Quality Assessment of a Foot-Mounted Inertial Measurement Unit System to Measure On-Field Spatiotemporal Acceleration Metrics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

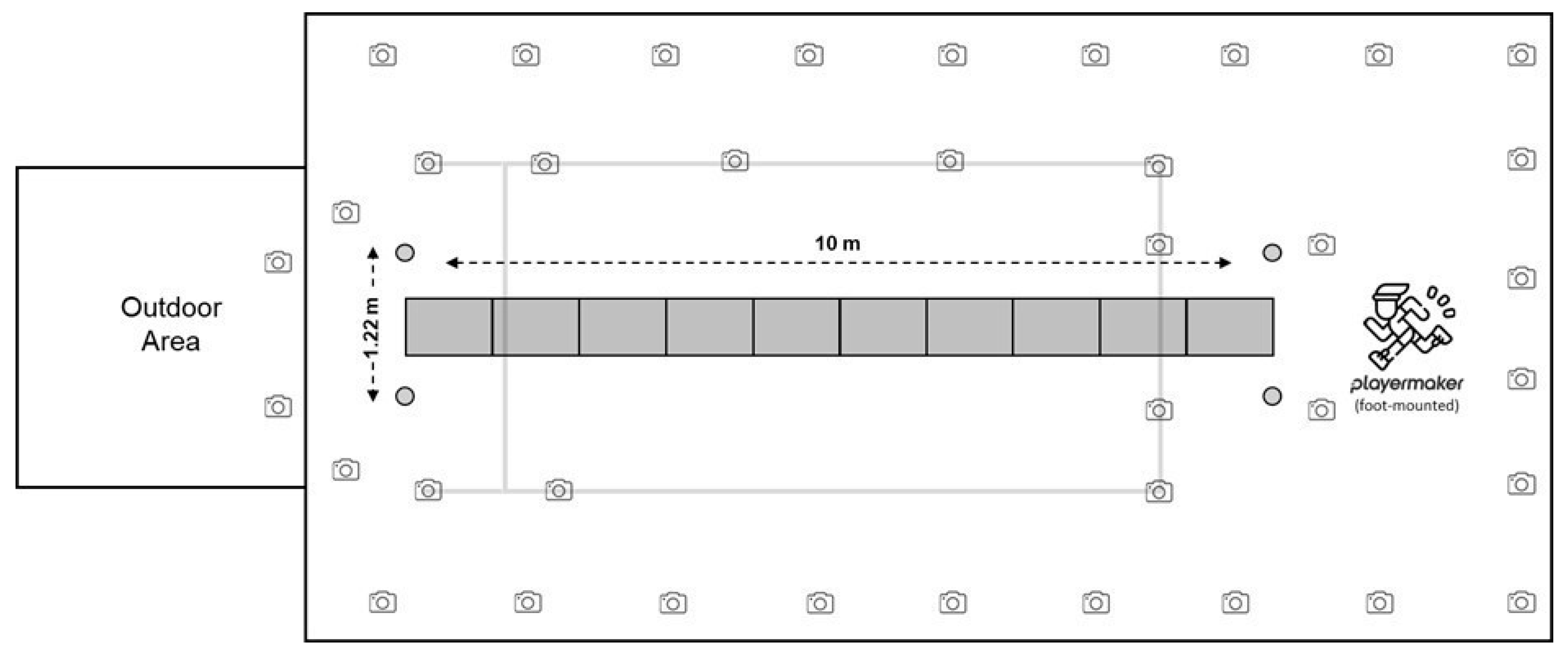

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Processing

2.4. Statistical Analyses

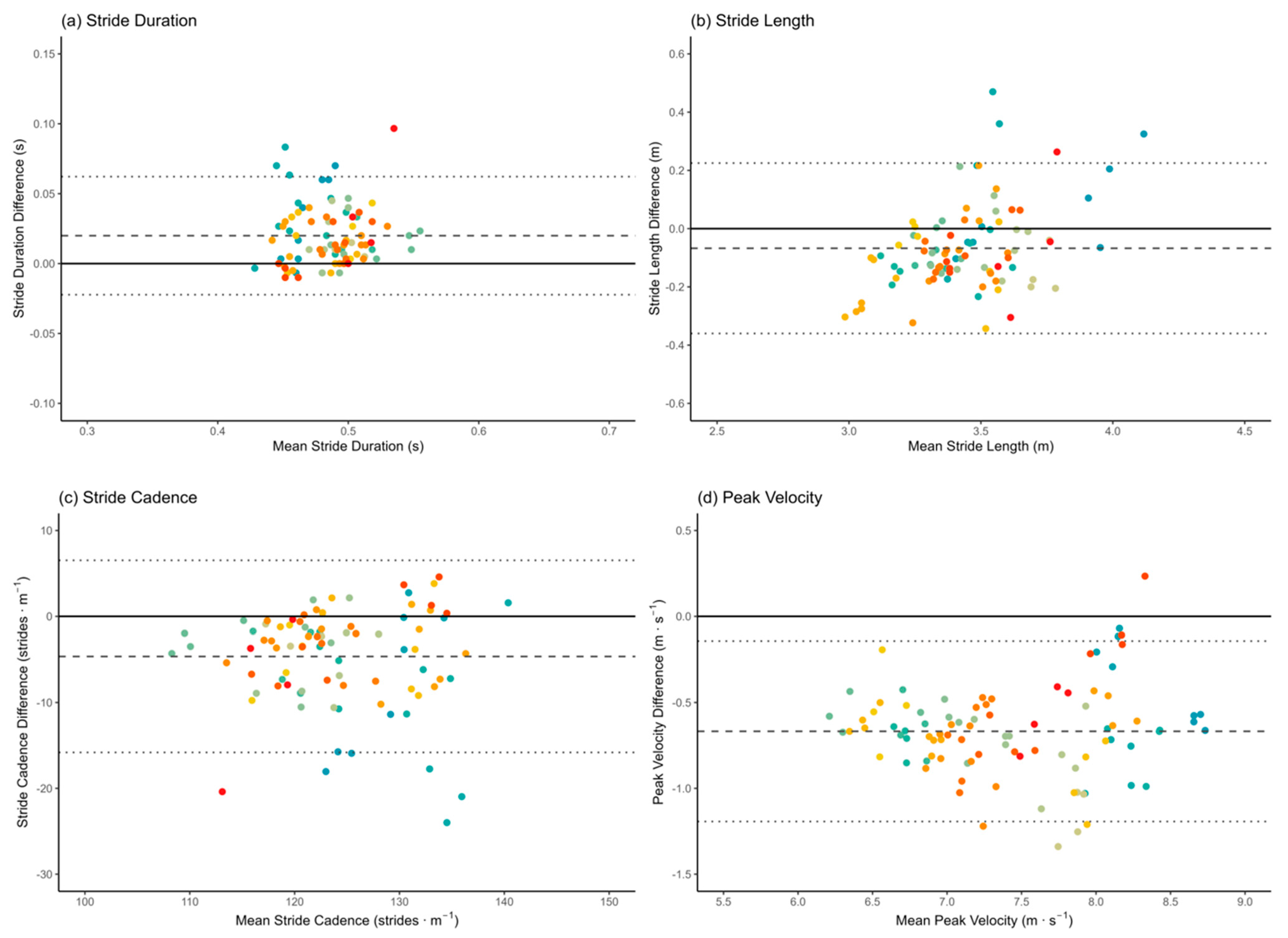

3. Results

| Variable | Technology | Mean ± SD | MAE | RMSE | Mean Bias (95% LoA) | Spearman’s Correlation (ρ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stride duration (s) | Playermaker | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 (−0.02; 0.06) | 0.60 |

| VICON | 0.47 ± 0.02 | |||||

| Stride length (m) | Playermaker | 3.37 ± 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.22 | −0.07 (−0.36; 0.23) | 0.72 |

| VICON | 3.45 ± 0.19 | |||||

| Stride cadence (strides ) | Playermaker | 122.08 ± 9.05 | 6.25 | 8.94 | −4.64 (−15.81; 6.53) | 0.61 |

| VICON | 126.47 ± 7.57 | |||||

| Peak velocity () | Playermaker | 7.10 ± 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.72 | −0.67 (−1.19; −0.14) | 0.92 |

| VICON | 7.76 ± 0.66 | |||||

| Inst. velocity ( | Playermaker | 6.80 ± 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.56 | −0.50 (−1.10; 0.09) | 0.91 |

| VICON | 7.30 ± 0.63 | |||||

| Inst. acceleration () | Playermaker | 0.19 ± 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.64 | 0.17 (−1.04; 1.37) | 0.19 |

| VICON | 0.02 ± 0.21 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waldron, M.; Harding, J.; Barrett, S.; Gray, A. A new foot-mounted inertial measurement system in soccer: Reliability and comparison to global positioning systems for velocity measurements during team sport actions. J. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 77, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, A.; Martinho, D.V.; Valente-dos-Santos, J.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.J.; Teixeira, D.S. From data to action: A scoping review of wearable technologies and biomechanical assessments informing injury prevention strategies in sport. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.P.; Hopkinson, T.L.; Wundersitz, D.W.; Serpell, B.G.; Mara, J.K.; Ball, N.B. Validity of a wearable accelerometer device to Measure average acceleration values during high-speed running. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 3007–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.J.; Jenkins, D.G. Match analysis and the physiological demands of Australian football. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.D.; Black, G.M.; Harrison, P.W.; Murray, N.B.; Austin, D.J. Applied sport science of Australian football: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1673–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, A.; Cormack, S.; Morgan, S.; Aughey, R. When is a sprint a sprint? A review of the analysis of team-sport athlete activity profile. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, S.; Duthie, G.M.; Ball, K.; Spencer, B.; Serpiello, F.R.; Haycraft, J.; Evans, N.; Billingham, J.; Aughey, R.J. Challenges and considerations in determining the quality of electronic performance & tracking systems for team sports. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1266522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aughey, R.J.; Ball, K.; Robertson, S.J.; Duthie, G.M.; Serpiello, F.R.; Evans, N.; Spencer, B.; Ellens, S.; Cust, E.; Haycraft, J.; et al. Comparison of a computer vision system against three-dimensional motion capture for tracking football movements in a stadium environment. Sports Eng. 2022, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Mittal, V. Wearable sensors for real-time kinematics analysis in sports: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 1187–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Mohr, C.; Li, Q. Ambulatory running speed estimation using an inertial sensor. Gait Posture 2011, 34, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; Pearson, L.T.; Barry, G.; Young, F.; Lennon, O.; Godfrey, A.; Stuart, S. Wearables for running gait analysis: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, L.C.; Räisänen, A.M.; Clermont, C.A.; Ferber, R. Is this the real life, or is this just laboratory? A scoping review of IMU-based running gait analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooren, B.; Fuller, J.T.; Buckley, J.D.; Miller, J.R.; Sewell, K.; Rao, G.; Barton, C.; Bishop, C.; Willy, R.W. Is motorized treadmill running biomechanically comparable to overground running? A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-over studies. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 785–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roell, M.; Roecker, K.; Gehring, D.; Mahler, H.; Gollhofer, A. Player monitoring in indoor team sports: Concurrent validity of inertial measurement units to quantify average and peak acceleration values. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, F.; Mason, R.; Wall, C.; Morris, R.; Stuart, S.; Godfrey, A. Examination of a foot mounted IMU-based methodology for a running gait assessment. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 956889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weizman, Y.; Tirosh, O.; Fuss, F.K.; Tan, A.M.; Rutz, E. Recent state of wearable IMU sensors use in people living with spasticity: A systematic review. Sensors 2022, 22, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favata, A.; Gallart-Agut, R.; Pamies-Vila, R.; Torras, C.; Font-Llagunes, J.M. IMU-based systems for upper limb kinematic analysis in clinical applications: A systematic review. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 28576–28594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport Tech Research Network (STRN). Quality Frameworks for Sports Technologies; White Paper; STRN: Ghent, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S.; Zendler, J.; De Mey, K.; Haycraft, J.; Ash, G.I.; Brockett, C.; Seshadri, D.; Woods, C.; Kober, L.; Aughey, R.; et al. Development of a sports technology quality framework. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 1983–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sports Tech Research Network (STRN). Quality Assessment Framework. Bringing the Framework to Life; STRN: Ghent, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Myhill, N.; Weaving, D.; Robinson, M.; Barrett, S.; Emmonds, S. Concurrent validity and between-unit reliability of a foot-mounted inertial measurement unit to measure velocity during team sport activity. Sci. Med. Footb. 2024, 8, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VICON. Lower Body Modeling with Plug-In Gait; VICON: Oxford, UK, 2024; Available online: https://help.vicon.com/space/Nexus216/11605140/Lower+body+modeling+with+Plug-in+Gait (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Davies, R.; Sweeting, A.J.; Robertson, S. Concurrent validation of foot-mounted inertial measurement units for quantifying Australian Rules football kicking. Sci. Med. Footb. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PlayerMakerTM. Playermaker 2.0 Smart Soccer Tracker. PlayerMakerTM: Tel Aviv, Israel. Available online: https://au.playermaker.com/products/playermaker-2-0/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Colyer, S.L.; Nagahara, R.; Salo, A.I.T. Kinetic demands of sprinting shift across the acceleration phase: Novel analysis of entire force waveforms. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.B.; Bourdin, M.; Edouard, P.; Peyrot, N.; Samozino, P.; Lacour, J.R. Mechanical determinants of 100-m sprint running performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 3921–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Hester, J.; Bryan, J. readr: Read Rectangular Text Data. R Package Version 2.1.4. 2023. Available online: https://readr.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Zeileis, A.G.; Grothendieck, G.; Ryan, J.A. zoo: S3 Infrastructure for Regular and Irregular Time Series. R Package Version 1.8-12. 2023. Available online: https://zoo.R-Forge.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Tyson, B.; Dowle, M.; Srinivasan, A.; Gorecki, J.; Chirico, M.; Hocking, T.; Schwendinger, B.; Krylov, I. data.table: Extension of ‘data.frame’. R Package Version 1.14.8. 2023. Available online: https://r-datatable.com (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Vaughan, D.; Girlich, M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data. R Package Version 1.3.0. 2023. Available online: https://tidyr.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R Package Version 1.1.0. 2023. Available online: https://dplyr.tidyverse.org (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Ligges, U.; Short, T. signal: Signal Processing. R Package Version 1.8-0. 2023. Available online: https://signal.r-forge.r-project.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Van Oeveren, B.T.; de Ruiter, C.J.; Beek, P.J.; van Dieën, J.H. The biomechanics of running and running styles: A synthesis. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 516–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, D.S.; Schuster, J.G.; Samozino, P.; Morin, J.-B. Improving mechanical effectiveness during sprint acceleration: Practical recommendations and guidelines. Strength Cond. J. 2020, 42, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuszynski, J. caTools: Tools: Moving Window Statistics, GIF, Base64, ROC AUC, etc. R Package Version 1.18.2. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/cran/caTools (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Crang, Z.L.; Duthie, G.; Cole, M.H.; Weakley, J.; Hewitt, A.; Johnston, R.D. The validity of raw custom-processed global navigation satellite systems data during straight-line sprinting across multiple days. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2024, 27, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D.; van den Brand, T. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. R Package Version 3.5.1. 2016. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Chang, W.; Cheng, J.; Allaire, J.J.; Sievert, C.; Schloerke, B.; Xie, Y.; Allen, J.; McPherson, J.; Dipert, A.; Borges, B. shiny: Web Application Framework for R. R Package Version 1.10.0. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/rstudio/shiny (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Sievert, C.; Parmer, C.; Hocking, T.; Chamberlain, S.; Ram, K.; Corvellec, M.; Despouy, P. plotly: Create Interactive Web Graphics via ‘plotly.js’. R Package Version 4.10.4. 2024. Available online: https://plotly-r.com/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Wickham, H. tidyverse: Easily Install and Load the ‘Tidyverse’. R Package Version 2.0.0. 2023. Available online: https://tidyverse.tidyverse.org (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Chen, C.-C.; Barnhart, H.X. Comparison of ICC and CCC for assessing agreement for data without and with replications. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2008, 53, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Pearson’s correlation coefficient. BMJ 2012, 345, e4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. A Scale of Magnitudes for Effect Statistics: A New View of Statistics. 2002. Available online: https://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/effectmag.html (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Giavarina, D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem. Med. 2015, 25, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K.L. irrICC: Intraclass Correlations for Quantifying Inter-Rater Reliability. R Package Version 1.0. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/cran/irrICC (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Hothorn, T.; Zeileis, A.; Farebrother, R.; Cummins, C. lmtest: Testing Linear Regression Models. R Package Version 0.9-40. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmtest/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Atkinson, G.; Nevill, A.M. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998, 26, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahakone, A.U.; Senanayake, S.M.N.A.; Senanayake, C.M. Smart wearable device for real time gait event detection during running. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Circuits and Systems, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 6–9 December 2010; pp. 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal Pla, G.; Martini, D.N.; Potter, M.V.; Hoogkamer, W. Assessing the validity of the zero-velocity update method for sprinting speeds. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0288896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Du, S.; Jin, L.; Chen, F.; Wu, T. A miniaturized MEMS accelerometer with anti-spring mechanism for enhancing sensitivity. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Z.; Elfadel, I.A.M.; Rasras, M. Monolithic Multi Degree of Freedom (MDoF) capacitive MEMS accelerometers. Micromachines 2018, 9, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruiter, C.J.; Wilmes, E.; van Ardenne, P.S.; Houtkamp, N.; Prince, R.A.; Wooldrik, M.; van Dieën, J.H. Stride lengths during maximal linear sprint acceleration Obtained with foot-mounted inertial measurement units. Sensors 2022, 22, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahms, C.M.; Zhao, Y.; Gerhard, D.; Barden, J.M. Stride length determination during overground running using a single foot-mounted inertial measurement unit. J. Biomech. 2018, 71, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falbriard, M.; Meyer, F.; Mariani, B.; Millet, G.P.; Aminian, K. Accurate estimation of running temporal parameters using foot-worn inertial sensors. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrenner, M.; Küderle, A.; Roth, N.; Jensen, U.; Dümler, B.; Eskofier, B.M. Does the position of foot-mounted IMU sensors influence the accuracy of spatio-temporal parameters in endurance running? Sensors 2020, 20, 5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsley, B.J.; Tofari, P.J.; Halson, S.L.; Kemp, J.G.; Dickson, J.; Maniar, N.; Cormack, S.J. Does site matter? Impact of inertial measurement unit placement on the validity and reliability of stride variables during running: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 1449–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, G.P.; Harle, R.K. (Eds.) Measuring temporal parameters of gait with foot mounted IMUs in steady state running. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support (icSPORTS), Lisbon, Portugal, 15–17 November 2015; SciTePress: Setúbal, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini, E.; Picerno, P.; Pillet, H.; Natta, F.; Thoreux, P.; Camomilla, V. Estimation of temporal parameters during sprint running using a trunk-mounted inertial measurement unit. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 1123–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneally-Dabrowski, C.J.; Serpell, B.G.; Spratford, W. Are accelerometers a valid tool for measuring overground sprinting symmetry? Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2018, 13, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenna, F.; Rossi, G.B.; Berardengo, M. Filtering biomechanical signals in movement analysis. Sensors 2021, 21, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants | Sport | Trials (n) | Left Strides (n) | Right Strides (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VFLW | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| 2 | VFLW | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 3 | VFLW | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 4 | VFL | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| 5 | VFLW | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 6 | AFLW | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 7 | VFLW | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 8 | VFLW | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| 9 | AFLW | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 10 | AFL | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 11 | VFL | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 12 | VFL | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| 13 | VFLW | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 14 | VFLW | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| 15 | VFLW | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 16 | Track and field | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| 17 | AFLW | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 18 | AFLW | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 19 | VFLW | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 20 | A-League Academy | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 21 | A-League Academy | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 22 | A-League Academy | 4 | 8 | 4 |

| 23 | A-League Academy | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Total | 92 | 132 | 133 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dasso, M.; Duthie, G.; Robertson, S.; Haycraft, J. Quality Assessment of a Foot-Mounted Inertial Measurement Unit System to Measure On-Field Spatiotemporal Acceleration Metrics. Sensors 2026, 26, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010246

Dasso M, Duthie G, Robertson S, Haycraft J. Quality Assessment of a Foot-Mounted Inertial Measurement Unit System to Measure On-Field Spatiotemporal Acceleration Metrics. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010246

Chicago/Turabian StyleDasso, Marco, Grant Duthie, Sam Robertson, and Jade Haycraft. 2026. "Quality Assessment of a Foot-Mounted Inertial Measurement Unit System to Measure On-Field Spatiotemporal Acceleration Metrics" Sensors 26, no. 1: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010246

APA StyleDasso, M., Duthie, G., Robertson, S., & Haycraft, J. (2026). Quality Assessment of a Foot-Mounted Inertial Measurement Unit System to Measure On-Field Spatiotemporal Acceleration Metrics. Sensors, 26(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010246