Multimodal Fusion for Trust Assessment in Lower-Limb Rehabilitation: Measurement Through EEG and Questionnaires Integrated by Fuzzy Logic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

- Single-point cane and wide-based walker: Participants navigated a path with obstacles of varying sizes placed along both sides. To increase the perceived challenge and assess trust under controlled conditions, paper and glass cups were placed on top of obstacles, requiring careful negotiation to avoid contact.

- Climbing stair: Training intensity was gradually increased by progressively shortening the allowed time to complete the task as participants gained more confidence—this enabled observation of their reliance on the equipment under increased physical demands.

- Handrail-equipped path: Participants navigated a handrail-equipped path with low-height obstacles placed along its length. This setup required precise stepping and balance control, challenging their trust in their own abilities and the support provided by the handrails.

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Acquisition

2.3.1. Questionnaire

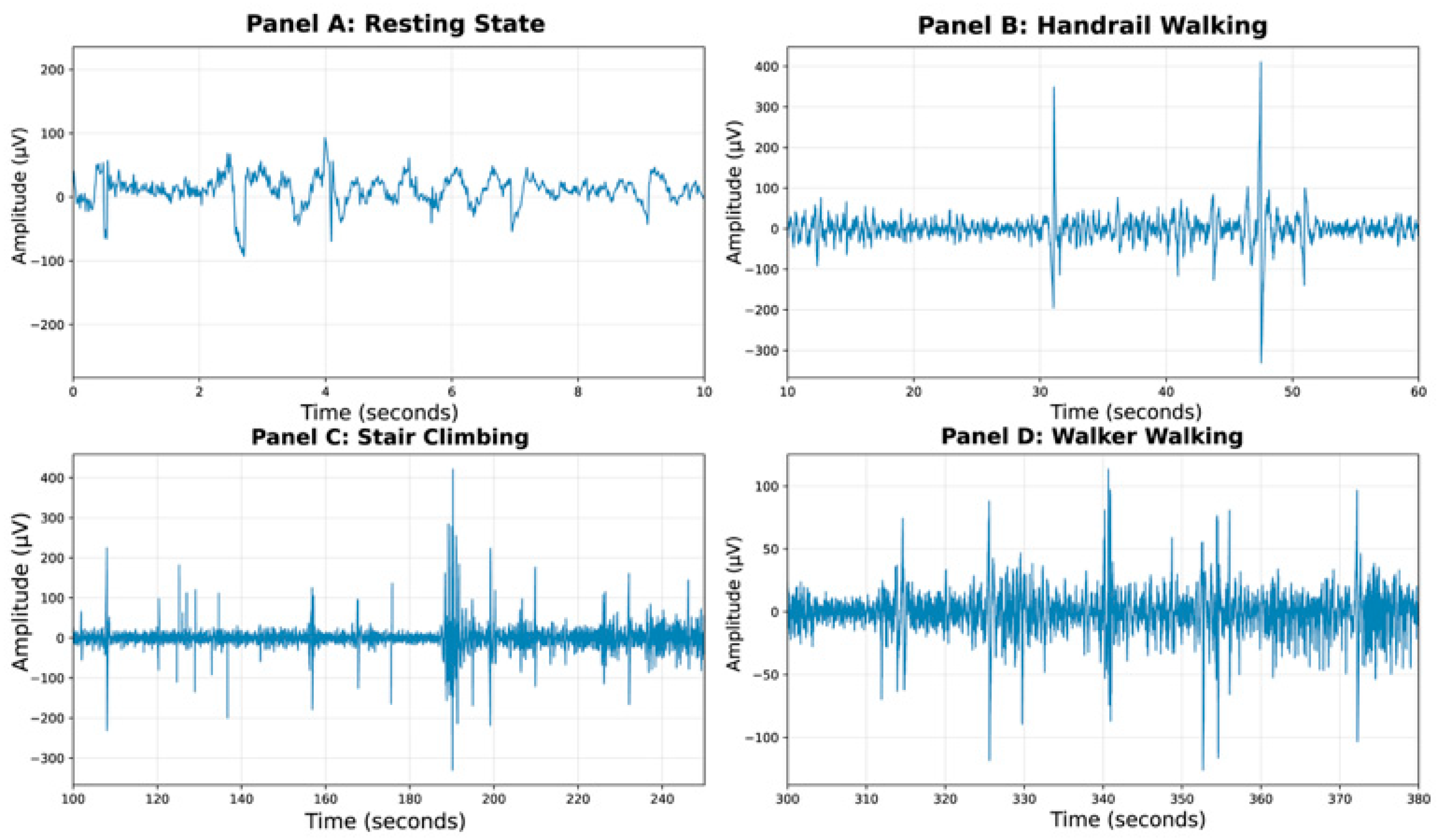

2.3.2. EEG

2.3.3. Behavior

- Define behavior: Clearly define the behavior (e.g., intervention frequency) based on the indicators in Table 2;

- Set the observation context: Standardize the observation context around a specific task (e.g., walking up and down five stairs);

- Record behavior frequency: Record the frequency of the behavior (e.g., adjusting the grip on the handle) within a fixed task unit or time interval;

- Evaluate performance: Convert the frequency counts and overall performance into a scale score using a predefined scoring scale (e.g., 0–10);

- Calculate and interpret the score: The final score is interpreted as reflecting the user’s level of trust or adaptability (e.g., fewer interventions and successful task completion indicate higher trust, while frequent corrections or task failures indicate lower trust).

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

2.4.1. Unimodal Data Processing

- Questionnaire data processing:

- EEG data processing:

- Frequency band decomposition: Five classic frequency bands were extracted using finite impulse response (FIR) filters designed with the firwin function in MNE-Python: delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–45 Hz). Although the study focused on the alpha and beta bands for trust score estimation, data from all five classical frequency bands were extracted. This comprehensive approach aligns with standard EEG processing pipelines to ensure methodological completeness. Furthermore, monitoring activity in all bands’ aids in data quality control, for instance, by identifying artifacts prevalent in specific bands like delta.

- Resting-state baseline establishment: A continuous 10 s segment from the beginning of the recording was used as the resting-state baseline. The alpha–beta power ratio was calculated from this segment using Welch’s periodogram method and used as a reference for subsequent normalization of task-related trust scores.

- Task period analysis: The task period was segmented into 3 s epochs (from −1 to +2 s around decision points), with non-overlapping windows. Band power within each epoch was computed using Welch’s method with a 2 s window length (nperseg = 1000 samples at 500 Hz sampling rate) and default 50% overlap.

- Trust scores were derived through Z-score normalization followed by hyperbolic tangent mapping. Specifically, the alpha–beta power ratios across all task epochs were first standardized into Z-scores

- Behavior data processing:

2.4.2. Multimodal Data Fusion by Fuzzy Logic Method

- Rule 1: If (EEG score is low) and (questionnaire score is low) then (output = p1)

- Rule 2: If (EEG score is low) and (questionnaire score is high) then (output = p2)

- Rule 3: If (EEG score is high) and (questionnaire score is low) then (output = p3)

- Rule 4: If (EEG score is high) and (questionnaire score is high) then (output = p4)

2.4.3. Method for Trust Dynamics Assessment

2.4.4. Method for Trust Level Classification

3. Results

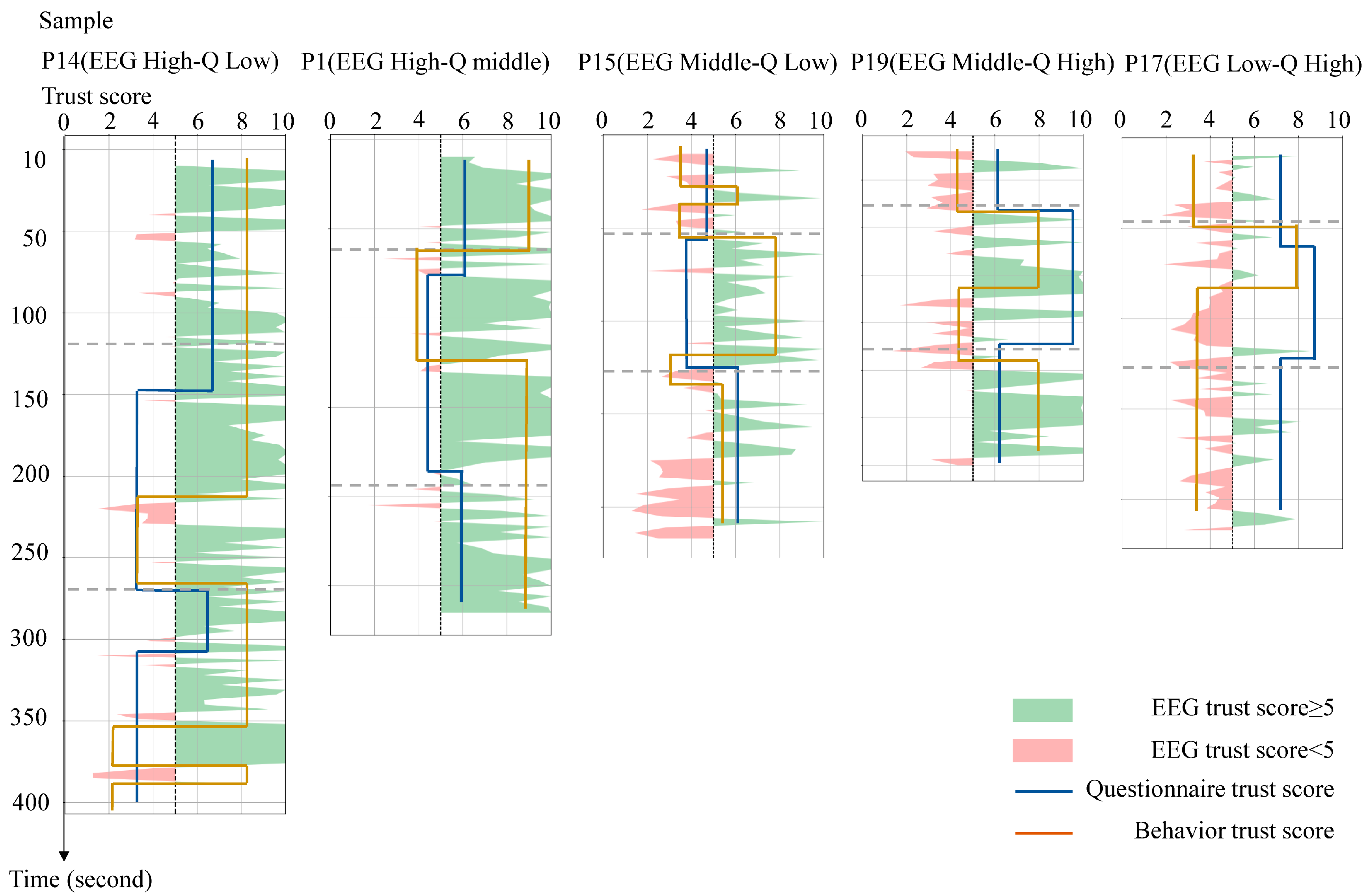

3.1. Analysis of Trust Dynamics Assessment

3.1.1. Variance Analysis of Trust Assessment

3.1.2. Correlation Analysis of Trust Assessment

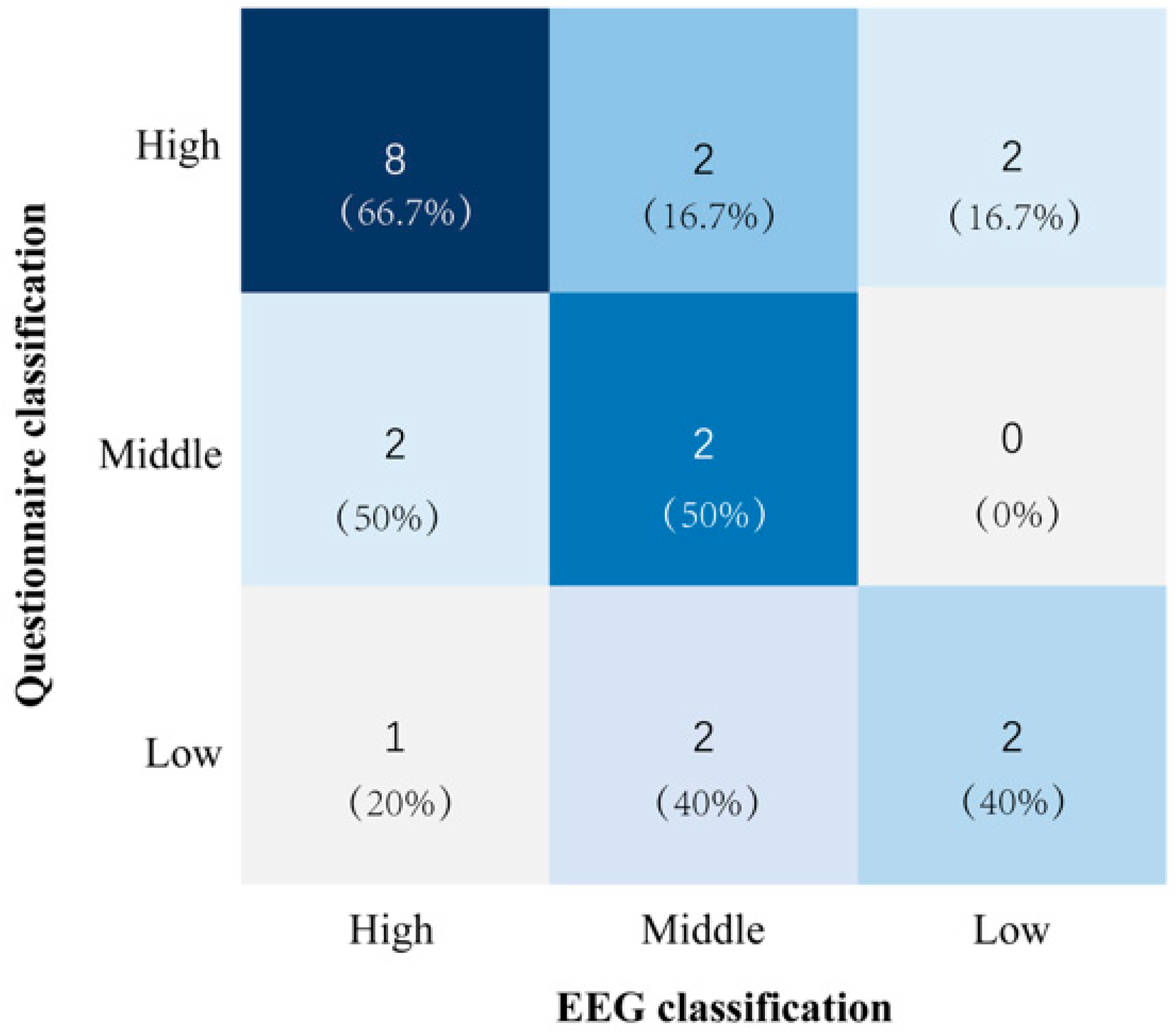

3.2. Analysis of Trust Level Classification

- High EEG/low questionnaire: Participant P14 had a high EEG confidence score (8/10), but a low questionnaire score (4/10) and moderate behavioral performance (5/10). The questionnaire was more consistent with the observed behavior, with the participant demonstrating cautious movements (e.g., total time to complete the movement 385 s) and self-reported activity limitations (e.g., “I moved slowly due to poor lower limb control”). However, the discrepancy in the high EEG score may be due to the following. (1) Physiological inhibition: reduced global neural activity due to physical weakness may mask anxiety-related signals. In contrast, motor dysfunction may reduce sensorimotor beta wave activity. (2) EMG contamination: Artifacts from frontalis muscle activity may inflate EEG-derived confidence scores by mimicking high-frequency, low-amplitude neural oscillations.

- High EEG score/medium questionnaire score: For example, Participant 1’s EEG score (9/10) was closer to his behavioral response (7.5/10) than to his neutral questionnaire response (5/10). This participant’s questionnaire responses frequently included neutral and ambiguous expressions such as “acceptable” and “indifferent”. This suggests that an ambiguous interpretation of the questions may be the reason why questionnaire scores do not reflect the actual behavior.

- Middle EEG /low questionnaire: Participant 15’s EEG (6/10) and behavioral scores (6.5/10) converged. However, on the questionnaire (4/10), the participant reported dissatisfaction with the assistive device (e.g., “the cane felt uncomfortable”). Notably, this subjective discomfort did not affect the actual task performance or EEG patterns, highlighting the disconnect between fleeting usability complaints and sustained trust.

- Middle EEG/high questionnaire: Participant 19 completed the training program quickly (174 s) and reported high confidence (8/10), but had a moderate EEG score (5/10). Observation of the participant’s behavior revealed prolonged gaze fixation on their feet during the training session, indicating a high level of focus on the task. This may explain the suppressed alpha power and elevated beta power, indicating a high level of focus on the training task, but not reflecting the participant’s overall trust level.

- Low EEG/high questionnaire: Participant 17′s EEG (4/10) and behavior (4.5/10) suggested low trust, conflicting with overly positive self-reports (“very easy”, “I am healthy”). This may reflect social desirability bias, wherein the participants overstated competence to conform to perceived expectations.

4. Discussion

4.1. EEG Demonstrates High Sensitivity to Dynamic Trust but Remains Vulnerable to Physiological Confounds

4.2. Questionnaires Provide Contextual Stability but Lack Temporal Resolution

4.3. Multimodal Fusion Optimizes the Sensitivity-Specificity Trade-Off

4.4. Implications for Trust Assessment in Lower-Limb Rehabilitation

- Implement a dynamic calibration mechanism: A dynamic calibration mechanism is crucial for accurate and reliable trust assessment. Leveraging the advantages of multimodal assessment fusion allows for integrating the real-time assessment capabilities of EEG with the rich contextual information gathered from questionnaires, enabling cross-validation and continuous calibration of different modalities. This involves the cross-validation and calibration of different modalities throughout the rehabilitation process, requiring the collection of detailed information on the trust context including physical conditions, experience with assistive devices, social support, and the participant–therapist relationship. A one-time calibration may not be sufficient to capture the evolving nature of trust; therefore, multiple trust assessment calibration iterations should be performed throughout training to provide the most accurate information for rehabilitation training decisions.

- Construct a context-aware multimodal weighting framework: A context-aware multimodal weighting framework is essential for optimizing the integration of different assessment elements. This involves identifying specific trust contexts and assigning appropriate weights to various data streams. For example, when participants are in good physical condition and feel empowered, they may be more likely to express their genuine wishes and concerns [40]. In such cases, the weight of the questionnaire should be appropriately adjusted to minimize the influence of social expectations.

- Linking trust to adaptive robotic control and rehabilitation outcomes: The trust assessment framework developed in this study can be directly translated into an input for adaptive control systems in robotic rehabilitation and assistance devices. By establishing a real-time, closed-loop system, the fused trust score (derived from EEG and subjective reports) can inform the adjustment of key robotic control parameters. For instance, when a lower-limb exoskeleton robot assists a patient in completing sit-to-stand rehabilitation training, as the patient’s trust increases, the system can gradually reduce the level of assistance provided by the device, thereby encouraging active participation and promoting neuroplasticity. Conversely, detecting a decrease in trust may trigger an increase in guiding force or a decrease in movement speed to enhance the patient’s sense of security and stability. This approach aligns with recent research analyzing how patient participation correlates with variations in impedance control parameters [41].

- Furthermore, beyond robotic control, trust levels should be linked to broader rehabilitation outcomes (e.g., adherence, functional gains, and satisfaction). This allows clinicians to identify critical trust thresholds and implement proactive measures. For example, early warning systems for declining trust can trigger personalized interventions such as motivational interviewing or adjustments to the training protocol. These advances contribute to the development of precision rehabilitation frameworks that dynamically adapt both the robotic assistance and the therapeutic strategy according to the individual’s evolving psychophysiological state.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| ANFIS | Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system |

| LOOCV | Leave-one-out cross-validation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; See, K.A. Trust in Automation: Designing for Appropriate Reliance. Hum. Factors 2004, 46, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Lee, I.-C.; Huang, H.; Liu, M. Investigating the Association of Quantitative Gait Stability Metrics With User Perception of Gait Interruption Due to Control Faults During Human-Prosthesis Interaction. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2023, 31, 4693–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinette, P.; Li, W.; Allen, R.; Howard, A.M.; Wagner, A.R. Overtrust of Robots in Emergency Evacuation Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajenaghughrure, I.B.; Sousa, S.D.C.; Lamas, D. Measuring trust with psychophysiological signals: A systematic mapping study of approaches used. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, M.; Demiris, Y. A framework for trust-related knowledge transfer in human–robot interaction. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2024, 38, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasola-Sanz, A.; Irastorza-Landa, N.; López-Larraz, E.; Bibian, C.; Helmhold, F.; Broetz, D.; Birbaumer, N.; Ramos-Murguialday, A. A hybrid brain-machine interface based on EEG and EMG activity for the motor rehabilitation of stroke patients. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotic, London, UK, 17–20 July 2017; pp. 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, K.E.; Chen, J.Y.C.; Szalma, J.L.; Hancock, P.A. A Meta-Analysis of Factors Influencing the Development of Trust in Automation: Implications for Understanding Autonomy in Future Systems. Hum. Factors 2014, 56, 1703–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavas, Z.R. A review on trust in human-robot interaction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.10045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichtmann, B.; Nitsch, V. Is the social desirability effect in human–robot interaction overestimated? A conceptual replication study indicates less robust effects. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2021, 13, 1013–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. The adjustment of social trust and Internet use on cognitive bias in social status: Perspective of performance perception. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 26, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zeng, S.; Mao, Q.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Z. Human-Machine Trust and Calibration Based on Human-in-the-Loop Experiment. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on System Reliability and Safety Engineering (SRSE), Guangzhou, China, 15–18 December 2022; pp. 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jui, J.J.; Hettiarachchi, I.T.; Bhatti, A.; Farghaly, M.R.M.; Creighton, D. A Recent Review on Subjective and Objective Assessment of Trust in Human Autonomy Teaming. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 2025, 55, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Zang, J.; Qu, X. EEG-based assessment of driver trust in automated vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 246, 123196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidas, C.A.; Lyras, D. A review of EEG-based user authentication: Trends and future research directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 22917–22934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, G.; Matthias, R. Trust assessment with eeg signals in social human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Robotics 2023, Doha, Qatar, 4–7 December 2023; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Campagna, G.; Rehm, M. A Systematic Review of Trust Assessments in Human–Robot Interaction. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot. Interact. 2025, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.M.; Rizzo, A.; Gratch, J.; Scherer, S.; Stratou, G.; Boberg, J.; Morency, L.P. Reporting Mental Health Symptoms: Breaking Down Barriers to Care with Virtual Human Interviewers. Front. Robot. AI 2016, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, N.; Bahareh, N.; Adnan, A.; Mohammad, N.R. Adaptive XAI in High Stakes Environments: Modeling Swift Trust with Multimodal Feedback in Human AI Teams. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.21158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamantini, C.; Cordella, F.; di Luzio, F.S.; Lauretti, C.; Campagnola, B.; Santacaterina, F.; Bravi, M.; Bressi, F.; Draicchio, F.; Miccinilli, S.; et al. A fuzzy-logic approach for longitudinal assessment of patients’ psychophysiological state: An application to upper-limb orthopedic robot-aided rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.I.; Mubin, O.; Shahid, S.; Orlando, J. A Systematic Review of Adaptivity in Human-Robot Interaction. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2019, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Sousa, S.; Lamas, D. Design, development and evaluation of a human-computer trust scale. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.X. Analyzing Neural Time Series Data: Theory and Practice; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 125–150. ISBN 9780262019873. [Google Scholar]

- Larson-Hall, J. A Guide to Doing Statistics in Second Language Research Using SPSS and R, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 321–345. ISBN 9780415874675. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, S.C.; De Visser, E.J.; Wiese, E.; Lee, Y.-C.; Shaw, T.H. Measurement of trust in automation: A narrative review and reference guide. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 604977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 210–235. ISBN 0070474656. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman, R.; Quera, V. Sequential Analysis and Observational Methods for the Behavioral Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 45–78. ISBN 9780521196736. [Google Scholar]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, J.M. Ideal spatial adaptation by wavelet shrinkage. Biometrika 1994, 81, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tang, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, H.; Li, X.; Di, Z.; Li, Z. Temporal segmentation of EEG based on functional connectivity network structure. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, S.S. On the psychophysical law. Psychol. Rev. 1957, 64, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-S.R. ANFIS: Adaptive-network-based fuzzy inference system. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1993, 23, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurada, J.; Wright, A.; Graham, J. A neuro-fuzzy approach for robot system safety. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C 2001, 31, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowne, D.P.; Marlowe, D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J. Consult. Psychol. 1960, 24, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, S.; Maes, M.; Stevens, G.W.J.M.; de Heer, C.; Li, J.-B.; Sun, Y.; Finkenauer, C. Trust and subjective well-being across the lifespan: A multilevel meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Psychol. Bull. 2025, 151, 737–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Yu, H. Active Training Control Method for Rehabilitation Robot Based on Fuzzy Adaptive Impedance Adjustment. Machines 2023, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Number | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | I believe that there could be negative consequences when using the rehabilitation device. |

| 2 | I feel I must be cautious when using the rehabilitation device. |

| 3 | It is risky to interact with the rehabilitation device. |

| 4 | I believe that the rehabilitation device will act in my best interest. |

| 5 | I believe that the rehabilitation device will do its best to help me if I need help. |

| 6 | I believe that the rehabilitation device is interested in understanding my needs and preferences. |

| 7 | I think that the rehabilitation device is competent and effective in its role. |

| 8 | I think that the rehabilitation device performs its role as a rehabilitation assistant very well. |

| 9 | I believe that the rehabilitation device has all the functionalities I would expect from it. |

| 10 | If I use the rehabilitation device, I think I would be able to depend on it completely. |

| 11 | I can always rely on the rehabilitation device for my training. |

| 12 | I can trust the information presented to me by the rehabilitation device. |

| Indicator | Sub-Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Compliance | Instruction adherence | Percentage of rehabilitation commands correctly executed (e.g., stepping up a step, going around an obstacle). |

| Decision time | Decision making | Time taken to make the decision to initiate an action (e.g., time from obstacle/stair recognition to action decision-making). |

| Reliance | Device reliance level | Frequency and extent of using physical help or guidance from the device (e.g., cane, handrails). |

| Intervention | Intervention frequency | Frequency of attempts to modify, correct, or pause device operation (e.g., adjust the height of the crutches, change the way gripping the handles, and adjust body balance). |

| Verification | Active verification | Frequency of additional visual or physical verification behaviors (e.g., looking at device components, touching handrails, or scanning obstacles). |

| EEG | Questionnaire | Fused Method | Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.31 | 1.93 | 3.38 | 3.66 |

| Method | Spearman | Kendall | Pearson |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.40 |

| EEG | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.58 |

| Fused | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.64 |

| Method | Kappa | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | 0.51 | 0.002 |

| EEG | 0.49 | 0.015 |

| Fused | 0.69 | 0.010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, K.; Han, F.; Li, C. Multimodal Fusion for Trust Assessment in Lower-Limb Rehabilitation: Measurement Through EEG and Questionnaires Integrated by Fuzzy Logic. Sensors 2025, 25, 6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216611

Zheng K, Han F, Li C. Multimodal Fusion for Trust Assessment in Lower-Limb Rehabilitation: Measurement Through EEG and Questionnaires Integrated by Fuzzy Logic. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216611

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Kangjie, Fred Han, and Cenwei Li. 2025. "Multimodal Fusion for Trust Assessment in Lower-Limb Rehabilitation: Measurement Through EEG and Questionnaires Integrated by Fuzzy Logic" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216611

APA StyleZheng, K., Han, F., & Li, C. (2025). Multimodal Fusion for Trust Assessment in Lower-Limb Rehabilitation: Measurement Through EEG and Questionnaires Integrated by Fuzzy Logic. Sensors, 25(21), 6611. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216611