MAGTF-Net: Dynamic Speech Emotion Recognition with Multi-Scale Graph Attention and LLD Feature Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Handcrafted Feature-Based Methods: These methods employ manually designed acoustic features such as MFCCs and low-level descriptors (LLDs) [13], classified using traditional machine learning models [14]. While simple to implement, these features have limited expressiveness and are sensitive to noise, leading to poor generalization.

- End-to-End Deep Learning Methods: Deep models such as CNNs, RNNs, long short-term memory networks (LSTMs), and Transformers learn features directly from raw speech or spectrograms, improving emotion recognition by automatically extracting rich feature representations [15].

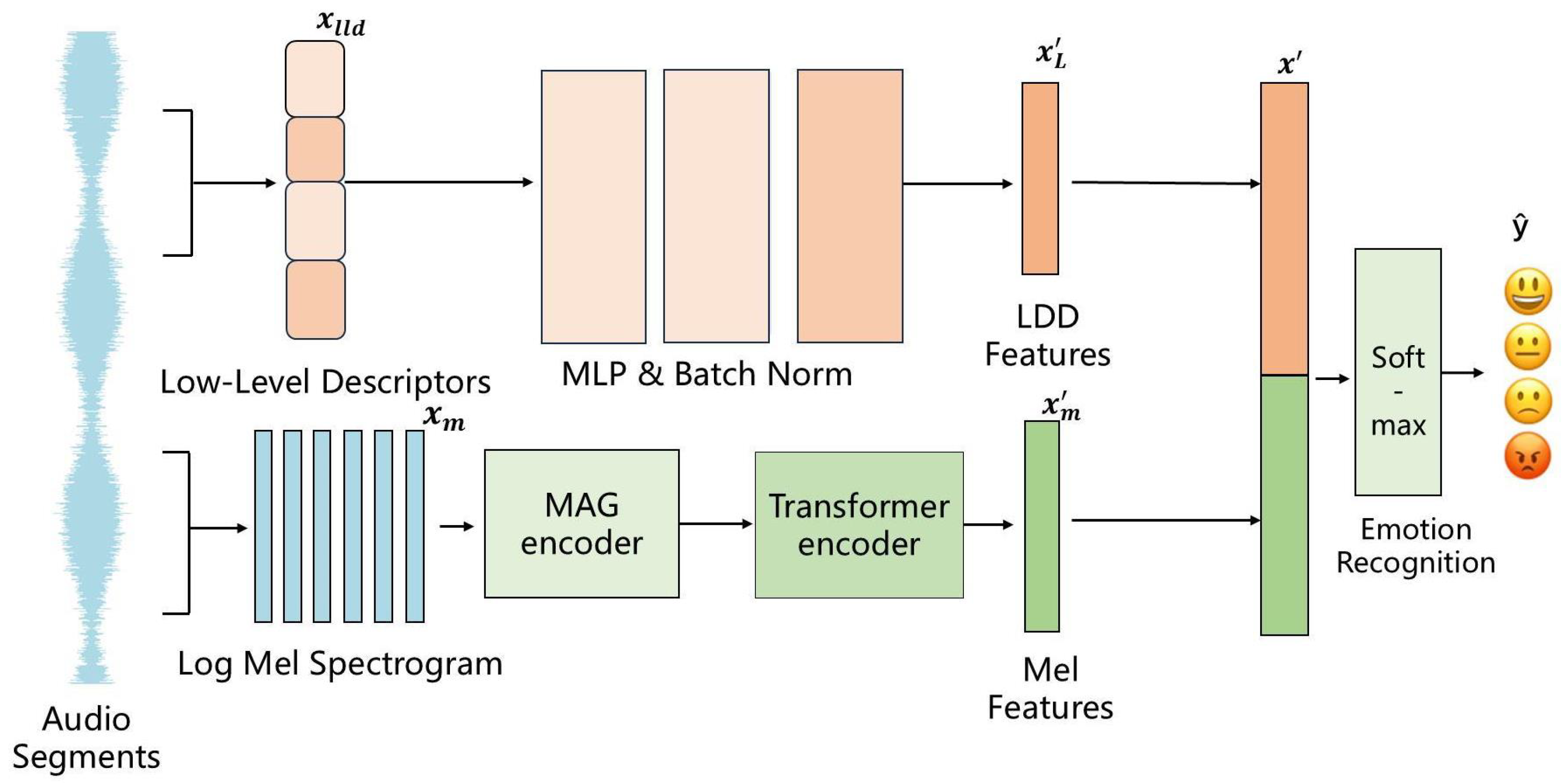

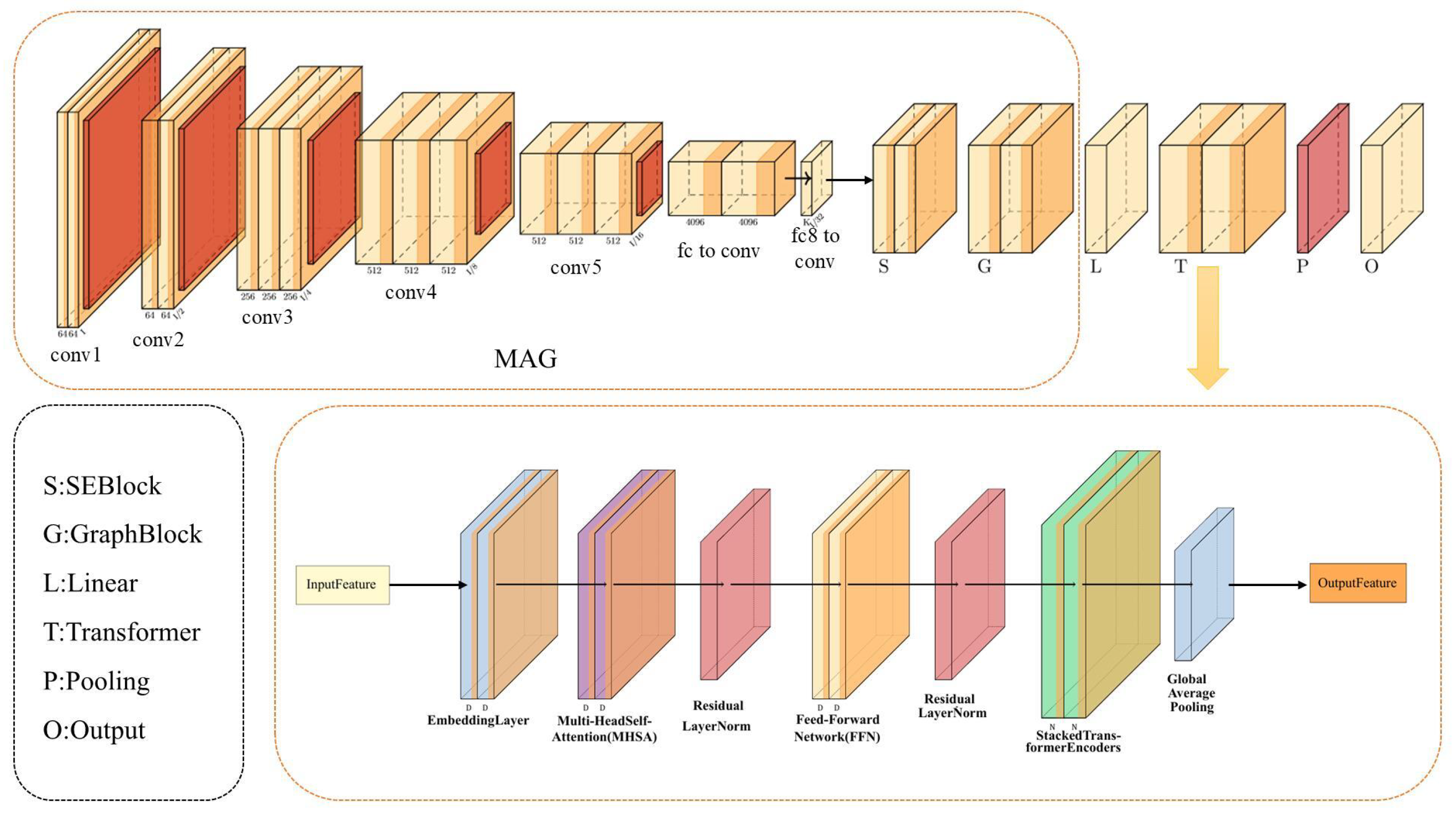

- A Mel-spectrogram Branch: Incorporating a Multi-scale Attention Graph (MAG) module and a Transformer encoder to effectively model both local and global emotional features;

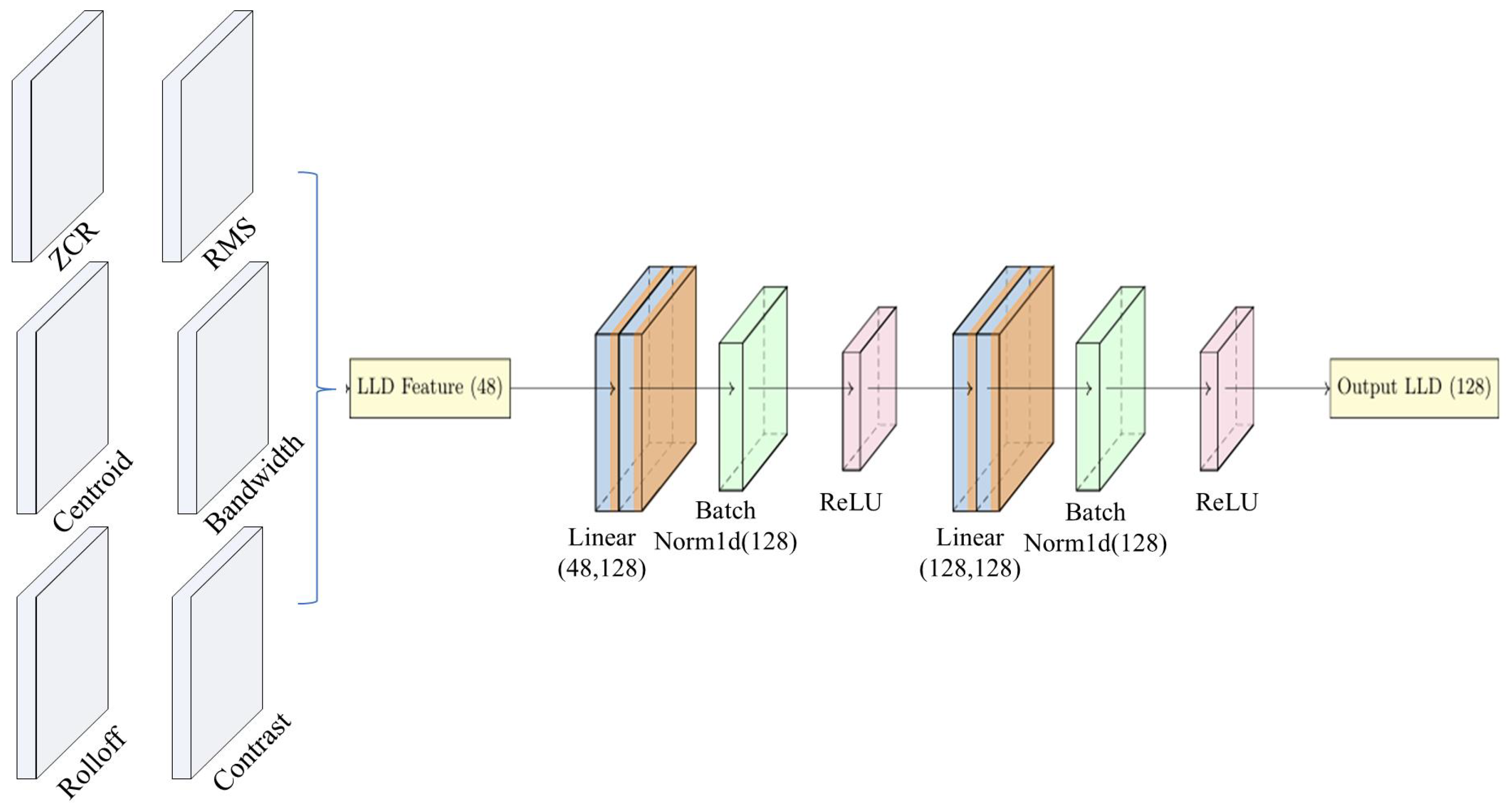

- An LLD Feature Branch: Utilizing multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) to extract and complement fine-grained frame-level emotional cues.

- We propose a novel dual-branch architecture. One branch integrates the MAG and Transformer structures, effectively combining the advantages of multi-scale local feature extraction and global temporal modeling, thereby significantly improving the performance of speech emotion recognition tasks. The other branch deeply explores the low-level descriptor (LLD) features, further enhancing the model’s ability to capture fine-grained emotional details and improving its robustness and generalization capability.

- We introduce a dynamic natural-length modeling mechanism that better adapts to variable-length speech utterances. To address the varying lengths of Mel-spectrogram features in natural speech, this study employs a dynamic padding and masking mechanism for batch-wise alignment and effective frame modeling.The padding operation ensures that the time dimensions of different samples are unified, while the mask matrix selectively masks out the padded frames during the Transformer encoding and global pooling processes, enabling feature learning and aggregation to be performed only on valid frames.This design effectively enhances the accuracy and robustness of sequence modeling.

- Extensive experiments conducted on benchmark datasets (IEMOCAP, EMO-DB, CASIA) demonstrate the effectiveness and generalization ability of the proposed method across different languages and environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Machine Learning-Based Methods

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Methods

2.3. Multi-Branch and Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Methods

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Framework

- Log-Mel spectrogram features are extracted through short-time Fourier transform (STFT) followed by Mel-filterbank projection and logarithmic compression;

- Low-level descriptors (LLDs) are extracted using standard acoustic feature extraction techniques, including short-time energy, zero-crossing rate, spectral centroid, bandwidth, roll-off, and spectral contrast.

3.2. Mel-Spectrogram Branch

3.3. LLD Branch and Feature Fusion

3.4. Interpretability of MAGTF-Net

4. Results

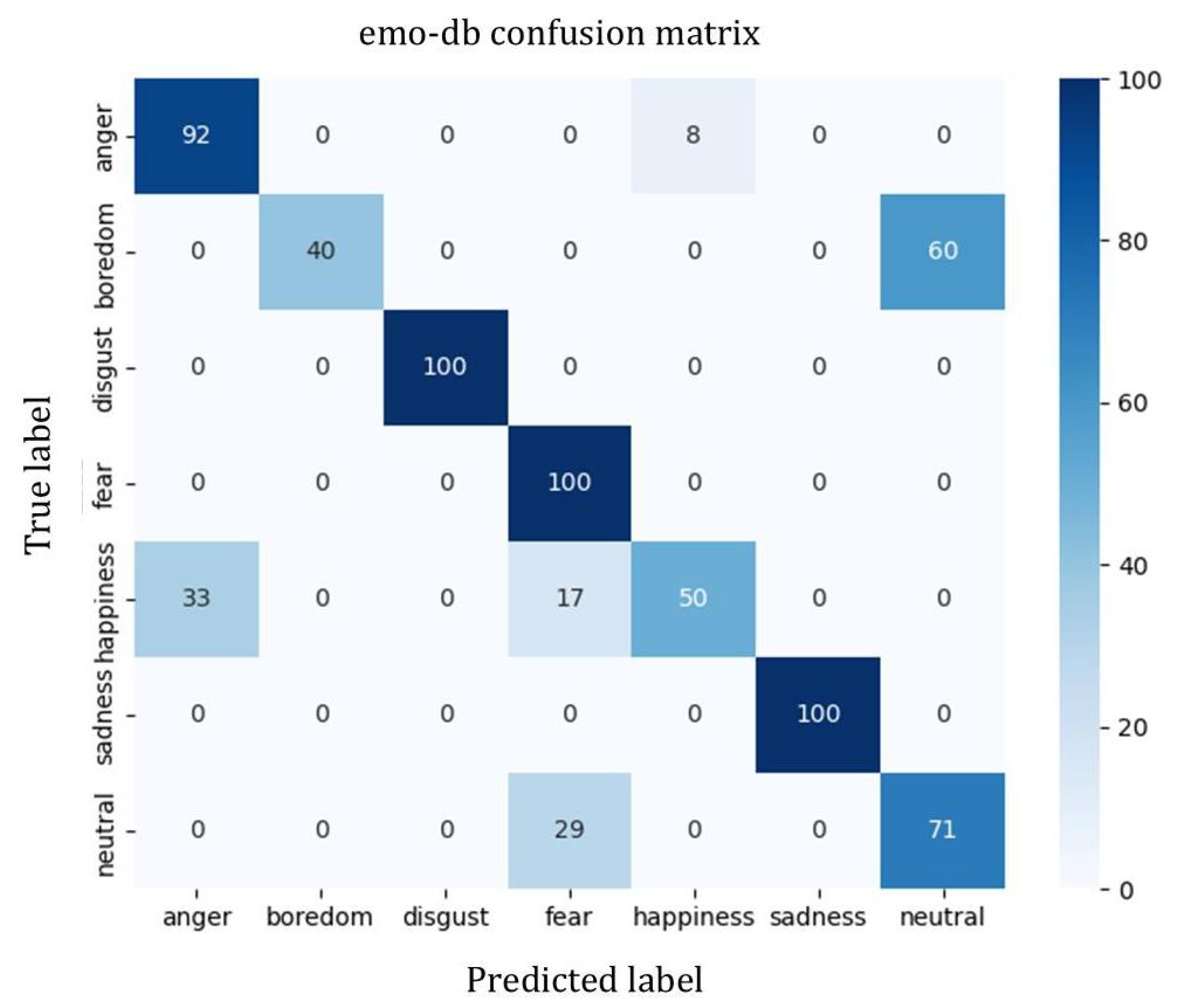

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Comparative Analysis

- (a)

- A clean CNN-BLSTM baseline model was trained and evaluated under the local experimental environment and parameter settings to analyze its emotion recognition performance;

- (b)

- The baseline CNN-BLSTM model was modified by replacing the fixed-length slicing of the audio source with the dynamic sequence modeling approach proposed in this study;

- (c)

- Based on the dynamic sequence modeling version of CNN-BLSTM, the CNN module was replaced with the proposed MAG module, forming the MAG-BLSTM model;

- (d)

- Based on the dynamic sequence modeling CNN-BLSTM model, the BLSTM module was replaced with the Transformer encoder, resulting in the CNN-Transformer model.

4.5. Performance Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, F. Affective information processing and recognizing human emotion. Electron. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2009, 225, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Li, X.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, S. Attention-emotion-enhanced convolutional LSTM for sentiment analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 4332–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals; John Murray: London, UK, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Wei, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Shen, H.T. Improving Pre-trained Model-based Speech Emotion Recognition from a Low-level Speech Feature Perspective. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 10623–10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lv, G.; Zeng, Z. GraphCFC: A Directed Graph Based Cross-Modal Feature Complementation Approach for Multimodal Conversational Emotion Recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Kang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S. Automatic assessment of depression and anxiety through encoding pupil-wave from HCI in VR scenes. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, B.; Rigoll, G.; Lang, M. Hidden Markov model-based speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Hong Kong, China, 6–10 April 2003; Volume 2, p. II-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Guan, L. Recognizing Human Emotional State from Audiovisual Signals. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2008, 10, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Tu, J.; Pianfetti, B.; Huang, T.S. Audio–Visual Affective Expression Recognition Through Multistream Fused HMM. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2008, 10, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Huang, T.; Gao, W. Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Discriminant Temporal Pyramid Matching. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 20, 1576–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.B.; Yusoof, M.A.M.; Don, Z.M.; Malekzadeh, M. Speech emotion recognition research: An analysis of research focus. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2018, 21, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, B.; Batliner, A.; Steidl, S.; Seppi, D. Recognising realistic emotions and affect in speech: State of the art and lessons learnt from the first challenge. Speech Commun. 2011, 53, 1062–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ayadi, M.; Kamel, M.S.; Karray, F. Survey on speech emotion recognition: Features, classification schemes, and databases. Pattern Recognit. 2011, 44, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.R.; Islam, S.; Islam, A.M.; Shatabda, S. An ensemble 1D-CNN-LSTM-GRU model with data augmentation for speech emotion recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 218, 119633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, A.; Zeng, Y.; Hu, H. Multimodal Boosting: Addressing Noisy Modalities and Identifying Modality Contribution. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 3018–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Si, Y.; Chen, C.; Rajan, D.; Chng, E.S. Speech emotion recognition with co-attention based multi-level acoustic information. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 7367–7371. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; Song, W.; Liang, Z.; Chen, X. A New Network Structure for Speech Emotion Recognition Research. Sensors 2024, 24, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, Y.; Han, S.; Lee, S.; Shin, J.W. Speech Emotion Recognition Incorporating Relative Difficulty and Labeling Reliability. Sensors 2024, 24, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Fu, S.; Wang, F. Decision tree SVM model with Fisher feature selection for speech emotion recognition. EURASIP J. Audio Speech Music Process. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dujaili, M.J.; Ebrahimi-Moghadam, A.; Fatlawi, A. Speech emotion recognition based on SVM and KNN classifications fusion. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2021, 11, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, I.; Navas, E.; Hernáez, I. Feature Analysis and Evaluation for Automatic Emotion Identification in Speech. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2010, 12, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, M.S.; Ranjan, A.; Yadav, J.; Deepak, A. A survey of speech emotion recognition in natural environment. Digit. Signal Process. 2021, 110, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrish, A.; Majumder, N.; Bharadwaj, R.; Mihalcea, R.; Poria, S. A review of deep learning techniques for speech processing. Inf. Fusion 2023, 99, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanagaraja, T.; Ho, M.K.; Khong, A.W.H.; Wang, Y. End-to-End Speech Emotion Recognition Using Multi-Scale Convolution Networks. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12–15 December 2017; pp. 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, S.; Rana, R.; Khalifa, S.; Jurdak, R.; Qadir, J.; Schuller, B. Survey of deep representation learning for speech emotion recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021, 14, 1634–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, C.; Dang, J.; Chng, E.S.; Li, H. Representation learning with spectro-temporal-channel attention for speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 6304–6308. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B. A Transformer-Based Model With Self-Distillation for Multimodal Emotion Recognition in Conversations. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chen, H.; Hu, G.; He, L.; Zhao, C. Explainability of Speech Recognition Transformers via Gradient-Based Attention Visualization. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 1395–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Guan, W.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, Z. Multi-modal speech emotion recognition using self-attention mechanism and multi-scale fusion framework. Speech Commun. 2022, 139, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ding, S.; Wang, L.; Dang, J. Dstcnet: Deep spectro-temporal-channel attention network for speech emotion recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 36, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Kang, X.; Ren, F. Dual-tbnet: Improving the robustness of speech features via dual-transformer-bilstm for speech emotion recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 31, 2193–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Chen, Q.; You, X. MelTrans: Mel-Spectrogram Relationship-Learning for Speech Emotion Recognition via Transformers. Sensors 2024, 24, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, D. Transformer-Driven Affective State Recognition from Wearable Physiological Data in Everyday Contexts. Sensors 2025, 25, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kim, D.H. Graph Neural Network-Based Speech Emotion Recognition: A Fusion of Skip Graph Convolutional Networks and Graph Attention Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, D.; Altarawneh, E.; Jenkin, M.; Papagelis, M. SERC-GCN: Speech emotion recognition in conversation using graph convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Yang, K.; Zhang, S.; Hu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Chen, H. A Flexible Diffusion Convolution for Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 3118–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sheng, Z.; Li, X.; Gao, X.; Hao, Z.; Yang, L.; Nie, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, W.; Cui, B. Acceleration algorithms in GNNs: A survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2025, 37, 3173–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rong, Y.; Guo, Z.; Chen, N.; Xu, T.; Tsung, F.; Li, J. Human Mobility Modeling during the COVID-19 Pandemic via Deep Graph Diffusion Infomax. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hang, C.N.; Yu, P.D.; Chen, S.; Tan, C.W.; Chen, G. MEGA: Machine Learning-Enhanced Graph Analytics for Infodemic Risk Management. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 6100–6111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Byun, S.; Jung, K. Multimodal speech emotion recognition using audio and text. In Proceedings of the IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Athens, Greece, 18–21 December 2018; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, T.; Bhattacharya, U.; Chandra, R.; Bera, A.; Manocha, D. M3ER: Multiplicative multimodal emotion recognition using facial, textual, and speech cues. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-20), New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 1359–1367. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Gueaieb, W.; El Saddik, A.; Kwon, S. MSER: Multimodal speech emotion recognition using cross-attention with deep fusion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 245, 122946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, F.; Paeschke, A.; Rolfes, M.; Sendlmeier, W.F.; Weiss, B. A database of German emotional speech. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2005—Eurospeech, 9th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–8 September 2005; Volume 5, pp. 1517–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Busso, C.; Bulut, M.; Lee, C.C.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Mower, E.; Kim, S.; Chang, J.N.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S.S. IEMOCAP: Interactive emotional dyadic motion capture database. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2008, 42, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, M.; Jia, H. Design of Speech Corpus for Mandarin Text-to-Speech. In Proceedings of the Blizzard Challenge 2008 Workshop, Brisbane, Australia, 21 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Satt, A.; Rozenberg, S.; Hoory, R. Efficient emotion recognition from speech using deep learning on spectrograms. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2017—18th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Stockholm, Sweden, 20–24 August 2017; pp. 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Tashev, I. Learning utterance-level representations for speech emotion and age/gender recognition using deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–9 March 2017; pp. 5150–5154. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; He, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H. 3-D convolutional recurrent neural networks with attention model for speech emotion recognition. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2018, 25, 1440–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, D.; Yin, D. A DenseNet-GRU technology for Chinese speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers of Electronics, Information and Computation Technologies, Changsha, China, 21–23 May 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Li, Q.; Fu, S.; Li, P. Speech emotion recognition based on genetic algorithm–decision tree fusion of deep and acoustic features. ETRI J. 2022, 44, 462–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Sun, C.; Wei, X.; Zhao, L. Speech emotion recognition using channel attention mechanism. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA), Hangzhou, China, 7–9 April 2023; pp. 680–684. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.W.; Rudnicky, A. Exploring wav2vec 2.0 fine tuning for improved speech emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

| Models | WA (%) | UA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| (a) CNN-BLSTM | 53.64 | 61.04 |

| (b) D_CNN-BLSTM | 62.79 | 63.82 |

| (c) D_MAG-BLSTM | 69.83 | 67.57 |

| (d) D_CNN-Transformer | 66.38 | 64.56 |

| (e) MAG-Transformer | 69.15 | 70.86 |

| Models | WA (%) | UA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| (a) CNN-BLSTM | 68.52 | 63.71 |

| (b) D_CNN-BLSTM | 70.37 | 70.62 |

| (c) D_MAG-BLSTM | 75.93 | 76.56 |

| (d) D_CNN-Transformer | 77.78 | 74.71 |

| (e) MAG-Transformer | 83.33 | 79.11 |

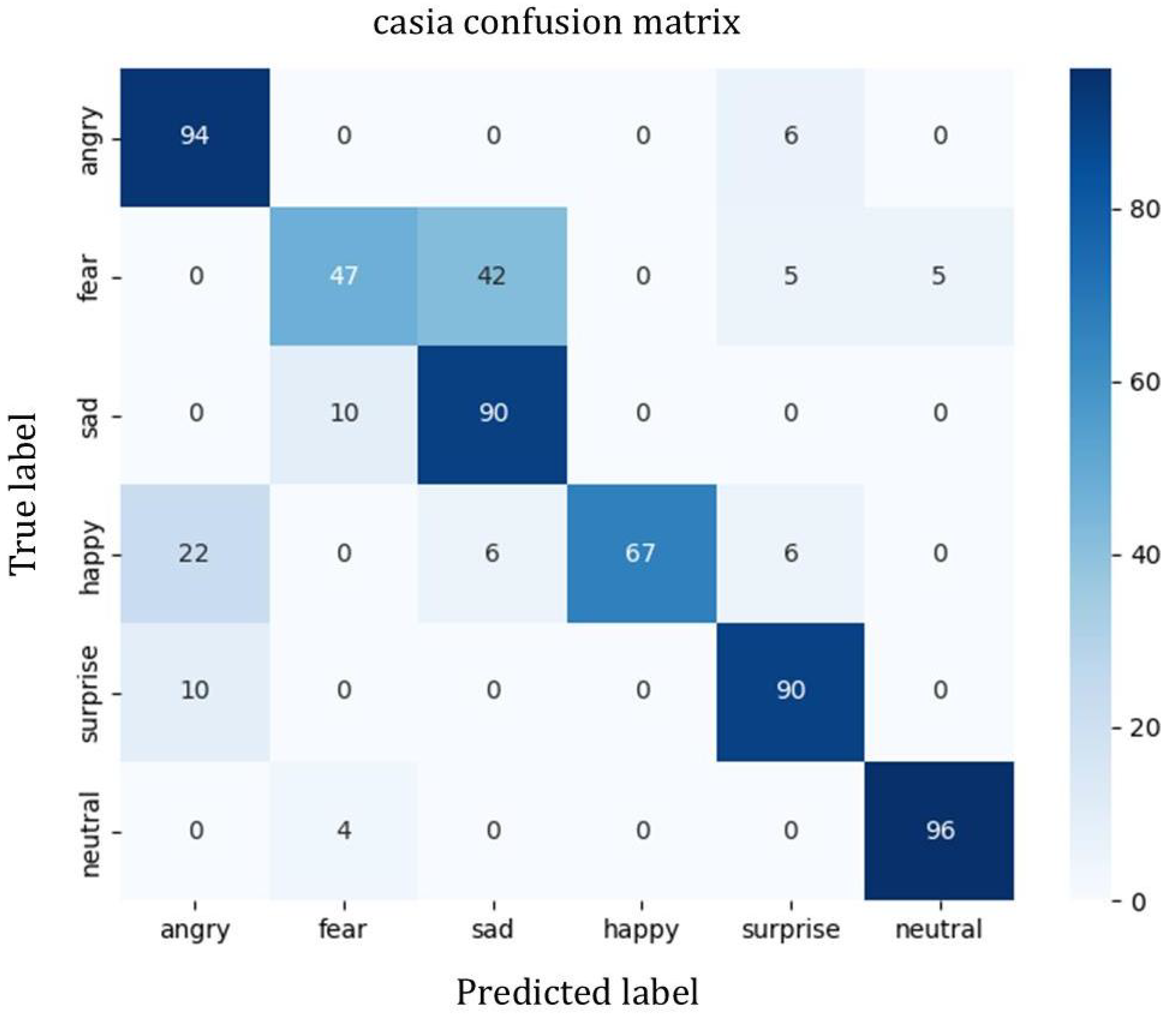

| IEMOCAP | CASIA | EMO-DB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | |

| Angry | 66.67 | 81.48 | 73.33 | 71.43 | 93.75 | 81.08 | 85.71 | 92.31 | 88.89 |

| Sad | 83.78 | 59.62 | 69.66 | 67.86 | 90.48 | 77.55 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Neutral | 72.65 | 68.55 | 70.54 | 96.15 | 96.15 | 96.15 | 62.50 | 71.43 | 66.67 |

| Happy | 59.26 | 69.57 | 64.00 | 100.00 | 66.67 | 80.00 | 75.00 | 50.00 | 60.00 |

| Disgust | – | – | – | – | – | – | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Fear | – | – | – | 75.00 | 47.37 | 58.06 | 76.92 | 100.00 | 86.96 |

| Surprise | – | – | – | 85.71 | 90.00 | 87.80 | – | – | – |

| Bored | – | – | – | – | – | – | 100.00 | 40.00 | 57.14 |

| Models | CASIA | IEMOCAP | EMO-DB |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNN-ELM [48] | – | 0.580 | 0.809 |

| 3DRNN+Attention [49] | – | 0.647 | 0.828 |

| Dual-TBNet [32] | 0.957 | 0.648 | 0.841 |

| DenseNet-GRU [50] | 0.800 | 0.631 | 0.820 |

| SVM+Decision Tree [51] | 0.853 | – | 0.858 |

| CNN+ChannelAttention [52] | 0.887 | – | 0.846 |

| Wav2Vec2.0 [53] | – | 0.631 | 0.820 |

| Ours | 0.812 | 0.700 | 0.812 |

| Models | UA | WA |

|---|---|---|

| -LLD | 0.649 | 0.648 |

| -GraphBlock | 0.740 | 0.722 |

| FusionNet | 0.833 | 0.791 |

| Kernel Set | UA (%) | WA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 70.81 | 66.67 | |

| 80.58 | 79.63 | |

| 71.37 | 68.52 | |

| 66.02 | 61.11 | |

| 80.23 | 77.78 | |

| 66.16 | 68.52 | |

| 77.52 | 75.93 | |

| 80.27 | 78.33 | |

| (Full-MAG) | 79.11 | 83.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, S.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z. MAGTF-Net: Dynamic Speech Emotion Recognition with Multi-Scale Graph Attention and LLD Feature Fusion. Sensors 2025, 25, 7378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237378

Zhu S, Xie Y, Wang Z. MAGTF-Net: Dynamic Speech Emotion Recognition with Multi-Scale Graph Attention and LLD Feature Fusion. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237378

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Shiyin, Yinggang Xie, and Zhiliang Wang. 2025. "MAGTF-Net: Dynamic Speech Emotion Recognition with Multi-Scale Graph Attention and LLD Feature Fusion" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237378

APA StyleZhu, S., Xie, Y., & Wang, Z. (2025). MAGTF-Net: Dynamic Speech Emotion Recognition with Multi-Scale Graph Attention and LLD Feature Fusion. Sensors, 25(23), 7378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237378