Electrospun Nanofiber Platforms for Advanced Sensors in Livestock-Derived Food Quality and Safety Monitoring: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Meat Quality Deterioration & Markers

3. Electrospinning Process Overview

4. Materials for Electrospun Nanofiber Sensors

4.1. Synthetic Polymers

4.2. Natural Polymers

4.3. Composite and Functionalized Fibers

4.4. Mechanical and Structural Stability

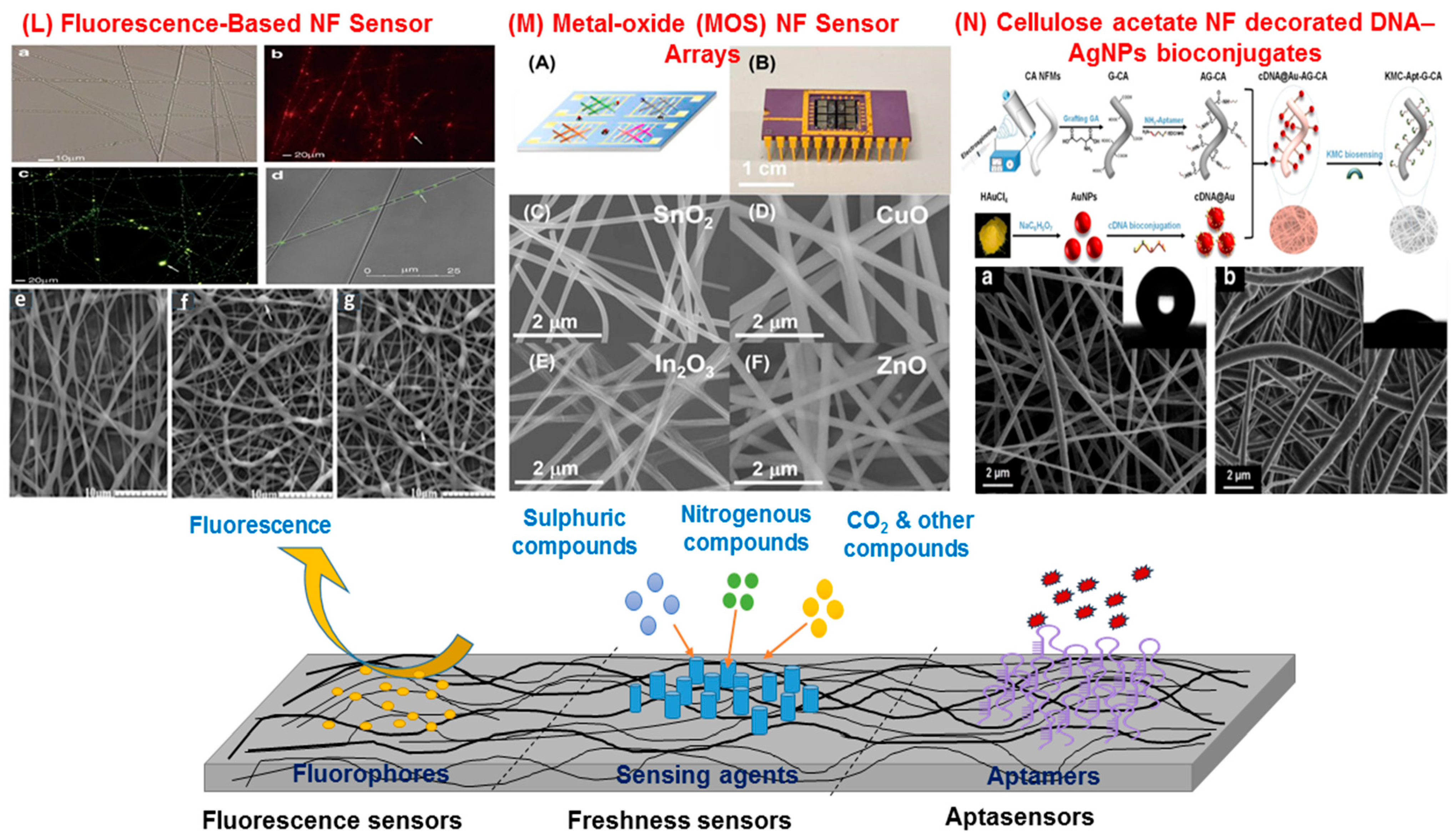

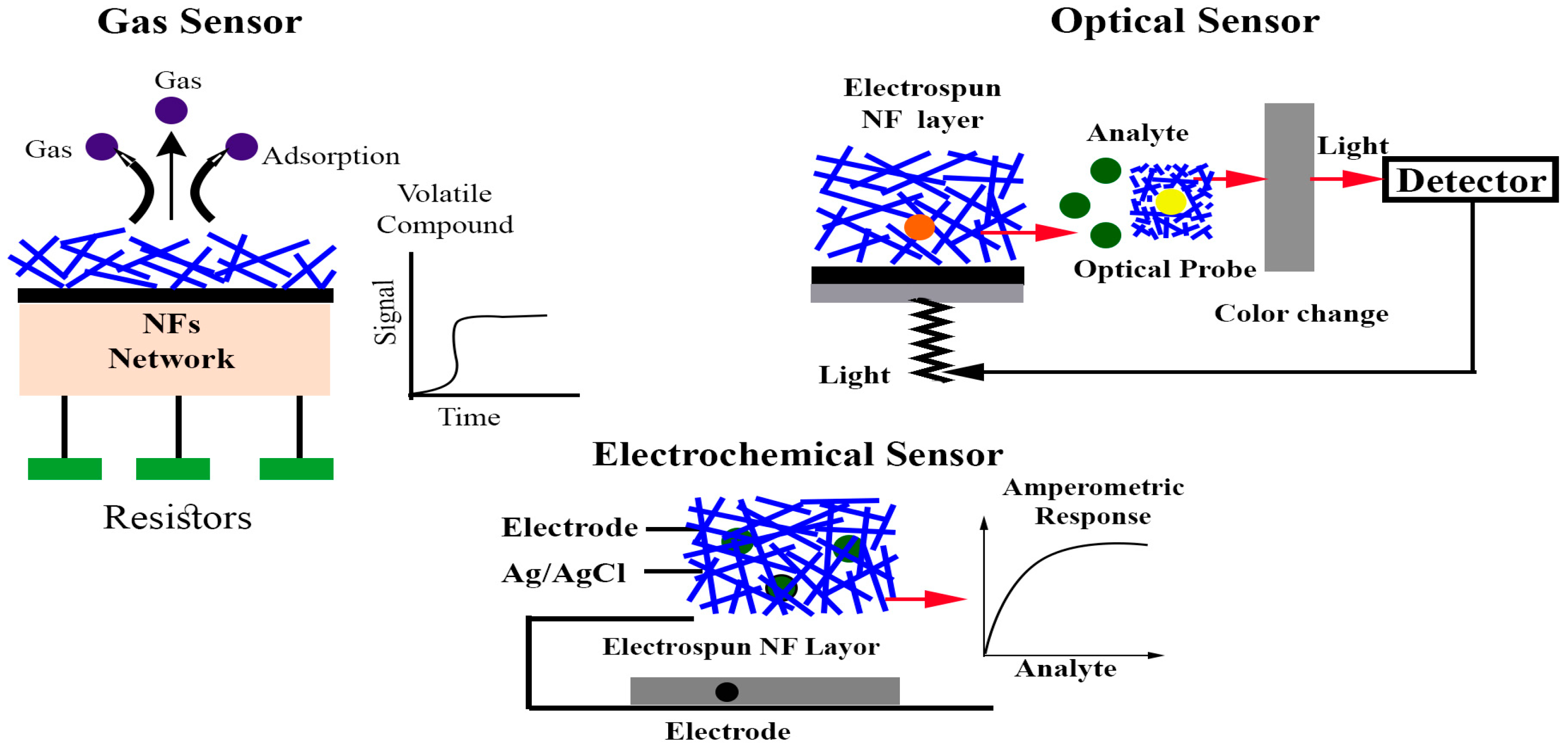

5. Optical Sensors for Visual and Spectral Analysis

5.1. Colorimetric Freshness Indicators

5.2. Fluorescent Sensors

5.3. SERS Substrates for Trace Contaminant Detection

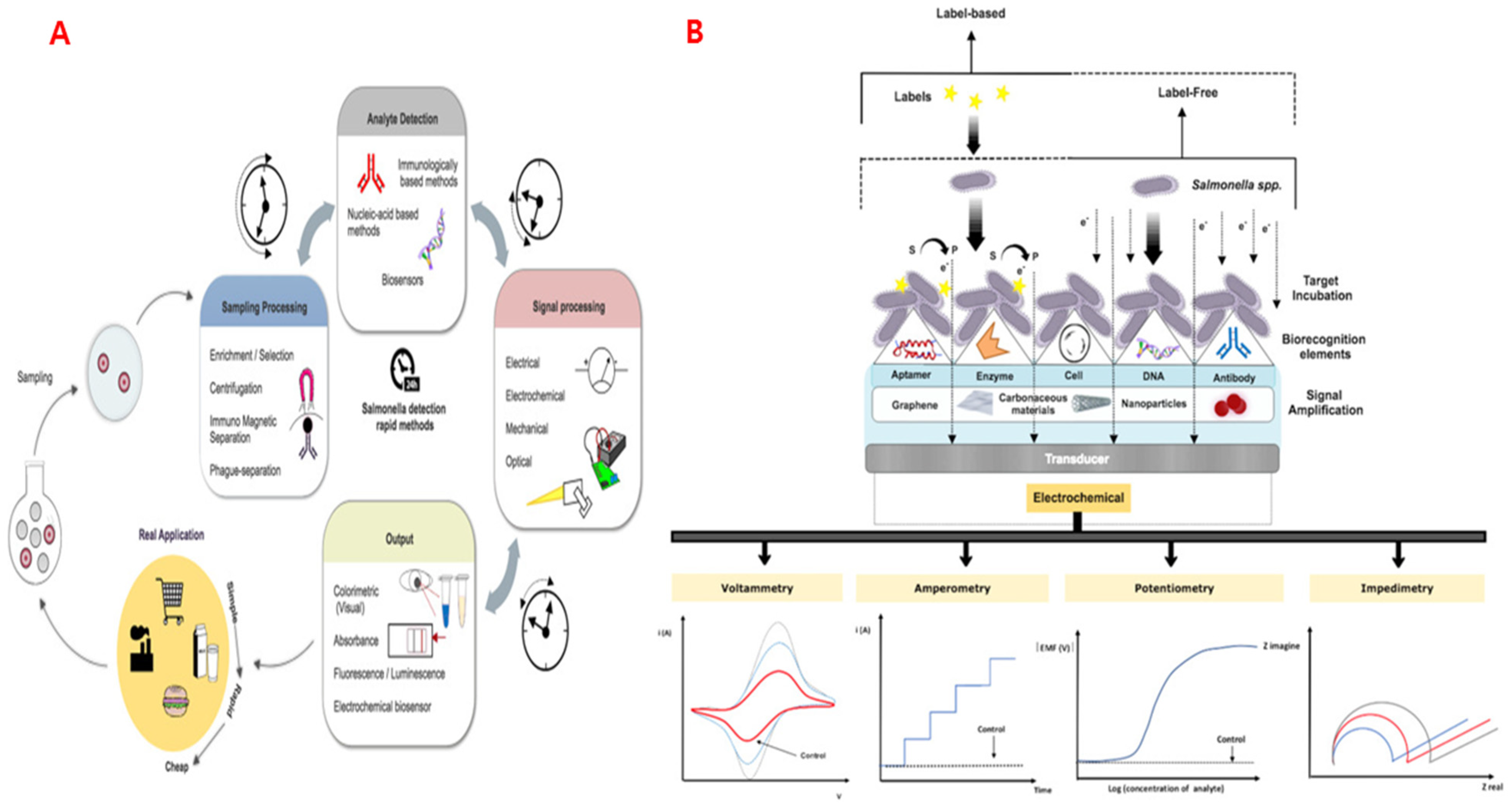

6. Electrochemical Sensors for Precise Quantification

6.1. Carbon Nanofiber (CNF) Electrodes

6.2. Enzyme-Based Sensors

6.3. Aptamer-Based Sensors

7. Resistive Gas Sensors (Electronic Noses)

8. Functional Roles and Comparative Performance of Electrospun NF-Based Sensors

9. Challenges and Future Perspectives

10. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buzby, J.C.; Bentley, J.T.; Padera, B.; Campuzano, J.; Ammon, C. Updated Supermarket Shrink Estimates for Fresh Foods and Their Implications for ERS Loss-Adjusted Food Availability Data; EIB-155; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotariu, L.; Lagarde, F.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Bala, C. Electrochemical biosensors for fast detection of food contaminants—Trends and perspective. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 79, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi-Varnamkhasti, M.; Apetrei, C.; Lozano, J.; Anyogu, A. Potential use of electronic noses, electronic tongues and biosensors as multisensor systems for spoilage examination in foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Nartker, S.; Miller, H.; Hochhalter, D.; Wiederoder, M.; Wiederoder, S.; Setterington, E.; Drzal, L.T.; Alocilja, E.C. Surface functionalization of electrospun nanofibers for detecting E. coli O157:H7 and BVDV cells in a direct-charge transfer biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1612–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forghani, S.; Almasi, H.; Moradi, M. Electrospun nanofibers as food freshness and time-temperature indicators: A new approach in food intelligent packaging. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 73, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Ramachandraiah, K.; Zhao, C. Advances in the development and applications of nanofibers in meat products. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topuz, F.; Uyar, T. Antioxidant, antibacterial and antifungal electrospun nanofibers for food packaging applications. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmatkeshan, M.; Gheybi, F.; Rezayat, S.M.; Jaafari, M.R. Polymer-Based Nanofibers: Preparation, Fabrication, and Applications. In Handbook of Nanofibers; Barhoum, A., Bechelany, M., Makhlouf, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Tao, D.; Xu, Y. Nanofibers: Principles and manufacture. In Functional Nanofibers and Their Applications; Wei, Q., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsani, N.; Rostamabadi, H.; Dadashi, S.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Kharazmi, M.S.; Jafari, S.M. Electrospun nanofibers fabricated by natural biopolymers for intelligent food packaging. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 5016–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morie, A.; Garg, T.; Goyal, A.K.; Rath, G. Nanofibers as novel drug carrier—An overview. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megelski, S.; Stephens, J.S.; Chase, D.B.; Rabolt, J.F. Micro- and Nanostructured Surface Morphology on Electrospun Polymer Fibers. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 8456–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.; Mananquil, T.; Scenna, R.; Dennis, E.S.; Castillo-Rodriguez, J.; Koivisto, B.D. Light-Driven Energy and Charge Transfer Processes between Additives within Electrospun Nanofibres. Molecules 2023, 28, 4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman Mohammadi, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Yousefi, M. Application of electrospinning technique in development of intelligent food packaging: A short review of recent trends. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4656–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Schueren, L.; De Meyer, T.; Steyaert, I.; Ceylan, Ö.; Hemelsoet, K.; Van Speybroeck, V.; De Clerck, K. Polycaprolactone and polycaprolactone/chitosan nanofibres functionalised with the pH-sensitive dye Nitrazine Yellow. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 91, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudpour, Y.; Hossain, S.; Khalil, H.P.S.A.; Haafiz, M.K.M.; Ishak, Z.A.M.; Hassan, A.; Sarker, Z.I. Optimization of high pressure homogenization parameters for the isolation of cellulosic nanofibers using response surface methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 74, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Bonakdar, M.; Rodrigue, D. Electrospinning: Processes, Structures, and Materials. Macromol 2024, 4, 58–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.M.; Dakhili, S.; Mirza Alizadeh, A.; Kooki, S.; Hassanzadazar, H.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; McClements, D.J. New perspectives on electrospun nanofiber applications in smart and active food packaging materials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 2601–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, D.; Ghaly, A.E. Meat spoilage mechanisms and preservation techniques: A critical review. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2011, 6, 486–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinquart, A.; Ellies-Oury, M.P.; Hocquette, J.F.; Guillier, L.; Santé-Lhoutellier, V.; Prache, S. Review: On-farm and processing factors affecting bovine carcass and meat quality. Animal 2022, 16, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaytsev, V.; Tutukina, M.N.; Chetyrkina, M.R.; Shelyakin, P.V.; Ovchinnikov, G.; Satybaldina, D.; Kondrashov, V.A.; Bandurist, M.S.; Seilov, S.; Gorin, D.A.; et al. Monitoring of meat quality and change-point detection by a sensor array and profiling of bacterial communities. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1320, 343022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Escher, A.; Bertucci, S.; Castellano, M.; Lova, P. Intelligent Packaging for Real-Time Monitoring of Food-Quality: Current and Future Developments. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurul Alam, A.M.M.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kumari, S.; Lee, E.Y.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Scaffolding fundamentals and recent advances in sustainable scaffolding techniques for cultured meat development. Food Res. Int. 2024, 189, 114549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Min, T.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, C.; Yin, H.; Yue, J. The developments and trends of electrospinning active food packaging: A review and bibliometrics analysis. Food Control 2024, 160, 110291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Xia, C.; Huang, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, D.; Xu, W.; Wang, D. An electrospun sensing label based on poly (vinyl alcohol)-Ag-grape seed anthocyanidin nanofibers for smart, real-time meat freshness monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 376, 132975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, J.; Wei, H.; Wu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Pei, Y. Fabrication of Ag NPs decorated on electrospun PVA/PEI nanofibers as SERS substrate for detection of enrofloxacin. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 2314–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, Y.; Jia, L.; Saldaña, M.D.A.; Dong, T.; Jin, Y.; Sun, W. A smart nanofibre sensor based on anthocyanin/poly-l-lactic acid for mutton freshness monitoring. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E.; Sumnu, G.; Kahyaoglu, L.N. Monitoring freshness of chicken breast by using natural halochromic curcumin loaded chitosan/PEO nanofibers as an intelligent package. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 170, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Dhanya, B.S.; Verma, M.L. Nano-immobilized biocatalysts and their potential biotechnological applications in bioenergy production. Materials Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 3, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yagi, S.; Ashour, S.; Du, L.; Hoque, M.E.; Tan, L. A Review on Current Nanofiber Technologies: Electrospinning, Centrifugal Spinning, and Electro-Centrifugal Spinning. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2023, 308, 2200502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Jia, X.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B.; Wang, H. Enhancing physical properties of chitosan/pullulan electrospinning nanofibers via green crosslinking strategies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 247, 116734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Phillips, G.O.; Yang, G. Utilization of bacterial cellulose in food. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 35, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Adedeji, O.E.; Kim, G.Y.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, D.H.; Jung, Y.H. Development of a pH indicator for monitoring the freshness of minced pork using a cellulose nanofiber. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, H.S.; Rashid, R.; Amna, T.; Hamid, R.; Sheikh, F.A. Recent advances in formulating electrospun nanofiber membranes: Delivering active phytoconstituents. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Application of glycyrrhiza polysaccharide nanofibers loaded with tea tree essential oil/gliadin nanoparticles in meat preservation. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Musale, S.; Panzade, P.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Sonwane, P.; Madibone, M.; Choundhe, P.; Giram, P.; Cavalu, S. Surface Functionalization of Nanofibers: The Multifaceted Approach for Advanced Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhuang, J.-R.; Lou, S.-N.; Lin, S.-B.; Chen, S.H.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, H.-H. Immobilizing laccase on electrospun chitosan fiber to prepare time-temperature indicator for food quality monitoring. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 63, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjwal, M.A.; Barakat, N.A.M.; Sheikh, F.A.; Khil, M.S.; Kim, H.Y. Functionalization of Electrospun Titanium Oxide Nanofibers with Silver Nanoparticles: Strongly Effective Photocatalyst. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2010, 7, E54–E63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facure, M.H.M.; Mercante, L.A.; Correa, D.S. Polyacrylonitrile/Reduced Graphene Oxide Free-Standing Nanofibrous Membranes for Detecting Endocrine Disruptors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 6376–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aswar, E.I.; Ramadan, H.; Elkik, H.; Taha, A.G. A comprehensive review on preparation, functionalization and recent applications of nanofiber membranes in wastewater treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azevedo, C.R.; von Stosch, M.; Costa, M.S.; Ramos, A.M.; Cardoso, M.M.; Danhier, F.; Préat, V.; Oliveira, R. Modeling of the burst release from PLGA micro- and nanoparticles as function of physicochemical parameters and formulation characteristics. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 532, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abduljabbar, A.; Farooq, I. Electrospun Polymer Nanofibers: Processing, Properties, and Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militký, J.; Novotná, J.; Wiener, J.; Křemenáková, D.; Venkataraman, M. Microplastics and Fibrous Fragments Generated during the Production and Maintenance of Textiles. Fibers 2024, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yin, L.; Jayan, H.; Sun, C.; Peng, C.; Zou, X.; Guo, Z. Multiplexed optical sensors driven by nanomaterials for food and agriculture safety detection: From sensing strategies to practical challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2025, 193, 118428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan-Mahdavi, S.; Mirbagheri, M.S.; Assadpour, E.; Sani, M.A.; Zhang, F.; Jafari, S.M. Electrospun nanofiber-based sensors for the detection of chemical and biological contaminants/hazards in the food industries. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 325, 103111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halonen, N.; Pálvölgyi, P.S.; Bassani, A.; Fiorentini, C.; Nair, R.; Spigno, G.; Kordas, K. Bio-Based Smart Materials for Food Packaging and Sensors—A Review. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, K.K.; Konwar, A.; Borah, A.; Saikia, A.; Barman, P.; Hazarika, S. Cellulose nanofiber mediated natural dye based biodegradable bag with freshness indicator for packaging of meat and fish. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.A.; de Arruda, I.N.Q.; Stefani, R. Active chitosan/PVA films with anthocyanins from Brassica oleraceae (Red Cabbage) as Time–Temperature Indicators for application in intelligent food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Yu, S.; Sun, J.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, J.; Tong, C.; Hu, Y.; Pang, J.; Wu, C. Development and characterization of electrospun nanofibers based on pullulan/chitin nanofibers containing curcumin and anthocyanins for active-intelligent food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 187, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; Yan, H.; Cao, J. Machine learning-assisted electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofiber mats colorimetric sensor array for rapid and accurate freshness assessment. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2026, 446, 138686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; He, H.; Zhou, H.; Liang, Y.; Wang, L.; Tian, S.; Wang, S. Designing an intelligent nanofiber ratiometric fluorescent sensor sensitive to biogenic amines for detecting the freshness of shrimp and pork. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 333, 129535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.C.; Wang, X.X.; Liu, J.J.; Li, R.; Yu, M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Long, Z. Ultrasensitive and Recyclable Upconversion-Fluorescence Fibrous Indicator Paper with Plasmonic Nanostructures for Single Droplet Detection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1900364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajikhani, M.; Kousheh, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, M. Design of a novel SERS substrate by electrospinning for the detection of thiabendazole in soy-based foods. Food Chem. 2024, 436, 137703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, D.; Nath, K.K.; Biswas, S.; Chetia, I.; Badwaik, L.S.; Ahmed, G.A.; Nath, P. SERS determination and multivariate classification of antibiotics in chicken meat using gold nanoparticle–decorated electrospun PVA nanofibers. Microchim. Acta 2023, 190, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zou, Y.; Farooq, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Novel Ag-coated nanofibers prepared by electrospraying as a SERS platform for ultrasensitive and selective detection of nitrite in food. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hurren, C.; Lu, Z.; Wang, D. Nanofiber-based colorimetric platform for point-of-care detection of E. coli. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.; Ikram, M.; Ahmad, D.; Naseer Abbas, M.; Shafique, M. Advancements in colorimetric and fluorescent-based sensing approaches for point-of-care testing in forensic sample analysis. Microchem. J. 2024, 206, 111438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiao, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, P.; Yin, T. Electrospun composite nanofibers containing nanoparticles for the programmable release of dual drugs. Polym. J. 2011, 43, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Xi, J.; Deng, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, H. Recent Development of Polymer Nanofibers in the Field of Optical Sensing. Polymers 2023, 15, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedalwafa, M.A.; Tang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Mei, Q.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. An aptasensor strip-based colorimetric determination method for kanamycin using cellulose acetate nanofibers decorated DNA–gold nanoparticle bioconjugates. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, C.; Zhou, H.; Ma, K.; Yano, Y.; Li, S.; Yamahara, H.; Seki, M.; Iizuka, T.; Tabata, H. Electronic nose based on multiple electrospinning nanofibers sensor array and application in gas classification. Front. Sens. 2023, 4, 1170280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, B.; Shen, C.; Lai, O.M.; Tan, C.P.; Cheong, L.Z. Electrochemical Biosensing of Chilled Seafood Freshness by Xanthine Oxidase Immobilized on Copper-Based Metal–Organic Framework Nanofiber Film. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Bai, L.; Pan, C.; Liu, Z.; Ramakrishna, S. Design, Fabrication and Applications of Electrospun Nanofiber-Based Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrate. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 53, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhai, F.; Du, R.; Liu, Y.; Lai, K. Analyses of enrofloxacin, furazolidone and malachite green in fish products with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chin, W.S. Rapid and sensitive SERS detection of melamine in milk using Ag nanocube array substrate coupled with multivariate analysis. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaani, M.; Azimzadeh, M.; Büyüktaş, D.; Carullo, D.; Farris, S. Electrochemical Sensors in the Food Sector: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 24170–24190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulshreshtha, N.M.; Shrivastava, D.; Bisen, P.S. Contaminant sensors: Nanotechnology-based contaminant sensors. Nanobiosensors 2017, 573–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.F.D.; Magalhães, J.M.C.S.; Freire, C.; Delerue-Matos, C. Electrochemical biosensors for Salmonella: State of the art and challenges in food safety assessment. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 99, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.W.; Dey, B.; Sarkhel, G.; Yang, D.-J.; Choudhury, A. Sea-urchin-like cobalt-MOF on electrospun carbon nanofiber mat as a self-supporting electrode for sensing of xanthine and uric acid. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 920, 116646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.A.; Ahmed, M.U. A label free electrochemical immunosensor for sensitive detection of porcine serum albumin as a marker for pork adulteration in raw meat. Food Chem. 2016, 206, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiha, A.; Ibrahim, F.; Muniandy, S.; Dinshaw, I.J.; Teh, S.J.; Thong, K.L.; Leo, B.F.; Madou, M. All-Carbon Suspended Nanowire Sensors as a Rapid Highly-Sensitive Label-Free Chemiresistive Biosensing Platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 107, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.; Saber, R.; Adabi, M.; Rasouli, R.; Douraghi, M.; Morshedi, M.; Farid-Majidi, R. Novel Competitive Voltammetric Aptasensor Based on Electrospun Carbon Nanofibers-Gold Nanoparticles Modified Graphite Electrode for Salmonella Enterica Serovar Detection. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 8702–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štukovnik, Z.; Fuchs-Godec, R.; Bren, U. Nanomaterials and Their Recent Applications in Impedimetric Biosensing. Biosensors 2023, 13, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Huang, P.J.J.; Ding, J.; Liu, J. Aptamer-based biosensors for biomedical diagnostics. Analyst 2014, 139, 2627–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Shen, J.; Liu, Q.; Fa, H.; Yang, M.; Hou, C. A novel electrochemical aptasensor for sensitive detection of kanamycin based on UiO-66-NH2/MCA/MWCNT@rGONR nanocomposite. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 4967–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moghazy, A.Y.; Amaly, N.; Istamboulie, G.; Nitin, N.; Sun, G. A signal-on electrochemical aptasensor based on silanized cellulose nanofibers for rapid point-of-use detection of ochratoxin A. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, M.; Pexara, A.; Solomakos, N.; Govaris, A. Ochratoxin A in Slaughtered Pigs and Pork Products. Toxins 2022, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaeifar, A.; ZakiDizaji, H.; Jafari, A.; de la Guardia, M. Early detection of contamination and defect in foodstuffs by electronic nose: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 97, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonezzer, M.; Thi Thanh Le, D.; Van Duy, L.; Hoa, N.D.; Gasperi, F.; Van Duy, N.; Biasioli, F. Electronic noses based on metal oxide nanowires: A review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 897–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, R.S.; Facure, M.H.M.; Mercante, L.A.; Correa, D.S. Electronic nose based on hybrid free-standing nanofibrous mats for meat spoilage monitoring. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 353, 131114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jung, B.Y.; Rayamahji, N.; Lee, H.S.; Jeon, W.J.; Choi, K.S.; Kweon, C.H.; Yoo, H.S. A multiplex real-time PCR for differential detection and quantification of Salmonella spp., Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Enteritidis in meats. J. Vet. Sci. 2009, 10, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awlqadr, F.H.; Altemimi, A.B.; Qadir, S.A.; Hama Salih, T.A.; Alkanan, Z.T.; AlKaisy, Q.H.; Mohammed, O.A.; Hesarinejad, M.A. Emerging trends in nano-sensors: A new frontier in food safety and quality assurance. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Lopez, F.J. Recent Progress in Micro- and Nanotechnology-Enabled Sensors for Biomedical and Environmental Challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, A.; Lopes, P.; Devlieghere, F.; Ragaert, P.; Vanfleteren, J.; Khashayar, P. Optimized packaging and storage strategies to improve immunosensors’ shelf-life. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 13122–13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikulnig, J.; Chang, S.; Bito, J.; Rauter, L.; Roshanghias, A.; Carrara, S.; Kosel, J. Printed electronics technologies for additive manufacturing of hybrid electronic sensor systems. Adv. Sens. Res. 2023, 2, 2300075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, S.; Benko, A. Advances in Fabricating the Electrospun Biopolymer-Based Biomaterials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Weng, W. Electrospun starch-based nanofiber mats for odor adsorption of oyster peptides: Recyclability and structural characterization. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Lopez, K.J.; Enescu, D.; Torres-Giner, S.; Cabedo, L.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Pastrana, L.; Fuciños, P.; Lagaron, J.M. Development of electrospun active films of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by the incorporation of cyclodextrin inclusion complexes containing oregano essential oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 108, 106013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.; Sun, X.; Zhou, L.; Du, H.; Zhu, Z.; Wen, Y. Electrospun pullulan/PVA nanofibers integrated with thymol-loaded porphyrin metal−organic framework for antibacterial food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanska, L.; Chiu, C.H.; Yeh, Y.C.; Chiang, W.D.; Hsieh, C.C.; Wang, R. Development of a PCL-PEO double network colorimetric pH sensor using electrospun fibers containing Hibiscus rosa sinensis extract and silver nanoparticles for food monitoring. Food Chem. 2022, 368, 130813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapstova, A.; Honzikova, P.; Dasek, M.; Ackermann, M.; Gergelitsova, K.; Erben, J.; Samkova, A.; Jirkovec, R.; Chvojka, J.; Horakova, J. Effective needleless electrospinning for the production of tubular scaffolds. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2024, 2, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, B.; Bruch, R.; Costa-Rama, E.; Fernández-Abedul, M.T.; Merkoçi, A.; Manz, A.; Urban, G.A.; Güder, F. Disposable Sensors in Diagnostics, Food, and Environmental Monitoring. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.F.; de Sousa Picciani, P.H.; Calado, V.; Tonon, R.V. Gelatin-based films and mats as electro-sensoactive layers for monitoring volatile compounds related to meat spoilage. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 36, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensing Mode | Mechanism/Feature |

|---|---|

| Optical | Detect variations in light intensity, wavelength, polarization, or decay characteristics caused by analyte interaction. Techniques such as fluorescence, phosphorescence, refraction, interference, and Raman scattering are commonly applied. Optical nanofiber sensors are valued for their high sensitivity, rapid response, and ability to enable real-time, non-destructive analysis. |

| Electrochemical | Operate by translating chemical or biochemical reactions into electrical signals (current, potential, or impedance). These platforms offer excellent sensitivity, low detection limits (often in the nanomolar to picomolar range), and cost-effective miniaturization. Widely applied in food safety and biomedical monitoring. |

| Fluorescent | Utilize fluorescent dyes, quantum dots, or fluorophore-tagged molecules that emit light upon excitation. Because of their high signal-to-noise ratio, such systems are ideal for detecting trace analytes or biomolecules even in complex media. |

| Colorimetric | Provide visible color transitions triggered by changes in pH, redox state, or volatile metabolite levels. The color shift serves as an immediate, on-site indicator of food freshness or environmental contamination without requiring external instrumentation. |

| Resistive | Measure alterations in electrical resistance or conductivity resulting from mechanical deformation, pressure, humidity, or gaseous exposure. These sensors are particularly suitable for strain, stress, and volatile organic compound (VOC) detection. |

| Photoelectric | Depend on the change in photo-induced current or voltage upon exposure to light or analytes that affect optical absorption. Commonly used for measuring material reflectance, transparency, or analyte-related optical variations. |

| Mass-Sensitive | Function through the adsorption of analytes on a piezoelectric or resonant surface, leading to measurable frequency or phase shifts. Quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) sensors are a typical example, allowing precise quantification of adsorbed mass. |

| Acoustic Wave | Rely on the modulation of surface or bulk acoustic waves when molecules interact with the sensor surface. The resulting frequency or phase shift correlates directly with analyte concentration, enabling sensitive gas or vapor detection. |

| Amperometric | Quantify the electric current generated during oxidation or reduction of electroactive species at the electrode interface. The measured current is proportional to analyte concentration, making this approach ideal for quantitative biosensing applications. |

| Nanofiber Composition | Sensor Type | Sensing Agent/Functional Element | Target Analyte or Freshness Marker | Application/Features | Detection Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA/PEI nanofibers + Ag NPs | SERS | AgNPs | Enrofloxacin (Prawn samples) | Sensitive antibiotic detection | LOD = ppb range | Chen et al., 2022 [28] |

| PLLA/Anthocyanin nanofibers | Colorimetric | Natural dye (anthocyanin) | Volatile amines in mutton | Color change pink → colorless; rapid response | Visual discrimination | Sun et al., 2021 [29] |

| Pullulan/Chitin nanofibers (anthocyanin + curcumin) | Colorimetric | Dual natural dyes | Volatile amines in fish | Differentiation of multiple spoilage stages | Visual discrimination | Duan et al., 2021 [51] |

| Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber mat with multiple pH-responsive dyes | Colorimetric sensor array (CSA) | Diverse pH-sensitive dyes integrated within PAN nanofiber mat | Volatile amines and total volatile base nitrogen (TVB-N) in fish | Freshness prediction using ML/DL models; 100% accuracy in classifying freshness stages | LOD = 0.14 ppm Rapid color response within 30 s | Zhang et al., 2026 [52] |

| Cellulose nanofibers (FITC + protoporphyrin IX) | Fluorescent (ratiometric) | Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and protoporphyrin IX | Biogenic amines (seafood) | Ratiometric fluorescence sensor; visual color change correlated with spoilage | LOD = 1 ppm | Quan et al., 2021 [53] |

| Polystyrene (PS)/NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+/Au@SiO2 nanofibers | Upconversion–plasmonic fluorescent | Upconversion nanorods (NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+) and plasmonic Au@SiO2 nanoparticles | Rhodamine B (model contaminant) | Enhanced fluorescence due to plasmon–exciton coupling; high sensitivity for trace contaminant detection | LOD = 0.01 ppm. Small amount of sample required (≈10 µL) | Li et al., 2019 [54] |

| PAN nanofiber + Au@Ag nanoparticles | SERS | Au@Ag plasmonic NPs | Thiabendazole (soy milk) | High reproducibility and sensitivity | LOQ ≈ 70 ppb | Hajikhani et al., 2024 [55] |

| PVA Nanofibers | SERS | AuNPs | Detection of doxycycline, enrofloxacin (chicken samples | Sensitive antibiotic detection | LOD = ppb range | Sarma et al. (2023) [56] |

| Zein/Ag nanoparticle nanofibers | SERS | AgNPs | Nitrite in cured meat | Reproducible enhancement and hotspot uniformity | LOD = ppb range | Zhang et al., 2023 [57] |

| Nanofiber Composition | Sensor Type | Recognition Element | Food Matrix | Contaminant/Target Analyte | Detection/Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrocellulose fibers | Conductometric lateral flow | Antibodies | Food samples | E. coli O157:H7, Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) | 64 CFU mL−1 (bacteria) 103 CCID mL−1 (Virus) | Luo et al., 2010 [6] |

| Cu-based MOF nanofibers (CuMOF) | Amperometric biosensor | Xanthine oxidase (XOD) | Squid, yellow croaker | Hypoxanthine/xanthine | LOD = 0.0023 μM and 0.0064 μM | Wang et al., 2019 [64] |

| Co-MOF/carbon nanofiber | Amperometric biosensor | Co(TMA)MOF catalyst | Salmon fillet | Xanthine, Uric acid | Xanthine: 96.2 nM; Uric acid: 103.5 nM | Ahmad et al., 2022 [71] |

| Carbon nanofibers | Chemiresistive biosensor | Salmonella-specific aptamer | Fresh beef | Salmonella | Rapid detection; LOD = 10 CFU mL−1 (5 min) | Thiha et al., 2018 [73] |

| Chitosan-carbon nanofiber + AuNPs | Voltammetric aptasensor | Aptamer | Milk | Salmonella | Rapid detection; 1.23 CFU mL−1 | Fathi et al., 2021 [74] |

| Nanofiber Composition | Sensor Type | Target Gases/Markers | Detection Principle | Application/ Remarks | Detection Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnO2 nanowires decorated with Ag and Pt nanoparticles | Resistive (electronic nose) | H2 and NH3 mixtures | MOS resistance modulation + metal semiconductor junction effects | Miniaturized array with five temperature-differentiated sensors | (LOD = 0.2–1.2 ppm) rapid response (25 s–5 min), and long-term stability (2 months) | Tonezzer et al., 2022 [81] |

| 3SiO2:In2O3 and SiO2:ZnO nanofiber mats | Resistive (E-nose) | Spoilage amines | Resistance variation | Differentiated fish freshness levels | Separating freshness stages over 0–48 h | Andre et al., 2022 [82] |

| SnO2, CuO, In2O3, ZnO nanofibers | Resistive (E-nose array) | VOCs (e.g., alcohols, amines, aldehydes) | MOS resistance change + PCA pattern recognition | Potential for meat spoilage monitoring | Discrimination of five VOCs (ammonia, ethanol, acetaldehyde, isoprene, and acetone) | Zang et al., 2023 [63] |

| NF Based Sensing Type | Nanofiber System/Composition | Detection Performance | Function or Benefit | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospinning used to fabricate the sensor element directly | FITC- and Rhodamine B–labeled chitosan nanofibers | Biogenic amines: 1 ppm | Dual-fluorescence colorimetric sensing of spoilage; visible response for seafood freshness monitoring. | [60] |

| PS-based upconversion–plasmonic nanofibers (NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ + Au@SiO2) | Enhanced fluorescence emission | Hybrid photoresponsive fibers with amplified luminescence for trace contaminant detection. | [54] | |

| Cu-based MOF nanofibers (XOD–CuMOF) | Hypoxanthine: 0.0023 µMXanthine: 0.0064 µM | Nanofibers act as the active sensing layer for seafood freshness; high electrocatalytic activity and rapid electron transfer. | [64] | |

| Electrospun fibers serving as a support platform for functional sensing components | Au@Ag-functionalized PAN nanofibers (SERS substrate) | Thiabendazole: ≈70 ppb (LOQ) | Hybrid plasmonic nanofiber support producing strong electromagnetic hot spots for ultrasensitive Raman detection. | [55] |

| Co-MOF/Carbon nanofibers | Xanthine: 96.2 nM Uric acid: 103.5 nM | Porous conductive CNF scaffold improves analyte adsorption, charge transfer, and catalytic efficiency. | [71] | |

| Carbon nanowire with Salmonella-specific aptamer | 10 CFU mL−1, detection in 5 min | Conductive NF network transduces aptamer–pathogen binding events into measurable resistance changes. | [73] | |

| UiO-66-NH2/MWCNT@rGONR aptasensor (on NF support) | Recoveries: 97.8–107.7%, RSD < 5% | MOF–carbon hybrid supported on nanofibers enhances surface area and conductivity for antibiotic (kanamycin) detection. | [77] |

| Sensor Type | Performance Level | Practical Use Scenario | Cost & Scalability | Environmental Friendliness | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric NF sensors | Moderate sensitivity; qualitative to semi-quantitative | Innovative packaging; low-tech visual monitoring | Very low cost; highly scalable | Contingent upon natural dyes, biodegradable polymers | Sun et al., 2021 [29] Hazarika et al., 2023 [49] Duan et al., 2021 [51] Zhang et al., 2026 [52] |

| Fluorescent NF sensors | High sensitivity; quantitative | Lab/on-device detection with optics | Medium cost; requires instrumentation | Contingent upon fluorophore stability (potential leaching) and biodegradability of polymers | Quan et al., 2021 [53] Wang et al., 2011 [60] Li et al., 2019 [54] |

| Electrochemical NF sensors | Excellent sensitivity and selectivity nanomolar–picomolar LOD | Portable food safety devices | Higher fabrication complexity | Contingent upon bioreceptors, additives and polymers. Metal oxides and noble-metal catalysts may increase environmental burden | Wang et al., 2019 [64] Ahmad et al., 2022 [71] Thiha et al., 2018 [73] Fathi et al., 2021 [74] |

| Resistive gas-sensing NF sensors | Rapid response and IoT capability | Spoilage gas monitoring inside packaging | Moderate; depends on MOS materials | Contingent upon materials. Metal oxides and noble-metal catalysts may increase environmental burden | Tonezzer et al., 2022 [81] Andre et al., 2022 [82] Zang et al., 2023 [63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramachandraiah, K.; Martin, E.M.; Limayem, A. Electrospun Nanofiber Platforms for Advanced Sensors in Livestock-Derived Food Quality and Safety Monitoring: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 6947. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226947

Ramachandraiah K, Martin EM, Limayem A. Electrospun Nanofiber Platforms for Advanced Sensors in Livestock-Derived Food Quality and Safety Monitoring: A Review. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6947. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226947

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamachandraiah, Karna, Elizabeth M. Martin, and Alya Limayem. 2025. "Electrospun Nanofiber Platforms for Advanced Sensors in Livestock-Derived Food Quality and Safety Monitoring: A Review" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6947. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226947

APA StyleRamachandraiah, K., Martin, E. M., & Limayem, A. (2025). Electrospun Nanofiber Platforms for Advanced Sensors in Livestock-Derived Food Quality and Safety Monitoring: A Review. Sensors, 25(22), 6947. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226947