Introducing a Development Method for Active Perception Sensor Simulations Using Continuous Verification and Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. State of the Art on Active Perception Sensor Simulation and Validation Methodology

1.2. Key Contributions and Structure

- An iterative, effect-, cause-, and function-based method for efficient development of traceable sensor simulations with continuous V&V.

- Method for deriving test cases from the simulation requirements and a taxonomy for structuring validation test cases.

- Approaches towards the validation of data acquired for the development and V&V process.

- Demonstration of an approach for the systematic, empirical derivation of acceptance criteria for validation test cases.

1.3. Definition of Terms

2. Proposed Continuous V&V Development Method for Sensor Simulations

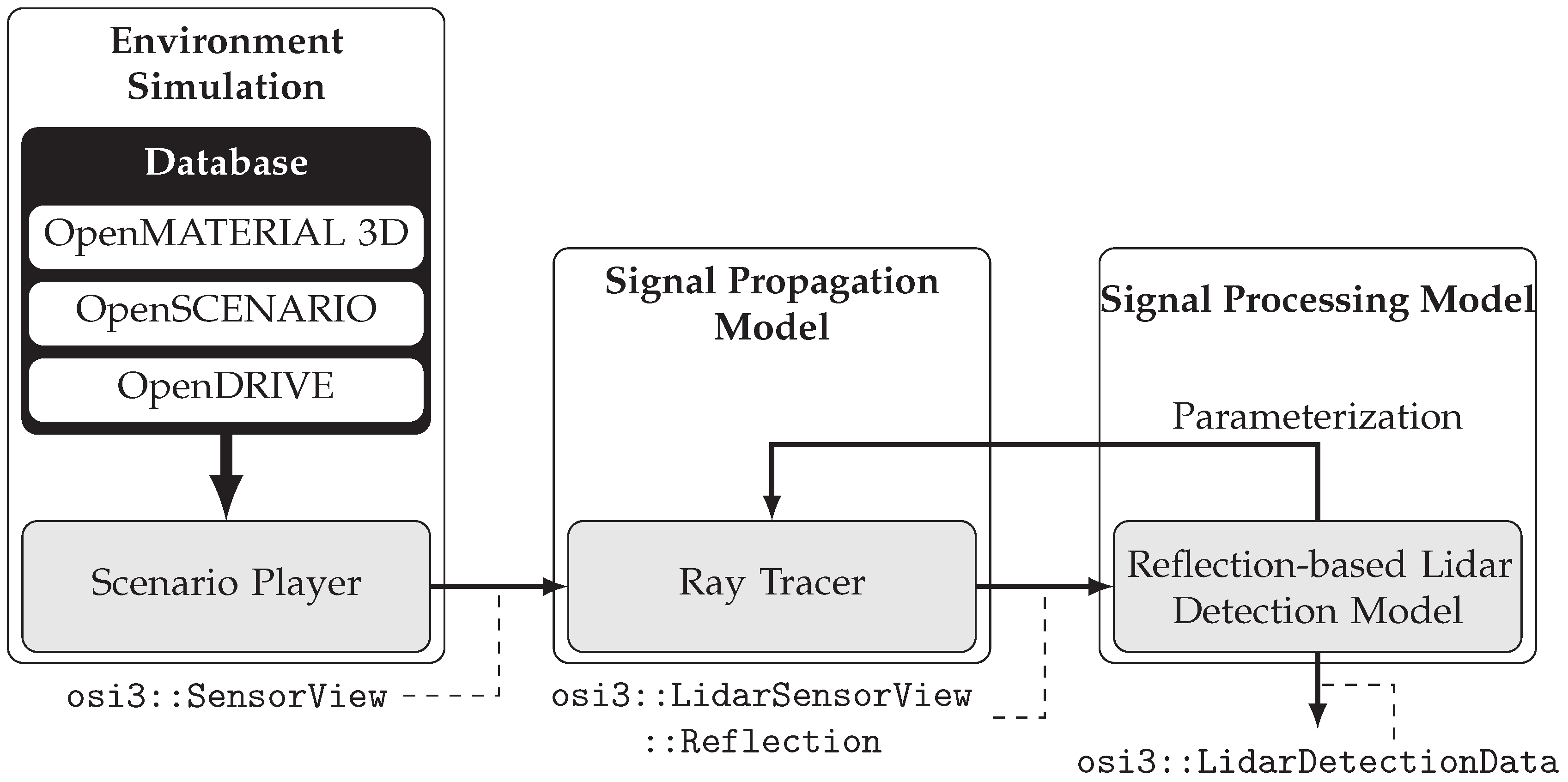

2.1. Sensor Simulation Architecture

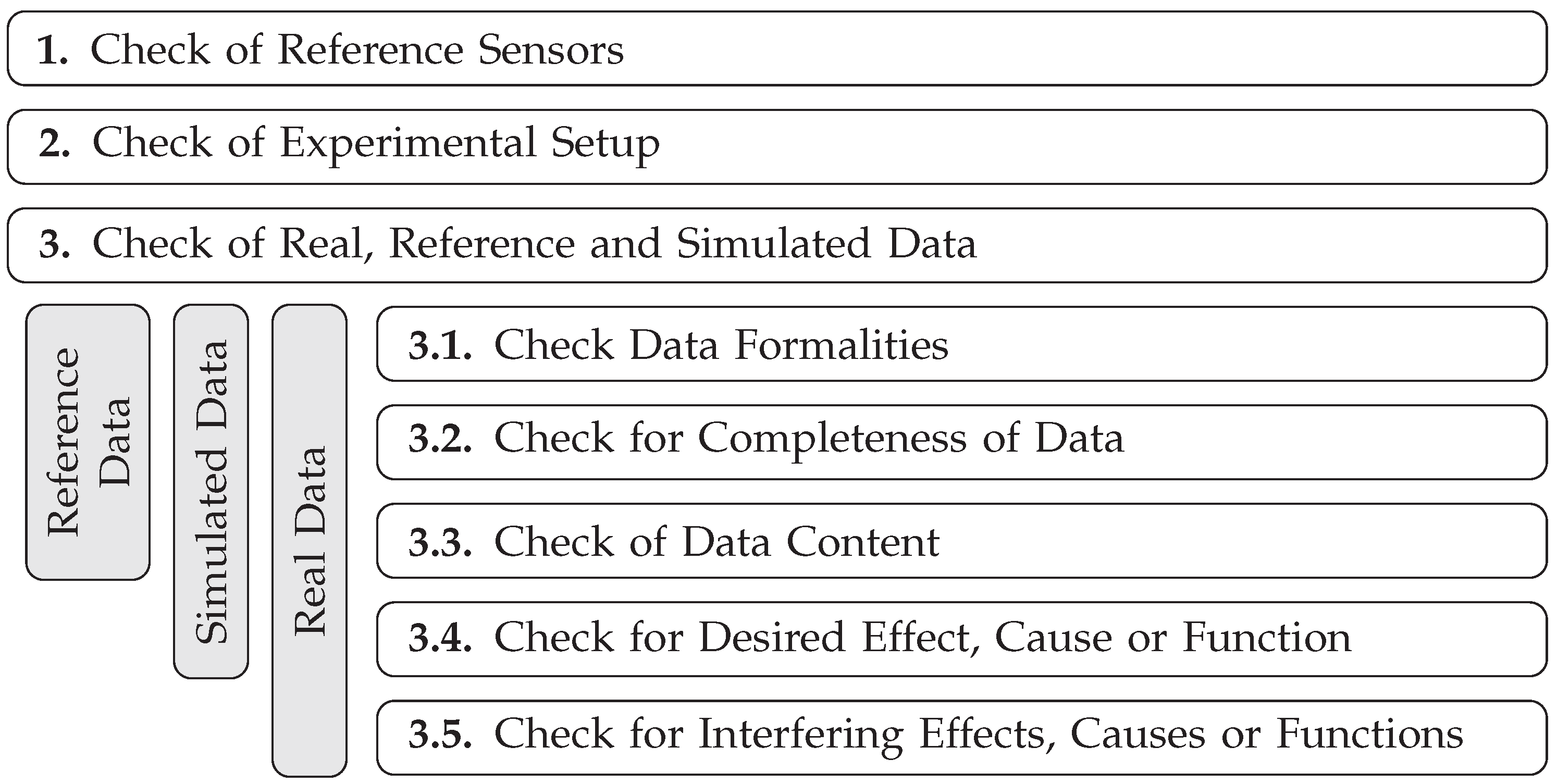

2.2. Preparatory Steps for Simulation Development and V&V

2.2.1. Definition of Requirements

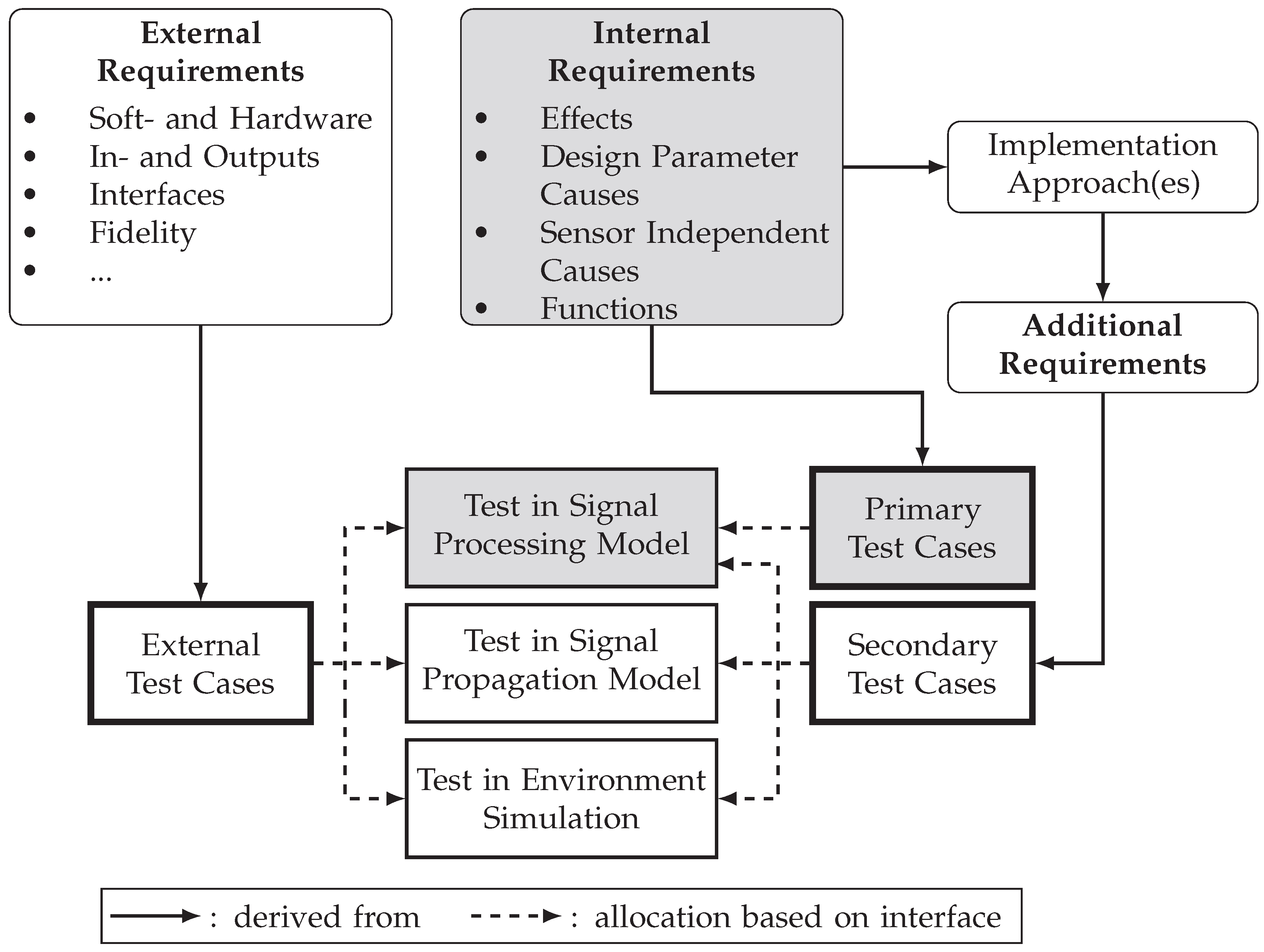

2.2.2. Derivation of Test Cases

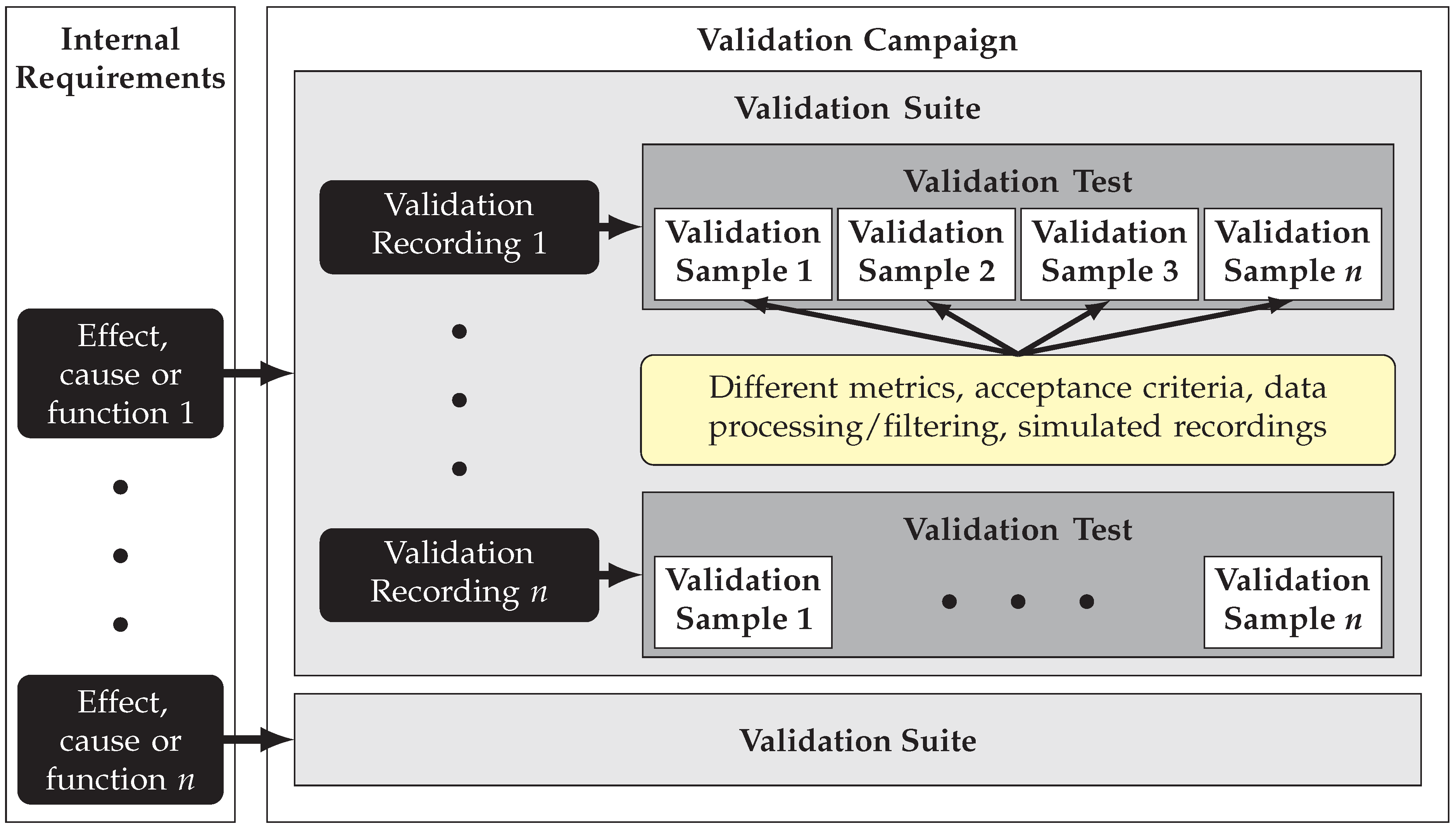

2.2.3. Taxonomy and Derivation of Acceptance Criteria for Primary Validation Test Cases

2.2.4. Data Acquisition for Development and Validation of the Simulation

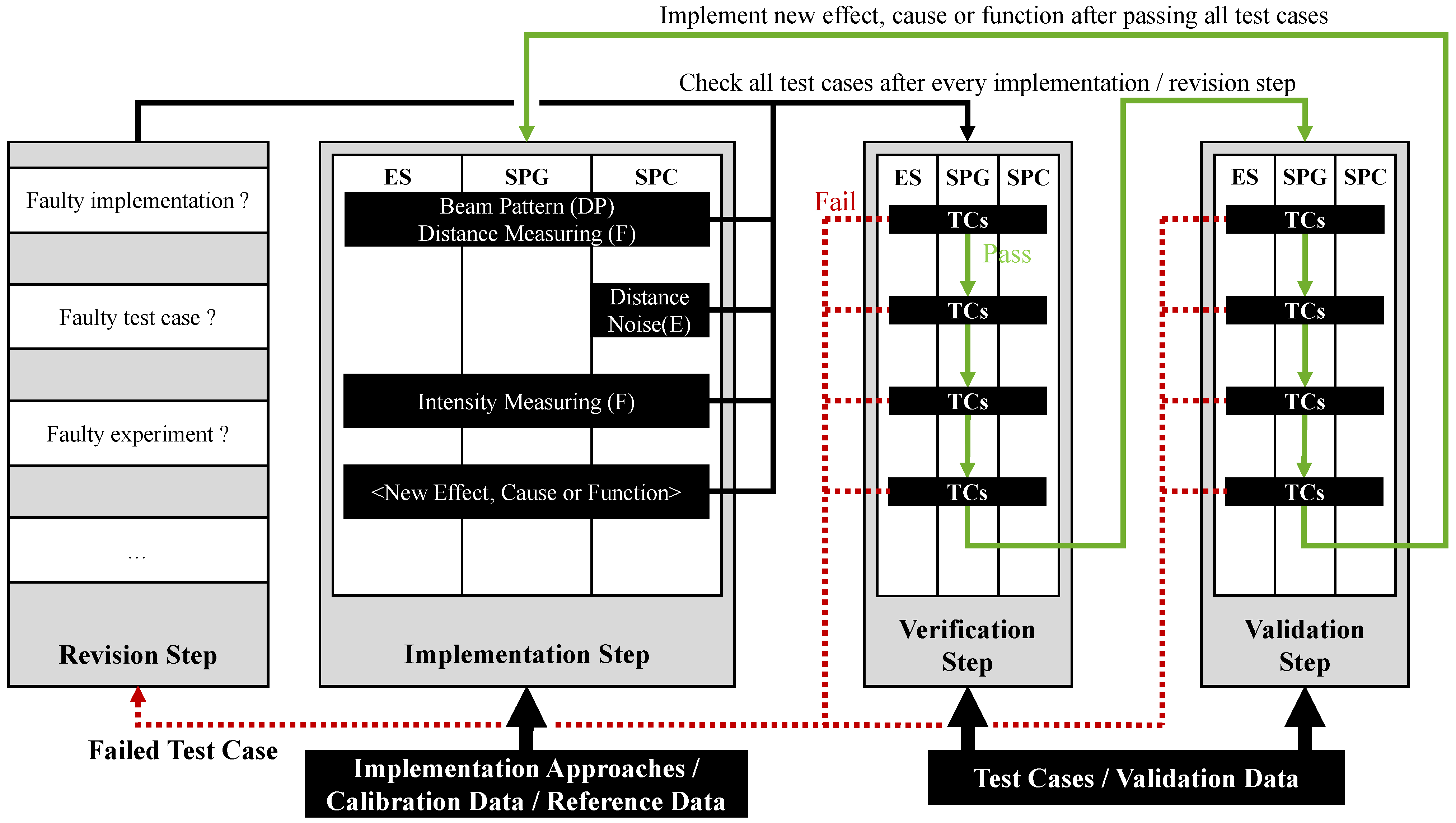

2.3. Development Method for Sensor Simulations

3. Exemplary Execution of the Development Method for a Lidar Sensor Simulation

3.1. Preparatory Steps for the Development of an Exemplary Lidar Sensor Simulation

3.1.1. Definition of Requirements for Lidar Sensor Simulation

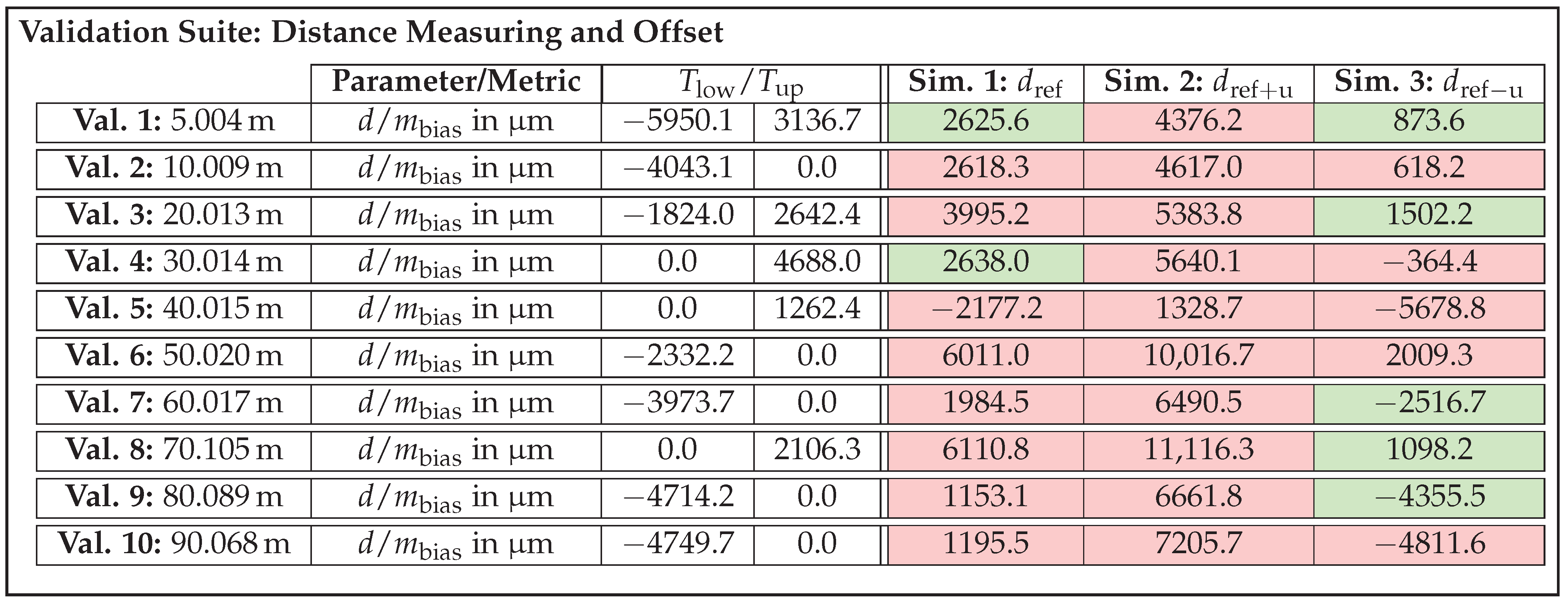

- Distance measuring and offset.

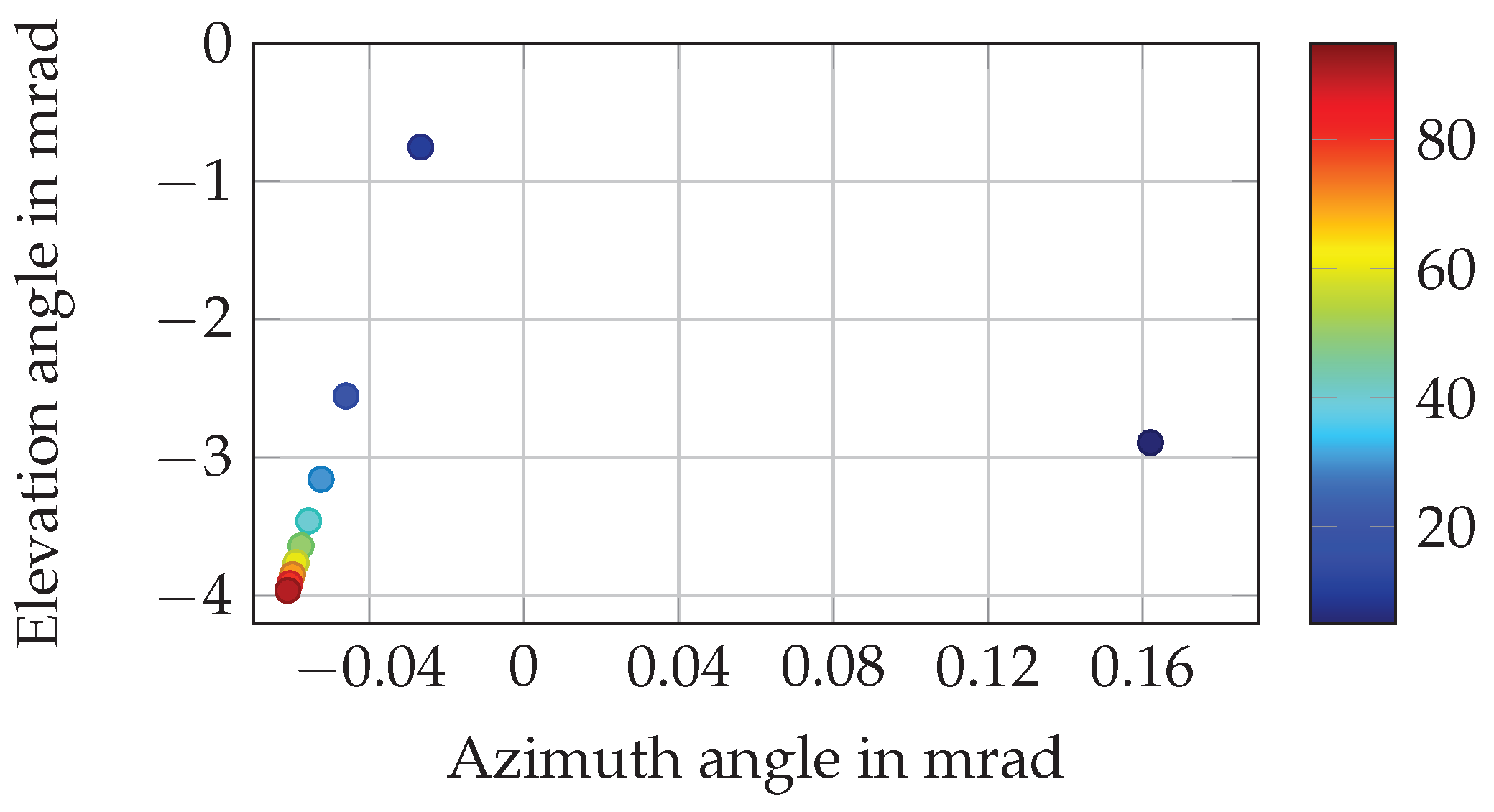

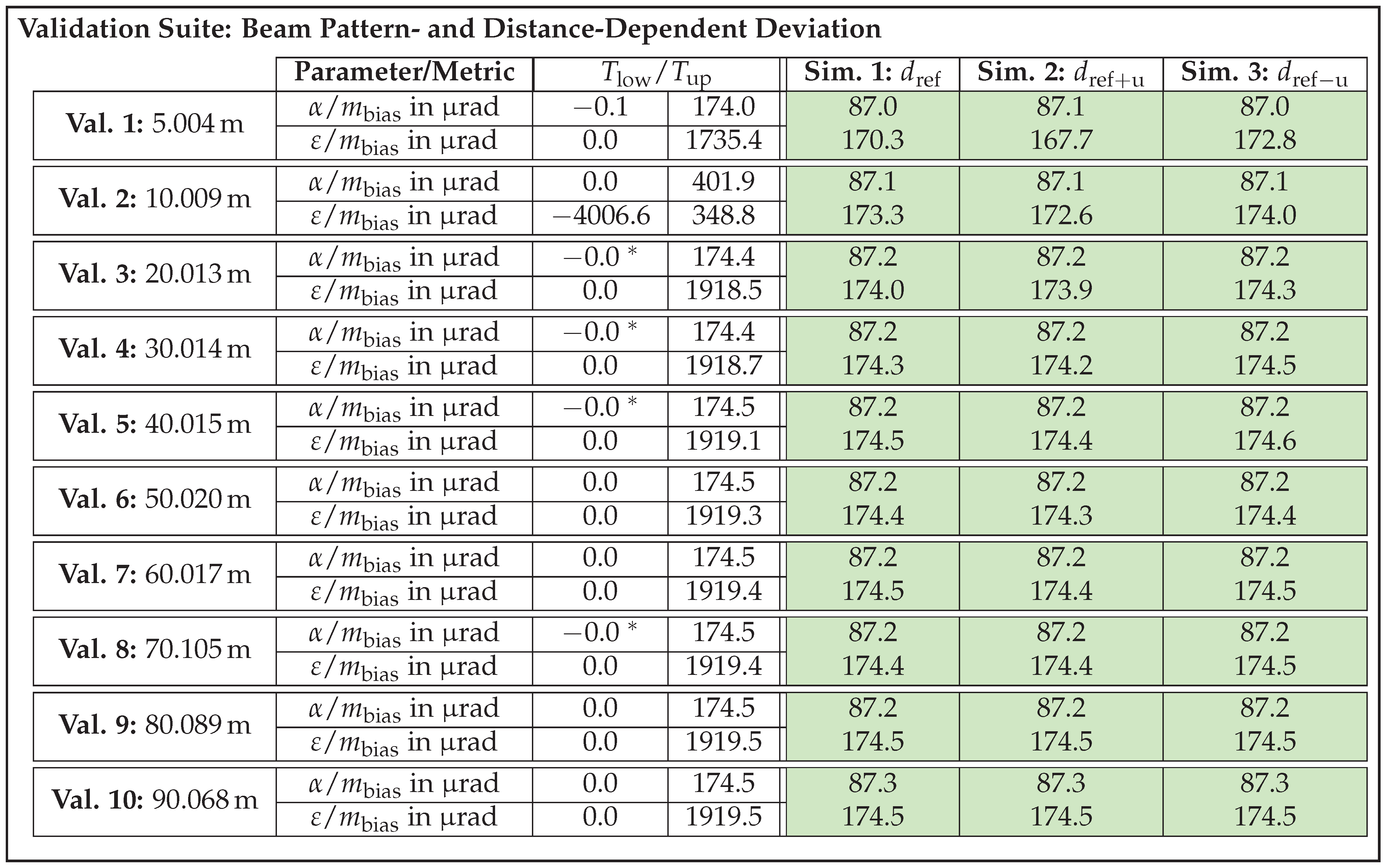

- Beam pattern and distance-dependent deviation.

- Distance noise.

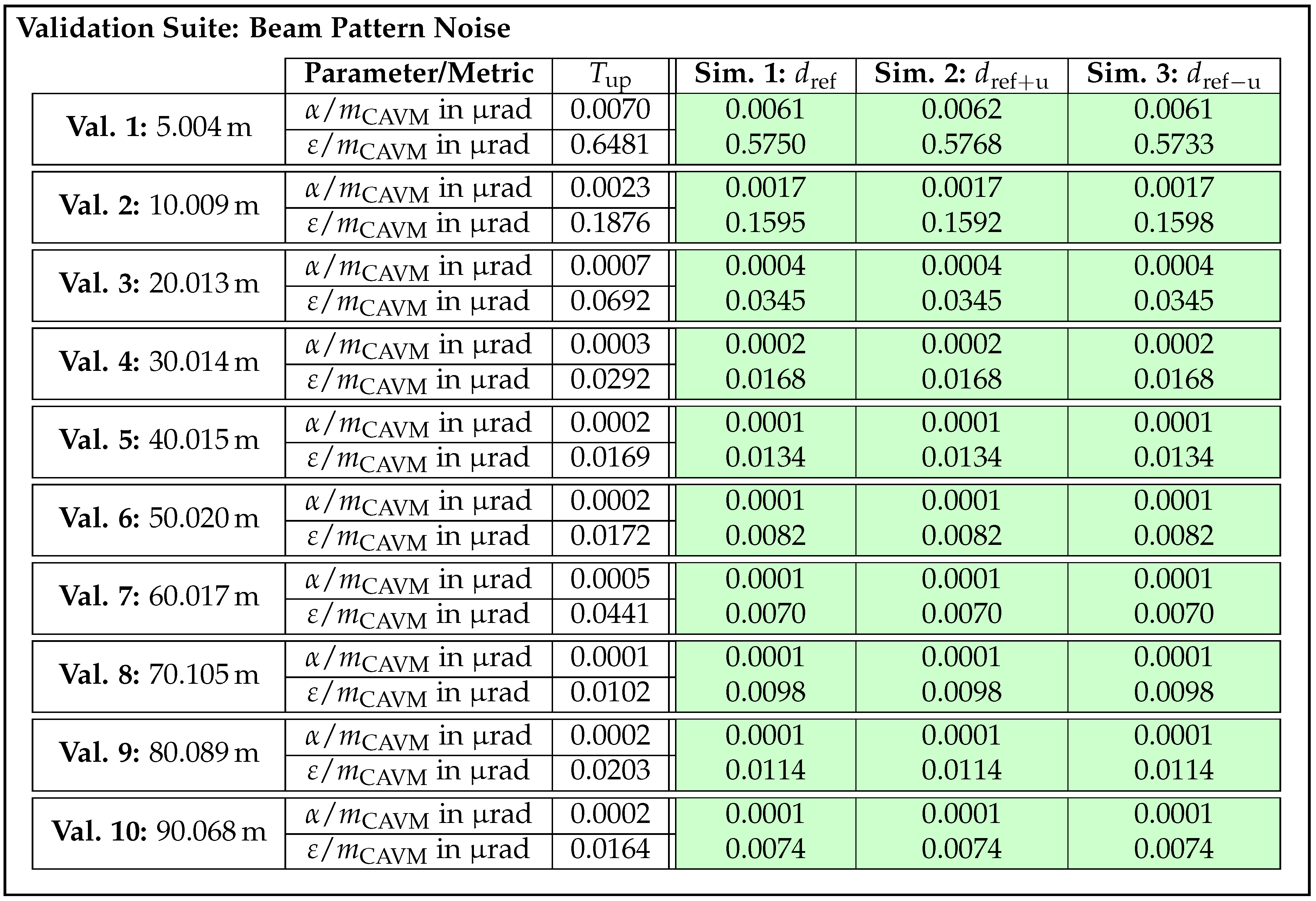

- Beam pattern noise.

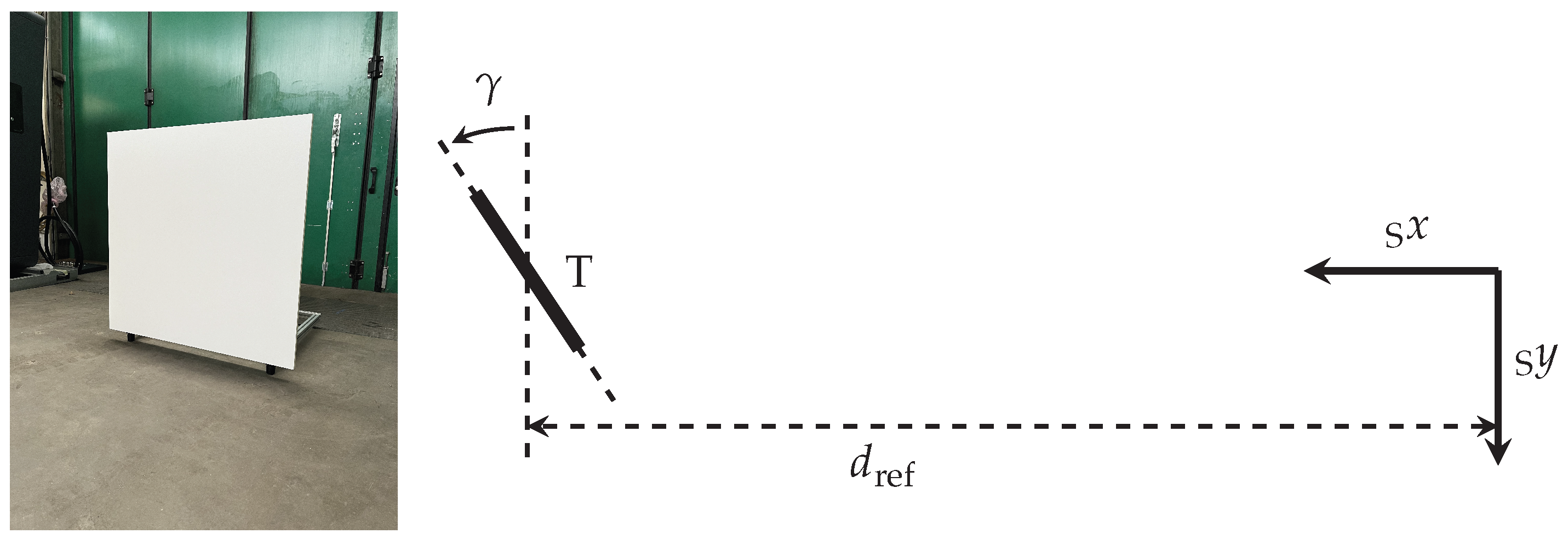

3.1.2. Data Acquisition

3.1.3. Exemplary Derivation of Validation Test Cases with Acceptance Criteria

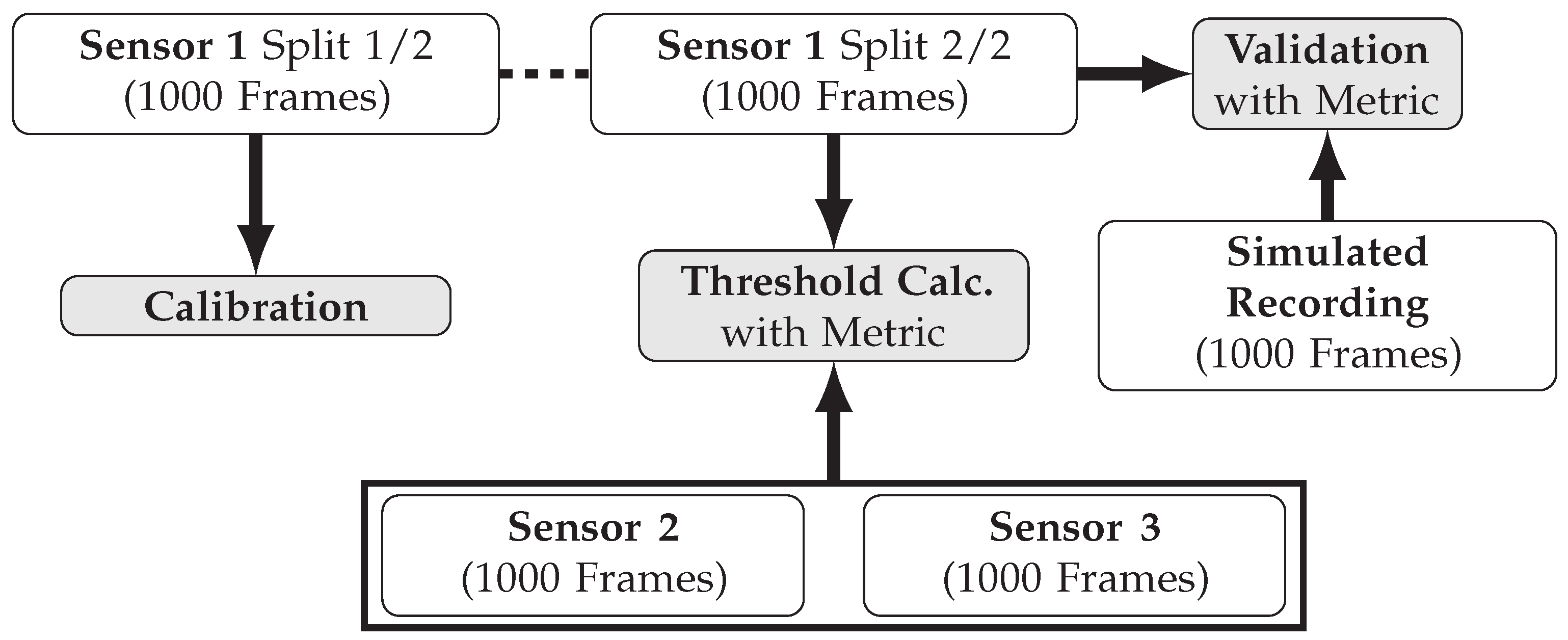

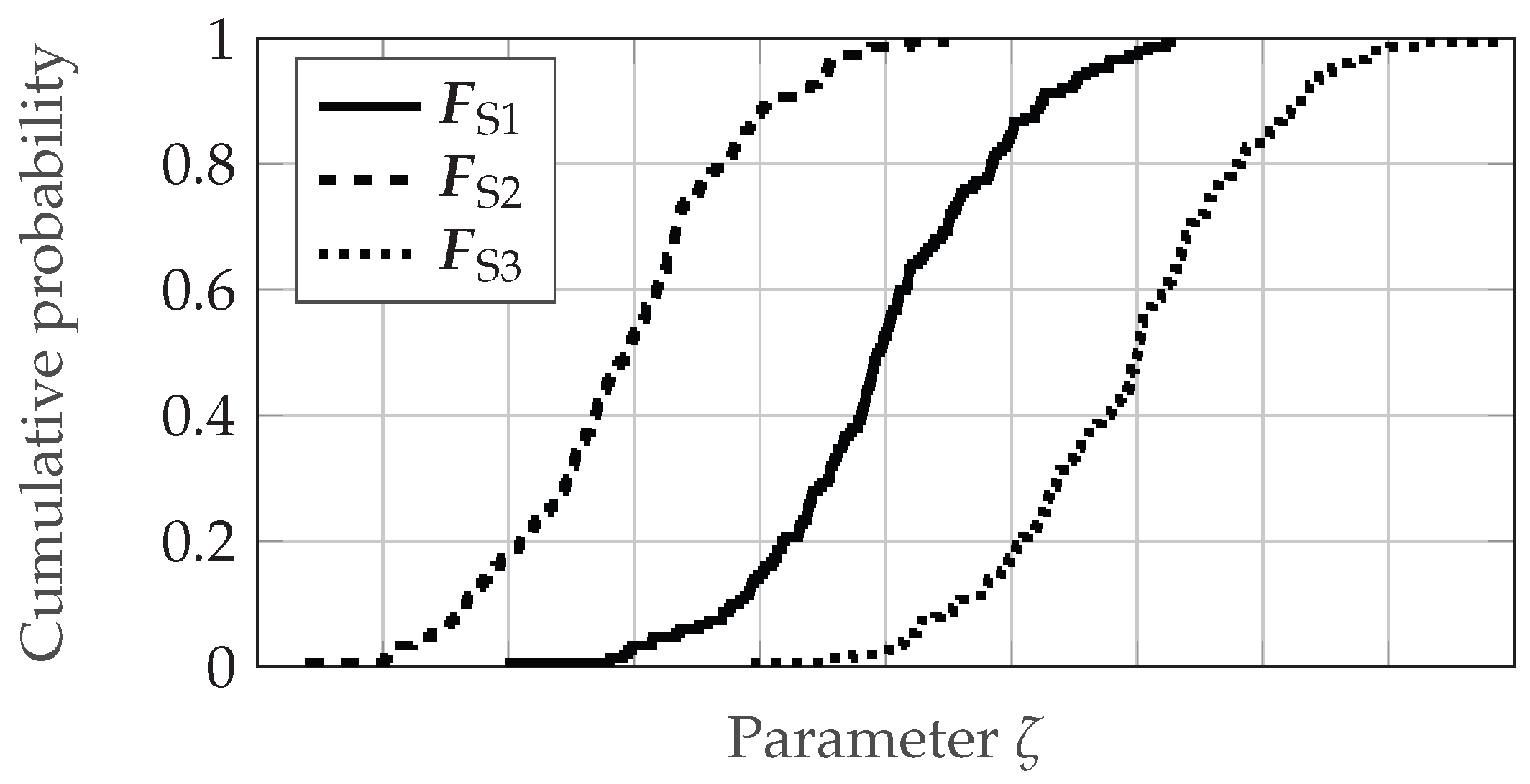

Derivation of Validation Samples

Validation Metric

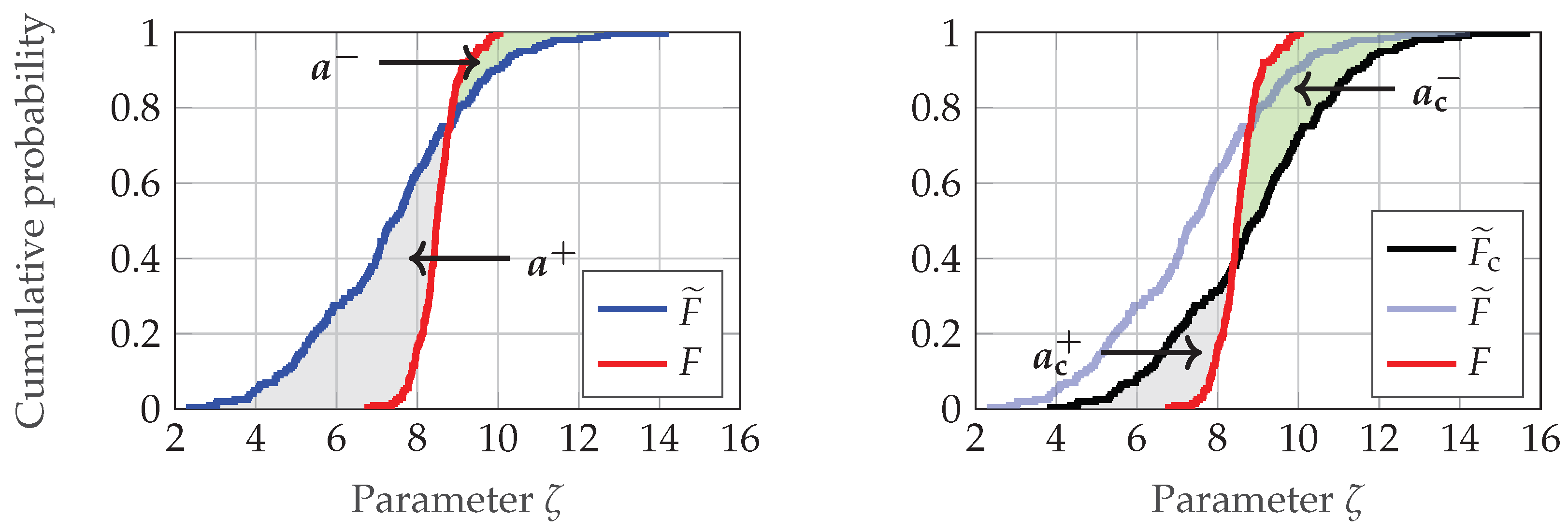

Empirical Derivation of Acceptance Thresholds

3.2. Realization and Validation of Lidar Sensor Simulation

3.2.1. First Iteration

3.2.2. Second Iteration

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Automated Driving |

| ADAS | Advanced Driver Assistance System |

| CAVM | Corrected Area Validation Metric |

| CEPRA | Cause, Effect, and Phenomenon Relevance Analysis |

| DVM | Double Validation Metric |

| EDF | Empirical Cumulative Distribution Function |

| ES | Environment Simulation |

| FMI | Functional Mock-up Interface |

| ID | Identification Number |

| ODD | Operational Design Domain |

| OSI | Open Simulation Interface |

| SMDL | Sensor Model Development Library |

| SPC | Signal Processing Model |

| SPG | Signal Propagation Model |

| SuT | System under Test |

| UNECE | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe |

| V&V | Verification and Validation |

References

- Wachenfeld, W.; Winner, H. The Release of Autonomous Vehicles. In Autonomous Driving: Technical, Legal and Social Aspects; Maurer, M., Gerdes, J., Lenz, B., Winner, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 425–449. ISBN 978-3-662-48847-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Hernandez, G.; Yeong, D.J.; Barry, J.; Walsh, J. Autonomous Driving Architectures, Perception and Data Fusion: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 3–5 September 2020; pp. 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. UN Regulation No. 171-Uniform Provisions Concerning the Approval of Vehicles with Regard to Driver Control Assistance Systems. 2024. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/R171e.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. New Assessment/Test Method for Automated Driving (NATM) Guidelines for Validating Automated Driving System (ADS). 2023. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/ECE-TRANS-WP.29-2023-44-r.1e%20.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Guidelines and Recommendations for Automated Driving System Safety Requirements, Assessments and Test Methods to Inform Regulatory Development. 2024. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/ECE-TRANS-WP.29-2024-39e.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1426 of 5 August 2022 Laying Down Rules for the Application of Regulation (EU) 2019/2144 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Uniform Procedures and Technical Specifications for the Type-Approval of the Automated Driving System (ADS) of Fully Automated Vehicles. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R1426 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Schlager, B.; Muckenhuber, S.; Schmidt, S.; Holzer, H.; Rott, R.; Maier, F.M.; Saad, K.; Kirchengast, M.; Stettinger, G.; Watzenig, D.; et al. State-of-the-Art Sensor Models for Virtual Testing of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems/Autonomous Driving Functions. SAE Int. J. Connect. Autom. Veh. 2020, 3, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, P. Metrics for Specification, Validation, and Uncertainty Prediction for Credibility in Simulation of Active Perception Sensor Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, P.; Wendler, J.T.; Holder, M.F.; Linnhoff, C.; Berghöfer, M.; Winner, H.; Maurer, M. Towards a Generally Accepted Validation Methodology for Sensor Models—Challenges, Metrics, and First Results. In Proceedings of the 12th Graz Symposium Virtual Vehicle, Graz, Austria, 7–8 May 2019; Available online: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/id/eprint/8653 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Haider, A.; Pigniczki, M.; Köhler, M.H.; Fink, M.; Schardt, M.; Cichy, Y.; Zeh, T.; Haas, L.; Poguntke, T.; Jakobi, M.; et al. Development of High-Fidelity Automotive LiDAR Sensor Model with Standardized Interfaces. Sensors 2022, 22, 7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Ros, G.; Codevilla, F.; Lopez, A.; Koltun, V. CARLA: An Open Urban Driving Simulator. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on Robot Learning, Mountain View, CA, USA, 13–15 November 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, N.; Höfer, A.; Herrmann, M.; Donn, C. Real-time Simulation of Physical Multi-sensor Setups. ATZelectron. Worldw. 2020, 15, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vector Informatik GmbH. DYNA4 Sensor Simulation: Environment Perception for ADAS and AD. Available online: https://www.vector.com/int/en/products/products-a-z/software/dyna4/sensor-simulation (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- dSPACE GmbH. AURELION Sensor-Realistic Simulation for ADAS/AD in Real Time. Available online: https://www.dspace.com/en/pub/home/products/sw/experimentandvisualization/aurelion_sensor-realistic_sim.cfm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Hexagon AB. Virtual Test Drive. Available online: https://hexagon.com/products/virtual-test-drive?utm_easyredir=vires.mscsoftware.com (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- ESI Group. PROSIVIC. Available online: https://www.esi-group.com/cn/products/prosivic (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Kedzia, J.C.; de Souza, P.; Gruyer, D. Advanced RADAR sensors modeling for driving assistance systems testing. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Davos, Switzerland, 10–15 April 2016; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansys, Inc. Ansys AVxcelerate Sensors. Available online: https://www.ansys.com/products/av-simulation/ansys-avxcelerate-sensors (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- AVSimulation. SCANeR. Available online: https://www.avsimulation.com/en/scaner/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- AVL List GmbH. AVL Scenario Simulator. Available online: https://www.avl.com/en-de/simulation-solutions/software-offering/simulation-tools-a-z/avl-scenario-simulator (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Siemens Digital Industries Software. Simcenter Prescan Software. Available online: https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/simcenter/autonomous-vehicle-solutions/prescan/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Schmidt-Kopilaš, S. Sensormodellspezifkation für die Entwicklung Automatisierter Fahrfunktionen. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, A. A Methodology for Validation of a Radar Simulation for Virtual Testing of Autonomous Driving. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Magosi, Z.F.; Li, H.; Rosenberger, P.; Wan, L.; Eichberger, A. A Survey on Modelling of Automotive Radar Sensors for Virtual Test and Validation of Automated Driving. Sensors 2022, 22, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, T.; Schaermann, A.; Geiger, M.; Weiler, K.; Hirsenkorn, N.; Rauch, A.; Schneider, S.A.; Biebl, E. Generation and validation of virtual point cloud data for automated driving systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Yokohama, Japan, 16–19 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deng, W.; Li, X.; liu, Z.; Jiang, L. LiDAR Sensor Modeling for ADAS Applications under a Virtual Driving Environment. In Proceedings of the SAE-TONGJI 2016 Driving Technology of Intelligent Vehicle Symposium, Gothenburg, Sweden, 19–22 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, B.; Deng, W.; Sun, B. Method and Applications of Lidar Modeling for Virtual Testing of Intelligent Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 2990–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, C.; Kala, R.; Carrrillo, A.; Liu, L.Y. Sensor Modeling for the Virtual Autonomous Navigation Environment. In Proceedings of the IEEE SENSORS 2009 Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 25–28 October 2009; pp. 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwandtner, M.; Kwitt, R.; Uhl, A.; Pree, W. BlenSor: Blender Sensor Simulation Toolbox. In Advances in Visual Computing; Bebis, G., Boyle, R., Parvin, B., Koracin, D., Ushizima, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhou, D.; Yan, F.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, R. Augmented LiDAR Simulator for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, S.; Höfle, B. Helios: A multi-purpose LIDAR simulation framework for research, planning and training of laser scanning operations with airborne, ground-based mobile and stationary platforms. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, III-3, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsenkorn, N.; Subkowski, P.; Hanke, T.; Schaermann, A.; Rauch, A.; Rasshofer, R.; Biebl, E. A ray launching approach for modeling an FMCW radar system. In Proceedings of the 2017 18th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Prague, Czech Republic, 28–30 June 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, M.; Linnhoff, C.; Rosenberger, P.; Winner, H. The Fourier Tracing Approach for Modeling Automotive Radar Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2019 20th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Ulm, Germany, 26–28 June 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernsteiner, S.; Magosi, Z.; Lindvai-Soos, D.; Eichberger, A. Radar Sensor Model for the Virtual Development Process. ATZ Elektron Worldw. 2015, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P. Modeling Active Perception Sensors for Real-Time Virtual Validation of Automated Driving Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, K.; Becker, D.; Wiesbeck, W. Extraction of Virtual Scattering Centers of Vehicles by Ray-Tracing Simulations. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2008, 56, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.A.; Holder, M.; Winner, H.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Deep stochastic radar models. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2017; pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, T.; Hirsenkorn, N.; Dehlink, B.; Rauch, A.; Rasshofer, R.; Biebl, E. Generic architecture for simulation of ADAS sensors. In Proceedings of the 2015 16th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Dresden, Germany, 24–26 June 2015; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, P.; Holder, M.; Huch, S.; Winner, H.; Fleck, T.; Zofka, M.R.; Zöllner, J.M.; D’hondt, T.; Wassermann, B. Benchmarking and Functional Decomposition of Automotive Lidar Sensor Models. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Paris, France, 9–12 June 2019; pp. 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, P.; Holder, M.F.; Cianciaruso, N.; Aust, P.; Tamm-Morschel, J.F.; Linnhoff, C.; Winner, H. Sequential lidar sensor system simulation: A modular approach for simulation-based safety validation of automated driving. Automot. Engine Technol. 2020, 5, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnhoff, C.; Rosenberger, P.; Holder, M.F.; Cianciaruso, N.; Winner, H. Highly Parameterizable and Generic Perception Sensor Model Architecture. In Automatisiertes Fahren 2020; Bertram, T., Ed.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Schlager, B.; Muckenhuber, S.; Stark, R. Configurable Sensor Model Architecture for the Development of Automated Driving Systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanke, T.; Hirsenkorn, N.; van-Driesten, C.; Garcia-Ramos, P.; Schiementz, M.; Schneider, S.; Biebl, E. Open Simulation Interface: A Generic Interface for the Environment Perception of Automated Driving Functions in Virtual Scenarios. 2017. Available online: https://www.ee.cit.tum.de/hot/forschung/automotive-veroeffentlichungen/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Open Simulation Interface. Available online: https://github.com/OpenSimulationInterface/open-simulation-interface (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Modelica Association. Functional Mock-Up Interface (FMI). Available online: https://fmi-standard.org/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ASAM e.V. ASAM OpenMATERIAL 3D. Available online: https://github.com/asam-ev/OpenMATERIAL-3D (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ASAM e.V. ASAM OpenSCENARIO XML. Available online: https://publications.pages.asam.net/standards/ASAM_OpenSCENARIO/ASAM_OpenSCENARIO_XML/latest/index.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ASAM e.V. ASAM OpenDRIVE. Available online: https://publications.pages.asam.net/standards/ASAM_OpenDRIVE/ASAM_OpenDRIVE_Specification/latest/specification/index.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Bender, P.; Ziegler, J.; Stiller, C. Lanelets: Efficient map representation for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Dearborn, MI, USA, 8–11 June 2014; pp. 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggenhans, F.; Pauls, J.H.; Janosovits, J.; Orf, S.; Naumann, M.; Kuhnt, F.; Mayr, M. Lanelet2: A high-definition map framework for the future of automated driving. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 1672–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, M.; Koschi, M.; Manzinger, S. CommonRoad: Composable benchmarks for motion planning on roads. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2017; pp. 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremont, D.J.; Kim, E.; Dreossi, T.; Ghosh, S.; Yue, X.; Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A.L.; Seshia, S.A. Scenic: A language for scenario specification and data generation. Mach. Learn. 2023, 112, 3805–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.A.; Behrisch, M.; Bieker-Walz, L.; Erdmann, J.; Flötteröd, Y.P.; Hilbrich, R.; Lücken, L.; Rummel, J.; Wagner, P.; Wiessner, E. Microscopic Traffic Simulation using SUMO. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 2575–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, M.F.; Rosenberger, P.; Bert, F.; Winner, H. Data-driven Derivation of Requirements for a Lidar Sensor Model. In Proceedings of the 11th Graz Symposium Virtual Vehicle, Graz, Austria, 15–16 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsenkorn, N. Modellbildung und Simulation der Fahrzeugumfeldsensorik. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2018. Available online: https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/?id=1420990 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Linnhoff, C.; Rosenberger, P.; Schmidt, S.; Elster, L.; Stark, R.; Winner, H. Towards Serious Perception Sensor Simulation for Safety Validation of Automated Driving—A Collaborative Method to Specify Sensor Models. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 2688–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, L. Enhancing Radar Model Validation Methodology for Virtual Validation of Automated Driving Functions. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaermann, A. Systematische Bedatung und Bewertung Umfelderfassender Sensormodelle. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2020. Available online: https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1518611/document.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Sargent, R.G. Verification and validation of simulation models. J. Simul. 2013, 7, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberkampf, W.L.; Trucano, T.G. Verification and validation benchmarks. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2008, 238, 716–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, E.; Dirndorfer, T.J.; Knoll, A.; von Neumann-Cosel, K.; Ganslmeier, T.; Kern, A.; Fischer, M.O. Analysis and Validation of Perception Sensor Models in an Integrated Vehicle and Environment Simulation. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Technical Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles, Washington, DC, USA, 13–16 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, A.; Bauer, M.P.; Resch, M. A Multi-Layered Approach for Measuring the Simulation-to-Reality Gap of Radar Perception for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 4008–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, M.F. Synthetic Generation of Radar Sensor Data for Virtual Validation of Autonomous Driving. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, T. Simulation of Automotive Radar Point Clouds in Standardized Frameworks. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Magosi, Z.F.; Wellershaus, C.; Tihanyi, V.R.; Luley, P.; Eichberger, A. Evaluation Methodology for Physical Radar Perception Sensor Models Based on On-Road Measurements for the Testing and Validation of Automated Driving. Energies 2022, 15, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedmaier, S.; Danquah, B.; Schick, B.; Diermeyer, F. Unified Framework and Survey for Model Verification, Validation and Uncertainty Quantification. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2655–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruyer, D.; Régnier, R.; Mouchard, G.; Durand, G.; Chaves, C.; Prabakaran, S.; Quintero, K.; Bohn, C.; Andriantavison, K.; Ieng, S.S.; et al. [Deliverable 2.7] Methodology, Procedures and Protocols for Evaluation of Applications and Virtual Test Facilities. Available online: https://prissma.univ-gustave-eiffel.fr/fileadmin/contributeurs/PRISSMA/partners/Livrables/PRISSMA_deliverable_2_7_epure.pdf#%5B%7B%22num%22%3A2212%2C%22gen%22%3A0%7D%2C%7B%22name%22%3A%22XYZ%22%7D%2C83.955%2C486.904%2Cnull%5D (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Fonseca i Casas, P. A Continuous Process for Validation, Verification, and Accreditation of Simulation Models. Mathematics 2023, 11, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehof, M. Objektive Qualitätsbewertung von Fahrdynamiksimulationen Durch Statistische Validierung. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2018. Available online: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/7457/ (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Ahmann, M.; Le, V.T.; Eichenseer, F.; Steimann, F.; Benedikt, M. Towards Continuous Simulation Credibility Assessment. In Proceedings of the Asian Modelica Conference 2022, Tokyo, Japan, 24–25 November 2022; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinkel, H.-M.; Steinkirchner, K. Credible Simulation Process Framework. 2022. Available online: https://gitlab.setlevel.de/open/processes_and_traceability/credible_simulation_process_framework (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Haider, A.; Cho, Y.; Pigniczki, M.; Köhler, M.H.; Haas, L.; Kastner, L.; Fink, M.; Schardt, M.; Cichy, Y.; Koyama, S.; et al. Performance Evaluation of MEMS-Based Automotive LiDAR Sensor and Its Simulation Model as per ASTM E3125-17 Standard. Sensors 2023, 23, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walenta, K.; Genser, S.; Solmaz, S. Bayesian Gaussian Mixture Models for Enhanced Radar Sensor Modeling: A Data-Driven Approach towards Sensor Simulation for ADAS/AD Development. Sensors 2024, 24, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DIN SAE SPEC 91471:2023-05; Assessment Methodology for Automotive LiDAR Sensors. DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2023.

- ISO 23150:2023; Road Vehicles—Data Communication Between Sensors and Data Fusion Unit for Automated Driving Functions—Logical Interface. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Hofrichter, K.; Linnhoff, C.; Elster, L.; Peters, S. FMCW Lidar Simulation with Ray Tracing and Standardized Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2024 Stuttgart International Symposium, Stuttgart, Germany, 2–3 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofrichter, K. Development of an FMCW Lidar Signal Processing Model. Master’s Thesis, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persival GmbH. Sensor Model Development Library. Available online: https://www.persival.de/smdl (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- ISO/SAE PAS 22736:2021; Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. ISO/SAE International: Geneva, Switzerland/Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021.

- Ngo, A.; Bauer, M.P.; Resch, M. A Sensitivity Analysis Approach for Evaluating a Radar Simulation for Virtual Testing of Autonomous Driving Functions. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th Asia-Pacific Conference on Intelligent Robot Systems (ACIRS), Singapore, 17–19 July 2020; pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC/IEEE 24765:2017; Systems and Software Engineering—Vocabulary. ISO/IEC/IEEE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Holder, M.; Elster, L.; Winner, H. Digitalize the Twin: A Method for Calibration of Reference Data for Transfer Real-World Test Drives into Simulation. Energies 2022, 15, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouster Inc. Firmware User Manual. Available online: https://data.ouster.io/downloads/software-user-manual/firmware-user-manual-v2.5.3.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Menditto, A.; Patriarca, M.; Magnusson, B. Understanding the meaning of accuracy, trueness and precision. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2007, 12, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Bosch Power Tools GmbH. User Manual Bosch GLM 120 C Professional. Available online: https://www.bosch-professional.com/binary/manualsmedia/o293625v21_160992A4F4_201810.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Kirchengast, M.; Watzenig, D. A Depth-Buffer-Based Lidar Model With Surface Normal Estimation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 9375–9386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elster, L.; Rosenberger, P.; Holder, M.F.; Mori, K.; Staab, J.; Peters, S. Introducing the double validation metric for radar sensor models. Automot. Engine Technol. 2024, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyles, I.T.; Roy, C.J. Evaluation of Model Validation Techniques in the Presence of Aleatory and Epistemic Input Uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 17th AIAA Non-Deterministic Approaches Conference, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 5–9 January 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferson, S.; Oberkampf, W.L.; Ginzburg, L. Model validation and predictive capability for the thermal challenge problem. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2008, 197, 2408–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persival GmbH. Avelon. Available online: https://www.persival.de/avelon (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Ouster Inc. Ouster OS1 Datasheet. Available online: https://data.ouster.io/downloads/datasheets/datasheet-revc-v2p4-os1.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Groll, L.; Kapp, A. Effect of Fast Motion on Range Images Acquired by Lidar Scanners for Automotive Applications. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2007, 55, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A Survey of Deep Learning Techniques for Autonomous Driving. J. Field Robotics 2020, 37, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Runger, G.C. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in m | 5.004 | 10.009 | 20.013 | 30.014 | 40.015 | 50.020 | 60.017 | 70.105 | 80.089 | 90.068 |

| u in mm | ±1.7 | ±2.0 | ±2.5 | ±3.0 | ±3.5 | ±4.0 | ±4.5 | ±5.0 | ±5.5 | ±6.0 |

| Effect/Cause/Function | Parameter | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Beam pattern- and distance-dependent deviation | ||

| Distance measuring and offset | d | |

| Distance noise | d | |

| Beam pattern noise | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hofrichter, K.; Elster, L.; Linnhoff, C.; Ruppert, T.; Peters, S. Introducing a Development Method for Active Perception Sensor Simulations Using Continuous Verification and Validation. Sensors 2025, 25, 7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247642

Hofrichter K, Elster L, Linnhoff C, Ruppert T, Peters S. Introducing a Development Method for Active Perception Sensor Simulations Using Continuous Verification and Validation. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247642

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofrichter, Kristof, Lukas Elster, Clemens Linnhoff, Timm Ruppert, and Steven Peters. 2025. "Introducing a Development Method for Active Perception Sensor Simulations Using Continuous Verification and Validation" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247642

APA StyleHofrichter, K., Elster, L., Linnhoff, C., Ruppert, T., & Peters, S. (2025). Introducing a Development Method for Active Perception Sensor Simulations Using Continuous Verification and Validation. Sensors, 25(24), 7642. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247642