The Application of VR Technology in Engineering Issues: Geodesy and Geomatics, Mining, Environmental Protection and Occupational Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

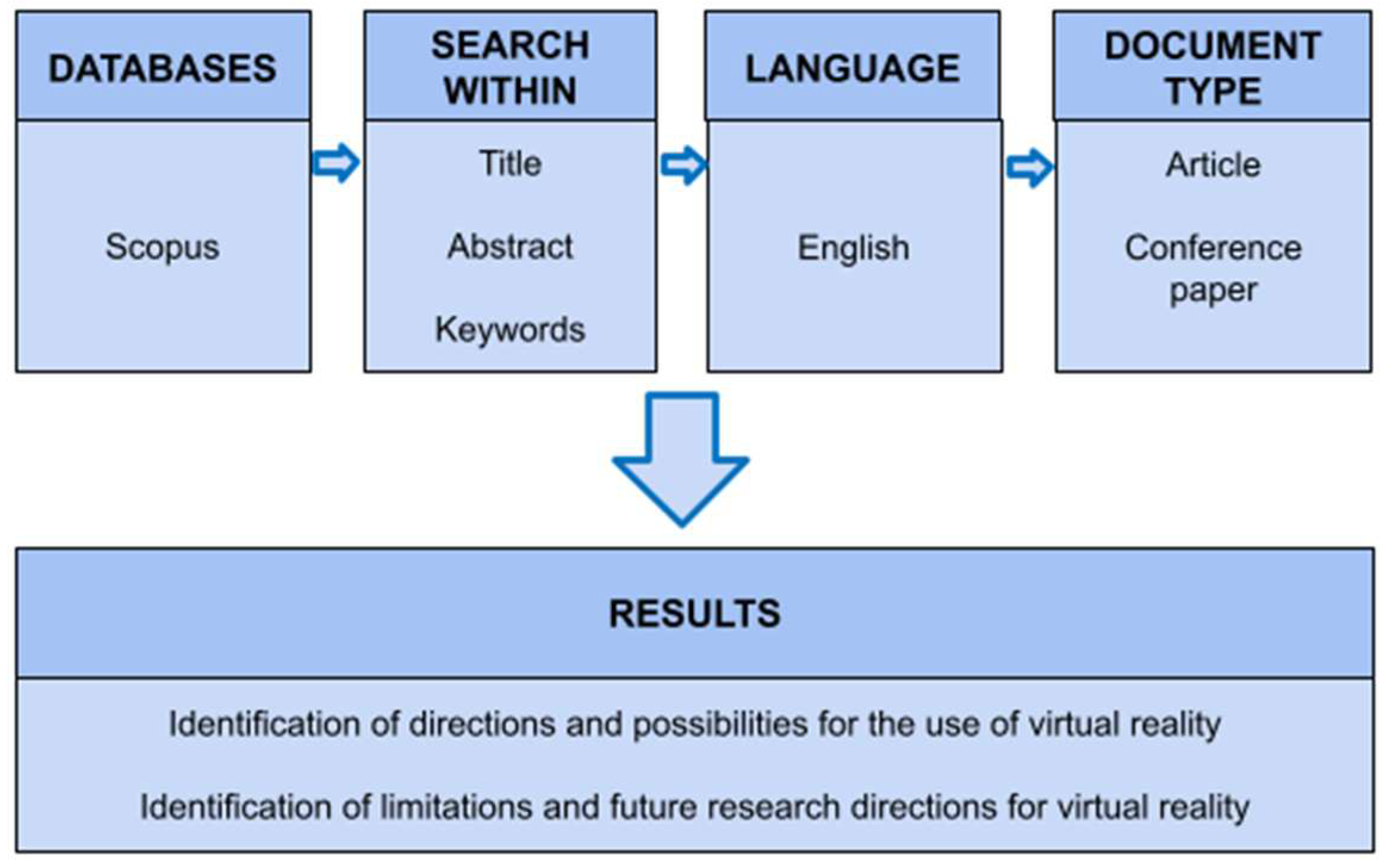

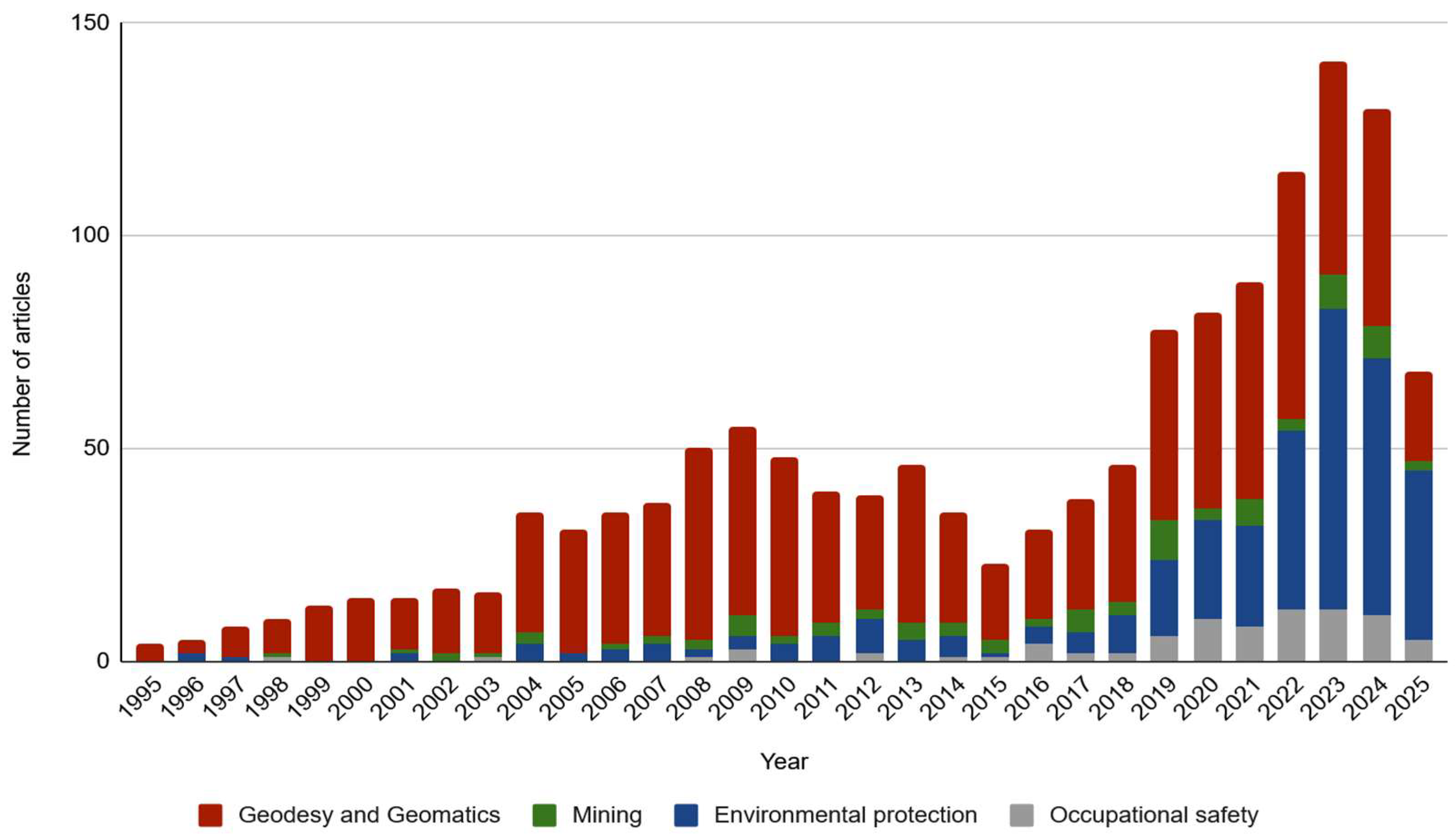

2. Materials and Methods

3. VR in Engineering Topics

3.1. VR in Geodesy and Geomatics

3.1.1. Geometry Acquisition and Reconstruction Approaches for VR

- –

- Aerial photogrammetry, where images are acquired from an aircraft or an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), usually in nadir mode, for cartographic, environmental, or spatial landscape analyses.

- –

- Terrestrial photogrammetry, based on images captured from ground level using cameras on tripods or handheld, widely applied in façade documentation, architectural details, and engineering structures.

- –

- Close-range photogrammetry, involving images taken from short distances (up to several metres), used in engineering, archaeology, heritage conservation, or technical inspections. It can be carried out both from ground level and using UAVs at low altitudes.

3.1.2. VR Application in Classical Geodesy and Geomatics

3.2. VR in Mining

3.3. VR in Environmental Protection

3.4. VR in Occupational Safety

4. Limitations and Potential of Virtual Reality Technology

4.1. Limitations of VR Technology

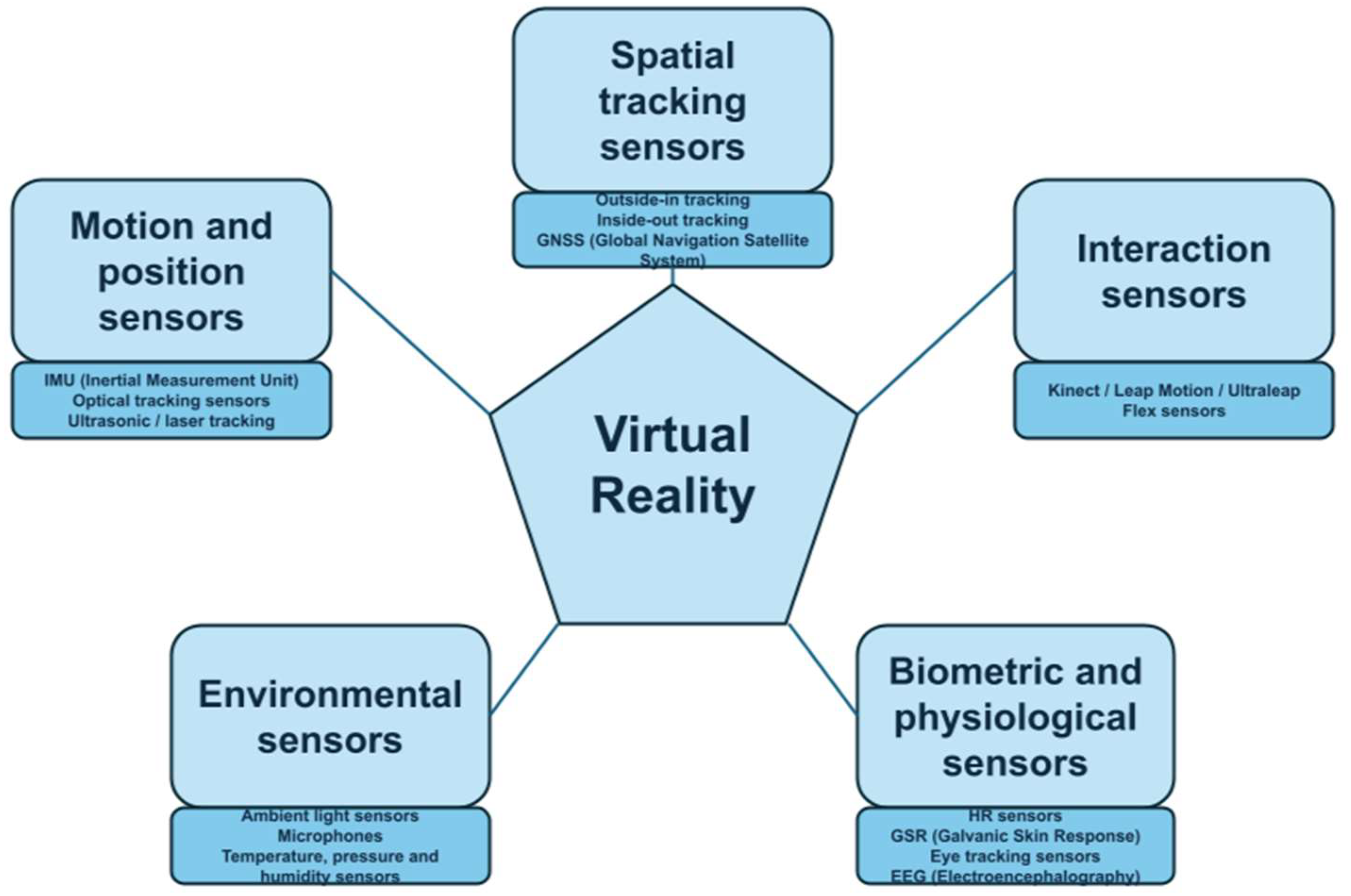

4.2. Sensor Technologies as Enablers of Immersive VR Applications

4.3. The Future of VR Technology and Further Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maples-Keller, J.L.; Bunnell, B.E.; Kim, S.-J.; Rothbaum, B.O. The Use of Virtual Reality Technology in the Treatment of Anxiety and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 25, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzałkowski, P.; Bęś, P.; Szóstak, M.; Napiórkowski, M. Application of Virtual Reality (VR) Technology in Mining and Civil Engineering. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.M.; Naz, A.; Churi, P.; Tahanzadeh, M.M. Virtual Reality as Pedagogical Tool to Enhance Experiential Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 7061623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Wang, J.; Chi, H.-L.; Wang, X. A Critical Review of the Use of Virtual Reality in Construction Engineering Education and Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.; Pesyridis, A.; Dalaymani-Zad, D.; Gronfula, M.; Kourmpetis, M. The Application of Virtual Reality in Engineering Education. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. Virtual Reality in Engineering Education. SHS Web. Conf. 2023, 157, 02001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdörfer, S.; Banakou, D.; Bhargava, A. Editorial: The light and dark sides of virtual reality. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 1200156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Gatersleben, B.; Wyles, K.J.; Ratcliffe, E. The use of virtual reality in environment experiences and the importance of realism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipresso, P.; Giglioli, I.A.C.; Raya, M.A.; Riva, G. The Past, Present, and Future of Virtual and Augmented Reality Research: A Network and Cluster Analysis of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, M.; Leye, S.; Popov, A. Virtual Reality Models and Digital Engineering Solutions for Technology Transfer. Appl. Comput. Syst. 2015, 17, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Kou, Z.; Zhu, A.; Yao, D. Effect of virtual reality technology on the teaching of urban railway vehicle engineering. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2021, 29, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, M. VR/AR Environment for Training Students on Engineering Applications and Concepts. Artif. Intell. Robot. Dev. J. 2022, 2, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariš, L.; Fanfarová, A. Modern Training Process in Safety and Security Engineering. Key Eng. Mater. 2017, 755, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, S.P.; Hartmann, M.; Christen, J.; Mayer, B.; Mast, F.W.; Weibel, D. Increasing awareness of climate change with immersive virtual reality. Front. Virtual Real. 2023, 4, 897034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lanzo, J.A.; Valentine, A.; Sohel, F.; Yapp, A.Y.T.; Muparadzi, C.M.; Abdelmalek, M. A review of the uses of virtual reality in engineering education. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2020, 28, 748–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bęś, P.; Strzałkowski, P. Analysis of the Effectiveness of Safety Training Methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, S.; Kester, L.; Van Gerven, T. An immersive virtual reality learning environment with CFD simulations: Unveiling the Virtual Garage concept. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 1455–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, B.M.; Saxena, N.; Posadzki, P.; Vsereckova, J.; Nikolaou, C.K.; George, P.P.; Divakar, U.; Masiello, I.; Kononowicz, A.A.; Zary, N.; et al. Virtual Reality for Health Professions Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2019, 21, e12959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, N. Applications of Virtual Reality Technologies in Architecture and in Engineering. Int. J. Space Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 3, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stothard, P.; Laurence, D. Application of a large-screen immersive visualisation system to demonstrate sustainable mining practices principles. Min. Technol. 2014, 123, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, D. Virtual Reality and Its Applications in Mining Industry. J. Mines Met. Fuels 2014, 62, 184–195. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.; Lu, G. Research on key techniques of virtual reality applied in mining industry. J. Coal. Sci. Eng. China 2009, 15, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.; Lienhart, W. 3D concept creation of permanent geodetic monitoring installations and the a priori assessment of systematic effects using Virtual Reality. J. Appl. Geod. 2023, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlah, D.; Čok, V.; Urbas, U. VR as a 3D Modelling Tool in Engineering Design Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Galindo, V.D.; Velado-Cano, M.A.; Groat-Carmona, A.M. The Ecology of Climate Change: Using Virtual Reality to Share, Experience, and Cultivate Local and Global Perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, T.; Richards, A.E.; Jenny, B.; Dickson, F.; Huang, J.; Klippel, A.; Neylan, M.; Wang, F.; Prober, Z.M. Immersive landscapes: Modelling ecosystem reference conditions in virtual reality. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyka, F.; Nickel, P.; Rebelo, F.; Lux, A.; Grabowski, A. Editorial: Use of AR/MR/VR in the context of occupational safety and health. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1528804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorgie, D.; Feng, Z.; Paes, D.; Parisi, F.; Yiu, T.W.; Lovreglio, R. Virtual reality for safety training: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2024, 171, 106372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, R.; Russo-Abegão, F.; Glassey, J. VR-based health and safety training in various high-risk engineering industries: A literature review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomarasca, M.A. Basics of geomatics. Appl. Geomat. 2010, 2, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, D.; Shen, X.; Wang, L. Connected Geomatics in the big data era. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2018, 11, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, J.; Lee, S.; Kwon, S.; Hamacher, A. Image Based 3D Reconstruction of Texture-less Objects for VR Contents. Int. J. Adv. Smart Converg. 2017, 6, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fink, M.C.; Sosa, D.; Eisenlauer, V.; Ertl, B. Authenticity and interest in virtual reality: Findings from an experiment including educational virtual environments created with 3D modeling and photogrammetry. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 969966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadavecchia, C.; Belcore, E.; Di Pietra, V.; Grasso, N. A Combination of Geomatic Techniques for Modelling the Urban Environment in Virtual Reality. In Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management; Grueau, C., Rodrigues, A., Ragia, L., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 2107, pp. 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verykokou, S.; Ioannidis, C. An Overview on Image-Based and Scanner-Based 3D Modeling Technologies. Sensors 2023, 23, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresani, A.; Remondino, F. Videogrammetry vs Photogrammetry for Heritage 3d Reconstruction. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W15, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak-Zimroz, J.; Krupa-Kurzynowska, J.; Kasza, D.; Trybała, P.M.; Wajs, J. Optimizing the Control of Resources in Open-Pit Mining at the Mikoszow Granite Deposit Using Lidar and Photogrammetry Techniques. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4733657 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Trybała, P. LiDAR-based Simultaneous Localization and Mapping in an underground mine in Złoty Stok, Poland. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 942, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skondras, A.; Karachaliou, E.; Tavantzis, I.; Tokas, N.; Valari, E.; Skalidi, I.; Bouvet, G.A.; Stylianidis, E. UAV Mapping and 3D Modeling as a Tool for Promotion and Management of the Urban Space. Drones 2022, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pinquié, R.; Polette, A.; Carasi, G.; Di Charnace, H.; Pernot, J.-P. Automatic 3D CAD models reconstruction from 2D orthographic drawings. Comput. Graph. 2023, 114, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diara, F.; Rinaudo, F. From Reality to Parametric Models of Cultural Heritage Assets for HBIM. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W15, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargas, A.; Loumos, G.; Varoutas, D. Using Different Ways of 3D Reconstruction of Historical Cities for Gaming Purposes: The Case Study of Nafplio. Heritage 2019, 2, 1799–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Feng, H.-Y.; Gao, S. Variational Direct Modeling: A framework towards integration of parametric modeling and direct modeling in CAD. Comput. Des. 2022, 157, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, F.; Chiappini, S.; Gorreja, A.; Balestra, M.; Pierdicca, R. Mobile 3D scan LiDAR: A literature review. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 2387–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, T.; Hashim, F.H.; Huddin, A.B.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Hussain, A. A Survey on LiDAR Scanning Mechanisms. Electronics 2020, 9, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebuňa, P.; Mizerák, M.; Rosocha, L. 3d Scaning—Technology and Reconstruction. Acta Simulatio 2018, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, B.; Ghosh, S. Airborne LiDAR Technology: A Review of Data Collection and Processing Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. A Phys. Sci. 2017, 87, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, S.; Bartholomeus, H.; Calders, K.; Lejeune, P. Forest inventory with terrestrial LiDAR: A comparison of static and hand-held mobile laser scanning. Forests 2016, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budei, B.C.; St-Onge, B.; Hopkinson, C.; Audet, F.A. Identifying the genus or species of individual trees using a three-wavelength airborne lidar system. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 204, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehr, A.; Lohr, U. Airborne laser scanning—An introduction and overview. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 1999, 54, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Yan, G.; Wang, Y.; Yan, T.; Niu, R.; Tang, C. Construction of a Real-Scene 3D Digital Campus Using a Multi-Source Data Fusion: A Case Study of Lanzhou Jiaotong University. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Rottok, L.T.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, J.; Qi, Z. VR map construction for orchard robot teleoperation based on dual-source positioning and sparse point cloud segmentation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.A.; Tronti, G.; Peruzzo, R.S.; García-Rodríguez, M.; Fazio, E.; Zucali, M.; Bollati, I.M. Geoscience popularisation in Geoparks: A common workflow for digital outcrop modelling. Comput. Geosci. 2025, 201, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huesca-Tortosa, J.A.; Spairani-Berrio, Y.; Saura-Gómez, P. Use of LiDAR Technology for the Study and Analysis of Construction Phases and Deformations in the Gothic Church of Biar (Spain). Heritage 2023, 7, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R.; Kumar, L.; Khan, I.H. Exploring the potential of 3D scanning in Industry 4.0: An overview. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2022, 3, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinos, V.; Farmakis, I.; Chatzitheodosiou, T.; Papouli, D.; Theodoropoulos, T.; Athanasoulis, D.; Kalavria, E. Engineering Geological Mapping for the Preservation of Ancient Underground Quarries via a VR Application. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Peng, C.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H. Research on the 3D Reconstruction and Intelligent Interactive Display of Traditional Stilted Buildings in Guangxi. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Intelligent Design (ICID), Xi’an, China, 25–27 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Zheng, E. UAV Geo-Localization Dataset and Method Based on Cross-View Matching. Sensors 2024, 24, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltner, A.; Kaiser, A.; Castillo, C.; Rock, G.; Neugirg, F.; Abellán, A. Image-based surface reconstruction in geomorphometry—Merits, limits and developments. Earth Surf. Dynam. 2016, 4, 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglhaut, J.; Cabo, C.; Puliti, S.; Piermattei, L.; O’Connor, J.; Rosette, J. Structure from Motion Photogrammetry in Forestry: A Review. Curr. For. Rep. 2019, 5, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Wackrow, R.; Meng, F.-R.; Lobb, D.; Li, S. Assessing the Accuracy and Feasibility of Using Close-Range Photogrammetry to Measure Channelized Erosion with a Consumer-Grade Camera. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; Barazzetti, L.; Nex, F.; Scaioni, M.; Sarazzi, D. UAV Photogrammetry for Mapping and 3d Modeling—Current Status and Future Perspectives. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2012, XXXVIII-1/C22, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, H. Research on Multi-View 3D Reconstruction Technology Based on SFM. Sensors 2022, 22, 4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrile, V.; Genovese, E. GIS-Like environments and HBIM integration for ancient villages management and dissemination. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 48, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; El-Hakim, S. Image-based 3D modelling: A review. Photogramm. Rec. 2006, 21, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesas-Carrascosa, F.J.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Clavero-Rumbao, I.; García-Ferrer, A.; Peña, J.M.; Borra-Serrano, I.; López-Granados, F. Assessing optimal flight parameters for generating accurate multispectral orthomosaicks by UAV to support site-specific crop management. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 12793–12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, T. Close range photogrammetry for industrial applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2010, 65, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Haider, H.u.D.; Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Fu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, S.; Ni, W.; Hitch, M. Mapping, Modeling and Designing a Marble Quarry Using Integrated Electric Resistivity Tomography and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Study of Adaptive Decision-Making. Drones 2025, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condorelli, F.; Bonetto, J. 3D Digitalization and Visualization of Archaeological Artifacts with the Use of Photogrammetry and Virtual Reality System. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2022, XLVIII-2/W1-2022, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caciora, T.; Herman, G.V.; Ilieș, A.; Baias, Ș.; Ilieș, D.C.; Josan, I.; Hodor, N. The Use of Virtual Reality to Promote Sustainable Tourism: A Case Study of Wooden Churches Historical Monuments from Romania. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, F.; Tataru, M.; Hua, M.T.; Johansson, I.J.S.; Andone, D. Gamifying Cultural Immersion: Virtual Reality (VR) and Mixed Reality (MR) in City Heritage. IEEE Trans. Games 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Medina-Alcaide, M.Á.; Intxaurbe, I.; Rivero, O.; Rios-Garaizar, J.; Arriolabengoa, M.; Ruiz-López, J.F.; Garate, D. Scientific virtual reality as a research tool in prehistoric archaeology: The case of Atxurra Cave (northern Spain). Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalacska, M.; Arroyo-Mora, J.P.; Lucanus, O. Comparing UAS LiDAR and Structure-from-Motion Photogrammetry for Peatland Mapping and Virtual Reality (VR) Visualization. Drones 2021, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nex, F.; Remondino, F. UAV for 3D mapping applications: A review. Appl. Geomat. 2014, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkas, D.; Chiampi, J.; Fioti, J.; Gaffney, D. Surveying Reality (SurReal): Software to Simulate Surveying in Virtual Reality. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.; Tuttle, A.J.; Johnsen, K.; Durham, S.; Baffour, R. Collaborative Virtual Reality Training Experience for Engineering Land Surveying. In Cross Reality and Data Science in Engineering; Auer, M.E., May, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1231, pp. 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.; Shults, R.; Habibi, R.; An, Z.; Roland, W. Geospatial Virtual Reality for Cyberlearning in the Field of Topographic Surveying: Moving Towards a Cost-Effective Mobile Solution. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkas, D.; Chiampi, J.; Chapman, J.; Fioti, J.; Pavill Iv, V.F. Creating Immersive and Interactive Surveying Laboratories in Virtual Reality: A Differential Leveling Example. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, V-5–2020, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Guangjun, W.; Xiaoxiao, Z. Design and Implementation of Virtual Reality Classroom of Surveying and Mapping Geographic Information Technology Based on Web GIS. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers (IPEC), Dalian, China, 14–16 April 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunmoye, I.; May, D.; Hunsu, N. An Exploratory Study of Social Presence in a Collaborative Desktop Virtual Reality (VR) Land Surveying Task. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Uppsala, Sweden, 8–11 October 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençtürk, İ.Ç.; Erkek, B.; Ayyıldız, E. Integrating Photogrammetric 3D City Models into Virtual Reality: A Methodological Approach Using Unreal Engine. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, XLVIII-M-6–2025, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, K.; Landa, M. Using Virtual and Augmented Reality with GIS Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, A.C.F.; Eve, S.J. Fire for Zeus: Using Virtual Reality to explore meaning and experience at Mount Kasios. World Archaeol. 2020, 52, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubekis, G.; Jansen, M.; Jarke, M. Cultural Master Plan Bamiyan (Afghanistan)—A Process Model for the Management of Cultural Landscapes Based on Remote-Sensing Data. In Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection, Proceedings of the 8th International Conference, EuroMed 2020, Virtual Event, 2–5 November 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Ioannides, M., Fink, E., Cantoni, L., Champion, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartini, G.A.J.; Gumilar, I.; Abidin, H.Z.; Yondri, L.; Nugany, M.R.N.; Saputri, N.D. Exploring the Potential of Terrestrial Laser Scanning for Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Study at Barong Cave in West Java, Indonesia. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-M-2–2023, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanga, C.; Banfi, F.; Roascio, S. Enhancing Building Archaeology: Drawing, UAV Photogrammetry and Scan-to-BIM-to-VR Process of Ancient Roman Ruins. Drones 2023, 7, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisi, D.; Botta, S.; Cannata, A. Integrated Surveying, from Laser Scanning to UAV Systems, for Detailed Documentation of Architectural and Archeological Heritage. Drones 2023, 7, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, E.E.; Kavroudakis, D.; Agelada, A.; Zouros, N.; Soulakellis, N.; Kasapakis, V. Virtual reality in geoeducation: The case of the Lesvos Geopark. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 33, 1653–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Salandra, A.; Frajberg, D.; Fraternali, P. A virtual reality application for augmented panoramic mountain images. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L.M.; Jurado, J.M.; Ruiz, J.L.L.; Feito, F.R. Topological data models for virtual management of hidden facilities through digital reality. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 62584–62600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napiórkowski, M.; Szóstak, M.; Schabowicz, K.; Klimek, A. Use of modeling, BIM technology, and virtual reality in nondestructive testing and inventory, using the example of the Trzonolinowiec. Open Eng. 2025, 15, 20240099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkosova, I.; Reisinger, J.; Kaufmann, H.; Kovacic, I. BIMFlexi-VR: A Virtual Reality Framework for Early-Stage Collaboration in Flexible Industrial Building Design. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 782169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Roupé, M. Real-world applications of BIM and immersive VR in construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tini, M.A.; Forte, A.; Girelli, V.A.; Lambertini, A.; Roggio, D.S.; Bitelli, G.; Vittuari, L. Scan-to-HBIM-to-VR: An Integrated Approach for the Documentation of an Industrial Archaeology Building. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sheng, F. Research on Visualization and Virtual Reality Technology of Road and Bridge Engineering Based on BIM+ GIS Technology. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Symposium on Smart and Healthy Cities (ISHC), Hainan, China, 16–17 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans-Galli, L.M.; Vela-Coiffier, M.P.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, R.V.; Ballinas-González, R. Comparing the Use of Virtual Models vs. Fieldwork in Developing Geomatics Skills in Undergraduate Engineering Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2023 Future of Educational Innovation-Workshop Series Data in Action, Monterrey, Mexico, 16–18 January 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fino, M.; Ceppi, C.; Fatiguso, F. Virtual tours and informational models for improving territorial attractiveness and the smart management of architectural heritage: The 3d-imp-act project. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 44, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Segura, Á.; Zlatanova, S.; Posada, J.; García-Alonso, A. Benefit of the integration of semantic 3D models in a fire-fighting VR simulator. Appl. Geomat. 2012, 4, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, Y. Performance Comparison of User Interface Devices for Controlling Mining Software in Virtual Reality Environments. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squelch, A. Virtual reality for mine safety training in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metal 2001, 101, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk, E.; De Villiers, R. Virtual reality training applications for the mining industry. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Graphics, Virtual Reality, Visualisation and Interaction in Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 4–6 February 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram, S.; Perez, P.; Palmisano, S. Evaluating the influence of virtual reality–based training on workers’ competencies in the mining industry. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Modelling and Applied Simulation (MAS 2014), New York, NY, USA, 10–12 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pedram, S.; Perez, P.; Palmisano, S.; Farrelly, M. The application of simulation (Virtual Reality) for safety training in the context of mining industry. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Congress on Modelling and Simulation (MODSIM 2017), Hobart, Australia, 3–8 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pedram, S.; Perez, P.; Palmisano, S.; Farrelly, M. Evaluating 360-Virtual Reality for Mining Industry’s Safety Training. In HCI International 2017—Posters’ Extended Abstracts, Proceedings of the 19th International Conference, HCI International 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; Stephanidis, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 713, pp. 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, X. Framework for a closed-loop cooperative human Cyber-Physical System for the mining industry driven by VR and AR: MHCPS. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, S.; Wang, X. A digital smart product service system and a case study of the mining industry: MSPSS. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Head-mounted display-based intuitive virtual reality training system for the mining industry. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, G.; Tuberga, B.; Chiaberge, M. Advancing lunar exploration through virtual reality simulations: A framework for future human missions, 2024. In Proceedings of the IAF Space Systems Symposium, Milan, Italy, 14–18 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, T.; Egger, J. Augmented reality in support of Industry 4.0—Implementation challenges and success factors. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2019, 58, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürer, S.; Surer, E.; Erkayaoğlu, M. MINING-VIRTUAL: A comprehensive virtual reality-based serious game for occupational health and safety training in underground mines. Saf. Sci. 2013, 166, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, A.; Jankowski, J. Virtual Reality-based pilot training for underground coal miners. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Kaiser, P.; Cotesta, L.; Dasys, A. Planning and design of underground engineerings utilizing common earth model and immersive virtual reality. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2006, 25, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz, T.P.; Caris, C.; Thompson, J.; Wesner, C.; Dunn, M. Human-Computer Interaction Experiments Immersive Virtual Reality Applications for the Mining Industry. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 24th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Perth, Australia, 20–23 April 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozmus, M.; Tokarczyk, J.; Michalak, D.; Dudek, M.; Szewerda, K.; Rotkegel, M.; Lamot, A.; Rošer, J. Application of 3D Scanning, Computer Simulations and Virtual Reality in the Redesigning Process of Selected Areas of Underground Transportation Routes in Coal Mining Industry. Energies 2021, 14, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, M.G.; Wanasinghe, T.R.; Gosine, R.G.; Warrian, P.J. Digital Twins and Enabling Technology Applications in Mining: Research Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 6945–6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhu, L.; Weng, L.; Gu, X. The More Advanced, the Better? A Comparative Analysis of Interpretation Effectiveness of Different Media on Environmental Education in a Global Geopark. Land 2024, 13, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plechatá, A.; Morton, T.; Makransky, G. Promoting collective climate action and identification with environmentalists through social interaction and visual feedback in virtual reality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 102, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, M.H.C.; Lemmens, J.S.; Lu, Y.; Newman-Grigg, E.R.; Lan, X.; Blanken, T.; Hendriks, H. Let’s talk about climate change: How immersive media experiences stimulate climate conversations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 104, 102610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditrich, L.; Lachmair, M. A ‘front-row seat’ to catastrophe: Testing the effect of immersive technologies on sympathy and pro-environmental behavior in the context of rising sea levels. Environ. Educ. Res. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.H.; Annetta, L.A. The Influence of Extended Reality on Climate Change Education. Sci. Educ. 2025, 34, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikov, S.; Svitek, M. Integrating Challenge-Based Learning and Virtual Reality Representation in Smart City Education Program. In EATIS 2024, Proceedings of the 12th Euro American Conference on Telematics and Information Systems, Praia, Cape Verde, 3–5 July 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ferreira, A. Virtual reality is only mildly effective in improving forest conservation behaviors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, D.; Wolf, P.; Kaspar, K. Virtual reality versus classic presentations of mass media campaigns: Effectiveness and psychological mechanisms using the example of environmental protection. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 168, 108643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, M.; Wang, P.; Han, E.; Bailenson, J. Virtual reality reduces climate indifference by making distant locations feel psychologically close. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Heimes, A.; Masullo, M.; Maffei, L.; Kim, Y.-H.; Lee, P.-J.; Vorländer, M. Impact of spatial factors of environmental sounds on psychological and physiological responses: A virtual reality study on direction and distance. Build. Environ. 2026, 287, 113777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, D. Immersive visualization in infrastructure planning: Enhancing long-term resilience and sustainability. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, E.; Torres, R.D.; Weingartner, L.; de Paleville, D.T. Virtual reality breaks for stress reduction among graduate and dental students. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2025, 49, 1070–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, N.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, J.; Duan, H.; Gao, W. The impact of virtual images of coastal landscape features on stress recovery based on EEG. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, W.M.; Spanlang, B.; Nowak, A.; Talaga, S.; Zurera, M.J.P.; Ganza, R.P.; Boros, A.; Bartkowski, W.; Ziembowicz, K.; Biesaga, M. Cooperation for environmental sustainability—A common pool resource virtual experience. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Saint Malo, France, 8–12 March 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavouras, I.; Rallis, I.; Sardis, E.; Protopapadakis, E.; Doulamis, A.; Doulamis, N. Empowering Communities Through Gamified Urban Design Solutions. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, P.; Weidhaas, R. Immersive VR-Driven Landscapes: Exploring Climate-Adaptive Ecosystem Design. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsswey, A.; El-Qirem, F.A.; Aldowah, H.A.; Ghazal, S. Utilizing Eye-Tracking Technology to Investigate Architectural Elements in Building Design. In Artificial Intelligence in Business, Proceedings of the SICB 2025, Amman, Jordan, 21–23 April 2025; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Conference on Sustainability and Cutting-Edge Business Technologies; Alshehadeh, A.R., El-Qirem, I.A., Ghaleb Awad Elrefae, G.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, O.; Ariza-Sentís, M.; Vélez, S. Enhancing Education in Agriculture via XR-Based Digital Twins: A Novel Approach for the Next Generation. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, Q.; Du, Z.; Zhang, M. Energy-Efficient Dynamic Street Lighting Optimization: Balancing Pedestrian Safety and Energy Conservation. Buildings 2025, 15, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak-Zimroz, J.; Romańczukiewicz, K.; Sitarska, M.; Szrek, A. Light-pollution-monitoring method for selected environmental and sovial elements. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundrakpam, B.; Segado, M.; Pazdera, J.; Shaigetz, V.G.; Granek, J.A.; Choudhury, N. An Integrated Platform Combining Immersive Virtual Reality and Physiological Sensors for Systematic and Individualized Assessment of Stress Response (bWell): Design and Implementation Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2025, 9, e64492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-García, M.; Rodríguez, M.; Pérez, L.M. Virtual reality as a driver of sustainable tourism. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjostheim, I.; Simon-Liedtke, J.T. Experiencing Digital Travel vs. Substituting Physical Travel with Digital Travel—On Intention to Use Digital Travel Applications in the Future. In Extended Reality, Proceedings of the XR Salento 2025, Otranto, Italy, 17–20 June 2025; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; De Paolis, L.T., Arpaia, P., Sacco, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriani, S.S.; Nuswantara, D.A.; Nugrohoseno, D.; Sukardani, P.S.; Kartika, A.D.; Junianta, R.D.; Hasanah, I.A.W. From virtual views to visit intention: The role of 360-video in promoting tourist destination. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2025, 8, 2026098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, A.; Fujimoto, S.; Ishikawa, R.; Tanaka, A. Virtual reality training for radiation safety in cardiac catheterization laboratories—An integrated study. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2024, 200, 1462–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqallaf, N.; Ghannam, R. Immersive Learning in Photovoltaic Energy Education: A Comprehensive Review of Virtual Reality Applications. Solar 2024, 4, 136–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeaino, G.; Brophy, P.; Gheisari, M.; Issa, R.R.A.; Jeelani, I. Working with Drones: Design and Development of a Virtual Reality Safety Training Environment for Construction Workers. In Computing in Civil Engineering 2021; Issa, R.R.A., Ed.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 1335–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, E.; Albeaino, G.; Brophy, P.; Gheisari, M.; Jeelani, I. Working Safely with Drones: A Virtual Training Strategy for Workers on Heights. In Construction Research Congress 2022; Jazizadeh, F., Shealy, T., Garvin, M.J., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehrt, J.; Rafati, M.; Cheema, C.; Garofano, D.; Hristova, D.; Jäger, E.; Schwing, V. Auto-REBA: Improving postural ergonomics using an automatic real-time REBA score in virtual reality. Gerontechnology 2024, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, D.; Schwarz, M.; Meixner, G. Improving ergonomic training using augmented reality feedback. In Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management, Proceedings of the 14th International Conference, DHM 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023; Duffy, V.G., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14028, pp. 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, M.; Puro, V.; Tiikkaja, M.; Kannisto, H.; Lantto, E.; Simpura, F.; Uusitalo, J.; Lukander, K.; Räsänen, T.; Teperi, A.-M. Evaluation of the efficacy of a virtual reality-based safety training and human factors training method: Study protocol for a randomised-controlled trial. Inj. Prev. 2020, 26, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pira, E.; Patrucco, M.; Nebbia, R.; Pienri, P.; Graziano, D.; Godono, A.; Gullino, A. Results of the implementation of a virtual control approach to improve the effectiveness and quality of Safety and Health inspections at workplaces: [Risultati dell’implementazione di un approccio di controllo virtuale per migliorare l’efficacia e la qualità delle ispezioni in materia di sicurezza e salute sui luoghi di lavoro]. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2022, 44, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiris, R.; Jain, A.; Gheisari, M.; Wehle, A. Safety immersive storytelling using narrated 360-degree panoramas: A fall hazard training within the electrical trade context. Saf. Sci. 2020, 127, 104703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkoong, K.; Leach, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Weichelt, B. A feasibility study of Augmented Reality Intervention for Safety Education for farm parents and children. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 903933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, V.; Chauhan, J.S. Digital Twin Approach for the Ergonomic Evaluation of Vertical Formwork Operations in Construction. In Proceedings of the 2023 Proceedings of the 40th ISARC, Chennai, India, 5–7 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Shafiq, M.T. Evaluating 4D-BIM and VR for Effective Safety Communication and Training: A Case Study of Multilingual Construction Job-Site Crew. Buildings 2021, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J. Industrial applications of virtual reality in architecture and construction. Electron. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2003, 8, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dodoo, J.E.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Alzahrani, A.I.; Tang, T. XR and Workers’ safety in High-Risk Industries: A comprehensive review. Saf. Sci. 2025, 185, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. A Review on Using Opportunities of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality in Construction Project Management. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2019, 11, 1839–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, N.K.B.; Anani, A.; Adewuyi, S.O. Review of Virtual Reality Integration for Safer and Efficient Mining Operations. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 34177–34199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Wu, S.; Zhang, G.; Tan, Y.; Wang, X. Literature Review of Digital Twins Applications in Construction Workforce Safety. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kim, J.; Ham, Y. Multi-user immersive environment for excavator teleoperation in construction. Autom. Constr. 2023, 156, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xing, J.; Xiong, R.; Tang, P. Sharing Construction Safety Inspection Experiences and Site-Specific Knowledge through XR-Augmented Visual Assistance. In Proceedings of the ICRA 2022 Future of Construction Workshop Papers, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahian Jahromi, B.; Tulabandhula, T.; Cetin, S. Real-Time Hybrid Multi-Sensor Fusion Framework for Perception in Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2019, 19, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fan, D.; Deng, Y.; Lei, Y.; Omalley, O. Sensor fusion-based virtual reality for enhanced physical training. Robot. Intell. Autom. 2024, 44, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.W.; Park, J.S.; Park, H.J. Understanding VR-Based Construction Safety Training Effectiveness: The Role of Telepresence, Risk Perception, and Training Satisfaction. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyade, M.; Eaglesham, C.; Trench, J.; Reid, M. A transferable psychological evaluation of virtual reality applied to safety training in chemical manufacturing. ACS Chem. Health Saf. 2021, 28, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardecani, F.B.; Shoghli, O. Assessing workers’ neuro-physiological stress responses to augmented reality safety warnings in immersive virtual roadway work zones. Autom. Constr. 2025, 180, 106565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, S.S.; Helle, N.; Sletteland, N.V.; Vikman, M.D.; Bonsaksen, T. Implementation of Virtual Reality in Health Professions Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e41589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouijzer, M.M.T.E.; Kip, H.; Bouman, Y.H.A.; Kelders, S.M. Implementation of virtual reality in healthcare: A scoping review on the implementation process of virtual reality in various healthcare settings. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2023, 4, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifu, A.; Darabont, D.C.; Ciocîrlea, V.; Ivan, I. Modern training methods and technique in the field of occupational safety—A literature review. MATEC Web. Conf. 2024, 389, 00046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.; Jia, B. How Virtual Reality Technology Has Changed Our Lives: An Overview of the Current and Potential Applications and Limitations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.; Naderi, E.; Cheng, R.; Aryana, B. Adopting Immersive Technologies for Design Practice: The Internal and External Barriers. Proc. Int. Conf. Eng. Des. 2019, 1, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Layland, A. Comparison study of the use of 360-degree video and non-360-degree video simulation and cybersickness symptoms in undergraduate healthcare curricula. BMJ Simul. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2019, 5, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaseri Chandra, A.N.; El Jamiy, F.; Reza, H. A Systematic Survey on Cybersickness in Virtual Environments. Computers 2022, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaViola, J.J. A discussion of cybersickness in virtual environments. ACM SIGCHI Bull. 2000, 32, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araiza-Alba, P.; Keane, T.; Kaufman, J. Are we ready for virtual reality in K–12 classrooms? Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2022, 31, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asino, T.I.; Colston, N.M.; Ibukun, A.; Abai, C. The Virtual Citizen Science Expo Hall: A Case Study of a Design-Based Project for Sustainability Education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Alshaketheep, K.; Al-Ahmed, H.; Shajrawi, A.; Deeb, A. Public Perceptions of Ethical Challenges and Opportunities for Enterprises in the Digital Age. Ianna J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2025, 7, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Longondjo Etambakonga, C. The Rise of Virtual Reality in Online Courses: Ethical Issues and Policy Recommendations. In Factoring Ethics in Technology, Policy Making, Regulation and AI; Hessami, A.G., Shaw, P., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleda-Antonio, J.; Vargas-Montes, E.; Meneses-Claudio, B.; Auccacusi-Kañahuire, M. Application of virtual reality in simulated training for arthroscopic surgeries: A systematic literature review. EAI Endors. Trans. Pervasive Health Technol. 2023, 9, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, S.A.; Klausing, L.N.; Hill, T.M.; Kinney, A.L.; Reissman, T.; Reissman, M.E. Characterization of Upper Extremity Kinematics Using Virtual Reality Movement Tasks and Wearable IMU Technology. Sensors 2024, 24, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, P.; Laux, S.; Purdack, D.; Müller, P.N.; Göbel, S. Give Me a Sign: Using Data Gloves for Static Hand-Shape Recognition. Sensors 2023, 23, 9847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séba, M.-P.; Maillot, P.; Hanneton, S.; Dietrich, G. Influence of Normal Aging and Multisensory Data Fusion on Cybersickness and Postural Adaptation in Immersive Virtual Reality. Sensors 2023, 23, 9414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Cha, H.-S.; Kim, J.; Kwak, H.; Lee, W.; Im, C.-H. Facial Motion Capture System Based on Facial Electromyogram and Electrooculogram for Immersive Social Virtual Reality Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anheuer, D.; Karacan, B.; Herzog, L.; Weigel, N.; Meyer-Nieberg, S.; Gebhardt, T.; Freiherr, J.; Richter, M.; Leopold, A.; Eder, M.; et al. Framework for Microdosing Odors in Virtual Reality for Psychophysiological Stress Training. Sensors 2024, 24, 7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majil, I.; Yang, M.-T.; Yang, S. Augmented Reality Based Interactive Cooking Guide. Sensors 2022, 22, 8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, D.W.; McAllister, E.; Gilbert, R.; O’Higgins, C.; Lydon, D.; Lydon, M.; McPolin, D. Embedding Civil Engineering Understanding through the Use of Interactive Virtual Reality. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönsch, J.; Greif, L.; Hauck, S.; Kreuzwieser, S.; Mayer, A.; Michels, F.L.; Ovtcharova, J. Virtual Engineering: Hands-on Integration of Product Lifecycle Management, Computer-Aided Design, eXtended Reality, and Artificial Intelligence in Engineering Education. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2024, 96, 1460–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, B.; Thomas, J. Adoption of virtual reality technology in higher education: An evaluation of five teaching semesters in a purpose-designed laboratory. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1287–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignaciuk, M. Wirtualna rzeczywistość w edukacji—Analiza opinii nauczycieli na temat wykorzystania technologii VR w edukacji szkolnej. Ars Educ. 2022, 19, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarlela, T.; Padrao, P.; Pitkäaho, T.; Pieskä, S.; Bobadilla, L. Digital Twins Utilizing XR-Technology as Robotic Training Tools. Machines 2022, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdjou, H.M.; Baudry, D.; Havard, V.; Ouchani, S. Resource-Constrained EXtended Reality Operated With Digital Twin in Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 928–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzoha, A.; Toshev, R.; Vu Tuan, V.; Kankaanpaa, T.; Helo, P. Digital factory—Virtual reality environments for industrial training and maintenance. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 1339–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bęś, P.; Strzałkowski, P.; Górniak-Zimroz, J.; Szóstak, M.; Janiszewski, M. Innovative Technologies to Improve Occupational Safety in Mining and Construction Industries—Part I. Sensors 2025, 25, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bęś, P.; Strzałkowski, P.; Górniak-Zimroz, J.; Szóstak, M.; Janiszewski, M. Innovative Technologies to Improve Occupational Safety in Mining and Construction Industries—Part II. Sensors 2025, 25, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Ralescu, A.L. Future Internet Architectures on an Emerging Scale—A Systematic Review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlosky, J.; Kiyokawa, K.; Takemura, H. Virtual and Augmented Reality on the 5G Highway. J. Inf. Process. 2017, 25, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crogman, H.T.; Cano, V.D.; Pacheco, E.; Sonawane, R.B.; Boroon, R. Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, and Mixed Reality in Experiential Learning: Transforming Educational Paradigms. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Felix, R.; Hinsch, C.; Shahab, H.; Alt, F. What is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual Reality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 133, 107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.; Yap, K.M.; Lim, W.N. Haptic Interfaces for Virtual Reality: Challenges and Research Directions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 112145–112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Kim, J. A Study on Immersion of Hand Interaction for Mobile Platform Virtual Reality Contents. Symmetry 2017, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Peng, Y.; Haddouk, L.; Vayatis, N.; Vidal, P.-P. Assessing virtual reality presence through physiological measures: A comprehensive review. Front. Virtual Real. 2025, 6, 1530770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiossi, F.; Ou, C.; Gerhardt, C.; Putze, F.; Mayer, S. Designing and Evaluating an Adaptive Virtual Reality System using EEG Frequencies to Balance Internal and External Attention States. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2025, 196, 103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D. Cross Reality Spaces in Engineering Education—Online Laboratories for Supporting International Student Collaboration in Merging Realities. Int. J. Onl. Eng. 2020, 16, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Shen, H. Advantages, Challenges, and Planning of Virtual Reality Technology in Education from a Constructivist Perspective. J. Intell. Knowl. Eng. 2024, 2, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry | Keywords | Search Results | Selected Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geodesy and Geomatics | VR OR virtual reality OR geomatics OR land surveying OR geodesy OR surveying instruments OR field measurements OR total station OR GNSS OR cartography OR GIS | 2461 | 881 |

| Mining | virtual reality OR vr AND mining engineering OR mining industry OR mining operation” | 161 | 84 |

| Environmental protection | vr OR virtual reality AND ecological education OR climate change OR environmental protection | 526 | 348 |

| Occupational safety | VR OR virtual reality AND occupational safety OR safety at work OR occupational health and safety OR OHS OR OSH | 184 | 82 |

| Engineering Area | Main Application Scenarios | Core Sensor Types Relied upon | Key Technical Challenges | Future Sensor-Driven Directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geodesy and Geomatics | Training and simulation of surveying procedures/measurements for example levelling, GNSS, total station setup | motion capture systems, head movement sensors, 360° cameras, surveying instrument model | Realistic replication of field conditions | Development of training laboratories connected with sensors, attractiveness of training courses for users and feedback mechanisms |

| Geodesy and Geomatics | 3D visualization and analysis of spatial data | head movement sensors, 360° cameras, integration with Augmented Reality sensors | Integration of heterogeneous datasets, data volume and GPU constraints, loss of accuracy during mesh decimation, processing | Automation of data fusion and optimization of rendering workflows |

| Geodesy and Geomatics | Cultural heritage documentation and landscape reconstruction (visualization of archaeological or degraded sites) | motion capture systems, head movement sensors, 360° cameras | Balancing visual realism and metric precision and texture optimization | High-fidelity 3D scanning and AI-driven model reconstruction |

| Mining | Immersive training for drilling, blasting, equipment operation, and emergency evacuation procedures | IMU, motion-tracking sensors, physiological sensors (heart rate), GNSS | Sensor latency and drift affecting synchronization between user motion and simulated environment; limited realism in haptic feedback | Integration of multimodal sensor data for real-time feedback; adaptive training environments using AI-driven performance monitoring |

| Mining | Real-time visualization of underground conditions for safety assessment and ventilation management | laser tracking, temperature and humidity sensors, IoT nodes | Data fusion from heterogeneous sensors in harsh environments; unstable wireless connectivity underground | Development of digital twins integrating geospatial and sensor data; improved IoT-VR interoperability standards |

| Mining | 3D visualization and virtual prototyping of mine layouts, geological structures, and operational processes | laser tracking, photogrammetry, UAV-based imaging, GNSS | Large-scale spatial data processing; alignment errors between datasets; limited rendering capacity for complex geological models | Enhanced real-time 3D reconstruction; integration of AR/VR with BIM and GIS systems for collaborative mine planning |

| Environmental protection | Educational scenarios of climate change effects taking into account temporal and spatial distance | IMU, motion capture systems, 360° cameras, heart rate monitors, skin conductivity sensors, EEG | realistic image rendering for climate change in landscapes/urban spaces/ecosystems | assessment of cognitive and behavioural responses to presented information and images, supported by AI |

| Environmental protection | Designing urban spaces in accordance with the principles of sustainable development—visualization of possible effects | Eye-tracking, hand gesture tracking, head movement sensors | realistic representation of urban spaces and the changes introduced in them, together with a presentation of their effects in the field of urban planning | assessment of the attractiveness of new projects and proposed changes in urban space supported sensors and real-time adaptation of VR content |

| Environmental protection | Virtual training courses on sustainable agriculture | motion capture systems, 360° cameras, heart rate monitors, skin conductivity sensors, EEG | realistic representation of aspects related to sustainable agriculture | AI- and biofeedback-supported training content adapted in real time to the personalized needs of the trainee |

| Occupational safety | Interactive training in evacuation, hazard recognition, and equipment operation | IMU, motion capture systems, 360° cameras | Sensor latency, drift, and occlusion in confined environments | Sensor-based real-time adaptation of VR content during procedural safety training |

| Occupational safety | Competency diagnostics and behavioural assessment using immersive VR scenarios | Eye-tracking, hand gesture tracking, head movement sensors | Lack of standardized evaluation metrics and data interpretation frameworks | AI-supported evaluation of cognitive and behavioural responses to simulated hazards |

| Occupational safety | Physiological monitoring during stress-inducing or fatigue-relevant training | Heart rate monitors, skin conductivity sensors, EEG | Limited physiological data integration and variability across individuals | Theory-driven, biofeedback-enhanced VR training for personalized safety learning |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strzałkowski, P.; Romańczukiewicz, K.; Bęś, P.; Delijewska, B.; Sitarska, M.; Janiszewski, M. The Application of VR Technology in Engineering Issues: Geodesy and Geomatics, Mining, Environmental Protection and Occupational Safety. Sensors 2025, 25, 6848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226848

Strzałkowski P, Romańczukiewicz K, Bęś P, Delijewska B, Sitarska M, Janiszewski M. The Application of VR Technology in Engineering Issues: Geodesy and Geomatics, Mining, Environmental Protection and Occupational Safety. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226848

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrzałkowski, Paweł, Kinga Romańczukiewicz, Paweł Bęś, Barbara Delijewska, Magdalena Sitarska, and Mateusz Janiszewski. 2025. "The Application of VR Technology in Engineering Issues: Geodesy and Geomatics, Mining, Environmental Protection and Occupational Safety" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226848

APA StyleStrzałkowski, P., Romańczukiewicz, K., Bęś, P., Delijewska, B., Sitarska, M., & Janiszewski, M. (2025). The Application of VR Technology in Engineering Issues: Geodesy and Geomatics, Mining, Environmental Protection and Occupational Safety. Sensors, 25(22), 6848. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226848