Circular Array Fiber-Optic Sub-Sensor for Large-Area Bubble Observation, Part I: Design and Experimental Validation of the Sensitive Unit of Array Elements

Abstract

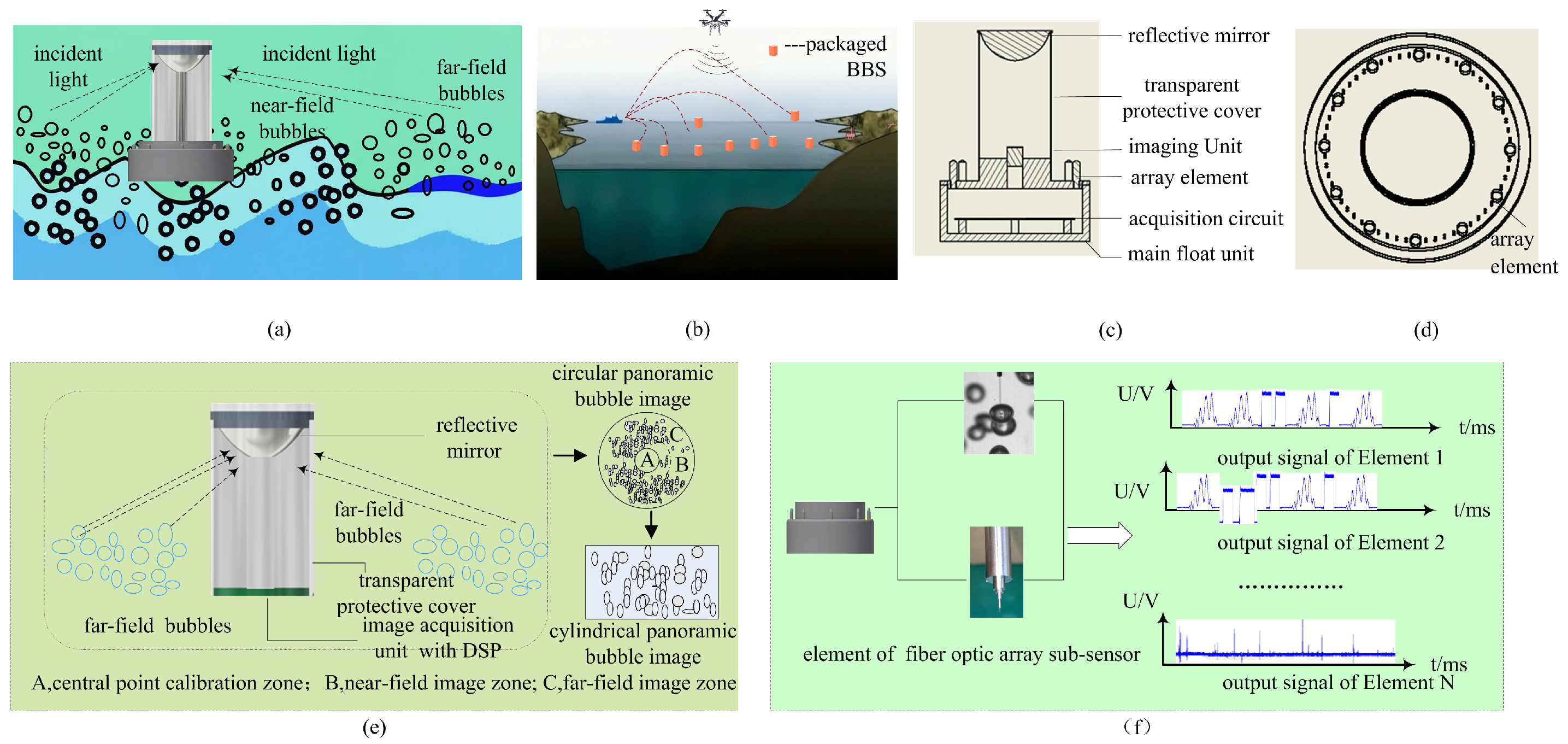

1. Introduction

2. BBS Measurement Principle

3. Optimization Method for the Sensitive Units of Circular Array Fiber-Optic Sub-Sensor Elements

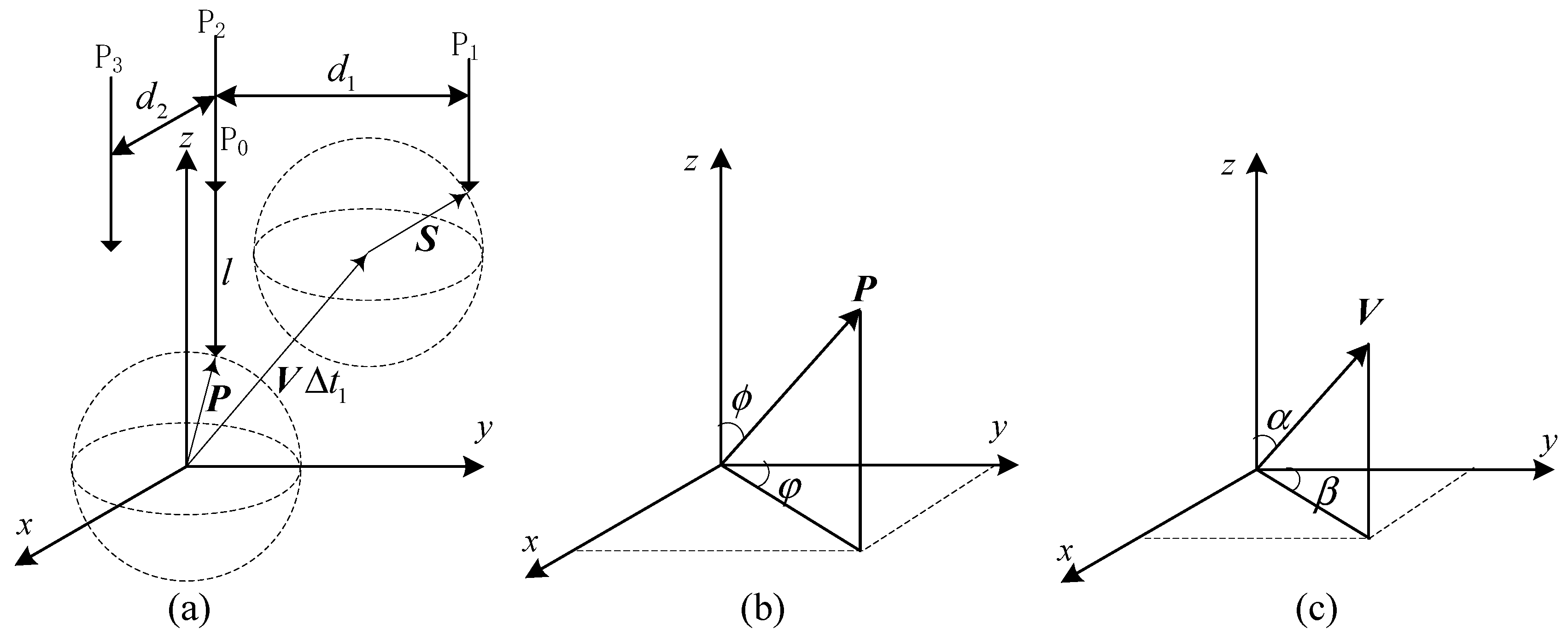

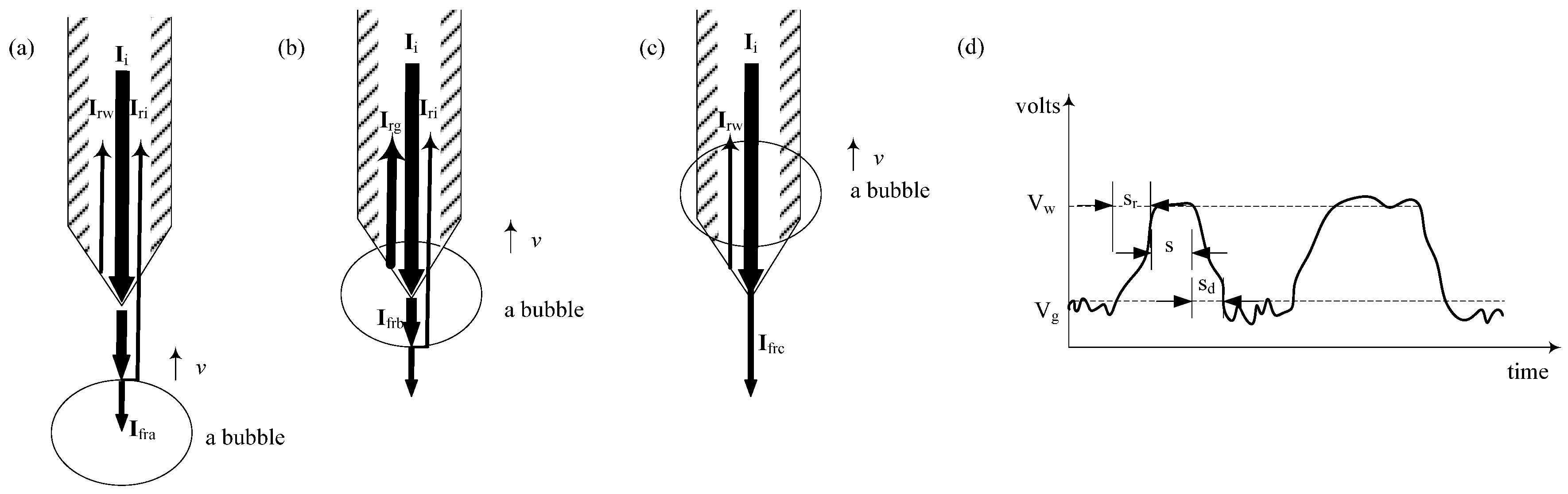

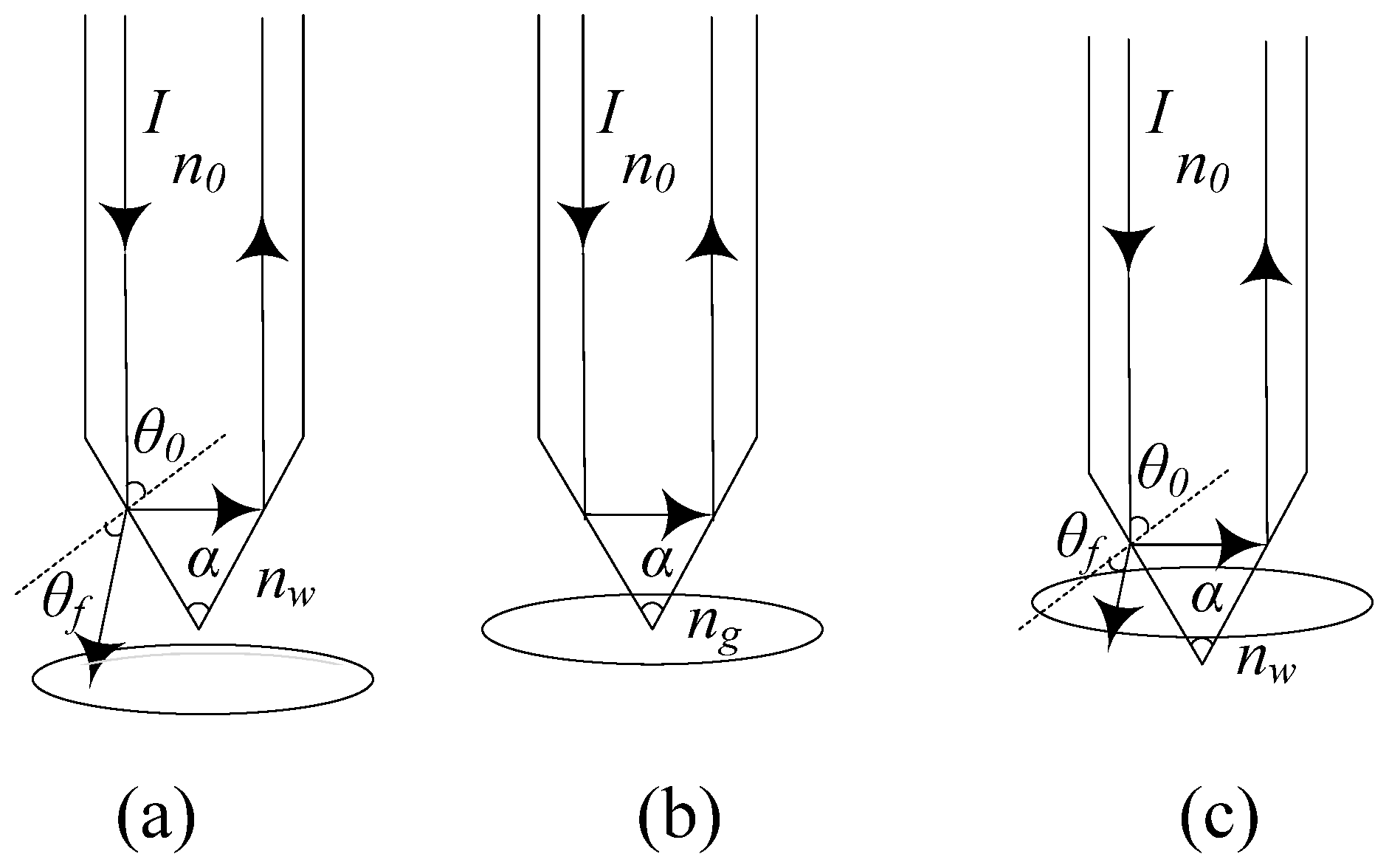

3.1. Subsection Measurement Principle of Array Elements

3.2. Key Parameter Calculation of the Sensitive Unit in the Array Element

4. Fabrication and Performance Testing of Array Elements

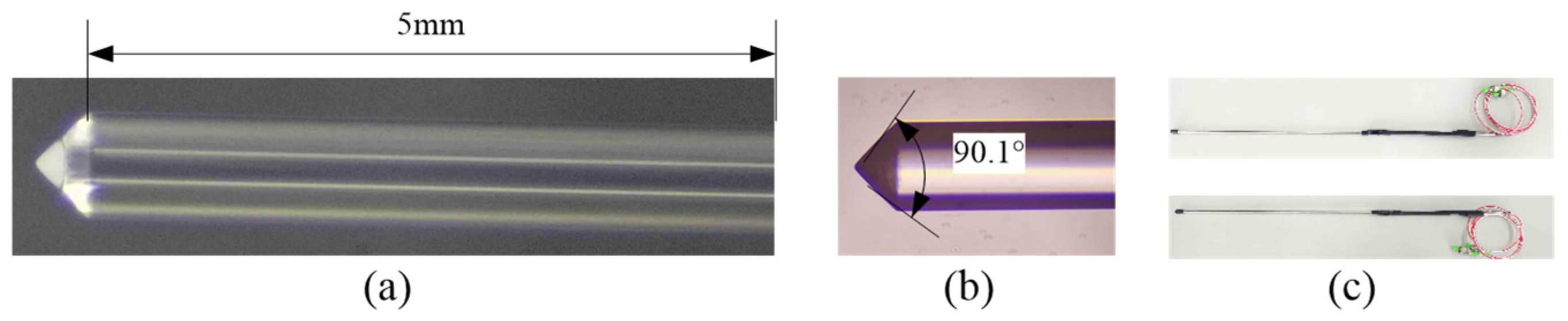

4.1. Fabrication of Array Elements

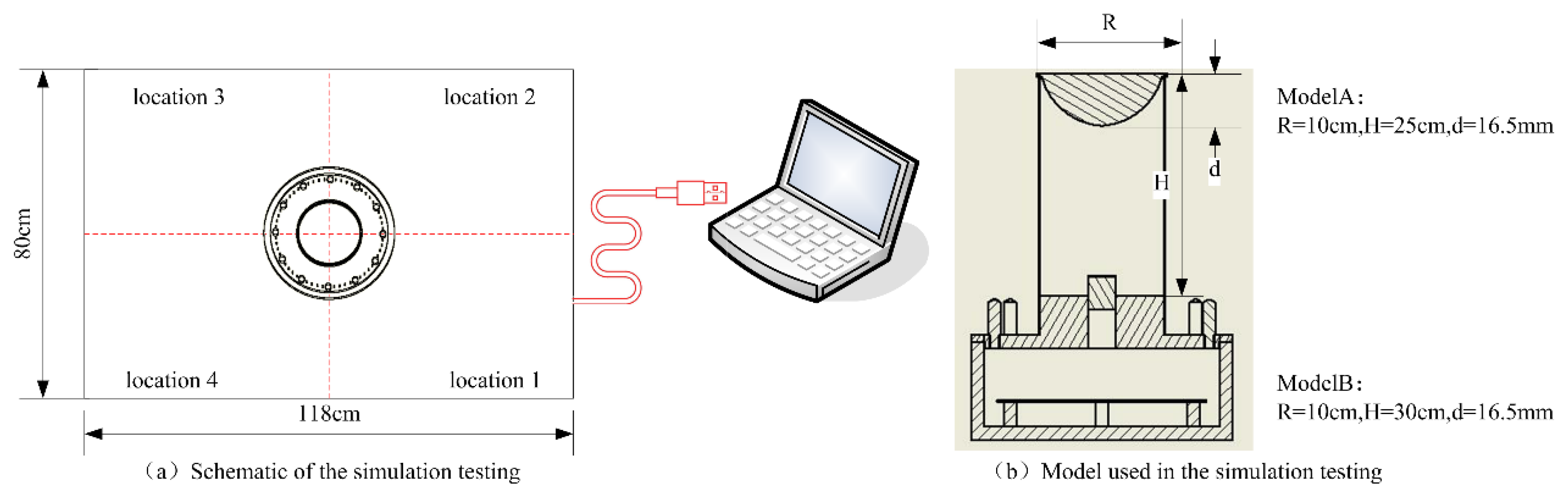

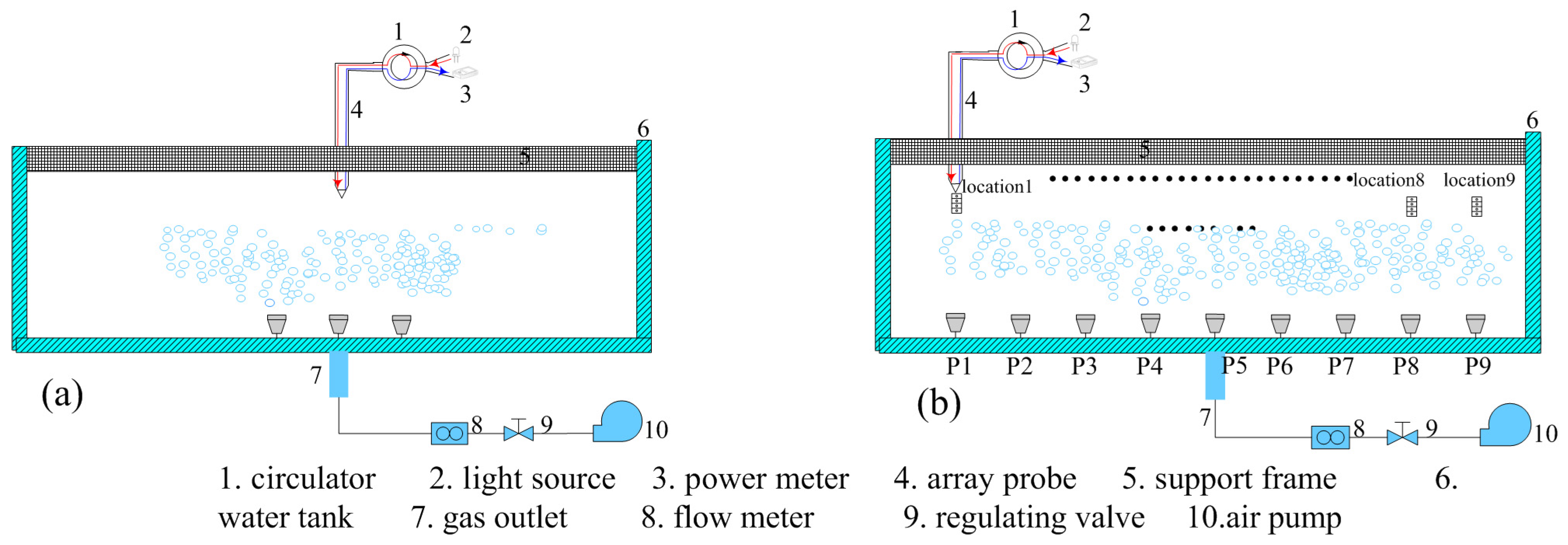

4.2. Experimental System Setup

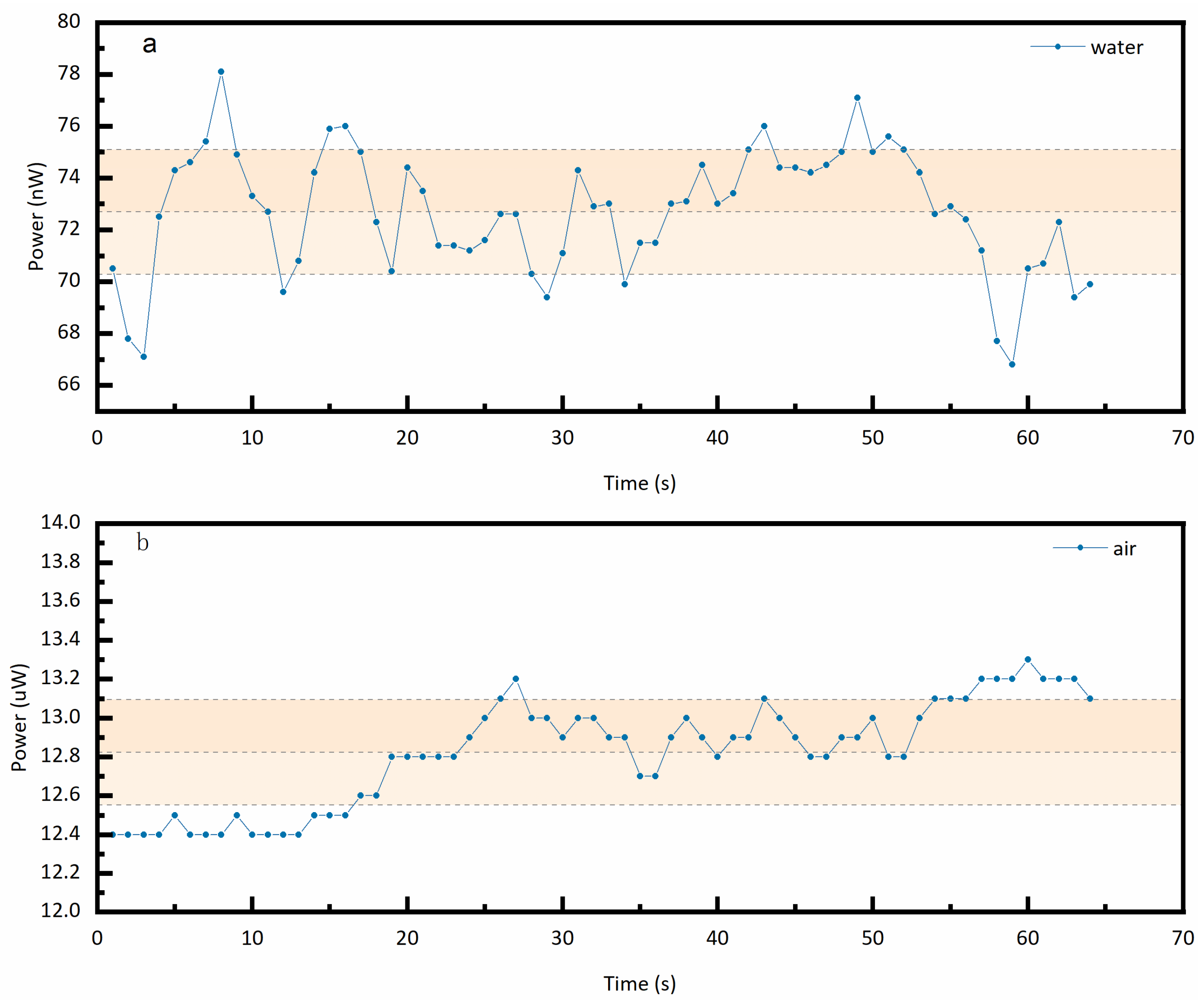

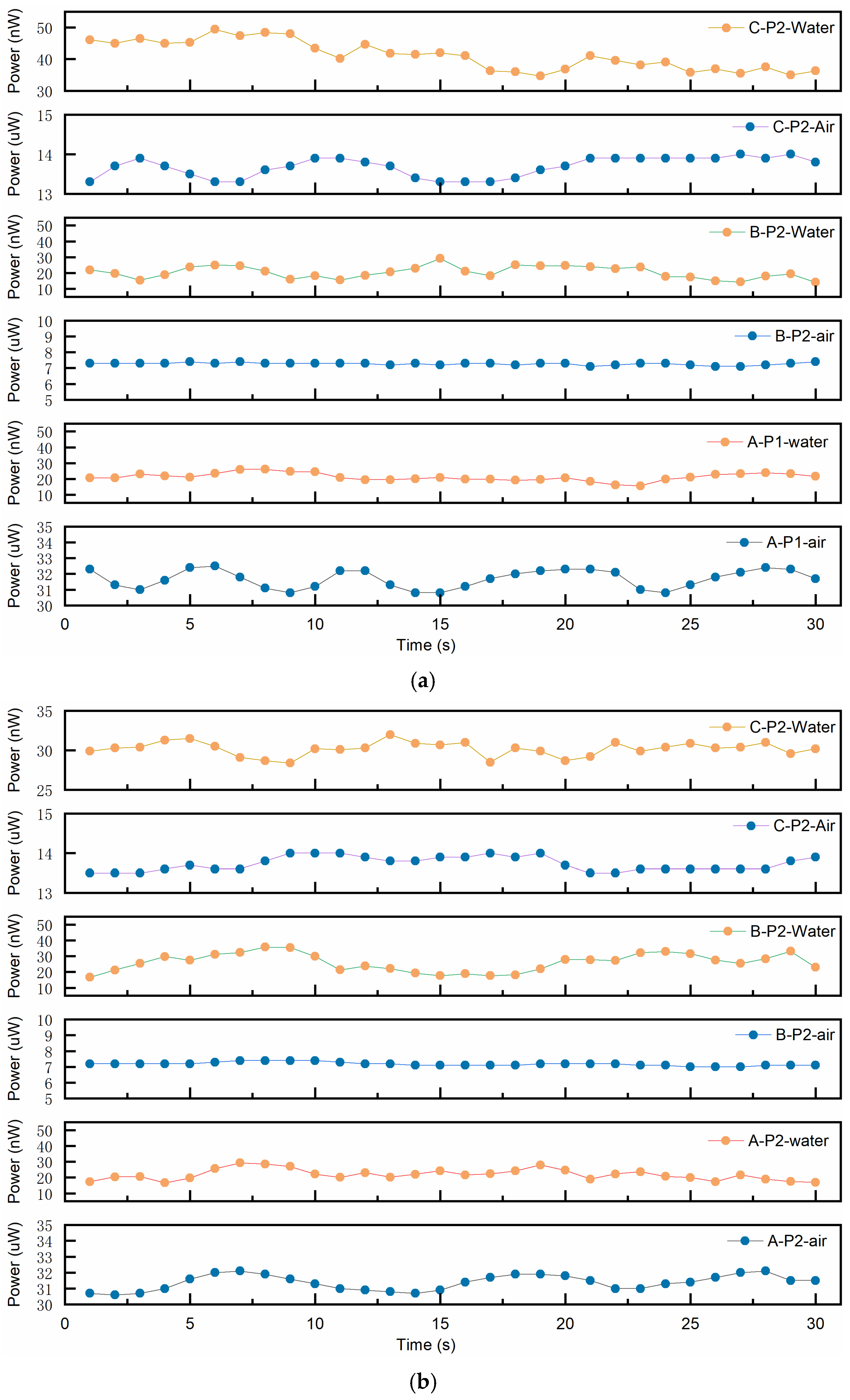

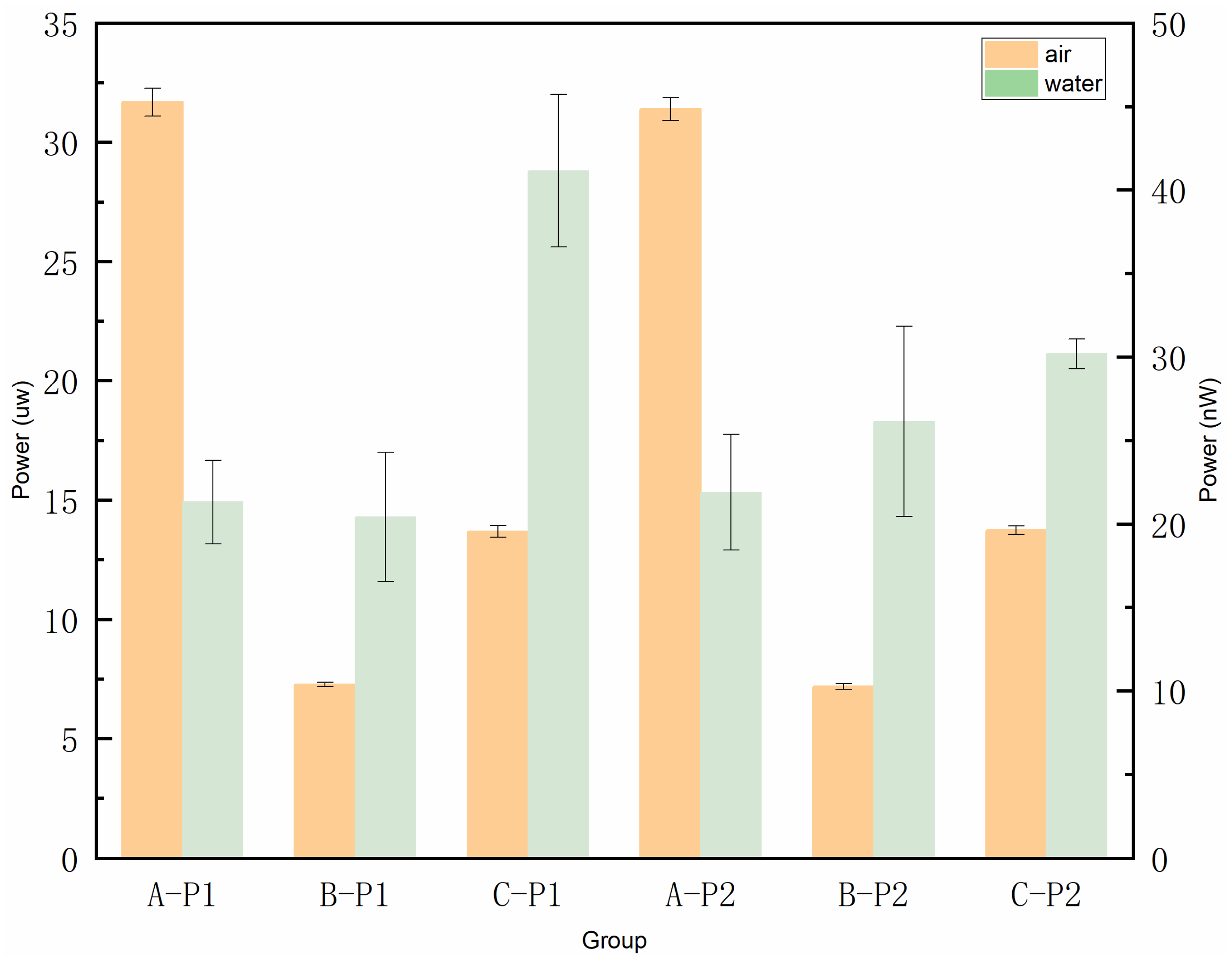

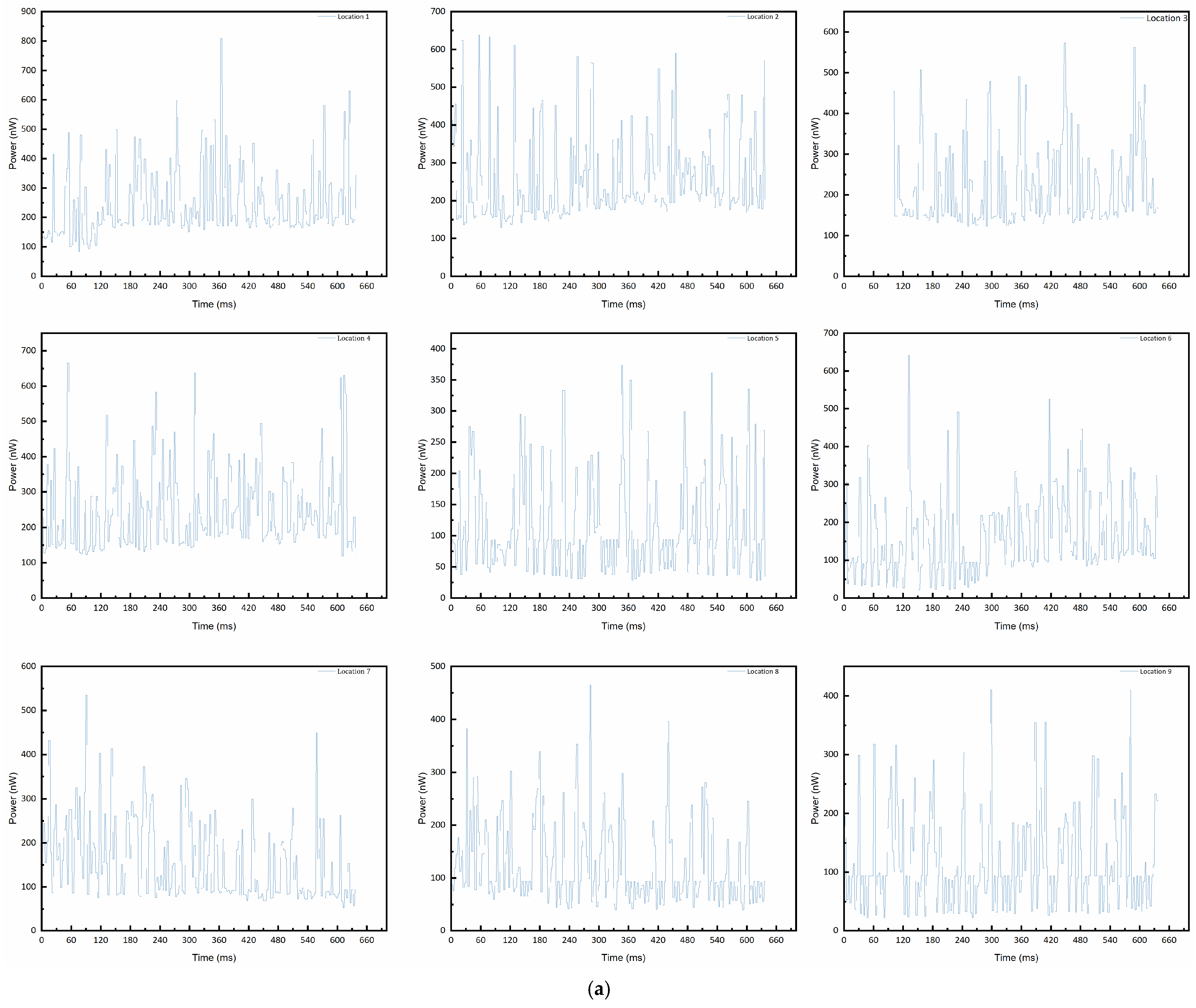

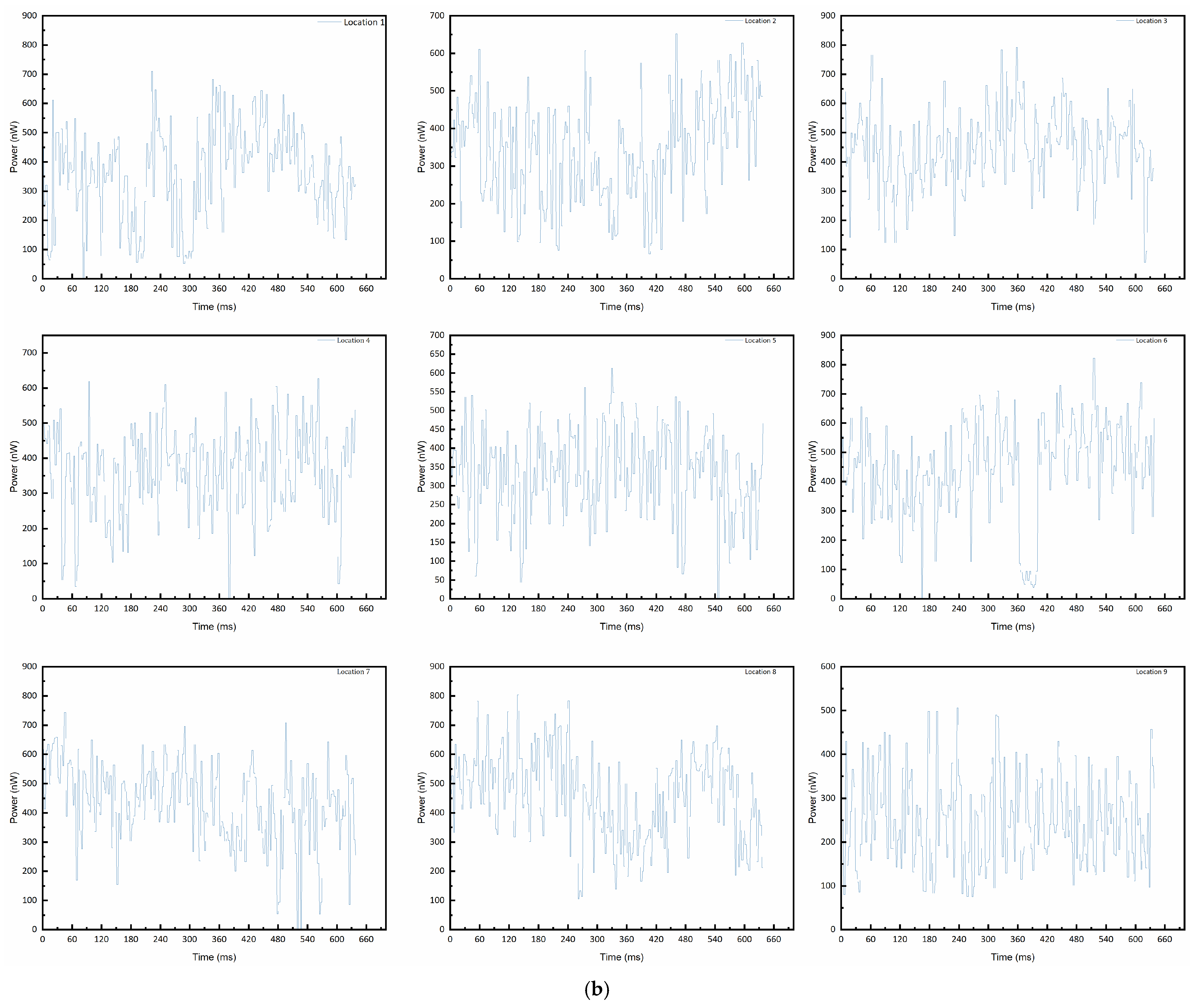

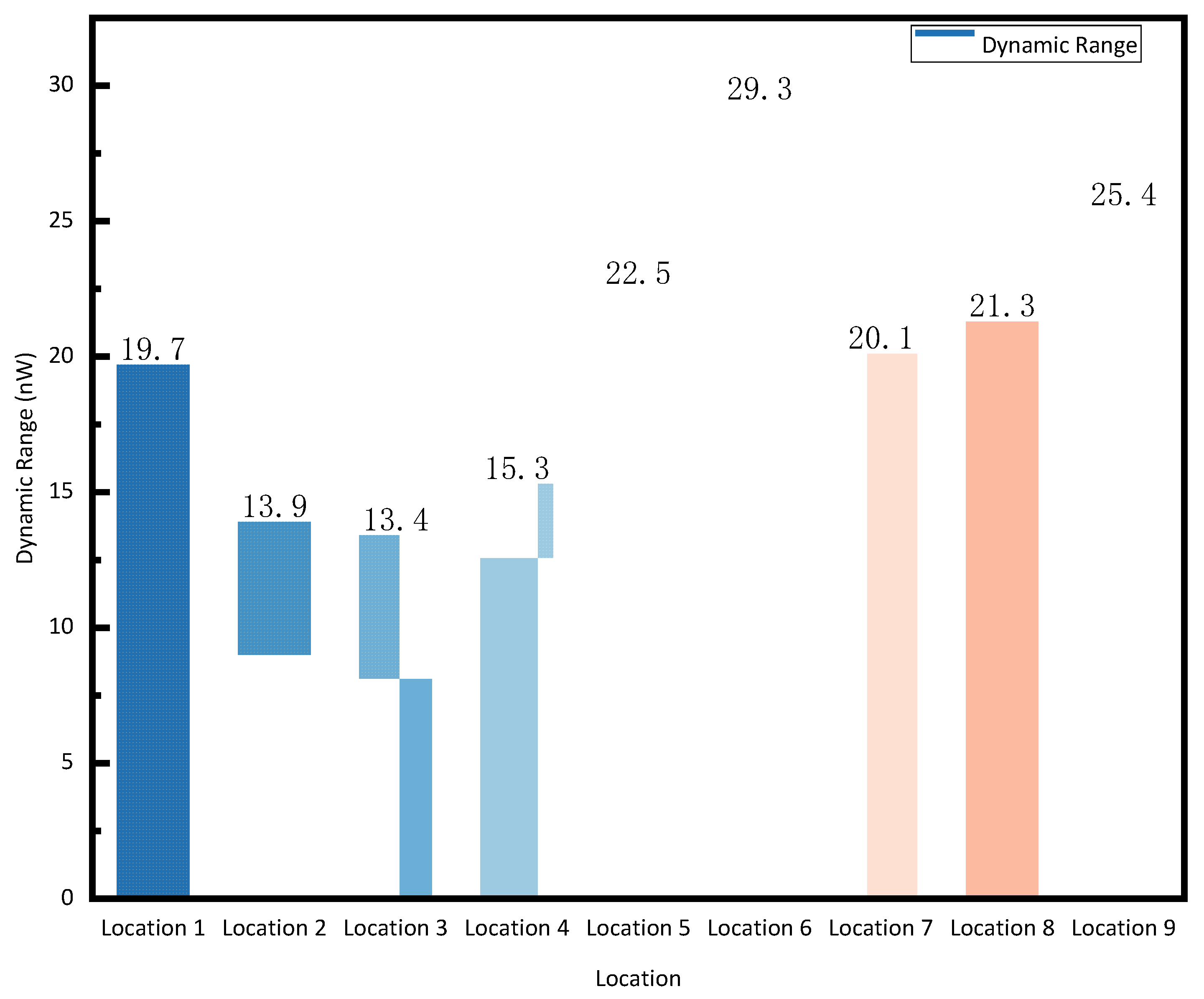

4.3. Experimental Results

- The bubble size is excessively small or the interfacial curvature is excessively large. The signal strength measured by the probe is closely related to the interfacial curvature between the bubble and the liquid. Excessively small bubbles or sharp curvature may lead to suboptimal reflection/scattering patterns of light, resulting in minimal variation in the light intensity entering the receiving optical fiber (i.e., a very weak signal).

- The probe failed to penetrate the bubble in an ideal manner (e.g., perpendicularly), instead skimming over or partially penetrating it. This results in less distinct optical changes at the interface and a reduction in signal amplitude.

- Ambient light interference: Ambient light in the experimental environment (especially indoor lighting) can be detected by the probe, creating a strong and stable DC offset background. Fluctuations in this background (e.g., due to inherent instability of the light source or reflections caused by liquid surface disturbances) directly superimpose onto the measurement signal, resulting in significant noise.

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

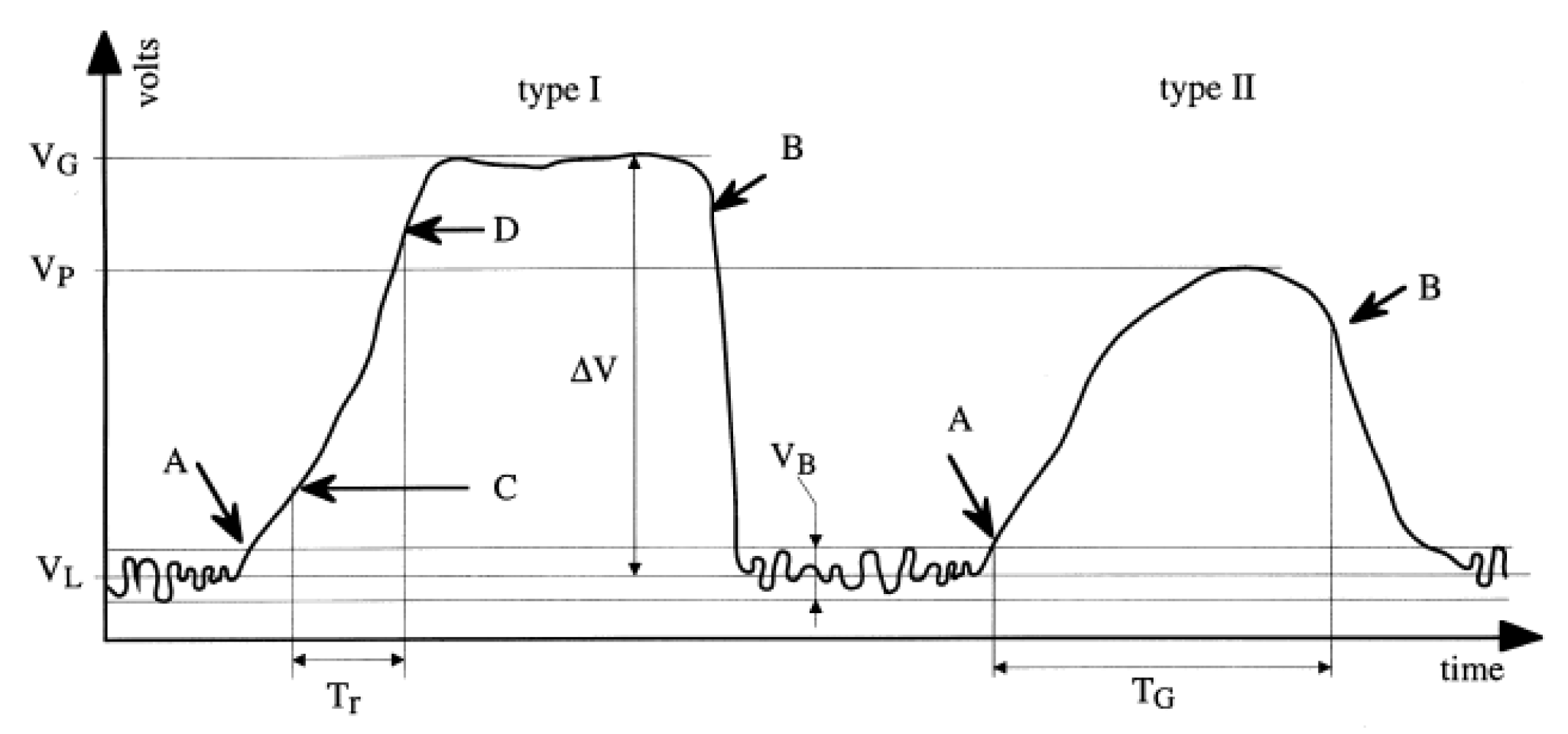

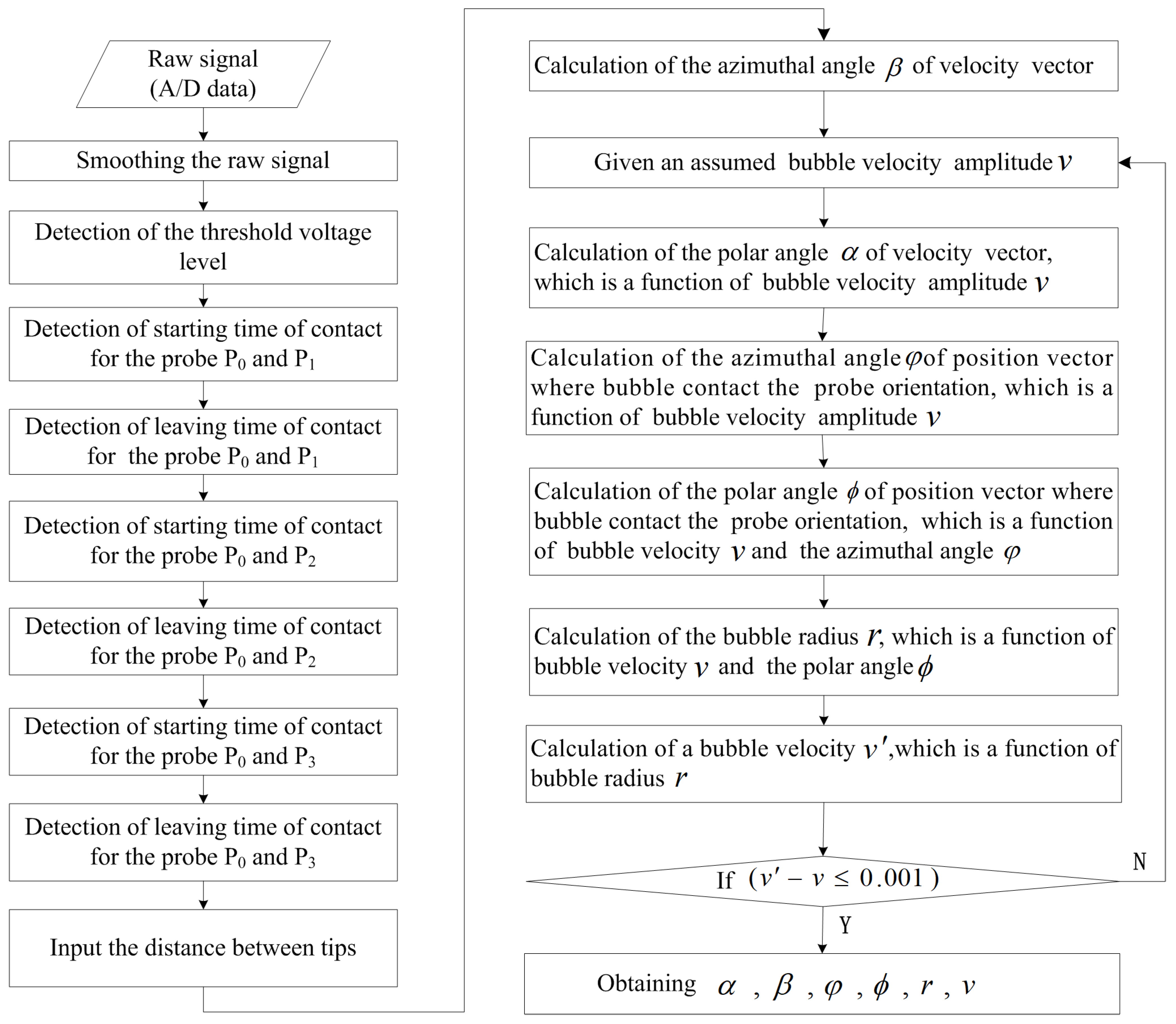

Appendix A.1. Algorithm for Calculating Bubble Parameters from Voltage Signals Acquired by Single-Array Element (Applicable to This Manuscript)

Appendix A.2. Algorithm for Calculating Bubble Parameters from Voltage Signals Acquired by Dual-Array Element

Appendix A.3. Algorithm for Calculating Bubble Parameters from Voltage Signals Acquired by Four-Array Element

Appendix B

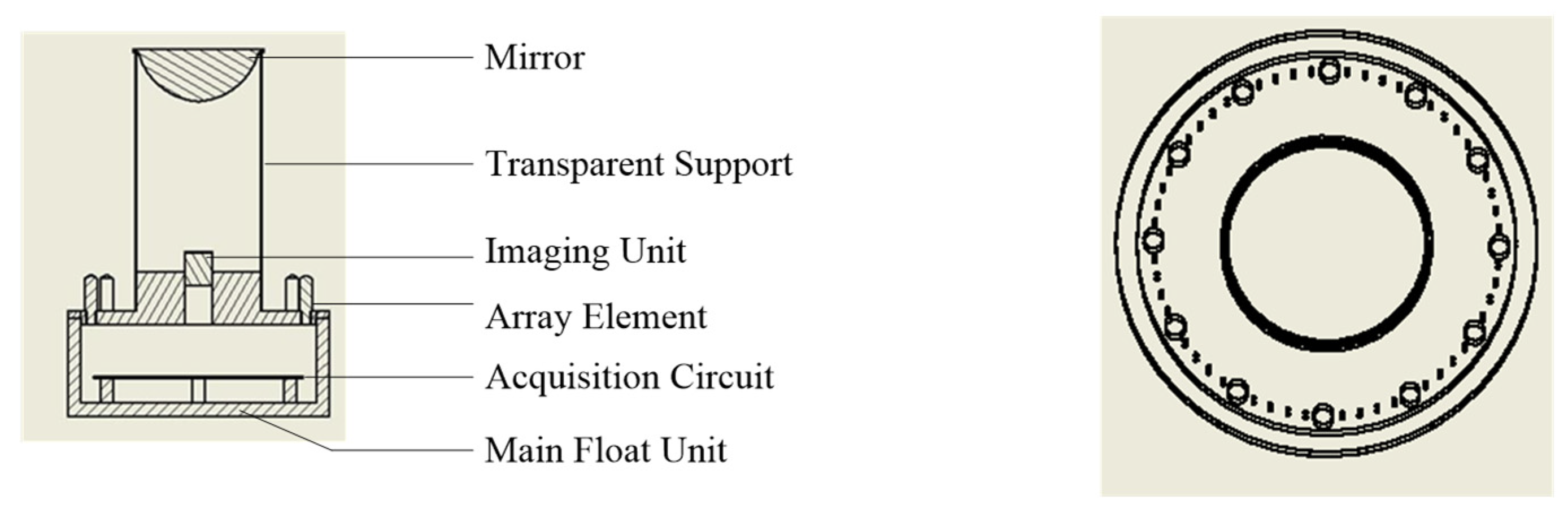

Appendix B.1. Sensor Prototype Fabrication

Appendix B.2. Sensor Prototype Testing

References

- Deike, L. Mass Transfer at the Ocean–Atmosphere Interface: The Role of Wave Breaking, Droplets, and Bubbles. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2022, 54, 191–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deike, L.; Lenain, L.; Melville, W.K. Air entrainment by breaking waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 3779–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deike, L.; Melville, W.K. Gas transfer by breaking waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 10482–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Shi, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H. Predictions of the effect of non-homogeneous ocean bubbles on sound propagation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetazzo, A.; Halsne, T.; Breivik, K.O.; Strand, A.H.; Callaghan, F.; Barbariol, S.; Davison, F.; Bergamasco, C.; Molina, C.; Bastianini, M. On the short-term response of entrained air bubbles in the upper ocean: A case study in the North Adriatic Sea. Ocean Sci. 2023, 20, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, K.; Dierssen, H.M.; Twardowski, A.; Cifuentes, L.; Zappa, C.J. Optical measurements of small deeply penetrating bubble populations generated by breaking waves in the Southern Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2014, 119, 757–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrill, E.; Melville, W.K.; Stramski, D. Bubble entrainment by breaking waves and their influence on optical scattering in the upper ocean. J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean. 2001, 106, 16815–16823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagle, S.; McNeil, C.; Steiner, N. Upper ocean bubble measurements from the NE Pacific and estimates of their role in air-sea gas transfer of the weakly soluble gases nitrogen and oxygen. J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean. 2010, 115, C12054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josset, D.; Cayula, S.; Anguelova, M.W.; Rogers, E.; Wang, D. Using space lidar to infer bubble cloud depth on a global scale. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, G.B.; Stokes, M.D. Scale dependence of bubble creation mechanisms in breaking waves. Nature 2002, 418, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerski, H.; Brooks, I.M.; Gunn, S.; Pascal, R.; Matei, A.; Blomquist, B. Ocean bubbles under high wind conditions—Part 1: Bubble distribution and development. Ocean Sci. 2022, 18, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerski, H.; Brooks, I.M.; Gunn, S.; Pascal, R.; Matei, A.; Blomquist, B. Ocean bubbles under high wind conditions—Part 2: Bubble size distributions and implications for models of bubble dynamics. Ocean Sci. 2022, 18, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhti, M.; Thomson, J.; Bassett, C.; Malila, M.; Kirby, J.T. Statistics of bubble plumes generated by breaking surface waves. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2023, 129, e2023JC019753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.; Moulton, M.; Klerk, A.; Talbert, J.; Guerra, M.; Kastner, S.; Smith, M.; Schwendeman, M.; Zippel, S.; Nylund, S. A new version of the SWIFT platform for waves, currents, and turbulence in the ocean surface layer. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/OES Twelfth Current, Waves and Turbulence Measurement (CWTM), San Diego, CA, USA, 10–13 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, R.W.; Yelland, M.J.; Srokosz, M.A.; Moat, B.I.; Waugh, E.M.; Comben, D.H.; Cansdale, A.G.; Hartman, M.C. A Spar Buoy for High-Frequency Wave Measurements and Detection of Wave Breaking in the Open Ocean. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2011, 28, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, S.J.; Brooks, I.M.; Moat, B.I.; Yelland, M.J.; Leeuw, G.; Pascal, R.W.; Brooks, B. Near-surface measurements of sea spray aerosol production over whitecaps in the open ocean. Ocean Sci. 2013, 9, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Lashi, R.S.; Gunn, S.R.; Webb, E.G.; Czerski, H. A Novel High-Resolution Optical Instrument for Imaging Oceanic Bubbles. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 43, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Welter, K.; Mccreary, D.; Reyes, J.N. Theoretical studies on the design criteria of double-sensor probe for the measurement of bubble velocity. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2002, 12, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdula, C.D.; Loewen, M.R. Experiments investigating the use of fiber-optic probes for measuring bubble-size distributions. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 1998, 23, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Chaplin, J.R. Bubble size measurements in breaking waves using optical fiber phase detection probes. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2010, 35, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Chaplin, J.R. Void fraction measurements and scale effects in breaking waves in freshwater and seawater. Coast. Eng. 2011, 58, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrau, E.; Rivière, N.; Poupot, C.; Cartellier, A. Single and double optical probes in air-water two-phase flows: Real time signal processing and sensor performance. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1999, 25, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, G.; Loewen, M. Fiber-optic probe measurements of void fraction and bubble size distributions beneath breaking waves. Exp. Fluids 2007, 43, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartellier, A. Optical probes for local void fraction measurements: Characterization of performance. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1990, 61, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Ishii, M. Sensitivity study on double-sensor conductivity probe for the measurement of interfacial area concentration in bubbly flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 1999, 25, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.L. A model for measuring the velocity vector of bubbles and the pierced position vector in breaking waves using four-tip optical fiber probe, Part I: Computational method. Ocean Eng. 2018, 161, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Improvement Project | Improvement Plan Conception |

|---|---|

| Platform stability cause by waves | Add attitude sensors and implement motion compensation before mapping the omnidirectional bubble image and the panoramic bubble image. |

| Adaptability to temperature and humidity | The transparent support column is embedded with resistance wire, equipped with a temperature sensor and control circuit, and a desiccant is provided. |

| Adaptability to high salt corrosion | Make the acrylic glass (polymethyl methacrylate, PMMA) in the prototype more weather-resistant acrylic glass. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, F.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Chen, Z. Circular Array Fiber-Optic Sub-Sensor for Large-Area Bubble Observation, Part I: Design and Experimental Validation of the Sensitive Unit of Array Elements. Sensors 2025, 25, 6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206378

Liu F, Yang L, Li H, Chen Z. Circular Array Fiber-Optic Sub-Sensor for Large-Area Bubble Observation, Part I: Design and Experimental Validation of the Sensitive Unit of Array Elements. Sensors. 2025; 25(20):6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206378

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Feng, Lei Yang, Hao Li, and Zhentao Chen. 2025. "Circular Array Fiber-Optic Sub-Sensor for Large-Area Bubble Observation, Part I: Design and Experimental Validation of the Sensitive Unit of Array Elements" Sensors 25, no. 20: 6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206378

APA StyleLiu, F., Yang, L., Li, H., & Chen, Z. (2025). Circular Array Fiber-Optic Sub-Sensor for Large-Area Bubble Observation, Part I: Design and Experimental Validation of the Sensitive Unit of Array Elements. Sensors, 25(20), 6378. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25206378