A Six-Tap 720 × 488-Pixel Short-Pulse Indirect Time-of-Flight Image Sensor for 100 m Outdoor Measurements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Multi-Tap Pixel Architecture

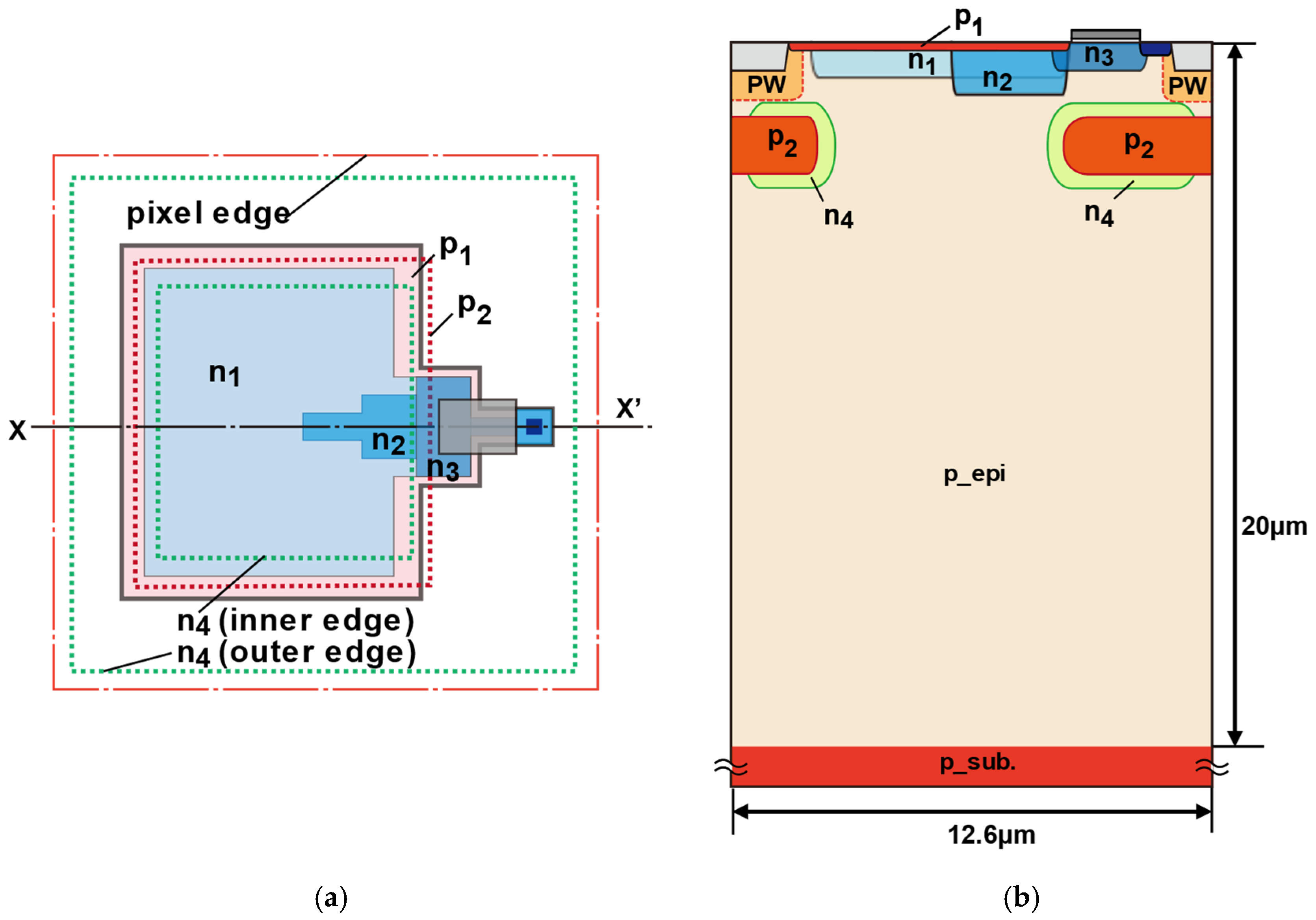

2.1. Pixel Structure for Photodiode and Demodulator

- (a)

- n1 is distributed across the front surface to cover the wide photo-sensitive region.

- (b)

- n2 is positioned to generate a lateral drift field that guides photoelectrons from the central portion of the n1 region toward the vicinity of the modulation gate.

- (c)

- n3 is located at the front edge and channel regions of the demodulation gate to enhance the potential modulation amplitude around the gate.

2.2. Six-Tap Demodulation Pixel

2.3. Pixel Potential Simulation

3. ToF Measurement Method Using 6-Tap Pixels

3.1. Depth Measurement Algorithm in Single Subframe

3.2. Range Extention Using Subframes

4. Measurement Results

4.1. Chip Specifications

4.2. Demodulation Characteristics

4.3. Pixel Response Characteristics

4.4. Outdoor Distance Measurement

4.5. Comparison with Other Depth Sensors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, C.; Kong, W.; Huang, G.; Hou, J.; Jia, S.; Chen, T.; Shu, R. Design and Demonstration of a Novel Long-Range Photon-Counting 3D Imaging LiDAR with 32 × 32 Transceivers. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Li, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, K.; Xu, D.; Yao, J. Dithered Depth Imaging for Single-Photon Lidar at Kilometer Distances. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niclass, C.; Rochas, A.; Besse, P.-A.; Charbon, E. Design and characterization of a CMOS 3-D image sensor based on single photon avalanche diodes. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2005, 40, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niclass, C.; Soga, M.; Matsubara, H.; Ogawa, M.; Kagami, M. A 0.18-μ m CMOS SoC for a 100-m-Range 10-Frame/s 200 × 96-Pixel Time-of-Flight Depth Sensor. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2014, 49, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.H.; Chu, T.S. A Direct-Sampling Pulsed Time-of-Flight Radar with Frequency-Defined Vernier Digital-to-Time Converter in 65 nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2015, 50, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perenzoni, M.; Perenzoni, D.; Stoppa, D. A 64 × 64-Pixels Digital Silicon Photomultiplier Direct TOF Sensor with 100-MPhotons/s/pixel Background Rejection and Imaging/Altimeter Mode with 0.14% Precision Up To 6 km for Spacecraft Navigation and Landing. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2017, 52, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, S.; Kubota, H.; Katagiri, H.; Ota, Y.; Hirono, M.; Ta, T.T. An Automotive LiDAR SoC for 240 × 192-Pixel 225-m-Range Imaging with a 40-Channel 0.0036-mm2 Voltage/Time Dual-Data-Converter-Based AFE. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2020, 55, 2866–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagami, O.; Ohmachi, J.; Matsumura, M.; Yagi, S.; Tayu, K.; Amagawa, K. A 189 × 600 Back-Illuminated Stacked SPAD Direct Time-of-Flight Depth Sensor for Automotive LiDAR Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–22 February 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, N.; Ma, Z.; Wang, L.; Qin, Y.; Jia, J. A 240 × 160 3D-Stacked SPAD dToF Image Sensor with Rolling Shutter and In-Pixel Histogram for Mobile Devices. IEEE Open J. Solid-State Circuits 2021, 2, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Ta, T.T.; Kokubun, L.; Kondo, S.; Itakura, T.; Katagiri, H. 1200 × 84-pixels 30 fps 64cc Solid-State LiDAR RX with an HV/LV transistors Hybrid Active-Quenching-SPAD Array and Background Digital PT Compensation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits, Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Park, S.; Chun, J.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, S.J. A 160 × 120 Flash LiDAR Sensor with Fully Analog-Assisted In- Pixel Histogramming TDC Based on Self-Referenced SAR ADC. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–22 February 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, R.; Seitz, P. Solid-state time-of-flight range camera. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2001, 37, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppa, D.; Massari, N.; Pancheri, L.; Malfatti, M.; Perenzoni, M.; Gonzo, L. A Range Image Sensor Based on 10-μm Lock-In Pixels in 0.18-μm CMOS Imaging Technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2011, 46, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.D.K.; Kang, B.; Lee, K. A CMOS Image Sensor Based on Unified Pixel Architecture with Time-Division Multiplexing Scheme for Color and Depth Image Acquisition. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2011, 46, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamji, C.S.; Mehta, S.; Thompson, B.; Elkhatib, T.; Wurster, S.; Akkaya, O.; Payne, A.; Godbaz, J.; Fenton, M.; Rajasekaran, V.; et al. 1 Mpixel 65 nm BSI 320 MHz demodulated TOF Image sensor with 3 μm global shutter pixels and analog binning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–15 February 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Sano, T.; Moriyama, Y.; Maeda, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Nose, A.; Shina, K.; Yasu, Y.; Tempel, W.; Ercan, A.; et al. 320 × 240 Back-illuminated 10 μm CAPD pixels for high speed modulation Time-of-Flight CMOS image sensor. In Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on VLSI Circuits, Kyoto, Japan, 5–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, M.; Jin, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Bae, M.; Chung, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; An, T.; et al. A 640 × 480 indirect time-of-flight CMOS image sensor with 4-tap 7 m global-shutter pixel and fixed-pattern phase noise self-compensation scheme. In Proceedings of the 2019 Symposium on VLSI Circuits, Kyoto, Japan, 9–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Park, D.; Piao, C.; Park, J. Indirect Time-of-Flight CMOS Image Sensor with On-Chip Background Light Cancelling and Pseudo-Four-Tap/Two-Tap Hybrid Imaging for Motion Artifact Suppression. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2020, 55, 2849–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebiko, Y.; Yamagishi, H.; Tatani, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Moriyama, Y.; Hagiwara, Y.; Maeda, S.; Murase, T.; Suwa, T.; Arai, H.; et al. Low power consumption and high resolution 1280X960 Gate Assisted Photonic Demodulator pixel for indirect Time of flight. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–18 December 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamji, C.S.; O’Connor, P.; Elkhatib, T.; Mehta, S.; Thompson, B.; Prather, L.A.; Snow, D.; Akkaya, O.C.; Daniel, A.; Payne, A.D.; et al. A 0.13 μm CMOS System-on-Chip for a 512 × 424 Time-of-Flight Image Sensor with Multi-Frequency Photo-Demodulation up to 130 MHz and 2 GS/s ADC. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2015, 50, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, M.-S.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Bae, M.; Ki, M.; Chung, B.; Son, S.; Lee, H.; Jo, H.; Shin, S.-C.; et al. A 4-tap 3.5 μm 1.2 Mpixel Indirect Time-of-Flight CMOS Image Sensor with Peak Current Mitigation and Multi-User Interference Cancellation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–22 February 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, G.; Davidovic, M.; Zimmermann, H. A 16 × 16 Pixel Distance Sensor with In-Pixel Circuitry That Tolerates 150 klx of Ambient Light. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2010, 45, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahito, S.; Izhal, A.H.; Ushinaga, T.; Sawada, T.; Homma, M.; Maeda, Y. A CMOS Time-of-Flight Range Image Sensor with Gates-on-Field-Oxide Structure. IEEE Sens. J. 2007, 7, 1578–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickermann, A.; Durini, D.; Suss, A.; Ulfig, W.; Brockherde, W.; Hosticka, B.J.; Schwope, S.; Grabmaier, A. CMOS 3D image sensor based on pulse modulated time-of-flight principle and intrinsic lateral drift-field photodiode pixel. In Proceedings of the 2011 Proceedings of the ESSCIRC, Helsinki, Finland, 12–16 September 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, R.; Shirakawa, Y.; Mars, K.; Yasutomi, K.; Kagawa, K.; Aoyama, S.; Kawahito, S. A Time-of-Flight Image Sensor Using 8-Tap P-N Junction Demodulator Pixels. Sensors 2023, 23, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, K.; Okubo, Y.; Nakagome, T.; Makino, M.; Takashima, H.; Akutsu, T.; Sawamoto, T.; Nagase, M.; Noguchi, T.; Kawahito, S. A Hybrid ToF Image Sensor for Long-Range 3D Depth Measurement Under High Ambient Light Conditions. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2023, 58, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegannathan, G.; Seliuchenko, V.; Dries, T.V.d.; Lapauw, T.; Boulanger, S.; Ingelberts, H.; Kuijk, M. An Overview of CMOS Photodetectors Utilizing Current-Assistance for Swift and Efficient Photo-Carrier Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahito, S.; Yasutomi, K.; Mars, K. Hybrid Time-of-Flight Image Sensors for Middle-Range Outdoor Applications. IEEE Open J. Solid-State Cir. Soc. 2021, 2, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okino, T.; Yamada, S.; Sakata, Y.; Kasuga, S.; Takemoto, M.; Nose, Y.; Koshida, H.; Tamaru, M.; Sugiura, Y.; Saito, S.; et al. A 1200 × 900 6 µm 450 fps Geiger-Mode Vertical Avalanche Photodiodes CMOS Image Sensor for a 250m Time-of-Flight Ranging System Using Direct-Indirect-Mixed Frame Synthesis with Configurable-Depth-Resolution Down to 10 cm. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–20 February 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximenes, A.R.; Padmanabhan, P.; Lee, M.-J.; Yamashita, Y.; Yaung, D.N.; Charbon, E. A 256 × 256 45/65 nm 3D-stacked SPAD-based direct TOF image sensor for LiDAR applications with optical polar modulation for up to 18.6 dB interference suppression. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–15 February 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.K.; Johnston, N.; Hutchings, S.W.; Gyongy, I.; Abbas, T.A.; Dutton, N.; Tyler, M.; Chan, S.; Leach, J. A 256 × 256 40 nm/90 nm CMOS 3D-Stacked 120 dB Dynamic-Range Reconfigurable Time-Resolved SPAD Imager. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–21 February 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, P.; Zhang, C.; Cazzaniga, M.; Efe, B.; Ximenes, A.R.; Lee, M.-J.; Charbon, E. A 256 × 128 3D-Stacked (45 nm) SPAD FLASH LiDAR with 7-Level Coincidence Detection and Progressive Gating for 100 m Range and 10 klux Background Light. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–22 February 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, Y.; Koyama, S.; Okino, T.; Inoue, A.; Saito, S.; Nose, Y.; Ishii, M.; Yamahira, S.; Kasuga, S.; Mori, M.; et al. A 400 × 400-Pixel 6 μm-Pitch Vertical Avalanche Photodiodes CMOS Image Sensor Based on 150 ps-Fast Capacitive Relaxation Quenching in Geiger Mode for Synthesis of Arbitrary Gain Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 17–21 February 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, K.; Ageishi, S.; Hakamata, M.; Sakita, T.; Iguchi, D.; Hayakawa, J.; Yasutomi, K.; Kagawa, K.; Kawahit, S. A Multi-Zone Light-Tracing Hybrid Time-of-Flight CMOS Image Sensor for Low Power Long-Range Outdoor Operations. In Proceedings of the International Image Sensor Workshop, Hyogo, Japan, 2–5 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Chi, K.; Kuroda, R. A 4-Tap CMOS Time-of-Flight Image Sensor with In-pixel Analog Memory Array Achieving 10 Kfps High-Speed Range Imaging and Depth Precision Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2022 Symposium on VLSI Circuits, Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Path1 | Path2 | Path3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| x coordinate at start | 0.4 µm | 0.4 µm | 12.2 µm |

| y coordinate at start | 0.4 µm | 12.2 µm | 6.3 µm |

| z coordinate at start | 20.0 µm | 20.0 µm | 20.0 µm |

| Transfer time | 1.85 ns | 2.01 ns | 1.50 ns |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Process | 0.11 μ m FSI CMOS |

| Pixel Array | 720 (H) × 488 (V) |

| Pixel Pitch | 12.6 μm × 12.6 μm |

| Chip Size | 9.1 mm × 6.1 mm |

| Epi. Thickness (=full well depth) | 20 μm |

| Number of Taps | 6 Tap, 1 Drain |

| ADC Resolution | 12 bit |

| Read Noise | 41 e− |

| Full Well Capacity | 22 ke− |

| Dynamic Range | 55 dB |

| Conversion Gain | 34.2 μV/e− |

| Quantum Efficiency | 23.8% @840 nm 10.6% @940 nm |

| Parasitic Light Sensitivity | 0.003% |

| Power Consumption | 0.6 W |

| Gate# | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD [%] | 96.4 | 91.0 | 91.2 | 90.8 | 89.7 | 96.7 | 92.6 |

| Gate# | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | G6 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time constant [ns] | Rise | 1.02 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.83 |

| Fall | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.79 | |

| FWHM [ns] | Rise | 2.13 | 1.93 | 1.50 | 1.69 | 1.67 | 1.81 | 1.74 |

| Fall | 1.90 | 1.60 | 1.48 | 1.72 | 1.81 | 1.67 | 1.65 | |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Pulse width: TP | 20 ns |

| Pulse cycle: TC | 10 µs |

| Readout time: TR1~TR5 | 4.38 ms |

| TA1 (NA1) | 2.23 ms (223) |

| TA2 (NA2) | 6.61 ms (661) |

| TA3 (NA3) | 13.3 ms (1330) |

| TA4 (NA4) | 22.31 ms (2231) |

| TA5 (NA5) | 33.64 ms (3364) |

| Framerate | 10 fps |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Light source | 940 nm VCSEL |

| Optical light power | 2.1 W @average |

| Filter bandwidth | 950 ± 25 nm |

| Lens focal length | 50 mm |

| Lens F-number | 1 |

| FOV | 10.4 degrees @Horizontal 7.1 degrees @Vertical |

| This Work | [18] | [19] | [26] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | SP-iToF | CW-iToF | CW-iToF | SP-iToF |

| Process | 110 nm FSI | 90 nm BSI | 90 nm/65 nm Stacked BSI | 110 nmBSI |

| Pixel array | 720 × 488 | 320 × 240 | 1280 × 960 320 × 240 (4 × 4 bin.) | 640 × 480 |

| Depth pixel pitch H × V [μm2] (area [μm2]) | 12.6 × 12.6 (158.67) | 8 × 8 (64) | 3.5 × 3.5 14 × 14 (4 × 4 bin.) (196) | 5.6 × 5.6 (31.36) |

| Number of taps | 6 | Pseudo 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Ambient light [klux] | 100 | 130 | 80 | 100 |

| Frame rate [fps] | 10 | 10–60 | n.a. | 15 |

| Maximum range [m] (outdoor operation) | 100 | 4 | 10 (4 × 4 bin.) | 20 |

| Depth noise [r.m.s. % full scale] | 0.9 (R: 10%) 0.1 (R: 80%) | 0.54 (R: n.a.) | 1.6 (R: n.a.) | 1.3 (R: n.a.) |

| This Work | [10] | [8] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | SP-iToF | dToF | dToF |

| Process | 110 nm FSI | 0.13 μm SPAD | 90 nm/40 nm SPAD |

| Pixel array | 720 × 488 | 1200 × 84 | 168 × 63 |

| Lighting method | Flash | 1D scan | 1D scan |

| Depth pixel pitch H × V [μm2] (area [μm2]) | 12.6 × 12.6 (158.67) | 12.5 × 89 (1112.5) | 30 × 30 (900) |

| FoV [degrees] | 10.4 × 7.1 | 24 × 12 | 25.2 × 9.45 |

| Angular resolution [degrees] | 0.014 × 0.014 | 0.02 × 0.13 | 0.15 × 0.15 |

| Peak light power [W] | 1350 | n.a. | 45 |

| Ambient light [klux] | 100 | 110 | 117 |

| Frame rate [fps] | 10 | 30 | 20 |

| Maximum range [m] (outdoor operation) | 100 | 200 | 150 (R: 10%) |

| Depth noise [r.m.s. % full scale] | 0.9 (R: 10%) 0.1 (R: 80%) | 0.15 (R: 10%) | 0.1 (R: 10%) |

| FoM [% nJ rad2] | 1.2 | - | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Itaba, K.; Mars, K.; Yasutomi, K.; Kagawa, K.; Kawahito, S. A Six-Tap 720 × 488-Pixel Short-Pulse Indirect Time-of-Flight Image Sensor for 100 m Outdoor Measurements. Sensors 2026, 26, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010026

Itaba K, Mars K, Yasutomi K, Kagawa K, Kawahito S. A Six-Tap 720 × 488-Pixel Short-Pulse Indirect Time-of-Flight Image Sensor for 100 m Outdoor Measurements. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleItaba, Koji, Kamel Mars, Keita Yasutomi, Keiichiro Kagawa, and Shoji Kawahito. 2026. "A Six-Tap 720 × 488-Pixel Short-Pulse Indirect Time-of-Flight Image Sensor for 100 m Outdoor Measurements" Sensors 26, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010026

APA StyleItaba, K., Mars, K., Yasutomi, K., Kagawa, K., & Kawahito, S. (2026). A Six-Tap 720 × 488-Pixel Short-Pulse Indirect Time-of-Flight Image Sensor for 100 m Outdoor Measurements. Sensors, 26(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010026