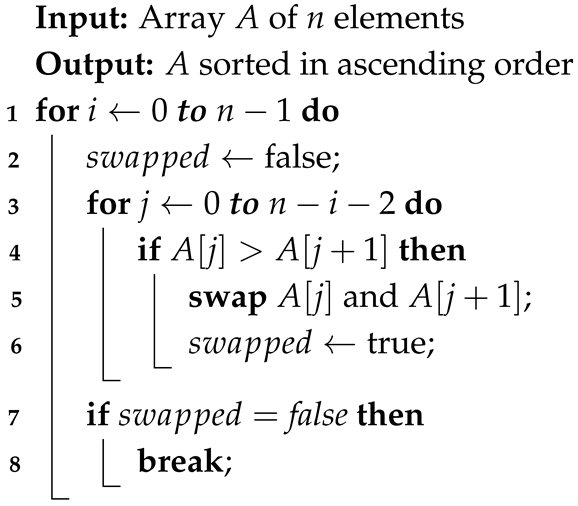

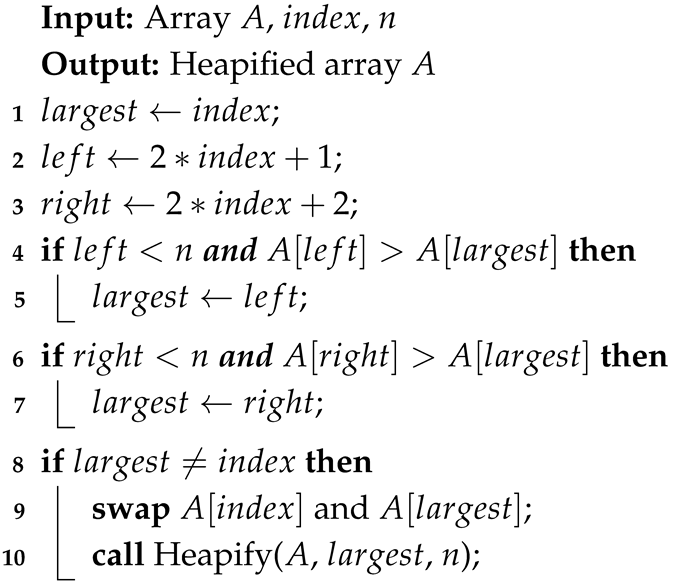

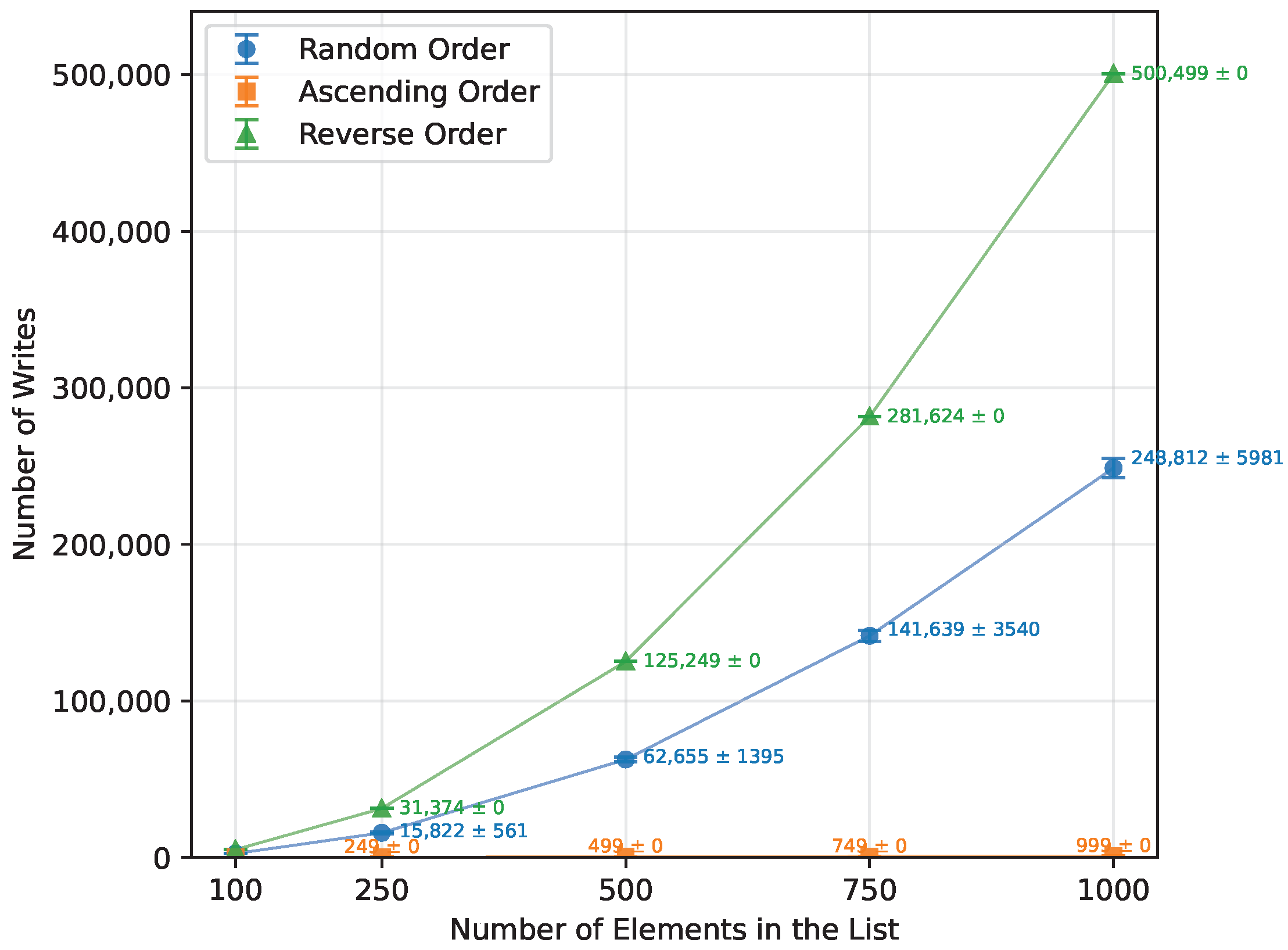

Figure 1.

Bubble Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 1.

Bubble Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

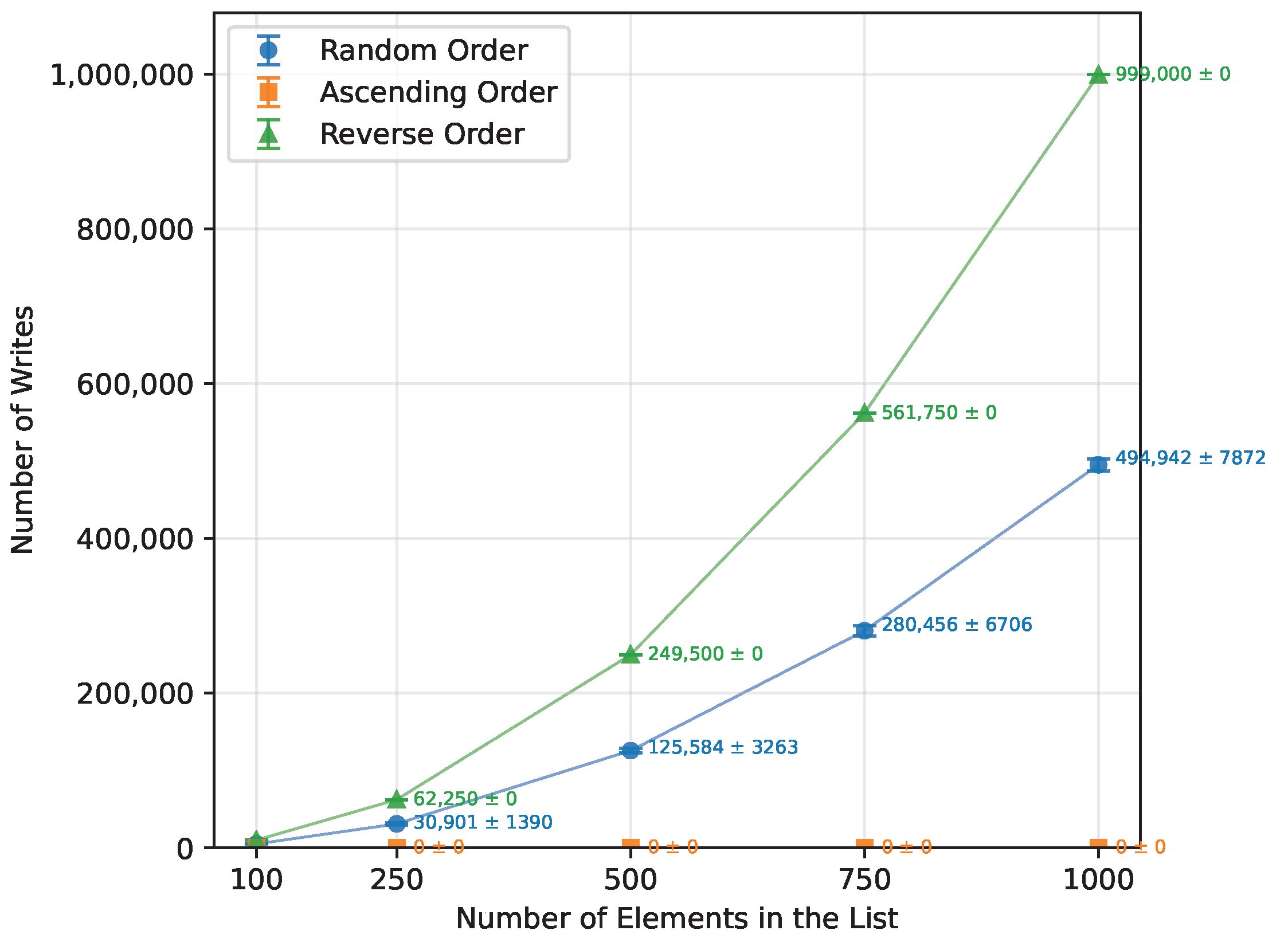

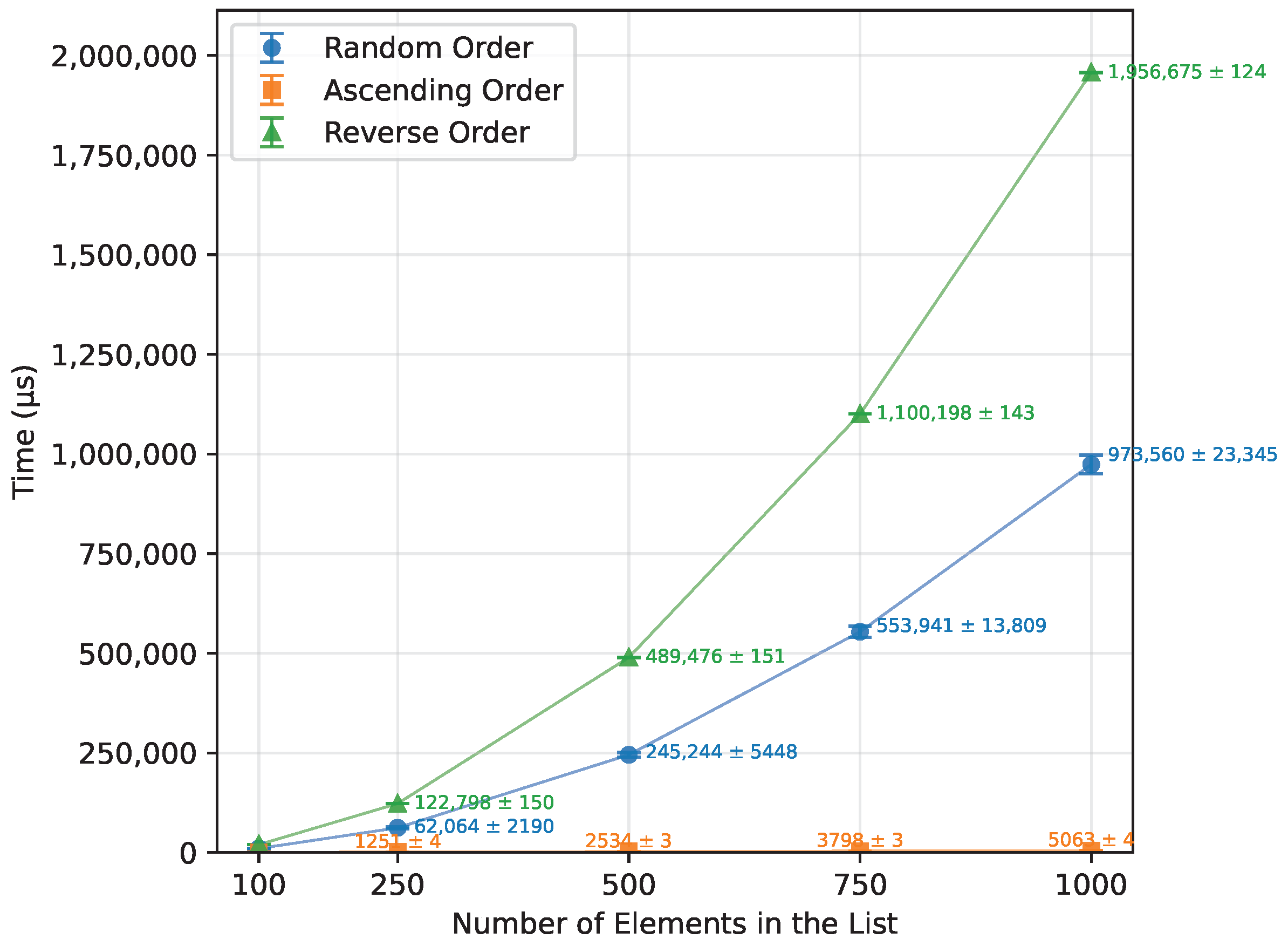

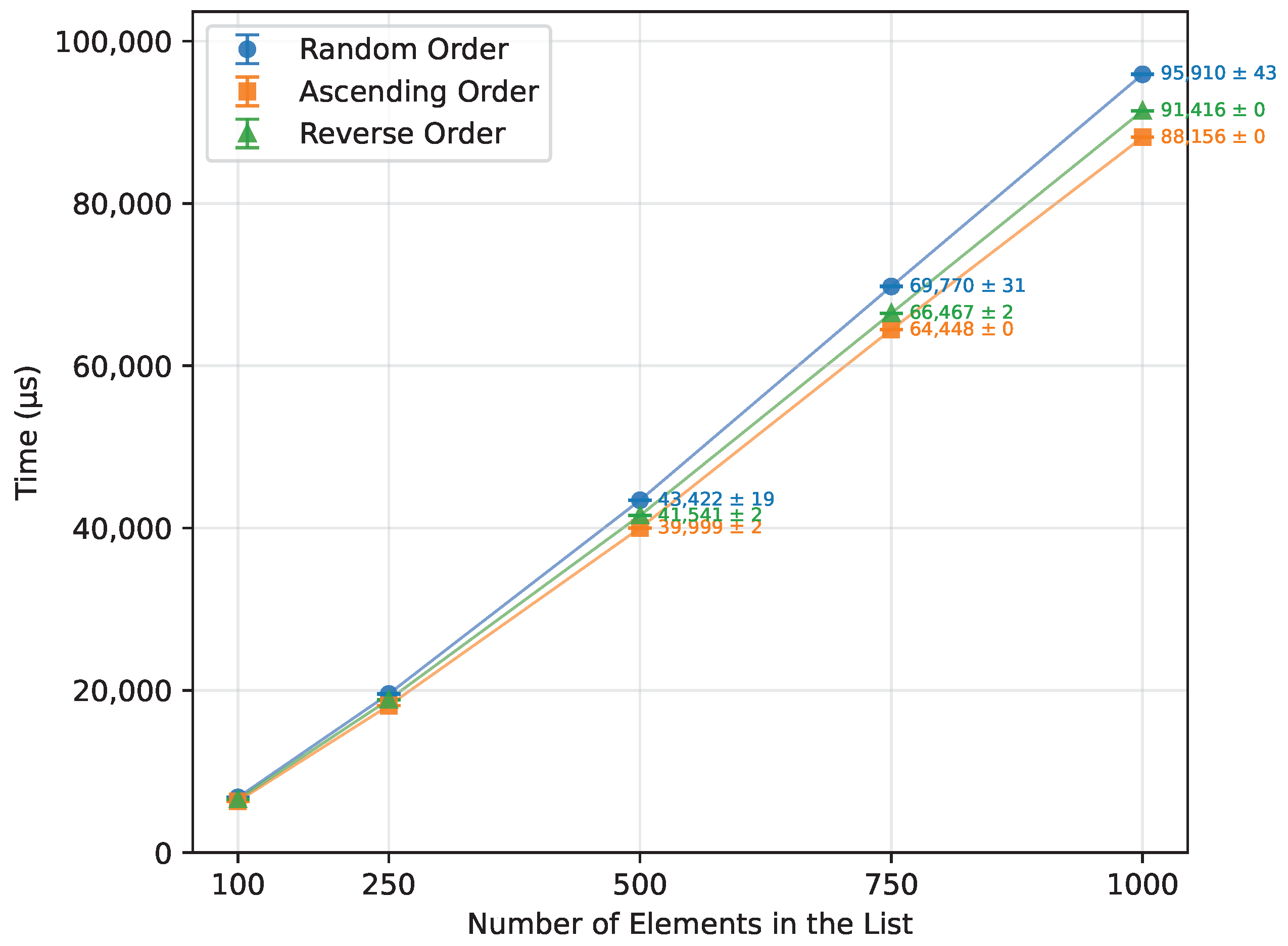

Figure 2.

Bubble Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 2.

Bubble Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

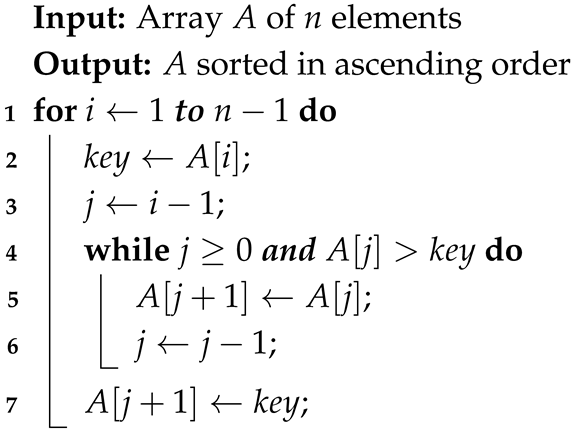

Figure 3.

Insertion Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 3.

Insertion Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 4.

Insertion Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 4.

Insertion Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

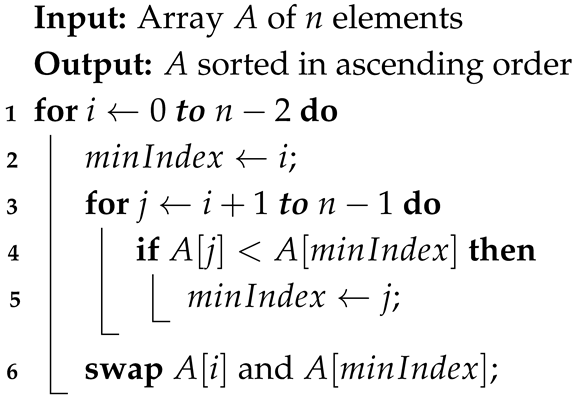

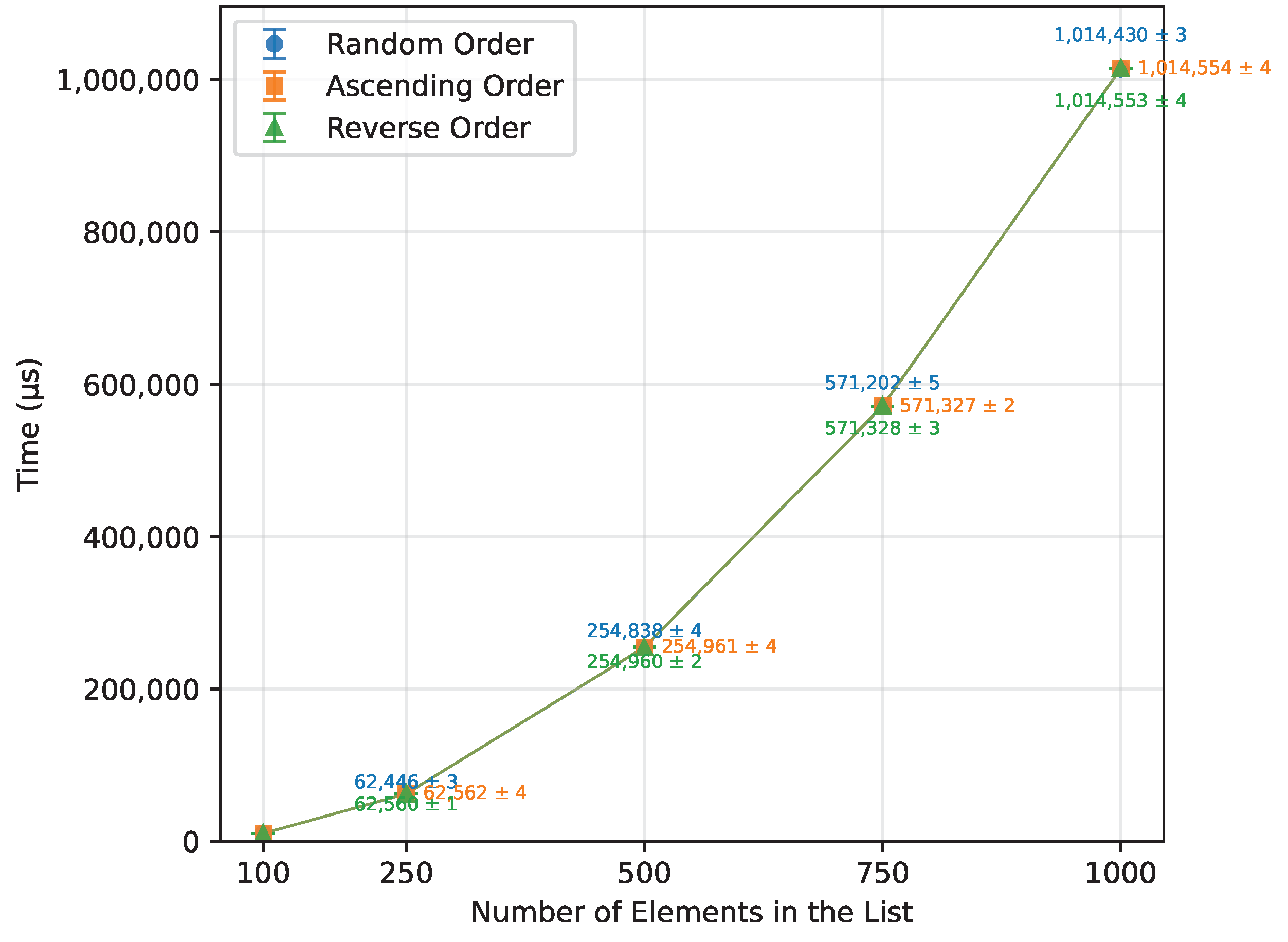

Figure 5.

Selection Sort runtime vs array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 5.

Selection Sort runtime vs array size (averaged across boards).

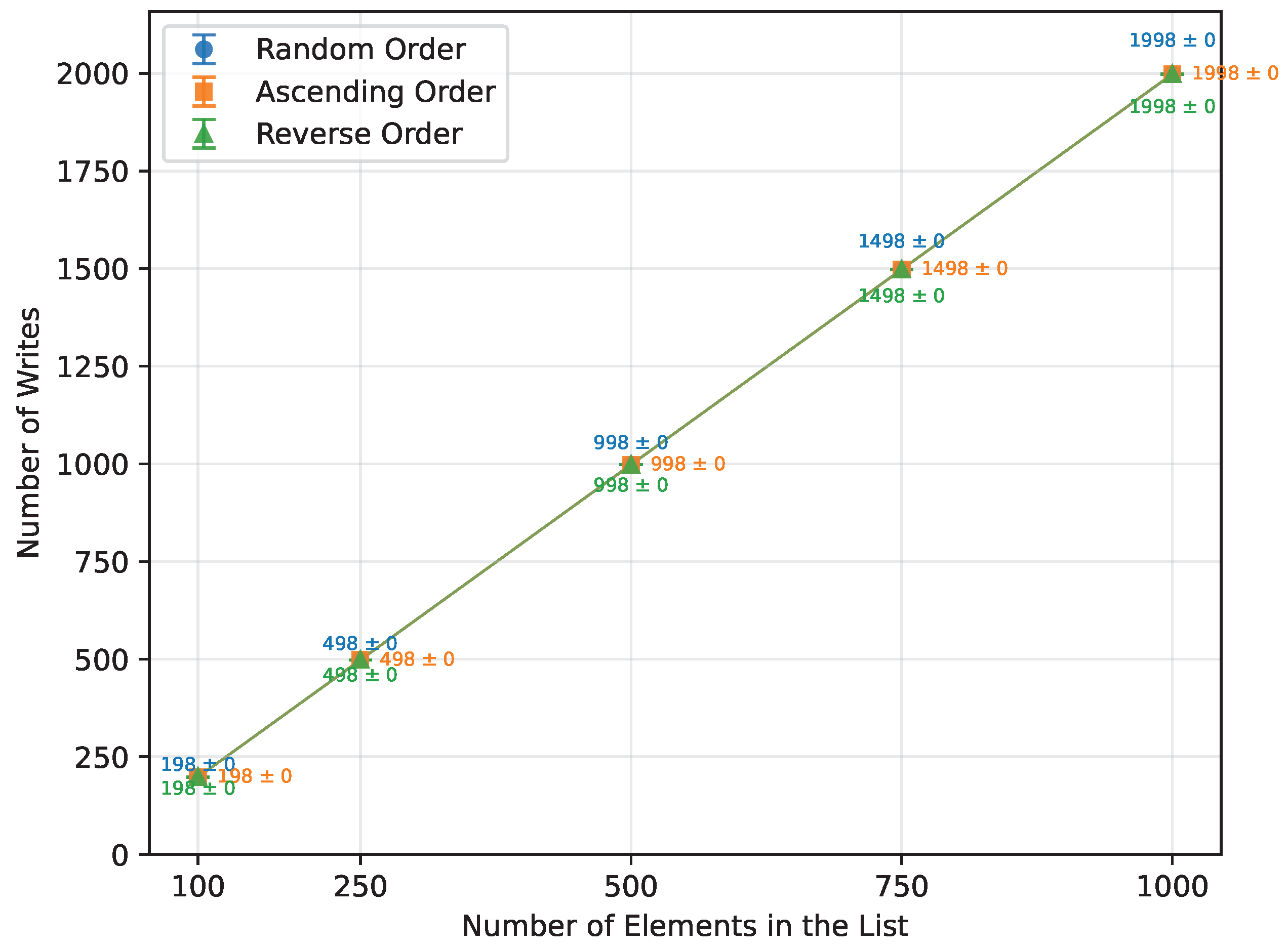

Figure 6.

Selection Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 6.

Selection Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

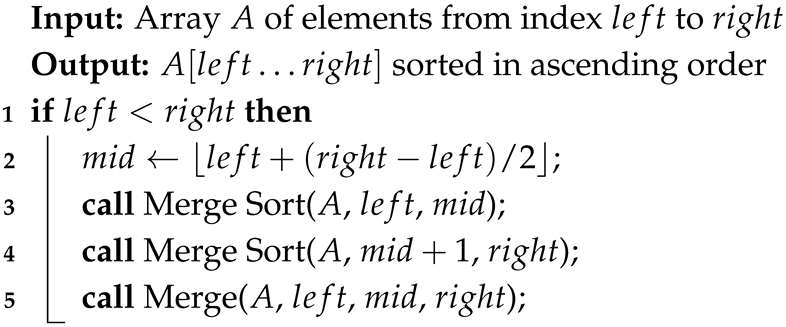

Figure 7.

Merge Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 7.

Merge Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

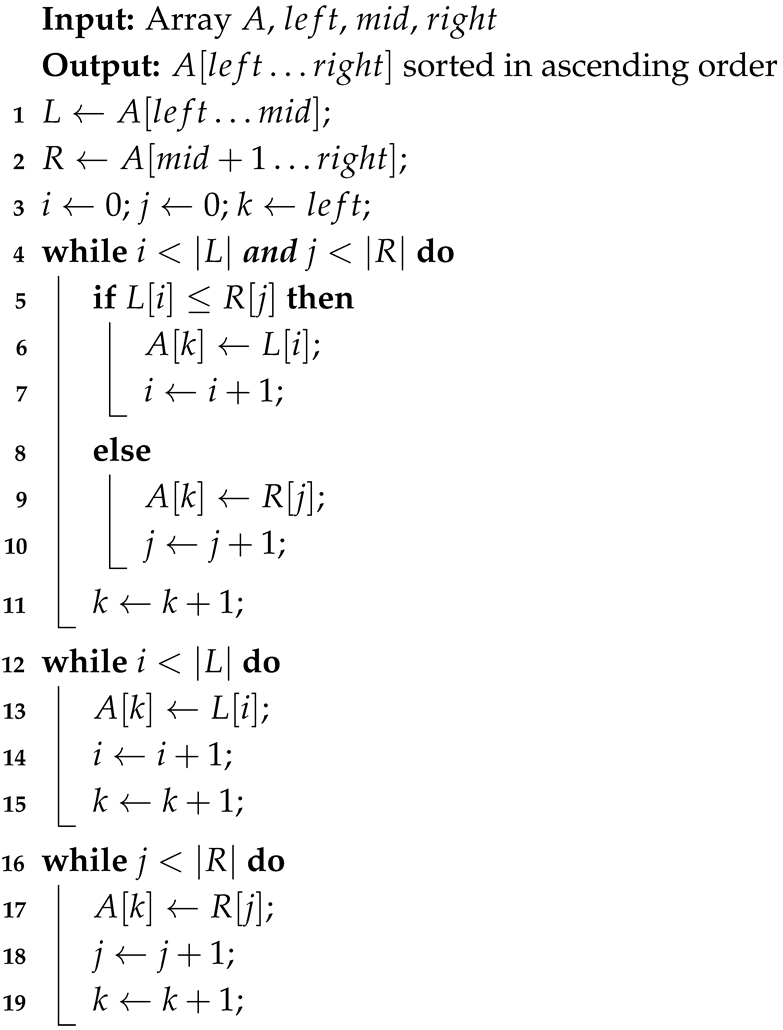

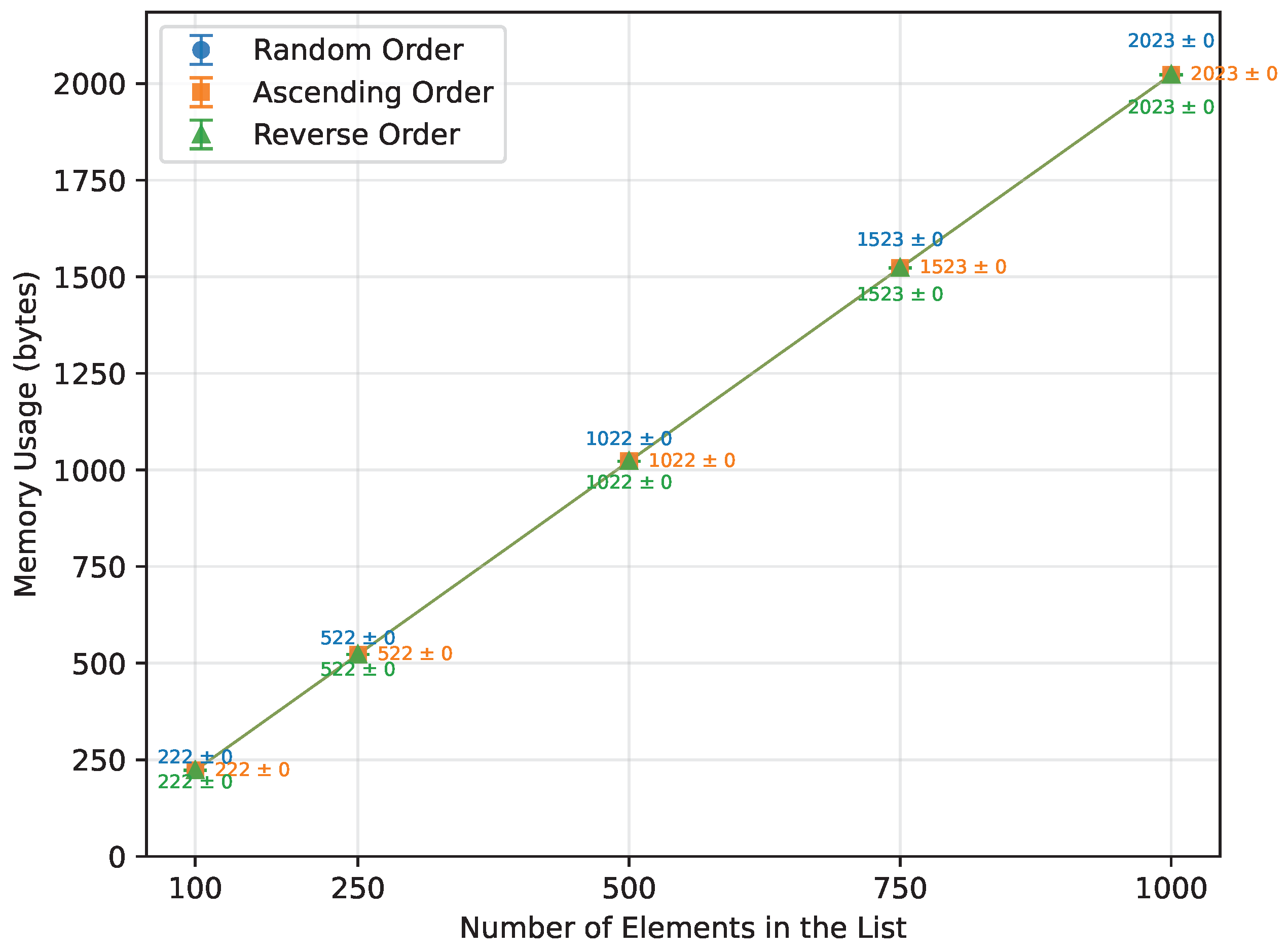

Figure 8.

Merge Sort memory usage vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 8.

Merge Sort memory usage vs. array size (averaged across boards).

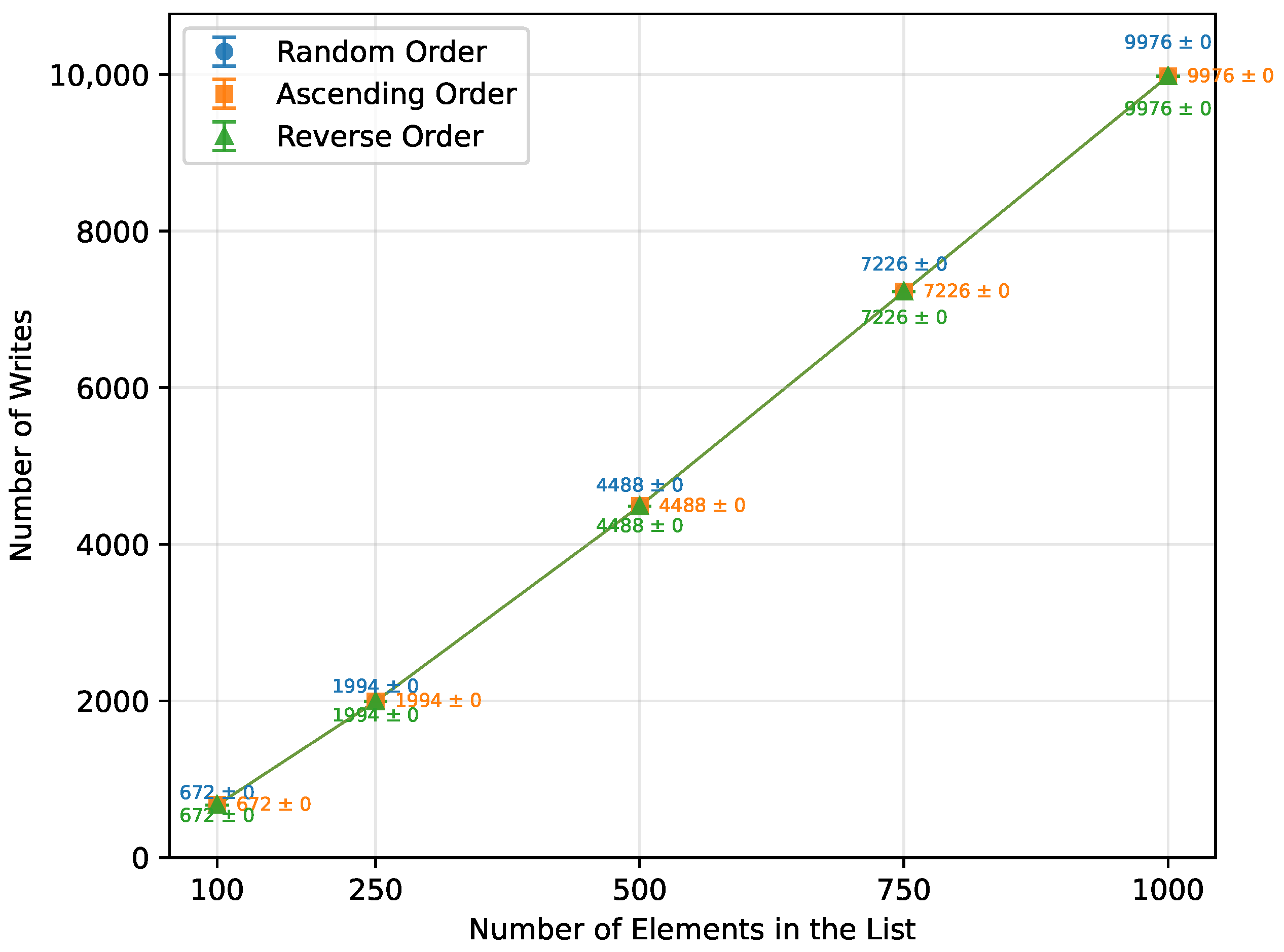

Figure 9.

Merge Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 9.

Merge Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

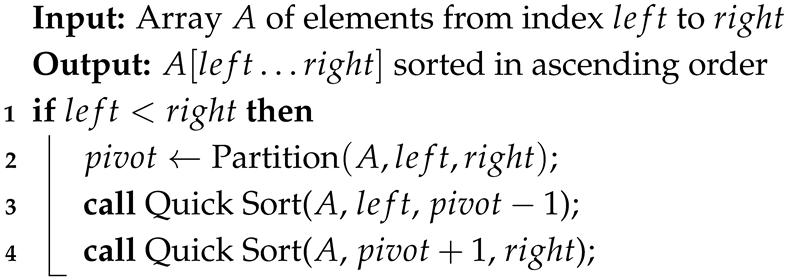

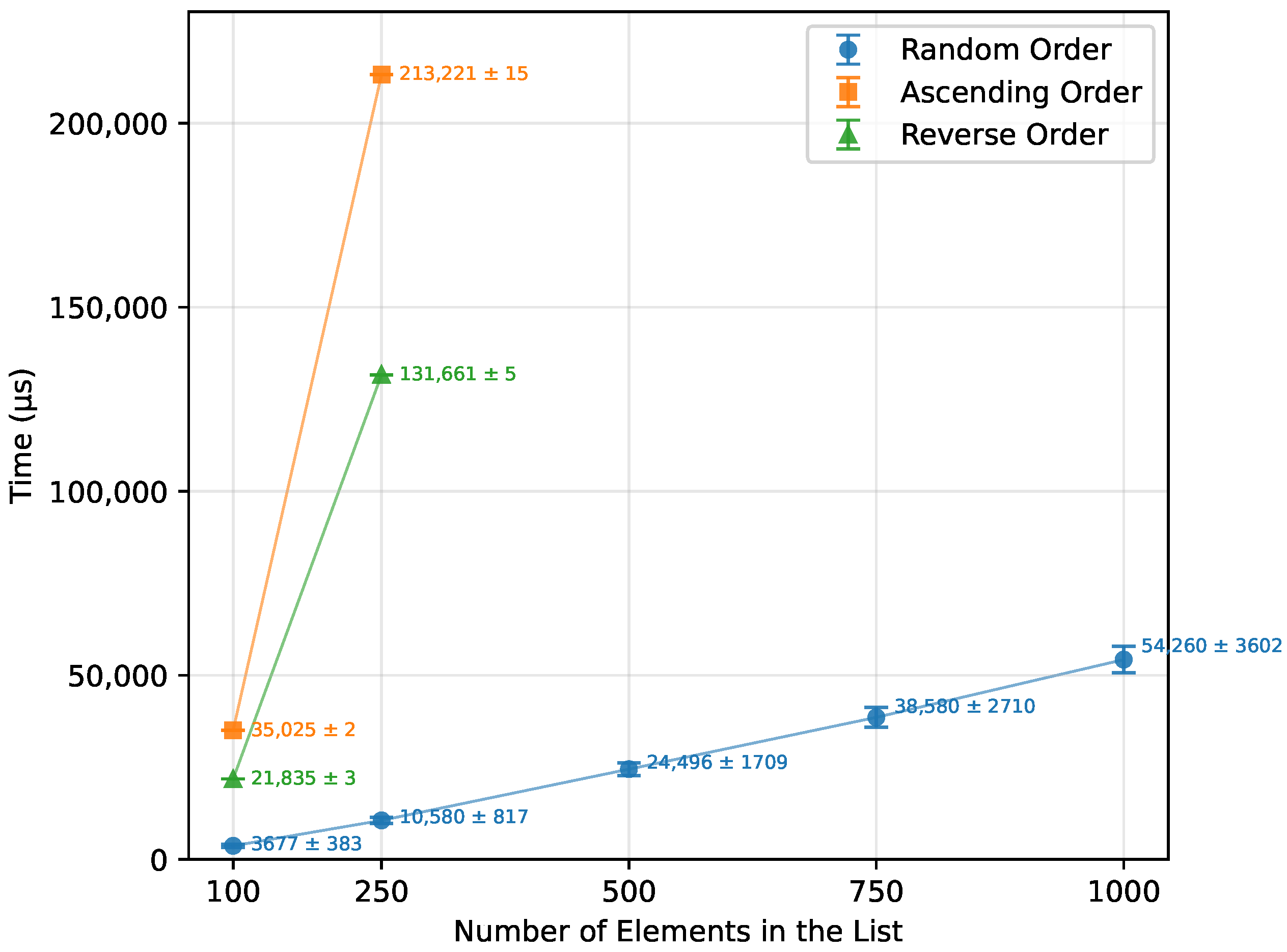

Figure 10.

Quick Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 10.

Quick Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

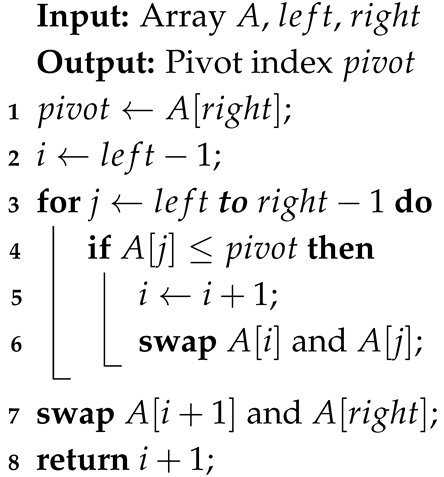

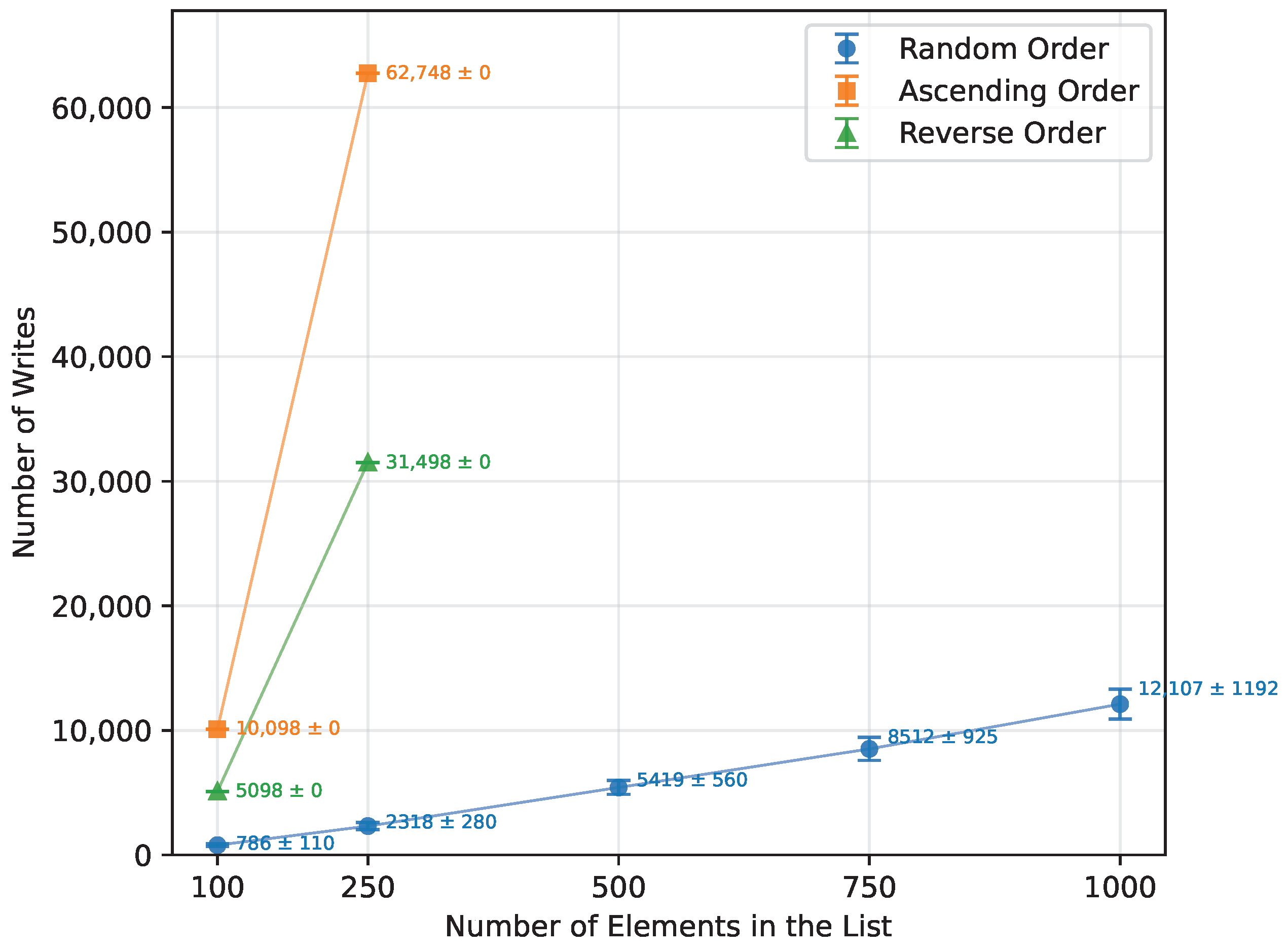

Figure 11.

Quick Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 11.

Quick Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

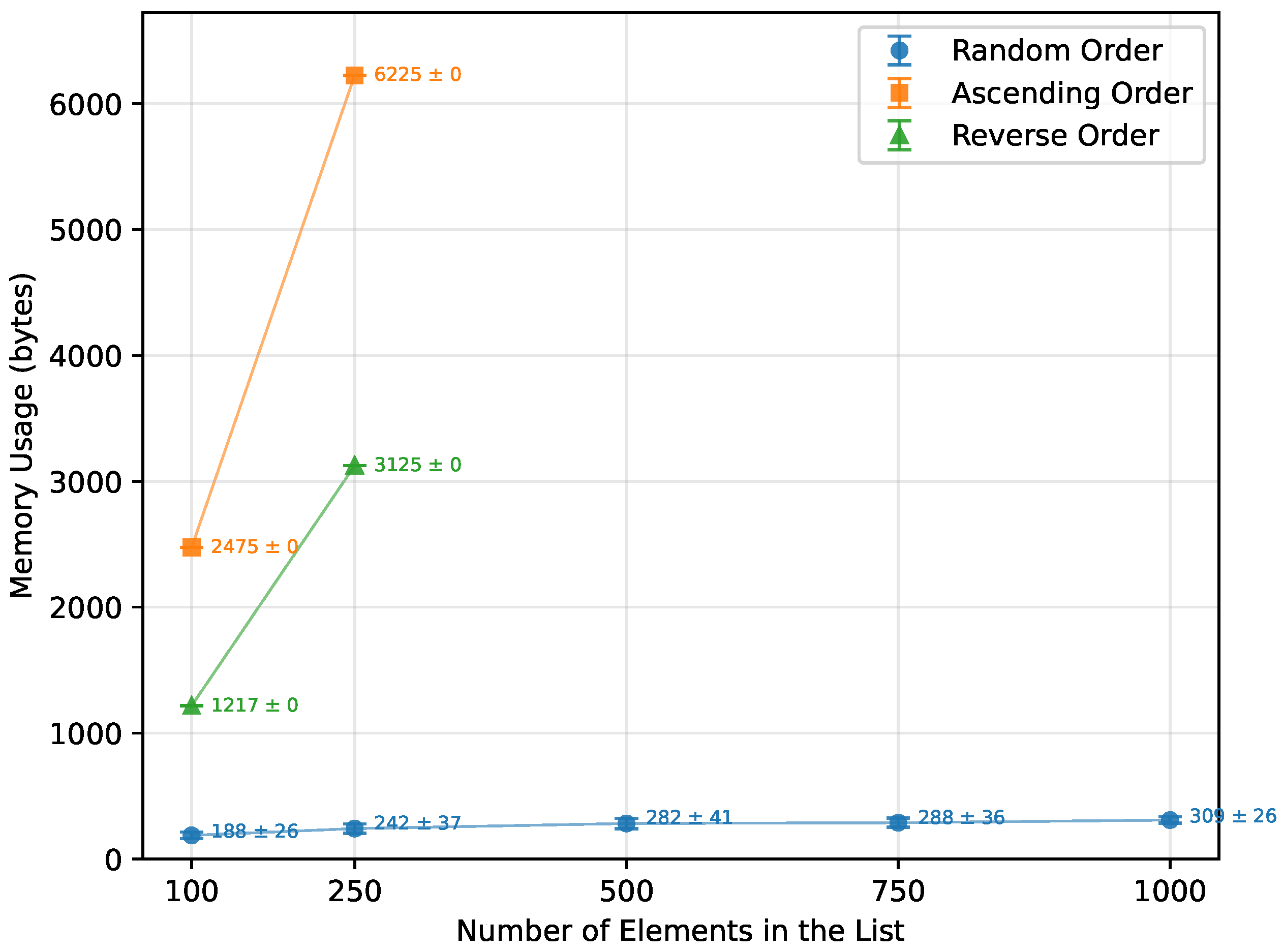

Figure 12.

Quick Sort memory usage vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 12.

Quick Sort memory usage vs. array size (averaged across boards).

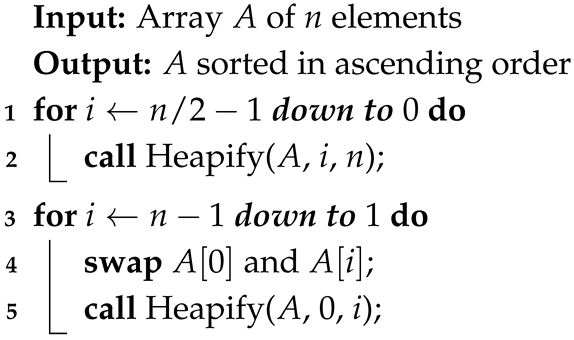

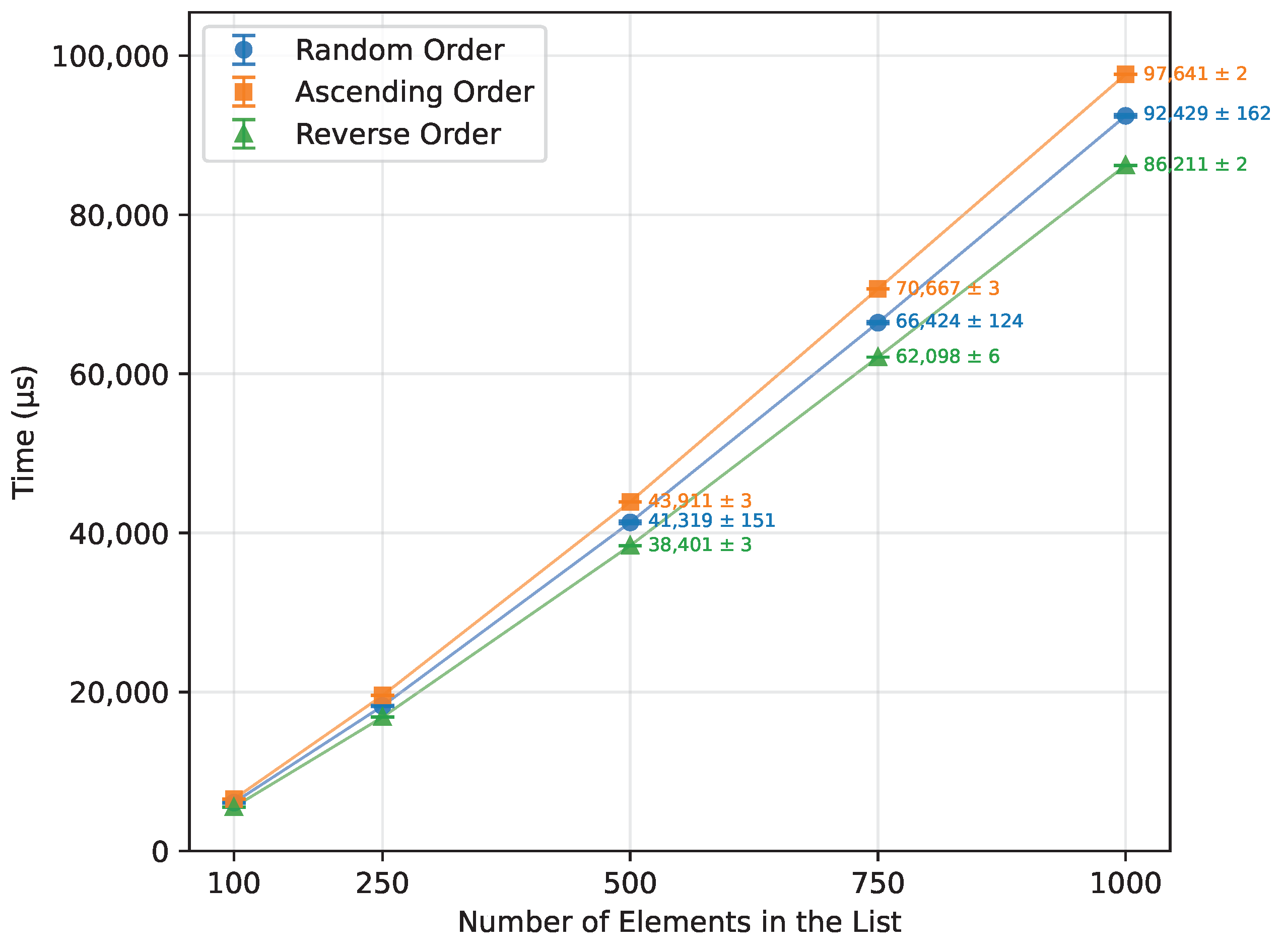

Figure 13.

Heap Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 13.

Heap Sort runtime vs. array size (averaged across boards).

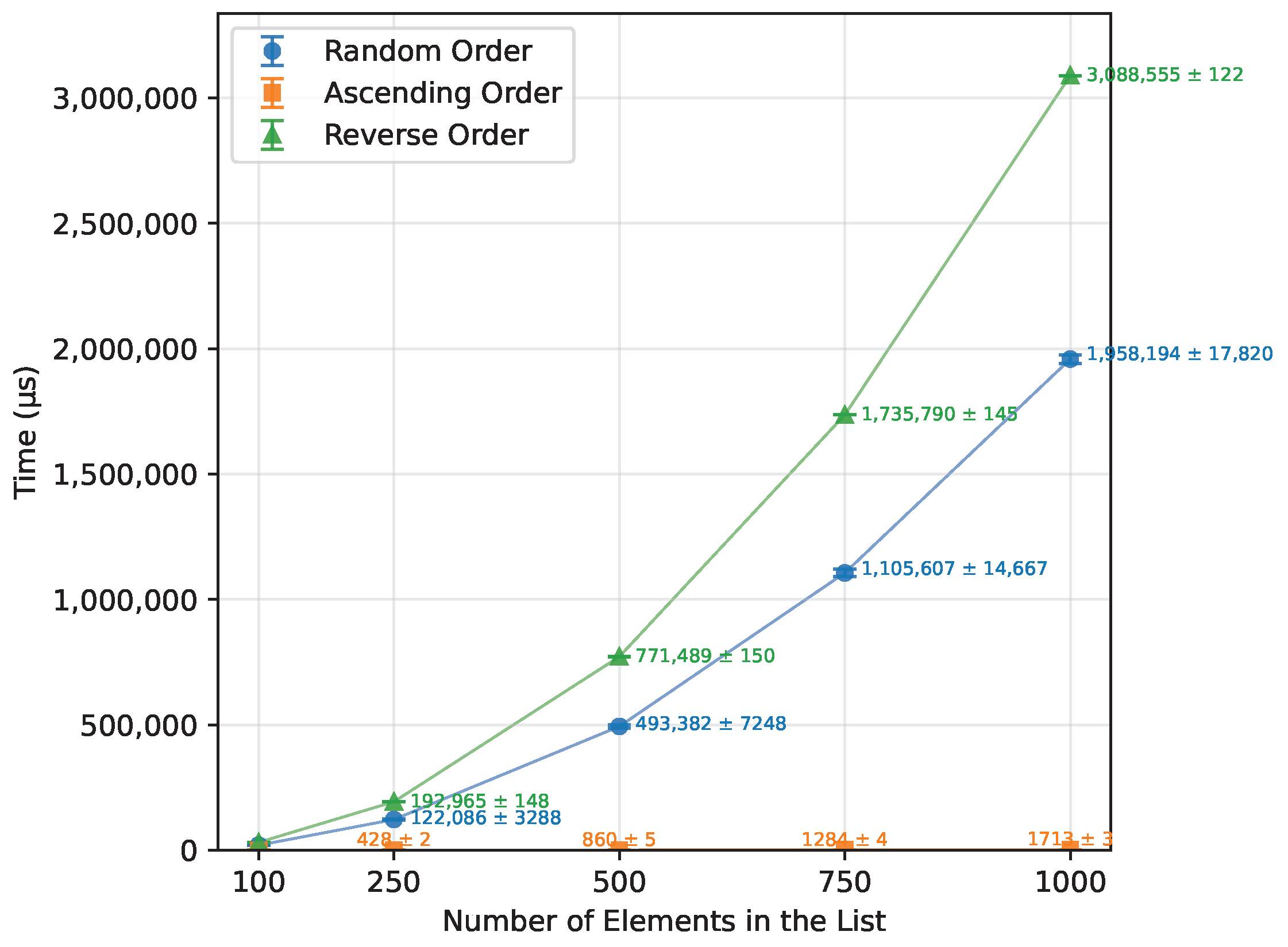

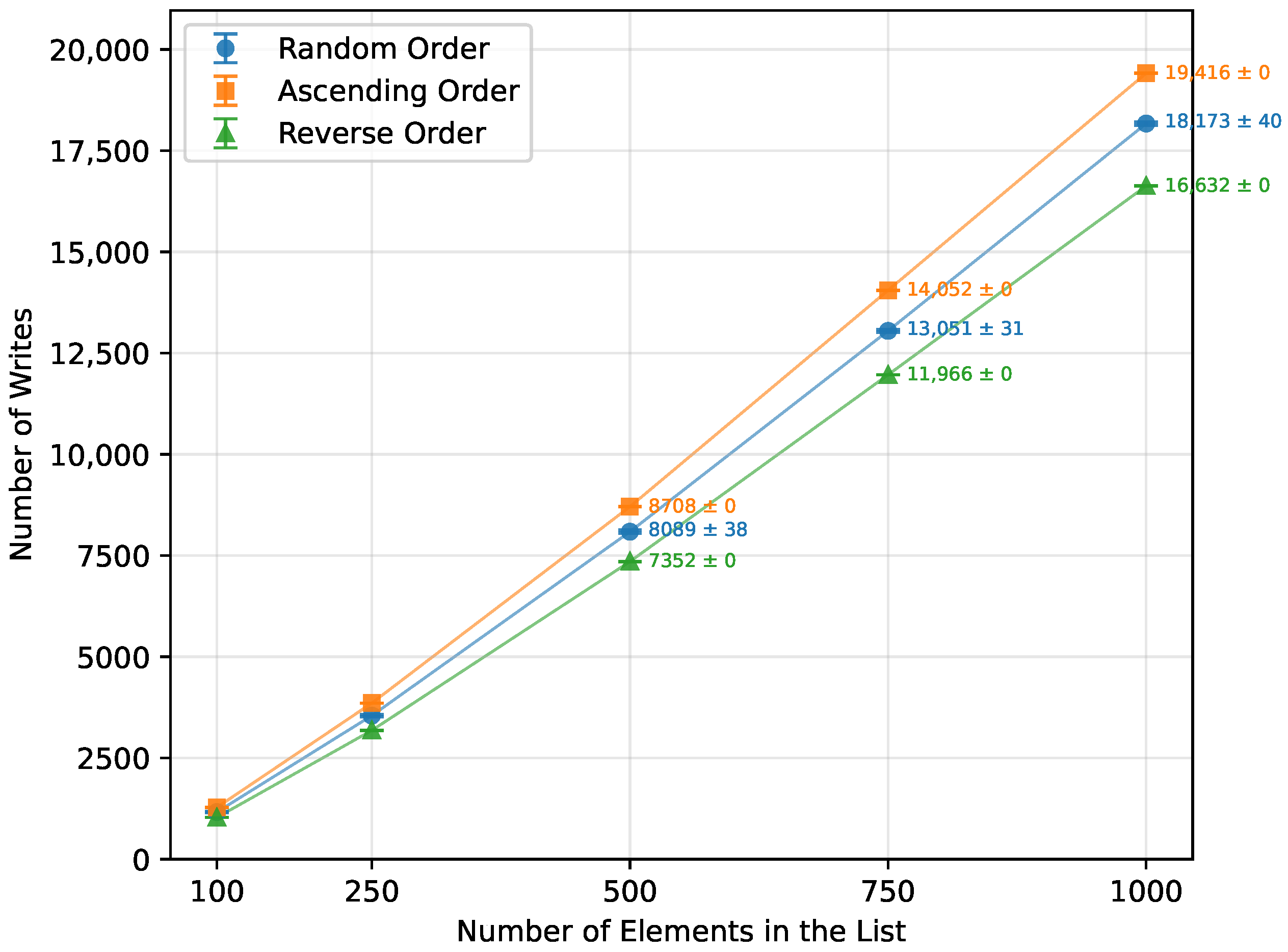

Figure 14.

Heap Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

Figure 14.

Heap Sort number of writes vs. array size (averaged across boards).

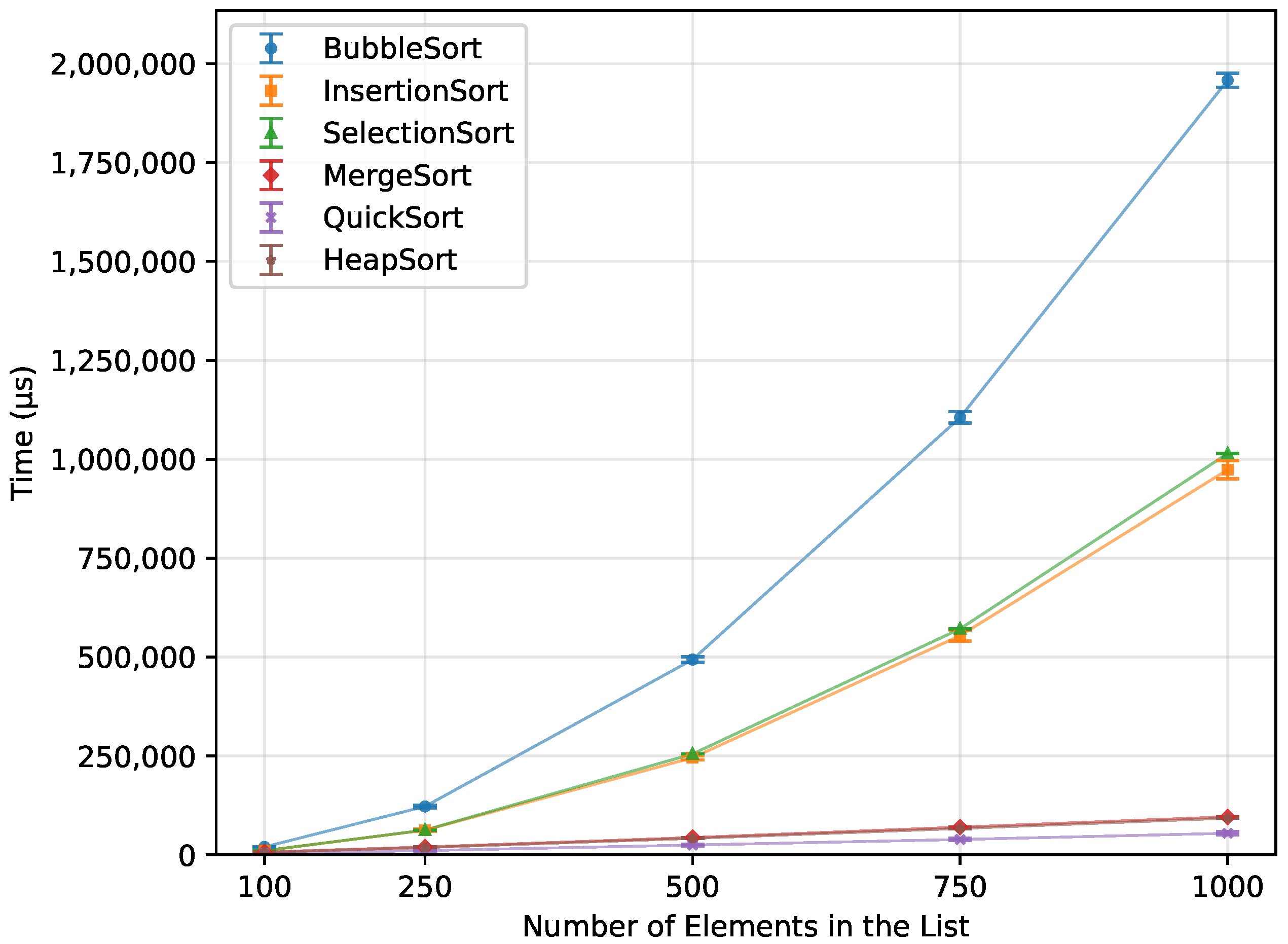

Figure 15.

Execution time of all algorithms vs. array size for random-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 15.

Execution time of all algorithms vs. array size for random-order inputs (averaged across boards).

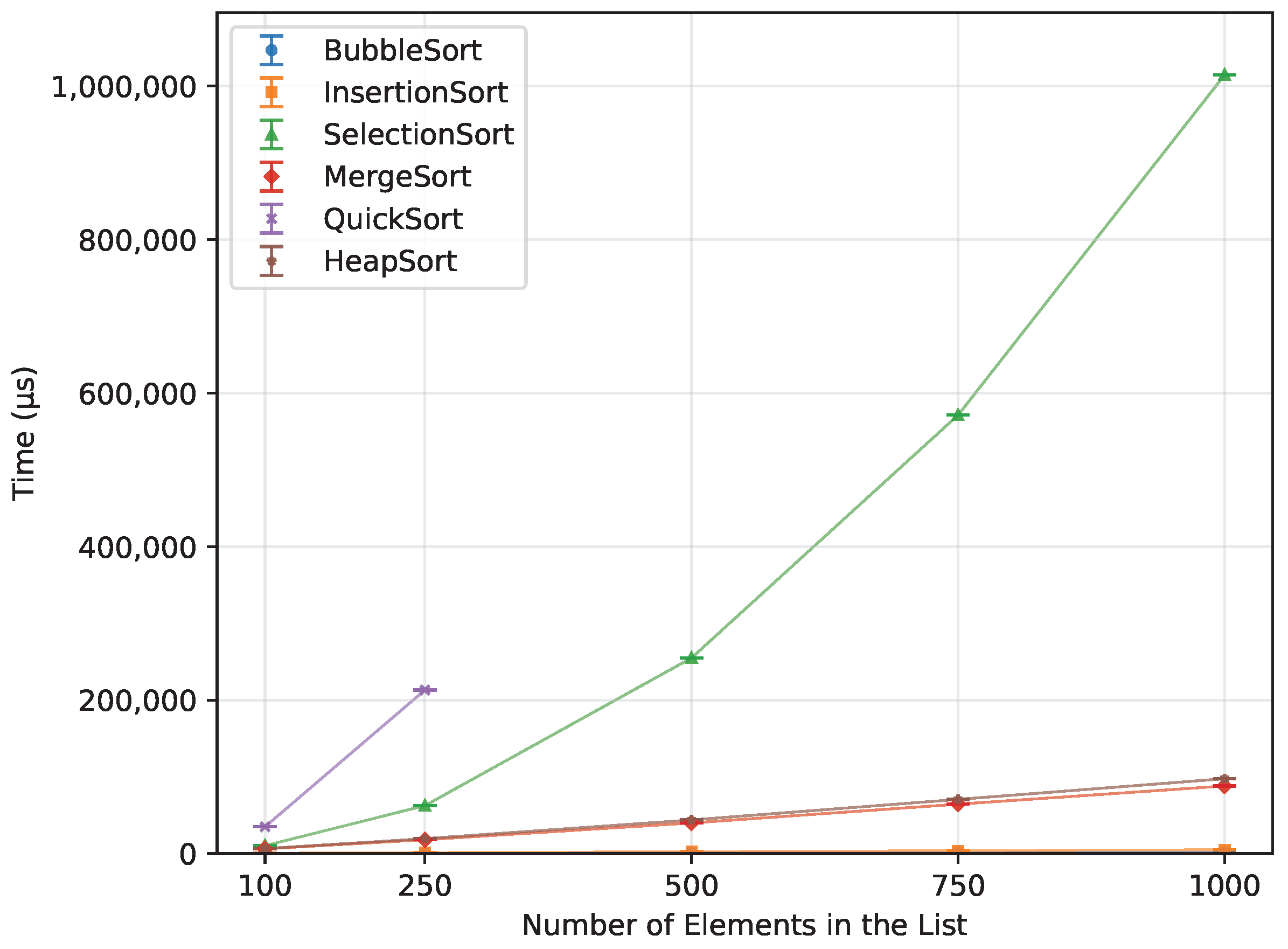

Figure 16.

Execution time of all algorithms vs. array size for ascending-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 16.

Execution time of all algorithms vs. array size for ascending-order inputs (averaged across boards).

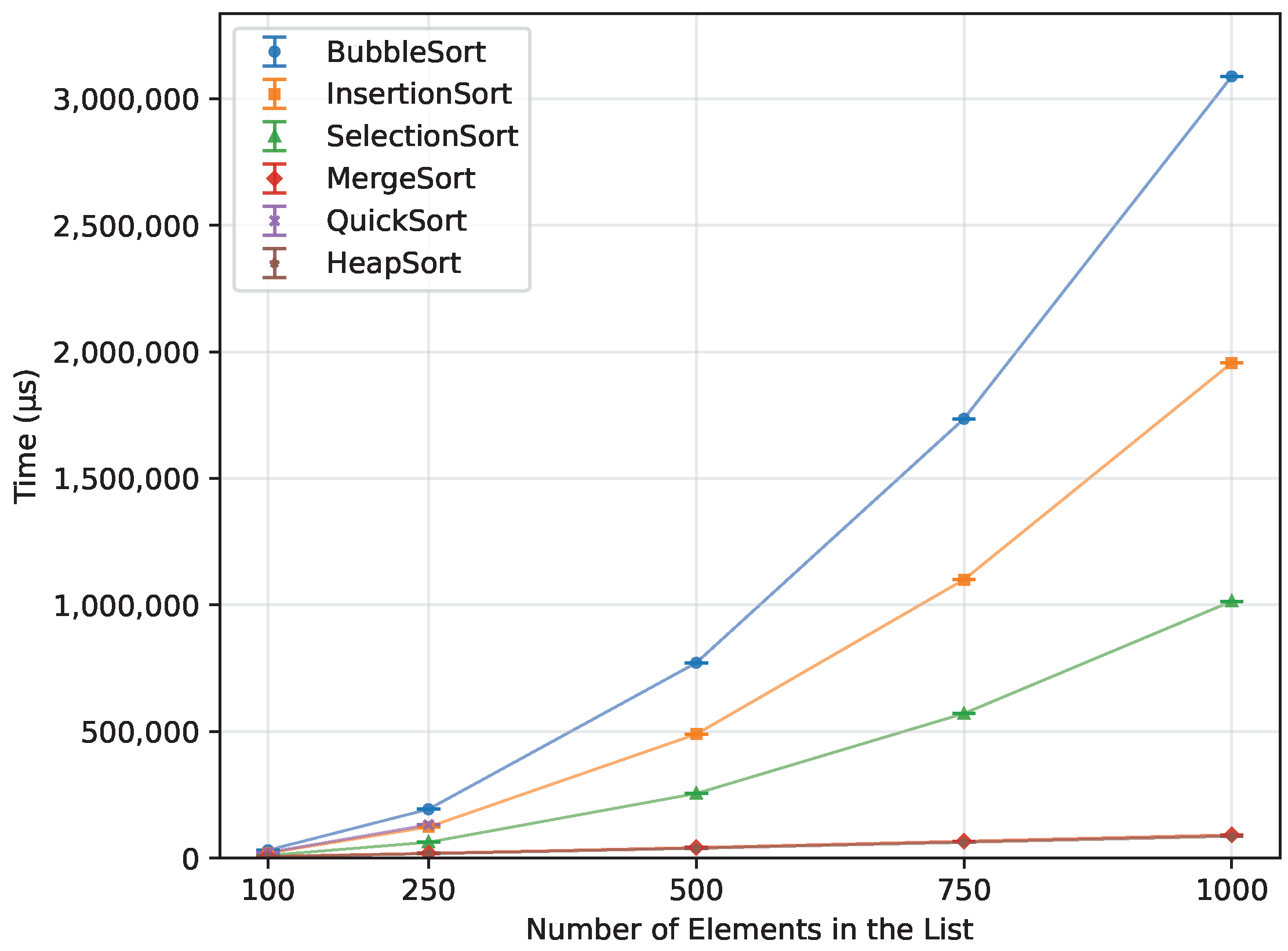

Figure 17.

Execution time of all algorithms vs. array size for reverse-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 17.

Execution time of all algorithms vs. array size for reverse-order inputs (averaged across boards).

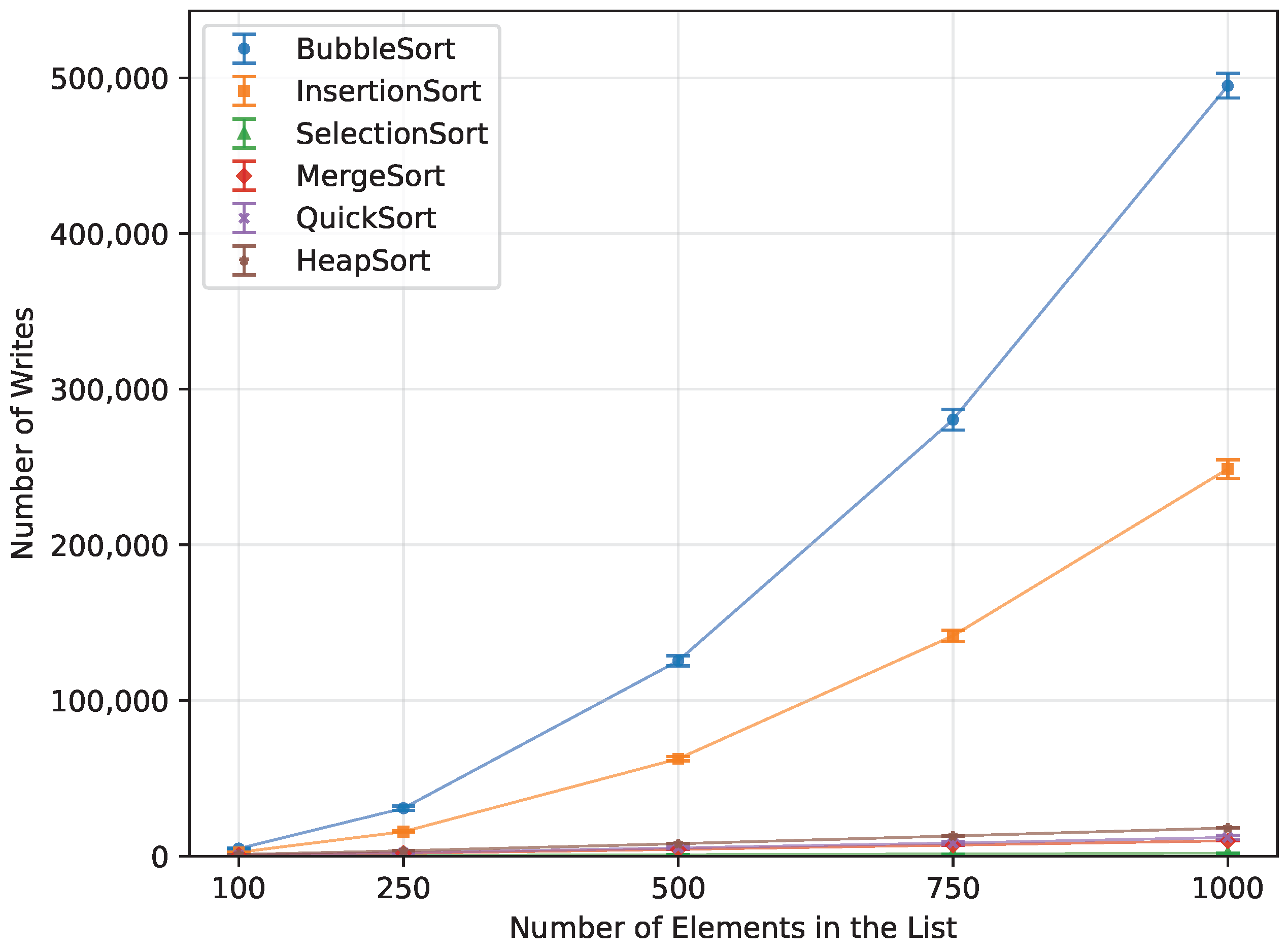

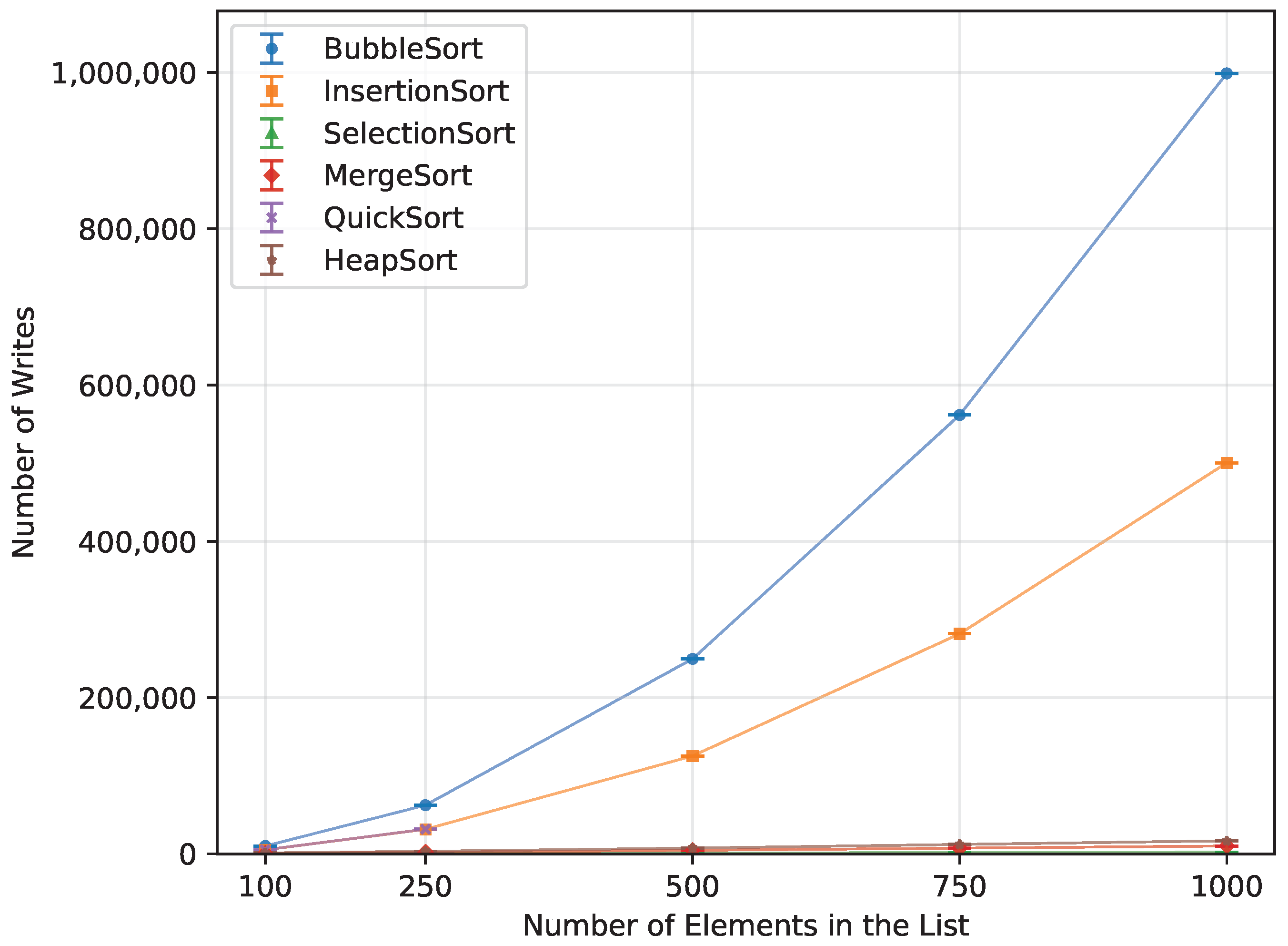

Figure 18.

Number of array-element writes for all algorithms vs. array size for random-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 18.

Number of array-element writes for all algorithms vs. array size for random-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 19.

Number of array-element writes for all algorithms vs. array size for ascending-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 19.

Number of array-element writes for all algorithms vs. array size for ascending-order inputs (averaged across boards).

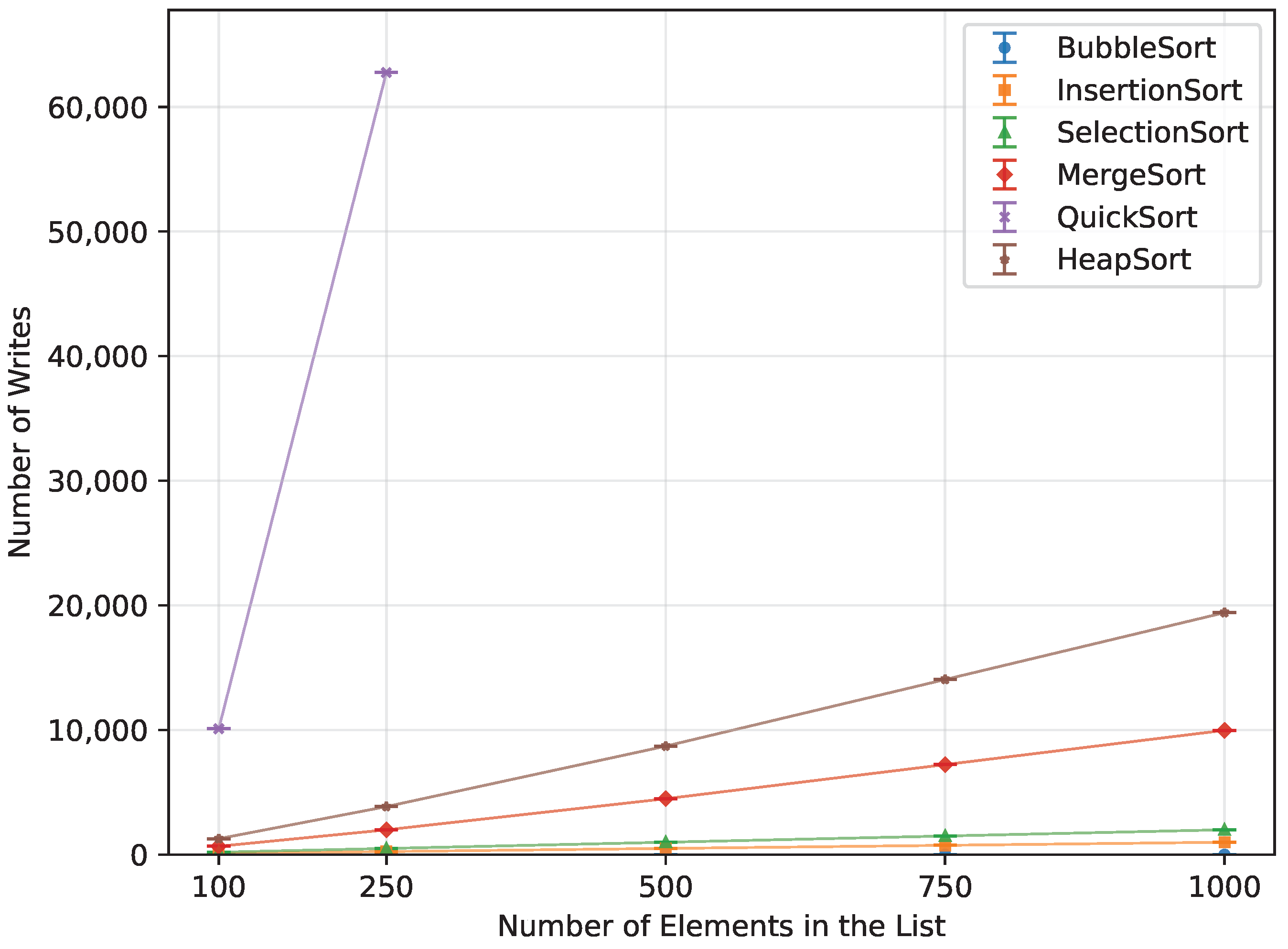

Figure 20.

Number of array-element writes for all algorithms vs. array size for reverse-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 20.

Number of array-element writes for all algorithms vs. array size for reverse-order inputs (averaged across boards).

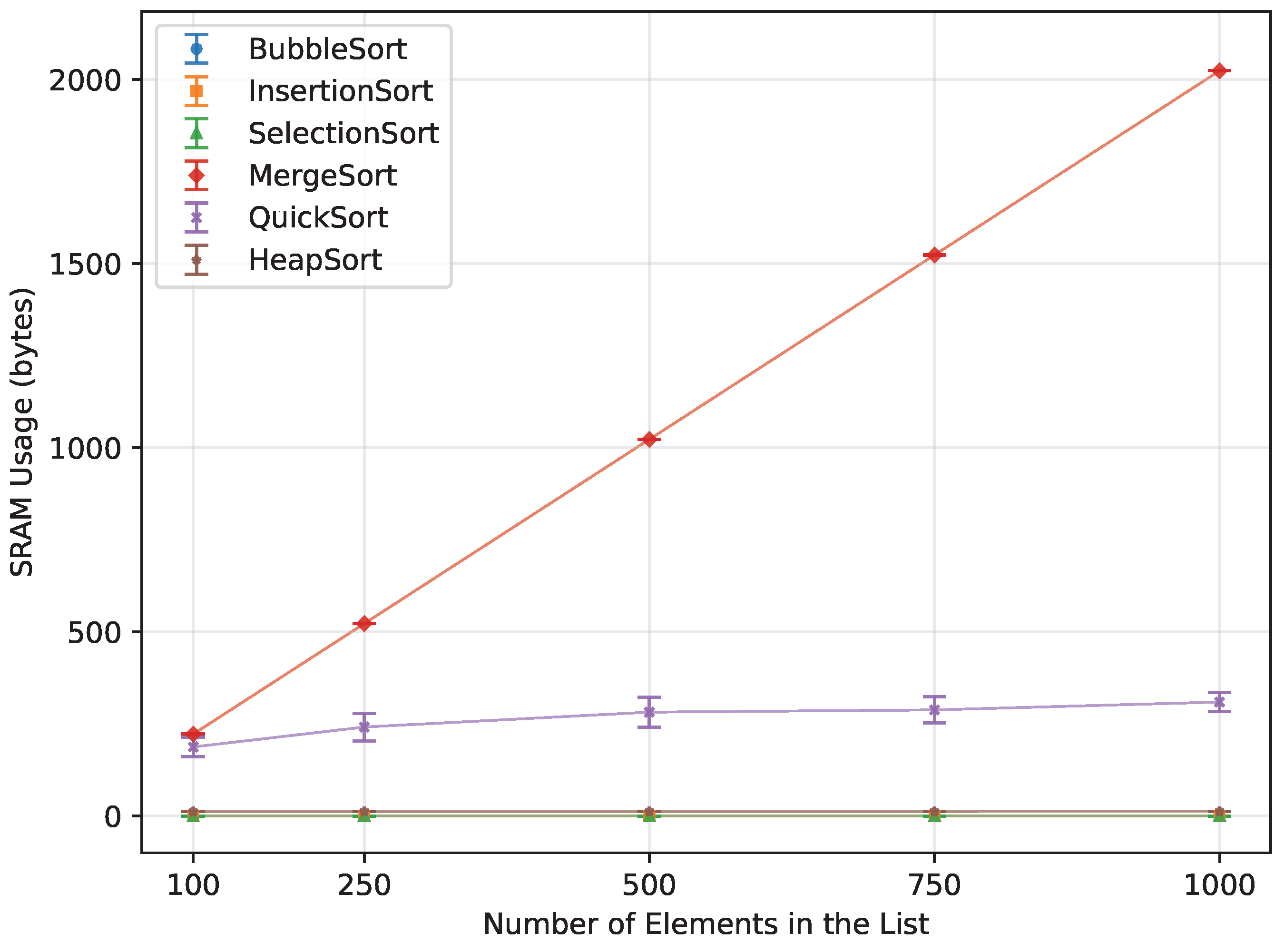

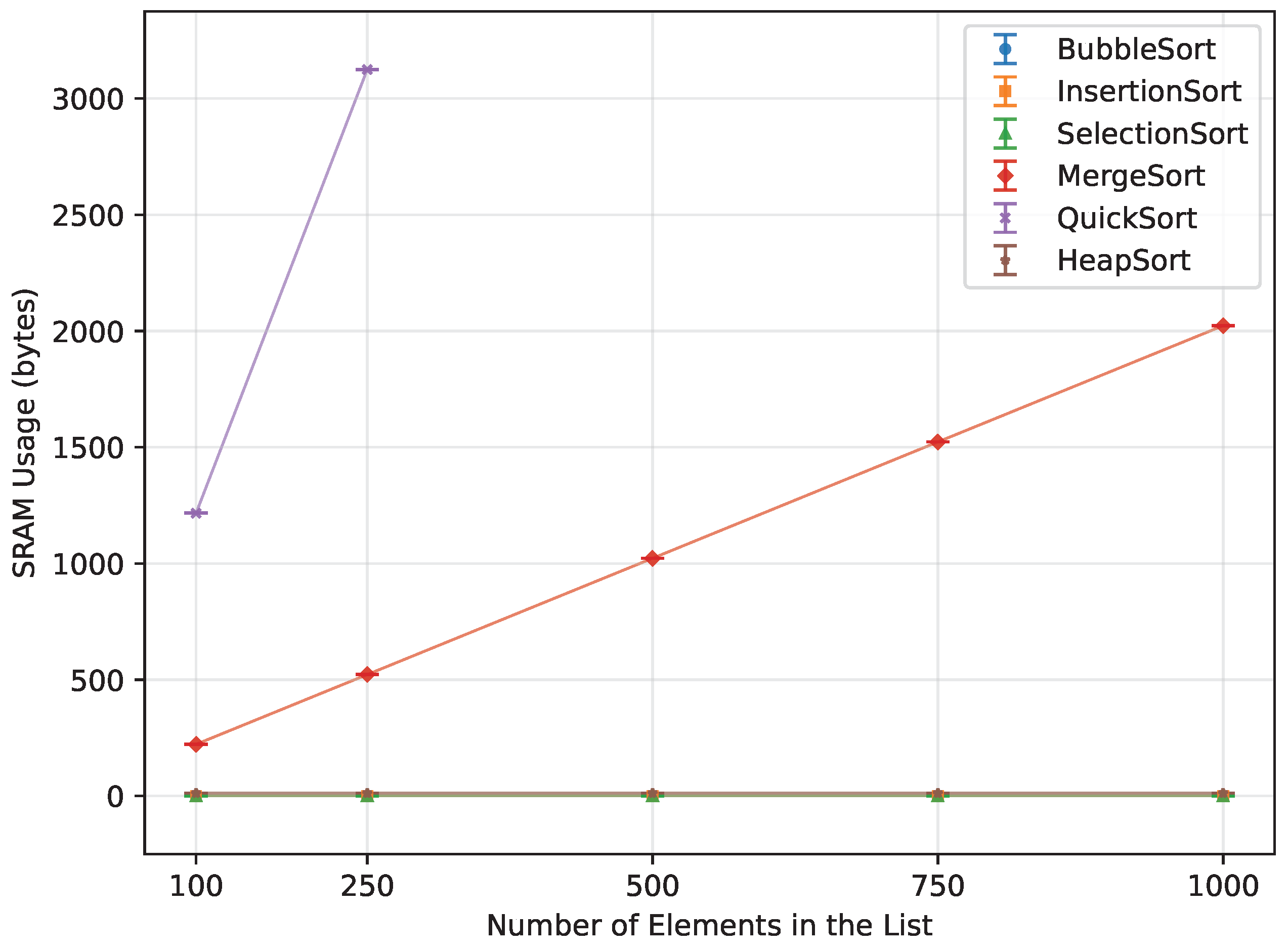

Figure 21.

SRAM usage of all algorithms vs. array size for random-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 21.

SRAM usage of all algorithms vs. array size for random-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 22.

SRAM usage of all algorithms vs. array size for ascending-order inputs (averaged across boards).

Figure 22.

SRAM usage of all algorithms vs. array size for ascending-order inputs (averaged across boards).

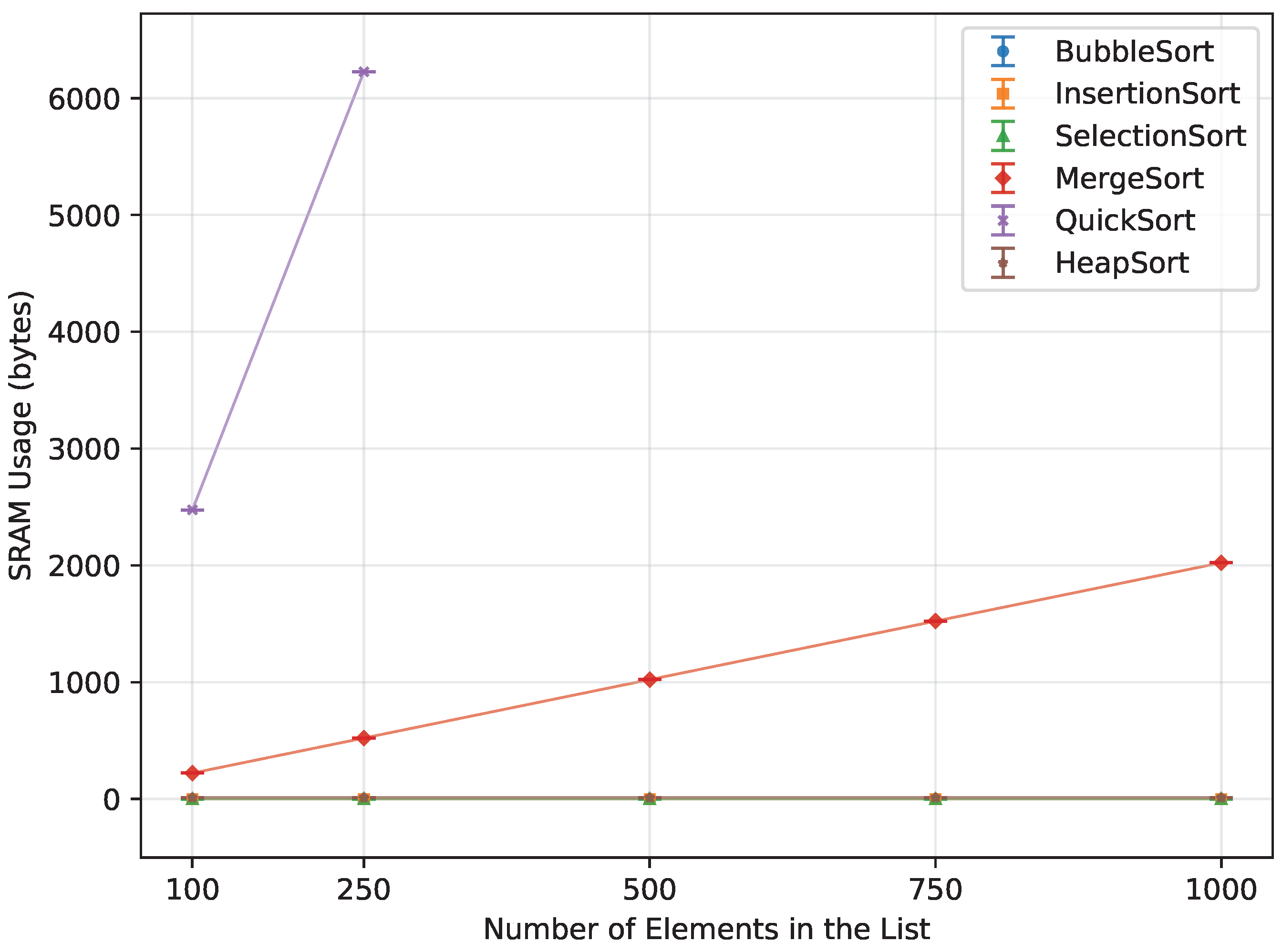

Figure 23.

SRAM usage of all algorithms vs. array size for reverse-order inputs (averaged across boards.

Figure 23.

SRAM usage of all algorithms vs. array size for reverse-order inputs (averaged across boards.

Table 1.

Summary of theoretical properties of the sorting algorithms considered in this study. Time complexity is given in terms of input size

n; extra memory refers to auxiliary storage beyond the input array. The complexity and stability characteristics follow standard textbook results for comparison-based sorting algorithms [

21,

22,

23].

Table 1.

Summary of theoretical properties of the sorting algorithms considered in this study. Time complexity is given in terms of input size

n; extra memory refers to auxiliary storage beyond the input array. The complexity and stability characteristics follow standard textbook results for comparison-based sorting algorithms [

21,

22,

23].

| Algorithm | Time Complexity (Best/Average/Worst) | Extra Memory | Stability |

|---|

| Bubble Sort | / / | (in-place) | stable |

| Insertion Sort | / / | (in-place) | stable |

| Selection Sort | / / | (in-place) | not stable |

| Merge Sort | / / | (auxiliary array) | stable |

| Quick Sort | / / | (recursion stack) | not stable |

| Heap Sort | / / | (in-place) | not stable |

Table 2.

Measured versus theoretical SRAM usage for varying recursion depths and local array sizes.

Table 2.

Measured versus theoretical SRAM usage for varying recursion depths and local array sizes.

Recursion

Depth | Array

Size [B] | Free

Memory [B] | Used

Memory [B] | Theoretical [B] | Offset [B] |

|---|

| 1 | 4 | 7913 | 40 | 4 | 36 |

| 1 | 16 | 7901 | 52 | 16 | 36 |

| 1 | 64 | 7853 | 100 | 64 | 36 |

| 1 | 128 | 7789 | 164 | 128 | 36 |

| 10 | 4 | 7796 | 157 | 40 | 117 |

| 10 | 16 | 7676 | 277 | 160 | 117 |

| 10 | 64 | 7196 | 757 | 640 | 117 |

| 10 | 128 | 6556 | 1397 | 1280 | 117 |

| 25 | 4 | 7601 | 352 | 100 | 252 |

| 25 | 16 | 7301 | 652 | 400 | 252 |

| 25 | 64 | 6101 | 1852 | 1600 | 252 |

| 25 | 128 | 4501 | 3452 | 3200 | 252 |

| 50 | 4 | 7276 | 677 | 200 | 477 |

| 50 | 16 | 6676 | 1277 | 800 | 477 |

| 50 | 64 | 4276 | 3677 | 3200 | 477 |

| 50 | 128 | 1076 | 6877 | 6400 | 477 |

Table 3.

Bubble Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 3.

Bubble Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno [s] | Leonardo [s] | Mega 2560 [s] |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 19,869.00 | 19,190.50 | 20,052.50 |

| 250 | 122,663.50 | 119,963.50 | 123,630.00 |

| 500 | 493,250.50 | 492,573.00 | 494,323.50 |

| 750 | 1,111,438.00 | 1,103,227.50 | 1,102,154.50 |

| 1000 | – | 1,964,432.00 | 1,951,955.50 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 174.67 | 173.33 | 172.00 |

| 250 | 432.00 | 425.33 | 426.67 |

| 500 | 857.33 | 860.00 | 861.33 |

| 750 | 1286.67 | 1282.67 | 1284.00 |

| 1000 | – | 1713.33 | 1712.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 30,989.33 | 30,926.67 | 31,012.00 |

| 250 | 192,697.33 | 193,449.33 | 192,748.00 |

| 500 | 770,197.33 | 773,946.67 | 770,322.67 |

| 750 | 1,732,793.33 | 1,741,532.00 | 1,733,044.00 |

| 1000 | – | 3,096,206.67 | 3,080,904.00 |

Table 4.

Insertion Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 4.

Insertion Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno [s] | Leonardo [s] | Mega 2560 [s] |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 9648.00 | 10,249.50 | 10,639.50 |

| 250 | 64,666.00 | 61,887.00 | 59,640.00 |

| 500 | 246,226.50 | 246,895.00 | 242,610.50 |

| 750 | 555,030.00 | 548,295.50 | 558,498.50 |

| 1000 | - | 959,124.00 | 987,995.50 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 500.00 | 498.67 | 497.33 |

| 250 | 1246.67 | 1254.67 | 1250.67 |

| 500 | 2534.67 | 2530.67 | 2536.00 |

| 750 | 3793.33 | 3796.00 | 3805.33 |

| 1000 | - | 5056.00 | 5070.67 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 19,860.00 | 19,822.67 | 19,874.67 |

| 250 | 122,658.67 | 123,040.00 | 122,694.67 |

| 500 | 488,682.67 | 490,970.67 | 488,773.33 |

| 750 | 1,098,326.67 | 1,103,774.67 | 1,098,492.00 |

| 1000 | - | 1,961,472.00 | 1,951,877.33 |

Table 5.

Selection Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 5.

Selection Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno [s] | Leonardo [s] | Mega 2560 [s] |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 10,378.50 | 10,371.50 | 10,386.00 |

| 250 | 62,327.00 | 62,677.00 | 62,334.50 |

| 500 | 254,380.00 | 255,722.00 | 254,411.00 |

| 750 | 570,189.00 | 573,157.00 | 570,259.00 |

| 1000 | – | 1,016,991.50 | 1,011,868.00 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 10,388.00 | 10,365.33 | 10,400.00 |

| 250 | 62,493.33 | 62,677.33 | 62,516.00 |

| 500 | 254,538.67 | 255,744.00 | 254,600.00 |

| 750 | 570,346.67 | 573,186.67 | 570,448.00 |

| 1000 | – | 1,017,032.00 | 1,012,076.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 10,388.00 | 10,369.33 | 10,400.00 |

| 250 | 62,492.00 | 62,676.00 | 62,513.33 |

| 500 | 254,540.00 | 255,741.33 | 254,598.67 |

| 750 | 570,346.67 | 573,190.67 | 570,446.67 |

| 1000 | – | 1,017,033.33 | 1,012,073.33 |

Table 6.

Merge Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 6.

Merge Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno [s] | Leonardo [s] | Mega 2560 [s] |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 6756.00 | 6753.00 | 6900.00 |

| 250 | 19,377.50 | 19,477.50 | 19,801.50 |

| 500 | – | 43,057.00 | 43,786.00 |

| 750 | – | – | 69,770.50 |

| 1000 | – | – | 95,909.50 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 6298.67 | 6281.33 | 6446.67 |

| 250 | 17,982.67 | 17,949.33 | 18,422.67 |

| 500 | – | 39,538.67 | 40,460.00 |

| 750 | – | – | 64,448.00 |

| 1000 | – | – | 88,156.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 6512.00 | 6501.33 | 6660.00 |

| 250 | 18,710.67 | 18,676.00 | 19,152.00 |

| 500 | – | 41,089.33 | 41,992.00 |

| 750 | – | – | 66,466.67 |

| 1000 | – | – | 91,416.00 |

Table 7.

Merge Sort starting free memory and memory usage comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 7.

Merge Sort starting free memory and memory usage comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno | Leonardo | Mega 2560 |

|---|

| Free [B] | Used [B] |

Free [B]

|

Used [B]

|

Free [B]

|

Used [B]

|

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 1614 | 222 | 2161 | 222 | 7756 | 223 |

| 250 | 1314 | 522 | 1861 | 522 | 7456 | 523 |

| 500 | - | - | 1361 | 1022 | 6956 | 1023 |

| 750 | - | - | - | - | 6456 | 1523 |

| 1000 | - | - | - | - | 5956 | 2023 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 1614 | 222 | 2161 | 222 | 7756 | 223 |

| 250 | 1314 | 522 | 1861 | 522 | 7456 | 523 |

| 500 | - | - | 1361 | 1022 | 6956 | 1023 |

| 750 | - | - | - | - | 6456 | 1523 |

| 1000 | - | - | - | - | 5956 | 2023 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 1614 | 222 | 2161 | 222 | 7756 | 223 |

| 250 | 1314 | 522 | 1861 | 522 | 7456 | 523 |

| 500 | - | - | 1361 | 1022 | 6956 | 1023 |

| 750 | - | - | - | - | 6456 | 1523 |

| 1000 | - | - | - | - | 5956 | 2023 |

Table 8.

Quick Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 8.

Quick Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno [s] | Leonardo [s] | Mega 2560 [s] |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 3759.00 | 3684.00 | 3588.00 |

| 250 | 10,226.00 | 10,521.00 | 10,994.50 |

| 500 | 23,964.50 | 24,560.00 | 24,962.50 |

| 750 | 36,940.00 | 40,565.00 | 38,233.50 |

| 1000 | – | 53,922.50 | 54,598.50 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | – | – | 35,025.33 |

| 250 | – | – | 213,221.33 |

| 500 | – | – | – |

| 750 | – | – | – |

| 1000 | – | – | – |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 21,837.33 | 21,798.67 | 21,868.00 |

| 250 | – | – | 131,661.33 |

| 500 | – | – | – |

| 750 | – | – | – |

| 1000 | – | – | – |

Table 9.

Quick Sort starting free memory and memory usage comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 9.

Quick Sort starting free memory and memory usage comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno | Leonardo | Mega 2560 |

|---|

| Free [B] | Used [B] |

Free [B]

|

Used [B]

|

Free [B]

|

Used [B]

|

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 1612 | 186 | 2159 | 189 | 7759 | 188 |

| 250 | 1312 | 219 | 1861 | 243 | 7459 | 263 |

| 500 | 812 | 273 | 1361 | 279 | 6957 | 294 |

| 750 | 314 | 252 | 863 | 312 | 6457 | 300 |

| 1000 | - | - | 361 | 303 | 5957 | 316 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | - | - | - | - | 7759 | 2475 |

| 250 | - | - | - | - | 7459 | 6225 |

| 500 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 750 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1000 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 1612 | 1200 | 2159 | 1200 | 7759 | 1250 |

| 250 | - | - | - | - | 7459 | 3125 |

| 500 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 750 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1000 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Table 10.

Heap Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 10.

Heap Sort execution time comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno [s] | Leonardo [s] | Mega 2560 [s] |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 6094.50 | 6085.00 | 6097.50 |

| 250 | 18,144.50 | 18,313.00 | 18,275.50 |

| 500 | 41,262.00 | 41,388.50 | 41,306.50 |

| 750 | 66,207.50 | 66,597.50 | 66,466.00 |

| 1000 | - | 92,554.50 | 92,303.50 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 6530.67 | 6520.00 | 6562.67 |

| 250 | 19,544.00 | 19,504.00 | 19,626.67 |

| 500 | 43,824.00 | 43,909.33 | 44,000.00 |

| 750 | 70,504.00 | 70,741.33 | 70,756.00 |

| 1000 | - | 97,673.33 | 97,609.33 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 5518.67 | 5510.67 | 5552.00 |

| 250 | 16,821.33 | 16,782.67 | 16,905.33 |

| 500 | 38,322.67 | 38,380.00 | 38,500.00 |

| 750 | 61,957.33 | 62,140.00 | 62,197.33 |

| 1000 | - | 86,204.00 | 86,218.67 |

Table 11.

Heap Sort starting free memory and memory usage comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

Table 11.

Heap Sort starting free memory and memory usage comparison across Arduino Uno, Leonardo, and Mega2560.

| Order Type | N | Uno | Leonardo | Mega 2560 |

|---|

| Free [B] | Used [B] |

Free [B]

|

Used [B]

|

Free [B]

|

Used [B]

|

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 1618 | 12 | 2165 | 12 | 7759 | 13 |

| 250 | 1318 | 12 | 1865 | 12 | 7459 | 13 |

| 500 | 818 | 12 | 1365 | 12 | 6959 | 13 |

| 750 | 318 | 12 | 865 | 12 | 6459 | 13 |

| 1000 | - | - | 365 | 12 | 5959 | 13 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 1618 | 12 | 2165 | 12 | 7759 | 13 |

| 250 | 1318 | 12 | 1865 | 12 | 7459 | 13 |

| 500 | 818 | 12 | 1365 | 12 | 6959 | 13 |

| 750 | 318 | 12 | 865 | 12 | 6459 | 13 |

| 1000 | - | - | 365 | 12 | 5959 | 13 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 1618 | 12 | 2165 | 12 | 7759 | 13 |

| 250 | 1318 | 12 | 1865 | 12 | 7459 | 13 |

| 500 | 818 | 12 | 1365 | 12 | 6959 | 13 |

| 750 | 318 | 12 | 865 | 12 | 6459 | 13 |

| 1000 | - | - | 365 | 12 | 5959 | 13 |

Table 12.

Results for Bubble Sort, averaged across all three boards.

Table 12.

Results for Bubble Sort, averaged across all three boards.

| Order Type | N | Time [s] | Memory Usage [B] | No. Writes |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 19,704.00 | 0.00 | 4958.17 |

| 250 | 122,085.67 | 0.00 | 30,901.08 |

| 500 | 493,382.33 | 0.00 | 125,583.58 |

| 750 | 1,105,606.67 | 0.00 | 280,455.83 |

| 1000 | 1,958,193.75 | 0.00 | 494,941.63 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 173.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 250 | 428.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 500 | 859.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 750 | 1284.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1000 | 1712.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 30,976.00 | 0.00 | 9900.00 |

| 250 | 192,964.89 | 0.00 | 62,250.00 |

| 500 | 771,488.89 | 0.00 | 249,500.00 |

| 750 | 1,735,789.78 | 0.00 | 561,750.00 |

| 1000 | 3,088,555.33 | 0.00 | 999,000.00 |

Table 13.

Results for Insertion Sort, averaged across all three boards.

Table 13.

Results for Insertion Sort, averaged across all three boards.

| Order Type | N | Time [s] | Memory Usage [B] | No. Writes |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 10,179.00 | 0.00 | 2566.96 |

| 250 | 62,064.33 | 0.00 | 15,821.83 |

| 500 | 245,244.00 | 0.00 | 62,655.17 |

| 750 | 553,941.33 | 0.00 | 141,639.29 |

| 1000 | 973,559.75 | 0.00 | 248,811.81 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 498.67 | 0.00 | 99.00 |

| 250 | 1250.67 | 0.00 | 249.00 |

| 500 | 2533.78 | 0.00 | 499.00 |

| 750 | 3798.22 | 0.00 | 749.00 |

| 1000 | 5063.33 | 0.00 | 999.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 19,852.44 | 0.00 | 5049.00 |

| 250 | 122,797.78 | 0.00 | 31,374.00 |

| 500 | 489,475.56 | 0.00 | 125,249.00 |

| 750 | 1,100,197.78 | 0.00 | 281,624.00 |

| 1000 | 1,956,674.67 | 0.00 | 500,499.00 |

Table 14.

Results for Selection Sort, averaged across all three boards.

Table 14.

Results for Selection Sort, averaged across all three boards.

| Order Type | N | Time [s] | Memory Usage [B] | No. Writes |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 10,378.67 | 0.00 | 198.00 |

| 250 | 62,446.17 | 0.00 | 498.00 |

| 500 | 254,837.67 | 0.00 | 998.00 |

| 750 | 571,201.67 | 0.00 | 1498.00 |

| 1000 | 1,014,429.75 | 0.00 | 1998.00 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 10,384.44 | 0.00 | 198.00 |

| 250 | 62,562.22 | 0.00 | 498.00 |

| 500 | 254,960.89 | 0.00 | 998.00 |

| 750 | 571,327.11 | 0.00 | 1498.00 |

| 1000 | 1,014,554.00 | 0.00 | 1998.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 10,385.78 | 0.00 | 198.00 |

| 250 | 62,560.44 | 0.00 | 498.00 |

| 500 | 254,960.00 | 0.00 | 998.00 |

| 750 | 571,328.00 | 0.00 | 1498.00 |

| 1000 | 1,014,553.33 | 0.00 | 1998.00 |

Table 15.

Results for Merge Sort, averaged across all three boards.

Table 15.

Results for Merge Sort, averaged across all three boards.

| Order Type | N | Time [s] | Memory Usage [B] | No. Writes |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 6803.00 | 222.33 | 672.00 |

| 250 | 19,552.17 | 522.33 | 1994.00 |

| 500 | 43,421.50 | 1022.50 | 4488.00 |

| 750 | 69,770.50 | 1523.00 | 7226.00 |

| 1000 | 95,909.50 | 2023.00 | 9976.00 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 6342.22 | 222.33 | 672.00 |

| 250 | 18,118.22 | 522.33 | 1994.00 |

| 500 | 39,999.33 | 1022.50 | 4488.00 |

| 750 | 64,448.00 | 1523.00 | 7226.00 |

| 1000 | 88,156.00 | 2023.00 | 9976.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 6557.78 | 222.33 | 672.00 |

| 250 | 18,846.22 | 522.33 | 1994.00 |

| 500 | 41,540.67 | 1022.50 | 4488.00 |

| 750 | 66,466.67 | 1523.00 | 7226.00 |

| 1000 | 91,416.00 | 2023.00 | 9976.00 |

Table 16.

Results for Quick Sort, averaged across all three boards.

Table 16.

Results for Quick Sort, averaged across all three boards.

| Order Type | N | Time [s] | Memory Usage [B] | No. Writes |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 3677.00 | 187.50 | 786.25 |

| 250 | 10,580.50 | 241.50 | 2317.58 |

| 500 | 24,495.67 | 281.92 | 5418.75 |

| 750 | 38,579.50 | 288.00 | 8511.83 |

| 1000 | 54,260.50 | 309.31 | 12,107.00 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 35,025.33 | 2475.00 | 10,098.00 |

| 250 | 213,221.33 | 6225.00 | 62,748.00 |

| 500 | – | – | – |

| 750 | – | – | – |

| 1000 | – | – | – |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 21,834.67 | 1216.67 | 5098.00 |

| 250 | 131,661.33 | 3125.00 | 31,498.00 |

| 500 | – | – | – |

| 750 | – | – | – |

| 1000 | – | – | – |

Table 17.

Results for Heap Sort, averaged across all three boards.

Table 17.

Results for Heap Sort, averaged across all three boards.

| Order Type | N | Time [s] | Memory Usage [B] | No. Writes |

|---|

| Random Order | 100 | 6092.33 | 12.33 | 1165.33 |

| 250 | 18,244.33 | 12.33 | 3547.08 |

| 500 | 41,319.00 | 12.33 | 8089.33 |

| 750 | 66,423.67 | 12.33 | 13,050.92 |

| 1000 | 92,429.00 | 12.50 | 18,172.75 |

| Ascending Order | 100 | 6537.78 | 12.33 | 1280.00 |

| 250 | 19,558.22 | 12.33 | 3856.00 |

| 500 | 43,911.11 | 12.33 | 8708.00 |

| 750 | 70,667.11 | 12.33 | 14,052.00 |

| 1000 | 97,641.33 | 12.50 | 19,416.00 |

| Reverse Order | 100 | 5527.11 | 12.33 | 1032.00 |

| 250 | 16,836.44 | 12.33 | 3182.00 |

| 500 | 38,400.89 | 12.33 | 7352.00 |

| 750 | 62,098.22 | 12.33 | 11,966.00 |

| 1000 | 86,211.33 | 12.50 | 16,632.00 |