Meta Variational Memory Transformer for Anomaly Detection of Multivariate Time Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

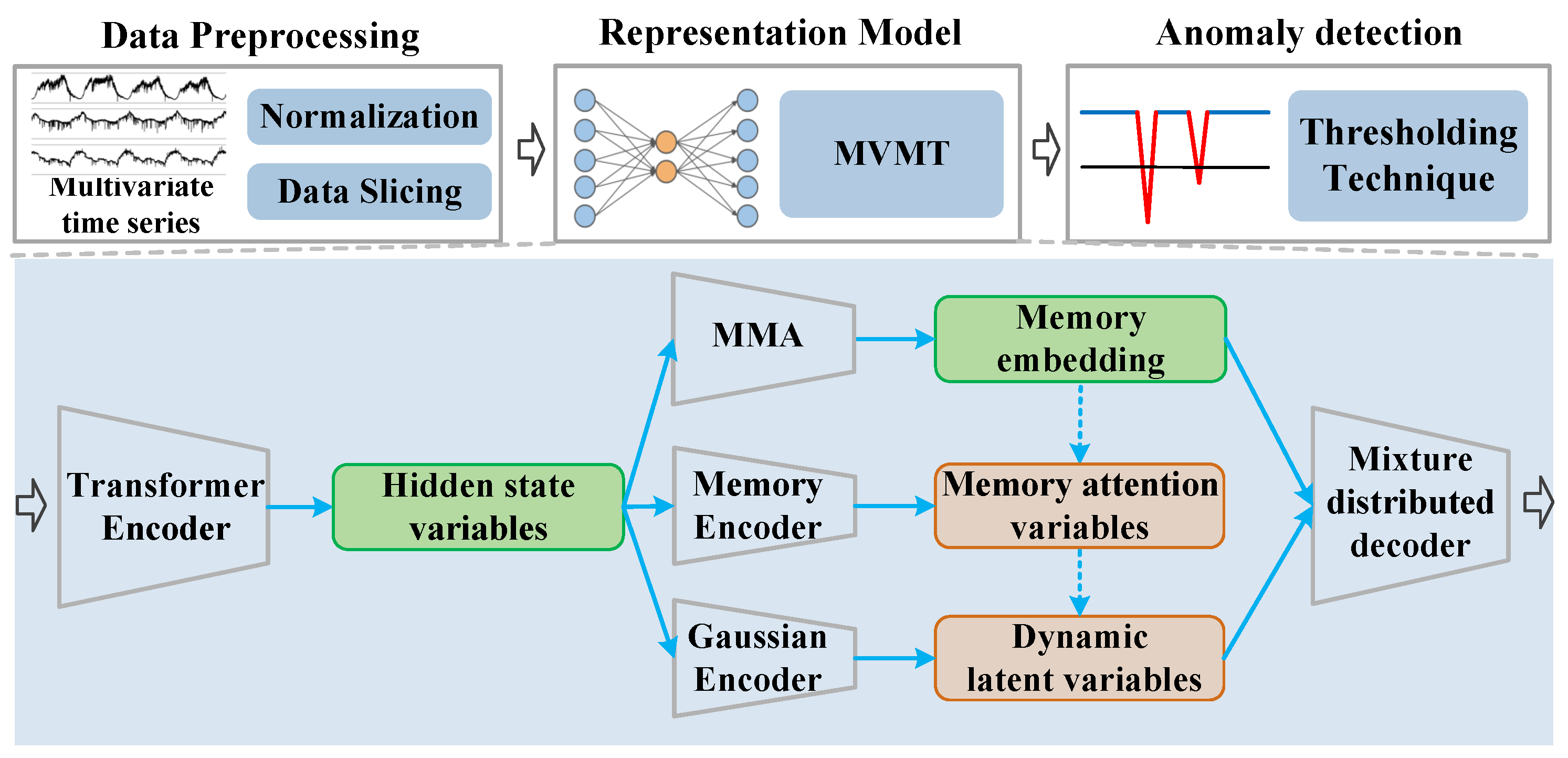

- To consider diverse nomal patterns within MTSs and achieve anomaly detection, we propose a hierarchical Bayesian network named MVMT. MVMT consists of a developed MMA module that captures and stores various temporal dependencies of MTSs, a memory-guided generative module to capture the shared diverse temporal information, as well as a transformer-powered inference module for accurate posterior approximation.

- We carefully design an upward–downward variational inference model built upon the transformer blocks for MVMT to approximate the posterior for the latent variables.

- While most existing methods rely on distinct parameter sets for each MTS, the proposed MVMT utilizes a single group of parameters to model diverse MTSs, allowing it to effectively capture multiple patterns within a unified framework.

- We perform thorough experiments on six real-world datasets. The quantitative comparison results demonstrate that MVMT surpasses state-of-the-art methods in terms of F1-score with fewer parameters. The qualitative analysis reveals that it effectively captures diverse dynamic memory patterns within different MTSs.

2. Related Work

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Problem Definition

3.2. Anomaly Detection Based on MVMT

3.3. Data Preprocess

4. Methodology

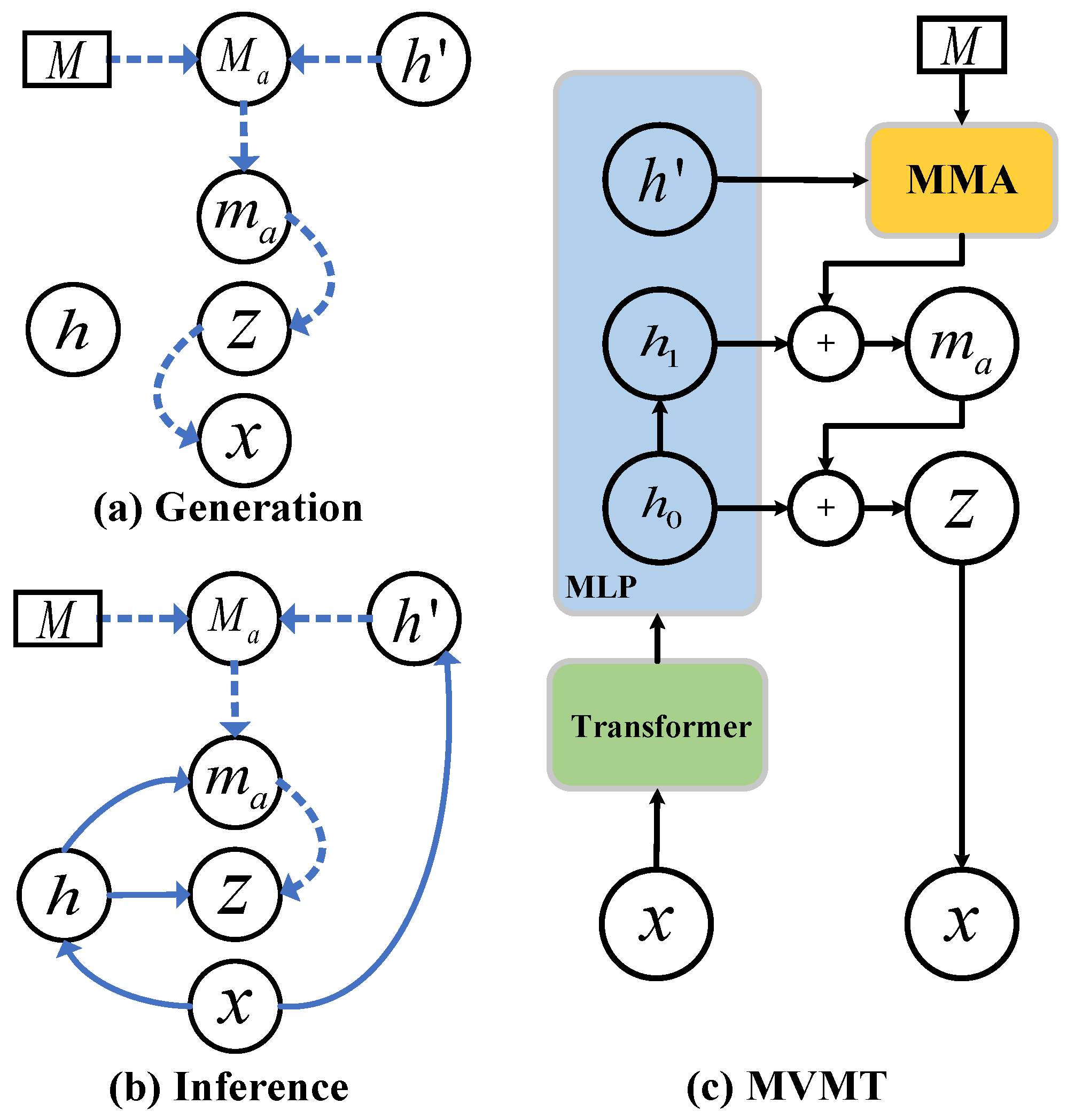

4.1. Meta Variational Memory Transformer

4.1.1. Meta Memory Attention Module

4.1.2. Probablistic Memory Generative Model

4.1.3. Inference Model

4.2. Model Properties

4.2.1. Learnable Memory Prior

4.2.2. One Model for All MTSs

4.2.3. Probability Modeling of Hidden Space and Generative Process

4.2.4. Transformer for Time Series

4.2.5. Beneficial to Process Large Data

5. Model Training

| Algorithm 1 Upward–Downward Autoencoding Variational Inference for MVMT |

|

6. Experimental Evaluation

6.1. Experiment Setup

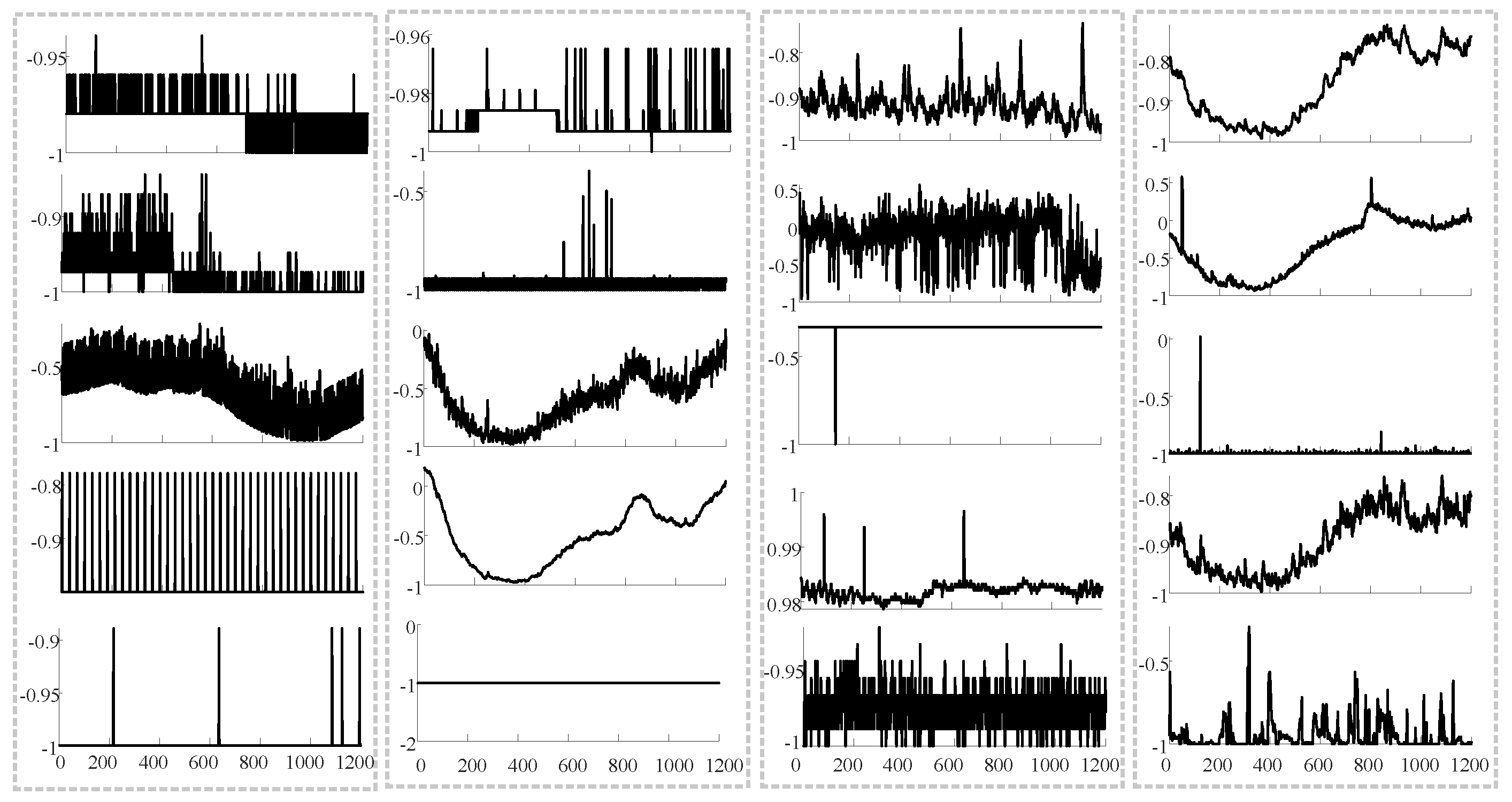

6.1.1. Datasets

6.1.2. Baselines

6.1.3. Implementation Details

6.1.4. Metric and One-for-All Setting

6.2. Main Result

6.2.1. Quantitative Comparison

6.2.2. Ablation Study

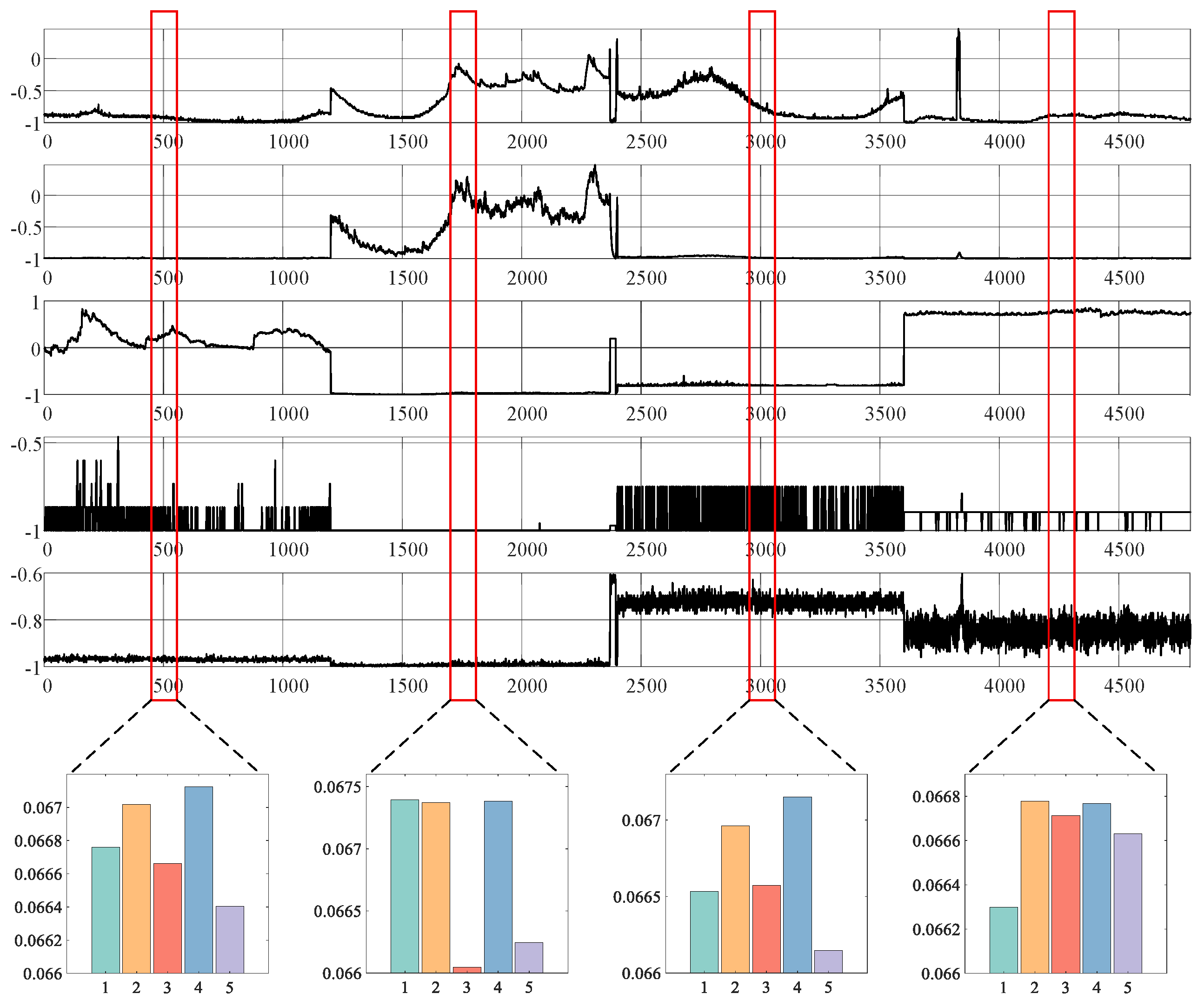

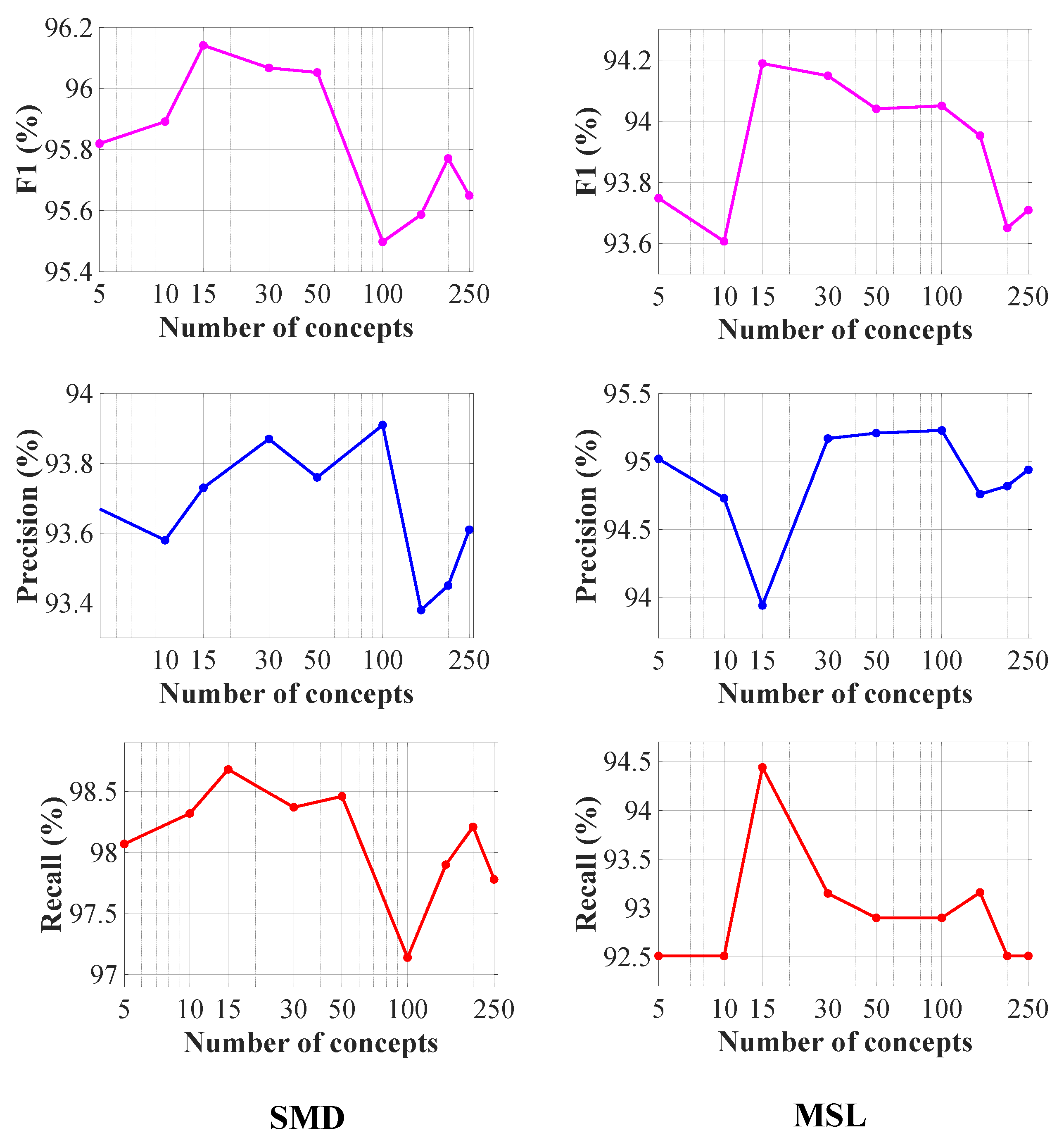

6.2.3. Meta Memory Attention

6.2.4. Information Capacity of MVMT

6.2.5. Adapt to New MTSs

6.2.6. Qualitative Analysis

6.2.7. Time Efficiency

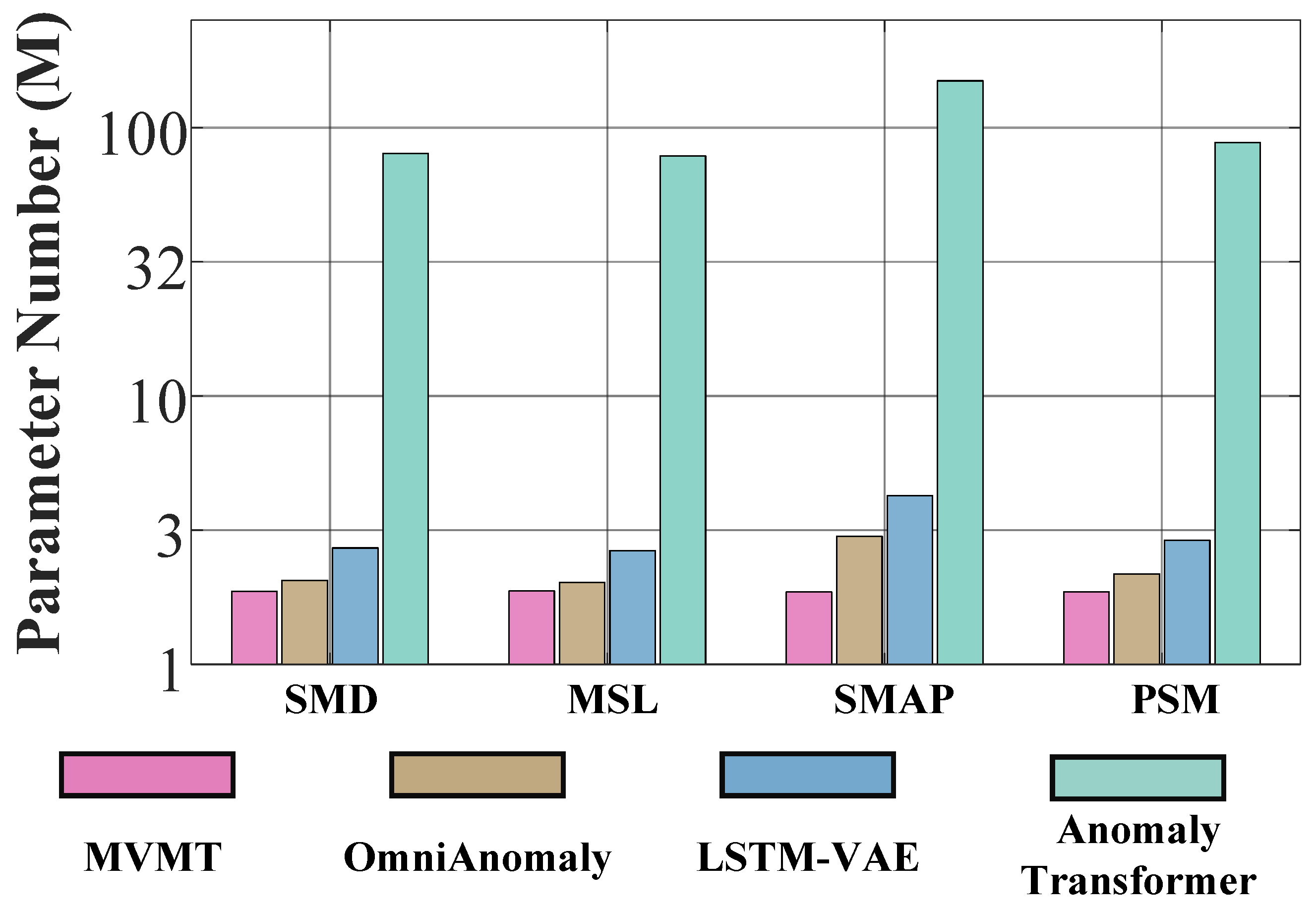

6.2.8. Number of Parameters

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, C.; Liu, R.; Sun, W.; Pei, D. Robust anomaly detection for multivariate time series through stochastic recurrent neural network. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD 2019, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2828–2837. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, S.; Wen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, J.; Wu, W.; et al. Detecting outlier machine instances through gaussian mixture variational autoencoder with one dimensional cnn. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2021, 71, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Su, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pei, D.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Tang, J. Ctf: Anomaly detection in high-dimensional time series with coarse-to-fine model transfer. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2021, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–13 May 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Lin, T.; Liu, C.; Jiang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z. SDFVAE: Static and dynamic factorized VAE for anomaly detection of multivariate CDN kpis. In Proceedings of the WWW, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 3076–3086. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Sun, Y.; Pei, D.; Luo, J.; Jing, X.; Feng, M. Opprentice: Towards practical and automatic anomaly detection through machine learning. In Proceedings of the ACM IMC, Tokyo, Japan, 28–30 October 2015; pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Mahajan, R.; Sridharan, B.; Zhang, Z. A provider-side view of web search response time. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM, Hong Kong, China, 12–16 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Pei, D.; Chen, J.; Qiao, H.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Z. Unsupervised anomaly detection for intricate kpis via adversarial training of VAE. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM, Paris, France, 29 April–2 May 2019; pp. 1891–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Chen, W.; Zhao, N.; Li, Z.; Bu, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Pei, D.; Feng, Y.; et al. Unsupervised anomaly detection via variational auto-encoder for seasonal kpis in web applications. In Proceedings of the WWW 18, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 15:1–15:58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, T.; Moon, J. A hybrid machine learning approach to network anomaly detection. Inf. Sci. 2007, 177, 3799–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Kimura, A.; Naya, F.; Sawada, H. Change-point detection with feature selection in high-dimensional time-series data. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Beijing, China, 3–9 August 2013; pp. 1827–1833. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Lumezanu, C.; Cheng, W.; Ni, J.; Zong, B.; Chen, H.; Chawla, N.V. A deep neural network for unsupervised anomaly detection and diagnosis in multivariate time series data. In Proceedings of the AAAI, Beijing, China, 3–9 August 2019; pp. 1409–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Chen, D.; Jin, B.; Shi, L.; Goh, J.; Ng, S. MAD-GAN: Multivariate anomaly detection for time series data with generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the ICANN, Munich, Germany, 17–19 September 2019; pp. 703–716. [Google Scholar]

- Audibert, J.; Michiardi, P.; Guyard, F.; Marti, S.; Zuluaga, M.A. USAD: Unsupervised anomaly detection on multivariate time series. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD, Virtual, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 3395–3404. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, P.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Anand, G.; Vig, L.; Agarwal, P.; Shroff, G. Lstm-based encoder-decoder for multi-sensor anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the ICML, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hundman, K.; Constantinou, V.; Laporte, C.; Colwell, I.; Söderstrxoxm, T. Detecting spacecraft anomalies using lstms and nonparametric dynamic thresholding. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chalapathy, R.; Chawla, S. Deep learning for anomaly detection: A survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, B.; Wang, D.; Tian, L.; Zhou, M. Prototype-oriented unsupervised anomaly detection for multivariate time series. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 19407–19424. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 30, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Sun, L. Transformers in time series: A survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.07125. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Xu, S.; Xu, B. Speech-transformer: A no-recurrence sequence-to-sequence model for speech recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP, Calgary, AB, Canada, 15–20 April 2018; pp. 5884–5888. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Peng, H.; Fu, J.; Ling, H. Autoformer: Searching transformers for visual recognition. In Proceedings of the CVPR, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 12270–12280. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Anomaly transformer: Time series anomaly detection with association discrepancy. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.-K.; Tao, F.; Li, X.-Q.; Yang, L.-C.; Wei, Y.-P.; Beer, M. Physics-embedding multi-response regressor for time-variant system reliability assessment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 263, 111262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Cui, L.; Shen, Y.; Yang, K.; Lu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Le, X. A unified model for multi-class anomaly detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.03687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilalta, R.; Drissi, Y. A perspective view and survey of meta-learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2002, 18, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepp, H.; Jurgen, S. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Matteson, D.S. Probabilistic transformer for time series analysis. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, Online, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 23592–23608. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Argyriou, A.; Liu, C.; Lin, T.; Wang, P.; Xu, Z.; Chen, B. Switching gaussian mixture variational rnn for anomaly detection of diverse cdn websites. In Proceedings of the INFOCOM 2022, London, UK, 2–5 May 2022; pp. 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Cho, S. Variational autoencoder based anomaly detection using reconstruction probability. Spec. Lect. IE 2015, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Siffer, A.; Fouque, P.-A.; Termier, A.; Largouet, C. Anomaly detection in streams with extreme value theory. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017; pp. 1067–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Tuli, S.; Casale, G.; Jennings, N.R. Tranad: Deep transformer networks for anomaly detection in multivariate time series data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.07284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti, M.; Miksovic, C.; Giurgiu, I.; Gschwind, T.; Scotton, P. Attention-based interpretability with concept transformers. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Vienna, Austria, 3–5 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.S.; Mumford, D. Hierarchical bayesian inference in the visual cortex. JOSA A 2003, 20, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blei, D.M.; Jordan, M.I. Variational inference for dirichlet process mixtures. Bayesian Anal. 2006, 1, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Kastner, K.; Dinh, L.; Goel, K.; Courville, A.C.; Bengio, Y. A recurrent latent variable model for sequential data. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, D.V. Fiducial distributions and bayes’ theorem. J. R. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1958, 20, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, I.; Matthey, L.; Pal, A.; Burgess, C.; Glorot, X.; Botvinick, M.; Mohamed, S.; Lerchner, A. beta-vae: Learning basic visual concepts with a constrained variational framework. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Toulon, France, 24–26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulaal, A.; Liu, Z.; Lancewicki, T. Practical approach to asynchronous multivariate time series anomaly detection and localization. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD, Online, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 2485–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, A.P.; Tippenhauer, N.O. Swat: A water treatment testbed for research and training on ics security. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Workshop on Cyber-Physical Systems for Smart Water Networks (CySWater), Vienna, Austria, 11 April 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Tian, L.; Chen, B.; Dai, L.; Duan, Z.; Zhou, M. Deep variational graph convolutional recurrent network for multivariate time series anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 3621–3633. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Su, Y.; Jiao, R.; Wen, X.; Pei, D. Multivariate time series anomaly detection and interpretation using hierarchical inter-metric and temporal embedding. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD, Online, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 3220–3230. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, S.; Hooi, B.; Cheng, X.; Ye, J. Beatgan: Anomalous rhythm detection using adversarially generated time series. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Macao, China, 10–16 August 2019; pp. 4433–4439. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.; Hoshi, Y.; Kemp, C.C. A multimodal anomaly detector for robot-assisted feeding using an lstm-based variational autoencoder. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 1544–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, B.; Song, Q.; Min, M.R.; Cheng, W.; Lumezanu, C.; Cho, D.; Chen, H. Deep autoencoding gaussian mixture model for unsupervised anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yairi, T.; Takeishi, N.; Oda, T.; Nakajima, Y.; Nishimura, N.; Takata, N. A data-driven health monitoring method for satellite housekeeping data based on probabilistic clustering and dimensionality reduction. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2017, 53, 1384–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Ng, R.T.; Sander, J. Lof: Identifying density-based local outliers. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD, Dallas, TX, USA, 15–18 May 2000; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, S.; Tariq, S.; Lee, M.S.; Jung, O.; Chung, D.; Woo, S.S. Itad: Integrative tensor-based anomaly detection system for reducing false positives of satellite systems. In Proceedings of the 29th CIKM, Virtual Event, 19–23 October 2020; pp. 2733–2740. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Li, Z.; Kwok, J. Timeseries anomaly detection using temporal hierarchical one-class network. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 33, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 13016–13026. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff, L.; Vandermeulen, R.; Goernitz, N.; Deecke, L.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Binder, A.; Müller, E.; Kloft, M. Deep one-class classification. In Proceedings of the ICML, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 4393–4402. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, S.; Lee, S.; Shin, Y.; Lee, M.S.; Jung, O.; Chung, D.; Woo, S.S. Detecting anomalies in space using multivariate convolutional lstm with mixtures of probabilistic pca. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2123–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, M.P.; Mizon, G.E. Empirical analysis of macroeconomic time series: Var and structural models. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1991, 35, 887–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax, D.M.; Duin, R.P. Support vector data description. Mach. Learn. 2004, 54, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.-H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICDM, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 32, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Encoder | Decoder | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbols | Description | Symbols | Description |

| The model parameter symbol of the Anomaly Transformer | MLP weights mapped from to the mean () of | ||

| The MLP weights of feature to . | MLP bias mapped from to the mean () of | ||

| The MLP bias of feature to . | MLP weights mapped from to the variance () of | ||

| The MLP weights of feature to . | MLP bias mapped from to the variance () of | ||

| The MLP bias of feature to . | MLP weights mapped from to the mean () of z. | ||

| The MLP weights that approximate the mean () of with | MLP bias mapped from to the mean () of z. | ||

| The MLP weights that approximate the mean () of with | MLP weights mapped from to the variance () of z. | ||

| The MLP bias that approximate the mean () of | MLP bias mapped from to the variance () of z. | ||

| The MLP weights that approximate the variance () of with | MLP weights mapped from z to the mean () of x. | ||

| The MLP weights that approximate the variance () of with | MLP bias mapped from z to the mean () of x. | ||

| The MLP bias that approximate the variance () of | MLP weights mapped from z to the variance () of x. | ||

| The MLP weights that approximate the mean () of z with | MLP bias mapped from z to the variance () of x. | ||

| The MLP weights that approximate the mean () of z with | |||

| The MLP bias that approximate the mean () of z | |||

| The MLP weights that approximate the variance () of z with | |||

| The MLP weights that approximate the variance () of z with | |||

| The MLP bias that approximate the variance () of z | |||

| Dataset | SMD | MSL | SMAP | PSM | DND | SWaT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 38 | 55 | 55 | 25 | 32 | 51 |

| Window | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Training | 708,405 | 58,317 | 135,181 | 105,984 | 344,843 | 496,800 |

| Test (labeled) | 708,420 | 73,729 | 427,617 | 87,841 | 344,843 | 449,919 |

| Anomaly ratio (%) | 4.1 | 10.7 | 13.13 | 27.8 | 3.44 | 11.98 |

| Dataset | SMD | MSL | PSM | SMAP | DND | SWaT | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 |

| OC-SVM | 44.34 | 76.72 | 56.19 | 59.78 | 86.87 | 70.82 | 62.75 | 80.89 | 70.67 | 53.85 | 59.07 | 56.34 | 68.23 | 70.36 | 69.28 | 45.39 | 49.22 | 47.23 |

| IsolationForest | 42.31 | 73.29 | 53.64 | 53.94 | 86.54 | 66.45 | 76.09 | 92.45 | 83.48 | 52.39 | 59.07 | 55.53 | 69.63 | 74.21 | 71.85 | 49.29 | 44.95 | 47.02 |

| LOF | 56.34 | 39.86 | 46.68 | 47.72 | 85.25 | 61.18 | 57.89 | 90.49 | 70.61 | 58.93 | 56.33 | 57.60 | 70.24 | 74.66 | 72.38 | 72.15 | 65.43 | 68.62 |

| Deep-SVDD | 78.54 | 79.67 | 79.10 | 91.92 | 76.63 | 83.58 | 95.41 | 86.49 | 90.73 | 89.93 | 56.02 | 69.04 | 73.09 | 79.02 | 75.94 | 80.42 | 84.45 | 82.39 |

| DAGMM | 67.30 | 49.89 | 57.30 | 89.60 | 63.93 | 74.62 | 93.49 | 70.03 | 80.08 | 86.45 | 56.73 | 68.51 | 72.72 | 77.67 | 75.11 | 89.92 | 57.84 | 70.40 |

| MMPCACD | 71.20 | 79.28 | 75.02 | 81.42 | 61.31 | 69.95 | 76.26 | 78.35 | 77.29 | 88.61 | 75.84 | 81.73 | 71.52 | 75.75 | 73.57 | 82.52 | 68.29 | 74.73 |

| VAR | 78.35 | 70.26 | 74.08 | 74.68 | 81.42 | 77.90 | 90.71 | 83.82 | 87.13 | 81.38 | 53.88 | 64.83 | 72.92 | 77.72 | 75.24 | 81.59 | 60.29 | 69.34 |

| LSTM | 78.55 | 85.28 | 81.78 | 85.45 | 82.50 | 83.95 | 76.93 | 89.64 | 82.80 | 89.41 | 78.13 | 83.39 | 73.52 | 79.67 | 76.47 | 86.15 | 83.27 | 84.69 |

| CL-MPPCA | 82.36 | 76.07 | 79.09 | 73.71 | 88.54 | 80.44 | 56.02 | 99.93 | 71.80 | 86.13 | 63.16 | 72.88 | 73.12 | 78.71 | 75.81 | 76.78 | 81.50 | 79.07 |

| ITAD | 86.22 | 73.71 | 79.48 | 69.44 | 84.09 | 76.07 | 72.80 | 64.02 | 68.13 | 82.42 | 66.89 | 73.85 | 73.87 | 75.43 | 74.64 | 63.13 | 52.08 | 57.08 |

| LSTM-VAE | 75.76 | 90.08 | 82.30 | 85.49 | 79.94 | 82.62 | 73.62 | 89.92 | 80.96 | 92.20 | 67.75 | 78.10 | 75.10 | 79.05 | 77.02 | 76.00 | 89.50 | 82.20 |

| BeatGAN | 72.90 | 84.09 | 78.10 | 89.75 | 85.42 | 87.53 | 90.30 | 93.84 | 92.04 | 92.38 | 55.85 | 69.61 | 76.64 | 80.18 | 78.37 | 64.01 | 87.46 | 73.92 |

| OmniAnomaly | 83.68 | 86.82 | 85.22 | 89.02 | 86.37 | 87.67 | 88.39 | 74.46 | 80.83 | 92.49 | 81.99 | 86.92 | 79.47 | 82.37 | 80.90 | 81.42 | 84.30 | 82.83 |

| InterFusion | 87.02 | 85.43 | 86.22 | 81.28 | 92.70 | 86.62 | 83.61 | 83.45 | 83.52 | 89.77 | 88.52 | 89.14 | 78.21 | 85.34 | 81.62 | 80.59 | 85.58 | 83.01 |

| THOC | 79.76 | 90.95 | 84.99 | 88.45 | 90.97 | 89.69 | 88.14 | 90.99 | 89.54 | 92.06 | 89.34 | 90.68 | 80.97 | 83.45 | 82.19 | 83.94 | 86.36 | 85.13 |

| GmVRNN | 96.07 | 91.23 | 93.56 | 90.81 | 92.10 | 91.41 | 95.62 | 98.36 | 96.97 | 96.51 | 94.54 | 95.51 | 83.80 | 87.67 | 85.58 | 90.11 | 94.69 | 92.34 |

| Anomaly Transformer | 89.40 | 95.45 | 92.33 | 92.09 | 95.15 | 93.59 | 96.91 | 98.90 | 97.89 | 94.13 | 99.40 | 96.69 | 82.13 | 86.31 | 84.16 | 91.55 | 96.73 | 94.07 |

| TranAD | 92.62 | 99.74 | 96.05 | 90.38 | 99.99 | 94.94 | 95.36 | 98.65 | 96.97 | 80.43 | 99.99 | 89.15 | 82.59 | 86.60 | 84.54 | 97.60 | 69.97 | 81.51 |

| Ours | 93.73 | 98.68 | 96.14 | 91.89 | 98.37 | 95.01 | 96.65 | 99.39 | 98.00 | 94.26 | 99.28 | 96.70 | 84.58 | 88.54 | 86.51 | 94.08 | 97.58 | 95.79 |

| Methods | Dataset | SMD | MSL | SMAP | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Number | 1 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 200 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 200 | |

| Metric | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | F1 | |

| Random Initialization | DAGMM | 43.11 | 44.16 | 44.87 | 44.02 | 63.38 | 50.66 | 50.52 | 51.36 | 51.45 | 65.15 | 53.38 | 53.26 | 54.89 | 60.16 | 65.68 |

| MMPCACD | 54.40 | 55.49 | 55.63 | 56.21 | 67.05 | 51.31 | 51.94 | 52.57 | 52.75 | 65.08 | 52.90 | 52.76 | 56.01 | 61.05 | 65.87 | |

| VAR | 54.40 | 54.29 | 54.65 | 55.75 | 66.39 | 53.99 | 53.02 | 53.60 | 53.82 | 66.31 | 55.29 | 55.18 | 56.36 | 62.90 | 66.00 | |

| LSTM | 56.17 | 56.68 | 56.87 | 56.89 | 67.76 | 60.58 | 60.62 | 61.29 | 61.37 | 69.59 | 56.73 | 56.57 | 57.58 | 61.98 | 67.74 | |

| CL-MPPCA | 57.00 | 57.05 | 57.17 | 57.87 | 68.14 | 59.67 | 59.34 | 60.30 | 60.69 | 70.08 | 58.76 | 58.43 | 58.28 | 65.55 | 68.36 | |

| ITAD | 56.36 | 56.08 | 56.51 | 56.90 | 66.93 | 62.98 | 62.71 | 63.17 | 63.35 | 69.50 | 62.74 | 62.71 | 63.85 | 66.95 | 68.85 | |

| LSTM-VAE | 58.38 | 58.74 | 58.08 | 59.48 | 69.15 | 61.89 | 61.10 | 61.90 | 62.16 | 71.05 | 61.61 | 61.23 | 62.19 | 67.41 | 69.16 | |

| BeatGAN | 61.30 | 61.18 | 61.04 | 62.02 | 68.73 | 63.09 | 63.57 | 64.23 | 65.88 | 74.30 | 61.49 | 61.18 | 61.72 | 66.89 | 71.10 | |

| OmniAnomaly | 64.29 | 65.15 | 63.53 | 62.05 | 68.31 | 64.36 | 64.43 | 65.14 | 68.77 | 73.80 | 63.13 | 65.55 | 65.61 | 68.72 | 70.27 | |

| InterFusion | 63.68 | 62.66 | 62.37 | 62.28 | 69.83 | 63.60 | 63.56 | 64.32 | 65.83 | 62.16 | 63.50 | 63.34 | 63.95 | 68.79 | 72.44 | |

| THOC | 64.41 | 63.47 | 63.12 | 63.94 | 71.01 | 64.33 | 64.13 | 64.22 | 66.00 | 74.65 | 62.24 | 62.46 | 63.92 | 70.66 | 75.22 | |

| Anomaly Transformer | 64.24 | 65.09 | 71.85 | 76.98 | 81.11 | 65.16 | 64.99 | 68.52 | 70.46 | 77.02 | 63.82 | 66.72 | 67.34 | 71.45 | 78.88 | |

| TranAD | 66.28 | 67.58 | 72.26 | 77.01 | 81.54 | 67.66 | 66.26 | 69.83 | 72.74 | 78.94 | 64.27 | 67.24 | 68.73 | 72.65 | 80.78 | |

| Pretraining with History MTSs | DAGMM | 72.08 | 72.55 | 72.82 | 73.04 | 73.39 | 68.47 | 67.71 | 68.28 | 68.68 | 69.17 | 70.81 | 71.04 | 71.66 | 71.94 | 72.07 |

| MMPCACD | 73.15 | 72.90 | 73.90 | 73.31 | 73.11 | 69.99 | 69.68 | 70.34 | 70.57 | 70.04 | 72.95 | 73.01 | 73.05 | 73.25 | 73.44 | |

| VAR | 74.54 | 75.01 | 74.11 | 74.78 | 74.10 | 70.88 | 71.14 | 71.09 | 71.67 | 71.96 | 71.87 | 72.16 | 72.67 | 72.38 | 72.56 | |

| LSTM | 73.77 | 73.61 | 73.78 | 73.92 | 73.70 | 71.79 | 71.32 | 72.01 | 72.17 | 71.94 | 74.07 | 74.57 | 74.44 | 73.76 | 74.81 | |

| CL-MPPCA | 75.23 | 75.18 | 74.92 | 75.31 | 75.87 | 73.57 | 72.99 | 73.51 | 73.36 | 73.12 | 76.50 | 75.96 | 76.15 | 76.74 | 76.64 | |

| ITAD | 77.03 | 76.85 | 77.76 | 77.67 | 76.99 | 77.08 | 77.00 | 77.49 | 77.18 | 77.64 | 78.80 | 78.89 | 79.31 | 78.82 | 79.34 | |

| LSTM-VAE | 80.65 | 80.73 | 80.13 | 81.68 | 81.51 | 76.19 | 76.31 | 76.47 | 76.20 | 77.02 | 77.92 | 77.83 | 77.96 | 78.19 | 78.50 | |

| BeatGAN | 82.90 | 83.02 | 83.08 | 82.93 | 82.57 | 79.67 | 79.66 | 80.56 | 80.21 | 80.84 | 81.66 | 81.61 | 82.12 | 82.50 | 82.36 | |

| OmniAnomaly | 85.40 | 85.42 | 85.78 | 86.19 | 85.83 | 81.12 | 80.58 | 82.13 | 81.86 | 81.64 | 84.28 | 84.71 | 84.61 | 84.97 | 85.49 | |

| InterFusion | 84.60 | 84.73 | 84.74 | 84.85 | 85.09 | 82.09 | 81.87 | 82.28 | 82.46 | 83.00 | 86.70 | 86.80 | 87.26 | 87.27 | 87.12 | |

| THOC | 86.01 | 86.05 | 86.24 | 86.62 | 86.54 | 81.56 | 81.55 | 81.38 | 82.73 | 82.86 | 88.95 | 89.28 | 88.92 | 88.54 | 88.95 | |

| Anomaly Transformer | 91.58 | 91.92 | 91.46 | 91.78 | 91.69 | 80.65 | 82.87 | 82.15 | 83.55 | 84.01 | 93.32 | 93.89 | 93.51 | 94.01 | 94.11 | |

| TranAD | 91.96 | 91.69 | 91.57 | 91.87 | 91.94 | 80.85 | 81.44 | 82.42 | 84.08 | 84.12 | 93.01 | 94.03 | 93.62 | 94.35 | 94.37 | |

| One-For-All | GmVRNN | 91.03 | 89.51 | 90.01 | 90.78 | 90.34 | 81.68 | 81.15 | 82.12 | 81.59 | 81.22 | 93.47 | 93.41 | 93.01 | 92.21 | 94.12 |

| Ours | 93.31 | 92.85 | 93.90 | 93.78 | 93.08 | 89.22 | 89.90 | 89.97 | 89.03 | 90.30 | 95.27 | 95.22 | 95.26 | 95.47 | 95.61 | |

| Methods | Average Training Times per Epoch (s) | Testing Times per Sample (s × 105) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD | MSL | SMAP | PSM | DND | SMD | MSL | SMAP | PSM | DND | |

| LSTM-VAE | 26.71 | 3.88 | 6.22 | 40.29 | 37.59 | 8.37 | 14.34 | 8.90 | 8.51 | 9.76 |

| OmniAnomaly | 276.97 | 21.31 | 27.05 | 243.24 | 230.81 | 35.08 | 67.52 | 40.39 | 40.78 | 44.82 |

| GmVRNN | 25.20 | 2.67 | 5.04 | 37.96 | 35.26 | 7.02 | 13.54 | 8.17 | 8.26 | 8.89 |

| Anomaly Transformer | 28.80 | 2.64 | 5.40 | 39.67 | 6.15 | 6.51 | 11.34 | 7.21 | 7.32 | 7.95 |

| TranAD | 43.76 | 5.57 | 10.55 | 63.58 | 60.30 | 9.17 | 17.63 | 10.49 | 10.66 | 11.71 |

| Ours | 25.28 | 2.03 | 4.97 | 36.73 | 34.84 | 5.30 | 10.07 | 6.12 | 6.16 | 6.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Hu, X.; Chen, B.; Liu, H. Meta Variational Memory Transformer for Anomaly Detection of Multivariate Time Series. Sensors 2025, 25, 7611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247611

Qin K, Li Y, Chen W, Hu X, Chen B, Liu H. Meta Variational Memory Transformer for Anomaly Detection of Multivariate Time Series. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247611

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Kun, Yuxin Li, Wenchao Chen, Xinyue Hu, Bo Chen, and Hongwei Liu. 2025. "Meta Variational Memory Transformer for Anomaly Detection of Multivariate Time Series" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247611

APA StyleQin, K., Li, Y., Chen, W., Hu, X., Chen, B., & Liu, H. (2025). Meta Variational Memory Transformer for Anomaly Detection of Multivariate Time Series. Sensors, 25(24), 7611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247611