1. Introduction

Bearings are critical components of modern industrial equipment, and their failures can lead to severe economic losses and potential safety hazards [

1,

2]. Therefore, predicting the RUL of bearings is crucial to achieving predictive maintenance [

3]. In recent years, data-driven methods have achieved success not only in bearing RUL prediction but also in other mechanical systems due to their ability to extract features directly from raw data [

4,

5]. For example, Spirto et al. [

6] employed neural networks for gear fault detection. Similarly, Babak et al. [

7,

8] proposed a stochastic model for the diagnosis of electrical equipment. However, in real-world scenarios, accurate RUL prediction remains challenging because the feature distributions of training and testing data may differ due to variations in machine manufacturing and working conditions [

9,

10].

To minimize the feature distribution differences in bearing RUL prediction, DA has emerged as an effective method [

11]. DA aims to align feature distributions between training and testing data, enabling models trained on source domain data to generalize effectively to target domain data without requiring labeled data from the target domain. Popular DA methods, such as adversarial-based methods [

12] and metric-based methods [

13], have successfully improved RUL prediction accuracy across different domains. However, these methods often assume that the entire source and target domains experience the same type of domain shift, resulting in global-scale alignment.

Global-scale alignment overlooks fine-grained discrepancies in feature distributions, which are crucial for accurate RUL predictions [

14]. In bearing RUL prediction, features evolve across distinct health stages, and global alignment may incorrectly match features from different stages, leading to negative transfer. In contrast, local-scale alignment addresses this problem by grouping features with similar health conditions and aligning them separately, thereby preserving stage-specific patterns and temporal progression. For example, in temperature prediction tasks, short-term fluctuations may reflect hourly weather variations, whereas long-term trends capture seasonal changes [

15]. Globally aligning all data would mix short- and long-term patterns, reducing prediction accuracy. Similarly, in bearing RUL prediction, aligning features from early, mid, and late degradation stages separately allows the model to capture stage-specific degradation patterns, improving transferability and prediction performance.

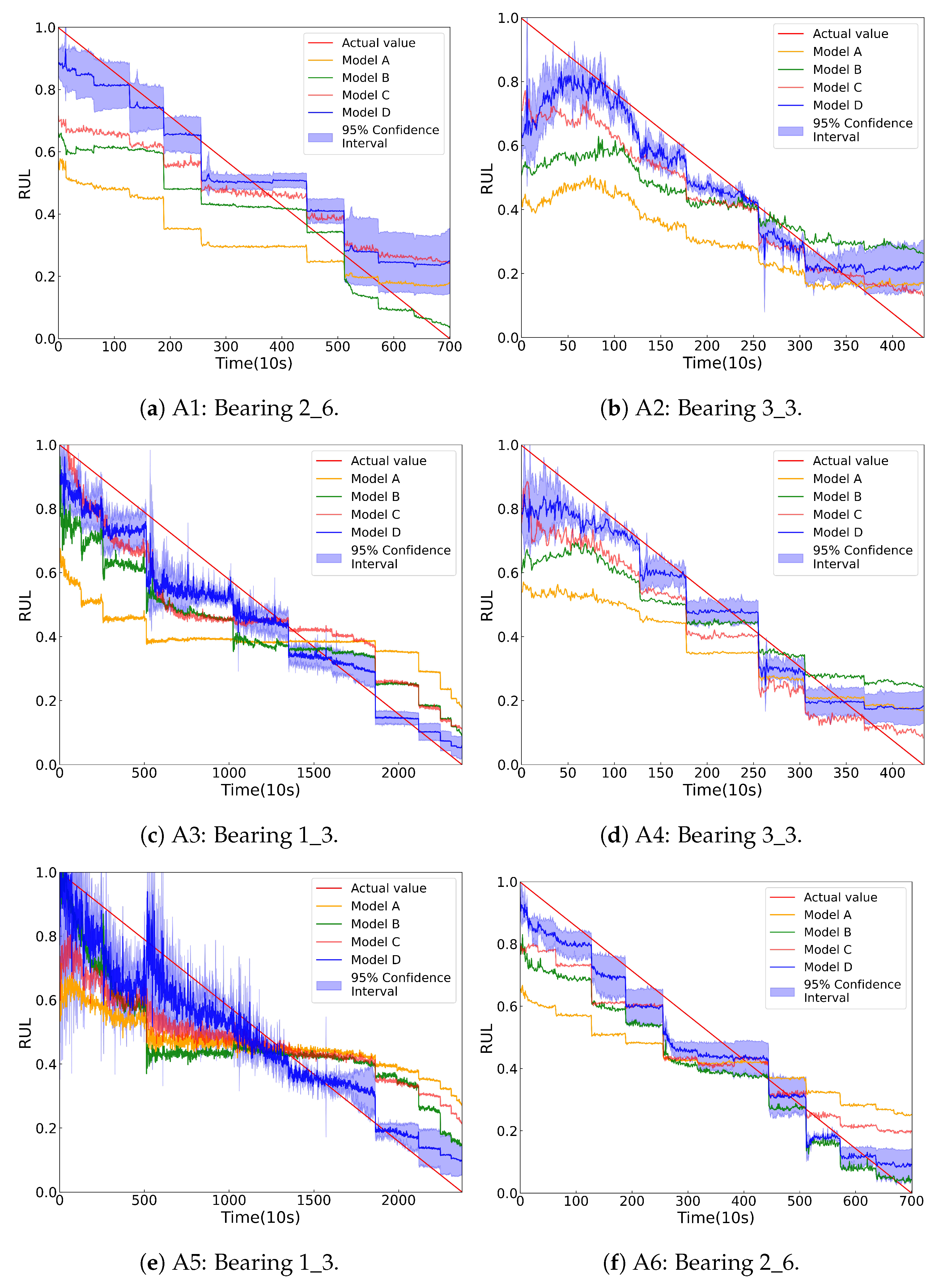

To achieve local-scale alignment, SDA has been proposed as a potential solution. Although SDA methods improve RUL prediction accuracy compared to traditional DA methods through subdomain-level alignment, three key limitations still hinder their potential to further enhance prediction performance.

(1)

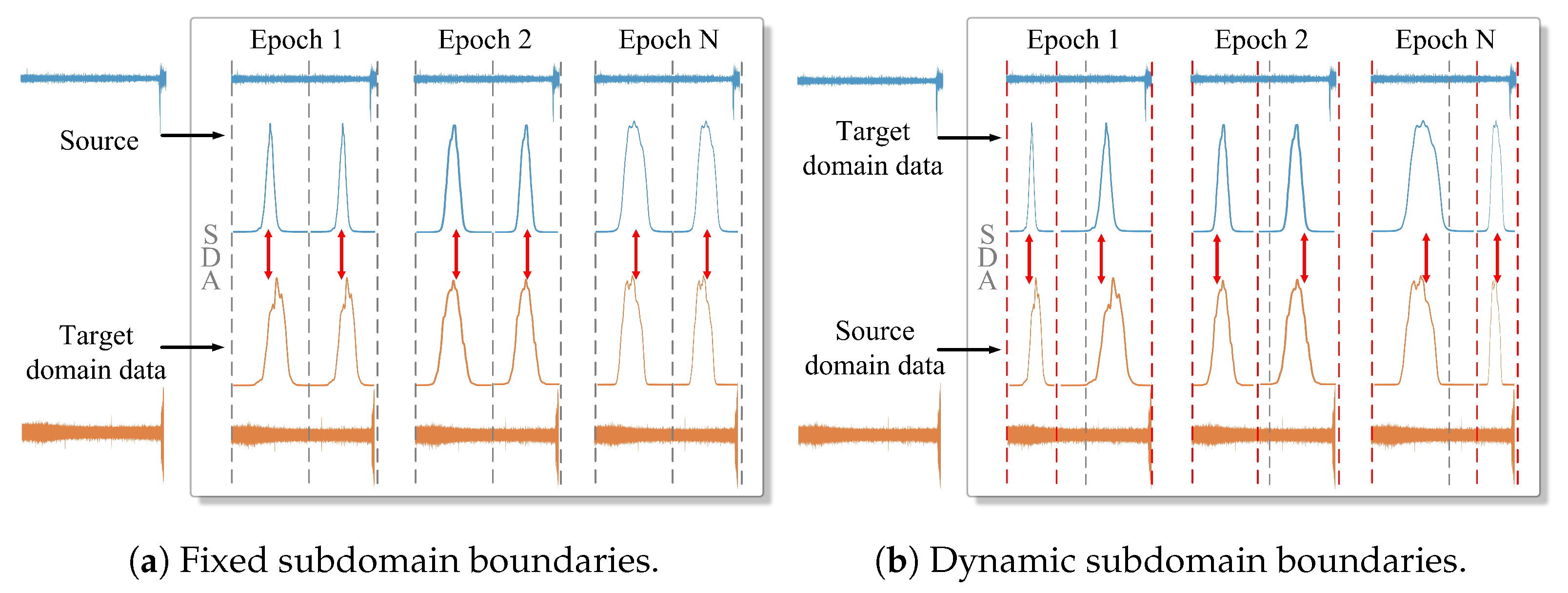

Static subdomain division: many SDA methods divide subdomains prior to the alignment process, resulting in fixed subdomain boundaries, as shown in

Figure 1a. However, feature distributions often evolve during training, making these predefined fixed subdomain boundaries inaccurate [

16]. For example, some features may shift across subdomains during training but remain incorrectly assigned to their original subdomains, as shown in

Figure 1b. Without real-time updates to adjust these boundaries, models struggle to adapt to evolving feature spaces, hindering fine-grained subdomain alignment.

(2)

Unequal importance of subdomains: different subdomains contribute unequally to SDA. For example, some subdomains represent the healthy stage of the bearing, while others represent the degradation stage [

17]. During domain alignment, subdomains located in the degradation stage offer more degradation-related patterns than those in the healthy stage [

18]. Therefore, it is crucial to assign greater importance to subdomains that represent the degradation stage during SDA. Treating all subdomains equally may lead to ineffective knowledge transfer and even negative transfer effects [

19].

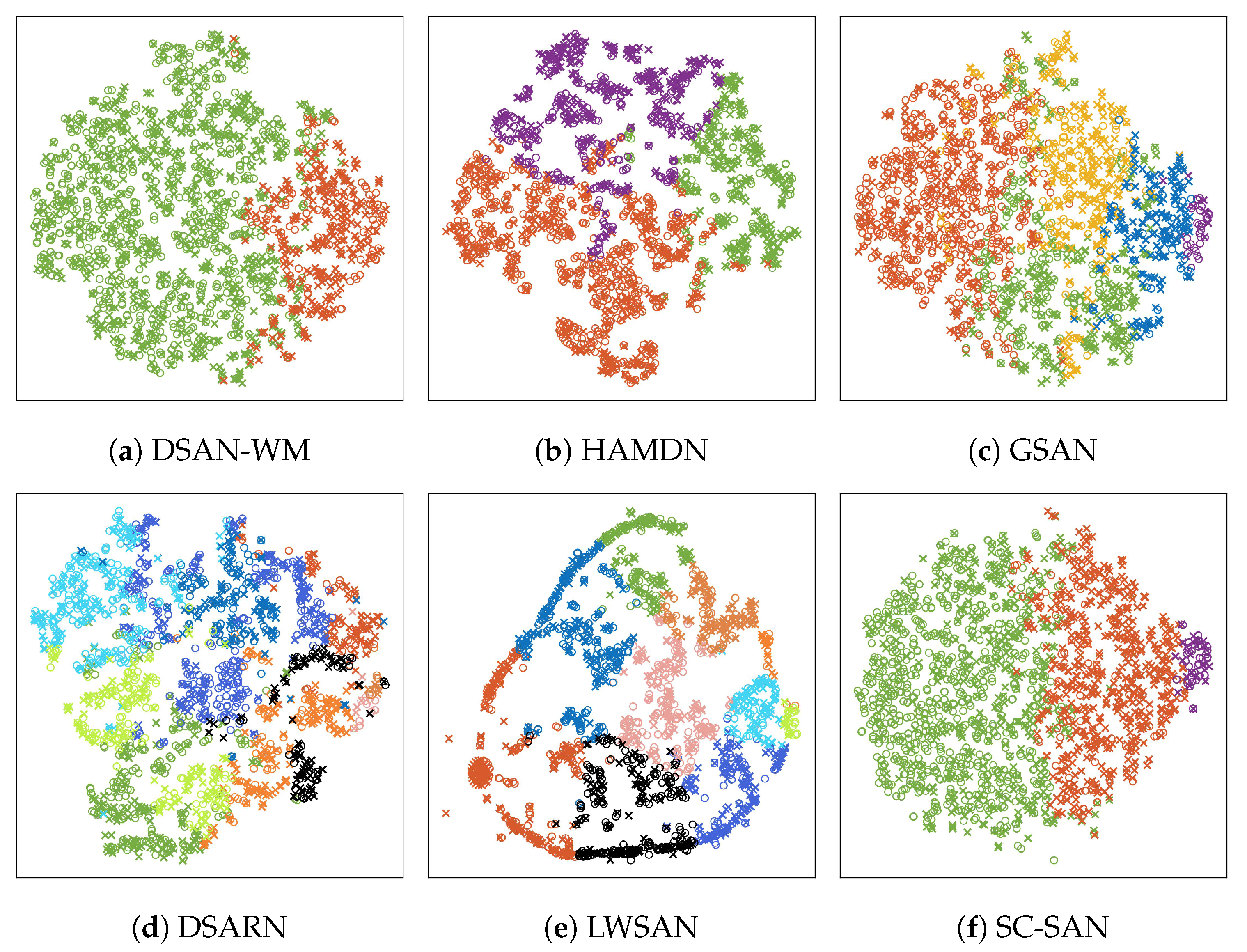

(3) Fuzzy subdomain boundaries: most SDA methods fail to encourage the clustering of features with similar distributions while separating features with dissimilar distributions during training. This often causes subdomains to be divided based on disordered feature distributions. Introducing a clustering mechanism to group similar features ensures that subdomains are divided based on well-clustered feature distributions, enabling precise subdomain division.

To address these three limitations, this paper proposes a novel RUL prediction model called SC-SAN, designed as an end-to-end model based on SDA. SC-SAN consists of a backbone network and three auxiliary modules. The backbone network aims to encode features and map them to prediction outputs. The three auxiliary modules are: ① a temporal weight (TW) generator, which assigns different weights to features using a normalized time-scalar function; ② a spectral clustering (SC) module, which groups similar features and separates dissimilar features during training; and ③ an SDA module, which performs subdomain-level alignment.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

The proposed SC-SAN dynamically adjusts subdomain boundaries during the training process, achieving fine-grained subdomain alignment.

- 2.

SC-SAN generates a normalized time-scalar function to assign greater importance to degradation-related features during SDA, facilitating accurate RUL prediction.

- 3.

SC-SAN incorporates a clustering mechanism into the parameter update process, guiding the model to update parameters in a way that groups similar features while separating dissimilar features, ensuring precise subdomain division.

The paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work on DA and SDA for RUL prediction.

Section 3 explains the implementation of the proposed SC-SAN.

Section 4 describes a case study on RUL prediction using SC-SAN and evaluates it with standard metrics.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

Figure 1.

Visualization of subdomain boundaries. (a) The blue and orange curves depict the distributions of the source and target domains, with red arrows illustrating the process of reducing discrepancies between them. (b) Black dashed lines indicate the initial subdomain boundaries, while red dashed lines show the boundaries dynamically adjusted during each epoch.

Figure 1.

Visualization of subdomain boundaries. (a) The blue and orange curves depict the distributions of the source and target domains, with red arrows illustrating the process of reducing discrepancies between them. (b) Black dashed lines indicate the initial subdomain boundaries, while red dashed lines show the boundaries dynamically adjusted during each epoch.

3. The Proposed Method

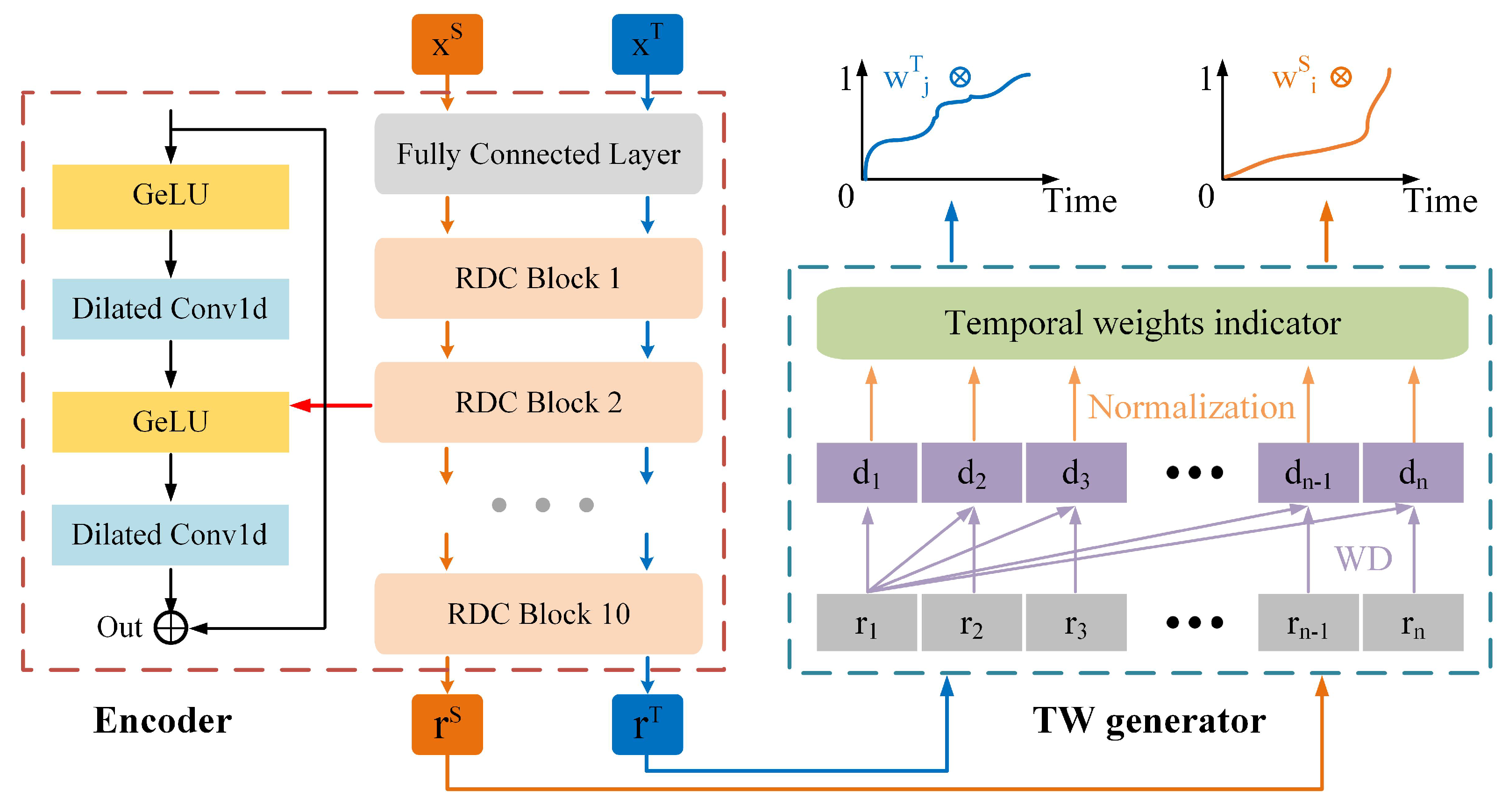

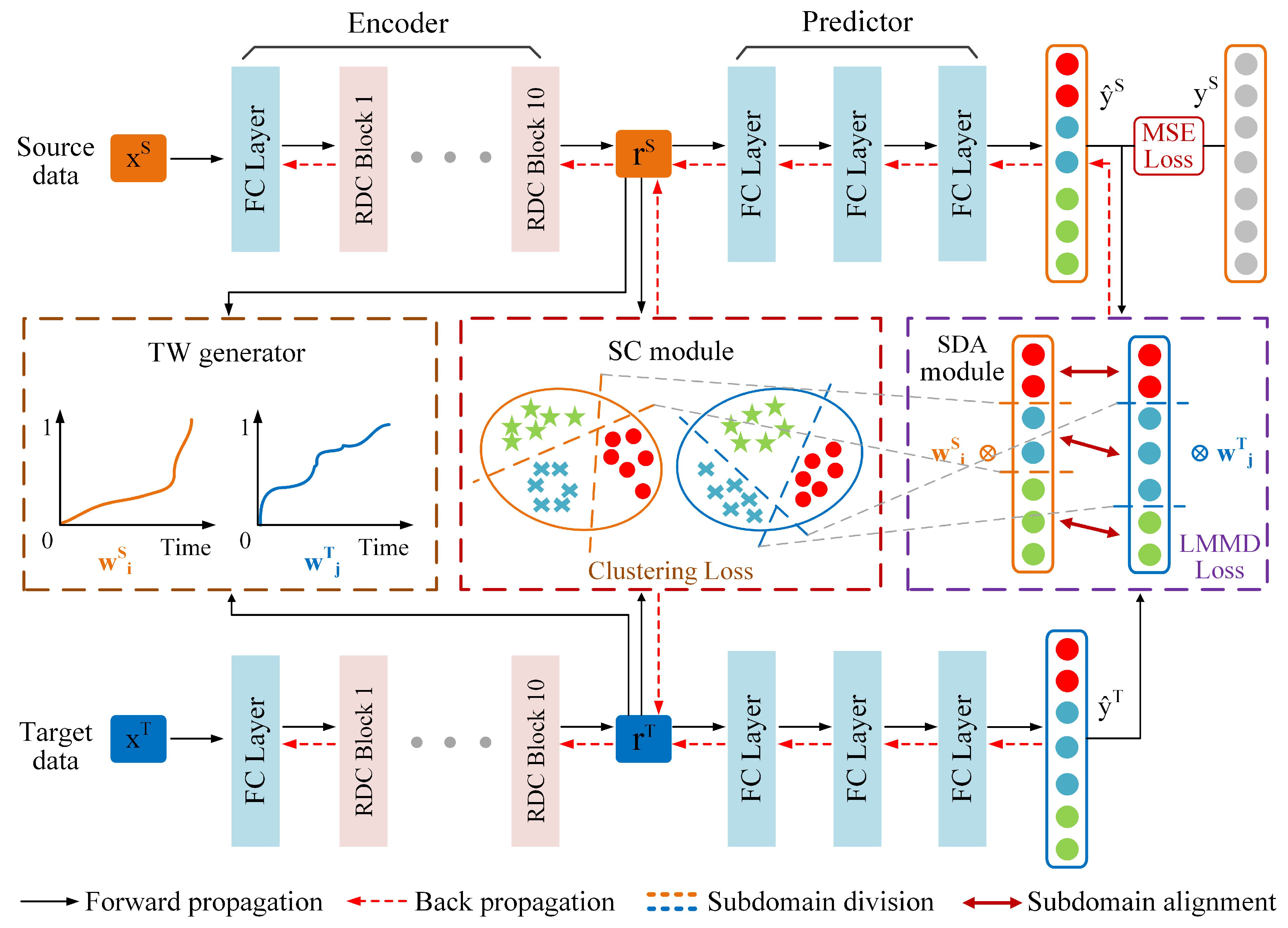

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the proposed SC-SAN consists of a backbone network and three auxiliary modules: ① a backbone RUL prediction network; ② a TW generator; ③ an SC module; and ④ an SDA module.

Compared with existing SDA methods that rely on fixed subdomain boundaries, overlook the unequal importance of subdomains, and lack structural clustering constraints for feature grouping, SC-SAN introduces three auxiliary modules to overcome these limitations. Specifically, the TW generator constructs a normalized time indicator to adaptively assign different weights to different degradation stages. The SC module enforces clustering-aware constraints to group similar features and separate dissimilar ones, enabling dynamic adjustment of subdomain boundaries based on the evolving feature distribution. The SDA module aligns the feature distributions among the dynamically generated subdomains, facilitating robust cross-domain knowledge transfer. This section details the functions and implementations of each component. For clarity, all frequently used symbols in this section are summarized in

Table 2.

3.1. The Backbone RUL Prediction Network

The proposed backbone RUL prediction network comprises two components: an Encoder and a Predictor. The Encoder reduces the feature dimensions of raw data to facilitate downstream tasks such as RUL prediction and SDA. Specifically, it transforms the input data

into feature representations

, where

. The definitions of

N,

M, and

V are detailed in

Table 2. The Predictor then maps these learned representations

r to RUL prediction values

, where each value in

corresponds to a predicted RUL at each time step. The structure and function of each component are detailed in the following.

Encoder is designed to transform high-dimensional raw input data from both source and target domains (

and

) into low-dimensional feature representations (

and

), improving the efficiency of feature extraction [

41]. The proposed Encoder consists of a fully connected layer and 10 sequentially connected

residual dilated convolution (RDC) blocks, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Each RDC block contains two 1-D convolutional layers for feature extraction, two GeLU activation functions to introduce nonlinearity, and a residual connection to mitigate problems such as vanishing or exploding gradients [

15,

42].

Predictor utilizes the low-dimensional feature representations and learned by the Encoder as input. These representations are processed through three fully connected layers, with the final output: RUL prediction values and , corresponding to the source and target domains, respectively.

Figure 3.

The structure of the Encoder and the mechanism of the temporal weight generator. Orange and blue lines represent two separate paths for source and target domain data. Both are encoded by the Encoder, and then processed by the TW generator to produce temporal weights for each domain.

Figure 3.

The structure of the Encoder and the mechanism of the temporal weight generator. Orange and blue lines represent two separate paths for source and target domain data. Both are encoded by the Encoder, and then processed by the TW generator to produce temporal weights for each domain.

3.2. The Temporal Weight Generator

The design of the TW generator is based on the premise that the degradation of a bearing can be reflected by the gradual divergence of feature distributions over time [

43]. As the health state deteriorates, the extracted features deviate increasingly from those of the initial healthy state [

44]. Therefore, the distribution distance between the feature representation at each time step

and that at the initial time step

can serve as an effective indicator of the degradation degree.

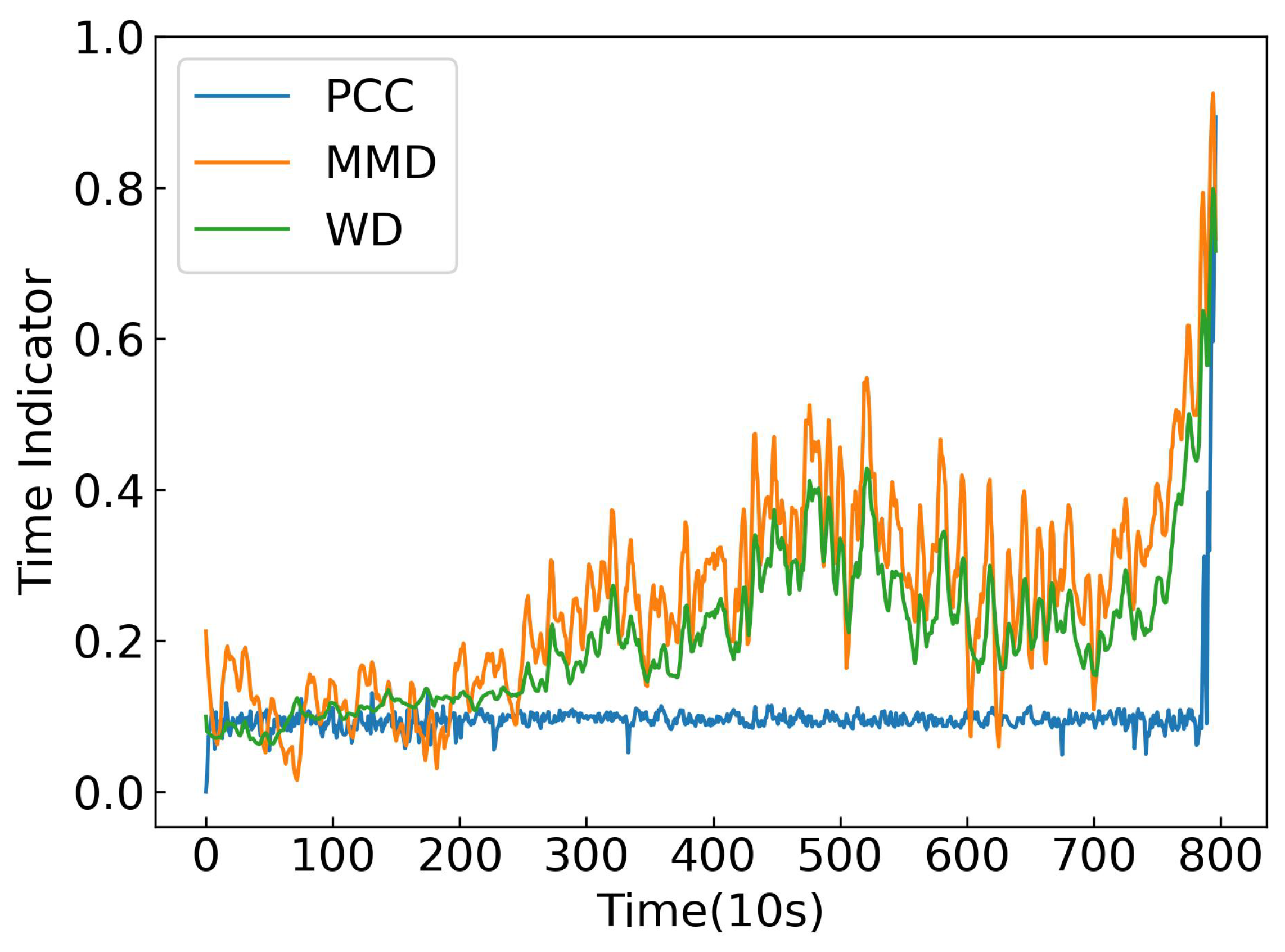

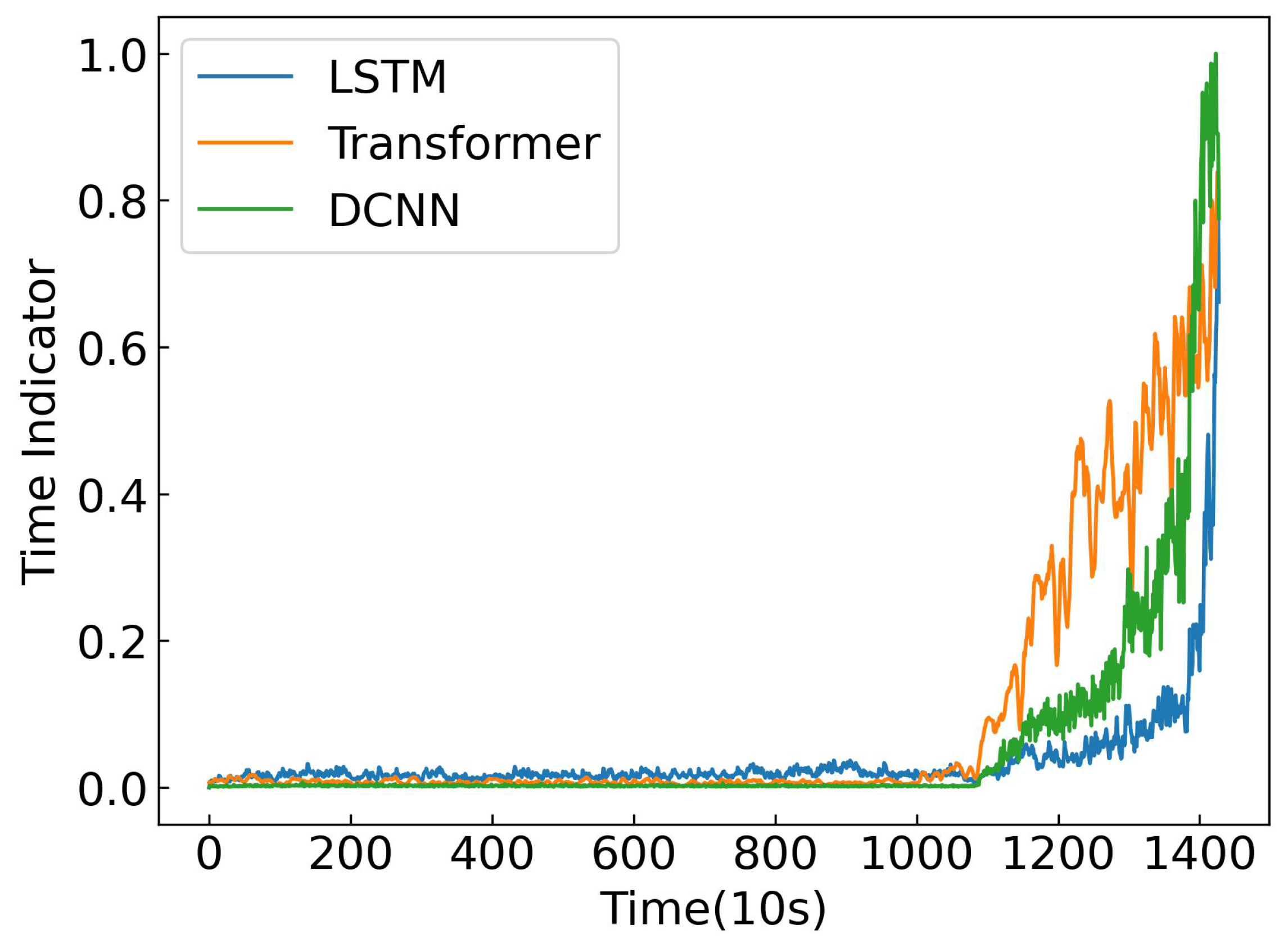

Based on this motivation, the TW generator constructs a normalized time indicator

to capture the health level of a bearing over time. As illustrated in

Figure 3, this indicator is derived by measuring the feature distribution distance

, between the feature representation at each time step

and the feature representation at the initial time step

. These calculated distances

, are then normalized to produce the time indicator

, which ranges from 0 to 1.

In this paper, the WD is used to measure the feature distribution distance

between

and

, and its calculation can be described as [

31]:

where

represents the set of all possible joint distributions between the feature representation at time step

and the feature representation at the initial time step

.

represents a sample from this joint distribution.

After calculating the distance

for each time step, min—max normalization is applied to scale these distances into the time indicator

, which lies within the range

[

13]. The formula for this normalization is:

where

and

are the minimum and maximum distances across all time steps.

3.3. The Spectral Clustering Module

Time-series data in RUL prediction often exhibit evolving feature distributions over time, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Conventional two-stage SDA methods typically divide subdomains with fixed boundaries before performing alignment. However, such predefined and static boundaries fail to adapt to the temporal evolution of feature distributions. Moreover, when subdomains are divided based on disordered features, samples that should belong to the same subdomain may be incorrectly assigned to different ones, resulting in degraded prediction accuracy.

To address these issues, SC is adopted as a graph-based clustering method to identify subdomains in dynamic feature spaces [

45]. It first constructs a similarity graph that models pairwise relationships among feature samples and then derives a graph Laplacian to capture the global data structure. By analyzing the spectral properties of this Laplacian, SC embeds samples into a lower-dimensional space, where similar features are more effectively grouped and subdomains are clearly separated.

In RUL prediction, the SC algorithm maximizes similarity within clusters and minimizes similarity across clusters, leading to compact and well-separated subdomains. When integrated with SDA, this clustering strategy reduces feature overlap and preserves the temporal consistency of degradation patterns, thereby enhancing the alignment between source and target domains. Accordingly, the proposed SC module dynamically updates subdomain boundaries during training and periodically reclusters features to improve boundary clarity and subdomain discriminability. The implementation of the proposed SC module involves four steps, which are described as follows:

Step 1: Initialization of subdomain boundaries. Although subdomain boundaries can be intuitively described as dividing lines in a two-dimensional space, in implementation they are implicitly represented by a cluster indicator matrix. Since feature representations

generated by the Encoder capture the degradation patterns of bearings, applying K-means clustering to

r can group similar features into

K clusters/subdomains [

46,

47]. The clustering result is encoded as a one-hot matrix

, where each row

indicates the subdomain assignment of sample

i. In this way,

implicitly defines the subdomain boundaries: if two samples have similar rows, they are considered to belong to the same subdomain.

Step 2: Softening of subdomain boundaries. Subdomain boundaries are initialized using K-means clustering in Step 1, generating a one-hot indicator matrix

. However, the bearing degradation process is continuous and gradual, this hard assignment may lead to misclassification at subdomain boundaries. To address this, soft clustering is more appropriate than one-hot clustering, as it represents the probability that each sample belongs to each subdomain. Therefore, a soft clustering method based on

truncated singular value decomposition (Truncated SVD) is used to soften the subdomain boundaries [

48,

49].

Specifically, the feature representations

are decomposed via Truncated SVD as

, where

,

, and

. The soft subdomain boundary indicator matrix

is then defined as:

where

denotes the

i-th row of

. This row-wise normalization turns each row vector into a probability distribution over

K subdomains. The matrix

provides a low-dimensional embedding of the samples that capture their principal components.

Step 3: Clustering of feature representations. The soft clustering indicator matrix

obtained in Step 2 not only represents the probability distribution of subdomains, but also serves as a guide matrix to cluster similar features within

. Inspired by spectral clustering, the clustering objective can be reformulated as a trace maximization problem based on the spectral relaxation method, which aims to maximize

. Maximizing this trace encourages

to keep the most important information of the similarity matrix

. As a result, samples from the same subdomain will be projected closer, while samples from different subdomains will be projected further apart. The spectral clustering loss can be defined as:

where

denotes the matrix trace,

is feature representations to be clustered, and

is an orthogonal indicator matrix. Here,

N is the number of samples,

V is the number of features in the feature representation, and

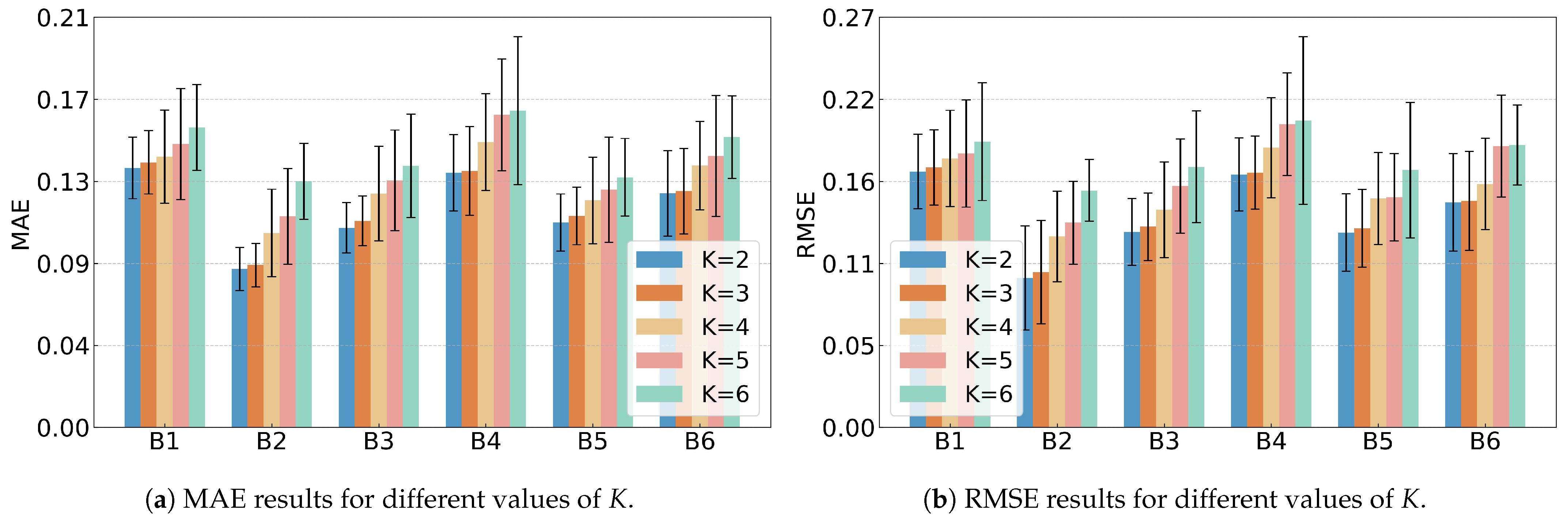

K is the number of clusters.

Step 4: Iterative update of subdomain boundaries and feature representations. To dynamically divide subdomain boundaries based on the evolving feature distribution, feature representations r and the clustering indicator matrix are optimized in an iterative manner. In each iteration, when is fixed, r is updated under the guidance of . This encourages r to be more compact within each subdomain and more distinguishable across different subdomains. Conversely, when r is fixed, is updated based on the current feature distribution. This update allows the model to adjust subdomain boundaries that better reflect the evolving similarity relationships among samples. To ensure stable training, is updated once every 40 epochs, while r is updated at every epoch.

3.4. The Subdomain Adaptation Module

The SDA module is a critical component of the proposed SC-SAN, designed to bridge the gap between the source and target domains by leveraging local maximum mean discrepancy (LMMD). Unlike traditional DA methods that focus on global-scale alignment, the SDA performs alignment at the subdomain level, effectively capturing localized variations in the degradation process across domains.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the Predictor maps the source domain representation

and target domain representation

into RUL prediction results, denoted as

and

, respectively.

These prediction results are then input into a high-dimensional feature space, where and are divided into different subdomains using clustering indicator matrices and generated by the SC module. Within each subdomain, the feature distribution discrepancies are minimized through optimizing the LMMD loss. During the domain alignment process, TW indicators and are introduced for the source and target domains to emphasize the importance of specific samples based on their temporal relevance within the degradation cycle. By assigning higher weights to critical time steps, the SDA module ensures precise feature alignment while accounting for the temporal sensitivity of the data.

The LMMD is calculated using a Gaussian kernel function

, which measures the discrepancies between the distributions of

and

within each subdomain. The LMMD is defined as:

where

K represents the number of subdomains/clusters;

and

denote the temporal weights for source and target domain features, reflecting the temporal importance of individual samples;

and

denote the number of samples in subdomain

k for the source and target domains, respectively;

denotes the reproducing kernel Hilbert space; and

is defined as a Gaussian kernel function.

3.5. Model Parameters Optimization

Model parameters optimization is guided by three objectives: ① the RUL prediction loss , which measures the difference between the ground truth and predicted RUL; ② the spectral clustering loss , which clusters similar features while separating dissimilar features; and ③ the domain distribution loss , which minimizes the discrepancies between the predicted values in the source and target domains.

RUL prediction loss: for the first optimization objective, the

mean square error (MSE) is used to define the prediction error

, which is commonly used in regression problems [

23]. The MSE is expressed as follows:

where

and

are the predicted RUL values and the ground truth RUL values both from the source domain, respectively.

is the number of samples in the source domain.

Spectral clustering loss: for the second optimization objective, spectral clustering is used to cluster similar feature representations while separating dissimilar ones within both source and target domains. The total clustering loss

is defined as follows:

where

denotes the matrix transpose;

and

represent the similarity matrices of the source and target domains;

and

are the soft cluster indicator matrices for the source and target domains; and

is the trace of a matrix.

Domain distribution loss: for the third optimization objective, the LMMD is used to calculate the subdomain loss

, which is expressed as follows:

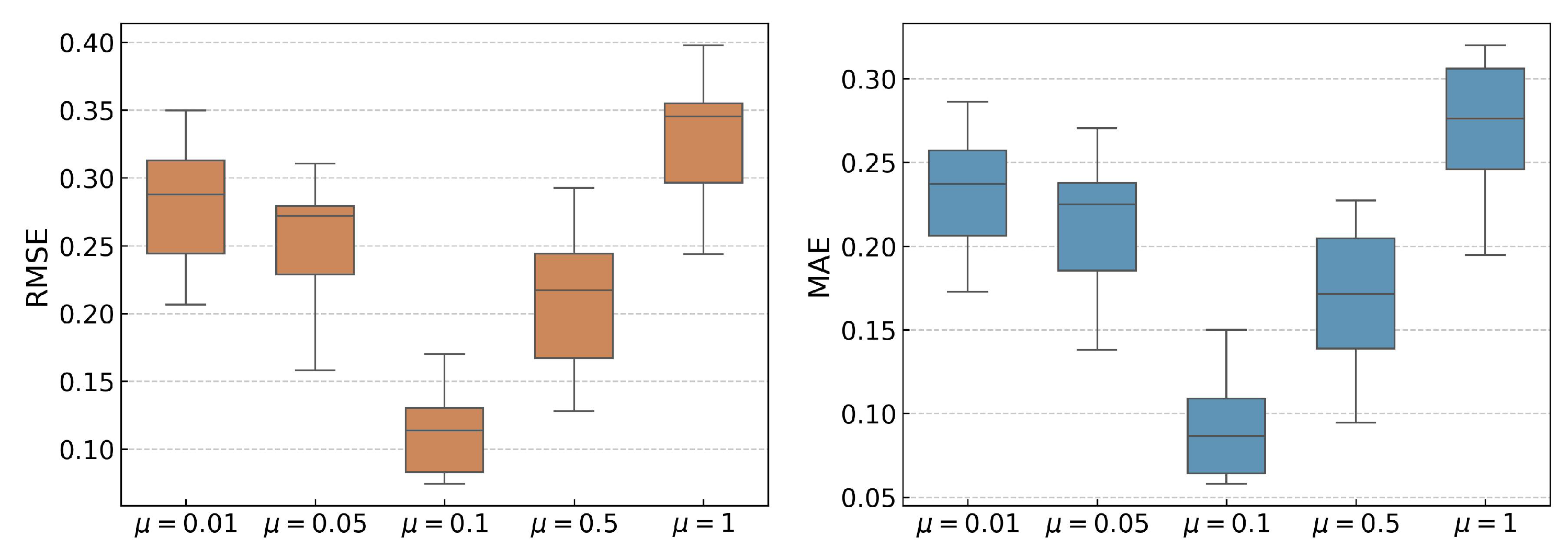

Total loss: the total loss

of the proposed SC-SAN integrates the three objectives described above (Equations (

6)–(

8)) and is formulated as:

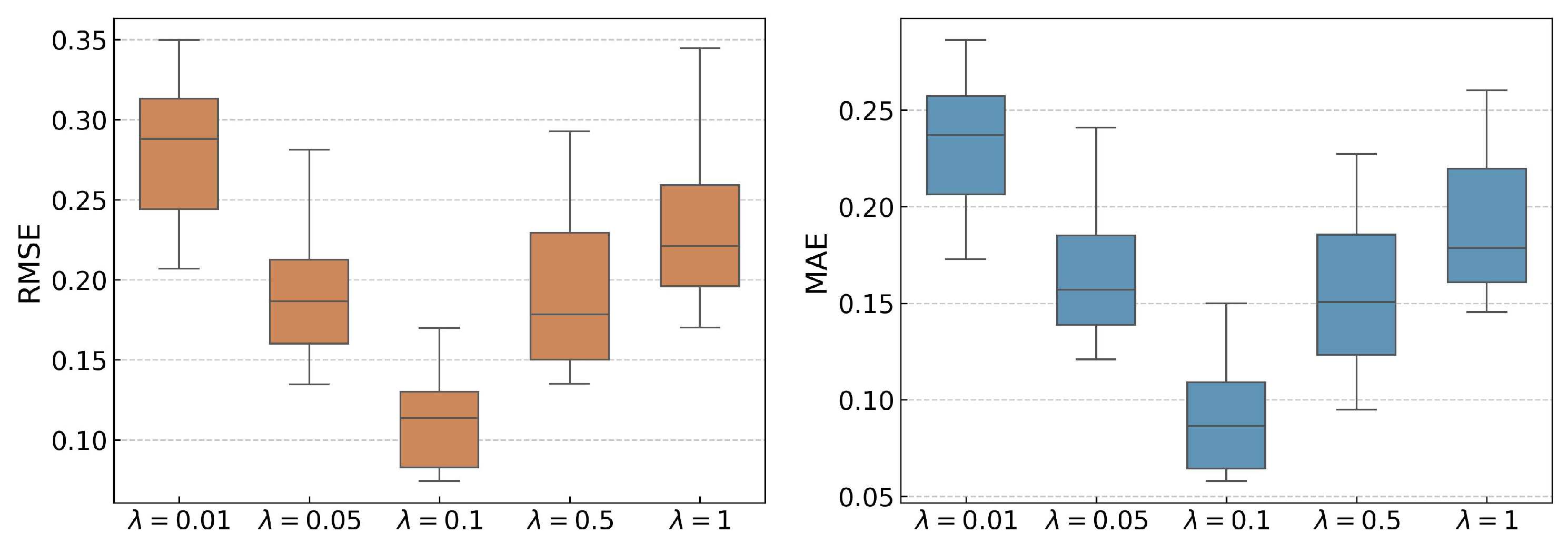

where

,

denotes the tradeoff parameters, set to 0.1 and 0.1, respectively.

Once the loss function

is defined, the optimal parameters for the proposed SC-SAN can be obtained by optimizing the loss function. The steps involved in this process are summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 SC-SAN |

- 1:

procedure Main(raw data) - 2:

for in raw data do - 3:

// Feature extraction: - 4:

Encoder ; - 5:

// TW generator: - 6:

WD calculation ; - 7:

Normalization ; - 8:

// RUL prediction: - 9:

Predictor ; - 10:

// Calculate prediction loss: - 11:

MSELoss; - 12:

// Calculate clustering loss: - 13:

Initialize cluster indicator matrix K; - 14:

Source clustering loss ; - 15:

Target clustering loss ; - 16:

Sum clustering loss ; - 17:

for t in 1 to Max epoch do - 18:

// Update every 40 epochs: - 19:

if then - 20:

Truncated SVD ; - 21:

end if - 22:

end for - 23:

// Calculate domain loss: - 24:

LMMDLoss; - 25:

; - 26:

// Update model parameters using - 27:

end for - 28:

end procedure

|

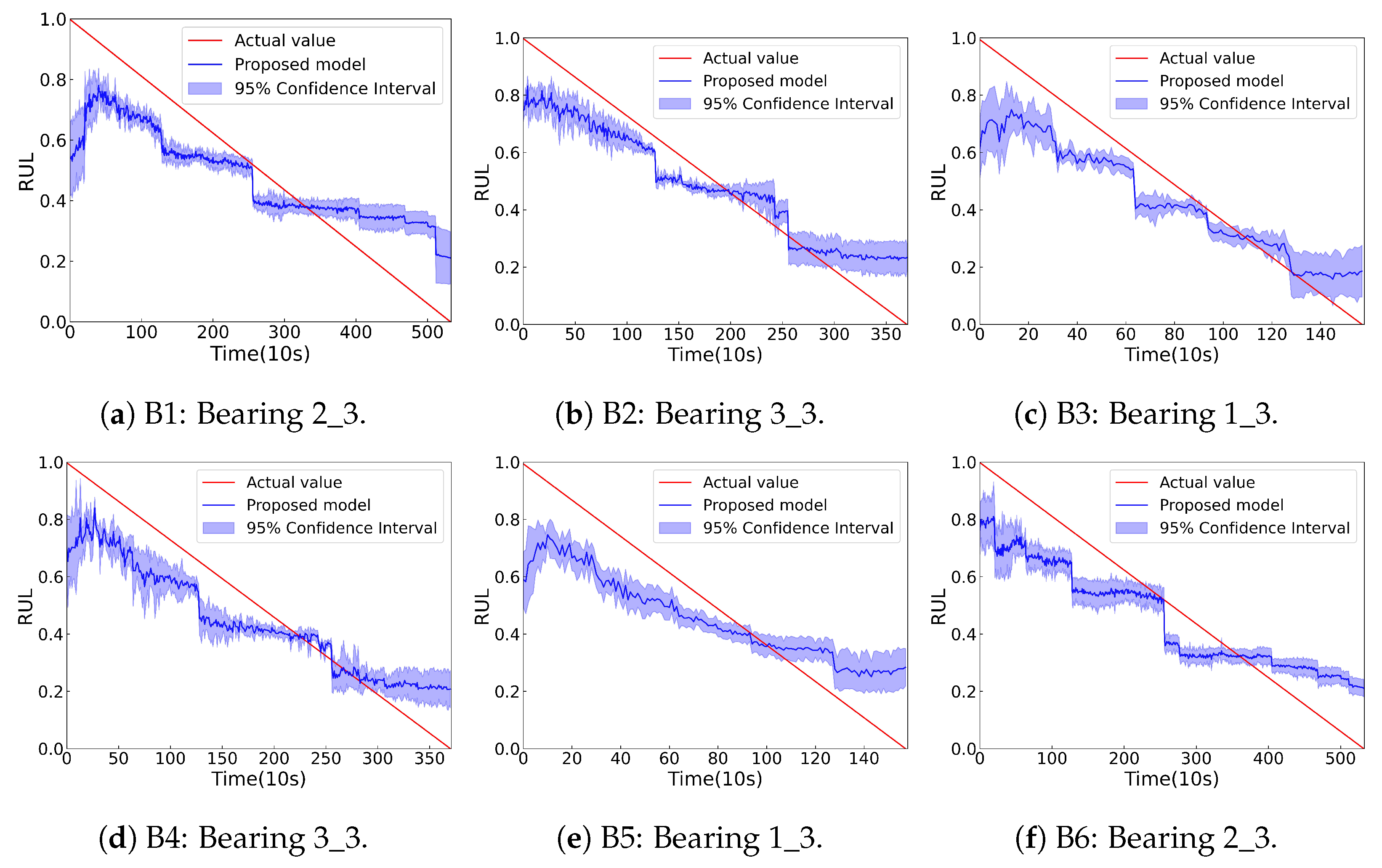

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a SC-SAN, which integrates a backbone RUL prediction network, a TW generator, an SC module, and an SDA module. Experimental results based on two bearing datasets, including ablation, comparison, and validation experiments, highlight the following key findings: ① SC-SAN adaptively adjusts subdomain division boundaries, achieving fine-grained subdomain alignment. ② SC-SAN effectively clusters similar features while separating dissimilar features, ensuring precise subdomain division. ③ By assigning greater importance to degradation-related features during SDA, SC-SAN outperforms state-of-the-art models.

Despite its strengths, SC-SAN faces challenges in real industrial deployment. Degradation in real equipment occurs over long periods, and components cannot be allowed to fail, so only partial degradation segments are available for training. Combined with variability in operating conditions and measurement noise, these factors may limit subdomain alignment and RUL prediction accuracy. Future work will focus on adapting SC-SAN to handle partial, heterogeneous, and noisy industrial data, ensuring robust performance across diverse scenarios.