Preview Control of a Semi-Active Suspension System Supplemented by an Active Aerodynamic Surface

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Work

1.3. Objectives

- To synthesize and simulate the state-space model of a semi-active suspension system combined with an active aerodynamic control surface to enhance passenger ride comfort and the total performance criterion without compromising on the road holding.

- To design an optimal preview control system in conjunction with an AAS that comprises feedback and feedforward parts to take anticipatory action ahead of time, thereby minimizing the effect of external disturbances on the suspension system.

- To evaluate the performance of the proposed model by comparing it with other suspensions and to carry out a robust comparative analysis of the target suspension metrics in both the time and frequency domains.

- To perform computational analyses while keeping the suspension travel requirements and the passivity constraints of the SASS within the prescribed limits.

2. Vehicle Analysis Model

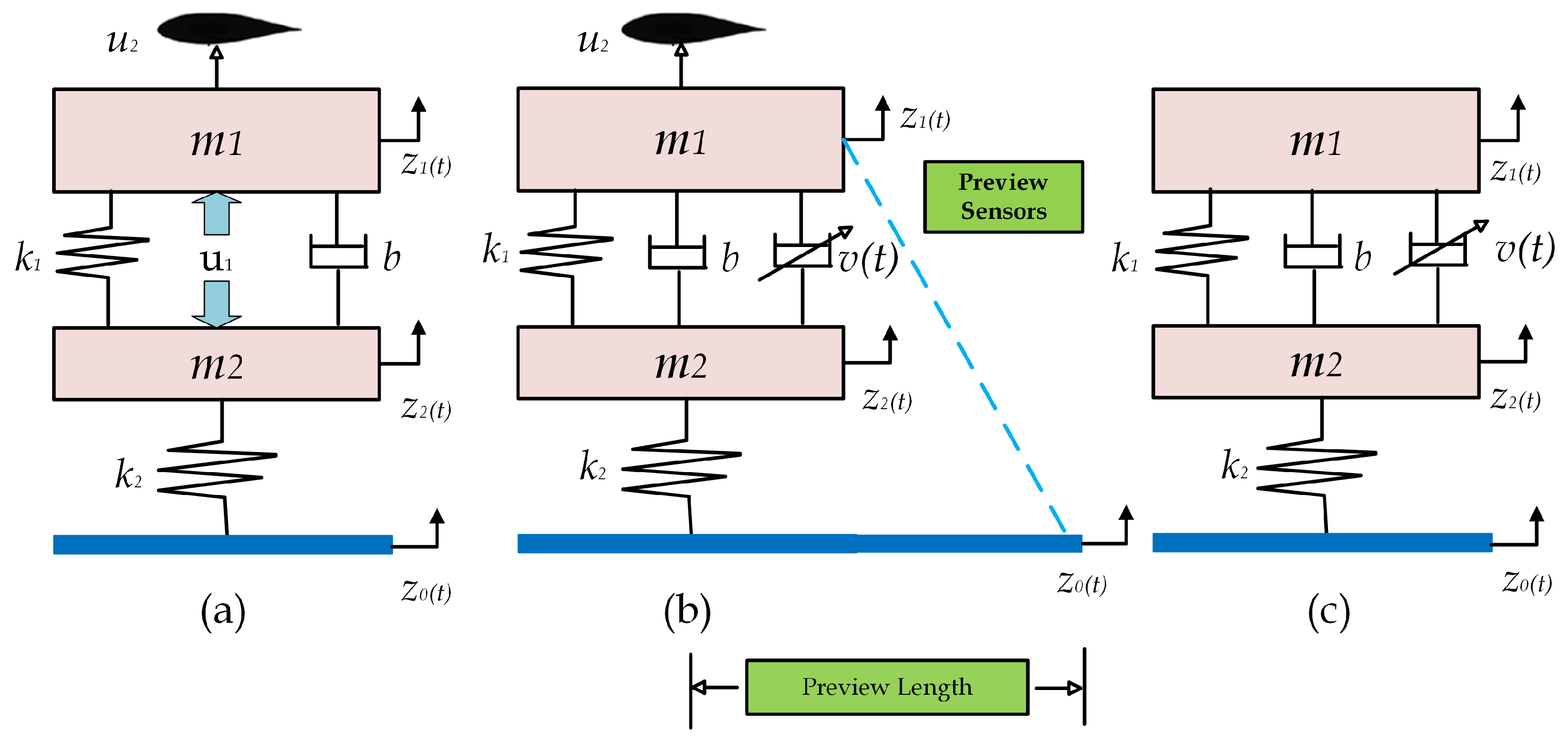

2.1. Quarter Car with Semi-Active Suspension

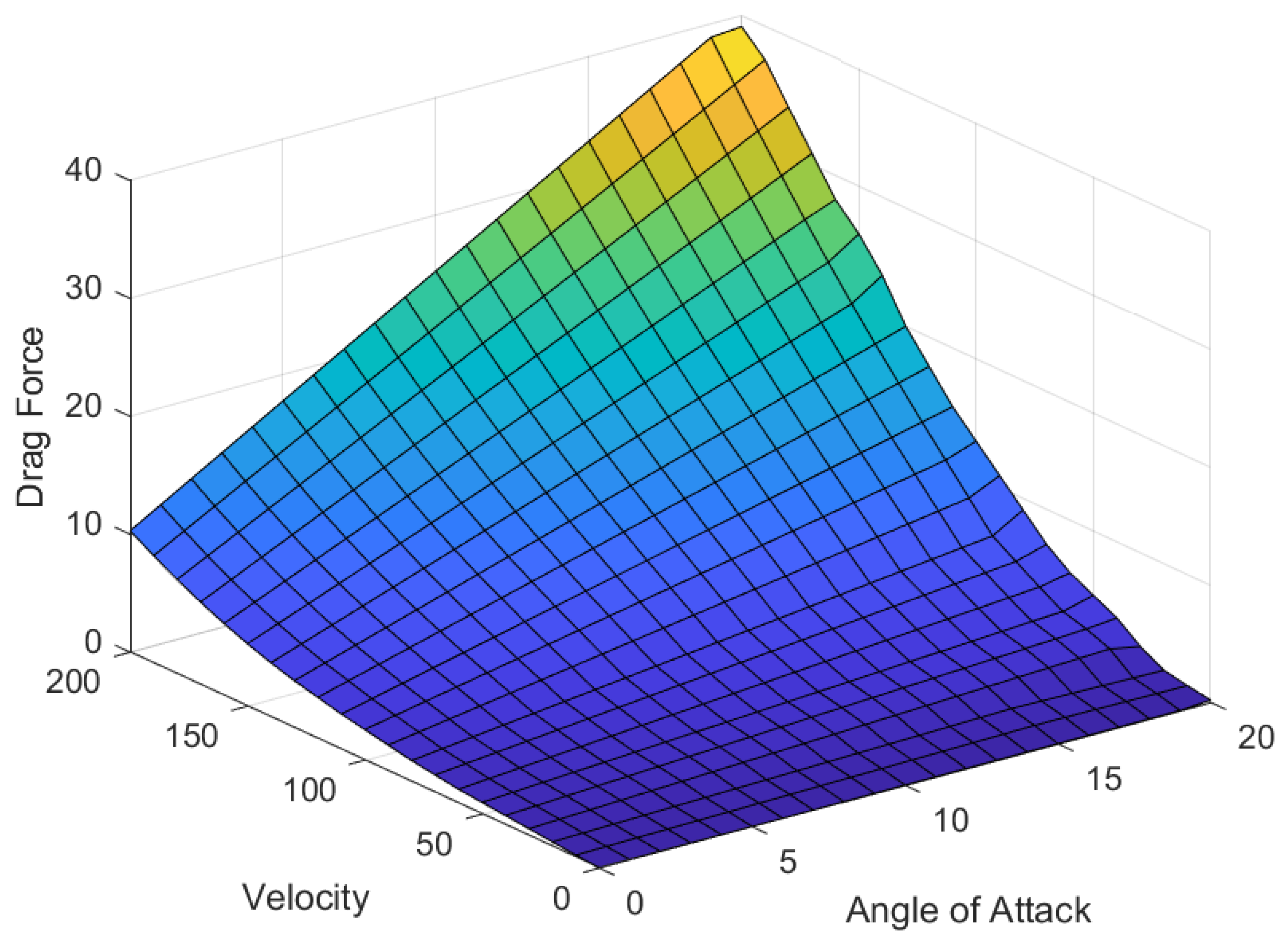

2.2. Active Aerodynamic Control Surface

2.3. Road Preview Information

3. Problem Formulation

- The nonlinear dynamics of the actuator force and airfoil are neglected.

- For the given speed and road conditions, the horizontal drag force is neglected.

- Since our analysis is mainly related to the attenuation of external road-induced disturbances, the analysis will focus on the attenuation of these disturbances.

4. Design of Optimal Preview Controller

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Frequency-Domain Numerical Simulation

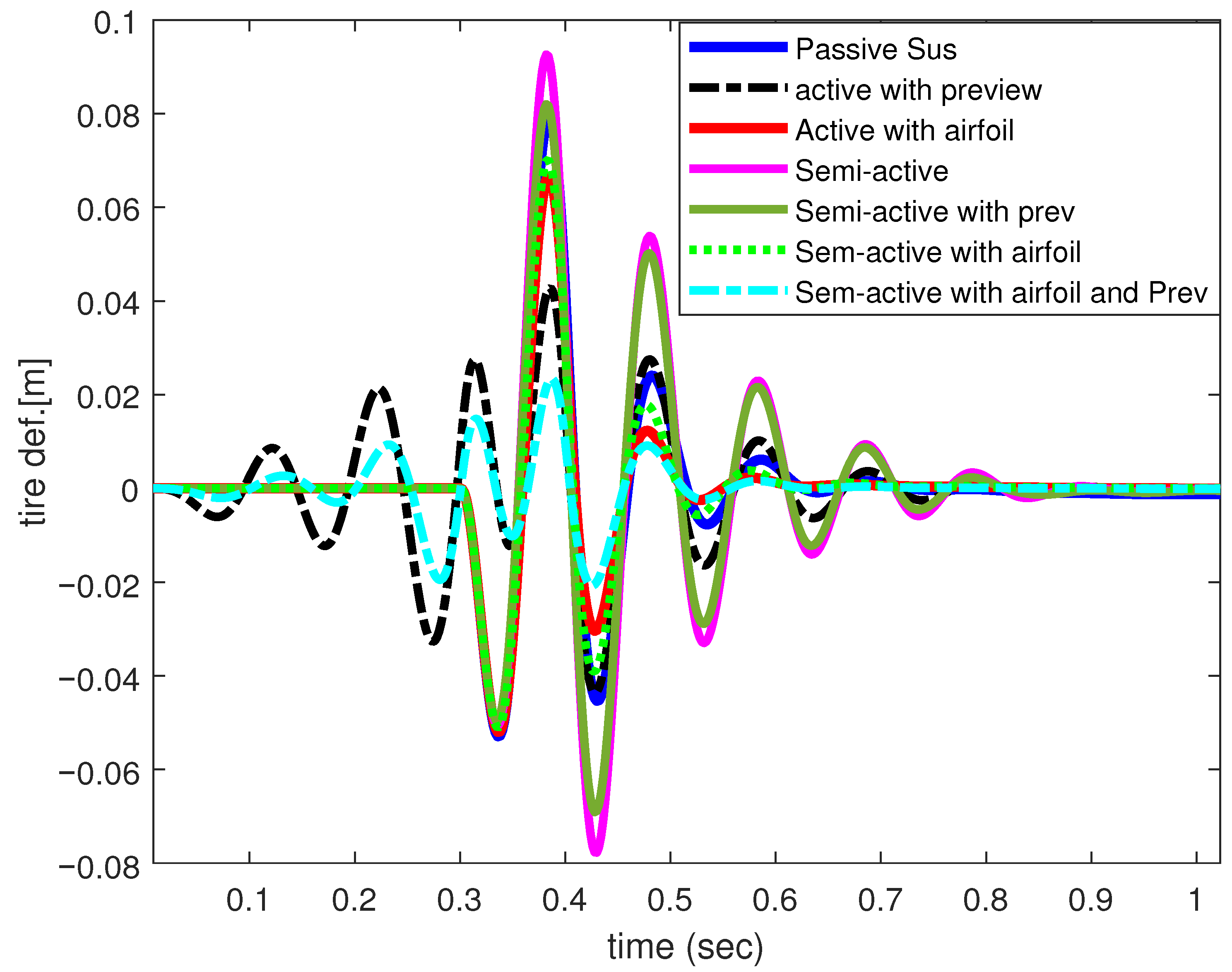

5.2. Time-Domain Numerical Simulation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAS | Active Aerodynamic Surface |

| SASS | Semi-active Suspension System |

| PSS | Passive Suspension System |

| ASS | Active Suspension System |

| MPC | Model Predictive Controller |

| KWLR | Knee Wheeled Legged Robot |

| V2V | Vehicle to Vehicle |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Controller |

| QoV | Quarter of Vehicle |

| AV | Autnomous Vehicle |

| ER | Electrical–Rheological |

| DBC | Differential Braking Control |

| AAC | Active Aerodynamic Control |

| ARE | Algebraic Riccati Equation |

References

- Kim, D.; Jeong, Y. Road-Adaptive Static Output Feedback Control of a Semi-Active Suspension System for Ride Comfort. Actuators 2024, 13, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.S.; Choi, S.B. Adaptive control for suspension system of in-wheel motor vehicle with magnetorheological damper. Machines 2024, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wen, H.; Xie, S. Performance Analysis and Hybrid Control Strategy Research of Vehicle Semi-Active Suspension for Ride Comfort and Handling Stability. Machines 2025, 13, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Yim, S. Design of static output feedback and structured controllers for active suspension with quarter-car model. Energies 2021, 14, 8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopala Rao, L.; Sharma, R.C.; Satyanarayana, V.; Palli, S. Stochastic optimal preview control response of a quarter-car nonlinear suspension model using spectral decomposition method. Noise Vib. Worldw. 2022, 53, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.G.; Narayanan, S. Preview control of random response of a half-car vehicle model traversing rough road. J. Sound Vib. 2008, 310, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, J. Incremental model predictive control of active suspensions with estimated road preview information from a lead vehicle. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2020, 142, 121004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Li, B.; Jing, H.; Niu, Z.; Wang, R. Wheel-Leg Collaborative Control for Wheel-legged Robots Based on MPC with Preview. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Automated Vehicle Validation Conference (IAVVC), Austin, TX, USA, 16–18 October 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, T.; Kim, C.J.; Yi, K. Model predictive control of a semi-active suspension with a shift delay compensation using preview road information. Control Eng. Pract. 2023, 137, 105584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, B.S. Preview Control of Automotive Active Suspension Systems to Improve Ride Comfort Using V2V Communication. In Proceedings of the 2021 21st International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 12–15 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1726–1729. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Z.; Gu, M. Ride comfort optimization via speed planning and preview semi-active suspension control for autonomous vehicles on uneven roads. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 8343–8355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarbouh, A.; Fayaz, M. Hybrid modelling and sliding mode control of semi-active suspension systems for both ride comfort and road-holding. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achnib, A.; Sename, O. Discrete-time multi-model preview control: Application to a real semi-active automotive suspension system. Control Eng. Pract. 2023, 137, 105553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, F. Integrated control of differential braking and active aerodynamic control for improving high speed stability of vehicles. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2020, 21, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, E.; Iqbal, J.; Arshad Khan, M.; Liang, W.; Youn, I. Predictive control using active aerodynamic surfaces to improve ride quality of a vehicle. Electronics 2020, 9, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurec, K.; Remer, M.; Mayer, T.; Tudruj, S.; Piechna, J. Flow control for a car-mounted rear wing. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 152, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhath, A.A.; Kasi, K. A review on various control strategies and algorithms in vehicle suspension systems. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2023, 20, 10720–10735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.B.; Youn, I. Performance Improvement of Active Suspension System Collaborating with an Active Airfoil Based on a Quarter-Car Model. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Ricci, A.; Blocken, B. CFD simulation of aerodynamic forces on the DrivAer car model: Impact of computational parameters. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 248, 105711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurec, K.; Remer, M.; Broniszewski, J.; Bibik, P.; Tudruj, S.; Piechna, J. Advanced modeling and simulation of vehicle active aerodynamic safety. J. Adv. Transp. 2019, 2019, 7308590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayhan, A.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Mim, R.H.; Ali, M. Computational and experimental study on the aerodynamic performance of NACA 4412 airfoil with slot and groove. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, W. Coupled Control of Preview Active Suspension and Longitudinal Dynamics for Autonomous Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 4656–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Y. Event-triggered model predictive-preview control strategy for trajectory tracking of autonomous vehicle. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2024, 46, 2345–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Si, Y.; Sun, W. Ride comfort oriented integrated design of preview active suspension control and longitudinal velocity planning. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 208, 110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitrakis, M.; Alexandridis, A. Active vehicle suspension control using road preview model predictive control and radial basis function networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 120, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, I.; Tchamna, R.; Lee, S.; Uddin, N.; Lyu, S.; Tomizuka, M. Preview suspension control for a full tracked vehicle. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2014, 15, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, I.; Ahmad, E. Anti-jerk optimal preview control strategy to enhance performance of active and semi-active suspension systems. Electronics 2022, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, D.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, W.; Gao, L. Vehicle Attitude Control of Magnetorheological Semi-Active Suspension Based on Multi-Objective Intelligent Optimization Algorithm. Actuators 2024, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, H.; Li, B.; Fu, C.; Tan, C.; Wei, W.; Sun, B.; Xie, X. Optimal design of an integrated electromagnetic linear energy regenerative suspension system based on a hybrid optimization objective. Energy 2025, 327, 136176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y. Optimal nonlinear polynomial control of a quarter-vehicle suspension system under harmonic and random road excitations. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2024, 43, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Li, J.Y.; Zhu, S. Active control for vehicle suspension using a self-powered dual-function active electromagnetic damper. J. Sound Vib. 2024, 569, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastinu, G.; Plöchl, M. Road and off-Road Vehicle System Dynamics Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khajepour, A.; Goodarzi, A. Vehicle Suspension System Technology and Design; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Savaresi, S.M.; Poussot-Vassal, C.; Spelta, C.; Sename, O.; Dugard, L. Semi-Active Suspension Control Design for Vehicles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Xia, D.; Li, W.; Han, G.; Du, X.; Fu, J. Research on finite frequency robust H infinity control of all-terrain vehicle magnetorheological suspension system. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 234, 112803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2631-1:1997; Mechanical Vibration and Shock—Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration—Part 1: General Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Yatak, M.Ö.; Şahin, F. Ride comfort–road holding trade-off improvement of full vehicle active suspension system by interval type-2 fuzzy control. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2021, 24, 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J.Z.; Burrow, S.; Neild, S.; Conn, A. Enhancing the trade-off between ride comfort and active actuation requirements via an inerter-based passive-active-combined automotive suspension. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2024, 62, 556–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lee, C. Preview Model Predictive Control of Semi-active Suspension for Speed Bump. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2025, 26, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Definition | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprung mass | kg | ||

| Unsprung mass | kg | ||

| Suspension stiffness | N/m | ||

| Tire stiffness | N/m | ||

| Passive damping coeff. | b | N·s/m | |

| Minimum damping coeff. | N·s/m | ||

| Max. damping coeff. | N·s/m |

| Type | Body acc. (%) | Tire def. (%) | Sus. def. (%) | Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive sus. sys. | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Active sus. with preview | 40.49 | 61.66 | 82.63 | 46.90 |

| Active sus. with an airfoil | 5.07 | 68.32 | 70.51 | 21.29 |

| Semi-active suspension sys. | 63.17 | 187.22 | 168.67 | 92.41 |

| Semi-active sus. with preview | 68.81 | 151.69 | 130.95 | 88.91 |

| Semi-active sus. with AAS. | 4.43 | 77.50 | 77.29 | 23.03 |

| SASS with AAS and preview | 2.55 | 13.93 | 51.21 | 7.27 |

| Type | Body acc. (%) | Tire def. (%) | Sus. def. (%) | Cost (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive sus. sys. | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Active sus. with preview | 35.62 | 67.37 | 53.96 | 43.71 |

| Active sus. with an airfoil | 7.71 | 75.53 | 69.63 | 27.04 |

| Semi-active suspension sys. | 57.45 | 154.73 | 101.60 | 81.17 |

| Semi-active sus. with preview | 54.50 | 88.54 | 66.79 | 62.52 |

| Semi-active sus. with AAS. | 8.07 | 84 | 72.52 | 29.28 |

| SASS with AAS and preview | 7.07 | 27.19 | 34.24 | 13.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, S.B.; Youn, I. Preview Control of a Semi-Active Suspension System Supplemented by an Active Aerodynamic Surface. Sensors 2025, 25, 6922. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226922

Abbas SB, Youn I. Preview Control of a Semi-Active Suspension System Supplemented by an Active Aerodynamic Surface. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6922. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226922

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Syed Babar, and Iljoong Youn. 2025. "Preview Control of a Semi-Active Suspension System Supplemented by an Active Aerodynamic Surface" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6922. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226922

APA StyleAbbas, S. B., & Youn, I. (2025). Preview Control of a Semi-Active Suspension System Supplemented by an Active Aerodynamic Surface. Sensors, 25(22), 6922. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226922