IoT-Based System for Real-Time Monitoring and AI-Driven Energy Consumption Prediction in Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Transportation

Abstract

1. Introduction

Related Studies

2. Development of the IoT-Based Monitoring System

2.1. System Architecture

2.2. Designed Hardware

2.3. Communication and Data Flow

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

3.2. Train/Test Split, Cross-Validation, and Metrics

3.3. Models and Hyperparameters

3.3.1. Feature Set

3.3.2. Configuration

3.3.3. Baselines

3.4. Power-Budget Modeling

Measurement Protocol (Power)

4. Results

4.1. Energy Consumption and Battery Sizing

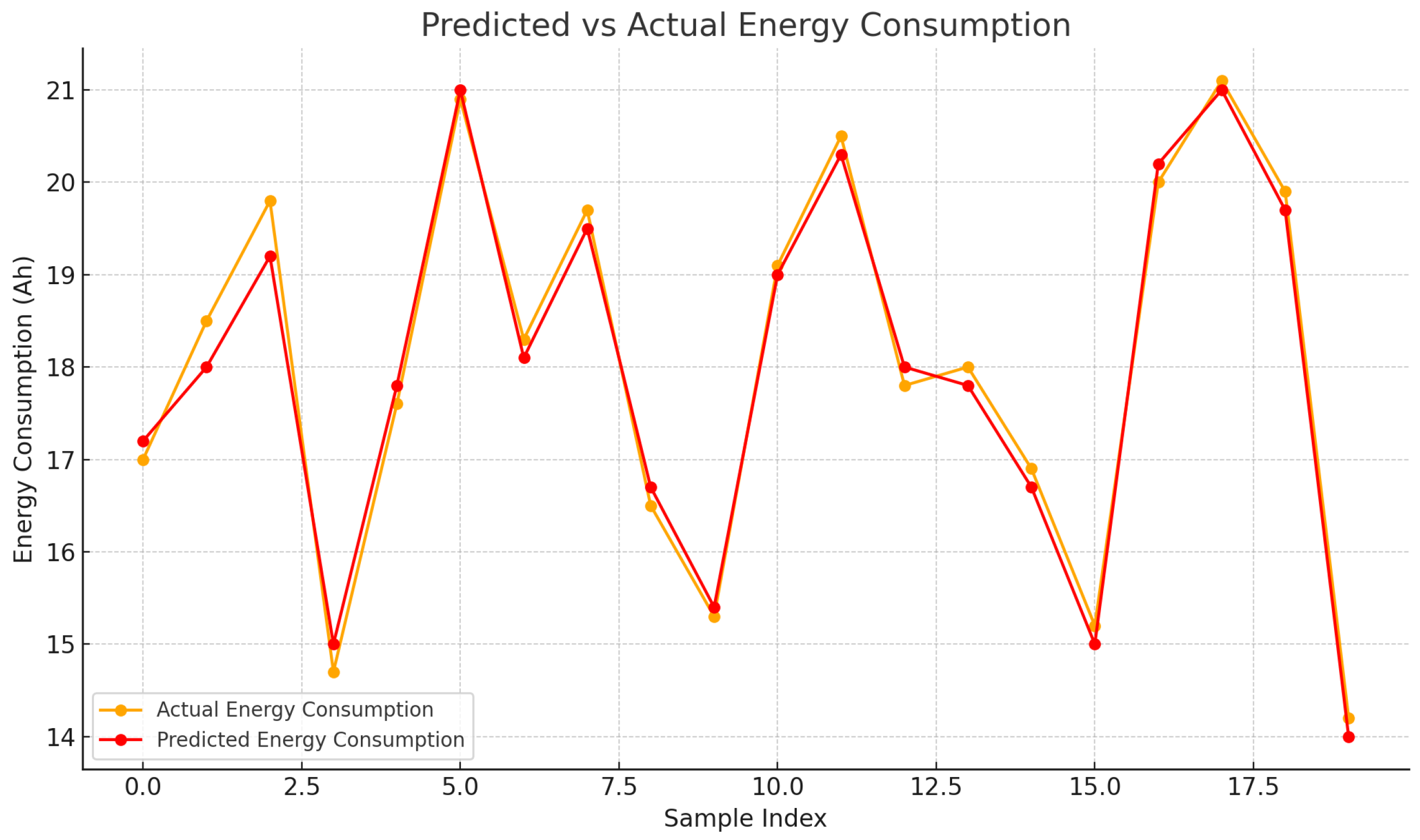

Purpose of the AI (Energy Consumption Prediction)

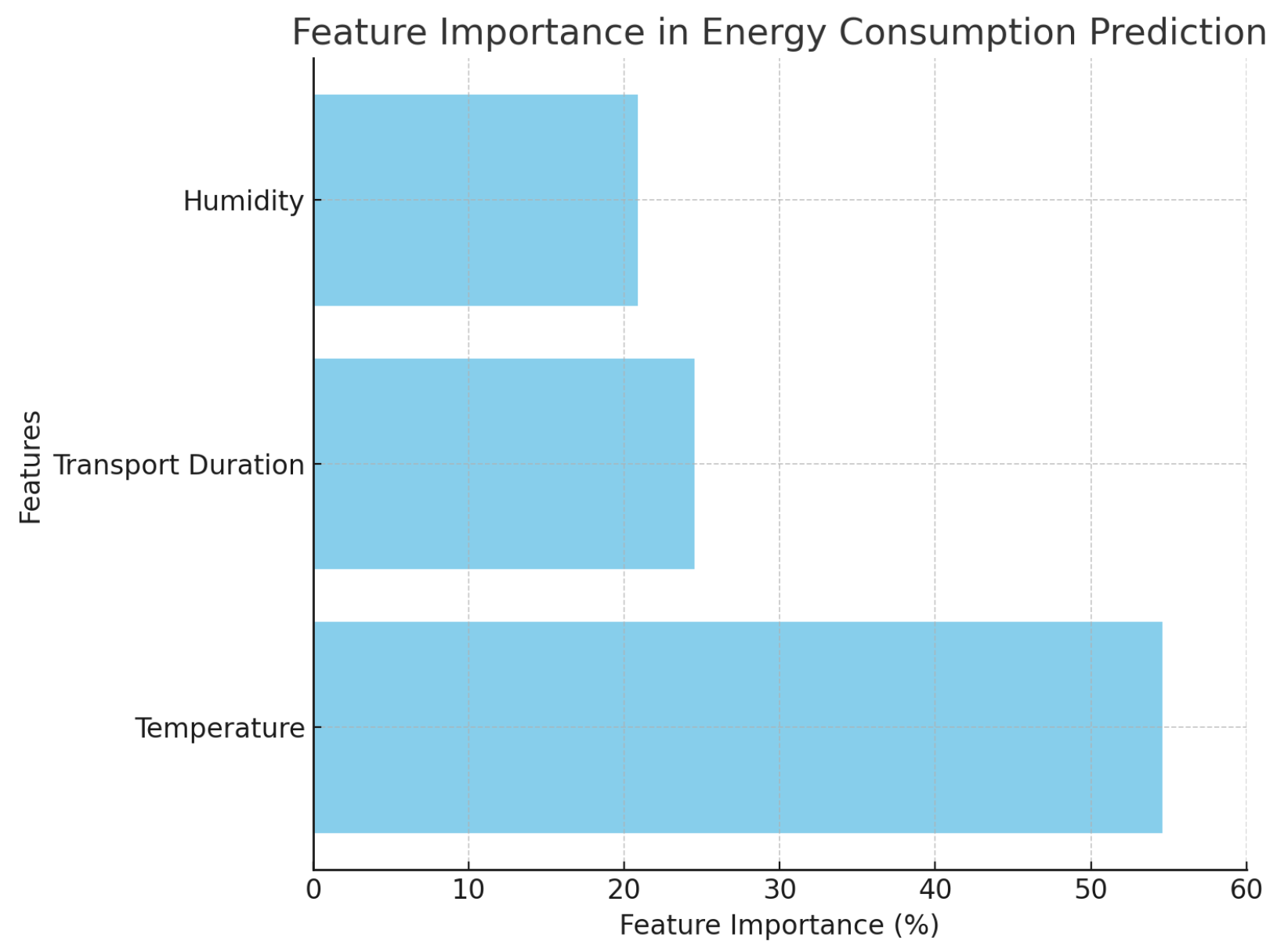

4.2. Model Performance and Feature Importance

Operational Countermeasures (Derived from Predictions)

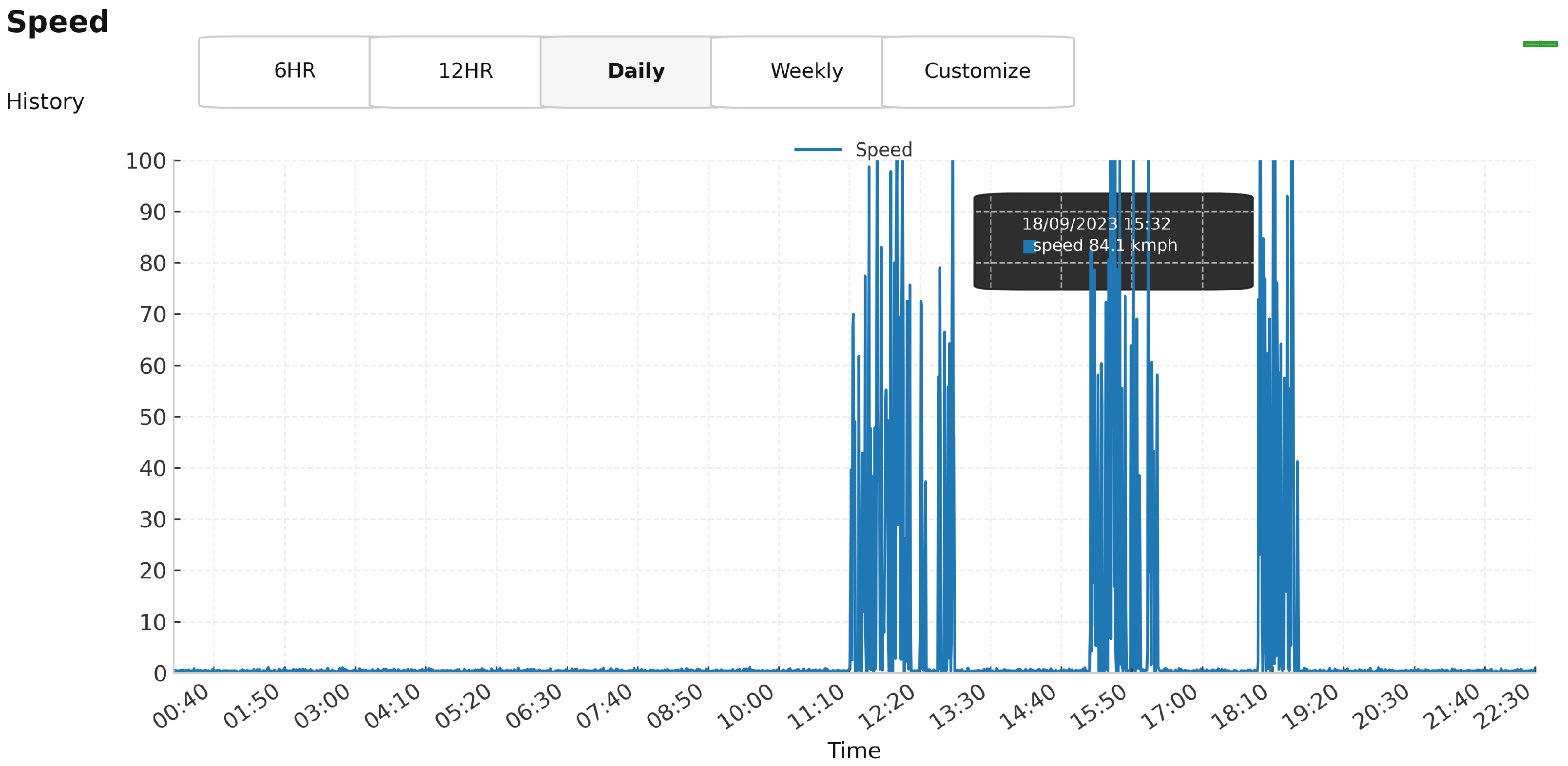

4.3. Field Prototype and Telemetry

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| EMQX | MQTT Broker |

| ESP32 | Embedded SoC MCU |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| k-NN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LR | Linear Regression |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

References

- Rattanakaran, J.; Saengrayap, R.; Aunsri, N.; Padee, S.; Prahsarn, C.; Kitazawa, H.; Bishop, C.F.H.; Chaiwong, S. Performance of Thermal Insulation Covering Materials to Reduce Postharvest Losses in Okra. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanakaran, J.; Saengrayap, R.; Prahsarn, C.; Kitazawa, H.; Chaiwong, S. Application of Room Cooling and Thermal Insulation Materials to Maintain Quality of Okra during Storage and Transportation. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwenya, J.; Saengrayap, S.; Arwatchananukul, S.; Aunsri, N.; Kamyod, C.; Jakkaew, P.; Kitazawa, H.; Mahajan, P.; Padee, S.; Prahsarn, C.; et al. Thermal Insulation Box Design for Maintaining Cool Temperature and the Postharvest Quality of Okra. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 332, 113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzounis, A.; Katsoulas, N.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Internet of Things in Agriculture, Recent Advances and Future Challenges. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 164, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijah, O.; Rahman, T.A.; Orikumhi, I.; Leow, C.Y.; Hindia, M.N. An Overview of Internet of Things (IoT) and Data Analytics in Agriculture: Benefits and Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 3758–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Riaz, S.; Abid, A.; Abid, K.; Naeem, M.A. A Survey on the Role of IoT in Agriculture for the Implementation of Smart Farming. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156237–156271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, U.; Mumtaz, R.; García-Nieto, J.; Hassan, S.A.; Zaidi, S.A.R.; Iqbal, N. Precision Agriculture Techniques and Practices: From Considerations to Applications. Sensors 2019, 19, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, I.; Saha, J.; Venkatasubbu, P.; Ramasubramanian, P. AI Crop Predictor and Weed Detector Using Wireless Technologies: A Smart Application for Farmers. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 11115–11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Ammad-Uddin, M.; Sharif, Z.; Mansour, A.; Aggoune, E.-H.M. Internet-of-Things (IoT)-Based Smart Agriculture: Toward Making the Fields Talk. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 129551–129583. [Google Scholar]

- Mekala, M.; Viswanathan, P. A Survey: Smart Agriculture IoT with Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Microelectronic Devices, Circuits and Systems (ICMDCS), Vellore, India, 10–12 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Parekh, H.; Joshi, S. Modeling the Internet of Things Adoption Barriers in Food Retail Supply Chains. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, V.; Arora, S. Recent Developments of the Internet of Things in Agriculture: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 129924–129957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N.; Dixit, Y.; Al-Mallahi, A.; Bhullar, M.S.; Upadhyay, R.; Martynenko, A. IoT, Big Data, and Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture and Food Industry. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 6305–6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzembrak, Y.; Klüche, M.; Gavai, A.; Marvin, H.J.P. Internet of Things in Food Safety: Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.; Robbemond, R.M.; Verwaart, T.; Wolfert, J.; Beulens, A.J.M. A Reference Architecture for IoT-Based Logistic Information Systems in Agri-Food Supply Chains. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2018, 12, 755–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Kant, K. IoT-Based Sensing and Communications Infrastructure for the Fresh Food Supply Chain. Computer 2018, 51, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Dev, K.; Khowaja, S.A. Flexible Data Integrity Checking with Original Data Recovery in IoT-Enabled Maritime Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavhan, S.; Gupta, D.; Chandana, B.N.; Khanna, A.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. IoT-Based Context-Aware Intelligent Public Transport System in a Metropolitan Area. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6023–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-López, J.; Buendía, M.J.; Toledo, A.; Giménez-Gallego, J.; Torres-Sánchez, R. Monitoring Perishable Commodities Using Cellular IoT: An Intelligent Real-Time Conditions Tracker Design. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, M.; Edwards, P.; Jacobs, N. Recording Provenance of Food Delivery Using IoT, Semantics and Business Blockchain Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS), Granada, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiwartya, O.; Abdullah, A.H.; Cao, Y.; Altameem, A.; Prasad, M.; Lin, C.-T. Internet of Vehicles: Motivation, Layered Architecture, Network Model, Challenges, and Future Aspects. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 5356–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, C.; Doshi, N. Security Challenges in IoT Cyber World. In Security in Smart Cities: Models, Applications, and Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Badhiye, S.S.; Chatur, P.N.; Wakode, B.V. Data Logger System: A Survey. Int. J. Comput. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2011, 1, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Djordjević, M.; Jovičić, B.; Marković, S.; Paunović, V.; Danković, D. A Smart Data Logger System Based on Sensor and IoT Technology as Part of the Smart Faculty. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2020, 12, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.S.; Maulana, M.R.; Mizar, M.A.; Zaeni, I.A.E.; Afandi, A.N.; Irvan, M. Self Energy Management System for Battery Operated Data Logger Device Based on IoT. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering (ICEEIE), Denpasar, Indonesia, 3–5 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hadiatna, F.; Hindersah, H.; Yolanda, D.; Triawan, M.A. Design and Implementation of Data Logger Using Lossless Data Compression Method for IoT. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference on System Engineering and Technology (ICSET), Bandung, Indonesia, 3–4 October 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mabrouki, J.; Azrour, M.; Dhiba, D.; Farhaoui, Y.; El Hajjaji, S. IoT-Based Data Logger for Weather Monitoring Using Arduino-Based WSNs with Remote App and Alerts. Big Data Min. Anal. 2021, 4, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Ivanov, R.; Phan, L.T.; Sokolsky, O.; Weimer, J.; Lee, I. LogSafe: Secure and Scalable Data Logger for IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things Design and Implementation (IoTDI), Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 April 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, S.R.; Karode, A.H.; Suralkar, S.R. Review on IoT-Based Environment Monitoring System. Int. J. Electron. Commun. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tavade, T.; Nasikkar, P. Raspberry Pi: Data Logging IoT Device. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Power and Embedded Drive Control (ICPEDC), Chennai, India, 16–18 March 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Stanley, M.; Spanias, A.; Tepedelenlioglu, C. Integrating Machine Learning in Embedded Sensor Systems for IoT Applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Signal Processing and Information Technology (ISSPIT), Limassol, Cyprus, 12–14 December 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, Y.; Ahmad, F.; Yaqoob, I.; Adnane, A.; Imran, M.; Guizani, S. Internet of Things for Smart Cities: Recent Advances and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2017, 55, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, L.W.; Kwariawan, A.; Lim, R. IoT for Real-Time Data Logger and pH Controller. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Soft Computing, Intelligent System and Information Technology (ICSIIT), Denpasar, Indonesia, 26–29 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Fanariotis, A.; Orphanoudakis, T.; Kotrotsios, K.; Fotopoulos, V.; Keramidas, G.; Karkazis, P. Power-Efficient Machine Learning Models Deployment on Edge IoT Devices. Sensors 2023, 23, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantalis, F.; Koulouras, G.; Karabetsos, S.; Kandris, D. A Review of Machine Learning and IoT in Smart Transportation. Future Internet 2019, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, G.C.G.; Torres, I.C.; de Araújo, Í.B.Q.; Brito, D.B.; de Andrade Barboza, E. A Low-Cost IoT System for Real-Time Monitoring of Climatic Variables and Photovoltaic Generation. Sensors 2021, 21, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M.; Alsharekh, M.F. Design of a Smart Distribution Panelboard Using IoT Connectivity and Machine Learning Techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.H.; Kute, P.D.; More, V.N. IoT-Based Data Processing for Automated Industrial Meter Reader Using Raspberry Pi. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Internet of Things and Applications (IOTA), Pune, India, 22–24 January 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, V.P.; Jain, C.; Chugh, A. IoT-Based Data Logger for Environmental Monitoring. In Innovations in Computer Science and Engineering; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 103, pp. 463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Koushik, M.S.; Srinivasan, M.; Lavanya, R.; Alfred, S.; Setty, S. Design and Development of WSN-Based Data Logger with ESP-NOW Protocol. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Pune, India, 2–4 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, K.; Reddy, G.S.; Makala, R.; Srihari, T.; Sharma, N.; Singh, C. Studies on Energy-Efficient Techniques for Agricultural Monitoring by Wireless Sensor Networks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 113, 109052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palniladevi, P.; Sabapathi, T.; Kanth, D.A.; Kumar, B.P. IoT-Based Smart Agriculture Monitoring Using Renewable Energy Sources. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Vision Towards Emerging Trends in Communication and Networking Technologies (ViTECoN 2023), Vellore, India, 5–6 May 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, K.; Abdelhafid, M.; Kamal, K.; Ismail, N.; Ilias, A. Intelligent Driver Monitoring System: An IoT-Based System for Tracking and Identifying Driving Behavior. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2023, 84, 103704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Chana, I.; Clarke, S. A Survey on IoT Big Data: Current Status, 13 V’s Challenges, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 53, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.; Hawking, P. Big Data Analytics and IoT in Logistics: A Case Study. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 575–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dweik, A.; Muresan, R.; Mayhew, M.; Lieberman, M. IoT-Based Multifunctional Scalable Real-Time Enhanced Road Side Unit for Intelligent Transportation Systems. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Windsor, ON, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, M.; Phadke, A. Internet of Things Based Vehicle Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2017 Fourteenth International Conference on Wireless and Optical Communications Networks (WOCN), Mumbai, India, 24–26 February 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Priyanka, E.B.; Maheswari, C.; Thangavel, S. A Smart-Integrated IoT Module for Intelligent Transportation in Oil Industry. Int. J. Numer. Model. 2021, 34, e2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, Q.; Sotthiwat, E.; Goh, R.S.M.; Liang, X. Blockchain and IoT Data Analytics for Fine-Grained Transportation Insurance. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 24th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), Singapore, 11–13 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1022–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Jachimczyk, B.; Dziak, D.; Czapla, J.; Damps, P.; Kulesza, W.J. IoT On-Board System for Driving Style Assessment. Sensors 2018, 18, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermesan, O.; Friess, P.; Guillemin, P.; Gusmeroli, S.; Sundmaeker, H.; Bassi, A.; Jubert, I.S.; Mazura, M.; Harrison, M.; Eisenhauer, M.; et al. Internet of Things Strategic Research Roadmap. In Internet of Things—Global Technological and Societal Trends from Smart Environments and Spaces to Green ICT; River Publishers: Aalborg, Denmark, 2022; pp. 9–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Potter, A. The Application of Real-Time Tracking Technologies in Freight Transport. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Signal-Image Technologies and Internet-Based Systems (SITIS), Shanghai, China, 16–18 December 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. Logistics 4.0 Solution—New Challenges and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop of Advanced Manufacturing and Automation (IWAMA 2016), Manchester, UK, 10–11 November 2016; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rácz-Szabó, A.; Ruppert, T.; Bántay, L.; Löcklin, A.; Jakab, L.; Abonyi, J. Real-Time Locating System in Production Management. Sensors 2020, 20, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, G.H.; Petreanu, S.; Alexandru, B.; Corpodean, H. IoT-Based Real-Time Production Logistics, Cyber-Physical Process Monitoring, and Industrial AI in Sustainable Smart Manufacturing. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2021, 9, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dintén, R.; García, S.; Zorrilla, M. Fleet Management Systems in the Logistics 4.0 Era: A Real-Time Distributed and Scalable Architectural Proposal. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 217, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, M.N.M.; Ahmad, M. Secure Identification, Traceability and Real-Time Tracking of Agricultural Food Supply During Transportation Using IoT. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 65660–65675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.K.; Da Costa, R.P.F.; Härri, J.; Bonnet, C. Integrating Connected Vehicles in IoT Ecosystems: Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 17th International Symposium on A World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM), Coimbra, Portugal, 21–24 June 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, Z.; Dong, W. Overview of Edge Computing in the Agricultural Internet of Things: Key Technologies, Applications, Challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 141748–141761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gahlawat, V.K.; Rahul, K.; Mor, R.S.; Malik, M. Sustainable Innovations in the Food Industry Through Artificial Intelligence and Big Data Analytics. Logistics 2021, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Huang, A.-Q.; Guo, J. Prediction of Cold Chain Loading Environment for Agricultural Products Based on K-Medoids-LSTM-XGBoost Ensemble Model. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoria Hernandez, P.; Mariñas-Collado, I.; Garcia Sipols, A.; Simon de Blas, C.; Rodríguez Sánchez, M.C. Time Series Forecasting Methods in Emergency Contexts. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spantideas, S.T.; Giannopoulos, A.E.; Trakadas, P. Autonomous Price-Aware Energy Management System in Smart Homes via Actor-Critic Learning with Predictive Capabilities. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 5018–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawson, V.J.; Hughes, B.R. Deep Learning Techniques for Energy Forecasting and Condition Monitoring in the Manufacturing Sector. Energy Build. 2020, 217, 109966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehijananloo, M.; Stopps, H.; McArthur, J.J. Exploring Artificial Intelligence Methods for Energy Prediction in Healthcare Facilities: An In-Depth Extended Systematic Review. Energy Build. 2024, 320, 114598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Joha, M.I.; Nazim, M.S.; Jang, Y.M. Enhancing IoT-Based Environmental Monitoring and Power Forecasting: A Comparative Analysis of AI Models for Real-Time Applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module | Power (A·h/day) |

|---|---|

| ESP32 (active) | 10.368 |

| ESP32 (standby) | 1.555 |

| Temp/RH sensor (active) | 0.1728 |

| Temp/RH sensor (standby) | 0.031 |

| GPS (active) | 1.728 |

| GPS (standby) | 0.2592 |

| microSD (active) | 3.456 |

| microSD (standby) | 0.2592 |

| RTC | 0.1728 |

| Wi-Fi module (active) | 6.912 |

| Wi-Fi module (standby) | 0.155 |

| Total (per day) | 24.620 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamyod, C.; Arwatchananukul, S.; Aunsri, N.; Saengrayap, R.; Tontiwattanakul, K.; Prahsarn, C.; Trongsatitkul, T.; Lerslerwong, L.; Mahajan, P.; Kim, C.-G.; et al. IoT-Based System for Real-Time Monitoring and AI-Driven Energy Consumption Prediction in Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Transportation. Sensors 2025, 25, 7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247475

Kamyod C, Arwatchananukul S, Aunsri N, Saengrayap R, Tontiwattanakul K, Prahsarn C, Trongsatitkul T, Lerslerwong L, Mahajan P, Kim C-G, et al. IoT-Based System for Real-Time Monitoring and AI-Driven Energy Consumption Prediction in Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Transportation. Sensors. 2025; 25(24):7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247475

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamyod, Chayapol, Sujitra Arwatchananukul, Nattapol Aunsri, Rattapon Saengrayap, Khemapat Tontiwattanakul, Chureerat Prahsarn, Tatiya Trongsatitkul, Ladawan Lerslerwong, Pramod Mahajan, Cheong-Ghil Kim, and et al. 2025. "IoT-Based System for Real-Time Monitoring and AI-Driven Energy Consumption Prediction in Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Transportation" Sensors 25, no. 24: 7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247475

APA StyleKamyod, C., Arwatchananukul, S., Aunsri, N., Saengrayap, R., Tontiwattanakul, K., Prahsarn, C., Trongsatitkul, T., Lerslerwong, L., Mahajan, P., Kim, C.-G., Wu, D., & Chaiwong, S. (2025). IoT-Based System for Real-Time Monitoring and AI-Driven Energy Consumption Prediction in Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Transportation. Sensors, 25(24), 7475. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25247475