Graphene-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Metasurface for Mid-Infrared Four-Band Ultra-Narrow Absorbing Sensor

Highlights

- A graphene metamaterial is used to design a mid-infrared four-band ultra-narrowband absorption sensor, which is symmetrical in geometry and highly insensitive to incident light with different polarization directions.

- High absorption efficiency can be achieved at four specific resonance wavelengths, and the dynamic regulation of resonance wavelength and absorption efficiency can be achieved by adjusting the grid voltage or through chemical doping.

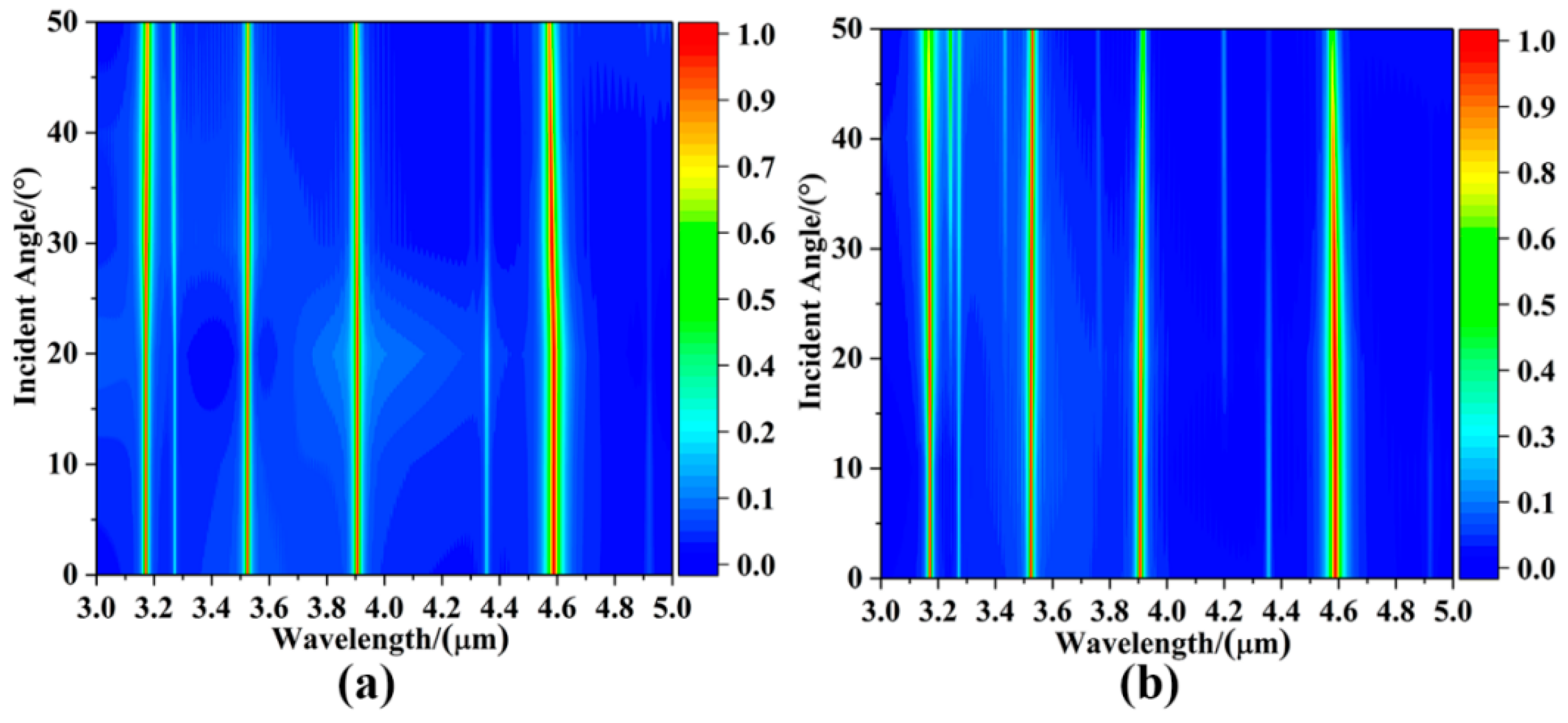

- It can maintain stable absorption characteristics in a large range of incidence angles from 0 to 50° and has good angular stability.

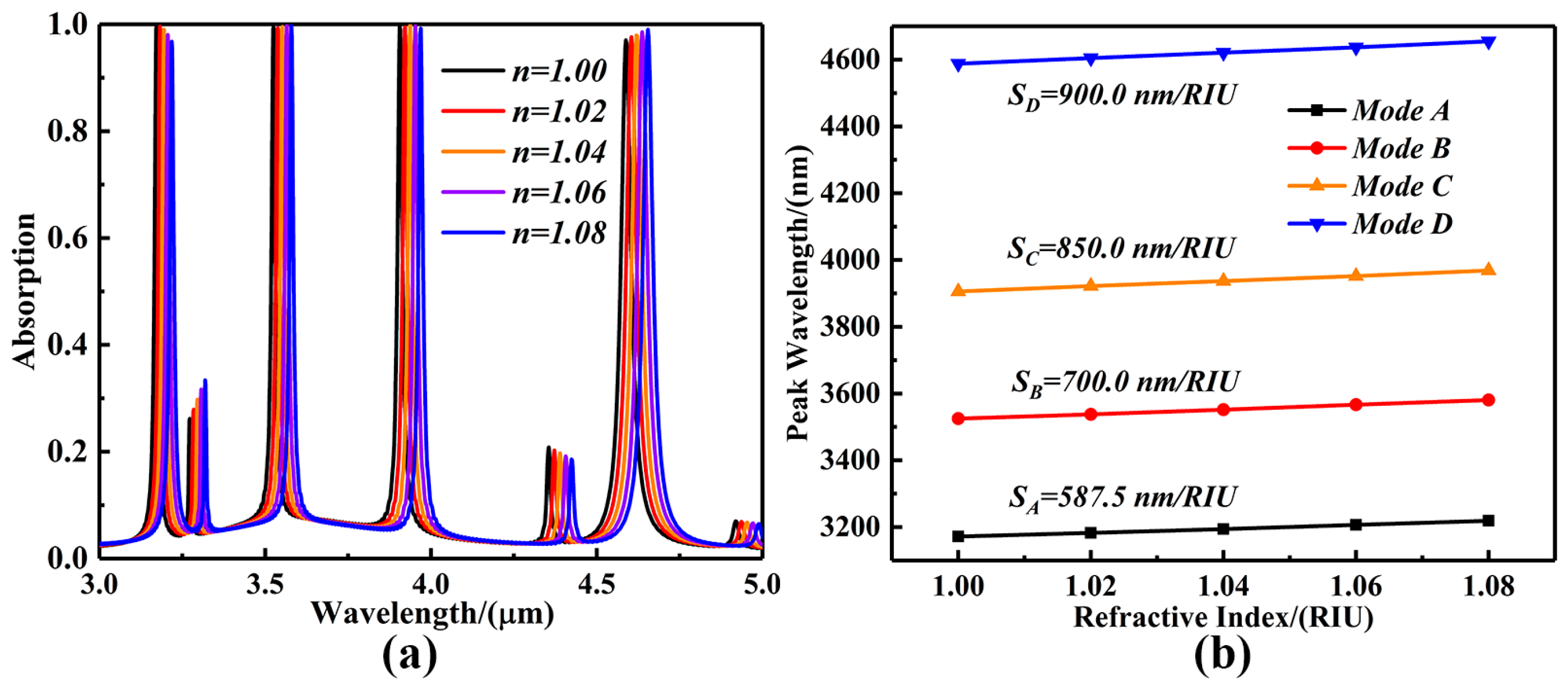

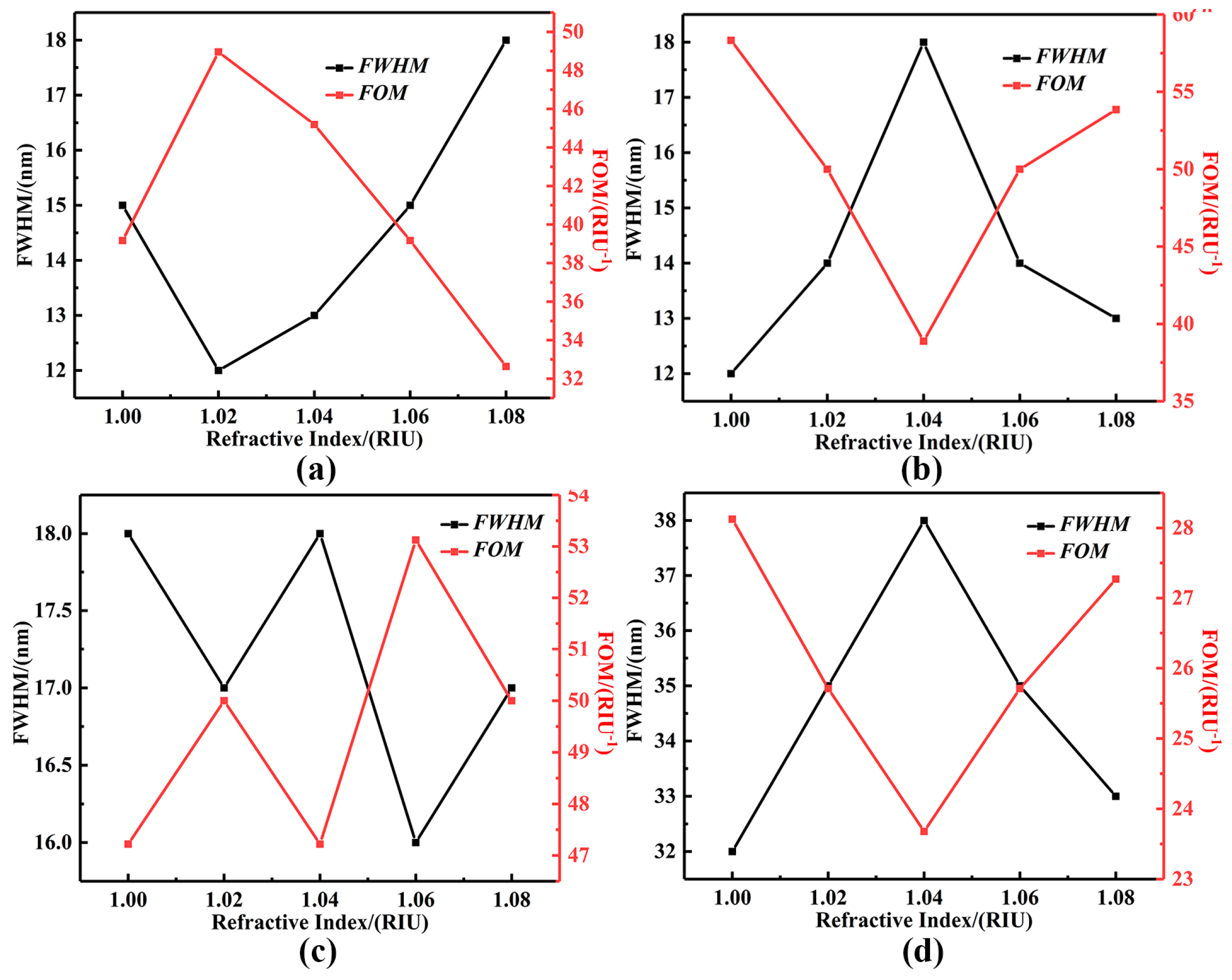

- With the change in refractive index in the test environment, the maximum sensitivity can reach 900.0 nm/RIU and the maximum FOM is 58.34 RIU-1, which is better than that of similar sensors.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Structure and Theory

3. Results and Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| LSPR | Local Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| FWHM | Full Wave at Half Maximum |

| S | Sensitivity |

| FOM | Figure of Merit |

References

- Nan, L.; Mancini, A.; Weber, T.; Seah, G.L.; Cortés, E.; Tittl, A.; Maier, S.A. Angular dispersion suppression in deeply subwavelength phonon polariton bound states in the continuum metasurfaces. Nat. Photon. 2025, 19, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Luo, Z.; Ma, S.; Tao, P.; Song, C.; Wu, J.; Shang, W.; Deng, T. Bioinspired infrared sensing materials and systems. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Cai, M.; Ma, L. Optical transport properties of graphene surface plasmon polaritons in mid-infrared band. Crystals 2019, 9, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Bisht, A.; Scheck, A.; Schunemann, P.G.; Ye, J. Modulated ringdown comb interferometry for sensing of highly complex gases. Nature 2025, 638, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Yin, W.; Gao, B.; Zeng, Q.; Yao, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; et al. Enhancing crystal integrity and structural rigidity of CsPbBr3 nanoplatelets to achieve a narrow color-saturated blue emission. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, D.; Qin, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, C.; Shi, J. A review of nondestructive examination technology for polyethylene pipe in nuclear power plant. Front. Mech. Eng. 2018, 13, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ding, L.; Yi, J.; Wei, Z.; Guo, J. Plasmonics refractive index sensor based on tunable ultra-sharp Fano resonance. Optoelectron. Lett. 2018, 14, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Ou, Z.; Chen, J.Y.; Li, H.; Liu, X.P.; Zeng, L.Z.; Li, J.Q. High sensitivity plasmonic sensor based on Fano resonance with inverted U-shaped resonator. Sensors 2021, 21, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yuan, C.; Li, Z.; Su, J.; Yi, Z.; Yao, W.; Wu, P.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, S.; Pan, M. Multi-band and high-sensitivity perfect absorber based on monolayer graphene metamaterial. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 111, 108227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.N.; Ferdous, M.; Khalek, M.A.; Chakma, S.; Paul, B.K.; Ahmed, K. Design and analysis of biosensor based on surface plasmon resonance. Sens. Bio Sens. Res. 2018, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ming, H. Review of surface plasmon resonance and localized surface plasmon resonance sensor. Photonic Sens. 2012, 2, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthanthiraraj, P.; Sen, A.K. Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) biosensor based on thermally annealed silver nanostructures with on-chip blood-plasma separation for the detection of dengue non-structural protein NS1 antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 132, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constant, T.J.; Hornett, S.M.; Chang, D.E.; Hendry, E. All-optical generation of surface plasmons in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, Y.L.; Byun, K.M. Graphene-on-silver substrates for sensitive surface plasmon resonance imaging biosensors. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armghan, A.; Alsharari, M.; Aliqab, K.; Alsalman, O.; Parmar, J.; Patel, S.K. Graphene twistronics: Tuning the absorption spectrum and achieving metamaterial properties. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Kowerdziej, R.; Pianelli, A.; Parka, J. Graphene-based tunable hyperbolic microcavity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akjouj, A.; Mir, A. Effect of graphene layer on the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and the sensitivity in periodic nanostructure. Photonics Nanostruct. Fundam. Appl. 2018, 31, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.K.; Vishwakarma, M.; Soni, A. Advances and researches on non destructive testing: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 3690–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Yu, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, R.; Ye, H. Ultra-narrow band perfect absorber and its application as plasmonic sensor in the visible region. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gong, C.; He, S. Narrow band perfect absorber for maximum localized magnetic and electric field enhancement and sensing applications. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, H.; Chen, F.; Gong, R. Triple narrow-band plasmonic perfect absorber for refractive index sensing applications of optical frequency. OSA Contin. 2019, 2, 2113–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, A.; Moeferdt, M.; Wolff, C.; Matyssek, C.; Rodríguez-Oliveros, R.; Prohm, C.; Niegemann, J.; Grafström, S.; Eng, L.M.; Busch, K. Second harmonic generation from metal nano-particle resonators: Numerical analysis on the basis of the hydrodynamic drude model. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleitas, A.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Valdés, J.E.N.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Sigarreta, J.M. Analysis of the local Drude model involving the generalized fractional derivative. Optik 2019, 193, 163008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Dong, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, W.; Han, L. Dual-band and dynamic regulated terahertz linear polarization converter based on graphene metasurface. Opt. Commun. 2023, 529, 129042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liang, C.-H. Broadband graphene-based metamaterial absorbers. Opt. Mater. Express 2016, 6, 3036–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, S. Tunable terahertz broadband absorber based on a composite structure of graphene multilayer and silicon strip array. Opt. Commun. 2019, 431, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.F.; Zeng, L.; Liu, G.B.; Huang, T. Tunable linear-to-circular polarization converter using the graphene transmissive metasurface. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 158634–158642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, F.A.; Menon, P.S.; Rajendran, V.; Shaari, S.; Majlis, B.Y. Investigation of graphene-on-metal substrates for SPR-based sensor using finite-difference time domain. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Wang, J.; Li, A.; Xin, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zou, Y. Conductive micropatterns containing photoinduced in situ reduced graphene oxide prepared by ultraviolet photolithography. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ruan, B.; Zhu, J.; Guo, J.; Dai, X.; Xiang, Y. Tunable mid-infrared perfect absorber based on the critical coupling of graphene and black phosphorus nanoribbons. Results Phys. 2019, 15, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upender, P.; Amarjit, K. Numerical investigation of a high-performance MXene and graphene-based metamaterial absorber for terahertz biosensing. Results Phys. 2025, 70, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zeng, L.; Li, J.; Weng, J.; Li, J.; Guo, Z.; Xu, P.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y.; et al. Tunable plasmon-induced transparency with coupled L-shape graphene metamaterial. Results Phys. 2022, 38, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedney, S.D. An anisotropic perfectly matched layer-absorbing medium for the truncation of FDTD lattices. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1996, 44, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, C.; Ren, Y. Broadband terahertz metamaterial absorber based on graphene resonators with perfect absorption. Results Phys. 2021, 26, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Yan, F.; Wang, W.; Tan, S.; Zhang, L.; Bai, Z.; Zhou, H.; Hou, Y. A polarization and angle-insensitive broadband tunable metamaterial absorber using patterned graphene resonators in the terahertz band. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 132, 106513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Liang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Tunable angle-independent refractive index sensor based on Fano resonance in integrated metal and graphene nanoribbons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Luo, M.; Jiao, W.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, J.; Sun, X.; Chen, S.; Wen, Q. Multiscale Magnetic-Electric Synergy in CIP/MXene/Epoxy Nano-micro Composites for Ultra-Broadband Absorption and Enhanced Thermal Conductivity. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 271, 111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Ren, B.; Song, J.; Jiang, Y. Tuning of mid-infrared absorption through phonon-plasmon-polariton hybridization in a graphene/hBN/graphene nanodisk array. Opt. Exp. 2021, 29, 2288–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, V.; Pianelli, A.; Miscuglio, M.; Patra, A.; Maccaferri, N.; Caputo, R.; De Luca, A. Near-and mid-infrared graphene-based photonic architectures for ultrafast and low-power electro-optical switching and ultra-high resolution imaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 12218–12230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Liu, B.W.; Tian, Z.Q.; Ren, B. Determining the interfacial refractive index via ultrasensitive plasmonic sensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10905–10909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Choi, H.H.; Park, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Yoo, J.M.; Lee, H.; Hong, B.H. Enhanced chemical reactivity of graphene by Fermi level modulation. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 5602–5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, A.P.; Janicki, L.; Stokowski, H.S.; Rudzinski, M.; Rozbiegala, E.; Sobanska, M.; Zytkiewicz, R.; Kudrawiec, R. Determination of fermi level position at the graphene/GaN interface using electromodulation spectroscopy. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2001220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xia, H.; Guo, Z.; Li, H.; Xie, D. Polarization-insensitive and tunable plasmon induced transparency in a graphene-based terahertz metamaterial. Opt. Commun. 2018, 424, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynab, S.; Hossein, S. Highly sensitive mid-infrared SPR biosensor for a wide range of biomolecules and biological cells based on graphene-gold grating. Phys. E 2020, 119, 114005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y. Graphene-based materials toward microwave and terahertz absorbing stealth technologies. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1801318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Liu, W.; Tian, J.; Yang, R. Broadband terahertz metamaterial absorber and modulator based on hybrid graphene-gold pattern. Phys. E: Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2022, 140, 115142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Yu, S.; Lu, W.; Hao, Z.; Yi, Z.; Cheng, S.; Tang, B.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Yi, Y. Tunable high-sensitivity four-frequency refractive index sensor based on graphene metamaterial. Sensors 2024, 24, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jiang, W.; Yin, X. Dual-band ultrasensitive terahertz sensor based on tunable graphene metamaterial absorber. Superlattices Microstruct. 2021, 154, 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, K.M.; Alighanbari, A. Terahertz refractive index sensor based on Tamm plasmon-polaritons with graphene. Appl. Opt. 2019, 58, 3604–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, T.; Viola, G.; Kinaret, J.; Fogelström, M.; Tassin, P. High-sensitivity plasmonic refractive index sensing using graphene. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 025103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Cui, J.; Xue, C.; Yan, S. Transmission and refractive index sensing based on Fano resonance in MIM waveguide-coupled trapezoid cavity. AIP Adv. 2019, 7, 015020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Yuan, L.; Lei, J.; Li, X. Enhanced plasmonic-induced absorption using a cascade scheme and its application as refractive-index sensor. Photonic Sens. 2020, 10, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, S.; Bahadori-Haghighi, S. Visible-range double Fano resonance metal-insulator-metal plasmonic waveguide for optical refractive index sensing. Plasmonics 2022, 17, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, H.; Wen, L.; Yi, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, B.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Wu, P. Multi-mode surface plasmon resonance absorber based on dart-type single-layer graphene. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 7821–7829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, E.; Mansouri-Birjandi, M.A.; Tavousi, A. Achieving high sensitivity by adding rings to a plasmonic metasurface with nano-holes. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 299, 117046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, M.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Q. Graphene-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Metasurface for Mid-Infrared Four-Band Ultra-Narrow Absorbing Sensor. Sensors 2025, 25, 7477. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247477

Luo M, Chen Z, Wen Q. Graphene-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Metasurface for Mid-Infrared Four-Band Ultra-Narrow Absorbing Sensor. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7477. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247477

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Min, Zihao Chen, and Qiye Wen. 2025. "Graphene-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Metasurface for Mid-Infrared Four-Band Ultra-Narrow Absorbing Sensor" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7477. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247477

APA StyleLuo, M., Chen, Z., & Wen, Q. (2025). Graphene-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Metasurface for Mid-Infrared Four-Band Ultra-Narrow Absorbing Sensor. Sensors, 25(24), 7477. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247477