State-of-Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on the CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Model Under Low- Temperature Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A hybrid deep learning architecture specifically tailored for low-temperature challenges is proposed. It synergistically integrates a 1D-CNN for extracting robust local features from noisy voltage and current sequences, Bi-LSTM for capturing complex bidirectional temporal dependencies, and an AM for dynamically weighting critical time steps [27], thereby enhancing model focus and suppressing interference from distorted signal segments.

- A systematic and focused evaluation under persistent low-temperature conditions is conducted. Unlike studies that primarily test at room or broad temperature ranges, this work rigorously validates the proposed model across three specific low-temperature setpoints using standard driving cycles, explicitly demonstrating its robustness against temperature-induced nonlinearities and performance degradation.

- Better estimation accuracy and comparative advantage are demonstrated. The model outperforms established benchmarks and other recent methods, confirming its effectiveness and advancement for low-temperature battery SOC estimation.

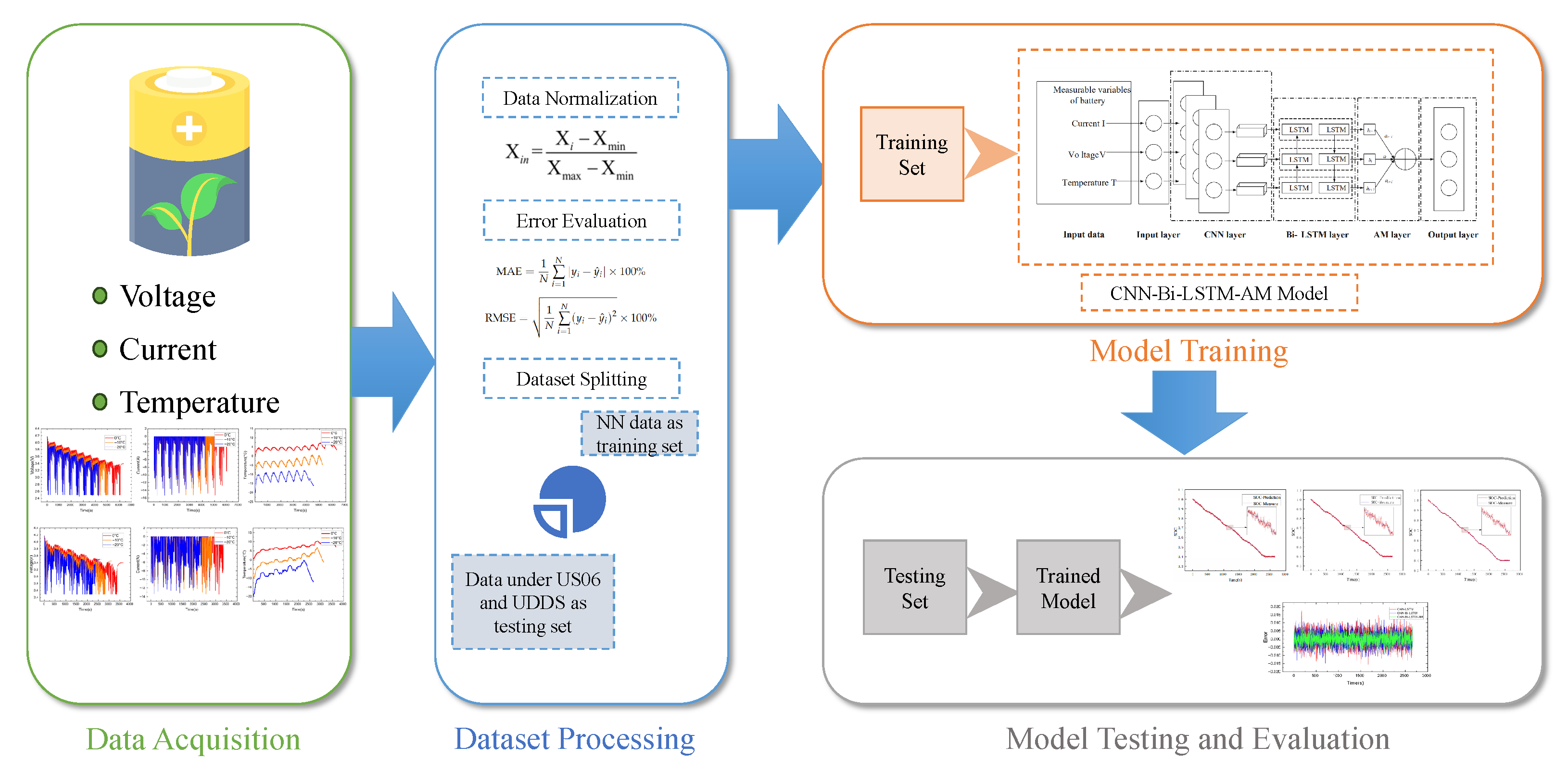

2. CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Model Design

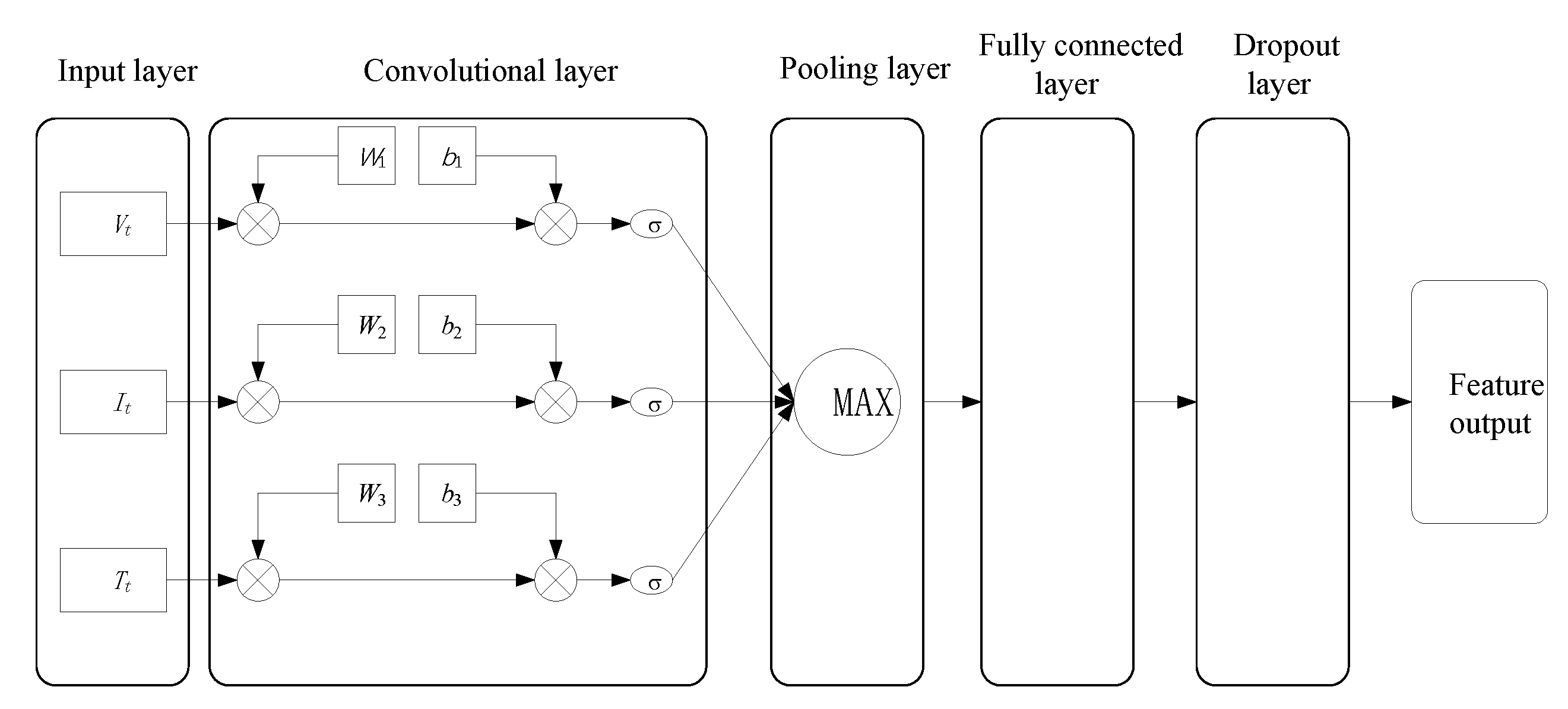

2.1. Convolutional Neural Network

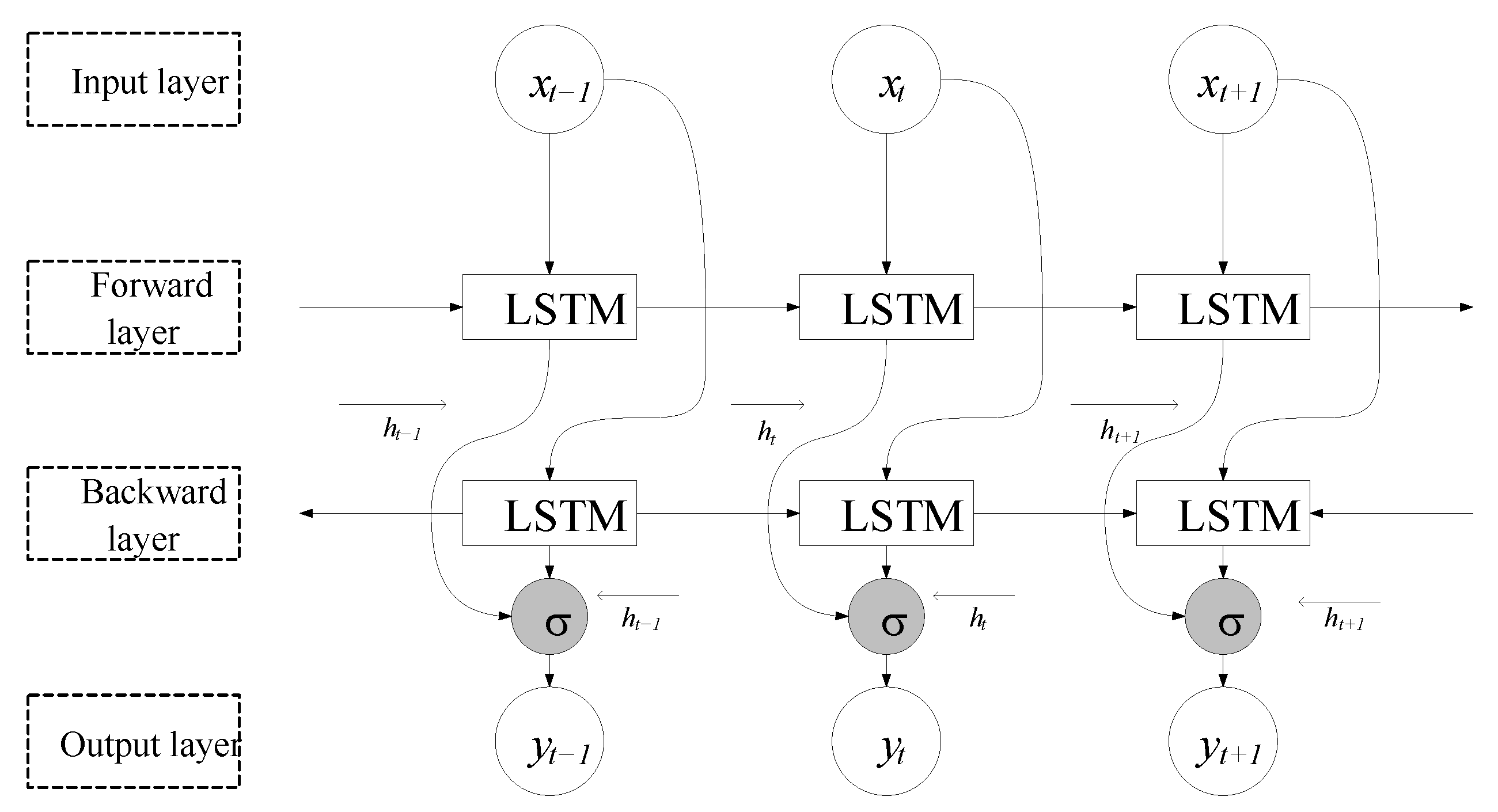

2.2. Bi-LSTM Network

2.3. Attention Mechanism

2.4. CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Network

3. Dataset Construction and Processing

3.1. Dataset Construction

3.2. Dataset Processing

3.2.1. Data Normalization

3.2.2. Error Evaluation Index

4. Example Results and Analysis

4.1. Simulation Environment

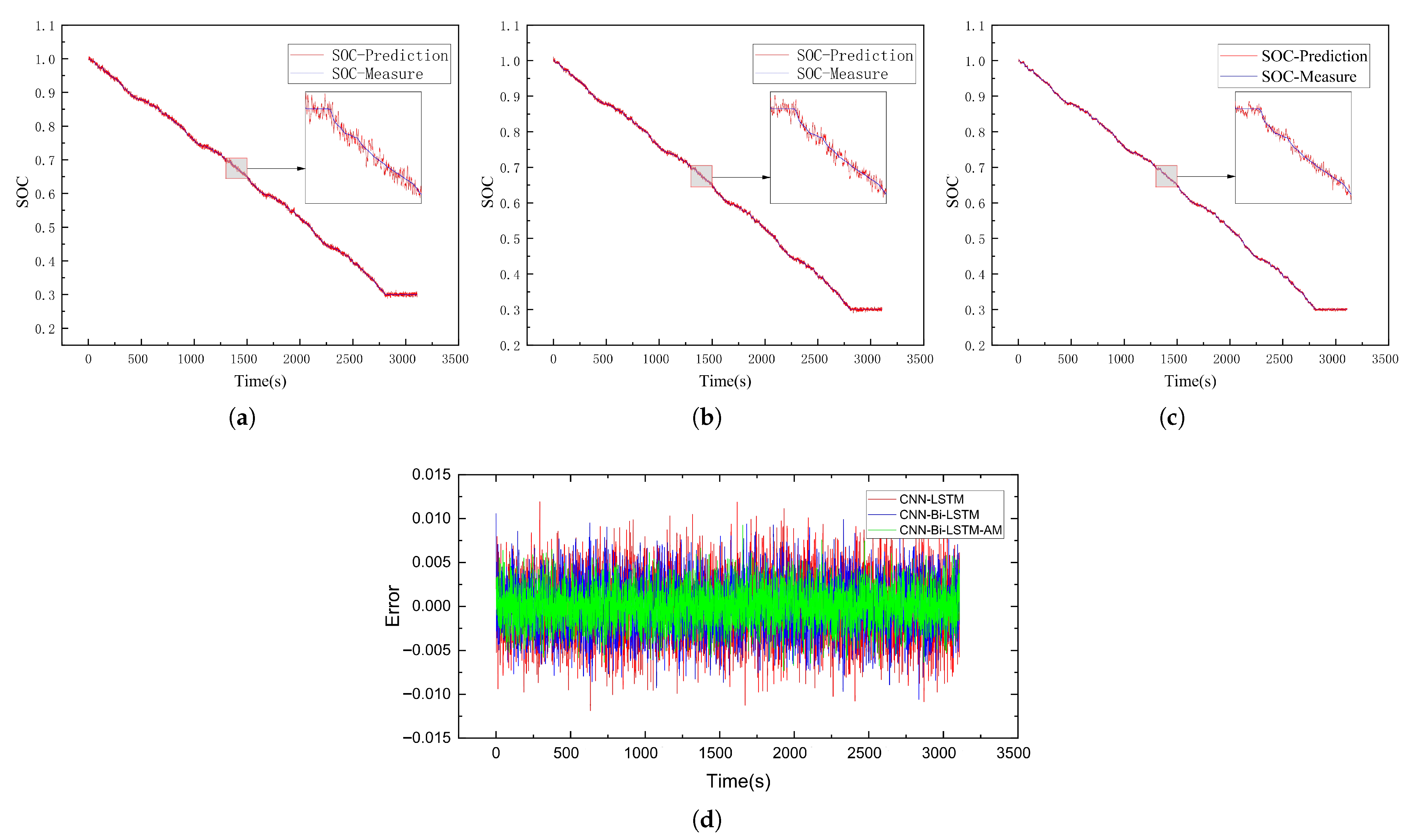

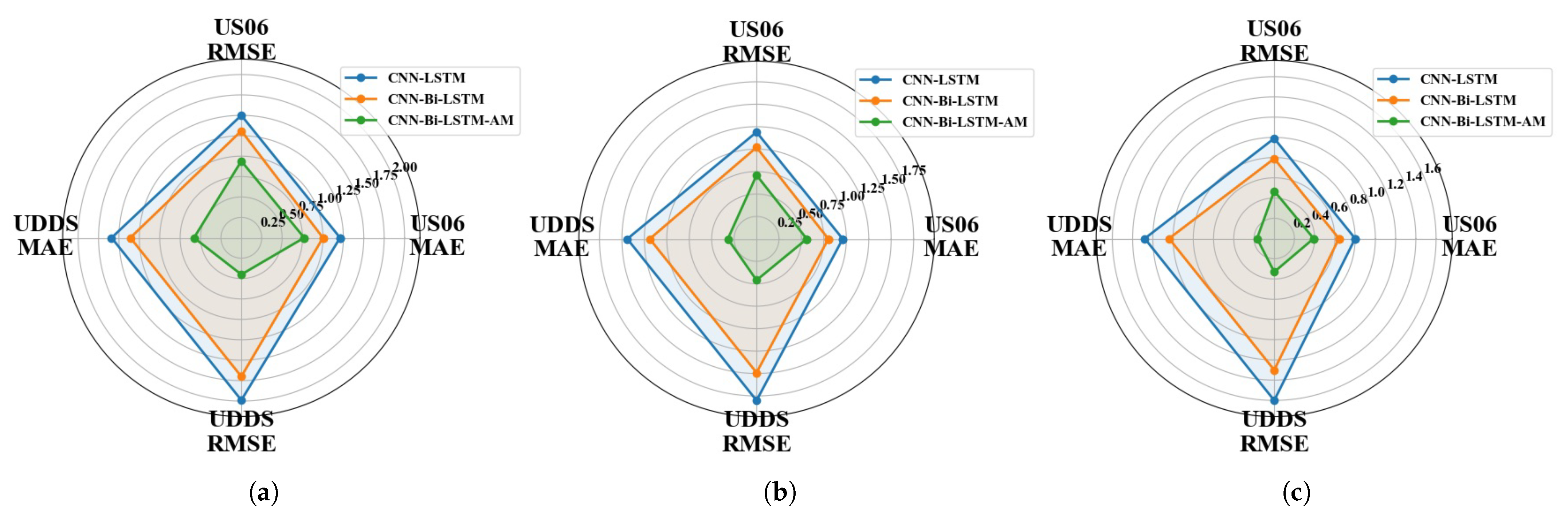

4.2. Battery SOC Estimation

4.3. Analysis of Results

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Future Work

- The logical next step is to transition from simulation to embedded deployment. Future work will focus on porting and optimizing the trained model for execution on embedded BMS hardware.

- To fully assess the model’s generalizability, evaluation under a complete spectrum of real-world operating conditions is essential.

- Exploring lightweight and efficient data preprocessing techniques will be considered.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, X.; Liu, M.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Grigoriev, S.; Hasanien, H.; Tang, X.; Li, R.; Sun, C. Polarization loss decomposition-based online health state estimation for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 157, 150162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Sun, C.; Mei, J.; Tang, X.; Hasanien, H.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F.; Song, K. Fuel cell life prediction considering the recovery phenomenon of reversible voltage loss. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, T. Design and implementation of a battery management system with active charge balance based on the SOC and SOH online estimation. Energy 2019, 166, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; Song, Q.; Yang, W. The application of hybrid energy storage system with electrified continuously variable transmission in battery electric vehicle. Energy 2019, 183, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, R.; Li, M.; Chen, Z. A comprehensive review of battery modeling and state estimation approaches for advanced battery management systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qi, W. New SOC estimation method under multi-temperature conditions based on parametric-estimation OCV. Power Electron. 2020, 20, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xiong, R.; Li, Q.; Chen, C.; Tian, J.; Shen, W. A novel pseudo-open-circuit voltage modeling method for accurate state-of-charge estimation of LiFePO4 batteries. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Wei, X.; Sun, Z.; Wang, J.; Gu, W. Online cell SOC estimation of Li-ion battery packs using a dual time-scale Kalman filtering for EV applications. Appl. Energy 2012, 95, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. A generic fusion framework integrating deep learning and Kalman filter for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries: Analysis and comparison. J. Power Sources 2024, 623, 235493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Hu, Y.; Jia, X.; Chen, G. A novel estimation of state of charge for the lithium-ion battery in electric vehicle without open circuit voltage experiment. Energy 2022, 243, 123072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Gao, Y.; Kou, Y. Parameter and State of Charge Estimation Simultaneously for Lithium-Ion Battery Based on Improved Open Circuit Voltage Estimation Method. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, J.; Moon, I. Hybrid data-driven deep learning model for state of charge estimation of Li-ion battery in an electric vehicle. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, I.; Wang, W.; Su, S.; Lee, Y. A merged fuzzy neural network and its applications in battery state-of-charge estimation. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2007, 22, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Antón, J.C.; García Nieto, P.J.; Blanco Viejo, C.; Vilán Vilán, J.A. Support vector machines used to estimate the battery state of charge. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 5919–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W. Estimation of the state of charge for a LFP battery using a hybrid method that combines a RBF neural network, an OLS algorithm and AGA. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 53, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobobee, E.D.; Wang, S.; Takyi-Aninakwa, P.; Zou, C.; Appiah, E.; Hai, N. Improved particle swarm optimization–long short-term memory model with temperature compensation ability for the accurate state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Hu, X.; Lin, X.; Che, Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, W. Data-driven state of charge estimation for lithium-ion battery packs based on Gaussian process regression. Energy 2020, 205, 118000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. State of health estimation of power batteries based on multi-feature fusion models using stacking algorithm. Energy 2022, 295, 124851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Cheng, W.; Zhu, Q. SOC estimation for lithium-ion battery using the LSTM-RNN with extended input and constrained output. Energy 2023, 262, 125375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Kuldip, K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; He, H.; Yang, S. Stacked bidirectional long short-term memory networks for state-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Energy 2020, 191, 116538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Feng, R.; Xie, Y.; Fernandez, C. Multi-temperature capable enhanced bidirectional long short term memory-multilayer perceptron hybrid model for lithium-ion battery SOC estimation. Energy 2024, 312, 133596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; He, H.; Yang, S.; Huang, T. State-of-charge sequence estimation of lithium-ion battery based on bidirectional long short-term memory encoder-decoder architecture. J. Power Sources 2020, 449, 227558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zheng, W.; Tang, D.; Li, Y.; Xing, Y. A knowledge-constrained CNN-BiLSTM model for lithium-ion batteries state-of-charge estimation. Microelectron. Reliab. 2023, 150, 115112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Khan, N.M.; Houran, M.A.; Mansoor, M.; Akhtar, N.; Sanfilippo, F. A novel hybrid deep learning model for accurate state of charge estimation of Li-Ion batteries for electric vehicles under high and low temperature. Energy 2024, 292, 130584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lai, R.; Tian, J. State-of-charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries based on attentional sequence-to-sequence architecture. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Hua, B.; Xiong, N. State of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries based on temporal convolutional network and transfer learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 34177–34187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kang, S. Development of optimal energy management strategy for proton exchange membrane fuel cell-battery hybrid system for drone propulsion. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Mei, J.; Tang, X.; Jiang, J.; Sun, C.; Song, K. The Degradation Prediction of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Performance Based on a Transformer Model. Energies 2024, 17, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.; Strange, C.; Yadav, M.; Li, S. Lithium-ion battery data and where to find it. Energy AI 2021, 5, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmeyer, P. Panasonic 18650PF Li-ion Battery Data. Mendeley Data 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, D.; Tsui, K. Combined CNN-LSTM network for state-of-charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 88894–88902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Meng, X.; Tang, X.; Li, H.; Hasanien, H.; Alharbi, M.; Dong, Z.; Shen, J.; Sun, C.; Fan, F.; et al. An Accurate Parameter Estimation Method of the Voltage Model for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Energies 2024, 17, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yan, C.; Wang, L.; Dou, W.; Li, Y.; Gao, G.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y.; Tan, X. Data-driven SOC estimation method for power batteries under driving cycle conditions and a wide temperature range. Energy 2025, 340, 139147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Specification |

|---|---|

| Cell Type | 18650 Cylindrical |

| Chemistry | Panasonic NMC/Graphite |

| Nominal Capacity | 2.9 Ah |

| Nominal Voltage | 3.6 V |

| Voltage Range | 2.5–4.2 V |

| Total Number of Cells | 1 |

| Operating Temperature | −20–60 °C |

| Test Temperatures | −20 °C, −10 °C, 0 °C |

| Data Source | Public dataset provided by the University of Wisconsin–Madison [33] |

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of CNN filters | 64 |

| Number of hidden layer neurons | 64 |

| Excitation | ReLU, Sigmoid |

| Data sampling interval | 0.1 s |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Initial learning rate | 0.001 |

| Mini-batch size | 64 |

| Max epochs | 700 |

| Loss function | MSE |

| Reference | Method | Temperature (°C) | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| [6] | OCV-PE | −20, −10, 0 | MAE = 4.1–4.9% RMSE = 2.32–3.31% |

| [10] | FFRLS-AEKF | 0 | MAE = 0.91% RMSE = 1.52% |

| [11] | OCV-DAKEF | −10, 0 | RMSE = 0.65–0.86% |

| [17] | Autoregressive GPR | 0 | RMSE = 1.91–2.99% |

| [19] | EI-LSTM-CO | 0 | RMSE = 1.3–1.5% |

| [23] | Bi-LSTM encoder-decoder | −20, −10, 0 | MAE = 1.26–2.32% |

| Our Study | CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM | −20, −10, 0 | MAE = 0.17–0.77% RMSE = 0.33–0.94% |

| Performance | Mamba | KAN | CNN-LSTM | CNN-Bi-LSTM | Proposed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation Time (ms) | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.40 |

| Params (M) | 2.64 | 1.47 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 1.54 |

| Model Size (MB) | 10.56 | 5.88 | 2.49 | 2.66 | 4.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, R.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lv, Y. State-of-Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on the CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Model Under Low- Temperature Environments. Sensors 2026, 26, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010264

Li R, Hao Y, Zhang M, Lv Y. State-of-Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on the CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Model Under Low- Temperature Environments. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010264

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ran, Yiming Hao, Mingze Zhang, and Yanling Lv. 2026. "State-of-Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on the CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Model Under Low- Temperature Environments" Sensors 26, no. 1: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010264

APA StyleLi, R., Hao, Y., Zhang, M., & Lv, Y. (2026). State-of-Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on the CNN-Bi-LSTM-AM Model Under Low- Temperature Environments. Sensors, 26(1), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010264