Wearable-Sensor-Based Physical Activity and Sleep in Children with Down Syndrome Aged 0–5 Years: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Synthesis Methods

2.7. Protocol and Registration

3. Results

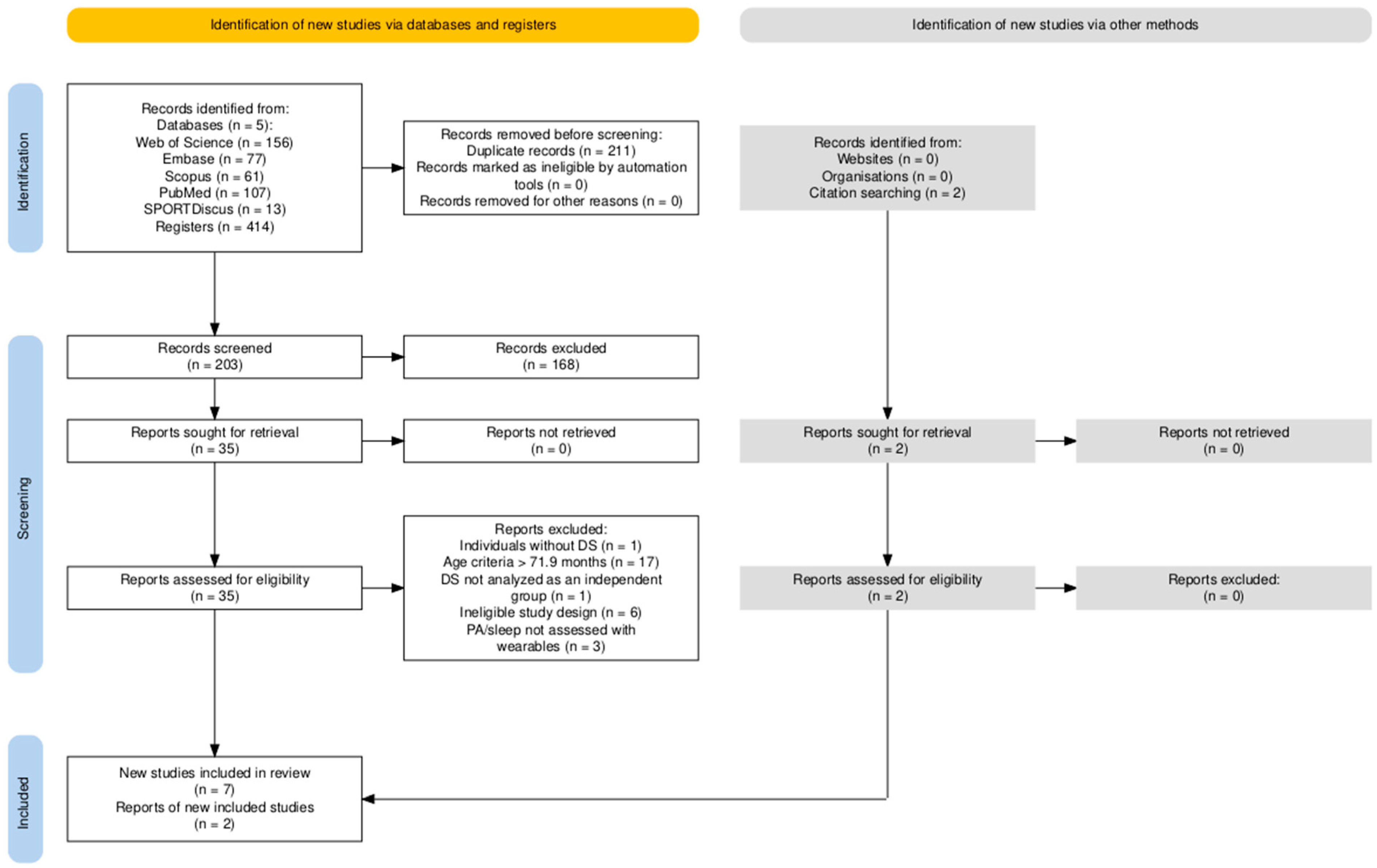

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.3.1. Country, Period, and Study Design

3.3.2. Participant Characteristics

3.4. Outcomes

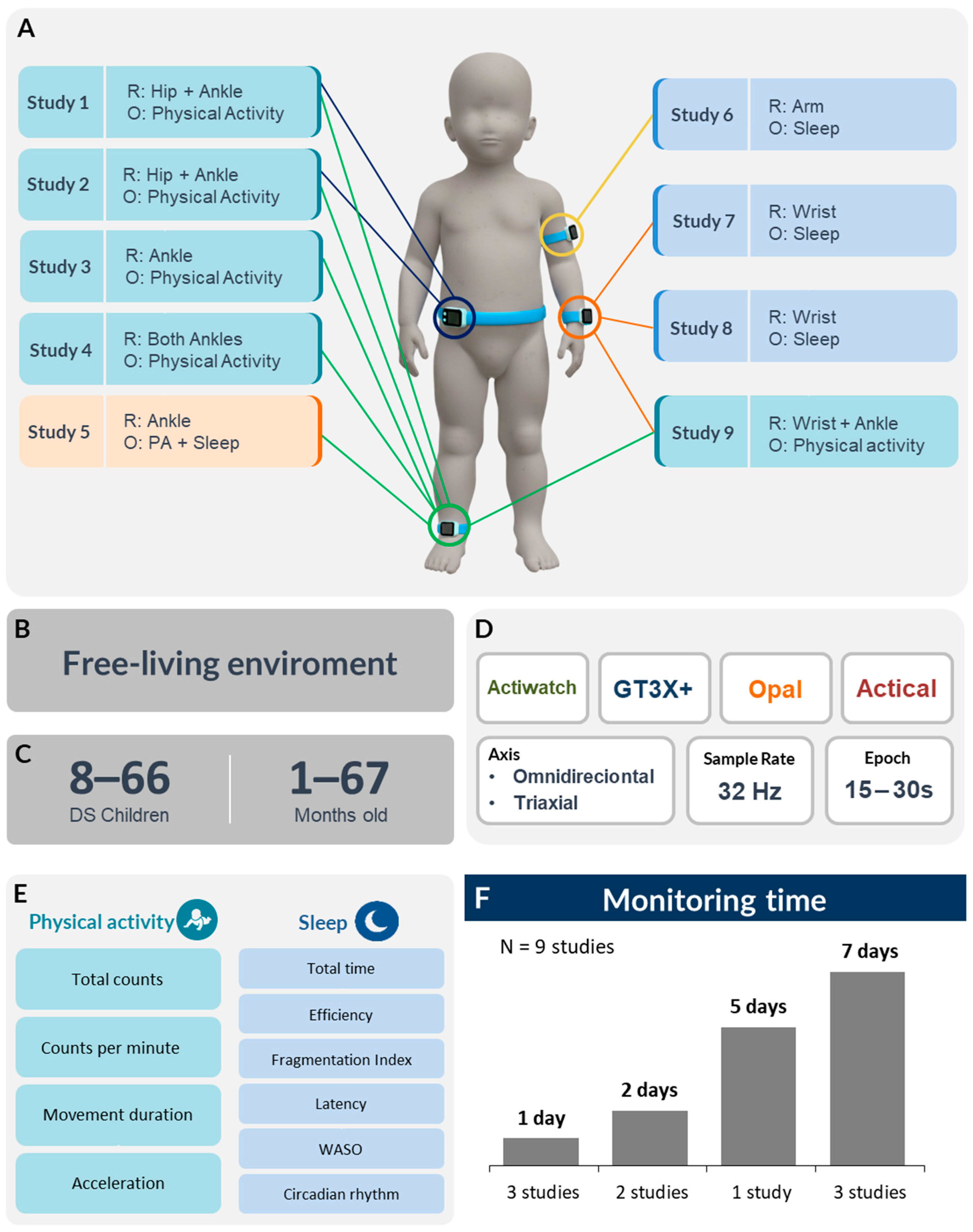

3.5. Measurement Protocols

3.5.1. PA and Sleep Sensor Configuration

3.5.2. Data Processing and Algorithms

Non-Wear Periods, Device Removal, and Missing Data

Software, Algorithm, and Classification Criteria

3.6. Summary of Findings

3.6.1. Physical Activity

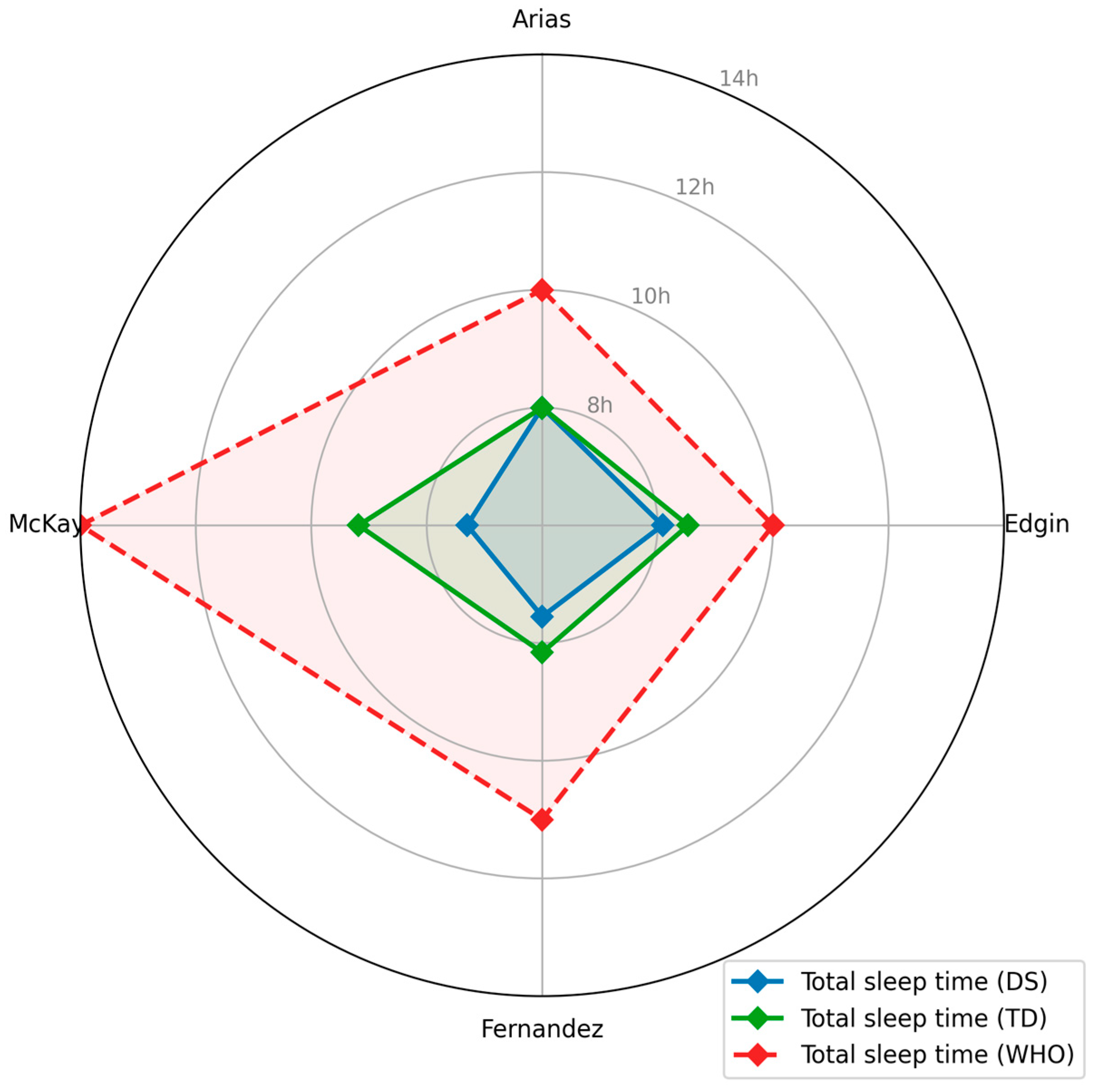

3.6.2. Sleep

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Activity and Sleep Findings

4.2. PA and Sleep Sensor Settings

4.3. Quality of Research

4.4. Limitations of the Evidence

4.5. Limitations of the Review

4.6. Implications for Research

4.7. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPM | Counts per minute |

| DS | Down syndrome |

| FAPESP | Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo |

| GS | Good sleep |

| HI | Higher intensity (treadmill intervention) |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| LG | Lower intensity (treadmill intervention) |

| LMIC | Low- and middle-income countries |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| NA | Not applicable |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International prospective register of systematic reviews |

| PS | Poor sleep |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trial |

| SB | Sedentary behavior |

| TD | Typical development (children) |

| UNIFESP | Universidade Federal de São Paulo |

| USA | United States of America |

| WASO | Wake after sleep onset |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Lampl, M.; Johnson, M.L. Infant growth in length follows prolonged sleep and increased naps. Sleep 2011, 34, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.Y.; Hewitt, L.; Jennings, C.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Stearns, J.A.; Unrau, S.P.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between physical activity and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Carson, V.; Gruber, R.; Birken, C.S.; MacLean, J.E.; Aubert, S.; Sampson, M.; Tremblay, M.S. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzer-Kim, I.T.; Hauck, J.L. Sleep duration associates with moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity and body fat in 1- to 3-year-old children. Infant Behav. Dev. 2020, 58, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pate, R.R.; Hillman, C.; Janz, K.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Torres, A.; Whitt-Glover, M.C. Physical activity and health in children under 6 years of age: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; 83p. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, J.R.; Xu, S.; Rogers, J.A. From lab to life: How wearable devices can improve health equity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Badea, M.; Tiwari, S.; Marty, J.L. Wearable biosensors: An alternative and practical approach in healthcare and disease monitoring. Molecules 2021, 26, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, H.; Li, T.; Jin, Q.; Cui, D. Recent developments in sensors for wearable device applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 6037–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, H.C.; Nguyen, P.Q.; Gonzalez-Macia, L.; Morales-Narváez, E.; Güder, F.; Collins, J.J.; Dincer, C. End-to-end design of wearable sensors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G. Measurement of physical activity in children and adolescents. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2007, 1, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, A. The role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: An update. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, S.F.; Kurth, S.; Werner, H. Actigraphy in sleep research with infants and young children: Current practices and future benefits of standardized reporting. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettink, A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Arts, J.; van Hees, V.T.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Systematic review of accelerometer-based methods for 24-h physical behavior assessment in young children (0–5 years old). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. A review of wearable sensor systems for monitoring body movements of neonates. Sensors 2016, 16, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Blake, H.; Crozier, A.J.; Dankiw, K.; Dumuid, D.; Kasai, D.; O’Connor, E.; Virgara, R.; et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e615–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rast, F.M.; Labruyère, R. Systematic review on the application of wearable inertial sensors to quantify everyday life motor activity in people with mobility impairments. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2020, 17, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumpouros, Y.; Kafazis, T. Wearables and mobile technologies in autism spectrum disorder interventions: A systematic literature review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 66, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migueles, J.H.; Aadland, E.; Andersen, L.B.; Brønd, J.C.; Chastin, S.F.; Hansen, B.H.; Konstabel, K.; Kvalheim, O.M.; McGregor, D.E.; Rowlands, A.V.; et al. GRANADA consensus on analytical approaches to assess associations with accelerometer-determined physical behaviours (physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep) in epidemiological studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, M.W.; Baumert, M.; Scott, H.; Cellini, N.; Goldstein, C.; Baron, K.; Imtiaz, S.A.; Penzel, T.; Kushida, C.A. World Sleep Society recommendations for the use of wearable consumer health trackers that monitor sleep. Sleep Med. 2025, 131, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonarakis, S.; Skotko, B.; Rafii, M.; Strydom, A.; Pape, S.; Bianchi, D.; Sherman, S.; Reeves, R. Down syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, S.M.; Riegel, M.; Segal, S.L.; Félix, T.M.; Barros, A.J.D.; Santos, I.S.; Matijasevich, A.; Giugliani, R.; Black, M. Genetic causes of intellectual disability in a birth cohort: A population-based study. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, G.; Engelen, J.J.M.; Gijsbers, A.C.J.; Hochstenbach, R.; Hoffer, M.J.V.; Kooper, A.J.A.; Sikkema-Raddatz, B.; Srebniak, M.I.; van der Kevie-Kersemaekers, A.M.F.; van Zutven, L.J.C.M.; et al. Estimates of live birth prevalence of children with Down syndrome in the period 1991–2015 in the Netherlands. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2017, 61, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, G.; Buckley, F.; Skotko, B.G. Estimation of the number of people with Down syndrome in the United States. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Trotter, T.; Santoro, S.L.; Christensen, C.; Grout, R.W.; Committee on Genetics. Health supervision for children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2022057010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.K.; Clarke, S.; Gelb, B.D.; Kasparian, N.A.; Kazazian, V.; Pieciak, K.; Pike, N.A.; Setty, S.P.; Uveges, M.K.; Rudd, N.A. Trisomy 21 and congenital heart disease: Impact on health and functional outcomes from birth through adolescence: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e036214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiovlasitis, S.; Choi, P.; Allred, A.T.; Xu, J.; Motl, R.W. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour in people with Down syndrome across the lifespan: A clarion call. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2020, 33, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamo, E.K.; Wu, J.; Wolery, M.; Hemmeter, M.L.; Ledford, J.R.; Barton, E.E. Using video modeling, prompting, and behavior-specific praise to increase moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for young children with Down syndrome. J. Early Interv. 2015, 37, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.; Moffett, G.E.; Kinnison, C.; Brooks, G.; Case, L.E. Physical activity levels of children with Down syndrome. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 31, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, S.M.; Angulo-Barroso, R.M. Longitudinal assessment of leg motor activity and sleep patterns in infants with and without Down syndrome. Infant Behav. Dev. 2006, 29, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, O.; Yassikaya, M.Y. Validity and reliability analysis of the PlotDigitizer software program for data extraction from single-case graphs. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2022, 45, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer, version 5.2; Automeris: Pacifica, CA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://automeris.io (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Edgin, J.O.; Tooley, U.; Demara, B.; Nyhuis, C.; Anand, P.; Spanò, G. Sleep disturbance and expressive language development in preschool-age children with Down syndrome. Child Dev. 2015, 86, 1984–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Nyhuis, C.C.; Anand, P.; Demara, B.I.; Ruby, N.F.; Spanò, G.; Clark, C.; Edgin, J.O. Young children with Down syndrome show normal development of circadian rhythms, but poor sleep efficiency: A cross-sectional study across the first 60 months of life. Sleep Med. 2017, 33, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Trejo, N.; Angulo-Chavira, A.Q.; Demara, B.; Figueroa, C.; Edgin, J. The influence of sleep on language production modalities in preschool children with Down syndrome. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 30, e13120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketcheson, L.; Pitchford, E.A.; Kwon, H.J.; Ulrich, D.A. Physical activity patterns in infants with and without Down syndrome. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2017, 29, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.; Burghardt, A.; Ulrich, D.A.; Angulo-Barroso, R. Physical activity and walking onset in infants with Down syndrome. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2010, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khasgiwale, R.N.; Smith, B.A.; Looper, J. Leg movement rate pre- and post-kicking intervention in infants with Down syndrome. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2021, 41, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauck, J.L.; Felzer-Kim, I.T.; Gwizdala, K.L. Early movement matters: Interplay of physical activity and motor skill development in infants with Down syndrome. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2020, 37, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Barroso, R.; Burghardt, A.R.; Lloyd, M.; Ulrich, D.A. Physical activity in infants with Down syndrome receiving a treadmill intervention. Infant Behav. Dev. 2008, 31, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heubi, C.H.; Knollman, P.; Wiley, S.; Shott, S.R.; Smith, D.F.; Ishman, S.L.; Meinzen-Derr, J. Sleep architecture in children with Down syndrome with and without obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 164, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstad, T.K.; DelRosso, L.M.; Tablizo, M.A.; Witmans, M.; Cho, Y.; Sobremonte-King, M. Sleep-disordered breathing and associated comorbidities among preschool-aged children with Down syndrome. Children 2024, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, L.J.; Montgomery-Downs, H.E.; Insana, S.P.; Walsh, C.M. Use of actigraphy for assessment in pediatric sleep research. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K.A.; McIver, K.L.; Dowda, M.; Almeida, M.J.C.A.; Pate, R.R. Validation and calibration of the Actical accelerometer in preschool children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo, L.I.C.; da Silva, I.C.M.; Martins, R.C.; Wendt, A.; Gonçalves, H.; Hallal, P.R.C.; Wehrmeister, F.C. Protocol for objective measurement of infants’ physical activity using accelerometry. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 1084–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migueles, J.H.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Ekelund, U.; Delisle Nyström, C.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Löf, M.; Labayen, I.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B. Accelerometer data collection and processing criteria to assess physical activity and other outcomes: A systematic review and practical considerations. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1821–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertapelli, F.; Curtis, J.S.; Carlson, B.; Johnson, M.; Abadie, B.; Agiovlasitis, S. Step-counting accuracy of activity monitors in persons with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertapelli, F.; Allred, A.T.; Choi, P.; Pitchford, E.A.; Guerra-Junior, G.; Agiovlasitis, S. Predicting the rate of oxygen uptake from step counts using ActiGraph waist-worn accelerometers in adults with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch, S.F.; Jenni, O.G.; Kohler, M.; Kurth, S. Actimetry in infant sleep research: An approach to facilitate comparability. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.T.; McCrae, C.S.; Cheung, J.; Martin, J.L.; Harrod, C.G.; Heald, J.L.; Carden, K.A. Use of actigraphy for the evaluation of sleep disorders and circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hybschmann, J.; Topperzer, M.K.; Gjærde, L.K.; Born, P.; Mathiasen, R.; Sehested, A.M.; Jennum, P.J.; Sørensen, J.L. Sleep in hospitalized children and adolescents: A scoping review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 59, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papavassiliou, P.; Charalsawadi, C.; Rafferty, K.; Jackson-Cook, C. Mosaicism for trisomy 21: A review. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2015, 167A, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Barros, F.C. Cohorts in low- and middle-income countries: From still photographs to full-length movies. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 51, S3–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2012: Children in an Urban World; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Keywords Concept | Keywords Domain | Keywords Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Population descriptors | Down syndrome | “Down syndrome” OR “Downs syndrome” OR “trisomy 21” |

| AND | ||

| Age group | Infan * OR child * OR toddler* OR newborn * OR neonate * OR baby OR babies | |

| AND | ||

| Constructs of physical activity and sleep | Physical activity and sleep | “physical activit *” OR “physical exercise” OR fitness OR “motor skill” OR “energy expenditure” OR “motor development” OR “fundamental movement skill” OR “metabolic equivalent of task” OR “sedentary behavior” OR “sedentary time” OR sleep OR nap OR naps |

| AND | ||

| Assessment of physical activity and sleep | Wearable devices | “wearable sensor *” OR “wearable device *” OR “electronic device *” OR acceleromet * OR “physical activity monitor *” OR “activity tracker” OR actigraph * |

| 1º Author, Year | Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Item 12 | Item 13 | Weight % | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies a | |||||||||||||||

| Arias-Trejo, 2020 [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | Low |

| Edgin, 2015 [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | Low |

| Fernandez, 2017 [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | Low |

| Ketcheson, 2017 [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | Low |

| Cohort studies b | |||||||||||||||

| Hauck, 2020 [43] | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | - | - | 54.55 | Moderate |

| Lloyd, 2010 [41] | NA | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | - | - | 100 | Low |

| McKay, 2006 [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | - | - | 81.82 | Low |

| Quasi-experimental studies c | |||||||||||||||

| Khasgiwale, 2021 [42] | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | 87.5 | Low |

| Randomized clinical trial d | |||||||||||||||

| Angulo-Barroso, 2008 [44] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 61.54 | Moderate |

| 1º Author, Year | Sample Size, DS | Age in Months Mean (SD) | Ethnicity/Race n (%) | Exclusion Criteria | TD Comparison Group | Study Design | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angulo-Barroso, 2008 [44] | 30 | 21.8 (3.1) and 24.9 (5.1) Age range: NA | African American: 2 (6.7%), Caucasian: 26 (86.7%), Other: 2 (6.6%) | NA | No | RCT | USA |

| Arias-Trejo, 2020 [39] | 18 | 50.2 (5.2) Age range: 24–60 | NA | Neurological or psychiatric comorbidities; medications; <5 days actigraphy sleep recording | Yes | Cross-sectional | NA |

| Edgin, 2015 [37] | 29 | 42 (10.3) Age range: 27–64 | NA | Diagnosis of DS (including mosaicism or translocation); gestational age < 36 weeks; history of cyanotic heart defects; primary household language other than English | Yes | Cross-sectional | USA |

| Fernandez, 2017 [38] | 66 | 29.86 (15.92) Age range: 5–67 | NA | Gestational age < 36 weeks; <5 full consecutive days of actigraphy; child sick during recording period | Yes | Cross-sectional | USA |

| Hauck, 2020 [43] | 9 | Age range: 1–12 | European American: 7 (77.8%), African American: 1 (11.1%), Hispanic/Latino: 1 (11.1%) | NA | Yes | Longitudinal | USA |

| Ketcheson, 2017 [40] | 11 | 7.50 (3.14) Age range: 1–12 | Caucasian: 9 (81.8%), Other: 2 (18.2%) | NA | Yes | Cross-sectional | USA |

| Khasgiwale, 2021 [42] | 9 | 4.3 (0.7) Age range: 2–5 | NA | Neuromuscular or neurodevelopmental diagnoses | Yes | Quasi-experimental | USA |

| Lloyd, 2010 [41] | 30 | 10.7 (1.9) | Caucasian: 26 (86.7%), African American: 2 (6.7%), Other: 2 (6.6%) | Seizure disorder; noncorrectable vision problems; other medical conditions | NA | Longitudinal | USA |

| McKay, 2006 [30] | 8 | 3.3 (0.3) | NA | NA | Yes | Longitudinal | USA |

| Actiwatch 2 1 | Respironics Actical 2 | GT3X+ 3 | Opals 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | 43 × 23 × 10 mm | 29 × 37 × 11 mm | 33 × 46 × 15 mm | 48.5 × 36.5 × 13.5 mm |

| Weight | 16 g | 16 g (without band) 22 g (with standard band) | 19 g | 22 g |

| Case material | ABS blend | Polyurethane/Polyester alloy | - | 6061 clear anodized aluminum, ABS plastic |

| Memory size | 1 Mbit | 32 MB | - | 8 GB |

| Accelerometer | Solid State Piezoelectric accelerometer. Bandwidth: 0.35–7.5 Hz. Range: 0.5–2 G peak value. Sampling rate: 32 Hz. | Range: 0.05 G to 2 G. Bandwidth: 0.035 Hz to 3.5 Hz. Sampling rate: 32 Hz. | Microelectromechanical system (MEMS)-based accelerometer and an ambient light sensor. 3-axis. Sampling rate: 30 Hz to 100 Hz. | 3-axis, range: ±2 g or ±6 g. Bandwidth: 50 Hz, resolution: 14 bits. Sampling rate: 1280 Hz. |

| Gyroscope | Not present | Not present | Not present | 3-axis. Range ±2000 º/s. Bandwidth: 50 Hz; resolution: 14 bits. Sampling rate: 1280 Hz. |

| Magnetometer | Not present | Not present | Not present | 3-axis. Range ±6 Gauss. Bandwidth: 50 Hz; resolution: 14 bits. Sampling rate: 1280 Hz. |

| Logging interval | 1, 15, 30 s | 1, 2, 5, 15, 30, 60 s | 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120, 150, 180, 240 s | - |

| Sensitivity | 0.025 G (at 2-count level) | 0.02 G (at 1 G peak) | 3 mg/LSB | - |

| 1º Author, Year | Analysis Software | Algorithm | Parameter/ Sensitivity/ Threshold | Sleep–Wake or Activity Classification Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angulo-Barroso, 2008 [44] | Mini Mitter/ Respironics software | NR | Low sensitivity (80). Threshold: 50 movement units | Sleep–wake identified within day/night blocks. Start of activity = identified when five consecutive non-zero data points were detected (corresponding to five 15 s epochs). |

| Arias-Trejo, 2020 [39] | Actiware 6.0 | NR | Threshold: 40 counts/min for ≥5 min | Sleep periods were computed in the software and manually corrected using the sleep log. |

| Edgin, 2015 [37] | Actiware 5.71.0 | NR | Threshold: 40 counts/min | Sleep onset = ≥3 min immobility; sleep end = ≥5 min immobility. |

| Fernandez, 2017 [38] | ClockLab (Actimetrics v6, Wilmette, IL, USA). | Template matching algorithm | Threshold: 40 counts/epoch | Daily onsets; daily offsets; daily acrophases. |

| Hauck, 2020 [43] | - | NA | - | Mean activity counts per minute over 24 h wear period. |

| Ketcheson, 2017 [40] | ActiLife 6 | NA | NA | PA data are expressed in average counts per minute; no intensity categories defined. |

| Khasgiwale, 2021 [42] | Custom MATLAB analysis | NR | NR | Infant considered asleep if <3 leg movements across 5 min. |

| Lloyd, 2010 [41] | Mini Mitter/ Respironics software | NR | Average threshold: 131 movement units per 15 s (leg data) | Activity classified as sedentary–light (low-act) vs. moderate–vigorous (high-act), and sleep or wake state. |

| McKay, 2006 [30] | Mini Mitter/ Respironics software | NR | Low sensitivity (80) | Sleep and wake periods identified within day/night blocks. |

| 1º Author, Year | Device Make/Model | Epoch | Sensor’s Units | Attachment Site | Duration | PA Findings | Sleep Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angulo-Barroso, 2008 [44] | Phillips Respironics/ Actiwatch | 15 s | 2 | Hip/Ankle | 24 h | Mean counts (min), leg low act: 337.85 HI; 396.00 LG Mean counts (min), leg high act: 304.62 HI; 307.38 LG Mean counts (min), trunk low act: 268.96 HI; 304.19 LG Mean counts (min), trunk high act: 299.50 HI; 278.36 LG | NA |

| Arias-Trejo, 2020 [39] | Phillips Respironics/ Actiwatch 2 | 15 s | 1 | Arm | 7 days | NA | Sleep efficiency (median [%]): DS: 82; TD: 89; p < 0.001 Sleep time (hours): DS: 8; TD: 8; p = 0.06 Sleep onset latency (minutes): DS: 7; TD: 6; p = 0.62 Fragmentation index (%): DS: 69; TD; 59; p = 0.04 WASO: DS: 82; TD: 52; p < 0.001 |

| Edgin, 2015 [37] | Phillips Respironics/ Actiwatch 2 | 30 s | 1 | Wrist | 5 days | NA | Sleep efficiency (mean [%]): DS PS: 74.35; DS GS: 83.66 TD: 85.09; p < 0.001 Average sleep time (minutes): DS PS: 460.50; DS GS: 509.75; TD: 511.73; p < 0.01 WASO (minutes) DS PS: 122.60; DS GS: 78.32; TD: 68.39; p < 0.001 Onset latency (minutes): DS PS: 9.88; DS GS: 10.48; TD: 13.44; p = 0.44 Fragmentation index (%): DS PS: 35.29; DS GS: 25.54; TD 25.50; p = 0.001 |

| Fernandez, 2017 [38] | Phillips Respironics/ Actiwatch 2 | 30 s | 1 | Wrist/Ankle | 7 days | NA | Sleep efficiency (average [%]): DS: 75.86; TD: 82.90 Total sleep time (minutes): DS: 453.07; TD: 489.66 Onset phase (hours): DS: 6.96; TD: 6.91 Offset phase (hours): DS: 20.87; TD: 20.86 Acrophase(hours): DS: 13.87; TD: 13.93 |

| McKay, 2006 [30] | Phillips Respironics/ Actiwatch | 15 s | 1 | Ankle | 48 h | Integral of total activity (counts·day): 3 mo—DS: 221,733; TD: 186,932 4 mo—DS: 226,705; TD: 189,915 5 mo—DS: 207,813; TD: 232,670 6 mo—DS: 265,483; TD: 193,892 Low-Intensity activity (h·day): 3 mo—DS: 6.32; TD: 4.59 4 mo—DS: 5.93; TD: 4.99 6 mo—DS: 5.67; TD: 4.56 Time in low-intensity activity, night (min): 6 mo—DS: 76.43; TD: 35.27; p < 0.0125 Time in low-intensity activity integral (counts·day−1): 3 mo—DS: 14 975.41; TD: 10 480.61; p < 0.0125 | Total sleep time (hours): DS: 7.30 h; TD: 9.18 h Length of night (hours): DS: 8.53 h; TD: 10.41 h Length of day (hours): DS: 15.8 h; TD: 13.51 h; p < 0.0125 |

| Hauck, 2020 [43] | Phillips Respironics/ Actical | 15 s | 1 | Ankle | 24 h | CPM (counts·min): 1 mo—DS: 49.16; TD: 61.99 2 mo—DS: 56.80; TD: 85.89 3 mo—DS: 79.01; TD: 96.34 4 mo—DS: 75.29; TD: 95.79 5 mo—DS: 76.30; TD: 112.34 6 mo—DS: 55.19; TD: 122.23 12 mo—DS: 103.55; TD: 195.81 18 mo—DS: 131.48; TD: 264.54 | NA |

| Ketcheson, 2017 [40] | Actigraph/ GT3X+ | 15 s | 2 | Wrist/Ankle | 7 days | CPM (counts·min−1): Ankle: 1–2 mo—DS: 201.38; TD: 188.68 3–4 mo—DS: 248.28; TD: 322.01 5–6 mo—DS: 435.86; TD: 319.50 7–8 mo—DS: 433.10; TD: 397.48 9–10 mo—DS: 361.38; TD: 472.96 11–12 mo—DS: 433.10; TD: 460.38 Wrist: 1–2 mo—DS: 406.69; TD: 353.89 3–4 mo—DS: 409.36; TD: 456.07 5–6 mo—DS: 535.11; TD: 396.26 7–8 mo—DS: 481.60; TD: 633.02 9–10 mo—DS: 599.33; TD: 677.88 11–12 mo—DS: 470.90; TD: 705.30 Overall means (1–12 mo): Ankle: DS: 332.98; TD: 367.59; p = 0.296 Wrist: DS: 469.75; TD: 541.03; p = 0.171 | NA |

| Khasgiwale, 2021 [42] | Opals, APDM/Opal | NA | 2 | Ankle | 2 days | Post-intervention: Average leg movement rate (mov·h1) DS: 2350.7; TD: 3343.9; p = 0.002 Average leg acceleration (m·s2) DS: 2.09; TD: 2.34; p = 0.96 Peak leg acceleration (m·s2) DS: 4.55; TD: 4.53; p = 0.25 Mean movement duration (s) DS: 0.27; TD: 0.26; p = 0.34 | NA |

| Lloyd, 2010 [41] | Phillips Respironics/ Actiwatch | 15 s | 2 | Hip/Ankle | 24 h | Movement/units (mean) Leg high act: 10 mo: 45,382; 12 mo: 49,446; 14 mo: 50,123 Leg low act: 10 mo: 21,810; 12 mo: 20,591; 14 mo: 23,030 Trunk high act: 10 mo: 10,296; 12 mo: 13,953; 14 mo: 16,392 Trunk low act: 10 m: 8805; 12 m: 8941; 14 m: 9212 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borges, G.; Moreira, V.; Bertapelli, F. Wearable-Sensor-Based Physical Activity and Sleep in Children with Down Syndrome Aged 0–5 Years: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237278

Borges G, Moreira V, Bertapelli F. Wearable-Sensor-Based Physical Activity and Sleep in Children with Down Syndrome Aged 0–5 Years: A Systematic Review. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237278

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorges, Gilson, Vanessa Moreira, and Fabio Bertapelli. 2025. "Wearable-Sensor-Based Physical Activity and Sleep in Children with Down Syndrome Aged 0–5 Years: A Systematic Review" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237278

APA StyleBorges, G., Moreira, V., & Bertapelli, F. (2025). Wearable-Sensor-Based Physical Activity and Sleep in Children with Down Syndrome Aged 0–5 Years: A Systematic Review. Sensors, 25(23), 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237278