4.2. Dataset

We created a new dataset called the Multi-Angle Smoking Detection Dataset, and it has 4847 smoking behavior pictures gathered from public places. Different complicated situations, such as sandstorms and hazy weather, are included so that the model can be more adaptable. We used LabelImg for image annotation and saved the annotations in XML format. Then, we converted them into YOLOv11-compatible txt files through a script. The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets at an 8:1:1 ratio. In order to improve the robustness of our model, we applied different combinations of data augmentation techniques randomly on the training set. These techniques include horizontal/vertical flip, non-uniform scale, random shift, perspective transform, and random crop. All experiments were performed with training from scratch; no pre-trained weight was used. The dataset employs a single-class detection framework (nc = 1), with the class label “Smoke”. We define the “Smoke” class as the localized region where active smoking occurs, specifically encompassing the cigarette and the fingers holding it. The bounding box annotation focuses on this critical region rather than the entire person, enabling more precise detection while reducing false positives. Annotations were created using LabelImg and saved as XML files; then, they were converted to YOLOv11-compatible txt files with normalized coordinates [class_id, x_center, y_center, width, height], where class_id = 0 represents the “Smoke” class.

Dataset Features and Challenges: To give a full view of how complex the dataset is, we examine the main characteristics. All pictures have been resized to 640 × 640 pixels so that they can be used as inputs for the model. The dataset contains smoking behavior captured at different distances ranging from 5 to 30 m, with a focus on closer ranges (5–10 m), which are typical operating areas for workers in oilfield settings. The environmental conditions are varied. There are sunny days, smoggy days, sandstorms, and rainy or foggy days. Lighting conditions range from natural sunlight to low light during dawn/dusk and artificial lighting at night. The dataset has many issues, such as partial occlusion caused by objects, buildings, or other people, as well as crowded scenes with many people and person-to-person occlusions. Camera perspectives include front-facing views, side views, and elevated surveillance angles to capture a variety of monitoring scenarios. These features make this dataset representative of real-world oilfield surveillance situations and suitable for testing robust detection models.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The experiment employs some key indicators of object detection [

58]. Precision (P) is the ratio of the number of true positive predictions to the total number of positive predictions (Equation (10)), while recall (R) is the ratio of the number of true positive predictions to the sum of the number of true positive predictions and the number of false negative predictions (Equation (11)), where TP, FP, and FN represent true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Average precision (AP) is computed by finding the area under the precision–recall curve using interpolation; a higher AP indicates better detection results. The mean average precision (mAP) is obtained by taking the average of AP over all categories, as given in Equation (12), where N is the total number of categories, and AP

i represents the average precision for the i-th category. Specifically, mAP@0.50 assesses the most basic localization performance at a single IoU threshold of 0.5, where a detection is considered correct if the overlap between the predicted and ground truth bounding box is greater than 50%. On the contrary, mAP@0.50:0.95 [

59] provides a full picture of localization robustness by averaging mAPs calculated at 10 IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 with steps of 0.05 (Equation (13)), where j represents the IoU threshold value at 0.05 intervals, and mAP_(IOU =

j) denotes the mAP calculated at threshold

j. Also, it is evaluated by FPS (frames per second), which means how fast it can process images in real time, and Params, which means how many parameters the model has, showing how complex the model is:

4.4. Ablation Studies

To verify if every single part was effective, we conducted ablation studies [

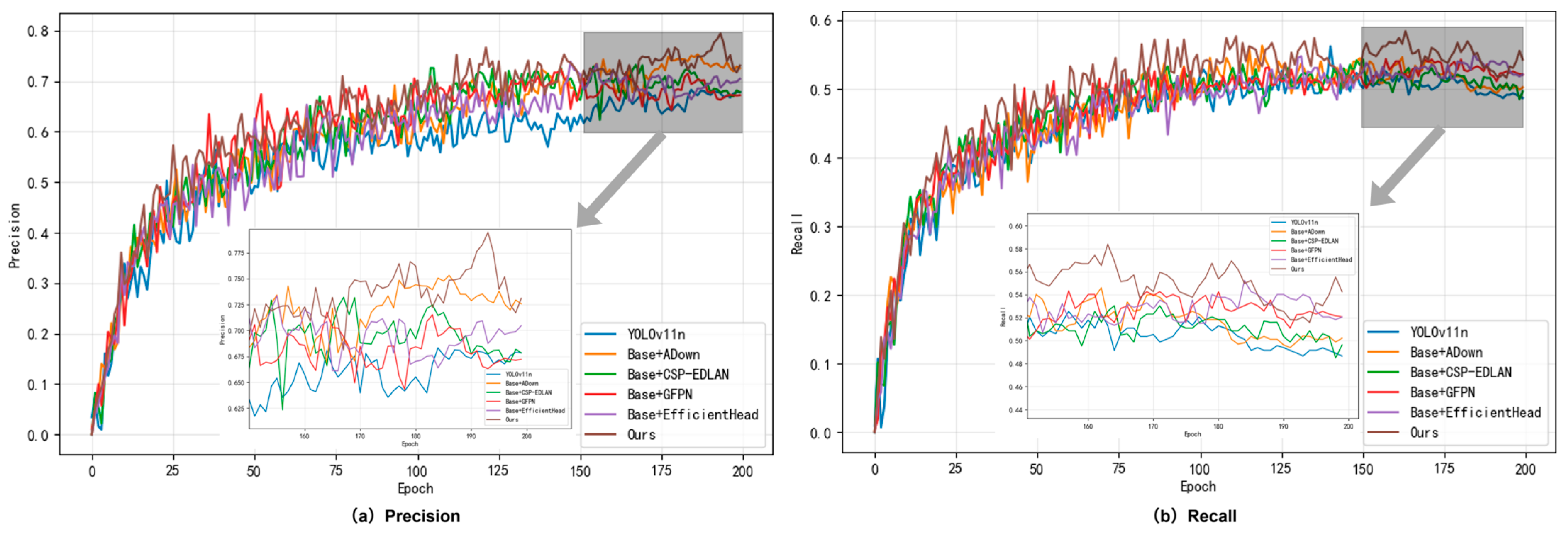

60] on YOLOv11n by starting from no module and adding them one at a time. As can be seen from

Table 4 and

Figure 7, performance improves progressively with each module added.

Baseline + ADown: Incorporating ADown independently enhanced precision from 0.614 to 0.701 (+14.2%) and also improved mAP@0.5 by 1.4% and mAP@0.5:0.95 by 2.8%. It notably reduced parameters by 19.23%, which demonstrated dual benefits for feature selection and model compression.

Baseline + CSP-EDLAN: This module significantly enhanced feature representation. It achieved 6.8% improvement on precision, 4.7% improvement on mAP@0.5, and 6.4% improvement on mAP@0.5:0.95 without sacrificing speed. The model maintained a high inference speed of 259.0 FPS due to the efficient reuse of features using dense connections.

Baseline + EfficientHead: EfficientHead enhances precision with only a small number of additional parameters by 5.7%, and recall was enhanced by 2.3%, which demonstrates that lightweight detection heads can effectively detect objects without introducing excessive complexity.

Baseline + GFPN: GFPN excelled at fusing features from different scales, improving mAP@0.5:0.95 by 9.6% and mAP@0.5 by 5.5%. Although there was an increase in computational cost, it proved to be highly effective for small objects and multiscale detection.

To investigate how modules interact and work together, we systematically analyzed representative pairs and groups of two and three modules. In terms of dual-module configuration, ADown + CSP-EDLAN demonstrated superior synergy between efficient downsampling and enhanced feature learning. It achieved a precision of 0.703 and mAP@0.5 of 0.543 with only 2.0M parameters, representing a 14.5% improvement on precision. ADown + EfficientHead achieved optimal compression at 1.8M params and 30.8% reduction, yet it maintained sufficient accuracy for demonstrating that lightweight designs were feasible. Notably, EfficientHead + GFPN attained the highest precision at 0.741 but a lower recall at 0.465, which indicates a bias towards precision over recall. For the triple-module configuration, ADown + CSP-EDLAN + EfficientHead achieved an optimal balance, with a precision of 0.711, a recall of 0.545, and 249.3 FPS, demonstrating an effective combination of lightweight design and detection capabilities. ADown + CSP-EDLAN + GFPN yielded the highest mAP@0.5 of 0.569 among the three-module combinations, which was 11.6% higher compared to CSP-EDLAN + EfficientHead + GFPN without ADown, requiring substantially more computational resources with 9.1 FLOPs and 3.9M params and confirming ADown’s importance for model efficiency. These ablation results provide three significant insights: First, ADown consistently reduces the number of parameters without compromising accuracy, thereby enabling more compact models that maintain performance. Second, GFPN appears in most combinations that achieve the greatest improvement in mAP@0.5:0.95, despite its higher computational cost. Third, the configurations based on CSP-EDLAN maintain the highest inference speed, with CSP-EDLAN + EfficientHead reaching 274.3 FPS, which enables real-time applications.

Synergistic Effect Analysis: Full integration achieved the best result with precision at 0.742, recall at 0.555, mAP@0.5 at 0.587, and mAP@0.5:0.95 at 0.255, which improved by 20.8%, 6.9%, 15.1%, and 17.0% compared to the baseline. Most importantly, it demonstrates that the whole model is superior to every combination of parts, which indicates that the different parts work collaboratively instead of interfering with one another [

48]. With 3.4M parameters and 181.9 FPS, it achieves an optimal trade-off among accuracy, efficiency, and real-time performance. Ablation studies quantitatively validate both the effectiveness of individual modules and the synergies between them, thus validating the choice of fusion architecture for the object detection task.

Statistical Validation: To ensure reliability, each configuration was evaluated over three independent runs with different random seeds (29,11,2025). All experiments converged successfully with standard deviations below 0.01 for all metrics, demonstrating stable performance. The 95% confidence intervals for relative improvements of the full model over baseline are as follows: precision [+20.0%, +21.6%], mAP@0.5 [+14.4%, +15.8%], and mAP@0.5:0.95 [+16.2%, +17.8%], all entirely above zero (p < 0.001). No training failures or significant outliers were observed across 48 total experimental runs (16 configurations × 3 repetitions), confirming the robustness and reproducibility of our results.

4.5. Downsampling Module Comparison

To verify whether ADown was superior to other downsampling modules, we conducted a comparison experiment on the downsampling module. In the GCEA-YOLO model, we compared the performance of six different downsampling modules, which are SPD-Conv, MixDown, HWD, LDConv, ContextGuidedDown, and ADown. From

Table 5, we can observe that the ADown module has the optimal overall accuracy with

p = 0.742, R = 0.555, mAP@0.5 = 0.587, and mAP@0.5:0.95 = 0.255, and it requires only 7.8GFLOPs of computation and 3.4M parameters, which is the lowest computational cost compared to all other methods.

Compared to SPDConv with the second highest precision, ADown improves precision by 1.6%, recall by 10.1%, mAP@0.5 by 5.6%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 by 9.9%, and it reduces computational cost and parameters by 43.5% and 48.5%, respectively. Compared with MixDown with the second highest mAP@0.5:0.95, ADown has 3.7% improvement. Compared to the lightweight LDConv, ADown improves on mAP@0.5:0.95 by as much as 60.4%, demonstrating the optimal balance of accuracy vs. efficiency. From the experiments, we can observe that ADown achieves the best detection result with the lowest computational cost, confirming its superior and effective performance in the lightweight object detection task.

From

Figure 8, we can observe that this paper conducts a comparison of six different downsampling modules over 200 training epochs.

Figure 8a,b show the convergence curve of the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics, respectively. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed ADown module has superior overall performance during the whole training process. It not only converges faster than other methods but also achieves significantly higher final accuracy. On the contrary, the performance curves of the SPDConv, MixDown, HWD, LDConv, and ContextGuidedDown modules are still relatively low, and the ContextGuidedDown module has the worst detection accuracy. This visual analysis clearly demonstrates the complete superiority of the ADown module in terms of convergence behavior, training stability, and final performance. This confirms that it works effectively for lightweight object detection.

4.6. Comparison Experiments

In order to fully evaluate GCEA-YOLO’s capabilities, we conducted comparisons with the latest detectors that include two-stage methods, such as Faster R-CNN; single-stage detectors, such as SSD; and YOLO series models, such as YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv12n, as shown in

Table 6. In terms of precision and recall under identical experimental conditions, GCEA-YOLO demonstrates obvious superiority: It achieves 0.742 for precision and 0.555 for recall, surpassing all compared YOLO-series models in both metrics. Not to mention, GCEA-YOLO achieves an mAP@0.5 of 0.587, which is significantly better than the best YOLO variant at 0.516. It also achieves an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.255, which is 17% higher than the YOLOv11n baseline. More importantly, as observed in

Table 6, GCEA-YOLO has superior detection accuracy and is also efficient. With just 3.4M parameters and 7.8 GFLOPs in computational cost, it has 88% less parameters than Faster R-CNN, but it still achieves 181.9 FPS inference speed, satisfying the real-time requirement.

The results demonstrate that using CSP-EDLAN, ADown, EfficientHead, and GFPN modules works effectively, which indicates that our fusion strategy achieves superior performance for smoking detection. It provides an optimal balance of accuracy and speed for real-world applications.

4.7. Generalizability Validation on Public Dataset

Model generalization refers to the capability of a machine learning model to perform well on previously unseen data. This is crucial when we want to determine if a model can be used in practice. Strong generalization is essential to improve detection accuracy, avoid overfitting, and guarantee reliability in actual deployment.

To verify the generalization performance of GCEA-YOLO, we conducted thorough assessments using the Smoking Detection Dataset, which comprises 18,230 high-quality annotated images divided into training (16,758 images, 91.9%), validation (740 images, 4.1%), and testing sets (732 images, 4.0%). As shown in

Table 7, we compared GCEA-YOLO with some state-of-the-art detectors such as SSD, YOLOv3, YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv10, YOLOv12, and Faster R-CNN. From experimental results, it can be observed that GCEA-YOLO has superior overall performance compared to other models, with mAP@50 at 88.8%, precision at 88.3%, and recall at 79.6%. Our method stands out by achieving an optimal balance between computational efficiency, model complexity, and detection accuracy, thus confirming the remarkable generalization ability of the proposed fusion structure.

To validate the generalization ability of GCEA-YOLO, we conducted comparative experiments using public datasets. The experiments used the COCO2017 dataset [

62]. Because of the lack of computing power, we chose 8000 pictures as the training set, 1000 pictures as the validation set, and 1000 pictures as the testing set at random. GCEA-YOLO was compared to the basic model.

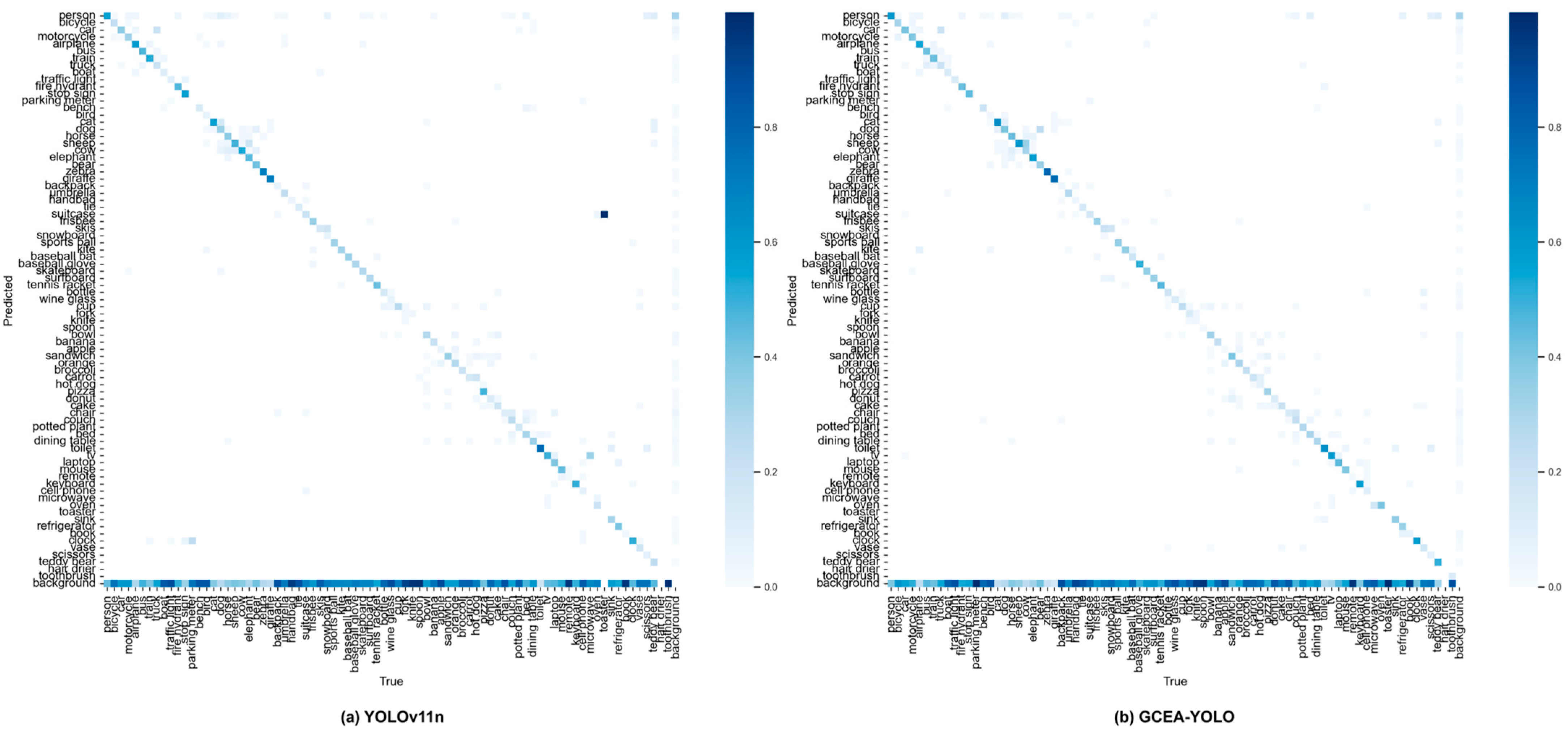

YOLOv11n: From

Table 8, we can observe that, from the experimental results, GCEA-YOLO achieved better results than YOLOv11n in every metric: mAP@50 = 32.6%; precision = 45.9%; recall = 32.4%. As shown in

Figure 9, the normalized confusion matrix provides details about each class’s detection performance. The increased diagonal intensity in

Figure 9b indicates that GCEA-YOLO has higher classification accuracy over 80 object classes than YOLOv11n, which is shown in

Figure 9a. Also noteworthy is that there is less confusion between classes in our model, especially those that are visually alike, such as cat/dog and car/truck, and fewer instances of backgrounds being classified as objects. This visualization result demonstrates again that our approach ensures computational efficiency and maintains moderate complexity, yet it still achieves accurate detection, confirming the effectiveness of our proposed fusion architecture.

In order to further demonstrate the generalization ability of the proposed model, real-world field tests have been conducted. Data were obtained using explosion-proof HD cameras made especially for oilfields. The experimental results demonstrate that the model performs effectively in actual situations and has strong generalization ability. Representative field test results are shown in

Figure 10.