A Survey on Privacy Preservation Techniques in IoT Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

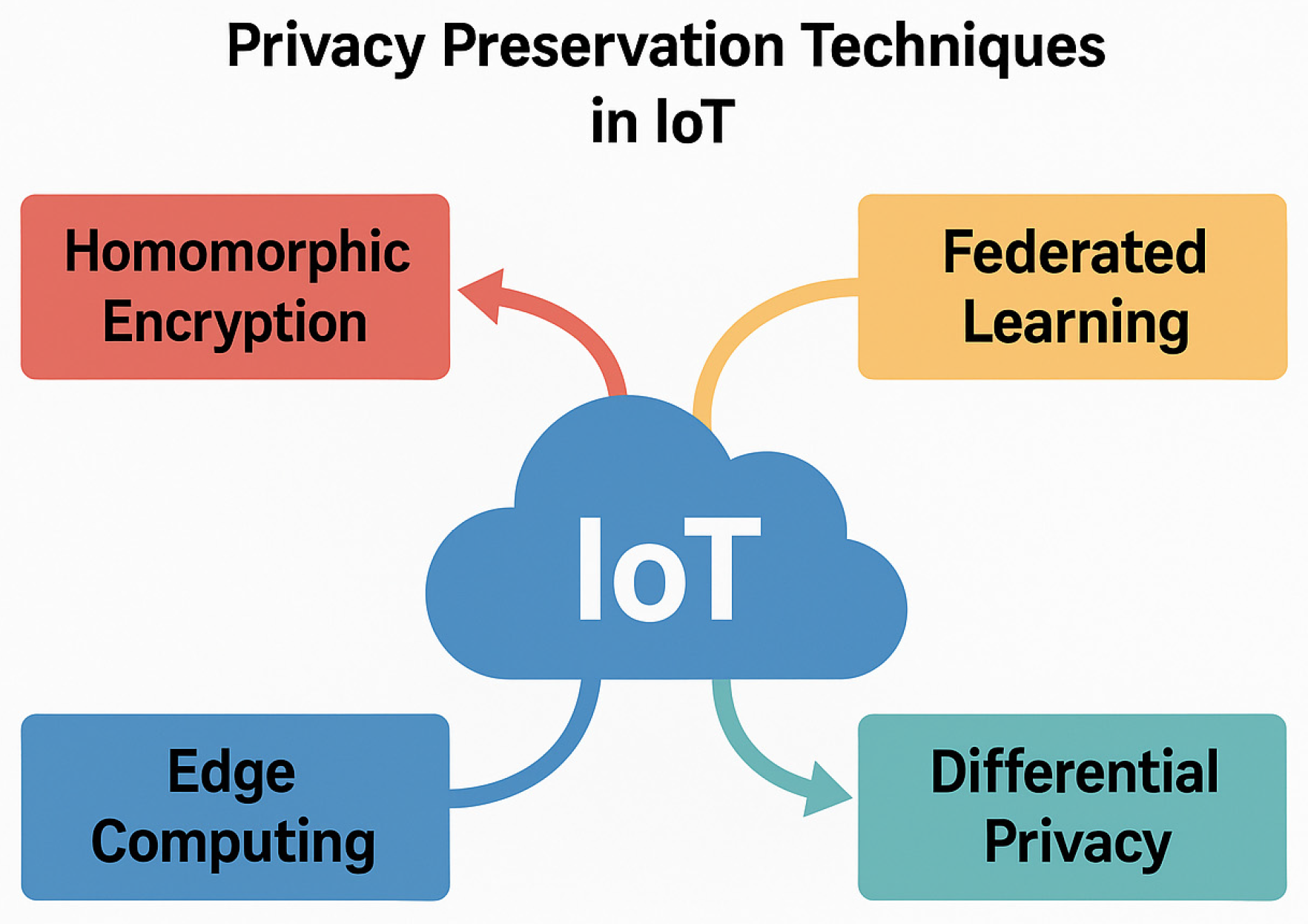

- Comprehensive Taxonomy: Presents a structured classification of privacy-preserving approaches—encryption-based, learning-based, blockchain-based, and hybrid mechanisms—used in IoT systems.

- Comparative Evaluation: Summarizes the datasets, analytical models, and experimental results from prior studies, highlighting strengths and weaknesses such as encryption efficiency, computational overhead, and data scalability.

- Cross-Domain Inclusion: Expands the literature to cover privacy mechanisms in smart homes, healthcare, vehicular IoT (VANET/IoV), and UAV-assisted systems, ensuring broad applicability across emerging domains.

- Identification of Research Gaps: Highlights unresolved challenges including lightweight cryptographic design, real-time privacy preservation in edge devices, and interoperability among heterogeneous IoT networks.

- Future Research Directions: Proposes energy-efficient, privacy-aware frameworks for next-generation IoT systems integrating AI, blockchain, and federated edge intelligence.

2. Methodology

3. Literature Review and Background

3.1. Research Questions

- RQ1: What are the major privacy-preserving techniques employed in IoT systems across different domains?

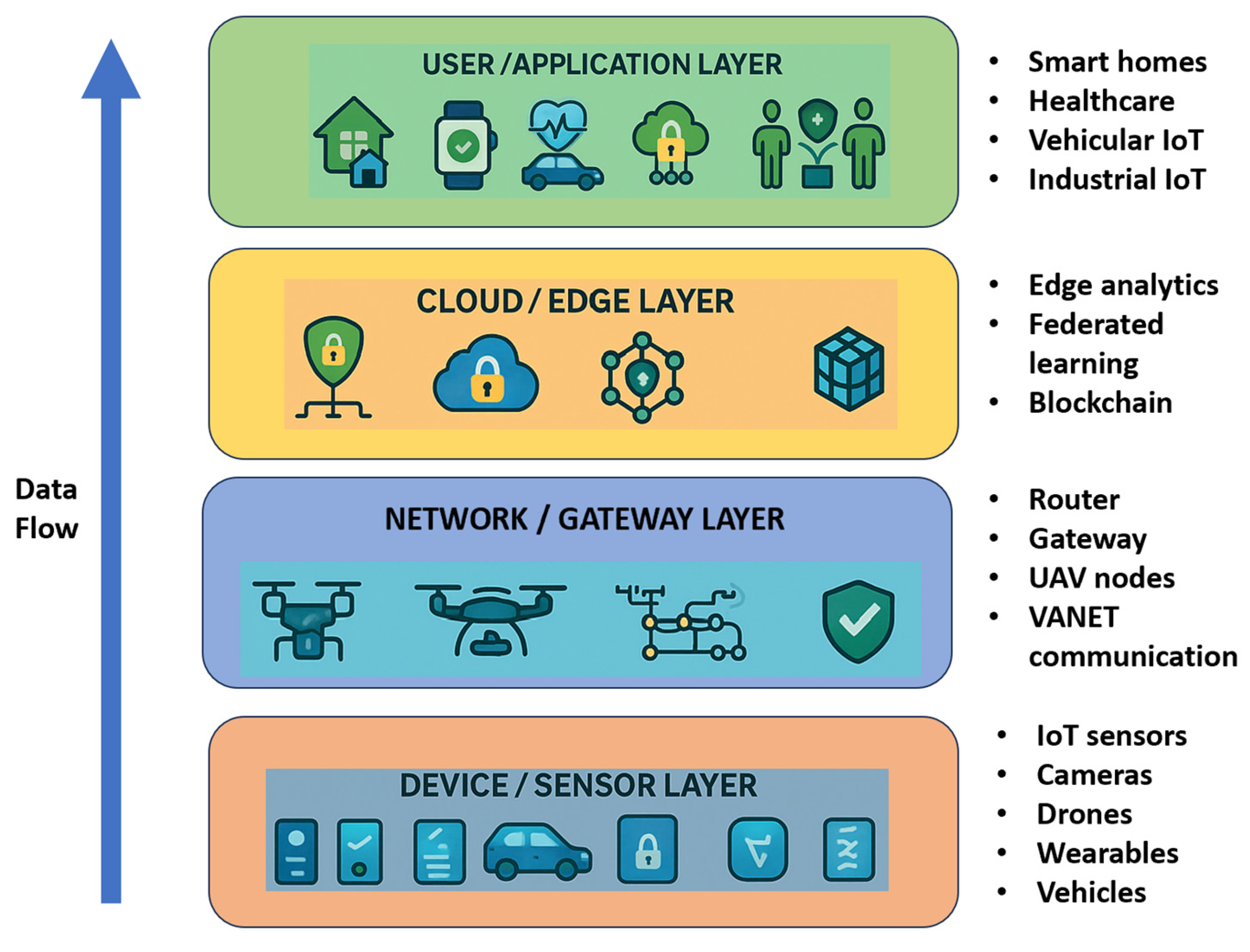

- RQ2: What types of IoT devices, edge nodes, and network infrastructures are targeted by these privacy mechanisms?

- RQ3: What are the common privacy threats and attack models addressed in recent research?

- RQ4: How do various methods—such as blockchain, federated learning, encryption, and differential privacy—compare in terms of performance, scalability, and computational cost?

- RQ5: What research gaps and open challenges remain in achieving efficient, real-time, and scalable privacy preservation for heterogeneous IoT environments?

3.2. Encryption- and Blockchain-Based Techniques

3.3. Learning-Based and Federated Approaches

3.4. Edge and Cloud Privacy Models

3.5. Application-Specific Privacy: Smart Homes, Vehicular IoT, and UAVs

3.6. Synthesis and Taxonomy Summary

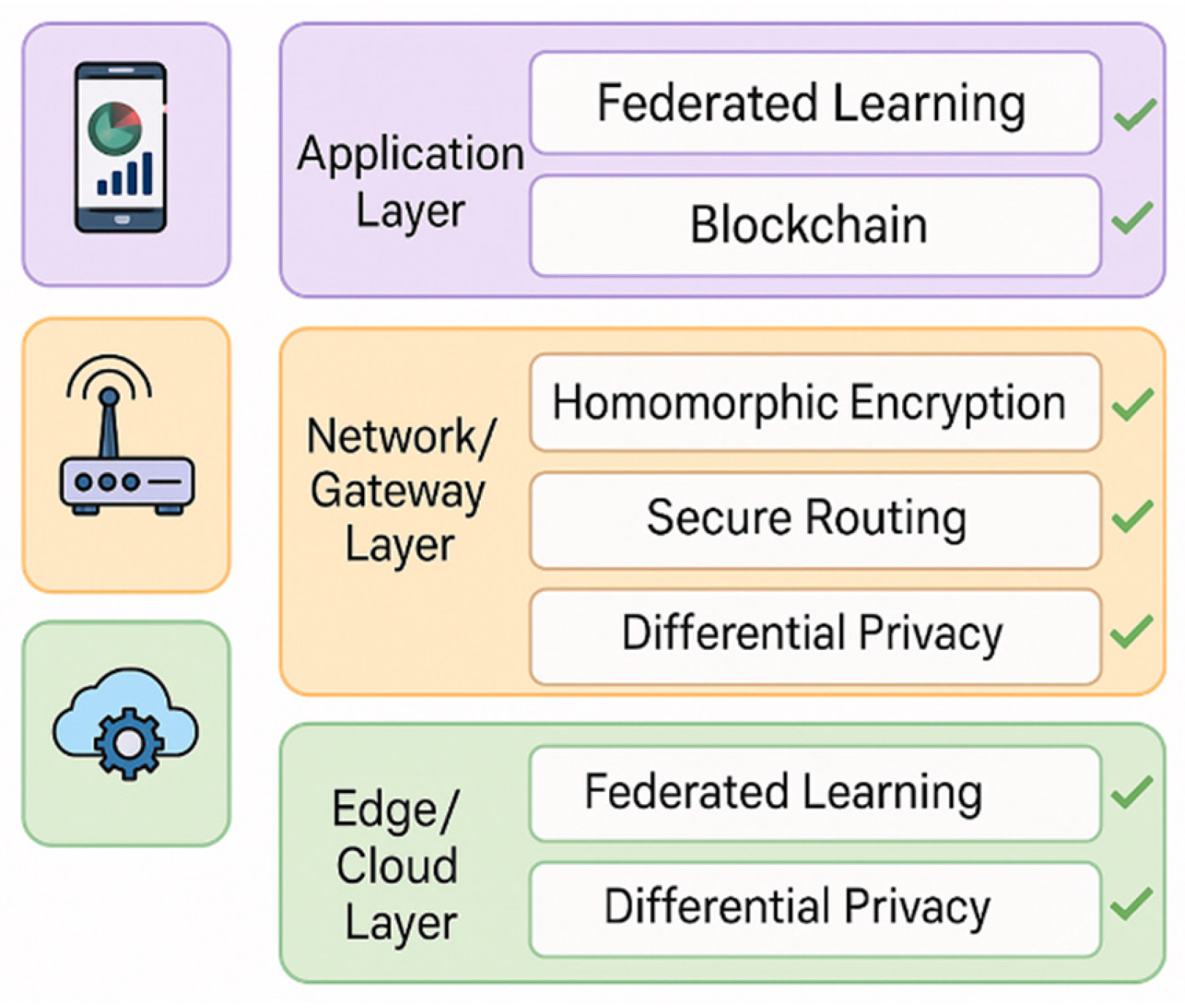

- Encryption/Blockchain-Based: Data confidentiality, decentralized trust, integrity protection.

- Learning-Based: Federated learning, TinyML, and differentially private optimization for distributed intelligence.

- Edge/Cloud Models: Secure offloading, TEEs, differential privacy at edge layers.

- Application-Specific Frameworks: Domain-driven privacy mechanisms for smart homes, vehicular IoT, healthcare, and UAVs.

3.7. Gaps and Research Directions

- Lightweight Cryptographic Design: Existing encryption and blockchain techniques are computationally intensive; optimized implementations for microcontrollers and low-power devices are needed.

- Energy-Aware Privacy Mechanisms: Energy consumption remains a limiting factor for continuous encryption and secure FL updates.

- Mobility-Aware Frameworks: VANETs and UAV-based IoT systems require adaptive privacy mechanisms that tolerate topology and connectivity changes.

- Cross-Domain Interoperability: Privacy solutions should enable seamless protection across smart home, healthcare, industrial, and vehicular IoT environments.

- Empirical Validation: Many proposed solutions remain theoretical; more real-world deployments and standardized testbeds are essential.

- Hybrid Privacy Architectures: Combining blockchain, FL, and differential privacy can yield scalable, decentralized, and robust IoT privacy models.

4. Data Sources and Types

5. Analytical Models Used

6. Discussions

6.1. Interpretation of Findings

6.2. Cross-Analysis with Research Questions

- RQ1 (Techniques): Privacy in IoT is dominated by four families—encryption, blockchain, FL/DP, and hybrid edge–cloud frameworks—each addressing different parts of the data lifecycle.

- RQ2 (Devices/Architectures): Most solutions target edge nodes and cloud infrastructure, while ultra-constrained sensor nodes remain under-protected.

- RQ3 (Threats): Commonly mitigated threats include data leakage, man-in-the-middle attacks, inference attacks in ML, and unauthorized access; emerging threats involve adversarial learning and blockchain data linkage.

- RQ4 (Comparative Effectiveness): FL and blockchain achieve decentralized privacy but trade off energy, latency, and communication efficiency; lightweight encryption still dominates resource-limited nodes.

- RQ5 (Gaps): Few studies present unified, end-to-end architectures that balance privacy, scalability, and energy efficiency across heterogeneous IoT tiers.

6.3. Emerging Trends and Research Implications

- Shift toward Decentralization: Future IoT privacy will rely on federated, peer-to-peer, and blockchain-enabled models rather than centralized authorities.

- Privacy–Energy Co-Optimization: Energy-aware encryption and adaptive training in FL are emerging to sustain privacy without depleting device resources.

- Edge Intelligence and Lightweight ML: Integrating TinyML and hierarchical FL supports on-device learning while minimizing data exposure, but model compression and personalization must be improved.

- Cross-Domain Privacy Frameworks: Unified architectures spanning smart homes, healthcare, and vehicular IoT are required to enable interoperability and standardization.

- Regulatory Alignment and Ethical Data Governance: The growing enforcement of GDPR-style privacy laws globally demands compliance-by-design models embedded into IoT systems.

- Hybrid Architectures: Combining blockchain, FL, and differential privacy offers complementary strengths—trust, decentralization, and statistical anonymity—suggesting a clear direction for next-generation IoT privacy frameworks.

6.4. Synthesis

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duarte, F. Exploding Topics, 22 February 2023. Available online: https://explodingtopics.com/blog/number-of-iot-devices (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Check Point. Check Point Research, 11 April 2013. Available online: https://blog.checkpoint.com/security/the-tipping-point-exploring-the-surge-in-iot-cyberattacks-plaguing-the-education-sector/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Xue, W.; Hu, W.; Gauranvaram, P.; Seneviratne, A.; Jha, S. An efficient privacy-preserving IoT system for face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 Workshop on Emerging Technologies for Security in IoT (ETSecIoT), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 21 April 2020; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yuhala, P. Enhancing IoT Security and Privacy with Trusted Execution Environments and Machine Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.02584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.; DiSalvo, L.; Ray, L. Automatic Classification of Web and IoT Privacy Policies. In Proceedings of the IEEE 19th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Smart Systems (MASS), Denver, CO, USA, 19–21 October 2022; pp. 732–735. [Google Scholar]

- Elkahlout, M.; Abu-Saqer, M.M.; Aldaour, A.F.; Issa, A.; Debeljak, M. IoT-Based Healthcare and Monitoring Systems for the Elderly: A Literature Survey Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Assistive and Rehabilitation Technologies (iCareTech), Gaza, Palestine, 28–29 August 2020; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Meenakshiammal, R.; Bharathi, R. Preserving Patient Privacy in IoT Based Breast Cancer Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Edge Computing and Applications (ICECAA), Namakkal, India, 19–21 July 2023; pp. 1370–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Schiliro, F.; Moustafa, N.; Beheshti, A. Cognitive privacy: AI-enabled privacy using EEG signals in the internet of things. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Conference on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud and Big Data Systems and Application (DependSys), Nadi, Fiji, 14–16 December 2020; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fazeldehkordi, E.; Owe, O.; Noll, J. Security and privacy in IoT systems: A case study of healthcare products. In Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology (ISMICT), Oslo, Norway, 8–10 May 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gochoo, M.; Tan, T.H.; Huang, S.C.; Batjargal, T.; Hsieh, J.W.; Alnajjar, F.S.; Chen, Y.F. Novel IoT-based privacy-preserving yoga posture recognition system using low-resolution infrared sensors and deep learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 7192–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jui, T.T.; Hoq, M.N.; Majumdar, S.; Hossain, M.S. Feature Reduction through Data Preprocessing for Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems and Applications (TPS-ISA), Atlanta, GA, USA, 13–15 December 2021; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fazeldehkordi, E.; Owe, O.; Noll, J. Security and Privacy Functionalities in IoT. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Fredericton, NB, Canada, 26–28 August 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fagbohungbe, O.; Reza, S.R.; Dong, X.; Qian, L. Efficient privacy-preserving edge intelligent computing framework for image classification in IoT. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2021, 6, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadeo, M.; Ruggeri, G. Exploring In-Network Computing with Information-Centric Networking: Review and Research Opportunities. Future Internet 2025, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.; Alotaibi, M. A stacked deep learning approach for IoT cyberattack detection. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 8828591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahani, N.; Elgazzar, K.; Cordy, J.R. Authentication and access control in e-health systems in the cloud. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data Security on Cloud (BigDataSecurity), IEEE International Conference on High Performance and Smart Computing (HPSC), and IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Data and Security (IDS), New York, NY, USA, 9–10 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meisami, S.; Atashgah, M.B.; Aref, M.R. Using blockchain to achieve decentralized privacy in IoT Healthcare. Int. J. Cybern. Inform. 2023, 12, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Sarwate, A.D.; Mandayam, N.B. Network Traffic Shaping for Enhancing Privacy in IoT Systems. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2022, 30, 1162–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azbeg, K.; Ouchetto, O.; Andaloussi, S.J. Access Control and Privacy-Preserving Blockchain-Based System for Diseases Management. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, N.C. A Privacy-Preserving Data Aggregation Scheme for Fog/Cloud-Enhanced IoT Applications Using a Trusted Execution Environment. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon), Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 April 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Faujdar, N.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, A. Security and Privacy of Blockchain-Based Single-Bit Cache Memory Architecture for IoT Systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 35273–35286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Wang, F.Y.; Tian, Y.; Jia, X.; Qi, H.; Wang, G. Artificial Identification: A Novel Privacy Framework for Federated Learning Based on Blockchain. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2022, 10, 3576–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugueoth, V.; Safavat, S.; Shetty, S.; Rawat, D. A Review of IoT Security and Privacy Using Decentralized Blockchain Techniques. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 50, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhariji, L.; De, S.; Rana, O.; Perera, C. Semantics-Based Privacy by Design for Internet of Things Applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 138, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G.; Chatterjee, P.; Lin, J.C.W. A Privacy-Preserving Internet of Things Smart Healthcare Financial System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 18452–18460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Namasudra, S.; Chilamkurti, N.; Kim, B.G.; Crespo, R.G. Blockchain-Based Privacy Preservation for IoT-Enabled Healthcare System. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2023, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Mukherjee, P.; Verma, S.; Kavita Shafi, J.; Wozniak, M.; Ijaz, M.F. A Smart Privacy Preserving Framework for Industrial IoT Using Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayeb, H.; Bramas, B.; Faverge, M.; Guermouche, A. Dynamic Tasks Scheduling with Multiple Priorities on Heterogeneous Computing Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium Workshops (IPDPSW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 27–31 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Wu, X.; Sun, P.; Zhou, H.; Wu, Z.; Yu, S. Optimal Privacy Preservation Strategies with Signaling Q-Learning for Edge-Computing-Based IoT. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 225, 120192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, T.; Gupta, R. Federated Learning and Its Role in the Privacy Preservation of IoT Devices. Future Internet 2022, 14, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaraziz, M.S.; Jalili, A.; Gheisari, M.; Liu, Y. Recent Trends Towards Privacy-Preservation in Internet of Things, Its Challenges and Future Directions. IET Circuits Devices Syst. 2023, 17, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Al-rimy, B.A.S.; Alsubaei, F.S.; Almazroi, A.A.; Almazroi, A.A. HealthLock: Blockchain-Based Privacy Preservation Using Homomorphic Encryption in Internet of Things Healthcare Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 6762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arachchige, P.C.M.; Bertok, P.; Khalil, I.; Liu, D.; Camtepe, S.; Atiquzzaman, M. A Trustworthy Privacy-Preserving Framework for Machine Learning in Industrial IoT Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 6092–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Power Estimation and Comparison of Heterogeneous CPU–GPU Processors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 25th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference (EPTC), Singapore, 6–8 December 2023; pp. 948–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anajemba, J.H.; Iwendi, C.; Razzak, I.; Ansere, J.A.; Okpalaoguchi, I.M. A Counter-Eavesdropping Technique for Optimized Privacy of Wireless Industrial IoT Communications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 6445–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunseyi, T.B.; Bo, T.; Yang, C. A Privacy-Preserving Framework for Cross-Domain Recommender Systems. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 93, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertino, E. Data Security and Privacy in the IoT. Open Proceeding 2016, 2016, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Pei, Q.; Zhang, N.; Liu, X.; Wu, C.; Taherkordi, A. Lightweight Federated Learning for Large-Scale IoT Devices with Privacy Guarantee. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3179–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathne, S.M.; Saxena, N.; Khan, M.K. Security and Privacy in IoT Smart Healthcare. IEEE Internet Comput. 2021, 25, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.; Wang, Z.; Hou, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Jin, D. Systematically Quantifying IoT Privacy Leakage in Mobile Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 7115–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Roy, A.; Misra, S.; Raghuwanshi, N.S. CASE: A Context-Aware Security Scheme for Preserving Data Privacy in IoT-Enabled Society 5.0. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 2497–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, N.; Kaur, R.; Rodrigues, T.; Kashef, R. Post COVID-19 Vaccination: Infection Rate Analysis Using Time Series Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Machine Intelligence and Smart Innovation (ICMISI), Alexandria, Egypt, 12–14 May 2024; pp. 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Comparative Analysis of Power Efficiency in Heterogeneous CPU-GPU Processors. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 756–758. [Google Scholar]

- Deebak, B.D.; Hwang, S.O. Privacy-Preserving Learning Model Using Lightweight Encryption for Visual Sensing Industrial IoT Devices. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025, 9, 3039–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Noise Suppression Using Gated Recurrent Units and Nearest Neighbor Filtering. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–16 December 2022; pp. 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Asad, A.; Mohammadi, F. A Comprehensive Review of Processing-in-Memory Architectures for Deep Neural Networks. Computers 2024, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Asad, A.; Al Abdul Wahid, S.; Mohammadi, F. A Survey of Advancements in Scheduling Techniques for Efficient Deep Learning Computations on GPUs. Electronics 2025, 14, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lai, J.; Li, X.; He, D.; Khan, M.K. RPIFL: Reliable and Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning for the Internet of Things. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 221, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. A Survey on Memory Subsystems for Deep Neural Network Accelerators. Future Internet 2022, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Hawash, H.; Moustafa, N.; Razzak, I.; Elfattah, M.A. Privacy-preserved learning from non-iid data in fog-assisted IoT: A federated learning approach. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Bansal, M. BDD Ordering and Minimization Using Various Crossover Operators in Genetic Algorithm. Int. J. Innov. Res. Electr. Electron. Instrum. Control. Eng. 2014, 2, 1247–1253. Available online: www.ijireeice.com (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Joshi, P.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Thapa, C.; Afli, H.; Scully, T. Enabling All In-Edge Deep Learning: A Literature Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 3431–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Wahid, S.A.; Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Mohammadi, F. Quantum Computing Circuit Design: A Tutorial. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Scientific Computing (ICASC), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 23–25 October 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Li, Q. A Survey on Privacy and Security Issues in IoT-Based Environments: Technologies, Protection Measures and Future Directions. Comput. Secur. 2025, 148, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tan, Q.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. Analyzing Consumer IoT Traffic from Security and Privacy Perspectives: A Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.16149. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, M.N.; Ali, M.A.; Khoo, S.Y.; Alkhedher, M. Federated Learning and TinyML on IoT Edge Devices: Challenges, Advances, and Future Directions. ICT Express 2025, 11, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ge, L.; Tian, L. Survey: Federated Learning Data Security and Privacy-Preserving in Edge-Internet of Things. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magara, T.; Zhou, Y. Internet of Things (IoT) of Smart Homes: Privacy and Security. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 2024, 7716956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, A.; Alazab, A.; Alazab, M.; Obeidat, A.; Singh, S.; Jan, T. Federated Learning for Intrusion Detection in IoT Environments: A Privacy-Preserving Strategy. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. A Survey on Cybersecurity in IoT. Future Internet 2025, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, G.P.; Donta, P.K.; Dustdar, S.; Prazeres, C. A Systematic Review on Privacy-Aware IoT Personal Data Stores. Sensors 2024, 24, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhinakaran, D.; Sankar, S.M.; Selvaraj, D.; Raja, S.E. Privacy-Preserving Data in IoT-Based Cloud Systems: A Comprehensive Survey with AI Integration. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.00794. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Tavallaie, O.; Chen, S.; Thilakarathna, K.; Seneviratne, S.; Toosi, A.N.; Zomaya, A.Y. Personalizing Federated Learning for Hierarchical Edge Networks with Non-IID Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.08872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Asad, A.; Mohammadi, F. A Heterogeneous Scheduling Approach for Efficient Memory Management in IoT Systems. In Proceedings of the 32nd IEEE/ACIS International Summer Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD 2025), Brampton, ON, Canada, 23–25 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shahraeeni, A.; Kaur, R.; Kochari, A.; Mohammadi, F.; Asad, A. Empowering IoT with Large Language Models: A Survey of Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 32nd IEEE/ACIS International Summer Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD 2025), Brampton, ON, Canada, 23–25 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lad, I.; Patel, R.; Patel, E.; Kaur, R.; Nasir, M.; Asad, A.; Mohammadi, F. AI-Enabled Phishing Links Detection Using Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 32nd IEEE/ACIS International Summer Conference on Software Engineering, Artificial Intelligence, Networking, and Parallel/Distributed Computing (SNPD 2025), Brampton, ON, Canada, 23–25 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gajera, J.; Jahnavi, A.; Pinto, N.; Kaur, R.; Asad, A.; Mohammadi, F. Machine Learning Based Dynamic Overload Surge Protection System for Electrical Appliances. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), London, UK, 25–28 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abdul Wahid, S.; Asad, A.; Kaur, R.; Nguyen, J.; Kalra, D.; Mohammadi, F. Heterogeneous CPU–GPU–Quantum Accelerator. In Proceedings of the 2025 10th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), Istanbul, Türkiye, 17–21 September 2025; pp. 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Application Domain | Technique Category | Method/Model (Keywords) | Dataset(s) | Key Findings | Noted Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | IoT networks | Learning-based (feature eng.) | Preprocessing + feature selection + J48/Bagging | MQTT-IoT-IDS-2020; NSL-KDD | Up to 99.86% accuracy with proper preprocessing/feature selection | Possible overfitting; limited cross-domain validation |

| [15] | General IoT (cyberattacks) | Learning-based (DL) | Stacked ResNets + meta-classifier | ICS Cyberattack; N-BaIoT | High accuracy, low per-packet latency | Overfitting risk; limited metrics beyond accuracy |

| [16] | e-Health cloud | Access control/crypto | AAM + ZK (Schnorr); fine-grained access | Impl. prototype | Confidentiality with manageable latency | Latency under load; scalability vs. stronger crypto |

| [17] | e-Health (IoT) | Blockchain + access control | AES + ECDSA + SHA-256; on-chain pointers | Conceptual (no dataset) | Decentralized access control; integrity | No empirical overhead analysis |

| [18] | General IoT | Differential privacy | Event-level DP traffic shaping | Synthetic streams | Privacy–delay trade-offs quantified | Bursty traffic harder to hide efficiently |

| [19] | e-Health monitoring | Blockchain + IPFS | Re-encryption proxy; PoA chain | Prototype | Secure, scalable storage split (on/off-chain) | Web-style system; real-time path untested |

| [20] | Fog/Cloud IoT | TEE-based aggregation | Intel SGX; heterogeneous data | Concept/prototype | Privacy for heterogeneous aggregation | Real-world deployment pending |

| [21] | Vehicular IoT | Blockchain auth. | Smart contracts; hash anchoring | Concept/prototype | Tamper-resistance for vehicle data | Latency/fault tolerance not analyzed |

| [31] | General IoT | Survey/Taxonomy | Privacy models; data minimization | — | Clear layering of privacy concerns | No implementation/experiments |

| [33] | Industrial IoT | Blockchain + ML + DP | PriModChain (FL + DP + contracts) | MNIST | Combines trust + privacy in ML sharing | High federation latency |

| [37] | Large-scale IoT | Lightweight FL | FedL (privacy-preserving) | MNIST | Linear-time growth with users | HE cost; still non-trivial overhead |

| [40] | Society 5.0 IoT | Context-aware sec. | CASE (post-encryption reduction) | UCI activity | Reduces post-encryption data size | Linear delay increase |

| [54] | Cross-domain IoT | Survey (encryption/blockchain) | Comprehensive taxonomy | — | Synthesizes device–network–cloud threats | Highlights energy/latency overheads |

| [55] | Consumer IoT (smart home) | Traffic privacy | Encrypted traffic analysis survey | — | Metadata leakage even without payloads | Need stronger traffic shaping/obfuscation |

| [56] | Edge IoT | FL + TinyML | On-device FL under constraints | — | Feasible FL/TinyML co-design | Accuracy–energy–latency trade-offs |

| [57] | Edge-IoT | FL security survey | FL + DP + HE + secure agg. | — | Catalogs FL privacy risks/defenses | Open issues: poisoning, non-IID, comms |

| [58] | Smart homes | Domain survey | AuthN/AuthZ; lightweight crypto | — | Domain-specific threat landscape | Fragmented device ecosystems |

| [59] | IoT intrusion detection | FL application | FL-based IDS (privacy-preserving) | Network traces | Preserves data locality; good detection | FL robustness to attacks still open |

| [60] | General IoT | Cybersecurity survey | Holistic IoT security incl. privacy | — | Broad coverage of threats/controls | High-level; fewer empirical results |

| [61] | User-centric IoT | Personal Data Stores | Privacy-aware PDS; consent/usage control | — | User control and transparency patterns | Adoption/standardization challenges |

| [62] | IoT + Cloud | Survey (AI + privacy) | DP, HE, AI-integrated pipelines | — | End-to-end pipeline considerations | Many proposals lack deployment data |

| [63] | Hierarchical edge IoT | FL personalization | Fed. learning on non-IID hierarchical edges | — | Personalization improves FL quality | Security/privacy of personalization layers |

| Ref. | Dataset/Source | Domain/Application | Size/Samples | Preprocessing and Description | Empirical/Theoretical Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Yale B Face Database | Face recognition for IoT cameras | 2414 images of 38 subjects | Images resized to 64 × 64 pixels; normalized grayscale; Bloom-filter encoding applied before classification | Empirical study |

| [7] | Custom IoMT Breast-Cancer Dataset | Healthcare (IoMT) | 5200 labeled records | Feature extraction (texture + shape), normalized; trained with CNN/ANN | Empirical study |

| [10] | Yoga Posture Dataset (Kaggle) | Human-posture sensing via IR sensors | 93,200 images of 26 postures; 224 × 224 px resolution | Images annotated manually; balanced per class; lighting and angle normalization performed | Empirical study |

| [11] | MQTT-IoT-IDS 2020/NSL-KDD | Intrusion detection for IoT networks | ~370 k samples (45 features) | Data cleaning, feature scaling, correlation-based feature selection | Empirical study |

| [13] | – | Industrial IoT privacy framework | N/A | Conceptual framework without dataset; analytical comparison only | Theoretical study (no data) |

| [15] | ICS Cyberattack/N-BaIoT | Cyberattack detection | 100 k network traces | Normalized flow features; applied stacked ResNet for classification | Empirical study |

| [16] | Prototype logs (hospital IoT) | e-Health access control | 8000 transaction logs | AES-encrypted patient data tested in simulated hospital network | Empirical study |

| [17] | – | e-Health blockchain privacy model | N/A | Architecture diagram only; simulated workflow | Theoretical study |

| [18] | Synthetic IoT Streams | Differential privacy traffic shaping | 1 M events | Laplace noise applied; latency vs. privacy ε measured | Empirical study |

| [19] | – | Blockchain + IPFS storage for health data | N/A | Framework described; no dataset | Theoretical study |

| [20] | Edge-Gateway Prototype Logs | Fog/Cloud aggregation | 25 k records | Simulated heterogeneous devices; TEE latency measured | Empirical study |

| [21] | Vehicular IoT Simulation (Veins/SUMO) | VANET blockchain auth. | 10 k vehicle events | Cryptographic hash and delay measured under mobility | Empirical study |

| [33] | MNIST | FL + DP model evaluation | 60 k images 28 × 28 px | Data normalized; DP noise added before aggregation | Empirical study |

| [54] | – | Cross-domain IoT survey | N/A | Review of multi-layer IoT privacy datasets | Theoretical survey |

| [56] | – | FL + TinyML edge framework | N/A | Conceptual FL prototype; simulation results only | Theoretical/simulation |

| [57] | – | FL security survey (Edge-IoT) | N/A | Literature synthesis | Theoretical survey |

| [59] | Network Trace Dataset (CICIDS 2018) | Intrusion detection via FL | ~80 k network flows | Flow normalization; feature scaling before FL training | Empirical study |

| [61] | – | IoT personal data store framework | N/A | Architecture discussion; no datasets | Theoretical study |

| [62] | – | IoT–Cloud AI privacy survey | N/A | Theoretical integration of AI and cloud privacy | Theoretical survey |

| Ref. | Model/Framework | Technique Category | Key Architectural or Mathematical Details (Plain-Text) | Evaluation Metric/Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Hybrid ML Pipeline (Decision Tree + SVM + Naïve Bayes) | Feature-based Learning | Ensemble voting classifier combining probabilistic and margin-based learners; normalized feature vector x in R^45. | Accuracy, Precision, Recall |

| [7] | CNN + ANN (IoMT Breast-Cancer Diagnosis) | Deep Learning | 5 Convolution layers (3 × 3 kernels) + 2 fully connected layers; ReLU activation; Softmax output; dropout rate 0.3. | Accuracy, Loss, F1-Score |

| [10] | Random Forest + Threshold Sensing | Shallow ML | Feature extraction from IR-sensor frames; temporal smoothing filter applied. | F1 = 0.9989, Precision, Recall |

| [11] | J48 Decision Tree + Bagging + Feature Selection | Classical ML IDS | Correlation-based Feature Selection (CFS); Bagging ensemble; 10-fold cross validation. | Accuracy 99.86% |

| [13] | Privacy Index Computation Model | Analytical Model | Privacy Index PI = 1 − (Sp/St), where Sp = sensitive data protected, St = total data collected. | Privacy Index |

| [15] | Stacked ResNet for Cyberattack Detection | Deep CNN | 5 ResNet blocks (each Conv + BatchNorm + ReLU + skip connection); Fusion layer concatenates multi-scale features; Softmax output (12 classes). | Accuracy, ROC-AUC, Latency |

| [16] | Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) + Access Control | Cryptographic Protocol | Schnorr-based ZKP: gr = a · yc (mod p); AES-128 encryption; ECC for key exchange. | Response Time, Security Level |

| [17] | Blockchain + Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) | Hybrid Framework | Smart-contract-controlled ABE with SHA-256 hash indexing and multi-signature verification. | Integrity Ratio, Latency |

| [18] | Event-Level Differential Privacy Model | Statistical Model | Laplace mechanism: x′ = x + Laplace(Δf/ε); evaluated privacy–delay trade-off. | Mean Latency, ε–Utility Curve |

| [19] | Blockchain + IPFS Hybrid Storage | Distributed System | Off-chain storage for encrypted payloads; on-chain metadata hashes; Proof-of-Authority consensus. | Access Latency, Throughput |

| [20] | Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) Aggregator | Secure Hardware Model | Intel SGX enclave executing encrypted aggregation; remote attestation enabled. | Aggregation Delay, Power |

| [21] | Blockchain-Based Vehicular Auth | Security Protocol | Smart contracts + hash chain; ECDSA elliptic-curve keys for authentication. | Avg. Tx Delay, Packet Loss |

| [33] | PriModChain (FL + DP + Blockchain) | Hybrid Privacy Framework | FL global model update: w_t = Σ_k (p_k · w_k); DP noise added before aggregation; on-chain update logging. | Accuracy, Latency, Privacy Budget |

| [37] | Lightweight Federated Learning (FedL) | Distributed Learning | Gradient compression ratio ρ = 0.5; secure aggregation using homomorphic encryption. | Accuracy, Communication Cost |

| [40] | Context-Aware Security Engine (CASE) | Contextual AI | Feature reduction via PCA; context-triggered encryption selection based on device state. | Accuracy, Response Time |

| [54] | Multi-Layer IoT Survey Model | Taxonomy Model | Classifies privacy mechanisms by layer (Device, Network, Edge, Cloud). | Conceptual Taxonomy |

| [56] | FL + TinyML Co-Design Framework | Edge Learning | Quantized 8-bit CNN for microcontrollers; FedAvg algorithm with local epoch E = 5. | Accuracy, Energy Consumption |

| [57] | Federated Learning Security Survey | Analytical Framework | Comparative analysis of HE, DP, and secure aggregation methods in Edge FL. | Conceptual Synthesis |

| [59] | FL-Based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) | Federated Application | FL with Adam optimizer; 3 dense layers (64-32-16 neurons); uses CICIDS 2018 dataset. | Detection Rate, F1-Score |

| [61] | Privacy-Aware Personal Data Store (PDS) | Data Management Model | Semantic ontology-based data schema; policy engine manages access tokens. | Qualitative Evaluation |

| Ref. | Technique/Focus | Major Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Bloom-filter-based face recognition (IoT) | Lightweight storage, 92% accuracy on Yale B dataset | Limited to facial data; prone to false positives |

| [7] | AES + Triple DES for IoMT (breast-cancer detection) | High classification accuracy (CNN 98.5%, ANN 99.2%) | High memory/storage demand; hardware-heavy |

| [10] | Device-free posture recognition via IR sensors | Near-perfect F1-score (0.9989); privacy-preserving sensing | Low-resolution sensors; deployment-scale untested |

| [11] | Feature-selection + ML for intrusion detection | Accurate (99.86%); shows preprocessing impact | Possible overfitting; limited datasets |

| [15] | Stacked ResNet for IoT cyberattack detection | High predictive accuracy; real-time packet analysis | Potential overfitting; lacks performance metrics |

| [16] | Zero-Knowledge + access control in e-Health | Strong authentication and anonymity | High response latency under load |

| [17] | Blockchain-based e-Health privacy | Decentralized access control; integrity | Theoretical; no performance validation |

| [19] | Blockchain + IPFS for medical data | Combines encryption, off-chain storage | Tested only as web prototype |

| [20] | TEE-based data aggregation | Privacy for heterogeneous data | Unimplemented for real IoT workloads |

| [21] | Blockchain for vehicular IoT | Secure, decentralized communication | Latency/fault tolerance not studied |

| [28] | G-BHO meta-heuristic for IIoT privacy | High security gain (>89%) | No real-world validation |

| [33] | PriModChain (Blockchain + FL + DP) | Integrates trust, privacy, learning | High federation latency; heavy computation |

| [37] | Lightweight FL (FedL) | Linear scaling with users | Homomorphic encryption cost high |

| [40] | CASE model for Society 5.0 IoT | Reduces post-encryption data size | Increases network delay linearly |

| [54] | Survey on IoT privacy/security | Comprehensive taxonomy; identifies multi-layer threats | High-level overview; lacks implementation metrics |

| [55] | Consumer IoT traffic analysis | Exposes metadata privacy leaks | Needs stronger traffic obfuscation |

| [56] | FL + TinyML on edge devices | Enables on-device learning under constraints | Energy–accuracy trade-off unresolved |

| [57] | FL data security survey (Edge-IoT) | Synthesizes FL privacy risks and countermeasures | Communication cost; non-IID challenges |

| [58] | Smart-home IoT privacy survey | Domain-specific threat insights | Fragmented vendor ecosystems |

| [59] | FL-based intrusion detection | Preserves data locality; strong detection | FL robustness to poisoning untested |

| [60] | IoT cybersecurity overview | Broad coverage of IoT threats and controls | Limited empirical depth |

| [61] | Privacy-aware personal data stores | User-centric transparency and consent | Lacks large-scale adoption examples |

| [62] | AI-integrated IoT cloud privacy survey | End-to-end data-pipeline view | No deployment metrics; conceptual |

| [63] | Hierarchical FL personalization | Improves FL accuracy for non-IID data | Security/privacy of personalization layers open |

| Ref. | Identified Research Gap | Recommended Future Direction |

|---|---|---|

| [3] | Bloom filter encoding is non-reversible and lacks data backup mechanism. | Introduce reversible key-based encryption integrated with bloom encoding. |

| [7] | CNN-based IoMT model demands high storage and computing resources. | Employ cloud/edge offloading and lightweight model compression. |

| [10] | Limited dataset (26 postures) reduces model generalization. | Extend experiments with larger, diverse subject datasets. |

| [11] | Handling of outliers and unbalanced data not discussed. | Integrate anomaly detection and adaptive re-sampling strategies. |

| [13] | Comparison with FL and SplitNN models missing. | Evaluate classifier performance vs. communication cost using federated settings. |

| [15] | Possible overfitting and lack of broader metrics. | Validate on cross-domain datasets and include latency/energy analysis. |

| [16] | Limited testing of non-common network threats. | Extend experiments to DDoS, poisoning, and replay attacks. |

| [17] | Model not implemented; computational cost unknown. | Prototype deployment for overhead and scalability analysis. |

| [18] | Shaper design efficiency under burst traffic uncertain. | Optimize event-level DP models using traffic correlation. |

| [19] | System limited to web-based prototype. | Develop real-time blockchain-enabled health monitoring testbeds. |

| [20] | Proof-of-concept lacks real-time validation. | Implement full-scale deployment using Intel SGX or AMD SEV. |

| [21] | Missing comparison for latency and fault tolerance. | Benchmark blockchain-based vehicular IoT under dynamic mobility. |

| [23] | Limited flexibility and latency in private FL. | Integrate RFID-based automatic on-chain identification. |

| [25] | Narrow application scope (six IoT use cases). | Broaden dataset; adopt chatbot-based PbD assistance. |

| [26] | Prototype not tested on real data. | Apply to large-scale finance or insurance IoT systems. |

| [28] | Evaluated only via simulation. | Validate industrial implementation using live sensor data. |

| [30] | Equilibrium model theoretical only. | Apply to aggregated IoT datasets for empirical confirmation. |

| [31] | No implementation evaluation. | Compare privacy-minimization methods experimentally. |

| [32] | Legal/ethical aspects missing. | Collaborate with healthcare regulators for compliance studies. |

| [33] | High latency in federated rounds. | Optimize communication scheduling and adaptive intervals. |

| [35] | Computationally heavy recommender model. | Explore pruning and parallel training to reduce overhead. |

| [37] | Limited balance between privacy and speed. | Investigate hybrid HE + DP approaches for efficiency. |

| [39] | Metrics for privacy leakage unclear. | Extend model evaluation with multiple datasets and leak indices. |

| [40] | Performance comparison incomplete. | Analyze accuracy–latency trade-offs with additional models. |

| [41] | Extra hashing adds overhead on WSNs. | Develop lightweight hash variants for constrained sensors. |

| [54] | Lack of empirical validation across multi-layer IoT. | Conduct quantitative benchmarks and real deployments. |

| [55] | Metadata-level leaks not fully addressed. | Apply advanced traffic obfuscation and packet padding. |

| [56] | Energy–accuracy trade-off unresolved in FL/TinyML. | Co-optimize energy consumption and model precision. |

| [57] | Limited exploration of poisoning and communication costs. | Employ secure aggregation and adaptive client selection. |

| [58] | Fragmented device ecosystems in smart homes. | Standardize protocols and unify vendor authentication layers. |

| [59] | FL intrusion detection untested against adversarial attacks. | Include adversarial robustness evaluation. |

| [60] | High-level survey, lacks quantitative depth. | Incorporate performance benchmarking of cited solutions. |

| [61] | PDS adoption slow due to missing standards. | Establish interoperability frameworks and open APIs. |

| [62] | Conceptual AI–IoT integration lacks deployment results. | Build AI-driven, privacy-aware IoT cloud demonstrators. |

| [63] | Personalization layer in hierarchical FL unverified. | Investigate secure personalization preserving user privacy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaur, R.; Rodrigues, T.; Kadir, N.; Kashef, R. A Survey on Privacy Preservation Techniques in IoT Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 6967. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226967

Kaur R, Rodrigues T, Kadir N, Kashef R. A Survey on Privacy Preservation Techniques in IoT Systems. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6967. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226967

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaur, Rupinder, Tiago Rodrigues, Nourin Kadir, and Rasha Kashef. 2025. "A Survey on Privacy Preservation Techniques in IoT Systems" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6967. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226967

APA StyleKaur, R., Rodrigues, T., Kadir, N., & Kashef, R. (2025). A Survey on Privacy Preservation Techniques in IoT Systems. Sensors, 25(22), 6967. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226967