Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection for Mineral Mining Applications Based on Attention Mechanism and Boundary Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

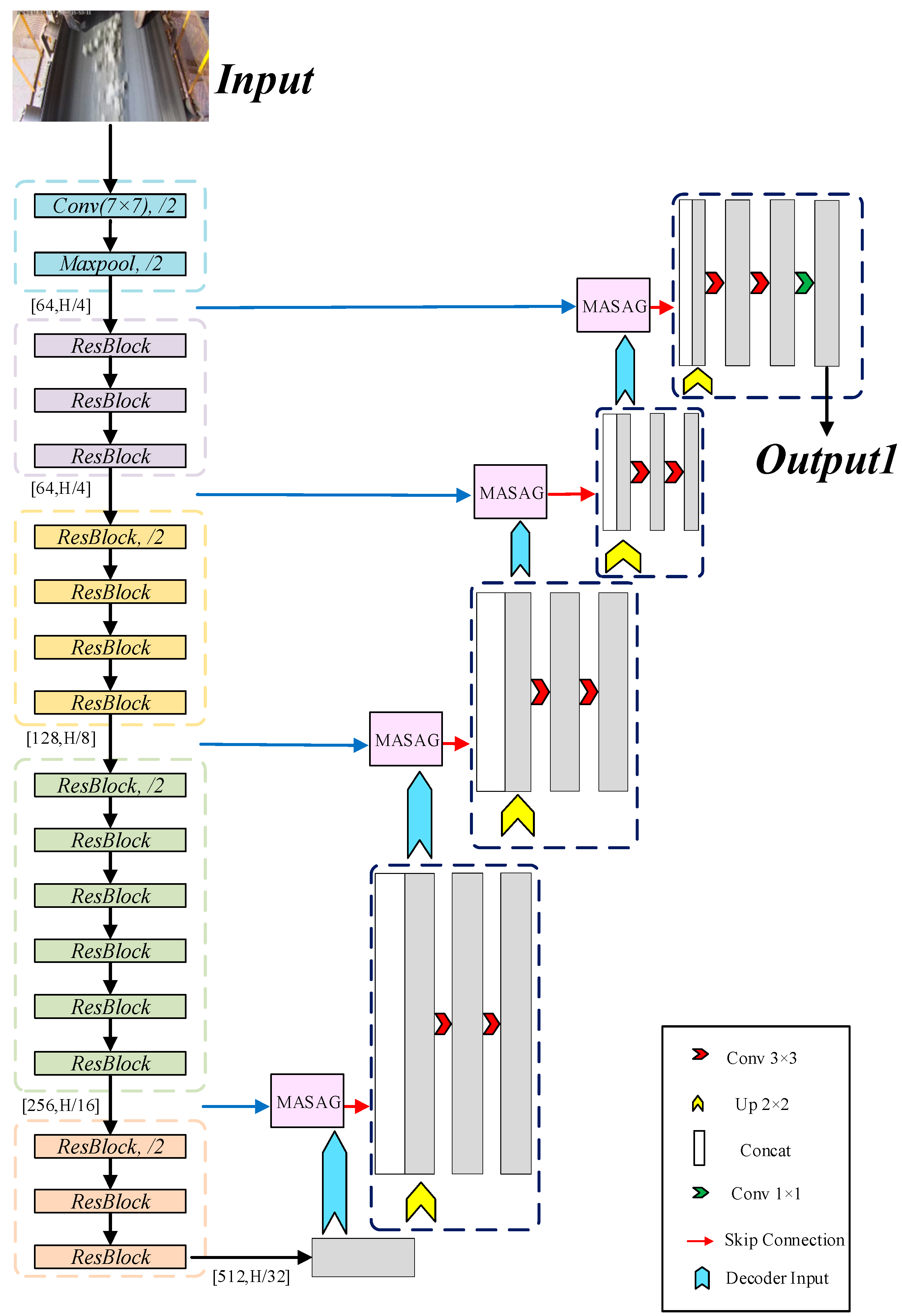

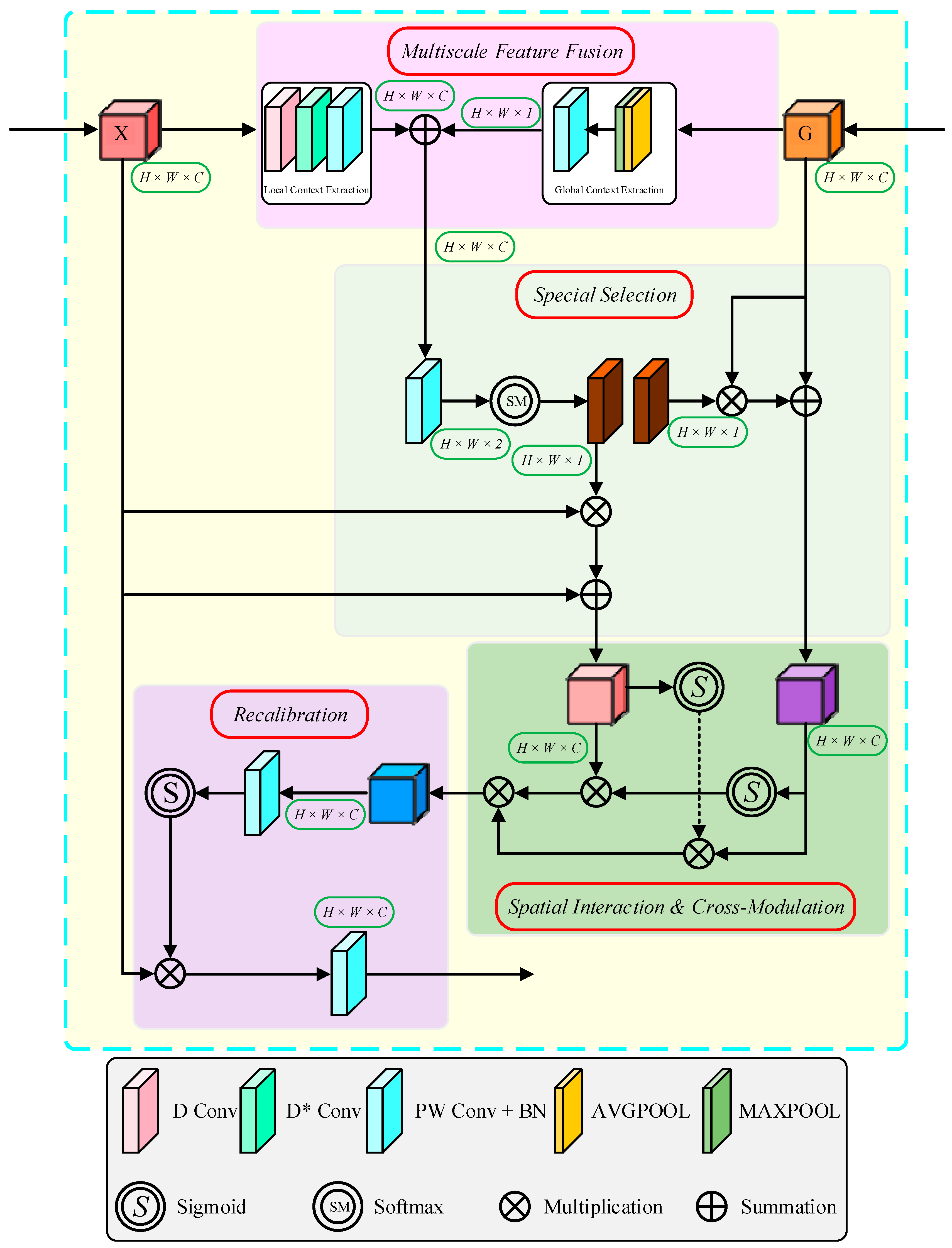

- Based on the existing Multi-scale Adaptive Guidance Attention (MASAG) mechanism, the structure is adapted to the conveyor belt deviation detection task and embedded into the skip connections of U-Net. This integration enhances the cross-scale fusion of semantic and edge features, thereby improving the model’s capability for accurate edge recognition under complex working conditions. Compared with SEU-Net, the proposed design achieves more effective boundary feature enhancement and yields superior edge segmentation performance.

- (2)

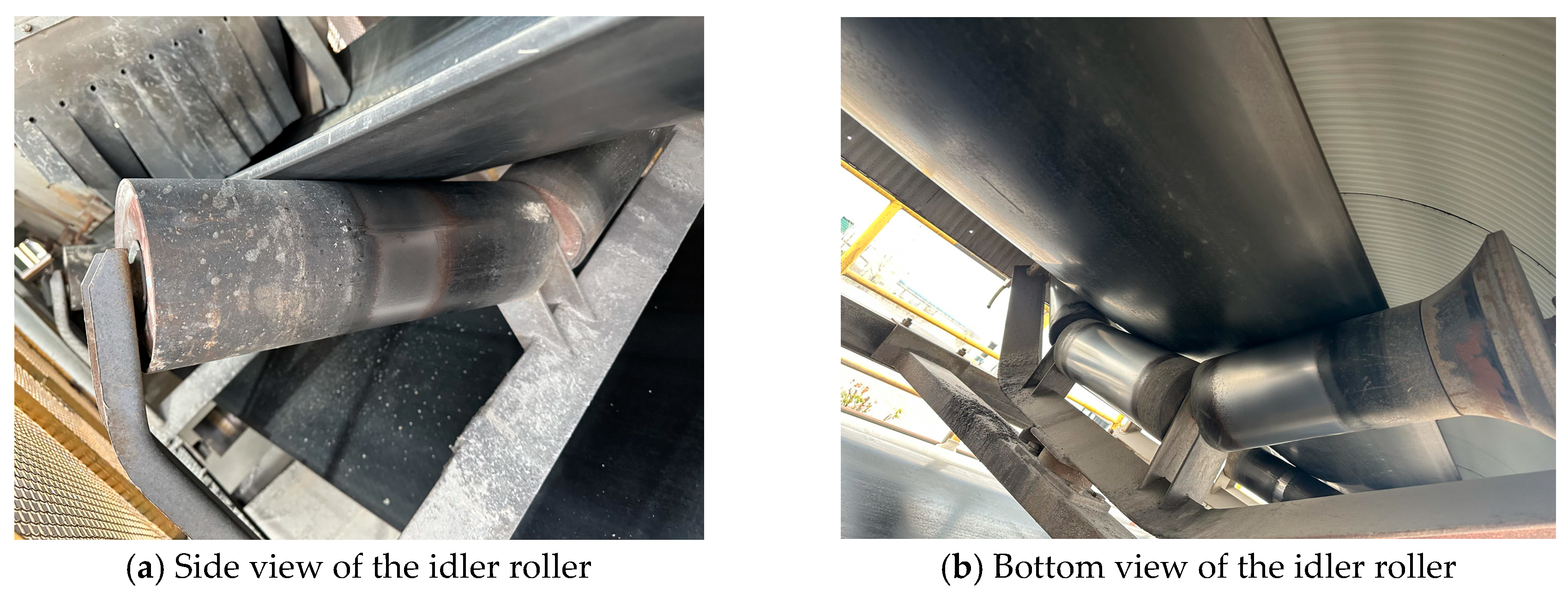

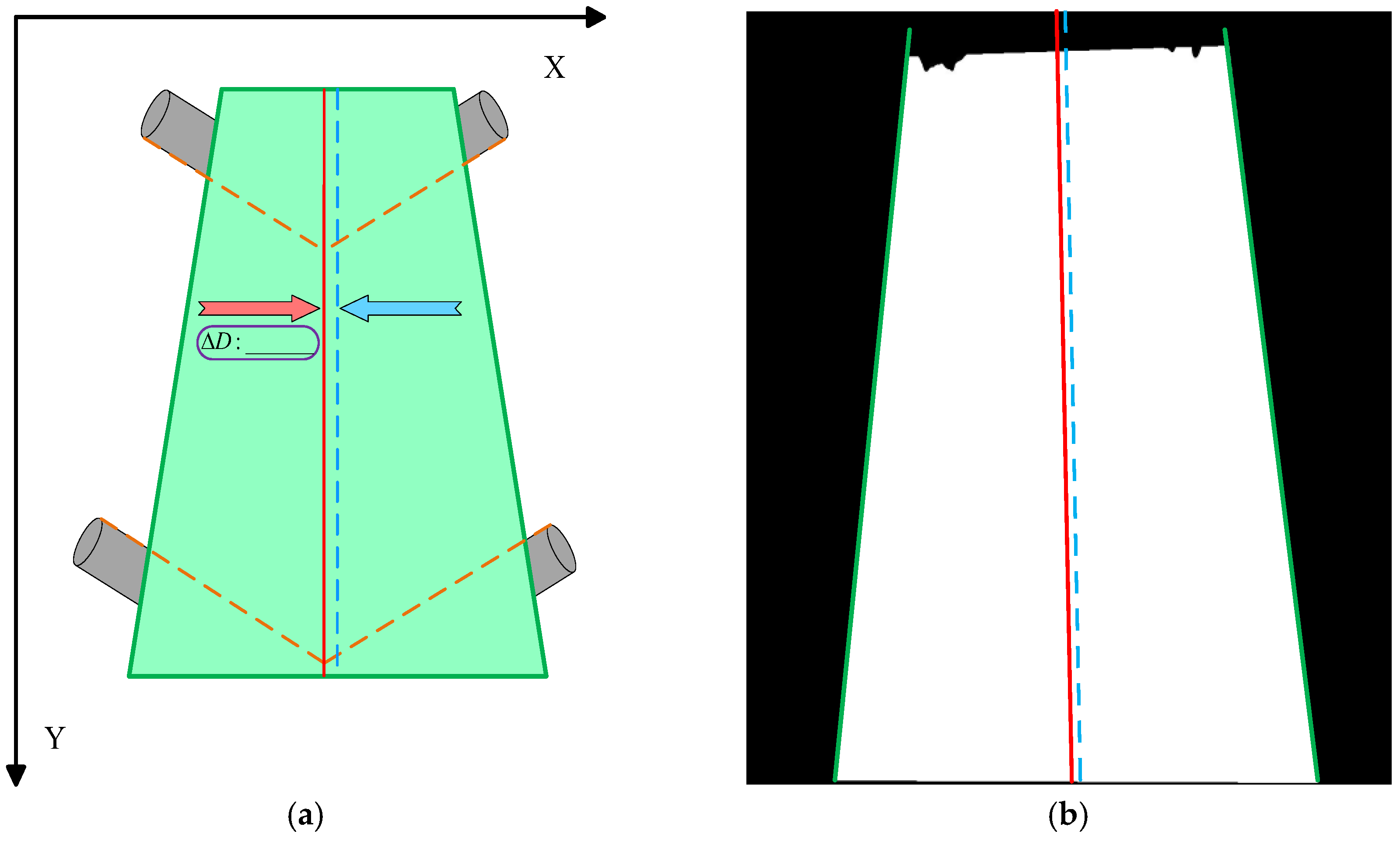

- A belt center localization method based on the physical stability of idler edges is developed, allowing for the quantitative analysis of deviation severity.

- (3)

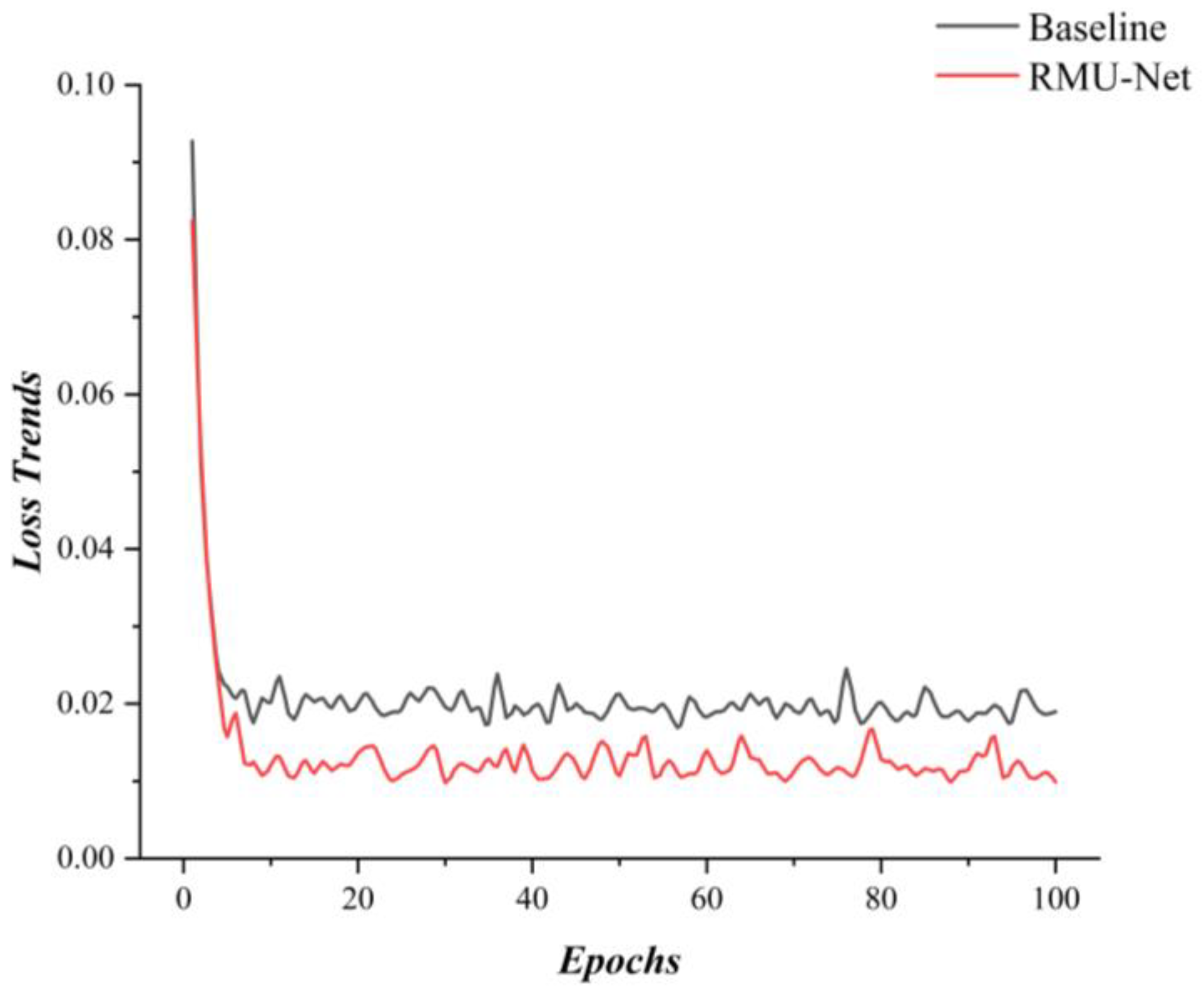

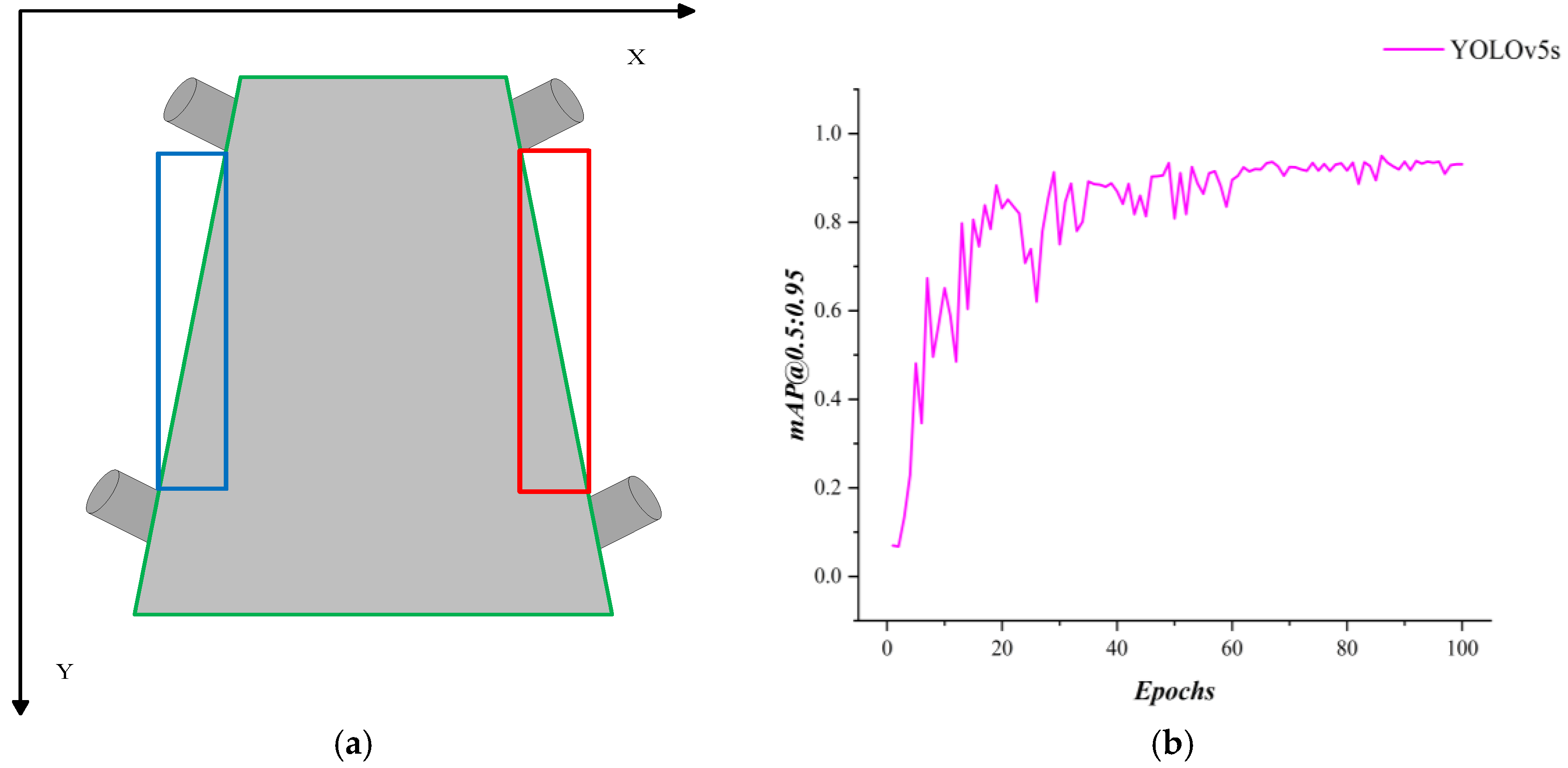

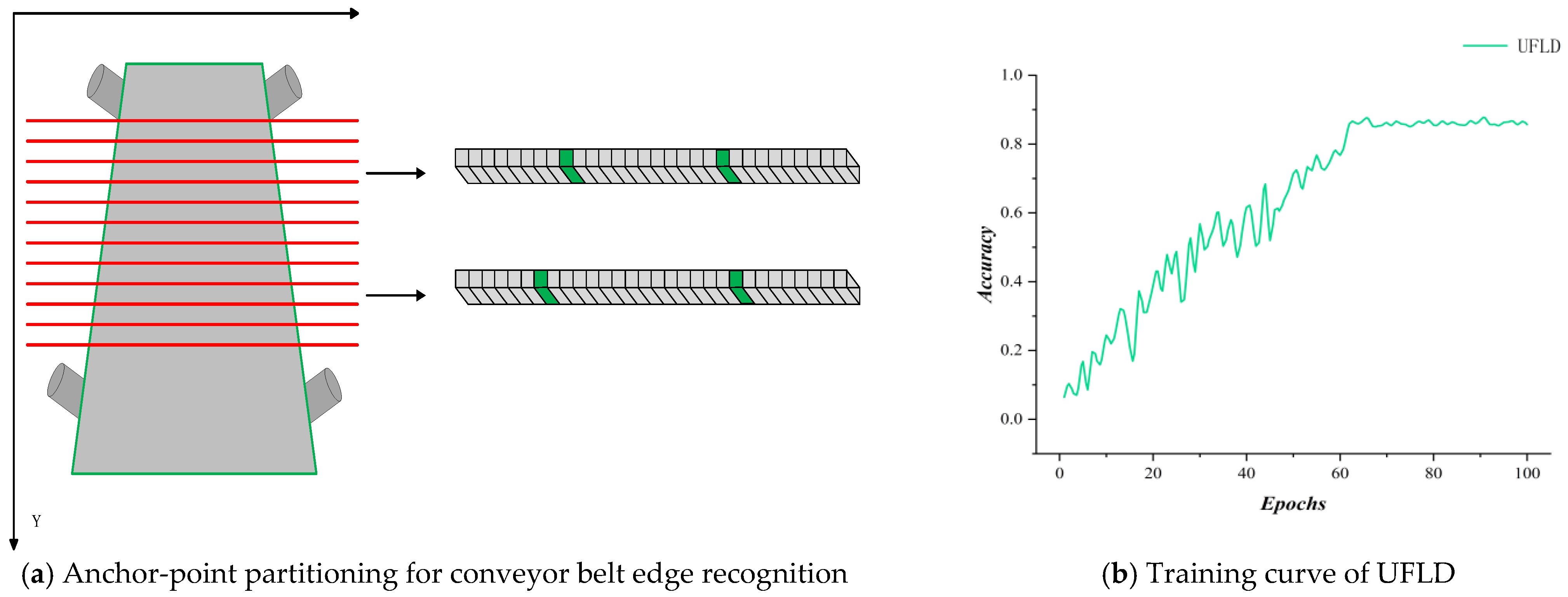

- A cross-method experimental validation strategy is employed: U-Net is used as the baseline model to verify improvements in segmentation accuracy, and comparative experiments are conducted with the object detection model YOLOv5s and the lane detection model UFLD [23], evaluating performance differences among different methodological approaches.

- (4)

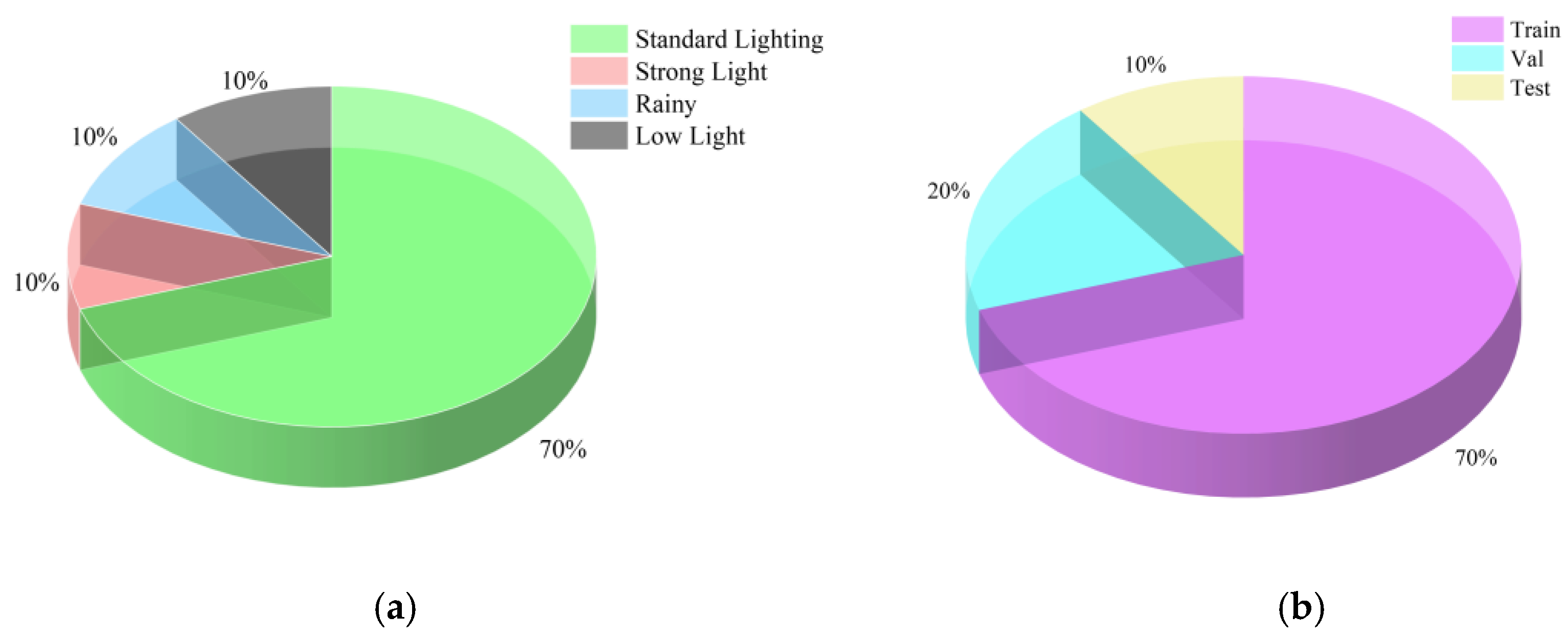

- A comprehensive dataset was constructed, covering multiple environmental conditions such as normal illumination, strong light, low light, and rainy weather. The dataset provides a reliable foundation for model training and performance evaluation under diverse real-world scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

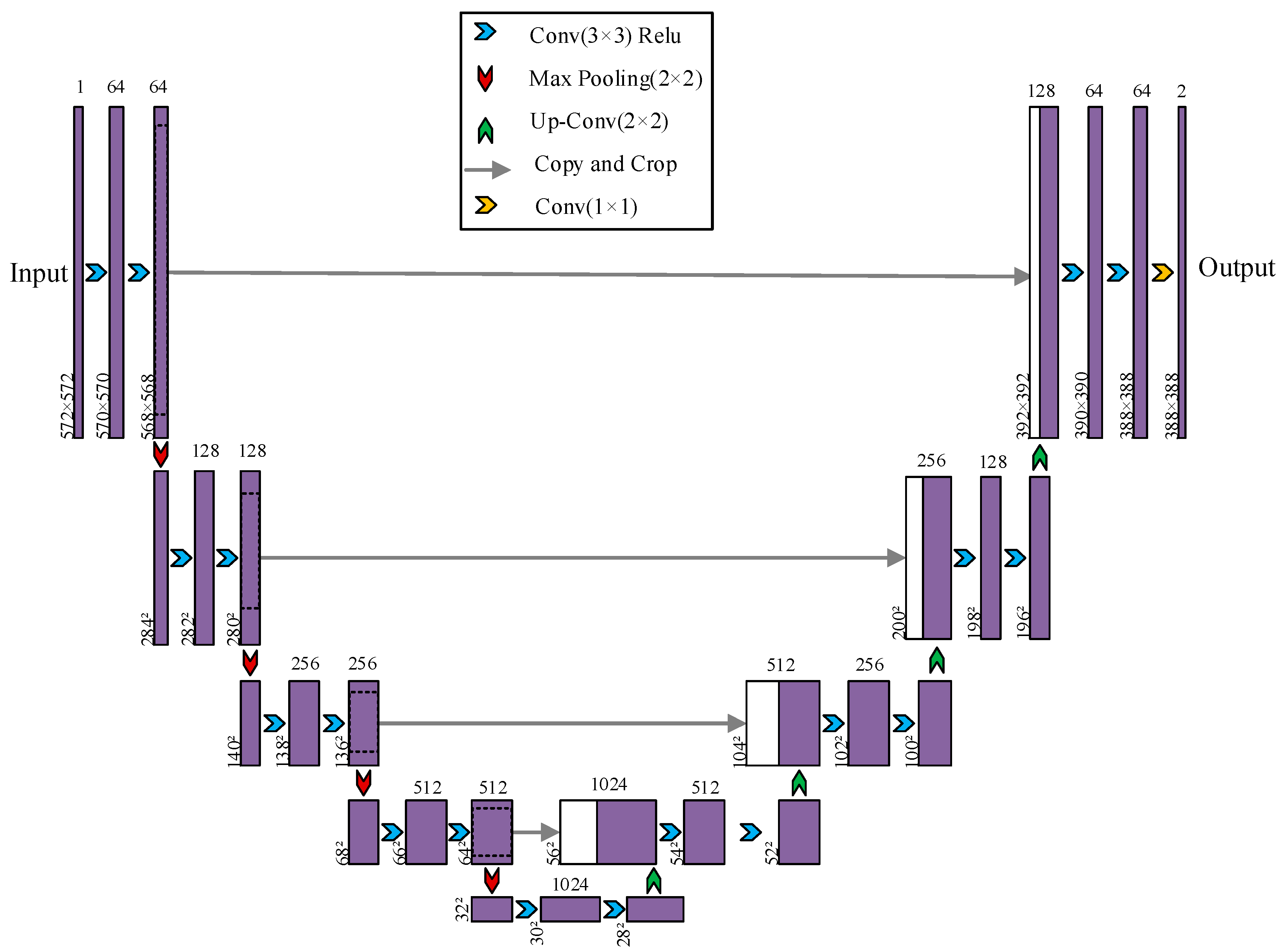

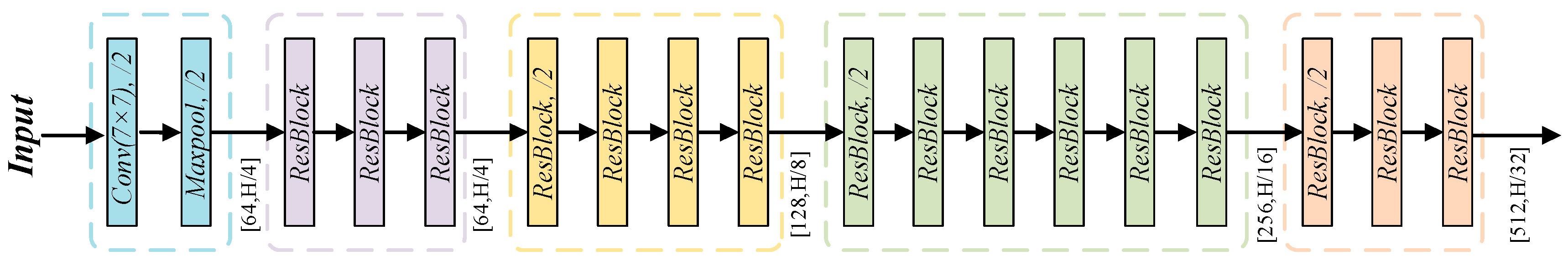

2.1. U-Net Network

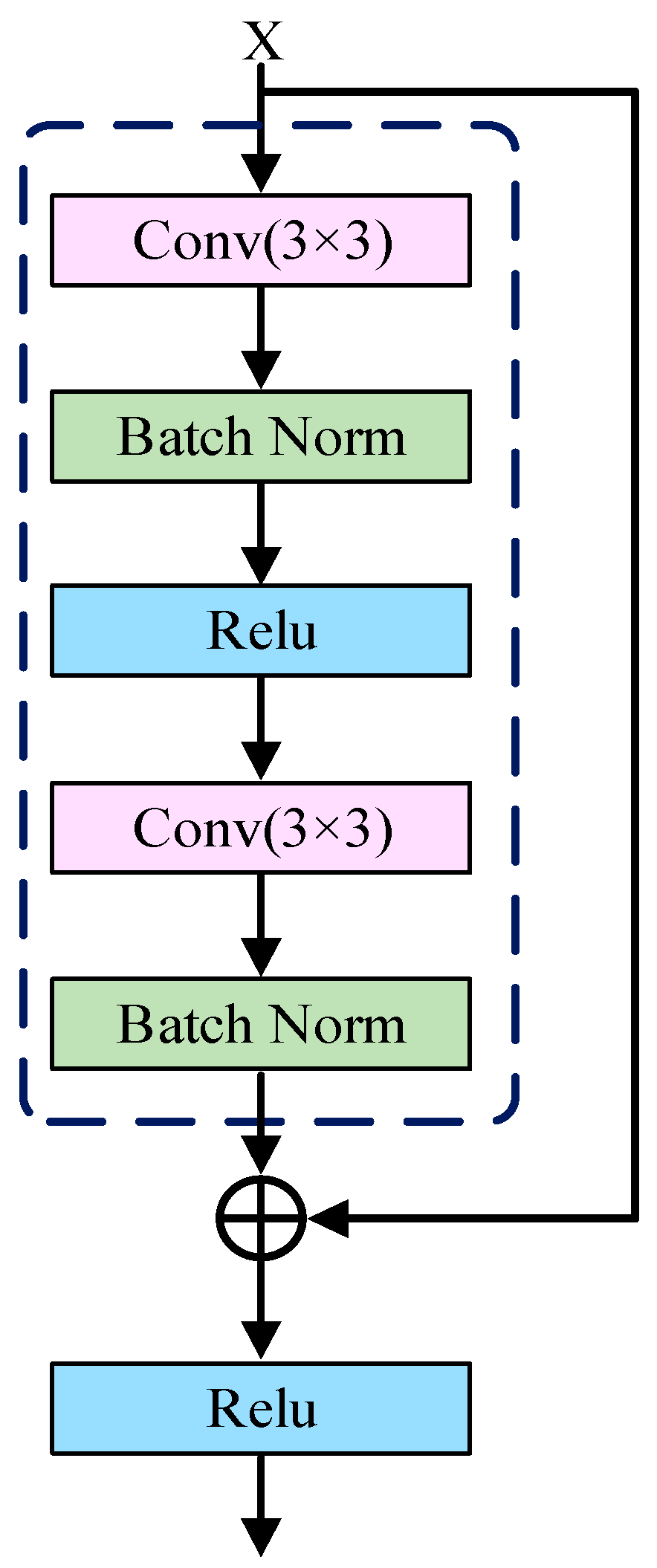

2.2. Improved U-Net Model

2.3. Region–Boundary Joint Loss Function Design

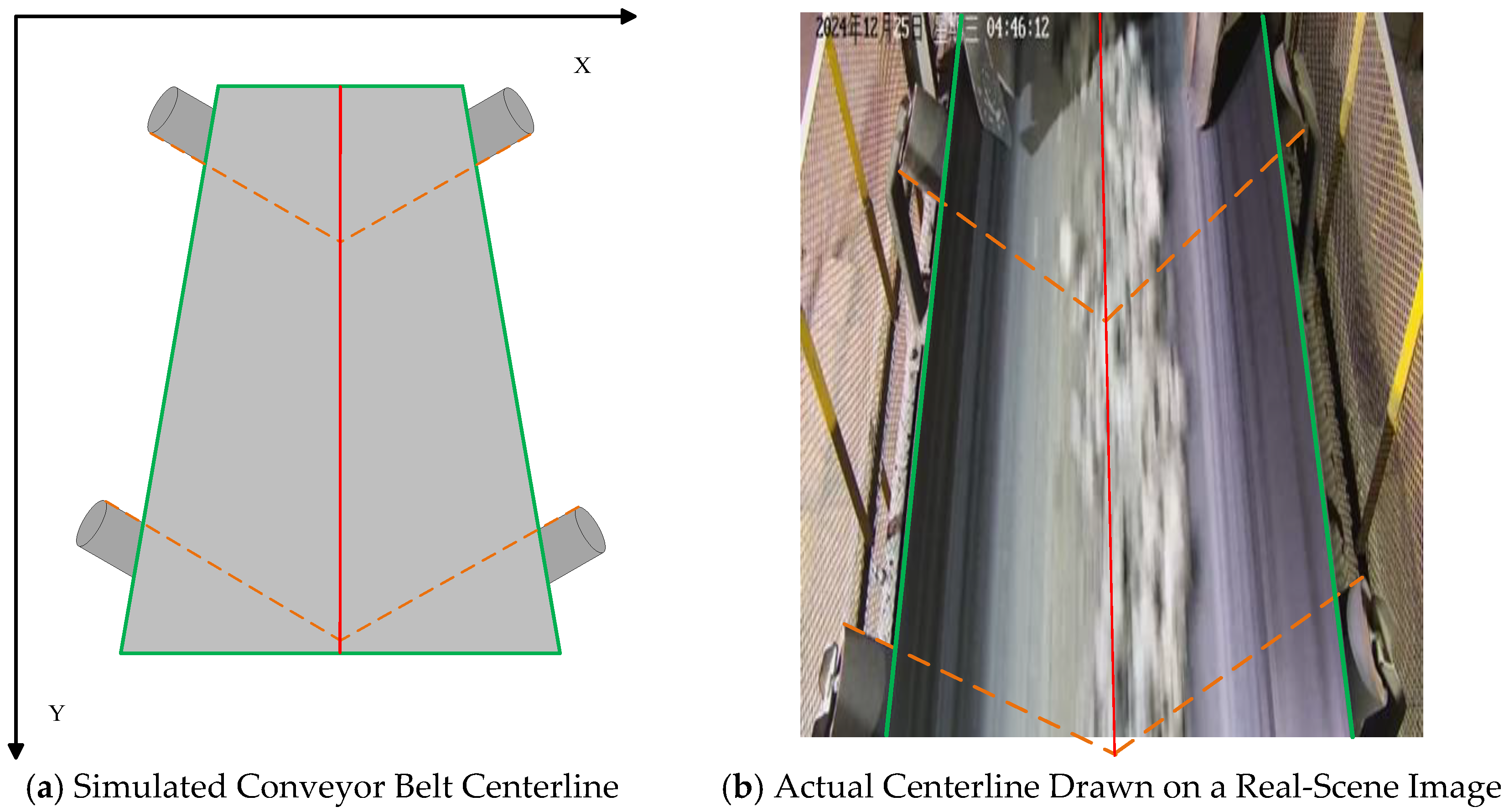

2.4. Precise Quantification Method for Conveyor Belt Deviation

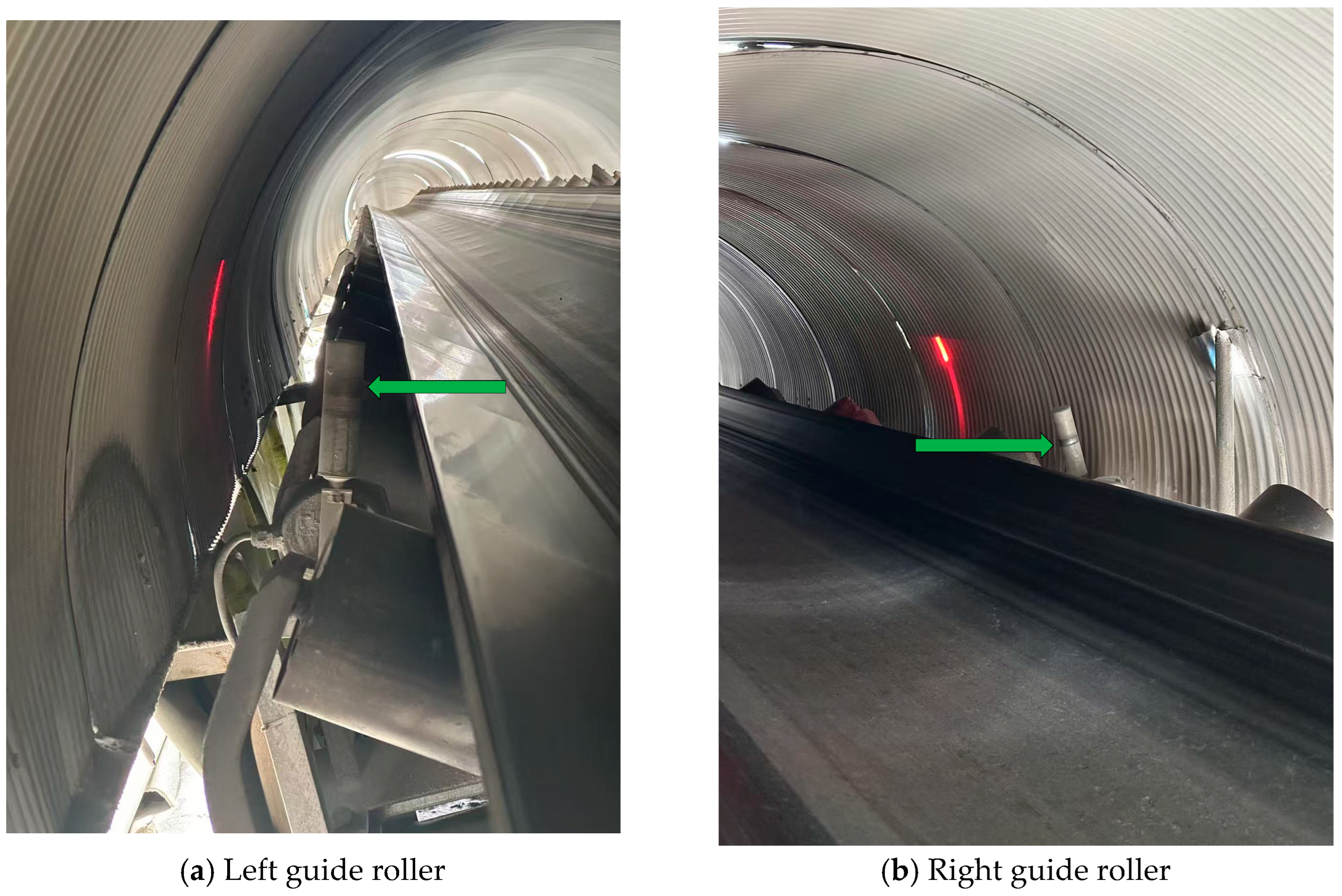

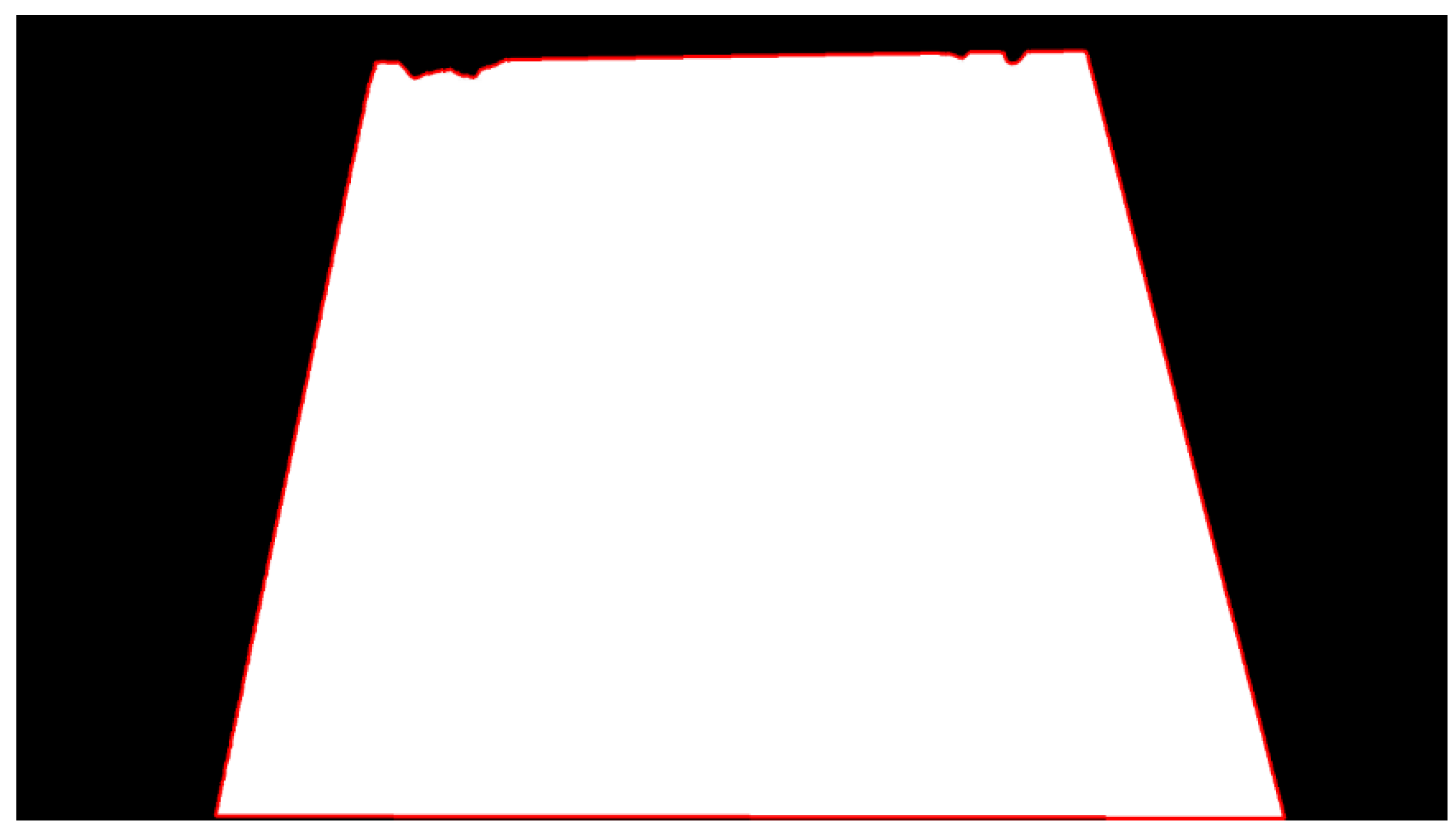

2.4.1. Reference Line Construction

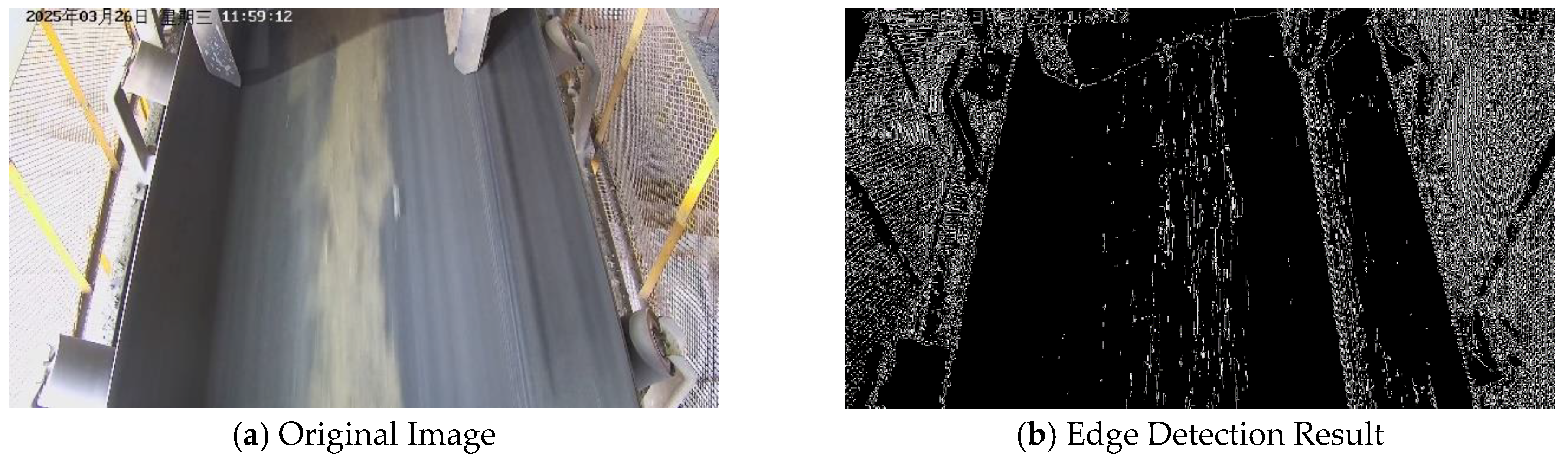

2.4.2. Edge Extraction and Conveyor Belt Boundary Fitting

3. Results

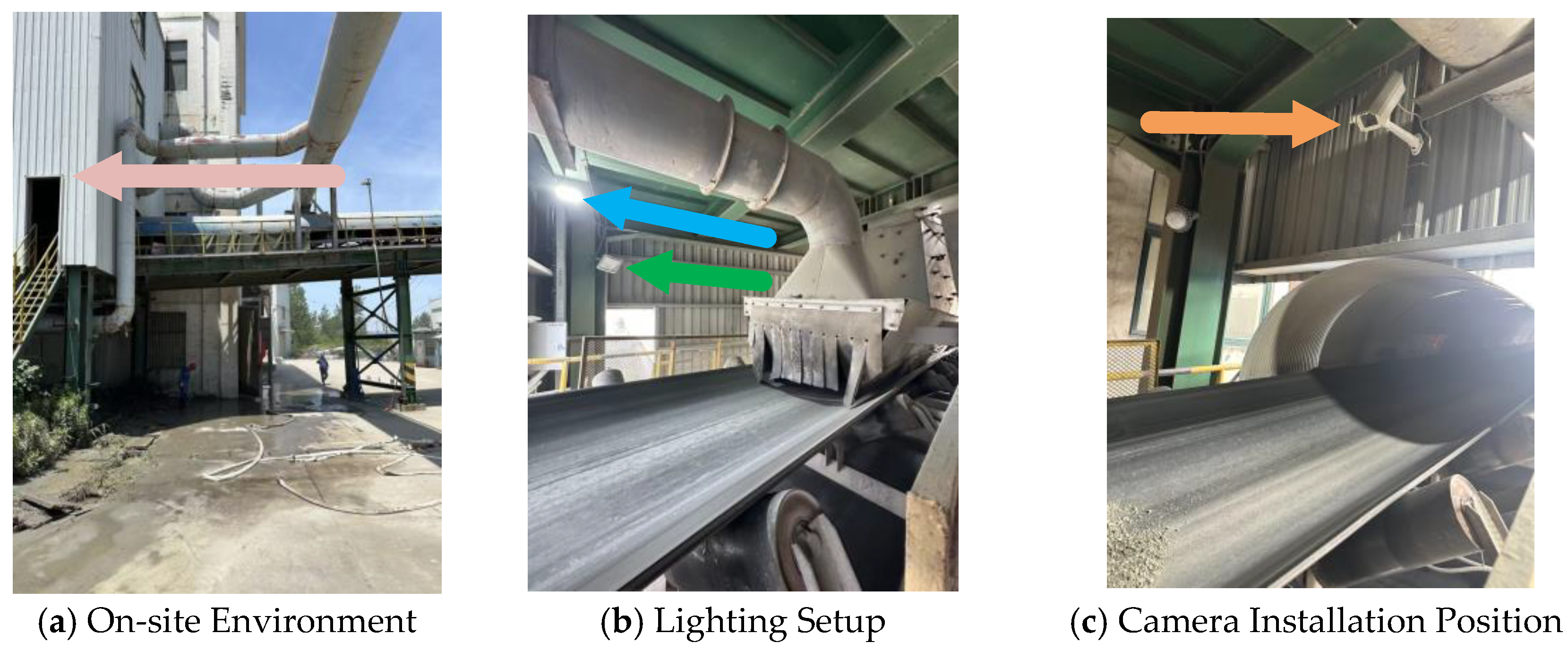

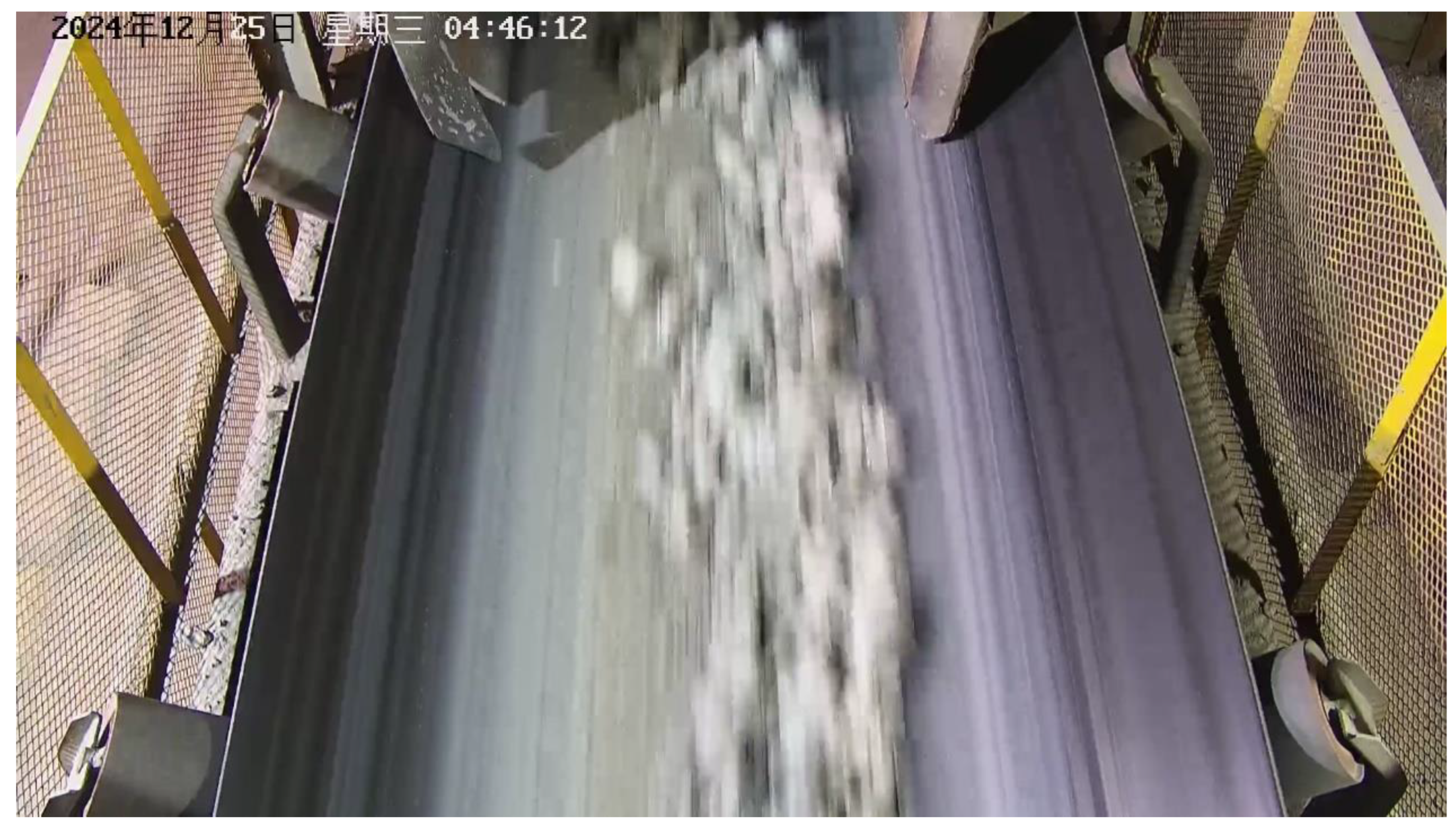

3.1. Dataset Construction and Hardware Environment

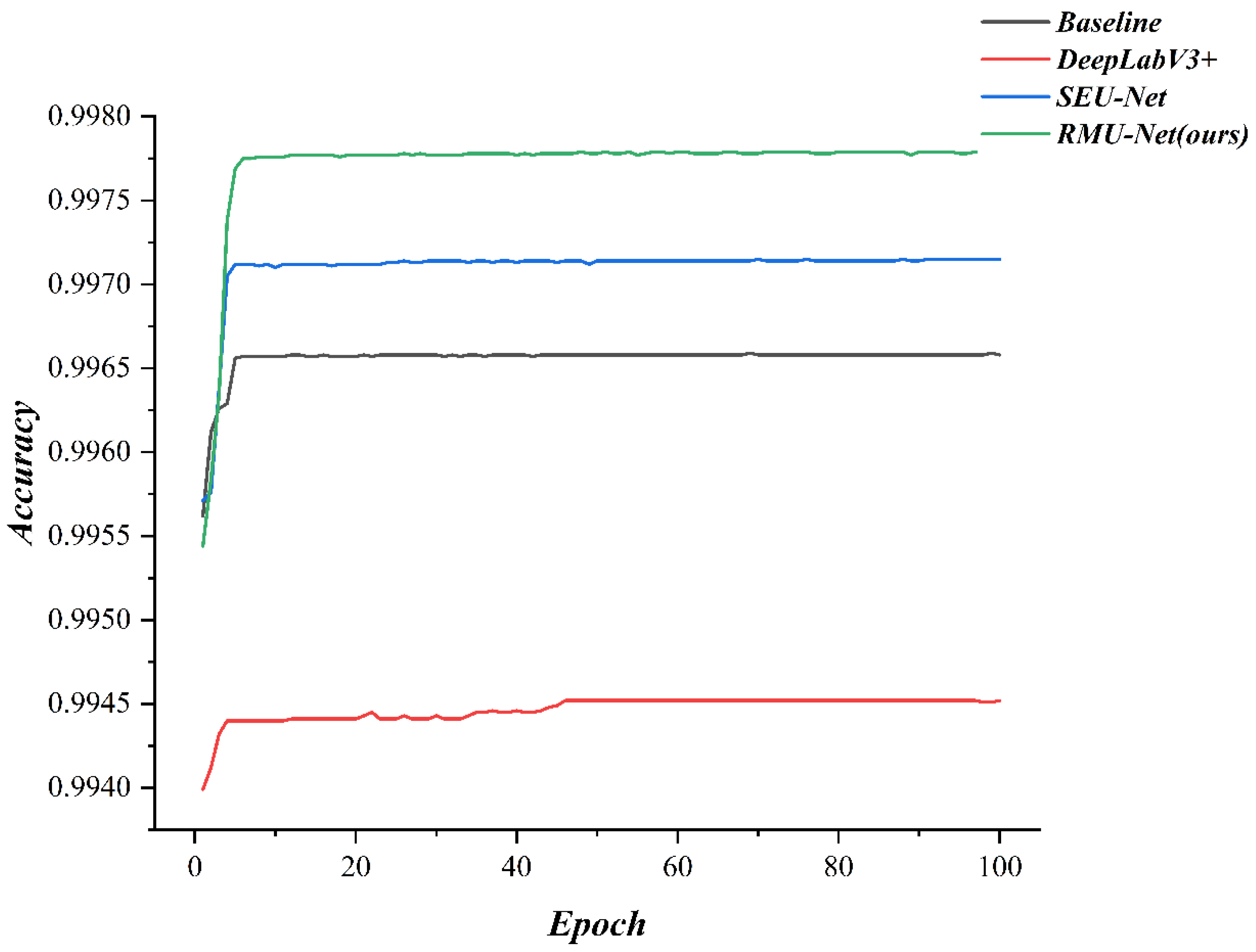

3.2. Ablation Study

3.3. Comparative Experiments

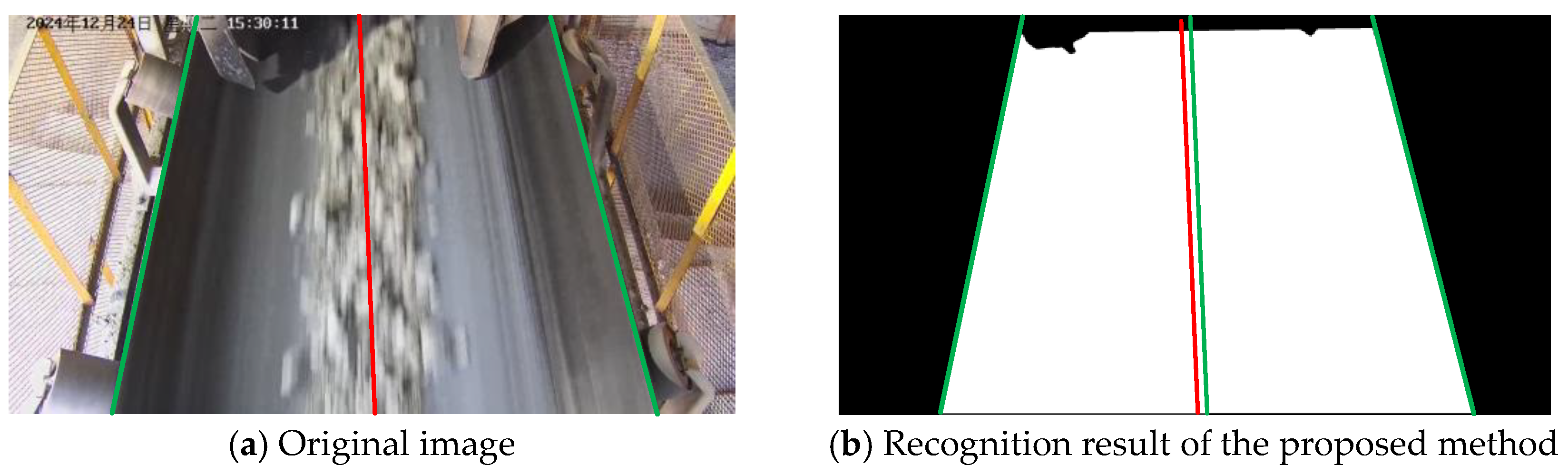

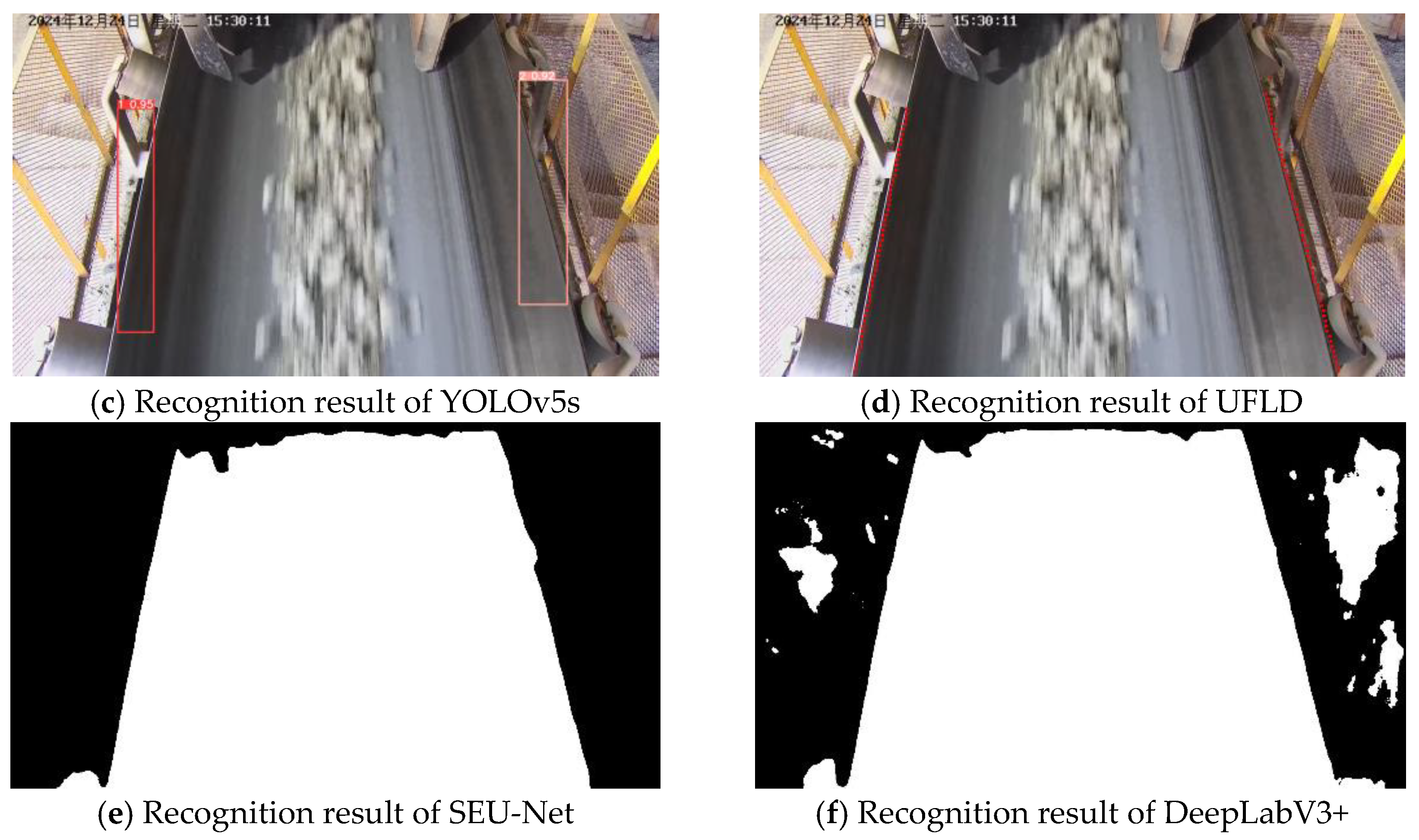

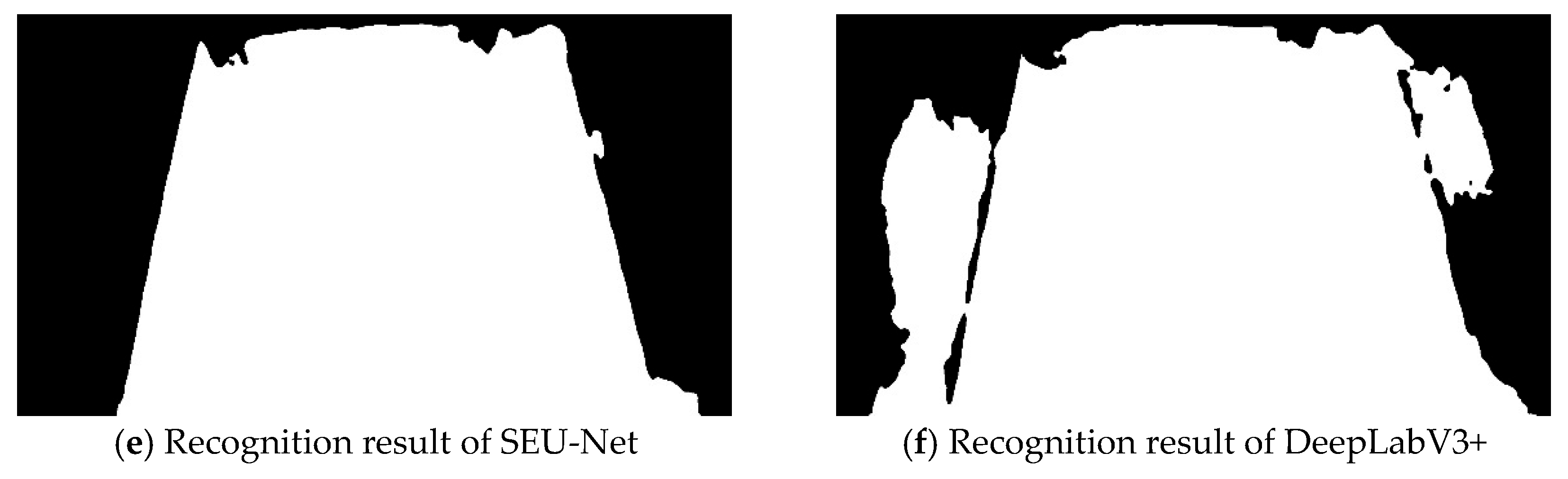

3.4. Visualization Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, H.; Xiao, D. A High-Precision and Lightweight Ore Particle Segmentation Network for Industrial Conveyor Belt. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 273, 126891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, H.; Fu, X.; Liu, M.; Qiao, H.; Ma, Y. Real-Time Belt Deviation Detection Method Based on Depth Edge Feature and Gradient Constraint. Sensors 2023, 23, 8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Fang, T.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, M.; Xu, J.; Ji, J.; He, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, M. Applications of Machine Vision Technology for Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection: A Review and Roadmap. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 161, 112312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski, P.; Kawalec, W.; Król, R.; Ozdoba, M. Types and Causes of Damage to the Conveyor Belt–Review, Classification and Mutual Relations. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Cheng, H.; Hou, Y.; Guo, P. Study of Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8 Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarini, R.; Khamayseh, F.; Awwad, Y.; Sabha, M.; Eleyan, D. Dynamic Generative R-CNN. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 7107–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, R.; Li, X.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.-M. YOLO-MS: Rethinking Multi-Scale Representation Learning for Real-Time Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 4240–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Wu, H.; Xu, Z.; Xia, J. Multi-Object Garbage Image Detection Algorithm Based on SP-SSD. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 263, 125773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, J.; Bo, Y.; Wang, J. ISTD-DETR: A Deep Learning Algorithm Based on DETR and Super-Resolution for Infrared Small Target Detection. Neurocomputing 2025, 621, 129289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.A.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Shoukat, M.U.; Bhatti, U.A.; Raza, M.A. Medical Image Zero Watermarking Algorithm Based on Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform, AlexNet and Discrete Cosine Transform. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 169, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Prabhu, R.; Yadav, M.; Feng, W.-C.; Cao, G. Improved 2-D Chest CT Image Enhancement with Multi-Level VGG Loss. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2025, 9, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, K.; Khan, M.A.; Hamza, A.; Albarakati, H.M.; Alsenan, S.; Tariq, U.; Ofori, I. An EfficientNet Integrated ResNet Deep Network and Explainable AI for Breast Lesion Classification from Ultrasound Images. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2025, 10, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, H.; Xu, B.; Zhu, Z. Intelligent Prediction Model for Pitting Corrosion Risk in Pipelines Using Developed ResNet and Feature Reconstruction with Interpretability Analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264, 111347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Shouno, H.; Mohammed, M.A.; Marhoon, H.A.; Alam, T. DCSSGA-UNet: Biomedical Image Segmentation with DenseNet Channel Spatial and Semantic Guidance Attention. Knowl. Based Syst. 2025, 314, 113233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, Y.; Qin, S.; Chukkol, A.H.A.; Yusuf, A.A.; Bello, I.; Lawan, A. Exploring the Synergies of Hybrid Convolutional Neural Network and Vision Transformer Architectures for Computer Vision: A Survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Xin, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J. Dynamic Response Recovery of Damaged Structures Using Residual Learning Enhanced Fully Convolutional Network. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2025, 25, 2550008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munia, A.A.; Abdar, M.; Hasan, M.; Jalali, M.S.; Banerjee, B.; Khosravi, A.; Hossain, I.; Fu, H.; Frangi, A.F. Attention-Guided Hierarchical Fusion U-Net for Uncertainty-Driven Medical Image Segmentation. Inf. Fusion 2025, 115, 102719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wan, T.; Zhang, Q. SEGNet: Shot-Flexible Exposure-Guided Image Reconstruction Network. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 11491–11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Huang, W.; Pan, F.; Wang, H.; Yan, C.; Ye, R.; Weng, S.; Cai, J.; Li, Y. Predicting Microvascular Invasion and Early Recurrence in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Using DeepLab V3+ Segmentation of Multiregional MR Habitat Images. Acad. Radiol. 2025, 32, 3342–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Cui, R.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Q.; Ping, L.; Zhou, H.; Gao, J.; Fang, C.; Han, X.; Hua, S. Deep Learning HRNet FCN for Blood Vessel Identification in Laparoscopic Pancreatic Surgery. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, K.; Liu, X.; Mu, J.; Zhao, X. Partial Convolution-Simple Attention Mechanism-SegFormer: An Accurate and Robust Model for Landslide Identification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 151, 110612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, B.; Qin, X.; Liu, L.; Jia, J. Label-Fusion Progressive Segmentation of Ore and Rock Particles in Complex Illumination Conditions Based on SAM-Mask2Former. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 297, 129300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Luo, C. Towards Real-Time and Robust Lane Detection: A DCN–EMCAM Empowered UFLD Model. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 025295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, Q. Weakly-Supervised Semantic Segmentation with Image-Level Labels: From Traditional Models to Foundation Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, S.G.; Chaharsooghi, S.K.; Khatibi, T.; Bozorgpour, A.; Azad, R.; Heidari, M.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Merhof, D. MSA2Net: Multi-Scale Adaptive Attention-Guided Network for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21640. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Granato, D.; Wang, K.; Hao, S.; Xuan, H. Detecting the Authenticity of Two Monofloral Honeys Based on the Canny-GoogLeNet Deep Learning Network Combined with Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2025, 485, 144509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, P.; Yan, S.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. RANSAC Back to SOTA: A Two-Stage Consensus Filtering for Real-Time 3D Registration. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 11881–11888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, B.; Liu, B.; Peng, C. Milling Cutter Wear State Identification Method Based on Improved ResNet-34 Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Wen, Q.; Tang, R.; Qin, Y. DG-Softmax: A New Domain Generalization Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Method for Planetary Gearboxes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 260, 111057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, B.M.; Mc Carthy, C.E.; Bhayana, R.; Krishna, S. Sigmoid Volvulus—Can CT Features Predict Outcomes and Recurrence? Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zhu, X.; Shi, W.; Qin, Q.; Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, L.; Ding, R.; Gan, L.; Yin, X. Manipulating the Coordination Dice: Alkali Metals Directed Synthesis of Co-NC Catalysts with CoN4 Sites. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, X.; Shi, H.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhao, G.; Lei, Z. Global Cross-Entropy Loss for Deep Face Recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 1672–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Training Metric | Value | Validation Metric | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epochs | 100 | Betas | 0.9, 0.999 |

| Batch Size | 4 | Optimizer | AdamW |

| Weight Decay | 0.0001 | Learning Rate | 0.0005 |

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows 10 Professional |

| Experimental Framework | Python 3.9.21/PyTorch 2.7.1 |

| CPU | 14th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-14900 |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5070 |

| RAM | 32 G |

| Baseline | ResNet | MASAG | Loss(CE + Dice) | Loss(CE + Dice + Boundary) | Accuracy(%) | IoU(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| √ | √ | 99.655 | 99.403 | |||

| √ | √ | 99.758 | 99.516 | |||

| √ | √ | 99.762 | 99.521 | |||

| √ | √ | √ | 99.768 | 99.530 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 99.778 | 99.538 |

| Model | Category | Accuracy (%) | FPS | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Segmentation | 99.655 | 20 | 226.80 |

| DeepLabV3+ | Segmentation | 99.452 | 12 | 378.72 |

| SEU-Net | Segmentation | 99.715 | 18 | 252.62 |

| YOLOv5s | Object Detection | 93.105 | 56 | 81.36 |

| UFLD | The Lane Detection | 85.121 | 50 | 90.72 |

| Ours | Segmentation | 99.778 | 16 | 283.87 |

| Environmental Condition | Number of Images | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Normal lighting conditions | 1000 | 25.82 |

| Strong light interference | 500 | 26.71 |

| Rainy environments | 500 | 28.56 |

| Low-light conditions | 500 | 27.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Han, J.; Dong, C.; Fang, T.; Liu, W.; He, X. Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection for Mineral Mining Applications Based on Attention Mechanism and Boundary Constraints. Sensors 2025, 25, 6945. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226945

Ma L, Han J, Dong C, Fang T, Liu W, He X. Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection for Mineral Mining Applications Based on Attention Mechanism and Boundary Constraints. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6945. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226945

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Long, Jiaming Han, Chong Dong, Ting Fang, Wensheng Liu, and Xianhua He. 2025. "Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection for Mineral Mining Applications Based on Attention Mechanism and Boundary Constraints" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6945. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226945

APA StyleMa, L., Han, J., Dong, C., Fang, T., Liu, W., & He, X. (2025). Conveyor Belt Deviation Detection for Mineral Mining Applications Based on Attention Mechanism and Boundary Constraints. Sensors, 25(22), 6945. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226945