Assessment of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using Smartphone-Based Digital Lifelogging: A Multi-Center, Prospective Observational Study

Highlights

- Smartphone-based digital lifelogs, specifically usual gait speed, daily step count, and subjective health, are significantly associated with frailty and explain substantially more variance than traditional clinical indicators alone.

- Continuous, real-world mobility metrics collected via embedded smartphone sensors provide meaningful insights into functional decline that are not captured by conventional clinic-based frailty assessments.

- Smartphone-based monitoring offers a scalable, low-burden approach to community-based frailty assessment and monitoring, with potential to support future longitudinal risk prediction after validation.

- Integrating digital lifelog data into geriatric care pathways can enable proactive intervention, personalized management, and more accurate frailty risk stratification in everyday living environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

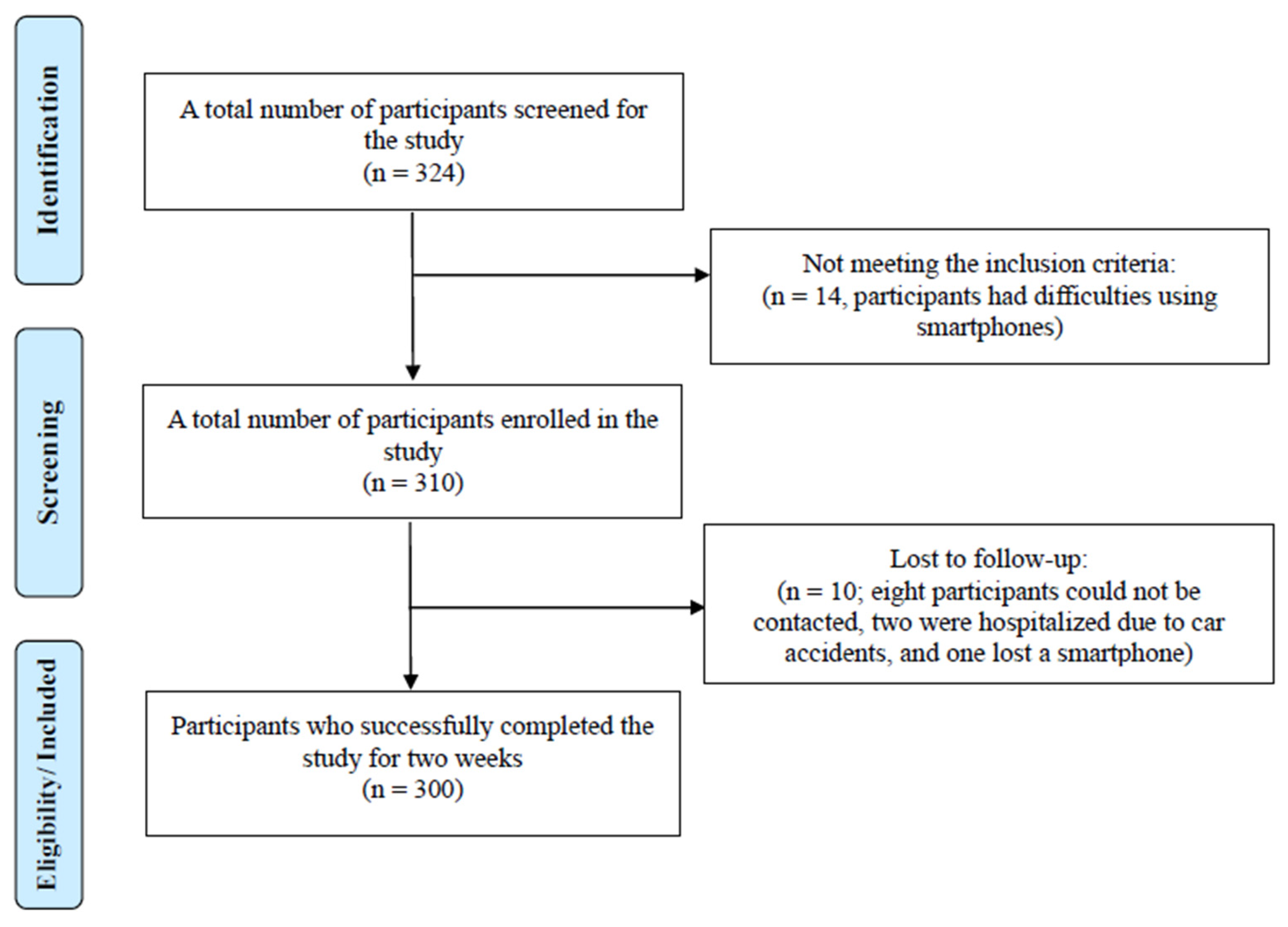

2.1. Recruitment and Sample Size Calculation

2.2. The Mobile Application

2.3. Frailty Index

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Measurements

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Characteristics of the Collected Digital Lifelogs

3.3. Factors Correlated Between FI and Digital Lifelogs

3.4. Frailty Modeling Using Digital Lifelogs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| AWGS | Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CGA | Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment |

| CGA-FI | Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment–Frailty Index |

| CFS | Clinical Frailty Scale |

| FI | Frailty Index |

| FP | Frailty Phenotype |

| FRAIL | Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of Weight |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| RPE | Ratings of Perceived Exertion |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SMM | Skeletal Muscle Mass |

| SPPB | Short Physical Performance Battery |

| 30 s STS | 30-second Sit-to-Stand Test |

References

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Mu, D.; Wang, Y. Association of low muscle mass with cognitive function and mortality in USA seniors: Results from NHANES 1999–2002. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E.; Vellas, B.; van Kan, G.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bauer, J.M.; Bernabei, R.; Cesari, M.; Chumlea, W.C.; Doehner, W.; Evans, J.; et al. Frailty consensus: A call to action. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, S.D.; Mitnitski, A.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Gill, T.M.; Rockwood, K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 2008, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskirbayeva, D.; West, R.; Jaafari, H.; King, N.; Howdon, D.; Shuweihdi, F.; Clegg, A.; Nikolova, S. Progression of frailty as measured by a cumulative deficit index: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 84, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfson, D.B.; Majumdar, S.R.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Tahir, A.; Rockwood, K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puts, M.T.E.; Toubasi, S.; Andrew, M.K.; Ashe, M.C.; Ploeg, J.; Atkinson, E.; Ayala, A.P.; Roy, A.; Rodríguez Monforte, M.; Bergman, H.; et al. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Can. Geriatr. J. 2020, 23, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apóstolo, J.; Cooke, R.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Santana, S.; Marcucci, M.; Cano, A.; Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.; Germini, F.; Holland, C. Predicting risk and outcomes for frail older adults: An umbrella review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2017, 15, 1154–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.W.; Yoo, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Choi, J.Y.; Yoon, S.J.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, K.I. The Korean version of the FRAIL scale. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Lee, E.; Jang, I.Y. Frailty and Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhodary, A.A.; Syed Mohamed Aljunid, I.; Nur, A.M.; Shahar, S. The economic burden of frailty among elderly people. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2020, 20, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckinx, F.; Rolland, Y.; Reginster, J.Y.; Ricour, C.; Petermans, J.; Bruyère, O. Burden of frailty in the elderly population. Arch. Public Health 2015, 73, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decoster, L.; Van Puyvelde, K.; Mohile, S.; Wedding, U.; Basso, U.; Colloca, G.; Rostoft, S.; Overcash, J.; Wildiers, H.; Steer, C.; et al. Screening tools for multidimensional problems in older cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overcash, J.A.; Beckstead, J.; Extermann, M.; Cobb, S. The abbreviated comprehensive geriatric assessment. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005, 54, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamoukdjian, F.; Paillaud, E.; Zelek, L.; Laurent, M.; Lévy, V.; Landre, T.; Georges, S. Measurement of gait speed to identify complications associated with frailty: A systematic review. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2015, 6, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloum, R.; Consel, C.; Volanschi, N. A tool-based methodology for long-term activity monitoring. In Proceedings of the 13th PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments Conference, Corfu, Greece, 30 June–3 July 2020; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Rantz, M.J.; Skubic, M.; Popescu, M.; Galambos, C.; Koopman, R.J.; Alexander, G.L.; Phillips, L.J.; Musterman, K.; Back, J.; Miller, S.J. Technology-enabled vital signs for early detection of health change. Gerontology 2015, 61, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Dwan, T.; Petrovich, T. Effectiveness of a virtual reality forest on dementia. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Desai, M.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, L.; Houghtaling, P.; Gillinov, M. Accuracy of wrist-worn heart rate monitors. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, G.; Ray, P.; Akter, S.; Masella, C.; Ganz, A. mHealth technologies for chronic diseases. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.S.; Qadir, S.; Anjum, G.; Uddin, N. StresSense: Real-time detection of stress. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 185, 105401. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.L.; Ding, X.R.; Poon, C.C.; Lo, B.P.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.L.; Yang, G.Z.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, Y.T. Unobtrusive sensing and wearables for health informatics. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 61, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lott, S.A.; Streel, E.; Bachman, S.L.; Bode, K.; Dyer, J.; Fitzer-Attas, C.; Goldsack, J.C.; Hake, A.; Jannati, A.; Fuertes, R.S.; et al. Digital health technologies for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, R.; Trifan, A.; Neves, A.J.R. Lifelog retrieval from daily data. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e30517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seok, J.W.; Kwon, Y.J.; Lee, H. Feasibility and efficacy of TouchCare system. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Choi, J.E.; Lee, H.S.; Jeon, S.; Lee, J.W.; Hong, K.W. Walking steps and metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5433. [Google Scholar]

- Matlary, R.E.D.; Holme, P.A.; Glosli, H.; Rueegg, C.S.; Grydeland, M. Activity measurements comparison. Haemophilia 2022, 28, e172–e180. [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco, S.; Sica, M.; Ancillao, A.; Timmons, S.; Barton, J.; O’Flynn, B. Validity of Fitbit Charge2 and Garmin vivosmart. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e13084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiris, G.; Hensel, B.K. Technologies for an aging society: A systematic review of “smart home” applications. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2008, 17, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Trifan, A.; Oliveira, M.; Oliveira, J.L. Passive sensing of health outcomes through smartphones: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e12649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajamarca, G.; Herskovic, V.; Rossel, P.O. Enabling older adults’ health self-management through self-report and visualization. Sensors 2020, 20, 4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.; Caulfield, B. Non-invasive physical activity recognition using smartphones. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, San Diego, CA, USA, 28 August–1 September 2012; pp. 3340–3343. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, H.; Song, Q.; Zeng, X.; Yue, J. Wearable sensor technologies for frailty assessment: A review. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 200, 112668. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Ferrucci, L.; Culham, E.; Metter, E.J.; Guralnik, J.; Deshpande, N. Five-times-sit-to-stand task predicting falls/disability. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millor, N.; Lecumberri, P.; Gómez, M.; Martínez-Ramírez, A.; Izquierdo, M. 30-s chair stand test and frailty detection. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2013, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.J.; Giuliani, C.; Morey, M.C.; Pieper, C.F.; Evenson, K.R.; Mercer, V.; Cohen, H.J.; Visser, M.; Brach, J.S.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; et al. Physical activity as preventative factor for frailty. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2009, 64, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Abbatecola, A.M.; Provinciali, M.; Corsonello, A.; Bustacchini, S.; Manigrasso, L.; Cherubini, A.; Bernabei, R.; Lattanzio, F. Physical activity and frailty. Biogerontology 2010, 11, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavasour, G.; Giggins, O.M.; Doyle, J.; Kelly, D. Wearable sensors to evaluate frailty: Systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinka, M.D.; Buta, B.; Bader, K.D.; Hanley, C.; Schoenborn, N.L.; McNabney, M.; Xue, Q.L. Sensor-based mobile application for in-home frailty assessment: Qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. Studies of illness in aged: Index of ADL. JAMA 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M. Assessment of older people: IADL. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray-Miceli, D. Impaired mobility and functional decline in older adults. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 52, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosow, I.; Breslau, N. Guttman health scale for aged. J. Gerontol. 1966, 21, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borson, S.; Scanlan, J.M.; Chen, P.; Ganguli, M. Mini-Cog validation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1451–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.W.; Roh, H.; Cho, Y.; Jeong, J.; Shin, Y.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Guralnik, J.M.; Park, J. Validation of multi-sensor kiosk for short physical performance battery. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2495–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.M.; Jung, H.W.; Jang, I.Y.; Baek, J.Y.; Yoon, S.; Roh, H.; Lee, E. Comparison of electronic physical performance batteries. Sensors 2021, 21, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R.J.; Berkman, L.F.; Blazer, D.G.; Scherr, P.A.; Wallace, R.B. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M85–M94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.C.; Denison, H.J.; Martin, H.J.; Patel, H.P.; Syddall, H.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. Grip strength measurement review. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.M.; Song, X.; Rockwood, K. Frailty index from CGA. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 1929–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joho, H.; Matsubara, M.; Uda, N.; Mizoue, C.; Rahmi, R. Lifelogging by senior citizens: GPS-based study. F1000Research 2023, 12, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Yoon, J.Y.; Won, C.W.; Kim, M.; Lee, K.S. Health literacy and social support in smartphone–Frailty association. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.W.; Jang, I.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Yu, S.S.; Hwang, J.K.; Jeon, C.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, E. Usual gait speed is associated with frailty status, institutionalization, and mortality in community-dwelling rural older adults: A longitudinal analysis of the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, D.; Yoshida, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Kimura, M.; Group, K.S. Daily steps and frailty prevalence. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2310–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortone, I.; Sardone, R.; Lampignano, L.; Castellana, F.; Zupo, R.; Lozupone, M.; Moretti, B.; Giannelli, G.; Panza, F. How gait influences frailty models and health-related outcomes in clinical-based and population-based studies: A systematic review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 274–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyère, O.; Buckinx, F.; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bauer, J.; Cederholm, T.; Cherubini, A.; Cooper, C.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Landi, F.; et al. Clinicians’ frailty assessment practices. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 29, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, S.; Xie, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, H. Digital biomarkers for frailty: Systematic review & meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2025, 54, afaf108. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Mishra, R.; Golledge, J.; Najafi, B. Digital biomarkers of physical frailty using sensors & machine learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 5289. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanek, J.K.; Zipunnikov, V.; Harris, T.; Crainiceanu, C.; Harezlak, J.; Glynn, N.W. Validating gait characteristics from accelerometry. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuka, Y.; Chan, L.L.Y.; Brodie, M.A.; Okubo, Y.; Lord, S.R. Wrist-worn device identifying frailty: UK Biobank. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 105196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.L.Y.; Arbona, C.H.; Brodie, M.A.; Lord, S.R. Digital gait biomarkers predicting injurious falls. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afad179. [Google Scholar]

- Murao, Y.; Ishikawa, J.; Tamura, Y.; Kobayashi, F.; Iizuka, A.; Toba, A.; Harada, K.; Araki, A. Sit-to-stand performance and frailty. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 337. [Google Scholar]

- Rye Hanton, C.; Kwon, Y.J.; Aung, T.; Whittington, J.; High, R.R.; Goulding, E.H.; Schenk, A.K.; Bonasera, S.J. Mobile phone–based activity, step count, gait speed. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Ye, J.; Xu, Q.; Peng, R.; Hu, B.; Pei, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xu, F. Wearable gait sensors + machine learning improve frailty prediction. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1169083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidle, S.; Gulde, P.; Koster, R.; Soaz, C.; Hermsdörfer, J. Self-reported physical frailty vs sensor-based activity. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés-Aragonés, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, R.; Carnicero, J.A.; Moreno-Sánchez, P.A.; Oviedo-Briones, M.; Villalba-Mora, E.; Abizanda-Soler, P.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Mobile/web frailty monitoring and sensor kit: FACET RCT. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e58312. [Google Scholar]

- Delbaere, K.; Valenzuela, T.; Lord, S.R.; Clemson, L.; Zijlstra, G.A.R.; Close, J.C.T.; Lung, T.; Woodbury, A.; Chow, J.; McInerney, G.; et al. E-health StandingTall balance exercise RCT. BMJ 2021, 373, n740. [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan, A.; Lim, J.X.; Ngiam, N.H.W.; Tey, A.J.Y.; Tang, A.K.W.; Lim, H.A.; Yow, K.S.; Cheng, L.J.; Ho, J.; Nigel Teo, Q.X.; et al. Smartphone ownership, digital literacy, social connectedness & wellbeing in older adults. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290557. [Google Scholar]

| Category | YSH (n = 161) | AMC (n = 36) | MSWC (n = 103) | Total (n = 300) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 71.78 ± 5.24 | 74.11 ± 4.18 | 75.41 ± 5.21 | 73.30 ± 5.37 |

| Female (%) | 90.68% (146) | 61.11% (22) | 67.96% (70) | 79.33% (238) |

| Height (cm) | 155.37 ± 6.09 | 160.63 ± 9.57 | 157.79 ± 8.08 | 156.83 ± 7.49 |

| Weight (kg) | 55.38 ± 7.29 | 60.50 ± 13.92 | 62.41 ± 9.80 | 58.40 ± 9.73 |

| Medical history (n) | 3.36 ± 2.39 | 2.56 ± 1.81 | 1.75 ± 1.51 | 2.71 ± 2.19 |

| ADL | 0.15 ± 0.45 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.27 | 0.11 ± 0.37 |

| IADL | 0.05 ± 0.37 | 0.08 ± 0.50 | 0.10 ± 0.38 | 0.07 ± 0.39 |

| Nagi | 0.39 ± 78 | 0.25 ± 0.65 | 0.39 ± 0.69 | 0.37 ± 0.74 |

| Rosow | 0.16 ± 0.43 | 0.17 ± 0.51 | 0.12 ± 0.40 | 0.15 ± 0.43 |

| Weight loss over 4.5 kg within the year (%) | 6.83% | 16.67% | 9.71% | 9.00% |

| BMI ≤ 18.5 kg/m2 (%) | 2.48% | 11.11% | 1.96% | 3.33% |

| Mini-Cog | 3.78 ± 1.13 | 4.58 ± 0.60 | 4.25 ± 0.89 | 4.04 ± 1.04 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.95 ± 2.73 | 23.39 ± 3.21 | 25.05 ± 3.33 | 23.72 ± 3.15 |

| SMM (kg) | 20.87 ± 13.57 | 24.17 ± 7.41 | 22.39 ± 4.51 | 21.79 ± 10.64 |

| Fat (%) | 32.19 ± 6.74 | 25.04 ± 6.95 | 32.59 ± 7.42 | 31.46 ± 7.38 |

| Right arm muscle (kg) | 1.80 ± 0.35 | 2.33 ± 0.78 | 2.13 ± 0.55 | 1.98 ± 0.53 |

| Left arm muscle (kg) | 1.80 ± 0.35 | 2.32 ± 0.75 | 2.11 ± 0.55 | 1.97 ± 0.52 |

| Right leg muscle (kg) | 5.51 ± 0.93 | 6.69 ± 2.11 | 6.22 ± 1.47 | 5.90 ± 1.38 |

| Left leg muscle(kg) | 5.50 ± 0.90 | 6.66 ± 2.04 | 6.19 ± 1.45 | 5.87 ± 1.35 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 18.56 ± 4.68 | 24.51 ± 10.25 | 24.91 ± 8.57 | 21.45 ± 7.67 |

| SPPB | 11.09 ± 1.52 | 10.44 ± 1.80 | 11.54 ± 1.28 | 11.17 ± 1.52 |

| Side-by-side (s) | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 10.00 ± 0.00 | 10.00 ± 0.00 |

| Semi-tandem (s) | 9.63 ± 1.75 | 9.13 ± 2.37 | 9.85 ± 1.13 | 9.65 ± 1.67 |

| Tandem (s) | 9.00 ± 2.70 | 7.61 ± 3.64 | 9.01 ± 2.70 | 8.85 ± 2.84 |

| 6 m gait speed (m/s) | 0.92 ± 0.26 | 1.16 ± 0.62 | 1.09 ± 0.23 | 1.01 ± 0.33 |

| 5× sit-to-stand (s) | 3.58 ± 0.67 | 3.72 ± 0.57 | 3.87 ± 0.44 | 3.70 ± 0.60 |

| Frailty Index (normalized, 0–1) | 0.109 ± 0.072 | 0.085 ± 0.060 | 0.065 ± 0.057 | 0.091 ± 0.069 |

| Digital Lifelogs | n | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor-based Digital Lifelog | ||

| Usual gait speed (m/s) | 94 | 1.12 (0.13) |

| 30 s STS counts | 253 | 17.36 (5.12) |

| Daily mean steps | 290 | 3343.93 (3049.45) |

| Hourly mean steps | 290 | 759.79 (590.18) |

| Self-report-based Digital Lifelogs | ||

| RPE | 248 | 5.88 (2.17) |

| Subjective health status | 255 | 2.05 (0.42) |

| Set | n | Pearson’s r | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty Index—Usual gait speed | 94 | −0.370 *** | <0.001 | [−0.533, −0.181] |

| Frailty Index—30 s STS counts | 253 | −0.224 *** | <0.001 | [−0.338, −0.104] |

| Frailty Index—Daily mean steps | 290 | −0.119 * | 0.042 | [−0.231, −0.004] |

| Frailty Index—Hourly mean steps | 290 | −0.113 | 0.055 | [−0.225, 0.002] |

| Frailty Index—RPE | 248 | 0.135 * | 0.034 | [0.011, 0.255] |

| Frailty Index—Subjective health status | 255 | 0.232 *** | <0.001 | [0.112, 0.345] |

| Predictors | Step 1 (Frailty Phenotypes) | Step 2 (Add Digital Lifelogs) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | p | VIF | B | SE | β | p | VIF | |

| Age (year) | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.040 | 0.763 | 1.082 | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.945 | 1.481 |

| Sex (1 = female, 0 = male) | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.055 | 0.812 | 2.384 | 0.007 | 0.034 | 0.050 | 0.834 | 4.894 |

| Height (cm) | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.267 | 0.315 | 3.436 | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.172 | 0.489 | 5.297 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.289 | 0.357 | 3.316 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.112 | 0.727 | 8.780 |

| SMM (kg) | 0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.974 | 1.163 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.09 | 0.704 | 4.768 |

| Fat (%) | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.159 | 0.521 | 2.711 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.119 | 0.614 | 4.742 |

| SPPB | −0.006 | 0.007 | −0.109 | 0.401 | 1.042 | −0.001 | 0.007 | −0.026 | 0.844 | 1.447 |

| Usual gait speed (m/s) | – | – | – | – | −0.116 | 0.057 | −0.242 | 0.047 * | 1.234 | |

| 30 s STS counts | – | – | – | – | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.088 | 0.472 | 1.277 | |

| Daily mean steps | – | – | – | – | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.272 | 0.025 * | 1.197 | |

| RPE | – | – | – | – | −0.001 | 0.004 | −0.026 | 0.859 | 1.807 | |

| Subjective health status | – | – | – | – | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.254 | 0.068 | 1.612 | |

| R2 | 0.145 | 0.328 | ||||||||

| F for Model | 1.53 | 2.36 * | ||||||||

| F for change in R2 | - | 3.16 * | ||||||||

| Predictors | B_Normalized | SE_Normalized | β | T | p-Value | 95% CI | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual gait speed | −0.144 | 0.051 | −0.3 | −2.81 | 0.007 ** | [−12.30, −2.10] | 1.050 |

| 30 s STS counts | −0.002 | 0.001 | −0.179 | −1.395 | 0.168 | [−0.20, 0.05] | 1.009 |

| Daily mean steps | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.288 | 2.596 | 0.012 * | [0.00005, 0.00055] | 1.143 |

| RPE | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.105 | −0.952 | 0.345 | [−0.50, 0.15] | 1.203 |

| Subjective health status | 0.045 | 0.016 | 0.317 | 2.76 | 0.007 ** | [0.60, 3.85] | 1.200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Hong, N.; Jung, H.-W.; Baek, S.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Lee, S.; Youn, B.-Y. Assessment of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using Smartphone-Based Digital Lifelogging: A Multi-Center, Prospective Observational Study. Sensors 2026, 26, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010215

Kim J, Hong N, Jung H-W, Baek S, Cho SW, Kim J, Lee C, Lee S, Youn B-Y. Assessment of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using Smartphone-Based Digital Lifelogging: A Multi-Center, Prospective Observational Study. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010215

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Janghyeon, Namki Hong, Hee-Won Jung, Seungjin Baek, Sang Wouk Cho, Jungheui Kim, Changseok Lee, Subeom Lee, and Bo-Young Youn. 2026. "Assessment of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using Smartphone-Based Digital Lifelogging: A Multi-Center, Prospective Observational Study" Sensors 26, no. 1: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010215

APA StyleKim, J., Hong, N., Jung, H.-W., Baek, S., Cho, S. W., Kim, J., Lee, C., Lee, S., & Youn, B.-Y. (2026). Assessment of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using Smartphone-Based Digital Lifelogging: A Multi-Center, Prospective Observational Study. Sensors, 26(1), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010215