Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Single Lumbar-Mounted IMU System for Gait Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

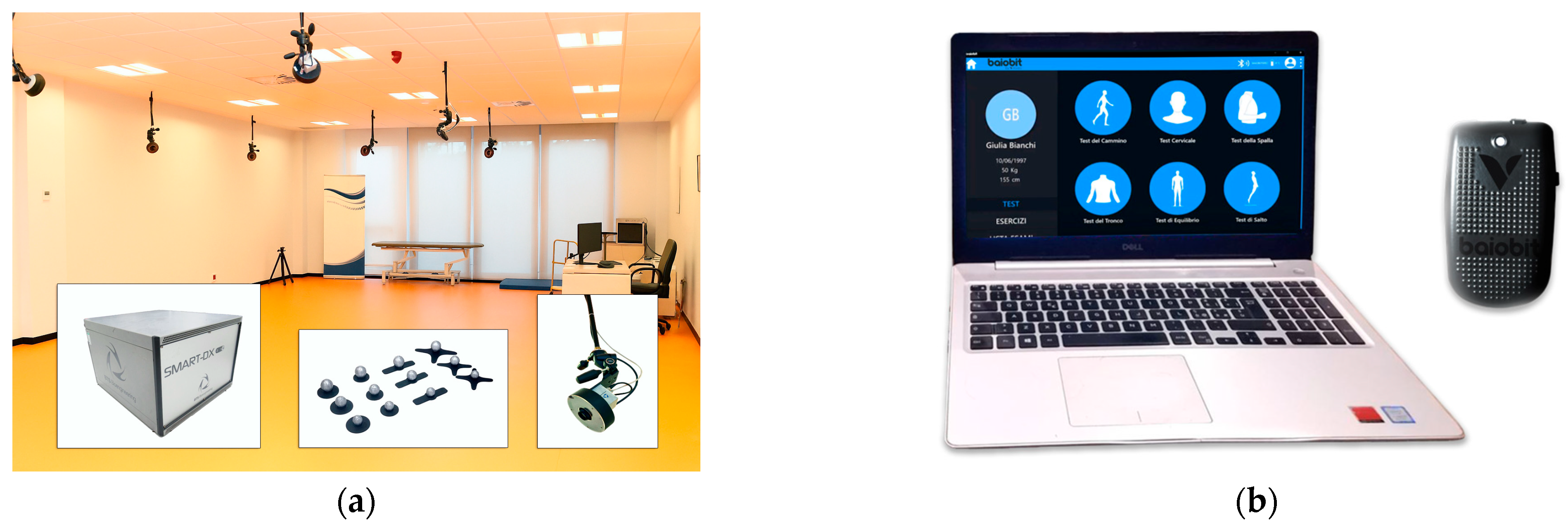

2.1. Instrumentation

2.1.1. Three-Dimensional Optoelectronic System

2.1.2. Wearable Inertial System

2.2. Study Design and Study Population

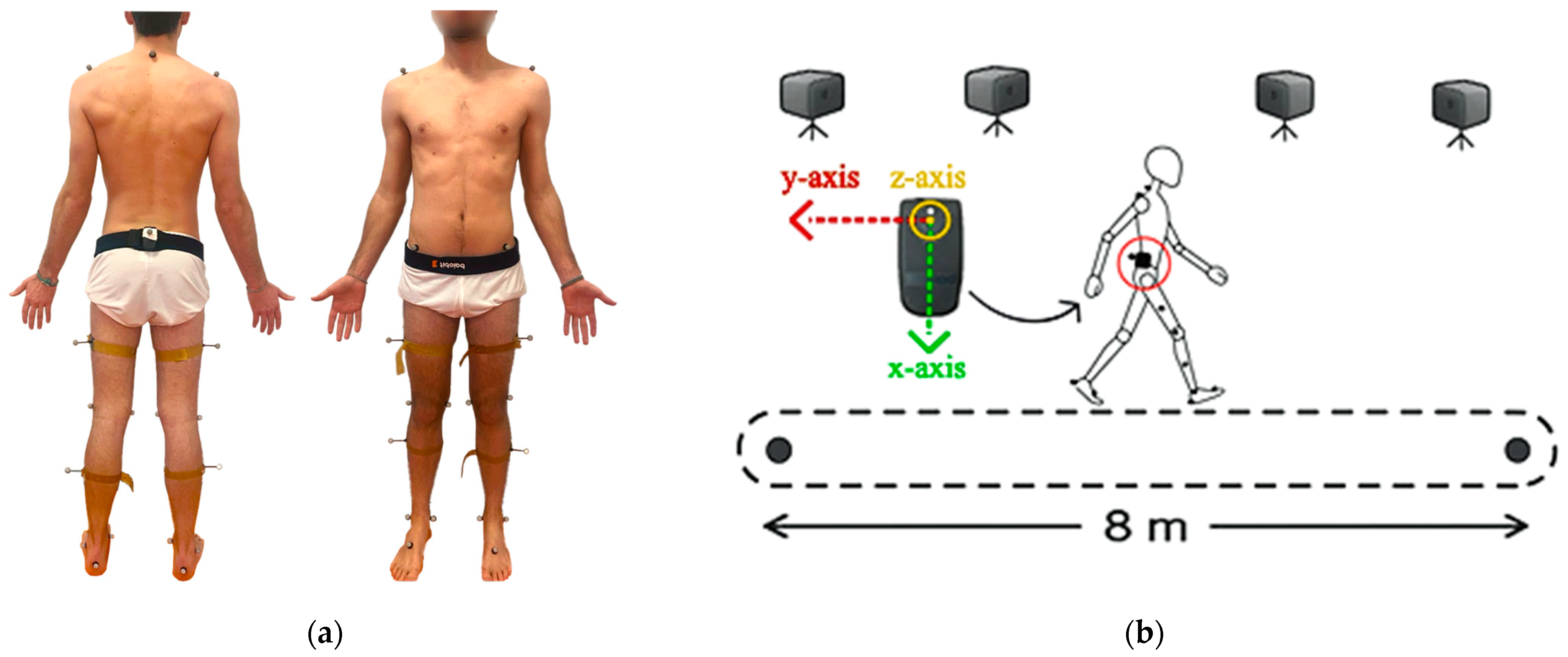

2.3. Sensor Equipment and Data Acquisition

- Cadence [steps/min]: Stepping rate (1);

- Stride length [m]: Distance between two consecutive foot falls at the moments of initial contacts (2);

- Step length [m]: Distance between the initial contact of one foot and the initial contact of the opposite foot (3);

- Velocity [m/s]: Walking speed (4);where

- Swing phase [%GCT]: Average percentage of a gait cycle that either foot is off the ground (5);

- Stance phase [%GCT]: Average percentage of a gait cycle that either foot is on the ground (6);

- Single support phase [%GCT]: Average percentage of a gait cycle spent with only one foot on the ground (7);

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Intra-Rater Reliability

3.2. Inter-Rater Reliability

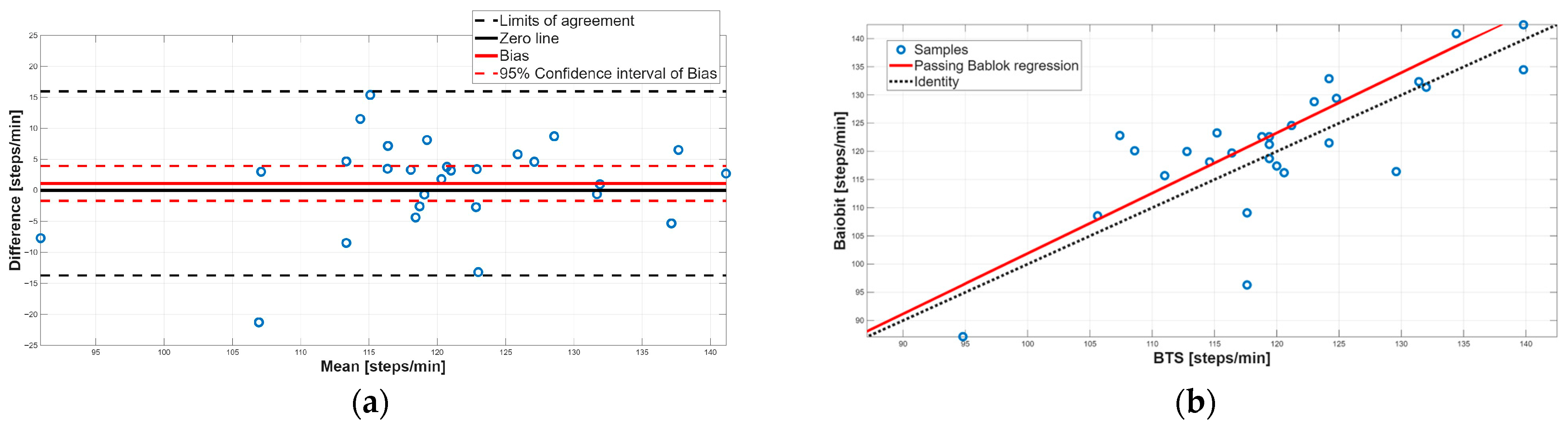

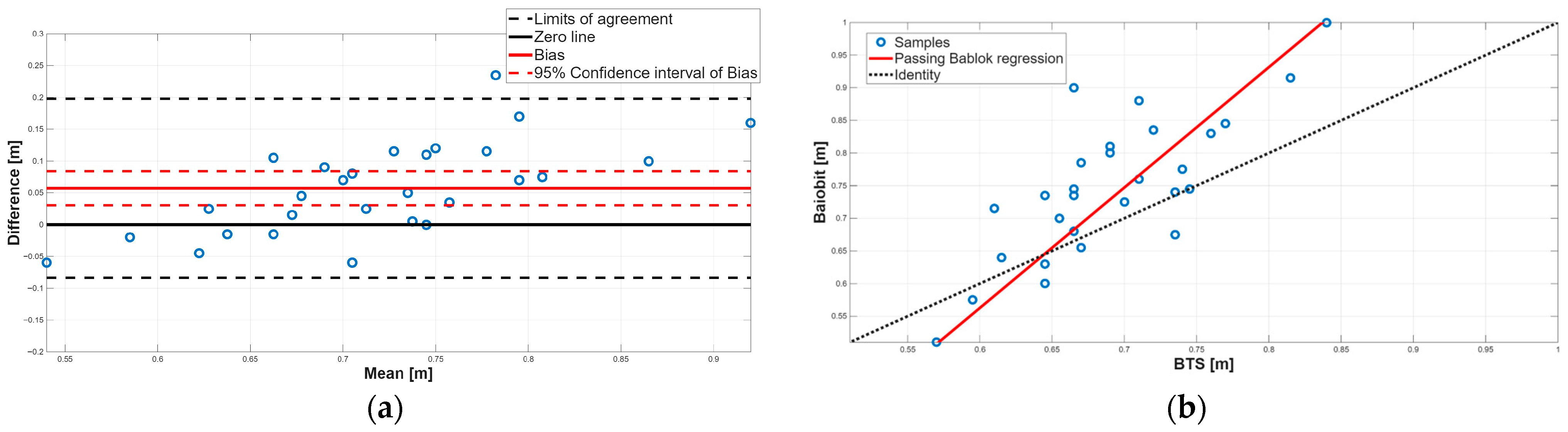

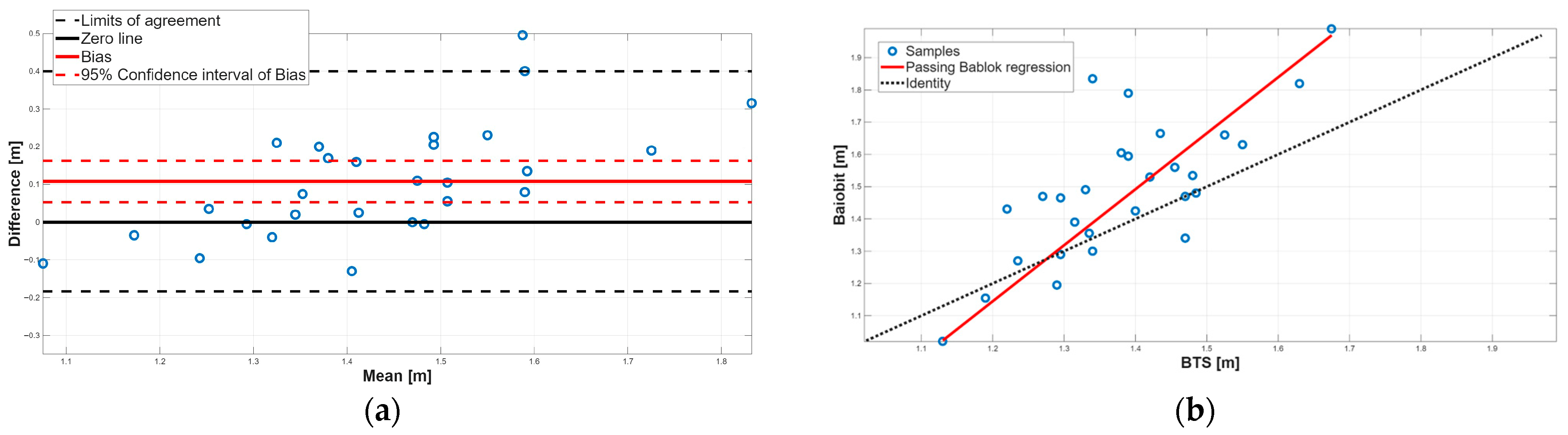

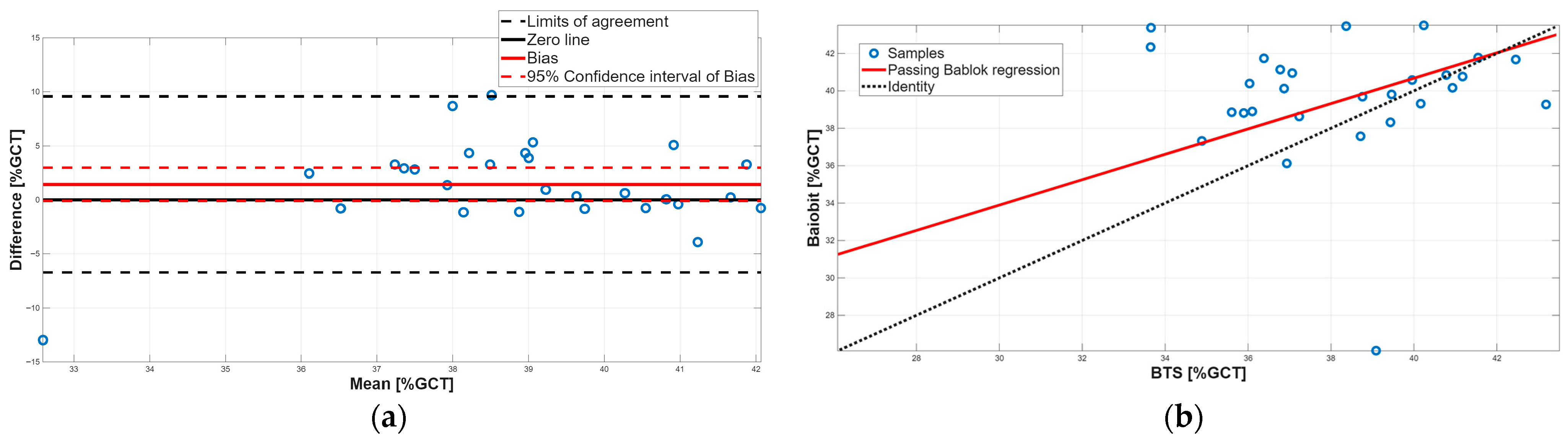

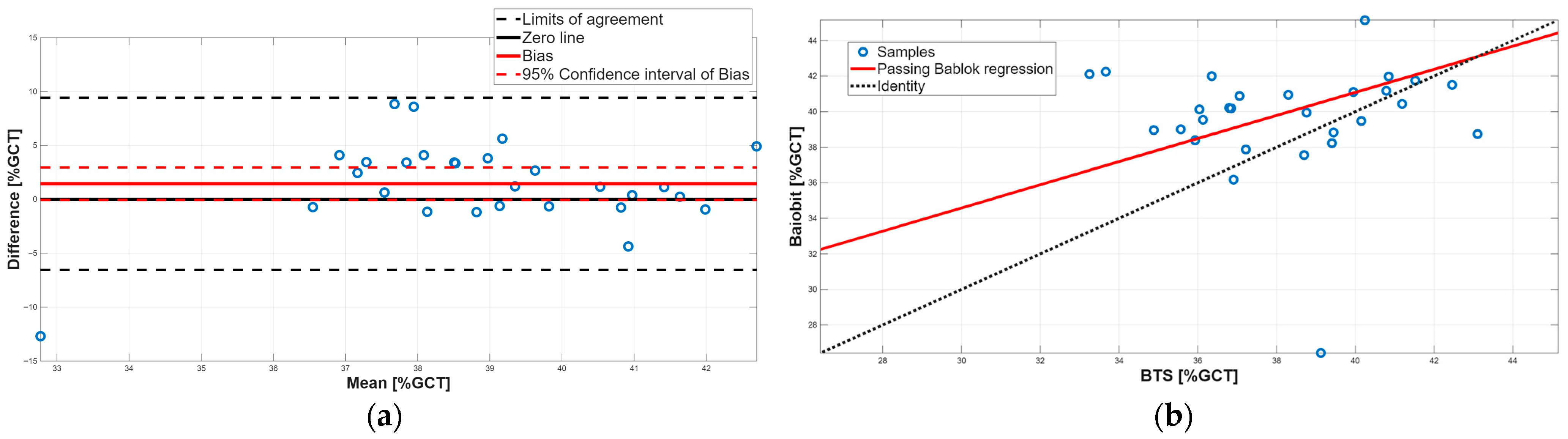

3.3. Concurrent Validity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BA | Bland–Altman |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| GCT | Gait cycle time |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation |

| IMU | Inertial measurement unit |

| LOA | Limit of agreement |

| MDC | Minimum detectable change |

| m | Slope |

| PB | Passing–Bablok |

| q | Intercept |

| r | Spearman correlation |

| SEM | Standard error of measurement |

References

- Miller, F. Cerebral Palsy, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 251–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, L.; Demers, M. A Novel, Wearable Inertial Measurement Unit for Stroke Survivors: Validity, Acceptability, and Usability. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 105, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, G.; Cesarelli, M. An automatic approach to assess biomechanical risk using machine learning algorithms and inertial sensors. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donisi, L.; Cesarelli, G. A logistic regression model for biomechanical risk classification in lifting tasks. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R. Introduction to Sports Biomechanics, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Houmanfar, R.; Karg, M. Movement Analysis of Rehabilitation Exercises: Distance Metrics for Measuring Patient Progress. IEEE Syst. J. 2016, 10, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Arya, K.N. Understanding gait control in post-stroke: Implications for management. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2012, 16, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scataglini, S.; Abts, E. Accuracy, Validity, and Reliability of Markerless Camera-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems versus Marker-Based 3D Motion Capture Systems in Gait Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipari, D.; Chaparro-Rico, B.D.M. SANE (Easy Gait Analysis System): Towards an AI-Assisted Automatic Gait-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, A.; West, A.M. Comparative abilities of Microsoft Kinect and Vicon 3D motion capture for gait analysis. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2014, 38, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailo, G.; Saibene, F.L. Characterization of Walking in Mild Parkinson’s Disease: Reliability, Validity and Discriminant Ability of the Six-Minute Walk Test Instrumented with a Single Inertial Sensor. Sensors 2024, 24, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guignard, B.; Ayad, O. Validity, reliability and accuracy of inertial measurement units (IMUs) to measure angles: Application in swimming. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 1471–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, F.A.; Callaway, A.J. Validity and reliability of inertial measurement units used to measure motion of the lumbar spine: A systematic review of individuals with and without low back pain. Med. Eng. Phys. 2024, 126, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manupibul, U.; Tanthuwapathom, R. Integration of force and IMU sensors for developing low-cost portable gait measurement system in lower extremities. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spina, S.; Facciorusso, S. Sensor based assessment of turning during instrumented Timed Up and Go Test for quantifying mobility in chronic stroke patients. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizagaray-García, I.; Gil-Martínez, A. Inter, intra-examiner reliability and validity of inertial sensors to measure the active cervical range of motion in patients with primary headache. EXCLI J. 2021, 20, 879–893. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.; Ortlieb, C. Reliability of IMU-Derived Temporal Gait Parameters in Neurological Diseases. Sensors 2022, 22, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathunny, J.J.; Karthik, V. A scoping review on recent trends in wearable sensors to analyze gait in people with stroke: From sensor placement to validation against gold-standard equipment. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2023, 237, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Romo-Pérez, V. Identification of body balance deterioration of gait in women using accelerometers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, G.; Cesarelli, G. Validity of a Novel Algorithm to Compute Spatiotemporal Parameters Based on a Single IMU Placed on the Lumbar Region. Sensors 2025, 25, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, G.; Pirozzi, M.A. Validity of wearable inertial sensors for gait analysis: A systematic review. Diagnostics 2024, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufl, W.; Lorenz, M. Towards inertial sensor based mobile gait analysis: Event-detection and spatio-temporal parameters. Sensors 2018, 19, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimolin, V.; Capodaglio, P. Computation of spatio-temporal parameters in level walking using a single inertial system in lean and obese adolescents. Biomed. Eng./Biomed. Tech. 2017, 62, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, M.; Sforza, C. Gait evaluation using inertial measurement units in subjects with Parkinson’s disease. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2018, 42, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digo, E.; Panero, E. Comparison of IMU set-ups for the estimation of gait spatio-temporal parameters in an elderly population. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2022, 237, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, C.; Pisani, N. Agreement between Optoelectronic System and Wearable Sensors for the Evaluation of Gait Spatio-temporal Parameters in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. Sensors 2023, 23, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziagkas, E.; Loukovitis, A. A novel tool for gait analysis: Validation study of the smart insole Podosmart®. Sensors 2021, 21, 5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggio, G.; Tombolini, F. Technology-based complex motor tasks assessment: A 6-DOF inertial-based system versus a gold-standard optoelectronic-based one. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, R.; Lebleu, J. Concurrent validity of a commercial wireless trunk triaxial accelerometer system for gait analysis. J. Sport Rehabil. 2019, 28, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liang, Z.X. Reliability of BTS three-dimensional motion capture system in gait analysis. Chin. J. Tissue Eng. Res. 2018, 22, 3665. [Google Scholar]

- Camuncoli, F.; Barni, L. Validity of the Baiobit Inertial Measurements Unit for the assessment of vertical double- and single-leg countermovement jumps in athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, A.; Eliasziw, M. Sample size requirements for reliability studies. Stat. Med. 1987, 6, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.D.; Eliasziw, M. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat. Med. 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.D.; Ghoussayni, S.N. A six degrees-of-freedom marker set for gait analysis: Repeatability and comparison with a modified Helen Hayes set. Gait Posture 2009, 30, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passing, H.; Bablok, W. A new biometrical procedure for testing the equality of measurements from two different analytical methods. Application of linear regression procedures for method comparison studies in clinical chemistry. Part, I. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 1983, 21, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavarina, D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem. Medica 2015, 25, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. Measures of reliability in sports medicine and science. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.M.; Hornby, T.G. Minimal detectable change for spatial and temporal measurements of gait after incomplete spinal cord injury. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2012, 18, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Luzi, S. Concurrent validity of a trunk tri-axial accelerometer system for gait analysis in older adults. Gait Posture 2009, 29, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, M.; Lund, H. Test–retest reliability of trunk accelerometric gait analysis. Gait Posture 2004, 19, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, A.; Del Din, S. Instrumenting gait with an accelerometer: A system and algorithm examination. Med. Eng. Phys. 2015, 37, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugané, F.; Benedetti, M.G.; Casadio, G.; Attala, S.; Biagi, F.; Manca, M.; Leardini, A. Estimation of spatial-temporal gait parameters in level walking based on a single accelerometer: Validation on normal subjects by standard gait analysis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2012, 108, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Lee, W. Comparison of accelerometer-based and treadmill-based analysis systems for measuring gait parameters in healthy adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, W.; Hof, A.L. Assessment of spatio-temporal gait parameters from trunk accelerations during human walking. Gait Posture 2003, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCamley, J.; Donati, M.; Grimpampi, E.; Mazzà, C. An enhanced estimate of initial contact and final contact instants of time using lower trunk inertial sensor data. Gait Posture 2012, 36, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobbs, R.J.; Perring, J. Gait metrics analysis utilizing single-point inertial measurement units: A systematic review. mHealth 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraglia, F.; Scarcella, L. Inertial sensors versus standard systems in gait analysis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.70 ± 14.69 |

| Height (cm) | 169.30 ± 7.74 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.83 ± 15.32 |

| Intra-Rater Reliability—Baiobit System (Rater A) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bland–Altman Analysis | ||||||||

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | 1st Measure Mean ± SD | 2nd Measure Mean ± SD | ICC | SEM | MDC | Bias | 95% CI | LOA |

| Stance phase [%GCT] | 60.31 ± 2.23 | 60.38 ± 3.13 | 0.63 | 0.49 | 1.13 | −0.06 | 0.84 to −0.96 | −4.70 to 4.58 |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | 37.31 ± 9.45 | 39.61 ± 3.13 | 0.63 | 1.28 | 2.99 | 0.07 | 0.97 to −0.83 | −4.56 to 4.70 |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | 39.93 ± 2.00 | 39.64 ± 3.19 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 1.46 | 0.29 | 1.28 to −0.69 | −4.79 to 5.38 |

| Stride length [m] | 1.53 ± 0.22 | 1.49 ± 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 to −0.02 | −0.28 to 0.37 |

| Step length [m] | 0.77 ± 0.11 | 0.75 ± 0.11 | 0.68 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 to −0.01 | −0.14 to 0.19 |

| Velocity [m/s] | 1.31 ± 0.20 | 1.32 ± 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 to −0.04 | −0.18 to 0.17 |

| Cadence [steps/min] | 117.39 ± 13.91 | 121.10 ± 11.57 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 1.35 | −3.72 | −0.88 to −6.56 | −18.36 to 10.92 |

| Intra-rater reliability—BTS system (Rater B) | ||||||||

| Bland–Altman Analysis | ||||||||

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | 1st Measure Mean ± SD | 2nd Measure Mean ± SD | ICC | SEM | MDC | Bias | 95% CI | LOA |

| Stance phase [%GCT] | 60.68 ± 1.73 | 60.68 ± 1.58 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.46 to −0.47 | −2.39 to 2.39 |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | 43.49 ± 22.92 | 39.34 ± 1.59 | 0.74 | 1.98 | 4.62 | −0.02 | 0.45 to −0.48 | −2.40 to 2.37 |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | 39.86 ± 1.81 | 39.63 ± 1.83 | 0.74 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.74 to −0.29 | −2.42 to 2.87 |

| Stride length [m] | 1.50 ± 0.18 | 1.53 ± 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.01 to −0.07 | −0.25 to 0.20 |

| Step length [m] | 0.75 ± 0.09 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.00 to −0.05 | −0.14 to 0.09 |

| Velocity [m/s] | 1.33 ± 0.20 | 1.34 ± 0.20 | 0.88 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 to −0.04 | −0.18 to 0.15 |

| Cadence [steps/min] | 120.96 ± 9.23 | 120.24 ± 12.66 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 1.39 | 0.72 | 3.01 to −1.58 | −11.12 to 12.54 |

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Level of Intra-Rater Reliability |

|---|---|

| Stance phase [%GCT] | Doubtful |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | Doubtful |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | Doubtful |

| Stride length [m] | Adequate |

| Step length [m] | Adequate |

| Velocity [m/s] | Excellent |

| Cadence [steps/min] | Adequate |

| Inter-Rater Reliability—Baiobit System | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bland–Altman Analysis | ||||||||

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Rater A Mean ± SD | Rater B Mean ± SD | ICC | SEM | MDC | Bias | 95% CI | LOA |

| Stance phase [%GCT] | 60.28 ± 2.46 | 60.7 ± 1.57 | 0.66 | 0.46 | 1.08 | −0.42 | 0.23 to −1.07 | −3.73 to 2.89 |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | 39.72 ± 2.47 | 39.3 ± 1.57 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 1.09 | 0.41 | 1.07 to −0.24 | −2.90 to 3.73 |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | 39.85 ± 2.35 | 39.73 ± 1.72 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.83 | 0.12 | 0.73 to −0.50 | −2.98 to 3.22 |

| Stride length [m] | 1.51 ± 0.20 | 1.51 ± 0.19 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.05 to −0.04 | −0.22 to 0.24 |

| Step length [m] | 0.76 ± 0.10 | 0.76 ± 0.09 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.03 to −0.02 | −0.11 to 0.12 |

| Velocity [m/s] | 1.32 ± 0.20 | 1.33 ± 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.02 to −0.05 | −0.21 to 0.18 |

| Cadence [steps/min] | 119.33 ± 12.46 | 120.7 ± 10.84 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.88 | −1.37 | 0.87 to −3.61 | −12.71 to 9.97 |

| Inter-rater reliability—BTS system | ||||||||

| Bland–Altman Analysis | ||||||||

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Rater A Mean ± SD | Rater B Mean ± SD | ICC | SEM | MDC | Bias | 95% CI | LOA |

| Stance phase [%GCT] | 61.90 ± 2.05 | 61.34 ± 2.23 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 1.17 to −0.05 | −2.52 to 3.65 |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | 38.10 ± 2.05 | 38.64 ± 2.24 | 0.72 | 0.19 | 0.45 | −0.55 | 0.06 to −1.15 | −3.61 to 2.52 |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | 38.13 ± 2.05 | 38.80 ± 2.21 | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.65 | −0.68 | −0.06 to −1.29 | −3.77 to 2.42 |

| Stride length [m] | 1.38 ± 0.12 | 1.39 ± 0.13 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.02 to −0.05 | −0.19 to 0.14 |

| Step length [m] | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 to −0.02 | −0.08 to 0.07 |

| Velocity [m/s] | 1.37 ± 0.17 | 1.39 ± 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.09 | −0.03 | 0.01 to −0.08 | −0.21 to 0.15 |

| Cadence [steps/min] | 119.31 ± 9.39 | 120.81 ± 8.89 | 0.78 | 0.28 | 0.65 | −1.50 | 0.83 to −3.83 | −13.25 to 10.25 |

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Level of Inter-Rater Reliability |

|---|---|

| Stance phase [%GCT] | Doubtful/Adequate |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | Doubtful/Adequate |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | Doubtful/Adequate |

| Stride length [m] | Adequate |

| Step length [m] | Adequate |

| Velocity [m/s] | Excellent |

| Cadence [steps/min] | Excellent |

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Baiobit System Mean ± SD | BTS System Mean ± SD | Two-Tailed Paired Test (p-Value) | Spearman Coefficient (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stance phase [%GCT] | 60.31 ± 3.17 | 61.76 ± 2.58 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | 39.68 ± 3.17 | 38.24 ± 2.58 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | 39.70 ± 3.24 | 38.26 ± 2.56 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Stride length [m] | 1.49 ± 0.22 | 1.38 ± 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.70 |

| Step length [m] | 0.75 ± 0.11 | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.73 |

| Velocity [m/s] | 1.32 ± 0.20 | 1.38 ± 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| Cadence [steps/min] | 121.24 ± 11.76 | 120.13 ± 10.13 | 0.44 | 0.88 |

| Passing-Bablok Regression Analysis | Bland–Altman Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | m | 95% CI m | q | 95% CI q | Bias | 95% CI Bias | LOA |

| Stance phase [%GCT] | 0.64 | 0.25 to 1.34 | 20.48 | −22.26 to 44.25 | −1.45 | −2.95 to 0.05 | −9.40 to 6.50 |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | 0.65 | 0.25 to 1.35 | 15.14 | −12.53 to 30.51 | 1.44 | −0.07 to 2.95 | −6.55 to 9.42 |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | 0.68 | 0.26 to 1.48 | 13.56 | −16.99 to 29.72 | 1.43 | −0.10 to 2.97 | −6.71 to 9.58 |

| Stride length [m] | 1.74 | 1.33 to 2.45 | −0.94 | −1.90 to −0.37 | 0.11 | 0.05 to 0.16 | −0.18 to 0.40 |

| Step length [m] | 1.84 | 1.40 to 2.62 | −0.54 | −1.06 to −0.23 | 0.06 | 0.03 to 0.08 | −0.08 to 0.20 |

| Velocity [m/s] | 1.15 | 0.95 to 1.40 | −0.26 | −0.60 to 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.09 to −0.02 | −0.24 to 0.13 |

| Cadence [steps/min] | 1.07 | 0.78 to 1.44 | −5.01 | −50.50 to 28.52 | 1.11 | −1.69 to 3.92 | −13.73 to 15.96 |

| Spatiotemporal Parameters | Level of Agreement | Type of Error |

|---|---|---|

| Stance phase [%GCT] | No Agreement | Constant and Proportional systematic errors |

| Swing phase [%GCT] | No Agreement | Constant and Proportional systematic errors |

| Single support phase [%GCT] | No Agreement | Constant and Proportional systematic errors |

| Stride length [m] | No Agreement | Constant and Proportional systematic errors |

| Step length [m] | No Agreement | Constant and Proportional systematic errors |

| Velocity [m/s] | Agreement | None |

| Cadence [steps/min] | Agreement | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lerín-Calvo, A.; Prisco, G.; Fernández-Maza, E.; Núñez-González, M.; Santiago-Lorrio, G.; Donisi, L.; Lerma-Lara, S. Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Single Lumbar-Mounted IMU System for Gait Analysis. Sensors 2025, 25, 7643. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247643

Lerín-Calvo A, Prisco G, Fernández-Maza E, Núñez-González M, Santiago-Lorrio G, Donisi L, Lerma-Lara S. Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Single Lumbar-Mounted IMU System for Gait Analysis. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7643. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247643

Chicago/Turabian StyleLerín-Calvo, Alfredo, Giuseppe Prisco, Elena Fernández-Maza, Marta Núñez-González, Gema Santiago-Lorrio, Leandro Donisi, and Sergio Lerma-Lara. 2025. "Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Single Lumbar-Mounted IMU System for Gait Analysis" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7643. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247643

APA StyleLerín-Calvo, A., Prisco, G., Fernández-Maza, E., Núñez-González, M., Santiago-Lorrio, G., Donisi, L., & Lerma-Lara, S. (2025). Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Single Lumbar-Mounted IMU System for Gait Analysis. Sensors, 25(24), 7643. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247643