Coherent-Phase Optical Time Domain Reflectometry for Monitoring High-Temperature Superconducting Magnet Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

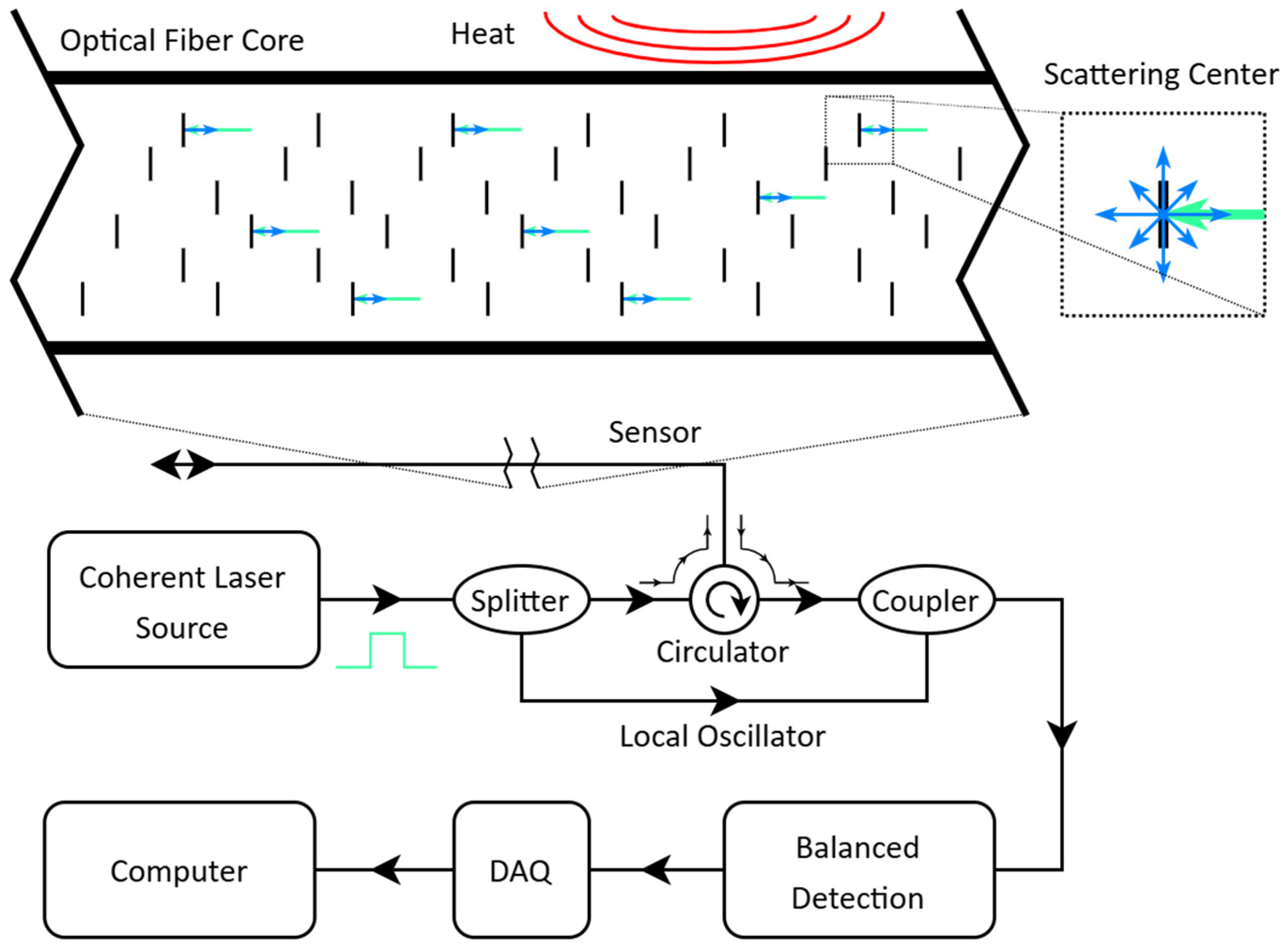

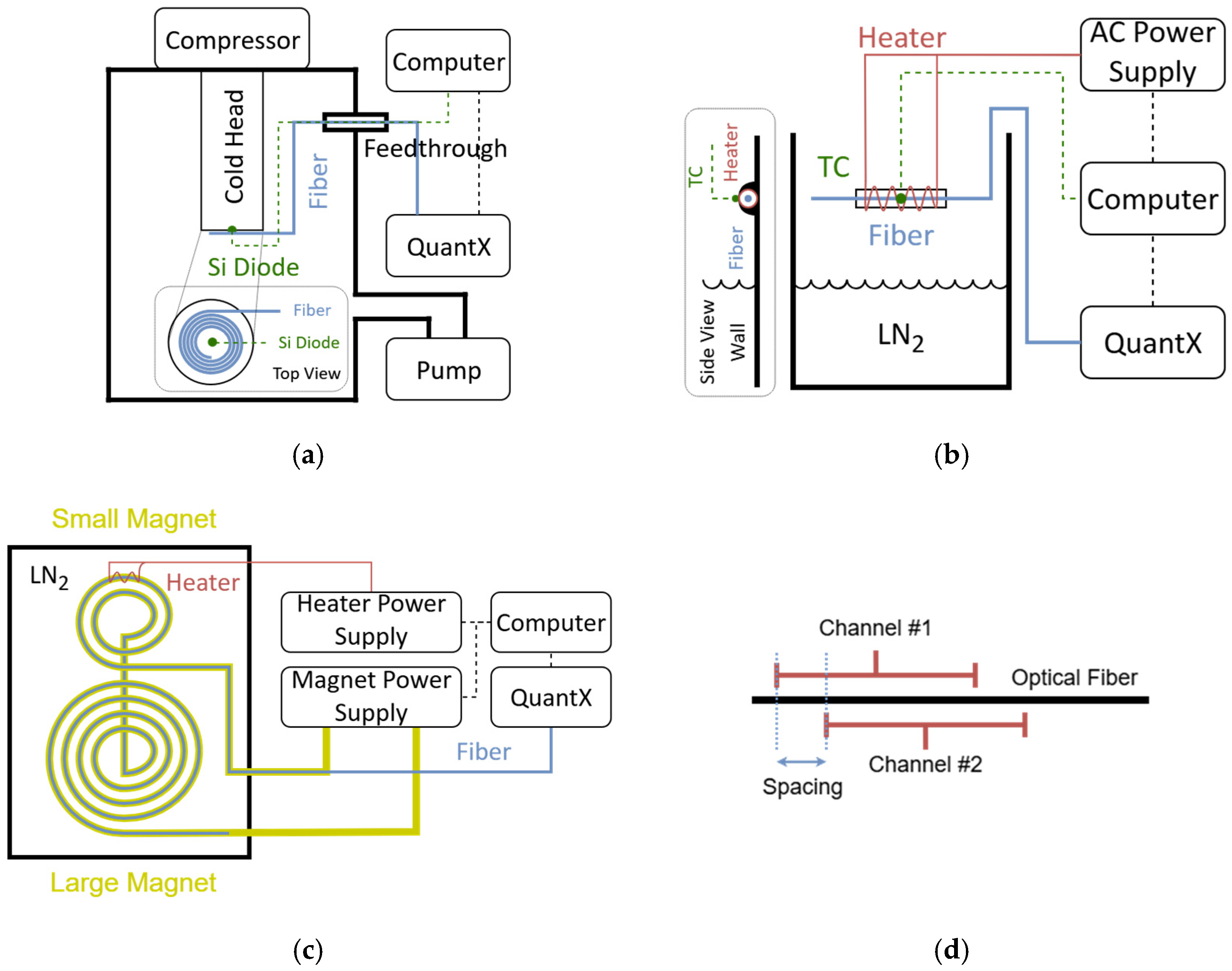

2. Materials and Methods

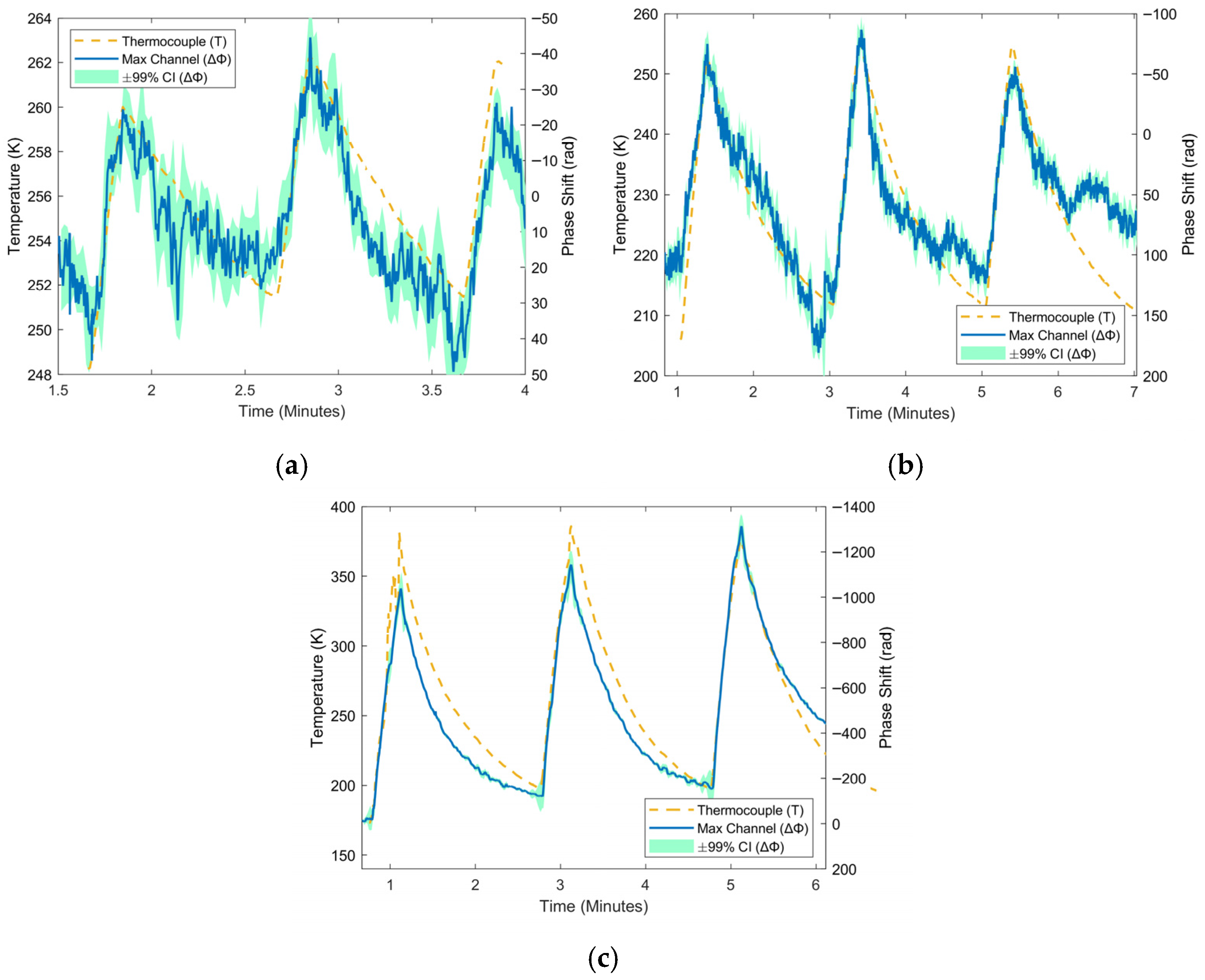

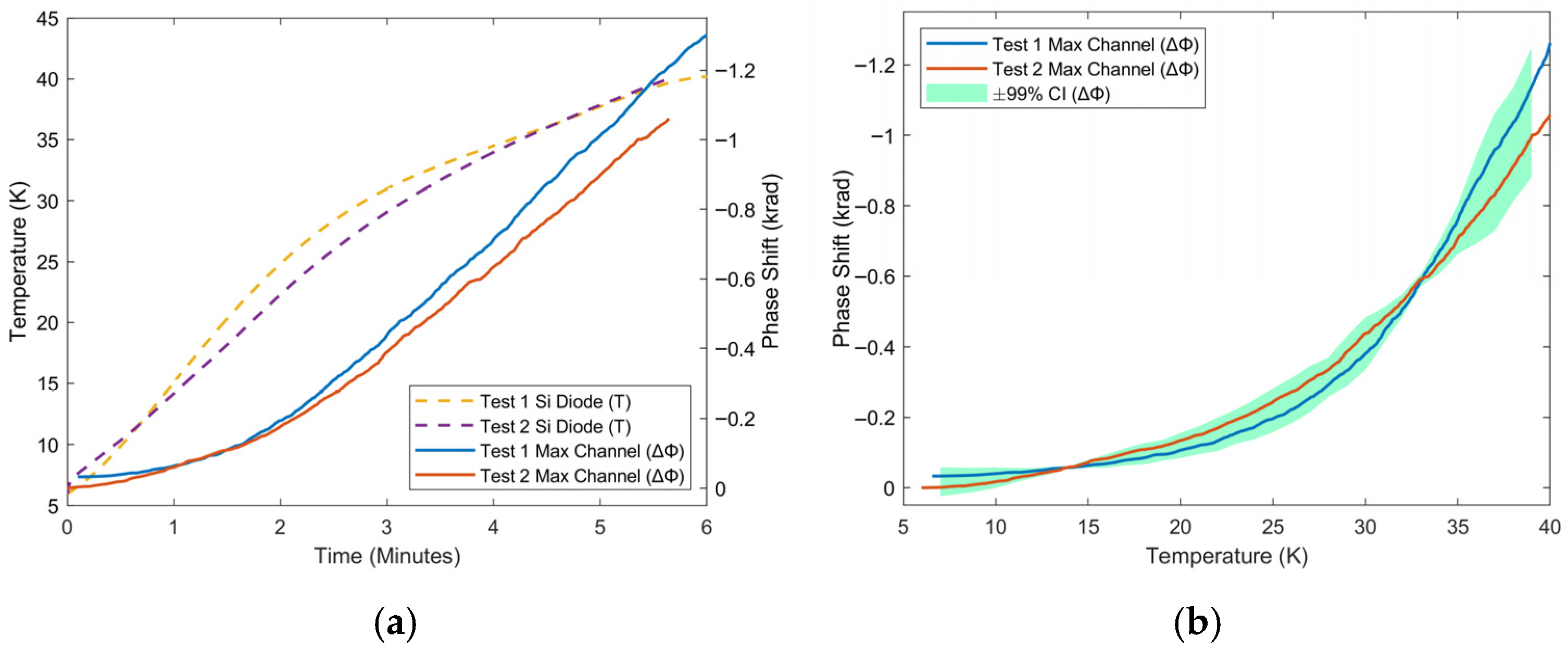

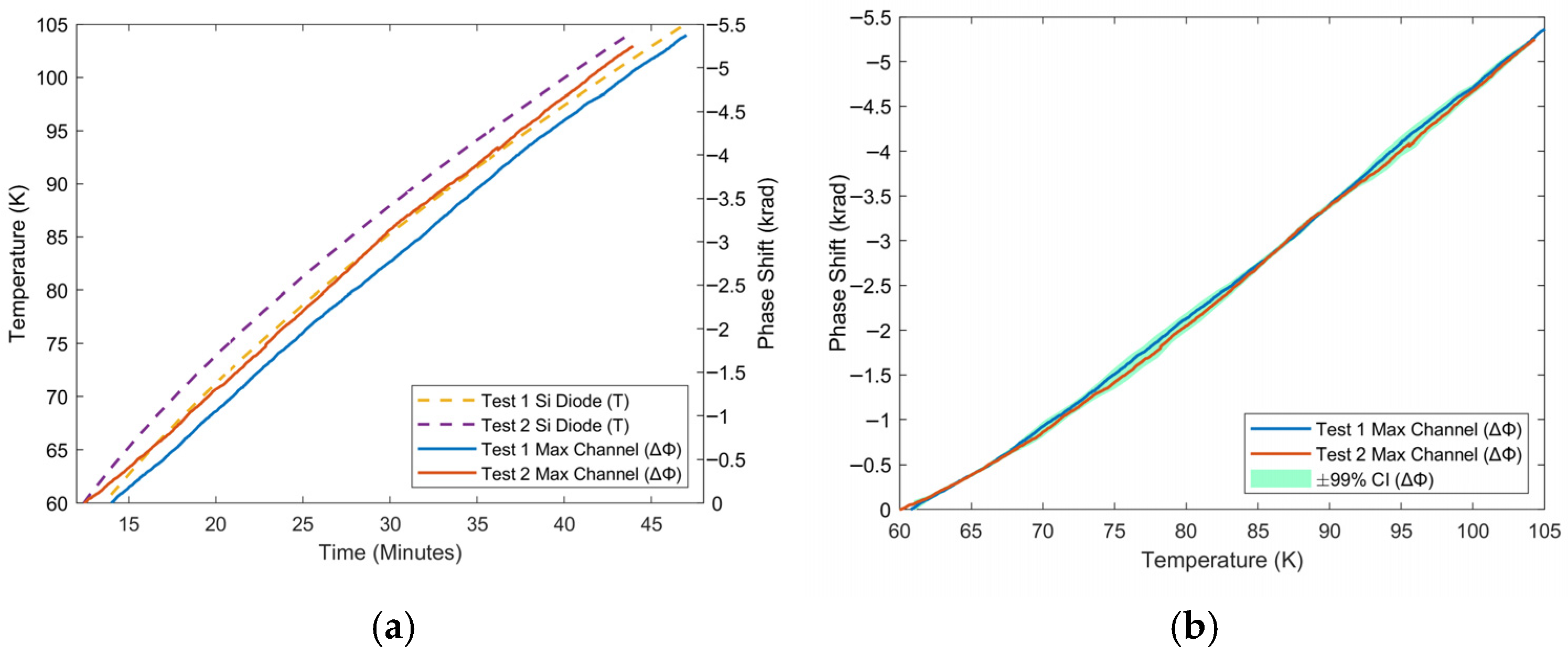

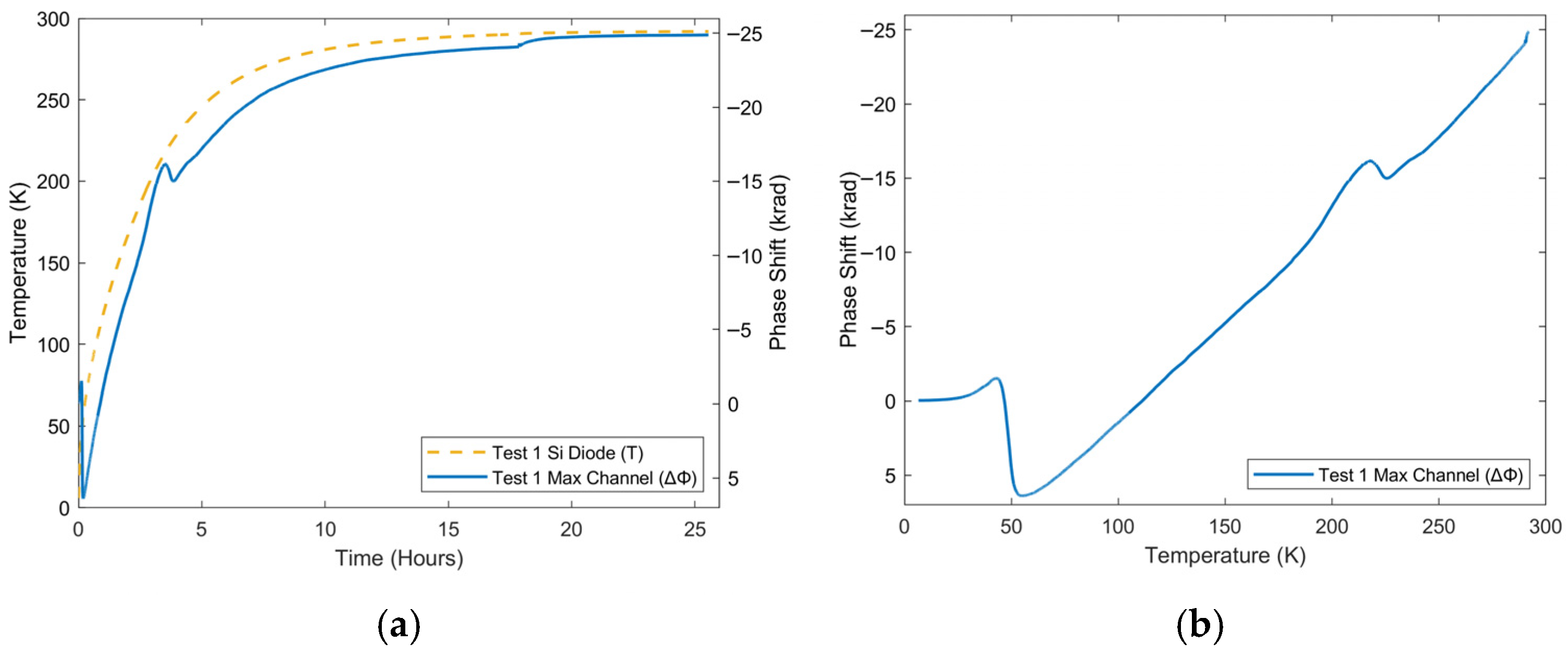

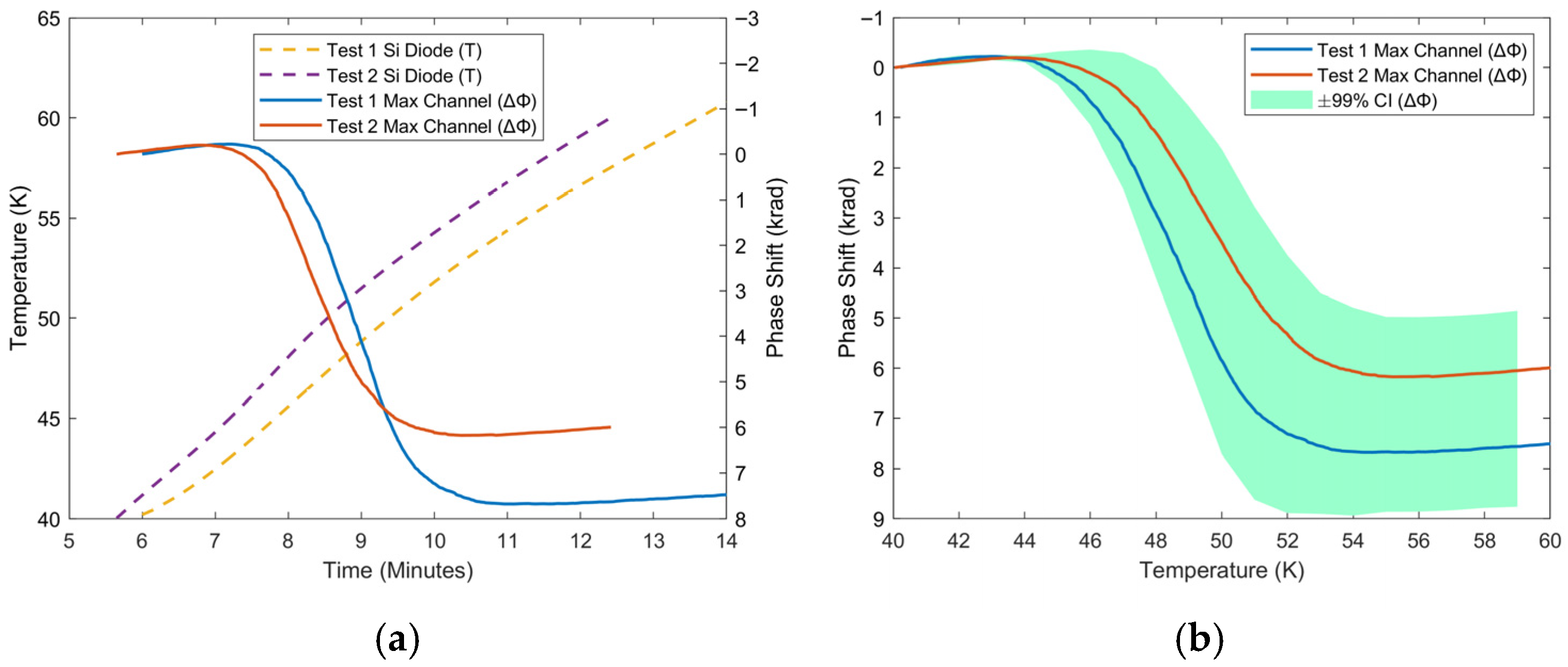

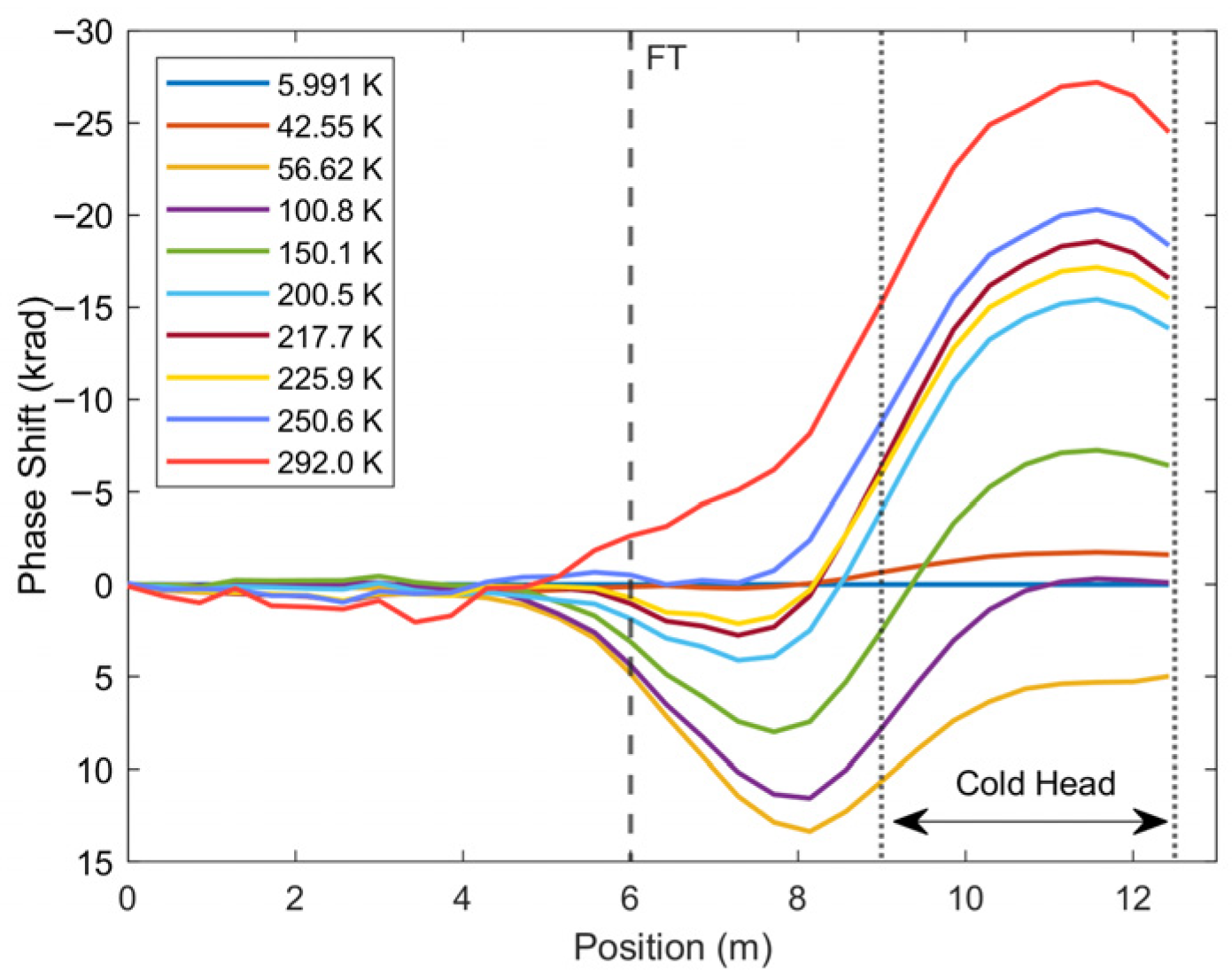

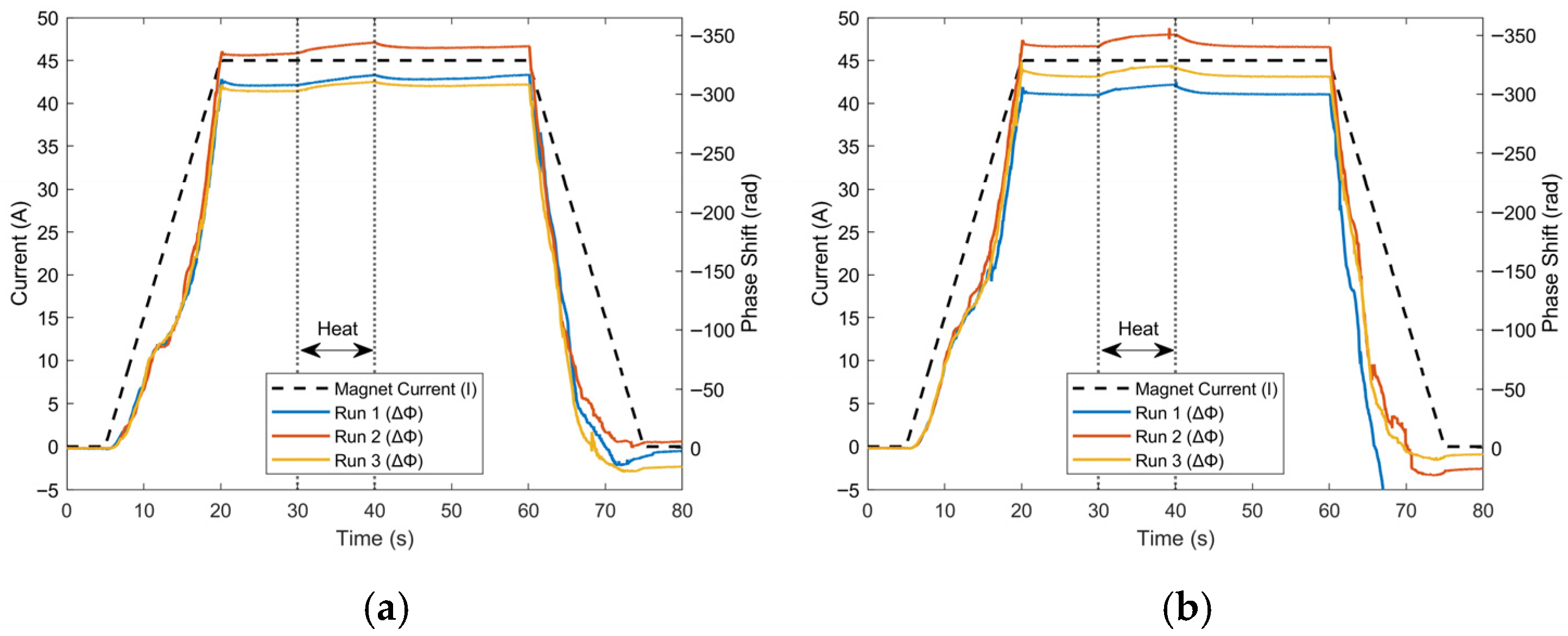

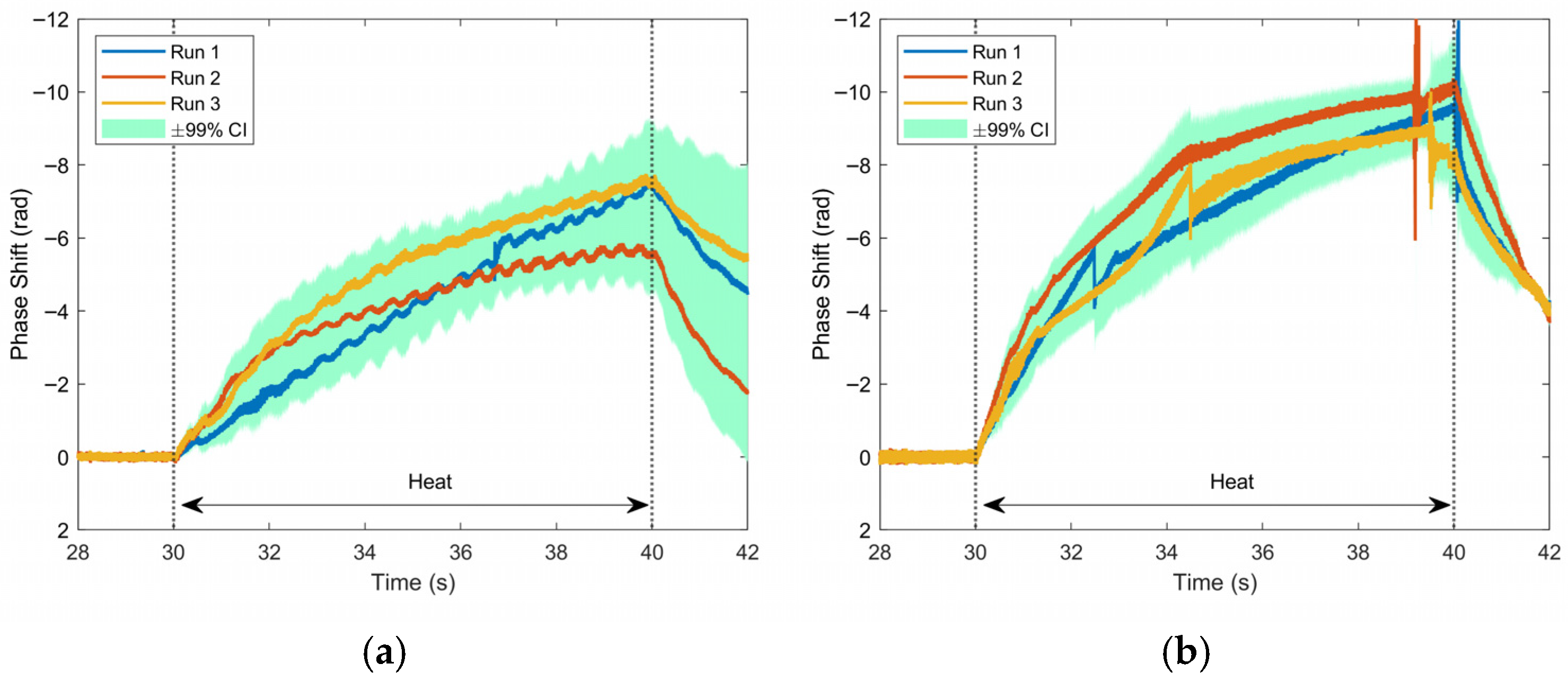

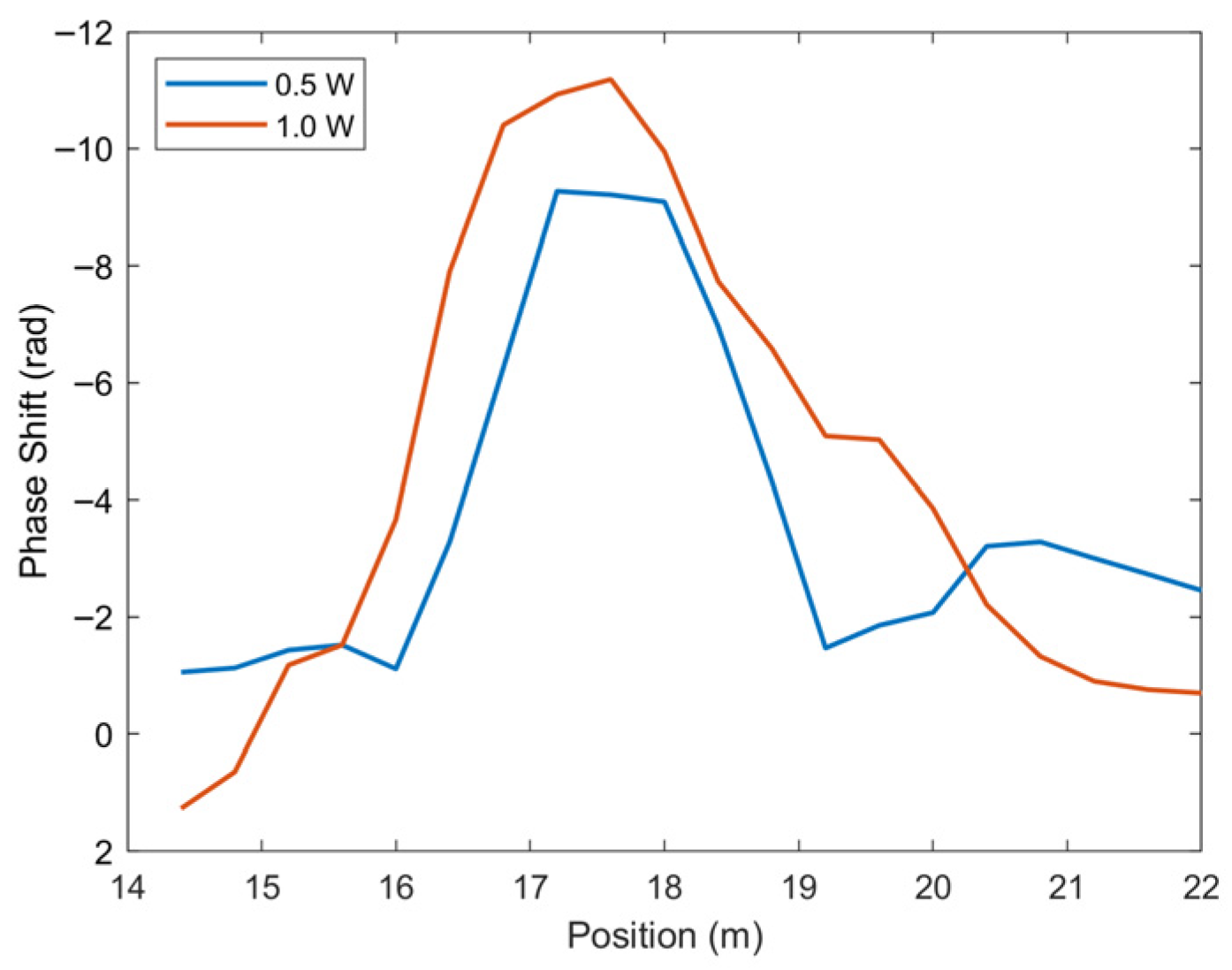

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sorbom, B.; Ball, J.; Palmer, T.; Mangiarotti, F.; Sierchio, J.; Bonoli, P.; Kasten, C.; Sutherland, D.; Barnard, H.; Haakonsen, C.; et al. ARC: A compact, high-field, fusion nuclear science facility and demonstration power plant with demountable magnets. Fusion Eng. Des. 2015, 100, 378–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molodyk, A.; Samoilenkov, S.; Markelov, A.; Degtyarenko, P.; Lee, S.; Petrykin, V.; Gaifullin, M.; Mankevich, A.; Vavilov, A.; Sorbom, B.; et al. Development and large volume production of extremely high current density YBa2Cu3O7 superconducting wires for fusion. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molodyk, A.; Larbalestier, D.C. The prospects of high-temperature superconductors. Science 2023, 380, 1220–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, N.; Zheng, J.; Vorpahl, C.; Corato, V.; Sanabria, C.; Segal, M.; Sorbom, B.N.; Slade, R.A.; Brittles, G.; Bateman, R.; et al. Superconductors for fusion: A roadmap. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, C.; Kamal, G. Faster Fusion Power from Spherical Tokamaks with High-Temperature Superconductors. In Advances in Fusion Energy Research—From Theory to Models, Algorithms, and Applications; Carpentieri, B., Shahzad, A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windridge, M. Smaller and quicker with spherical tokamaks and high-temperature superconductors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2019, 377, 20170438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurti, F.; Ishmael, S.; Flanagan, G.; Schwartz, J. Quench detection for high temperature superconductor magnets: A novel technique based on Rayleigh-backscattering interrogated optical fibers. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2016, 29, 03LT01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurti, F.; Velez, C.; Kelly, A.; Ishmael, S.; Schwartz, J. In-field strain and temperature measurements in a (RE)Ba2Cu3O7−x coil via Rayleigh-backscattering interrogated optical fibers. Smart Mater. Struct. 2023, 32, 065006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.; Krave, S.; Bossert, R.; Feher, S.; Strauss, T.; Vouris, A. Application of Distributed Fiber Optic Strain Sensors to LMQXFA Cold Mass Welding. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2023, 33, 9000705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurti, F.; Sathyamurthy, S.; Rupich, M.; Schwartz, J. Self-monitoring ‘SMART’ (RE)Ba2Cu3O7−x conductor via integrated optical fibers. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 30, 114002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurti, F.; Weiss, J.D.; van der Laan, D.C.; Schwartz, J. SMART conductor on round core (CORC®) wire via integrated optical fibers. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 035026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catellani, M.; Lo, W.; Guzman, K.N.H.; Leoschke, M.; Oliver, N.; Scurti, F. SMART Coil-to-Coil Insulation for Non-Insulated (RE)Ba2Cu3O7−x Pancake Coils. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2025, 35, 4602007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.; Scurti, F. Rayleigh-backscattering Interrogated Optical Fibers in HTS coils: Effects of AC Currents on Optical Fiber signals. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Adibi, S.A.; Breschi, M.; Caponero, M.A.; Castaldo, A.; Celentano, G.; della Corte, A.; Marchetti, M.; Masi, A.; Mazzotta, C.; et al. Fiber-Optics Quench Detection Schemes in HTS Cables for Fusion Magnets. IEEE Trans. Appl. Superconductivity 2024, 34, 4702305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Colombo, G.; De Stasio, M.; Breschi, M.; Caponero, M.A.; Celentano, G.; Marchetti, M.; Muzzi, L.; Polimadei, A.; Savoldi, L.; et al. Integration of Optical Sensors for Quench Detection in HTS Stacks and Cables for Fusion Applications. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2025, 35, 4201705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Q.; Zhu, X. Recent Progress of the Quench Detection in the EAST HTS Current Leads Using Distributed Optical Fibers. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2023, 33, 9000907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rountree, S.D.; Ohanian, O.J.; Boulanger, A.J.; Kominsky, D.; Davis, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, K.P.; Leong, A.; Zhang, J.D.; Scurti, F.D.; et al. Multi-parameter fiber optic sensing for harsh nuclear environments. In Fiber Optic Sensors and Applications XVII; Lieberman, R.A., Sanders, G.A., Scheel, I.U., Eds.; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 117390H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoschke, M.; Zilberman, S.; Lo, W.; Catellani, M.; Beck, D.; Geuther, J.; Scurti, F. Simultaneous measurement of temperature and ionizing radiation dose based on type-II FBGs inscribed in P-doped optical fibers. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Porto, Portugal, 25–30 May 2025; Santos, J.L., Sainz, M.L.-A., Sun, T., Eds.; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; p. 13639AR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludbrook, B.M.; Fernandez, F.S.; Ramesh, M.; Phoenix, B.; Moseley, D.A.; Schuyt, J.J.; Fernando, G.; Badcock, R.A. Resilience of Fiber-Bragg Grating Optical Sensors Under Neutron Irradiation At 77 K. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 35, 9000105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.S.; Ludbrook, B.M.; Schuyt, J.; Trompetter, B.; Moseley, D.; Haneef, S.; Badcock, R.A. Mitigation of radiation-induced attenuation of optical fibers through photobleaching: Study of power dependence at cryogenic temperatures. In Sensors and Smart Structures Technologies for Civil, Mechanical, and Aerospace Systems 2024; Glisic, B., Limongelli, M.P., Ng, C.T., Eds.; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; p. 129490A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberman, S.; Lo, W.; Guzman, K.N.H.; Van Horn, Z.; Dror, R.; Bruner, A.; Scurti, F.; Harrera, K. Near infrared radiation induced attenuation in P-doped and Al-doped optical fibers at cryogenic temperature. Opt. Contin. 2025, 4, 1411–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchevsky, M. Quench Detection and Protection for High-Temperature Superconductor Accelerator Magnets. Instruments 2021, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchevsky, M.; Gourlay, S.A. Acoustic thermometry for detecting quenches in superconducting coils and conductor stacks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 012601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchevsky, M.; Hershkovitz, E.; Wang, X.; Gourlay, S.A.; Prestemon, S. Quench Detection for High-Temperature Superconductor Conductors Using Acoustic Thermometry. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2018, 28, 4703105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchevsky, M.; Hafalia, A.R.; Cheng, D.; Prestemon, S.; Sabbi, G.; Bajas, H.; Chlachidze, G. Axial-Field Magnetic Quench Antenna for the Superconducting Accelerator Magnets. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 9500605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyber, R.; Marchevsky, M.; Prestemon, S.; Weiss, J.D.; van der Laan, D.C. CORC® cable terminations with integrated Hall arrays for quench detection. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 095009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaioli, E.; Martchevskii, M.; Sabbi, G.; Shen, T.; Zhang, K. Quench Detection Utilizing Stray Capacitances. Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2018, 28, 4702805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaioli, E.; Davis, D.; Marchevsky, M.; Sabbi, G.; Shen, T.; Verweij, A.; Zhang, K. A new quench detection method for HTS magnets: Stray-capacitance change monitoring. Phys. Scr. 2019, 95, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.S.; Kwon, G.-Y.; Bang, S.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Chang, S.J.; Sohn, S.-H.; Park, K.; Shin, Y.-J. Time–Frequency-Based Insulation Diagnostic Technique of High-Temperature Superconducting Cable Systems. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 5401005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, B.; Fu, P. Research on Quench Detection Method Using Radio Frequency Wave Technology. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2019, 30, 1500405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, L.; Chiuchiolo, A.; Castaldo, B.; Bajas, H.; Galtarossa, A.; Bajko, M.; Palmieri, L. Thermal response characterization of different optical fibers samples at cryogenic temperatures. In Proceedings of the Optical Fiber Sensors Conference 2020 Special Edition, Washington, DC, USA, 8–12 June 2020; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. T3.71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiuchiolo, A.; Bajas, H.; Bajko, M.; Consales, M.; Giordano, M.; Perez, J.C.; Cusano, A. Embedded fiber Bragg grating sensors for true temperature monitoring in Nb3Sn superconducting magnets for high energy physics. In Proceedings of the Sixth European Workshop on Optical Fibre Sensors, Limerick, Ireland, 31 May–3 June 2016; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 99160A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, X.; Guan, M.; Wu, B. Strain Responses of Superconducting Magnets Based on Embedded Polymer-FBG and Cryogenic Resistance Strain Gauge Measurements. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2018, 29, 8400207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisser, M.; Huang, X.; Moseley, D.A.; Bumby, C.; Badcock, R.A. Evaluation of continuous fiber Bragg grating and signal processing method for hotspot detection at cryogenic temperatures. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2022, 35, 054005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Chen, G.; Long, J.; Ren, L.; Zhou, K.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Tang, Y. Characterization of a Raman-based distributed fiber optical temperature sensor in liquid nitrogen. Superconductivity 2022, 4, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crickmore, R.; Godfrey, A.; Minto, C. Temperature and Strain Separation from a Distributed Rayleigh System; European Association of Geoscientists and Engineers: Bunnik, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 2020, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.; Minto, C.; Crickmore, R.; Godfrey, A.; Purnell, B.; Chambers, J.; Dashwood, B.; Gunn, D.; Jones, L.; Meldrum, P.; et al. Distributed Rayleigh Sensing for Slope Stability Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 55th U.S. Rock Mechanics-Geomechanics Symposium, Virtual, 18–25 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, P.; Crickmore, R.; Godfrey, A.; Minto, C.; Purnell, B.; Gunn, D.; Dashwood, B.; Chambers, J.; Watlet, A.; Whiteley, J. Ground Condition Monitoring of a Landslide Using Distributed Rayleigh Sensing; European Association of Geoscientists and Engineers: Bunnik, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 2021, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z. Seismic Noise Interferometry Reveals Transverse Drainage Configuration Beneath the Surging Bering Glacier. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 4747–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrenbach, M.; Cole, S.; Ridge, A.; Boone, K.; Kahn, D.; Rich, J.; Silver, K.; Langton, D. Fiber-optic distributed acoustic sensing of microseismicity, strain and temperature during hydraulic fracturing. Geophysics 2019, 84, D11–D23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Q. Optical Fiber Distributed Acoustic Sensors: A Review. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 39, 3671–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, G.; Masi, A.; Breschi, M.; Caponero, M.A.; Celentano, G.; Marchetti, M.; Muzzi, L.; Polimadei, A.; Savoldi, L.; Viarengo, S.; et al. Comparative Study on Distributed Fiber Optic–Based Quench Detection Schemes for HTS Cables for Fusion Magnets. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2025, 35, 4201405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, S.; Kuhnhenn, J.; Gusarov, A.; Morana, A.; Paillet, P.; Robin, T.; Weninger, L.; Fricano, F.; Roche, M.; Campanella, C.; et al. Overview of Radiation Effects on Silica-Based Optical Fibers and Fiber Sensors. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2024, 72, 982–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morana, A.; Roche, M.; Campanella, C.; Mélin, G.; Robin, T.; Marin, E.; Boukenter, A.; Ouerdane, Y.; Girard, S. Temperature Dependence of Radiation-Induced Attenuation of a Fluorine-Doped Single-Mode Optical Fiber at Infrared Wavelengths. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2023, 70, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Newkirk, A.; Lo, W.; Leoschke, M.; Catellani, M.; Reilly, M.; Lopez, J.E.A.; Correa, R.A.; Schülzgen, A.; Zilberman, S.; Scurti, F. Radiation Hardness Evaluation of Anti-Resonant Hollow Core Fibers for Extreme Environments. In Proceedings of the Advanced Photonics Congress 2024, Québec City, QC, Canada, 28 July–1 August 2024; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; p. JTh4A.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.S.; Ludbrook, B.M.; Phoenix, B.; Ramesh, M.; Schuyt, J.; Moseley, D.A.; Conroy, M.; Price, T.; Fernando, G.F.; Badcock, R.A. Photobleaching of Neutron Radiation Induced Attenuation of Optical Fibers at Liquid Nitrogen Temperature. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2025, 72, 2145–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heater Power (W) | Temp. Change (K) | Phase Change (rad) | SNR (dB) | Temp. Sens. (rad/K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 10 (248) | 70 | 20.7 | 7.0 |

| 1.0 | 35 (208) | 200 | 17.3 | 5.7 |

| 5.0 | 170 (173) | 900 | 36.9 | 5.3 |

| Heater Power (W) | Phase Change (rad) | SNR (dB) | Power Sens. (rad/W) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 4 | 26.5 | 8.0 |

| 1.0 | 6 | 27.2 | 6.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leoschke, M.; Lo, W.; Yartsev, V.; Rountree, S.D.; Cole, S.; Scurti, F. Coherent-Phase Optical Time Domain Reflectometry for Monitoring High-Temperature Superconducting Magnet Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 7368. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237368

Leoschke M, Lo W, Yartsev V, Rountree SD, Cole S, Scurti F. Coherent-Phase Optical Time Domain Reflectometry for Monitoring High-Temperature Superconducting Magnet Systems. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7368. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237368

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeoschke, Matthew, William Lo, Victor Yartsev, Steven Derek Rountree, Steve Cole, and Federico Scurti. 2025. "Coherent-Phase Optical Time Domain Reflectometry for Monitoring High-Temperature Superconducting Magnet Systems" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7368. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237368

APA StyleLeoschke, M., Lo, W., Yartsev, V., Rountree, S. D., Cole, S., & Scurti, F. (2025). Coherent-Phase Optical Time Domain Reflectometry for Monitoring High-Temperature Superconducting Magnet Systems. Sensors, 25(23), 7368. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237368