Enhanced DeepLabV3+ with OBIA and Lightweight Attention for Accurate and Efficient Tree Species Classification in UAV Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Traditional Classification Methods and OBIA

2.2. Deep Learning in Semantic Segmentation

2.3. Attention Mechanisms and Lightweight Networks

3. Materials and Methods

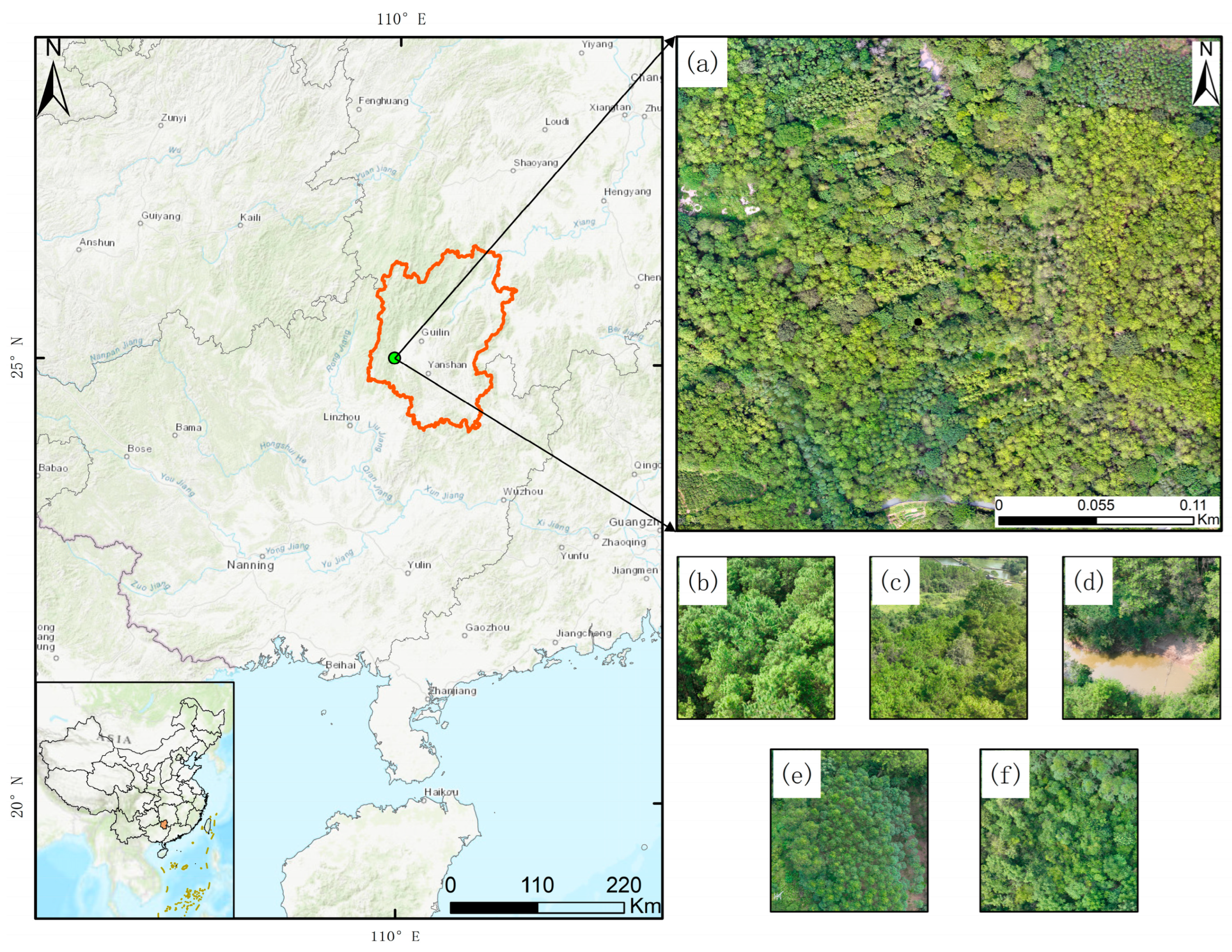

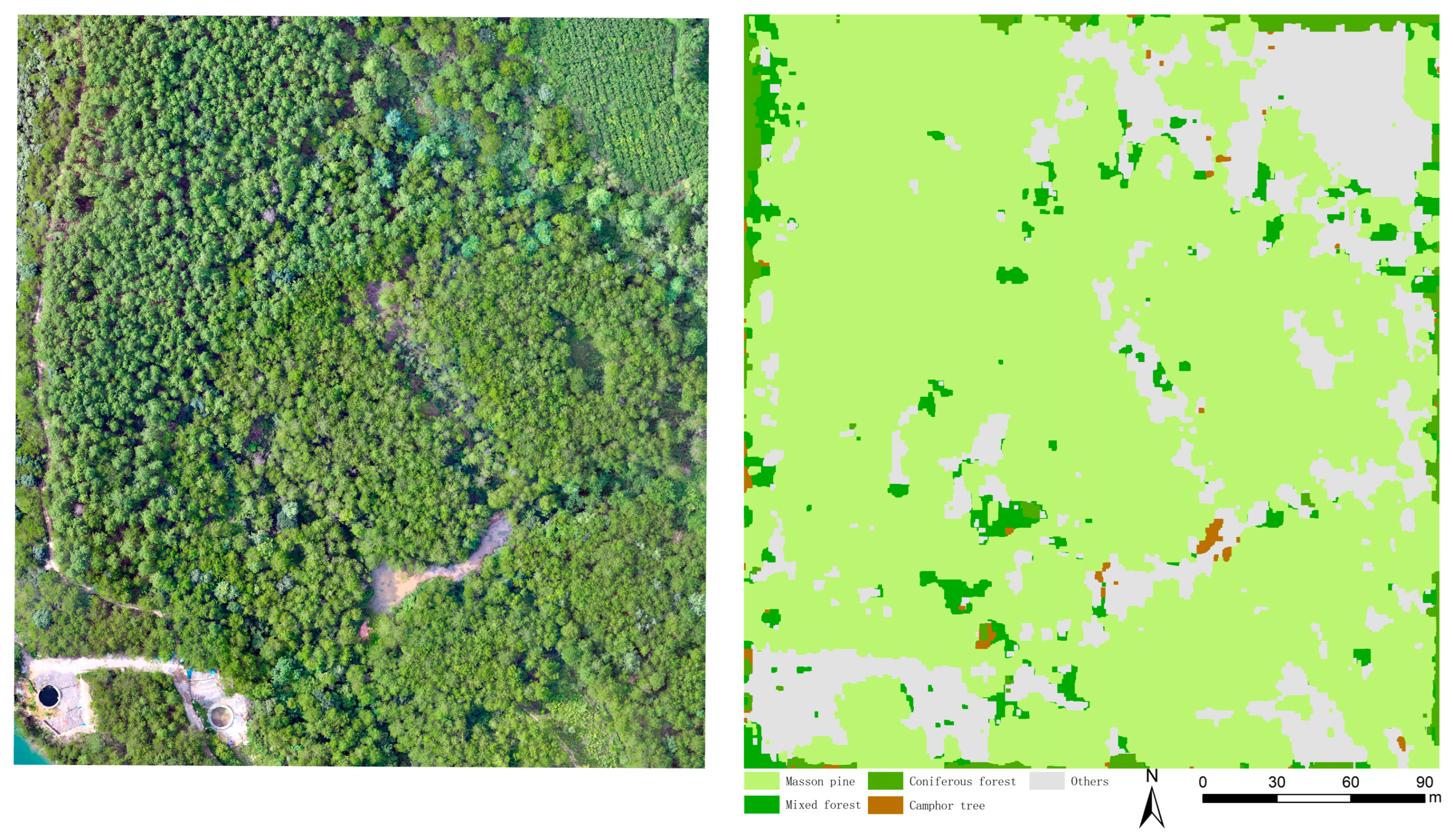

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

3.3. Methods

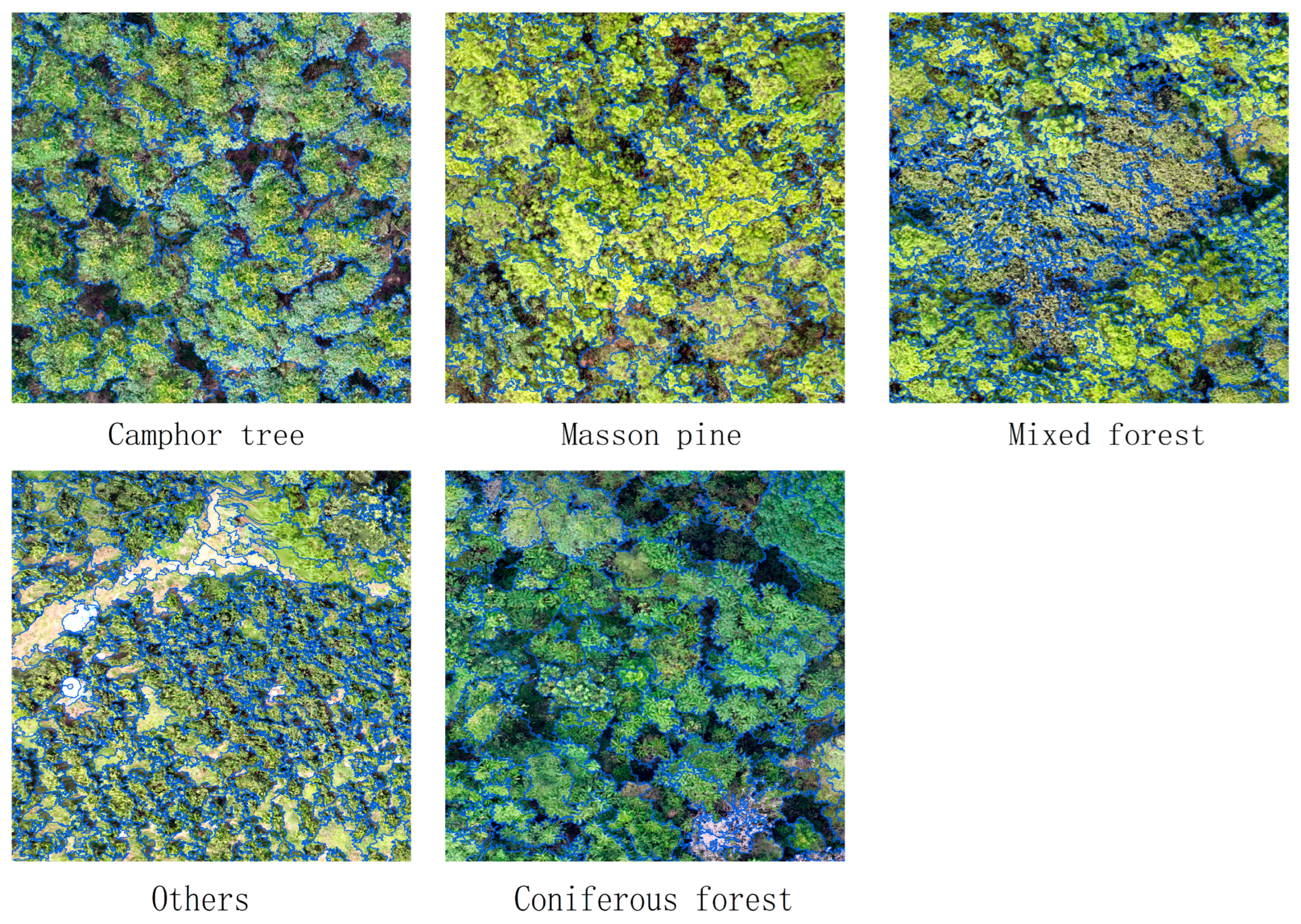

3.3.1. Multiscale Segmentation Algorithm

3.3.2. Feature Selector

3.3.3. Label Optimization by RFVI Method Combining Random Forest Classification with Visual Interpretation

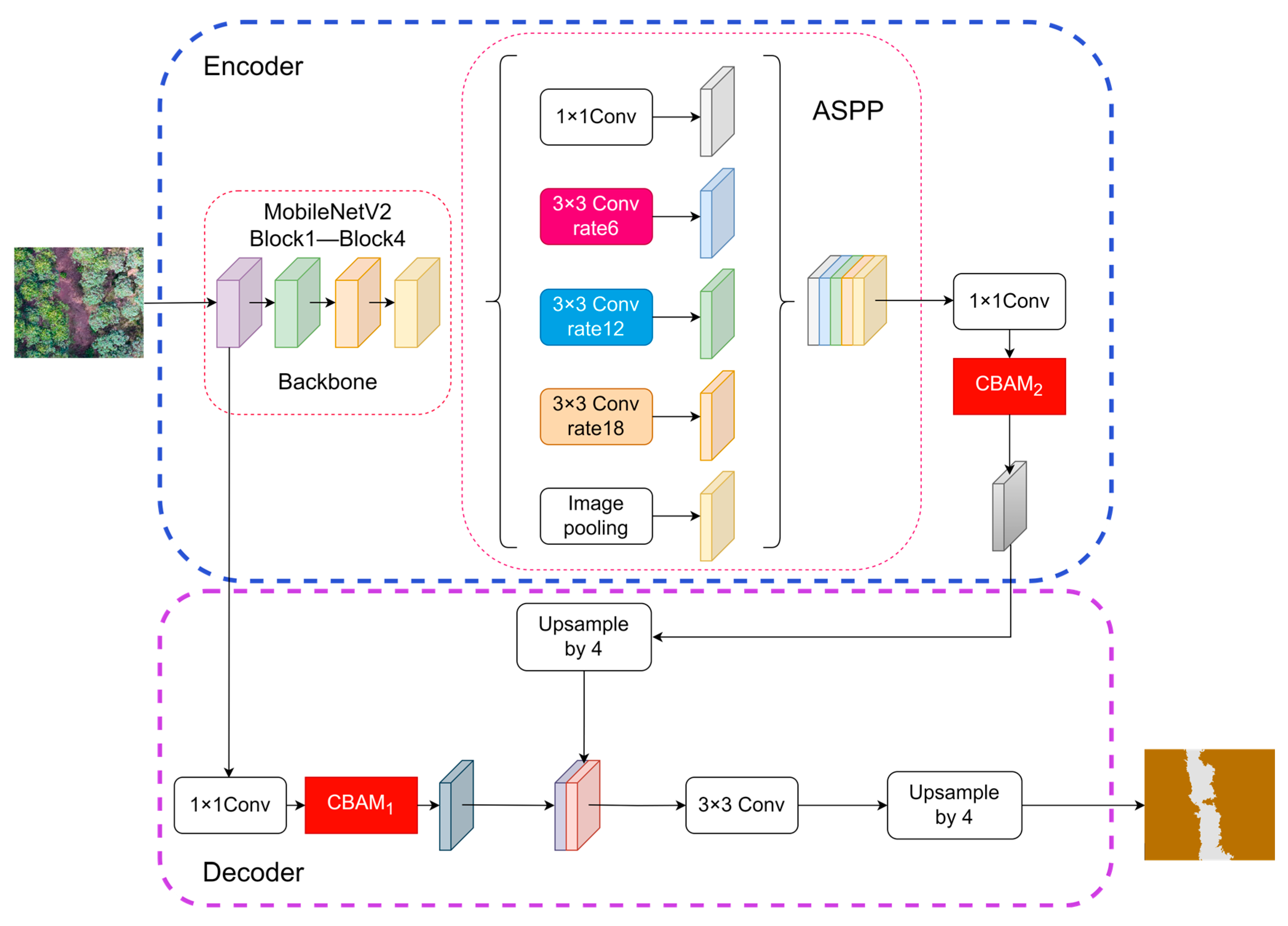

3.3.4. DeepLabV3+ Semantic Segmentation Method

3.3.5. Improved DeepLabV3+ Semantic Segmentation Method

Improvement of the Backbone Network

Introduction of the Attention Mechanism Module

3.3.6. Experimental Environment and Accuracy Evaluation Indicators

4. Results

4.1. Multiscale Segmentation of UAV Images

4.2. Feature Optimization

4.3. Label Optimization by RFVI Method Label Optimization

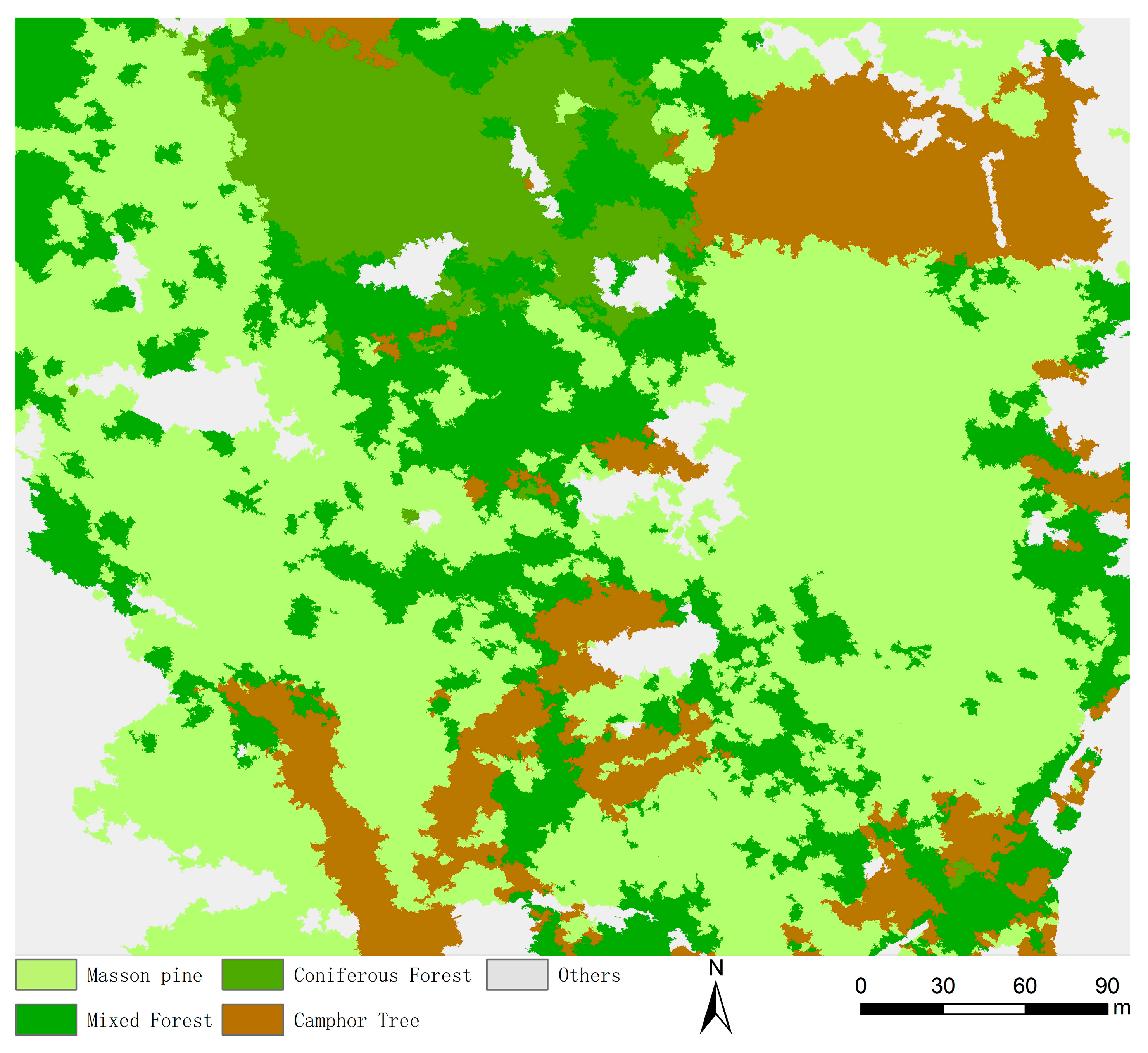

4.4. Results of the Improved DeepLabV3+ Model

4.4.1. Ablation Experiment

4.4.2. Experimental Results of Different Semantic Segmentation Models Comparison Results of Different Semantic Segmentation Models

4.4.3. Model Generalization Ability Verification

5. Discussion

5.1. Determination of Segmentation Scale and Features

5.2. Label Optimization by RFVI Method

5.3. Performance Analysis of the Improved DeepLabV3+ Model

5.4. Shortcomings and Prospects

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Through integrated analysis of multiscale segmentation algorithms and RFECV, optimal OBIA scale parameters and feature combinations were determined, substantially mitigating the impact of manual intervention on classification outcomes.

- (2)

- The RFVI method was developed to optimize labels, enhancing both production efficiency and annotation quality. This approach established an efficient and reliable label optimization pipeline, providing a high-quality data foundation for deep learning model training.

- (3)

- The model achieved breakthrough performance via lightweight design and enhanced attention mechanisms. The improved model attained an OA of 94.91% and a Kappa of 92.89%, representing increases of 2.91% and 4.11% over the original DeepLabV3+. Compared to U-Net and PSPNet, an OA improved by 2.0% and 4.55%, respectively, while model parameters were drastically reduced to 5.91 M (a 78.7% decrease). This demonstrated a high-precision, efficient, lightweight solution for UAV-based tree species segmentation in complex forest images.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Ji, X. Exploring the Optimal Feature Combination of Tree Species Classification by Fusing Multi-Feature and Multi-Temporal Sentinel-2 Data in Changbai Mountain. Forests 2022, 13, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yin, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, D.; Ferreira, M.P.; Yan, W.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, D.; Tan, S.; Nie, S. Tree-level carbon stock estimations across diverse species using multi-source remote sensing integration. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ren, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.; Hong, S.; Hong, W.; He, X. Spatiotemporal patterns of urban forest carbon sequestration capacity: Implications for urban CO2 emission mitigation during China’s rapid urbanization. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Ma, R.; Zhai, J.; Du, J.; Bai, J.; Zhang, W. Stand spatial structure is more important than species diversity in enhancing the carbon sink of fragile natural secondary forest. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ren, C.; Wang, Z.; Jia, M.; Yu, W.; Ren, H.; Xia, C. Evaluating the potential of Sentinel-2 time series imagery and machine learning for tree species classification in a mountainous forest. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wu, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T. Mapping Forest Tree Species Using Sentinel-2 Time Series by Taking into Account Tree Age. Forests 2024, 15, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Xu, S. TCSNet: A New Individual Tree Crown Segmentation Network from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images. Forests 2024, 15, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Ferlian, O.; Eisenhauer, N.; Feilhauer, H.; Kattenborn, T. From simple labels to semantic image segmentation: Leveraging citizen science plant photographs for tree species mapping in drone imagery. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 2909–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.E. Pixel- and object-based multispectral classification of forest tree species from small unmanned aerial vehicles. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2018, 6, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Lai, R. Extraction of Broad-Leaved Tree Crown Based on UAV Visible Images and OBIA-RF Model: A Case Study for Chinese Olive Trees. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouret, F.; Morin, D.; Planells, M.; Vincent-Barbaroux, C. Tree Species Classification at the Pixel Level Using Deep Learning and Multispectral Time Series in an Imbalanced Context. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Sawut, M.; Cui, J.; Hu, X.; Xue, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Rouzi, A.; Ye, X.; Xilike, A. Object-oriented multi-scale segmentation and multi-feature fusion-based method for identifying typical fruit trees in arid regions using Sentinel-1/2 satellite images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhang, L. Scale-aware deep reinforcement learning for high resolution remote sensing imagery classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 209, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Gao, X.; Shi, W. Advances and challenges in deep learning-based change detection for remote sensing images: A review through various learning paradigms. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Yan, P. An improved semantic segmentation algorithm for high-resolution remote sensing images based on DeepLabv3+. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zi, J.; Xu, F.; Chen, F. Multiscale feature fusion and enhancement in a transformer for the fine-grained visual classification of tree species. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 86, 103029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dong, Y.; Xu, N.; Xu, F.; Mou, C.; Chen, F. Image Classification of Tree Species in Relatives Based on Dual-Branch Vision Transformer. Forests 2024, 15, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; He, F.; Zhang, X. To Identify Tree Species with Highly Similar Leaves Based on a Novel Attention Mechanism for CNN. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 163277–163286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lu, C.; Zhou, T.; Wu, J.; Feng, H. A 3D-2DCNN-CA approach for enhanced classification of hickory tree species using UAV-based hyperspectral imaging. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Bian, L.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Ge, Y. Poplar seedling varieties and drought stress classification based on multi-source, time-series data and deep learning. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 118905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Sheng, Y.; Tian, W.; Ren, Y. A tree species classification model based on improved YOLOv7 for shelterbelts. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1265025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jiang, S.; Xue, J.; Ye, S.; Jia, S. Texture-aware self-attention model for hyperspectral tree species classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 62, 5502215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jin, Q.; Li, J.; Li, L.; He, C.; Huang, Y.; Yao, Y. Policy factors impact analysis based on remote sensing data and the CLUE-S model in the Lijiang River Basin, China. Catena 2017, 158, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Ma, J.; Mo, Y.; Yang, H. GIS-Based Watershed Unit Forest Landscape Visual Quality Assessment in Yangshuo Section of Lijiang River Basin, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Fu, B.; Chen, J.; He, W. Impacts of land use change on ecosystem service value in Lijiang River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 46100–46115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Chen, D.M. Optimization in multi-scale segmentation of high-resolution satellite images for artificial feature recognition. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 4625–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguţ, L.; Csillik, O.; Eisank, C.; Tiede, D. Automated parameterisation for multi-scale image segmentation on multiple layers. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 88, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zheng, D.; Wu, Z.; Song, H.; Zhang, X. Prediction of buckwheat maturity in UAV-RGB images based on recursive feature elimination cross-validation: A case study in Jinzhong, Northern China. Plants 2022, 11, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Lan, Y.; Ling, M.; Huang, Q.; Li, H.; Han, X.; Yi, S. Explainable machine learning-based fractional vegetation cover inversion and performance optimization—A case study of an alpine grassland on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Lin, W.; Liu, H.; Ma, N.; Liu, K.; Cao, R.; Wang, T.; Ren, Z. Identification of tree species based on the fusion of UAV hyperspectral image and LiDAR data in a coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest in Northeast China. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 964769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Chen, Z.Z.; Huang, R.J.; You, H.T.; Han, X.W.; Yue, T.; Zhou, G.Q. The Effects of Spatial Resolution and Resampling on the Classification Accuracy of Wetland Vegetation Species and Ground Objects: A Study Based on High Spatial Resolution UAV Images. Drones 2023, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.P.; De Almeida, D.R.A.; de Almeida Papa, D.; Minervino, J.B.S.; Veras, H.F.P.; Formighieri, A.; Santos, C.A.N.; Ferreira, M.A.D.; Figueiredo, E.O.; Ferreira, E.J.L. Individual tree detection and species classification of Amazonian palms using UAV images and deep learning. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 475, 118397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.-O.; Liu, M. A multilevel multimodal fusion transformer for remote sensing semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5403215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, W.; Qian, X.; Yan, W. Progressive adjacent-layer coordination symmetric cascade network for semantic segmentation of multimodal remote sensing images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šćepanović, S.; Antropov, O.; Laurila, P.; Rauste, Y.; Ignatenko, V.; Praks, J. Wide-area land cover mapping with Sentinel-1 imagery using deep learning semantic segmentation models. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 10357–10374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Xue, C.; Shao, Y.; Chen, K.; Xiong, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, L. Semantic Segmentation of Litchi Branches Using DeepLabV3+ Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164546–164555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, Y.S. Transparent conductive electrodes based on graphene-related materials. Micromachines 2018, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Peng, J.; Sun, W. Spatial–Spectral Squeeze-and-Excitation Residual Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, R.; Vaichole, T.S.; Kulkarni, S.K.; Yadav, O.; Khan, F. Eff2Net: An efficient channel attention-based convolutional neural network for skin disease classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 73, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tian, X.M.; Chai, G.Q.; Zhang, X.L.; Chen, E.R. A New CBAM-P-Net Model for Few-Shot Forest Species Classification Using Airborne Hyperspectral Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.J.; Li, X.J.; Mao, F.J.; Zhou, L.; Xuan, J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Yu, J.C.; Song, M.X.; Huang, L.; Du, H.Q. A Deep Learning Network for Individual Tree Segmentation in UAV Images with a Coupled CSPNet and Attention Mechanism. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, D.; Napoleone, F.; Cannucci, S.; Alleaume, S.; Valentini, E.; Casoli, E.; Burrascano, S. Integrating low-altitude drone based-imagery and OBIA for mapping and manage semi natural grassland habitats. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, A.; Franssen, J.; Lapierre, J.-F.; Maranger, R. High-resolution broad-scale mapping of soil parent material using object-based image analysis (OBIA) of LiDAR elevation data. Catena 2020, 188, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Morais, R.; Peres, E.; Sousa, J.J. Vineyard classification using OBIA on UAV-based RGB and multispectral data: A case study in different wine regions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 196, 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.R.; Guzman, C.; Andreo, V. Using VHR satellite imagery, OBIA and landscape metrics to improve mosquito surveillance in urban areas. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pinho, C.M.D.; Fonseca, L.M.G.; Korting, T.S.; De Almeida, C.M.; Kux, H.J.H. Land-cover classification of an intra-urban environment using high-resolution images and object-based image analysis. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 5973–5995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Ye, Z.; Deng, H.; Hou, X.; Zhang, H. Urban tree classification based on object-oriented approach and random forest algorithm using unmanned aerial vehicle (uav) multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yin, D.; Zhao, Z. Tree Species Classification Using UAV-Based RGB Images and Spectral Information on the Loess Plateau, China. Drones 2025, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immitzer, M.; Atzberger, C.; Koukal, T. Tree species classification with random forest using very high spatial resolution 8-band WorldView-2 satellite data. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 2661–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qin, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J. An improved DeepLabv3+ lightweight network for remote-sensing image semantic segmentation. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 2839–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Spectral features | Mean value of each band, Standard deviation, Brightness, Max. diff |

| Vegetation indices | Blue, Green, Red, EXG, NGBDI, NGRDI, RGRI, GLI |

| Geometric features | Area, Length/Width, Length, Width, Border length, Shape index, Density, Compactness, Asymmetry, Elliptic fit, Rectangular fit, Main direction |

| Positional features | X Center, X Max, X Min, Y Center, Y Max, Y Min, Z Center, Z Max, Z Min, Time, Time Max, Time Min, Distance to scene border |

| Textural features | GLCM Mean, GLCM Entropy, GLCM Homogeneity, GLCM Contrast, GLCM Dissimilarity, GLCM Correlation, GLDV Entropy, GLDV Mean, GLDV Contrast |

| Vegetation Indices | Calculation Formula |

|---|---|

| Blue | B/(R + G + B) |

| Green | G/(R + G + B) |

| Red | R/(R + G + B) |

| EXG | 2 × G − R − B |

| NGBDI | (G − B)/(G + B) |

| NGRDI | (G − R)/(G + R) |

| RGRI | R/G |

| GLI | (2 × G − R − B)/(2 × G + R + B) |

| Accuracy Verification | Masson Pine | Mixed Forest | Others | Camphor Tree | Coniferous Forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | 0.97 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| UA | 1 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| OA | 0.9855 | ||||

| Kappa | 0.9798 | ||||

| Original Model | MobileNetV2 | CBAM1 | CBAM2 | OA/% | Kappa/% | Model Parameters/M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | 92 | 88.78 | 27.30 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 88.73 | 84.31 | 5.81 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 90.73 | 87.01 | 5.90 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 94.91 | 92.89 | 5.91 |

| Semantic Segmentation Model | OA/% | Kappa/% | Model Parameters/M | PA/% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masson Pine | Mixed Forest | Others | Camphor Tree | Coniferous Forest | ||||

| PSPNet | 90.36 | 86.54 | 47.76 | 96.34 | 81.63 | 83.70 | 88.89 | 92.86 |

| DeepLabV3+ | 92.00 | 88.78 | 27.30 | 96.75 | 84.69 | 88.04 | 88.89 | 95.24 |

| U-Net | 92.91 | 90.12 | 31.04 | 95.12 | 93.88 | 89.13 | 88.89 | 92.86 |

| Improved DeepLabV3+ | 94.91 | 92.89 | 5.91 | 97.56 | 93.88 | 90.22 | 93.06 | 95.24 |

| Accuracy Verification | Masson Pine | Mixed Forest | Others | Camphor Tree | Coniferous Forest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.75 | 0.92 |

| UA | 0.98 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 0.79 |

| OA | 0.9418 | ||||

| Kappa | 0.8762 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Yin, J.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; You, H.; Han, X.; Zhou, G. Enhanced DeepLabV3+ with OBIA and Lightweight Attention for Accurate and Efficient Tree Species Classification in UAV Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 7501. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247501

Cheng X, Chen J, Li J, Yin J, Cheng Q, Chen Z, Li X, You H, Han X, Zhou G. Enhanced DeepLabV3+ with OBIA and Lightweight Attention for Accurate and Efficient Tree Species Classification in UAV Images. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7501. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247501

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Xue, Jianjun Chen, Junji Li, Jiayuan Yin, Qingmin Cheng, Zizhen Chen, Xinhong Li, Haotian You, Xiaowen Han, and Guoqing Zhou. 2025. "Enhanced DeepLabV3+ with OBIA and Lightweight Attention for Accurate and Efficient Tree Species Classification in UAV Images" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7501. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247501

APA StyleCheng, X., Chen, J., Li, J., Yin, J., Cheng, Q., Chen, Z., Li, X., You, H., Han, X., & Zhou, G. (2025). Enhanced DeepLabV3+ with OBIA and Lightweight Attention for Accurate and Efficient Tree Species Classification in UAV Images. Sensors, 25(24), 7501. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247501