AI-Driven Smart Cockpit: Monitoring of Sudden Illnesses, Health Risk Intervention, and Future Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Integration Trends of Artificial Intelligence and Smart Cockpits

1.2. Challenges in Driver Health and Safety

1.3. Purpose and Significance of This Review

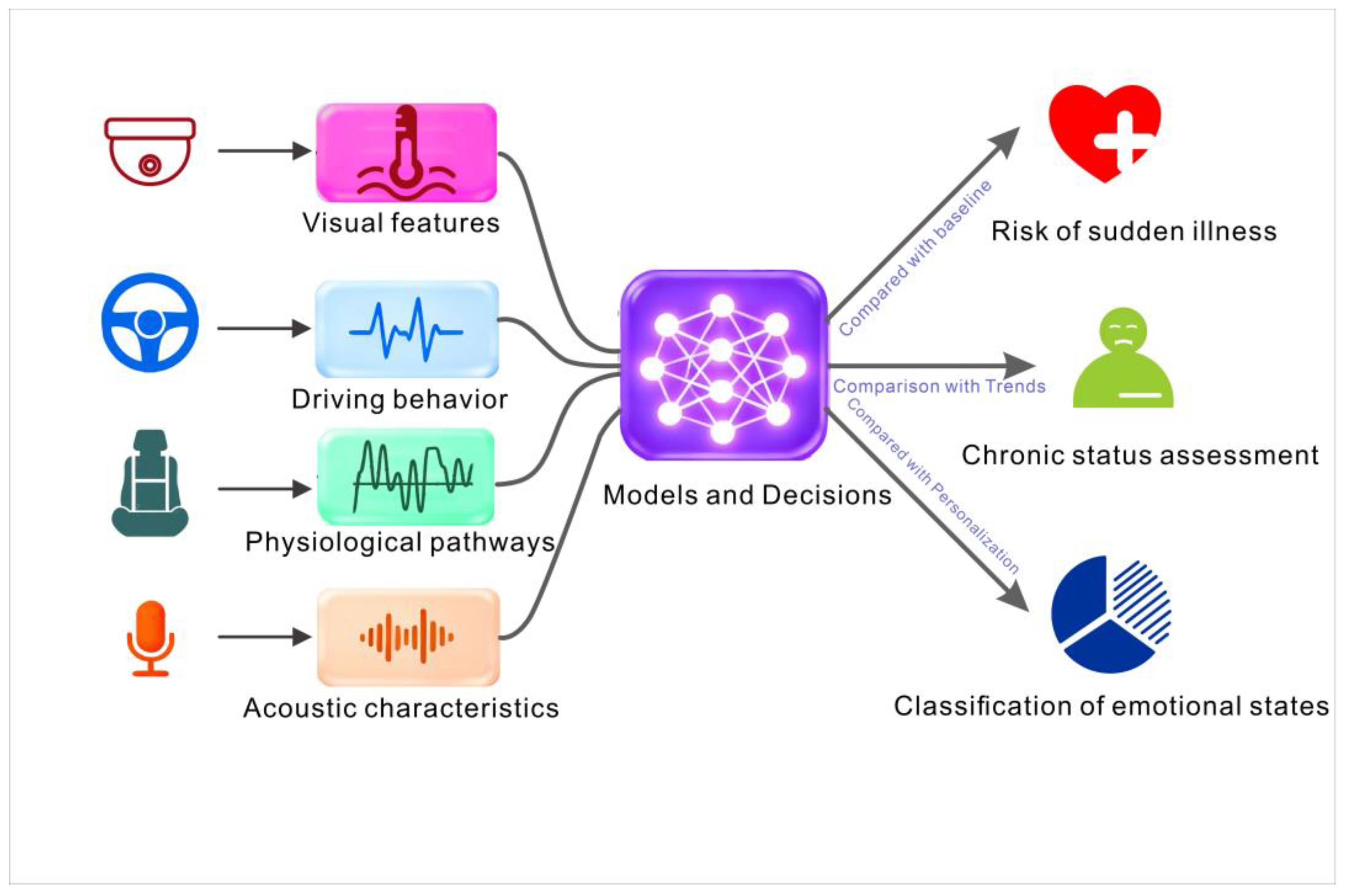

2. Foundations of Perception and Computation in Intelligent Driving Cockpits

2.1. Multimodal Biosignal Acquisition Technologies

2.2. Edge Computing and In-Vehicle AI Platforms

2.3. Integration and Management of In-Cabin and External Data

3. AI-Driven Sudden Illness Monitoring and Early Warning

| Technical Category | Key Technologies | Application Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensing and data acquisition | Contact/non-contact sensors | Real-time monitoring of multimodal signals (e.g., driver facial expressions, voice tone, heart rate variability, blood pressure, respiratory rate) | [67] |

| Traditional machine learning models | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees, Random Forests, Logistic Regression | Predicting risks of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, strokes, etc., based on historical medical records, demographic information, and real-time physiological features | [70] |

| Deep learning models | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) (for image/video feature extraction); Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN/LSTM) (for processing time-series physiological signals) | End-to-end prediction of abnormal blood pressure, arrhythmia, sleep apnea | [72] |

| Multimodal data fusion | Cross-modal feature alignment, dynamic weight allocation, fusion of visual, voice, radar, and wearable physiological data | Improving accuracy and response speed of sudden illness early warning | [73] |

| Anomaly detection and clustering | Unsupervised clustering (based on Isolation Forest, Spectral Clustering, HDBSCAN); 3D signal density-based anomaly detection | Identifying abnormal driving behaviors (sudden braking, rapid acceleration, direction deviation) or sudden changes in physiological signals to trigger immediate alerts | [73] |

| Emotion and cognitive load assessment | Dual-branch deep networks, emotion computing models | Real-time monitoring of emotional states (e.g., fatigue, anxiety, anger); automatically adjust cabin lighting/air conditioning or issue voice reminders when emotions deteriorate | [75] |

| Personalized health baseline | Constructing personal health baselines based on historical EHR, genetic information, and long-term wearable data | Enabling early warning and supporting personalized intervention plans | [76,77] |

4. Intelligent Health Risk Intervention Strategies in Smart Cockpits

4.1. AI-Driven Personalized Interventions

4.2. Intelligent Emergency Response Mechanisms

4.3. Synergy with External Ecosystems

5. Challenges and Future Directions

5.1. Technical Challenges

5.2. Ethical, Privacy, and Legal Challenges

5.3. Future Research Opportunities

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance Systems |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CVDs | Cardiovascular Diseases |

| DASs | Driver Assistance Systems |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EHRs | Electronic Health Records |

| EI | Emotional Intelligence |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GSR | Galvanic Skin Response |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interface |

| HPC | High-Performance Computing |

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| mHealth | Mobile Health |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| OTA | Over-The-Air |

| PPG | Photoplethysmography |

| RR | Respiration Rate |

| SpO2 | Peripheral Oxygen Saturation |

| TENGs | Triboelectric Nanogenerators |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

References

- Liu, S.; Qi, D.; Dong, H.; Meng, L.; Wang, Z.; Yin, X. Smart textile materials empowering automotive intelligent cockpits: An innovative integration from functional carriers to intelligent entities. J. Text. Inst. 2025, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D. Intelligent Cockpit Application Based on Artificial Intelligence Voice Interaction System. Comput. Inform. 2024, 43, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, D. Smart Cockpit Layout Design Framework Based on Human-Machine Experience. AHFE International. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics (AHFE 2023) 2023, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cao, D.; Tan, R.; Shi, T.; Gao, Z.; Ma, J.; Guo, G.; Hu, H.; Feng, J.; Wang, L. Intelligent Cockpit for Intelligent Connected Vehicles: Definition, Taxonomy, Technology and Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 3140–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conter, A.d.S.; Kapp, M.N.; Padilha, J.C. Health monitoring of smart vehicle occupants: A review. Rev. De Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2023, 40, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feehrer, C.E.; Baron, S. Artificial Intelligence for Cockpit Aids. IFAC Proc. Vol. 1985, 18, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Shi, W. Vehicle Computing: Vision and challenges. J. Inf. Intell. 2023, 1, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wang, G.; Jiang, T.; Ma, X.; Zhu, M. Research on a Multifunctional Vehicle Safety Assistant System Based on Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain Technology (AIBT), Zibo, China, 14–16 April 2023; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Hu, Z.; Ma, J. The Personality of the Intelligent Cockpit? Exploring the Personality Traits of In-Vehicle LLMs with Psychometrics. Information 2024, 15, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wei, W.; Ji, S.; Ruan, H.; Yi, F.; Jia, C.; Hu, D.; Tang, K. Research Progress in Multi-Domain and Cross-Domain AI Management and Control for Intelligent Electric Vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D.B.; Aderinto, N.; Clement David-Olawade, A.; Egbon, E.; Adereni, T.; Popoola, M.R.; Tiwari, R. Integrating AI-driven wearable devices and biometric data into stroke risk assessment: A review of opportunities and challenges. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2025, 249, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Z.; Li, W.-B.; Liu, Y.-J.; Zeng, G.-Z.; Li, C.-M.; Jin, H.-M.; Li, S.; Guo, G. AI-enabled intelligent cockpit proactive affective interaction: Middle-level feature fusion dual-branch deep learning network for driver emotion recognition. Adv. Manuf. 2024, 13, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z. The Current Development and Future Prospects of Autonomous Driving Driven by Artificial Intelligence. Comput. Artif. Intell. 2025, 2, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.C.; Liang, J.K. Exploring factors that influence the cardiovascular health of bus drivers for the improvement of transit safety. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2023, 29, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mase, J.M.; Chapman, P.; Figueredo, G.P. A Review of Intelligent Systems for Driving Risk Assessment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 5905–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R., D.; V., D.M.; T., B.S. Smart Health Monitoring and Emergency Assistance System for Drivers. Int. Sci. J. Eng. Manag. 2025, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, H.; Kamezaki, M.; Sugano, S. Toward Health–Related Accident Prevention: Symptom Detection and Intervention Based on Driver Monitoring and Verbal Interaction. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 2, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Martorell, S.; Olier, I.; Ohlsson, M.; Lip, G.Y.H. Advancing personalised care in atrial fibrillation and stroke: The potential impact of AI from prevention to rehabilitation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 35, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Farhan, M.; Saeed, Y.; Iqbal, M.J.; Ullah, F.; Srivastava, G. Enhancing driver attention and road safety through EEG-informed deep reinforcement learning and soft computing. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Warnecke, J.M.; Haghi, M.; Deserno, T.M. Unobtrusive Health Monitoring in Private Spaces: The Smart Vehicle. Sensors 2020, 20, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-F.; Loguercio, S.; Chen, K.-Y.; Lee, S.E.; Park, J.-B.; Liu, S.; Sadaei, H.J.; Torkamani, A. Artificial Intelligence for Risk Assessment on Primary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease. Curr. Cardiovasc. Risk Rep. 2023, 17, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, G.; Radev, H.; Shopov, M.; Kakanakov, N. A Taxonomy of Methods, Techniques and Sensors for Acquisition of Physiological Signals in Driver Monitoring Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zou, Y.; Li, Z.; Deng, Y. Advances in Portable and Wearable Acoustic Sensing Devices for Human Health Monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iarlori, S.; Perpetuini, D.; Tritto, M.; Cardone, D.; Tiberio, A.; Chinthakindi, M.; Filippini, C.; Cavanini, L.; Freddi, A.; Ferracuti, F.; et al. An Overview of Approaches and Methods for the Cognitive Workload Estimation in Human–Machine Interaction Scenarios through Wearables Sensors. BioMedInformatics 2024, 4, 1155–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Gao, D.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Du, B.; Zhang, S.; Qin, Y. A multimodal physiological dataset for driving behaviour analysis. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumitha, M.S.; Xavier, T.S. Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors—A brief review. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.A.K.; Suneel, S.; Nanthini, L.; Srivastava, S.S.; Veerraju, M.S.; Moharekar, T.T. IoT based Novel Design of Intelligent Healthcare Monitoring System with Internet of Things and Smart Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Gwalior, India, 27–28 July 2024; pp. 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, T.G.; Skourup, C.; Zhang, H. Using EEG for Mental Fatigue Assessment: A Comprehensive Look Into the Current State of the Art. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2019, 49, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, K.; Saha, T.; Ding, S.; Sandhu, S.S.; Chang, A.-Y.; Wang, J. Hybrid multimodal wearable sensors for comprehensive health monitoring. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cui, T.; Li, D.; Ji, S.; Chen, Z.; Shao, W.; Liu, H.; Ren, T.-L. Breathable Electronic Skins for Daily Physiological Signal Monitoring. Nano Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xue, N.; Zhou, W.; Qin, B.; Qiu, B.; Fang, G.; Sun, X. Recent Progress in Flexible Wearable Sensors for Real-Time Health Monitoring: Materials, Devices, and System Integration. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.G.; Devrakhyani, P.; Shetty, S.; Munji, D. Artificial Intelligence for Air Safety. In Proceedings of the European, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern Conference on Information Systems, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 25–26 November 2020; pp. 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweke, H.F.; Teh, Y.W.; Mujtaba, G.; Al-garadi, M.A. Data fusion and multiple classifier systems for human activity detection and health monitoring: Review and open research directions. Inf. Fusion 2019, 46, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S.; Selvaraj, J.; Sahayadhas, A. Detection and analysis: Driver state with electrocardiogram (ECG). Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2020, 43, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahayadhas, A.; Sundaraj, K.; Murugappan, M. Detecting Driver Drowsiness Based on Sensors: A Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 16937–16953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Seo, M.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.W. Fuzzy support vector machine-based personalizing method to address the inter-subject variance problem of physiological signals in a driver monitoring system. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 105, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, W.; Yeo, M.; You, J.; Lee, H.; Cho, T.; Hwang, B.; Park, C. Optimal Feature Search for Vigilance Estimation Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2020, 9, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.; Lee, C.; Yu, H.; Baek, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Park, C. Automatic Sleep Scoring Using Intrinsic Mode Based on Interpretable Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36895–36906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattar, M.; Govind, A.; Mainali, S. Artificial Intelligence Models for the Automation of Standard Diagnostics in Sleep Medicine—A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Tan, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Zeng, P.; Khan, M.; Das, S.K. Edge-computing-driven Internet of Things: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Rodriguez, E.; Pérez, M.A.; Torre-Bastida, A.I.; Senderos, C.R.; de López-Armentia, J. Edge intelligence secure frameworks: Current state and future challenges. Comput. Secur. 2023, 130, 103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabaharan, G.; Vidhya, S.; Chithrakumar, T.; Sika, K.; Balakrishnan, M. AI-Driven Computational Frameworks: Advancing Edge Intelligence and Smart Systems. Int. J. Comput. Exp. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Chatterjee, K. Edge computing based secure health monitoring framework for electronic healthcare system. Clust. Comput. 2022, 26, 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieni, B.; Ritchie, M.A.; Mandalari, A.M.; Boem, F. An Interdisciplinary Overview on Ambient Assisted Living Systems for Health Monitoring at Home: Trade-Offs and Challenges. Sensors 2025, 25, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Chouhan, A.V.; Wajeed, M.A.; Tiwari, S.; Bist, A.S.; Puri, S.C. Prediction of health monitoring with deep learning using edge computing. Meas. Sens. 2023, 25, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H. Edge Intelligence Computing Power Collaboration Framework for Connected Health. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on E-Health Networking, Application & Services (Healthcom), Chongqing, China, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, S.; Bittencourt, L.F.; da Fonseca, N.L.S. Resource management at the network edge for federated learning. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.; Monteiro, M.; Mattos, C.; Dias, M.; Soares, J.; Magalhães, R.; Macedo, J. Edge AI for Internet of Medical Things: A literature review. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 116, 109202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.; Sousa, P.; Mira da Silva, M. Maintenance of Enterprise Architecture Models. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2020, 63, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaidari, F.; Rahman, A.; Zagrouba, R. Cloud of Things: Architecture, applications and challenges. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 14, 5957–5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Sayed, H.E.; Malik, S.; Zia, T.; Khan, J.; Alkaabi, N.; Ignatious, H. Level-5 Autonomous Driving—Are We There Yet? A Review of Research Literature. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H.; Naqvi, S.S.A.; Iqbal, N.; Khan, M.A.; Qayyum, F.; Muhammad, F.; Khan, S.; Kim, D.-H. Analysis on the Driving and Braking Control Logic Algorithm for Mobility Energy Efficiency in Electric Vehicle. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2024, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Wang, L.; Gui, J.; Jiang, P.; Chen, X.; Zeng, F.; Wan, S. A review of 6G autonomous intelligent transportation systems: Mechanisms, applications and challenges. J. Syst. Archit. 2023, 142, 102929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoufi, P.; Hemmati, A.; Rahmani, A.M. Deep learning applications in the Internet of Things: A review, tools, and future directions. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 3621–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.; Cabral, A.T.; Bellini, B.; Facco Rodrigues, V.; da Rosa Righi, R.; André da Costa, C.; Barbosa, J.L.V. IoT-based vital sign monitoring: A literature review. Smart Health 2024, 32, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, J.A.; Shankar, A.; JR, A.N.; Gaur, P.; Kumar, S.S. Smart Non-Invasive Real-Time Health Monitoring using Machine Learning and IoT. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Smart Electronic Systems (iSES), Ahmedabad, India, 18–20 December 2023; pp. 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, D.; Garg, P.; Aldossary, S.M.; Shafi, J.; Kumar, S. A Linear Quadratic Regression-Based Synchronised Health Monitoring System (SHMS) for IoT Applications. Electronics 2023, 12, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Ling, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, K.; Guo, G. A systematic review on the current research of digital twin in automotive application. Internet Things Cyber Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Cruz, B.; Andreu-Perez, J.; Martínez, L. The cybersecurity mesh: A comprehensive survey of involved artificial intelligence methods, cryptographic protocols and challenges for future research. Neurocomputing 2024, 581, 127427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahiduzzaman, M.; Tasnim, M.; Newaz, N.T.; Kaiser, M.S.; Mahmud, M. Machine Learning Based Early Fall Detection for Elderly People with Neurological Disorder Using Multimodal Data Fusion. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2020, 12451, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Chakraborty, P. A review of driver gaze estimation and application in gaze behavior understanding. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.; Soni, A.; Soukane, A.; Cherif, A.R.; Rabat, A. Artificial intelligence modelling human mental fatigue: A comprehensive survey. Neurocomputing 2024, 567, 126999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 802.11p-2010; IEEE Standard for Information Technology—Telecommunications and Information Exchange Between Systems—Local and Metropolitan Area Networks—Specific Requirements—Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications Amendment 6: Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010.

- Su, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, R. A bibliometric analysis of blockchain development in industrial digital transformation using CiteSpace. Peer Peer Netw. Appl. 2024, 17, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Ge, X.; Li, J.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, R. Intelligent Cockpits for Connected Vehicles: Taxonomy, Architecture, Interaction Technologies, and Future Directions. Sensors 2024, 24, 5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liang, Y.; Shen, X.; Zheng, X.; Mahmood, A.; Sheng, Q.Z. Edge Computing and Sensor-Cloud: Overview, Solutions, and Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Garg, S.; Lin, H.; Piran, M.J.; Hu, J.; Hossain, M.S. Enabling Secure Authentication in Industrial IoT With Transfer Learning Empowered Blockchain. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 7725–7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalithadevi, B.; Krishnaveni, S. Efficient Disease Risk Prediction based on Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 29–31 2022; pp. 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, H.; Zhu, Z. Emotion Recognition and Multimodal Fusion in Smart Cockpits: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions. ITM Web Conf. 2025, 78, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kumari, S.; Senapati, A.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. New era of artificial intelligence and machine learning-based detection, diagnosis, and therapeutics in Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 90, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadena Zepeda, A.A.; García-Guerrero, E.E.; Aguirre-Castro, O.A.; Galindo-Aldana, G.M.; Juárez-Ramírez, R.; Gómez-Guzmán, M.A.; Raymond, C.; Inzunza-Gonzalez, E. Machine Learning-Based Approaches for Early Detection and Risk Stratification of Deep Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review. Eng 2025, 6, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T.; Tao, X.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Velásquez, J.D. A survey of multimodal information fusion for smart healthcare: Mapping the journey from data to wisdom. Inf. Fusion 2024, 102, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, F.; Ali, H.; Hajj, N.E.; Shah, Z. Artificial Intelligence-Based Methods for Fusion of Electronic Health Records and Imaging Data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, C.; Feng, H.; Huang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, R. A Review of Key Technologies for Emotion Analysis Using Multimodal Information. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 1504–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, D.; Jadaun, A. Driver drowsiness detection system using machine learning. YMER Digit. 2022, 21, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Ye, M.; Ma, A.J.; Yip, T.C.-F.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Yuen, P.C. Importance-aware personalized learning for early risk prediction using static and dynamic health data. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasanna Kumar, L.L.; Kumar, V.S.; Kumar, G.A.; Nagendar, Y.; Mohan, N.; Athiraja, A. AI-Driven Predictive Modeling for Early Detection and Progression Monitoring of Chronic Kidney Disease Using Multimodal Data. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Smart Technologies for Sustainable Development Goals (ICSTSDG), Chennai, India, 6–8 November 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnarao, S.; Wang, H.-C.; Sharma, A.; Iqbal, M. Enhancement of Advanced Driver Assistance System (Adas) Using Machine Learning. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2020, 1252, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Alaball, J.; Panadés Zafra, R.; Escalé-Besa, A.; Martinez-Millana, A. The artificial intelligence revolution in primary care: Challenges, dilemmas and opportunities. Aten. Primaria 2024, 56, 102820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, X.; He, B. Design and Optimization of Safe and Efficient Human-Machine Collaborative Autonomous Driving Systems: Addressing Challenges in Interaction, System Downgrade, and Driver Intervention. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Intelligent Manufacturing (AIIM), Chengdu, China, 20–22 December 2024; pp. 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz Butt, S.; Naseer, M.; Ali, A.; Khalid, A.; Jamal, T.; Naz, S. Remote mobile health monitoring frameworks and mobile applications: Taxonomy, open challenges, motivation, and recommendations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, H.; Lambert, S.B.; Barr, I.; Vardoulakis, S.; Bambrick, H.; Hu, W. Internet-based Surveillance Systems and Infectious Diseases Prediction: An Updated Review of the Last 10 Years and Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandhi, M.M.H.; Dunn, J.P. AI in medicine: Where are we now and where are we going? Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Gouqing, Z. Innovative application of artificial intelligence in a multi-dimensional communication research analysis: A critical review. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkaran, A.C.; Arabi, A.A. From understanding diseases to drug design: Can artificial intelligence bridge the gap? Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E.; Omenogor, C.E. AI powered predictive healthcare: Deep learning for early diagnosis, personalized treatment, and disease prevention. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2025, 14, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sudden Illness | Symptoms | Resulting Accident Types |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases (myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, heart failure) | Sudden chest pain, loss of consciousness, sudden cardiac arrest | Loss of braking/steering control, leading to straight-line collisions, rollovers, or rear-end collisions |

| Cerebrovascular diseases (cerebral infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage) | Sudden dizziness, hemiplegia, confusion | Vehicle drift out of lane, collisions with roadside facilities |

| Large aneurysm/aortic dissection | Sudden severe pain, loss of consciousness, sharp drop in blood pressure | Loss of control collision, missed braking opportunity |

| Diabetic acute complications (hypoglycemia, hyperglycemic crisis) | Sudden confusion, coma, visual impairment | Uncontrolled collisions, missed braking opportunity |

| Acute respiratory attacks (asthma, acute exacerbation of COPD) | Dyspnea, hypoxic unconsciousness | Loss of control and lane drift, collisions with roadside obstacles |

| Acute digestive system diseases (gastric ulcer perforation, acute abdominal pain) | Sudden severe pain, loss of attention | Loss of control of steering, sudden braking leading to rear-end collisions |

| Sleep apnea syndrome | Drowsiness, momentary loss of consciousness (microsleep) | Fatigue driving leading to rear-end collisions, rollover |

| Others (sudden pain, syncope) | Sudden dizziness, blurred vision, loss of balance | Multiple types (loss of control, collisions) |

| Sensors | Signal Types | Suitability | Technical Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seat pressure sensor array | Pressure distribution, contact area changes | Medium | Captures body posture changes in real time; supports long-term monitoring | Affected by seat material and sitting posture (signal vulnerable to vibration interference) |

| Seat ECG dry electrode | Heart rate variability data | Medium | High signal stability; enables continuous cardiac activity monitoring; assesses stress levels | Requires continuous contact; clothing obstruction reduces signal quality |

| Seat Side GSR Sensor | Skin conductance changes | Low | Fast response for emotional state assessment | Susceptible to environmental temperature and humidity; individual skin condition differences may cause data deviation |

| Steering wheel PPG + ECG module | Optical pulse signal, ECG signal | High | Natural usage, non-invasive | Requires continuous grip; signal loss when hands are off the wheel |

| Steering wheel grip force sensor | Grip strength changes, pressure distribution | High | High sensitivity; triggers fatigue warnings rapidly | Greatly affected by driving habits; potential sensor wear with long-term use |

| Smart textile sensor | Pressure, body temperature, ECG, EMG, respiration, pulse, etc. | High | High comfort, supports multimodal signal synchronous acquisition | Performance degradation after long-term washing; maintenance requires overall fabric replacement; currently high cost |

| Camera (RGB/NIR) | Facial expressions, eye movements, blinking, yawning and behavioral features | High | High comfort; supports synchronous acquisition of multimodal signals | Heavily affected by lighting; easily occluded; privacy concerns exist |

| Camera (PPG) | Pulse extraction through facial color changes | Low | Completely non-contact, can be analyzed synchronously with expressions | Extremely sensitive to motion and lighting changes, low accuracy |

| Millimeter-wave radar | Remote acquisition of respiratory, heart rate | Medium | Unaffected by lighting; can penetrate clothing | Susceptible to interference, complex algorithms, accuracy needs improvement |

| Infrared thermal imaging | Monitoring skin temperature, respiratory heat flux | Low | Works in complete darkness | Relatively high cost, limited resolution |

| Technical Module | Function Description | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Edge computing | Deploys computing resources on the in-vehicle or base station side, reducing network latency to the millisecond level and enhancing real-time response capabilities | [39,40] |

| In-vehicle AI accelerator | Enabling high-speed feature extraction and health status assessment | [44] |

| Real-time physiological signal warning | Performs denoising, filtering, and inference on drivers’ biological signals (e.g., heart rate, posture), supporting real-time physiological analysis and millisecond-level health risk alert triggering | [45] |

| Task scheduling and model offloading | Dynamically determining execution on end, edge, or cloud nodes based on computational complexity and latency requirements to optimize resource utilization | [46,47] |

| Cloud–edge collaboration | Cloud nodes handle large-scale data storage and model training; edge nodes take charge of real-time inference and desensitized data reporting | [50,51] |

| IoT interconnection | Implementing unified protocols to enable interconnection of in-vehicle and external sensors and actuators | [55] |

| Digital twin | Constructs virtual cabin models to map sensor data in real time, supporting predictive maintenance and system optimization | [57] |

| Zero-trust security model | Implementing identity authentication and trust evaluation for each access to ensure in-vehicle network and data security | [59] |

| Source | Category | Data | Application Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-cabin | Driver physiological signals | Heart rate, blood pressure, blood oxygen, body temperature, electromyographic signals | Assess health status, identify cardiovascular events, epilepsy and other sudden illness risks |

| Driver behavior data | Eye movement trajectory, facial expression features, steering operation frequency, voice intonation changes | Determine fatigue level, distraction status and emotion classification, predict driving risks | |

| Vehicle dynamic data | Real-time speed, acceleration curve, brake pedal stroke, steering angle | Optimize driving comfort with environmental data, implement active intervention | |

| Cabin exterior | Cabin environment data | Temperature, humidity, PM2.5 concentration, CO2 content | Adjust air conditioning, seat ventilation and other comfort configurations |

| Traffic environment information | Real-time traffic flow, road curvature, friction coefficient, weather warnings, accident black spots | Achieve environmental perception, path planning and risk warning | |

| Integration and management platform | V2X communication data | Inter-vehicle distance, traffic light status, pedestrian crossing warnings | Adjust speed/braking strategies; optimize comfort control |

| Multimodal features | Edge computing for data cleaning, preprocessing and feature extraction | Serve as input for deep learning models; support hybrid attention weight distribution | |

| Storage/Security layer | Blockchain ledger, encrypted storage | Data integrity, privacy protection, traceability | |

| Cloud analysis | Large model training, long-term trend learning | Disease detection and chronic condition assessment |

| Technical Module | Functional Description |

|---|---|

| Technical challenges | Camera sensors: Prone to interference from motion artifacts, lighting conditions and other factors, leading to insufficient detection accuracy. |

| Non-contact radar/infrared thermography: Performance is limited under harsh weather conditions. | |

| Deep learning models: The “black box” nature causes poor interpretability and low user trust. | |

| Model generalization: Insufficient adaptability across different populations and scenarios. | |

| Multimodal data fusion: Heterogeneity issues lead to difficulties in feature alignment/fusion, paired with limited real-time performance. | |

| Edge computing resources: Constrained hardware makes it hard to run high-precision AI models within millisecond-level latency. | |

| Ethical, privacy, and legal challenges | Data compliance: A large volume of health and biometric data must meet regional regulations (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA). |

| Alert accuracy: High risk of false positives/negatives, requiring error rate reduction. | |

| Human–machine interaction: Need for transparent, interpretable interaction methods to build user trust. | |

| Liability division: Unclear accountability when emergency intervention causes accidents. | |

| Future research opportunities | Driver cognitive digital twin: Construct a “cognitive digital twin” for drivers to enable precise risk prediction. |

| Integration with autonomous driving: Deeply integrate with L3 autonomous driving to trigger automatic switching or emergency parking when driver health abnormalities occur. | |

| Non-contact sensor deployment: Integrate new non-contact sensors into seats, steering wheels, etc. | |

| Data standardization: Promote unified data interfaces, protocols and formats to realize cross-brand/cross-platform interconnection. | |

| Smart healthcare collaboration: Partner with smart healthcare providers to share transit health data in real time and offer personalized travel recommendations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ye, D.; Liu, K.; Luo, C.; Hu, N. AI-Driven Smart Cockpit: Monitoring of Sudden Illnesses, Health Risk Intervention, and Future Prospects. Sensors 2026, 26, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010146

Ye D, Liu K, Luo C, Hu N. AI-Driven Smart Cockpit: Monitoring of Sudden Illnesses, Health Risk Intervention, and Future Prospects. Sensors. 2026; 26(1):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010146

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Donghai, Kehan Liu, Chenfei Luo, and Ning Hu. 2026. "AI-Driven Smart Cockpit: Monitoring of Sudden Illnesses, Health Risk Intervention, and Future Prospects" Sensors 26, no. 1: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010146

APA StyleYe, D., Liu, K., Luo, C., & Hu, N. (2026). AI-Driven Smart Cockpit: Monitoring of Sudden Illnesses, Health Risk Intervention, and Future Prospects. Sensors, 26(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/s26010146