1. Introduction

Instrumented insoles represent a significant breakthrough in wearable health technology, offering a non-invasive and convenient method for capturing real-time biomechanical and physiological data. By integrating diverse sensor technologies into their design, these insoles facilitate ongoing analysis of plantar pressure distribution, gait dynamics, and postural control. In recent years, instrumented insoles have found widespread application in clinical settings such as diabetic foot management, postural rehabilitation, and fall prevention among the elderly, as well as in fitness and sports [

1]. Their ability to continuously monitor gait symmetry, weight distribution, and balance under dynamic conditions provides valuable insights into neuromuscular control and rehabilitation progress [

2]. Plantar pressure analysis has become an essential diagnostic and monitoring method for conditions like diabetic foot ulcers (DFU), musculoskeletal disorders, peripheral neuropathies, and movement disorders, including Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Excessive plantar pressures, particularly in the forefoot and heel, are associated with skin breakdown and ulcer development, underscoring the importance of precise, ongoing monitoring in clinical settings [

2,

3,

4].

Pressure sensors are key to these systems because they turn mechanical forces into electrical signals that can be measured and analyzed [

2]. Common types are Force-Sensitive Resistors (FSR), capacitive sensors, and piezoelectric sensors [

1,

3]. These sensors facilitate the estimation of key biomechanical parameters, such as Center of Pressure (CoP) and Ground Reaction Force (GRF), which are essential for evaluating balance, posture, and movement [

4]. Tracking CoP helps evaluate balance and disease progression, while GRF data give detailed information about walking phases and force distribution [

4,

5,

6]. CoP trajectories are particularly useful for assessing balance control and disease progression, while GRF data provide quantitative insights into gait phases and force distribution [

4,

5,

6].

With advances in wearable technology, two main categories of plantar sensing systems have emerged: instrumented insoles and smart insoles [

6]. While both rely on similar sensing principles, they differ in autonomy, data processing capabilities, and functionality. Instrumented insoles focus primarily on biomechanical data acquisition, such as plantar pressure or GRF, for offline analysis in clinical or research environments [

7,

8]. Traditionally equipped with resistive or capacitive sensors, they have evolved to integrate inertial sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers) to capture dynamic information on movement and balance [

9]. In contrast, smart insoles incorporate onboard microcontrollers, wireless communication modules, and real-time feedback algorithms, allowing data to be processed and transmitted instantaneously [

9,

10]. This integration enables autonomous operation in both clinical and daily-use contexts. Consequently, instrumented insoles remain dominant in controlled laboratory and diagnostic applications, whereas smart insoles extend to sports performance monitoring, preventive healthcare, and assistive technologies [

10].

Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions between these two technologies.

Smart insole systems frequently incorporate additional sensing components, including inertial measurement units (IMUs), temperature sensors, and humidity sensors, to enhance diagnostic capabilities [

10,

11,

12,

13]. IMUs facilitate detailed analysis of gait dynamics, fall detection, and motion segmentation. Temperature and humidity sensors are essential for diabetic foot monitoring and skin health assessment [

3,

10]. The integration of these multimodal sensors enables more comprehensive evaluations of gait and foot health, thereby supporting improved clinical decision-making and enhancing the reliability of real-world monitoring.

Pressure sensors are the core components in both instrumented and smart insoles and are generally categorized as resistive, piezoelectric, or capacitive types [

3,

7]. FSR sensors function by altering resistance in response to applied force, offering cost-effective and adaptable solutions for distributed pressure mapping [

8]. Piezoelectric sensors generate electrical charges when mechanically deformed, making them particularly suitable for detecting dynamic pressure changes during gait [

5]. Capacitive sensors, which detect changes in capacitance between conductive plates, provide linear responses and low energy consumption, but are susceptible to humidity and electromagnetic interference [

13]. Therefore, selecting the appropriate sensor type requires careful consideration of accuracy, stability, and cost in relation to the specific application.

The design of insole-based systems is contingent upon both the selection of sensor technology and the strategic deployment of sensors. High-resolution configurations utilize extensive sensor arrays distributed across the plantar surface to generate comprehensive pressure mappings. Conversely, simplified prototypes incorporate a limited number of sensors, strategically located at biomechanically significant regions such as the hallux, metatarsal heads, and heel, to balance functionality with practicality [

8,

10,

12].

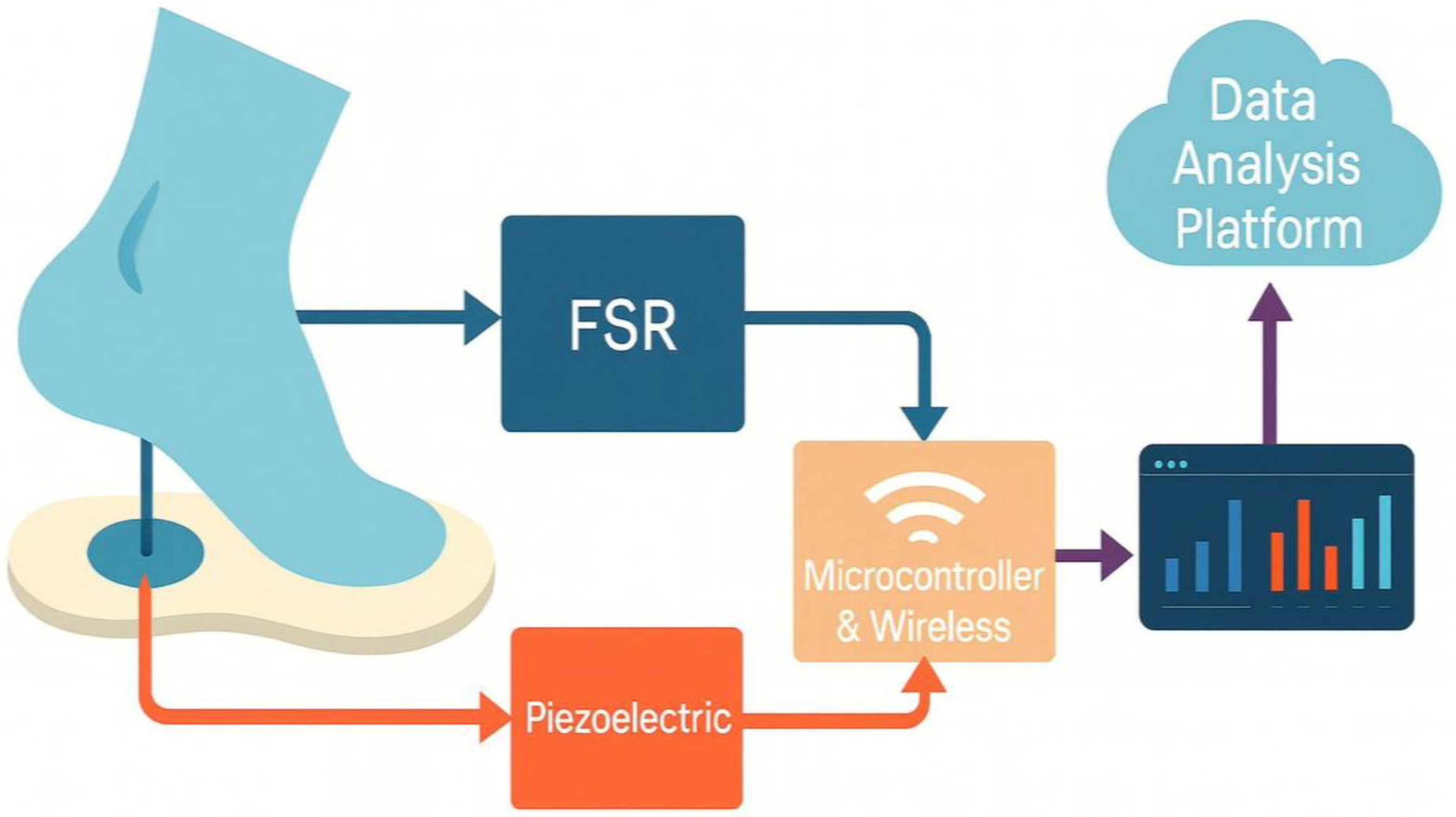

Figure 1 illustrates, in a simple and minimalistic manner, the operation of sensors attached to an insole under applied pressure. The diagram also presents the essential hardware components and software required for the equipment to function.

The scope of applications for instrumented and intelligent insoles encompasses healthcare, rehabilitation, athletic performance, and everyday activity tracking. Within the healthcare sector, these systems are essential for identifying abnormal plantar pressures, especially among diabetic patients, where ongoing monitoring can help prevent the development of ulcers and associated complications [

12,

14]. In rehabilitation, they allow real-time tracking of gait and posture parameters, facilitating patient progress evaluation and treatment optimization [

5,

10]. In sports, the ability to measure ground reaction forces, pressure distribution, and gait symmetry supports performance enhancement and injury prevention strategies [

10]. The combination of portability, affordability, and sensor versatility makes smart insoles a key tool for both clinical and real-world biomechanics research.

Despite growing research efforts, few studies have experimentally validated the use of low-cost FSR and piezoelectric sensors under controlled mechanical loading conditions relevant to rehabilitation. Existing research relies heavily on computational modelling or commercial systems, often lacking standardized testing protocols and reproducible experimental validation. Addressing this gap is crucial for establishing consistent and comparable data for wearable gait monitoring systems. This study aims to experimentally compare the performance of FSR and piezoelectric sensors embedded in an insole under compressive load, evaluating their sensitivity, repeatability, and suitability for plantar pressure monitoring in clinical rehabilitation settings. The results provide a methodological foundation for developing an insole system with highly precise static and dynamic sensing capabilities, thereby enhancing the accuracy and clinical utility of wearable gait monitoring technologies.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Response Recorded by Sensors

3.1.1. FSR Sensor Response

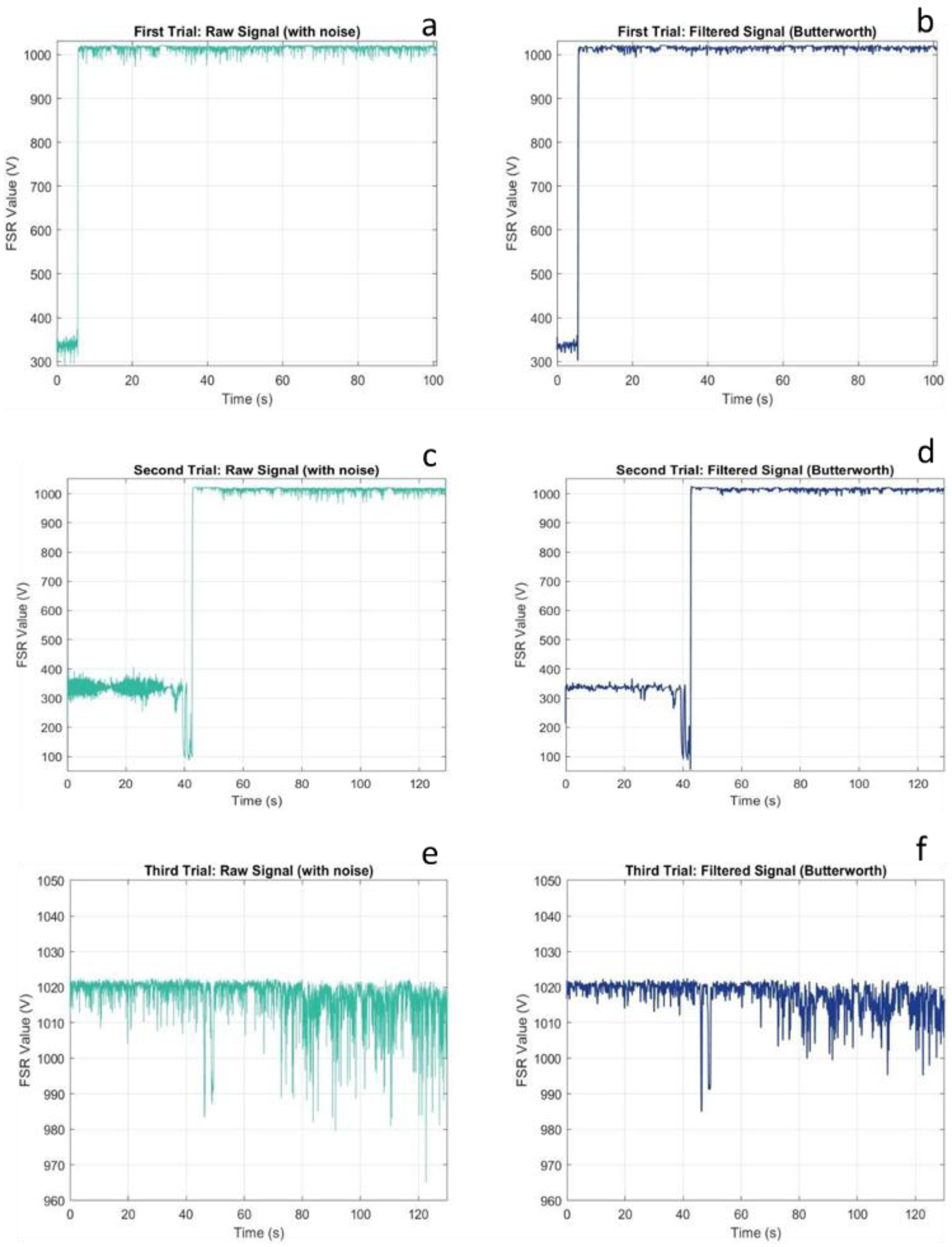

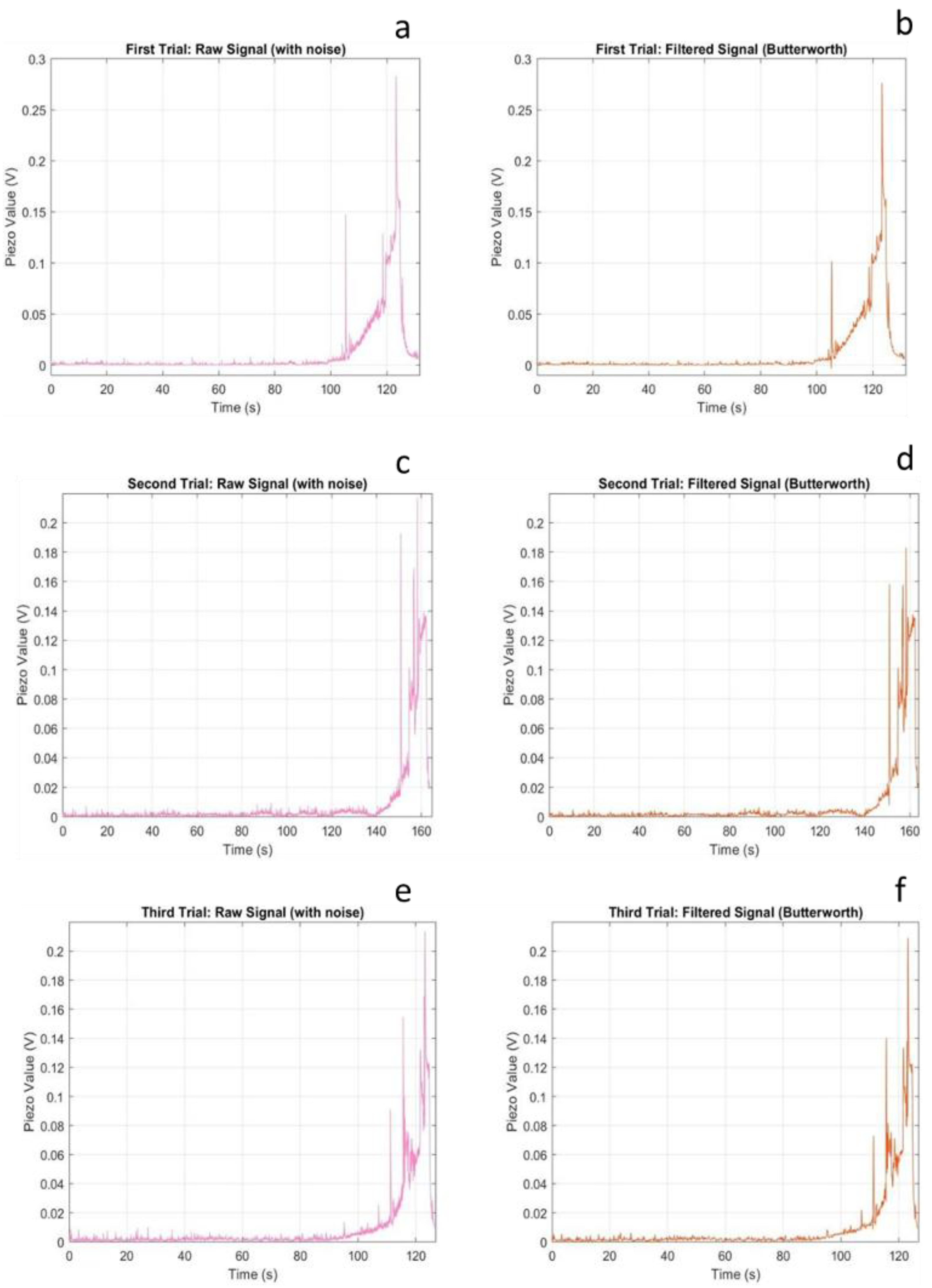

Figure 4 presents the voltage response characteristics of the FSR sensor across three successive compression trials, displaying both raw and filtered signals to illustrate the effectiveness of noise reduction preprocessing.

The FSR sensor exhibited a non-zero baseline voltage even under no-load conditions, a characteristic that requires careful consideration in calibration protocols. The offset voltage, ranging from approximately 0.05 to 0.15 V across trials, is attributed to the temporary wire connections secured with Kapton tape. Unlike soldered connections, which provide stable electrical contact, tape-based connections introduce variable contact resistance that fluctuates with minor mechanical disturbances. This phenomenon has significant implications for sensor deployment: while the offset itself can be compensated through baseline subtraction, the underlying contact instability may contribute to measurement uncertainty during dynamic loading.

Despite this baseline artifact, the sensor demonstrated reliable transition detection between unloaded and loaded states. Upon load application, the FSR exhibited characteristic rapid voltage increase, reaching saturation within 2–3 s. This saturation behaviour is inherent to the sensor’s design specifications, which define a nominal operating range of 0.2 to 20 N. The applied compressive load clearly exceeded this threshold, driving the sensor into its saturation regime where further load increases produce negligible voltage changes.

From a clinical monitoring perspective, this saturation characteristic presents both limitations and opportunities. The limited dynamic range constrains the sensor’s utility for quantifying high-magnitude plantar pressures, such as those encountered during running or in individuals with elevated body mass [

18,

19]. However, the stable saturated output provides a reliable binary indicator of sustained load presence, a feature potentially valuable for applications such as standing posture monitoring or detection of prolonged pressure exposure in diabetic foot care, where the primary concern is identifying areas experiencing continuous loading rather than precise force quantification [

20,

21]. The second compression trial revealed progressive performance degradation, characterized by increased signal noise and a prolonged onset time of saturation. This comportment is characteristic of polymer-based resistive sensors subjected to repeated mechanical stress. The conductive polymer composite that forms the sensing element experiences microstructural changes under cyclic loading: polymer chains may undergo plastic deformation, conductive particle networks can be disrupted, and adhesive layer integrity may degrade [

22]. These mechanisms collectively reduce sensor responsiveness and increase susceptibility to noise [

23]. The extended saturation onset observed in the second trial-approximately 5 s compared to 2–3 s in the first trial, suggests diminished sensitivity to applied force. This nonlinear degradation pattern indicates that the sensor’s transduction mechanism was compromised, potentially through partial delamination of sensing layers or alteration of the conductive particle network. The absence of soldered connections likely exacerbated this degradation by allowing micromotion at electrical interfaces, introducing additional mechanical stress cycles beyond the intended compressive loading [

23,

24]. By the third trial, the sensor exhibited complete saturation throughout the measurement period, indicating irreversible damage to the sensing element. This failure mode, characterized by sustained maximum output regardless of applied load, renders the sensor incapable of distinguishing between different loading states. Such performance represents complete loss of measurement functionality and would necessitate sensor replacement in any practical application.

These findings underscore critical considerations for FSR sensor deployment in rehabilitation monitoring systems. First, sensor durability under repeated loading must be carefully evaluated relative to intended application duration and loading frequency. Short-term monitoring applications may tolerate gradual sensitivity degradation, while long-term continuous monitoring would require periodic sensor replacement or more robust sensor technologies. Second, signal conditioning and connection methods significantly impact measurement reliability. Future implementations should prioritize soldered connections or alternative secure fastening methods to minimize contact resistance variability. Third, integration of accelerometers or other motion sensors could enable detection of wire movement or mechanical disturbances, allowing differentiation between true pressure signals and motion artifacts [

25,

26].

3.1.2. Piezoelectric Sensor Response

Figure 5 presents the electrical response characteristics of the piezoelectric sensor across three compression trials, revealing markedly different behavior compared to the FSR sensor.

First, it is important to clarify that to ensure consistent comparison between material deformation and sensor output, both trials were analysed over the same time interval, given the longer response duration in the second test.

Regarding the data gathered in the trials, the piezoelectric sensor exhibited fundamentally different operational characteristics compared to the FSR, originating from distinct transduction mechanisms. While FSR sensors measure quasi-static force through resistance changes, piezoelectric sensors respond to dynamic mechanical stress by generating transient electrical charges. This distinction is evident in the observed signal patterns: the piezoelectric sensor produces sharp, well-defined voltage peaks that coincide with rapid load changes, while maintaining a near-zero baseline output during steady-state conditions [

27,

28].

The sensor’s initial response in the first trial demonstrated its optimal operating characteristics. Starting from a true zero baseline with minimal noise oscillations, the sensor generated distinct voltage spikes reaching peak amplitudes of approximately 1.5–2.0 V upon load application. These peaks exhibited rapid rise times (<0.5 s) and equally rapid decay, reflecting the sensor’s inherent high-pass filtering behavior. The piezoelectric effect generates charge proportional to the rate of mechanical strain rather than absolute strain magnitude, explaining why the sensor responds primarily to transient loading events rather than sustained pressure [

9].

The second trial revealed important temporal dynamics in the performance of piezoelectric sensors. The voltage peaks appeared with greater temporal separation and demonstrated more gradual rise characteristics compared to the first trial. This alteration can be attributed to the extended rest interval between trials, which allowed complete dissipation of residual charge within the piezoelectric element and capacitance in the measurement circuit. When the sensor begins from a fully discharged state, the initial response to loading exhibits modified characteristics as the charge distribution re-establishes within the piezoelectric material. The third trial demonstrated remarkable consistency with previous measurements, with only minor variations in peak timing and amplitude. This reproducibility stands in stark contrast to the progressive degradation observed in the FSR sensor, reflecting the fundamental robustness of the piezoelectric transduction mechanism. Piezoelectric materials generate an electrical response through deformation of their crystalline structure, rather than relying on polymer chain mobility or conductive particle networks. This mechanism exhibits minimal hysteresis and fatigue under moderate loading conditions, contributing to excellent long-term stability [

29,

30].

The observed signal consistency across trials provides strong evidence for the suitability of piezoelectric sensors in applications requiring repeated measurements over extended periods. While the FSR demonstrated significant performance degradation after just three loading cycles, the piezoelectric sensor maintained its response characteristics, suggesting potential for thousands of loading cycles before considerable performance degradation occurs. This durability advantage is particularly relevant for continuous gait monitoring applications where sensors may experience hundreds to thousands of loading cycles daily. However, the piezoelectric sensor’s fundamental limitation, inability to measure static loads, constrains its application scope. The sensor’s high-pass filtering characteristic means that a constant pressure, regardless of its magnitude, produces a zero-output voltage. This behavior makes piezoelectric sensors unsuitable for applications requiring sustained pressure monitoring, such as evaluating standing posture or detecting prolonged localized pressure in diabetic foot care. The sensor’s optimal application domain is in detecting transient events, such as heel strikes, toe-offs, sudden weight shifts, and other dynamic loading transitions that characterize gait and movement analysis.

3.2. Prototypes Compression Response

The analysis of stress-strain relationships for both prototypes provides insight into the mechanical behavior of the insole substrate and its interaction with embedded sensors. These measurements establish baseline mechanical properties essential for interpreting sensor responses and evaluating prototype suitability for plantar pressure monitoring applications.

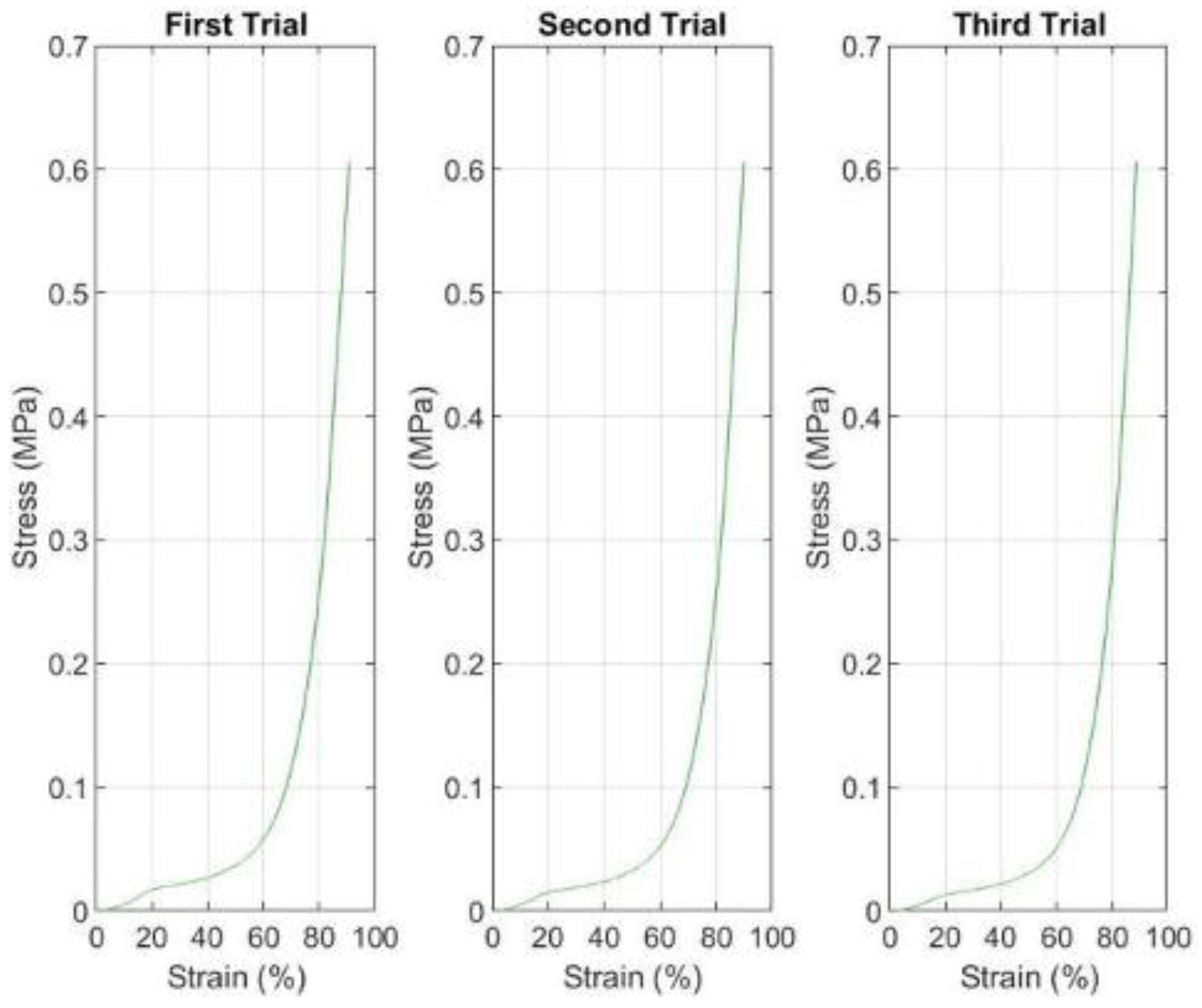

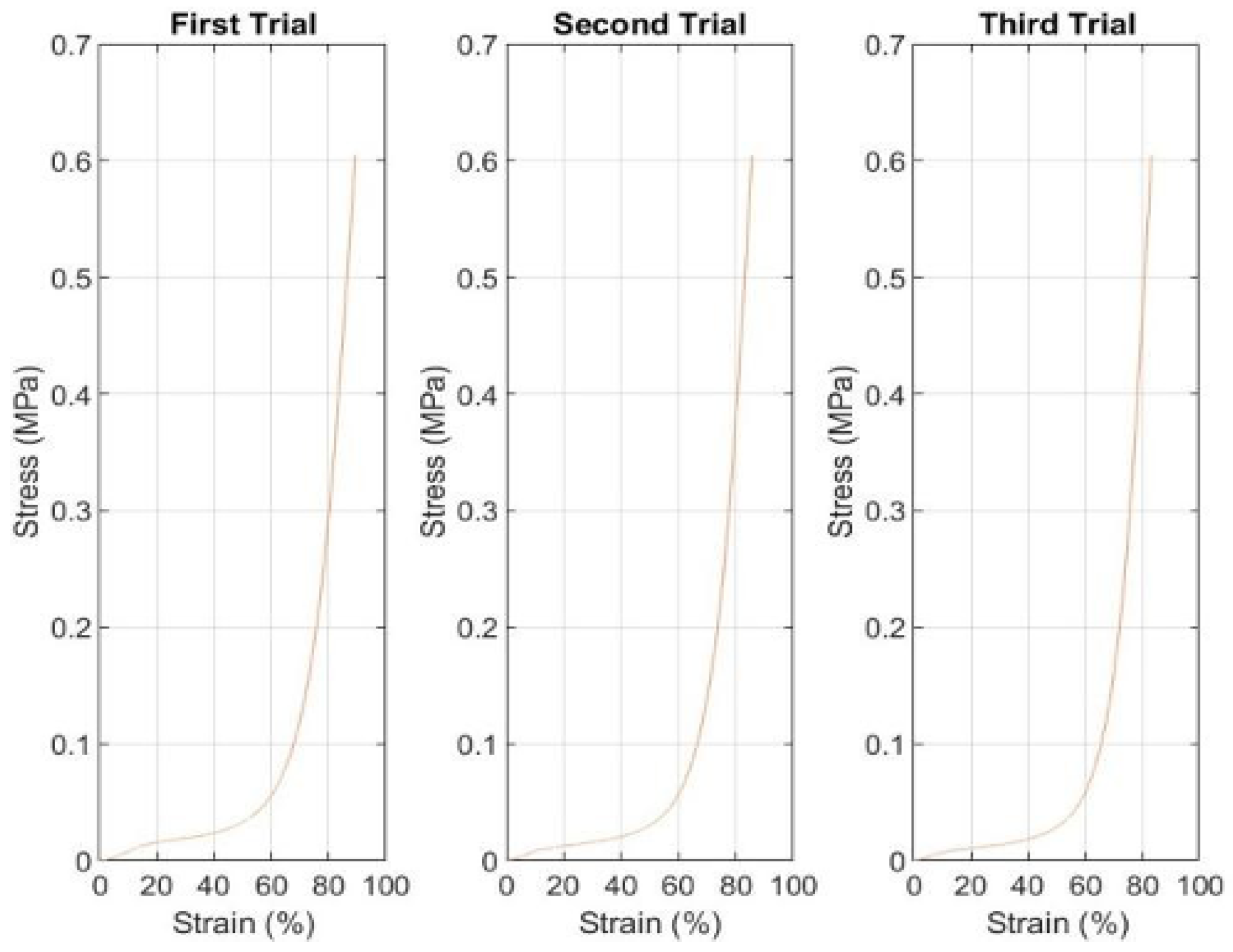

Figure 6 presents the stress-strain curves for the FSR-equipped prototype across three compression trials. The curves exhibit characteristic behavior of closed-cell foam materials commonly used in footwear applications: an initial low-modulus region where cell walls bend and buckle, followed by a transition to higher stiffness as cells collapse and material densification occurs.

The three trials demonstrated remarkable consistency, with curves nearly superimposing throughout the loading range. This reproducibility indicates that the insole material experienced minimal permanent deformation, with elastic recovery occurring effectively between trials. The absence of significant hysteresis or residual strain suggests that the material remained within its elastic operating regime, an essential characteristic for sensors intended for repeated use.

A minor discontinuity observed around 20 s in all three trials corresponds to a momentary clamp adjustment during testing. This artifact, while producing a small perturbation in the stress-strain relationship, does not compromise overall data integrity. More significantly, the calculated stress values should be interpreted with appropriate consideration of measurement limitations. The nominal contact area used for stress calculation was based on the clamp geometry rather than the actual contact area between clamp and insole surface. Given the compressible nature of the insole material, the true contact area is likely increased during compression, suggesting that reported stress values may overestimate actual stress magnitudes. However, since this systematic error affects all measurements consistently, relative comparisons between trials and between sensor types remain valid.

Figure 7 presents corresponding stress-strain data for the piezoelectric sensor prototype. The mechanical response mirrors that of the FSR prototype, exhibiting the same characteristic two-phase behavior: initial compliant response followed by stiffening at higher strains.

Interestingly, the piezoelectric prototype exhibited slightly greater temporal spacing between consecutive compression cycles compared to the FSR prototype. This observation may reflect subtle differences in insole material properties resulting from manufacturing variability. Even nominally identical insoles produced through commercial manufacturing processes can exhibit variations in foam density, cell structure, or thickness distributions. Such variations, while typically small, can influence mechanical response characteristics, particularly the rate of elastic recovery following compression.

Alternative explanations for the temporal variation include differences in experimental protocol execution, such as variations in the rest period between trials or minor differences in clamp positioning. The operator’s manual control of timing and positioning introduces inherent variability that, while minimized through standardized procedures, cannot be eliminated without fully automated testing protocols.

Despite these temporal variations, the three trials for the piezoelectric prototype demonstrated excellent consistency in mechanical response magnitude and curve shape. This consistency reinforces the conclusion that both insole materials exhibited stable mechanical behavior throughout testing, providing reliable platforms for sensor evaluation. The insoles’ ability to recover elastically between loading cycles without significant property changes suggests they would maintain functional performance through multiple use cycles in practical applications.

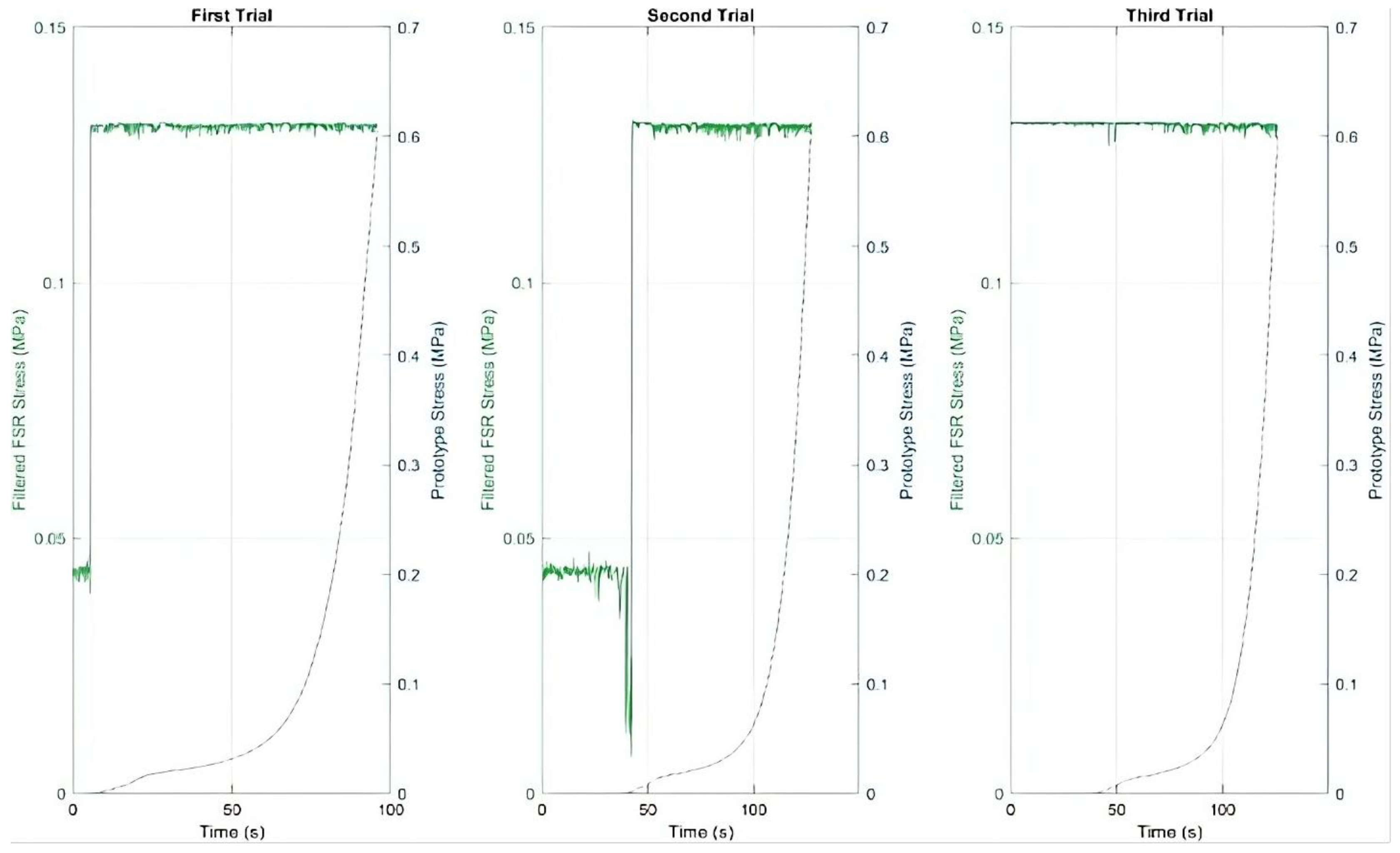

3.3. Integrated Sensor-Substrate Response Analysis

The relationship between sensor electrical outputs and mechanical loading of the insole substrate provides critical insight into each sensor type’s operational characteristics and application suitability. By correlating these signals, we can identify how effectively each sensor transduces mechanical stimuli into electrical signals and understand the implications for rehabilitation monitoring applications.

3.3.1. FSR Sensor-Substrate Correlation

Figure 8 presents the simultaneous measurement of FSR voltage output (left axis) and applied mechanical stress (right axis) throughout three compression trials. This dual-axis representation enables direct visualization of the sensor’s response characteristics relative to physical stimulus.

The initial portion of each curve demonstrates a consistent increase, indicating that the sensor responds coherently to the onset of material deformation. In each trial, however, the FSR signal reaches its saturation limit relatively quickly, while the mechanical stress continues to increase. This saturation is consistent across trials and reflects the known limitation of FSR, which provide reliable measurements only within a limited load range (approximately 0.2 to 20 N). Beyond this range, the sensor output stabilizes and does not reflect further increases in mechanical stress.

Despite this limitation in measurement range, the sensor maintains a stable output level once saturated, which can still serve as a useful indicator of sustained load presence.

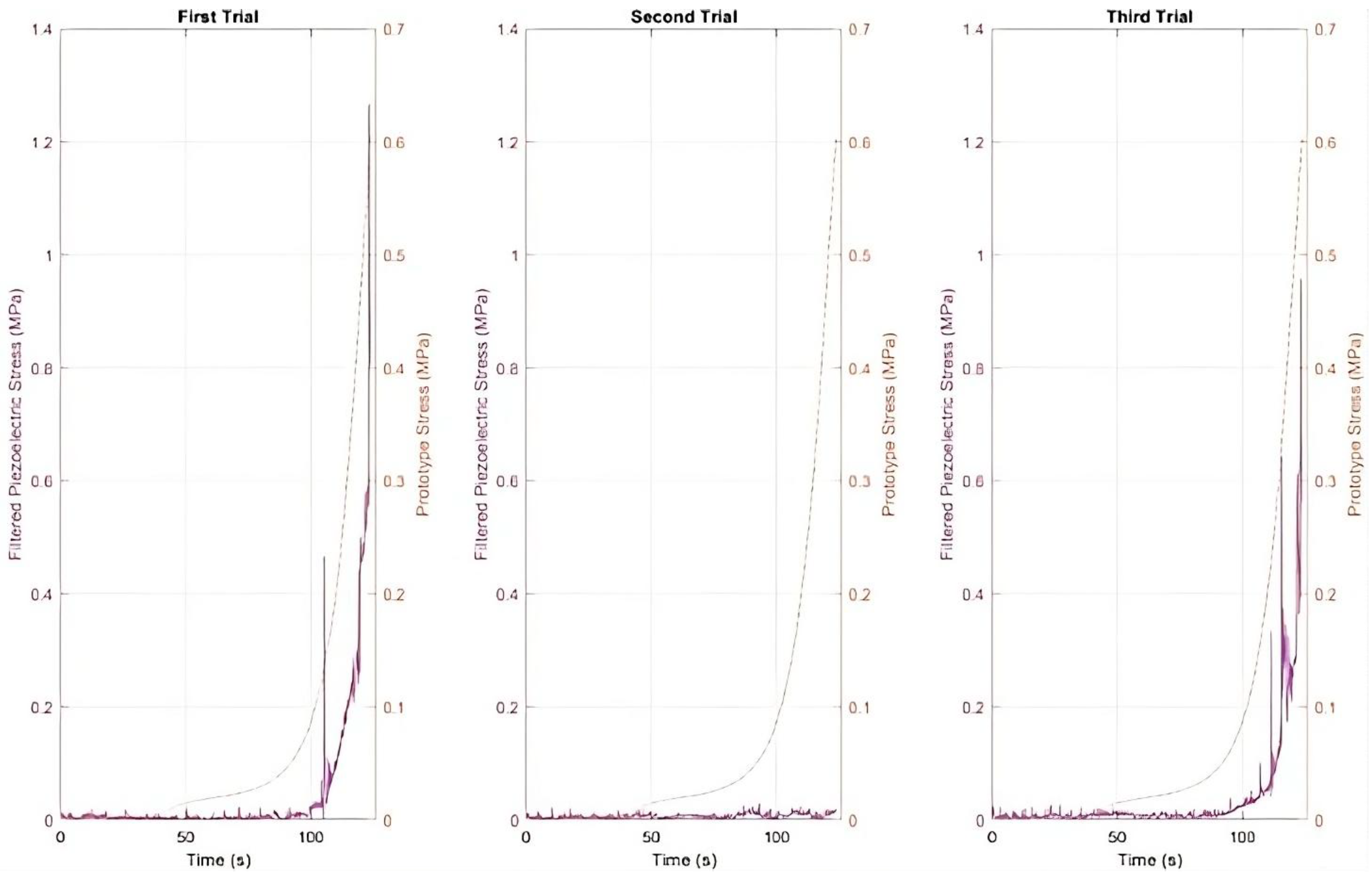

3.3.2. Piezoelectric Sensor-Substrate Correlation

Figure 9 presents the filtered voltage signal from the piezoelectric sensor (left

Y-axis) alongside the mechanical stress applied to the insole (right

Y-axis), both measured in MPa and plotted over time for three separate trials.

Mechanical stress increases progressively and steadily throughout each trial, while the piezoelectric signal exhibits sharp, well-defined peaks that appear abruptly and briefly. This pattern reflects the sensor’s sensitivity to sudden changes in load rather than to sustained force.

In the first trial, the peaks occur precisely when the mechanical stress reaches its maximum values, highlighting the responsiveness of the piezoelectric sensor to transient load variations. In the second trial, these peaks appear later despite similar stress levels. This delay may be attributed to minor variations in the interface between the piezoelectric sensor and the insole, such as differences in alignment, contact pressure distribution, or positioning, or to the rest period between trials affecting the sensor’s internal charge accumulation.

Across all trials, the piezoelectric sensor does not produce a continuous or saturated output like the FSR sensor but instead responds discreetly to dynamic load changes. This behavior confirms the piezoelectric sensor’s effectiveness for detecting impacts or sudden load fluctuations and indicates its unsuitability for measuring sustained loads or static deformation.

4. Conclusions

This study compared the performance of FSR and piezoelectric sensors integrated into commercially available insoles through controlled compression testing. This experiment also serves as a preliminary proof of concept and highlights the necessity for higher-range sensing elements to ensure reliable operation in real in-shoe scenarios under human body load.

FSR sensors demonstrated reliable static pressure detection and maintained stable output under sustained loading conditions, making them well-suited for postural stability assessment, standing balance evaluation, and diabetic foot pressure monitoring. However, they exhibited limited dynamic range with saturation occurring at approximately 20 N and showed progressive performance degradation under repeated loading cycles. These limitations necessitate careful consideration of expected loading magnitudes and establishment of sensor replacement intervals for long-term monitoring applications.

Piezoelectric sensors exhibited exceptional dynamic sensitivity, generating sharp, reproducible voltage peaks synchronized with transient loading events. Their high temporal resolution, robust repeatability across multiple loading cycles, and minimal performance degradation establish their suitability for dynamic gait analysis, temporal event detection, and activity classification. However, their fundamental inability to measure static loads constrains their application to dynamic monitoring scenarios where temporal event detection takes priority over sustained pressure quantification.

The complementary nature of these sensor technologies motivates development of hybrid system architectures that leverage both capabilities within a single platform. Such systems could employ piezoelectric sensors at high-impact regions for precise temporal event detection while positioning FSR sensors at other locations for sustained pressure monitoring. This integrated approach would enable extraction of comprehensive biomechanical parameters including both temporal gait metrics and spatial pressure distributions.

The experimental methodology employed in this study provides a reproducible framework for sensor validation that addresses gaps in existing literature, where characterization often relies on computational modelling or proprietary systems. Several practical considerations emerged that inform future development: production systems require soldered connections rather than temporary fastening methods to ensure signal integrity, durability assessment protocols must simulate realistic use conditions to establish maintenance intervals, and signal conditioning strategies should be implemented to enhance measurement accuracy in uncontrolled environments.

The next development phase involves implementing multi-sensor arrays with four sensors per insole positioned at biomechanically relevant locations to capture comprehensive plantar pressure distributions. These enhanced prototypes will undergo validation testing including both controlled mechanical compression and human subject trials during actual gait and standing activities to confirm that laboratory-characterized performances translate to real-world applications.

In conclusion, FSR and piezoelectric sensors exhibit complementary characteristics that position them for synergistic roles in rehabilitation monitoring. Rather than competing alternatives, optimal system design embraces both technologies within hybrid architectures that capture comprehensive biomechanical information. The methodological framework and technical insights presented here provide a foundation for developing next-generation smart insole systems that enhance clinical decision-making, enable personalized rehabilitation interventions, and ultimately improve patient outcomes by bridging the gap between laboratory research and clinical practice.