Instrumentation Strategies for Monitoring Flow in Centrifugal Compressor Diffusers: Techniques and Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Instrumentation Standards

3. Inlet and Ducts

3.1. Typical Instrumentation Suit

- Total and static pressure measurements: Kiel probes which are insensitive to yaw, Pitot-static tubes, multi-hole (3–7 hole) probes, and rakes for circumferential and radial surveys.

- Temperature measurements: fast-response, shielded thermocouples, or thin-film RTDs and other total temperature probes with recovery correction.

- Flow angle and swirl measurements: calibrated multi-hole probes and cobra probes in low-speed ducts.

- Boundary layer and turbulence measurements: Pitot traverses, Preston tubes, hot-wire or hot-film anemometry within the proper temperature limits and surface hot-film arrays.

- Unsteadiness measurements: high-frequency pressure transducers (flush-mount) for buffet and/or pulsation, dynamic temperature (via fine thermocouples) if necessary.

- Optical measurements (as the assembly allows): PIV or LDV windows for research rigs, schlieren, or BOS for large scale gradients.

- Surface measurements: static taps, wall shear oil-film interferometry if there is optical access, temperature paints for icing or other heat-transfer studies.

3.2. Core Metrics

3.3. Probe Layout and Traversing

3.4. Uncertainty and Calibration

4. Centrifugal Compressors Diffusers Instrumentation: Techniques and Principles

4.1. Pressure Measurements for Diffusers

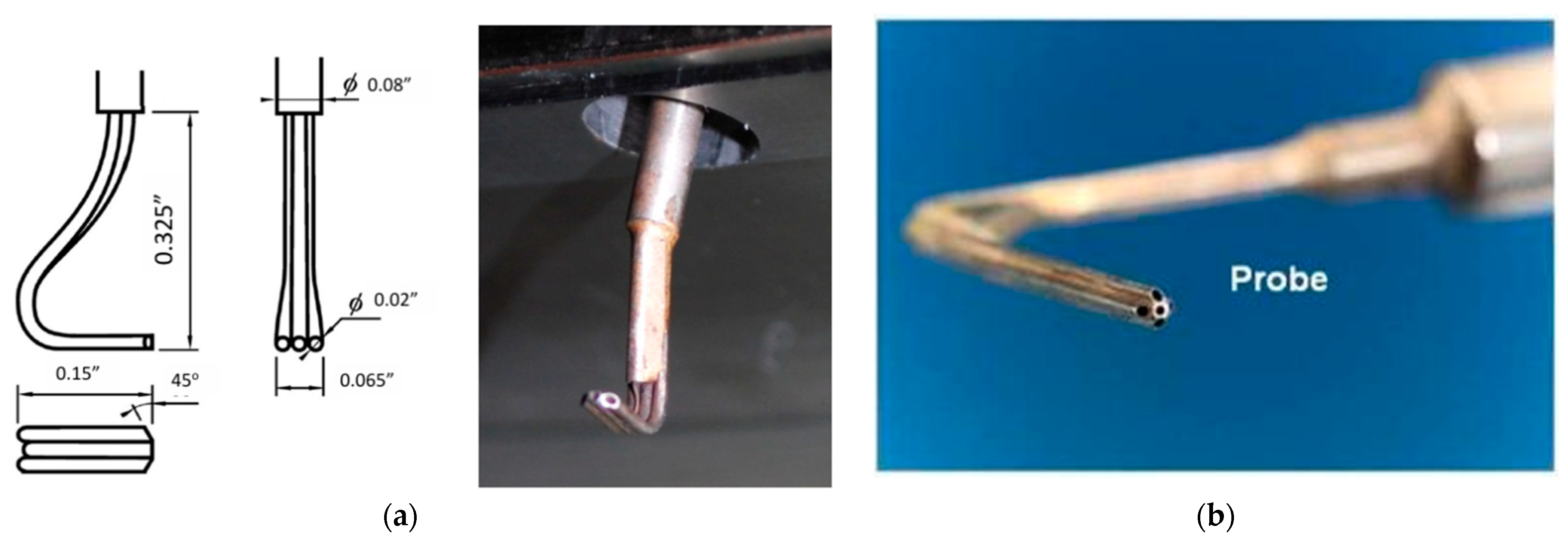

4.1.1. Total Pressure

4.1.2. Static Pressure Ports

4.2. Pressure and Temperature Sensitive Paints

4.3. Temperature Measurements

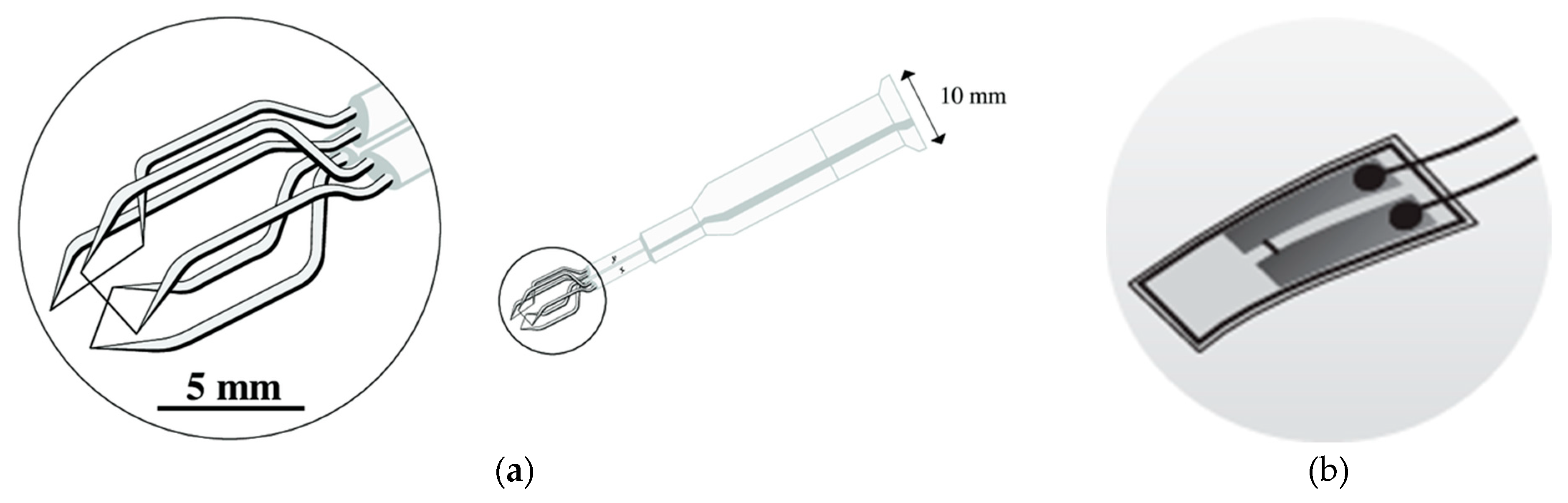

4.4. Flow Visualization and Velocity Measurement

4.4.1. Mass Flow Rate Measurements

4.4.2. Velocity Measurements

4.5. Vibration and Acoustic Monitoring

- Vibration sensors—measure mechanical vibrations to detect imbalance, misalignment, or structural issues. In this category there are:

- Piezoelectric accelerometers: mounted on the diffuser casing, near the diffuser vanes, and on supporting structures to measure vibrations in multiple directions.

- MEMS accelerometers: small, lightweight sensors that can be mounted directly on diffuser walls or rotor housings.

- Laser Doppler Vibrometer (LDV): non-contact measurement for lab studies, aimed at diffuser blades or casing to capture vibrations without physical attachment.

- 2.

- Acoustic sensors—capture aerodynamic noise and pressure pulsations caused by flow instabilities.

- Microphones: positioned outside the diffuser casing to capture airborne noise or in anechoic sections of test rigs.

- Hydrophones: if the diffuser handles fluid noise (like in water or liquid-gas testing), placed in flow channels.

- Pressure transducers/flush-mounted sensors: flush-mounted with the diffuser wall at selected locations along the hub, shroud, and near the diffuser vanes to measure wall-pressure fluctuations directly.

- 3.

- Data acquisition and signal processing

- DAQ Systems: high-speed acquisition units connected to accelerometers, microphones, and pressure transducers.

- Software tools: FFT analyzers, order tracking software, and operational deflection shape (ODS) analysis tools to interpret vibrations and acoustic patterns.

- 4.

- Optional advanced instrumentation

- Acoustic beamforming arrays: a set of microphones placed around the diffuser to localize noise sources.

- High-speed cameras or schlieren systems: for visualizing flow instabilities, often paired with acoustic measurements in laboratory setups.

5. Case Studies and Real-World Applications

5.1. Industrial/Retrofitted

5.1.1. Pressure-Based Monitoring

- A.

- DLR–Liebherr Single-Stage Centrifugal Compressor Facility

- B.

- Industrial Centrifugal Compressor Test Rig for Dynamic Pressure Measurements

- C.

- Dynamic Instrumentation for Surge Detection in a High-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Turbocharger

- High-response pressure probes (Kulite) were installed at the impeller inlet (P1, 280° circumferential) and mid-diffuser section (P2, 50°). These probes have very high natural frequencies and can operate across a wide temperature range (−55 °C to 273 °C). The sampling frequency was set to 50 kHz, capturing small-scale instabilities and pressure perturbations up to the surge point.

- Fast-response thermocouples (Müller Instruments) were located near P1 and P2, with a minimum response time of 3 μs. Dynamic temperature measurements were obtained by summing the measured variation with the ambient temperature, providing reliable monitoring of thermal fluctuations in the flow.

- ICP microphones were positioned near the compressor shroud (S1) and the inlet duct (S2) to measure vibration-induced and aerodynamic noise, respectively. Microphone signals were sampled at 50 kHz; a low-pass filter (cut-off at 15% of shaft rotation frequency) was applied to separate mechanical vibration from aerodynamic features.

- Dynamic pressure signals accurately reflected flow instabilities and small-scale perturbations in the impeller and diffuser, with the standard deviation (SD) slope increasing as mass flow approached surge.

- Microphone signals were less reliable for direct surge detection without filtering due to mechanical vibrations; post-processing was required to isolate aerodynamic contributions.

- Dynamic temperature measurements, particularly in the diffuser, provided the most effective indicator of surge onset. High-pass filtered SD maps displayed a clear rise-turn pattern at the minimum flow limit, across all rotational speeds and surge types.

- D.

- Low-Specific-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Stage at the CSTAR Facility

- Incidence becomes more positive as mass flow decreases, with unsteady variations caused by impeller jets and wakes.

- Positive incidence improves diffuser effectiveness and reduces total pressure loss, while negative incidence reduces performance.

- Diffuser vane leading edges experience the highest loading and pressure differentials, particularly during surge, highlighting failure-prone regions.

- Spike-type stall originates in the vaneless space and can trigger full-stage surge with rapid flow reversal.

- Computational predictions using the BSL-EARSM turbulence model aligned reasonably with measurements, providing insight for safe operating limits.

5.1.2. Acoustic and Vibration Instrumentation

- A.

- Vibro-Acoustic Instrumentation of a Two-Stage Centrifugal Compressor for Fuel Cell Systems

5.2. Research/Experimental Facilities

5.2.1. Pressure-Based Instrumentation

- A.

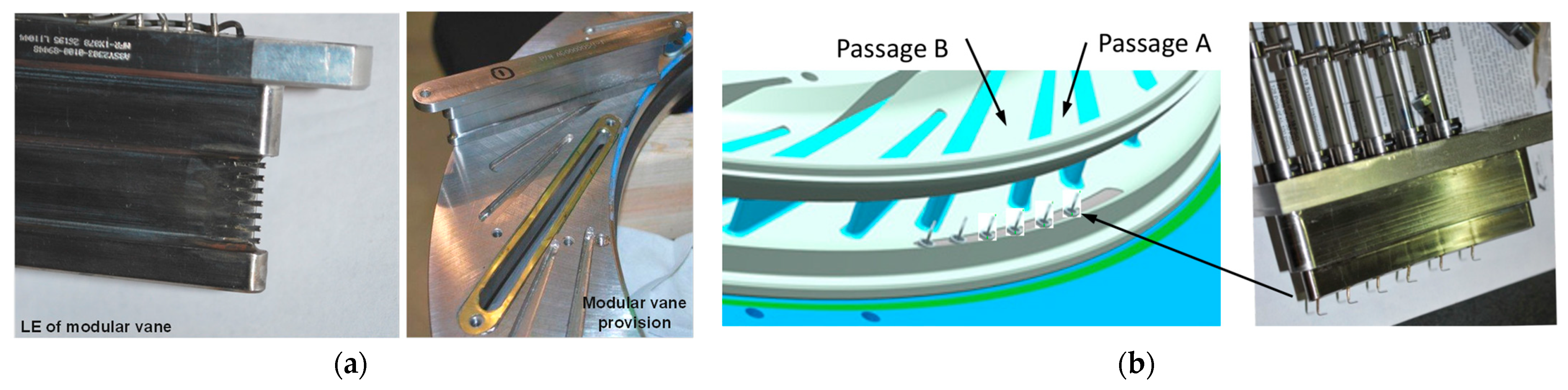

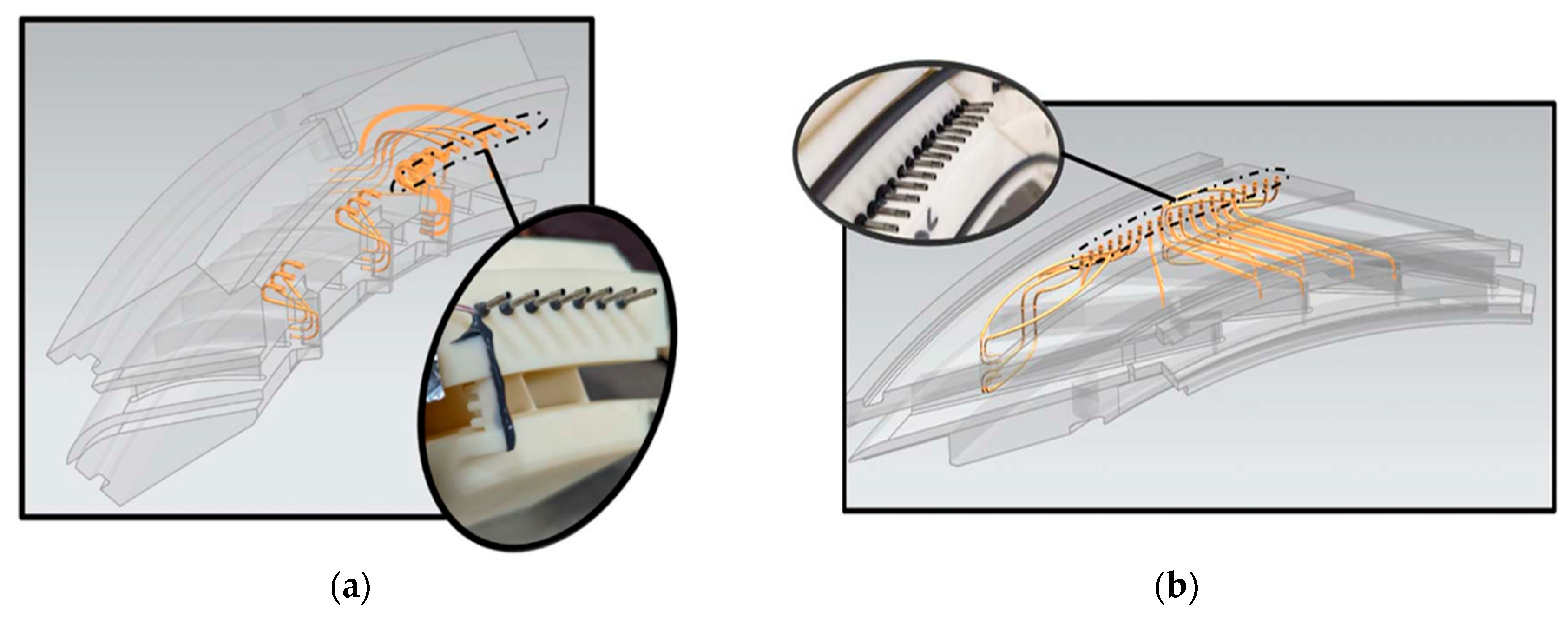

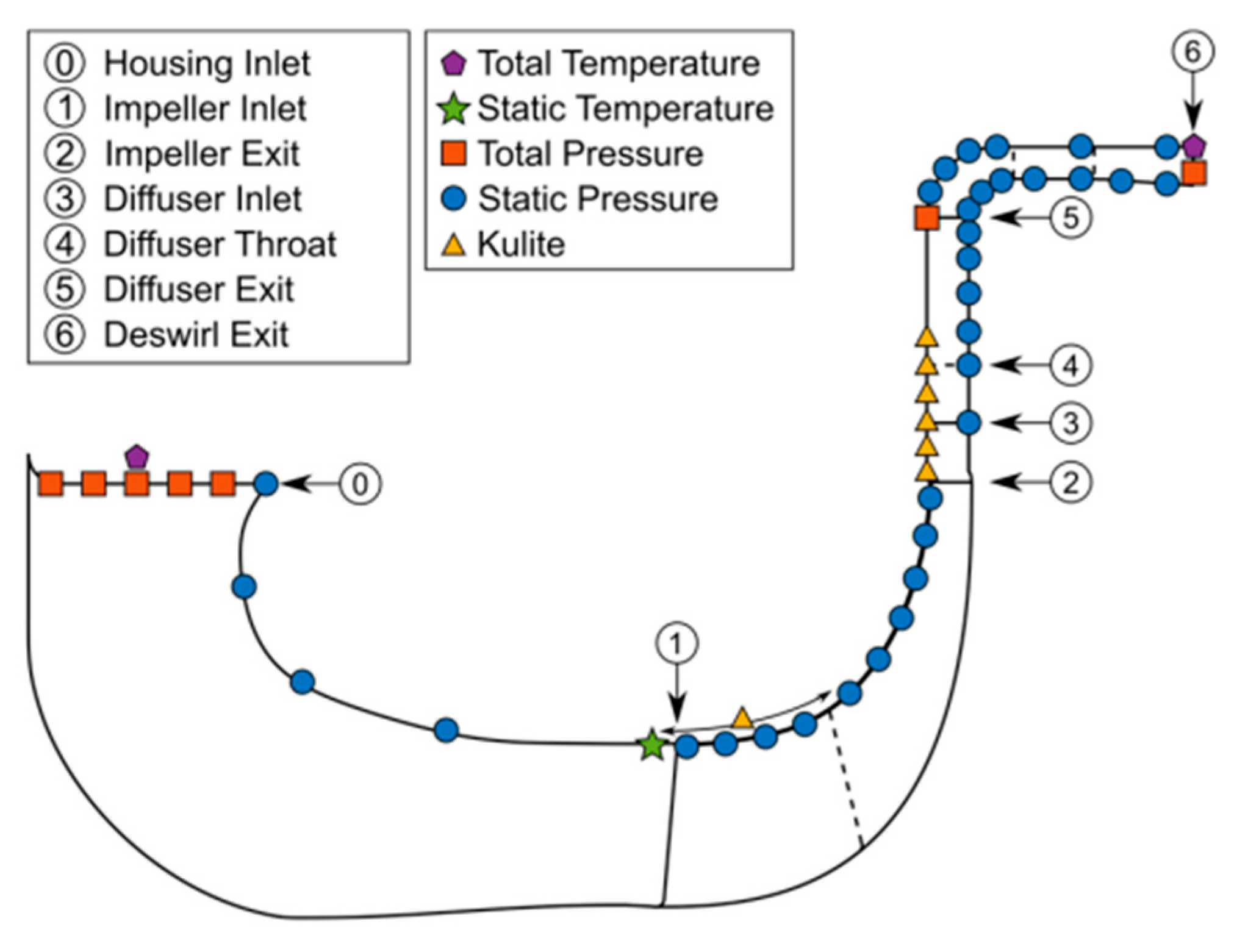

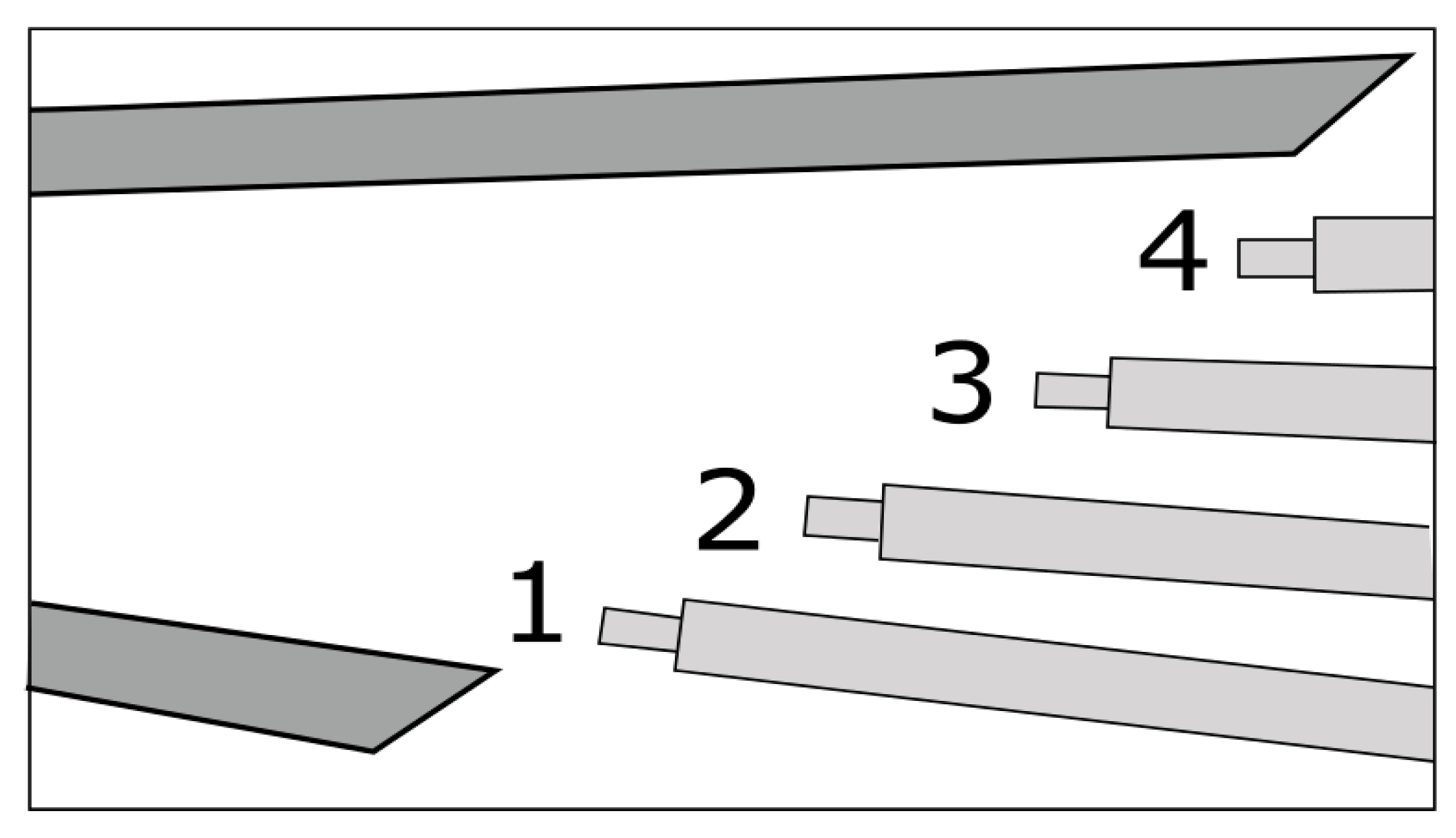

- Single-Stage Centrifugal Compressor (SSCC) Facility, Purdue University

- B.

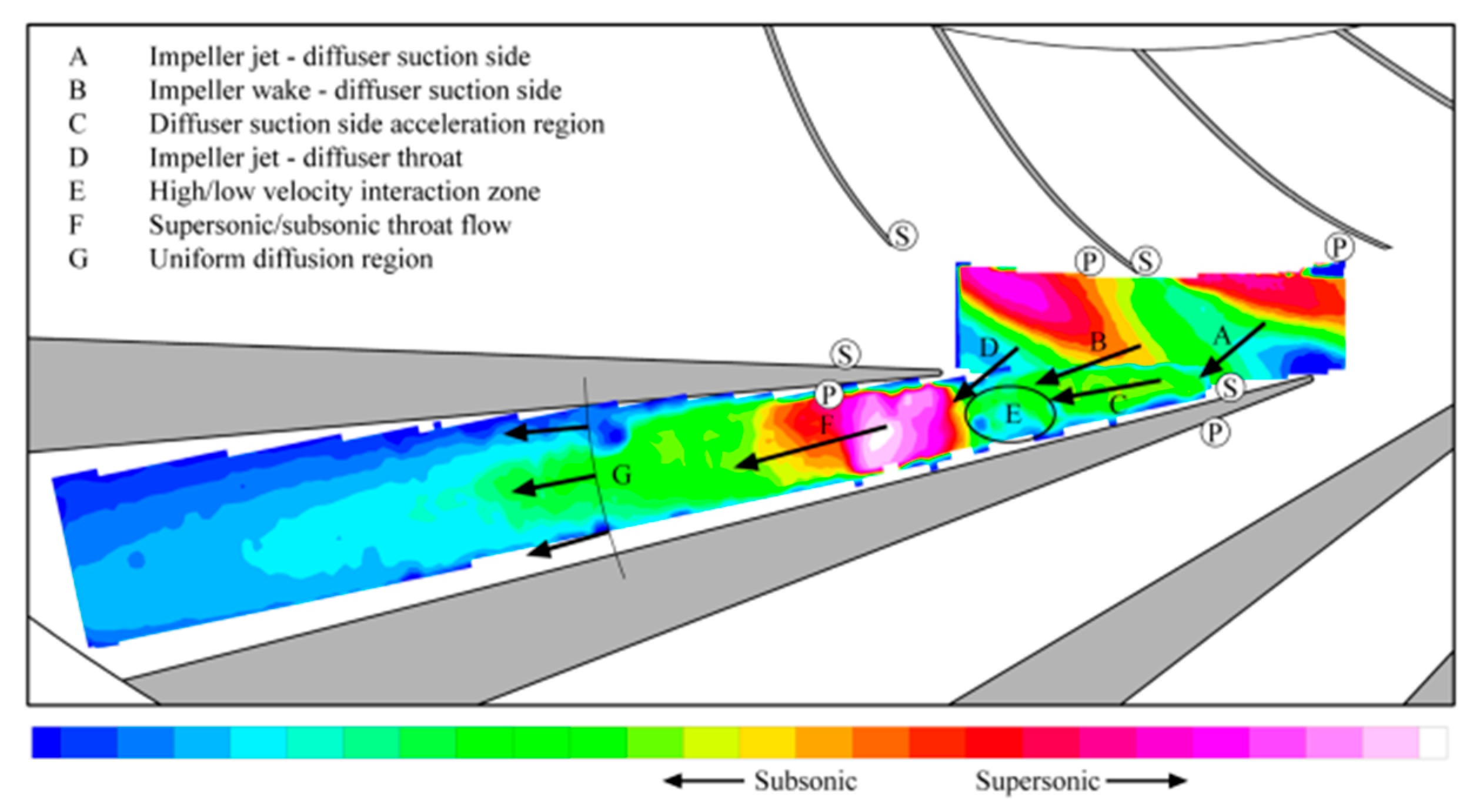

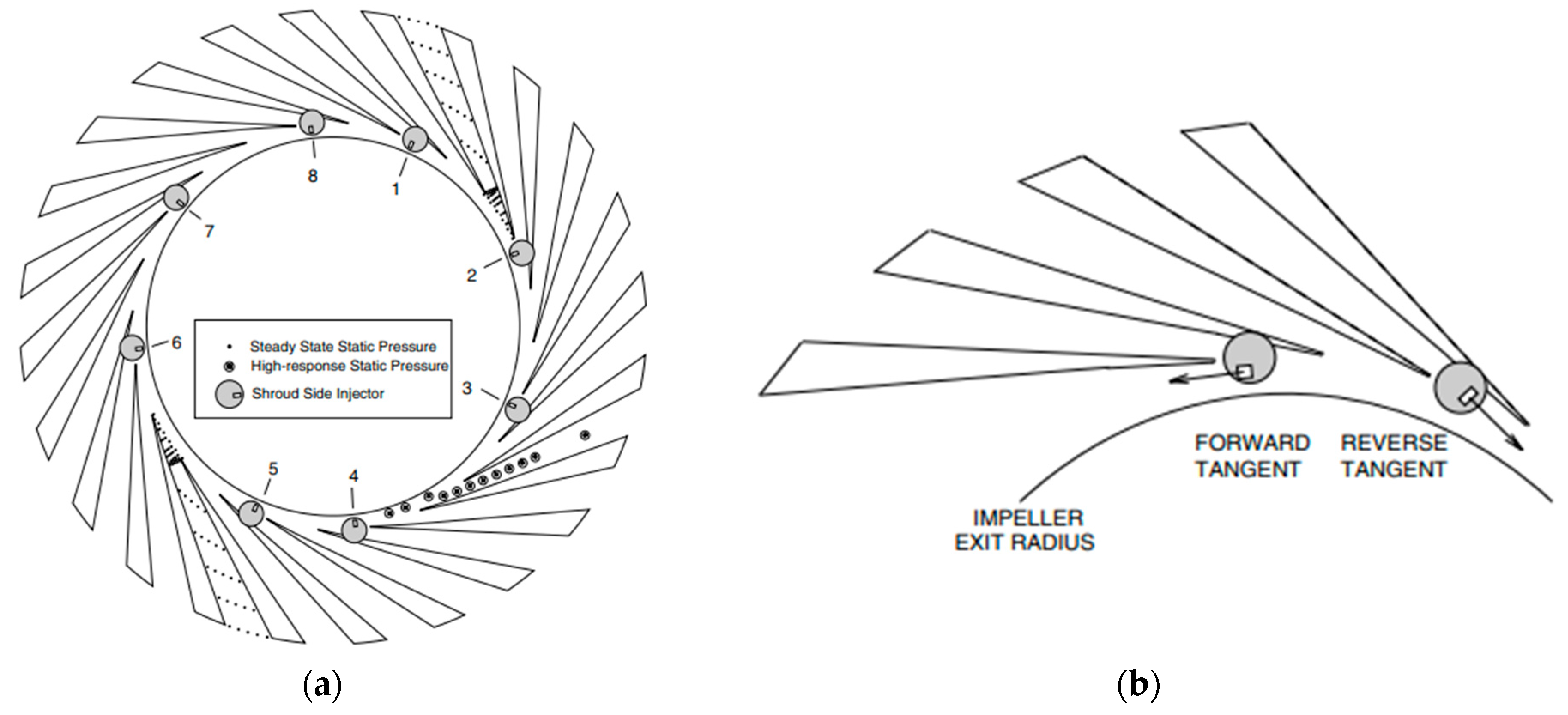

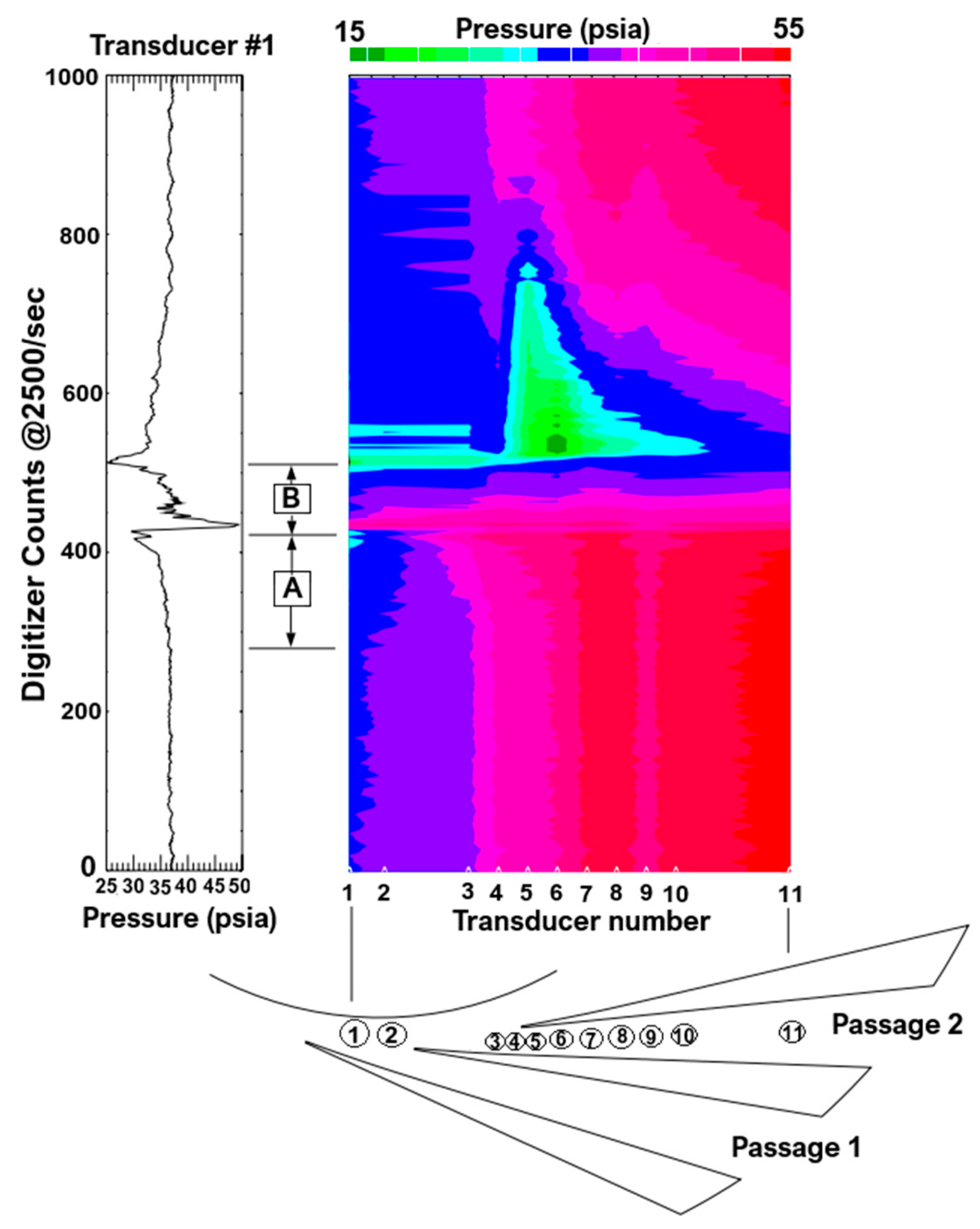

- NASA Glenn Research Center—Centrifugal Compressor Diffuser Instrumentation Using DPIV and Pressure Transducers

- C.

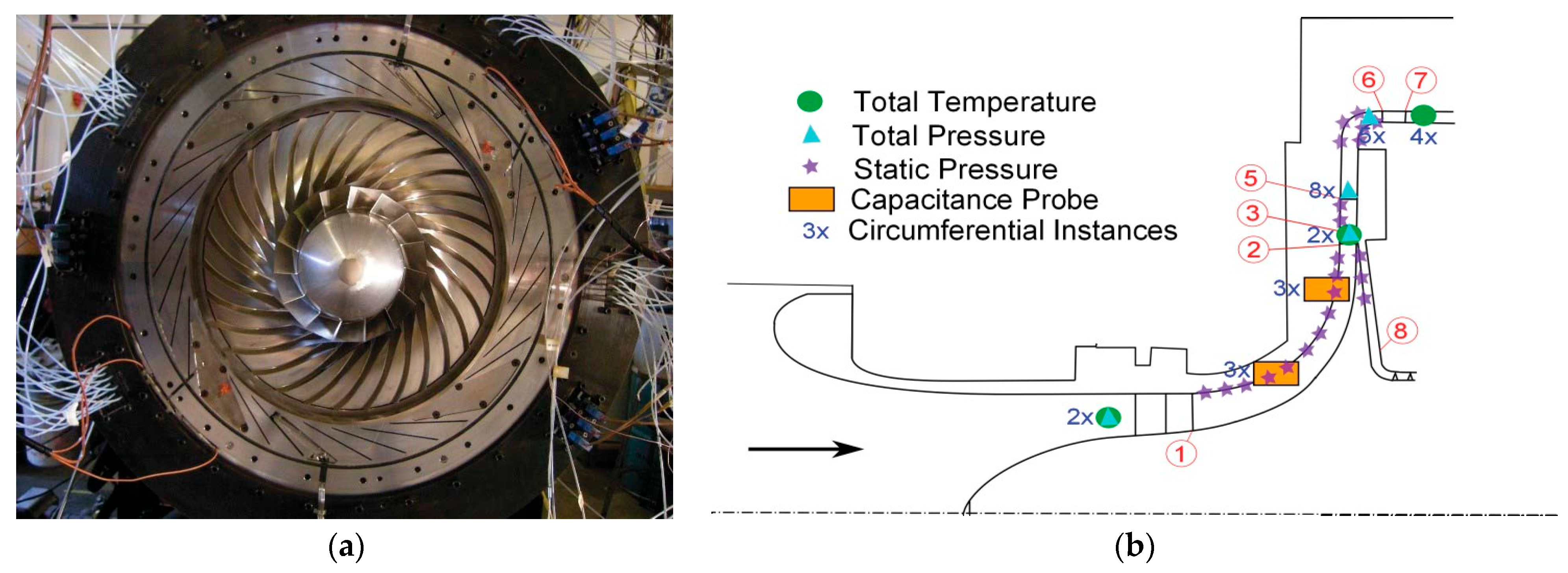

- Experimental Study of a Centrifugal Compressor Stage with Advanced Instrumentation at CSTAR

- Tighter clearances reduced over-the-tip leakage, improving total pressure ratio, isentropic efficiency, and choking mass flow.

- Tip clearance had minimal impact on surge margin.

5.2.2. Optical/Velocity-Based Instrumentation

- A.

- Purdue University High-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Facility

- B.

- NASA Glenn Research Center—Instrumentation for Active and Passive Flow Control in a Centrifugal Compressor Diffuser

6. Analysis and Discussion

- A.

- Pressure-Based Monitoring

- B.

- Temperature and Acoustic/Vibro-Acoustic Measurements

- C.

- Optical/PIV Techniques

- Instrumentation fidelity and placement: dense, high-frequency transducer networks, particularly with circumferential and radial coverage, provide superior resolution of propagating instabilities. Strategic placement in diffuser passages and impeller vaneless spaces captures critical precursor events.

- Multi-parameter integration: combining pressure, temperature, PIV, and acoustic measurements significantly enhances detection accuracy. Synchronized systems (IRIG-B or phase-locked) allow precise correlation between flow field dynamics, pressure fluctuations, and structural response, enabling robust predictive model validation.

- Flow control evaluation: In NASA Glenn experiments, distributed pressure sensors directly quantified the impact of active (air injection) and passive (capped tubes) flow control on surge margin, demonstrating the potential for real-time monitoring and optimization of compressor stability.

- Challenges: optical methods, while highly informative, are constrained by seeding uniformity, optical access, and large data volumes. Acoustic measurements can be influenced by environmental noise and require careful calibration to interpret instability signals accurately.

- High-speed pressure transducers provide primary detection of stall and surge, enabling frequency-domain analyses for model validation.

- Thermocouples, microphones, and accelerometers enhance early warning capabilities for rotating instabilities.

- Optical methods provide spatial validation of simulations and reveal three-dimensional flow features inaccessible via point measurements.

- Integration and synchronization are fundamental, as isolated measurements they cannot fully capture coupled flow–structure interactions.

- A.

- Sensor Types and Roles

- Pressure transducers: Essential for mapping transient instabilities and detecting stall/surge precursors (Cases 1, 2, 4).

- Thermocouples: Fast-response thermocouples were especially useful for surge detection (Case 4).

- Acoustic and vibration sensors: Enabled indirect detection of instabilities and provided predictive capabilities (Case 3).

- Optical methods (PIV): Allowed direct visualization of complex flow fields and shock structures (Case 1, 2).

- B.

- Data Acquisition Rates

- High-frequency sampling (≥20 kHz) is critical to capture blade-passing frequencies and transient flow phenomena.

- Optical PIV requires phase-resolved synchronization to reconstruct instantaneous flow fields.

- C.

- Placement and Coverage

- Circumferential arrays in impeller and diffuser regions enhance the ability to track rotating instabilities (Cases 2, 4).

- Strategic microphone and accelerometer placement captures acoustic precursors of surge in remote locations (Case 3).

- PIV measurements at inlet and diffuser exit capture spatio-temporal evolution of velocity fields (Cases 1, 2).

- D.

- Insights Enabled

- Pressure transducers + thermocouples allow quantitative surge/stall detection via SD, variance, and PSD analyses.

- Vibro-acoustic measurements enable early stall detection and validation of predictive models.

- PIV captures complex flow structures like shock formation, diffuser flow non-uniformities, and circumferential momentum variations.

- E.

- Limitations

- Microphones are sensitive to mechanical vibrations and require filtering.

- PIV is limited in shock resolution due to particle “smearing” and optical access constraints.

- High-density transducer arrays require careful calibration to ensure phase synchronization.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | American Petroleum Institute |

| ASME | American Society for Mechanical Engineers |

| BPF | blade passing frequencies |

| CFVN | critical-flow Venturi nozzles |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CSTAR | Centrifugal Stage for Aerodynamic Research |

| DSA | Digital Sensor Arrays |

| DPIV | Digital Particle Image Velocimetry |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| ISO | International Stadardisation Organisation |

| LDV | Laser Doppler Vibrometer |

| ODS | operational deflection shape |

| PIV | Particle Image Velocimetry |

| SSCC | single-stage centrifugal compressor |

| STFT | Short-Time Fourier Transform |

| TSP | temperature sensitive paints |

References

- Boyce, M.P. Gas Turbine Engineering Handbook, 2nd ed.; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M. Compressor Fundamentals. In Surface Production Operations; Stewart, M., Ed.; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2019; pp. 457–525. ISBN 978-0-12-809895-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, O.; Strătilă, S.; Drăgan, V. Design Methods and Practices for Centrifugal Compressor Diffusers: A Review. Machines 2025, 13, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajaali, A.; Stoesser, T. Flow Separation Dynamics in Three-Dimensional Asymmetric Diffusers. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2022, 108, 973–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R. Fuel Cell Compressor Systems. Available online: https://netl.doe.gov/sites/default/files/event-proceedings/fuel-cells-archive/Hardy.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ASME. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Available online: https://www.asme.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO. International Organization for Standardization. Available online: https://www.iso.org/home.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- API. American Petroleum Institute. Available online: https://www.api.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 39665; Turbocompressors—Performance Test Code. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/39665.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- PTC 10; Axial and Centrifugal Compressors. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.asme.org/codes-standards/find-codes-standards/axial-and-centrifugal-compressors/2022/pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- PTC 19.1; Test Uncertainty. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.asme.org/codes-standards/find-codes-standards/test-uncertainty (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO/IEC Guide 98-3:2008; Uncertainty of Measurement. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/50461.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO/IEC 17025; Testing and Calibration Laboratories. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: https://www.iso.org/ISO-IEC-17025-testing-and-calibration-laboratories.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- CEN Measurement Guidance. Available online: https://boss.cen.eu/reference-material/guidancedoc/pages/measure/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 21748; Guidance for the Use of Repeatability, Reproducibility and Trueness Estimates in Measurement Uncertainty Evaluation. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/71615.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 1217:2019; Displacement Compressors—Acceptance Tests. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:1217:ed-4:v1:en (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 10439-1; Petroleum, Petrochemical and Natural Gas Industries—Axial and Centrifugal Compressors and Expander-Compressors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/56883.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- API Standard 617; Axial and Centrifugal Compressors and Expander-Compressors. API: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.api.org/~/media/files/publications/whats%20new/617_e8%20pa.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- API Standard 672; Packaged, Integrally Geared Centrifugal Air Compressors for Petroleum, Chemical, and Gas Industry Services. API: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. Available online: https://sourcing.essar.com/GS/Portals/0/Download/API672_2004_4th_Edition.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 9300; Measurement of Gas Flow by Means of Critical Flow Nozzles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77401.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 5167-1; Measurement of Fluid Flow by Means of Pressure Differential Devices Inserted in Circular Cross-Section Conduits Running Full. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/79179.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 5167-2; Measurement of Fluid Flow by Means of Pressure Differential Devices Inserted in Circular Cross-Section Conduits Running Full. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/79180.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 5167-3; Measurement of Fluid Flow by Means of Pressure Differential Devices Inserted in Circular Cross-Section Conduits Running Full. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/84845.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 5167-4; Measurement of Fluid Flow by Means of Pressure Differential Devices Inserted in Circular Cross-Section Conduits Running Full. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/79181.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 2186; Fluid Flow in Closed Conduits—Connections for Pressure Signal Transmissions Between Primary and Secondary Elements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/es/#iso:std:iso:2186:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- PTC 19.3 TW; Thermowells. ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.asme.org/codes-standards/find-codes-standards/thermowells (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Thermocouple Measurement Reliability—Guide to IEC and ASTM Standards. Available online: https://www.thermo-electric.nl/thermocouple-measurement-reliability-a-guide-to-iec-and-astm-standards/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- API Standard 670; Machinery Protection Systems, 5th ed. API: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.api.org/~/media/files/publications/whats%20new/670_e5%20pa.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 63180; Mechanical Vibration—Measurement and Evaluation of Machine Vibration. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63180.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- NASA Glenn Research Center. Pitot-Static Tubes. Available online: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/k-12/VirtualAero/BottleRocket/airplane/pitot.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Aeroprobe Corporation. Kiel Probes. Available online: https://www.aeroprobe.com/kiel-probes/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Machnik, A.A.; Decker, T.; Ashworth, R.J. Tailoring Flight Test Instrumentation with Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the European Test and Telemetry Conference (ETTC 2022), Nuremberg, Germany, 10–12 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Chai, Z.; Ba, F.; Chen, X. Microstructure and Mechanical Property of Thin-Walled Inconel 718 Parts Fabricated by Ultrasonic-Assisted Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. Crystals 2025, 15, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quickel, R.A.; Powers, S.; Schetz, J.A.; Lowe, K.T. Mount Interference Effects on Total Temperature Probe Measurement. In Proceedings of the 4th Thermal and Fluids Engineering Conference (TFEC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–17 April 2019. Paper TFEC-2019-28249. [Google Scholar]

- Albertson, C.W.; Bauserman, W.A., Jr. Total Temperature Probes for High-Speed Flows; NASA TM 105001; NASA: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Büttgenbach, S.; Constantinou, I.; Dietzel, A.; Leester-Schädel, M. Piezoresistive Pressure Sensors. In Case Studies in Micromechatronics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 21–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsegora, O.I.; Arsenyeva, O.; Tovazhnyanskyy, L.; Kapustenko, P.O. Models of Fouling’s Formation on the Heating Surfaces and Their Application for Plate Heat Exchangers. Integr. Technol. Energy Sav. 2019, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMaster-Carr. Quick-Disconnect Fittings and Manifolds. Available online: https://www.mcmaster.com/products/manifolds/fitting-connection~quick-disconnect/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Clement, J.T.; Coon, A.T.; Key, N.L. Development of an Additively Manufactured Stationary Diffusion System for a Research Aeroengine Centrifugal Compressor. J. Turbomach. 2025, 147, 031004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jin, H.; Kim, M.-G.; Do, H. An Investigation of Internal Drag Correction Methodology for Wind Tunnel Test Data in a High-Speed Air-Breathing Vehicle Using Numerical Analysis. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 2024, 26, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunscheidel, E.P.; Welch, G.E.; Skoch, G.J.; Medic, G.; Sharma, O.P. Aerodynamic Performance of a Compact, High Work-Factor Centrifugal Compressor at the Stage and Subcomponent Level; NASA Technical Memorandum NASA/TM—2015-218455; NASA Glenn Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2015.

- NASA Glenn Research Center. Total Pressure Probe Calibration (TUNP5H). Available online: https://www.grc.nasa.gov/www/k-12/airplane/tunp5h.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Bobbitt, P.J.; Maglieri, D.J.; Banks, D.W.; Fuchs, A.W. Wedge and Conical Probes for the Instantaneous Measurement of Free-Stream Flow Quantities at Supersonic Speeds. In Proceedings of the 29th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27–30 June 2011; AIAA Paper 2011-3501 DFRC-E-DAA-TN3771. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20110023796 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Dwyer Omega. Pitot Tube (Resource Page). Available online: https://www.dwyeromega.com/en-us/resources/pitot-tube (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Schlienger, J.; Pfau, A.; Kalfas, A.I.; Abhari, R.S. Single Pressure Transducer Probe for 3D Flow Measurements. In Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Measuring Techniques in Transonic and Supersonic Flow in Cascades and Turbomachines, Cambridge, UK, 23–24 September 2002; Available online: https://www-g.eng.cam.ac.uk/whittle/rigs/symposium/papers/5-3.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Klassen, H.A. Performance of a Low-Pressure-Ratio Centrifugal Compressor with Four Diffuser Designs; NASA Technical Report; NASA Lewis Research Center: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1973.

- Fradin, C. Detailed Measurements of the Flow in the Vaned Diffuser of a Backswept Transonic Centrifugal Impeller. In Proceedings of the 16th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS 1988), Jerusalem, Israel, 28 August–2 September 1988. Paper ICAS-88-2.6.2. [Google Scholar]

- Califano, N.; Lash, E.L.; Roozeboom, N.H. Camera Setup for Unsteady Pressure-Sensitive Paint at NASA Ames Research Center. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech Forum and Exposition, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2024; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20230016296 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Klein, C.; Yorita, D.; Henne, U. Comparison of Lifetime-Based Pressure-Sensitive Paint Measurements in a Wind Tunnel Using Model Pitch–Traverse and Pitch–Pause Modes. Photonics 2024, 11, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustard, A.N.; Noftz, M.E.; Hasegawa, M.; Sakaue, H.; Jewell, J.S.; Bisek, N.J.; Juliano, T.J. Dynamics of a 3-D Inlet/Isolator Measured with Fast Pressure-Sensitive Paint. Exp. Fluids 2024, 65, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. A Dynamic Zonal Method Based on KD-Tree for Calibration of Five-Hole Probe under Large Flow Angles. Measurement 2025, 253, 117598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, H. Design and Application of a Test Rig for Stationary Component Performance Measurement of Centrifugal Compressors. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2025, 18, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-S.; Chung, M.-K.; Yoo, J.-Y.; Kim, M.-U.; Kim, B.-J.; Jo, M.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, J.-B. Interference-Free Nanogap Pressure Sensor Array with High Spatial Resolution for Wireless Human–Machine Interface Applications. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Tan, K.-T.; Sakaue, H. The Development and Application of Two-Color Pressure-Sensitive Paint in Jet Impingement Experiments. Aerospace 2023, 10, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, K.R.; Rabe, D.C.; Fonov, S.D.; Goss, L.P.; Hah, C. The Application of Pressure- and Temperature-Sensitive Paints to an Advanced Compressor. J. Turbomach. 2001, 123, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senmatic. Tolerance Classes for Sensors According to IEC 60751. Available online: https://senmatic.com/knowledge/sensor/tolerance-classes-for-sensors-according-to-iec-60751/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Liu, D.; Jiao, R.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. Effects of Substrates on the Performance of Pt Thin-Film Resistance Temperature Detectors. Coatings 2024, 14, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Q.; Ge, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Shan, H. Advancements in Thermal Insulation through Ceramic Micro-Nanofiber Materials. Molecules 2024, 29, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthinathan, S.; Meenakshi, G.A.; Vinothini, S.; Yu, C.-L.; Chen, C.-L.; Chiu, T.-W.; Vittayakorn, N. A Review of Thin-Film Growth, Properties, Applications, and Future Prospects. Processes 2025, 13, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Sensor Corporation. Kiel Temperature Probes. Available online: https://www.unitedsensorcorp.com/kieltemp.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- IMEKO TC9. Measurement Uncertainty Conference Paper. 2019. Available online: https://www.imeko.org/publications/tc9-2022/IMEKO-TC9-2019-093.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ISO 3966; Measurement of Fluid Flow in Closed Conduits—Velocity Area Method Using Pitot Static Tubes. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/86000.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Pei, X.; Zhang, X. Review and prospect of high-precision Coriolis mass flowmeters for hydrogen flow measurement. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2025, 102, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.D. Performance of Critical Flow Venturis under Transient Conditions; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA.

- Ebefors, T. Polyimide V-Groove Joints for Three-Dimensional Silicon Transducers—Exemplified Through a 3-D Turbulent Gas Flow Sensor and Micro-Robotic Devices. Ph.D. Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden, 2000. TRITA-ILA-0001. [Google Scholar]

- Dantec Dynamics. Hot-Wire Probes. Available online: https://www.dantecdynamics.com/product-category/hot-wire-probes/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Randall, R.B. Vibration-Based Condition Monitoring: Industrial, Aerospace and Automotive Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg, J.; Allen, M.S.; Castellini, P.; Di Maio, D.; Dirckx, J.J.J.; Ewins, D.J.; Halkon, B.J.; Muyshondt, P.; Paone, N.; Ryan, T.; et al. An International Review of Laser Doppler Vibrometry: Making Light Work of Vibration Measurement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2017, 99, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, D.A.; Hansen, C.H. Engineering Noise Control: Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781315273464. [Google Scholar]

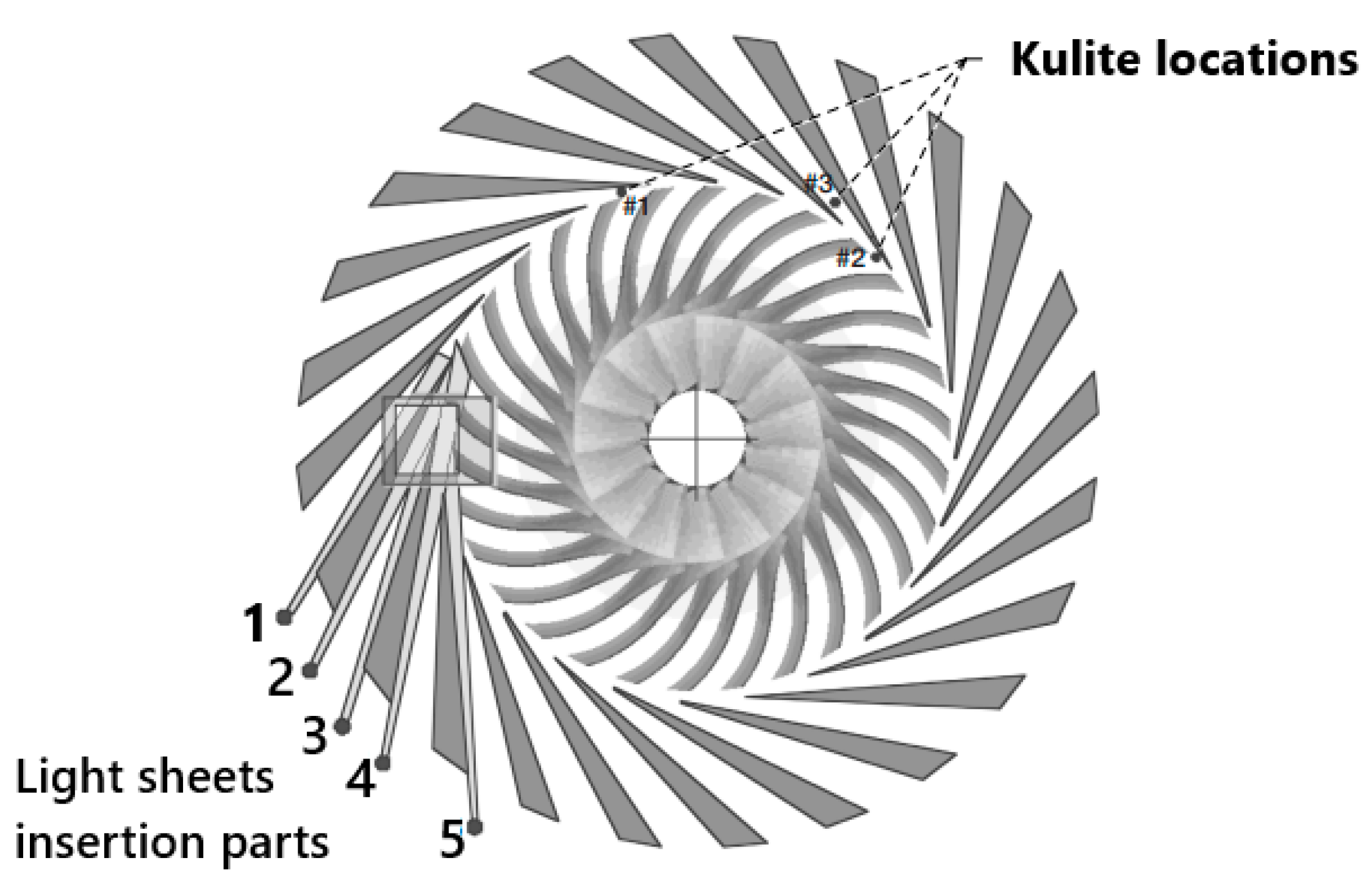

- Klinner, J.; Voges, M.; Schroll, M.; Bassetti, A.; Willert, C. Time-Resolved Flow Field Investigation in an Industrial Centrifugal Compressor Application Involving TR-PIV Synchronized with Unsteady Pressure Measurements. In Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Particle Image Velocimetry, Chicago, IL, USA, 1–4 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Wang, T. Experimental and Computational Analysis of the Unstable Flow Structure in a Centrifugal Compressor with a Vaneless Diffuser. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2019, 32, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.X.; Zheng, X.Q. Methods of Surge Point Judgment for Compressor Experiments. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2013, 51, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.A. Unsteady Performance of an Aeroengine Centrifugal Compressor Vaned Diffuser at Off-Design Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Mechanical Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 2151; Acoustics—Noise Test Code for Compressors and Vacuum Pumps—Engineering Method (Grade 2). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:2151:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Chen, S.; Zuo, S.; Wu, Z.; Liu, C. Comprehensive Vibro-Acoustic Characteristics and Mathematical Modeling of Electric High-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Surge for Fuel Cell Vehicles at Various Compressor Speeds. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 178, 109311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, F.; Harrison, H.M.; Brown, W.J.; Key, N.L. Investigation of Surge in a Transonic Centrifugal Compressor with Vaned Diffuser: Part 2—Correlation with Subcomponent Characteristics. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition (GT2022), Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 13–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

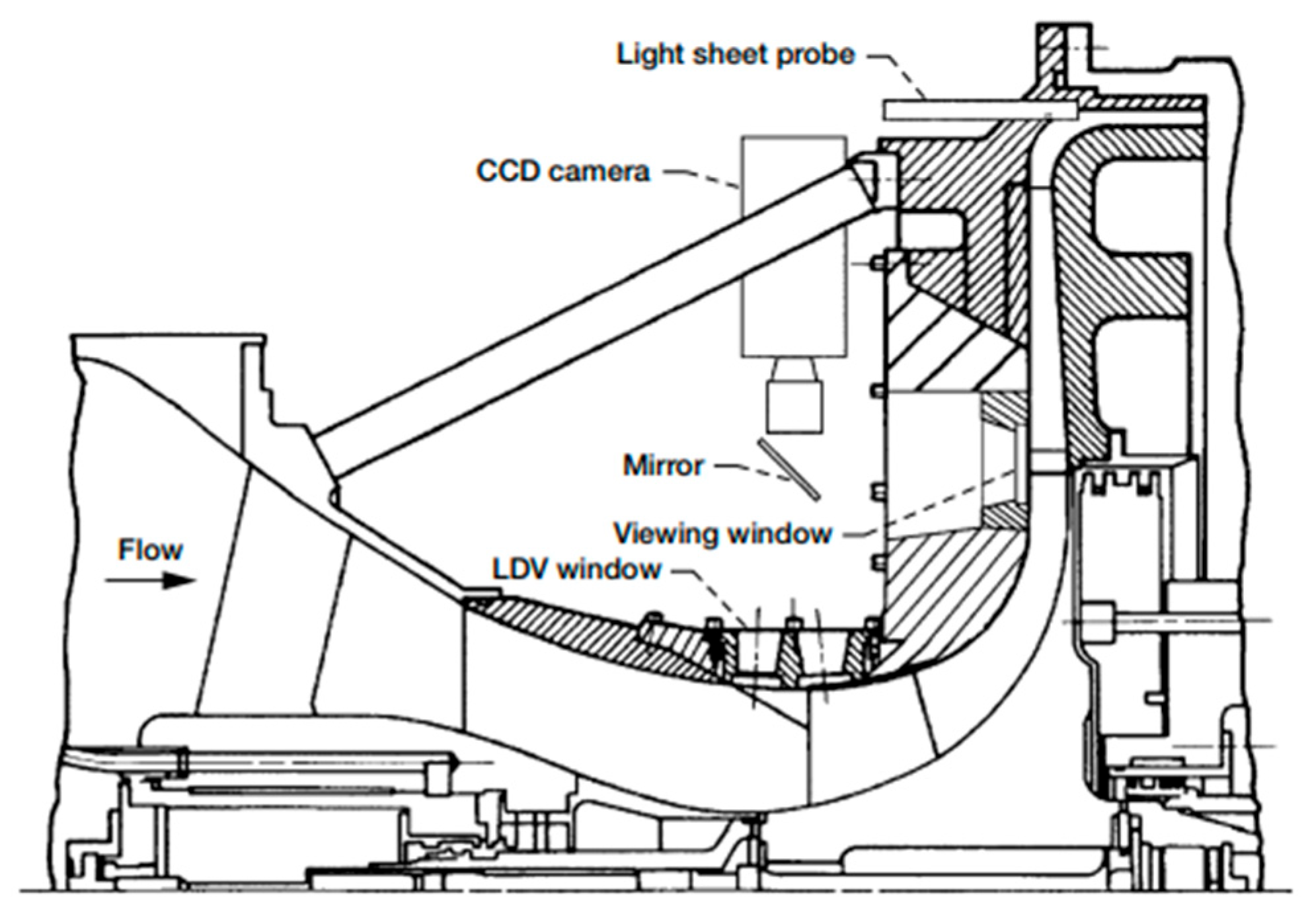

- Wernet, M.; Bright, M.; Skoch, G. An Investigation of Surge in a High-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Using Digital PIV. J. Turbomach. 2003, 123, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methel, C.-T.J. An Experimental Comparison of Diffuser Designs in a Centrifugal Compressor. Master’s Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2016. Available online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/796 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Cukurel, B.; Lawless, P.; Fleeter, S. PIV Investigation of a High-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Diffuser: Mid-Span Loading Effects. In Proceedings of the AIAA Conference, Hartford, CT, USA, 21–23 July 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoch, G.J. Experimental Investigation of Centrifugal Compressor Stabilization Techniques. NASA/TM—2003-212599. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20040047276/downloads/20040047276.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

| Quantity | Main Contributions | Typically Expanded Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| Total pressure () | Transducer calibration, resolution, temperature drift, rake blockage, port purging | ±0.2–0.5% of reading |

| Static pressure (p) | Tap location error, line losses, transducer cal., temp. effects | ±0.2–0.5% of reading |

| Total temperature () | Probe recovery factor r, radiation/conduction, time lag, calibration | ±0.5–1.0 K |

| Axial velocity () | From relation, EOS and angle misalignment | ±1–3% |

| Tangential velocity () | Multi-hole calibration map, alignment, port bias | ±2–4% |

| Radial velocity | Multi-hole calibration, probe stem interference | ±3–5% |

| Yaw (swirl) angle () | Multi-hole map fit, zeroing, alignment | ±0.5–1.5° |

| Radial angle () | As above, low signal levels | ±0.7–2.0° |

| Circumferential distortion () | Sector averaging, weighting (mass-flux), rake blockage, sparse sampling | ±0.01–0.03 (abs.) |

| Radial distortion () | Ring averaging, near-wall bias, sparse sampling | ±0.01–0.03 (abs.) |

| Turbulence intensity (Tu) | Sensor bandwidth, noise floor, sampling duration, seeding (PIV/LDV) | ±0.2–0.5% (abs.) |

| Boundary layer thickness () | Probe positioning, near-wall resolution, interpolation | ±0.5–1.0 mm |

| Shape factor (H) | Profile integration, near-wall accuracy | ±0.10–0.20 |

| Mass-flux weighting () | Area partitioning | ±0.5–1.5% |

| Probe positioning (x, r, ) | Traverse repeatability, backlash, fixturing | ±0.2–0.5 mm (radial), ±0.5–1.0° (θ) |

| Acquisition bandwidth | Anti-aliasing, sampling rate, filter phase lag | Specified, not a% |

| Sensor Type | Positioning | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric/MEMS accelerometers | Diffuser casing, near vanes, hub, or support structures | Mechanical vibration monitoring |

| Laser Doppler Vibrometer | Non-contact on blades or casing | Lab vibration analysis |

| Microphones | External casing, anechoic chambers | Aerodynamic noise detection |

| Pressure transducers | Flush with walls near vanes, hub, and shroud | Pressure pulsations and flow instabilities |

| Acoustic beamforming arrays | Surrounding diffuser | Noise source localization |

| Method | Key Advantages | Main Shortcomings/Outdated Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| Pitot/Kiel probes | Simple, robust, standardized; good for mean pressure fields | Intrusive; limited frequency response; blockage effects; yaw sensitivity; unsuitable for fast unsteady phenomena |

| Static taps and tubing systems | Accurate mean pressures; easy integration | Dynamic distortion, resonance, purge issues; limited to steady or low-frequency measurements |

| Multi-hole probes | Measures pressure + flow angles; essential for swirl mapping | Calibration-intensive; alignment-sensitive; fragile at high T; limited bandwidth |

| Hot-wire/hot-film anemometry | High temporal resolution for turbulence | Fragile; strong temperature constraints; intrusive; outdated for industrial compressors |

| Thermocouples/RTDs | Widely available; reliable for steady-state conditions | Slow response (most types); conduction/radiation bias; inadequate for surge dynamics |

| MEMS pressure/temperature sensors | High bandwidth; miniaturized; promising for rotors | Not yet robust for long-term high T operation; drift; packaging complexity |

| PSP/TSP | Global high-density fields; excellent for research | Requires optical access; temperature/illumination corrections; limited industrial applicability |

| LDV/PIV | High-resolution, non-intrusive velocity fields | Needs optical windows; seeding issues; costly; not feasible for in situ machinery |

| High-speed unsteady pressure arrays | Essential for stall/surge detection; kHz–MHz bandwidth | Local-only; cannot measure vector fields; sensitive to mounting and thermal gradients |

| Acoustic and vibration sensors | Good for instability detection; easy to integrate | Indirect measurements; require filtering; cannot resolve local flow structures |

| Case/Facility | Compressor Type and Specs | Instrumentation | Placement/Configuration | Sampling and Measurement Specs | Key Results/Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

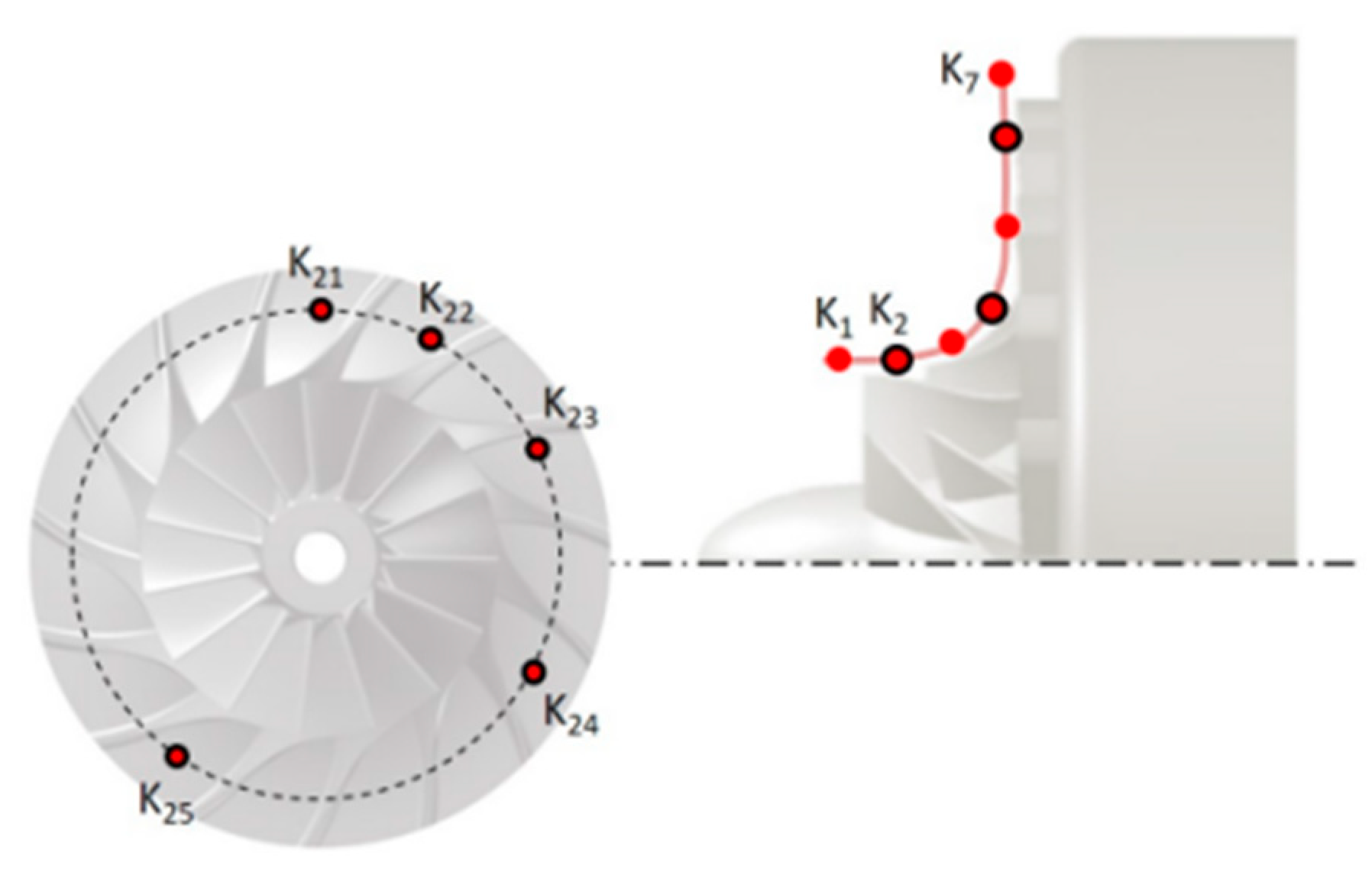

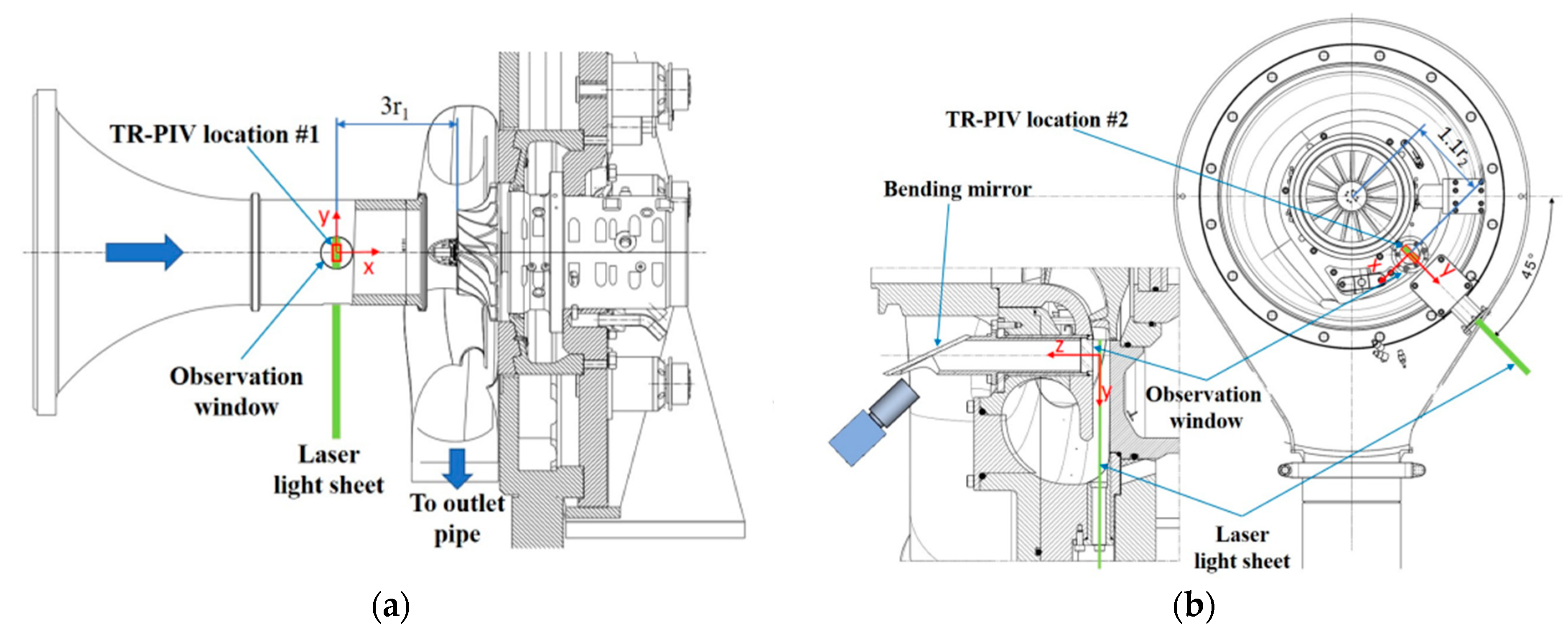

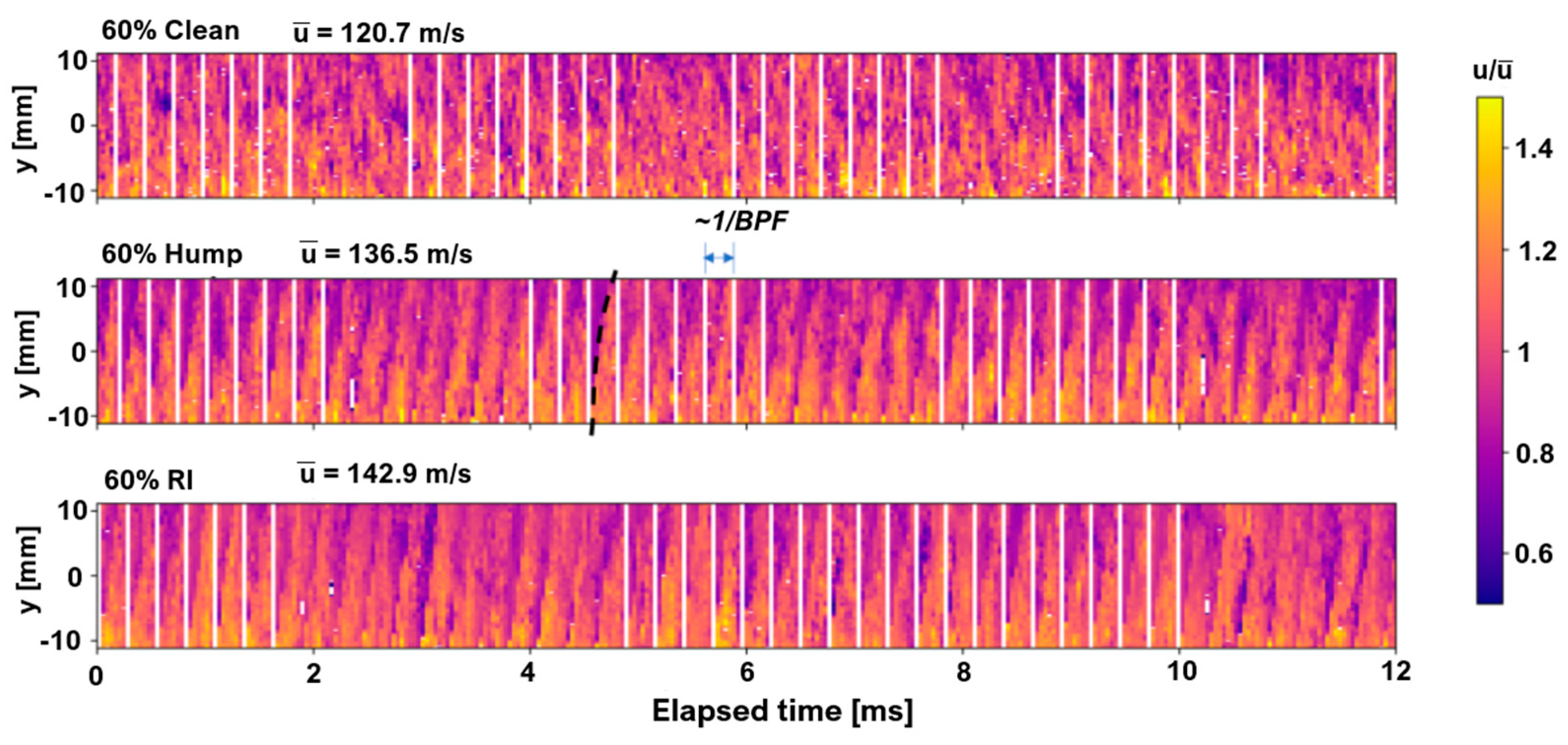

| DLR–Liebherr SSCC [70] | Single-stage, 15 unshrouded backswept blades, vaneless diffuser, asymmetric volute; aircraft AC system | 19 Kulite XCE-062 pressure transducers; Dewetron 808 DAQ; IRIG-B timing; TR-PIV | Flush-mounted in impeller casing, 3 meridional positions; PIV upstream (3.0r1) and downstream (1.1r2) | Pressure: 0.07–0.12 mbar resolution, 200 kHz, 150 kHz BW; PIV: 54 kHz frame rate, 16–64 px interrogation windows | Detection of rotating instabilities (RI); mode-locked behavior near surge; low-frequency coherence between pressure and velocity |

| Industrial Centrifugal Compressor (Sewage System) [71] | Single-stage, vaneless diffuser, 180 kW, 18,300 rpm, PR max 1.88 | Kulite XCE-093 dynamic pressure transducers, thermocouples; NI 9215 + DAQ-9178 | 7 radial locations, circumferentially distributed across impeller + diffuser | Pressure: 0–300 kPa, 0.05% accuracy, 20 kHz sampling | Three-lobe rotating stall mode at ~30.8% impeller speed; tip leakage amplified instability |

| High-Speed Turbocharger Centrifugal Compressor [72] | Single-stage, vaneless diffuser, high-speed (185,000 rpm) | Kulite pressure probes, fast-response thermocouples, ICP microphones; DEWEsoft DAQ | P1/T1 at impeller inlet (280°/200°), P2/T2 mid-diffuser (50°/110°); microphones near shroud (S1) and inlet duct (S2) | Pressure and temperature: 50 kHz; microphones: 50 kHz, low-pass 15% shaft freq | SD slope of dynamic pressure rises near surge; temperature variance most effective for surge detection; microphones less reliable unfiltered |

| CSTAR—Purdue University [73] | Low-specific-speed axi-centrifugal compressor; design corrected speed 22,500 RPM; PR ≈ 3; aeroengine research stage | T-type thermocouples; total temperature rakes; Scanivalve DSAs; LDV system for impeller-exit flow | Temperature rakes at impeller inlet, diffuser inlet, and turn-to-axial exit; pressure taps along impeller, diffuser, and turn-to-axial (spanwise + circumferential); LDV optical access at impeller exit | Steady + transient temperature/pressure sampling via Scanivalve/DAQ; LDV for velocity field; spatially distributed static/total pressure measurements | Incidence increases as flow reduces; positive incidence improves diffuser performance; leading-edge vanes highly loaded near surge; spike-type stall originates in vaneless space; unsteady loading governs vane failure |

| Two-Stage Electric Compressor for Fuel Cells [74] | Two-stage, high-speed, >100 kW | G.R.A.S. 40PH microphones, KISTLER triaxial accelerometers; HEAD ArtemiS SUITE | Microphones: first/second stage inlets/outlets, 1 m distance, 45° offset; accelerometers on motor, ducts, compressor surfaces | Microphones: 20–20,000 Hz, 48 kHz sampling; accelerometers: 20–10,000 Hz, 48 kHz | SPL growth (20–40% RSF) predicted rotating stall 1.5–3 s in advance; surge model validated (<1.95% error) |

| Purdue SSCC Facility [76] | Honeywell single-stage centrifugal compressor for diffuser/stage performance studies | Total pressure and temperature probes; static taps; 2 inlet thermocouples; fast-response pressure transducers | Probes at stations 0 (inlet), 5 (diffuser exit), 6 (deswirl exit); static taps along impeller–diffuser–deswirl; thermocouples 180° apart upstream of impeller; unsteady sensors distributed through flow path | Steady-state pressure/temperature measurements; high-frequency unsteady pressure acquisition for stall/surge detection | Fast-response sensors distinguished spike-type (deep) surge in subsonic and supersonic regimes and modal-type (mild) surge near transonic inlet Mach; correlation of static pressure rise with instability onset; |

| NASA Glenn—Rolls-Royce Allison Centrifugal Compressor [77] | Single-stage, impeller + vaned diffuser; 21,789 rpm, PR 4:1, 4.54 kg/s | High-frequency dynamic pressure transducers; DPIV with particle seeding | Pressure: vaneless space + diffuser, circumferential; DPIV: optical access via periscope, four diffuser passages | Pressure: real-time monitoring of BPF; DPIV: instantaneous velocity fields | Stall inception location speed-dependent (impeller ≤ 70% speed, diffuser at design); visualized flow reversal and surge cycles |

| CSTAR—Purdue University (Airfoil vs. Wedge Diffuser Study) [78] | Centrifugal stage, design corrected speed 22,500 rpm; engine-representative Mach numbers; ABB AC motor driveline | Scanivalve DSA pressure arrays; Mensor CPT 6100 absolute transducer; Rosemount 3051C DP/absolute sensors; Omega PX319 stall sensor; T-type thermocouples; Agilent 34890A voltmeter; MAXIM DS1631U and Omega RTD cold junction sensors; CapaciSense blade-clearance system | Total pressure rakes at 30°/210° and temperature rakes at 150°/330°; static taps along shroud + circumferential taps at 99% span; bleedlines at 60°/240°; 6 capacitance probes at knee and exducer (30°, 150°, 270°) | Pressure accuracy: ± 0.05% (DSA), ±0.01% FS (Mensor), 0.14% FS (Rosemount); stall sensor < 1 ms response; thermocouples ± 0.9 °F; clearance uncertainty 4 × 10−4 in.; LabVIEW DAQ | Airfoil diffuser increased pressure recovery; tighter tip clearance improved PR/efficiency with little surge-margin effect; deswirl losses limited overall efficiency; diffuser benefits constrained by manufacturing/assembly tolerances |

| Purdue University High-Speed Centrifugal Compressor Facility [79] | Single-stage Honeywell compressor; 48,450 rpm, 50° backsweep impeller, 22 diffuser vanes | Steady and fast-response pressure transducers; total/station temperature probes; PIV | Pressure/temperature at key stations (inlet, diffuser exit, deswirl exit); PIV in diffuser | PIV: 2D planar velocity; high-speed CCD; laser-based seeding; measurement uncertainty < 1% | Spike-type deep surge at subsonic/supersonic inlet, modal mild surge at transonic inlet; 3D flow recirculation captured |

| NASA Glenn—Active and Passive Flow Control [80] | Rolls-Royce Allison design; impeller + 22-vane diffuser; 21,789 rpm, PR 4:1 | High-response pressure transducers; injection and obstruction system for flow control | Transducers along diffuser + vaneless space, circumferentially; injection nozzles and steel tubes in shroud | Real-time X-T pressure diagrams | Air injection improved surge margin 1.7 points; capped tubes increased margin 6.5 points; pressure-wave evolution tracked |

| Instrumentation Method | Test Configuration | Key Findings | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Pressure Sensors (e.g., Kulite XCE-093) | Embedded in casing surface near tip clearance; synchronized data acquisition | Captures real-time dynamic pressure fluctuations, aiding in the analysis of unstable flow structures like stall and surge | High-frequency response, precise spatial resolution | Requires advanced data acquisition systems; sensitive to installation alignment |

| Hot-Wire Anemometry | Positioned at various diffuser locations to measure velocity profiles | Provides detailed velocity measurements, useful for identifying flow separation and vortex formation | High spatial and temporal resolution | Sensitive to temperature and contamination; requires calibration |

| Laser Doppler Velocimetry (LDV) | Non-intrusive measurement across diffuser cross-sections | Offers accurate velocity vector fields, beneficial for detailed flow analysis | Non-intrusive, high spatial resolution | Expensive equipment; complex data interpretation |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Simulations | Numerical modeling of diffuser geometry and flow conditions | Predicts flow behavior, pressure recovery, and identifies potential stall zones | Cost-effective for design iterations; detailed flow insights | Requires validation with experimental data; computationally intensive |

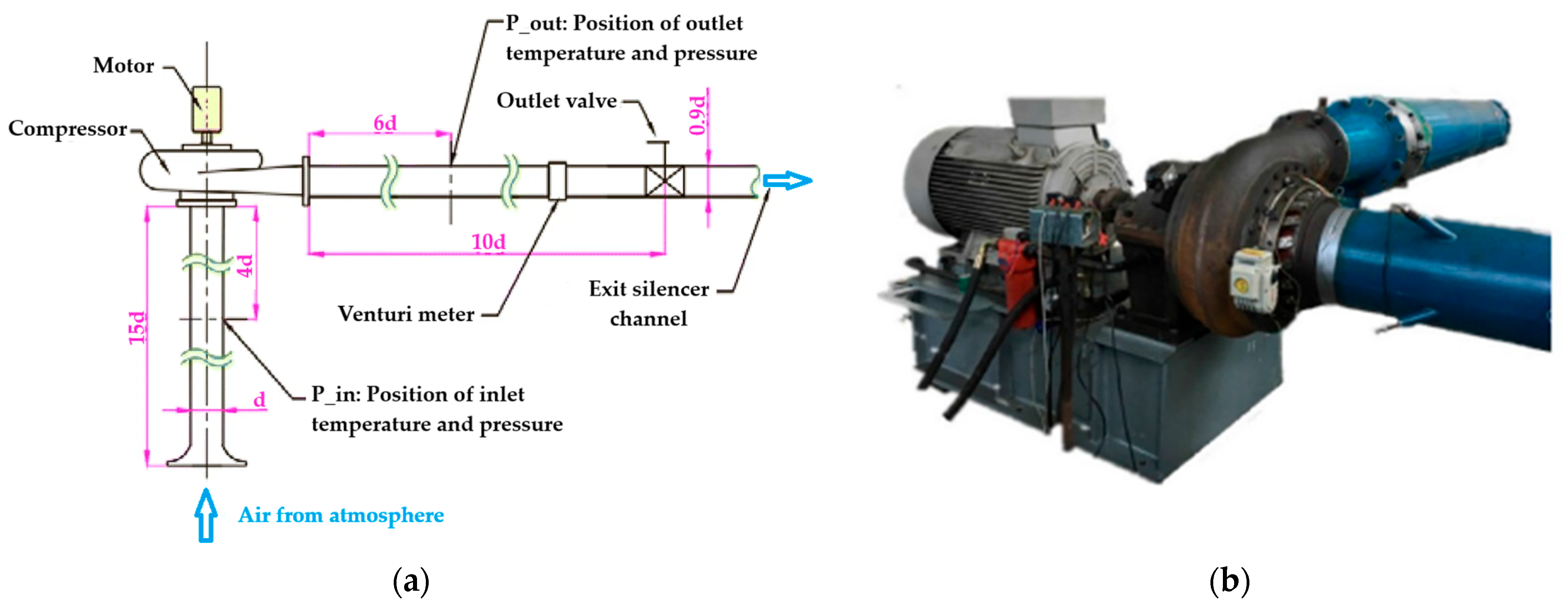

| Performance Test Rigs (e.g., Venturi flowmeter, Pitot tubes, thermocouples) | Full-scale compressor testing with controlled inlet and outlet conditions | Measures pressure ratios, flow rates, and temperatures to evaluate diffuser efficiency | Provides real-world performance data; comprehensive analysis | High setup costs; potential for measurement errors due to environmental factors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prisăcariu, E.-G.; Dumitrescu, O. Instrumentation Strategies for Monitoring Flow in Centrifugal Compressor Diffusers: Techniques and Case Studies. Sensors 2025, 25, 7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247526

Prisăcariu E-G, Dumitrescu O. Instrumentation Strategies for Monitoring Flow in Centrifugal Compressor Diffusers: Techniques and Case Studies. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247526

Chicago/Turabian StylePrisăcariu, Emilia-Georgiana, and Oana Dumitrescu. 2025. "Instrumentation Strategies for Monitoring Flow in Centrifugal Compressor Diffusers: Techniques and Case Studies" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247526

APA StylePrisăcariu, E.-G., & Dumitrescu, O. (2025). Instrumentation Strategies for Monitoring Flow in Centrifugal Compressor Diffusers: Techniques and Case Studies. Sensors, 25(24), 7526. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247526