Temperature and Strain Characterization of Tapered Fiber Bragg Gratings

Abstract

1. Introduction

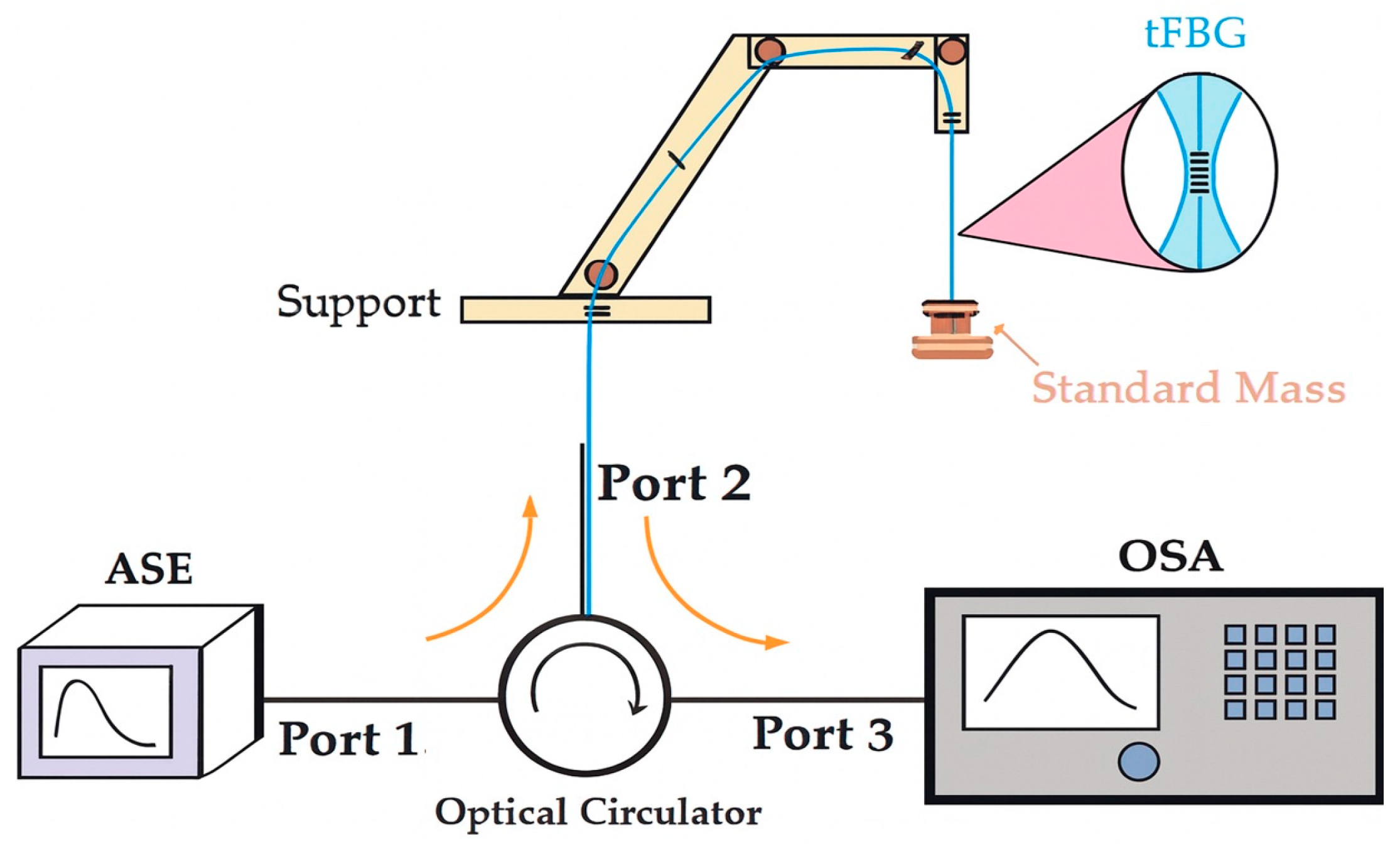

2. Materials and Methods

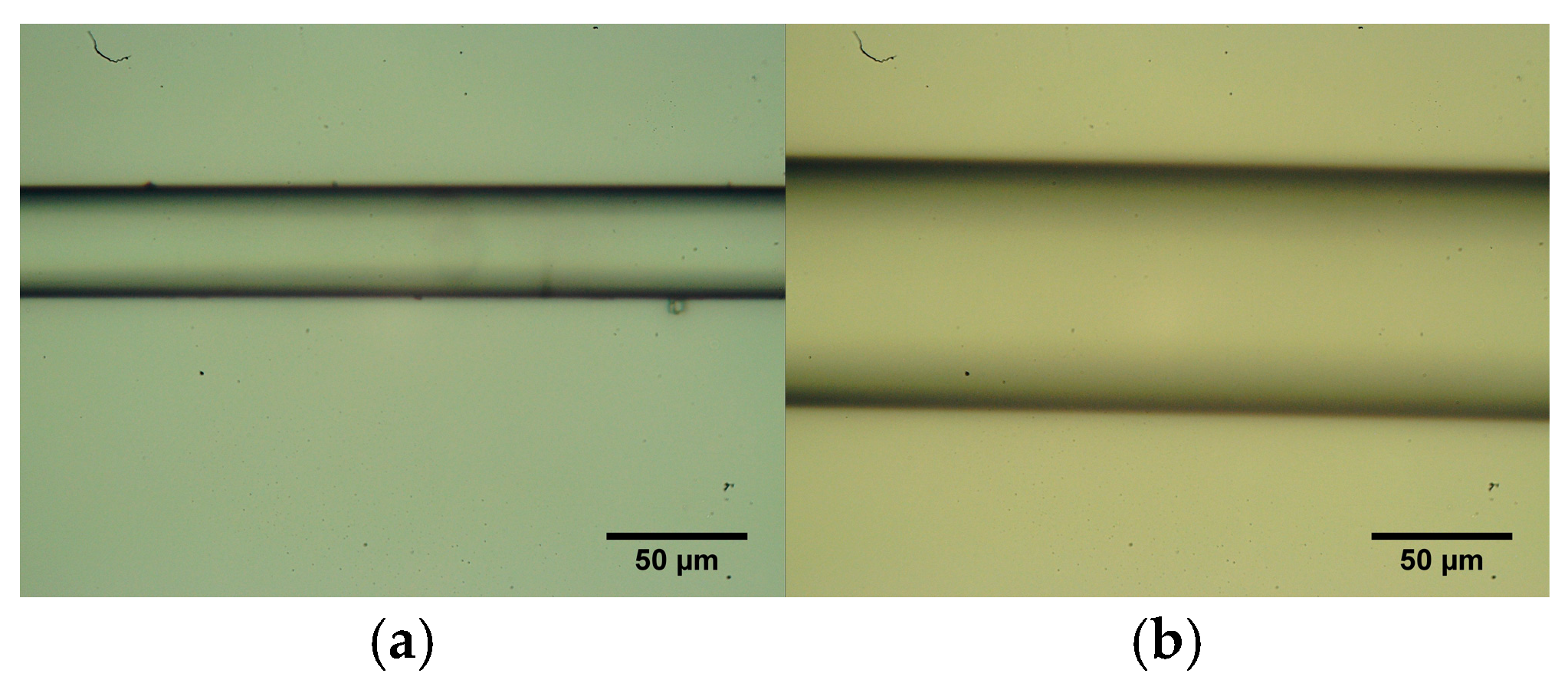

2.1. Tapered Fibers Production

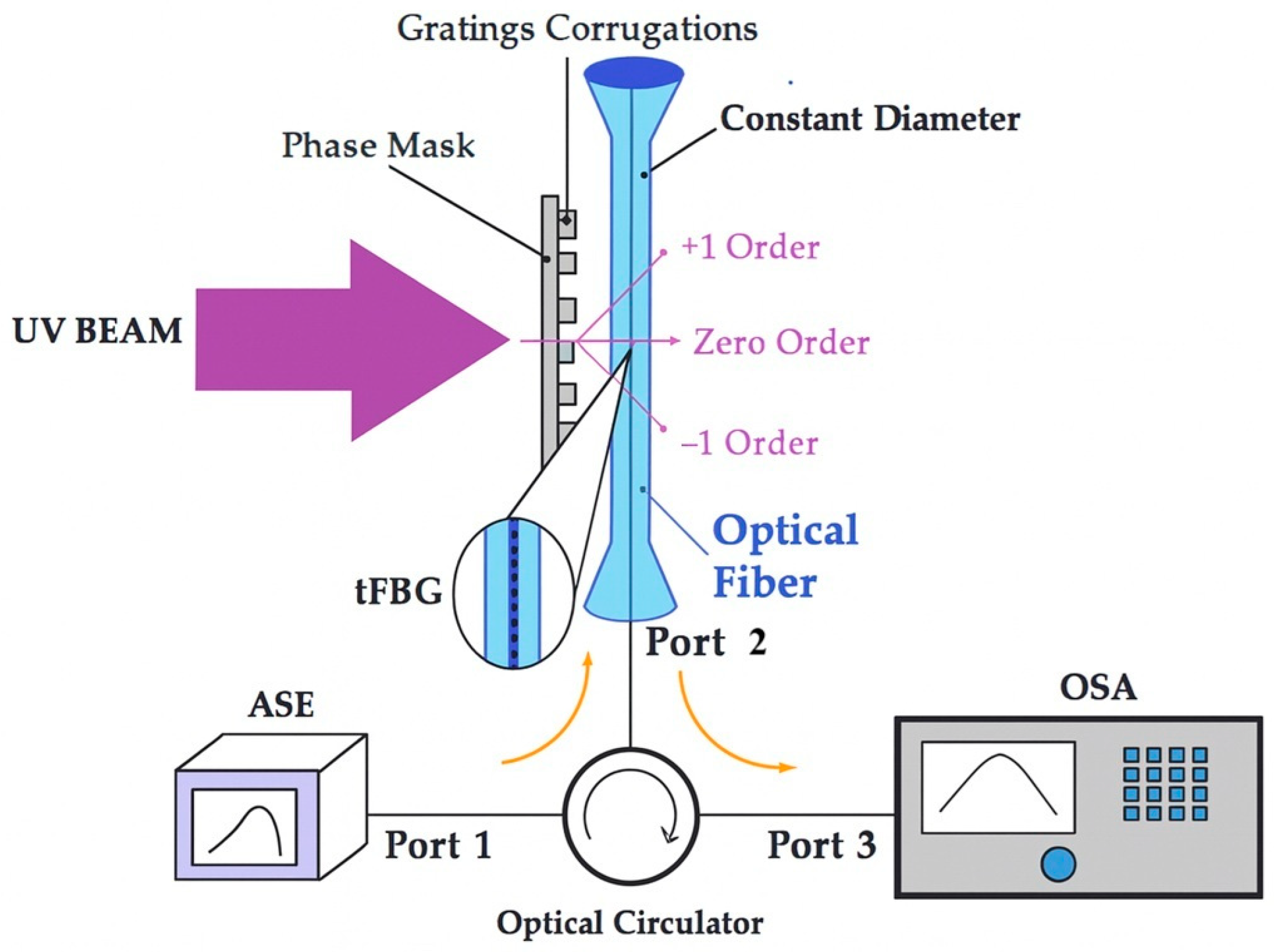

2.2. Writing Process

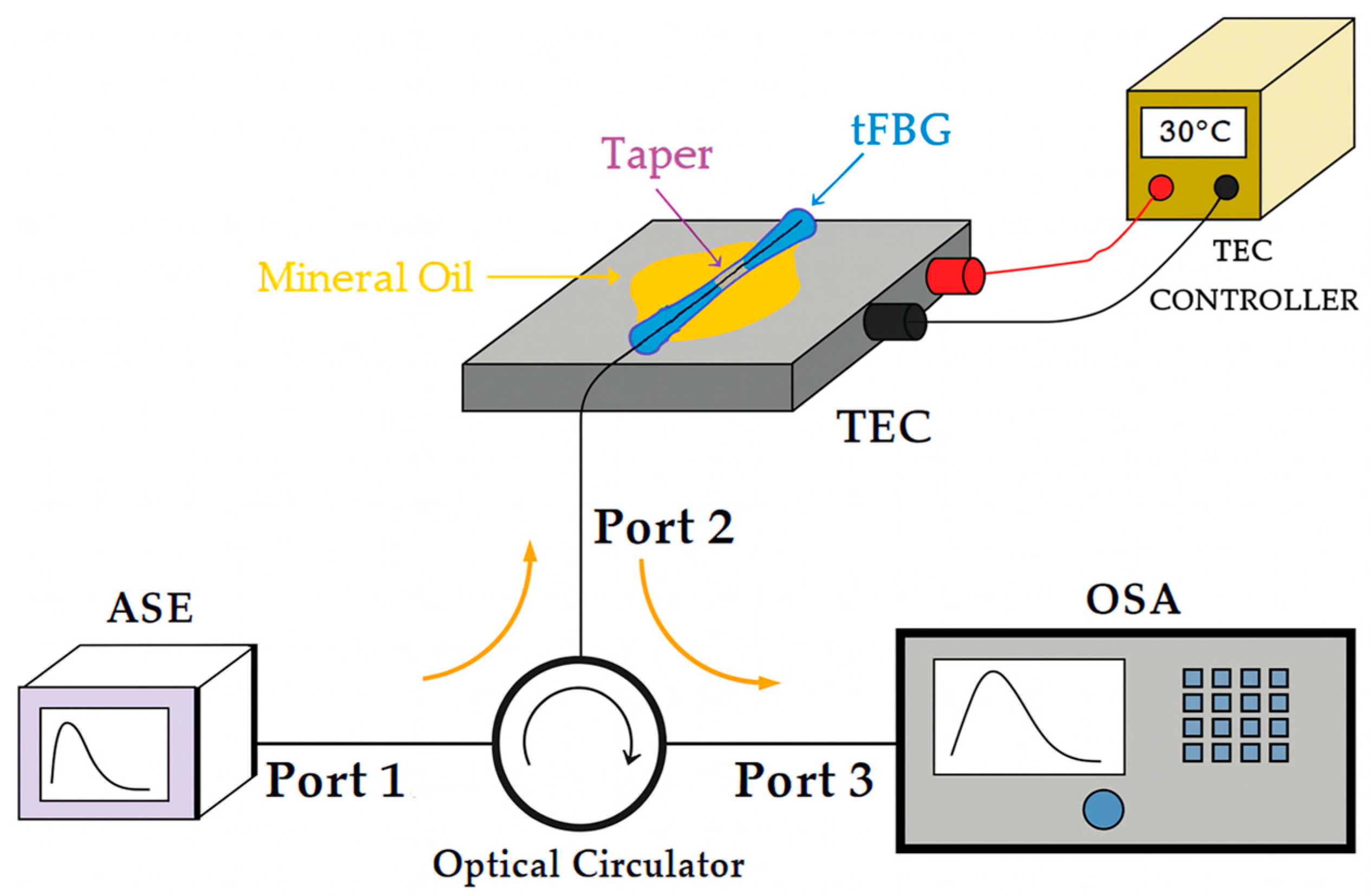

2.3. Thermal Characterization

2.4. Strain Characterization

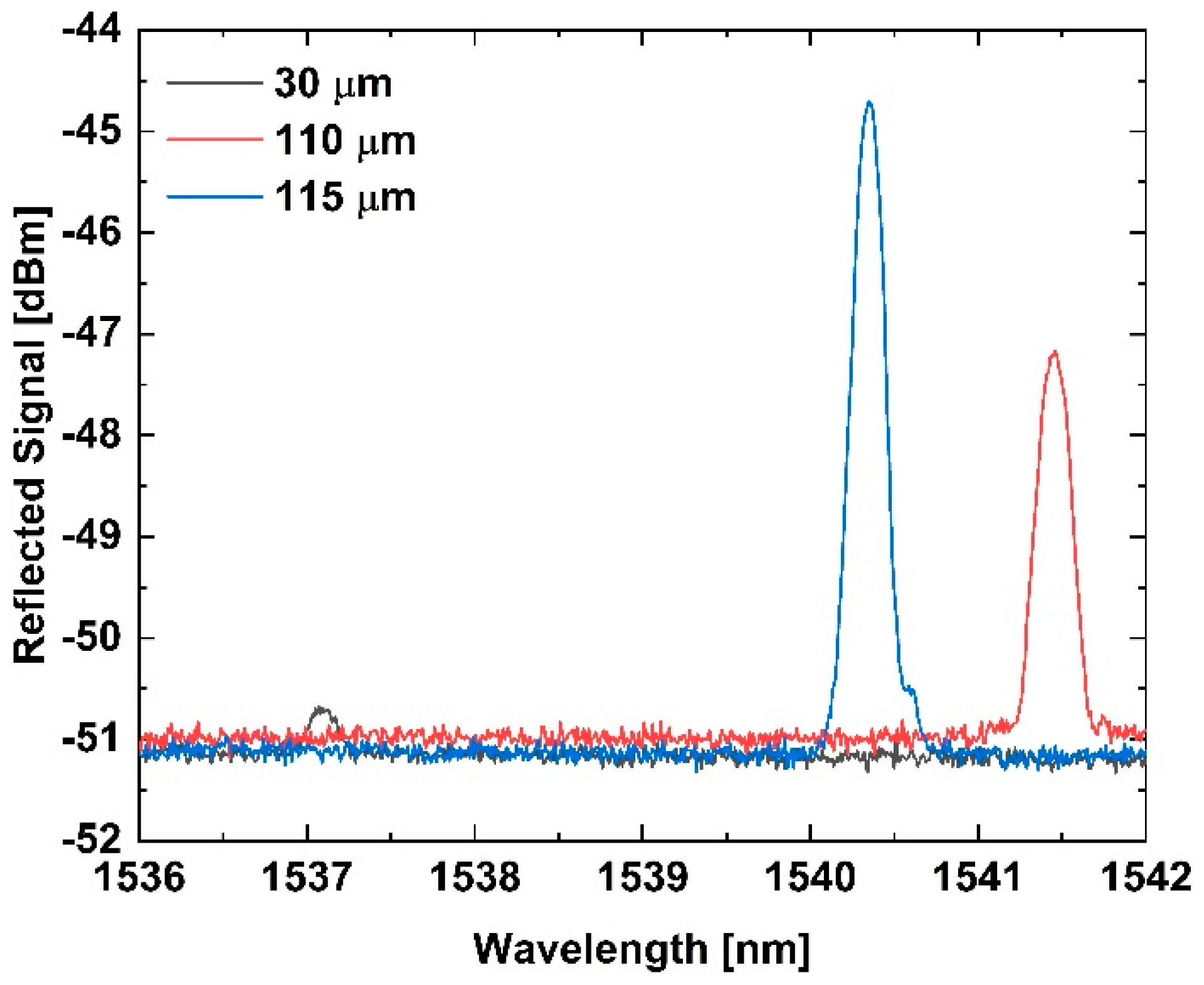

3. Results

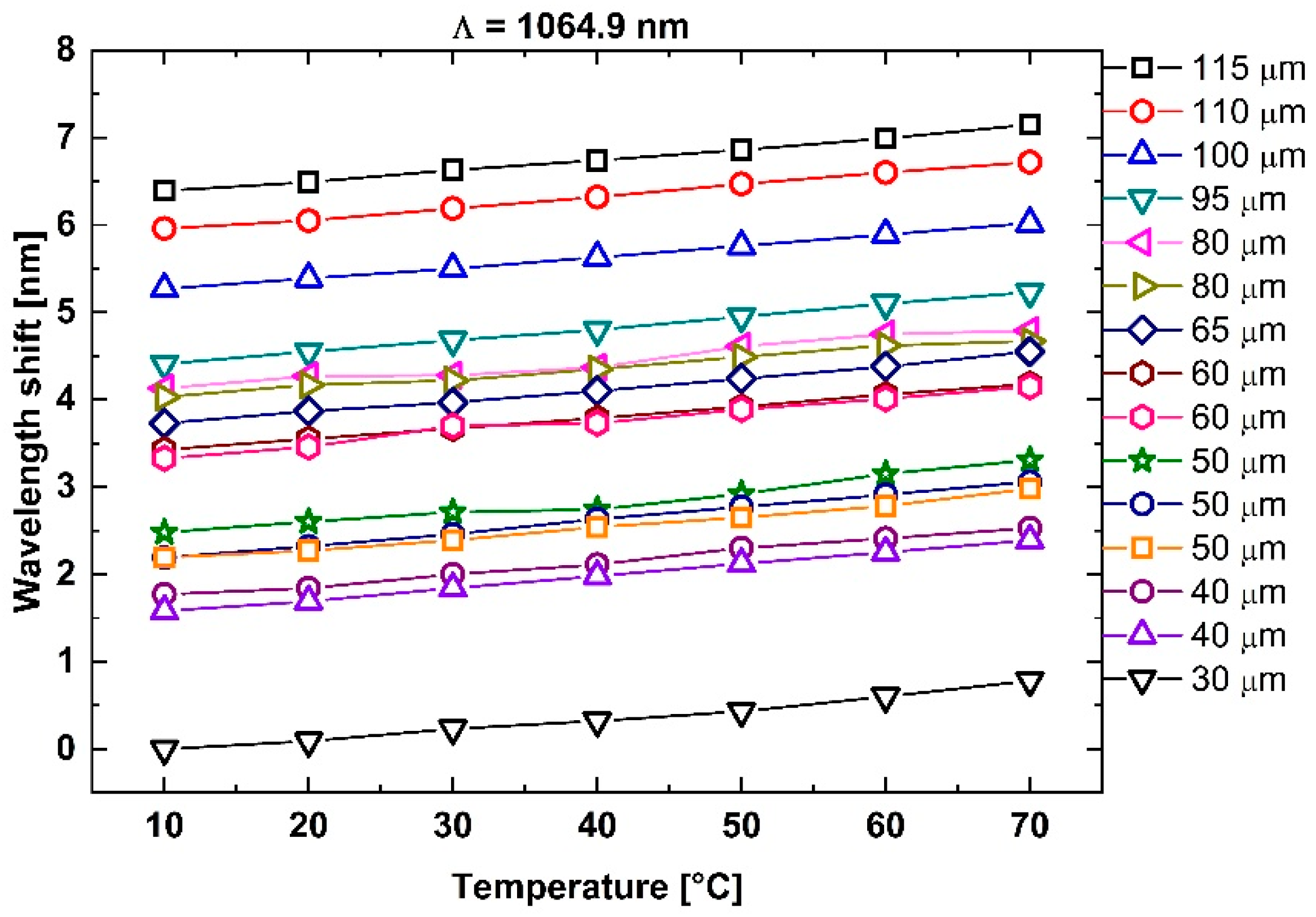

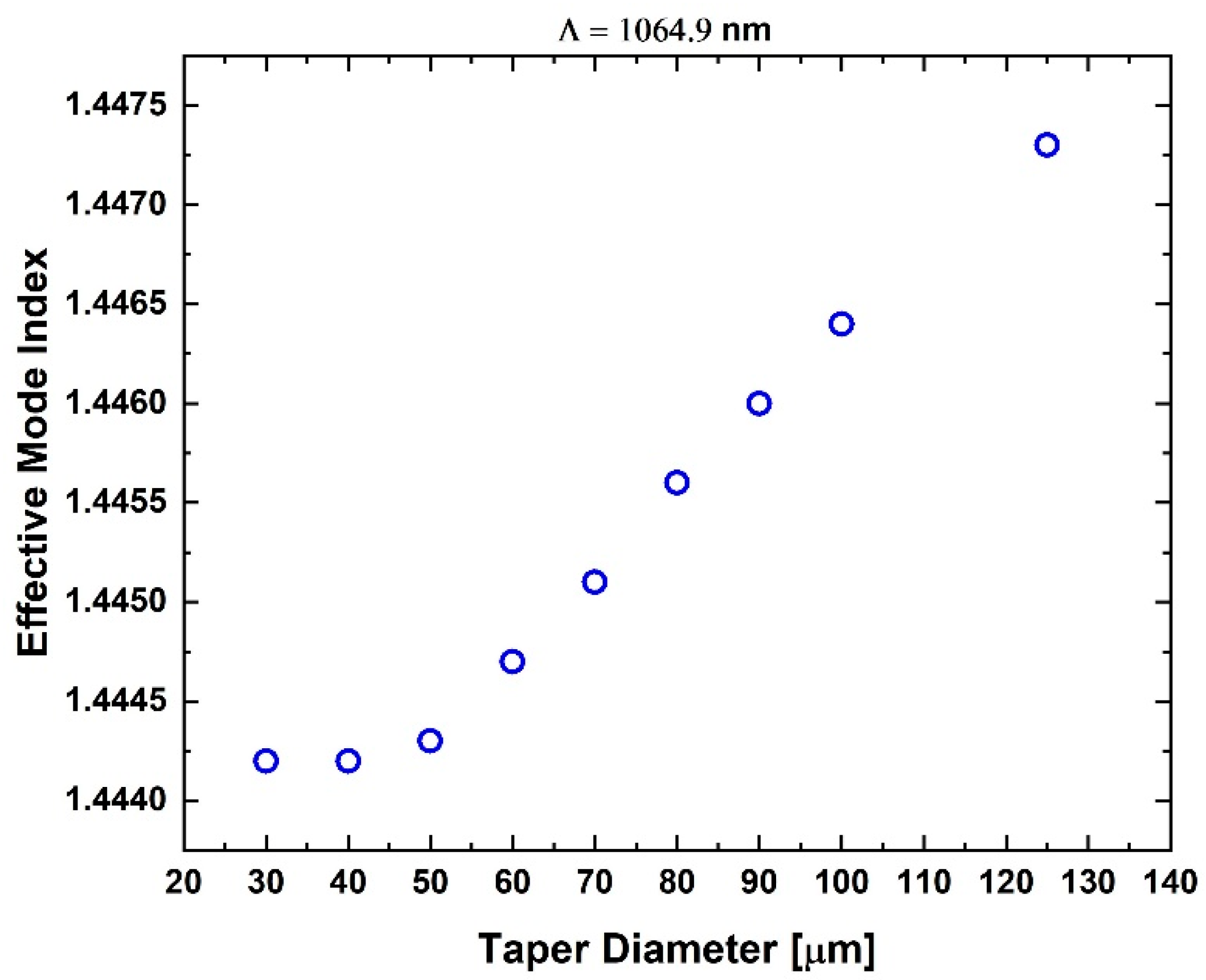

3.1. Thermal Sensitivity

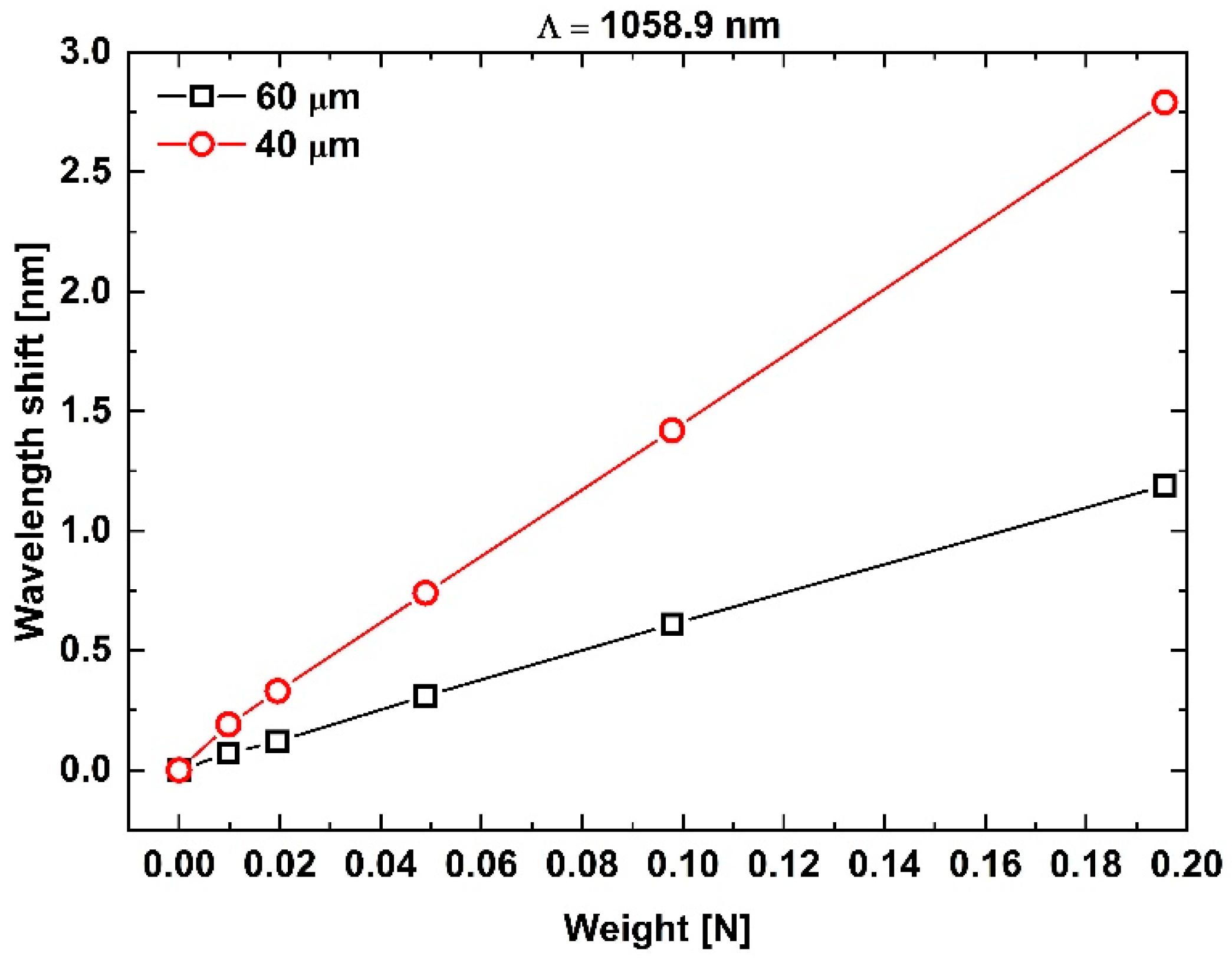

3.2. Strain Sensitivity

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASE | Amplified Spontaneous Emission |

| FBG | Fiber Bragg Grating |

| FEM | Finite Element Modeling |

| LPG | Long-Period Grating |

| OSA | Optical Spectrum Analyzer |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PM | Phase Mask |

| SHM | Structural Health Monitoring |

| SMF | Single-Mode Fiber |

| SMF-28 | Standard Telecom Single-Mode Fiber (G.652) |

| tFBG | Tapered Fiber Bragg Grating |

| TEC | Thermoelectrical Cooler |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| ΛPM | Phase Mask Pitch |

References

- Kersey, A.D.; Davis, M.A.; Patrick, H.J.; LeBlanc, M.; Koo, K.P. Fiber Grating Sensors. J. Light. Technol. 1997, 15, 1442–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.O.; Meltz, G. Fiber Bragg Grating Technology Fundamentals and Overview. J. Light. Technol. 1997, 15, 1263–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussein, A.N.D.; Qaid, M.R.T.M.; Agliullin, T.; Valeev, B.; Morozov, O.; Sakhabutdinov, A. Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors: Design, Applications, and Comparison with Other Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.O.; Fujii, Y.; Johnson, D.C.; Kawasaki, B.S. Photosensitivity in Optical Fiber Waveguides: Application to Reflection Fiber Fabrication. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1978, 32, 647–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.E.; Zhang, C.; Webb, D.J.; Kalli, K.; Argyros, A.; Large, M.C.J. Thermal response of Bragg gratings in PMMA microstructured optical fibers. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 8844–8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, F.; Zhang, B.; Dey, K.; Smith, J.D.; O’MAlley, R.J.; Huang, J. Discrimination of Temperature and Strain by Characterizing Two Femtosecond Laser-Written Coincident Sapphire Fiber Bragg Gratings for Harsh Environment Applications. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 7004309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamikawachi, R.C.; Abe, I.; Kalinowski, H.J.; Fabris, J.L.; Pinto, J.F. Nonlinear Temperature Dependence of Etched Fiber Bragg Gratings. IEEE Sens. J. 2007, 7, 1358–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiao, X.; Yang, H.; Su, D.; Li, L.; Guo, T. Sensitivity-Improved Strain Sensor over a Large Range of Temperatures Using an Etched and Regenerated Fiber Bragg Grating. Sensors 2014, 14, 18575–18582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, K.; Pavan, V.D.R.; Buddub, R.; Roy, S. Axial Force Analysis Using Half-Etched FBG Sensor. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2021, 64, 102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.L.; Ding, M.; Feng, J.; Lu, Y.Q.; Xu, F.; Brambilla, G. Microfiber-Based Bragg Gratings for Sensing Applications: A Review. Sensors 2012, 12, 8861–8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lou, J.; Tong, L. Micro/Nanofiber Optical Sensors. Photonic Sens. 2011, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, A.; Espindola, G.; Kalinowski, H.J.; Lima, J.A.S.; Paterno, A.S. Stepwise Fabrication of Arbitrary Fiber Optic Tapers. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 19893–19901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazão, O.; Salgado, H.M.; Santos, J.L. Chirped Bragg Grating in Tapered Fibers for Simultaneous Measurement of Strain and Temperature. Opt. Commun. 2005, 246, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, L.; Dong, M.; Lou, X.; Liu, F. A Temperature Fiber Sensor Based on Tapered Fiber Bragg Grating Fabricated by Femtosecond Laser. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, C.C.; Oliveira, V.; Biazoli, C.R.; Cordeiro, C.M.B.; Kalinowski, H.J. Manufacture of Tapered Fibers and FBG Writing. J. Microw. Optoelectron. Electromagn. Appl. 2018, 17, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, T.A.; Li, Y.W. The Shape of Fiber Tapers. J. Light. Technol. 1992, 10, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othonos, A.; Lee, X. Novel and Improved Methods of Writing Bragg Gratings with Phase Masks. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 1995, 7, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Ho, S.C.M. A Review of Rock Bolt Monitoring Using Smart Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V.; Vengsarkar, A.M. Optical Fiber Long-Period Grating Sensors. Opt. Lett. 1996, 21, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Liu, Y.; Shu, X. Long-Period Fiber Grating Sensors for Chemical and Biomedical Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaul, M.; Barland, J.; Cleary, J.; Cahalane, C.; McCarthy, T.; Diamond, D. Combining Remote Temperature Sensing with in-Situ Sensing to Track Marine/Freshwater Mixing Dynamics. Sensors 2016, 16, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Chen, L. Recent Progress in Distributed Fiber Optic Sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 8601–8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, K.S.; Eom, J.B.; Kim, M.J.; Rho, B.S.; Choi, H.Y. Interferometric Fiber Optic Sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 2467–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehura, H.; James, S.W.; Tatam, R.P. Temperature and Strain Discrimination Using a Single Tilted Fibre Bragg Grating. Opt. Commun. 2007, 275, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, B.; Alam, M.; Seifert, M.; Cao, H. High-resolution and broadband all-fiber spectrometers. Optica 2014, 1, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, M.-C.; Díaz-Herrera, N.; González-Cano, A. Salinity Measurement with a Plasmonic Sensor Based on Doubly Deposited Tapered Optical Fibers. Sensors 2024, 24, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korposh, S.; James, S.W.; Lee, S.-W.; Tatam, R.P. Tapered Optical Fibre Sensors: Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Sensors 2019, 19, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Tang, W.; Yan, W.; Qiu, M. Fibre tapering using plasmonic microheaters and deformation-induced pull. Light Adv. Manuf. 2023, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, H.L.; Polzik, E.S.; Appel, J. Heater Self-Calibration Technique for Shape Prediction of Fiber Tapers. J. Light. Technol. 2014, 32, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holleis, S.; Hoinkes, T.; Wuttke, C.; Schneeweiss, P.; Rauschenbeutel, A. Experimental stress–strain analysis of tapered silica optical fibers with nanofiber waist. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 163109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkjian, C.R.; Krause, J.T.; Matthewson, M.J. Strength and fatigue of silica optical fibers. J. Light. Technol. 1989, 7, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, F.; Malo, B.; Albert, J.; Johnson, D.C.; Hill, K.O.; Hibino, Y.; Abe, M.; Kawachi, M. Photosensitization of Optical Fiber and Silica on Silicon/Silica Waveguides. Opt. Lett. 1993, 18, 953–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, A.; Delepine-Lesoille, S.; Friedrich, E.; Aziri, S.; Lecieux, Y.; Leduc, D. Mechanical Properties of Optical Fiber Strain Sensing Cables under γ-Ray Irradiation and Large Strain Influence. Sensors 2020, 20, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Yu, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Xu, B. Highly Sensitive Gas Pressure Sensing with Temperature Monitoring. Sensors 2024, 24, 6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, R.M.; Cordeiro, C.M.B.; Kalinowski, H.J. Strain–Temperature Discrimination Using Multimode Interference in Tapered Fiber. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2013, 25, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podrazký, O.; Mrázek, J.; Proboštová, J.; Vytykáčová, S.; Kašík, I.; Pitrová, Š.; Jasim, A.A. Ex-Vivo Measurement of the pH in Aqueous Humor by a Tapered Fiber Sensor. Sensors 2021, 21, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| tFBG Cladding Diameter [µm] | Numbers Produced |

|---|---|

| 115 | 1 |

| 110 | 1 |

| 100 | 1 |

| 95 | 1 |

| 80 | 2 |

| 65 | 1 |

| 60 | 2 |

| 50 | 3 |

| 40 | 2 |

| 30 | 1 |

| Taper Diameter (µm) | Thermal Sensitivity (pm/°C) |

|---|---|

| 115 | 12.54 ± 0.40 |

| 95 | 13.68 ± 0.77 |

| 60 | 13.57 ± 0.40 |

| 50 | 13.04 ± 0.09 |

| 30 | 12.71 ± 0.24 |

| ΛPM1 = 1058.9 nm | |||

| Diameter [µm] | Sload [pm/N] ± σ | Sε [pm/µε] ± σ | Stemp [pm/°C] ± σ |

| 60 | 6.08 ± 0.05 | 2.99 ± 0.02 | |

| 40 | 14.10 ± 0.14 | 15.60 ± 0.15 | |

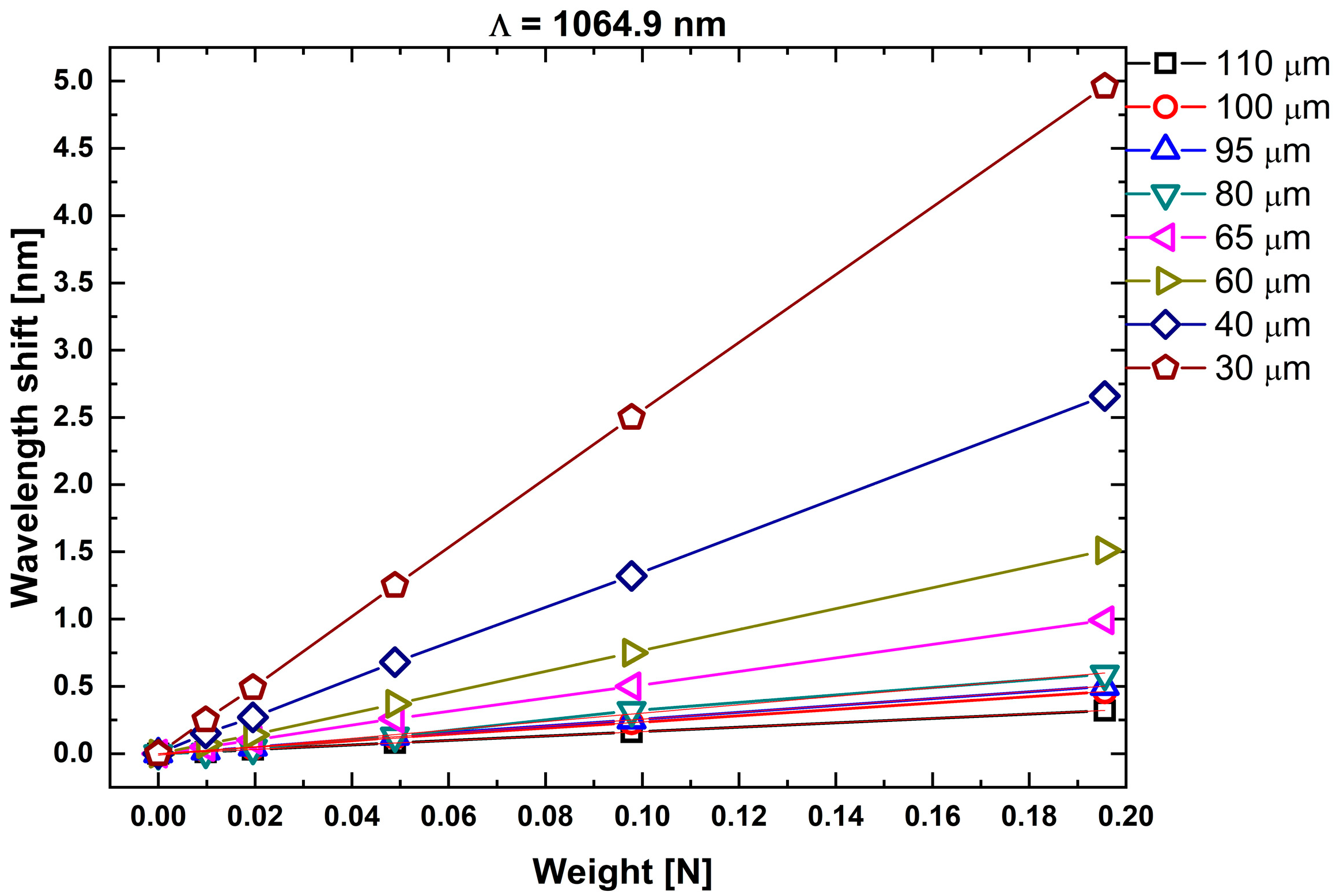

| ΛPM2 = 1064.9 nm | |||

| 110 | 1.65 ± 0.015 | 2.41 ± 0.02 | 13.07 ± 9.27 |

| 100 | 2.36 ± 0.020 | 3.35 ± 0.03 | 12.54 ± 3.17 |

| 95 | 2.56 ± 0.021 | 3.62 ± 0.03 | 13.68 ± 5.64 |

| 80 | 3.12 ± 0.100 | 4.55 ± 0.15 | 11.68 ± 9.80 |

| 65 | 5.06 ± 0.030 | 6.25 ± 0.04 | 13.39 ± 3.40 |

| 60 | 7.74 ± 0.030 | 11.33 ± 0.04 | 13.57 ± 2.93 |

| 40 | 13.54 ± 0.060 | 14.99 ± 0.07 | 13.29 ± 2.62 |

| 30 | 25.38 ± 0.060 | 28.84 ± 0.05 | 12.71 ± 1.85 |

| Reference | Method/Structure | Waist (µm) | Strain Sensitivity | Temperature Sensitivity | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work (2025) | UV phase-mask tFBG on SMF-28 | 30 | 28.84 pm/µε (or 25.38 pm/N) | 12.5 pm/°C | Stable, low-cost, reproducible |

| Wang et al. (2014) [8] | Etched + regenerated FBG | ~12 | ~6.8 pm/µε (enhanced vs. standard FBG) | ~10.3 pm/°C | Chemical etching + regeneration |

| Zhang et al. (2018) [14] | Femtosecond written tapered FBG | 25 | Not strain-focused | 9.6–12.3 pm/°C | Temperature sensor; fs-laser inscription |

| Kou et al. (2012) [10] | Microfiber Bragg | 2–10 | Up to ~150–500 pm/µε depending on device | 15–25 pm/°C (varies) | Microfiber regime: strong evanescent field |

| Dey et al. (2021) [9] | Half-etched FBG | ~12 | 1.96 nm/N = 1960 pm/N | ~10–12 pm/°C | Very high force sensitivity using cross-section reduction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Moura, C.C.; de Oliveira, V.; Kalinowski, H.J.; Biazoli, C.R. Temperature and Strain Characterization of Tapered Fiber Bragg Gratings. Sensors 2025, 25, 7520. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247520

de Moura CC, de Oliveira V, Kalinowski HJ, Biazoli CR. Temperature and Strain Characterization of Tapered Fiber Bragg Gratings. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7520. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247520

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Moura, Camila Carvalho, Valmir de Oliveira, Hypolito José Kalinowski, and Claudecir Ricardo Biazoli. 2025. "Temperature and Strain Characterization of Tapered Fiber Bragg Gratings" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7520. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247520

APA Stylede Moura, C. C., de Oliveira, V., Kalinowski, H. J., & Biazoli, C. R. (2025). Temperature and Strain Characterization of Tapered Fiber Bragg Gratings. Sensors, 25(24), 7520. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247520