Fault Diagnosis of Static Eccentricity in Marine Diesel Generators Using 2D Short-Time Fourier Transform of Three-Phase Currents

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

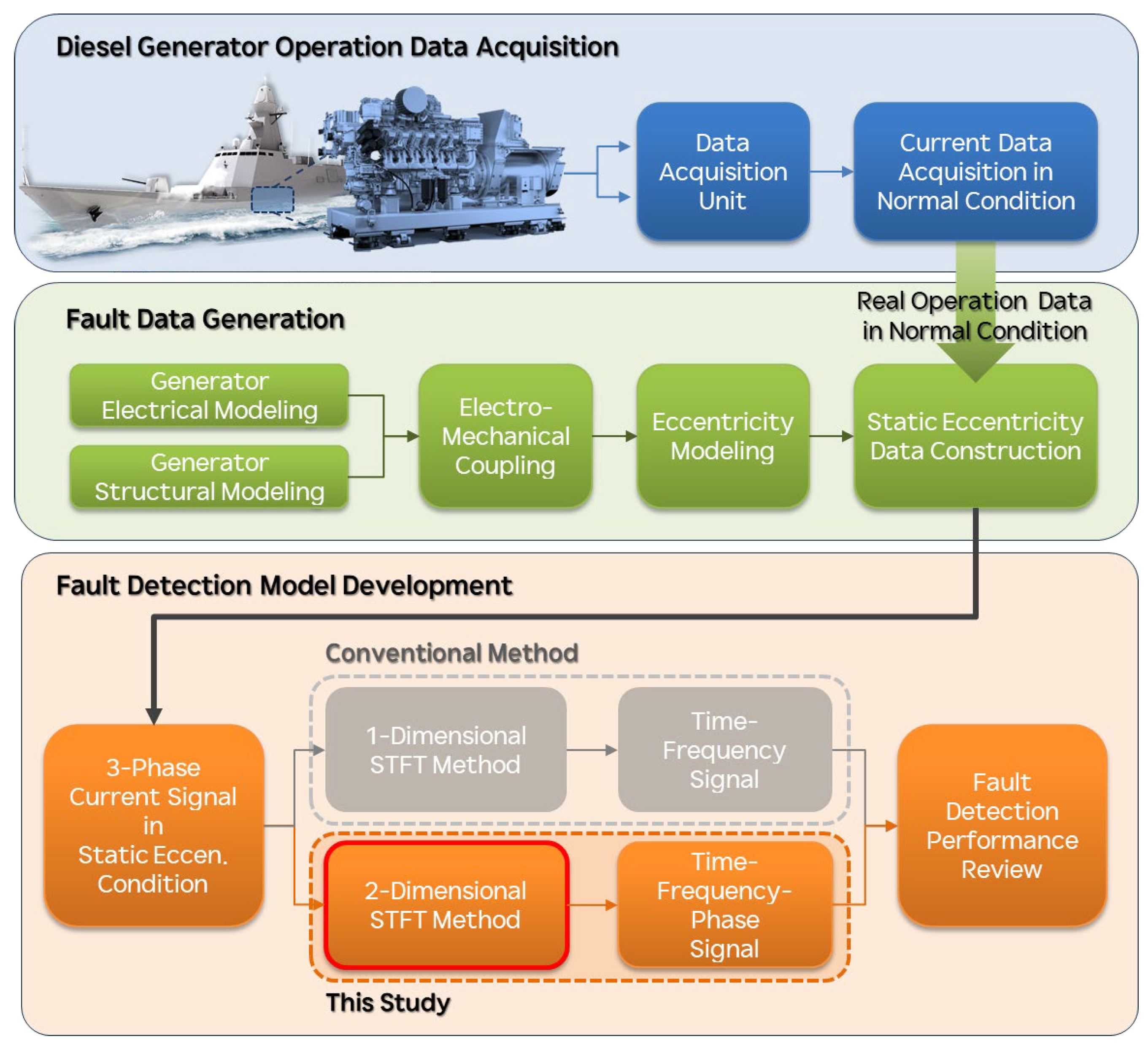

- We construct static-eccentricity fault data for a marine diesel generator by combining long-term three-phase current measurements with a physics-based electro-mechanical model, thereby generating realistic low-level fault scenarios.

- (2)

- We propose a 2D STFT formulation in which the three-phase currents are arranged into a phase–time matrix and analyzed simultaneously along the time and phase axes. This provides phase-axis spectral components that directly encode the inter-phase coupling and spatial asymmetry of the air-gap field, which are not available in conventional multi-phase MCSA or 1D STFT approaches.

- (3)

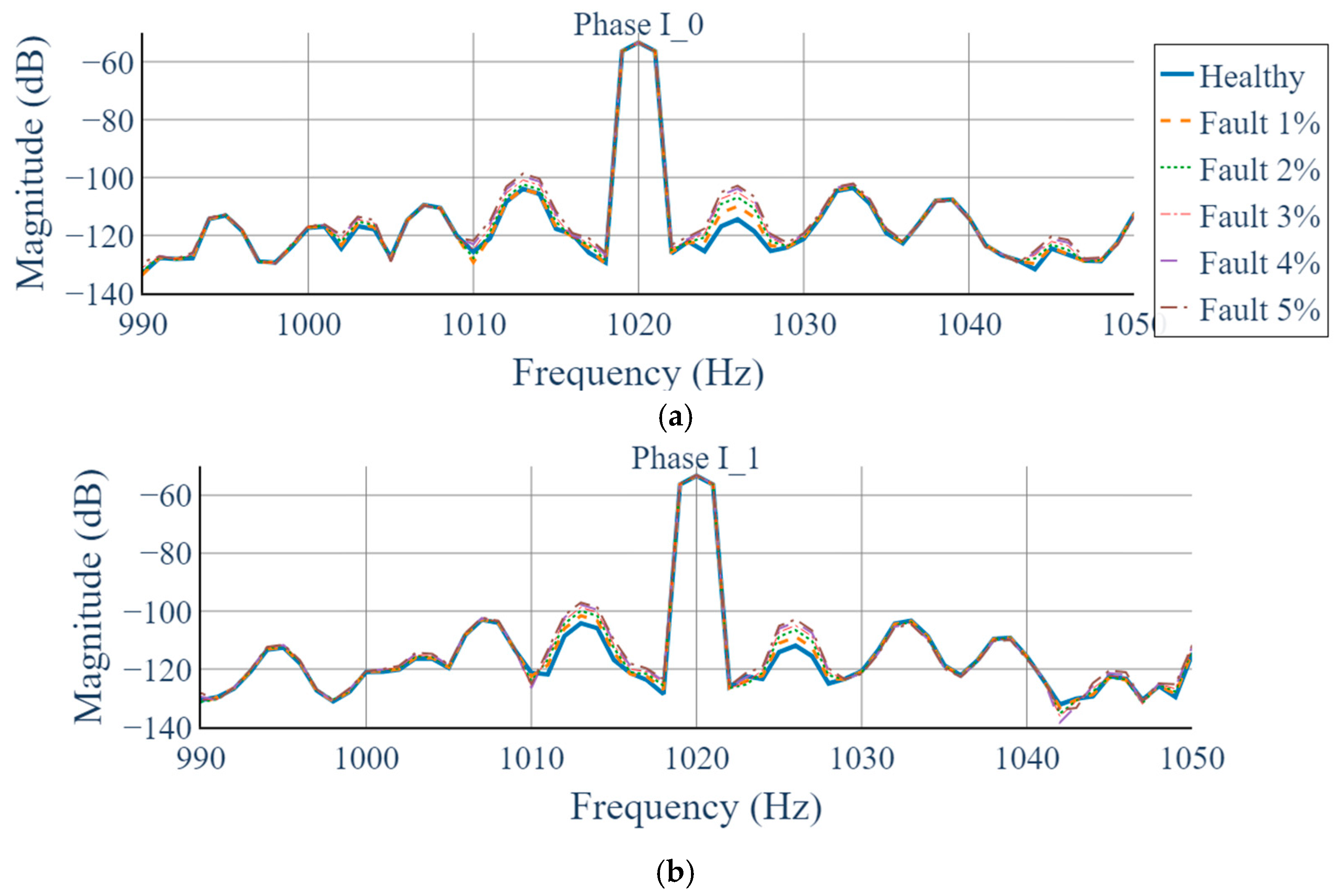

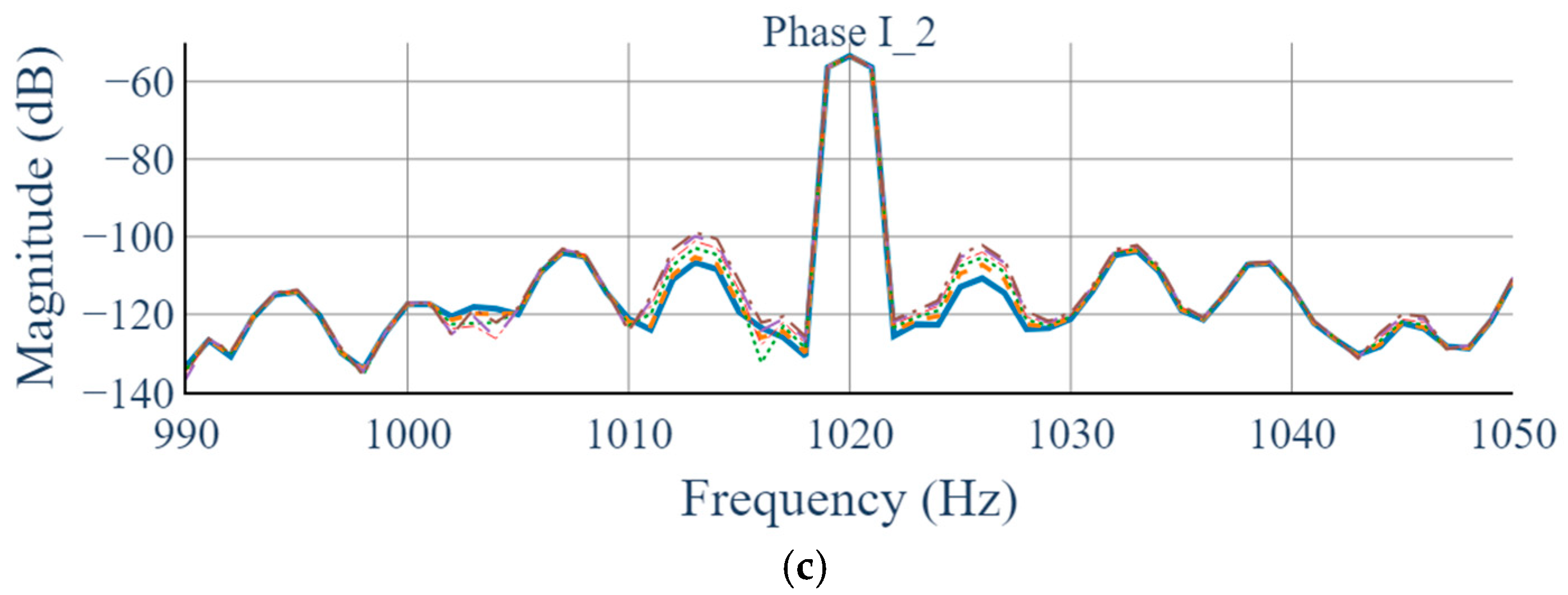

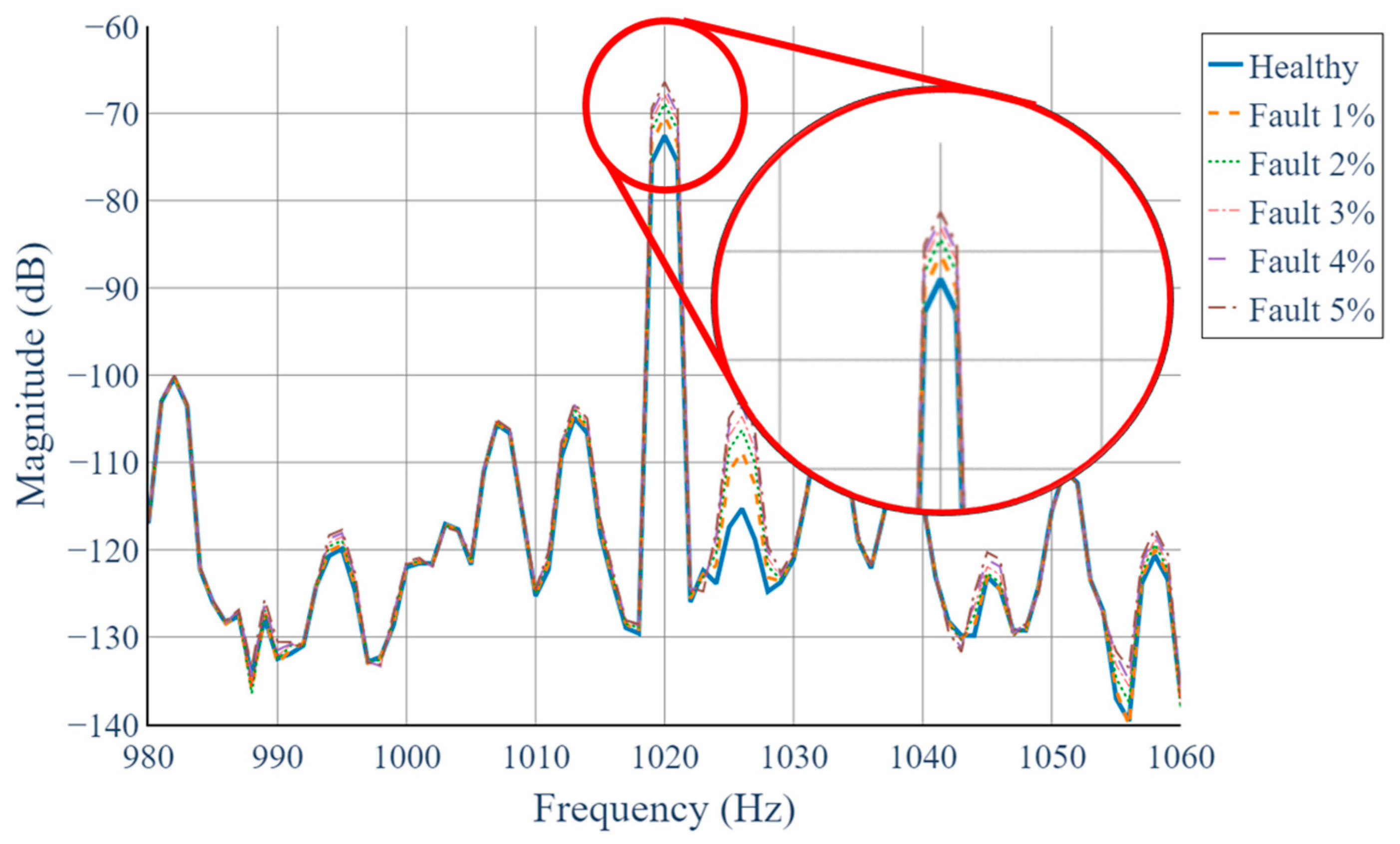

- We show that, for the target generator, the 2D STFT yields a distinct harmonic component at 1020 Hz (17th harmonic of the 60 Hz supply), whose magnitude increases monotonically from 0% to 5% static eccentricity. In contrast, conventional 1D STFT analysis of each phase exhibits negligible variation under the same conditions.

2. System Modeling for Eccentricity Fault Analysis

2.1. Electrical Modeling

2.2. Structural Modeling

2.3. Electro-Mechanical Coupling and Eccentricity Modeling

3. 2D-STFT-Based Fault Analysis Methodology

3.1. Three-Phase–Time Sequence Construction

3.2. Definition of 2D STFT

- : input 2D sequence

- : 2D window function

- : frequency components along the time and phase axes

3.3. Parameter Configuration for STFT

4. Experimental Setup and Analysis Results

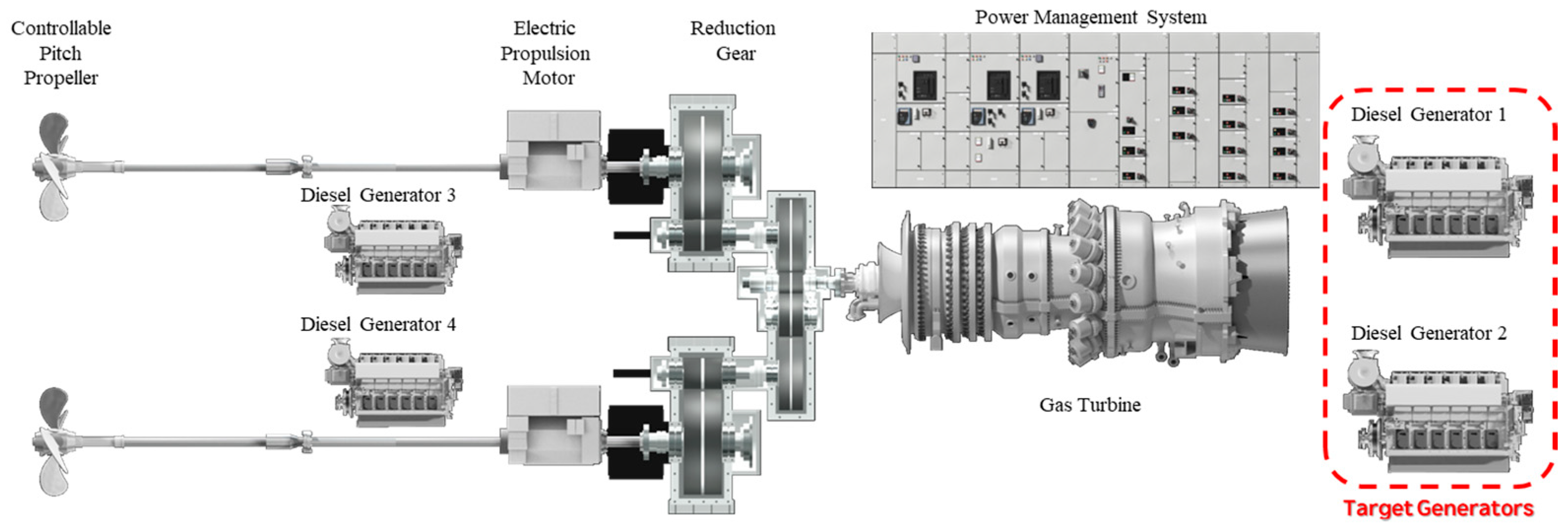

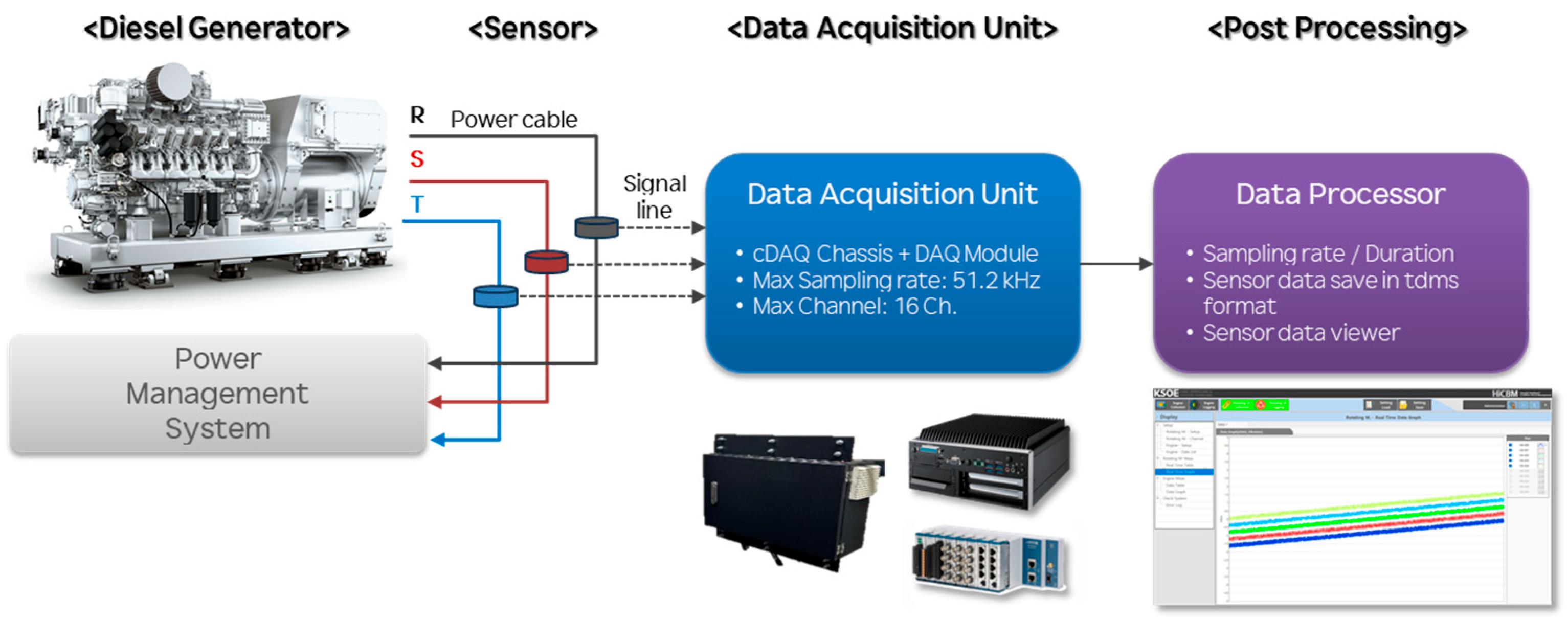

4.1. Data Acquisition and Measurement System

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Generator/Engine Model | MTU 12V 4000 series diesel generator (based on 12V 4000 G14F/DS1650) |

| Rated Output | 1650 kW at 60 Hz (three-phase) |

| Voltage | 450 V (line-to-line) |

| Frequency | 60 Hz |

| Speed | 1800 rpm |

| Cylinder Configuration | 12 V configuration, 4-stroke, turbocharged diesel engine |

| Bore Stroke | 170 mm 210 mm |

| Displacement | 57.2 L |

| Specific fuel consumption | 200 g/kWh (at 100% load, ISO 3046-1 [17]) |

| Dimensions () | 4059 mm 1810 mm 2330 mm (open power unit) |

| Dry weight | 10,654 kg (open power unit) |

4.2. Construction of Fault Data Using Real Operation Measurements

4.3. One-Dimensional STFT Analysis Results (Conventional Method)

4.4. Two-Dimensional STFT Analysis Results (Proposed Method)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. A Review of Modeling and Diagnostic Techniques for Eccentricity Fault in Electric Machines. Energies 2021, 14, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljković, D. Brief Review of Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA). 2015, pp. 356–361. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/148715 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Krichen, M.; Salah, M.; Trabelsi, R.; Mimouni, M.F. Motor Current Signature Analysis-Based Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Demagnetization Characterization and Detection. Machines 2020, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boashash, B. (Ed.) Time–Frequency Signal Analysis and Processing, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariades, C.; Xavier, V. A Review of Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Fault Diagnosis of Electric Machines. Sensors 2025, 25, 5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, S.; Quiróga, J.; Borrás, C. Motor current signature analysis and negative sequence current based stator winding short fault detection in an induction motor. Dyna 2011, 78, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, M.; Mariun, N.; Ab Kadir, M.Z.; Mohd Radzi, M.A.; Misron, N. Analysis of Rotor Asymmetry Fault in Three-Phase Line-Start Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Facta Univ. Ser. Electron. Energetics 2021, 34, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borré, A.; Seman, L.O.; Camponogara, E.; Stefenon, S.F.; Mariani, V.C.; Coelho, L.D. Machine fault detection using a hybrid CNN-LSTM attention-based model. Sensors 2023, 23, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhao, H. Active impulsive noise control using maximum correntropy with adaptive kernel size. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 87, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibaj, A.; Valavi, M.; Nejad, A.R. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection of Permanent-Magnet Offshore Wind Generators Through Electrical and Electromagnetic Measurements. Wind Energy Sci. 2024, 9, 2063–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyftakis, K.N.; Platero, C.A.; Zhang, Y.; Bernal, S. Diagnosis of Static Eccentricity in 3-Phase Synchronous Machines Using a Pseudo Zero-Sequence Current. Energies 2019, 12, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Liao, Y.; Toliyat, H.A.; El-Antably, A.; Lipo, T.A. Multiple Coupled Circuit Modeling of Induction Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1995, 31, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Shen, G.; Hu, N.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y. Coupled Electromagnetic–Dynamic Modeling and Bearing Fault Characteristics of Induction Motors Considering Unbalanced Magnetic Pull. Entropy 2022, 24, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Vergara, T.; Cano, E.; Castellanos-Domínguez, G. Multi-Channel Spectrograms for Speech Processing. In Speech and Language Processing for Human-Machine Communications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, L.; Courbebaisse, G.; Pinoli, J.-C. Continuous Frequency and Phase Spectrograms: A Study of Their 2D and 3D Capabilities and Application to Musical Signal Analysis. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2008, 9, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolls-Royce Group. MTU Solutions Marine Propulsion Products. MTU Solutions, 2025. Available online: https://www.mtu-solutions.com (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- ISO 3046-1; Reciprocating Internal Combustion Engines—Performance—Part 1: Declarations of Power, Fuel and Lubricating Oil Consumptions, and Test Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

| Parmeter | Value |

|---|---|

| Window Size | 10,417 × 3 phase |

| Overlap | 10% |

| Window Function | Hann |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Model | AT 300 |

| Current Measurement Range | 300 A (DC or AC peak) |

| Output Sensitivity | 10 mV/A |

| Resolution | ±1 mA |

| Accuracy | ±1% of reading ± 5 mA |

| Bandwidth | DC to 100 kHz (−3 dB) |

| Max Conductor Diameter | 25 mm |

| Operating Temperature | −20 °C to +65 °C |

| Ingress Protection | IP40 (jaw closed) |

| Supply Voltage | ±15 V external ± 10% |

| Dimensions () | 100 mm 65 mm 25 mm |

| Static Eccentricity | Magnitude (dB) |

|---|---|

| 0% | −72.598 |

| 1% | −70.35 |

| 2% | −68.893 |

| 3% | −67.839 |

| 4% | −67.035 |

| 5% | −66.398 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joe, B.-J.; Lee, J.-S.; Yeo, S.-J.; Cho, Y.J.; Jeon, J.-Y. Fault Diagnosis of Static Eccentricity in Marine Diesel Generators Using 2D Short-Time Fourier Transform of Three-Phase Currents. Sensors 2025, 25, 7604. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247604

Joe B-J, Lee J-S, Yeo S-J, Cho YJ, Jeon J-Y. Fault Diagnosis of Static Eccentricity in Marine Diesel Generators Using 2D Short-Time Fourier Transform of Three-Phase Currents. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7604. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247604

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoe, Beom-Jin, Jin-Sung Lee, Sang-Jae Yeo, Yong Jae Cho, and Jee-Yeon Jeon. 2025. "Fault Diagnosis of Static Eccentricity in Marine Diesel Generators Using 2D Short-Time Fourier Transform of Three-Phase Currents" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7604. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247604

APA StyleJoe, B.-J., Lee, J.-S., Yeo, S.-J., Cho, Y. J., & Jeon, J.-Y. (2025). Fault Diagnosis of Static Eccentricity in Marine Diesel Generators Using 2D Short-Time Fourier Transform of Three-Phase Currents. Sensors, 25(24), 7604. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247604