AHE-FNUQ: An Advanced Hierarchical Ensemble Framework with Neural Network Fusion and Uncertainty Quantification for Outlier Detection in Agri-IoT

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

- General IoT anomaly detection, which focuses on generic detection methods applicable to a variety of IoT contexts.

- Industrial IoT (IIoT), where anomaly detection is essential for ensuring safety and operational efficiency in manufacturing and infrastructure systems.

- Agricultural IoT (Agri-IoT), a rapidly growing field in which environmental complexity, biological variability, and data sparsity create unique detection challenges.

2.1. Anomaly Detection in IoT System

2.2. Industrial IoT Anomaly Detection

2.3. Agri-IoT Systems and Anomaly Detection

2.4. Research Gaps and Limitations

2.5. Positioning of Proposed Method

3. Proposed Approach: Advanced AHE-FNUQ for Agricultural Anomaly Detection

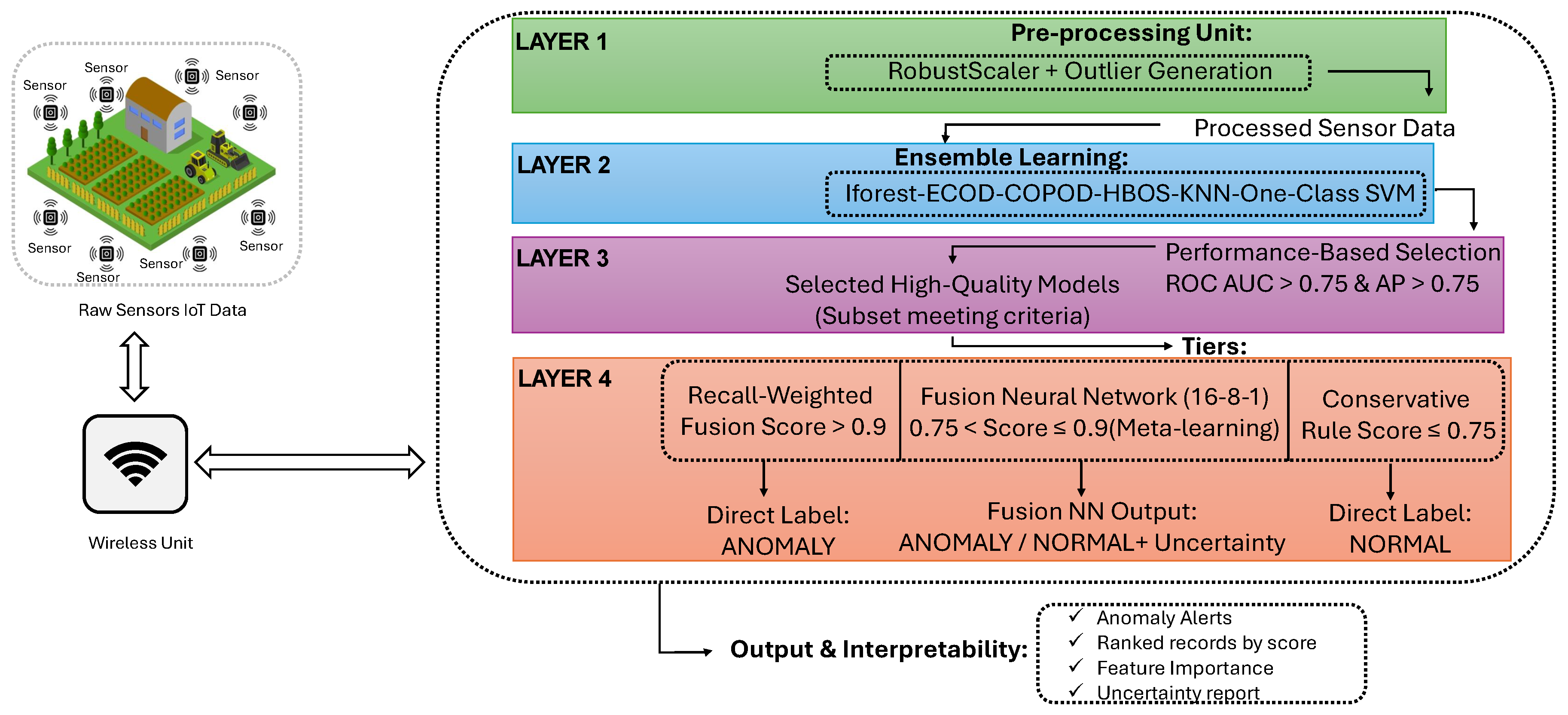

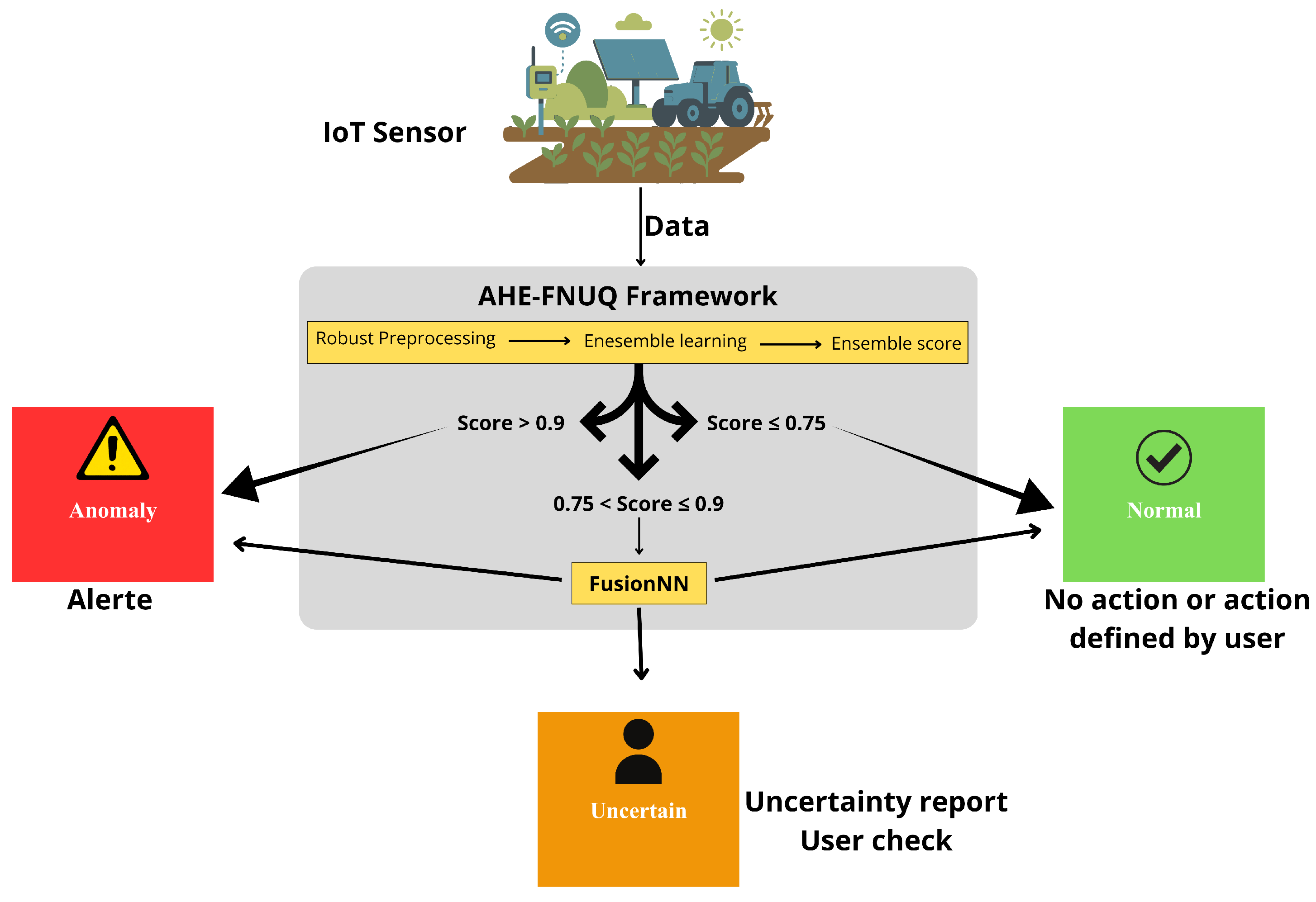

3.1. Proposed Approach: Advanced AHE-FNUQ Framework

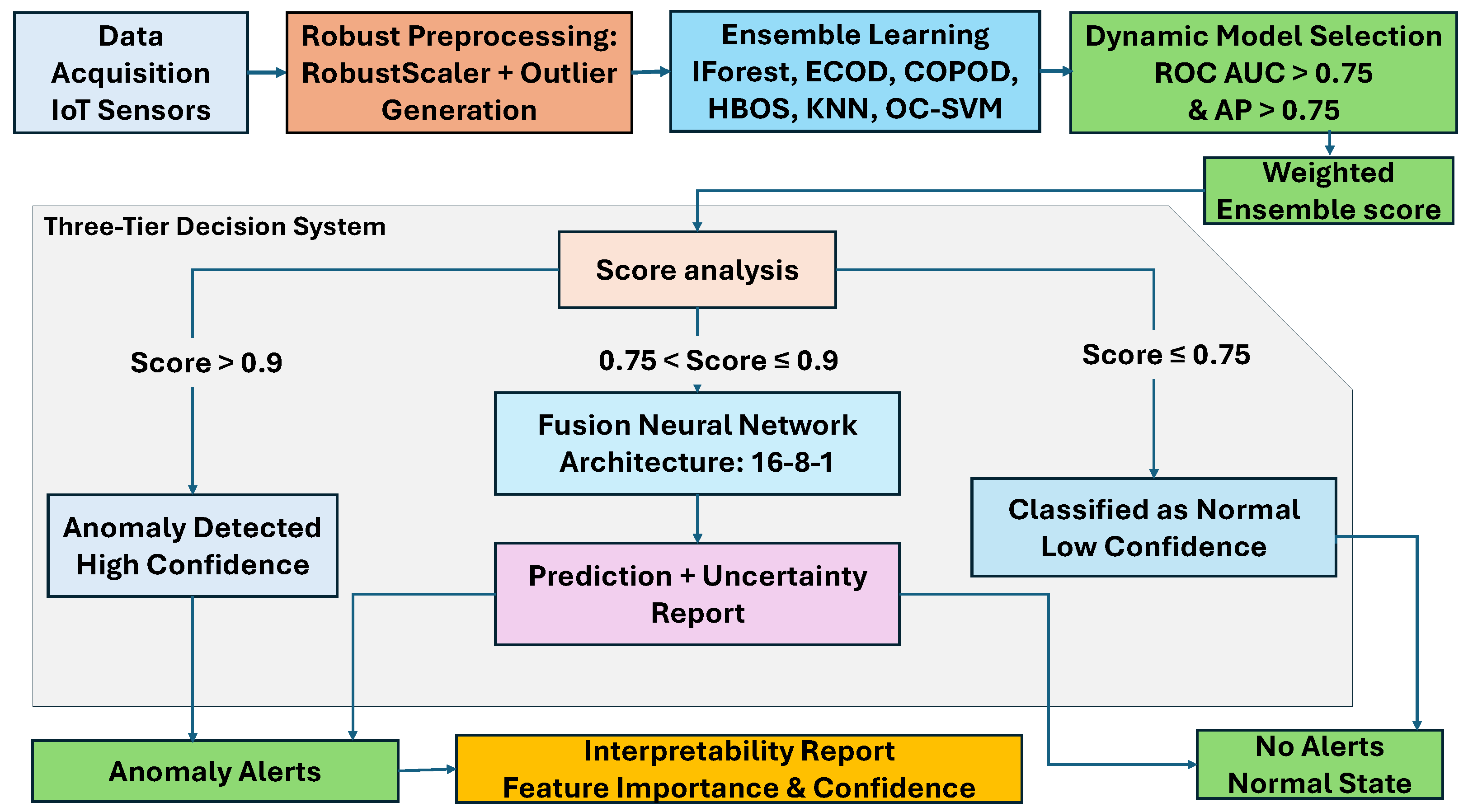

3.2. System Architecture: Step-by-Step Processing Layers

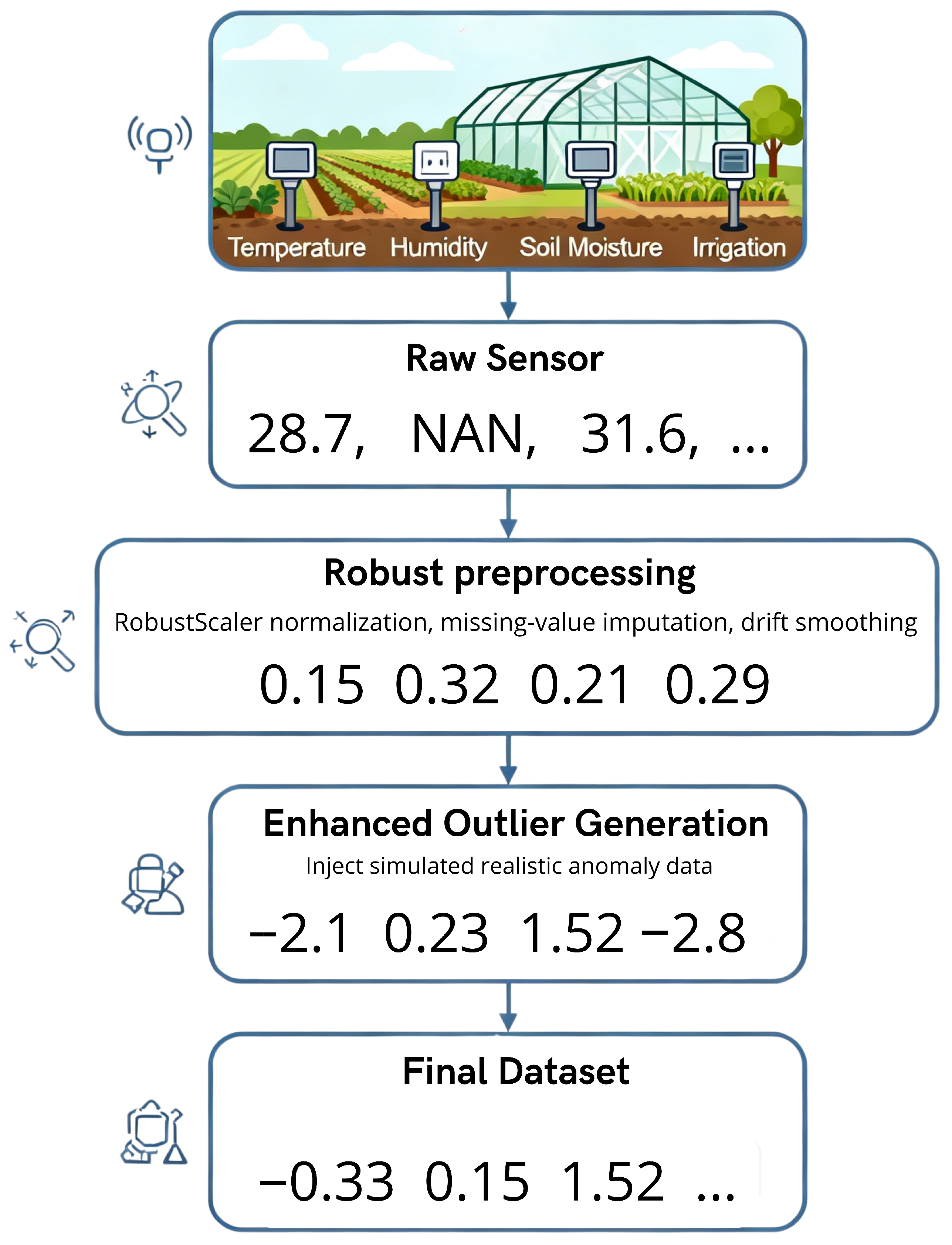

3.2.1. Layer 1: Data Input and Robust Preprocessing

- Robust Preprocessing PipelineNormalization is performed using the RobustScaler, which scales data by subtracting the median and dividing by the interquartile range (IQR), defined as the difference between the 75th percentile (Q3) and the 25th percentile (Q1). This approach reduces the influence of extreme values. In contrast, StandardScaler uses the mean and standard deviation, and MinMaxScaler relies on the minimum and maximum values.RobustScaler is selected because agricultural data frequently display substantial variabilities due to seasonal changes, weather patterns, and biological cycles. The objective of anomaly detection is to identify issues such as plant stress, pest infestations, irrigation failures, equipment malfunctions, and atypical environmental conditions, rather than only extreme outliers. StandardScaler may be affected by normal extremes, such as temperature ranges from −5 °C to 45 °C or humidity from 20% to 95%, reducing normalization effectiveness and anomaly detection performance. RobustScaler facilitates the identification of subtle abnormal patterns and provides greater stability in dynamic environments.The mathematical formulation is as follows:where . This method preserves the distinction between normal and abnormal data while ensuring effective normalization with variable agricultural data.Other statistical steps in preprocessing address sensor drift and environmental changes. Missing data is filled using robust techniques, and smoothing algorithms reduce short-term sensor noise while preserving genuine anomaly patterns.

- Enhanced Outlier Generation StrategyFor model development and evaluation, this layer integrates a dedicated outlier generation mechanism designed to simulate realistic anomaly scenarios in agricultural sensor networks. The goal is to construct labeled datasets that reflect actual failure patterns and environmental disturbances without artificially inflating detection performance.The generation process focuses on producing representative deviations based on agricultural domain characteristics. Two main categories are considered: (i) subtle anomalies, representing gradual sensor drifts or mild perturbations, and (ii) extreme anomalies, reflecting sudden sensor malfunctions or severe environmental events. Approximately 30% of anomalies affect multiple correlated features simultaneously, reflecting how malfunctions often propagate across dependent sensor measurements in real deployments.Algorithm 1 formalizes this procedure. It randomly selects a subset of sensor samples to simulate events with natural variability. Deviations are applied with magnitudes corresponding to realistic agricultural sensor behavior. No optimization or tuning is applied to favor the model; the purpose is solely to replicate real-world conditions.

| Algorithm 1 Enhanced Agricultural Outlier Generation (Realistic Simulation) |

|

3.2.2. Layer 2: Multi-Algorithm Detection Ensemble

- Base Detector Selection and Algorithmic DiversityThe ensemble comprises six detection algorithms, each chosen to address specific characteristics of anomalies in agricultural sensor data:Isolation Forest: This tree-based isolation method works well in high-dimensional spaces through random partitioning. It effectively detects global anomalies and handles mixed-type data common in agricultural sensor networks. Anomalies are isolated with fewer splits in decision trees, making IForest computationally efficient for large-scale agricultural monitoring.ECOD: A parameter-free statistical method using empirical distribution functions. ECOD performs robustly across different data types and excels at univariate outlier detection. It is computationally efficient, suitable for real-time agricultural monitoring.COPOD: This algorithm models complex multivariate data dependencies using the copula theory. It captures intricate relationships and multivariate anomalies, common in interconnected agricultural sensor networks where environmental factors exhibit complex interdependencies.HBOS: HBOS uses histogram-based probability density functions for efficient density estimation. It is suitable for large datasets and real-time processing in precision agriculture. HBOS effectively detects density-based anomalies in agricultural time-series data.KNN: This proximity-based method identifies anomalies through distance metrics in feature space. KNN is effective for detecting local density deviations and contextual anomalies within sensor clusters, such as gradual sensor drift patterns typical in agricultural environments.OC-SVM: This boundary-based method learns a hypersphere around normal data patterns. It is effective at detecting anomalies outside the normal boundaries, particularly for non-linear patterns in complex agricultural sensor data with seasonal variations.

3.2.3. Layer 3: Performance-Based Model Selection

- Dynamic Selection FrameworkSelection Criteria:

- –

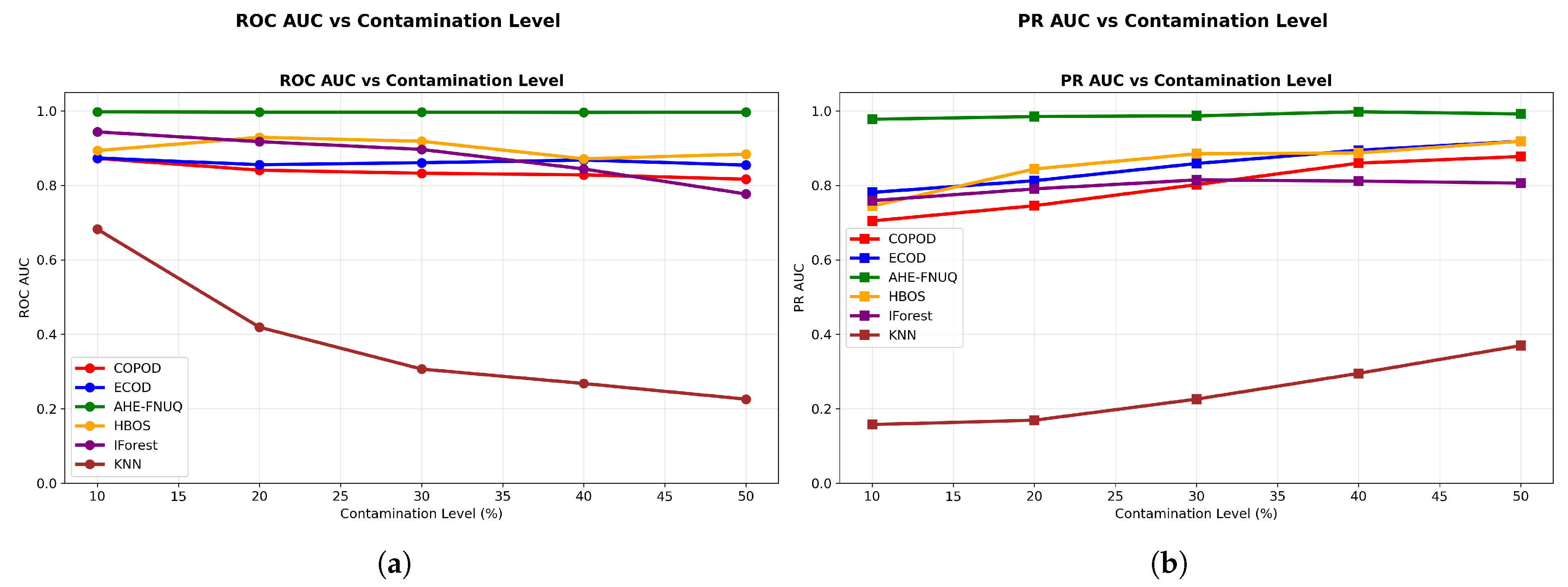

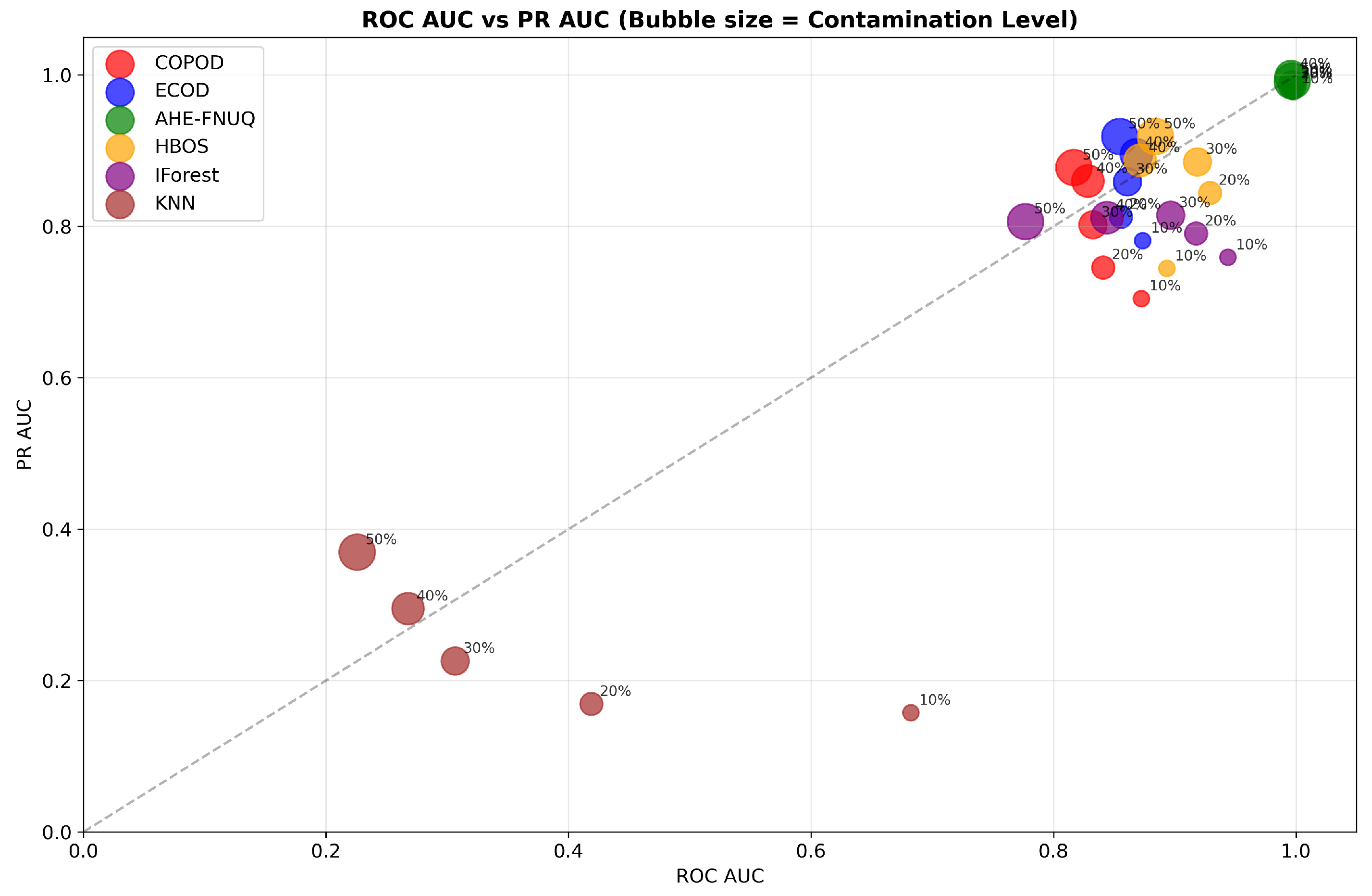

- ROC AUC : This threshold reflects a model’s strong ability to distinguish between normal and anomalous instances across different decision levels.

- –

- Average Precision Score : This threshold ensures reliable performance on imbalanced datasets, which are common in agricultural anomaly detection.

Computational Optimization: Only models that meet the established benchmarks contribute to ensemble predictions. This process improves detection accuracy and reduces computational cost, both important for real-time agricultural monitoring.Mathematical Representation:Note on Metric Selection: The average precision score is used instead of the standard PR AUC because it is more efficient to compute, easy to implement in scikit-learn, and equally effective for selecting models in imbalanced anomaly detection scenarios.

3.2.4. Layer 4: Three-Tier Hierarchical Decision System

Tier 1: High-Confidence Direct Classification (Score > 0.9)

Tier 2: Conservative Normal Classification (Score ≤ 0.75)

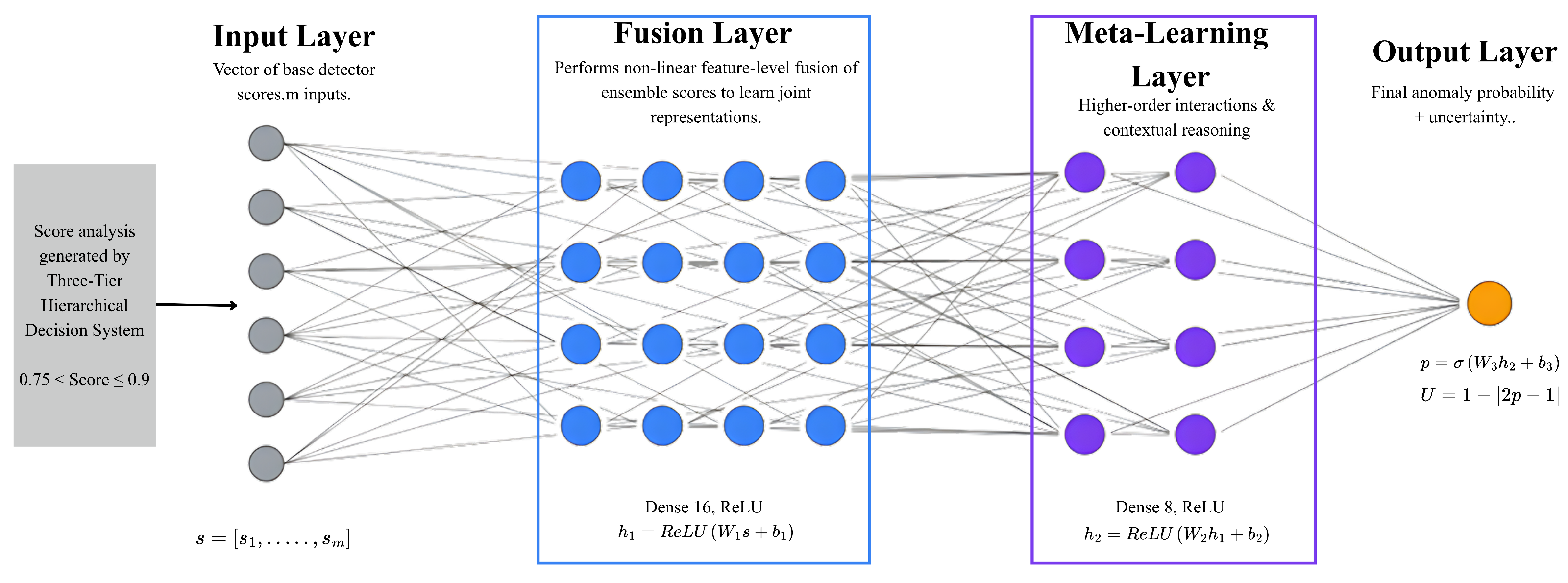

Tier 3: Neural Network Meta-Learning (0.75 < Score ≤ 0.9)

3.2.5. Layer 5: Output Generation and Interpretability

- Feature Importance and Interpretability AnalysisUnderstanding each sensor’s contribution to anomaly detection is crucial in agriculture. The framework uses permutation-based feature importance to provide interpretable results and actionable insights.Importance Calculation: Feature importance is quantified as follows:where is the ensemble score after permuting feature , breaking its relationship with the target variable.Normalized Importance: Relative contributions of features are calculated as follows:This analysis allows agricultural practitioners to identify which sensors or environmental factors most strongly indicate anomalous conditions. These insights enable targeted interventions, preventive maintenance, and improved farm management strategies.

3.3. Advanced Optimization and Adaptive Mechanisms

- Adaptive Threshold OptimizationFixed thresholds may not work well when data changes over time. The proposed method automatically finds detection thresholds through systematic evaluation, addressing this limitation effectively.

- Optimization ProcessFor each selected model , thresholds are tested with a step of 0.05. For each threshold, the F1-score is calculated:The optimal threshold is chosen as follows:This ensures that each detector works at a balanced precision–recall point, improving ensemble contribution while keeping detection sensitivity suitable for agricultural applications.

- Adaptive Update RuleThresholds are updated adaptively using the following:where is the adaptation rate. This value was chosen through a grid search with in steps of 0.1, optimizing the F1-score on validation data. Results: gives , gives , and gives .

3.4. Score Normalization, Ensemble Integration, and Application Benefits

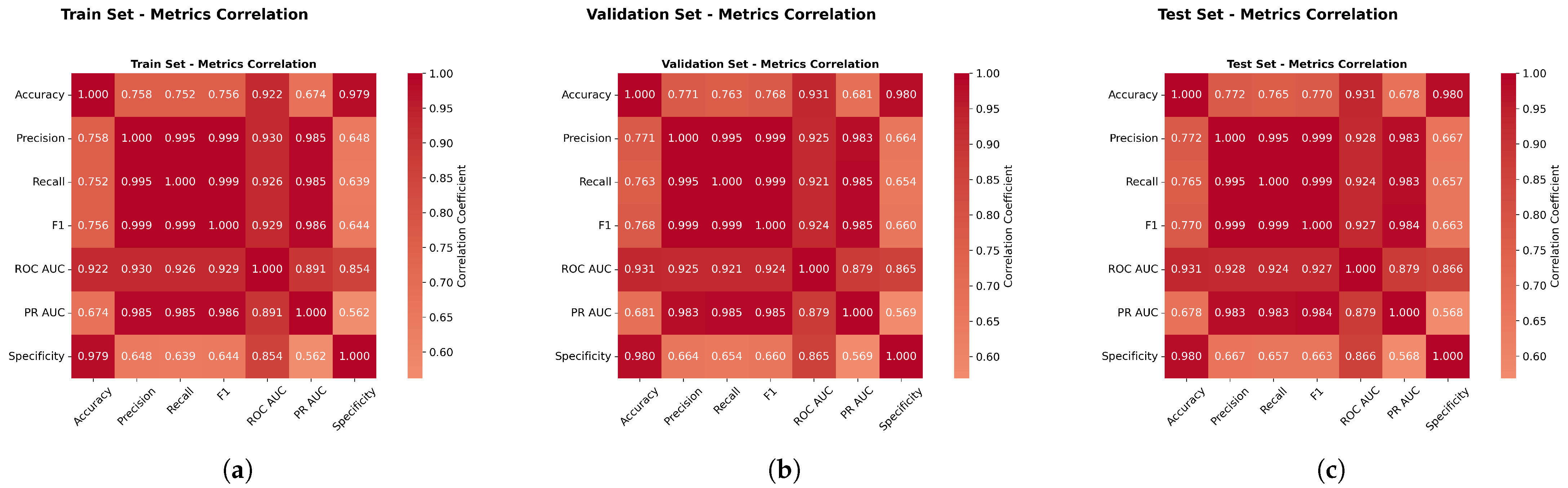

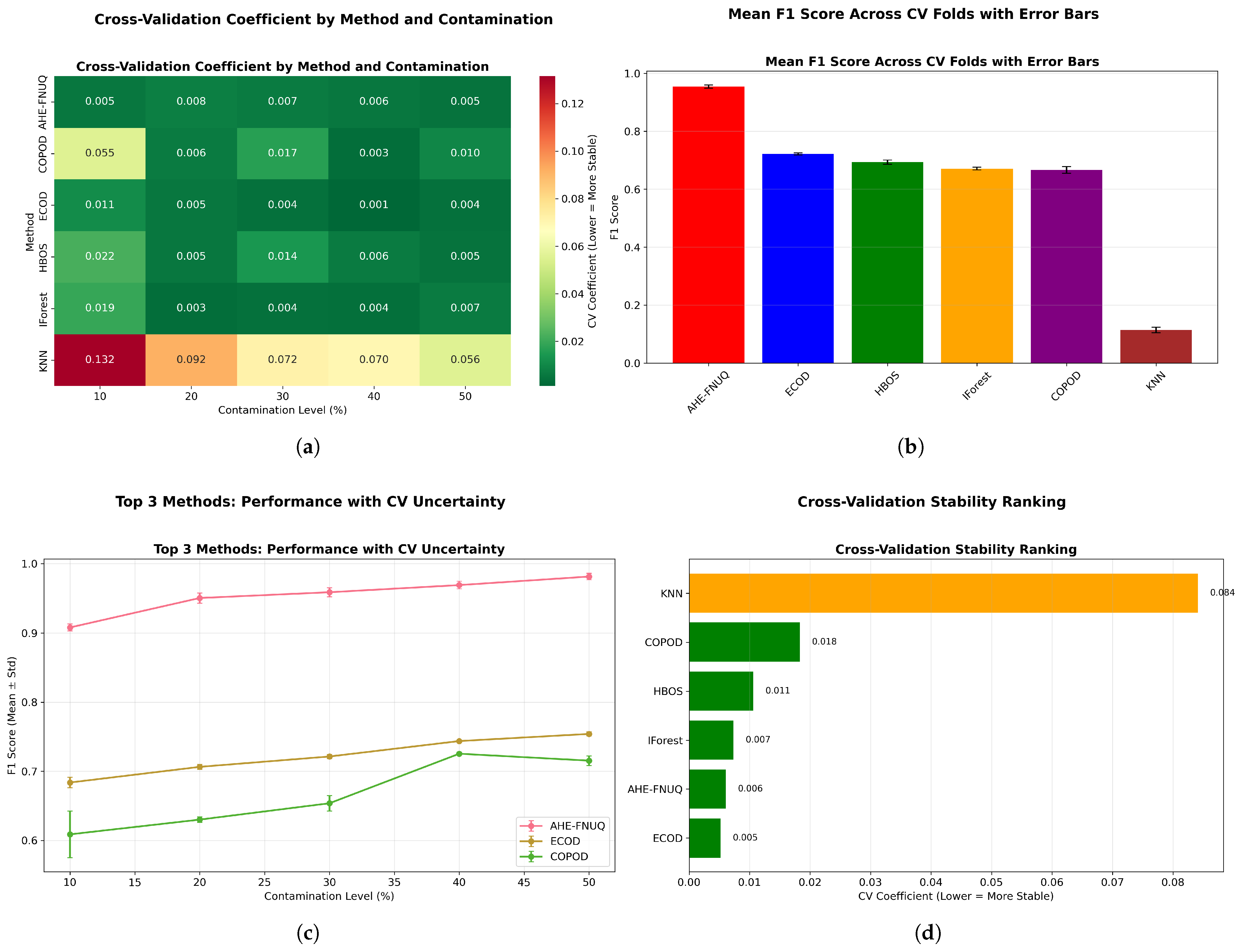

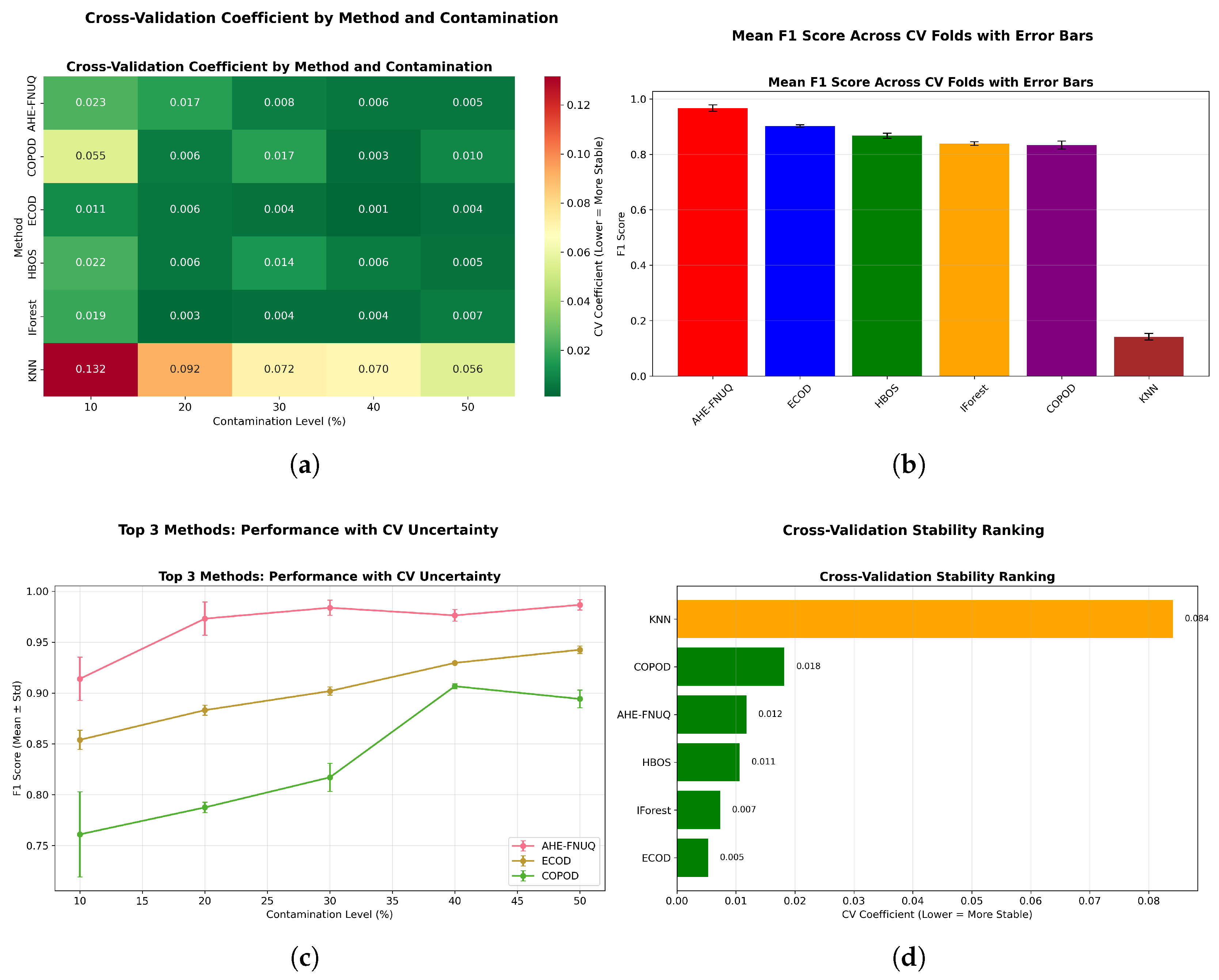

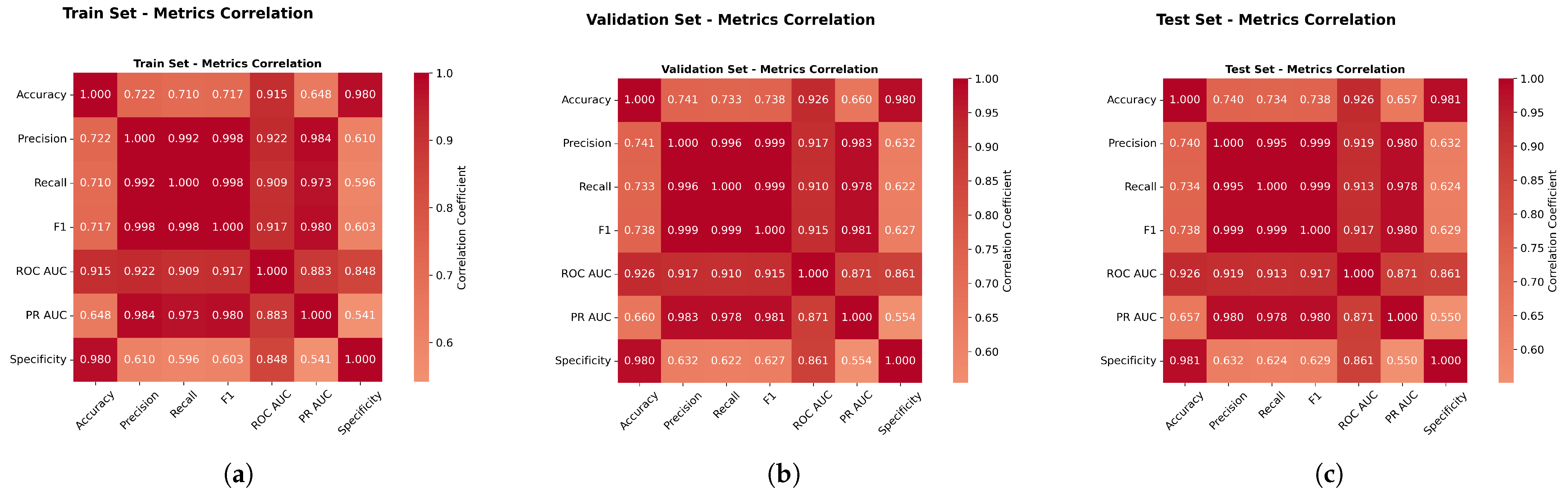

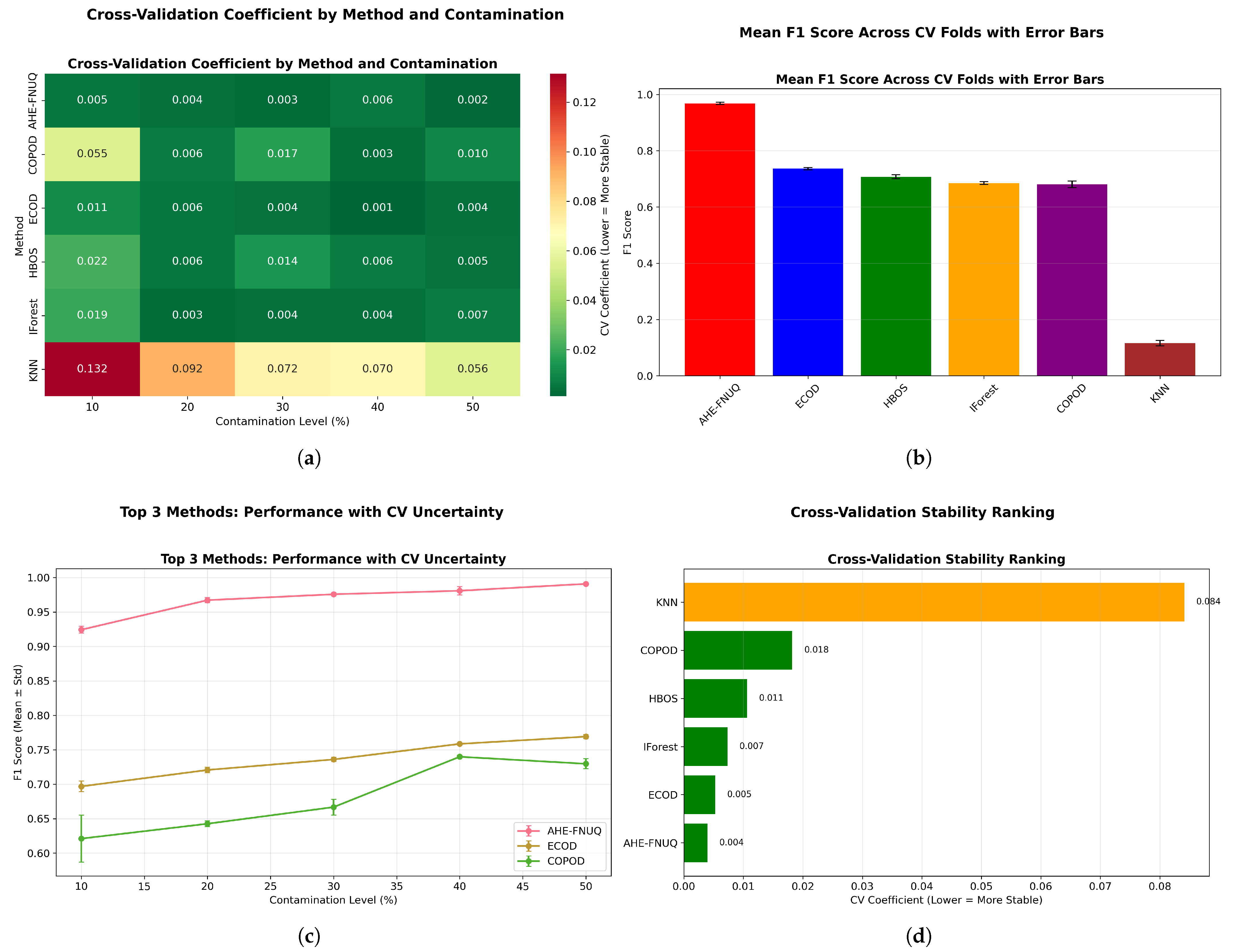

3.5. Comprehensive Statistical Validation Framework

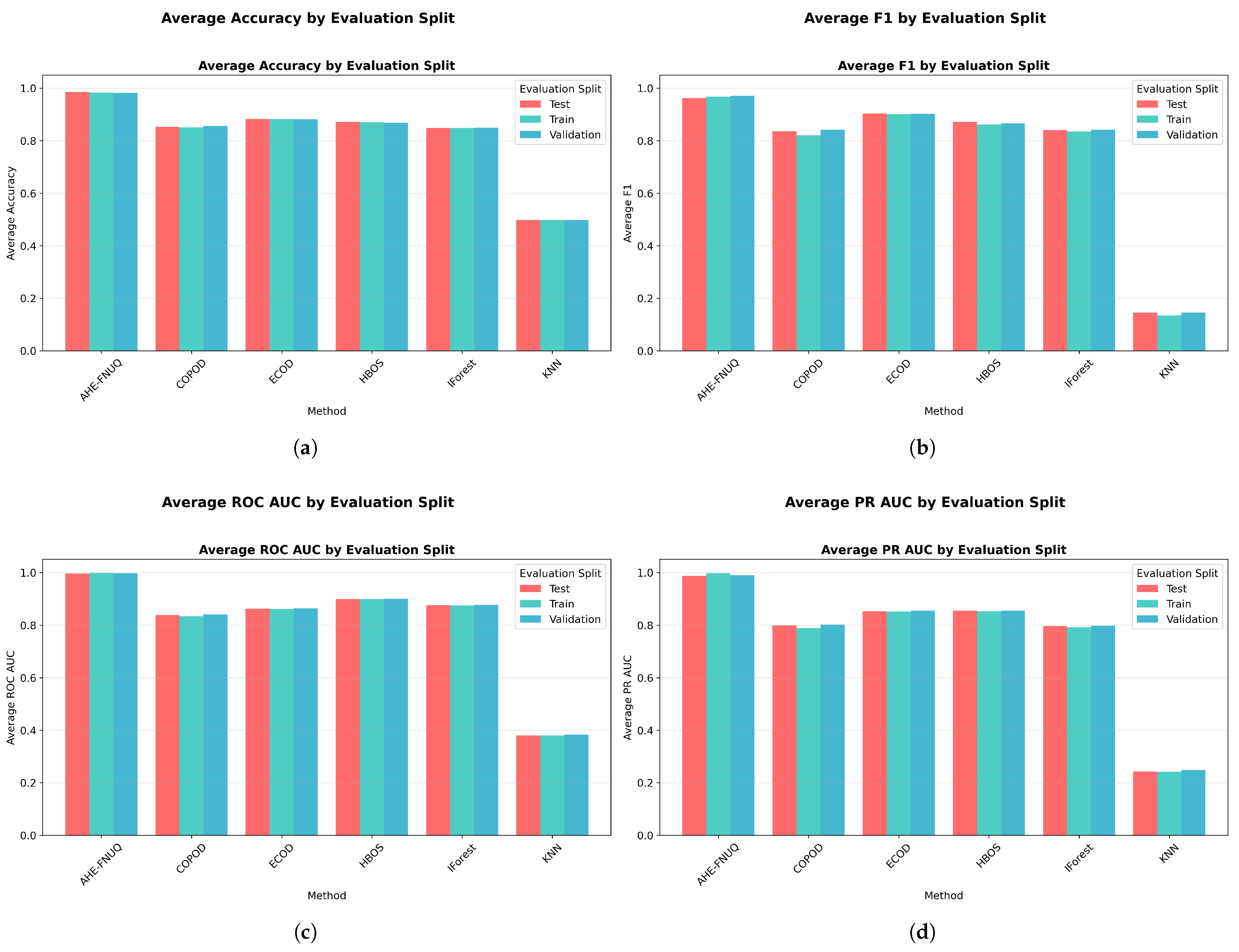

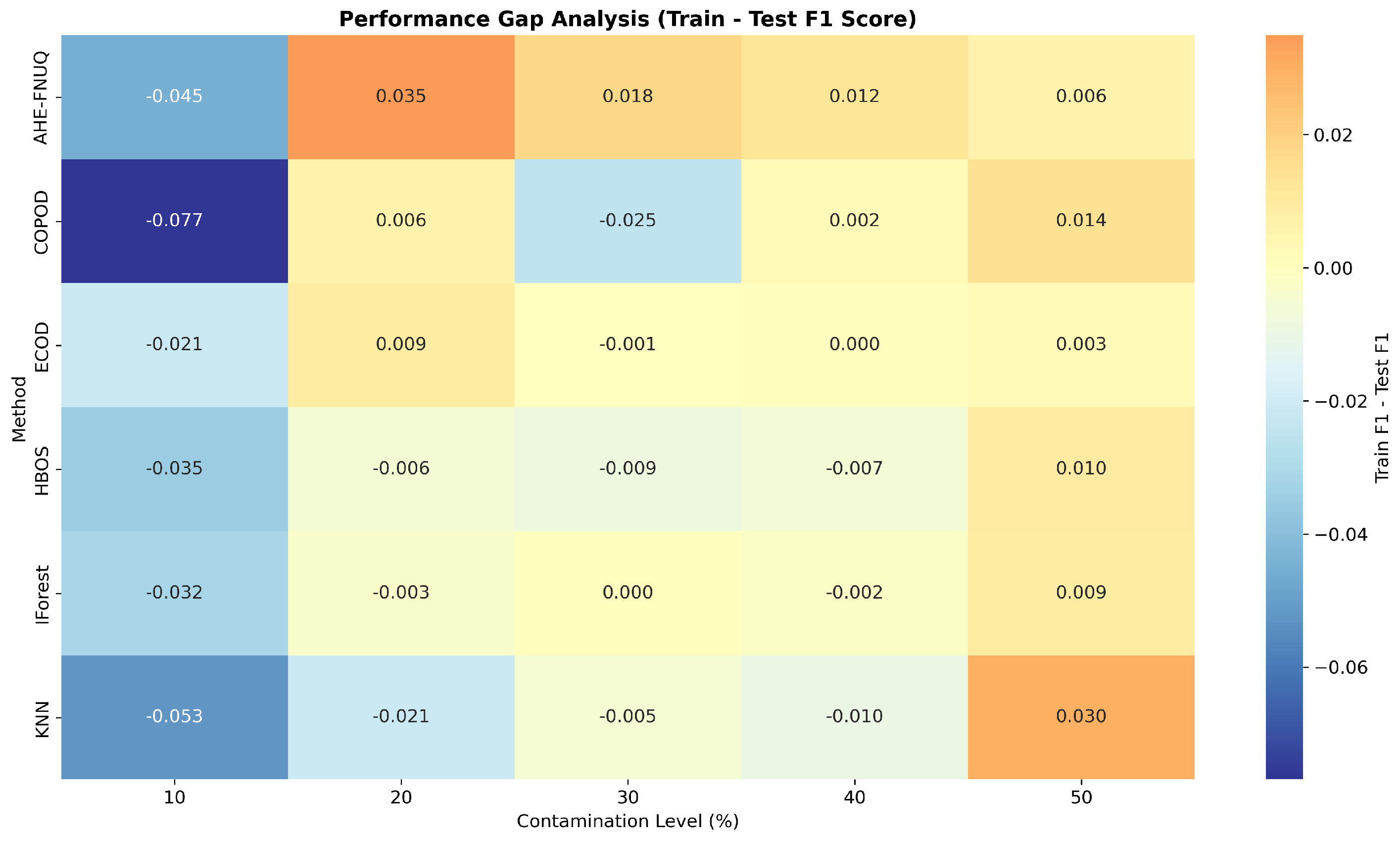

- Cross-Validation Protocol: A stratified 5-fold cross-validation is applied with contamination levels of 10.

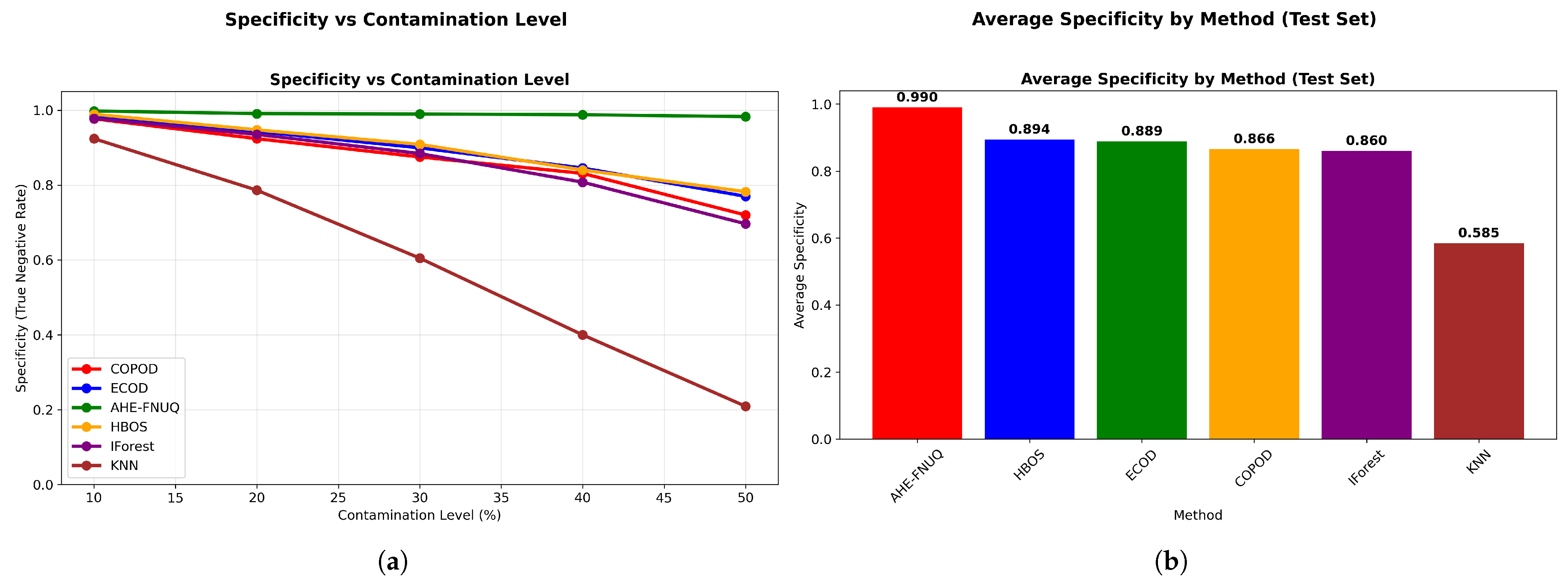

- Performance Metrics: Detection is measured by Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC-ROC, and Specificity. Together, these give a complete view of the framework’s ability.

- Statistical Testing: Performance is compared using the Friedman test for several algorithms and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for pairwise comparisons.

4. Comparative Methodological Analysis

5. Experiment Setup

5.1. Datasets Description

5.2. Computational Environment

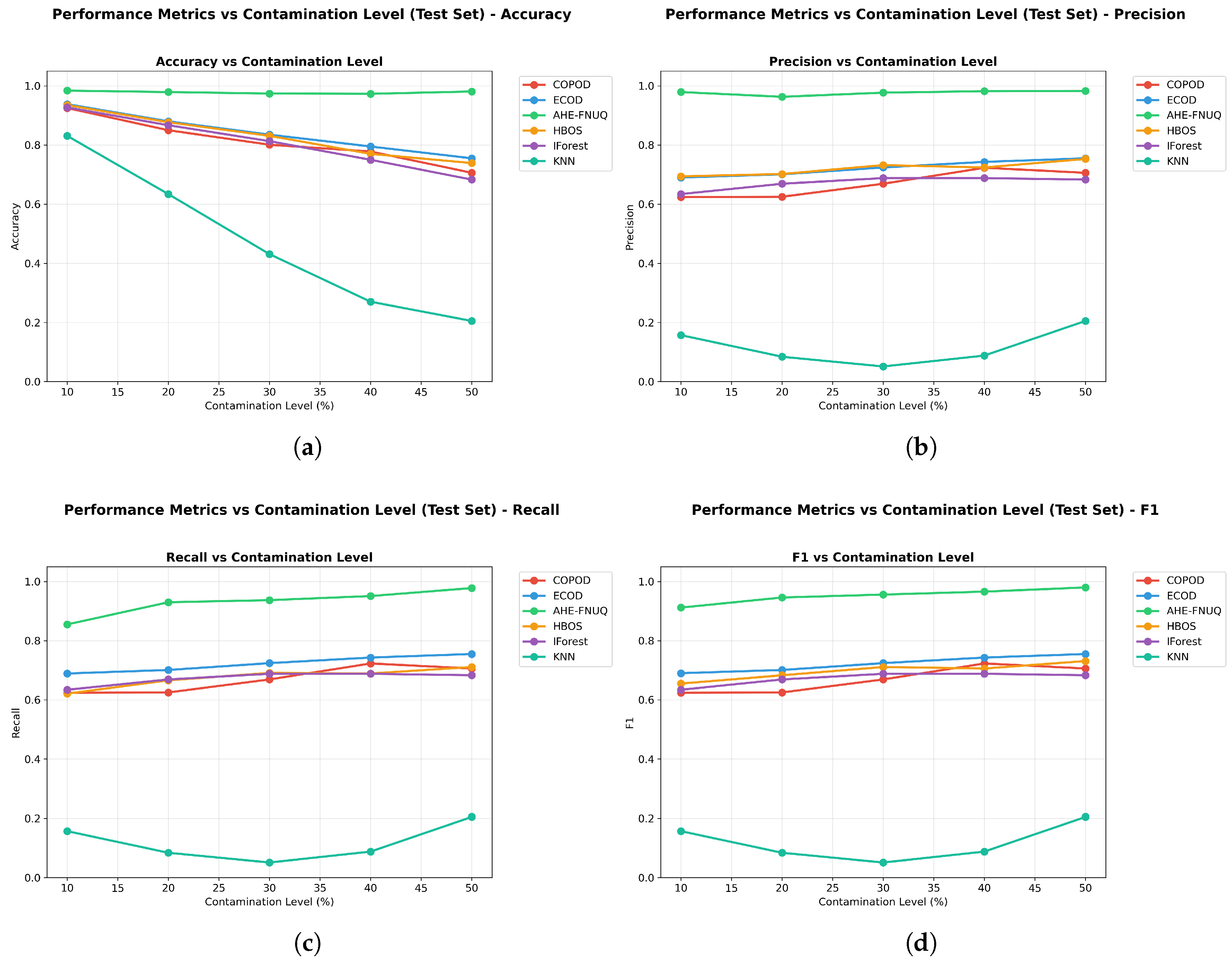

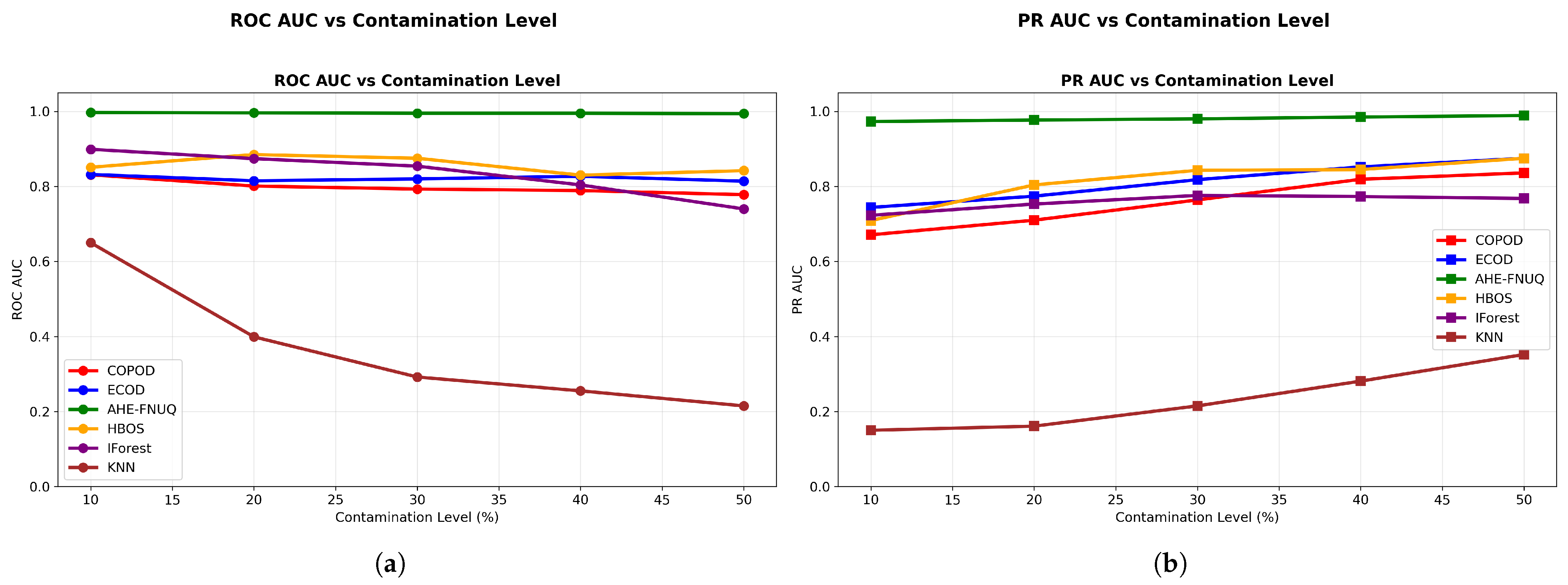

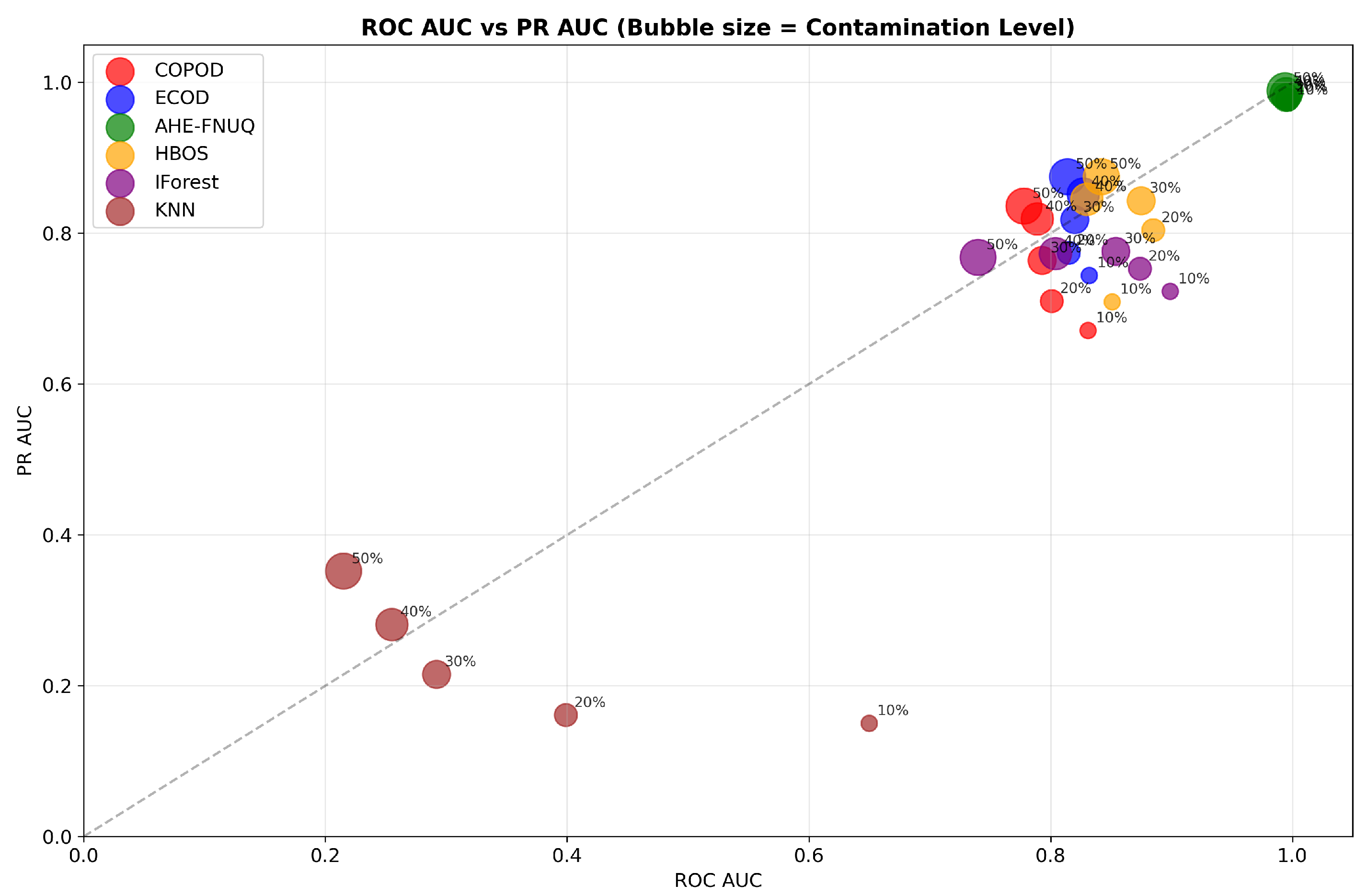

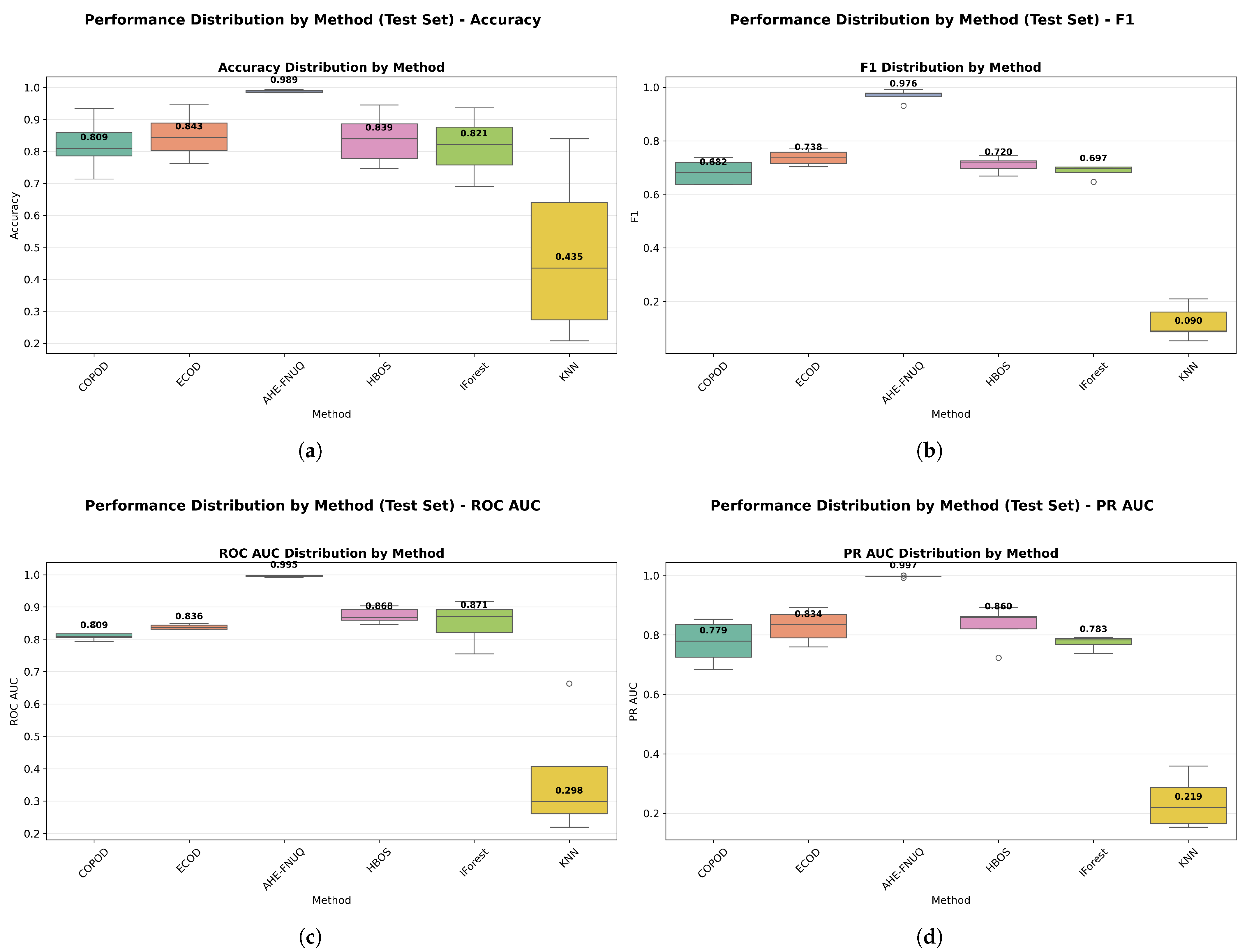

6. Experimental Results and Discussion

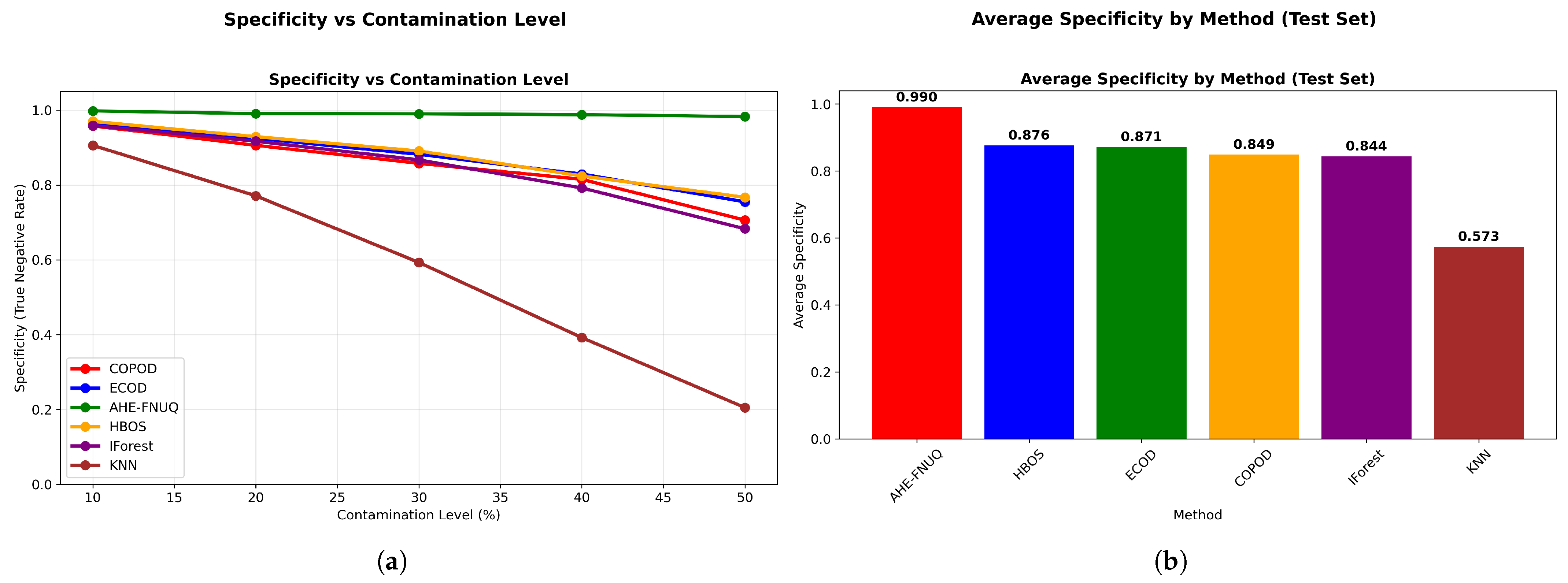

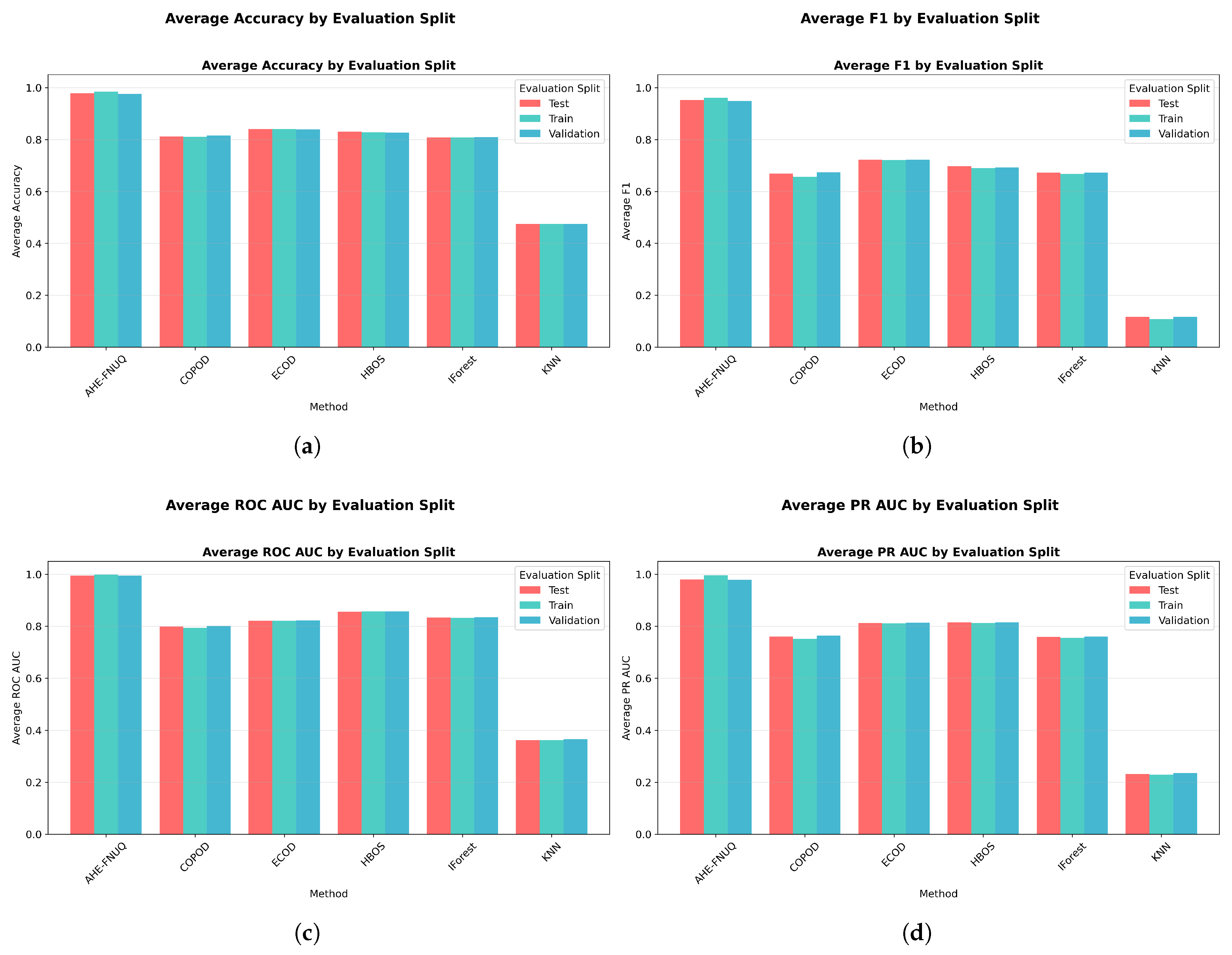

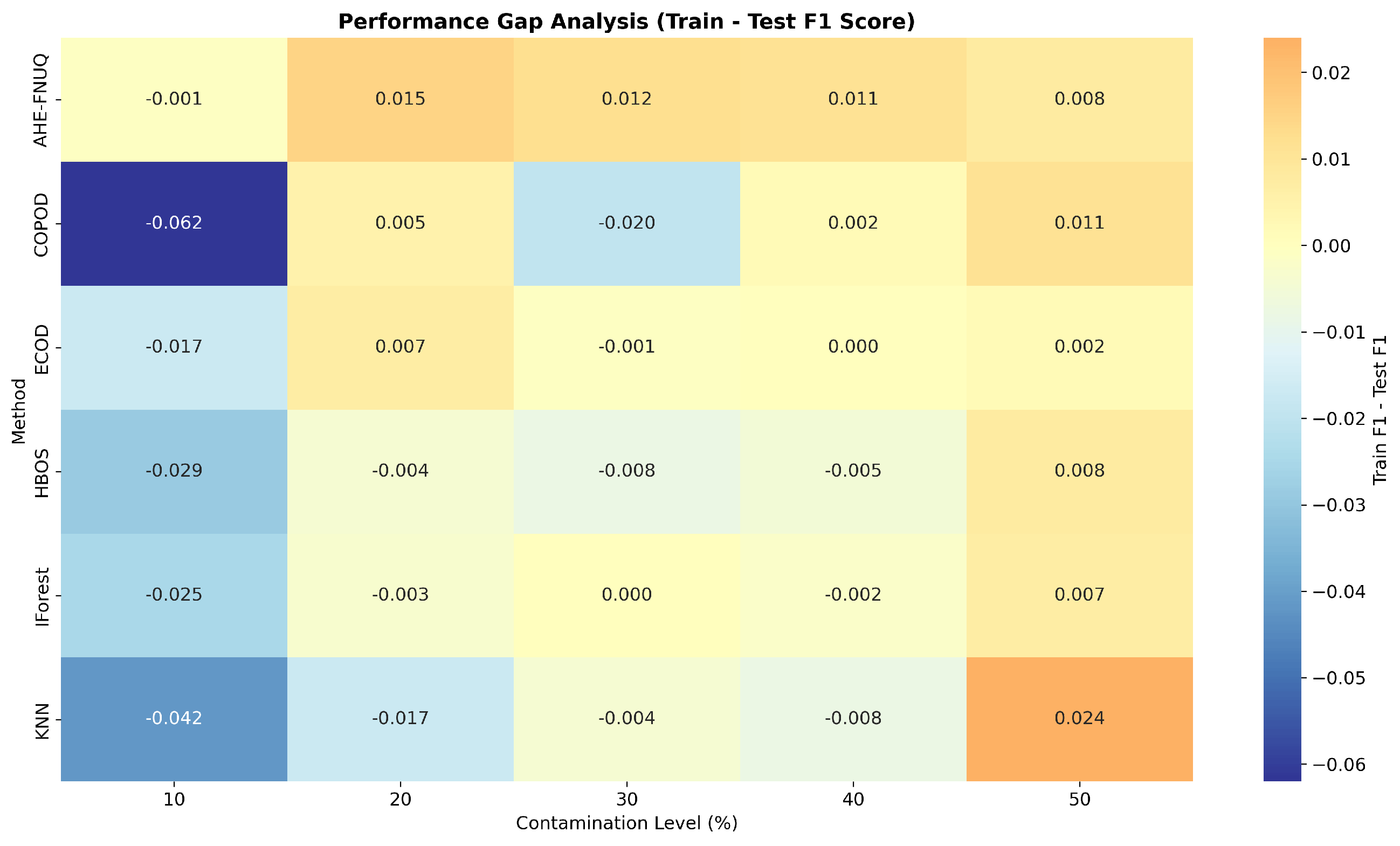

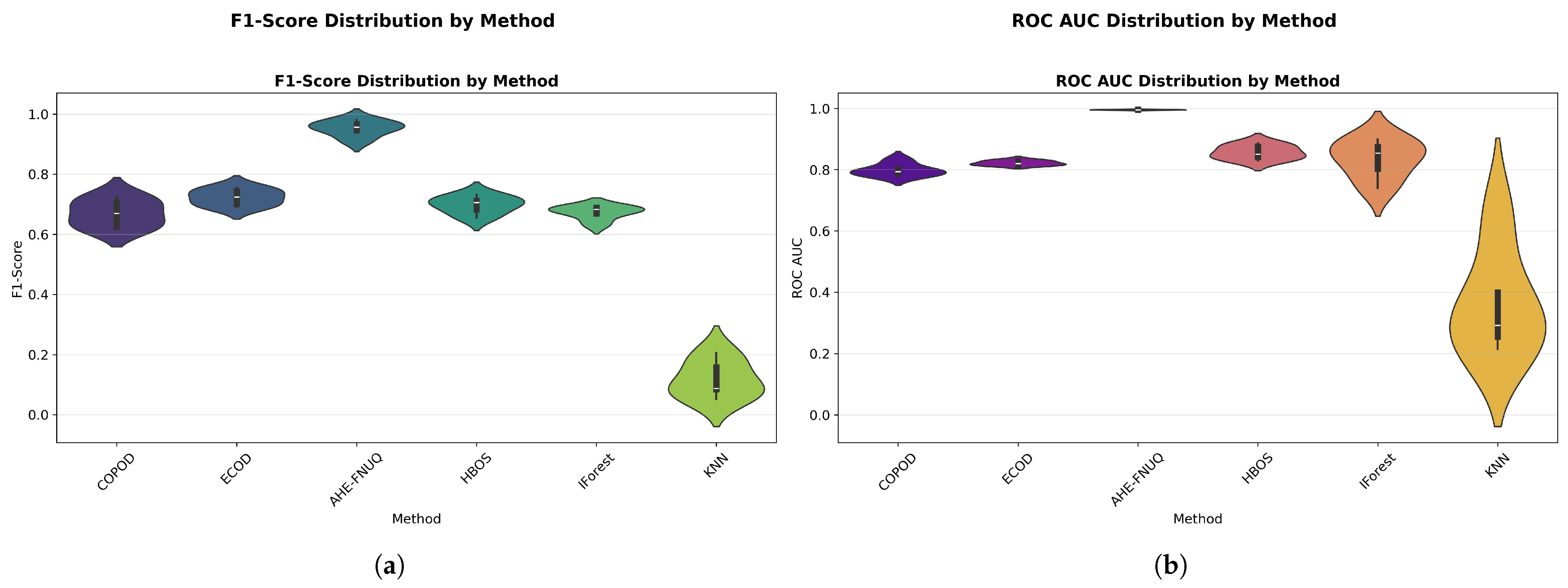

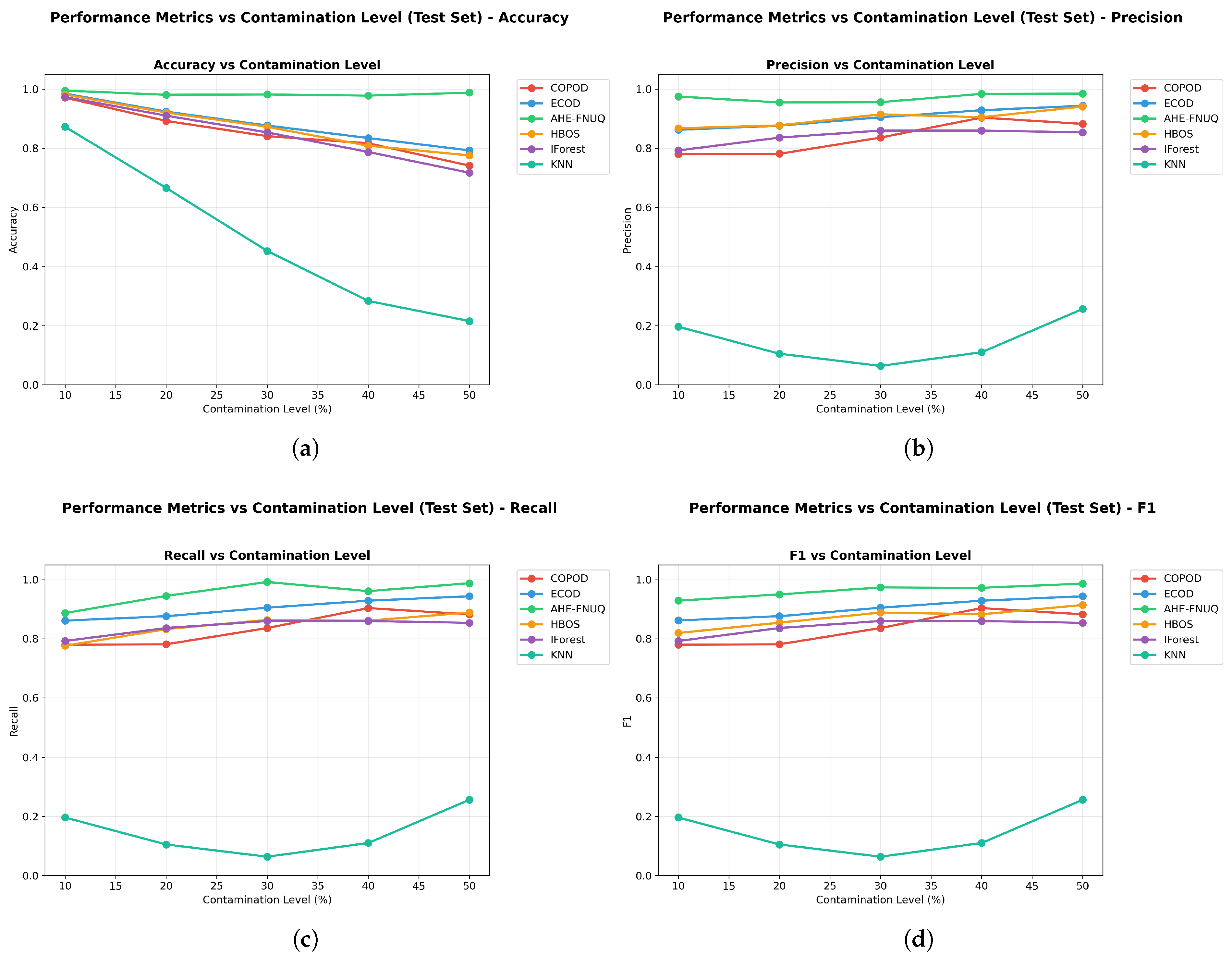

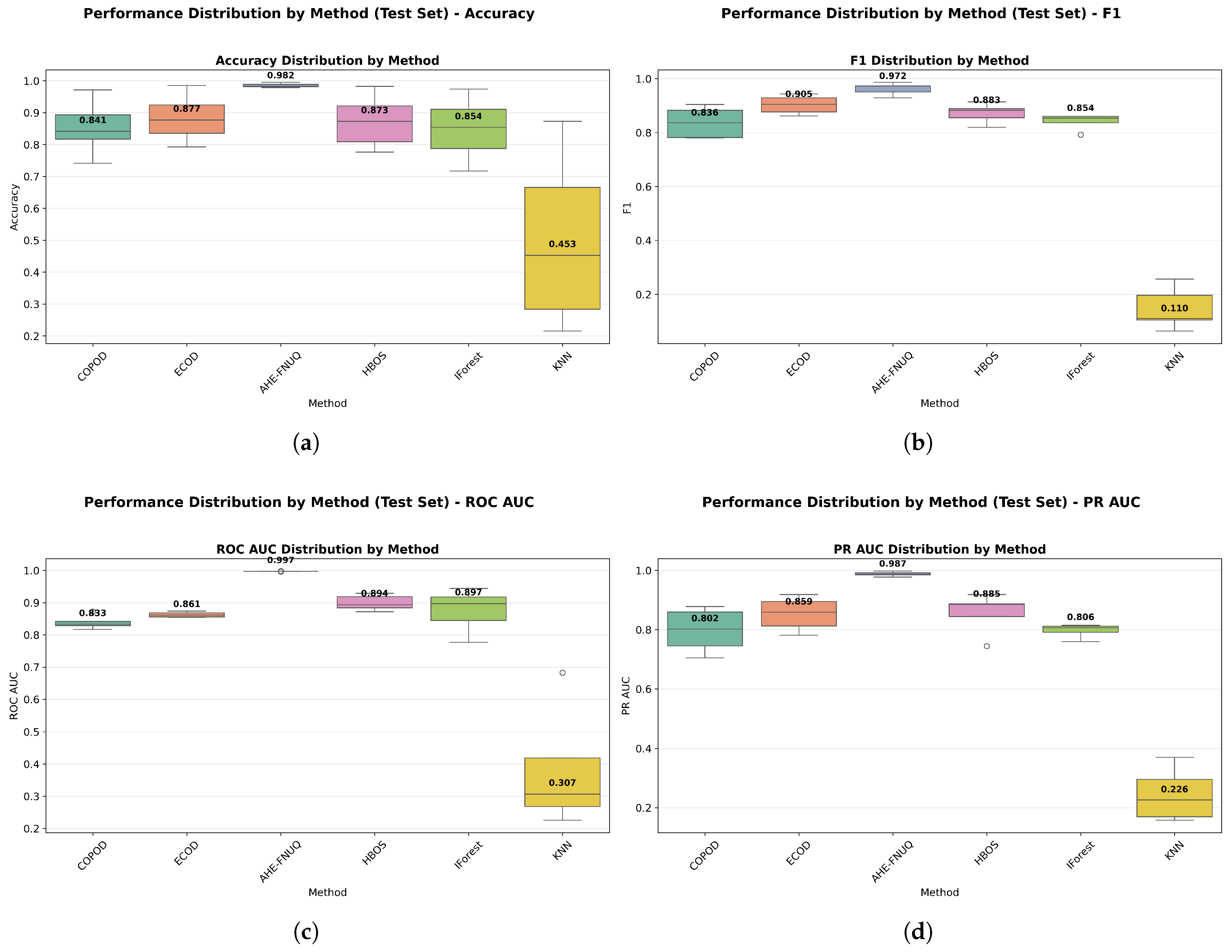

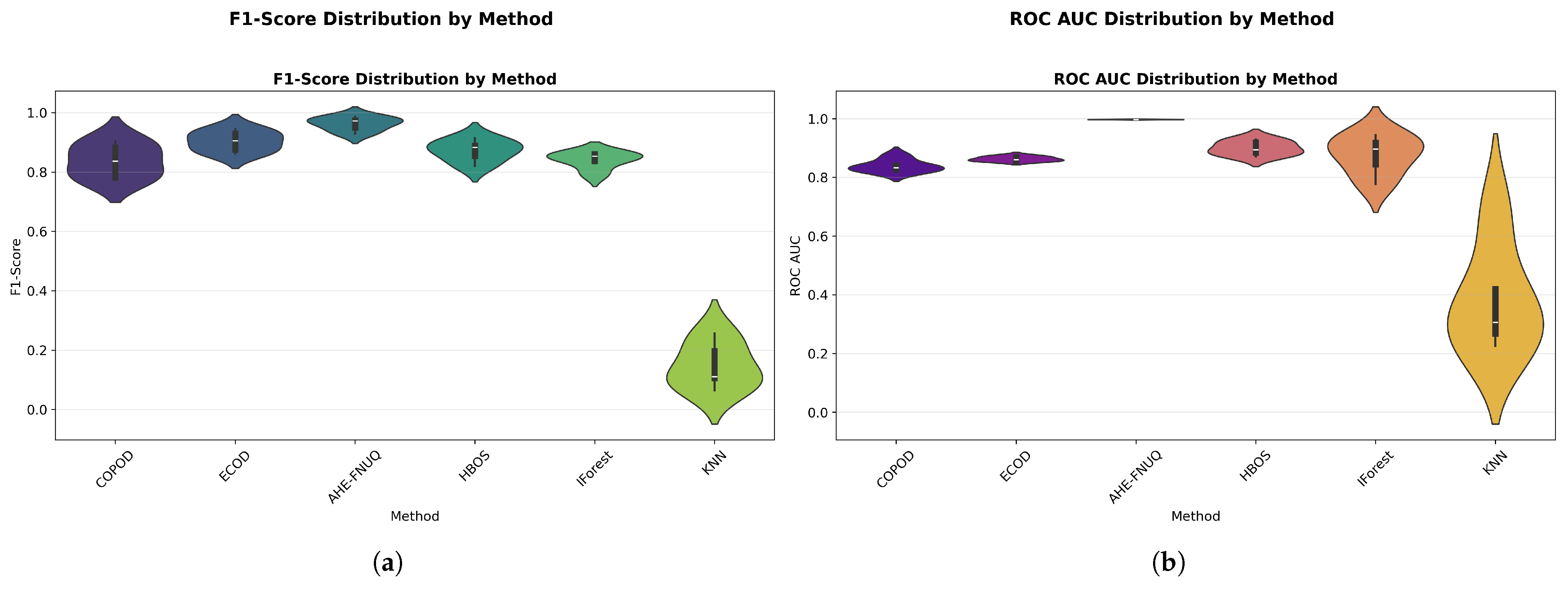

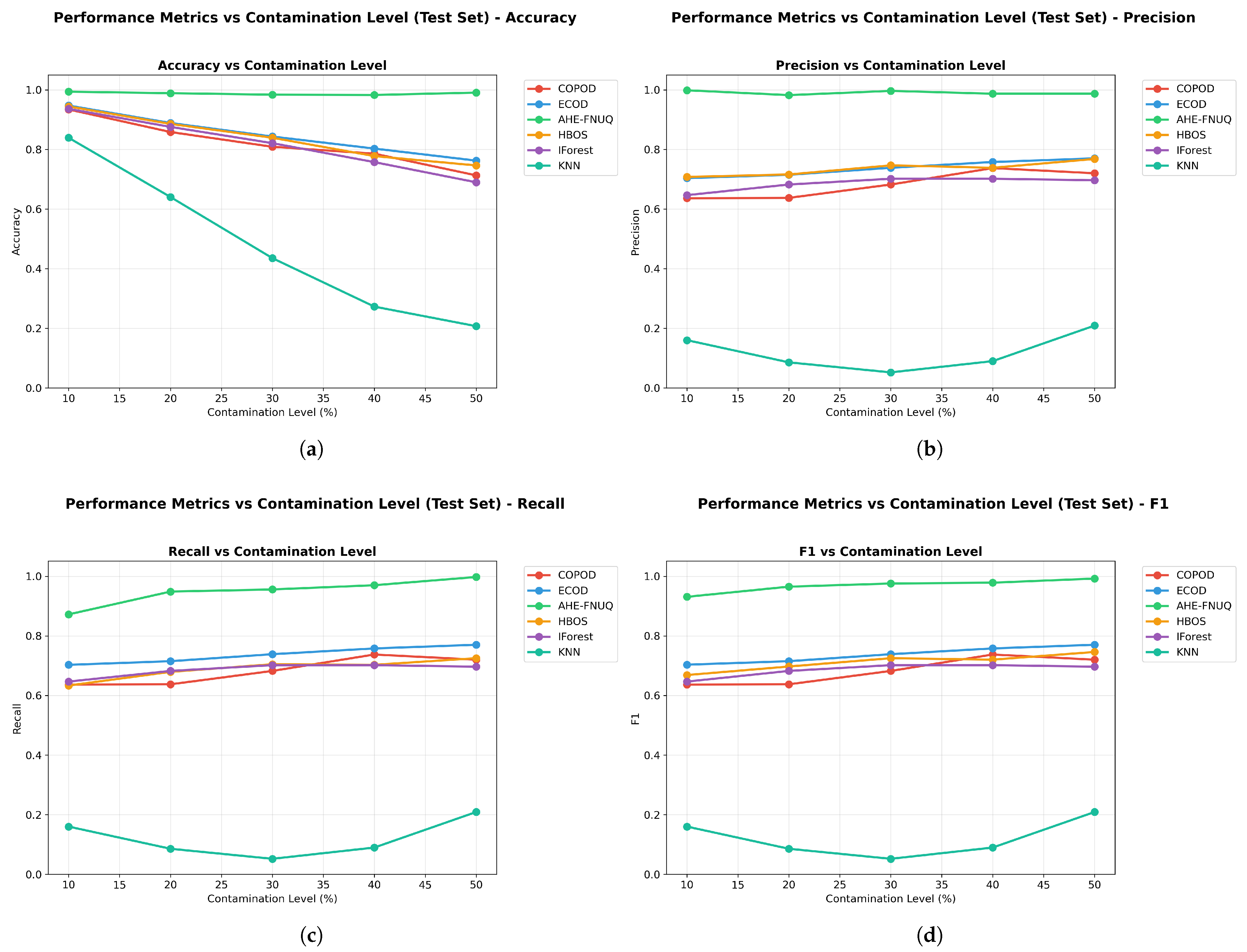

6.1. Results

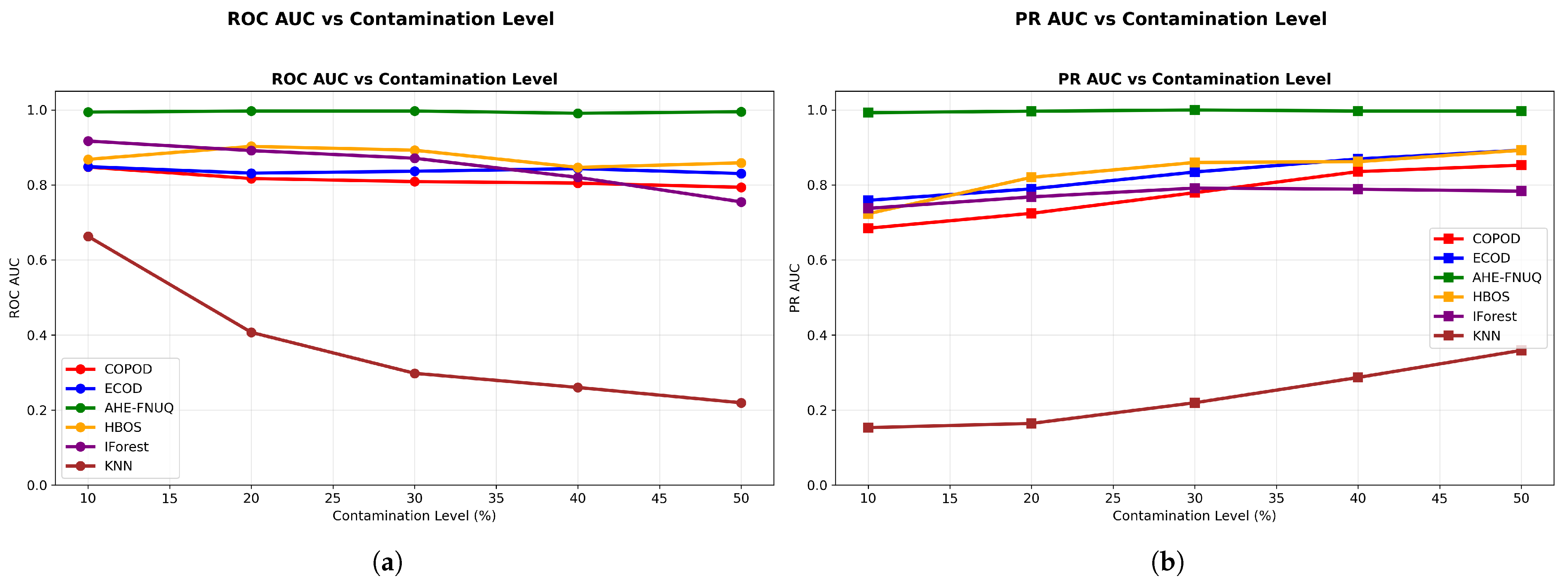

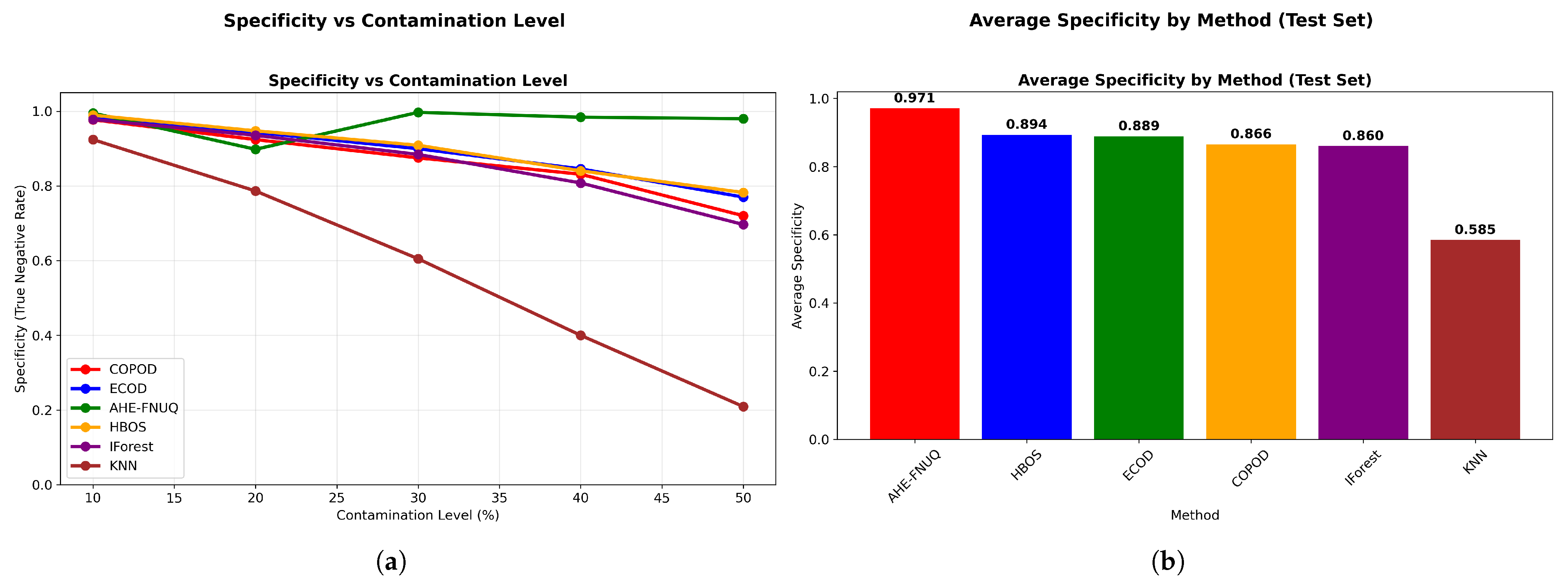

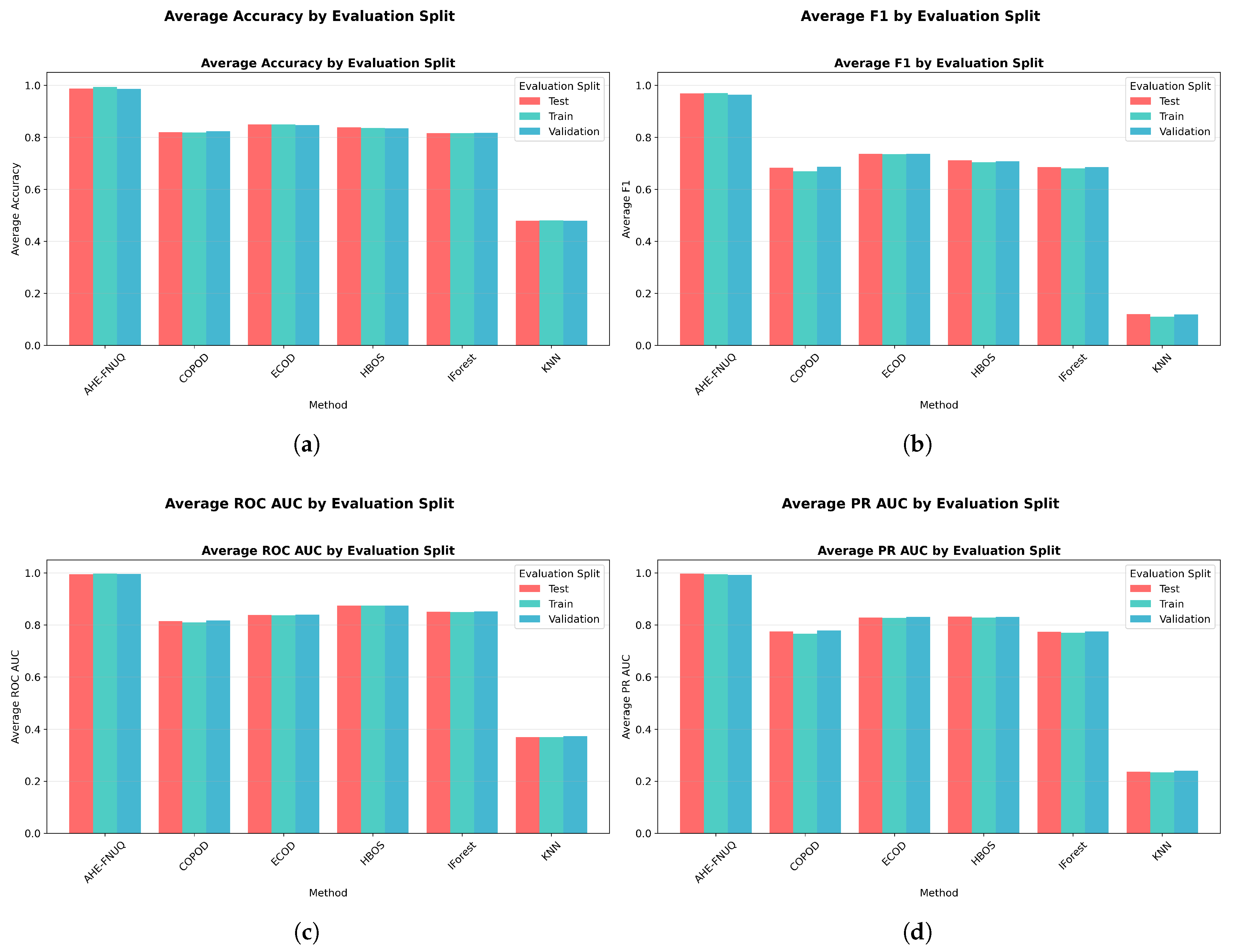

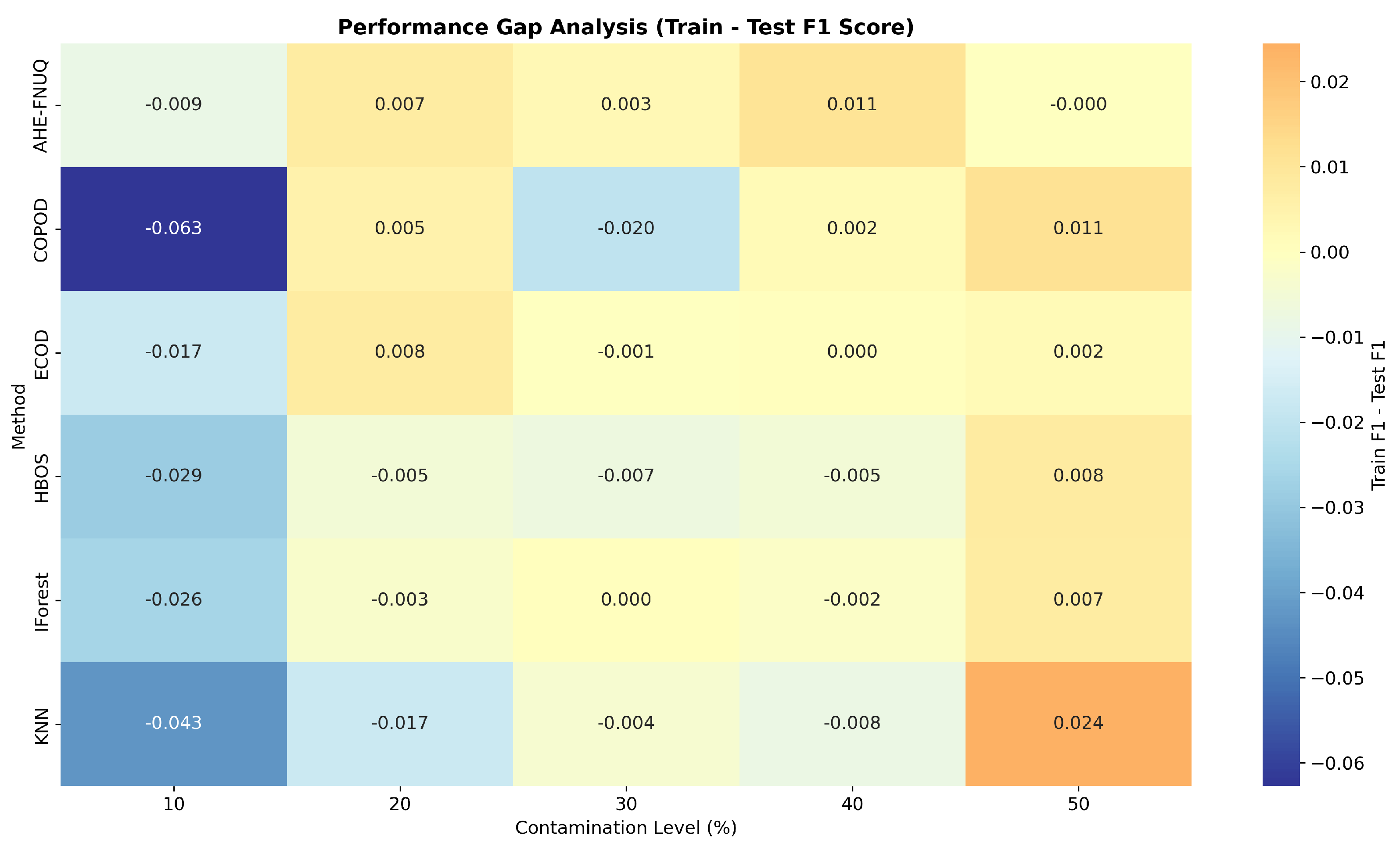

6.1.1. Weather in Szeged Dataset: Primary Agricultural Outlier Detection Analysis

6.1.2. GreenHouse Dataset: Primary Agricultural Outlier Detection Analysis

6.1.3. IoT Agriculture 2024 Dataset: Triple-Validation Completion

6.1.4. Statistical Test

6.2. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayavaca-Vallejo, L.; Avila-Pesantez, D. Smart home iot cybersecurity survey: A systematic mapping. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Information Communications Technology and Society (ICTAS), Durban, South Africa, 8–9 March 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Da Xu, L. Internet of Things (IoT) cybersecurity research: A review of current research topics. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 2103–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. Internet of Things (IoT) cybersecurity: Literature review and IoT cyber risk management. Future Internet 2020, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, B.; Firouzi, F.; Chang, V.; Badaroglu, M.; Constant, N.; Mankodiya, K. Towards fog-driven IoT eHealth: Promises and challenges of IoT in medicine and healthcare. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 78, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rghioui, A.; Oumnad, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Internet of Things in Healthcare. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2018, 8, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, M.H.; Madanipour, M.; Nikravan, M.; Asghari, P.; Mahdipour, E. A systematic review of IoT in healthcare: Applications, techniques, and trends. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 192, 103164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viju, A.; Shukla, P.; Pawar, A.; Sawant, P. IOT Based Industrial Monitoring and Fault Detection System. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 7, 3149–3151. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, K.S.; Bhagat, P.H. Industrial process monitoring using loT. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud), Palladam, Tamil Nadu, India, 10–11 February 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricio, M.A.; Behrens, F.H.; Bianchini, D. Monitoring of industrial electrical equipment using IoT. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2020, 18, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Lee, K. An artificial intelligence approach to financial fraud detection under IoT environment: A survey and implementation. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Veena, C.; Singla, A.; Joshi, A.; Lourens, M.; Kafila. Fraud Detection in IoT-Based Financial Transactions Using Anomaly Detection Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication and Applied Informatics (ACCAI), Chennai, India, 9–10 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Sun, G.; Fu, S.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Gao, Y. Internet financial fraud detection based on a distributed big data approach with node2vec. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43378–43386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moso, J.C.; Cormier, S.; de Runz, C.; Fouchal, H.; Wandeto, J.M. Anomaly detection on data streams for smart agriculture. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerych, W.; Agu, E.; Rundensteiner, E. Classifying depression in imbalanced datasets using an autoencoder-based anomaly detection approach. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC), Newport Beach, CA, USA, 30 January–1 February 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, R.K.; Salekshahrezaee, Z.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Unsupervised anomaly detection of class imbalanced cognition data using an iterative cleaning method. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 24th International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI), Bellevue, WA, USA, 4–6 August 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Saurav, S.; Malhotra, P.; TV, V.; Gugulothu, N.; Vig, L.; Agarwal, P.; Shroff, G. Online anomaly detection with concept drift adaptation using recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the ACM India Joint International Conference on Data Science and Management of Data, Goa, India, 11–13 January 2018; pp. 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Erfani, S.M.; Rajasegarar, S.; Karunasekera, S.; Leckie, C. High-dimensional and large-scale anomaly detection using a linear one-class SVM with deep learning. Pattern Recognit. 2016, 58, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, K.; Brodley, C.; Slonim, D. Anomaly detection using an ensemble of feature models. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 13–17 December 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 953–958. [Google Scholar]

- Vanerio, J.; Casas, P. Ensemble-learning approaches for network security and anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Big Data Analytics and Machine Learning for Data Communication Networks, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 21 August 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, J. Ensemble methods for anomaly detection based on system log. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 24th Pacific Rim International Symposium on Dependable Computing (PRDC), Kyoto, Japan, 1–3 December 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 93–931. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Mao, Z. A dynamic ensemble outlier detection model based on an adaptive k-nearest neighbor rule. Inf. Fusion 2020, 63, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Ensembles for Outlier Detection and Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Ang, H.H.; Gopalkrishnan, V. Mining outliers with ensemble of heterogeneous detectors on random subspaces. In Proceedings of the International conference on database systems for advanced applications, Tsukuba, Japan, 1–4 April 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 368–383. [Google Scholar]

- Pasillas-Díaz, J.R.; Ratté, S. Bagged subspaces for unsupervised outlier detection. Comput. Intell. 2017, 33, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.A.J.; Ghafoor, A.; Kim, J.; Abbas, Z.; Lee, S.W. HeartEnsembleNet: An Innovative Hybrid Ensemble Learning Approach for Cardiovascular Risk Prediction. Healthcare 2025, 13, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, J.; Cheng, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Morishetti, L.; Nag, K.; Amiri, H. FUTURE: Flexible Unlearning for Tree Ensemble. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, New York, NY, USA, 1–5 November 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, N.; Maity, K.; Paul, R.; Maity, S. Outlier detection in sensor data using machine learning techniques for IoT framework and wireless sensor networks: A brief study. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Applied Machine Learning (ICAML), Bhubaneswar, India, 25–26 May 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, I.; Mahmoud, Q.H. Design and development of RNN anomaly detection model for IoT networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 62722–62750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devagopal, A.; Menon, V.; Ezekiel, S.; Chaudhary, P. Exploring the tractability of data fusion models for detecting anomalies in IoT-based dataset. In Proceedings of the Big Data V: Learning, Analytics, and Applications, Orlando, FL, USA, 1–2 May 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12522, pp. 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal, D.; Meena, J. Anomaly Detection in IoT network Using Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th International Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (GUCON), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 24–26 September 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Abusitta, A.; de Carvalho, G.H.; Wahab, O.A.; Halabi, T.; Fung, B.C.; Al Mamoori, S. Deep learning-enabled anomaly detection for IoT systems. Internet Things 2023, 21, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddam, A.; Wilkin, T.; Angelova, M. Anomaly detection models for detecting sensor faults and outliers in the IoT-a survey. In Proceedings of the 2019 13th International Conference on Sensing Technology (ICST), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2–4 December 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; He, J.; Cui, Z. Adaptive IoT decision making in uncertain environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Smart Internet of Things (SmartIoT), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 17–20 November 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, D.; Srivastava, P.; Martin-del Campo, S.; Natarajan, B.; Srinivasan, B. Addressing uncertainties within active learning for industrial IoT. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 7th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14 June–31 July 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 557–562. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, T.; Nugent, C.; Moore, A.; Liu, J.; Beard, A. A risk-based IoT decision-making framework based on literature review with human activity recognition case studies. Sensors 2021, 21, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, R.; Murugesan, R.K.; Man, M.; Abdulateef, A.F.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Alkahtani, A.A. A review of machine learning and deep learning techniques for anomaly detection in IoT data. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamrini, M.; Ben Mahria, B.; Chkouri, M.Y.; Touhafi, A. Towards reliability in smart water sensing technology: Evaluating classical machine learning models for outlier detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Riaz, R.; Rizvi, S.S.; Shokat, S.; Riaz, F.; Kwon, S.J. Outlier detection in indoor localization and Internet of Things (IoT) using machine learning. J. Commun. Netw. 2020, 22, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustelnyk, P.; Levus, Y. Real-time anomaly detection in distributed IOT systems: A comprehensive review and comparative analysis. Vìsnik Nacìonal’nogo unìversitetu L’vìvs’ka polìtehnìka Serìâ Ìnformacìjnì sistemi ta merežì 2025, 17, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.A.; Mısırlı, G.; Fan, Z. Anomaly detection for IoT time-series data: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 6481–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, J. Data anomaly detection in the internet of things: A review of current trends and research challenges. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, S.H.; Abdallah, A.; Musa, N.S.; Murugan, T. Machine learning and deep learning techniques for internet of things network anomaly detection—Current research trends. Sensors 2024, 24, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevtchenko, S.F.; Rocha, E.D.S.; Dos Santos, M.C.M.; Mota, R.L.; Vieira, D.M.; De Andrade, E.C.; De Araújo, D.R.B. Anomaly detection in industrial machinery using IoT devices and machine learning: A systematic mapping. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 128288–128305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez López, M.L.; Múnera Ramírez, D.A.; Tobón Vallejo, D.P. Anomaly classification in industrial Internet of things: A review. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2023, 18, 200232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Henriksen, A.; Edwards, G.T.; Pesonen, L.A.; Green, O.; Sørensen, C.A.G. Internet of Things in arable farming: Implementation, applications, challenges and potential. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 191, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkountakos, K.; Ioannidis, K.; Demestichas, K.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. A Comprehensive Review of Deep Learning-Based Anomaly Detection Methods for Precision Agriculture. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 197715–197733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Khawaja, B.A.; Farooq, Q.U. IoT-equipped and AI-enabled next generation smart agriculture: A critical review, current challenges and future trends. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 21219–21235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, M.; Morales, R.G.; Sánchez-Molina, J. Comparative analysis of agricultural IoT systems: Case studies IoF2020 and CyberGreen. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, T.; Deisy, C.; Sridevi, S.; Anbananthen, K.S.M. A comparative study of deep learning and Internet of Things for precision agriculture. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, A.; Pardo, S.; Sepúlveda, S.; Muñoz, L. Challenges to use machine learning in agricultural big data: A systematic literature review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Chang, L.; Wang, K.; Zhong, Y.; Han, D.; Duan, C.; Yin, X.; Yang, J.; Shi, X. Network anomaly detection via similarity-aware ensemble learning with ADSim. Comput. Netw. 2024, 247, 110423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Yu, Y.; Chen, G.; Hu, J. Online ensemble learning-based anomaly detection for IoT systems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 173, 112931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doreswamy; Hooshmand, M.K.; Gad, I. Feature selection approach using ensemble learning for network anomaly detection. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2020, 5, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Mannan, A.; Javed, A.R.; Almadhor, A.S.; Baker, T.; Al-Jumeily, D. Cloud-based multiclass anomaly detection and categorization using ensemble learning. J. Cloud Comput. Adv. Syst. Appl. 2022, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshmand, M.K.; Huchaiah, M.D.; Alzighaibi, A.R.; Hashim, H.; Atlam, E.S.; Gad, I. Robust network anomaly detection using ensemble learning approach and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 94, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Kou, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y. An Anomaly Detection Algorithm Based on Ensemble Learning for 5G Environment. Sensors 2022, 22, 7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, N.; Tan, Q.; Villar, J.R. Using Ensemble Learning for Anomaly Detection in Cyber–Physical Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Domain | Method Type | Key Strengths | Limitations | Dataset Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | General IoT | Time-series Survey | IoT-specific focus | Use-case specificity | Medium |

| [41] | General IoT | ML/DL Survey | Comprehensive analysis | High dimensionality issues | Large-scale |

| [39] | Distributed IoT | Active Learning | Reduces labeled data dependency | Limited adaptability | Medium |

| [42] | IoT Networks | ML/DL Techniques | Network-focused analysis | Algorithm inaccuracy | Variable |

| [43] | Industrial IoT | Systematic Mapping | Sector-specific focus | Limited ML integration | 84 studies |

| [44] | Industrial IoT | Classification Review | Industrial context | Data quality issues | Medium |

| [45] | Agricultural IoT | Implementation Study | Practical challenges | No specific algorithms | Field studies |

| [46] | Agricultural IoT | DL | Domain-specific analysis | Visual data reliance | Small |

| Challenge Category | General IoT [39,40,41,42] | Industrial IoT [43,44] | Agricultural IoT [45,47,48,49,50] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Characteristics | |||

| Data Sparsity | Moderate | Low | High |

| Seasonal Variations | Low | None | Critical |

| Multi-modal Integration | Moderate | Low | High |

| Environmental Factors | |||

| Controlled Environment | Variable | High | None |

| Weather Dependencies | Low | None | Critical |

| Biological Complexity | None | None | High |

| Operational Constraints | |||

| Power Limitations | Moderate | Low | High |

| Network Connectivity | Variable | High | Limited |

| Cost Sensitivity | Moderate | Low | Critical |

| Performance Requirements | |||

| Real-time Processing | High | Critical | Moderate |

| Accuracy Requirements | High | Critical | High |

| Interpretability | Moderate | High | Critical |

| Research Gap | Identified By | Impact Level | Current Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse Data Handling | [45] | Critical | Limited |

| Seasonal Adaptation | [46] | High | Manual adjustment |

| Uncertainty Quantification | [41] | High | Basic confidence |

| Cost Effectiveness | [45] | Critical | Expensive solutions |

| Method & Domain | Learning Mode | Adaptivity/ Drift Handling | Imbalance & Noise Handling | Explainability/ Uncertainty | Computational/ Deployment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADSim [51], IDS | Online unsupervised | Similarity clustering; no drift triggers | None; assumes stable traffic | None | Moderate; needs stable networks |

| AEWAE [52], IoT | Online supervised | Global drift adaptation via PSO | Partial class weighting; noise-sensitive | None | Moderate–high; IoT cloud/fog |

| FS Ensemble [53], IDS | Offline supervised | None (static FS) | Indirect noise mitigation; no adaptation | None | Low; static offline |

| CAD [54], Cloud | Offline + deep | None | Sensitive to noise; no imbalance mechanism | None | Very high; GPU/cloud required |

| SKM-XGB [55], IDS | Offline supervised | None | SMOTE–KMeans balancing; labeled data | SHAP (static) | Moderate; batch offline |

| SDN-Stacking [56], 5G | Offline + deep | None | Limited imbalance handling | None | High; SDN/cloud only |

| Jeffrey [57], CPS | Offline hybrid | None | Domain heuristics; limited generalization | Partial | Low–moderate; manual tuning |

| AHE–FNUQ (ours) | Offline training + streaming | Dual-threshold dynamic activation | RobustScaler; synthetic outliers | Integrated uncertainty; feature importance | Moderate; edge-optimized; no GPU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amamou, A.; Lamrini, M.; Ben Mahria, B.; Balboul, Y.; Hraoui, S.; Hegazy, O.; Touhafi, A. AHE-FNUQ: An Advanced Hierarchical Ensemble Framework with Neural Network Fusion and Uncertainty Quantification for Outlier Detection in Agri-IoT. Sensors 2025, 25, 6841. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226841

Amamou A, Lamrini M, Ben Mahria B, Balboul Y, Hraoui S, Hegazy O, Touhafi A. AHE-FNUQ: An Advanced Hierarchical Ensemble Framework with Neural Network Fusion and Uncertainty Quantification for Outlier Detection in Agri-IoT. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6841. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226841

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmamou, Ahmed, Mimoun Lamrini, Bilal Ben Mahria, Younes Balboul, Said Hraoui, Omar Hegazy, and Abdellah Touhafi. 2025. "AHE-FNUQ: An Advanced Hierarchical Ensemble Framework with Neural Network Fusion and Uncertainty Quantification for Outlier Detection in Agri-IoT" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6841. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226841

APA StyleAmamou, A., Lamrini, M., Ben Mahria, B., Balboul, Y., Hraoui, S., Hegazy, O., & Touhafi, A. (2025). AHE-FNUQ: An Advanced Hierarchical Ensemble Framework with Neural Network Fusion and Uncertainty Quantification for Outlier Detection in Agri-IoT. Sensors, 25(22), 6841. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226841