctuations in microstructure and pore water distribution, leading to increased dispersion in the measured signals. Consequently, deviations between predicted and measured attenuation are more noticeable at higher water–cement ratios, particularly at very early ages.

The sensitivity of to measurement noise and algorithmic adjustments was examined by analyzing its temporal stability and repeatability across repeated measurements. Although small fluctuations in may arise from signal noise or envelope fitting procedures, the identified evolution is primarily governed by long-term trends rather than pointwise variations. Since is extracted through baseline-referenced attenuation trends, its estimation is inherently less sensitive to random noise compared with instantaneous ultrasonic indicators. The observed smooth evolution of across hydration stages suggests that the parameter predominantly reflects underlying physical dynamics rather than numerical artifacts.

In some cases, approaches a quasi-stationary zone or plateau at more advanced hydration ages. This behavior does not indicate a loss of sensitivity but rather reflects the stabilization of the viscoelastic microstructure once the primary hydration reactions have largely completed. At this stage, the cement paste exhibits a relatively stable elastic-dominated response, and further changes in intrinsic energy dissipation mechanisms become less pronounced. Therefore, the plateau of can be interpreted as a signature of early-age mechanical stabilization rather than a limitation of the sensing framework.

The practical use of and as hydration indicators is subject to several limitations. First, both parameters rely on baseline-referenced measurements and are therefore most effective during early-age hydration, when material evolution is monotonic and well controlled. Second, reflects cumulative attenuation effects and may be influenced by experimental conditions such as coupling and boundary effects, whereas is a model-derived parameter whose interpretation depends on the validity of the assumed viscoelastic framework. Consequently, and should be interpreted as complementary indicators of hydration progression rather than absolute material properties.

The proposed method exhibits limited sensitivity to random measurement noise, as both and are extracted from envelope-based attenuation trends and evaluated through temporal evolution rather than instantaneous values. Temperature fluctuations primarily affect absolute signal amplitudes and wave speeds; however, their influence on is mitigated by baseline referencing and trend-based interpretation. Transducer misalignment and coupling conditions may affect absolute attenuation levels, but their impact on the temporal evolution of is expected to be secondary, particularly when consistent sensor geometry and fixed excitation–reception paths are maintained.

While the present study focuses on early-age hydration, the proposed framework is, in principle, capable of detecting non-monotonic phenomena such as micro-cracking or segregation. Such processes are expected to introduce abrupt or irreversible changes in attenuation behavior and in the evolution of , in contrast to the smooth and monotonic trends observed during hydration. However, distinguishing these mechanisms from environmental or operational effects would require auxiliary sensing information and extended validation, which is beyond the scope of the current work.

The current formulation and experimental validation are limited to cement paste and therefore represent a matrix-level framework. In fiber-reinforced or highly heterogeneous concrete, additional effects such as multi-scattering, anisotropy, and guided-wave propagation are expected to influence ultrasonic attenuation. While the fractional viscoelastic model remains applicable at the effective-medium level, its extension to such systems would require incorporating appropriate homogenization or multi-scattering models. This represents an important direction for future work.

The fractional-order framework is inherently frequency-dependent and can be naturally extended to other ultrasonic frequencies or multi-frequency excitation schemes. Since the fractional constitutive model describes viscoelastic behavior across a broad frequency range, can be identified using different excitation frequencies, provided that the corresponding attenuation data are available. Multi-frequency measurements may further enhance parameter identifiability and robustness by constraining the inversion process and enabling frequency-domain consistency checks.

Taken together, the validation results for all four water–cement ratios demonstrate that the proposed fractional model not only provides high-accuracy predictions of ultrasonic attenuation during the setting of cement paste but also yields residuals that are genuinely random. This verifies the robustness and completeness of the model. Overall, the evolution of provides a physically consistent and stage-sensitive indicator of hydration progression, offering a robust descriptor of early-age material state that complements conventional ultrasonic attenuation analysis.

4.3. Comparative Analysis Between the Fractional Model and Other Viscoelastic Theories

After validating the fractional model developed in this study, we compare it with three representative viscoelastic models: the DFL (Decoupled Fractional Laplacian) model, the Fractal Modification model, and the classical Kelvin–Voigt model [

30,

31]. All of these models aim to describe wave propagation in viscoelastic media, yet they differ substantially in theoretical foundations and application focus.

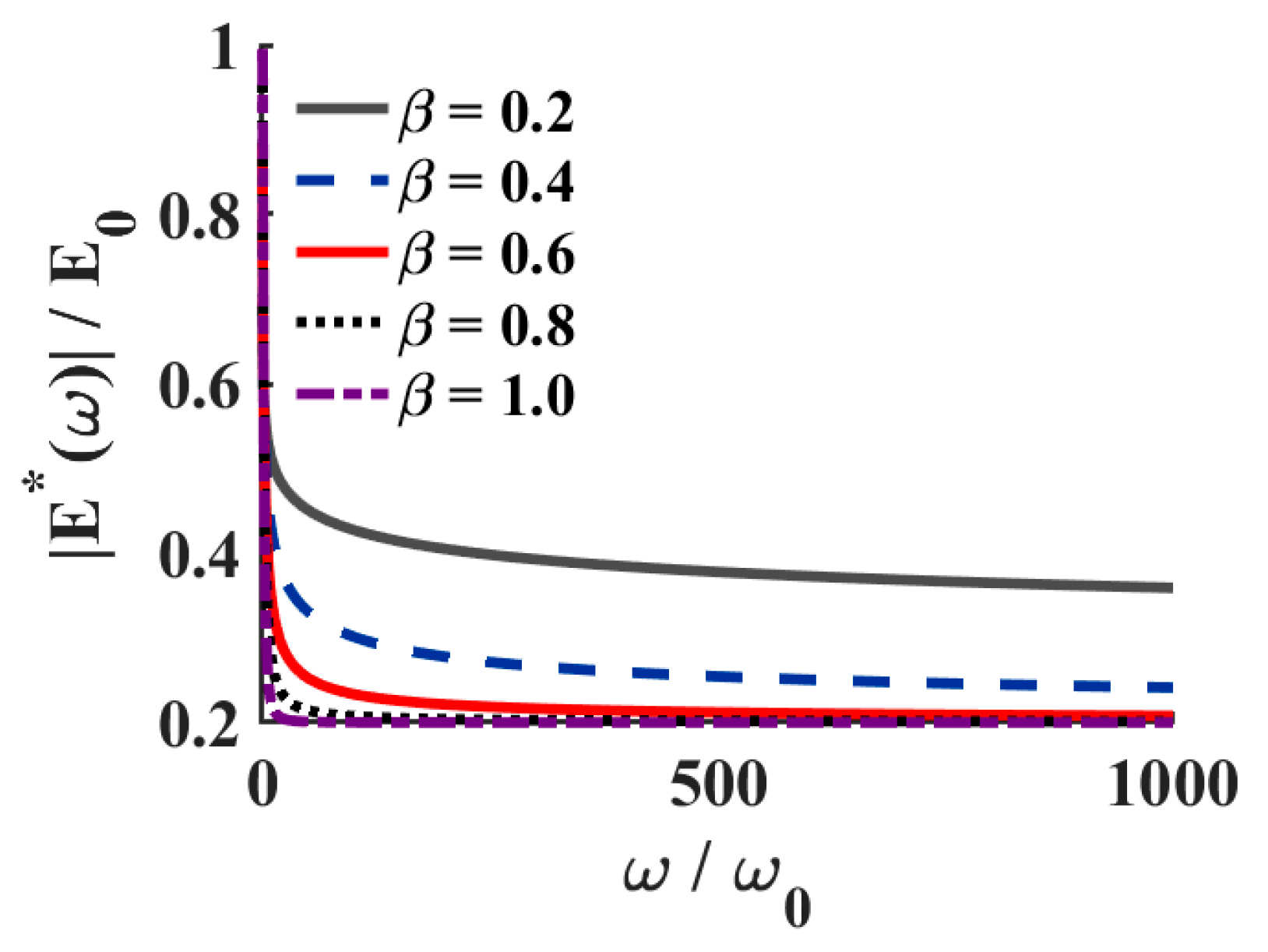

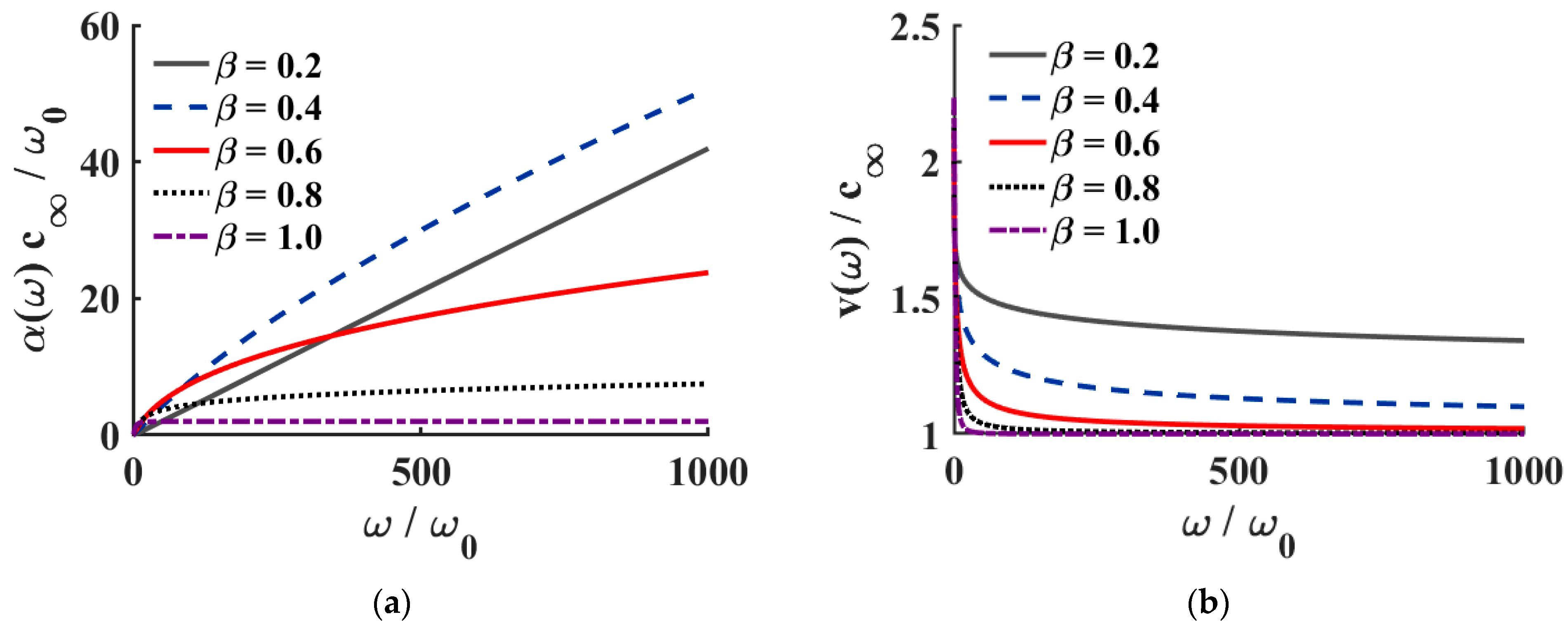

The proposed fractional model introduces the fractional derivative order , which effectively captures the memory effects and gradual microstructural evolution occurring during the setting of cement paste. Its frequency-domain complex-modulus formulation provides a direct and intuitive representation of viscoelastic response.

The DFL model employs a decoupled fractional Laplacian operator and is particularly efficient for handling anisotropic attenuation in highly heterogeneous media. Its wavefield simulations allow clear separation of amplitude decay and phase dispersion.

The Fractal Modification model is derived from fractal theory, using parameters such as or as scaling variables. It is especially suited for mineral slurries where particle irregularity and clustering are prominent.

In contrast, the Kelvin–Voigt model—an integer-order viscoelastic representation composed of a parallel spring–dashpot system—is simple and intuitive but cannot adequately capture frequency-independent attenuation or the dynamic microstructural evolution characteristic of cement paste during hydration.

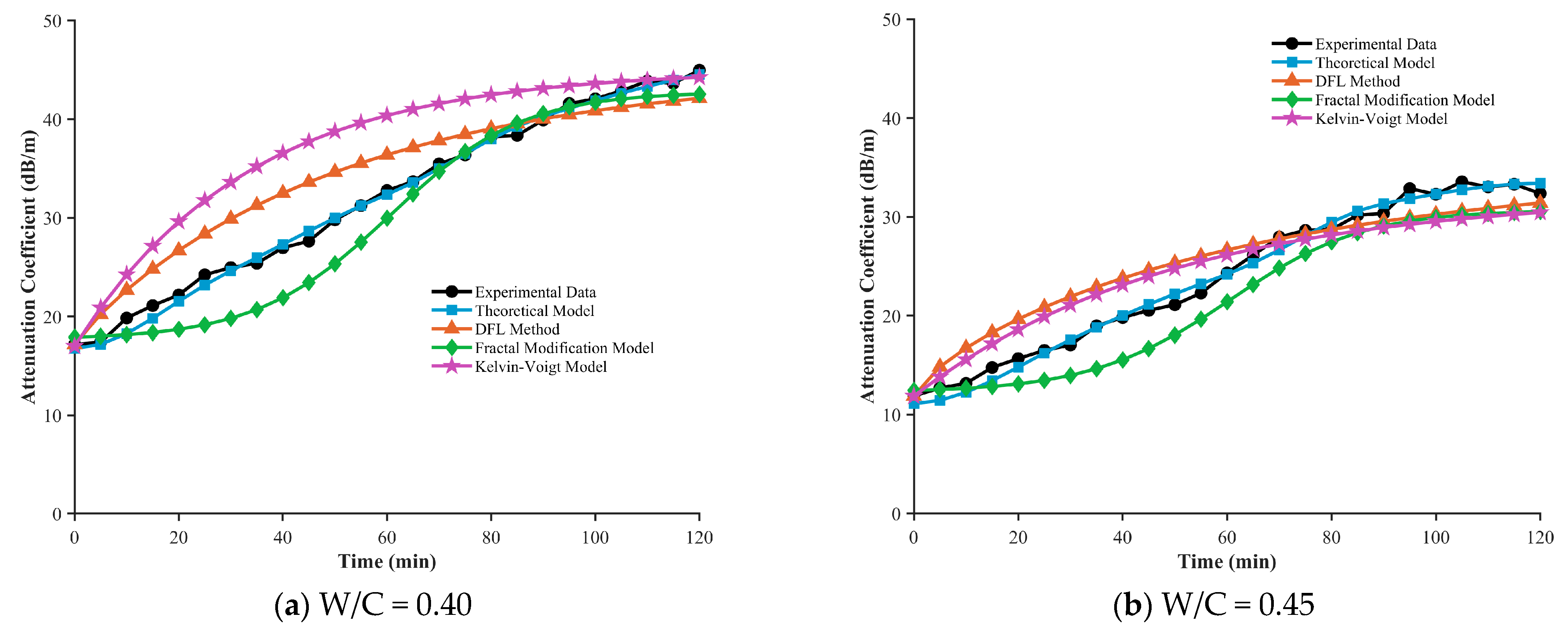

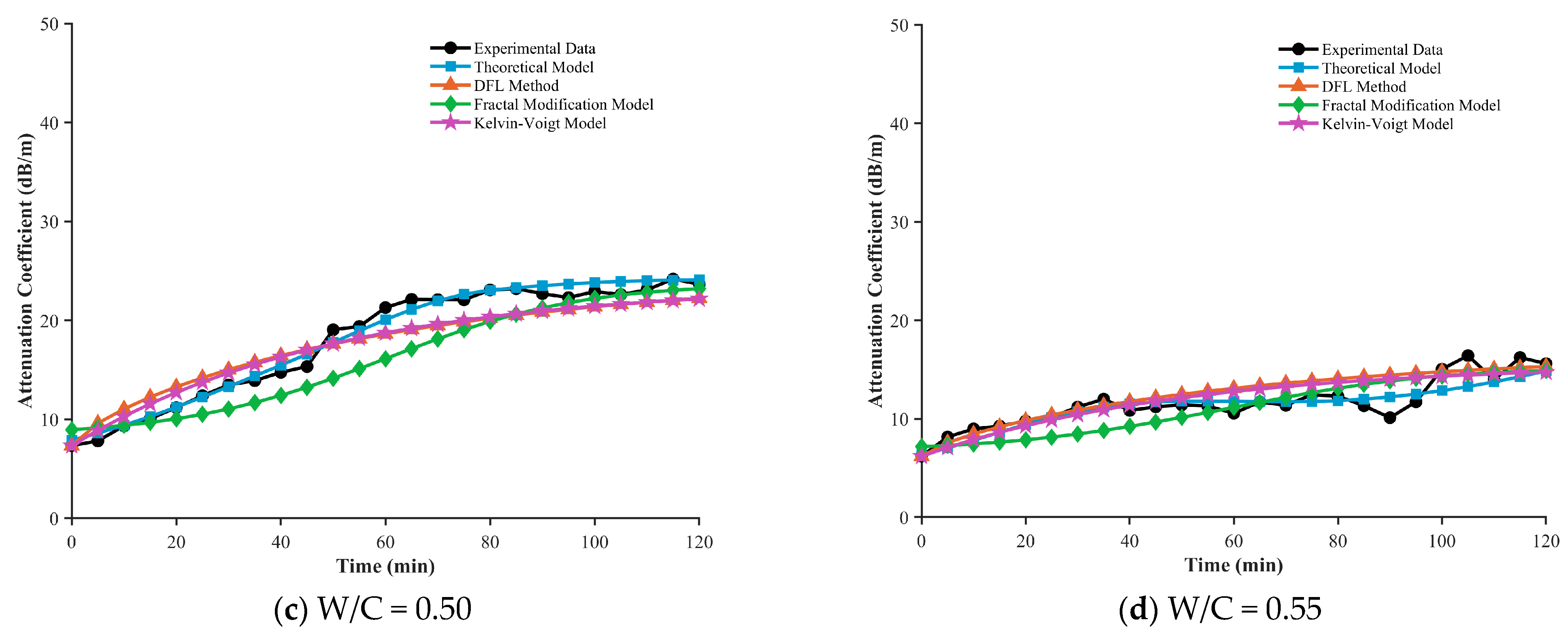

We performed a quantitative comparison between the proposed fractional model and three representative models—the DFL method, the Fractal Modification model, and the Kelvin–Voigt model—under different water–cement ratios (0.40, 0.45, 0.50, 0.55). The results are shown in

Figure 9, and the statistical summary of average relative errors for each model is provided in the accompanying

Table 2.

All models are able to capture the increasing trend of the attenuation coefficient over time, consistent with the physical evolution of the microstructure from a viscous fluid to a viscoelastic solid during cement hydration. However, the prediction accuracy varies markedly among the models. The fractional model proposed in this study exhibits the best performance across all water–cement ratios, with average relative errors of 1.85% (W/C = 0.40), 3.33% (W/C = 0.45), 3.54% (W/C = 0.50), and 7.11% (W/C = 0.55). It accurately reflects the temporal evolution of the attenuation coefficient.

In contrast, the prediction errors of the DFL method range from 10.61% to 12.32%, and those of the Fractal Modification model range from 8.07% to 13.16%, both significantly higher than those of the fractional model. As illustrated in (a) and (b), these models exhibit systematic overestimation in the early stage of setting (t < 60 min), particularly for W/C = 0.55, where the Fractal Modification model reaches an error of 13.16%. This behavior likely stems from the sensitivity of these models to the strong scattering effects induced by the rigid flocculated network formed at later hydration stages.

The classical Kelvin–Voigt model exhibits the highest instability among all models, with relative errors ranging from 9.27% to 18.42%. Notably, this model shows its largest error at a low water–cement ratio (W/C = 0.40, 18.42%), whereas the error becomes relatively smaller (9.27%) at a medium ratio (W/C = 0.50). This inconsistency reveals the difficulty of integer-order viscoelastic models in uniformly describing the complex viscoelastic behavior of cement pastes with different mix proportions.

Regarding the trend with water–cement ratio, prediction errors increase for all models as W/C increases from 0.40 to 0.55. For instance, the fractional model’s error increases from 1.85% to 7.11%, the DFL method from 10.61% to 10.71%, and the Fractal Modification model from 8.07% to 13.16%. This reflects that higher water–cement ratios introduce more free water and greater microstructural heterogeneity, thereby increasing the uncertainty in ultrasonic attenuation behavior. Despite this, the fractional model retains the highest prediction stability across all conditions: its maximum error (7.11%) is still lower than the minimum error of all other models, highlighting its advantage in modeling time-dependent material behavior through the fractional order .

Overall, these results demonstrate that the fractional model driven by ultrasonic sensing can accurately capture the microstructural evolution during cement paste setting. The fractional parameter serves as a real-time, sensitive indicator of the transition from viscous fluid to elastic solid. Compared with conventional rheometers—which require sample extraction and may disturb the hydration process—the proposed method enables continuous, non-invasive monitoring. Moreover, the model’s accurate description of low-frequency attenuation characteristics provides a solid theoretical basis for developing embedded real-time inversion algorithms.

From an SHM viewpoint, the monotonic and physically interpretable evolution of observed in the experiments highlights its potential as a state variable rather than a purely empirical fitting parameter. During early hydration, captures the transition from viscous-dominated to elastic-dominated behavior, while in later stages or under service conditions, changes in may reflect alterations in the internal stress state, microcrack density, or damage-induced viscoelasticity. Compared with traditional ultrasonic velocity or amplitude indicators, integrates attenuation behavior over a broad frequency band and is therefore less sensitive to measurement noise and boundary effects, which is advantageous for field-scale SHM applications.

The sensitivity of the proposed fractional-order ultrasonic model to aggregates, fibers, or reinforcement should be carefully discussed. In practical concrete, coarse aggregates introduce strong multiple scattering and impedance contrast, fibers induce anisotropic attenuation and dispersion, and steel reinforcement causes mode conversion and waveguiding effects. These factors primarily affect the propagation path and scattering characteristics of ultrasonic waves rather than the intrinsic viscoelastic behavior of the cementitious matrix.

From a modeling perspective, the fractional parameter represents an effective viscoelastic state of the load-bearing matrix at the scale of ultrasonic wavelengths. In heterogeneous composites, can therefore be interpreted as an equivalent or homogenized parameter that incorporates matrix behavior and mesoscale interactions. However, additional correction terms—such as aggregate-induced scattering losses or reinforcement-related boundary effects—would need to be explicitly incorporated into the attenuation model for quantitative interpretation in full concrete or reinforced concrete systems.

It should be acknowledged that the fractional parameter is influenced by multiple physical factors and should not be interpreted as a hydration-exclusive variable in a strict sense. In the present study, primarily reflects hydration-driven microstructural evolution because the experiments were conducted under well-controlled temperature and moisture conditions, with no external mechanical loading. Under such conditions, the dominant contribution to changes in originates from the progressive formation of the cementitious network and the associated viscoelastic transition.

In practical SHM applications, however, additional environmental and operational factors may affect the inferred value of . Temperature fluctuations can modify relaxation times and shift the frequency-dependent viscoelastic response, leading to apparent changes in . Moisture gradients may alter pore-fluid distribution and local damping behavior, while mechanical loading or microcracking can introduce irreversible changes in energy dissipation mechanisms. These effects are expected to influence ultrasonic attenuation through different physical pathways compared with hydration-induced structural build-up.

From an identifiability perspective, should therefore be regarded as an effective state parameter that integrates multiple contributions to viscoelastic attenuation. Decoupling hydration effects from environmental or damage-related influences requires auxiliary information and compensation strategies. For example, temperature effects can be mitigated through explicit temperature correction or multi-frequency normalization, while moisture-related variations may be constrained using humidity sensors or coupled poroelastic models. Load- or damage-induced changes in are typically non-monotonic and irreversible, in contrast to the monotonic and smooth evolution observed during early-age hydration, providing a potential criterion for distinguishing different mechanisms.

Consequently, the practical interpretation of in SHM should rely on baseline referencing and trend analysis rather than absolute values alone. When combined with environmental sensing, multi-parameter inversion, or digital twin frameworks, can be effectively decoupled from external influences and used as a robust indicator of material state evolution and structural integrity.

Building upon the identifiability framework discussed above, the practical deployment of the proposed sensing approach depends on the robustness and stability of the ultrasonic measurement system under realistic conditions. While the laboratory system demonstrates reliable performance under controlled environments, its field applicability requires careful consideration of long-term sensor durability, signal stability, and installation-related variability. In cementitious environments, the durability of embedded piezoelectric (PZT) transducers is mainly governed by mechanical protection, chemical compatibility, and moisture ingress; previous SHM studies have shown that appropriate encapsulation or inert housing can ensure stable electromechanical performance even under alkaline and moisture-rich conditions.

From a signal interpretation perspective, the proposed framework relies on baseline-referenced attenuation trends rather than absolute signal amplitudes, which inherently enhances robustness against slow signal drift caused by temperature fluctuations, curing-induced stiffness evolution, or gradual coupling changes over days or weeks. Provided that a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio is maintained, the fractional parameter can be consistently identified through trend analysis, supporting long-term monitoring applications. Although sensor coupling conditions and placement may affect absolute attenuation levels, their influence on the temporal evolution of is expected to be secondary when consistent excitation–reception paths, standardized embedding procedures, and network-based redundancy are employed. Overall, these considerations indicate that the sensing system and interpretation strategy are compatible with in situ SHM applications beyond laboratory settings.