Laser-Induced Graphene on Polyimide: Material Characterization Toward Strain-Sensing Applications

Highlights

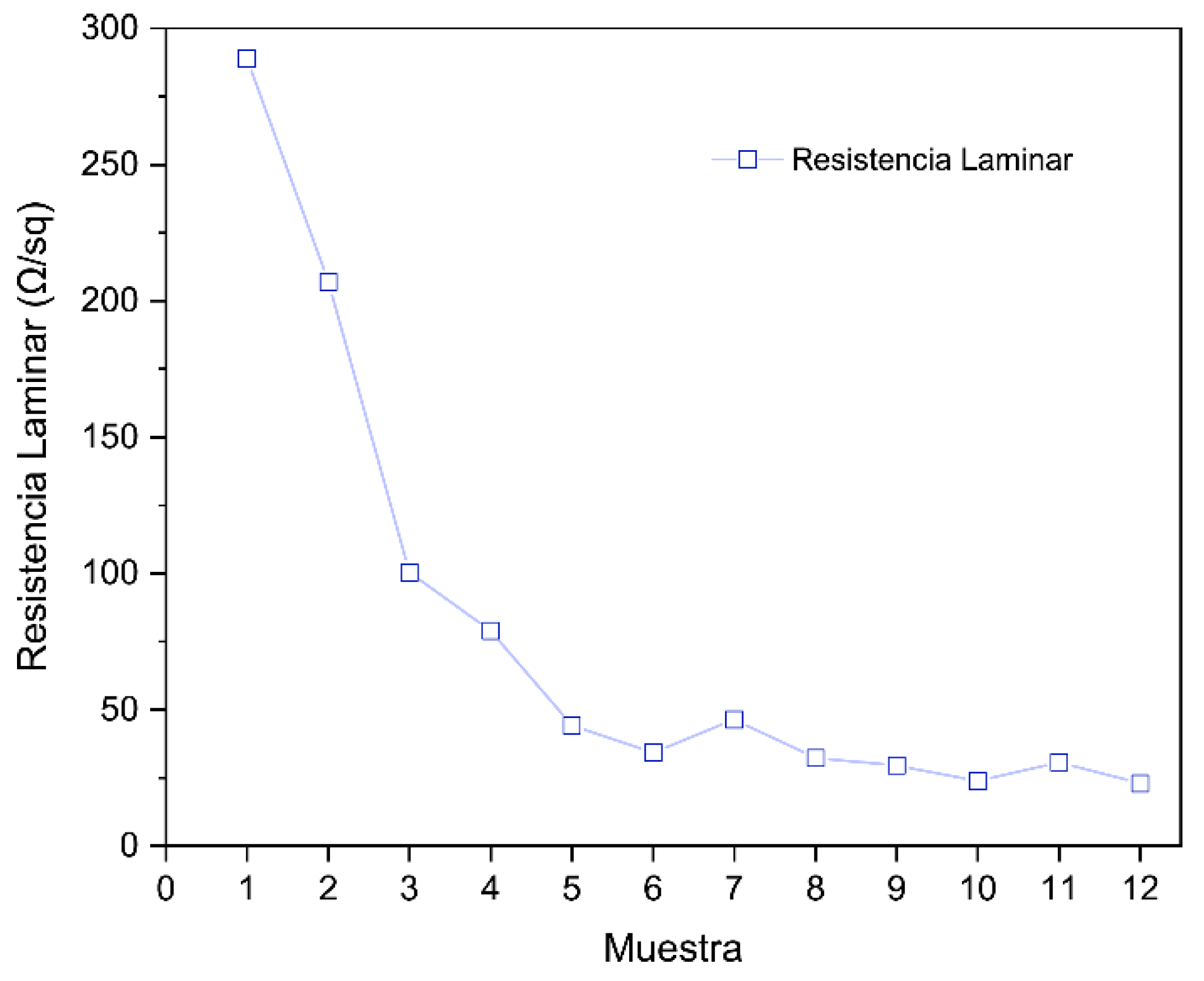

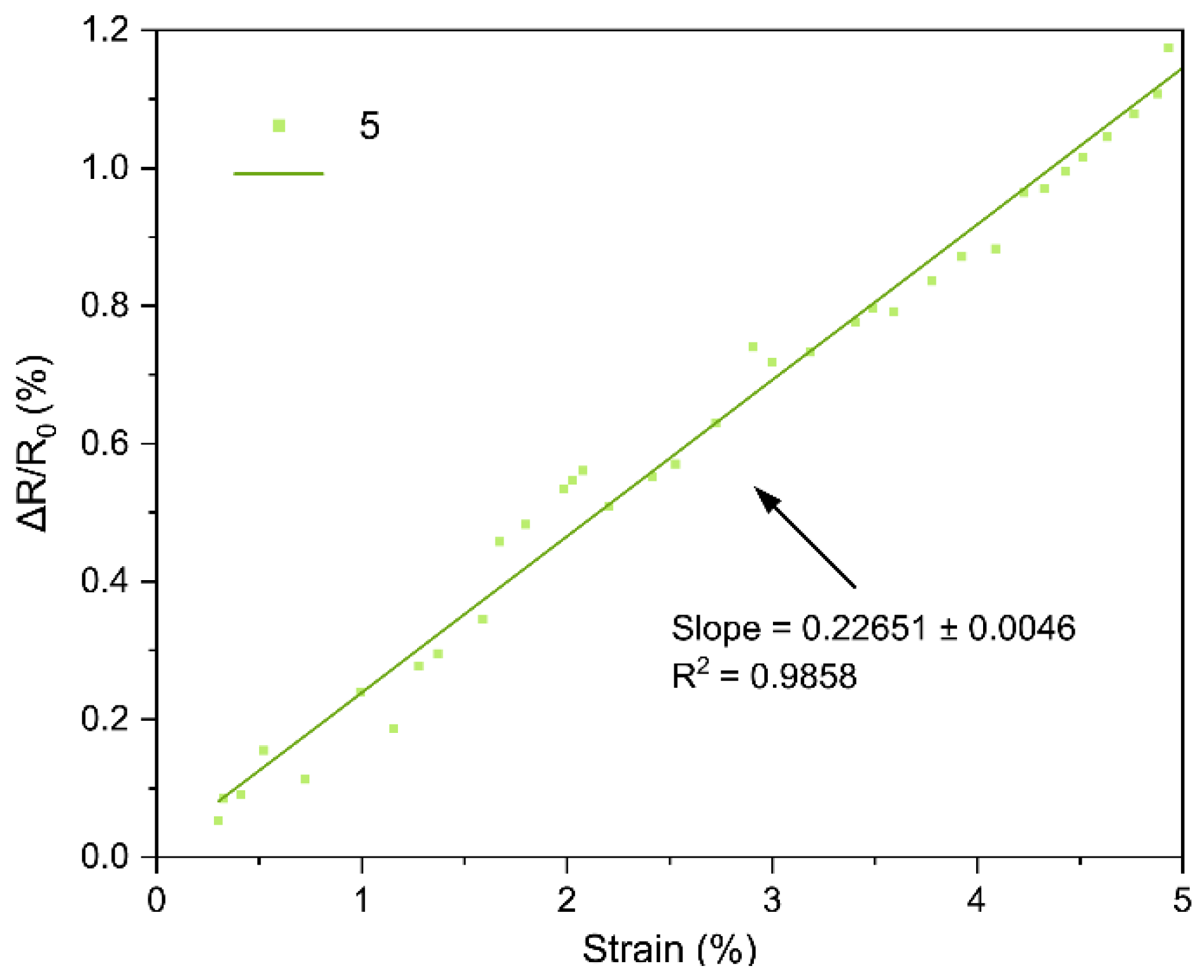

- Low-power laser scribing of polyimide produced porous graphene-like conductive patterns suitable for strain sensing. Laser power was the most critical parameter, yielding sheet resistances down to ~20 Ω sq−1 and a gauge factor up to ~1.1.

- Increasing the number of laser passes (multiple engravings) deteriorated graphene material quality and significantly reduced the strain gauge factor of the sensor.

- A 450 nm diode laser can be used to fabricate low-cost, flexible graphene strain sensors without chemical processes. This approach enables accessible production of strain gauges on polymer substrates for flexible electronics and structural health monitoring.

- The feasibility demonstrated here suggests that inexpensive diode lasers could be deployed for on-demand graphene-based sensor fabrication, potentially accelerating research and applications in wearable and flexible sensor technology.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Equipment

- CNC laser engraver Ortur LU2-4 (Ortur, China) with LU2-4 diode module, wavelength 450 nm, peak output ≈ 5 W.

- Controlled by GRBL firmware; scanning speed set at 1000 mm·min−1.

- Spot size at focal plane ≈ 0.2 mm.

- Digital thermohygrometer (China), accuracy ±2% RH and ±1 °C.

- SEM: ASPEX PSEM Express (USA, 15 kV).

- FE-SEM: JEOL JSM-7100F (JEOL Ltd., Japan), up to 100,000× magnification.

- EDS: Oxford Instruments (UK) integrated in FE-SEM.

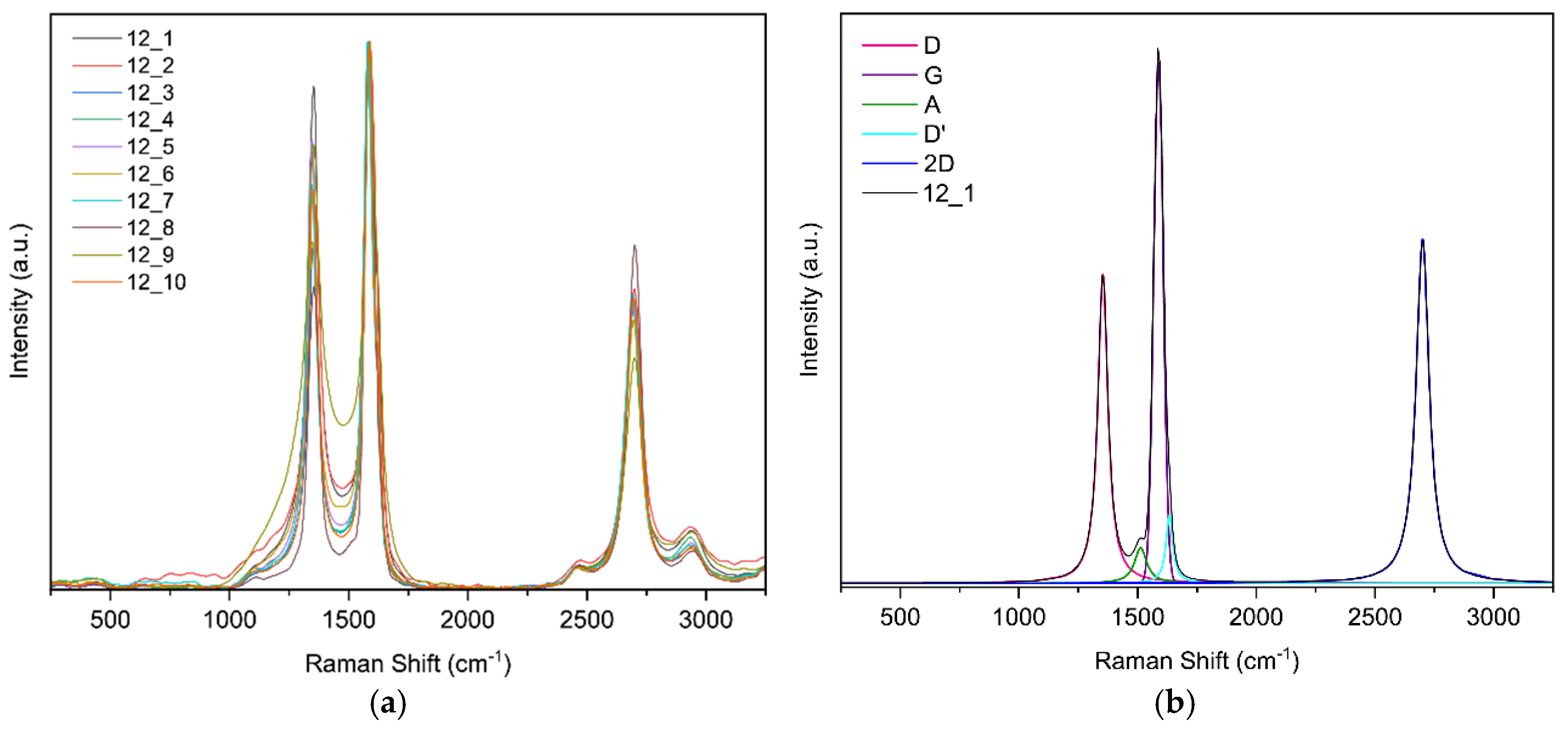

- Raman: Horiba LabRAM Evolution (Horiba Scientific, France), 532 nm laser (50 mW, filtered to 10%).

- Power supply: Keysight E36100A (Keysight Technologies, USA), accuracy ±0.05%.

- Multimeter: Keysight 34461A (Keysight Technologies, USA), accuracy ±0.01%.

- DAQ: National Instruments USB-6009 (NI, USA).

- Mechanical tests: Universal testing machine Tinius Olsen H25KS (USA), load cell accuracy ±0.5%.

2.2. Experimental Design

- Number of passes: 1 or 2;

- Laser power: 0.33, 0.44, and 0.55 W;

- Focal distance: 50 mm and 51 mm.

- Sheet resistance (van der Pauw method).

- Microstructure and composition (SEM, EDS).

- Structural order (Raman spectroscopy).

- Strain sensitivity (gauge factor from bending tests).

2.3. Fabrication of LIG Strain Sensors

2.4. Morphological and Chemical Characterization

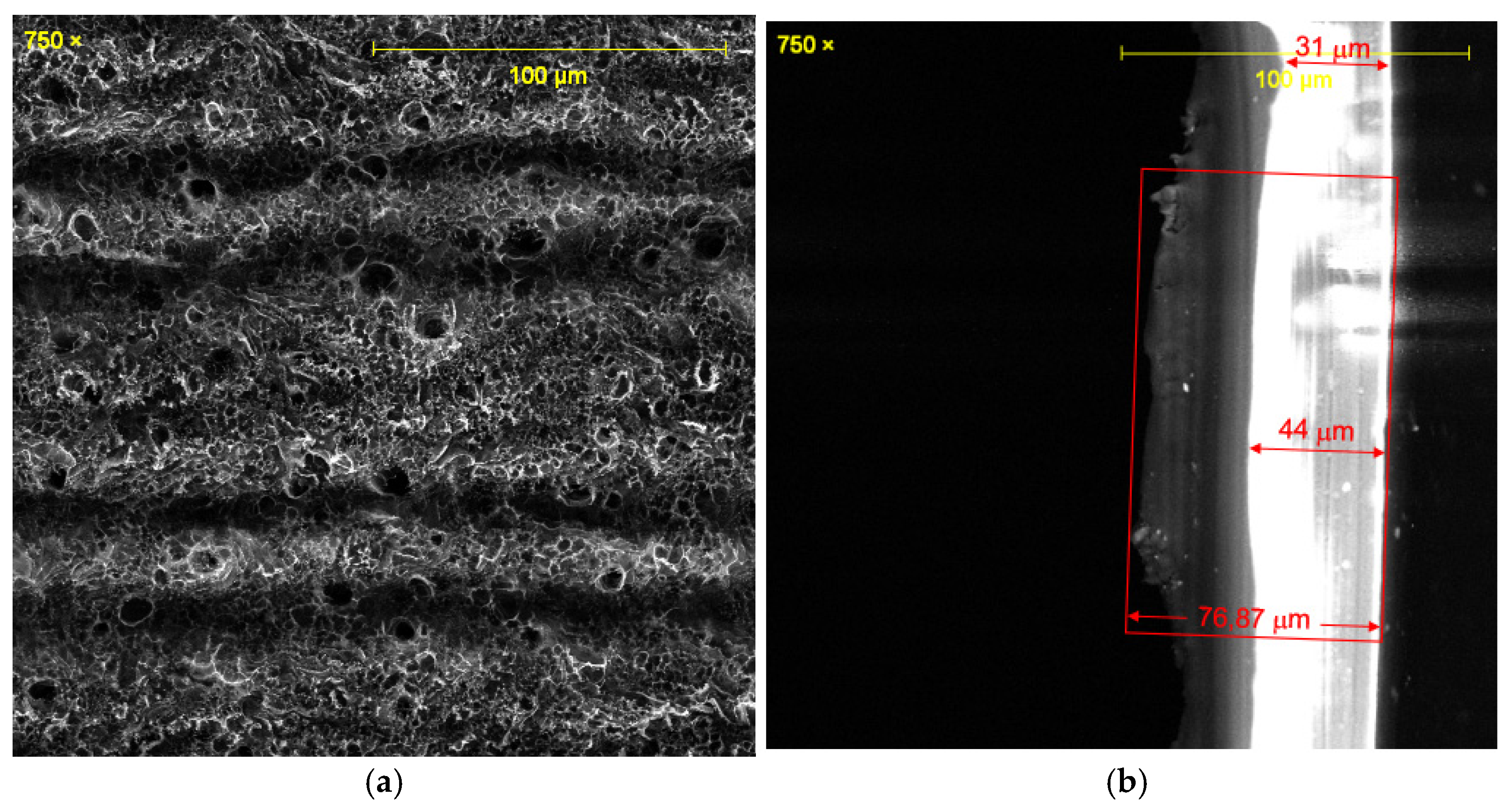

- Low magnification (200–5000×) was used to check pattern continuity and roughness.

- High magnification (up to 100,000×) revealed pore structure.

- Line spacing and overlap (~75–80%) were measured from SEM images.

2.5. Raman Spectroscopy

2.6. Electrical Characterization by the Van der Pauw Method

- Four copper electrodes were placed at the corners of the LIG pattern using silver ink.

- A source-meter applied currents between 0.1–1 mA while voltages were recorded.

- The Van der Pauw equation was used to calculate the sheet resistance:

2.7. Bending Tests and Gauge Factor Determination

2.8. Fluence Calculation

3. Results

Laser-Induced Graphene Morphology and Composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holkar, C.R.; Jain, S.S.; Jadhav, A.J.; Pinjari, D.V. Scale-Up Technologies for Advanced Nanomaterials for Green Energy: Feasibilities and Challenges. In Nanomaterials for Green Energy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 433–455. [Google Scholar]

- Dhinakaran, V.; Lavanya, M.; Vigneswari, K.; Ravichandran, M.; Vijayakumar, M.D. Review on exploration of graphene in diverse applications and its future horizon. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Manchester. Applications—Graphene. Available online: https://www.graphene.manchester.ac.uk/learn/applications/ (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Waters, R. Graphene for Electronics Applications with Lilei Ye|Graphene Flagship. Available online: https://graphene-flagship.eu/graphene/news/graphene-for-electronics-applications-with-lilei-ye/ (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Safian, M.T.-U.; Umar, K.; Mohamad Ibrahim, M.N. Synthesis and scalability of graphene and its derivatives: A journey towards sustainable and commercial material. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwande, D.; Huyghebaert, C.; Wang, C.-H.; Serna, M.I.; Goossens, S.; Li, L.-J.; Wong, H.-S.P.; Koppens, F.H.L. Graphene and two-dimensional materials for silicon technology. Nature 2019, 573, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Du, K.; Yan, Y. Improving the electrical conductivity of copper/graphene composites by reducing the interfacial impurities using spark plasma sintering diffusion bonding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Liang, F.; Zhu, J.; Shen, P.K. The role of graphene in rechargeable lithium batteries: Synthesis, functionalisation, and perspectives. Nano Mater. Sci. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Arfin, T.; Khan, A.U. Graphene nanomaterials: Chemistry and pharmaceutical perspectives. In Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery and Therapy; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 373–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ruiz-Zepeda, F.; Ye, R.; Samuel, E.L.G.; Yacaman, M.J.; Yakobson, B.I.; Tour, J.M. Laser-Induced Porous Graphene Films from Commercial Polymers. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Wang, L.; Tang, X.; Qian, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y. Facile fabrication of rGO/LIG-based temperature sensor with high sensitivity. Mater. Lett. 2021, 304, 130637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D790–17; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Jeong, S.Y.; Lee, J.U.; Hong, S.M.; Lee, C.W.; Hwang, S.H.; Cho, S.C.; Shin, B.S. Highly skin-conformal laser-induced graphene-based human motion monitoring sensor. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.-S.; Lei, Z.-Y.; Wang, H.-J.; Su, C.-Y.; Dai, C.-L.; Tsai, Y.-C. Laser-Induced Graphene Stretchable Strain Sensor with Vertical and Parallel Patterns. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetry, A.; Sharifuzzaman, M.; Yoon, H.; Sharma, S.; Xuan, X.; Park, J.Y. MoS2-Decorated Laser-Induced Graphene for a Highly Sensitive, Hysteresis-free, and Reliable Piezoresistive Strain Sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 22531–22542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmeggiani, M.; Zaccagnini, P.; Stassi, S.; Fontana, M.; Bianco, S.; Nicosia, C.; Pirri, C.F.; Lamberti, A. PDMS/Polyimide Composite as an Elastomeric Substrate for Multifunctional Laser-Induced Graphene Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 33221–33230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyk, B.; Silva, B.F.R.; Carvalho, A.F.; Silvestre, S.; Fernandes, A.J.S.; Martins, R.; Fortunato, E.; Costa, F.M. Laser-Induced Graphene from Paper for Mechanical Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 10210–10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, L.; Wang, G.; Wang, D.; Ding, X.; Luo, S. Combined extrusion-printed and laser-induced graphene enabled self-sensing composites with a strategic roadmap toward optimization of piezoresistivity. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 149, 106553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, M. Wireless Battery-Free Broad-Band Sensor for Wearable Multiple Physiological Measurement. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardaci, V. Laser Synthesized Graphene and Its Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, M.S.A.; Che Azurahanim, C.A.; Raba’ah, S.A.; Ruzniza, M.Z. Low cost and green approach in the reduction of graphene oxide (GO) using palm oil leaves extract for potential in industrial applications. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaidarova, A.; Khan, M.A.; Marengo, M.; Swanepoel, L.; Przybysz, A.; Muller, C.; Fahlman, A.; Buttner, U.; Geraldi, N.R.; Wilson, R.P.; et al. Wearable multifunctional printed graphene sensors. npj Flex. Electron. 2019, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Peng, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Nilewski, L.G.; Lin, J.; Tour, J.M. In Situ Formation of Metal Oxide Nanocrystals Embedded in Laser-Induced Graphene. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9244–9251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; James, D.K.; Tour, J.M. Laser-Induced Graphene: From Discovery to Translation. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1803621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chyan, Y.; Ye, R.; Li, Y.; Singh, S.P.; Arnusch, C.J.; Tour, J.M. Laser-Induced Graphene by Multiple Lasing: Toward Electronics on Cloth, Paper, and Food. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 2176–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Bakhtiyari, A.N.; Zheng, H. A Comparative Study of Laser-Induced Graphene by CO2 Infrared Laser and 355 nm Ultraviolet (UV) Laser. Micromachines 2020, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacroix, S.; Wang, H.; Heil, T.; Strauss, V. Laser-Induced Carbonization of Natural Organic Precursors for Flexible Electronics. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2020, 6, 2000463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esqueda-Barron, Y.; Perez del Pino, A.; Lebière, P.G.; Musheghyan-Avetisyan, A.; Bertran-Serra, E.; Gyorgy, E.; Logofatu, C. Erratum: Boost of Charge Storage Performance of Graphene Nanowall Electrodes by Laser-Induced Crystallization of Metal Oxide Nanostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 17957–17970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Basko, D.M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Van Ngo, T.; Le, D.Q.; Nguyen, D.C.; Do, K.H.; Le, V.H. Synthesis of Multi-Layer Graphene Films on Copper Tape by Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition Method. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 4, 035012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckmann, A.; Felten, A.; Mishchenko, A.; Britnell, L.; Krupke, R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Casiraghi, C. Probing the nature of defects in graphene by Raman spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3925–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, H.; Wu, P.; Huang, W.; Gao, W.; Fang, F.; Cai, N.; Chen, R.; Zhu, Z. Wearable flexible strain sensor based on three-dimensional wavy laser-induced graphene and silicone rubber. Sensors 2020, 20, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venezuela, P.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F. Theory of double-resonant Raman spectra in graphene: Intensity and line shape of defect-induced and two-phonon bands. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 35433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Xu, Y.T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.K.; Wang, X.P.; Qu, L.T. Recent progress in graphene-based wearable piezoresistive sensors: From 1D to 3D device geometries. Nano Mater. Sci. 2023, 5, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-H.; Park, S.; Hyeong, S.-K.; Bae, S.; Hong, J.-M.; Kim, T.-W.; Lee, S.H.; Ryu, S.; Lee, S.-K. Triboelectric effect of surface morphology controlled laser induced graphene. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 19822–19832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortur LU2-4 LF Módulo Láser 24V/2A. Available online: https://ortur.net/es-es/products/ortur-lu2-4-lf-laser-module-24v-2a-for-laser-master-2-pro-aufero-laser-1 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

| Order | Power (W) | Focal Length (mm) | Number of Passes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.330 | 50 | 1 |

| 2 | 0.33 | 50 | 2 |

| 3 | 0.33 | 51 | 1 |

| 4 | 0.33 | 51 | 2 |

| 5 | 0.44 | 50 | 1 |

| 6 | 0.44 | 50 | 2 |

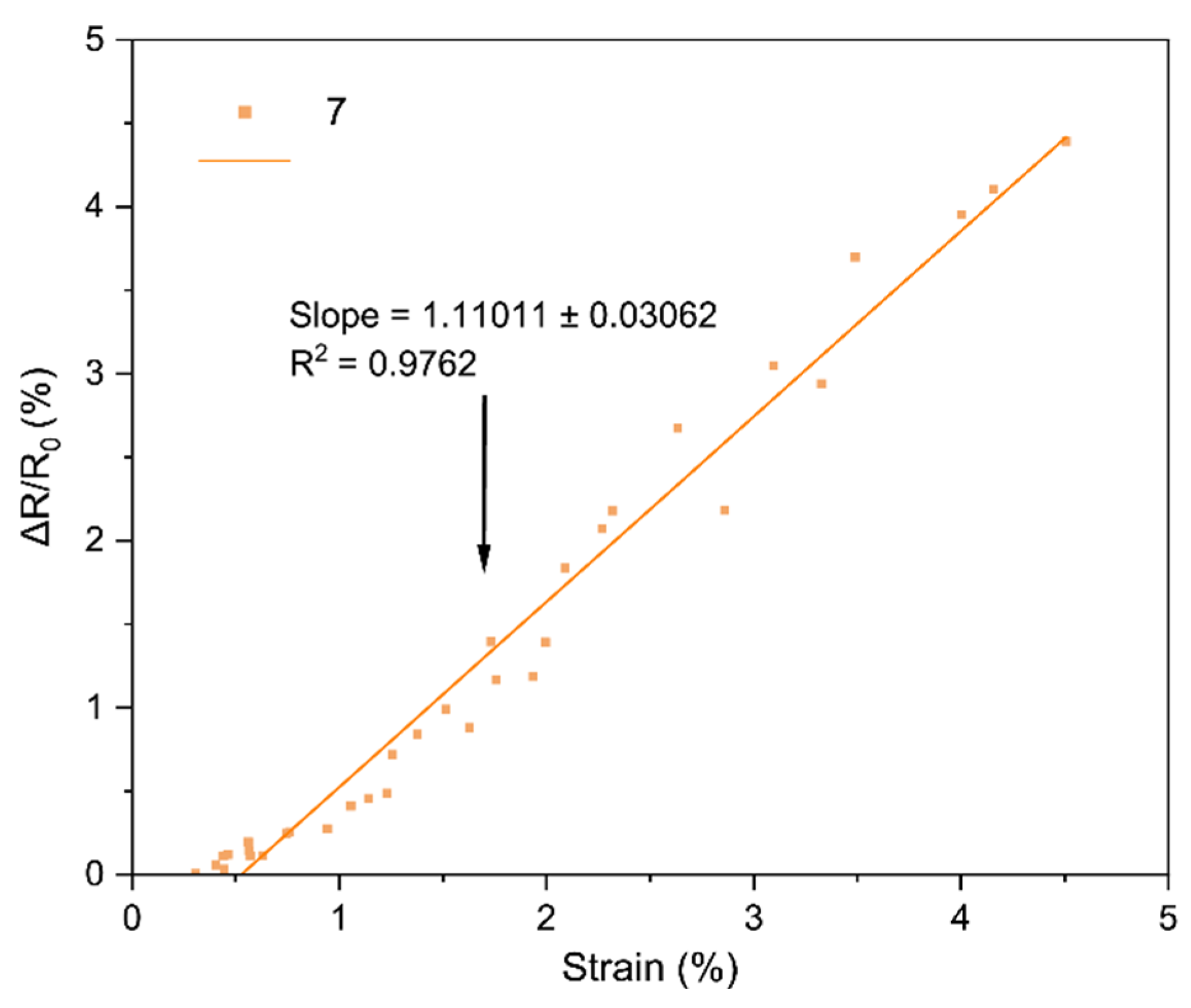

| 7 | 0.44 | 51 | 1 |

| 8 | 0.44 | 51 | 2 |

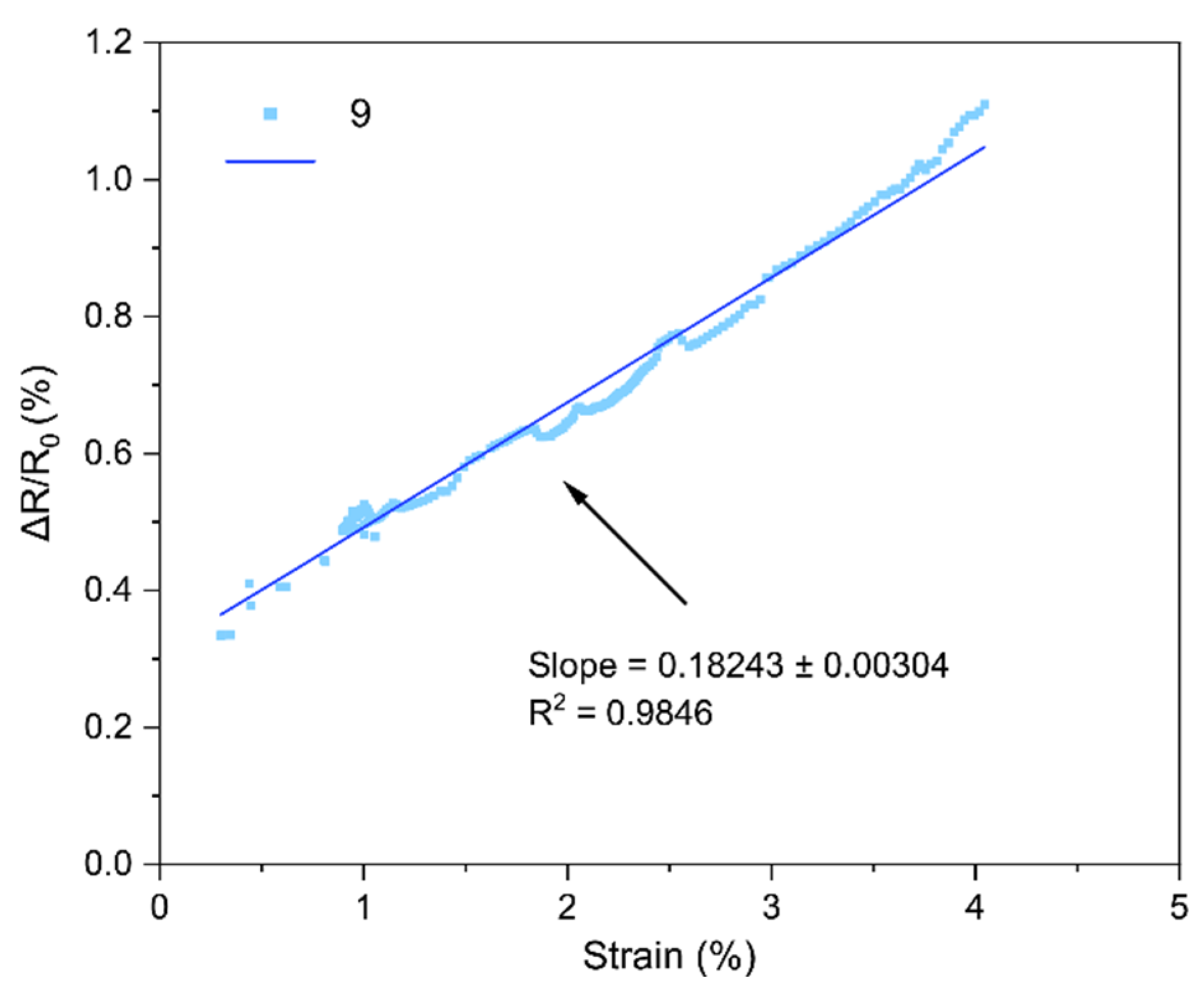

| 9 | 0.55 | 50 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.55 | 50 | 2 |

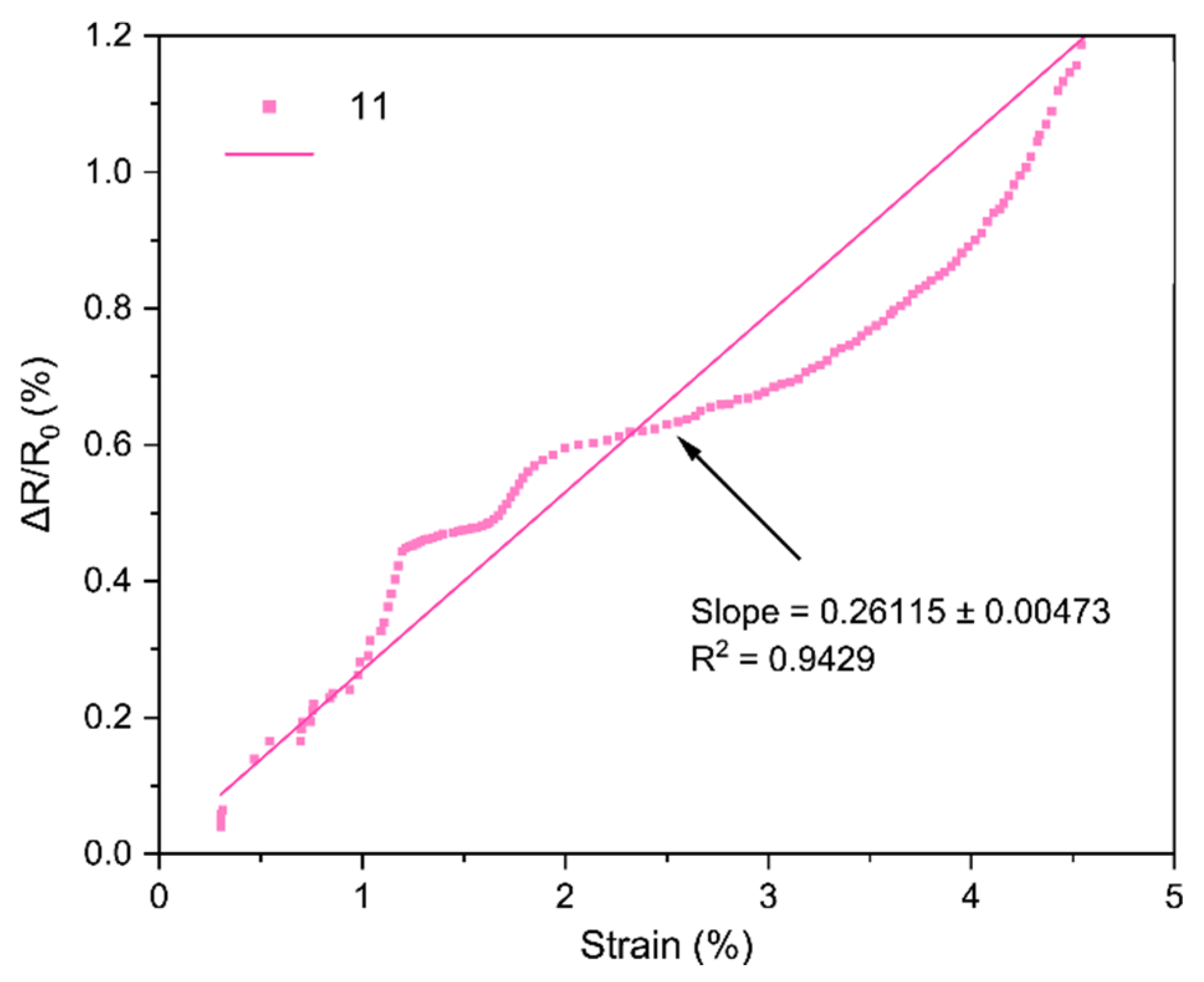

| 11 | 0.55 | 51 | 1 |

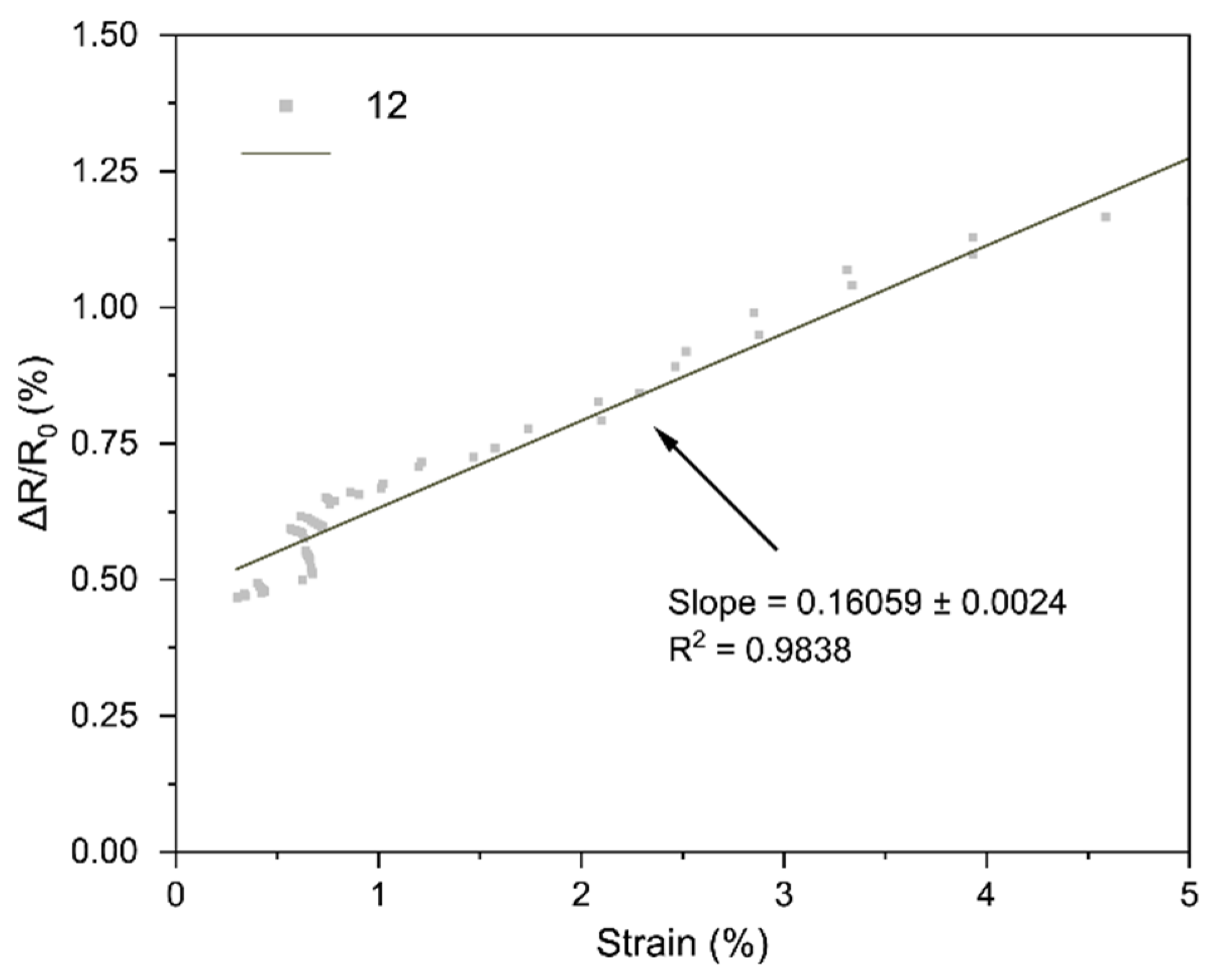

| 12 | 0.55 | 51 | 2 |

| Spectrum Label | Spectrum 2 | Spectrum 3 | Spectrum 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 9606 | 10,000 | 10,000 |

| O | 394 | - | - |

| Total | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 |

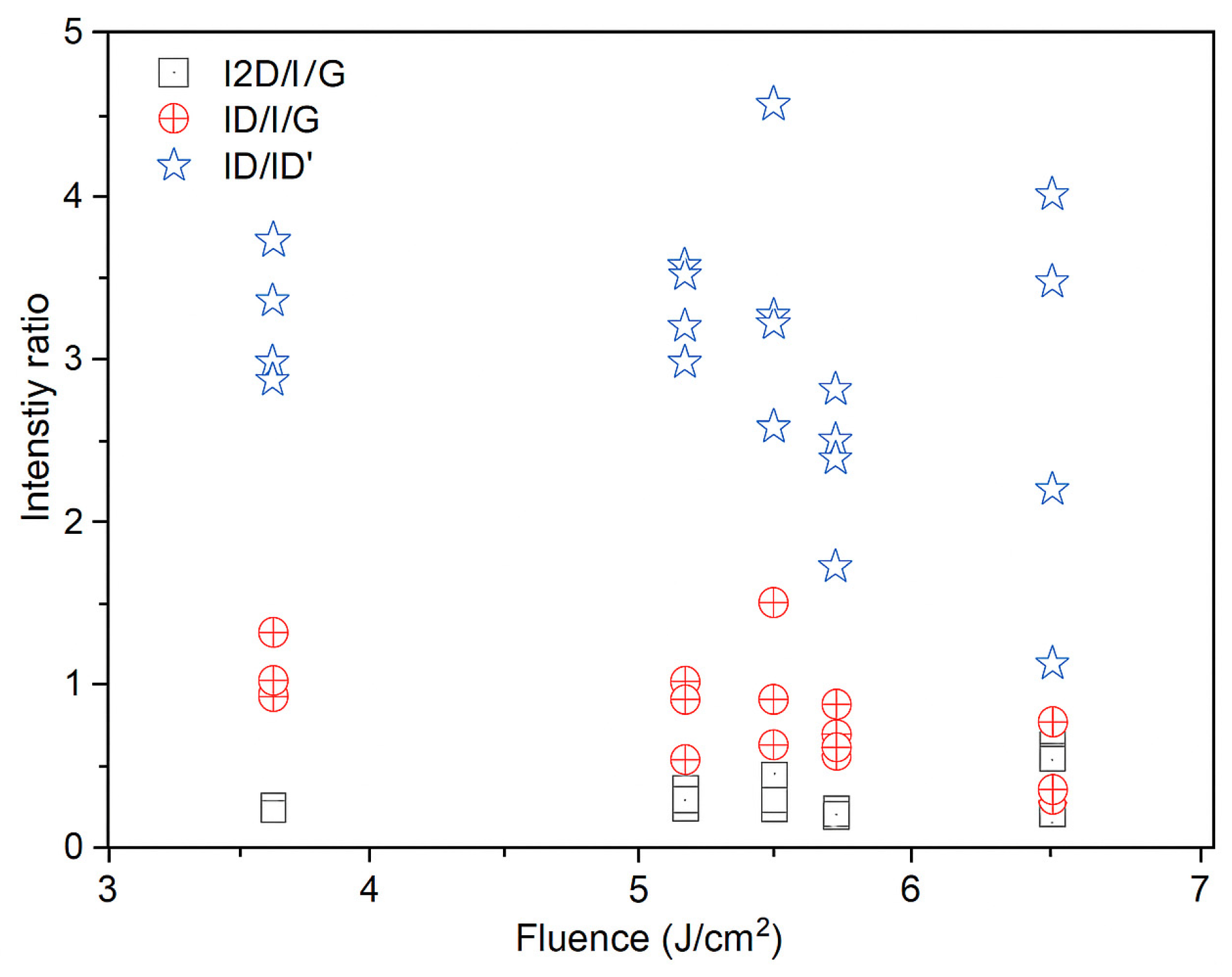

| Sample | Point | ID (a.u.) | IA (a.u.) | IG (a.u.) | ID’ (a.u.) | I2D (a.u.) | I2D/IG | ID/IG | ID/ID’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1_1 | 0.96 | 0.08 | 0.85 | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.47 | 1.12 | 3.67 |

| 1_2 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.88 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 1.11 | 3.36 | |

| 1_3 | 0.97 | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 1.49 | 2.79 | |

| 1_10 | 0.93 | 0.13 | 0.76 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 1.22 | 2.87 | |

| σx | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.051 | 0.019 | 0.040 | 0.025 | 0.087 | 0.208 | |

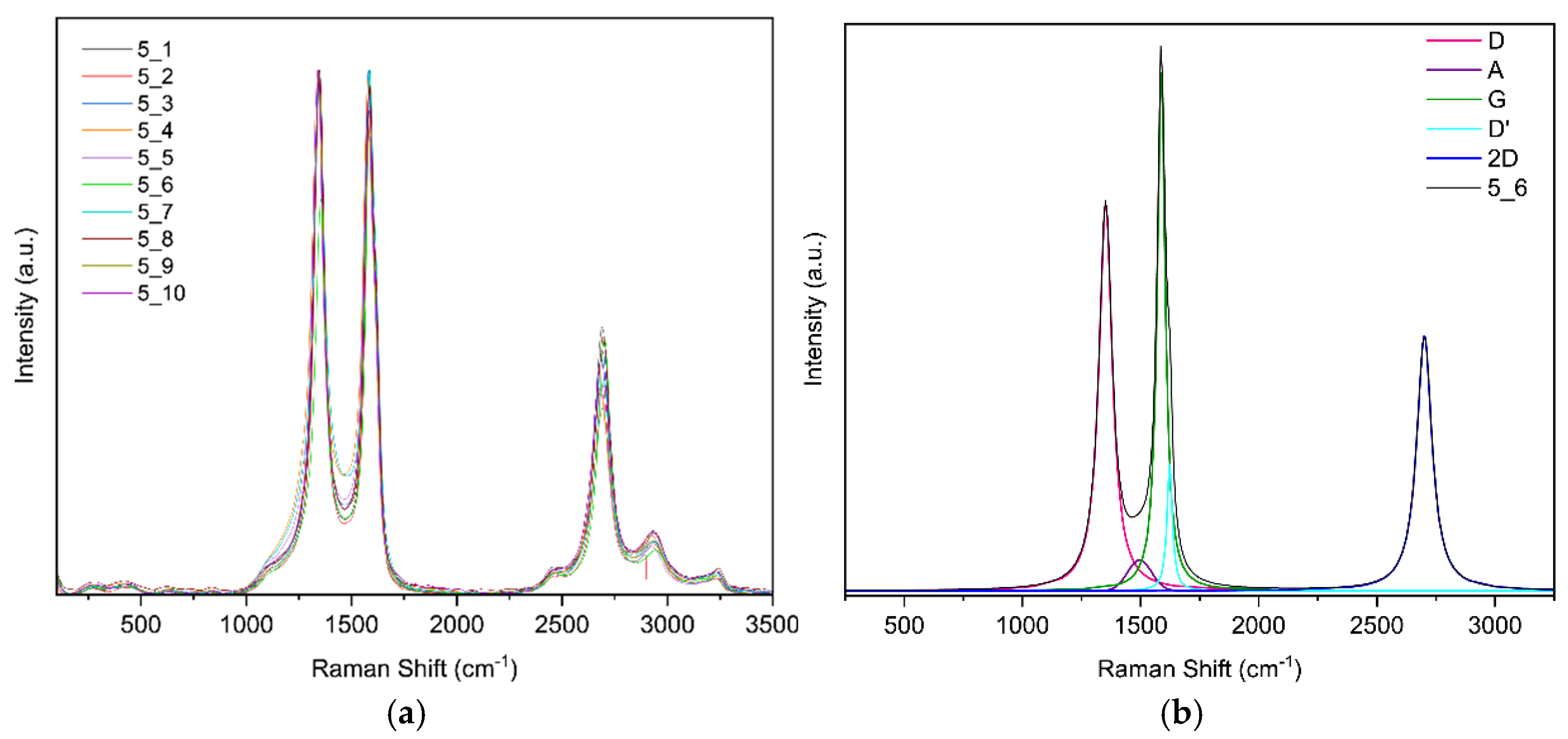

| 5 | 5_1 | 0.97 | 0.06 | 0.85 | 0.27 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 1.14 | 3.62 |

| 5_2 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 1.19 | 3.56 | |

| 5_6 | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.75 | 3.07 | |

| 5_8 | 0.97 | 0.06 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 1.10 | 3.28 | |

| σx | 0.065 | 0.002 | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.101 | 0.127 | |

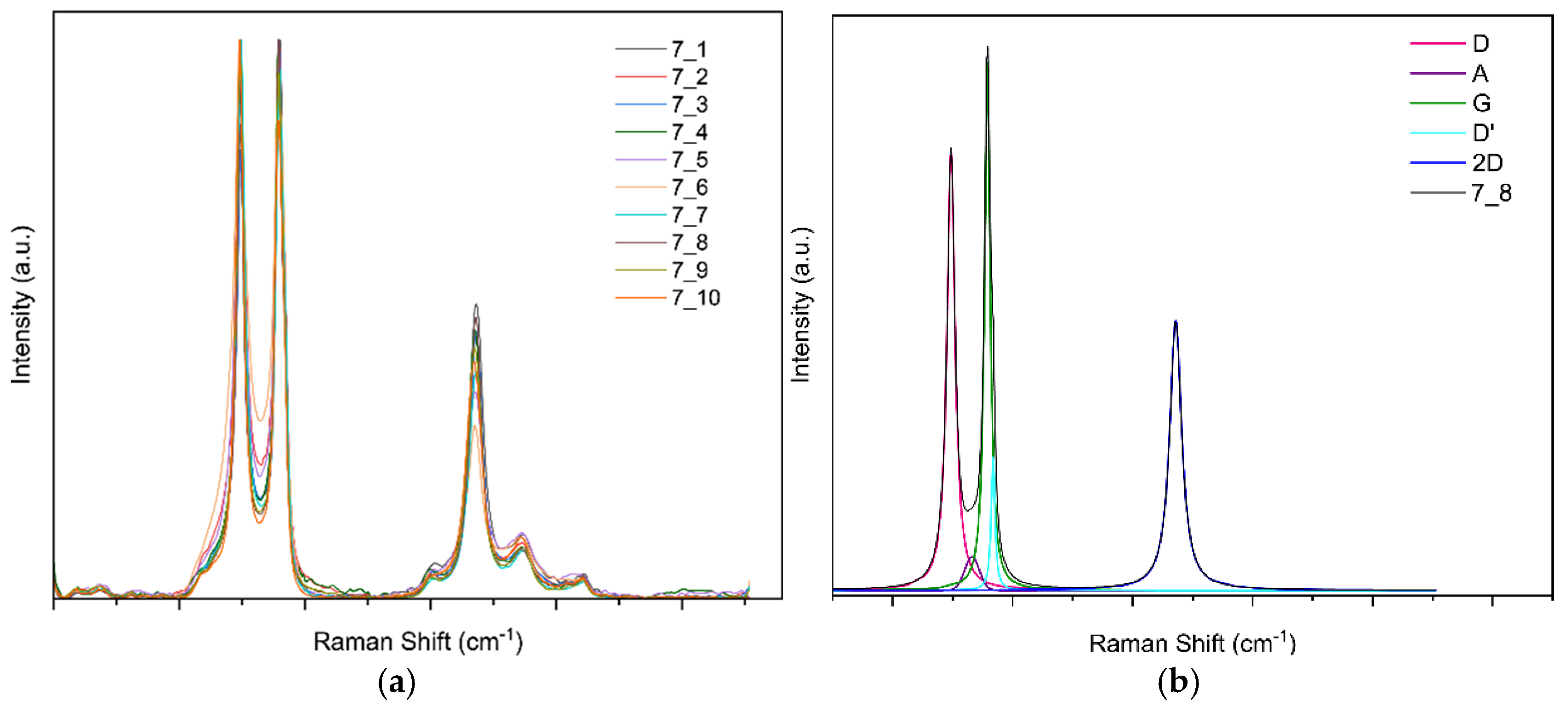

| 7 | 7_3 | 0.74 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.81 | 2.70 |

| 7_4 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 1.66 | 4.57 | |

| 7_7 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.87 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 1.10 | 3.34 | |

| 7_8 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.83 | 3.30 | |

| σx | 0.049 | 0.180 | 0.113 | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.044 | 0.197 | 0.391 | |

| 9 | 9_3 | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 1.06 | 2.52 |

| 9_4 | 0.70 | 0.09 | 0.89 | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.79 | 2.62 | |

| 9_5 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.89 | 2.91 | |

| 9_6 | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.77 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.82 | 1.88 | |

| σx | 0.055 | 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.060 | 0.216 | |

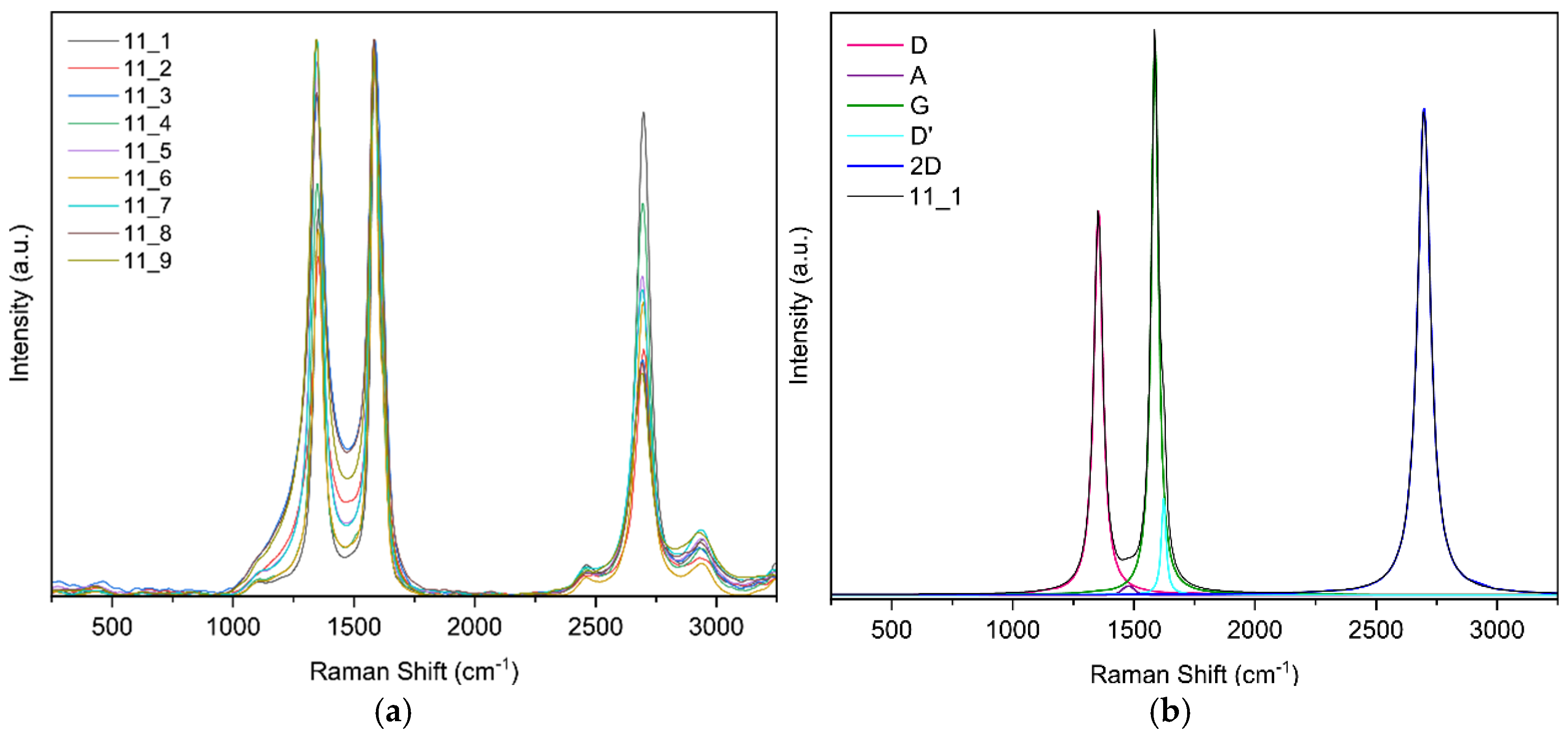

| 11 | 11_1 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.17 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 4.01 |

| 11_2 | 0.54 | 0.07 | 0.92 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 2.41 | |

| 11_4 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 1.40 | |

| 11_6 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 3.52 | |

| σx | 0.045 | 0.013 | 0.063 | 0.088 | 0.099 | 0.128 | 0.104 | 0.584 | |

| 12 | 12_3 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 3.51 |

| 12_6 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 0.96 | 0.19 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 3.06 | |

| 12_7 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.97 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 3.31 | |

| 12_8 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.95 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 4.54 | |

| σx | 0.035 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.033 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.327 |

| Sample | Strain Gauge Factor |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0981 |

| 5 | 0.2265 |

| 7 | 1.1101 |

| 9 | 0.1824 |

| 11 | 0.2612 |

| 12 | 0.1606 |

| Sample ID | Laser Power (W) | Focal Distance (mm) | Passes | Gauge Factor (GF) | Notes/Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.33 | 50 | 1 | 0.098 | Baseline, low power |

| 5 | 0.44 | 50 | 1 | 0.227 | Improvement due to higher power |

| 7 | 0.44 | 51 | 1 | 1.110 | Best GF, high sensitivity |

| 9 | 0.55 | 50 | 1 | 0.182 | Higher power, stable response |

| 11 | 0.55 | 51 | 1 | 0.261 | Moderate GF |

| 12 | 0.55 | 51 | 2 | 0.161 | Double pass reduced performance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paucar, Y.I.; Pantoja-Suárez, F.; Bertran-Serra, E.; Sánchez, F.; Moreno, K. Laser-Induced Graphene on Polyimide: Material Characterization Toward Strain-Sensing Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247641

Paucar YI, Pantoja-Suárez F, Bertran-Serra E, Sánchez F, Moreno K. Laser-Induced Graphene on Polyimide: Material Characterization Toward Strain-Sensing Applications. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247641

Chicago/Turabian StylePaucar, Yessenia Ibeth, Fernando Pantoja-Suárez, Enric Bertran-Serra, Fernando Sánchez, and Katherine Moreno. 2025. "Laser-Induced Graphene on Polyimide: Material Characterization Toward Strain-Sensing Applications" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247641

APA StylePaucar, Y. I., Pantoja-Suárez, F., Bertran-Serra, E., Sánchez, F., & Moreno, K. (2025). Laser-Induced Graphene on Polyimide: Material Characterization Toward Strain-Sensing Applications. Sensors, 25(24), 7641. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247641