A Review: Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology

Abstract

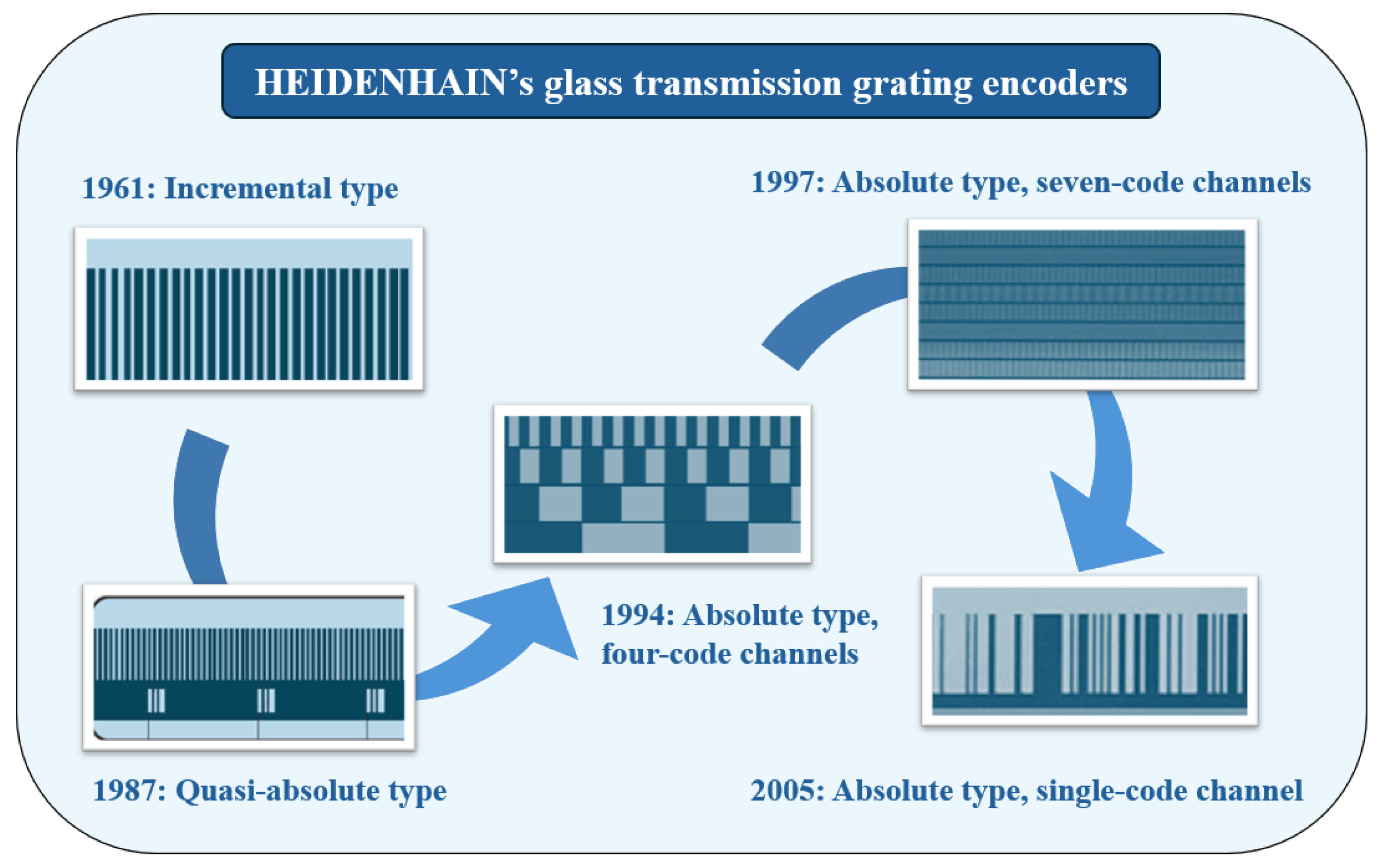

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Introduction, including the background and significance of the research, a review of domestic and foreign research, and an outline of the research content and thesis structure.

- (2)

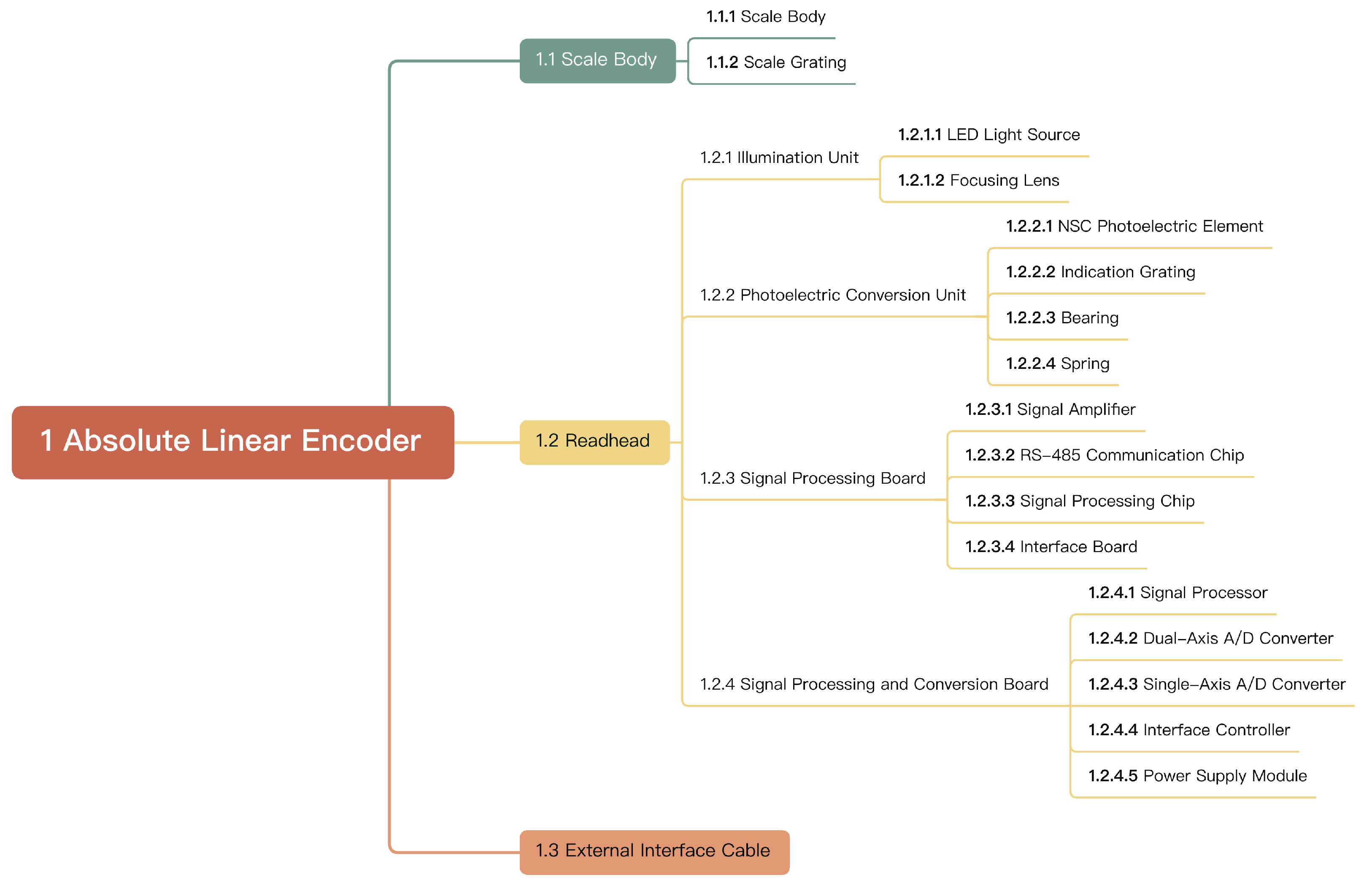

- Fundamental theories of absolute optical linear encoders, including measurement principles based on Moiré fringes, diffraction gratings, and image processing; coding and decoding technologies, including traditional absolute coding, serial communication protocols, and absolute decoding; and performance indicators, such as the measuring range, accuracy, pitch and resolution, motion speed, and stability. Meanwhile, a selection guideline for absolute linear encoders is presented.

- (3)

- Study of quasi-absolute coding methods, detailing non-embedded and embedded coding principles, structural characteristics, and application scenarios.

- (4)

- Systematic discussion of absolute coding techniques, including multi-track absolute coding (natural binary, Gray code, matrix code, vernier code, and combinations of absolute and incremental tracks) and single-track absolute coding (hybrid coding, displacement continuous coding, and pseudorandom sequence coding).

- (5)

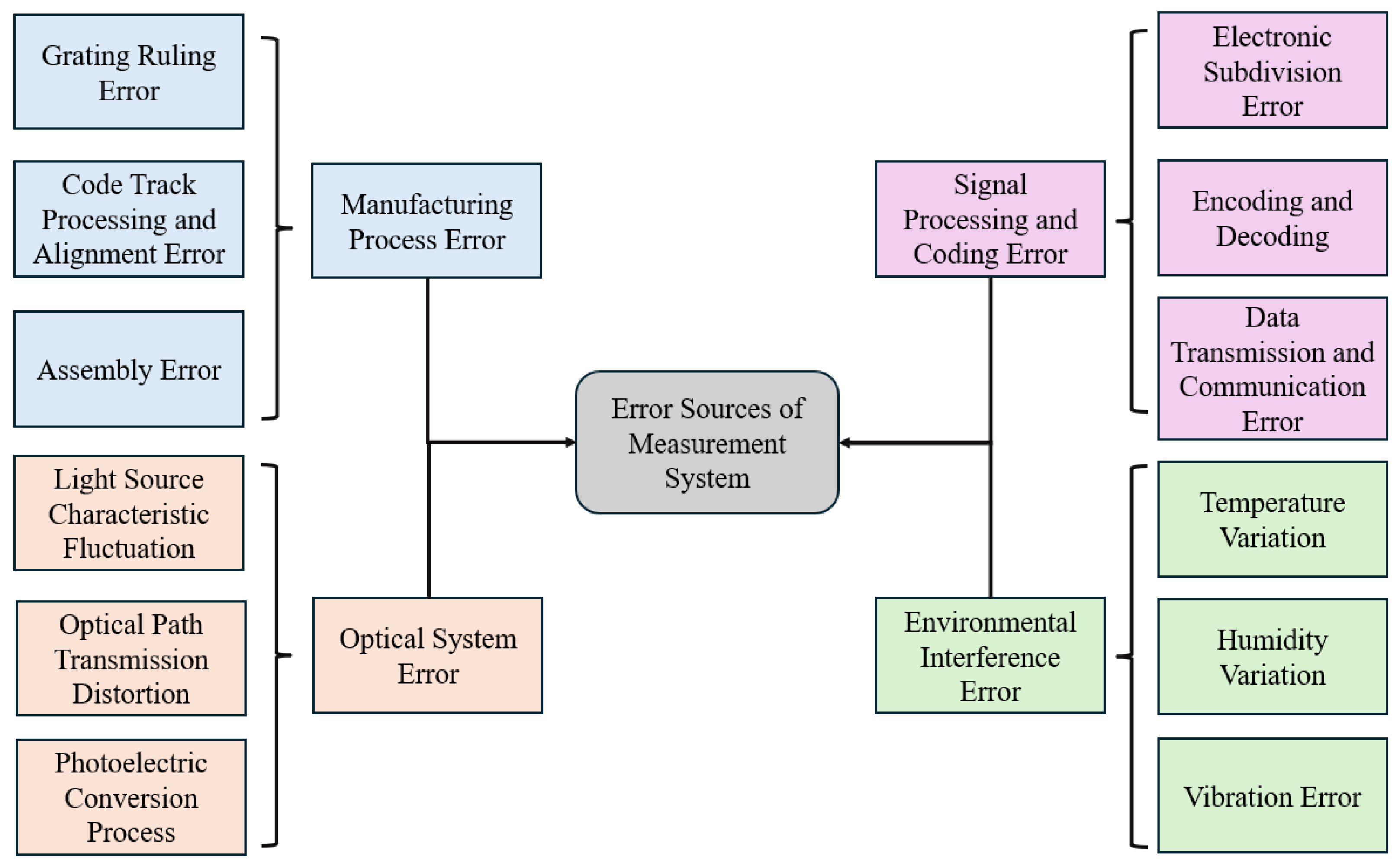

- Error analysis in absolute linear encoder measurement, including manufacturing process-related errors, optical system errors, signal processing and coding errors, and environmental interference, with discussions of causes and impacts.

- (6)

- Conclusions, summarizing the research, discussing current technological trends, and exploring potential future developments and breakthroughs for absolute optical linear encoders.

2. Fundamental Theory of Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement

2.1. Basic Principles of Linear Encoder Measurement

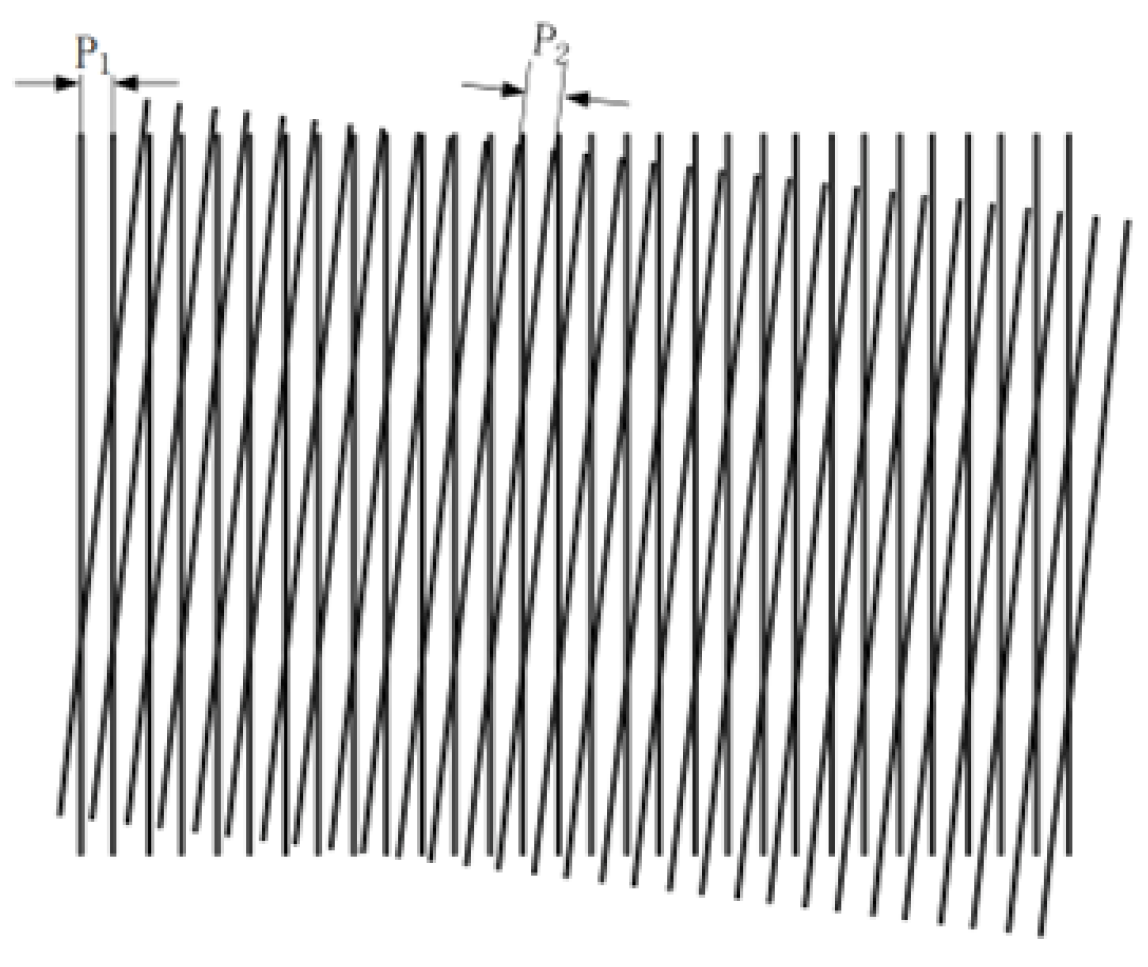

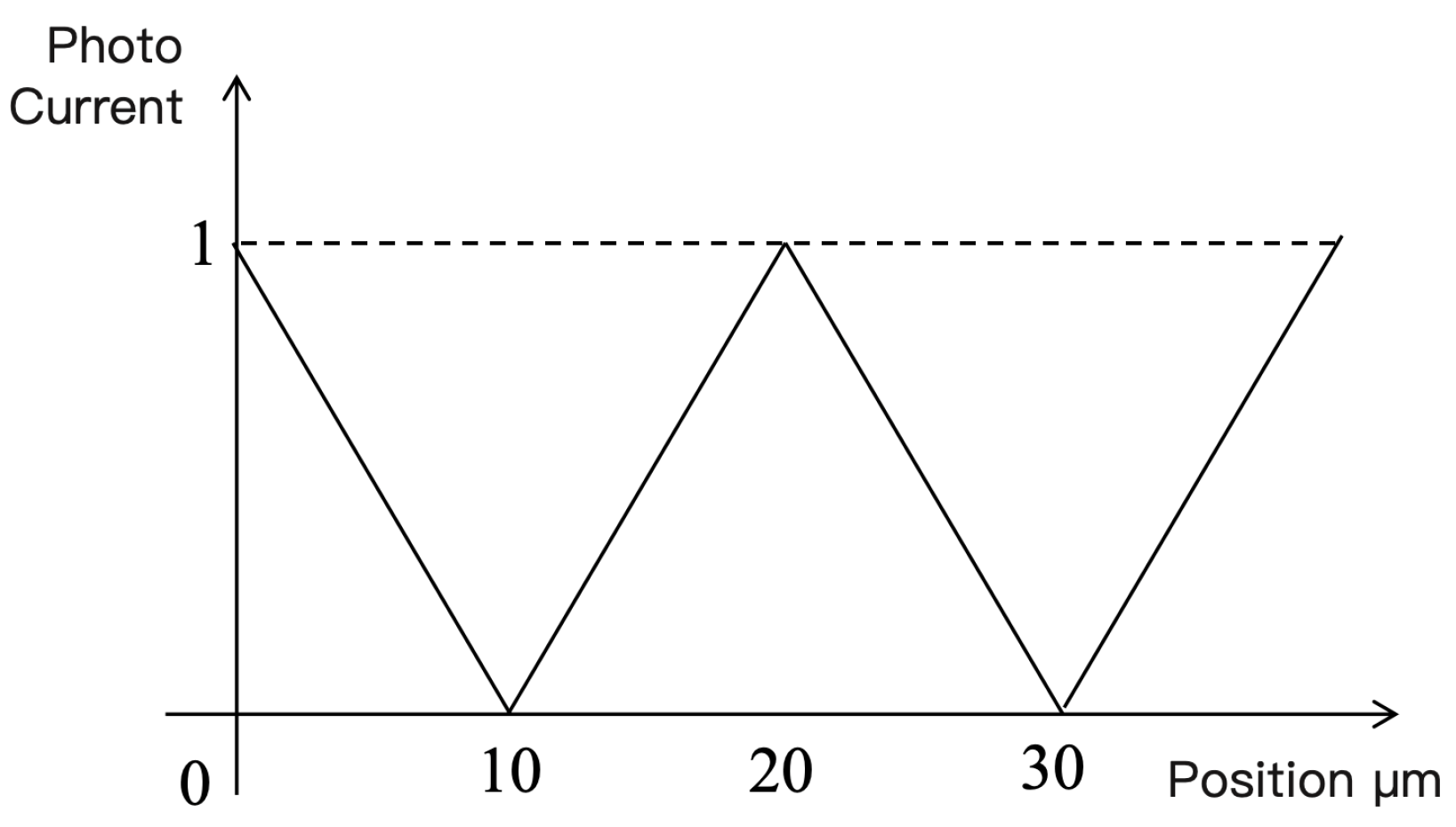

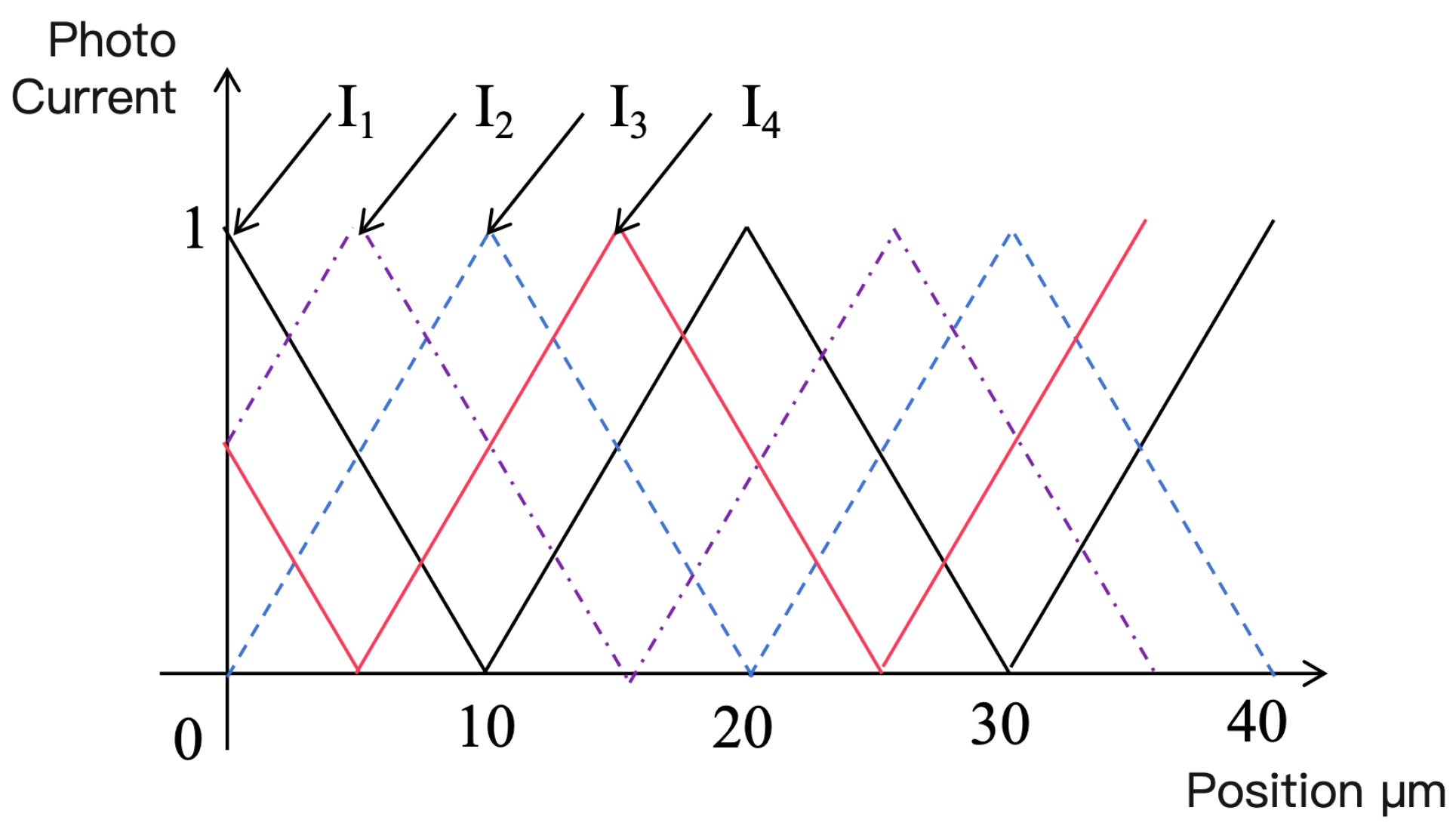

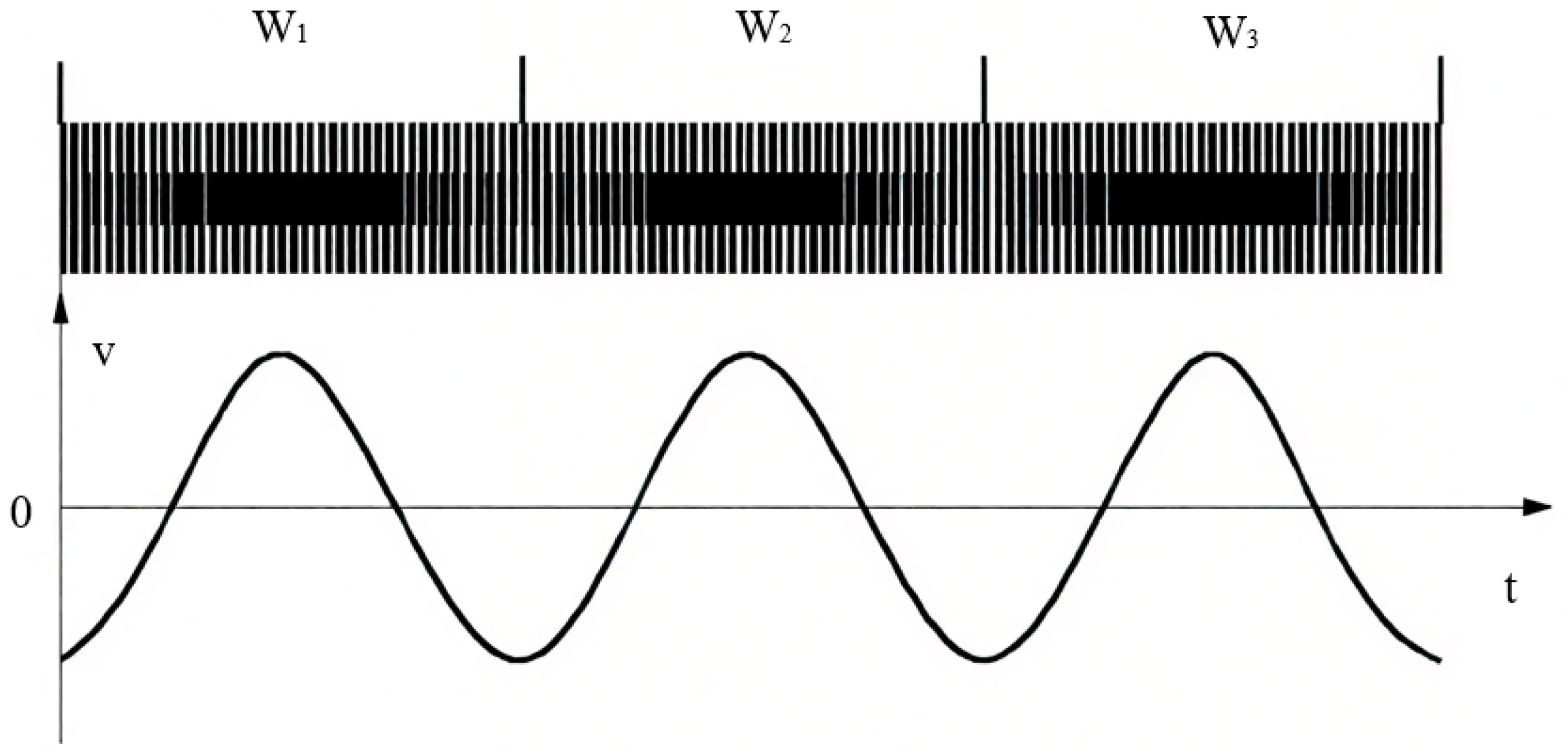

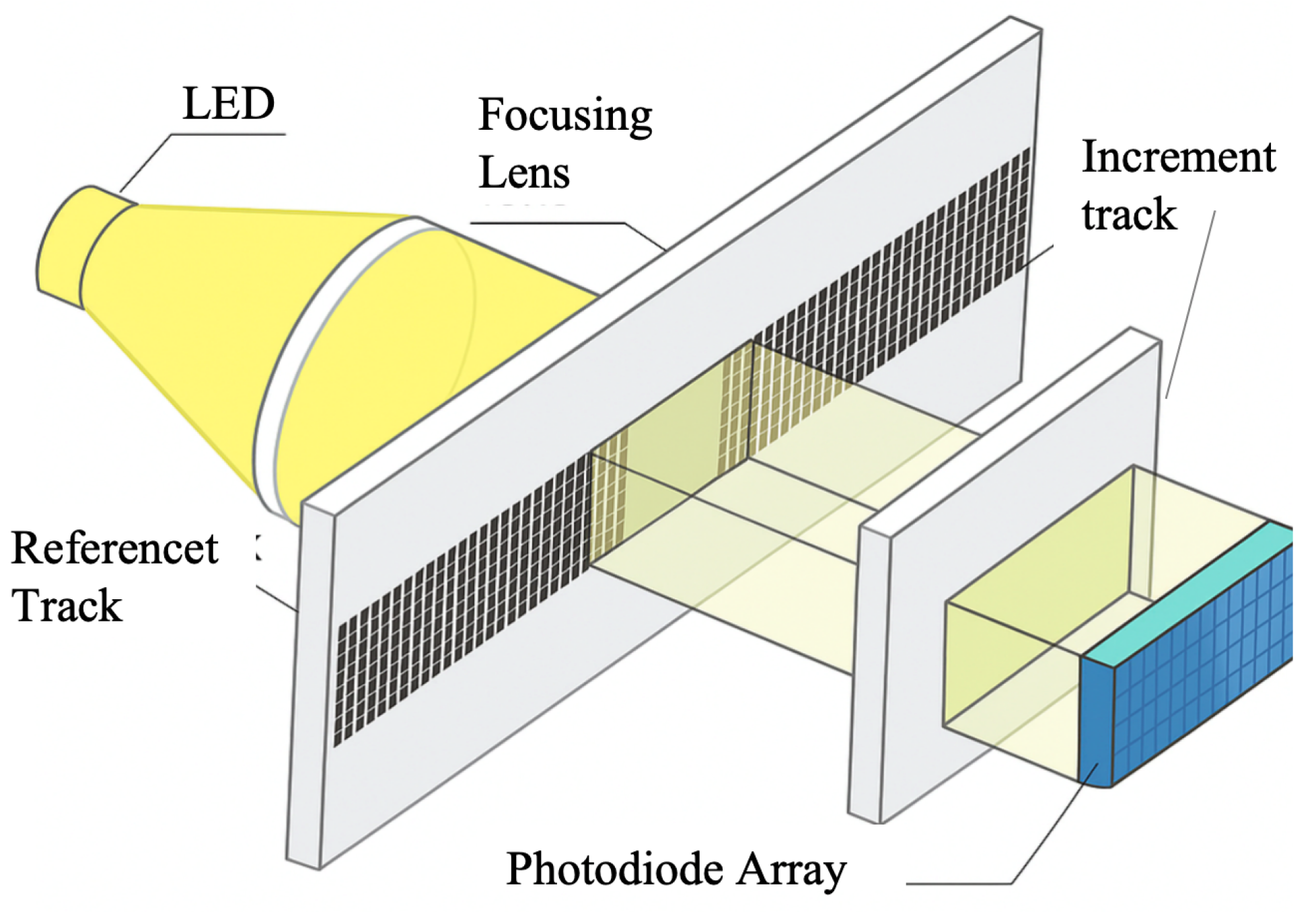

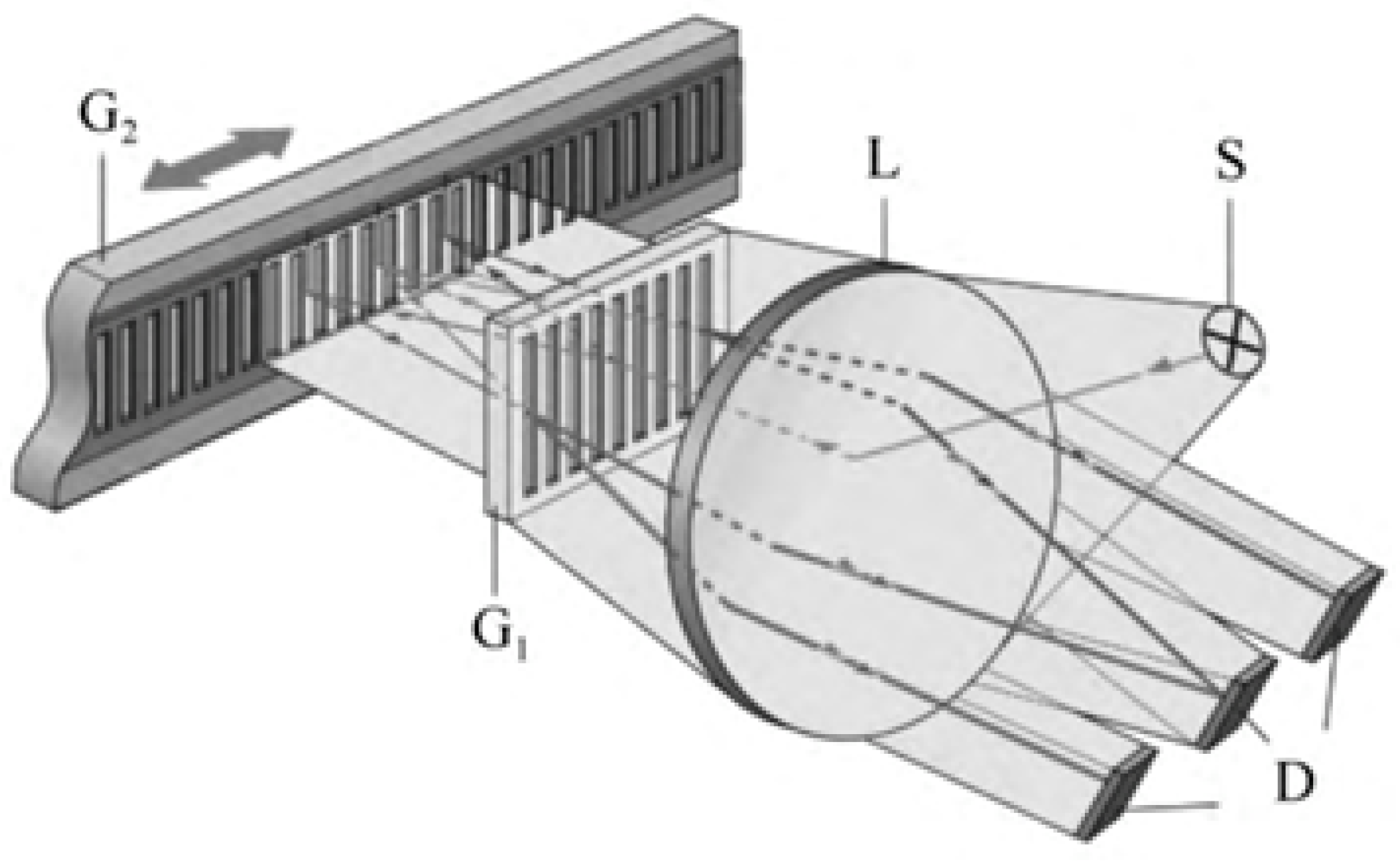

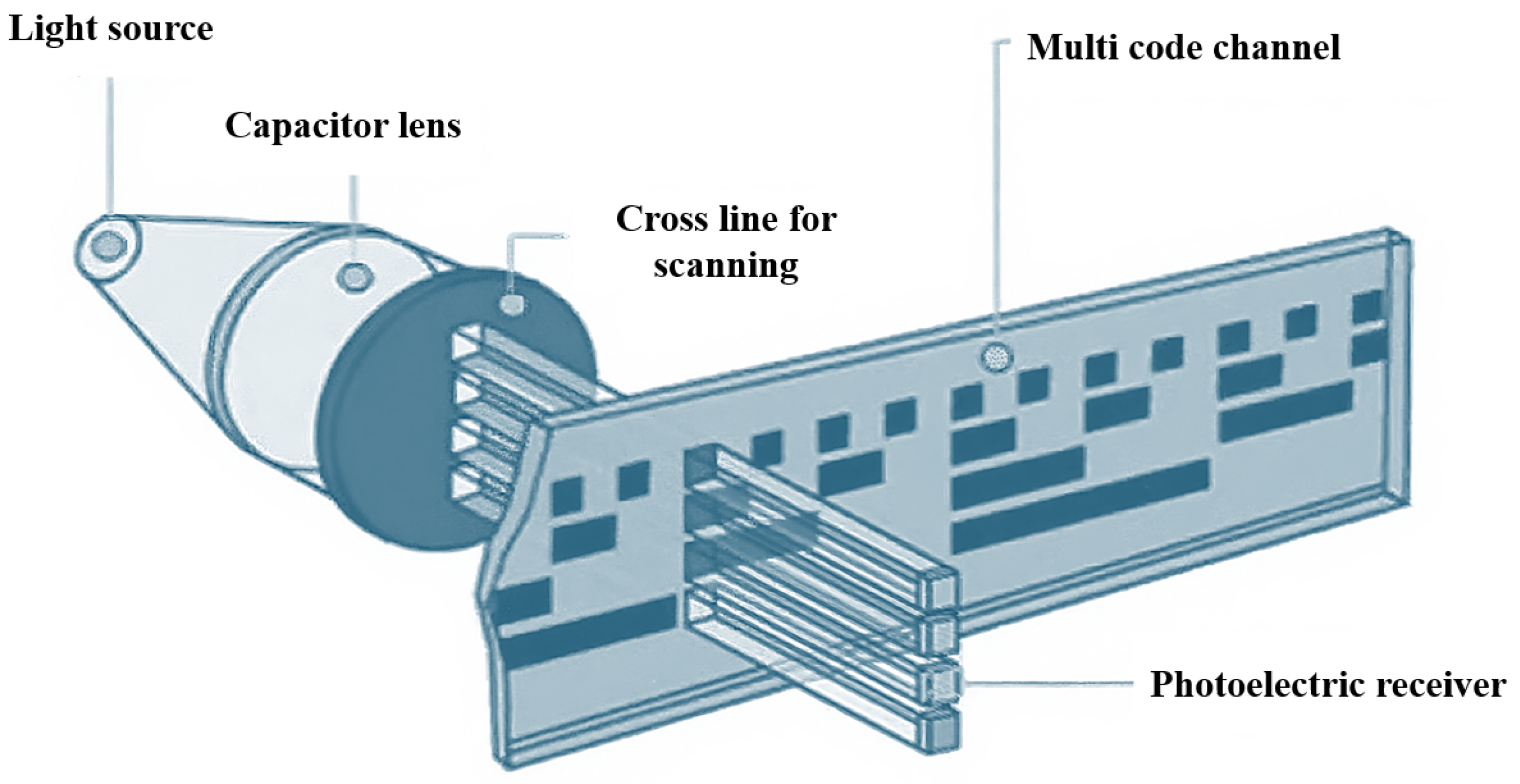

2.1.1. Principles of Linear Encoder Measurement Based on Moiré Fringes

- (1)

- When and , the fringes are called oblique Moiré fringes;

- (2)

- When , the Moiré fringes are approximately perpendicular to the grating lines, called transverse Moiré fringes;

- (3)

- When and , the fringes move parallel to the grating lines, called longitudinal Moiré fringes;

- (4)

- When and , the fringe width tends to infinity, called strobe Moiré fringes.

- (1)

- The magnification effect of Moiré fringes allows high-sensitivity displacement measurement;

- (2)

- Moiré fringes average out grating line errors, effectively suppressing local line errors and achieving higher accuracy compared to direct measurement methods;

- (3)

- Non-contact measurement is possible, improving system stability and service life.

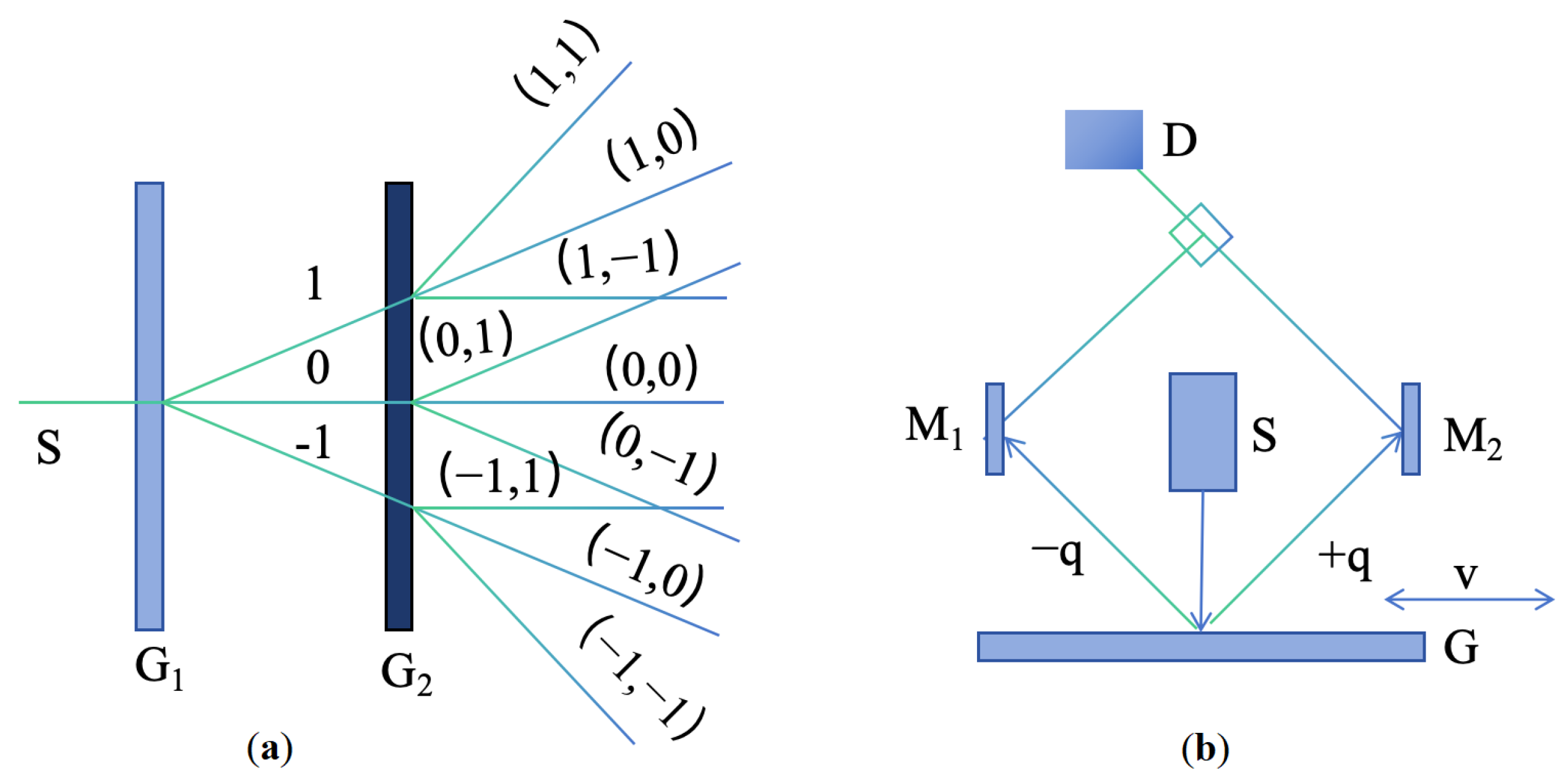

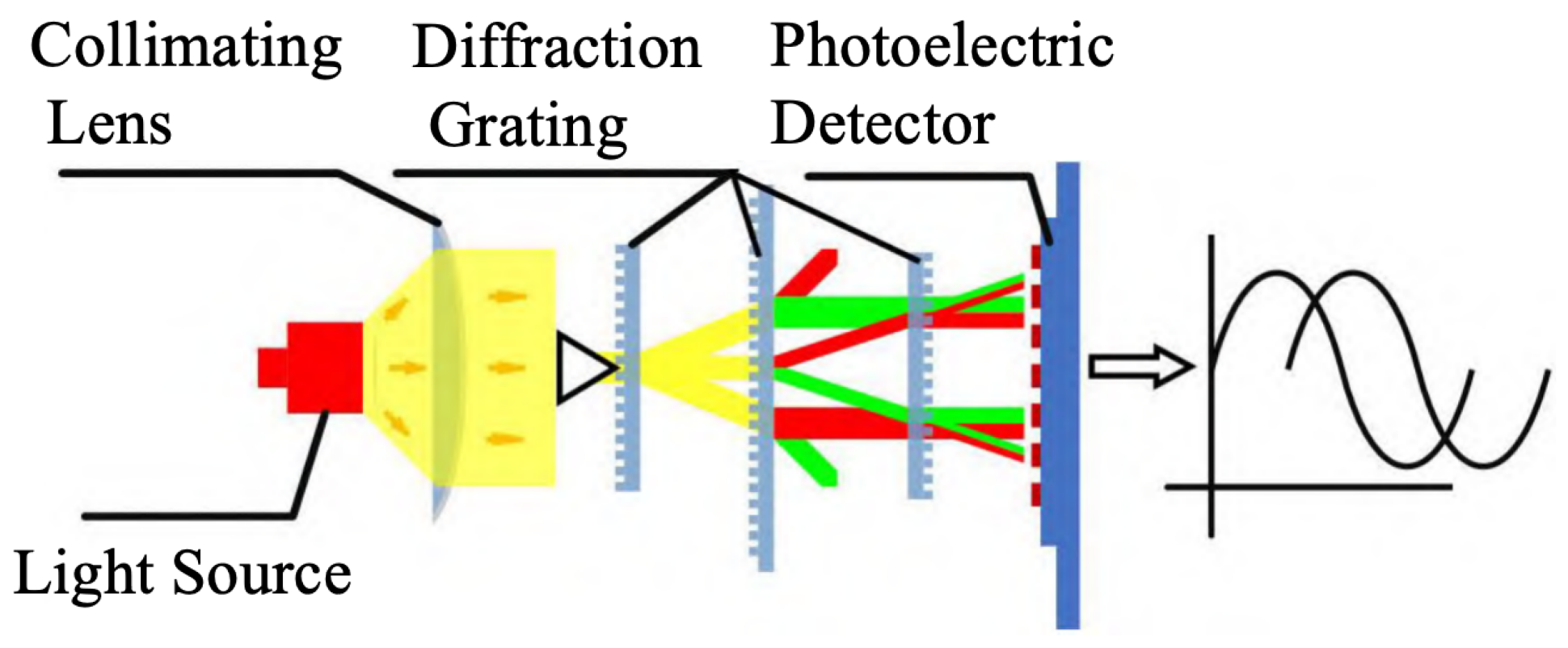

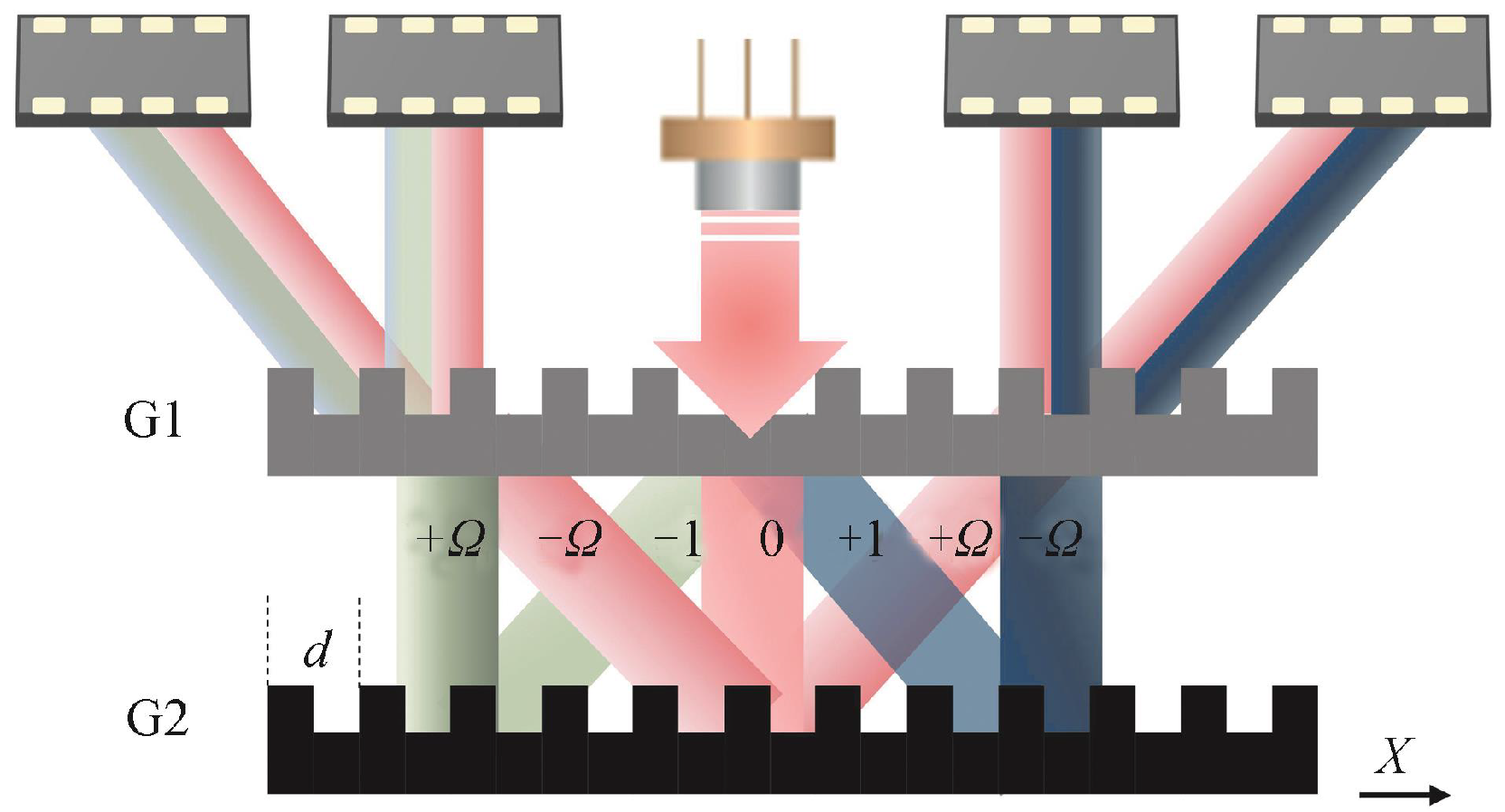

2.1.2. Principles of Linear Encoder Measurement Based on Diffraction Gratings

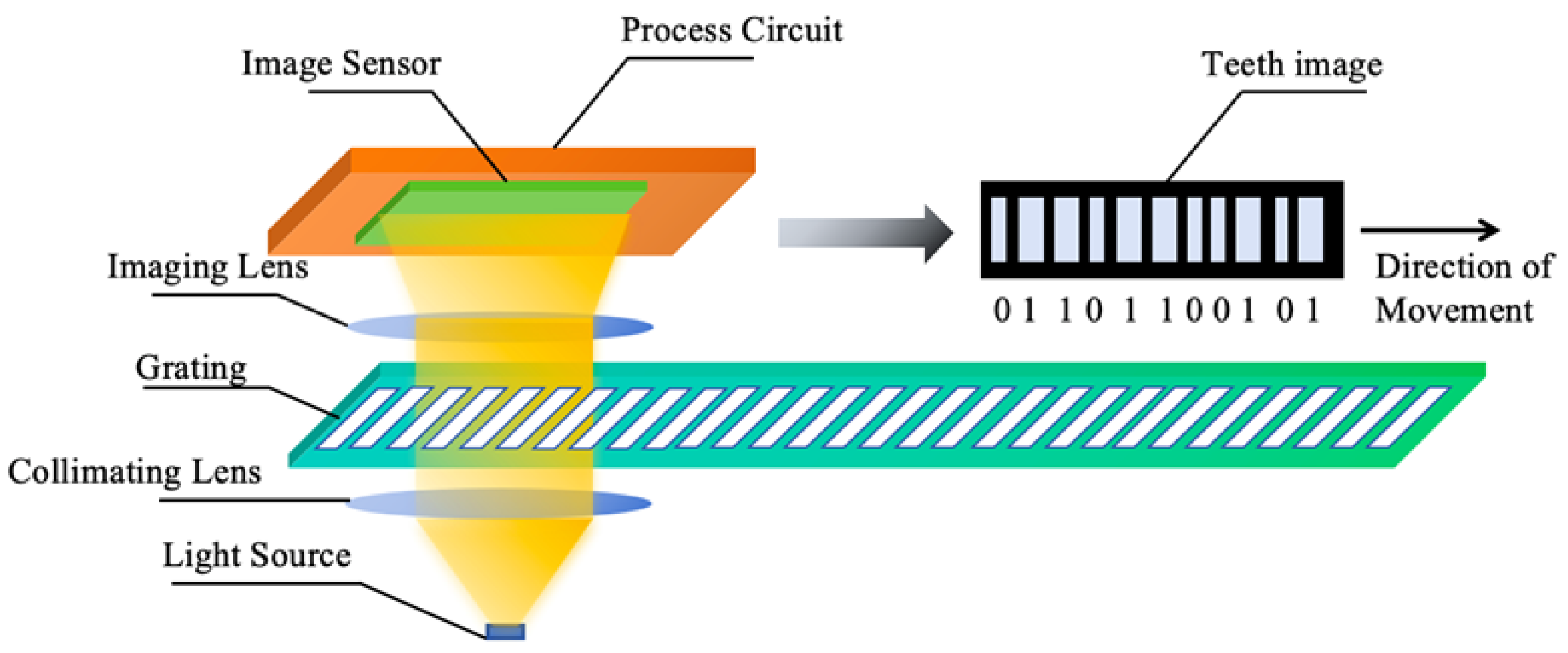

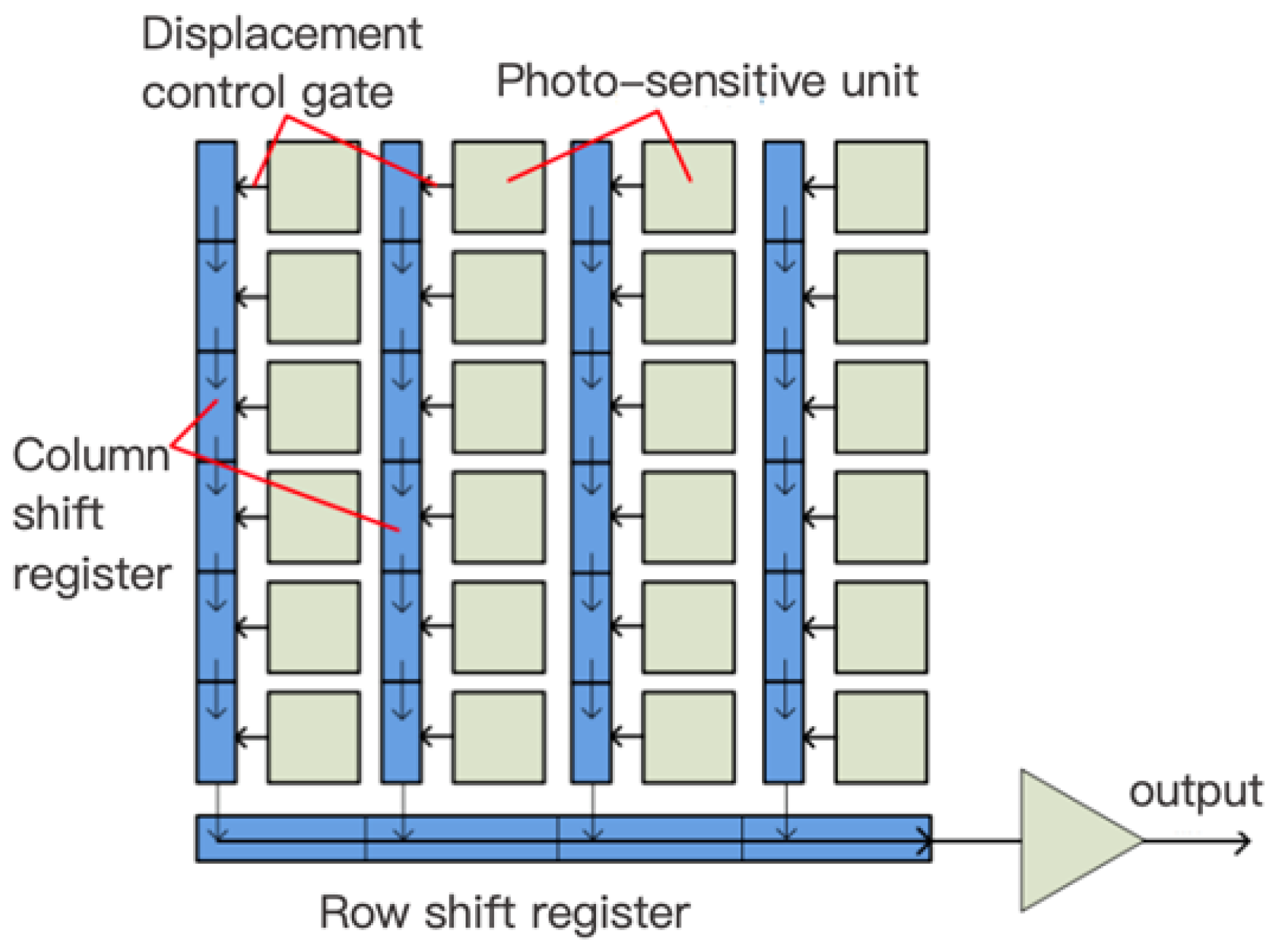

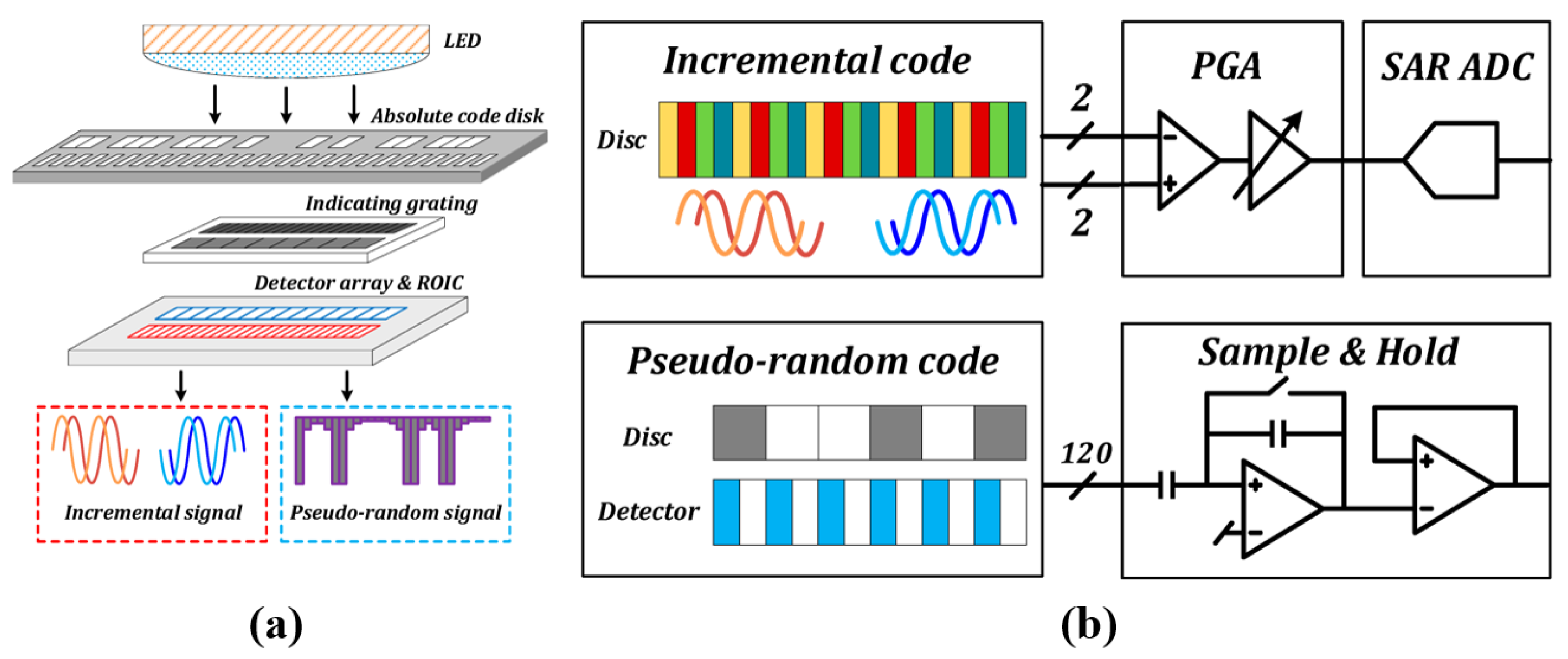

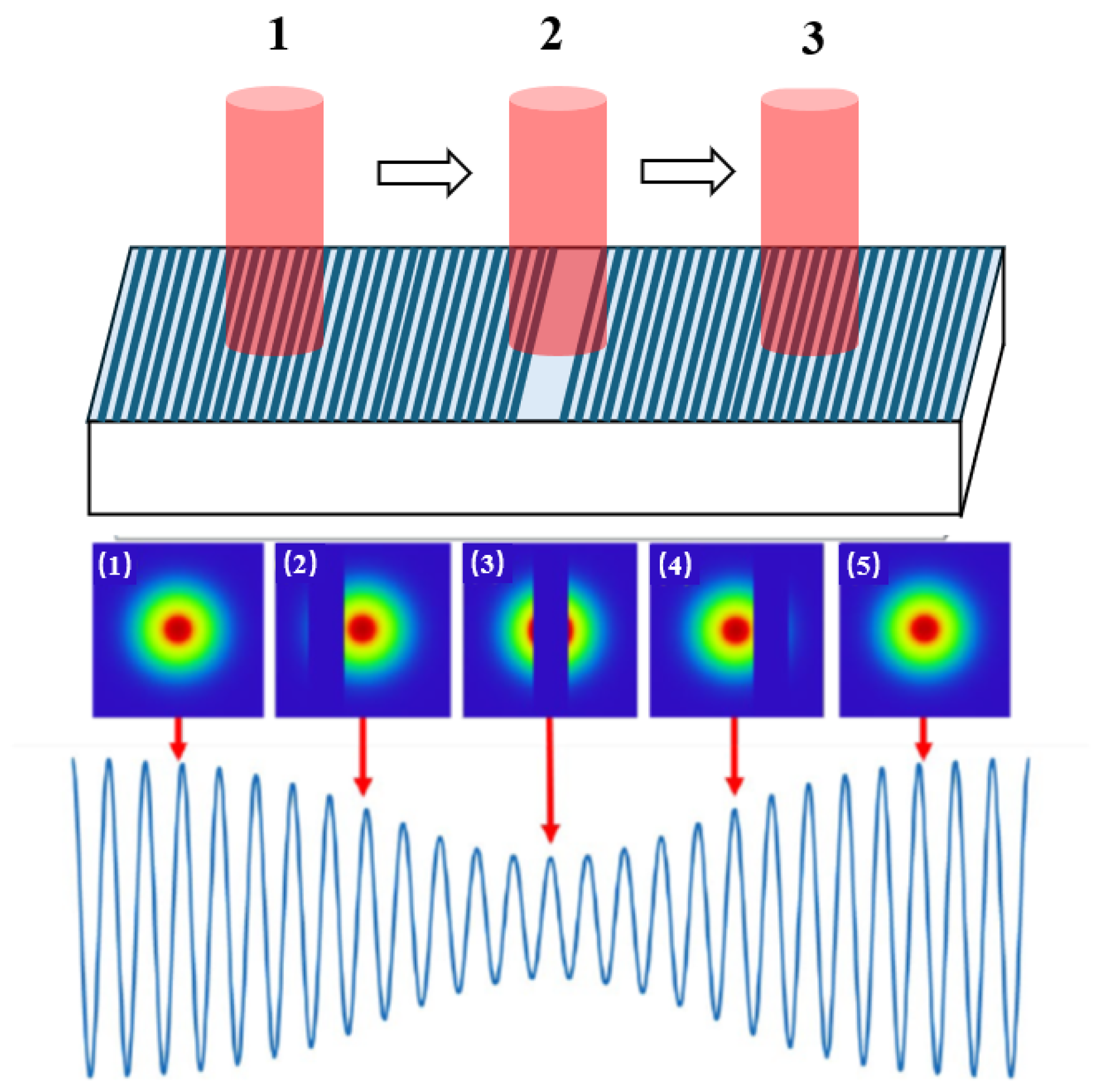

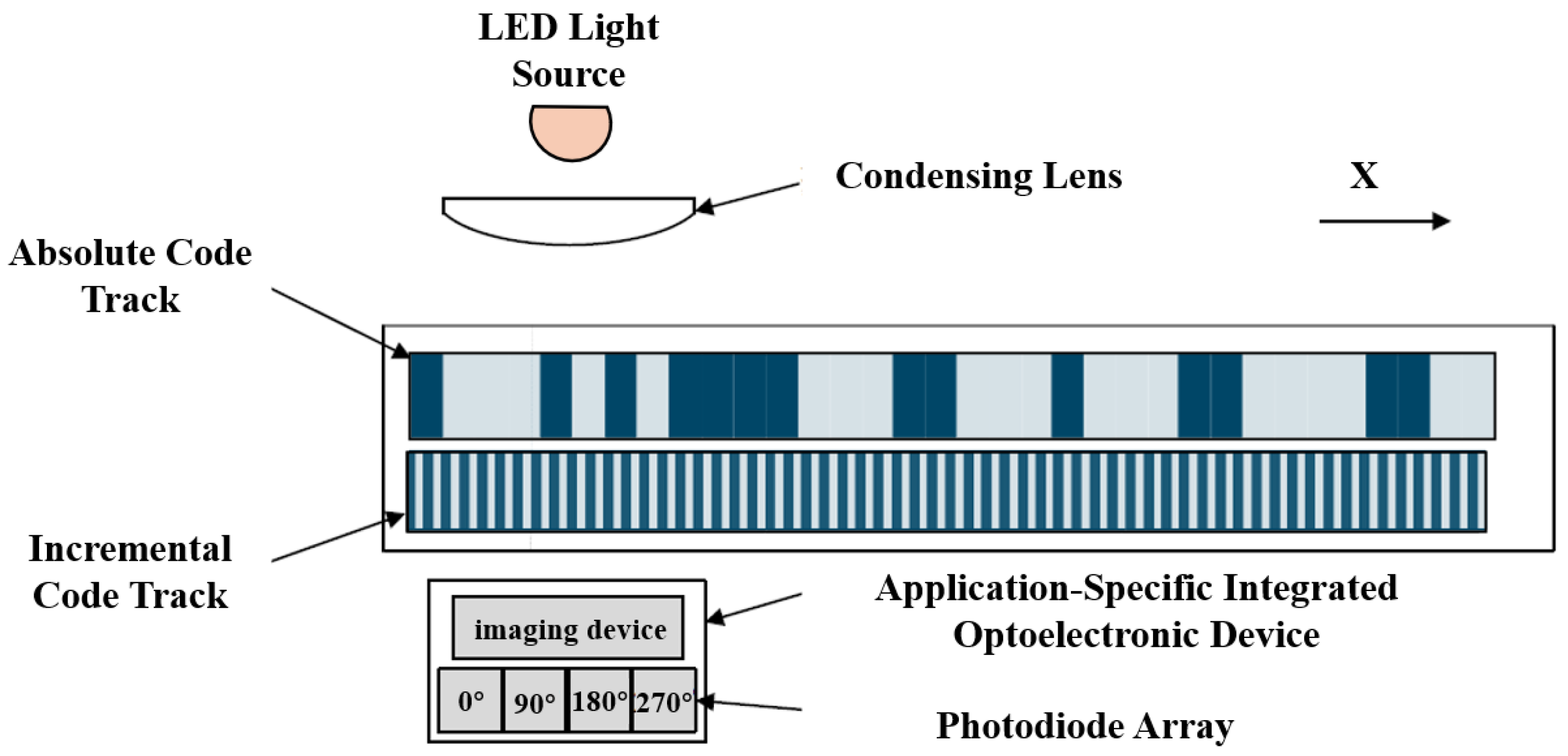

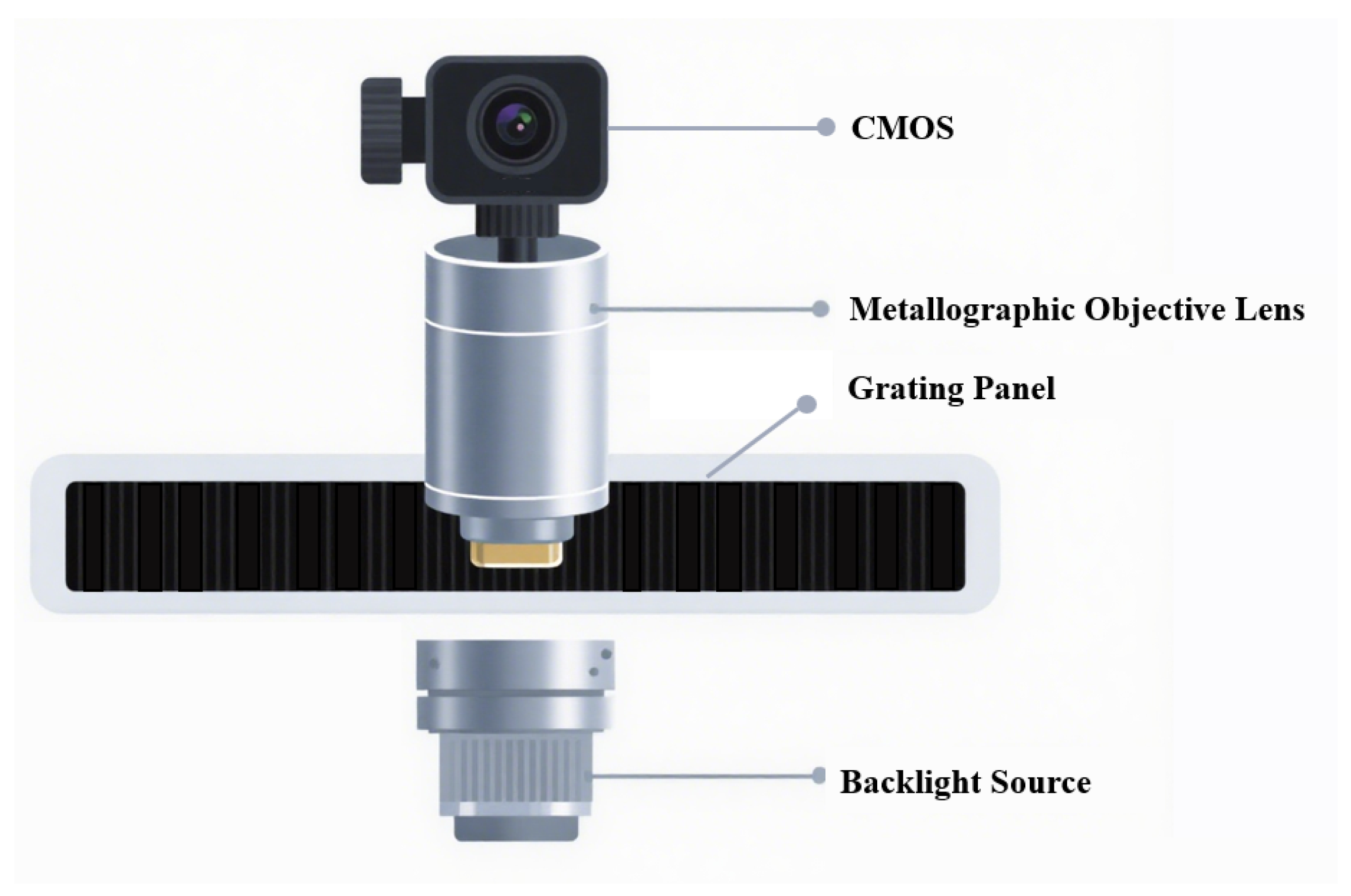

2.1.3. Principles of Linear Encoder Measurement Based on Image Processing

- (1)

- Strong robustness against illumination variations and noise;

- (2)

- High efficiency and real-time computation capabilities.

2.2. Encoding and Decoding of Linear Encoders

2.2.1. Traditional Absolute Encoding Methods

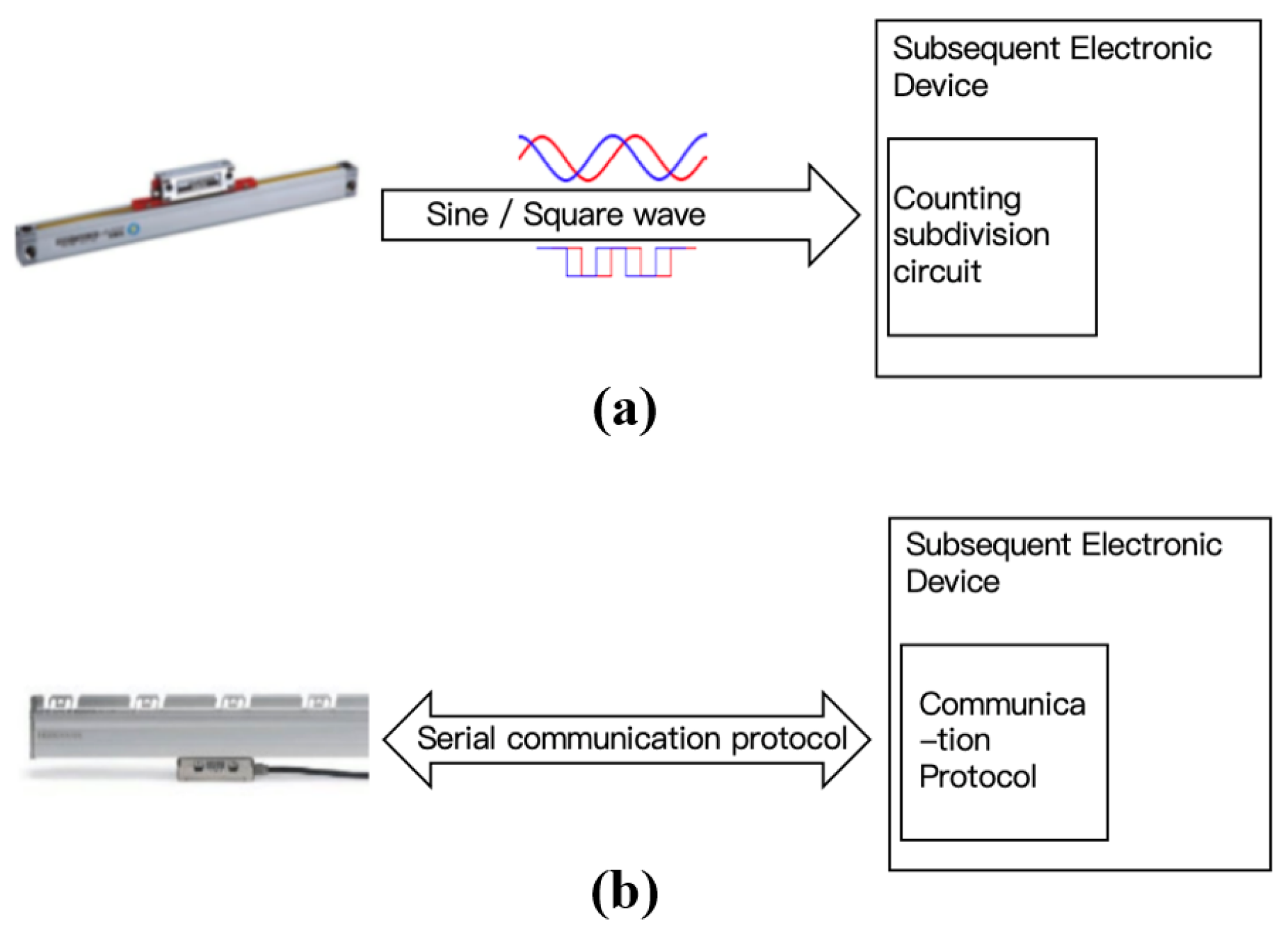

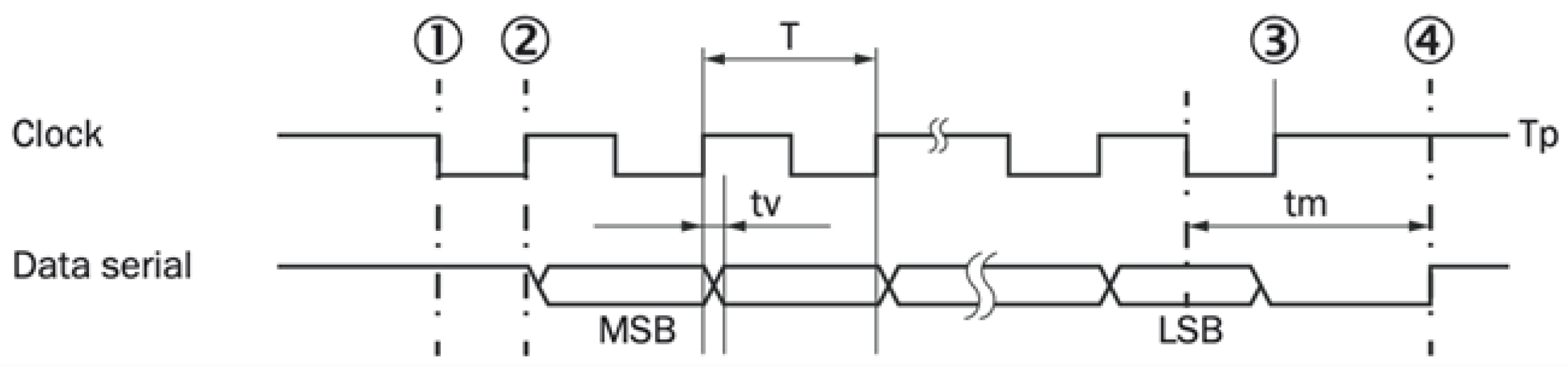

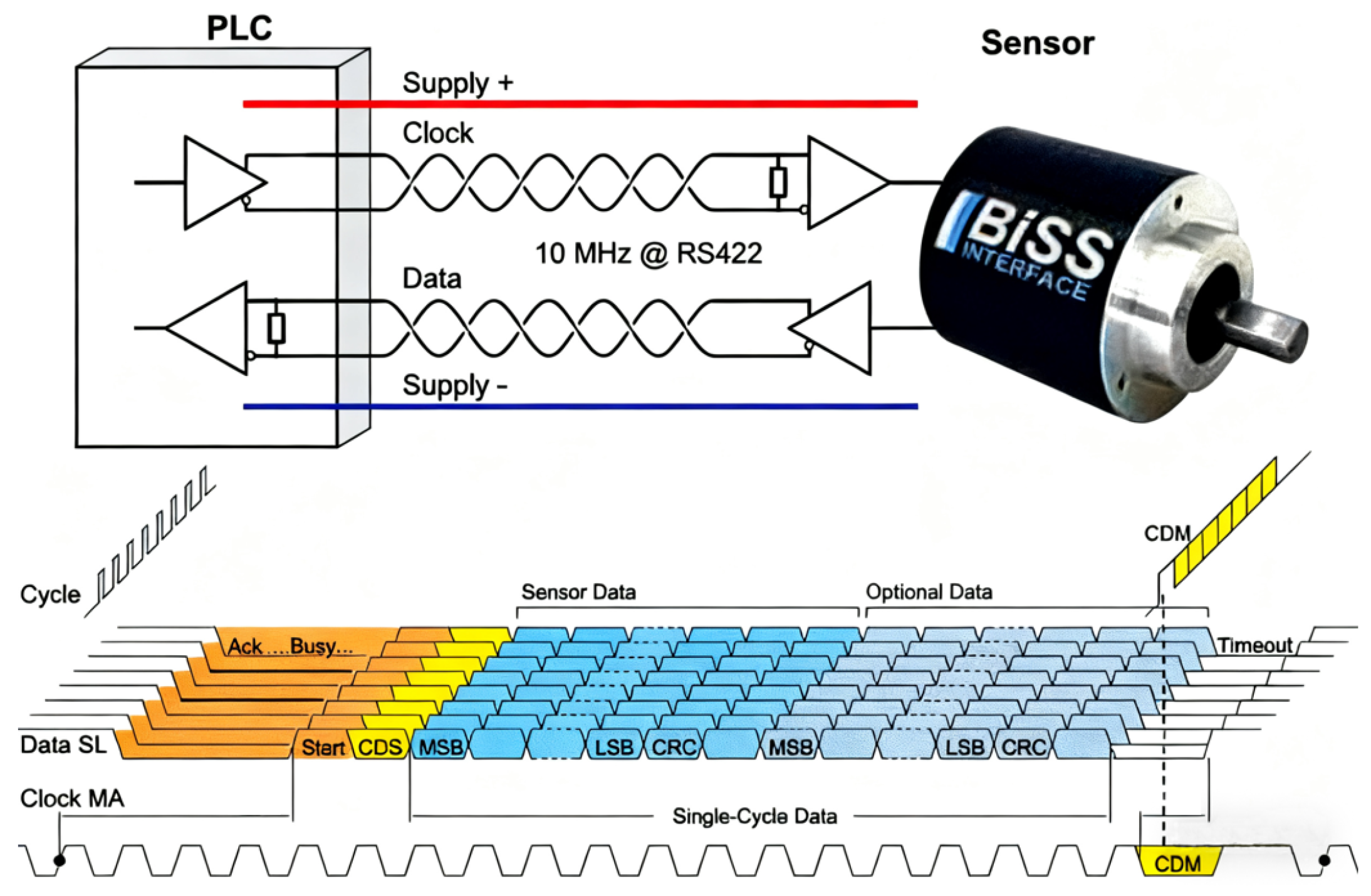

2.2.2. Serial Communication Protocols

2.2.3. Absolute Decoding

2.3. Performance Indicators of Absolute Measurement

2.3.1. Measuring Range and Stroke

2.3.2. Measurement Accuracy

2.3.3. Grating Pitch and Resolution

2.3.4. Motion Speed

2.4. Selection of Absolute Linear Encoders

- (1)

- Encoding Method: The choice between quasi-absolute linear encoders and absolute encoding schemes is application-dependent. Quasi-absolute linear encoders require a homing operation after power interruption to re-establish the absolute position. Despite this limitation, they can provide rapid relative position feedback during operation at a comparatively low cost, making them a practical and economical solution for general-purpose CNC lathes and other machine tools with moderate accuracy demands where homing is acceptable. For applications requiring high integration within limited space, embedded quasi-absolute linear encoders offer additional advantages. Absolute linear encoders, by contrast, provide continuous absolute position data without the need for homing, thereby improving the startup efficiency and enhancing the positioning accuracy. They are widely adopted in automated production lines and precision machining centers, where stringent requirements on productivity and accuracy prevail. Conventional multi-track encoding remains a mature solution, utilizing multiple parallel tracks to resolve absolute positions. This approach is well established in engineering practice and includes coding schemes such as natural binary, Gray code, vernier code, and hybrid absolute–incremental codes. Nevertheless, the need for multiple tracks and sensors increases the system complexity and cost while hindering miniaturization. In contrast, single-track encoding employs aperiodic code sequences—such as pseudorandom codes, continuous displacement codes, or hybrid formats—enabling compact designs with reduced structural complexity. However, challenges remain regarding sequence diversity, real-time decoding efficiency, and long-range stability, which require further technological advancement.

- (2)

- Core Performance Metrics: Measurement accuracy constitutes the principal criterion in encoder selection. Importantly, accuracy levels must be aligned with the actual precision requirements of the machine tool, as the indiscriminate pursuit of ultra-high accuracy often leads to disproportionate cost escalation [1]. For example, equipping a standard CNC machine with an ultra-high-precision encoder not only increases the procurement costs but also demands specialized installation, calibration, and maintenance resources, thereby raising the overall lifecycle costs. Rational selection should thus correspond to the machine’s designated machining accuracy class: for machines with general machining tolerances of ±0.01 mm, encoders offering accuracies of ±(0.001–0.005) mm are typically sufficient. Encoder speed performance is equally critical, as it determines the capacity to provide timely and reliable feedback on axis movement. High-speed machine tools require encoders with a rapid response and high data transmission rates to ensure accuracy under dynamic operating conditions. Furthermore, long-term stability is essential to sustaining measurement accuracy, being largely dependent on the manufacturing precision, material quality, and resistance to external disturbances. Encoders constructed with high-grade materials and refined manufacturing processes exhibit superior resilience against thermal fluctuations, mechanical vibrations, and electromagnetic interference. In demanding industrial environments characterized by significant temperature variations or strong vibration, encoders with enhanced anti-interference design and proven stability should be prioritized to guarantee reliable long-term operation.

- (3)

- Structural Materials: Encoder scale materials and structural designs also play a decisive role in performance. Glass scales offer superior precision and are commonly employed in ultra-precision applications such as optical lens grinding machines. However, they are inherently brittle, typically limited to lengths below 4 m [63], and relatively costly. Their advantages lie in surface flatness and a low coefficient of thermal expansion, which facilitate accurate alignment during installation. By contrast, steel-tape encoders provide greater flexibility and can be manufactured in extended lengths of up to 4 m or more [63], making them more suitable for large-travel machine tools such as gantry machining centers, albeit at the expense of reduced accuracy. Regarding structural design, enclosed encoders integrate the scale within a protective housing, ensuring superior resistance to dust, coolant, and machining debris. In machine tools with sufficient installation space—such as floor-type boring–milling machines—enclosed glass encoders are preferred, as they safeguard the measurement accuracy and prolong the service life. In compact machine tools, however, where installation space is constrained, miniaturized glass or steel-tape encoders provide a more practical solution, enabling flexible integration without interfering with the arrangement of other components, while still ensuring adequate measurement performance.

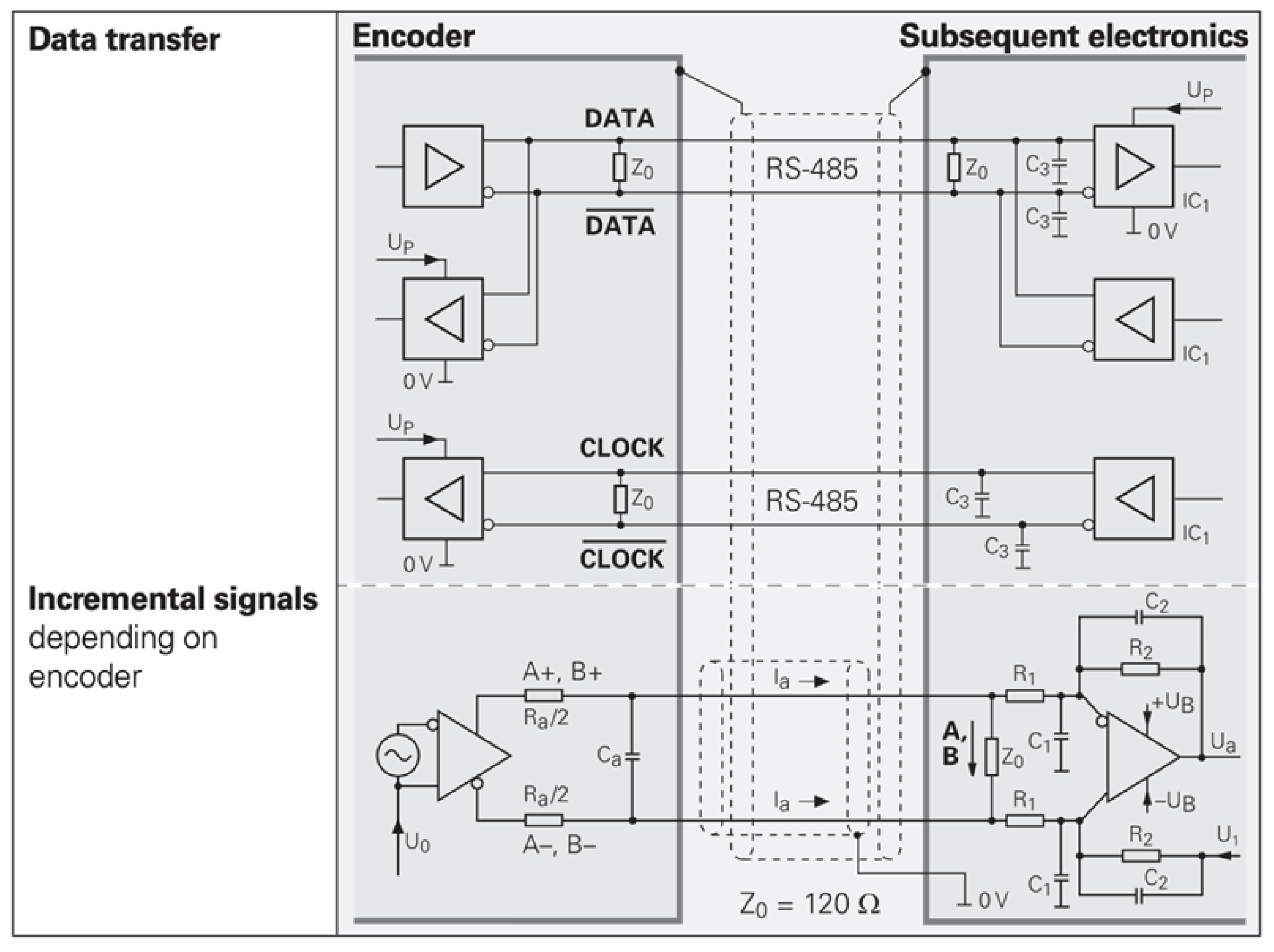

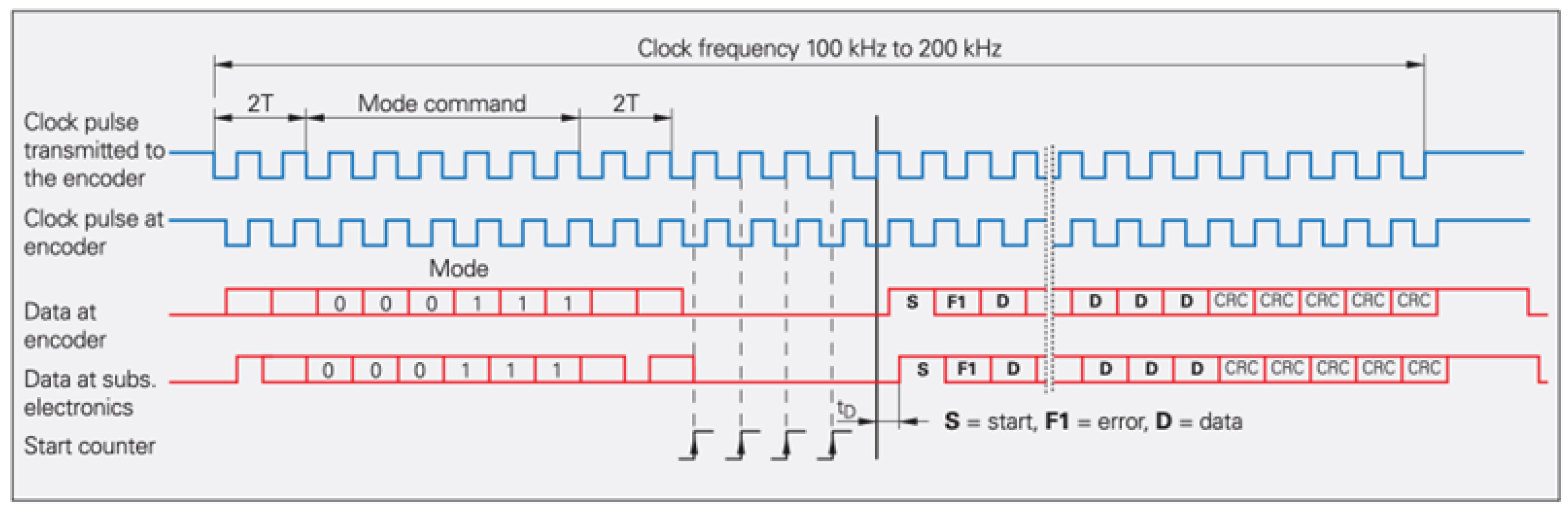

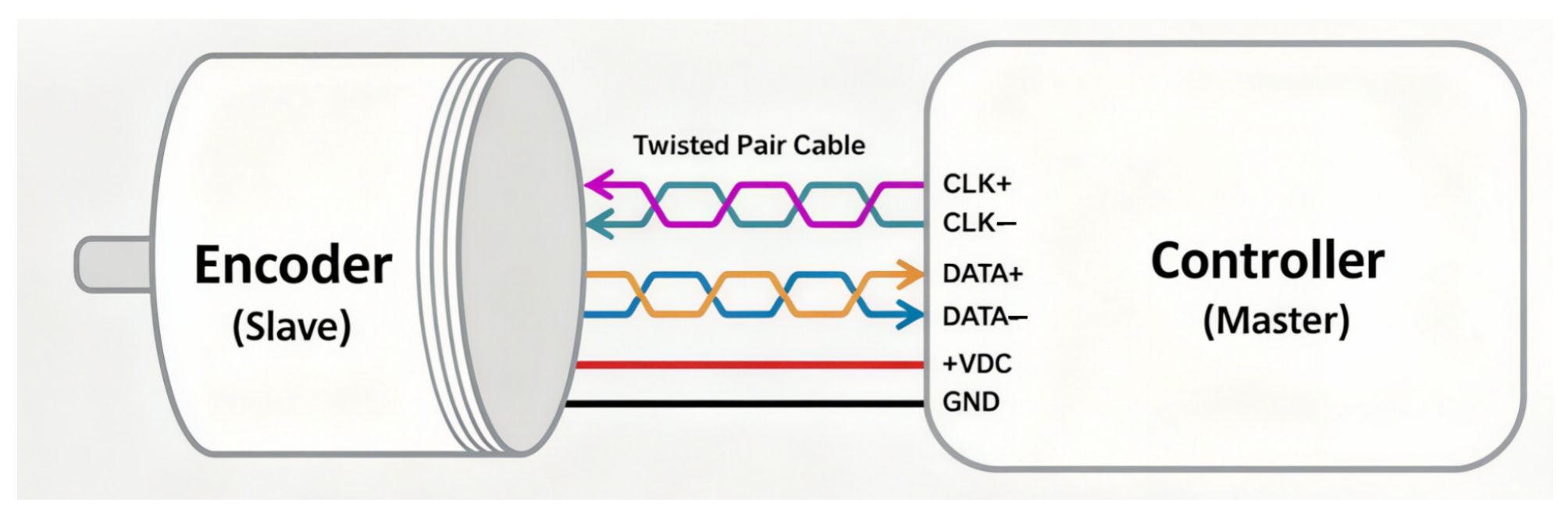

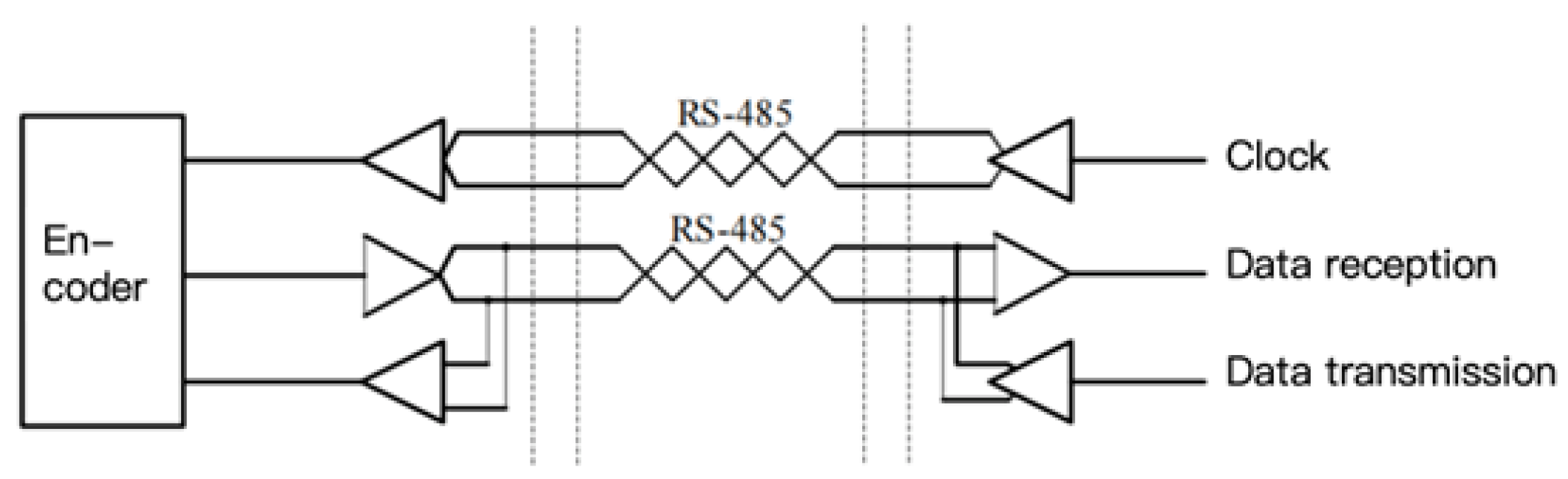

- (4)

- Communication Protocols: Absolute linear encoders typically transmit position data via serial communication interfaces, with different manufacturers adopting distinct protocol standards. Therefore, protocol compatibility with the numerical control (NC) system is a decisive factor in encoder selection. For instance, HEIDENHAIN encoders frequently employ the EnDat 2.2 protocol, which is noted for its high transmission speed, strong anti-interference capabilities, and seamless integration with HEIDENHAIN NC systems. This makes them particularly suitable for high-precision applications. Encoders from FAGOR commonly utilize the SSI protocol, valued for its universality and robustness and widely compatible with Siemens and other mainstream NC platforms, thereby providing users with versatile integration options. Meanwhile, Renishaw encoders, as well as those developed by the Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics, and Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, often adopt the BiSS protocol, which offers high-speed and high-accuracy data transmission. This makes it particularly advantageous in aerospace machining and other fields requiring stringent positional accuracy and real-time feedback.

3. Quasi-Absolute Linear Encoder

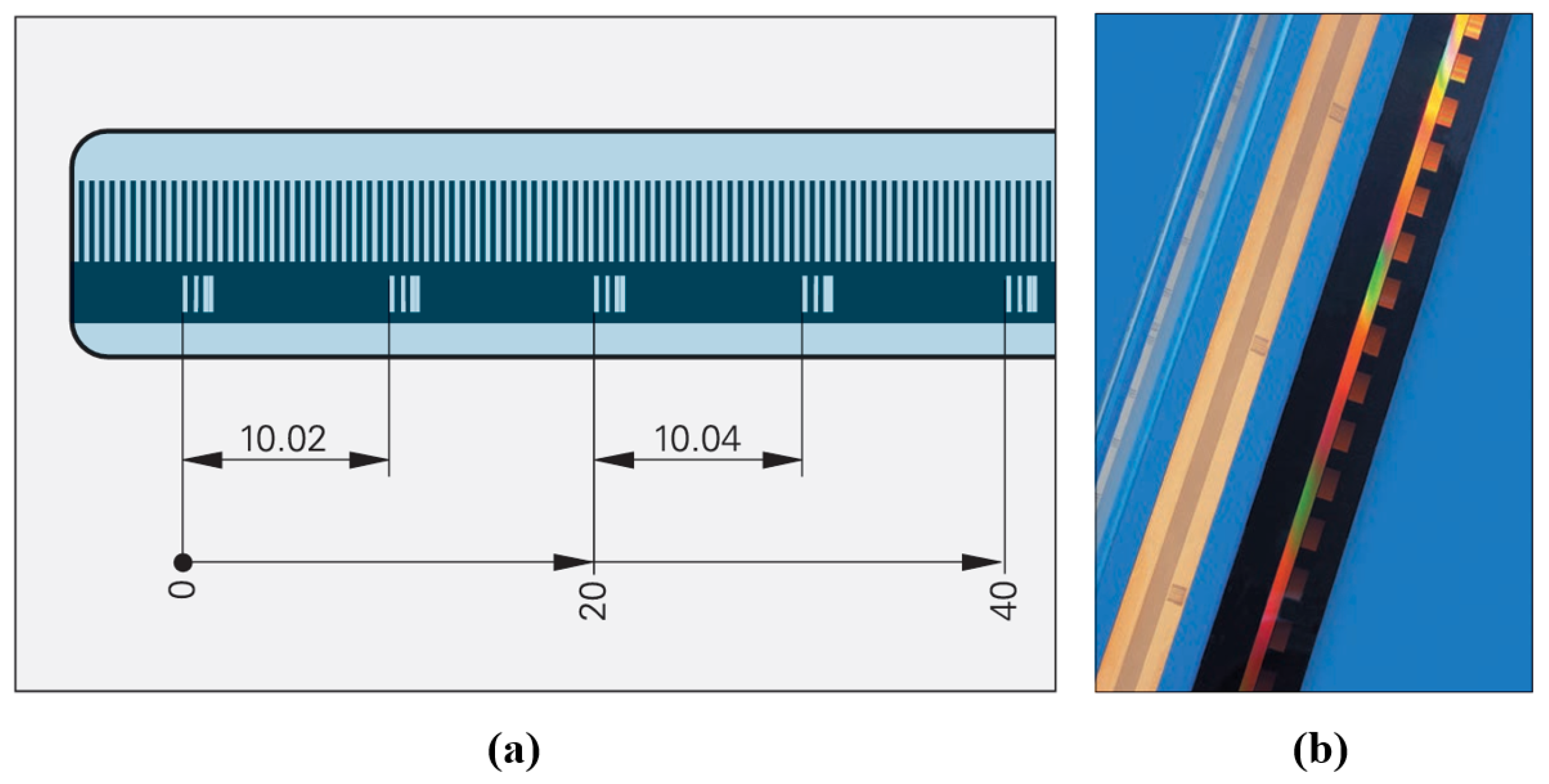

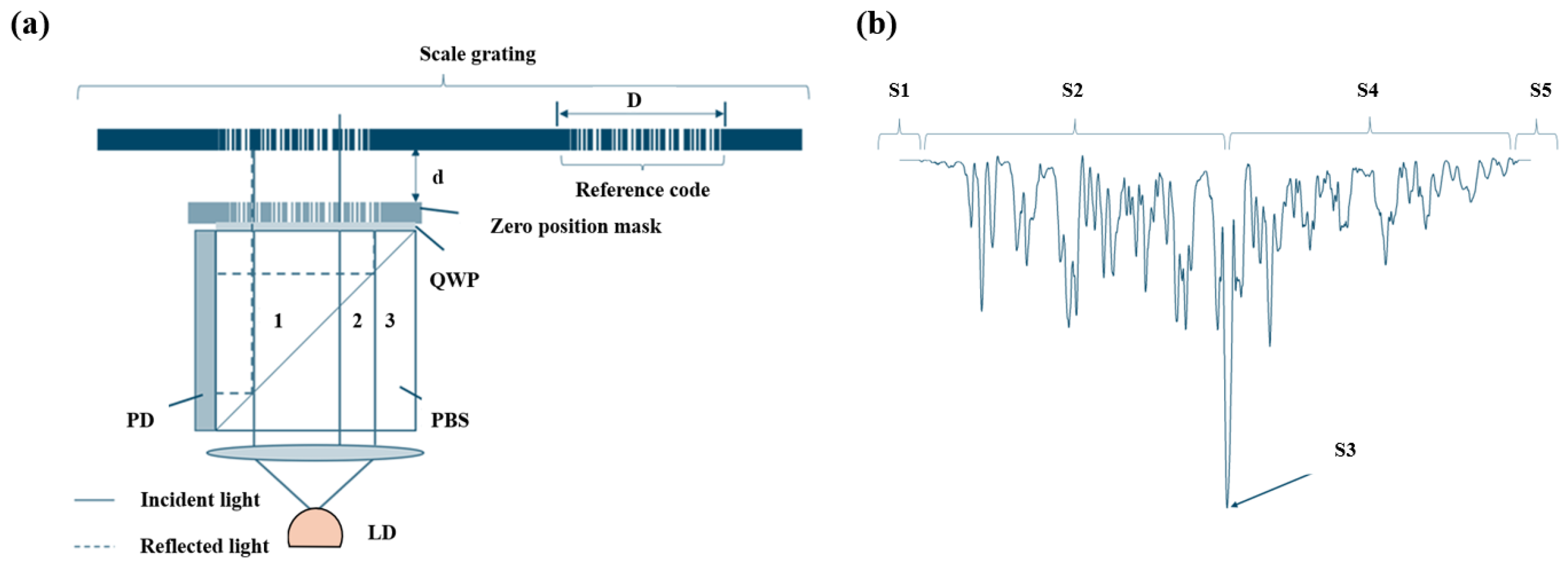

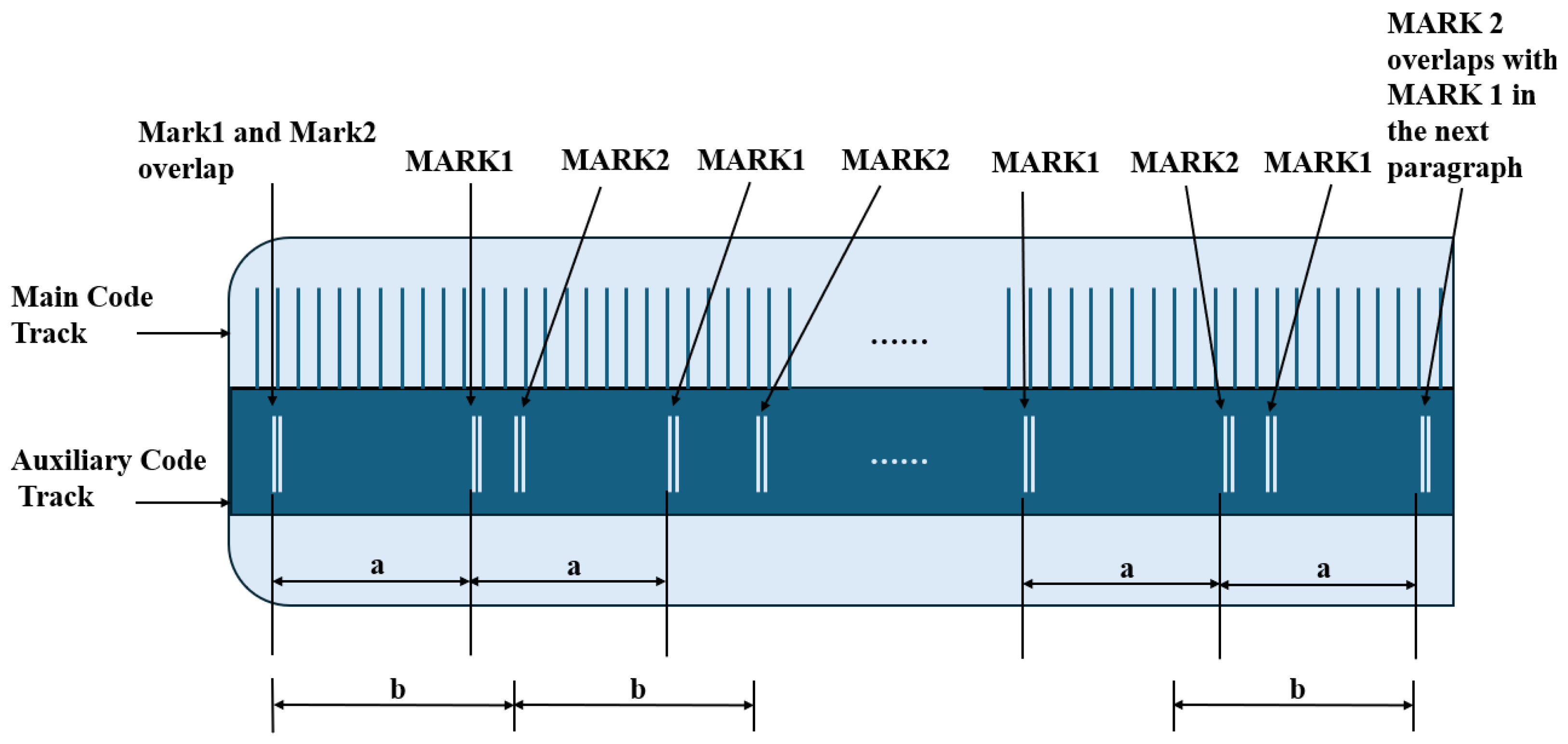

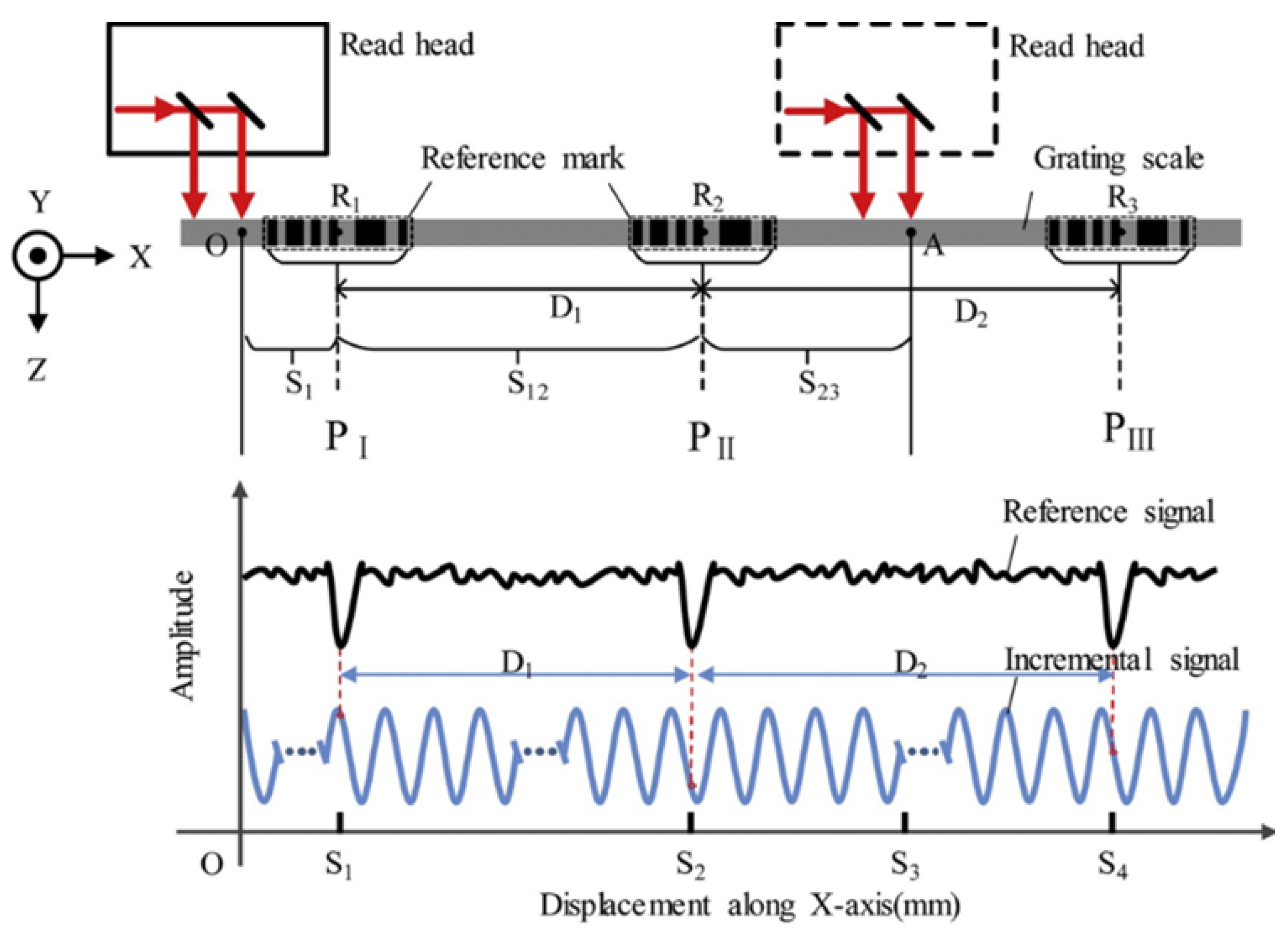

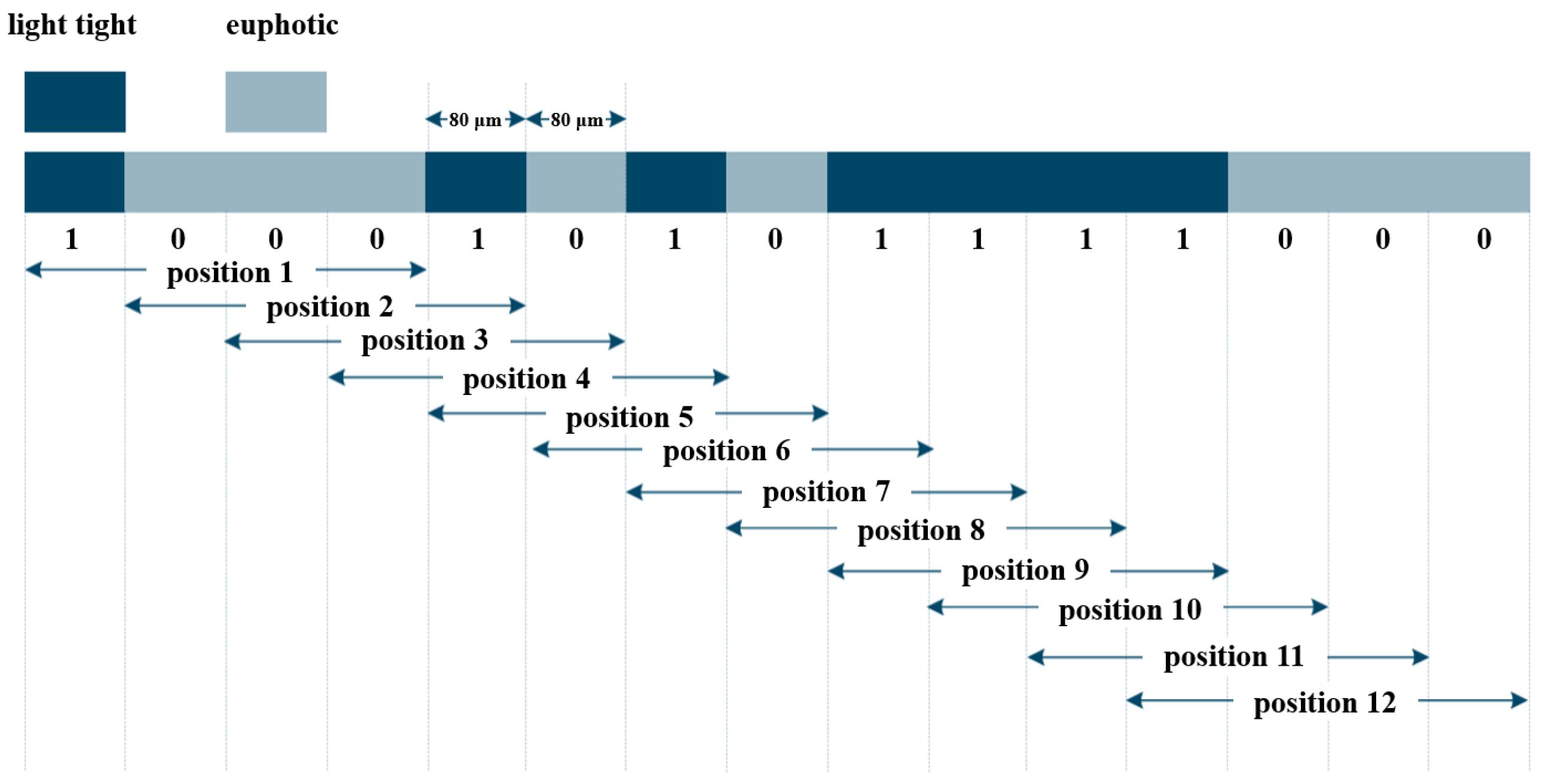

3.1. Non-Embedded Encoding

- (1)

- The complexity of encoding and decoding algorithms for absolute tracks increases exponentially with higher precision.

- (2)

- The high-density measurement gratings required for absolute tracks must be fabricated using specialized processes such as electron beam lithography. The micron-level etching precision required results in significantly higher unit manufacturing costs compared to conventional gratings.

- (3)

- Absolute tracks often adopt a multi-track configuration. Clock synchronization issues in the parallel processing of multi-track signals can lead to millisecond-level decoding delays, which are prone to causing cumulative errors in high-speed motion control scenarios.

- = Position of first traversed reference mark in signal period;

- abs = Absolute value;

- sgn = Algebraic sign function (“+1” or “–1”);

- MRR = Number of signal periods between traversed reference marks;

- N = Nominal increment between two fixed reference marks in signal period;

- D = Direction of traverse (+1 or –1); the rightward traverse of the scanning unit (when properly installed) corresponds to +1.

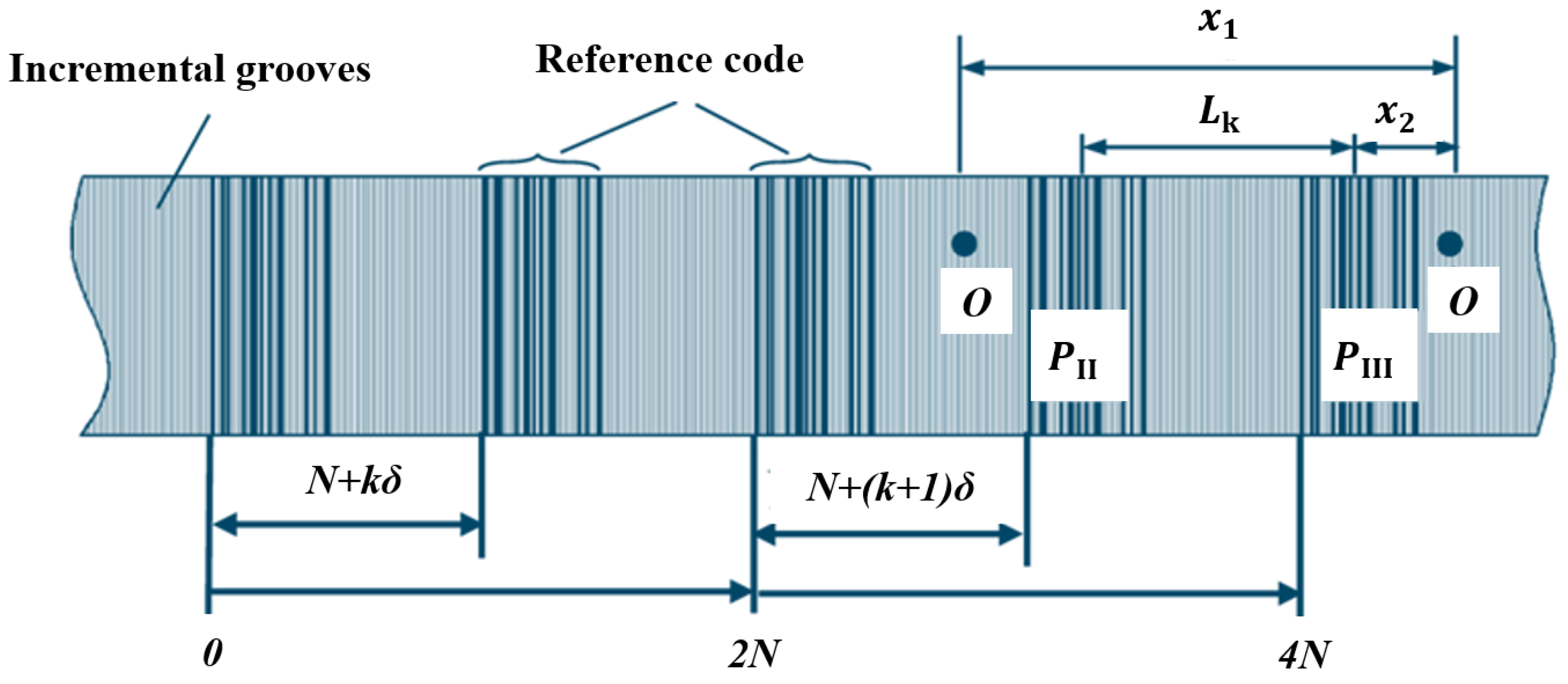

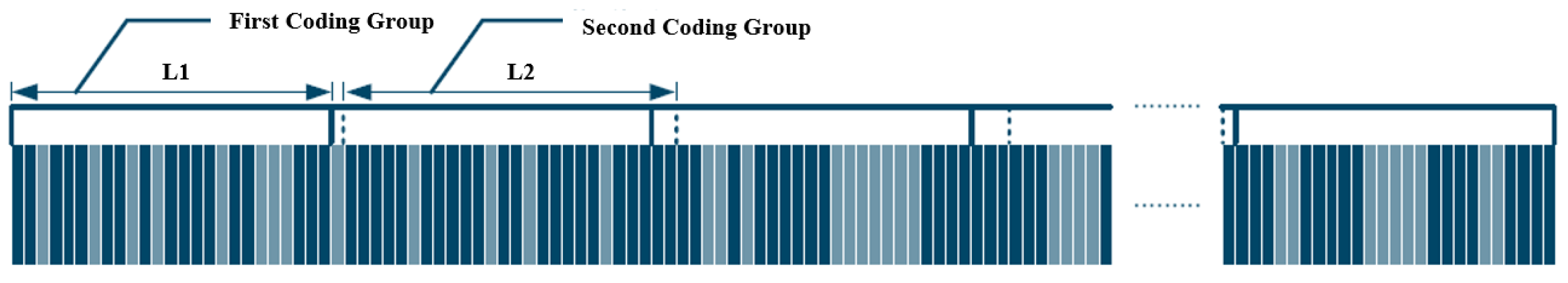

3.2. Embedded Encoding

4. Absolute Linear Encoder Encoding

4.1. Multi-Track Absolute Encoding

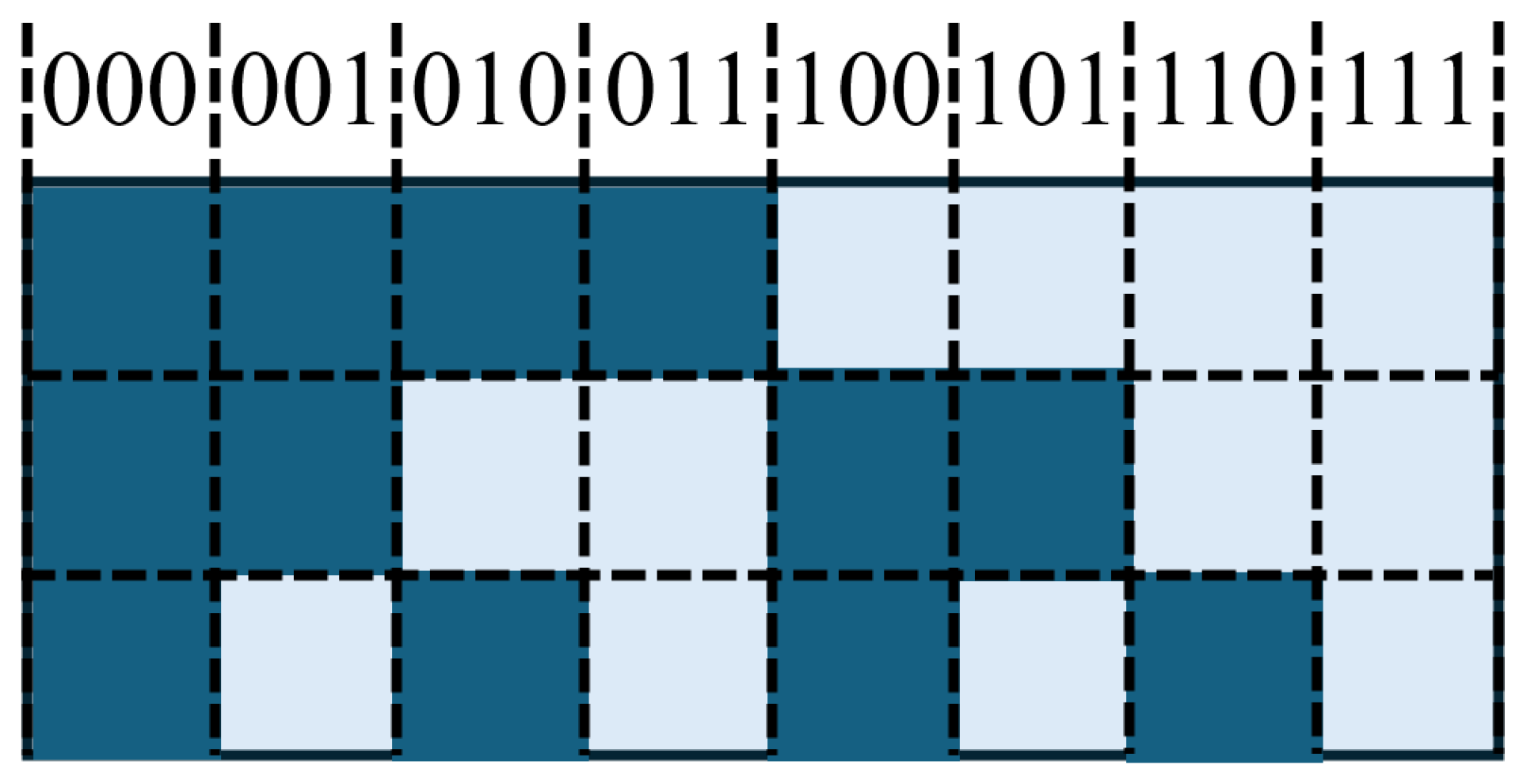

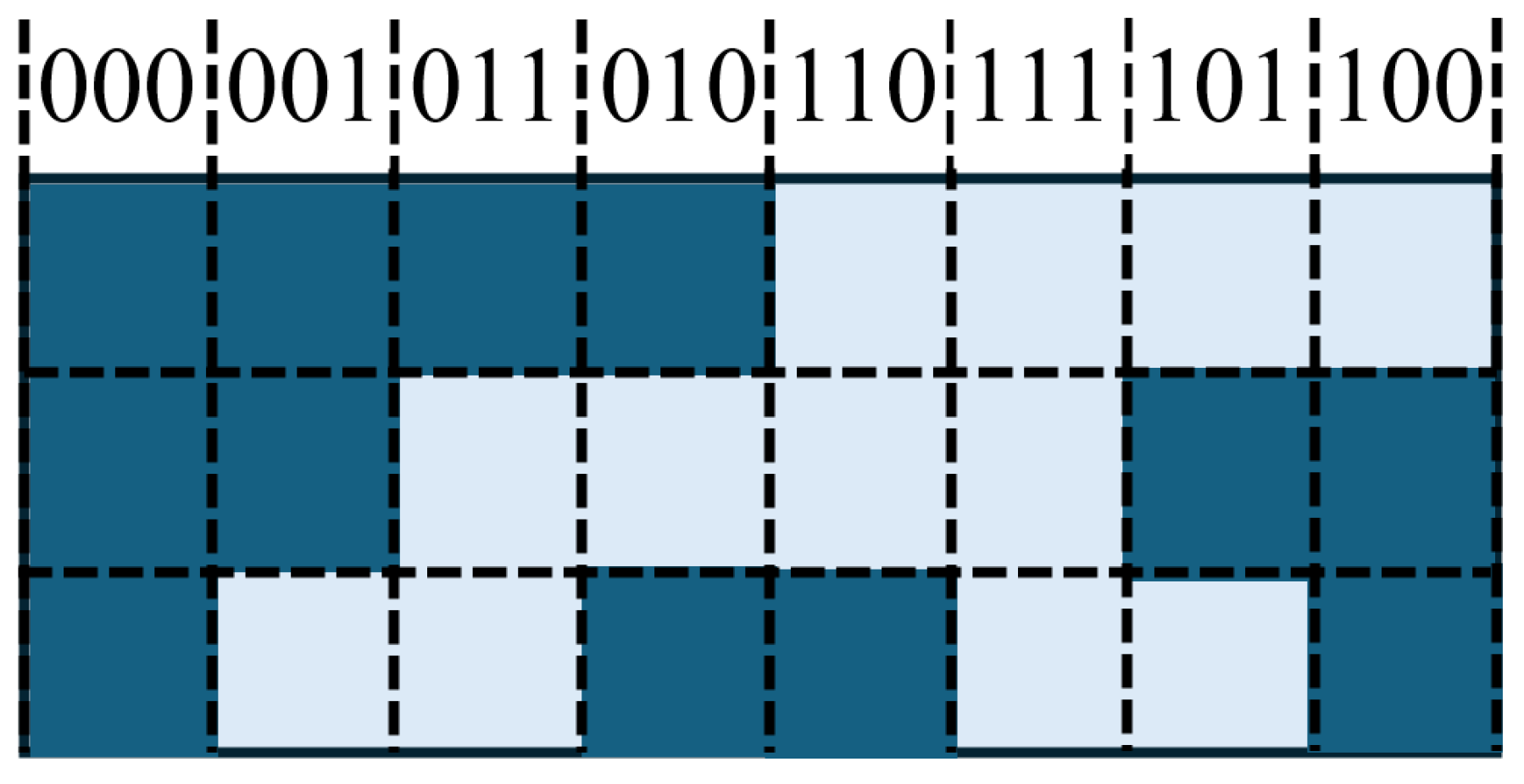

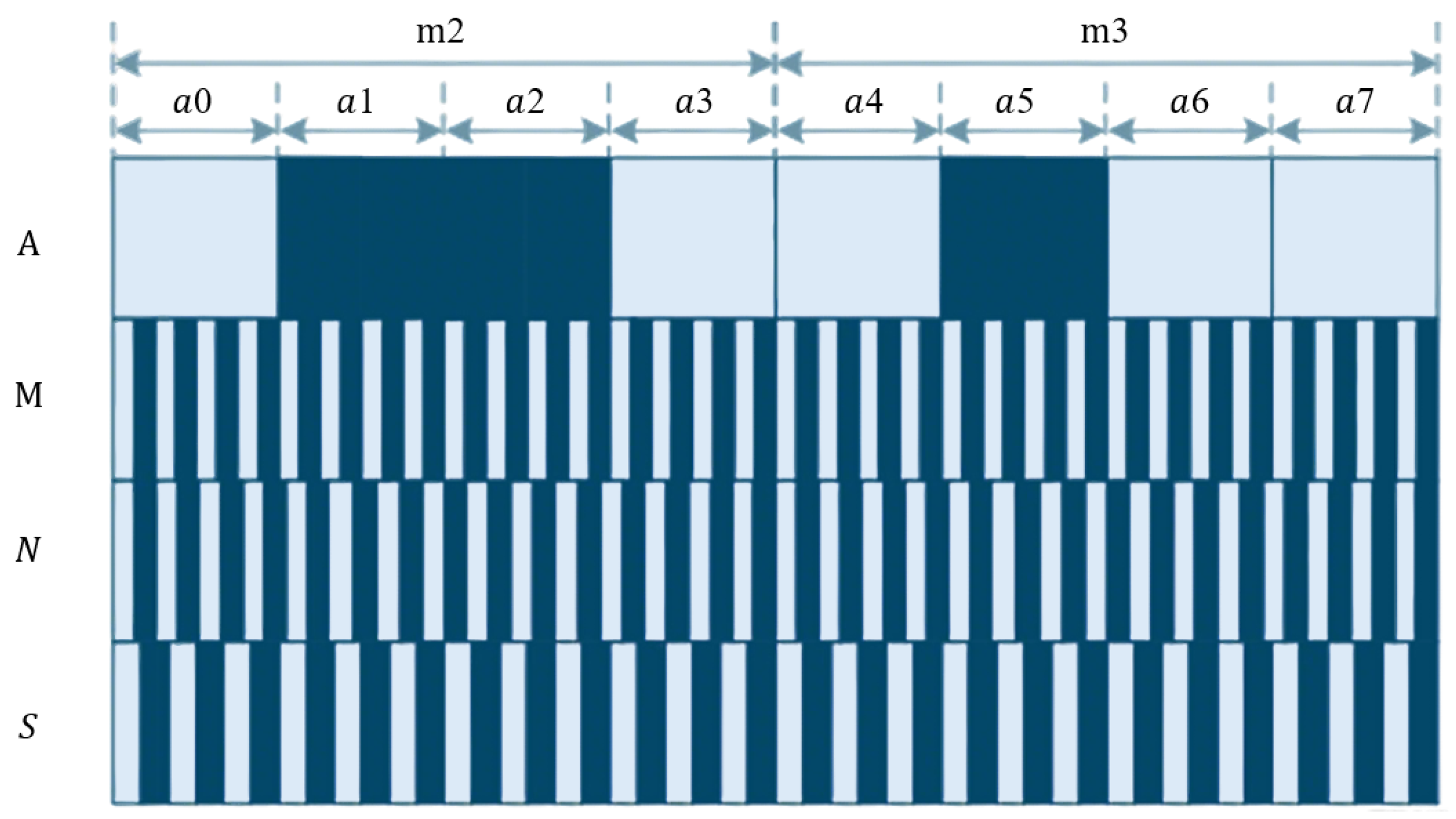

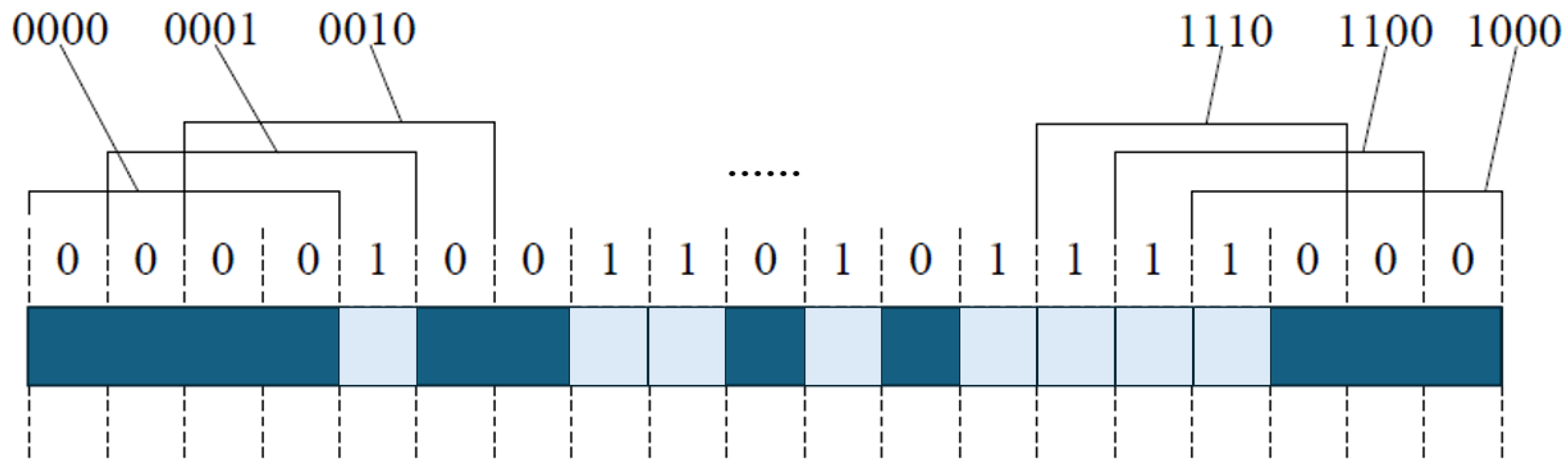

4.1.1. Natural Binary Encoding, Gray Code, and Matrix Encoding

- (1)

- Improving the position resolution requires increasing the number of code tracks, which in turn necessitates more photoelectric sensors. This added complexity hinders the miniaturization and integration of the device.

- (2)

- If multiple bits change simultaneously between adjacent reading intervals, the photoelectric receiver may generate errors due to asynchronous detection.

- (3)

- During the encoding carry process, multiple code bits often change at the same time. If there are errors in the grating lines, inconsistent carry operations may occur across code tracks, potentially leading to incorrect code readings.

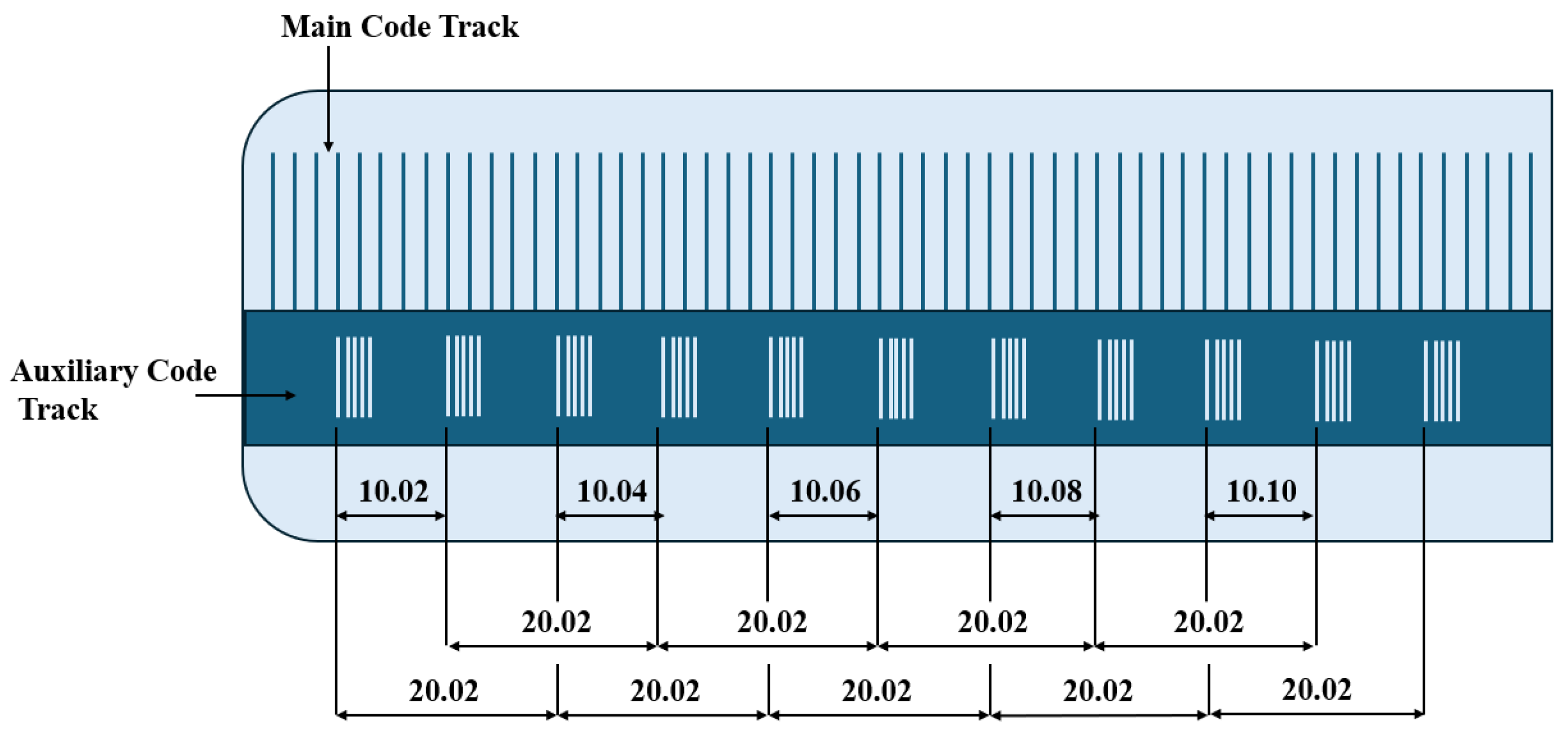

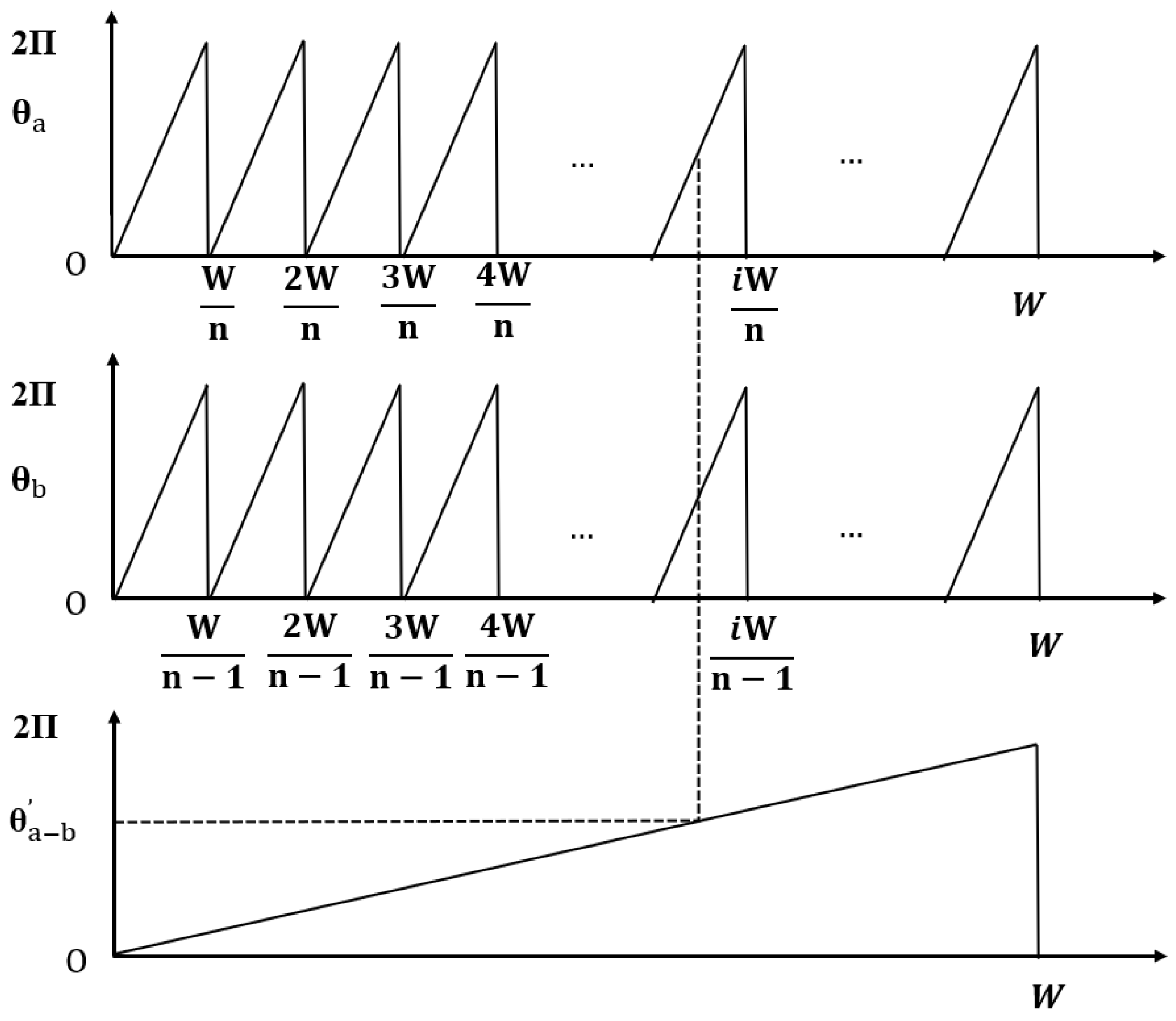

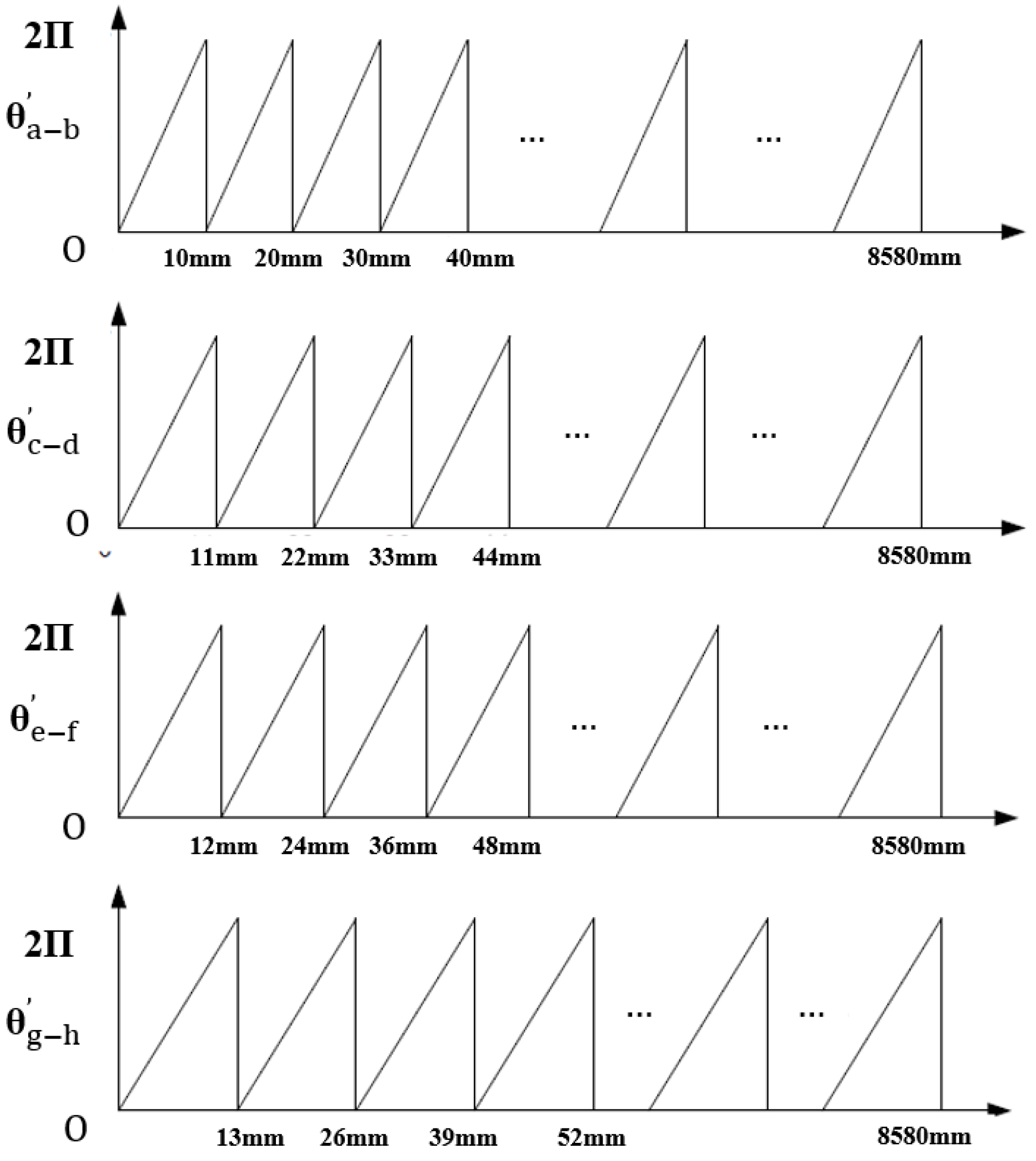

4.1.2. Vernier Encoding

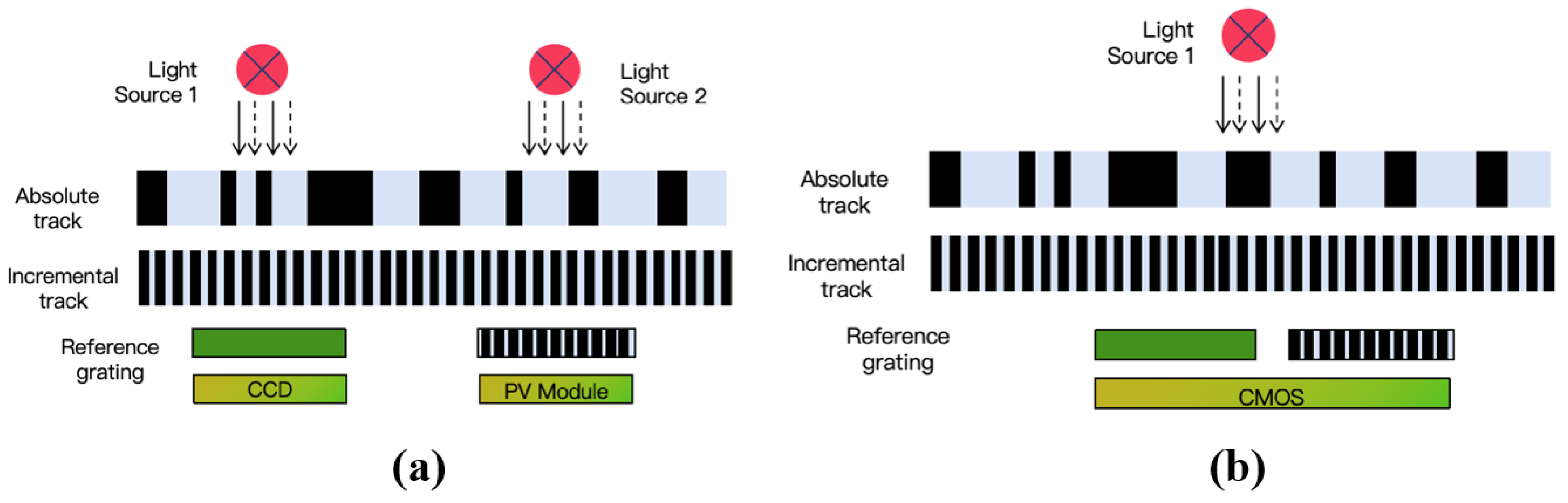

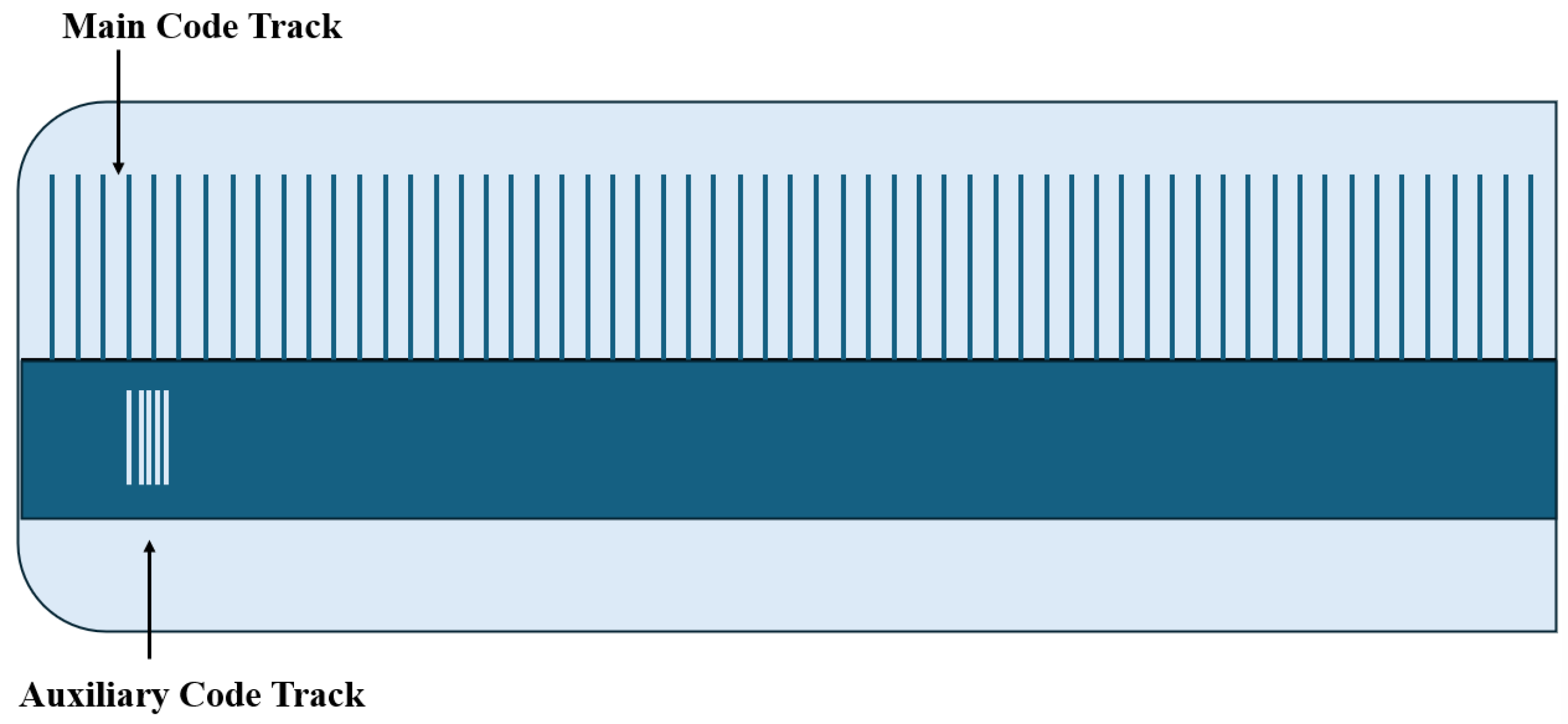

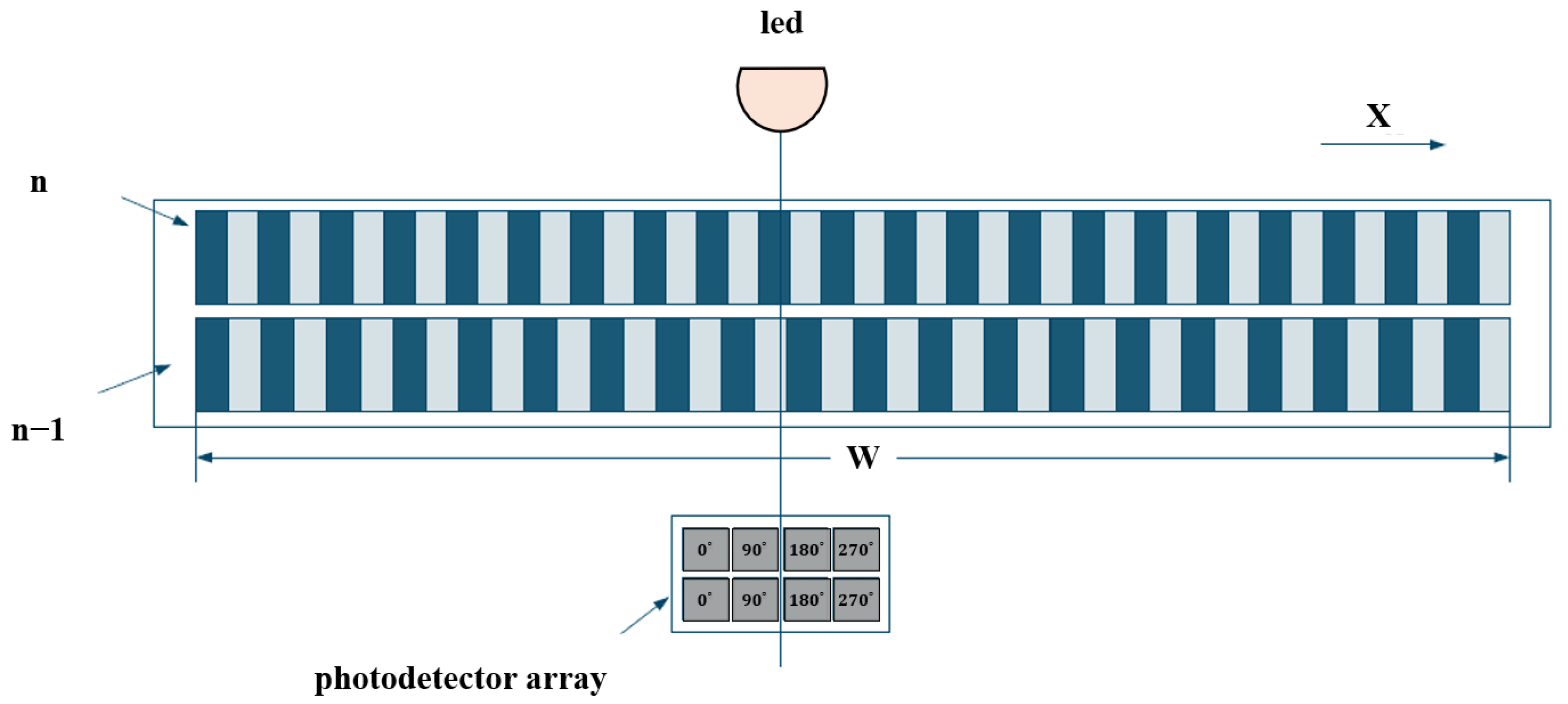

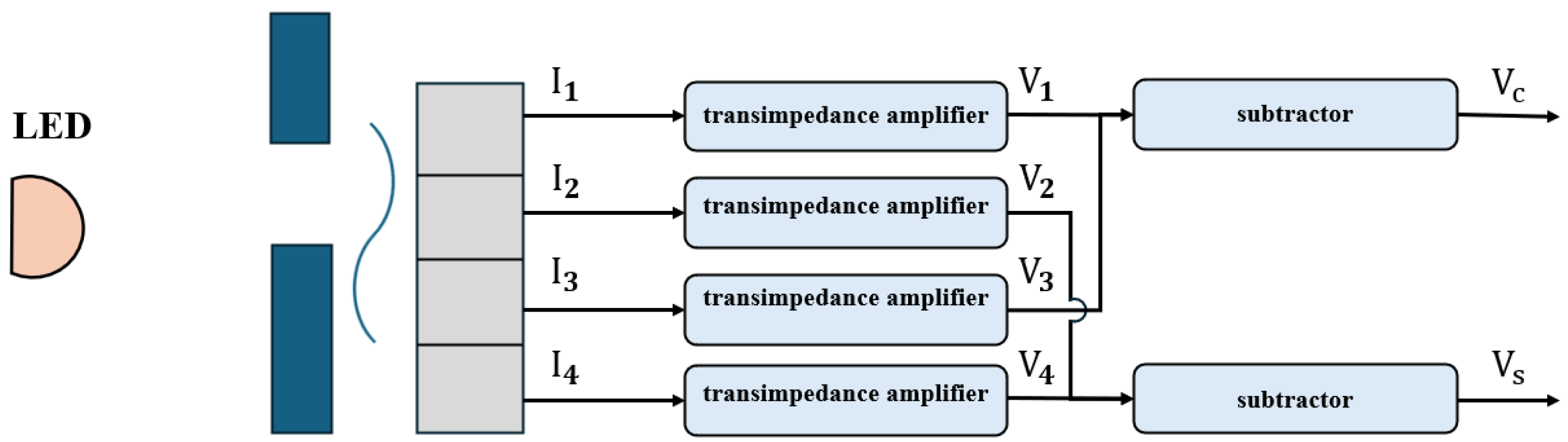

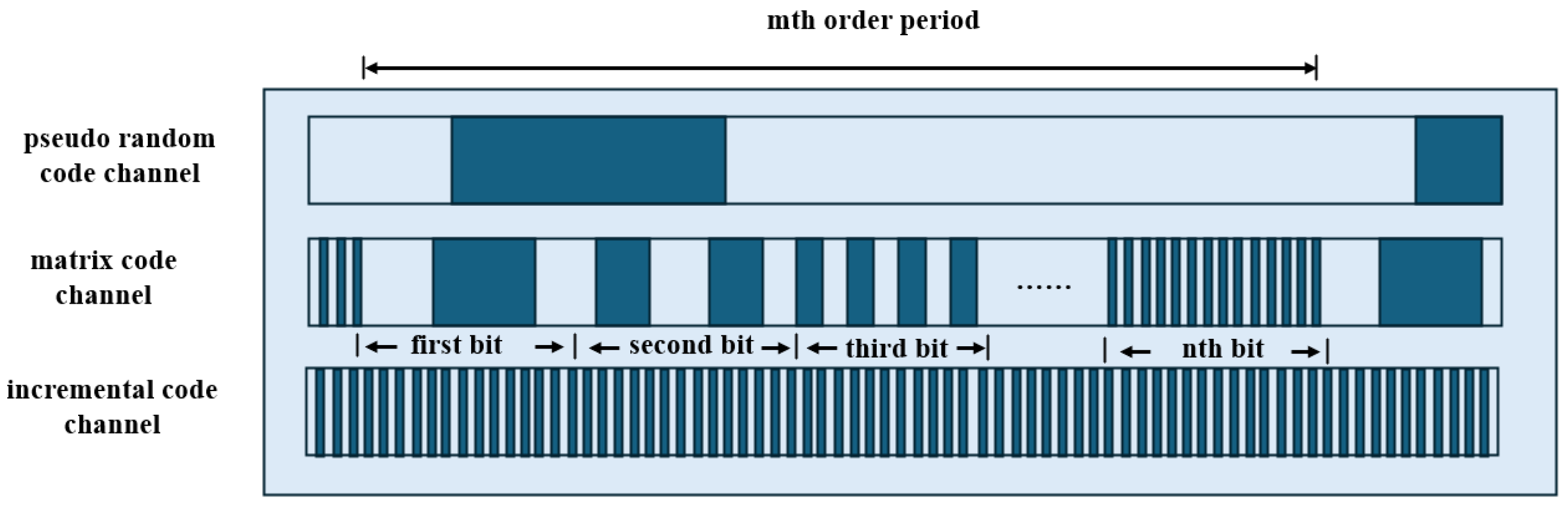

4.1.3. Encoding Method Combining Absolute and Incremental Tracks

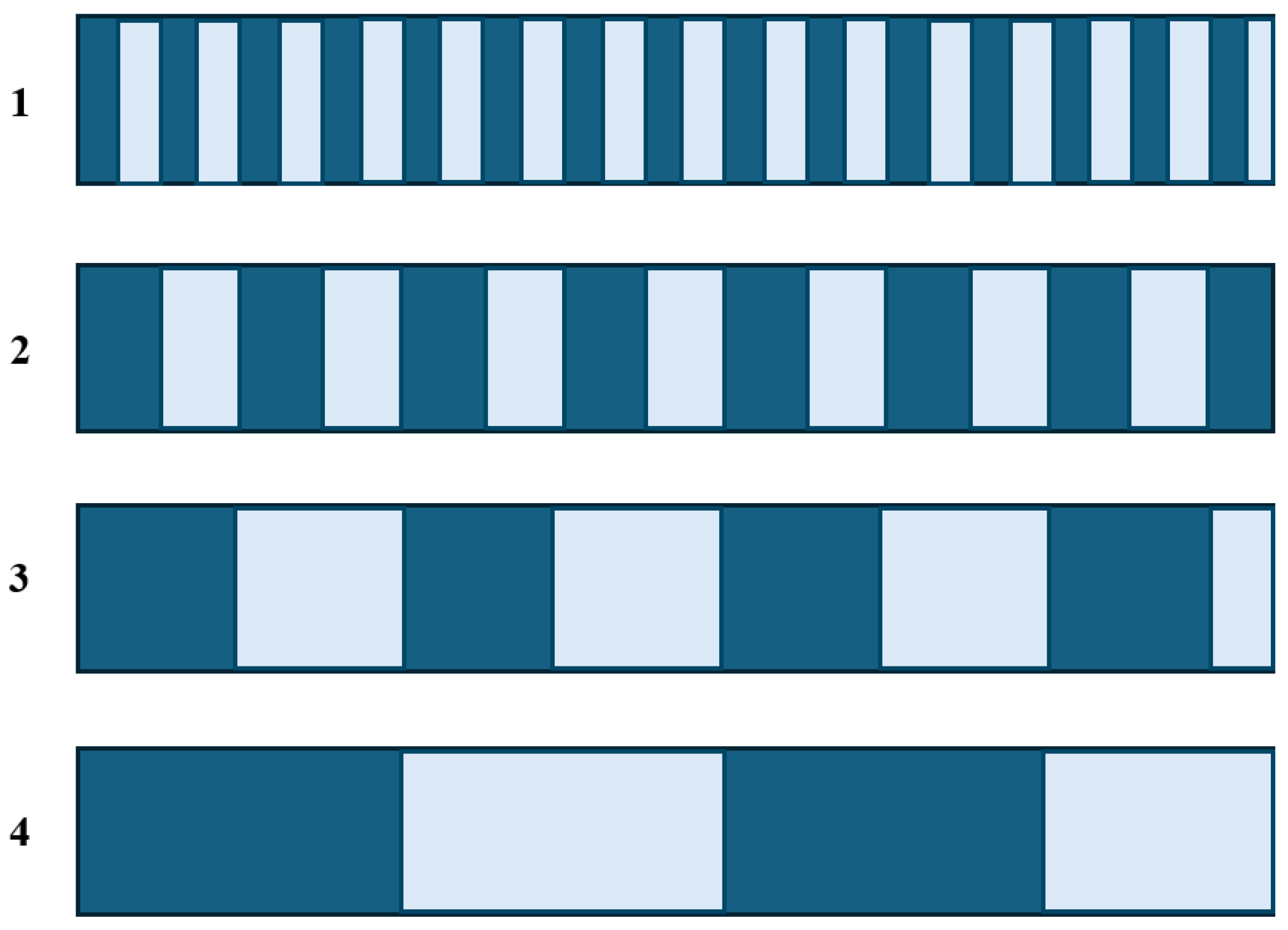

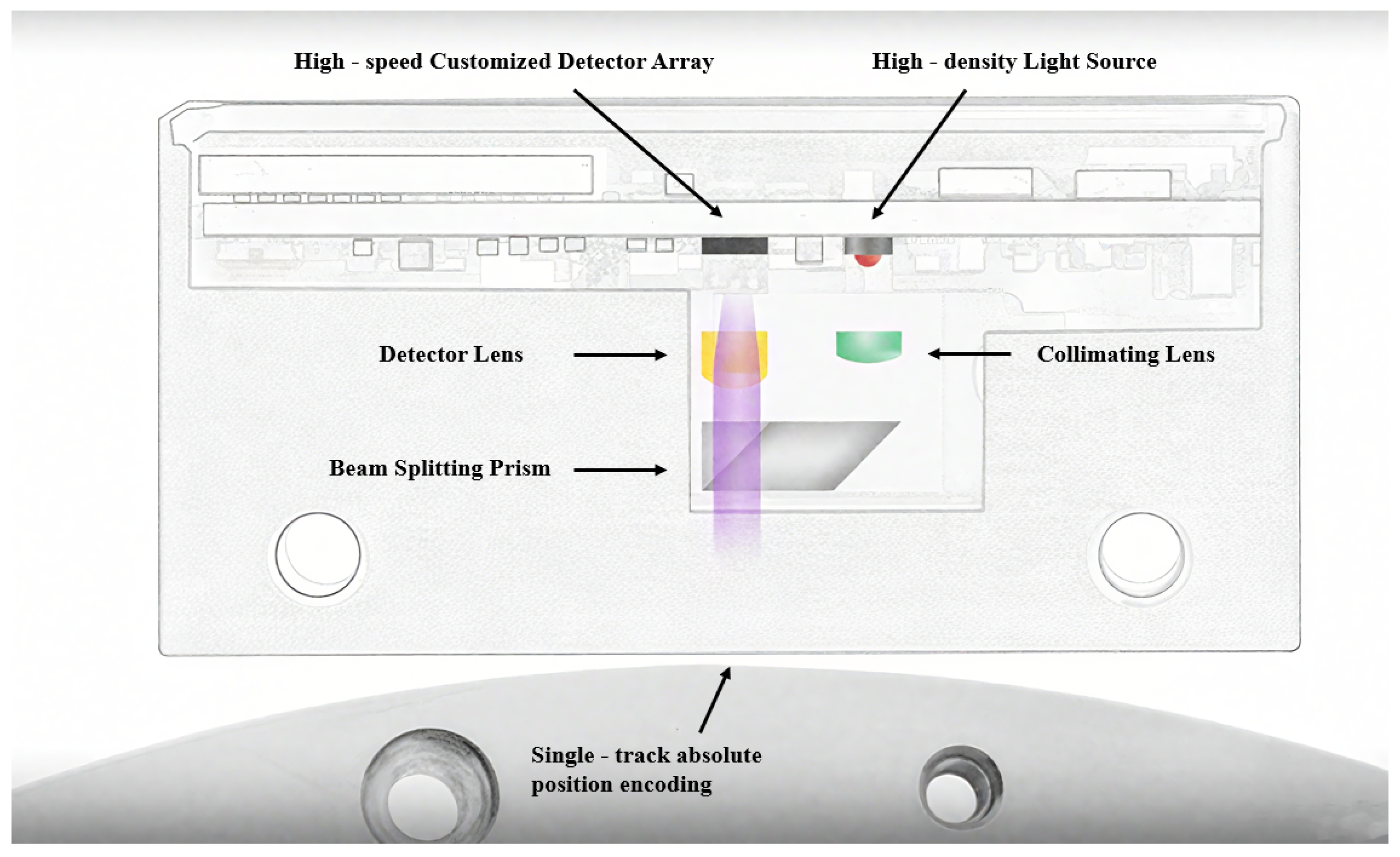

4.2. Single-Track Absolute Encoding

4.2.1. Displacement Continuous Encoding

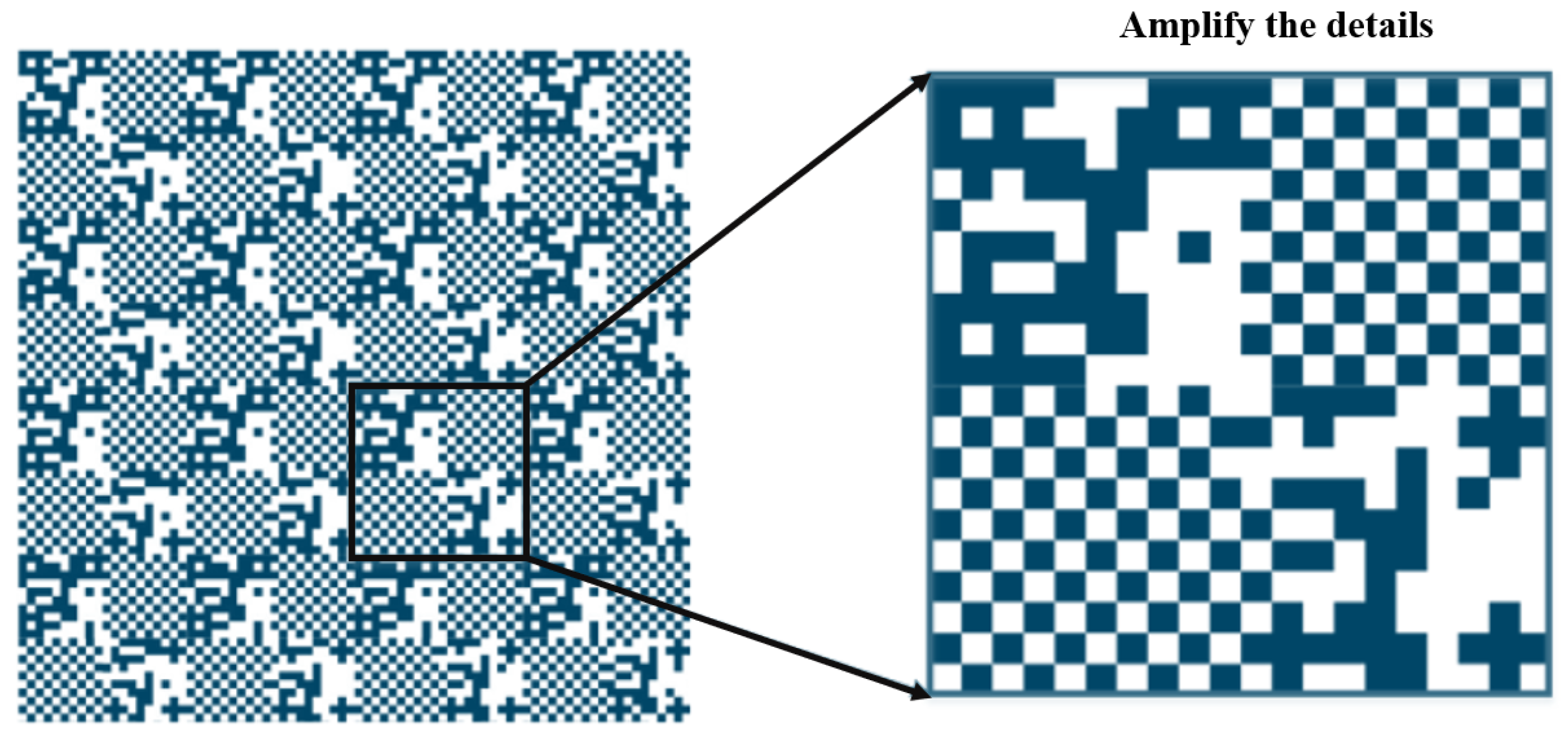

4.2.2. Pseudorandom Sequence Encoding

- (1)

- Single-channel pseudorandom code encoding method: The encoding logic is primarily based on m-sequences, with pseudorandom codes generated using a full-period single-value position function to achieve unique position identification.

- (2)

- Multi-track binary pseudorandom code encoding method: This method extends the single-channel pseudorandom code encoding approach by inscribing multiple pseudorandomly encoded real code tracks onto the linear encoder body. Clear periodic progression exists among the tracks, with the period of each adjacent track decreasing sequentially (i.e., each preceding track has a period that is one unit shorter than the next). Although this method requires a more complex readhead and increases the manufacturing complexity, it allows for the direct output of absolute position values, thereby improving the practicality of the measurement system.

- (3)

- Multi-track p-ary pseudorandom code encoding method: This method is derived from the single-channel pseudorandom encoding approach, with its main enhancement being the expansion of the information capacity by introducing multi-bit encoding to form a p-ary structure. By increasing information redundancy, this multi-valued encoding design effectively reduces the bit error rate during signal transmission and enhances the system’s resistance to interference. Similarly to multi-track binary encoding, it requires a complex readhead, which adds to the manufacturing complexity, but it enables the stable output of absolute position values.

- (4)

- Triple pseudorandom sequence combination encoding method: This method uses a combination of three pseudorandom sequences with cyclic periods , , and for encoding. The bit lengths of the three sequences are 10 bits, 7 bits, and 3 bits, respectively, corresponding to periods of , , and . The bit lengths match their respective period values. The specific sequences are as follows:

- Sequence : 11111111110000000111000011……11011100111000111000;

- Sequence : 111111100001110111100101100……00101000110111000;

- Sequence : 1110010.

By combining multiple sequences, an exponentially expanding encoded sequence can be generated, significantly increasing the coverage range of absolute encoding and enabling absolute position identification in large-scale environments.

4.2.3. Hybrid Encoding

5. Discussion of Errors in Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology

5.1. Errors Related to Manufacturing Processes

5.1.1. Grating Line Inscription Errors

- (1)

- Curvature errors, characterized by the rulings appearing in a curved distribution;

- (2)

- Yaw angle errors, where the actual rulings are not parallel to the ideal ones but intersect within the same plane;

- (3)

- Positional errors, indicating a displacement between the actual and ideal ruling positions.

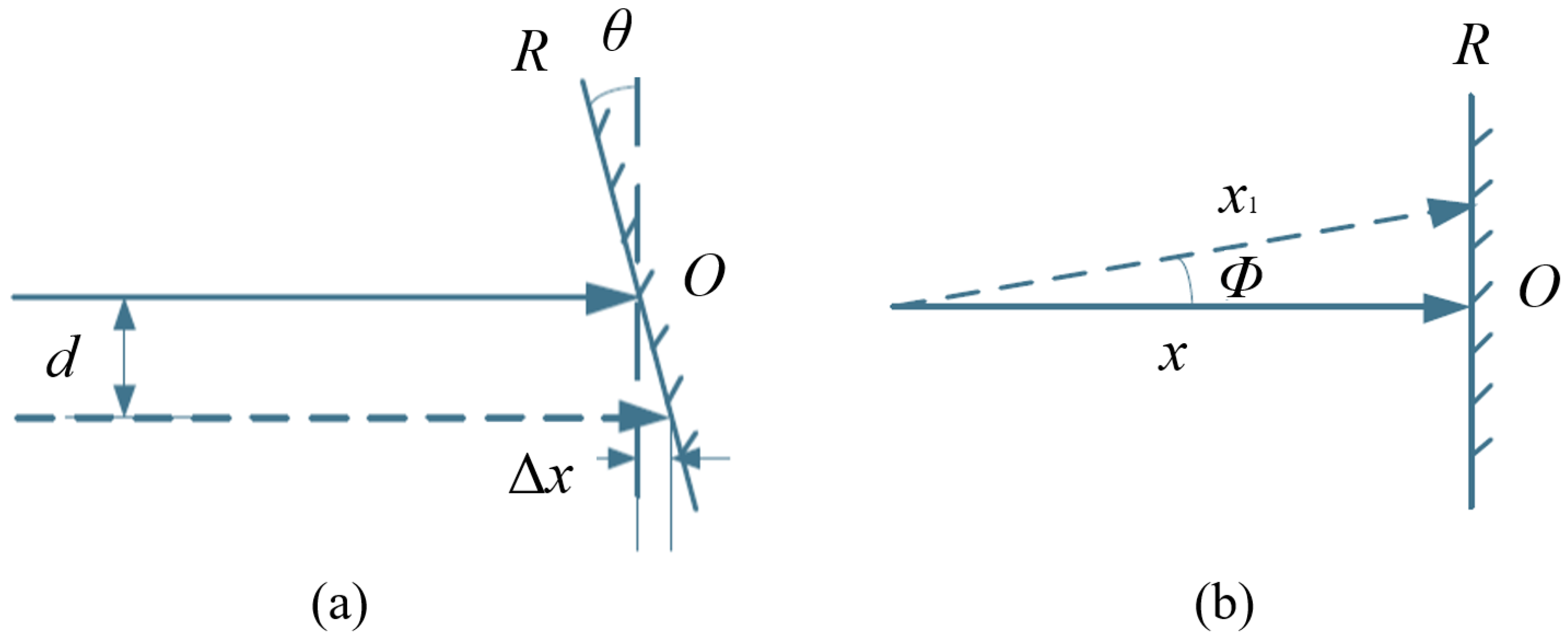

5.1.2. Channel Processing and Alignment Errors

5.1.3. Assembly Errors

5.2. Optical System Errors

5.3. Signal Processing and Encoding Errors

5.3.1. Electronic Interpolation Errors

5.3.2. Encoding and Decoding Errors

5.3.3. Data Transmission and Communication Errors

5.4. Environmental Interference Errors

6. Summary and Outlook

6.1. Research Summary

6.2. Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitehouse, D. A new look at surface metrology. Wear 2009, 266, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Cheng, F.; Tjahjowidodo, T.; Zhou, Y.; Butler, D. A Non-Contact Measuring System for In-Situ Surface Characterization Based on Laser Confocal Microscopy. Sensors 2018, 18, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Kim, S.W.; Bosse, H.; Haitjema, H.; Chena, Y.L.; Lu, X.D.; Knapp, W.; Weckenmann, A.; Estler, W.T.; Kunzmann, H. Measurement technologies for precision positioning. Cirp Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2015, 64, 773–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, K.; Chen, Z.; Pu, H.; Yu, Z. A new capacitive displacement sensor with nanometer accuracy and long range. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 2306–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dong, Y.; Hu, P.; Fu, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, R.; Dong, Y.; Zou, L.; Tan, J. Large-range displacement measurement in narrow space scenarios: Fiber microprobe sensor with subnanometer accuracy. Photonics Res. 2024, 12, 1877–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Ito, T.; Li, X.; Kim, W.; Gao, W. Design and testing of a four-probe optical sensor head for three-axis surface encoder with a mosaic scale grating. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 094002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Haitjema, H.; Fang, F.; Leach, R.; Cheung, C.; Savio, E.; Linares, J.M. On-machine and in-process surface metrology for precision manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wang, W.; Yu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, W. Polarization-modulated grating interferometer by conical diffraction. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ni, K.; Li, X.; Wu, G.; Yu, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X. An FPGA Platform for Next-Generation Grating Encoders. Sensors 2020, 20, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, J.H.; Lei, Y.H.; Zheng, J.B.; Shan, Y.Z.; Guo, D.Y.; Guo, J.C. Analysis of period and visibility of dual phase grating interferometer. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 058701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Yin, Z.; Hu, P.; Tan, J. Multiple-beam grating interferometry and its general Airy formulae. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 164, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Du, H.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Y. Separation and compensation of nonlinear errors in sub-nanometer grating interferometers. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 46259–46279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Tao, X.; Xu, D. High-precision robotic assembly system using three-dimensional vision. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 17298814211027029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lu, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Q. Integrated Micro Sensor Based on Grating Interferometer: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 2073–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Teng, H.; Wang, W.; Li, W. Bidirectional Littrow double grating interferometry for quadruple optical interpolation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Niu, D.; Zhao, G.; Ban, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, P.; Jiang, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, H. Improving the optical subdivision ability of a grating interferometer via double-row reverse blazed gratings. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 168, 107676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Chen, M.; Huang, W. A six-degree-of-freedom measurement system for the motion accuracy of linear stages. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 1998, 38, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Gao, L.; Zhao, P.; Yang, M.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Huang, G.; Wang, S.; Luo, L.; Li, X. Towards multi-dimensional atomic-level measurement: Integrated heterodyne grating interferometer with zero dead-zone. Light Adv. Manuf. 2025, 6, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, G.; Lu, H.; Ni, K. Design and testing of a compact optical prism module for multi-degree-of-freedom grating interferometry application. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, L.; Zhu, J.; Shi, N.; Li, X. An ultra-precision absolute-type multi-degree-of-freedom grating encoder. Sensors 2022, 22, 9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, X.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. A precise reference position detection method for linear encoders by using a coherence function algorithm. In Proceedings of the Optical Metrology and Inspection for Industrial Applications IV, Beijing, China, 12–14 October 2016; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume 10023, pp. 278–282. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Dejima, S.; Kiyono, S. A dual-mode surface encoder for position measurement. Sens. Actuator A-Phys. 2005, 117, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Lu, X.; Qiao, D.; Zou, L.; Huang, X.; Tan, J.; Lu, Z. Two-dimensional displacement measurement based on two parallel gratings. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2018, 89, 065105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Kajima, M.; Gonda, S.; Minoshima, K.; Fujimoto, H.; Zeng, L. Accurate measurement of orthogonality of equal-period, two-dimensional gratings by an interferometric method. Metrologia 2012, 49, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, S.; Li, X. A Reflective-Type Heterodyne Grating Interferometer for Three-Degree-of-Freedom Subnanometer Measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 7007509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Le, V.; Xiong, S.; Yang, Y.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, G. Dual-comb spectroscopy resolved three-degree-of-freedom sensing. Photonics Res. 2021, 9, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petz, M.; Ritter, R. Reflection grating method for 3D measurement of reflecting surfaces. In Proceedings of the Optical Measurement Systems for Industrial Inspection II: Applications in Production Engineering, Munich, Germany, 18–22 June 2001; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, K.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Q. Measurement uncertainty evaluation of the three degree of freedom surface encoder. In Proceedings of the Optical Metrology and Inspection for Industrial Applications IV, Beijing, China, 12–14 October 2016; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016; Volume 10023, pp. 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, G. A new 6-degree-of-freedom measurement method of X-Y stages based on additional information. Precis. Eng.-J. Int. Soc. Precis. Eng. Nanotechnol. 2013, 37, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathey, B.; Cousineau, S.; Aleksandrov, A.; Zhukov, A. First six dimensional phase space measurement of an accelerator beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 064804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.T.; Chen, C.W. A high accuracy six-dimensional motion measuring device: Design and accuracy evaluation. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 191, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Kim, K.C.; Bae, E.; Kim, S.; Kwak, Y. Six-degree-of-freedom displacement measurement system using a diffraction grating. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2000, 71, 3214–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liao, B.; Shi, N.; Li, X. A compact and high-precision three-degree-of-freedom grating encoder based on a quadrangular frustum pyramid prism. Sensors 2023, 23, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Moon, W. A new linear encoder-like capacitive displacement sensor. Measurement 2006, 39, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhou, C.; Jia, W.; Wang, J.; Xiang, C.; Sun, P.; Xie, Y.; Ye, Z.; Li, J.; Jin, G. Three-dimensional measurement of rotating combinative Dammann gratings. In Proceedings of the Holography, Diffractive Optics, and Applications IX, Hangzhou, China, 20–23 October 2019; pp. 352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, A.; Gao, W.; Kim, W.; Hosono, K.; Shimizu, Y.; Shi, L.; Zeng, L. A sub-nanometric three-axis surface encoder with short-period planar gratings for stage motion measurement. Precis. Eng. 2012, 36, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Z.; Lu, B.H.; Ding, Y.C.; Li, D.C.; Tang, Y.P.; Jin, T. A measurement system for step imprint lithography. Key Eng. Mater. 2005, 295–296, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Gao, W.; Arai, Y.; Lijiang, Z. Design and construction of a two-degree-of-freedom linear encoder for nanometric measurement of stage position and straightness. Precis. Eng. 2010, 34, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shimizu, Y.; Muto, H.; Ito, S.; Gao, W. Design of a three-axis surface encoder with a blue-ray laser diode. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 523, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, W.; Muto, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Ito, S.; Dian, S. A six-degree-of-freedom surface encoder for precision positioning of a planar motion stage. Precis. Eng.-J. Int. Soc. Precis. Eng. Nanotechnol. 2013, 37, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shimizu, Y.; Ito, T.; Cai, Y.; Ito, S.; Gao, W. Measurement of six-degree-of-freedom planar motions by using a multiprobe surface encoder. Opt. Eng. 2014, 53, 122405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cui, C. Grating interferometric precision nanometric measurement technology. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2024, 32, 2591–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Cui, C.; Lei, X.; Li, Q.; Yan, S.; Li, X.; Wang, G. A Review of Optical Interferometry for High-Precision Length Measurement. Micromachines 2024, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Shan, S.; Li, X. A review: Laser interference lithography for diffraction gratings and their applications in encoders and spectrometers. Sensors 2024, 24, 6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, A.; Ding, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, Q.; Pan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, H. A tip-tilt-piston electrothermal micromirror array with integrated position sensors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wu, T.; Lin, J.; Yang, L.; Zhu, J. Optical frequency comb frequency-division multiplexing dispersive interference multichannel distance measurement. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2023, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, R.; Yu, Z.; Peng, K.; Pu, H. A high-accuracy capacitive absolute time-grating linear displacement sensor based on a multi-stage composite method. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 8969–8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yu, X. Research on Absolute Length Measurement Gratings and Error Correction. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1996, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T. Research on a New Type of Grating Displacement Sensor. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Design of Intelligent Calibration Absolute Linear Encoder System Based on Dual Reading Heads. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, L. Research on Gray Code Encoding Method. Mod. Electron. Tech. 2006, 29, 11–12+15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review of Exhibits in the Digital Display Device (Displacement Measurement Device) Industry at CIMT2023. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2023, 35–39.

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Dong, Y. Development and Application of JFT Series Absolute Linear Encoders. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2021, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrikola, T.; Couteau, G.; Ishai, Y.; Jarecki, S.; Sahai, A. On pseudorandom encodings. In Theory of Cryptography Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 639–669. [Google Scholar]

- Denić, D.; Miljković, G.; Lukić, J.; Arsić, M. Pseudorandom position encoder with improved zero position adjustment. Facta Univ.-Ser. Electron. Energ. 2012, 25, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljkovic, G.S.; Denic, D.B. Redundant and flexible pseudorandom optical rotary encoder. Elektron. Elektrotech. 2020, 26, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljković, G.; Denić, D.; Pešić, M.; Arsić, M. Improved pseudorandom absolute position encoder with reliable code reading method. Facta Univ. Ser. Autom. Control Robot. 2013, 12, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X. Cross-scale structures fabrication via hybrid lithography for nanolevel positioning. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, T.; Li, X. High dynamic wavefront stability control for high-uniformity periodic microstructure fabrication. Precis. Eng. 2025, 93, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Bayanheshig; Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Hu, P.; Fu, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, R.; et al. Controlling the wavefront aberration of a large-aperture and high-precision holographic diffraction grating. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Qian, X.; Wang, X.; Gui, W.; Gao, W.; Liang, X.; Li, X. HDRSL Net for Accurate High Dynamic Range Imaging-based Structured Light 3D Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 5486–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, X.; Huang, H.; Qian, X.; Feng, F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Gui, W.; Li, X. Global phase accuracy enhancement of structured light system calibration and 3D reconstruction by overcoming inevitable unsatisfactory intensity modulation. Measurement 2024, 236, 114952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G. Modern Grating Measurement Technology. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2002, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Latest Developments in Grating Measurement Technology for Machine Tools. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2004, 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt, K.; Seitz, P. Absolute, high-resolution optical position encoder. Appl. Opt. 1996, 35, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Yao, P.; Li, X. Miniaturized Large-grating-clearance Linear Encoder based on Beam-Splitting Optical System with MOEMS LD and Wireless Moving Part for Rebound Nondestructive Testing. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International NanoElectronics Conference (INEC)/Symposium on Nanoscience and Nanotechnology in China, Hong Kong, China, 3–8 January 2010; pp. 1315–1316. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, T.B.; Jeong, D.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.A. Tape Measuring System using Linear Encoder and Digital Camera. In Proceedings of the Conference on Optical Measurement Systems for Industrial Inspection VIII, Munich, Germany, 13–16 May 2013; Volume 8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pan, C.F.; Li, C.; Menghrajani, K.; Schmidt, M.; Li, A.; Fan, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H. Two-photon polymerization lithography for imaging optics. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 042002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Gui, W.; Gao, W.; Liang, X.; Li, X. Reliable 3D Reconstruction with Single-Shot Digital Grating and Physical Model-Supervised Machine Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5505413. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Soft Sensor Model for Estimating the POI Displacement Based on a Dynamic Neural Network. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform. 2021, 25, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qian, X.; Wang, X.; Gui, W.; Liang, X.; Li, X. A High-Accuracy and Reliable End-to-End Phase Calculation Network and Its Demonstration in High Dynamic Range 3D Reconstruction. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2025, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G. Latest Developments in Displacement Measurement Technology and Its Sensors. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2005, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Lu, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, G.; Wang, X.; Zhai, Q.; Ni, K. Patterning nanoscale crossed grating with high uniformity by using two-axis Lloyd’s mirrors based interference lithography. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, W.; Shimizu, Y.; Ito, S. A two-axis Lloyd’s mirror interferometer for fabrication of two-dimensional diffraction gratings. CIRP Ann. 2014, 63, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, J.; Suzuki, A.; Sato, R.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Improved algorithms of data processing for dispersive interferometry using a femtosecond laser. Sensors 2023, 23, 4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Xing, X.; Hu, P.; Wang, J.; Tan, J. Double-diffracted spatially separated heterodyne grating interferometer and analysis on its alignment tolerance. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Hu, P.; Tan, J. Fused-like angles: Replacement for roll-pitch-yaw angles for a six-degree-of-freedom grating interferometer. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2021, 22, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, R.; Bai, J. High-precision chromatic confocal technologies: A review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Influence of surface tilt angle on a chromatic confocal probe with a femtosecond laser. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Confocal probe based on the second harmonic generation for measurement of linear and angular displacements. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 11982–11993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Astuti, W.; Sato, R.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Theoretical investigation for angle measurement based on femtosecond maker fringe. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sato, R.; Shimizu, H.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Investigation of angle measurement based on direct third harmonic generation in centrosymmetric crystals. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, J.; Sato, R.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Angle measurement based on second harmonic generation using artificial neural network. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2023, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Li, X.; Fischer, A.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, C.; Shimomura, R.; Gao, W. Signal processing and artificial intelligence for dual-detection confocal probes. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 25, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Guan, J.; Wen, F.; Tan, J. High-resolution and wide range displacement measurement based on planar grating. Opt. Commun. 2017, 404, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Optical Sensors for Multi-Axis Angle and Displacement Measurement Using Grating Reflectors. Sensors 2019, 19, 5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Fan, S.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Shi, Y.; Yin, L.; Lu, B. Design of a precise and robust linearized converter for optical encoders using a ratiometric technique. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 125003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lei, B.; Shi, Y.; Yin, L.; Lu, B. Ratiometric-linearization-based high-precision electronic interpolator for sinusoidal optical encoders. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 8224–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Luo, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Hu, P.; Fu, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, R.; Dong, Y.; Tan, J. Focus on sub-nanometer measurement accuracy: Distortion and reconstruction of dynamic displacement in a fiber-optic microprobe sensor. Light. Adv. Manuf. 2024, 5, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hu, P.C.; Fu, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, R.; Tan, J. Long range dynamic displacement: Precision PGC with sub-nanometer resolution in an LWSM interferometer. Photonics Res. 2021, 10, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Cui, J.; Tan, J. Simultaneous multi-channel absolute position alignment by multi-order grating interferometry. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G. Moiré fringes in metrology. Opt. Lasers Eng. 1984, 5, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Gao, L.; Wu, Y.; Wu, C. Application of Longitudinal Moiré Fringes in Autocollimators. Acta Photonica Sin. 2008, 37, 2544–2547. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Tian, X. Application of Grating Encoders in CNC System for Peripheral Grinding of Indexable Inserts. Instrum. Tech. Sens. 2013, 18–19+24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q. Research Progress and Technical Difficulties of High-Precision Absolute Linear Encoders. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2012, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patorski, K. I The self-imaging phenomenon and its applications. Prog. Opt. 1989, 27, 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kyvalsky, J. The self-imaging phenomenon and its applications. In Proceedings of the Photonics, Devices, and Systems II, Prague, Czech Republic, 26–29 May 2002; Volume 5036, pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Zhang, R.; Niu, Q.; Ma, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Xin, C. Out-of-plane displacement sensor based on the Talbot effect in angular-modulated double-layer optical gratings. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 9873–9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kao, C.F.; Lu, M.H. Optical encoder based on the fractional Talbot effect. Opt. Commun. 2005, 250, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.J.; Ebrahim-Zadeh, M.; Samanta, G.K. Talbot effect based sensor measuring grating period change in subwavelength range. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, H.L.; Bhatnagar, A.; Miller, D.A. Transform spectrometer based on measuring the periodicity of Talbot self-images. Opt. Lett. 2001, 26, 1645–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, E.; Atabaki, A.H.; Han, N.; Ram, R.J. Miniature, sub-nanometer resolution Talbot spectrometer. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 2434–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghi Tavassoly, M.; Abolhassani, M. Specification of spectral line shape and multiplex dispersion by self-imaging and Moiré technique. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2004, 41, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podanchuk, D.V.; Goloborodko, A.A.; Kotov, M.M.; Kovalenko, A.V.; Kurashov, V.N.; Dan’ko, V.P. Adaptive wavefront sensor based on the Talbot phenomenon. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, B150–B157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Gill, P.; Molnar, A. Light field image sensors based on the Talbot effect. Appl. Opt. 2009, 48, 5897–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, G.S.; Ambrosini, D. Talbot effect application: Measurement of distance with a Fourier-transform method. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testorf, M.; Jahns, J.; Khilo, N.A.; Goncharenko, A.M. Talbot effect for oblique angle of light propagation. Opt. Commun. 1996, 129, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xue, G.; Zhai, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yu, K.; Huang, G.; Wang, M.; Zhong, A.; Zhu, L.; Yan, S. Planar diffractive grating for magneto-optical trap application: Fabrication and testing. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 9358–9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yan, S.; Du, Z.; Wei, C.; Wang, G. High-efficiency gold-coated cross-grating for heterodyne grating interferometer with improved signal contrast and optical subdivision. Opt. Commun. 2015, 339, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Fei, Y.; Wang, Z. Research on the planar nanoscale displacement measurement system of 2-D grating. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. 2007, 30, 529–532. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Li, B.; Shi, Y.; Tsai, D.P.; Liu, A.Q.; Huang, W.; Zhu, W. Metasurface micro/nano-optical sensors: Principles and applications. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 11598–11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, H.; Zeng, Q.; Xiong, X. High-precision displacement measurement model for the grating interferometer system. Opt. Eng. 2020, 59, 045101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Li, X. Grating interferometer with redundant design for performing wide-range displacement measurements. Sensors 2022, 22, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, C. Ultraprecision real-time displacements calculation algorithm for the grating interferometer system. Sensors 2019, 19, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Kimura, A. A three-axis displacement sensor with nanometric resolution. CIRP Ann. 2007, 56, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Chang, D.; Hu, P.C.; Tan, J.B. Spatially separated heterodyne grating interferometer for eliminating periodic nonlinear errors. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 31384–31393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Jia, W.; Wang, J. A new high-precision device for one-dimensional grating period measurement. In Proceedings of the Holography, Diffractive Optics, and Applications XII, Online, 5–12 December 2022; pp. 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel, M. Precision measurement of complex optics using a scanning-point multiwavelength interferometer operating in the visible domain. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2023, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Song, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L. Three-dimensional nano-displacement measurement by four-beam laser interferometry. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2024, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Grating interferometer: The dominant positioning strategy in atomic and close-to-atomic scale manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 1227–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Gao, L.; Huang, G.; Lei, X.; Cui, C.; Wang, S.; Yang, M.; Zhu, J.; Yan, S.; Li, X. A wavelength-stabilized and quasi-common-path heterodyne grating interferometer with sub-nanometer precision. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 7002509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yan, S.; Ding, D.; Wang, G. Two-dimensional diagonal-based heterodyne grating interferometer with enhanced signal-to-noise ratio and optical subdivision. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 064102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Chang, D.; Tan, J.; Yang, R.; Yang, H.; Fu, H. Displacement measuring grating interferometer: A review. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2019, 20, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Li, W.; Bayanheshig; Bai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, W. Interferometric Precision Displacement Measurement System Based on Diffraction Gratings. Chin. Opt. 2017, 10, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Liu, X. Principle and Error Analysis of Dual-Grating Interference Displacement Sensor. Appl. Optoelectron. Technol. 2012, 27, 41–45+53. [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama, S.; Zheng, J. Precision Displacement Detection Using Diffraction Gratings. Foreign Metrol. 1984, 11–13+26. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, H.; Cao, J.; Yan, S.; Xu, T. Research on Large-Range and High-Resolution Displacement Measurement with Gratings. China Mech. Eng. 2000, 11, 44–46+3. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yang, S.; Wu, L.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Liao, R.; Qu, M.; Quan, X.; Cheng, X. Design and fabrication of a high-performance binary blazed grating coupler for perfectly perpendicular coupling. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 42999–43010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, W. Advancements in displacement metrology based on encoder systems. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual ASPE Meeting, Portland, OR, USA, 19–24 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Yu, H.; Wan, Q.; Zhao, C.; Li, Y. Research Progress and Prospect of Grating Linear Displacement Measurement Technology. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2025, 62, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, D.; Wu, G. Development of Miniature Optical Encoder for Precise Displacement Measurement. Acta Photonica Sin. 2021, 50, 0912001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zong, M. Development of Symmetrical Double-Grating Interferometric Displacement Measuring System. Chin. J. Lasers 2016, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Xie, T. Principle and application of double diffraction grating displacement sensor. Meas. Tech. Pap. 2008, 6, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Gan, T.; Shen, C.Y.; Jarrahi, M.; Ozcan, A. All-optical complex field imaging using diffractive processors. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Goodson, K.E. Subpixel displacement and deformation gradient measurement using digital image/speckle correlation (DISC). Opt. Eng. 2001, 40, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Qian, K.; Xie, H.; Asundi, A. Two-dimensional digital image correlation for in-plane displacement and strain measurement: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2009, 20, 062001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Pan, Y.C. Automated visual inspection in the semiconductor industry: A survey. Comput. Ind. 2015, 66, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamahata, C.; Sarajlic, E.; Krijnen, G.J.M.; Gijs, M.A.M. Subnanometer Translation of Microelectromechanical Systems Measured by Discrete Fourier Analysis of CCD Images. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2010, 19, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H. High speed image acquisition system of absolute encoder. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Electronics and Information Engineering (ICEIE), Nanjing, China, 17–18 September 2016; Proceedings of SPIE Volume 10322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douini, Y.; Riffi, J.; Mohamed Mahraz, A.; Tairi, H. An image registration algorithm based on phase correlation and the classical Lucas-Kanade technique. Signal Image Video Process. 2017, 11, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroosh, H.; Zerubia, J.B.; Berthod, M. Extension of phase correlation to subpixel registration. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2002, 11, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takita, K.; Aoki, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Higuchi, T.; Kobayashi, K. High-accuracy subpixel image registration based on phase-only correlation. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2003, E86A, 1925–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Zitova, B.; Flusser, J. Image registration methods: A survey. Image Vis. Comput. 2003, 21, 977–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliski, R. Image alignment and stitching. In Handbook of Mathematical Models in Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Xie, H.; Xu, B.; Dai, F. Performance of sub-pixel registration algorithms in digital image correlation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riha, L.; Fischer, J.; Smid, R.; Docekal, A. New interpolation methods for image-based sub-pixel displacement measurement based on correlation. In Proceedings of the 24th IEEE Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference, Warsaw, Poland, 1–3 May 2007; IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Technology Conference, Proceedings. pp. 1253–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Galeano-Zea, J.A.; Sandoz, P.; Gaiffe, E.; Pretet, J.L.; Mougin, C. Pseudo-Periodic Encryption of Extended 2-D Surfaces for High Accurate Recovery of Any Random Zone by Vision. Int. J. Optomechatron. 2010, 4, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Feng, M.Q.; Ozer, E.; Fukuda, Y. A Vision-Based Sensor for Noncontact Structural Displacement Measurement. Sensors 2015, 15, 16557–16575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. High-Accuracy Subpixel Image Registration with Large Displacements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 6265–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H.S.; Orchard, M.T.; Chang, E.C.; Martucci, S.A. A fast direct fourier-based algorithm for subpixel registration of images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jing, X.; Zhao, C. Local Upsampling Fourier Transform for accurate 2D/3D image registration. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2012, 38, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelpa, V.; Laurent, G.J.; Sandoz, P.; Galeano Zea, J.; Clevy, C. Subpixelic Measurement of Large 1D Displacements: Principle, Processing Algorithms, Performances and Software. Sensors 2014, 14, 5056–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, M.A.; Jacquot, M.; Laurent, G.J.; Sandoz, P. Digital Holography as Computer Vision Position Sensor with an Extended Range of Working Distances. Sensors 2018, 18, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizar-Sicairos, M.; Thurman, S.T.; Fienup, J.R. Efficient subpixel image registration algorithms. Opt. Lett. 2008, 33, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonacid-Caballer, J.; Pardo-Pascual, J.E.; Ruiz, L.A. Evaluating Fourier Cross-Correlation Sub-Pixel Registration in Landsat Images. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, C. Robust subpixel registration for image mosaicing. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition/1st CJK Joint Workshop on Pattern Recognition, Nanjing, China, 4–6 November 2009; pp. 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Antos, J.; Nezerka, V.; Somr, M. Real-Time Optical Measurement of Displacements Using Subpixel Image Registration. Exp. Tech. 2019, 43, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G. Research on Key Technologies of Absolute Grating Sensors. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Su, X.; Xiang, L.; Sun, X. 3-D shape measurement based on complementary Gray-code light. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2012, 50, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y. A New Type of Absolute Matrix Encoder Disk. Microcomput. Inf. 2010, 26, 93–94+144. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Lin, C. Research and Application of Continuous Displacement Coding Principle. Acta Metrol. Sin. 2003, 24, 29–31+39. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti, W.; Li, K.; Sato, R.; Matsukuma, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W. A second harmonic wave angle sensor with a collimated beam of femtosecond laser. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Ozcan, A. Nonlinear encoding in diffractive information processing using linear optical materials. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JB/T 11505–2013; Linear Encoder for Numerically Controlled Machine Tools, Industry Standard. Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Zhang, W. DSP and SSI Protocol Interface Research for Absolute Encoders. Integr. Circuits Embed. Syst. 2025, 25, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, S.; Yang, Q. Implementation of the EnDat2.2 Interface Protocol Based on Verilog for Position Encoder System. In Proceedings of the MT Translation Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, 23–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.; Gebhardt, A.; Schmid, R. Safety Integration of Absolute Encoders in Industrial Automation Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 9742–9750. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, D.; Xu, Z.; Wu, H.; Zeng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Q. Subdivision Error Compensation Method for Absolute Linear Encoders. Acta Opt. Sin. 2015, 35, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. Reliability Research and Error Analysis of Absolute Linear Encoders. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences), Changchun, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, B.; Gu, G.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Miniaturized Hyperspectral Resolution Imaging Spectrometer of AOTF and Echelle Grating Combination. Acta Opt. Sin. 2023, 43, 1922001. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. Electromagnetically Induced Non-Hermitian Diffraction Grating Assisted by Incoherent Pumping. Acta Opt. Sin. 2023, 43, 1305002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, J.; Yang, L.; Xie, H. Simulation of Moiré Fringes in Liquid Crystal Displays. Acta Opt. Sin. 2022, 42, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, G.; Xing, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Lei, B.; Niu, D.; Li, X.; Lu, B.; Liu, H. Total error compensation of non-ideal signal parameters for Moiré encoders. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 298, 111539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Huang, D.; Lei, Z. An improved high-precision subdivision algorithm for single-track absolute encoder using machine vision techniques. Meas. Control 2019, 52, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lu, X.; Kilikevicius, A.; Gurauskis, D. Methods for Reducing Subdivision Error within One Signal Period of Single-Field Scanning Absolute Linear Encoder. Sensors 2023, 23, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; Xiao, P.; Chen, X.; Cai, N.; Ling, B.W.K. Absolute optical imaging position encoder. Measurement 2015, 67, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, S.; Li, Q. Macro-Micro Composite Linear Encoder Measurement System Based on Virtual Instrument. Acta Photonica Sin. 2018, 47, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, N.; Xiao, P.; Ye, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Ling, B.W.K. Improving the measurement accuracy of an absolute imaging position encoder via a new edge detection method. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2017, 11, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wan, Q.; Mu, Z.; Du, Y.; Liang, L. Novel nano-scale absolute linear displacement measurement based on grating projection imaging. Measurement 2021, 182, 109738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Image-type displacement measurement resolution improvement without magnification imaging. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 015103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wan, Q.; Lu, X.; Du, Y.; Liang, L. High-precision displacement measurement algorithm based on a depth fusion of grating projection pattern. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Park, W.I. Image processing with Optical matrix vector multipliers implemented for encoding and decoding tasks. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Cheng, F.; Tjahjowidodo, T.; Liu, M. Development of an Image Grating Sensor for Position Measurement. Sensors 2019, 19, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, L.; Zhan, X.; Yan, R.; Chang, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J. Physical twinning for joint encoding-decoding optimization in computational optics: A review. Light Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Pu, H.; Liu, X.; Peng, D.; Yu, Z. A time-grating sensor for displacement measurement with long range and nanometer accuracy. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2015, 64, 3105–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.F.; Jia, W.; Zhao, D.; Ye, Z.H.; Sun, P.; Xiang, C.C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C. Traceable and long-range grating pitch measurement with picometer resolution. Opt. Commun. 2020, 476, 126316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Zhuang, S. Research Progress of Precision Positioning Linear Encoders. Laser J. 2010, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinouchi, S.; Imai, T.; Watanabe, A.; Ohara, T.; Wakui, S. A Study on Scanning Optical Encoder: High Resolution Position Sensor Using Laser Interference Scan and Synchronous Phase Detection. J. Jpn. Soc. Precis. Eng. 2009, 75, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cao, G.; Li, L. Linear Encoders in Motion Control Systems. Mech. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2016, 45, 7–10+95. [Google Scholar]

- Gurauskis, D.; Kilikevičius, A.; Borodinas, S. Experimental Investigation of Linear Encoder’s Subdivisional Errors under Different Scanning Speeds. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Lin, L.; Zhai, Q.; Zeng, C.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Development of dielectric-film-based polarization modulation scheme for patterning highly uniform 2d array structures with periodic tunability. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2023, 167, 107627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhong, Z.; Lu, T.; Li, J.; Li, X. Fabrication of optical mosaic gratings. In Proceedings of the Advanced Laser Processing and Manufacturing VIII, Nantong, China, 12–15 October 2024; pp. 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Li, X. Technologies for Fabricating Large-Size Diffraction Gratings. Sensors 2025, 25, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Sato, R.; Kodaka, S.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. A two-axis Lloyd’s mirror interferometer with elastically bent mirrors for fabrication of variable-line-spacing scale gratings. Precis. Eng. 2025, 94, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X. Ultraprecision Grating Positioning Technology for Wafer Stage of Lithography Machine. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. (China) 2022, 59, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukuma, H.; Nagaoka, M.; Hirose, H.; Sato, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W. Repetition frequency control of a mid-infrared ultrashort pulse laser. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2024, 18, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X. Absolute Positioning Method of Grating Displacement Based on Reference-Scale Fusion Signal Distance Coding. Master’s Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences), Changchun, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Research on Grating Signal Processing and Compensation Technology for Matrix Linear Encoders. Master’s Thesis, Changchun University of Science and Technology, Changchun, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Luo, L.; Li, X. Design and parameter optimization of zero position code considering diffraction based on deep learning generative adversarial networks. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2024, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, L.; Gao, L.; Ma, R.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Long binary coding design for absolute positioning using genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the Optical Metrology and Inspection for Industrial Applications X, Beijing, China, 14–17 October 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12769, pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Shimizu, Y.; Ito, S.; Gao, W. Fabrication of scale gratings for surface encoders by using laser interference lithography with 405 nm laser diodes. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2013, 14, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H.; Ni, K. Low-cost lithography for fabrication of one-dimensional diffraction gratings by using laser diodes. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Optical Instruments and Technology: Micro/Nano Photonics and Fabrication, Beijing, China, 17–19 May 2015; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; Volume 9624, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; Ni, K.; Tian, R.; Pang, J. Holographic fabrication of large-constant concave gratings for wide-range flat-field spectrometers with the addition of a concave lens. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.; Tian, R.; Pang, J. Fabrication of a concave grating with a large line spacing via a novel dual-beam interference lithography method. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 10759–10766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, X.; Lu, H.; Yang, L.; Ma, D.; Sun, J.; Ni, K.; Wang, X. Holographic fabrication of an arrayed one-axis scale grating for a two-probe optical linear encoder. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 16028–16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Zhai, Q.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Ni, K.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Polarized holographic lithography system for high-uniformity microscale patterning with periodic tunability. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2021, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, G.; Ni, K.; Wang, X. An orthogonal type two-axis Lloyd’s mirror for holographic fabrication of two-dimensional planar scale gratings with large area. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, T. Research on a New Multi-Segment Distance Code Applied to Grating Measurement. China Mech. Eng. 2014, 25, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, H.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Mao, X.; Zeng, L.; Wang, X.; Xiao, X. Two-probe optical encoder for absolute positioning of precision stages by using an improved scale grating. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 21378–21391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X. Improvement of absolute positioning of precision stage based on cooperation the zero position pulse signal and incremental displacement signal. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 986, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, P.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X. A compact design of optical scheme for a two-probe absolute surface encoders. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Symposium on Precision Engineering Measurements and Instrumentation, Kunming, China, 8–10 August 2018; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; Volume 11053, pp. 960–966. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Ni, K.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, X. Highly accurate, absolute optical encoder using a hybrid-positioning method. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 5258–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; Ni, K.; Wang, X. Design and testing of a linear encoder capable of measuring absolute distance. Sens. Actuators A-Phys. 2020, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukuma, H.; Ishizuka, R.; Furuta, M.; Li, X.; Shimizu, Y.; Gao, W. Reduction in cross-talk errors in a six-degree-of-freedom surface encoder. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2019, 2, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, W.; Zhou, Q.; Xue, G.; Wu, G.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Two-channel six degrees of freedom grating-encoder for precision-positioning of sub-components in synthetic-aperture optics. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 21113–21128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Wang, S.; Xue, G.; Liu, M.; Han, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ni, K.; Wang, X.; Li, X. A real-time processing system for dual-channel six-degree-of-freedom grating ruler based on FPGA. In Proceedings of the Optical Design and Testing XI, Nantong, China, 10–20 October 2021; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; Volume 11895, pp. 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, R.; Liu, T.; Maehara, S.; Okimura, R.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. Design of an optical head with two phase-shifted interference signals for direction detection of small displacement in an absolute surface encoder. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2024, 18, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Sato, R.; Zhang, Z.; Matsukuma, H.; Manske, E.; Gao, W. Near-common-optical-path two-axis surface encoder with a three-layer gratings interference method. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 19951–19965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Sato, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. A new optical configuration for the surface encoder with an expanded Z-directional measuring range. Sensors 2022, 22, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Sato, R.; Shimizu, Y.; Matsukuma, H.; Shimizu, H.; Gao, W. Reduction of crosstalk errors in a surface encoder having a long Z-directional measuring range. Sensors 2022, 22, 9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Matsukuma, H.; Li, K.; Sato, R.; Gao, W. Improvement of angle measurement sensitivity using second harmonic wave interference. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 40915–40930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Shimizu, Y.; Sato, R.; Shin, D.; Matsukuma, H.; Archenti, A.; Gao, W. Design and testing of a compact optical angle sensor for pitch deviation measurement of a scale grating with a small angle of diffraction. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2022, 16, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hong, Y.; Shin, D.; Sato, R.; Quan, L.; Matsukuma, H.; Gao, W. On-machine calibration of pitch deviations of a linear scale grating by using a differential angle sensor. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2024, 18, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Yin, C.; Quan, L.; Sato, R.; Matsukuma, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Tamiya, H.; Gao, W. Self-calibration of a large-scale variable-line-spacing grating for an absolute optical encoder by differencing spatially shifted phase maps from a Fizeau interferometer. Sensors 2022, 22, 9348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Gui, W.; Gao, W.; Liang, X.; Li, X. SL3D-BF: A Real-World Structured Light 3D Dataset with Background-to-Foreground Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H. Opto-Mechanical System Design of Absolute Position Measurement Sensor. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N. Research on Alignment System of Absolute Grating Displacement Sensors. Master’s Thesis, Changchun University of Science and Technology, Changchun, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, D. Research on High-Precision Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences), Changchun, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H. Principle and Implementation of Absolute Single-Track Linear Displacement Grating Sensor. Ph.D. Thesis, Changchun University of Science and Technology, Changchun, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Analysis and Compensation of Subdivision Error in Photoelectric Encoders. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Yan, H.M.; Cao, X.Q. A new subdivision method for grating-based displacement sensor using imaging array. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2009, 47, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G. Overview of Major Enterprises Manufacturing Displacement Sensors Worldwide. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2007, 000(002), 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H. Absolute Linear Encoders Applied to CNC Machine Tools. World Manuf. Eng. Mark. 2013, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Major Breakthrough in the Development of Absolute Linear Encoders by Changchun Institute of Optics, Fine Mechanics and Physics. Optomechatron. Inf. 2011, 28, 49.

- Xue, H. Research on Key Technologies of Absolute Position Measurement Sensor. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B. Structural Design of Ultra-Precision Absolute Linear Encoder and Analysis of Its Static Reading Error. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y. Simulation and Design of Absolute Grating Measurement System Based on Dual CCD. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Technology, Xi’an, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, R. Research on 2D Absolute Position Measurement Method Based on Hybrid Coding. Master’s Thesis, Hefei University of Technology, Hefei, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Research on Error Model of Linear Encoder Measurement System. Master’s Thesis, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X. Research on Error Compensation Method of Linear Encoder Displacement Measurement System. Master’s Thesis, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Hu, C.X.; Liu, Z. A novel heterodyne grating interferometer system for in-plane and out-of-plane displacement measurement with nanometer resolution. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Precision Engineering, Boston, MA, USA, 9–15 November 2014; pp. 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, C.; Hu, J.; Yang, K. Accuracy-and simplicity-oriented self-calibration approach for two-dimensional precision stages. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 60, 2264–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagüe-Fabra, J.A.; Gao, W.; Archenti, A.; Morse, E.; Donmez, A. Scalability of precision design principles for machines and instruments. CIRP Ann. 2021, 70, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ren, J.; Huang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, L. Surface form inspection with contact coordinate measurement: A review. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 5, 022006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Chen, L.C.; Kim, D.W.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Matsukuma, H. An insight into optical metrology in manufacturing. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 042003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, J.; Zhong, Z.; Li, X. Global alignment reference strategy for laser interference lithography pattern arrays. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Zhang, X.; Gao, W.; Guo, Y.; Byrne, G.; Hansen, H.N. Nanomanufacturing—Perspective and applications. CIRP Ann. 2017, 66, 683–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, N. Research on Distortion Optimization and Ruling Error of Grating Projection Lithographic Objective Lens. Master’s Thesis, Zhongyuan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, Y. Design of Grating Macro-Micro Composite Displacement Measurement System Based on Linear CMOS. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Research on Assembly and Testing Methods of Three-Coordinate Displacement Stages. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Jia, W.; Xiang, C.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J.; Jin, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C. Polarization-independent 2 × 2 high diffraction efficiency beam splitter based on two-dimensional grating. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 32042–32050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, C.; Sun, J.; Peng, X.; Tian, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Shao, J. Electric-driven flexible-roller nanoimprint lithography on the stress-sensitive warped wafer. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 5, 035101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, X.; Sutherland, D.; Bochenkov, V.; Deng, S. Nanofabrication of nanostructure lattices: From high-quality large patterns to precise hybrid units. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 062004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kulasegaram, S.; Brousseau, E.; Esien, K.; Read, D. Investigation of nanoscale scratching on copper with conical tools using particle-based simulation. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2023, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theeda, S.; Kumar, G. Area-specific positioning of metallic glass nanowires on Si substrate. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2023, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dou, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, N.; Liu, L. Precision encoder grating mounting: A near-sensor computing approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhang, W.; Xiong, X.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, H. Influence of installation error of grating interferometer on high-precision displacement measurement. Opt. Eng. 2021, 60, 045102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.R.; Hu, J.C.; Zhu, Y.; Hua, G.J. Multi-Axis Laser Interferometer Not Affected by Installation Errors Based on Nonlinear Computation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, C. Real-time displacement calculation and offline geometric calibration of the grating interferometer system for ultra-precision wafer stage measurement. Precis. Eng. 2019, 60, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Saito, Y.; Muto, H.; Arai, Y.; Shimizu, Y. A three-axis autocollimator for detection of angular error motions of a precision stage. CIRP Ann. 2011, 60, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mu, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y. Error Analysis and Compensation in Laser Interference Measurement. Mach. Tool Hydraul. 2006, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.W.; Wang, X.; Meng, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Ren, M.; Zhu, L.M. Design, modeling and control of high-bandwidth nano-positioning stages for ultra-precise measurement and manufacturing: A survey. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 062007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Kim, S.; Bosse, H.; Minoshima, K. Dimensional metrology based on ultrashort pulse laser and optical frequency comb. CIRP Ann. 2025, 74, 993–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Cui, J.; Tan, J. A novel enhanced roll-angle measurement system based on a transmission grating autocollimator. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 120929–120936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.R.; Cui, J.W.; Tan, J.B. A three-dimensional small angle measurement system based on autocollimation method. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2022, 93, 055102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, Y.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xing, H.; Tan, J. High-precision autocollimation method based on a multiscale convolution neural network for angle measurement. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 29821–29832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Du, H.; Xiong, X. Real-time direction judgment system of sub-nanometer scale grating ruler. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 74939–74948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Cheng, R.; Yang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M. Real-time correction of periodic nonlinearity in homodyne detection for scanning beam interference lithography. Opt. Eng. 2018, 57, 104107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, J.; Goch, G.; Forbes, A.; Sprauel, J.; Clément, A.; Haertig, F.; Gao, W. Modelling and traceability for computationally-intensive precision engineering and metrology. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 815–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, C. Analysis and compensation of synchronous measurement error for multi-channel laser interferometer. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 055201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, X.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Hu, P.; Tan, J. A High Accuracy, High Speed Dynamic Performance Test Method for Heterodyne Interferometry Measurement Electronics. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 7009008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wei, C.; Tan, J.; Chen, K.; Liu, S.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Z. A review of iterative phase retrieval for measurement and encryption. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2017, 89, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Donmez, A.; Savio, E.; Irino, N. Integrated metrology for advanced manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 639–665. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, W.; Wang, L.; Xia, Y. Two degree-of-freedom fiber-coupled heterodyne grating interferometer with milli-radian operating range of rotation. Sensors 2019, 19, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, F. Research on Error Correction Technology of Grating Displacement Measurement System. Electron. Qual. 2024, 12, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, D.; Liang, W.; Zheng, M. Research on Installation of Linear Encoders for Precision Linear Measurement Components. Mach. Manuf. 2025, 63, 80–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Ding, X.; He, L.; Qiu, B. Introduction to On-Line Weighing, Length Measuring and Marking Equipment for Oil Special Pipes. Equip. Manag. Maint. 2021, 17, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Matsukuma, H.; Sato, R.; Gao, W. Fabry-Pérot angle sensor using a mode-locked femtosecond laser source. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 46366–46382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Matsukuma, H.; Sato, R.; Manske, E.; Gao, W. Improved peak-to-peak method for cavity length measurement of a Fabry-Perot etalon using a mode-locked femtosecond laser. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 25797–25814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Matsukuma, H.; Sato, R.; Gao, W. Wide-range absolute angle measurement based on a broadband solid etalon fringe using a mode-locked femtosecond laser. Precis. Eng. 2025, 95, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F. On the three paradigms of manufacturing advancement. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 2023, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hu, Y.; Ou, X.; Li, X.; Lai, J.; Liu, N.; Cheng, X.; Pan, A.; Duan, H. Metasurface-enabled on-chip multiplexed diffractive neural networks in the visible. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Qian, J.; Feng, S.; Yin, W.; Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Han, J.; Qian, K.; Chen, Q. Deep learning in optical metrology: A review. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Performance Metric | HEIDENHAIN | MITUTOYO | FAGOR | CIOMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision Class | ±3 μm | ±3 μm | ±3 μm | ±3 μm |

| Movement Velocity | Up to 600 m/min | Up to 180 m/min | Up to 180 m/min | Up to 120 m/min |

| Resolution | 1 nm | 0.005 μm | 0.1 μm | 0.01 μm |

| Maximum Measurement Length | 4240 mm | 3000 mm | 3040 mm | 1200 mm |

| Data Interface | EnDat 2.2 | Fanuc, Mitsubishi | SSI, FreeDat | CPE-Bus |

| Error Source | Compensability | Degree of Impact on Measurement | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing process error | Partial errors can be compensated for through the averaging effect and algorithms; however, reticle defects and mechanical geometric errors are fundamental errors that cannot be completely eliminated. | Determine the upper limit of the system’s theoretical accuracy and serve as irreversible hardware-level error sources. | 1 |

| Environmental interference error | Errors can be reduced through temperature control, real-time compensation, and vibration isolation measures, but complete control is difficult to achieve. | Affect randomness and long-term stability in actual industrial environments, impact measurement repeatability and drift, and act as the main obstacle to application scenario adaptability. | 2 |

| Optical system error | Errors can be significantly reduced with high-quality optical components and assembly calibration. | Directly affect fringe contrast and signal symmetry, leading to orthogonal signal distortion and increased subdivision errors, and serve as a key bottleneck for system-level accuracy stability. | 3 |

| Signal processing and encoding error | Limited by hardware resolution and sampling rate. | Mainly affect high-resolution and high-speed measurement scenarios and represent error sources with the highest controllability, relying on algorithm optimization. | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, M.; Yuan, Y.; Luo, L.; Li, X. A Review: Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology. Sensors 2025, 25, 5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25195997

Zhao M, Yuan Y, Luo L, Li X. A Review: Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology. Sensors. 2025; 25(19):5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25195997

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Maqiang, Yuyu Yuan, Linbin Luo, and Xinghui Li. 2025. "A Review: Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology" Sensors 25, no. 19: 5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25195997

APA StyleZhao, M., Yuan, Y., Luo, L., & Li, X. (2025). A Review: Absolute Linear Encoder Measurement Technology. Sensors, 25(19), 5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25195997