1. Introduction

The mechanical properties of food are crucial for its texture, processing, and consumer acceptance. There are various methods for testing these properties, depending on the objective (e.g., firmness, elasticity, viscosity), because texture is not only a sensory quality characteristic but also a technologically relevant parameter. Objective measurement of these properties is achieved through a variety of instrumental methods, including compression tests, shear analysis, and rheological measurements, which are increasingly complemented by imaging techniques [

1].

In particular, in meat processing, the precise determination of texture—for example, using the Warner–Bratzler shear test [

2,

3] or Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) [

4]—is essential for assessing tenderness, juiciness, and fiber structure. Simultaneously, sensory methods, such as trained sensory panels, provide valuable subjective data that often, albeit not always, correlate with instrumental results [

5] and are used for validation [

1,

6].

Food physics provides a comprehensive theoretical foundation, systematically describing and quantifying the mechanical, thermal, and rheological properties of food. Modern developments in process automation and the use of online sensors enable continuous quality control throughout the entire production chain [

1].

As regards meat and meat products, Warner-Bratzler shear tests and Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) are still widely used in quality control and product development. The Warner–Bratzler method reports force–distance data for shearing a specimen with defined diameter and can give information not only on the maximum force needed to shear the specimen but also on its fracturability/brittleness. Similarly, TPA reports force–distance data, but for two consecutive compression–relaxation cycles. From the maximum forces and the areas under the curves (“work”), some material characteristic can be derived [

7]. For example, the hardness is the maximum force during compression; the resilience is the ratio of the upstroke energy of the first compression by the downstroke energy of the first compression [

7]. Data from both compression–relaxation cycles can be used to calculate characteristics as chewiness, springiness, etc., related to the sensations consumers experience during chewing foods, thus the colloquial name “two-bite test” for TPA.

Yet, such devices are costly and not portable. Likewise, maintaining a panel of trained testers is often not feasible. Arguably, the provision of a small, inexpensive and easy-to-operate texture tester would allow also smaller food businesses to examine the textural quality of their products.

Recently, an accelerometer-equipped texture testing device (Vienna Surface Tester (VST)) has been developed [

8]. A scaled-down version (Surface Tester of Food Resilience (STFR)) of said device has been proposed as a food texture tester. Whereas the original device operates in free fall, the probe of the scaled-down device follows a circular, arc-shaped path. Both devices use a sphere equipped with accelerometers. The sphere is dropped onto the specimen’s surface and eventually bounces back. Changes in acceleration over the measurement duration are recorded (see

Section 2.1) and some material characteristic values are calculated, e.g., the spring constant, Young’s Modulus, and Energy Recovery [

8].

As regards shear force, a preliminary study showed correlations for shear force (Warner–Bratzler) with spring constant (STFR), Young’s Modulus, and Resonance Frequency for solid foods [

9], albeit for drop heights of 25 mm and 50 mm only, and with a less refined rig and software.

However, for TPA, such a comparison is lacking. This was mainly due to the finding that the current mode of data processing in the STFR is inaccurate at dropping heights exceeding 17 mm [

10]. This is due to the fact that the calculations performed by the current version of the STFR tester rely on a free-fall model.

In order to obtain correct data for other drop heights, formulae describing the movement of the sphere have been elaborated [

10], based on a hammer, or a free fall/hammer average model instead of a free-fall-only model.

The aim of this article is to compare the outcomes of said formulae with raw data retrieved from the device and from image analysis of high-speed video recordings in order to select the most appropriate formulae for the sphere’s movement; and, second, to derive formulae for material characteristics from these identified formulae.

These formulae will allow a thorough comparison of the STFR-generated results for spring constant and penetration depth to TPA generated values for Hardness. Likewise, we assume a relation of Energy Recovery (STFR) with Resilience (TPA). For a comparison of TPA variables relying on two compression-relaxation-cycles, the formulae presented in our manuscript will be simply applied on the first and on the second drop-bounce-cycle.

In

Section 2.1 and

Section 3.1, we describe the principle of operation and the parameters to be validated.

Section 2.2 describes statistical procedures and software used. In

Section 2.3, the setup for kinematic analysis of the travel of the STFR probe by high-speed image analysis is detailed.

Section 2.4 defines the variables considered for comparison of model-generated data with STFR and image analysis, whereas in

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5, the outcomes of said comparisons are presented, resulting in identifying the best-matching formulae among the set specified in [

10].

Section 3.6 summarizes the appropriate formula for characterizing material properties.

Section 2.5 and

Section 3.7 present the design of an MS-Access

®-based data processing and recording application.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Device and Principle of Operation

The main components of the STFR are a spherical probe, which is attached to a swivel via a carbon-fiber rod, a data-recording and -processing unit and a magnetic release mechanism (

Figure 1). A prototype (version 2015, Vienna, Austria) with electromagnetic release is shown in

Figure 1a, whereas a more rugged design (used from 2023 onwards) allowing more reproducible adjustments is depicted in

Figure 1b.

Before measurement, the probe is positioned at a predefined height above the specimen and held by an electromagnet. By breaking the circuit of the electromagnet, the probe is released and falls along a circular trajectory until touching the specimen. Depending on the nature of the specimen, the probe will indent the surface of the specimen to some extent and bounce back. The cycle of downward and upward travel is repeated, albeit with decreasing amplitude, until the probe comes to rest on the specimen’s surface.

Since the circuit remains interrupted until the next measurement, no interference with magnetic forces is expected.

During the movement of the sphere, acceleration is sensed by two built-in accelerometers and time and changes in speed are recorded [

8].

Table 1 lists the variables recorded by the STFR and their units.

Based on these recorded data, we elaborated formula sets to calculate the surface characterization parameters. The formula sets are based on mathematical-physical models developed in a previous study [

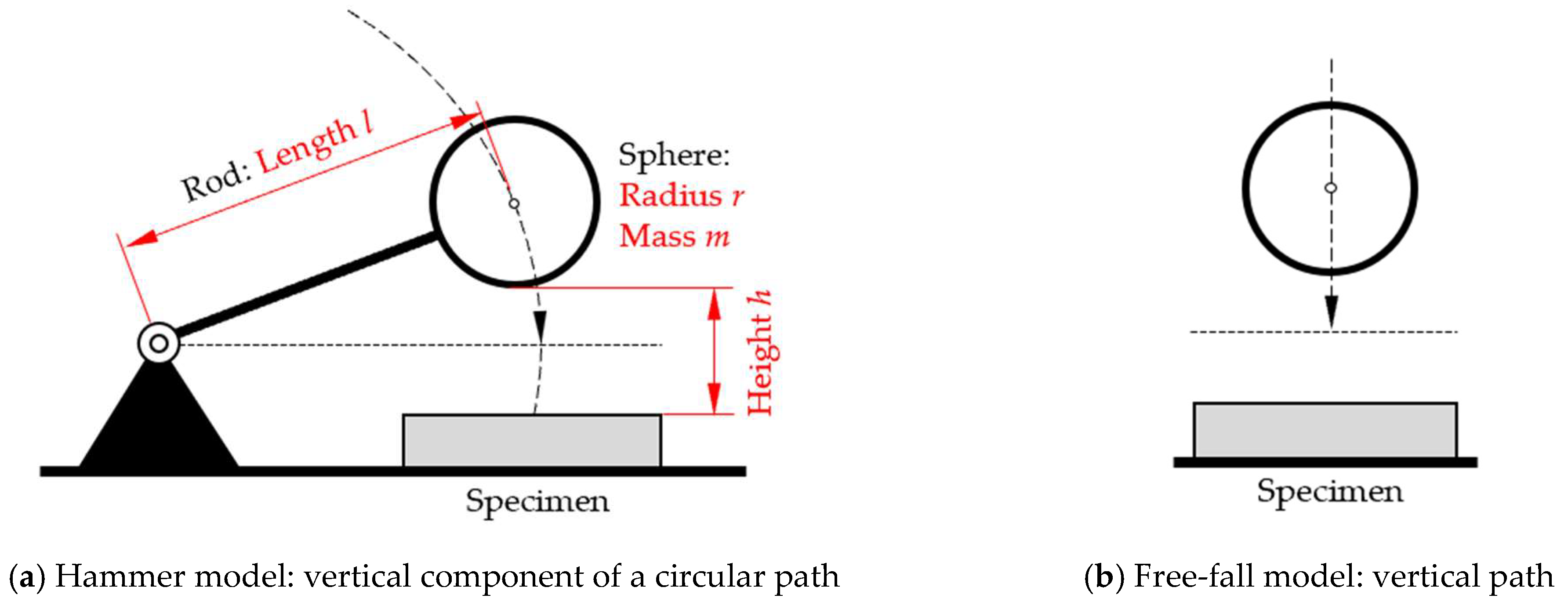

10]. These models either consider the circular path of the sphere, like the movement of a hammerhead (“hammer model”,

Figure 2a), or assume a vertical travel (“free-fall model”,

Figure 2b) or use an arithmetic average of the results of both models (“average model”). The derivation of the models is described in [

10]. For any calculation in this study, we used mass of the sphere

m = (0.104 ± 0.001) kg, length of the rod

l = (170 ± 1) mm, and gravitational acceleration

g = 9.81 m·s

−2.

2.2. Computational Procedures and Statistics

Per experimental settings, five replicate measurements were made. Mean value and standard error were calculated with Microsoft Excel® V. 2406 Microsoft 365 for Enterprise. The standard error was calculated as , where s = standard deviation and n = number of replicate measurements.

Values calculated using formulas are given with their maximum error. For a given formula, for example,

and a point

, the function value

is calculated as

and its maximum error as

. The formulas and error calculations used in this article were derived in [

8,

10] and

File S2. The calculations are performed with PTC Mathcad Prime 10.0.1.0.

The movement data (times and heights) determined using the Kinovea 0.9.5 software (

www.kinovea.org (accessed on 2 June 2024)) are further processed in Microsoft Excel

®.

2.3. Setup for the Kinematic Analysis

2.3.1. Placement of the Camera Relative to the STFR

The travel of the sphere was recorded with a high-speed camera (Sony RX100 M4; Sony, Tokyo, Japan). The camera axis was the perpendicular left side of the STFR. The distance of the front of the camera objective to the center of the sphere was 365 mm, and the center of the lens and the center of the sphere were aligned on a horizontal axis. Since the distance from lens to sphere is large compared to the diameter of the sphere, perspective distortion was not considered.

2.3.2. Setup of the STFR to Determine the Influence of the Initial Position of the Sphere

We studied if and how the falling time T0 is affected when the initial position of the sphere is changed. To this end, thickness of the specimen was set to 25 mm, and the starting position was adjusted to give a distance ∆x between the top surface of the specimen to the lowest part of the sphere of 25 mm and to ensure that the rod is in horizontal position when the sphere impacts the specimen.

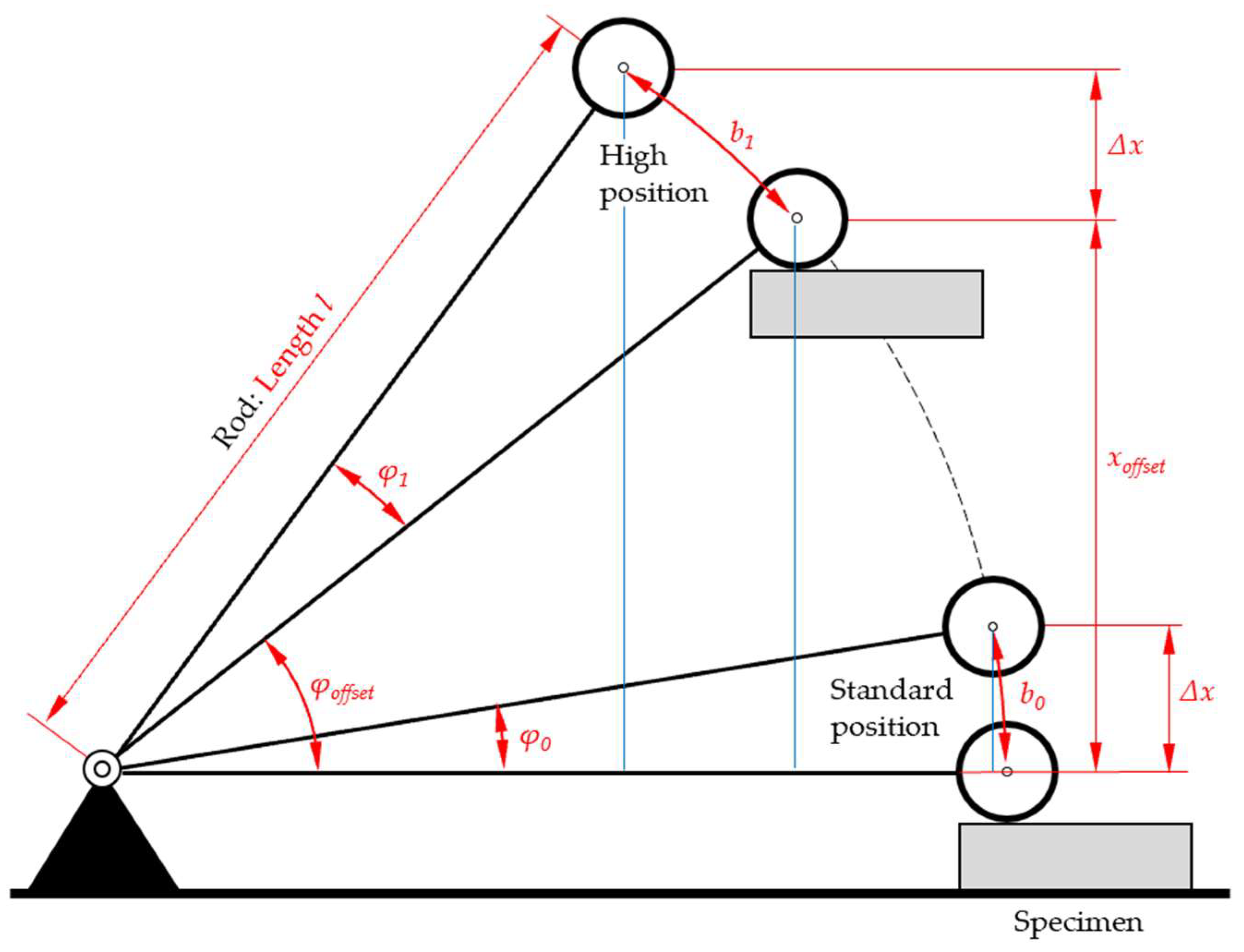

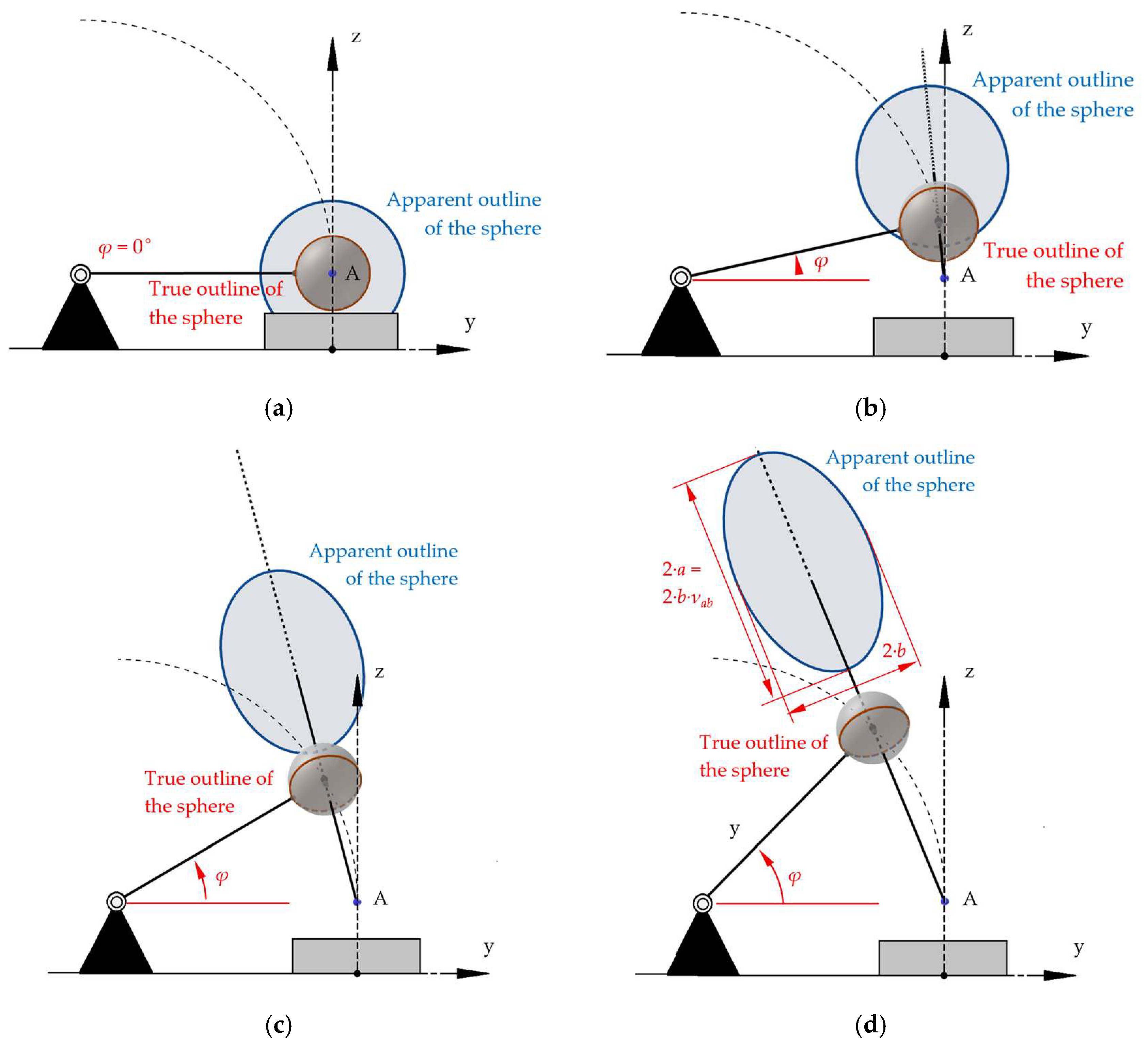

Any change in the initial height (“high position”) of the sphere corresponds to a change in the elevation angle of the rod and will result in an inclined position of the rod at the time of impact of the sphere, represented by the angle

φoffset; see

Figure 3.

The effect of

φoffset on the time to impact

T0 was assessed experimentally. The specimen’s surface was positioned in different heights relative to the baseplate (

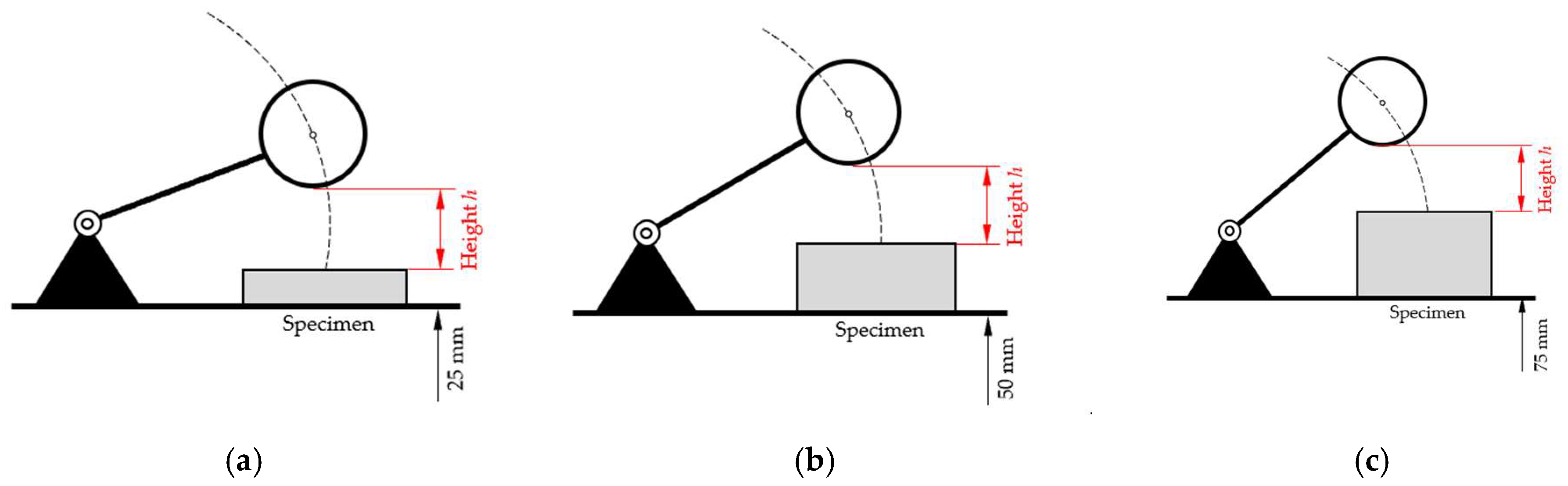

Figure 4).

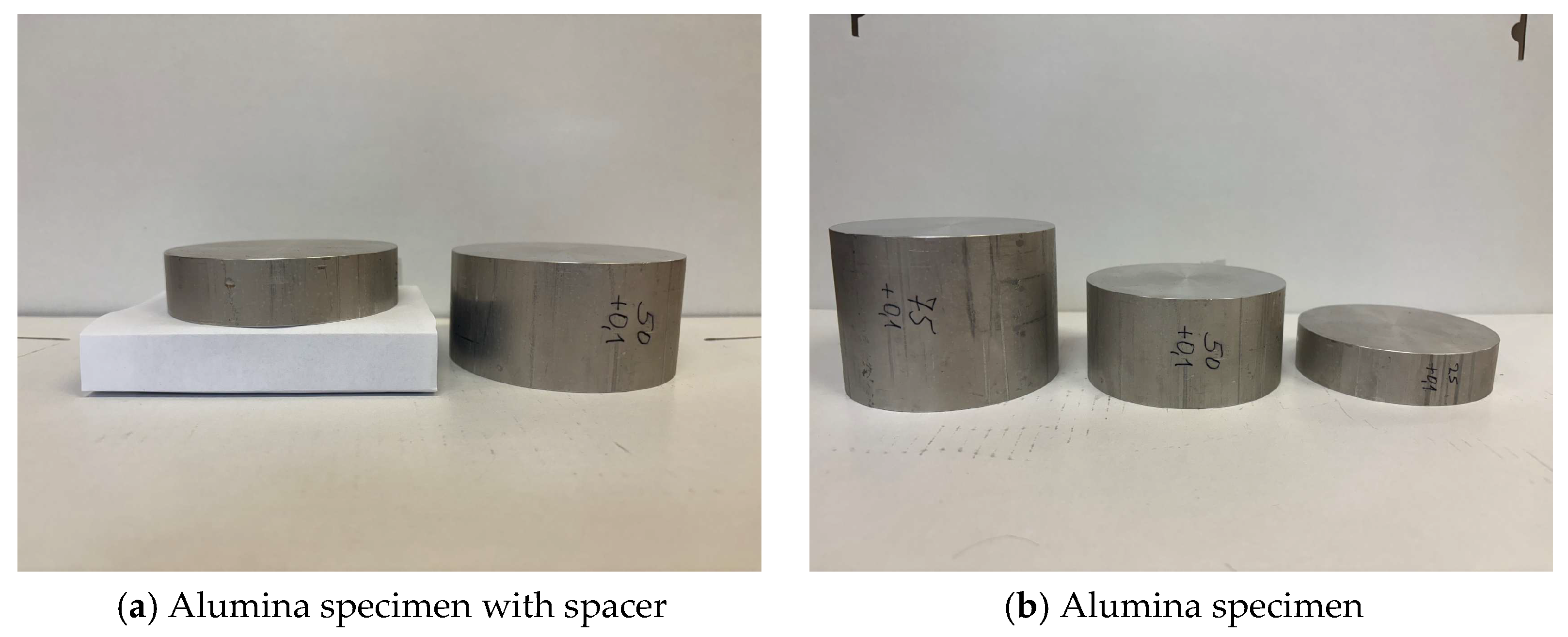

Originally, we wanted to use cylindrical alumina specimens with a diameter of 100 mm and a thickness of 25 mm in combination with bases with a thickness of 25 mm and 50 mm (

Figure 5a), but ultimately we used solid specimens with a thickness of 25 mm, 50 mm, and 75 mm (

Figure 5b). This was based on the consideration that the mass of the sphere and the distance to contact with the specimen (25 mm) would not deform the alumina surface, regardless of the thickness being 25 mm or more than 25 mm.

2.3.3. Setup of the STFR for Comparison with Model Data and Kinematic Analyses

Data generated by these measurements serve to assess the models presented in [

10]. Five measurements were made with 25 mm, 50 mm, and 75 mm initial height (±1 mm) on a foam board (=specimen) with 100 mm × 100 mm base area and 25 mm thickness. The travel of the sphere was recorded with a high-speed camera (see

Section 2.3.1).

2.3.4. Kinematic Analysis of the Travel of the Sphere

The arrangement of the camera was as described in

Section 2.3.1. The camera recorded for 2 s. Time–position data of the sphere are generated by Kinovea 0.9.5. software [

11]. The following arrangements were made:

The capture–frame-rate was set to 1000 fps (frames per second).

The sphere is placed on the specimen (height h = 0 mm), and the axis of view is horizontal. The center of the apparent outline of the sphere is marked.

The path of the mark is recorded by Kinovea.

The vertical positions ([px]) and time ([ms]) are exported in a .csv-file.

In order to allow comparison of mathematical models with data from the video image analysis, the latter were adapted using Microsoft Excel®:

Vertical positions were smoothed by a simple-moving-average (SMA) filter [

12].

For each measurement, the starting height hstart was calculated as the average of the first 100 data points, and the end height hend was calculated as the average of the last 100 data points.

For each measurement, a conversion factor from pixel [px] to [mm] is determined based on the preadjusted initial height h and an assumed indentation of 1 mm of the specimen when hit by the sphere. Five measurements were taken for each of the initial heights of 25 mm, 50 mm, and 75 mm, and mean values and standard errors were calculated from the individual conversion factors.

The software would identify a mark placed in the center of the object (see “+” mark in

Figure 6). Since this was not always correctly identified, we used the apparent outline as a mark for the sphere (yellow circle in

Figure 6). The apparent outline was marked when the sphere first came into contact with the specimen.

2.4. Variables Considered for Comparison of Model-Generated Data with STFR and Image Analysis

We checked the quality of the models by comparing results generated by the mathematical models elaborated in [

10] with measurements taken by the STFR and a computer-aided analysis of the frames of the video recording. Calculations were performed using Microsoft Excel

®. All measurements are replicated (

n = 5, unless stated otherwise). All measured values are reported as averages and standard errors. All calculated values are reported with the maximum error.

For comparison of models and STFR measurements, we used the following variables:

Time points recorded (T0, T1, d0, tP0);

Calculated initial height (h);

Depth of penetration (D = hmin);

Maximum rebound height (hmax);

Energy restitution (ER).

In addition, values for spring constant k and damping constant c were calculated. For these variables, no reference data can be derived from measurements and image analyses.

In order to identify measurements with the actual height h deviating from the prearranged setting, indicative for errors in height adjustment, we elaborated reference values for the time T0 from release of the sphere to first contact with the specimen.

2.5. MS-Access®-Based User Interface

This application was designed to processes data generated by the STFR and should allow import of *.csv data, arrangement of results according to date and initial height, setting of tolerance levels, entering specimen information, presenting average results from replicate tests, and, finally, exporting data in *.xls and *.pdf formats.