Numerical Evaluation and Assessment of Key Two-Phase Flow Parameters Using Four-Sensor Probes in Bubbly Flow

Abstract

1. Introduction

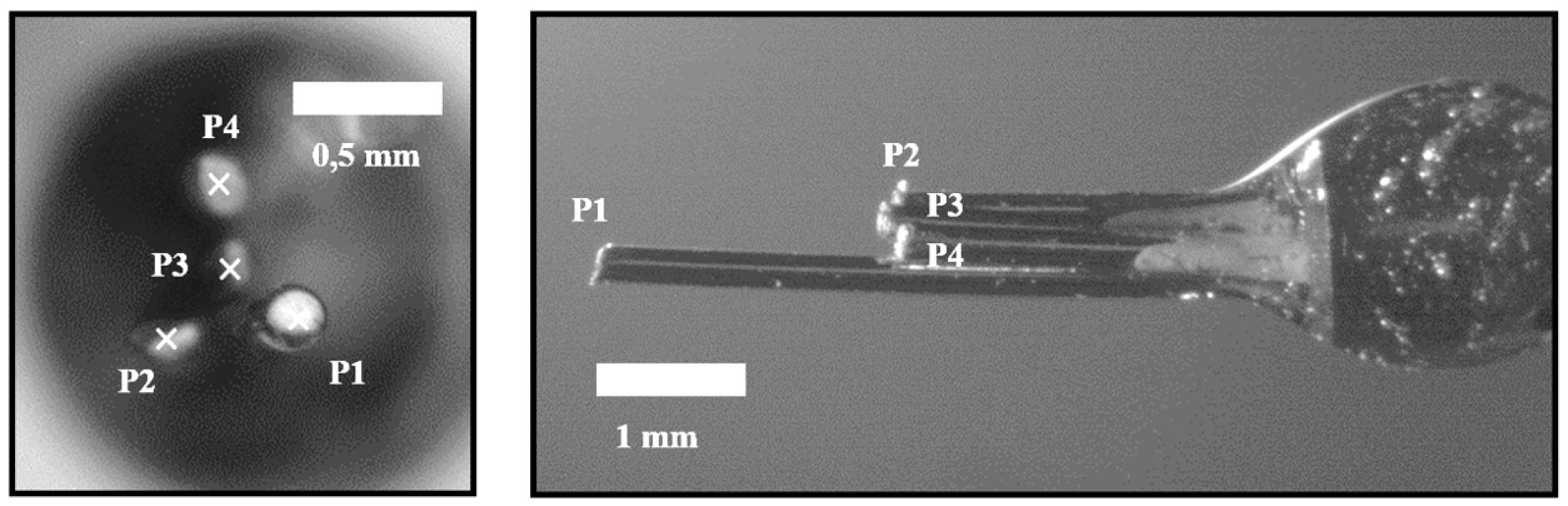

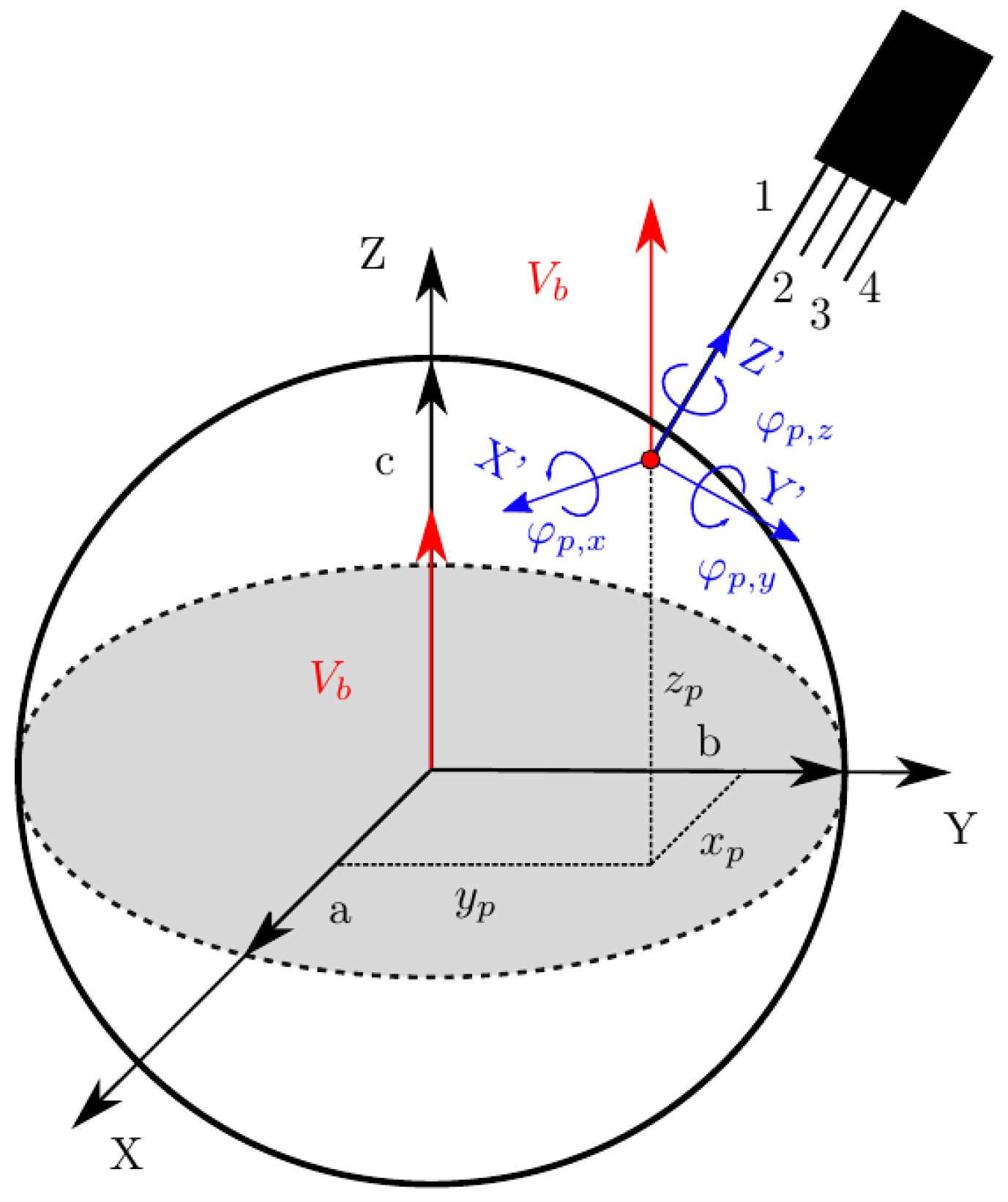

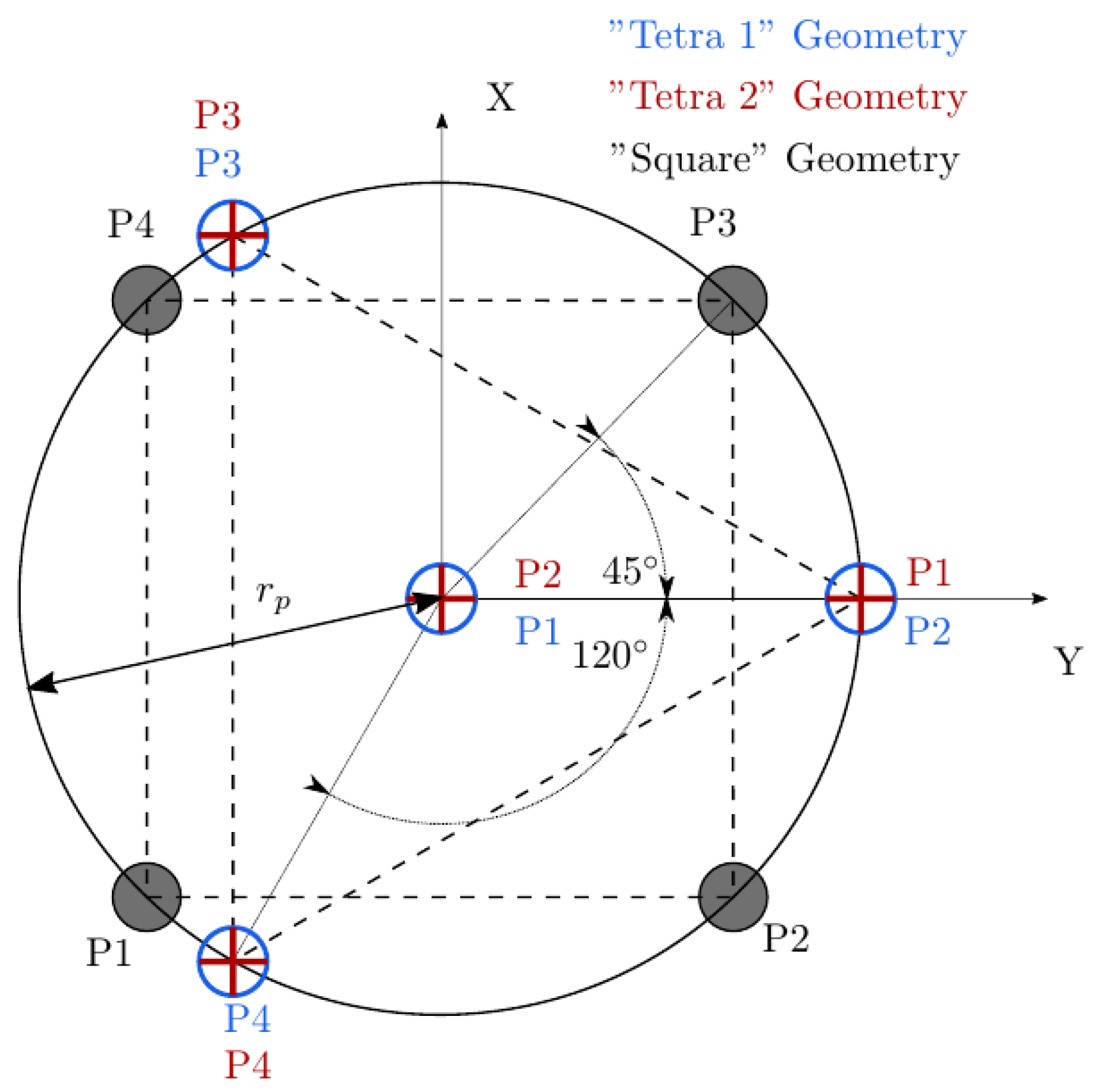

2. Four-Sensor Probes

- Front tip (1): [, ], with

- Rear tip (2): [, ], with and

- Rear tip (3): [, ], with and

- Rear tip (4): [, ], with and

2.1. Time-Averaged Local Parameters Measured with Needle Sensors

2.1.1. Local Time-Averaged Void Fraction

2.1.2. Local Time-Averaged Interfacial Area Concentration

2.1.3. Measurable Velocities by Means of a Four-Sensor Probe

2.1.4. Chord Length

3. Simulation Framework

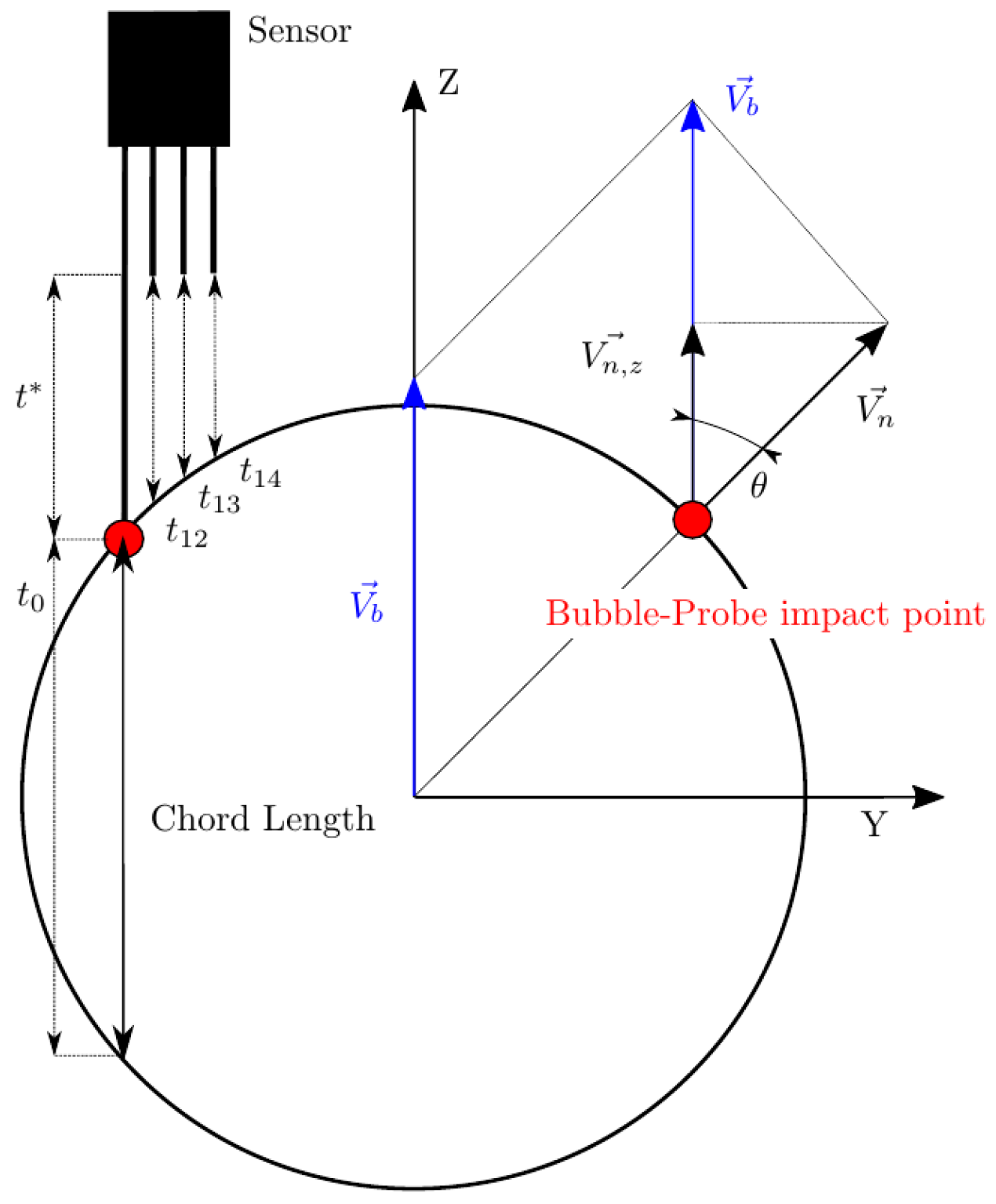

- To date, from the available methods to recover bubble velocity by using four-sensor probes (Equations (12) and (13)), we cannot account for the bubble centroid velocity, . Four-sensor probes are limited to two velocity modulus projections measurements, along the sensor probe axis, , or along the normal to surface direction, , and its components.

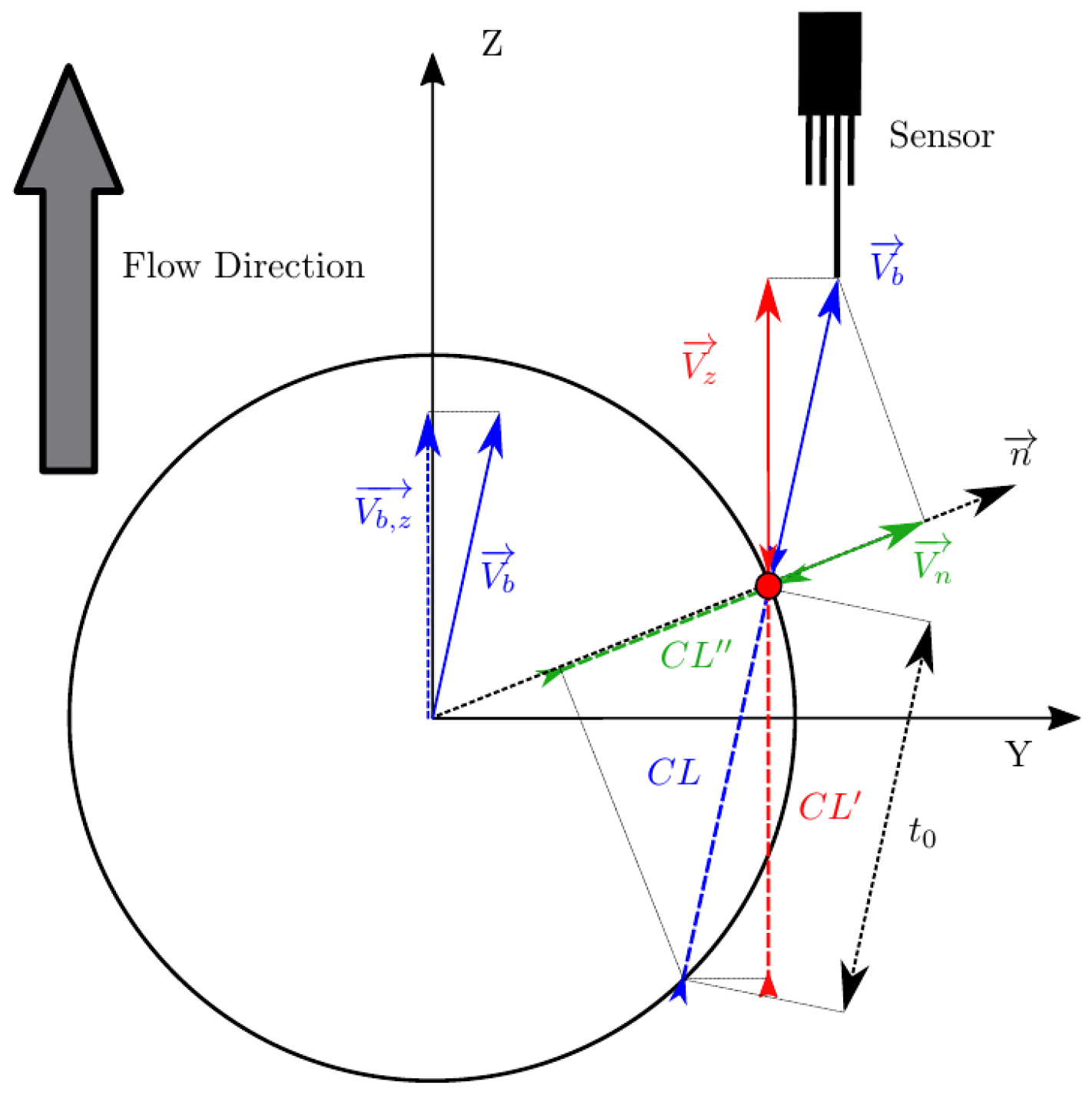

- As depicted in Figure 4, real or exact bubble chord length is measured in the bubble centroid velocity direction as . The sensor probe measurements are limited to and . In the ideal case, considering all measurement error sources to be negligible, we will always obtain .

- is the modulus of bubble centroid velocity, always defined as aligned in the Z-axis direction.

- and are, respectively, the axial and radial distances of the rear sensor tips with respect to the front sensor axis. We will relate these parameters to bubble equivalent diameter, D, defined as .

- represents the rotation angle vector in the probe coordinate system. and determine the arbitrary orientation of the probe sensor, while allows an arbitrary rotation of the rear sensors around the front sensor axis.

- and define the position of the front sensor tip in the XY plane.

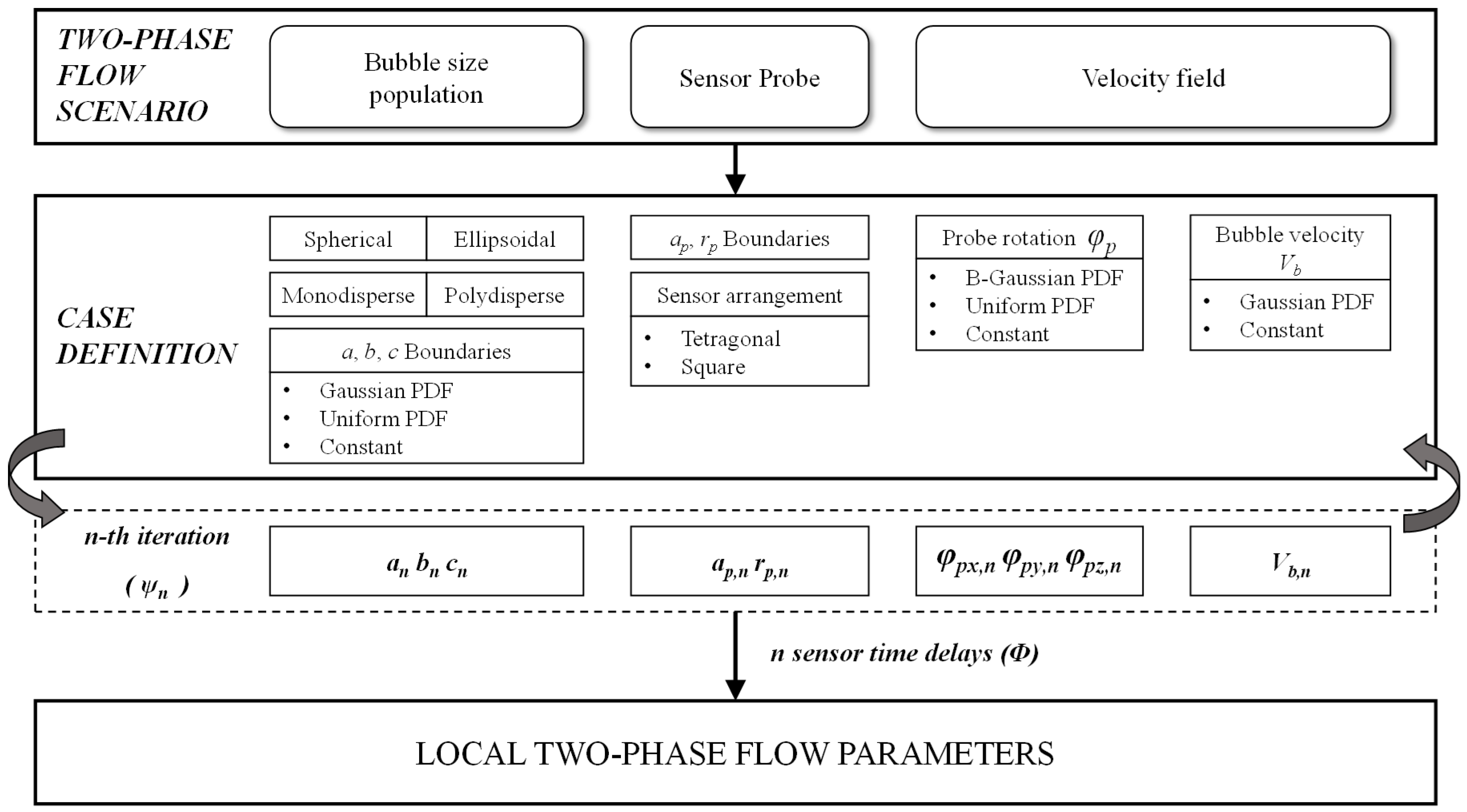

Algorithm and Monte Carlo Simulation

- Sensor alignment is initialized coincident to the Z-axis and with the front sensor tip located at the XYZ origin. Each k-th () rear sensor tip’s initial position () is referenced to the front sensor tip and defined by and distances as in Table 1. The front sensor tip will be positioned at a surface point of the bubble, defined by , , and , thus representing the start time of a bubble–probe interaction. The location is directly obtained from Equation (14) and locations and are obtained from a uniform distribution with the respective limits , and must satisfy the condition

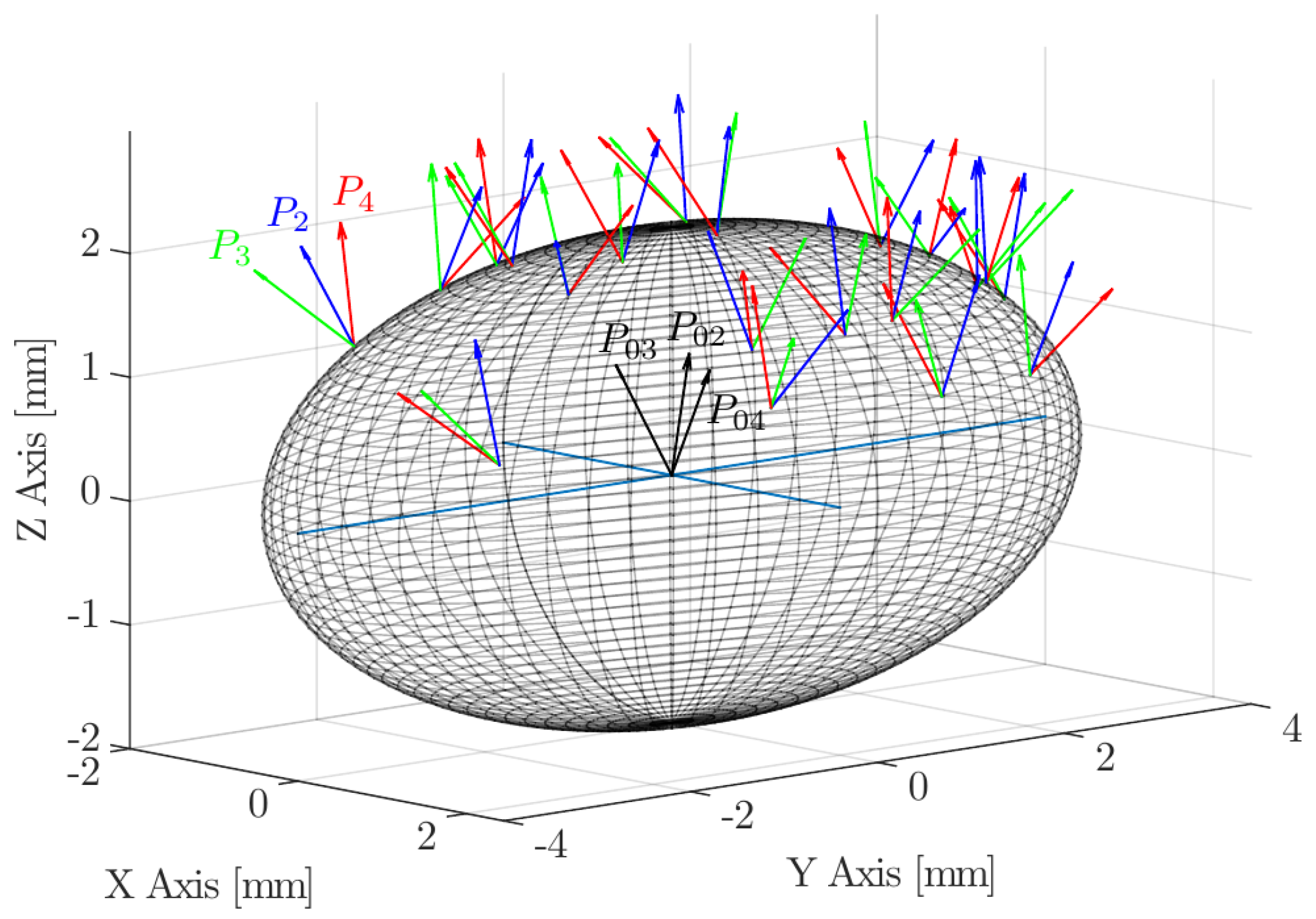

- Once inclination and rotation angles are defined, the final probe sensor k-th rear tip position, (), is obtained by means of a general homogeneous transformation matrix H:where the three rotation matrices are defined asand the translation matrix is defined asTherefore, the final rear sensor position will beNote that only the first three elements of account for its spatial location definition. Figure 9 illustrates this procedure to re-orient the probe sensor tips over an arbitrary ellipsoid surface based on and inputs, in this case for and 20 sample locations (iterations).

- Assuming a constant bubble velocity during the bubble–probe interaction, the sensor-tip trajectories are aligned with the Z-axis. If we define the point where the k-th tip contacts the bubble surface as , the four time delays in follow from:Recalling Equation (14), the contact times arewhere the ± sign corresponds to the two possible intersections of the tip trajectory with the ellipsoidal surface (entry and exit).

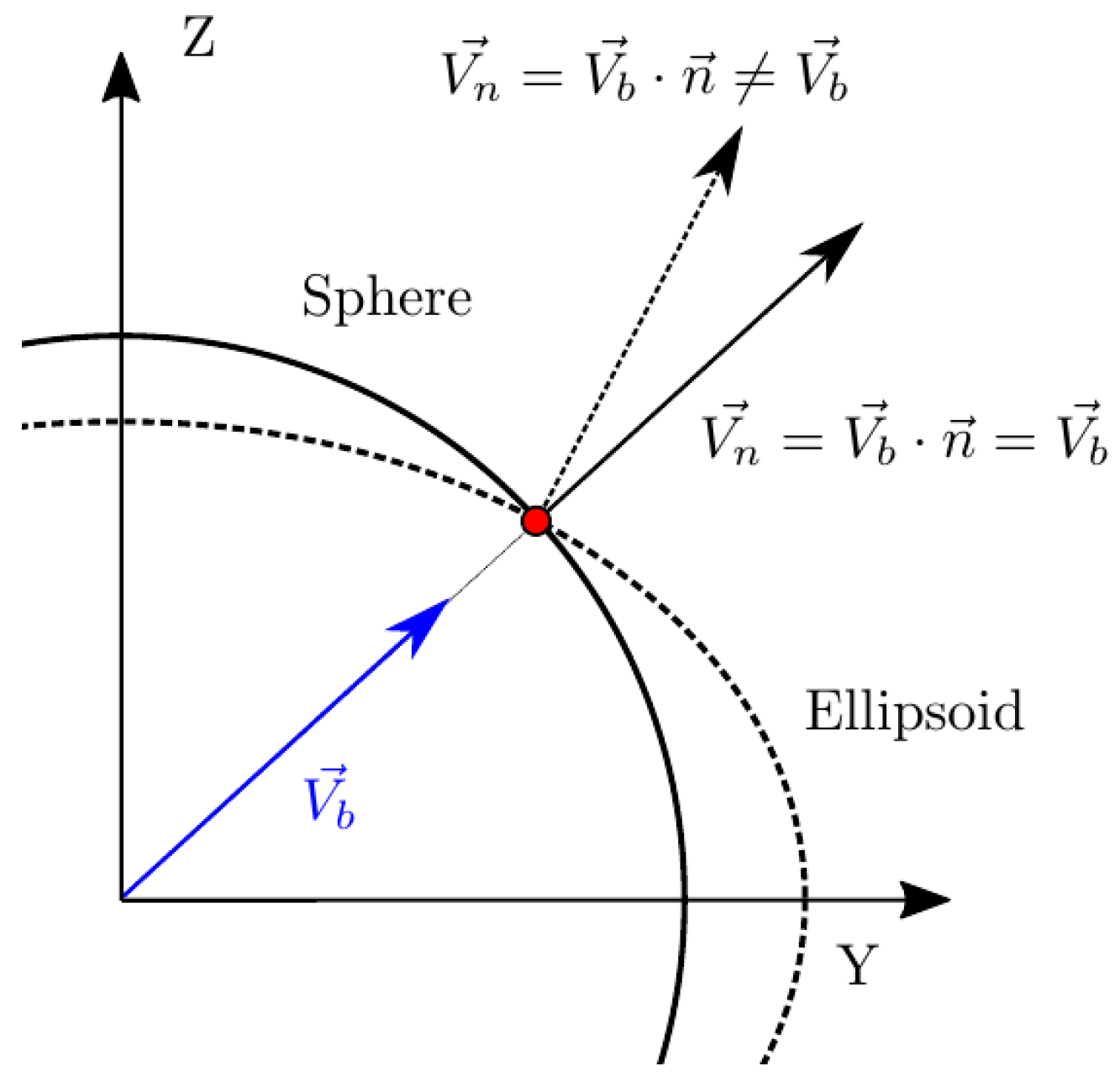

- We can consider spherical, ellipsoidal or mixed bubble geometries, thus considering a general bubble population. This could be very important for a proper sensitivity study of measurable local flow parameters: arbitrary bubble geometry definition permits us to achieve major variability in terms of bubble local curvature and chord length compared to the limited case of spherical bubble definition. It would serve to generalize obtained results, especially those measurements which are very sensitive to local curvature such as velocity, interfacial area, and chord length.

- Previous studies [6,13,14,16] were performed considering a spherical bubble geometry assumption. In this case, bubble–probe relative orientation is not important as long as all possible orientations can be achieved only by changing bubble velocity vector direction. However, if ellipsoidal bubble geometry definition is considered, bubble–probe orientation is very important to simulate more realistic and general scenarios. For example, the individual bubble–probe interaction depicted in Figure 11 can only be achieved by defining the probe location and orientation in a independent reference coordinate system.

- Considering bubble and probe coordinate systems separately provides several benefits. It permits us to define bubble geometry in a “frozen” XYZ bubble coordinate system where bubble velocity is always defined in the Z direction. It allows us to compute the individual bubble interfacial area by means of its volumetric definition (Equation (4)), since we are able to inscribe the bubble surface in a cylindrical volume always oriented in the actual bubble velocity direction, as depicted in Figure 10. It is important for setting up convergence criteria based in the interfacial area, as will be explained in Section 4.4.

- Bubble centroid velocity and interfacial velocity are defined as uncorrelated. Exact and measurable values for interfacial velocity at the bubble–probe contact point are obtained from the individual bubble shape, probe orientation, and bubble centroid velocity modulus. It allows us to perform the evaluation of measured bubble velocity and chord length without any previous assumptions and independently of local interfacial area measurement.

- Bubble surface is assumed to be non-deformable.

4. Available Two-Phase Flow Parameters from Four-Sensor Probes

4.1. Bubble Velocity from Simulations

- : as defined previously, it refers to bubble centroid velocity, defined in the bubble coordinate system and always in the Z direction.

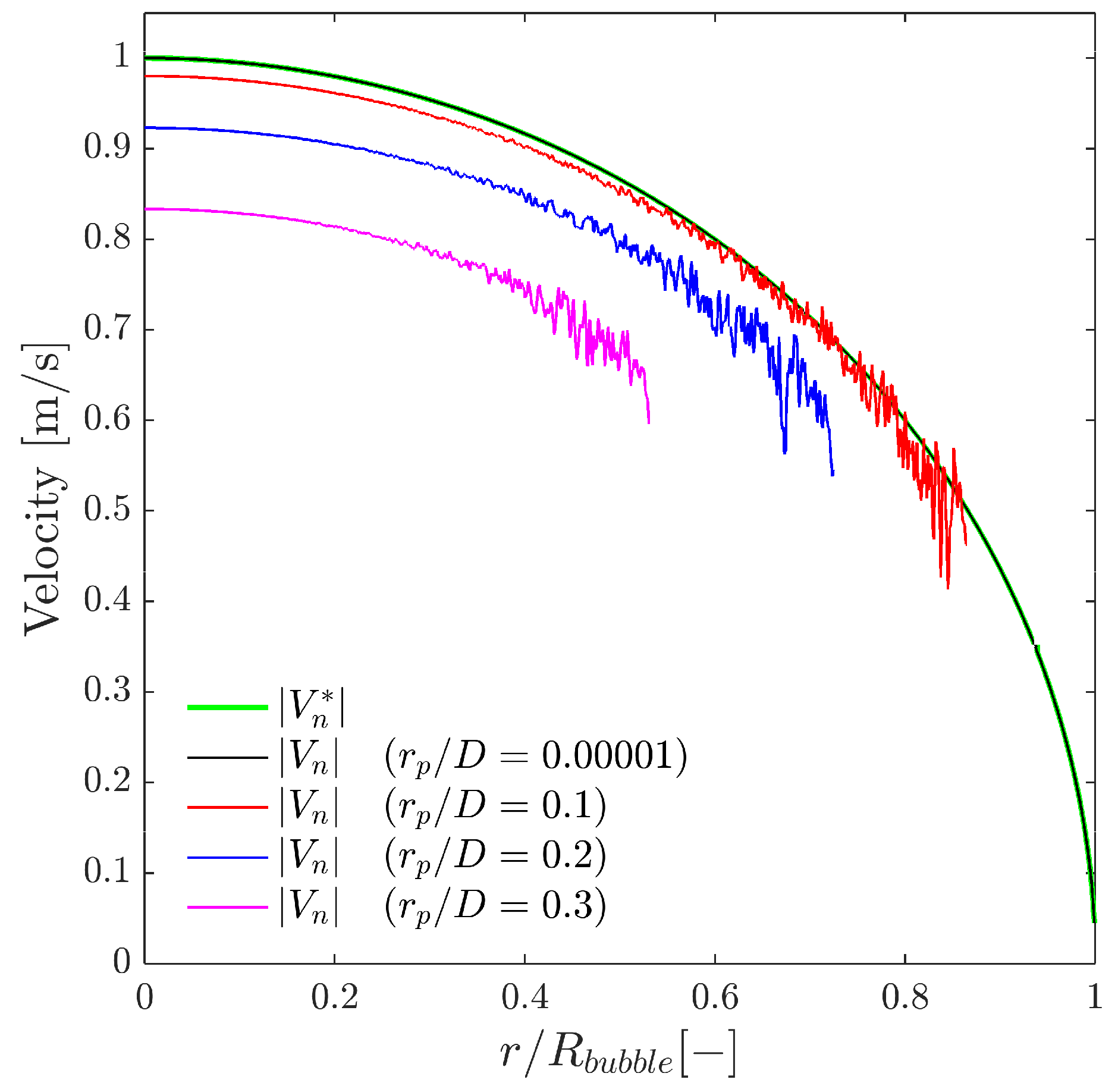

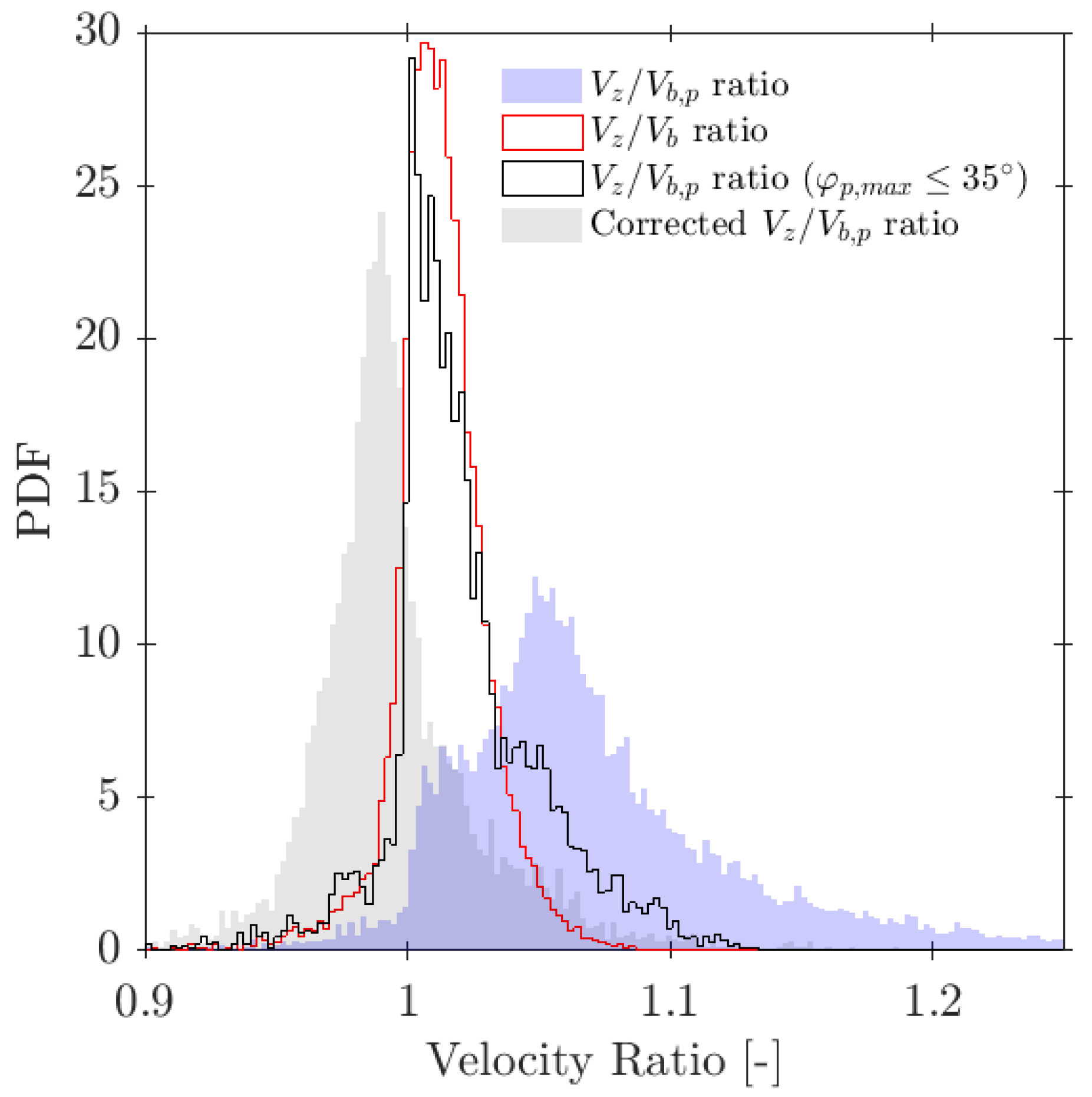

- : the bubble centroid velocity projection over the actual sensor probe axis. It is obtained by applying double homogeneous rotation over and a dot product over the Z-axis unitary vector ():The correct evaluation of from probe sensors is especially important in real measurements. Usually, in pipe flow measurements the sensor is aligned with pipe (flow) direction. In this situation, corresponds to local flux velocity to be integrated with local void fraction for gas flow-rate measurement and is therefore compared against the flow-meter reading [7,26,27,36,37]. In this sense, it is important to remark that depends on the bubble radial fluctuation, defined by . As illustrated in Figure 12, given a probability density function (PDF), the corresponding velocity PDF in the probe axis projection, velocity observed from the point of view of the virtual probe sensor, is underestimated as increases. Therefore, both velocities, and , should be evaluated separately because of their differing significance.

- : exact interfacial velocity obtained as the projection of over the normal to surface vector at the contact point. The normal to surface vector is obtained analytically from the surface equation and the bubble–sensor contact point individual locations.

- : bubble velocity measured by the sensor probe in its axis direction by means of , , , and , as in Equation (12). This velocity measurement should be comparable to and by some extent.

- : interfacial velocity measured according to Equation (13) by means of probe-obtained time delays and geometry. In contrast to , accounts for probe geometry, and therefore includes errors caused by local curvature. Ideally, will provide the same value as for narrow distances and if radial bubble velocity fluctuation is neglected.

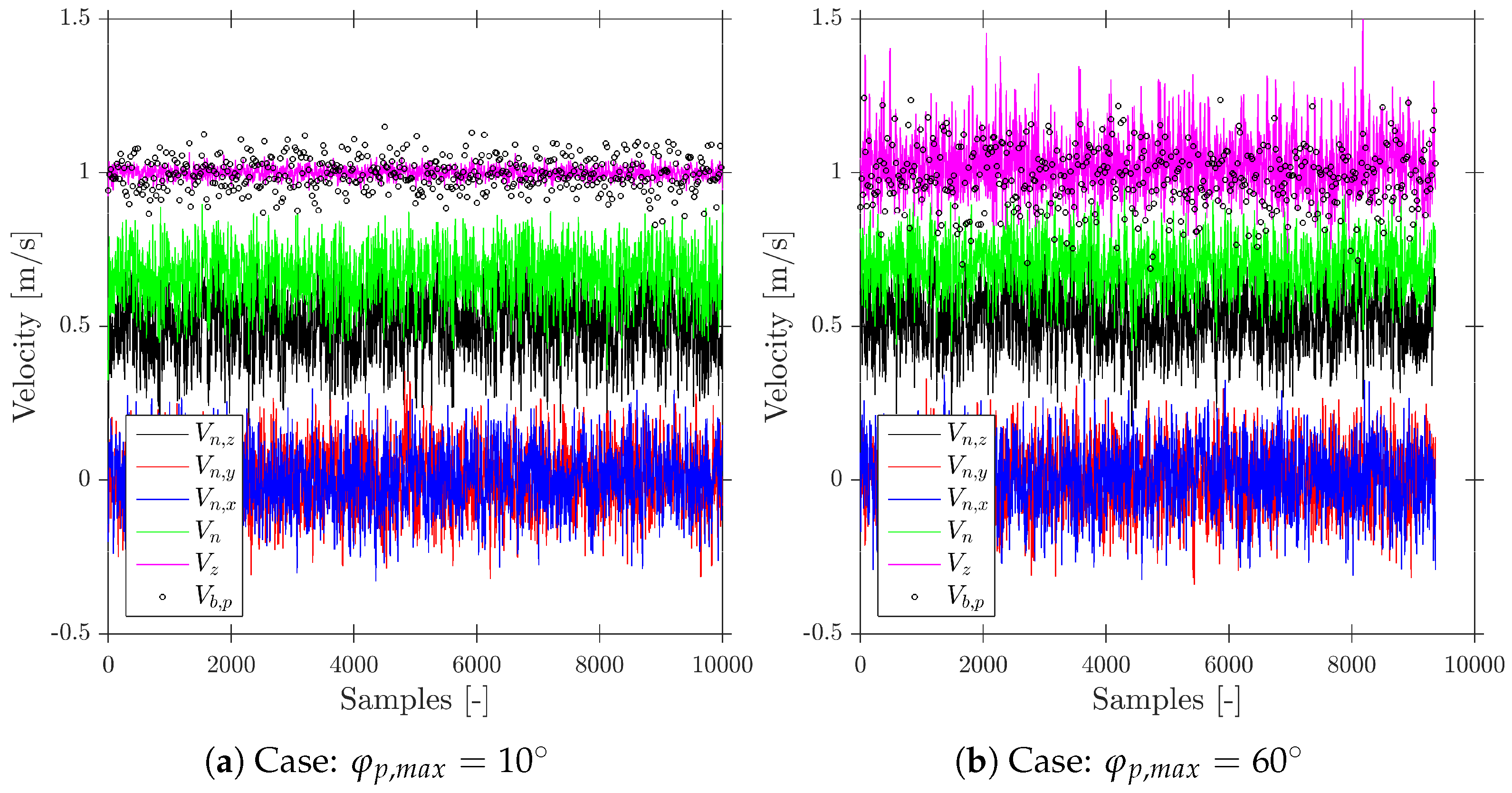

- Variability of bubble velocity is simulated by varying , obtained for each bubble–probe interaction from a Gaussian distribution with mean equal to one and standard deviation of 0.1.

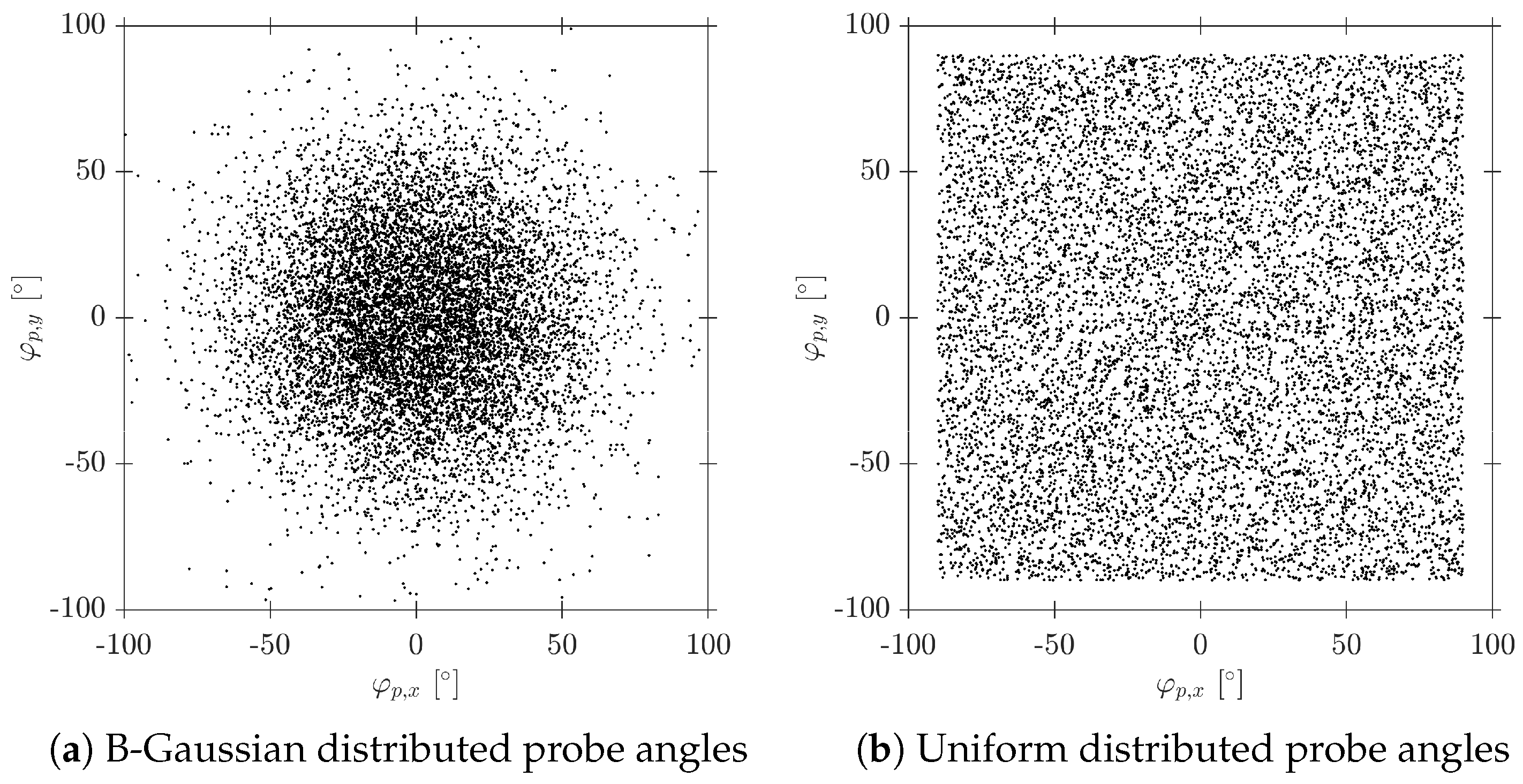

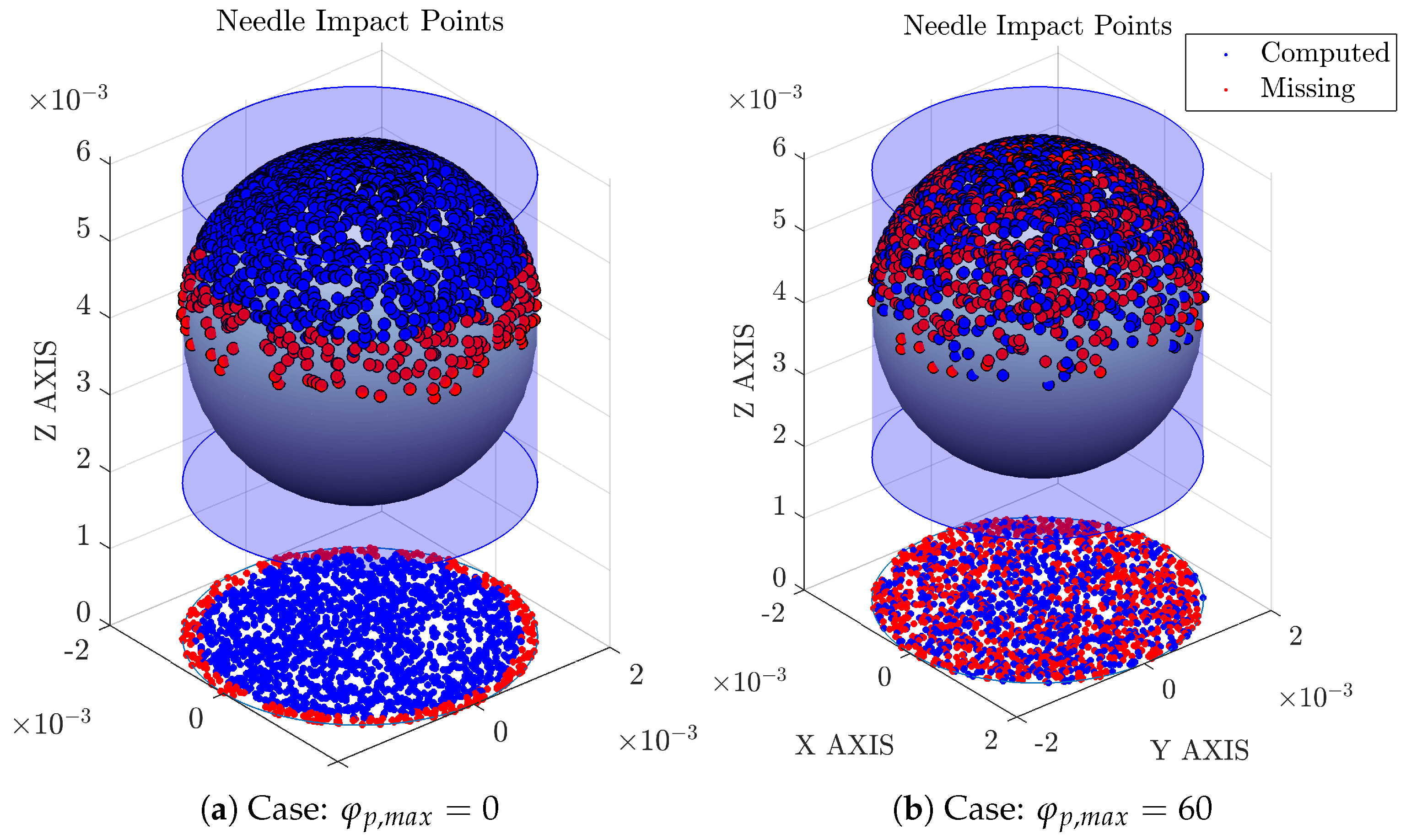

- Bubble radial velocity fluctuation is simulated by varying probe inclination angles, obtained from a Bivariant Gaussian distribution defined by for each interaction event.

- Considering a spherical bubble shape, the ratio is set again to 0.025 in order to minimize the influence of local curvature for measurements. The ratio is set arbitrarily to 0.1 and we have considered spherical geometry for bubbles for 10,000 bubble–probe interactions.

4.2. Chord Length from Simulations

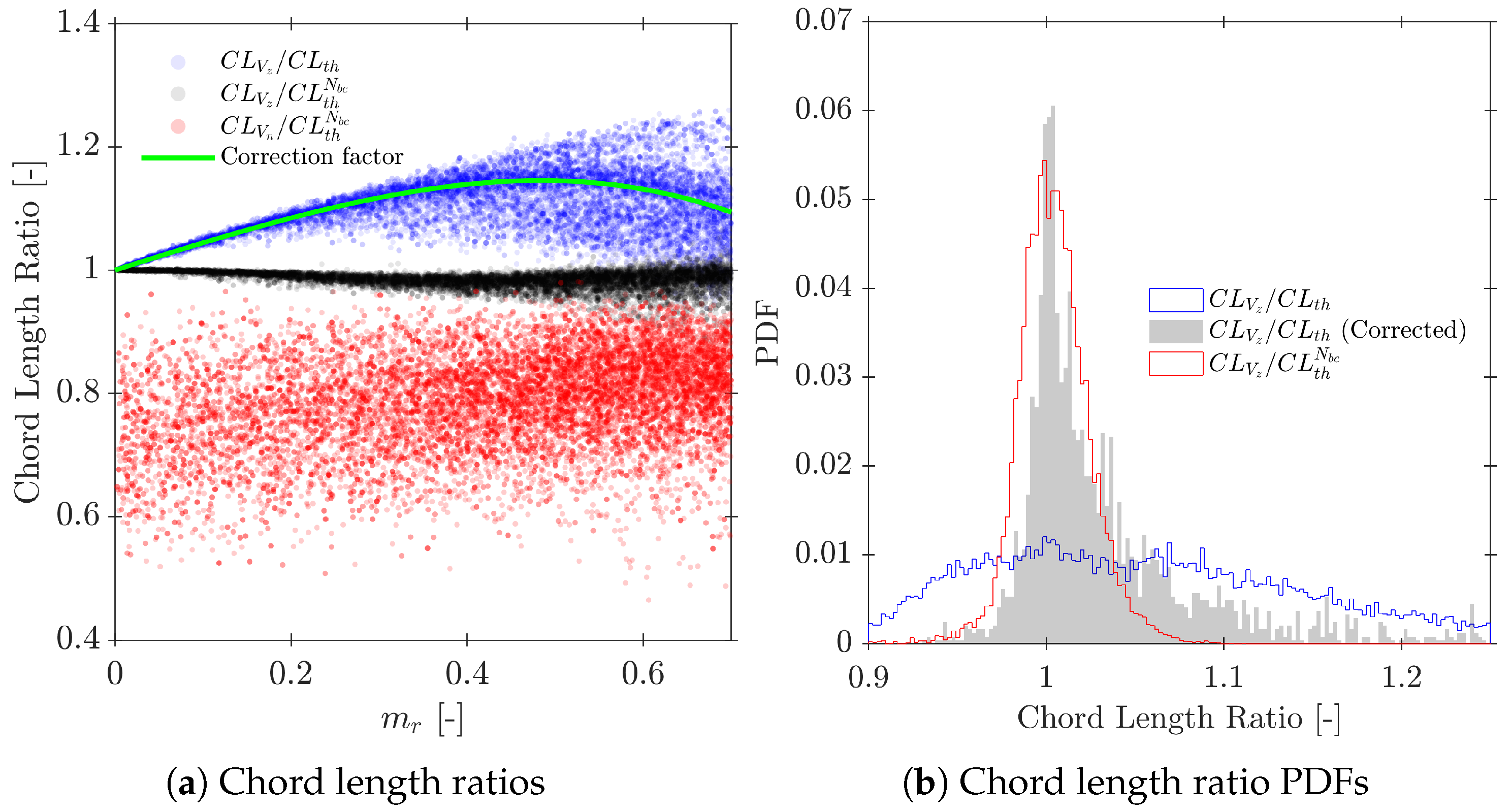

- : chord length measured by means of for each computed bubble.

- : chord length measured by means of for each computed bubble.

- : the ideal chord length, computed for all simulated bubbles () as the product of and the flight time of the front sensor tip inside the i-th bubble volume (). Unfortunately, cannot be obtained from real sensor probes. An exact value for is not available from probe measurements and cannot be computed for the whole bubble population, caused by unavoidable in real experiments.

- : as is the ideally measured chord length, but in this case, limited to the computed bubble population. In general, cause the missed chord lengths to correspond mostly to bubbles caught near its edge (smaller chord lengths).

4.3. Interfacial Area from Simulations

- : the present framework allows us to define a volume enclosing each bubble, which is necessary to obtain the volumetric interfacial area by means of Equation (4). It is computed as the averaged value of bubble area–volume ratios:where T is the time interval and volume V is defined as the cylinder enclosing the j-th bubble, as depicted in Figure 10. For spherical bubbles and a monodisperse bubble population, is a constant value because .

- : obtained by means of Equation (3), where the normal to surface vector is computed analytically given the bubble–probe impact point . In other words, it is the value for computed by means of . The represents the ideally measured time-averaged local interfacial area, as long as it considers all bubbles simulated:

- : interfacial area measured by the virtual sensor probe by means of as in Equation (9). Its computation requires the three time delays from rear sensors and probe geometry definition. Hence, it does not take into account missing bubbles, as information from the rear sensors is necessary. Therefore, considering only the computed bubbles, , and the front bubble interfaces:This is the equivalent measurement as if it was performed with a real sensor probe as long as it considers the deviations caused by local bubble curvature () and cannot account for missing bubbles’ interfacial area contribution.

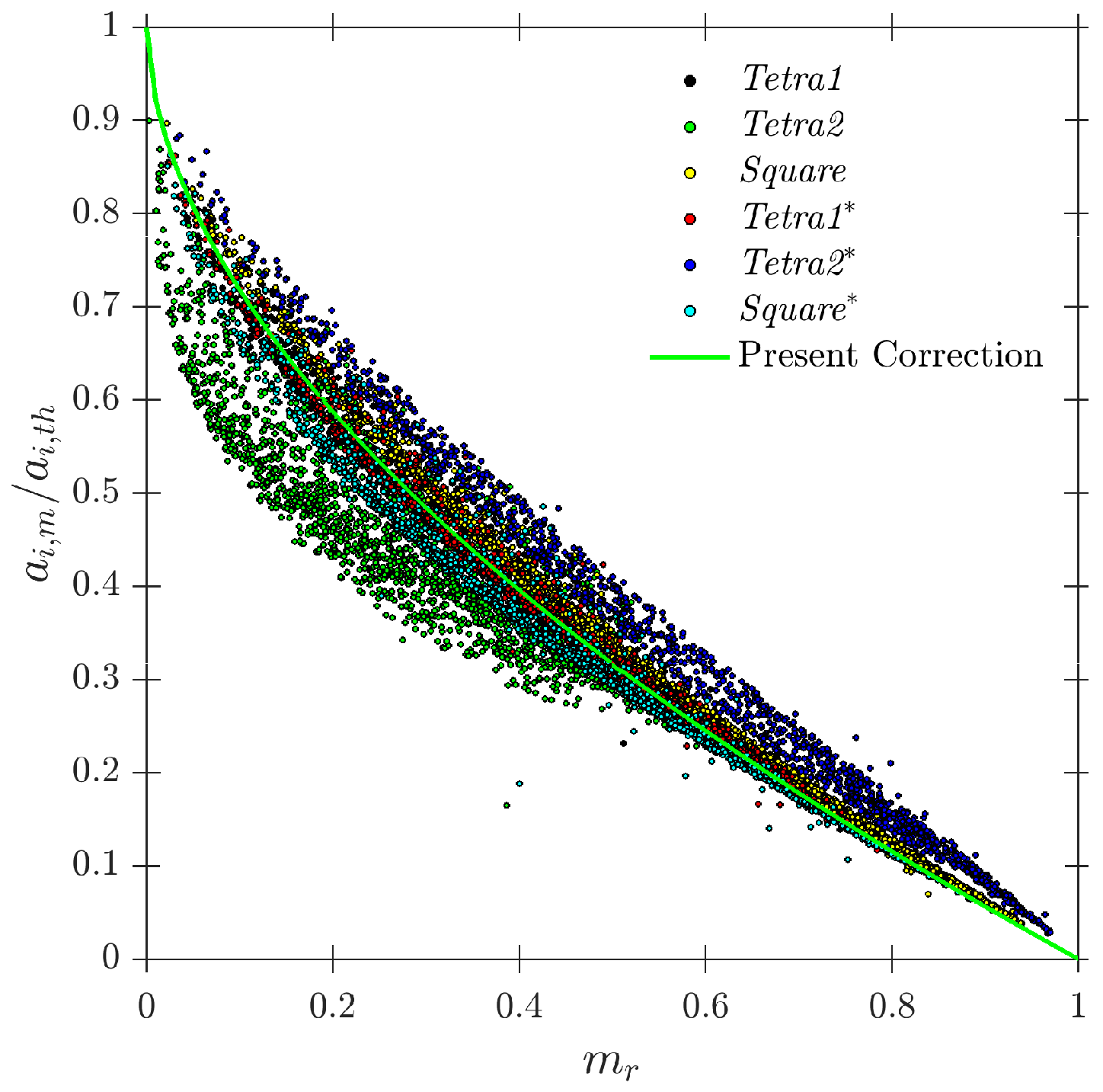

- : is the corrected value for , as long as it is obtained from , but only for computed bubbles:Hence, the value gives the time-averaged local interfacial area measured by an ideal sensor probe (negligible , and thus, negligible error caused by local curvature) but considering the fact that bubbles are missed because of sensor probe dimensions and radial bubble velocity fluctuations. Therefore, provides the exact local value for interfacial area as , but without considering the missing bubble contribution.

4.4. Convergence Criteria for Simulations

5. Simulation Definition and Review of Previous Works

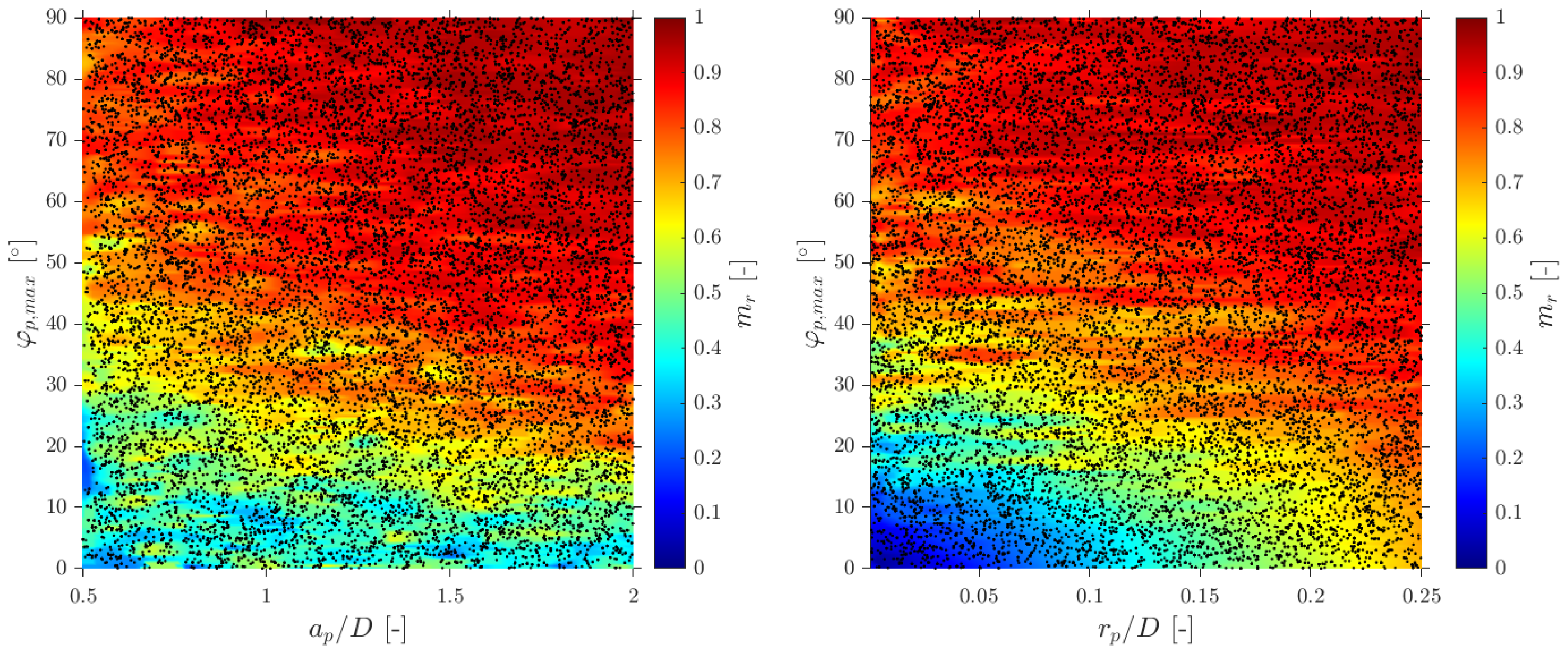

6. Evaluation of Probe Geometry Influence

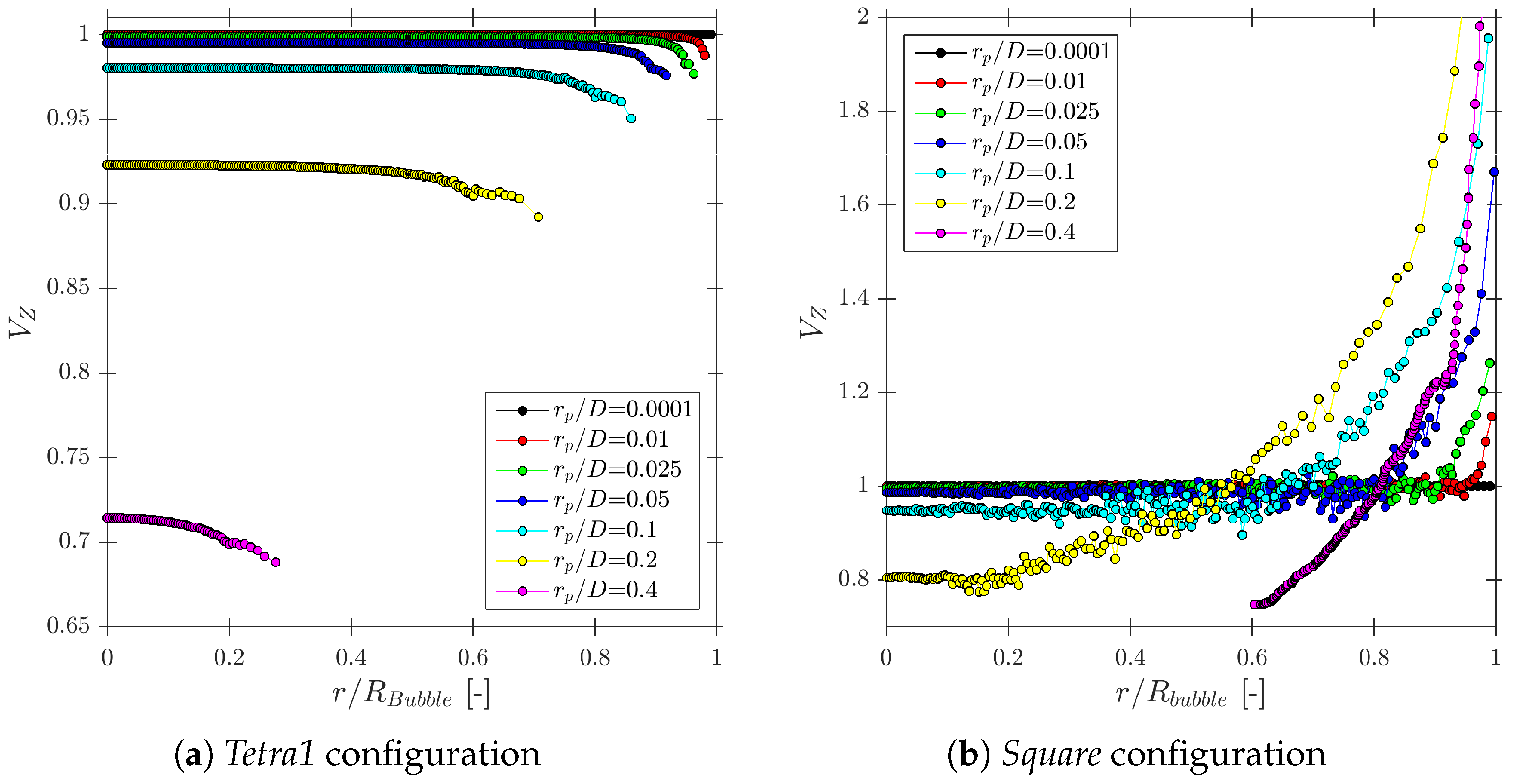

6.1. Velocity Measurements

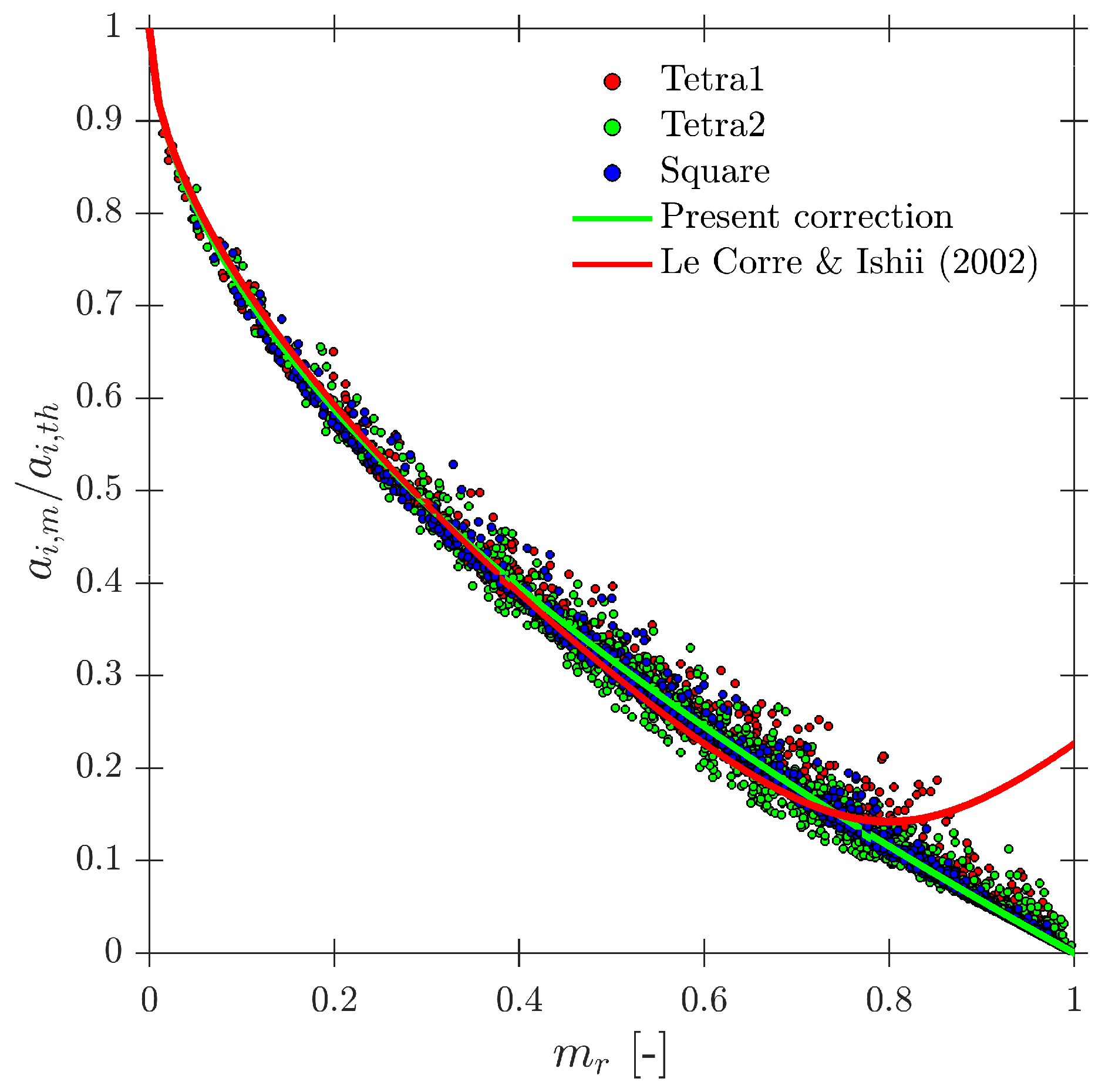

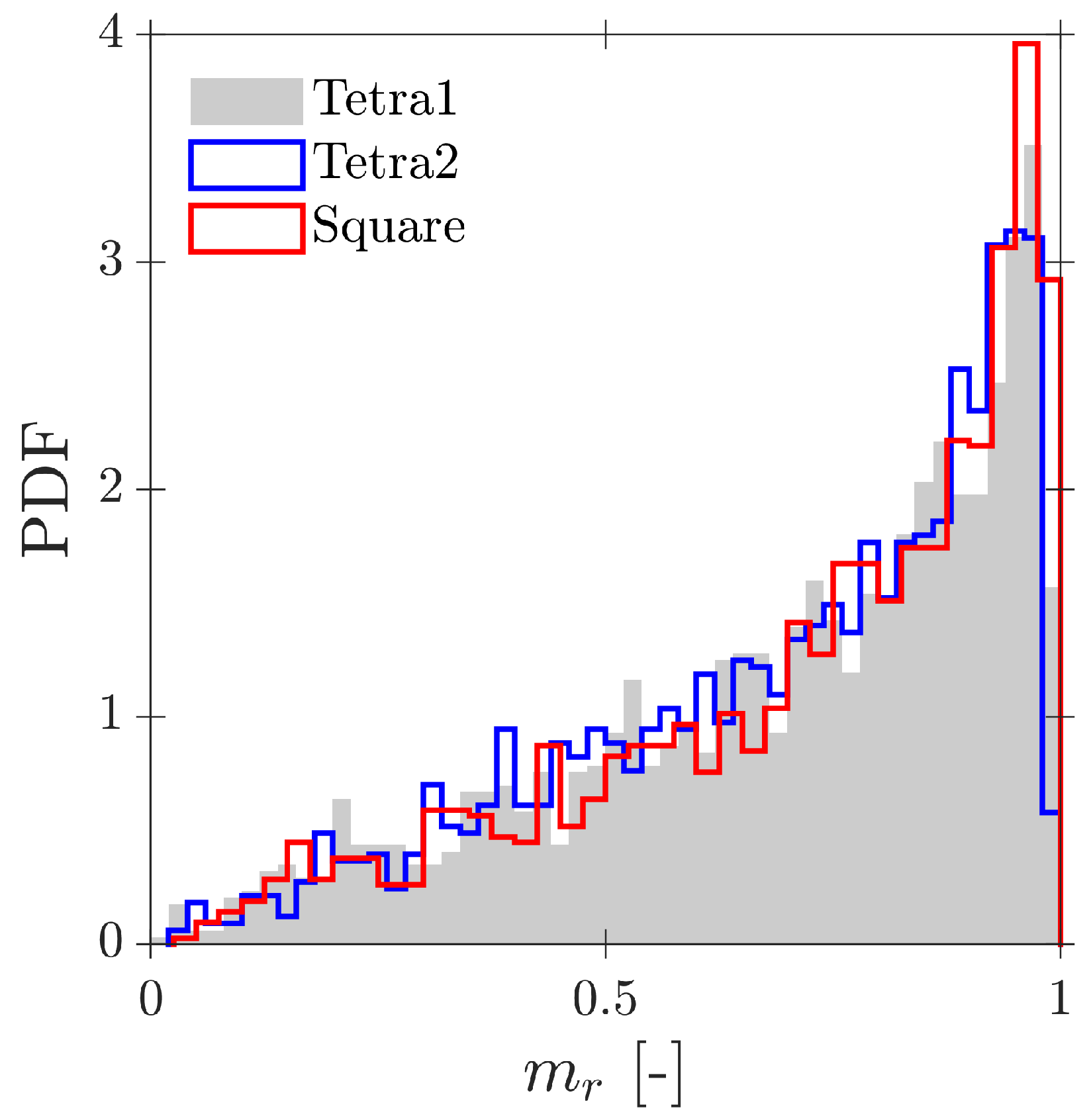

6.2. Interfacial Area Measurements

6.3. Chord Length Measurements

7. General Bubbly Flow Evaluation

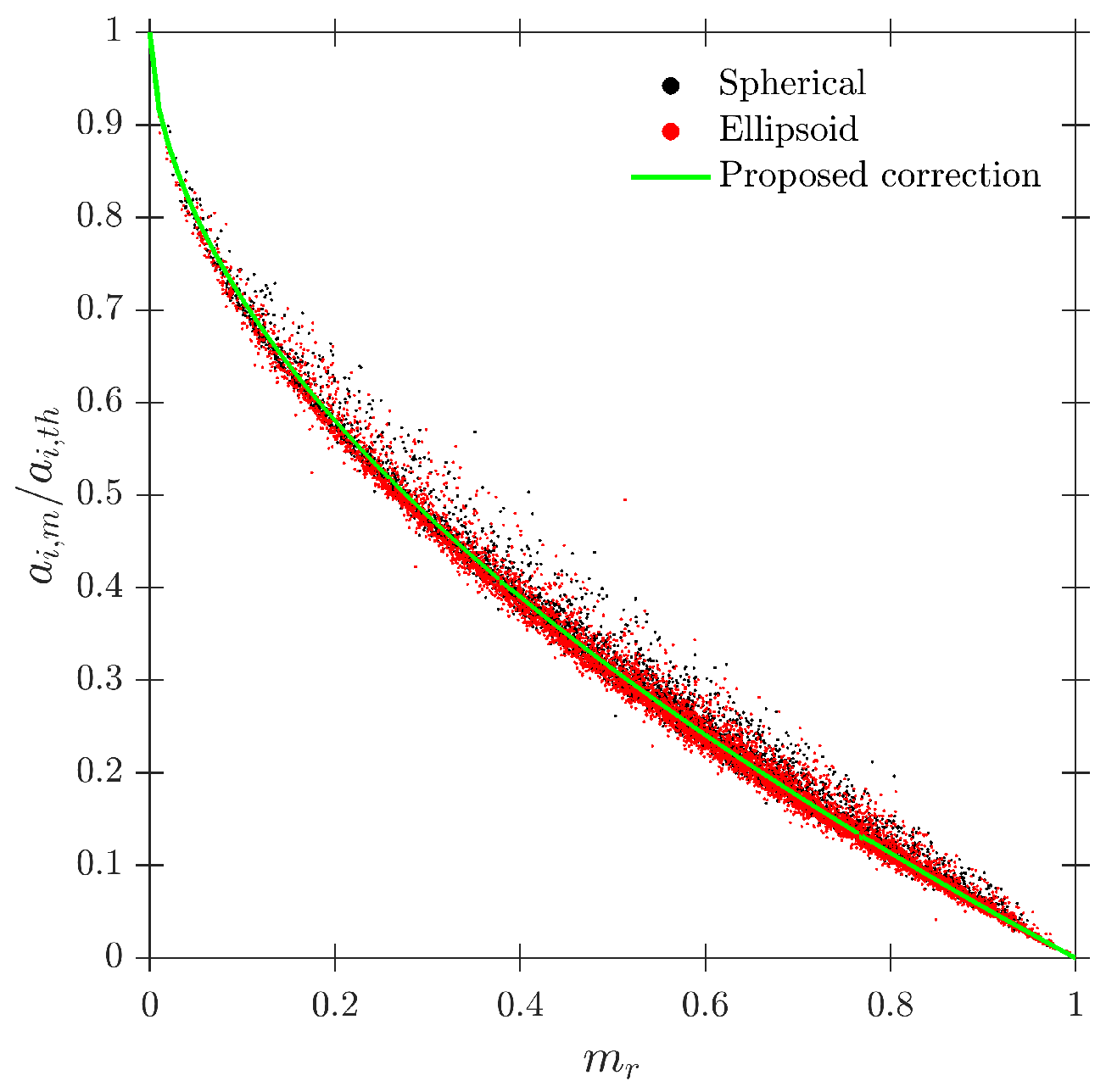

7.1. Effect of Bubble Geometry (Spherical/Ellipsoidal) and Interfacial Area Measurements

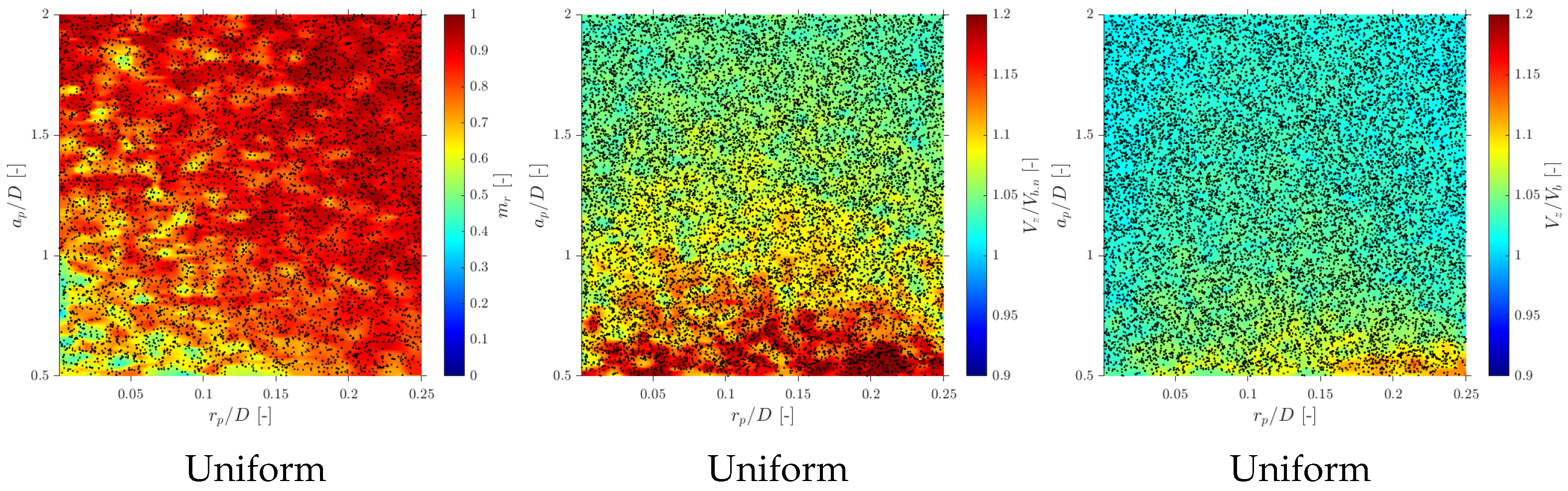

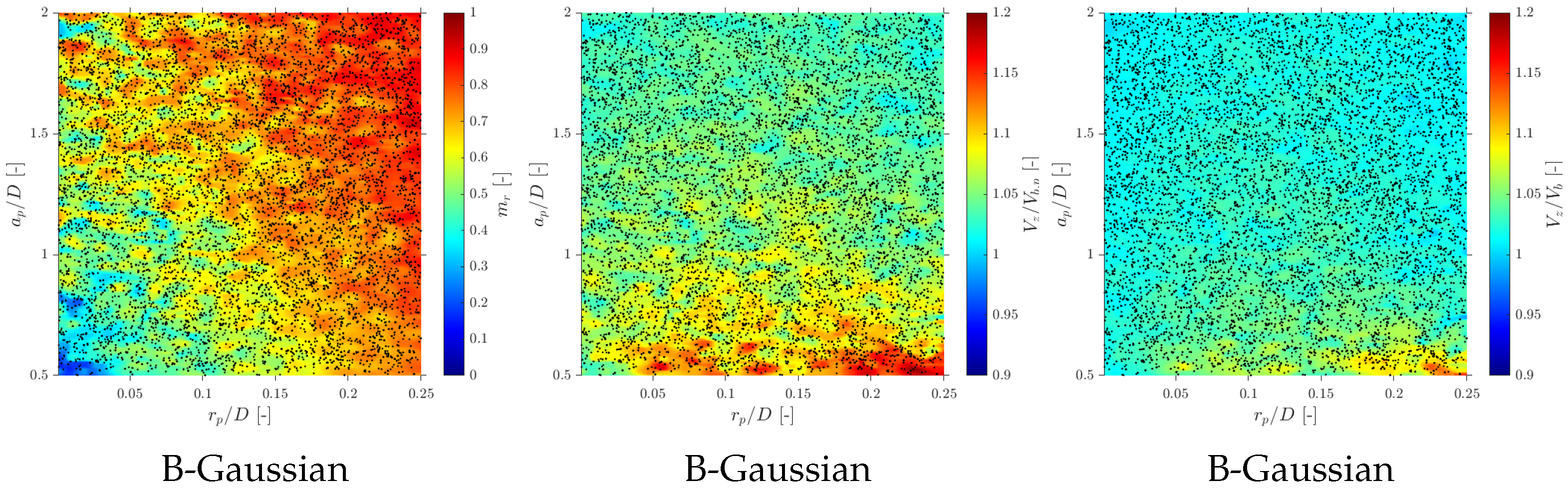

7.2. Effect of Bubble–Probe Angle Definitory PDF

- Increase in and major sensitivity to ratio.

- Higher variability and errors in and ratio estimation and, by extension, in ratio estimation.

7.3. Bubble Velocity Measurements

7.4. Chord Length Measurements

8. Conclusions

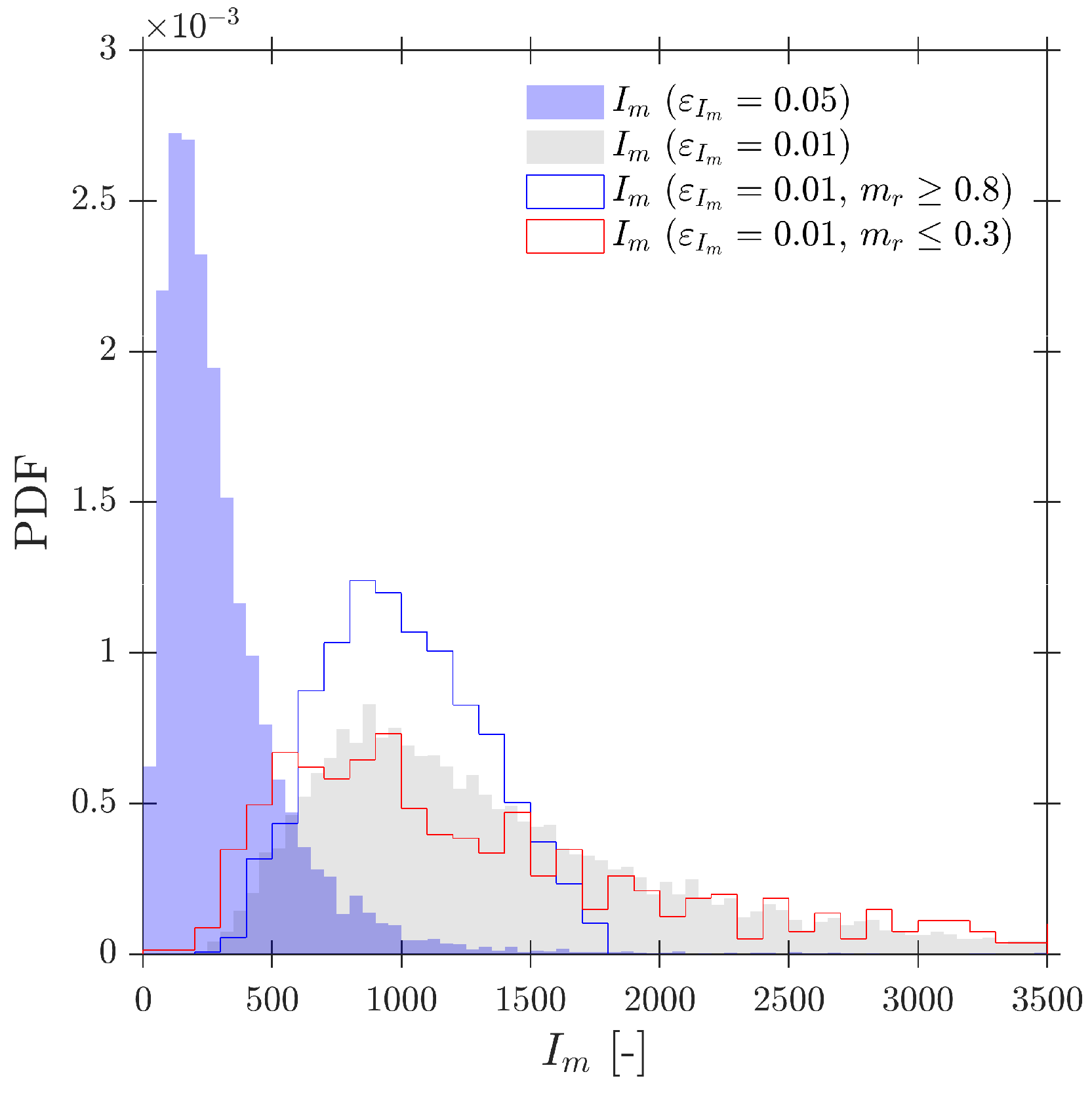

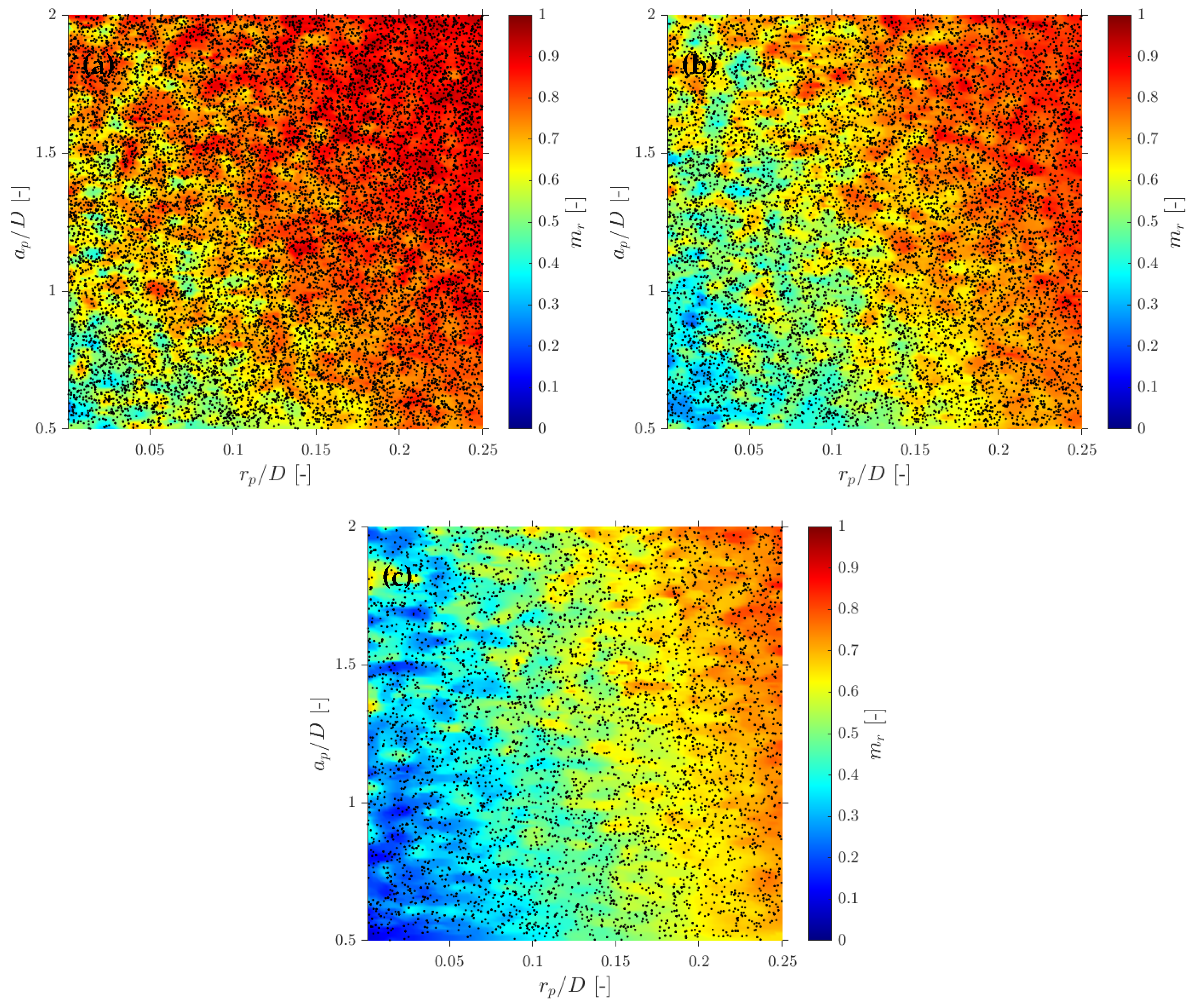

- Interfacial area concentration. The simulations confirm that a correction for the interfacial area concentration is required whenever the missing ratio is positive, in agreement with previous works. Here, this correction is shown to remain applicable without assuming spherical bubbles and when a full distribution of radial bubble velocities is considered. Using a volumetric definition of interfacial area ensures convergence in polydisperse conditions and provides a practical criterion for the minimum number of detected interfaces in experiments. An alternative correction expressed solely in terms of is proposed, extending the applicability up to . Within the recommended geometry range the corrected interfacial area remains quantitatively reliable, with typical errors below 10%; for a larger probe radius (e.g., ) the underestimation of can easily exceed 20– due to the increase in .

- Probe geometry. The results show that both the spacing-to-diameter ratio and the dimensionless probe radius control the measurement bias. While has been widely studied in the literature, the present sensitivity maps highlight the importance of in setting the missing ratio and curvature effects. Combining all metrics, probe geometries in the range and (Equation (38)) are recommended as a robust compromise between spatial resolution and accuracy for all local quantities considered. Outside this window, either very small spacing () or very large spacing (), as well as a large probe radius (), lead to strong increases in and to systematic biases in velocity, interfacial area and chord length estimates that readily exceed 20–.

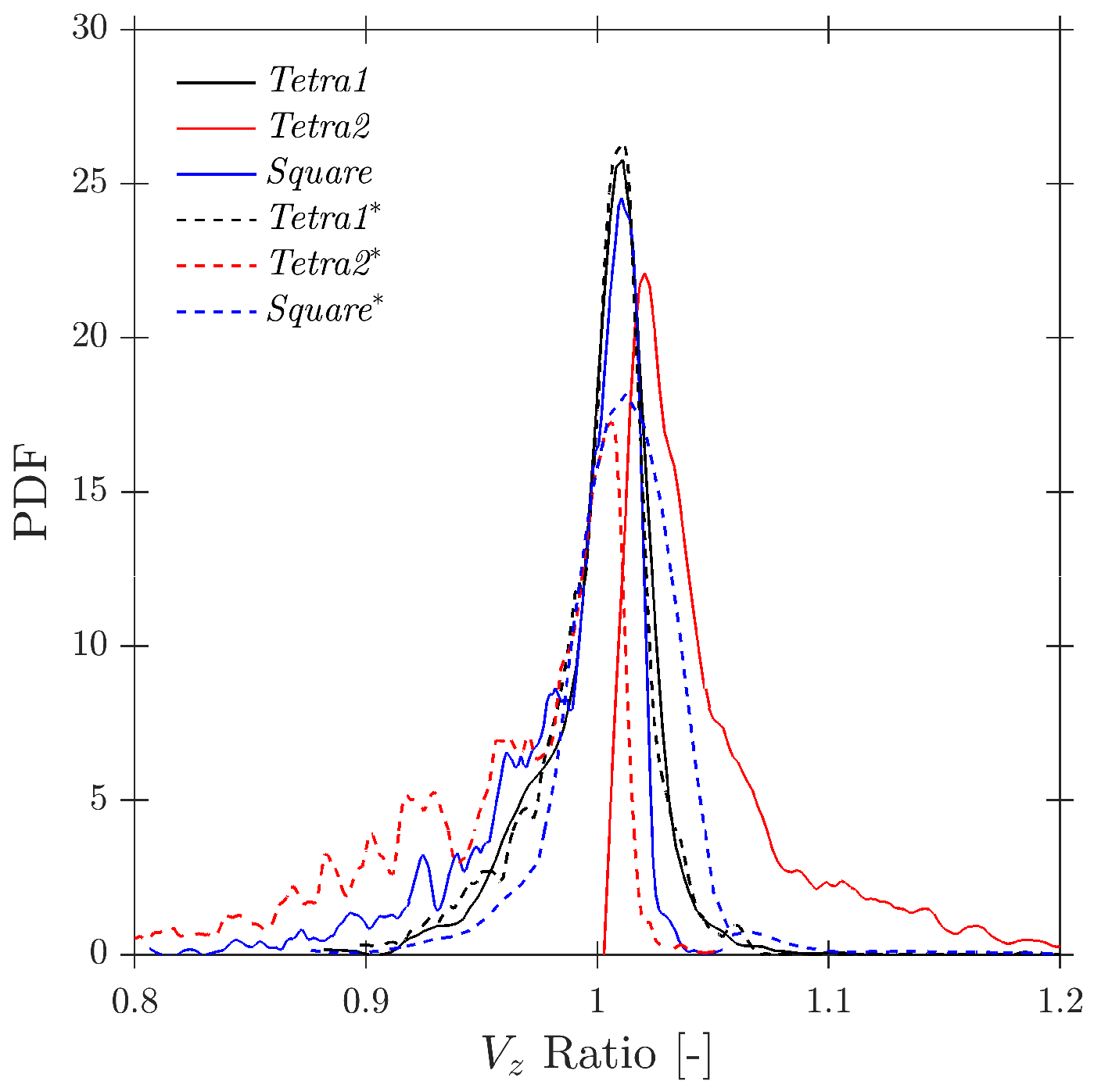

- Velocity measurements. The analysis clarifies the role of the different velocity definitions. The interfacial velocity (Equation (13)) is mainly suitable for interfacial-area estimation. In contrast, the axial velocity (Equation (12)) emerges as the most reliable estimator of both the bubble centroid velocity and its projection along the probe axis . Within the recommended geometric range and for moderate incidence angles (e.g., ), relative errors in and remain typically within . When the spread of incidence angles is increased (e.g., ), the velocity error can grow beyond even for favourable geometries, reflecting the kinematic limitations of four-sensor probes in highly oblique bubbly flows. A compact correction factor is proposed to recover the flux velocity from under a wide range of bubbly flow conditions.

- Chord length measurements. The appropriate velocity for chord length estimation is again , leading to . For the subset of computed bubbles, provides accurate chord lengths, consistent with what can be obtained in real experiments. When a significant fraction of bubbles is missed, tends to overestimate the population-average chord length, as short chords near the bubble edge are under-sampled. A correction factor (Equation (40)) is introduced to account for this effect using only the missing ratio. Within the recommended geometry range and for , this correction recovers the chord length distribution of the full bubble population with a residual bias of only a few percent, whereas for larger the chord length statistics become increasingly unreliable.

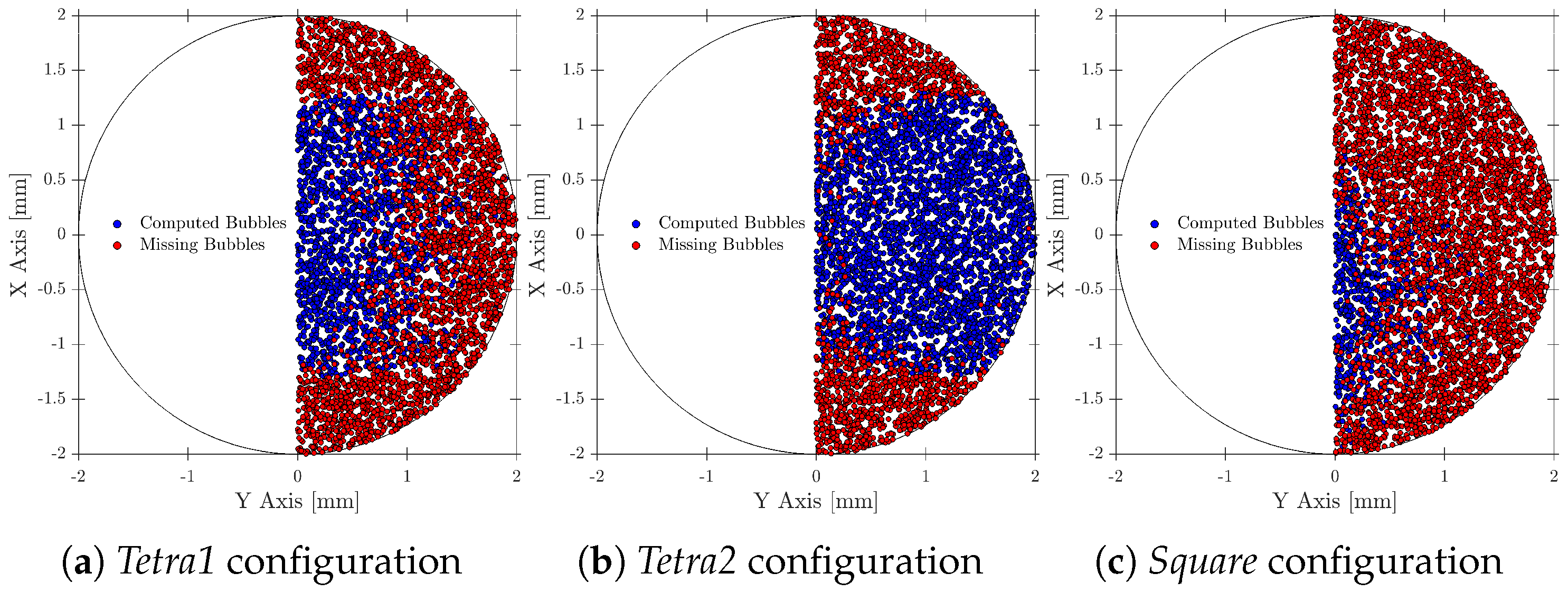

- Near-wall configurations. The probe arrangement with respect to the wall has a noticeable impact on the estimated local quantities. Configurations that place a rear tip too close to the wall increase the missing ratio and distort both velocity and chord length estimates. Among the tested layouts, the Tetra1 configuration is identified as the most suitable for near-wall measurements, as it mitigates these effects and yields more balanced sampling of bubble impacts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Time/phase descriptors | |

| T | Total measurement time interval (s). |

| Total gas residence time within T (s). | |

| Local time-averaged void fraction (-). | |

| , | Start/end detection times at the front tip (sensor 1) (s). |

| Front-tip flight (residence) time inside a bubble, (s). | |

| Front-tip flight time for the i-th bubble (s). | |

| Time delays between front tip and rear tips 2–4 (s). | |

| Vector of measurable delays, . | |

| Velocities | |

| Bubble centroid velocity and magnitude (m s−1). | |

| Axial (probe-axis) velocity estimate from time delays (m s−1). | |

| Interfacial (transport) velocity from four-sensor probe (s−1). | |

| Exact interfacial velocity using surface normal (numerical reference) (m s−1). | |

| , | Local unit normal and angle with transport direction at the j-th contact point (°). |

| Chord length (CL) | |

| Exact chord length in the centroid direction, (m). | |

| Chord length from axial estimate, (m). | |

| Chord length from interfacial estimate, (m). | |

| Ideal chord length for all simulated bubbles, (m). | |

| Ideal chord length restricted to computed bubbles () (m). | |

| Interfacial Area Concentration (IAC) | |

| Instantaneous global (volumetric) IAC (m−1). | |

| Local interfacial area concentration at point (m−1). | |

| Volumetric IAC from bubble-wise ratios (m−1). | |

| Ideal local IAC using (local-definition reference) (m−1). | |

| Measured local IAC from four-sensor probe using (computed bubbles only) (m−1). | |

| Curvature-corrected local IAC using (computed bubbles only) (m−1). | |

| Probe orientation / angular parameters | |

| Probe rotation-angle vector, (rad or °). | |

| , | Probe inclination angles (set the probe attacking direction) (rad or °). |

| Probe rotation about its own axis (rad or °). | |

| Maximum bubble attacking angle used to build the distribution of (rad or °). | |

| Counting / missing events | |

| Total number of simulated bubbles/events (-). | |

| Number of computed (detected) bubbles by the four-sensor probe (-). | |

| Missing bubble ratio, (-). | |

| Probe and geometry | |

| Semi-axes of an ellipsoidal bubble (m). | |

| D | Equivalent diameter, (m). |

| , | Axial and radial spacing between rear tips and the front tip (m). |

| Axial probe spacing normalized by the equivalent bubble diameter (–). | |

| Radial probe spacing normalized by the equivalent bubble diameter (–). | |

Appendix A. Theoretical Minimum Number of Sampled Bubbles for Accurate Measurements

Appendix B. Near-Wall Measurements

- We will consider an arbitrary bubble size generation (spherical/ellipsoidal bubbles). However, in order to limit the front sensor tip position between wall and a bubble radius () distance from the wall, a and b has are considered equal and constant for all generated bubbles. Thus, the only bubble size source of variability is included in c.

- We consider . These conditions ensure that the probe maintains its orientation for all bubble–probe interactions and avoid unrealistic effects such as a bubble moving throughout the wall. has been left intentionally as a source of variability as long as the lateral motion of the bubbles in the X-axis does not interfere with the wall.

- We have used the probe geometrical arrangement defined in Table 1 and three extra probe orientations redefined by means of a probe Z’-axis rotation in order to provide more information about the influence of probe–wall orientation.

References

- Kataoka, I.; Serizawa, A. Interfacial area concentration in bubbly flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1990, 120, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M.; Mishima, K. Two-fluid model and hydrodynamic constitutive relations. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1984, 82, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrau, E.; Poupot, C.; Cartellier, A. Single and double optical probes in air-water two-phase flows: Real time signal processing and sensor performance. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1999, 25, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejražka, J.; Večeř, M.; Orvalho, S.; Sechet, P.; Ruzicka, M.C.; Cartellier, A. Measurement accuracy of a mono-fiber optical probe in a bubbly flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2010, 36, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.; Revankar, S. Axial development of interfacial area and void concentration profiles measured by double-sensor probe method. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1995, 38, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Welter, K.; McCreary, D.; Reyes, J. Theoretical studies on the design criteria of double-sensor probe for the measurement of bubble velocity. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2001, 12, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibiki, T.; Ishii, M.; Xiao, Z. Axial interfacial area transport of vertical bubbly flows. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2001, 44, 1869–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ishii, M.; Wu, Q.; McCreary, D.; Beus, S. Interfacial structures of confined air–water two-phase bubbly flow. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2002, 26, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revankar, S.; Ishii, M. Theory and measurement of local interfacial area using a four sensor probe in two-phase flow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1993, 36, 2997–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Fu, X.; Wang, X.; Ishii, M. Development of the miniaturized four-sensor conductivity probe and the signal processing scheme. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2000, 43, 4101–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Saito, Y.; Mishima, K.; Nakamura, H. Methodological improvement of an intrusive four-sensor probe for the multi-dimensional two-phase flow measurement. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2005, 31, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, S.G.; Franc, F.A.; Rosa, E.S. Statistical method to calculate local interfacial variables in two-phase bubbly fows using intrusive crossing probes. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2000, 26, 1797–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ishii, M. Sensitivity study on double-sensor conductivity probe for the measurement of interfacial area concentration in bubbly flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1999, 25, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Corre, J.M.; Ishii, M. Numerical evaluation and correction method for multi-sensor probe measurement techniques in two-phase bubbly flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2002, 216, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, S.; Rensen, J.; Guet, S. Bubble aspect ratio and velocity measurement using a four-point fiber-optical probe. Exp. Fluids 2004, 36, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cobo, J.L.; Peña, J.; Chiva, S.; Mendez, S. Monte-Carlo calculation of the calibration factors for the interfacial area concentration and the velocity of the bubbles for double sensor conductivity probe. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2007, 237, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, M. Thermo-fluid dynamic theory of two-phase flow. NASA STI/Recon Tech. Rep. A 1975, 75, 29657. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka, I.; Ishii, M.; Serizawa, A. Local formulation and measurements of interfacial area concentration in two-phase flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1986, 12, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrós-Andreu, G.; Martínez-Cuenca, R.; Torró, S.; Chiva, S. Local parameters of air–water two-phase flow at a vertical T-junction. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 312, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartellier, A. Optical probes for local void fraction measurements: Characterization of performance. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1990, 61, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartellier, A.; Achard, J.L. Local phase detection probes in fluid/fluid two-phase flows. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1991, 62, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, C.; Goreaud, N.; Delhaye, J.M. The local volumetric interfacial area transport equation: Derivation and physical significance. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1999, 25, 1099–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, I. Local instant formulation of two-phase flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1986, 12, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhaye, J. Sur les surfaces volumiques locale et int{∖’e}grale en {∖’e}coulement diphasique. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1976, 282, 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Delhaye, J.M. Some issues related to the modeling of interfacial areas in gas–liquid flows, I. The conceptual issues. C. R. Acad. Sci. Ser. IIB Mech. 2001, 329, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibiki, T.; Hogsett, S.; Ishii, M. Local measurement of interfacial area, interfacial velocity and liquid turbulence in two-phase flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1998, 184, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Nakamura, H. Local interfacial velocity measurement method using a four-sensor probe. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 67, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Yan, C.; Sun, L.; Tong, P.; Liu, G. Comparison of local interfacial characteristics between vertical upward and downward two-phase flows using a four-sensor optical probe. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 77, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uga, T. Determination of bubble-size distribution in a BWR. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1972, 22, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Clark, N.N.; Karamavruc, A.I. General Method for the Transformation of Chord-Length Data to a Local Bubble-Size Distribution. AIChE J. 1996, 42, 2713–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Clark, N.N.; Karamavruç, A.I. Relationship between bubble size distributions and chord-length distribution in heterogeneously bubbling systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1998, 53, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.N.; Turton, R. Chord length distributions related to bubble size distributions in multiphase flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1988, 14, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Angeli, P.; Matar, O.K.; Lawrence, C.J.; Hewitt, G.F. Evaluation of drop size distribution from chord length measurements. AIChE J. 2006, 52, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.H.; Euh, D.J.; Yun, B.J.; Song, C.H. A new method of relating a chord length distribution to a bubble size distribution for vertical bubbly flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2015, 71, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá, E.J.; Harteveld, W.K.; Mudde, R.F.; den Akker, H.E.A. On the Accuracy of the Void Fraction Measurements Using Optical Probes in Bubbly Flows. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2005, 76, 035103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Schlegel, J.; Hibiki, T.; Ishii, M. Two-phase flow structure in large diameter pipes. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2012, 33, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doup, B.; Zhou, X.; Sun, X. Local gas and liquid parameter measurements in air–water two-phase flows. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2013, 263, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Mishima, K.; Nakamura, H. Error reduction, evaluation and correction for the intrusive optical four-sensor probe measurement in multi-dimensional two-phase flow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. Interfacial Area Measurement and Transport Modeling in Air–Water Two-Phase Flow. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Nuclear Engineering, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa, A.; Kataoka, I.; Michiyoshi, I. Turbulence structure of air-water bubbly flow—II. local properties. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1975, 2, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euh, D.; Yun, B.; Song, C.; Kwon, T.; Chung, M.; Lee, U. Development of the five-sensor conductivity probe method for the measurement of the interfacial area concentration. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 205, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkach-Navarro, S.; Lahey, R.T.; Drew, D.A.; Meyder, R. Interfacial Area Density, Mean Radius and Number Density-Measurements in Bubbly 2-Phase Flow. Nucl. Eng. Des. 1993, 142, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tip | X | Y | Z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0 | |||

| Tetra1 | P2 | |||

| P3 | ||||

| P1 | 0 | |||

| Tetra2 | P2 | |||

| P3 | ||||

| P1 | 0 | |||

| Square | P2 | |||

| P3 | 0 |

| Simulation | Cases (Iterations) | Bubble Population | /D [-] | /D [-] | Probe Geometry | , [°] | Velocity Vb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-Wide | () | S/M | [0, 0.45] | [0.1, 4] | T1,S | BG/[0, 90] | CNT |

| S-Geom | () | S/P | [0, 0.45] | [0.1, 4] | T1,T2,S | BG/[0, 90] | CNT |

| S-Main | () | S,E/M,P | [0, 0.25] | [0.5, 2] | T1,T2,S | BG,U/[0, 90] | G,CNT |

| S-Wall | () | S,E/M,P | [0, 0.25] | [0.5, 2] | T1,T2,S | BG/[0, 90] | G |

| Region | Geometry Range | Velocity Behaviour |

|---|---|---|

| A—Recommended | ; | best estimator of ; errors typically for moderate angles; Equation (39) applicable. |

| B—Large probe radius | (any ) | Strong curvature effects; under- or overestimated depending on impact position and probe arrangement. |

| C—Very small spacing | Systematic overestimation of (and ); more sensitive to radial velocity fluctuations. | |

| D—Very large spacing | Higher ; flux velocity becomes more sensitive to incidence-angle distribution. |

| Region | Geometry Range | Chord Length Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| A—Recommended | ; | for ; Equation (40) applicable. |

| B—Large probe radius | (any ) | Higher ; short chords near the bubble edge are missed; strong geometry-induced bias. |

| C—Very small spacing | Systematic overestimation of and thus of ; increased sensitivity to incidence angles. | |

| D—Very large spacing | Larger without gain in chord length resolution. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monrós-Andreu, G.; Peña-Monferrer, C.; Martínez-Cuenca, R.; Torró, S.; Chiva, S. Numerical Evaluation and Assessment of Key Two-Phase Flow Parameters Using Four-Sensor Probes in Bubbly Flow. Sensors 2025, 25, 7490. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247490

Monrós-Andreu G, Peña-Monferrer C, Martínez-Cuenca R, Torró S, Chiva S. Numerical Evaluation and Assessment of Key Two-Phase Flow Parameters Using Four-Sensor Probes in Bubbly Flow. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7490. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247490

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonrós-Andreu, Guillem, Carlos Peña-Monferrer, Raúl Martínez-Cuenca, Salvador Torró, and Sergio Chiva. 2025. "Numerical Evaluation and Assessment of Key Two-Phase Flow Parameters Using Four-Sensor Probes in Bubbly Flow" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7490. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247490

APA StyleMonrós-Andreu, G., Peña-Monferrer, C., Martínez-Cuenca, R., Torró, S., & Chiva, S. (2025). Numerical Evaluation and Assessment of Key Two-Phase Flow Parameters Using Four-Sensor Probes in Bubbly Flow. Sensors, 25(24), 7490. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247490