Investigation of Surface Modification Effects on the Optical and Electrical Hydrogen Sensing Characteristics of WO3 Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

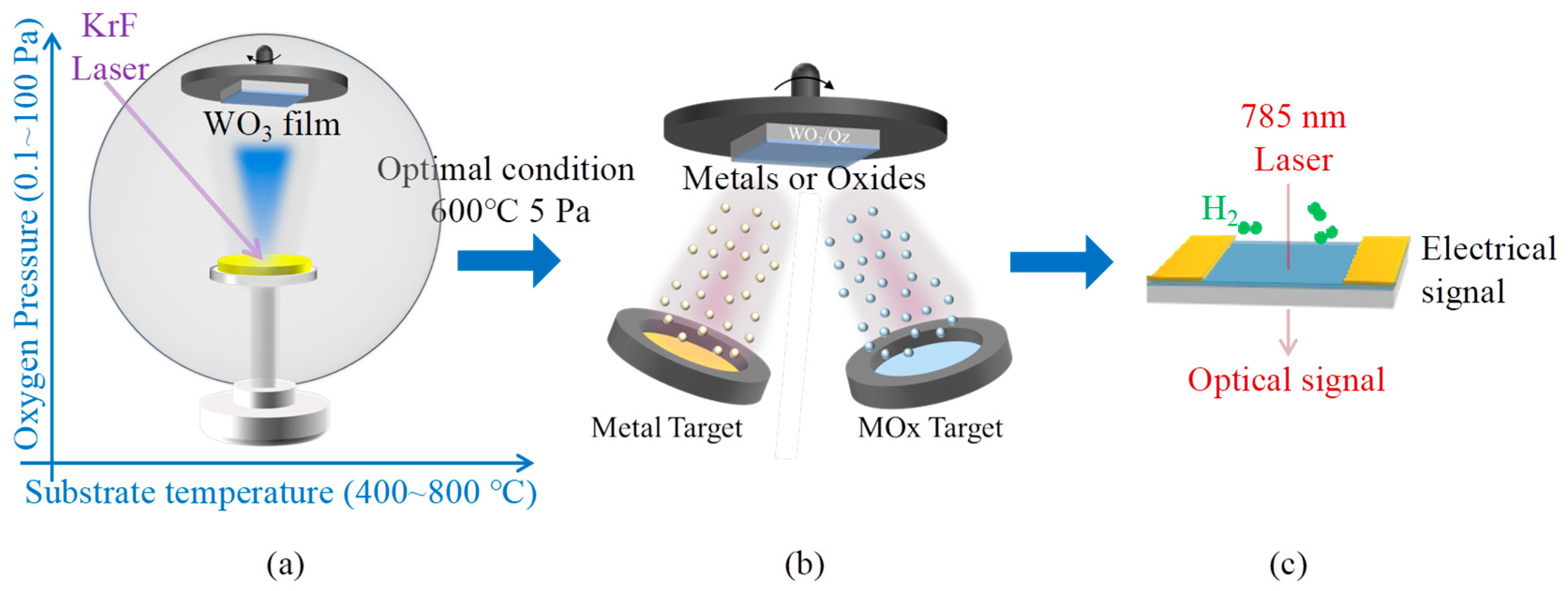

2.1. Fabrication of WO3 Thin Films

2.2. Synthesis of Materials for Surface Modification

2.3. Structure Characterizations

2.4. Evaluation of Hydrogen Sensing Characteristics

3. Results and Discussion

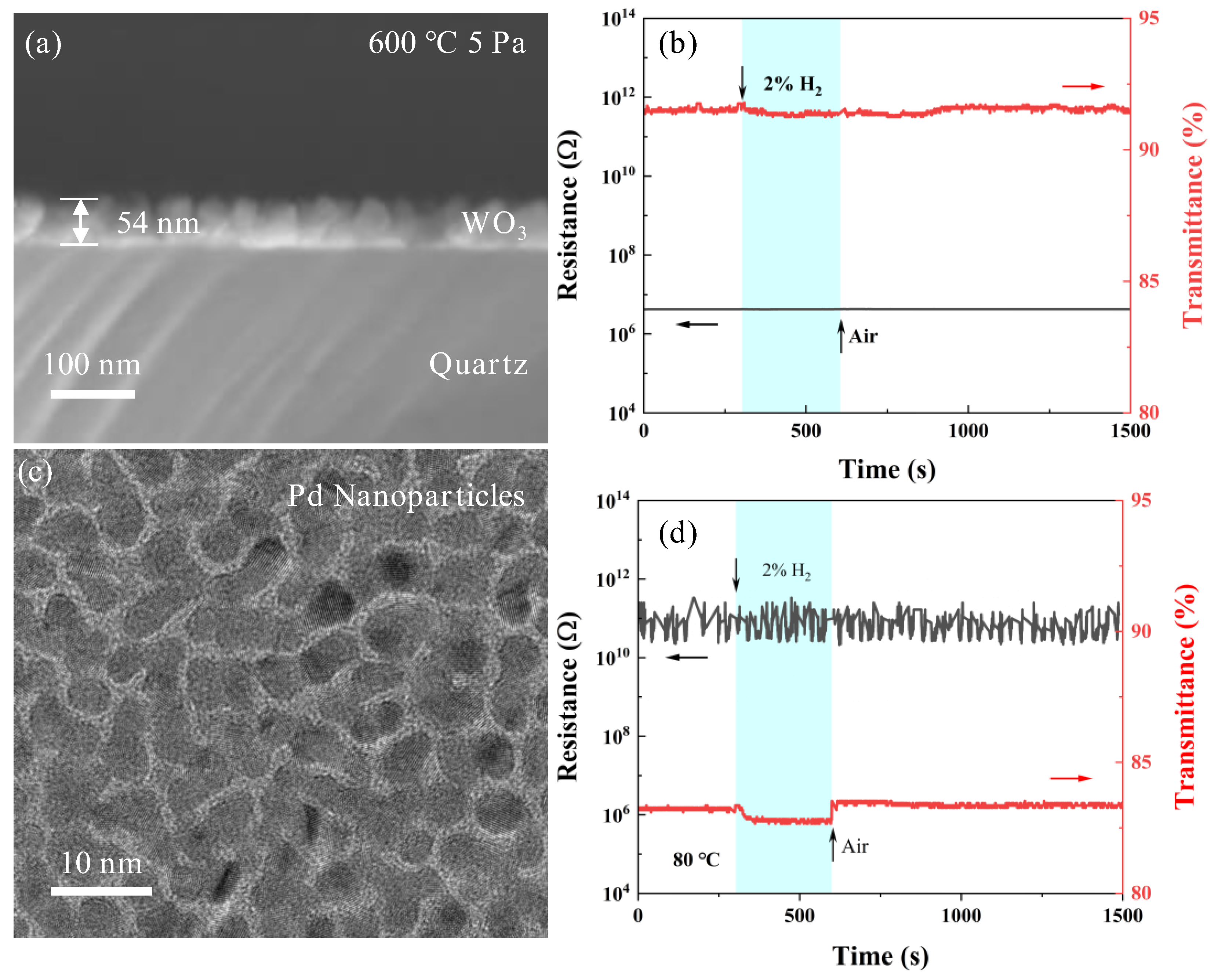

3.1. Structure of WO3 Films

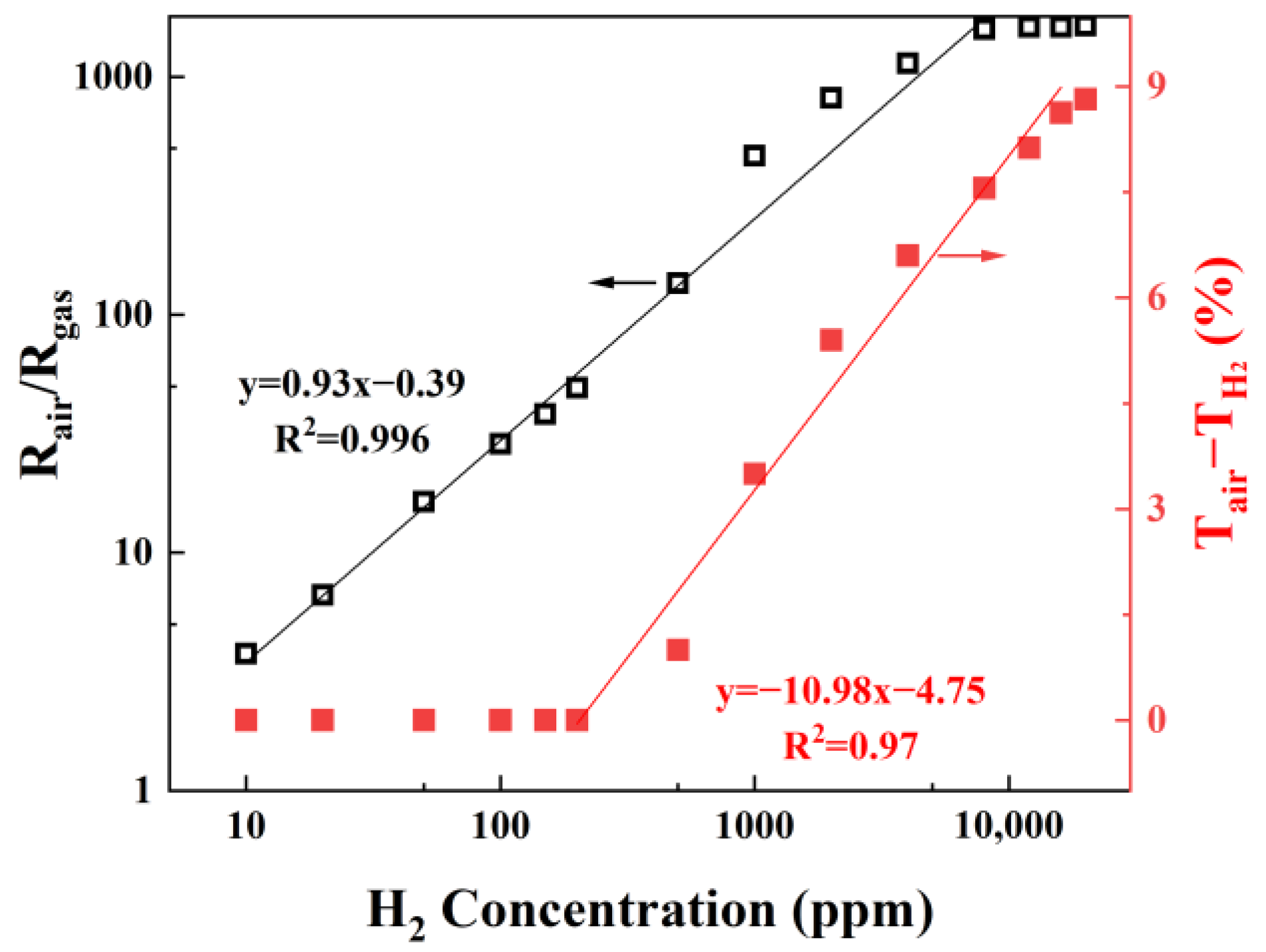

3.2. Metal-Functionalized Samples

3.3. MOx-Functionalized Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hossain Bhuiyan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel: A comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, A.J.; Monteiro, M.C.O.; Dattila, F.; Pavesi, D.; Philips, M.; da Silva, A.H.M.; Vos, R.E.; Ojha, K.; Park, S.; van der Heijden, O.; et al. Water electrolysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.A.; Abdulrahman, G.A.Q. A Recent Comprehensive Review of Fuel Cells: History, Types, and Applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 7271748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon-Brett, L.; Bousek, J.; Black, G.; Moretto, P.; Castello, P.; Hubert, T.; Banach, U. Identifying performance gaps in hydrogen safety sensor technology for automotive and stationary applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndaya, C.C.; Javahiraly, N.; Brioude, A. Recent Advances in Palladium Nanoparticles-Based Hydrogen Sensors for Leak Detection. Sensors 2019, 19, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, E.; Ehrmann, A.; Schwenzfeier-Hellkamp, E. Safety of Hydrogen Storage Technologies. Processes 2024, 12, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukawa, T.; Ishigaki, T. Effect of isothermal holding time on hydrogen-induced structural transitions of WO3. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 7590–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. Gasochromic WO3 Nanostructures for the Detection of Hydrogen Gas: An Overview. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Maeng, B.; Yang, Y.; Kim, K.; Jung, D. Hybrid Hydrogen Sensor Based on Pd/WO3 Showing Simultaneous Chemiresistive and Gasochromic Response. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Lin, X.; Xue, D.; Zong, F.; Zhang, J.; Duan, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, T. Enhanced H2 gas sensing properties by Pd-loaded urchin-like W18O49 hierarchical nanostructures. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 260, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S. Highly Sensitive and Selective CO/NO/H2/NO2 Gas Sensors Using Noble Metal (Pt, Pd) Decorated MOx (M = Sn, W) Combined with SiO2 Membrane. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 10674–10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, B.; Zhou, R.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, T. Room-temperature H2 sensing interfered by CO based on interfacial effects in palladium-tungsten oxide nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 254, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanur, S.S.; Yoo, I.-H.; Lee, Y.-A.; Seo, H. Green deposition of Pd nanoparticles on WO3 for optical, electronic and gasochromic hydrogen sensing applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 221, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-C.; Hsu, W.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-S. Hydrogen incorporation in gasochromic coloration of sol-gel WO3 thin films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 157, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.-C.; Chan, C.-C.; Peng, C.-H.; Chang, C.-C. Hydrogen sensing characteristics of an electrodeposited WO3 thin film gasochromic sensor activated by Pt catalyst. Thin Solid Film. 2007, 516, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Okazaki, S.; Nishijima, Y.; Arakawa, T. Optimization of Hydrogen Sensing Performance of Pt/WO3 Gasochromic Film Fabricated by Sol-Gel Method. Sens. Mater. 2017, 29, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Li, D.; Zong, Q.; Gao, G.; Wu, G.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Z. Tandem gasochromic-Pd-WO3/graphene/Si device for room-emperature high-performance optoelectronic hydrogen sensors. Carbon 2018, 130, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensling, F.V.E.; Braun, W.; Kim, D.Y.; Majer, L.N.; Smink, S.; Faeth, B.D.; Mannhart, J. State of the art, trends, and opportunities for oxide epitaxy. APL Mater. 2024, 12, 040902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, Y.; Enomonoto, K.; Okazaki, S.; Arakawa, T.; Balčytis, A.; Juodkazis, S. Pulsed laser deposition of Pt-WO3 of hydrogen sensors under atmospheric conditions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 534, 147568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Han, S.-I.; Duy, L.T.; Yeasmin, R.; Jung, G.; Jeon, D.W.; Kim, W.; Cho, S.B.; Seo, H. Gasochromic WO3/MoO3 sensors prepared by co-sputtering for hydrogen leak detection with long-lasting visible signal. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 426, 137030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, M.; Kapuścik, P.; Weichbrodt, W.; Domaradzki, J.; Mazur, P.; Kot, M.; Flege, J.I. WO3 Thin-Film Optical Gas Sensors Based on Gasochromic Effect towards Low Hydrogen Concentrations. Materials 2023, 16, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Suh, J.M.; Jeong, B.; Lee, T.H.; Choi, K.S.; Eom, T.H.; Choi, S.W.; Nam, G.B.; Kim, Y.J.; Jang, H.W. Substantially Accelerated Response and Recovery in Pd-Decorated WO3 Nanorods Gasochromic Hydrogen Sensor. Small 2024, 20, e2309744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.C.; Cha, H.-Y.; Kim, H. High Selectivity Hydrogen Gas Sensor Based on WO3/Pd-AlGaN/GaN HEMTs. Sensors 2023, 23, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colusso, E.; Rigon, M.; Corso, A.J.; Pelizzo, M.G.; Martucci, A. Optical Hydrogen Sensing Properties of e-Beam WO3 Films Decorated with Gold Nanoparticles. Sensors 2023, 23, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staerz, A.; Weimar, U.; Barsan, N. Current state of knowledge on the metal oxide based gas sensing mechanism. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 358, 131531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, P.K.; Chandu, B.; Puvvada, N. Recent Advances in Nanostructured Materials for Application as Gas Sensors. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 3092–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-Y.; Ou, L.-X.; Mao, L.-W.; Wu, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-P.; Lu, H.-L. Advances in Noble Metal-Decorated Metal Oxide Nanomaterials for Chemiresistive Gas Sensors: Overview. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Feng, S.; Qin, S.; Zhang, T. Heteronanostructural metal oxide-based gas microsensors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2022, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazoe, N. New Approaches for Improving Semiconductor Gas Sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1991, 5, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.X.; Yin, L.W.; Zhang, L.Y.; Xiang, D.; Gao, R. Metal Oxide Gas Sensors: Sensitivity and Influencing Factors. Sensors 2010, 10, 2088–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, H.B. The work function of the elements and its periodicity. J. Appl. Phys. 1977, 48, 4729–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Tan, Z.A. Bright prospect of using alcohol-soluble Nb2O5 as anode buffer layer for efficient polymer solar cells based on fullerene and non-fullerene acceptors. Org. Electron. 2018, 52, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Jee, S.H.; Kakati, N.; Maiti, J.; Kim, D.-J.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, H.H. Work function effects of ZnO thin film for acetone gas detection. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, S653–S656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morasch, J.; Wardenga, H.F.; Jaegermann, W.; Klein, A. Influence of grain boundaries and interfaces on the electronic structure of polycrystalline CuO thin films. Phys. Status Solidi A Appl. Mater. Sci. 2016, 213, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Peng, J.; Wang, W.; Xia, Z.; Yuan, J.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Ma, W.; Song, H.; Chen, W. Sequential deposition of CH3NH3PbI3 on planar NiO film for efficient planar perovskite solar cells. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, D.; Xie, T. Work function engineering derived all-solid-state Z-scheme semiconductor-metal-semiconductor system towards high-efficiency photocatalytic H2 evolution. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 66783–66787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, J.; Ong, C.W. Diffusion-controlled H2 sensors composed of Pd-coated highly porous WO3 nanocluster films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 191, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.-M.; Wei, Y.-C.; Li, Z.-Y.; Zhao, R.; Liu, G.-Z.; Geng, Y.-H.; et al. Vacuum Based Gas Sensing Material Characterization System for Precise and Simultaneous Measurement of Optical and Electrical Responses. Sensors 2022, 22, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ong, C.W. Improved H2-sensing performance of nanocluster-based highly porous tungsten oxide films operating at moderate temperature. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 174, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Huang, J.; Ong, C.-W. Preparation and structure dependence of H2 sensing properties of palladium-coated tungsten oxide films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 177, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.K. Opportunities and challenges in science and technology of WO3 for electrochromic and related applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklasson, G.A.; Granqvist, C.G. Electrochromics for smart windows: Thin films of tungsten oxide and nickel oxide, and devices based on these. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 127–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, R.; Engelhard, M.H.; Ramana, C. Correlation between surface chemistry, density, and band gap in nanocrystalline WO3 thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Qiao, Z.; Yi, Y.; Adhikari, K.K.; Liu, S.; Song, B. Effects of Microstructure and Stoichiometry on the Optical and Electrical Hydrogen Sensing Synchronous Properties of WO3-x. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 441, 137903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Kim, M.P. Advancements in Flexible and Stretchable Electronics for Resistive Hydrogen Sensing: A Comprehensive Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Cao, Y.; Su, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.; Xu, A.; Wu, T. Hydrogen Sensors Based on Pd-Based Materials: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrehn, S.; Wu, X.; Wagner, T. Tungsten Oxide Photonic Crystals as Optical Transducer for Gas Sensing. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroushani, F.T.; Tavanai, H.; Ranjbar, M.; Bahrami, H. Fabrication of tungsten oxide nanofibers via electrospinning for gasochromic hydrogen detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 268, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, M.A.; Ranjbar, M.; Kameli, P.; Salamati, H. Hydrogen sensing by wet-gasochromic coloring of PdCl2 (aq)/WO3 and the role of hydrophilicity of tungsten oxide films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 188, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal | Rair (Ω) | RH2 (Ω) | Se (Rair/RH2) | tres (s) | trec (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd | 6.993 × 106 | 6.833 × 103 | 1022 | 1 | 770 |

| Au | 1.758 × 107 | 2.094 × 106 | 8.4 | 112 | 806 |

| Pt | 3.085 × 106 | 1.387 × 105 | 22.4 | 0.5 | 632 |

| Ag | 2.763 × 106 | 2.403 × 106 | 1.15 | 239 | 285 |

| Al | 1.228 × 107 | 1.209 × 107 | - | - | - |

| Nb | 6.750 × 106 | 4.960 × 106 | 1.36 | 122 | 409 |

| Ta | 2.437 × 106 | 2.182 × 106 | 1.12 | 253 | 390 |

| Ti | 4.881 × 106 | 3.981 × 106 | 1.22 | 258 | 129 |

| Metal | Tair (%) | TH2 (%) | SO (Tair − TH2) (%) | tres (s) | trec (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd | 78.6 | 68.9 | 9.7 | 28 | 43 |

| Metal oxide | Rair (Ω) | RH2 (Ω) | SE (Rair/RH2) | tres (s) | trec (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiO | 1.099 × 107 | 1.019 × 107 | 1.08 | 25 | 9 |

| CuO | 1.031 × 107 | 8.315 × 106 | 1.24 | 150 | 753 |

| Nb2O5 | 1.609 × 107 | 1.279 × 107 | 1.26 | 120 | 782 |

| ZnO | 1.150 × 107 | 1.073 × 107 | 1.07 | 17 | 838 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Wei, J.; Ye, J.; Ye, W.; Li, Y.; Lv, Z.; Zhao, M. Investigation of Surface Modification Effects on the Optical and Electrical Hydrogen Sensing Characteristics of WO3 Films. Sensors 2025, 25, 7268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237268

Hu J, Wei J, Ye J, Ye W, Li Y, Lv Z, Zhao M. Investigation of Surface Modification Effects on the Optical and Electrical Hydrogen Sensing Characteristics of WO3 Films. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237268

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jiabin, Jie Wei, Jianmin Ye, Wen Ye, Ying Li, Zhe Lv, and Meng Zhao. 2025. "Investigation of Surface Modification Effects on the Optical and Electrical Hydrogen Sensing Characteristics of WO3 Films" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237268

APA StyleHu, J., Wei, J., Ye, J., Ye, W., Li, Y., Lv, Z., & Zhao, M. (2025). Investigation of Surface Modification Effects on the Optical and Electrical Hydrogen Sensing Characteristics of WO3 Films. Sensors, 25(23), 7268. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237268