A Short-Pulse Indirect ToF Imager Using Six-Tap Pixel with a Backside-Illuminated Structure for High-Speed Demodulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Six-Tap Pixel Design and Short-Pulse iToF Operation

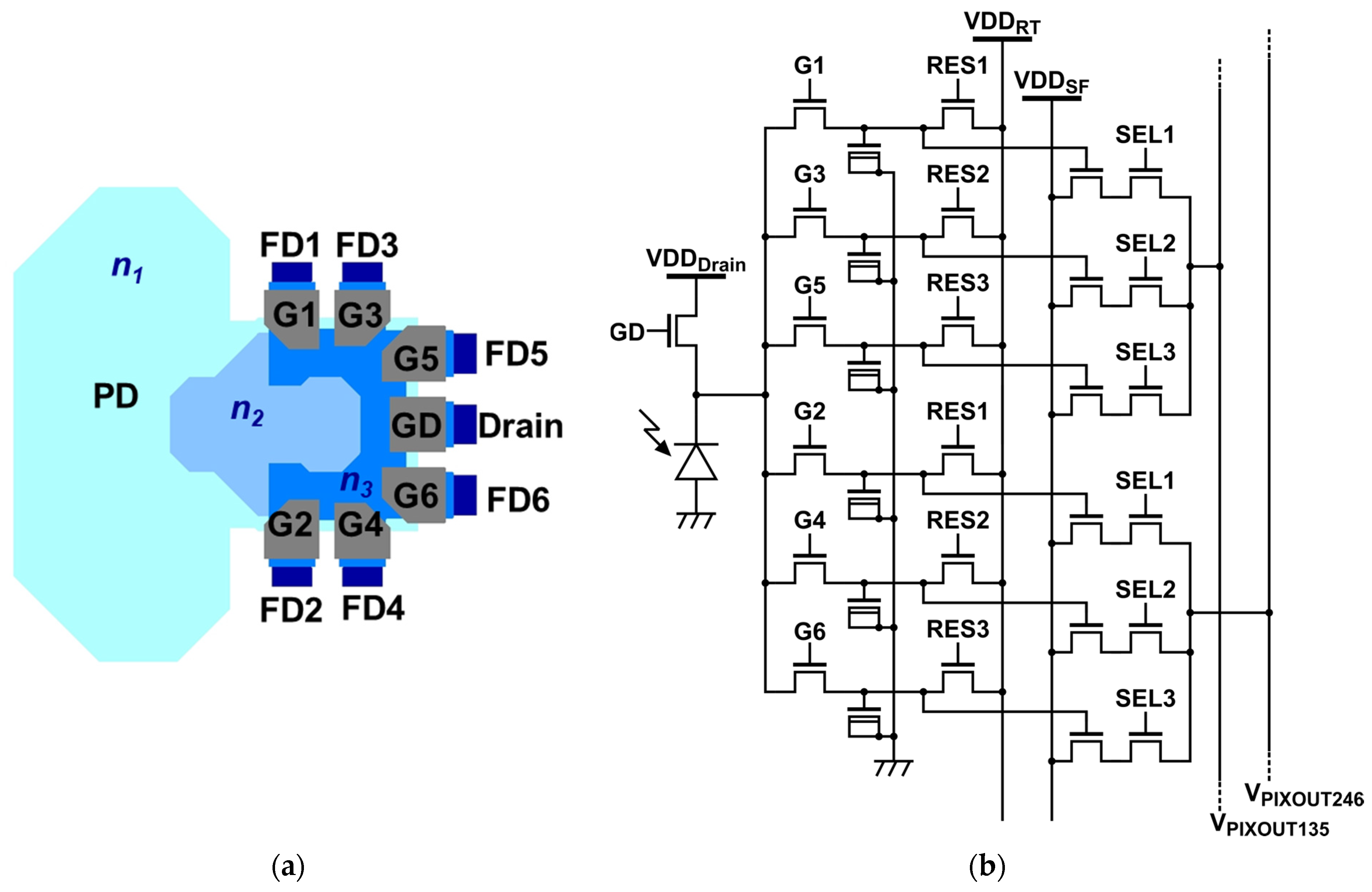

2.1. Pixel Layout and Readout

2.2. Charge-Transfer Simulations

2.3. Two-Subframe Short-Pulse Gating

3. Measurement Results

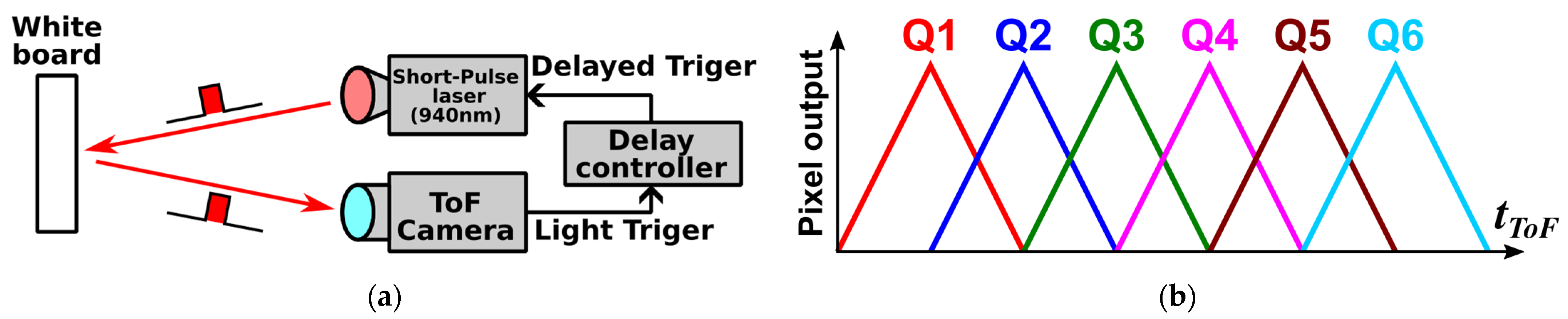

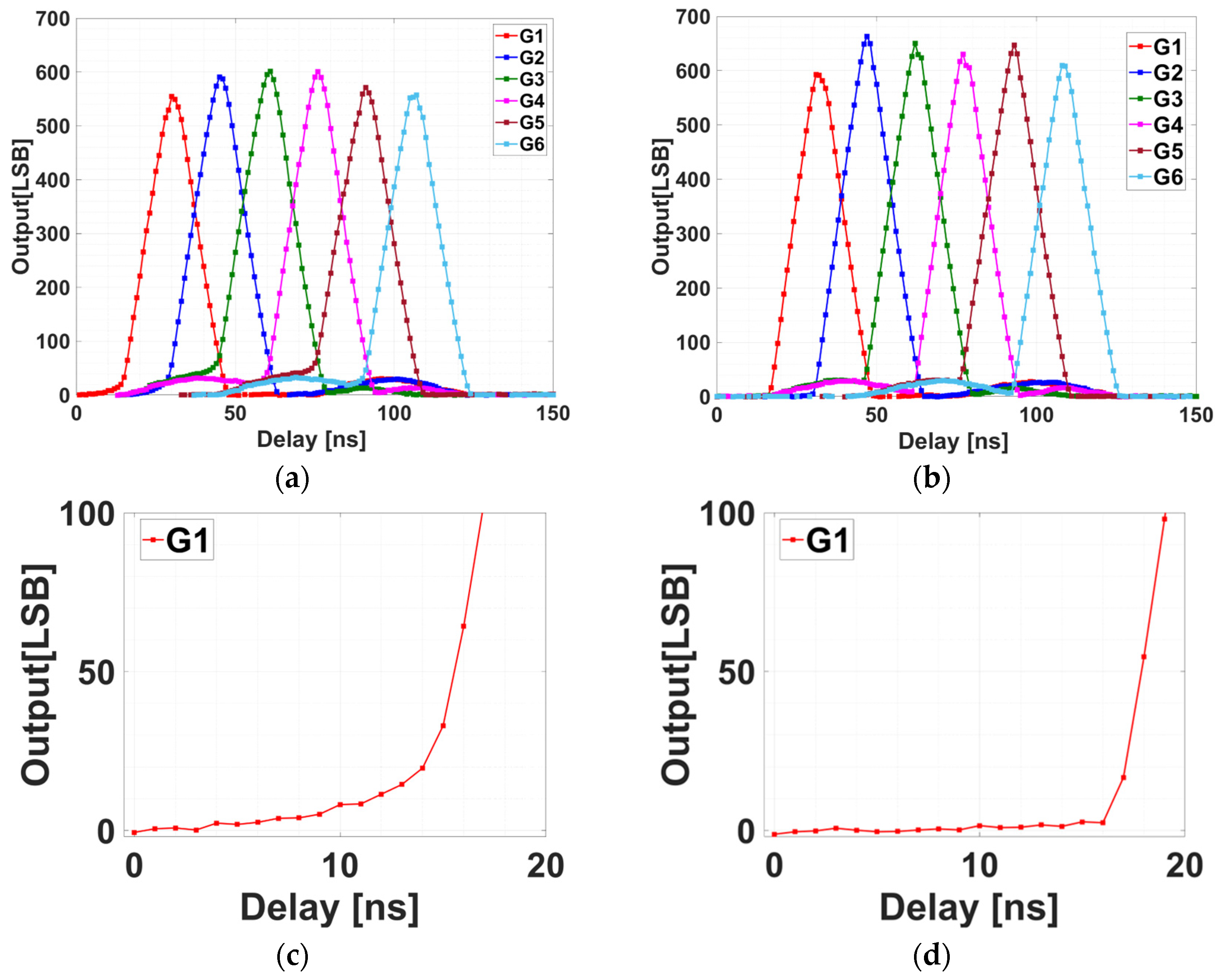

3.1. Delay-Sweep Measurement

3.2. Impulse-Response Measurement

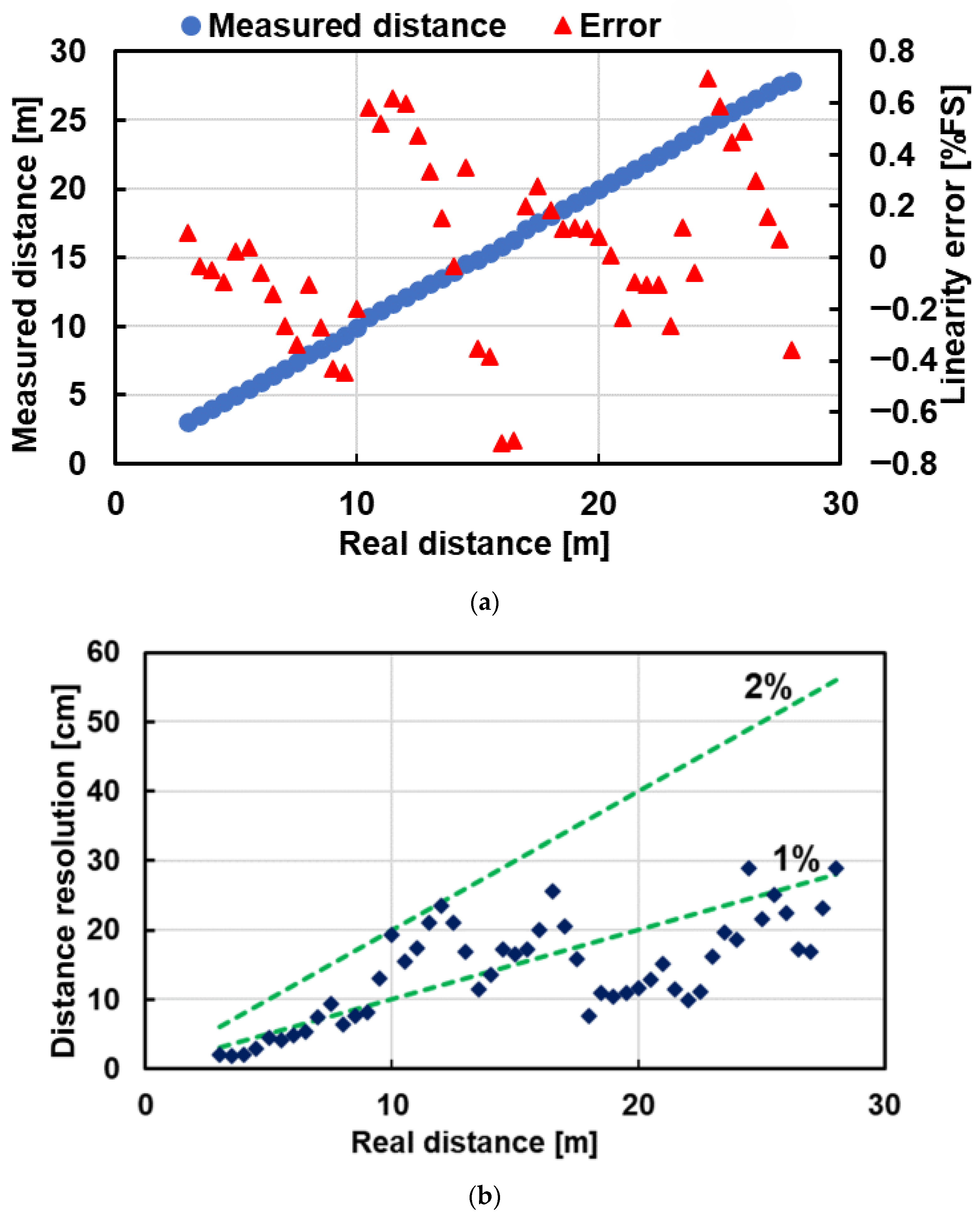

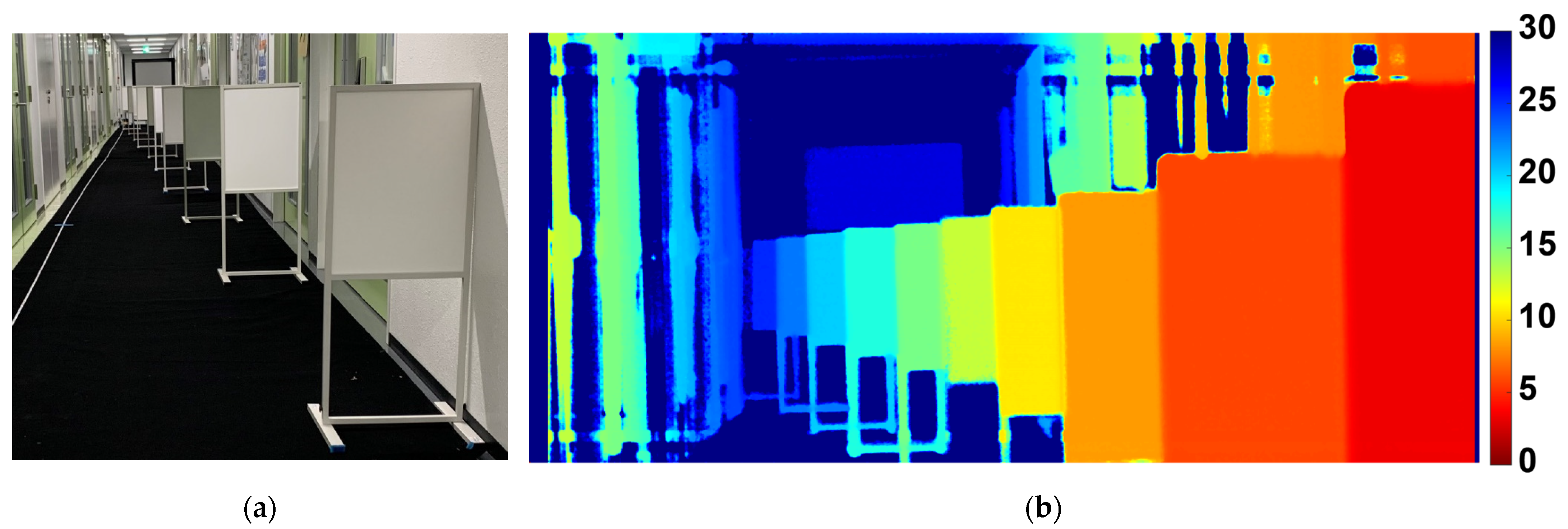

3.3. Range Measurement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoppa, D.; Massari, N.; Pancheri, L.; Malfatti, M.; Perenzoni, M.; Gonzo, L. A Range Image Sensor Based on 10-μm Lock-In Pixels in 0.18-μm CMOS Imaging Technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2011, 46, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamji, C.S.; O’Connor, P.; Elkhatib, T.; Mehta, S.; Thompson, B.; Prather, L.A.; Snow, D.; Akkaya, O.C.; Daniel, A.; Payne, A.D.; et al. A 0.13-µm CMOS system-on-chip for a 512 × 424 time-of-flight image sensor with multi-frequency photo-demodulation up to 130 MHz and 2 GS/s ADC. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2015, 50, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Han, S.-W.; Kang, B.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.D.K.; Kim, C.-Y. A three-dimensional time-of-flight CMOS image sensor with pinned-photodiode pixel structure. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2010, 31, 1272–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttgen, B.; Lustenberger, F.; Seitz, P. Demodulation pixel based on static drift fields. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2006, 53, 2741–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durini, D.; Brockherde, W.; Ulfig, W.; Hosticka, B.J. Time-of-flight 3-D imaging pixel structures in standard CMOS processes. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2008, 43, 1594–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickermann, A.; Durini, D.; Suss, A.; Ulfig, W.; Brockherde, W.; Hosticka, B.J.; Schwope, S.; Grabmaier, A. CMOS 3D image sensor based on pulse modulated time-of-flight principle and intrinsic lateral drift-field photodiode pixels. In Proceedings of the ESSCIRC 2011—European Solid-State Circuits Conference (ESSCIRC), Helsinki, Finland, 12–16 September 2011; pp. 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamji, C.S.; Mehta, S.; Thompson, B.; Elkhatib, T.; Wurster, S.; Akkaya, O.; Payne, A.; Godbaz, J.; Fenton, M.; Rajasekaran, V.; et al. 1Mpixel 65 nm BSI 320 MHz Demodulated TOF Image Sensor with 3.5 μm Global Shutter Pixels and Analog Binning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 11–15 February 2018; pp. 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Sano, T.; Moriyama, Y.; Maeda, S.; Yamazaki, T.; Nose, A.; Shiina, K.; Yasu, Y.; van der Tempel, W.; Ercan, A.; et al. 320 × 240 back-illuminated 10 µm CAPD pixels for high-speed modulation time-of-flight CMOS image sensor. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2018, 53, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebiko, Y.; Yamagishi, H.; Tatani, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Moriyama, Y.; Hagiwara, Y.; Maeda, S.; Murase, T.; Suwa, T.; Arai, H.; et al. Low power consumption and high resolution 1280 × 960 gate assisted photonic demodulator pixel for indirect time of flight. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–18 December 2020; pp. 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Seo, S.; Cho, S.; Choi, S.-H.; Hwang, T.; Kim, Y.; Jin, Y.-G.; Oh, Y.; Keel, M.-S.; Kim, D.; et al. A 2.8 µm pixel for time-of-flight CMOS image sensor with 20 ke-full-well capacity in a tap and 36 % quantum efficiency at 940 nm wavelength. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–18 December 2020; pp. 33.2.1–33.2.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, M.-S.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Bae, M.; Ki, M.; Chung, B.; Son, S.; Lee, H.; Jo, H.; Shin, S.-C.; et al. A 4-tap 3.5 µm 1.2 Mpixel indirect time-of-flight CMOS image sensor with peak current mitigation and multi-user interference cancellation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–22 February 2021; pp. 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, K.; Okubo, Y.; Nakagome, T.; Makino, M.; Takashima, H.; Akutsu, T.; Sawamoto, T.; Nagase, M.; Noguchi, T.; Kawahito, S. A hybrid ToF image sensor for long-range 3D depth measurement under high ambient light conditions. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2023, 58, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Kwon, Y.; Seo, S.; Keel, M.-S.; Lee, C.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Cho, S.; Kim, Y.; Jin, Y.-G.; et al. A 4-tap global shutter pixel with enhanced IR sensitivity for VGA time-of-flight CMOS image sensors. Electron. Imaging 2020, 32, 103-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubert, C.; Mellot, P.; Desprez, Y.; Mas, C.; Authié, A.; Simony, L.; Bochet, G.; Drouard, S.; Teyssier, J.; Miclo, D.; et al. 4.6-µm low-power indirect time-of-flight pixel achieving 88.5% demodulation contrast at 200 MHz for 0.54-MPix depth camera. In Proceedings of the 51st European Solid-State Device Research Conference (ESSDERC), Grenoble, France, 13–22 September 2021; pp. 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamji, C.; Godbaz, J.; Oh, M.; Mehta, S.; Payne, A.; Ortiz, S.; Nagaraja, S.; Perry, T.; Thompson, B. A review of indirect time-of-flight technologies. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2022, 69, 2779–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Moreno-Garcia, M.; Köklü, G.; Gancarz, R.M.; Büttgen, B.; Biber, A.; Furrer, D.; Stoppa, D. Optimization of pinned photodiode pixels for high-speed time-of-flight applications. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2018, 6, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.S.; Kong, H.K.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, K.; Bae, K.; Kim, S.B.; Kim, S.; Lim, M.; Ahn, J.C.; Kim, T.-C.; et al. Backside-illumination 14 μm-pixel QVGA time-of-flight CMOS imager. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 10th International New Circuits and Systems Conference (NEWCAS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–20 June 2012; pp. 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiyama, I.; Yokogawa, S.; Ikeda, H.; Ebiko, Y.; Hirano, T.; Saito, S.; Oinoue, T.; Hagimoto, Y.; Iwamoto, H. Near-infrared sensitivity enhancement of a back-illuminated CMOS image sensor with a pyramid surface for diffraction structure. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–6 December 2017; pp. 16.4.1–16.4.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahito, S.; Yasutomi, K.; Mars, K. Hybrid time-of-flight image sensors for middle-range outdoor applications. IEEE Open J. Solid-State Circuits Soc. 2022, 2, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, R.; Shirakawa, Y.; Mars, K.; Yasutomi, K.; Kagawa, K.; Aoyama, S.; Kawahito, S. A Time-of-Flight Image Sensor Using 8-Tap P-N Junction Demodulator Pixels. Sensors 2023, 23, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuyama, T.; Sugimura, H.; Alcade, G.; Ageishi, S.; Kwen, H.W.; Lioe, D.X.; Mars, K.; Yasutomi, K.; Kagawa, K.; Kawahito, S. A Short-Pulse Indirect ToF Imager Using 6-Tap Pixel with Backside Illuminated Structure for High-Speed Charge Demodulation. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Image Sensor Workshop (IISW 2025), Awaji Yumebutai International Conference Centre, Hyogo, Japan, 2–5 June 2025; pp. 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schinke, C.; Christian Peest, P.; Schmidt, J.; Brendel, R.; Bothe, K.; Vogt, M.R.; Kröger, I.; Winter, S.; Schirmacher, A.; Lim, S.; et al. Uncertainty analysis for the coefficient of band-to-band absorption of crystalline silicon. AIP Adv. 2015, 5, 067168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A. Self-consistent optical parameters of intrinsic silicon at 300 K. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.M. Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger, M. Adaptive Digital Filters, 2nd ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.-M.; Takasawa, T.; Yasutomi, K.; Aoyama, S.; Kagawa, K.; Kawahito, S. A time-of-flight range image sensor with background cancelling lock-in pixel based on lateral electric field charge modulation. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 2015, 3, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gate (High) | [ps] | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 µm | 10 µm | |

| G1 | 154 | 265 |

| G3 | 156 | 267 |

| G5 | 163 | 274 |

| Drain (GD) | 141 | 252 |

| Average | 153.5 | 264.5 |

| z [µm] | y [µm] | [ps] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x = 1.4 [µm] | x = 2.4 [µm] | x = 3.4 [µm] | x = 4.4 [µm] | x = 5.4 [µm] | ||

| 5 | 2.2 | 1160 | 1120 | 206 | 169 | 150 |

| 4.2 | 377 | 307 | 141 | 125 | 107 | |

| 6.2 | 1160 | 1120 | 206 | 169 | 150 | |

| 10 | 2.2 | 1271 | 1230 | 318 | 280 | 261 |

| 4.2 | 490 | 419 | 252 | 236 | 218 | |

| 6.2 | 1271 | 1230 | 318 | 280 | 261 | |

| Gate | FSI | BSI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWHM [ns] | τ1 | τ2 | FWHM [ns] | τ1 | τ2 | |

| G1 | 1.628 | 0.823 | 1.890 | 1.522 | 0.362 | 0.977 |

| G2 | 1.598 | 0.739 | 2.294 | 1.465 | 0.408 | 0.973 |

| G3 | 1.639 | 0.827 | 2.154 | 1.559 | 0.386 | 0.757 |

| G4 | 1.547 | 0.661 | 2.025 | 1.589 | 0.346 | 0.726 |

| G5 | 1.590 | 0.697 | 1.837 | 1.517 | 0.320 | 0.620 |

| G6 | 1.487 | 0.407 | 2.150 | 1.510 | 0.246 | 0.590 |

| Average | 1.582 | 0.692 | 2.058 | 1.527 | 0.345 | 0.774 |

| Measurement Parameter | Setting |

|---|---|

| Chip process | 0.11-µm CIS (BSI) |

| Number of Subframes | 2 |

| Wavelength of LD | 940 nm |

| NIR band filter | 940 ± 10 nm |

| Light pulse width | 15 ns |

| Duty ratio of light pulse | 5% |

| Frame rate | 30 fps |

| Environment | Indoor |

| Distance range | 3–28 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okuyama, T.; Sugimura, H.; Alcade, G.; Ageishi, S.; Kwen, H.W.; Lioe, D.X.; Mars, K.; Yasutomi, K.; Kagawa, K.; Kawahito, S. A Short-Pulse Indirect ToF Imager Using Six-Tap Pixel with a Backside-Illuminated Structure for High-Speed Demodulation. Sensors 2025, 25, 7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247581

Okuyama T, Sugimura H, Alcade G, Ageishi S, Kwen HW, Lioe DX, Mars K, Yasutomi K, Kagawa K, Kawahito S. A Short-Pulse Indirect ToF Imager Using Six-Tap Pixel with a Backside-Illuminated Structure for High-Speed Demodulation. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247581

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkuyama, Tomohiro, Haruya Sugimura, Gabriel Alcade, Seiya Ageishi, Hyeun Woo Kwen, De Xing Lioe, Kamel Mars, Keita Yasutomi, Keiichiro Kagawa, and Shoji Kawahito. 2025. "A Short-Pulse Indirect ToF Imager Using Six-Tap Pixel with a Backside-Illuminated Structure for High-Speed Demodulation" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247581

APA StyleOkuyama, T., Sugimura, H., Alcade, G., Ageishi, S., Kwen, H. W., Lioe, D. X., Mars, K., Yasutomi, K., Kagawa, K., & Kawahito, S. (2025). A Short-Pulse Indirect ToF Imager Using Six-Tap Pixel with a Backside-Illuminated Structure for High-Speed Demodulation. Sensors, 25(24), 7581. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247581